Abstract

Studies examining the impact of social change on individual development and aging postulate the growing importance of flexible relationships, such as friendship. Although friendship is well known as a factor of well-being in later life, the prevalence of friendship in older adult networks and its unequal distribution has been examined only in few studies. Through secondary data analysis of two cross-sectional surveys carried out in Switzerland in 1979 and 2011, respectively, the increasing presence of close friends was confirmed. Our results show that this trend was part of a broader lifestyle change after retirement, with increasing social engagements. However, this trend does not include a general decrease in social inequalities in friendship opportunities. Overall, friendship increase among older adults has contributed to a polarization of living conditions, with a majority of active, healthy persons contrasting with a minority of individuals who accumulate penalties.

Keywords: friendship, gender, health, social change, socioeconomic status, social participation, social ties

Although friendship in old age motivated a few studies in the late 1970s up to the mid-1980s (Adams, 1986a, 1986b in particular), the initial impetus was followed by a vacuum until a recent resurgence of interest (Drewelies et al., 2019; Fiori et al., 2020). In this regard, a growing number of studies concerning the ties between friendship and health tend to demonstrate the benefits of this type of relationship for maintaining subjective well-being during the aging process (Carr & Moorman, 2011; Huxhold et al., 2014; Ihle et al., 2018; Krause, 2010). However, analyses of the prevalence and distribution of friendly relationships in old age remain limited. Only a few studies adopted a historical perspective on friendship prevalence (Ajrouch et al., 2007) and examined its increase over time in relation to individual aging and different contextual factors (typically the increase in educational level or the improvement of health status) (Huxhold, 2019; Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011; Suanet et al., 2013). Furthermore, the issue of heterogeneity in friendship distribution and the impact of historical change on the system of inequalities and resources underpinning this type of ties should be further investigated.

On this basis, this article aims to pursue the study of the prevalence of friendships among older adults, and the impact of social change on it, by adopting the double perspective of progress and inequalities. The first one (i.e., “the progress”) proposes to assess the increase in the likelihood of having a close friend within a general context of improving living conditions. Such improvements refer to the health and socioeconomic situations of the older adults, reflecting an increase in resources supporting friendship. We also test the hypothesis of an overall sociocultural change in lifestyles by analyzing the increase of friendship in relation with the growth of other types of social interactions outside the home and the family. The second perspective (i.e., “the inequalities”) focus on the heterogeneity of the older adults’ population. It considers that the abovementioned progresses have not concerned all the older adults, who do not have the same capacities to have and maintain friendship ties. We consequently further study the factors associated with close friendship and how they evolved across time. This approach supports a discussion of friendship inequalities, considering both the influence of older adults’ position in the social stratifications (e.g., gender, class, age) and a system of individual resources (health, social network, and participation).

For this purpose, we took advantage of the rare opportunity provided by the existence of two cross-sectional surveys 32 years apart (1979 and 2011) that investigated the living and health conditions of 65–94 years old in two regions of Switzerland. Switzerland constitutes a European setting that has yet to be studied regarding friendship. Moreover, Switzerland is illustrative of a both wealthy and unequal society. Indeed, life expectancy and income are among the highest in the world. However, one in five older adults live below the threshold of poverty (Oris et al., 2017) and the life expectancy in good health of the less-educated stagnates (Remund et al., 2019). Furthermore, Switzerland has a welfare state with a liberal-conservative political tradition (Esping-Andersen, 1990). Its conservative side implies a retirement system build on professional trajectories (occupational insurances) largely based on the male breadwinner model (Oris et al., 2017). Its liberal side refers to the considerable weight given to the individual responsibility through the importance of the subsidiarity principle. In other words, the State only intervenes when the family or local communities are unable (Cattacin, 2006). This implies crucial importance of the private source of resources, especially personal networks. Finally, Swiss public authorities, as most Western countries across the world, enthusiastically appropriated the model of active aging, which has been supported by international organizations and promoted the social participation of older adults in a well-being perspective (Baeriswyl & Oris, 2021).

All in all, this paper aims to support a better understanding of the social issues of friendship as an increasing social resource in older age. This is especially important in countries of liberal traditions, in which social relationships play a crucial role in facing the aging process. In the following sections, we discuss the rationale of our research questions through a focused literature review. Then, we present the data and methods. Results sustain the discussion about sociocultural changes, including the expansion of a lifestyle more oriented toward the public domain, and underline the complex relationships between progress and inequalities related to historical change. Issues in terms of vulnerability are discussed as well.

Studying Historical Change in Friendship: Literature Review and Questioning

On a conceptual level, the impact of sociohistorical context on individual development is an important component of the life span and the life course theories. Two perspectives can be distinguished: the first perspective focuses on the impact of major historical events on the differential development of individuals related to cohort, age, and period issues. The second focuses “on historical changes in developmental contexts that evolve gradually” (Drewelies et al., 2019, p. 1022; see also Huxhold, 2019). In this second perspective, change is a long-term process linked to different mechanisms, affecting numerous life domains that interact with each other. Of course, changes likely affect the various birth cohorts to various degrees since they live them at different points in time and during different phases of their life trajectory. However, these differences are assumed to be more gradual and less qualitative than when studying the impact of a single major historical event like a world war (Huxhold, 2019). This perspective is particularly well suited for the study of a historical change in times of relative stability as was the case of Switzerland during the period under consideration.

The “Historical changes in developmental contexts theoretical framework” underlines multiple and interlinked mechanisms existing at different levels to understand how historical change shapes the individual functioning and aging process. These mechanisms refer to the microlevel of individual resources (including socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial characteristics), to the meso level of social embeddedness (i.e., transformation of family, network, and social participation), to the macro level of sociocultural system (zeitgeist and social norms, notably toward greater individualization) (Drewelies et al., 2019). In this context, friendship ties can be seen as both cause and consequence of the historical change in aging, included in a multilevel and multidimensional process.

Regarding the impact of historical context on friendship, Fiori et al. (2020) proposed a conceptual model to understand the increasing importance of individual investment in this type of tie in later life. They underlined three main mechanisms: first, a direct effect on time and energy that an individual needs to form and maintain social ties—notably through the development of retirement systems. A second effect lies on the social opportunity structure of each individual or, in other words, all the potential ties available and the cost of the investment in them. Third, historical context can influence the individuals’ capacities (typically health) and motivations (determining the ties to invest these resources) to invest in social relationships.

Sociocultural changes toward greater individualization (Elias, 1991; Giddens, 1991) seem to be crucial in the increasing importance of flexible and chosen ties that friendship represents in contrast to more formal family ties (Allan, 2008). Under the Fiori et al. model, these changes increased the motivation (increasing role of personal choice) and decreased the costs (greater social acceptability) to invest in non-kin relationships. Similarly, evolving age and gendered norms contribute to historical differences toward greater diversity in social ties (Fiori et al., 2020; see also Drewelies et al., 2019). The demographic changes (e.g., gains in life expectancy, and decreasing fertility rate or increasing divorce) are also an important source of change in the social opportunity structure of social ties (Antonucci et al., 2019; Fiori et al., 2020). Education expansion contributes with demographic changes to the increase of both the opportunity structure (e.g., number and type of ties) and individual capacities and motivations (e.g., cognitive abilities and values), to invest in friendship. In addition, educational level influences other contextual factors of social relationships such as longevity, access to technology (Fiori et al., 2020), and health status (Antonucci et al., 2019).

At an empirical level, Ajrouch et al. (2007) confirmed an increase in the quantitative importance of non-kin ties among older adults in recent decades. Specifically, a few research comprehensively reviewed the rise of such ties simultaneously in the contexts of individual histories and historical changes. Two papers, focused on the Netherlands, studied people aged between 54 and 84 years 17 years apart: they showed that the negative impact of advancing age on maintaining non-kin ties (Suanet et al., 2013), and in particular friendship ties (Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011), has declined. Another research, centered in Germany, studied friends’ trajectories from middle age (45 years old) to old age (85 years old) (Huxhold, 2019). It showed an increase in the inclusion of friends in close social networks in later-born cohort in both midlife and old age, and a significant rise in time spent in activities with friends in old age.

The aforementioned studies also tested some of the mechanisms on which the overall progression of this type of relationship among later cohorts of older adults could be based. This includes socioeconomic progress, health improvement, and changes in living style or individual perceptions of aging. Each of these mechanisms partially explains the observed historical trends, however without offering a complete understanding (Huxhold, 2019; Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011; Suanet et al., 2013). In our perspective, this suggests that in addition to the variety of mechanisms that can be explored to ascertain the historical differences in friendship, change in the resources system associated with friendship should equally be assessed for a better understanding of the impact of historical change in friendship. This also refers to the issue of individual heterogeneity and social inequalities.

As Bidard (1997) observed, friendship—an intimate and elective relationship—is, nonetheless, social in nature as personal ties precisely demonstrate how individuals are linked to society. On one side, flexible and individual ties correspond to the demands for individuality which are features of our modern societies (Allan, 2008). However, on the other side, they require more considerable and explicit efforts of stimulation and maintenance than more formal and institutionalized ties that the family embodies, regulated by both social and legal norms (Blieszner & Roberto, 2004; Roberts & Dunbar, 2011). The question of unequal opportunities and resources needed to preserve friendship while aging (as mentioned before, e.g., in terms of socioeconomic resources, health, or living style, Huxhold, 2019; Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011; Suanet et al., 2013) is thus important to consider.

Furthermore, the issue of inequalities should be considered under the scope of historical change at the macro level. Indeed, overall change toward greater individualism has been subject to theoretical controversy regarding the possible decreasing impact of social stratification on individual agency. For instance, for the German sociologist, Ulrich Beck, “Society can no longer look in the mirror and see social classes […] all we have left are the individualized fragments” (Beck & Willms, 2004, p. 107). However, other scholars insist on inequalities in wealth and health, particularly in old age, and their construction across life courses that are heavily dependent on institutions (the school system, the labor market, and importantly, the retirement system) (Dannefer, 2020; O’Rand, 2006; Oris et al., 2021). We will see whether the socioeconomic stratification of friendship in old age decreased over time.

Linked to this discussion while also referring to broader cultural determinants, gender differences are another important component of social stratification to consider. Despite historical changes promoting gender equality, women still have fewer socioeconomic and health resources to face older age (Baeriswyl, 2018; Oris et al., 2017), and thus maintain relationships. On the other hand, studies indicate that older women seem to benefit more from social relationships (Arber et al., 2003; Chambers, 2018), thus would be advantaged by increasing friendship ties. The results of Suanet et al. (2013) about friendship in the Netherlands, or those of Schwartz and Litwin (2018) on the social network of older Europeans, support this statement. However, the issue of change in the impact of gendered norms in old age is yet uninvestigated.

Linked with the issues of both historical changes and a system of individual resources and social inequalities associated with friendship, the last aspect considered in this paper concerns the increasing importance of social participation of older adults outside the household and family. Overall, the historical changes in the living and health conditions of older adults (for Switzerland, Gabriel et al., 2015; Remund et al., 2019), together with the broader sociocultural change toward greater individualism mentioned above, have promoted new lifestyles after retirement age. Older age is no longer synonymous with social “retirement,” and older adults tend to be actively involved outside their homes and families (Baeriswyl, 2017). This trend is supported by the “active aging” concept and policies, which link social participation and older adults’ well-being (Walker, 2002). Friendship can be seen as part of these historical changes toward a new retirement lifestyle, as it refers to individualized ties outside the family institution. Moreover, social activities can be considered as a framework for relationships where friendship can arise and be maintained (Bidart, 2010). Sociability activities, such as going to café or playing board games, already embody this dynamic; however, more institutionalized activities, such as involvement in associations, could even be more effective (Grossetti, 2005). In addition, we should note that social participation is impacted by the system of social stratification: the various activities are indeed not equally distributed among various social groups, for instance in terms of socioeconomic position or gender (Baeriswyl, 2017, 2018).

Finally, the increasing importance of social ties outside the family raises the question about the degree of complementarity or competition between family ties and friendship ties. On the one hand, according to the theories underlying the primacy of family ties and support over aging process (Cantor, 1979; Carstensen, 1993), it is expected that friendship compensates for a lack of family relationships. However, on the other hand, increasing diversity and individual choice in network composition (Antonucci et al., 2019; Fiori et al., 2020) implies less interdependence between family structure and the existence of close friendship.

To summary, this paper wants to study close friendship prevalence among older adults in two regions of Switzerland as part of gradual social change. Empirically, we take the opportunity provided by the existence of two comparable cross-sectional surveys on older adults living conditions conducted in 1979 and 2011. These 32 years correspond to a relatively short period of time but cover most of the transition to late modernity or post-modernity, a transition marked by the growing importance of individual values and choices in the conduct of life trajectories (Elias, 1991; Giddens, 1991; Shuey & Willson, 2021). In addition, at a more socio-demographical level, population compositional change is also important during this period (for instance regarding education expansion, Blossfeld & Shavit, 2010) and has significatively affected the birth cohorts we study during this 32-year period. All in all, the empirical data used in this paper support the study of individuals whose trajectories are anchored in a very contrasted historical context and resulted in various life conditions. The younger cohorts studied grew up in the context of post-war growth and lived the sociocultural turn of the 1970s as young adults. By contrast, the oldest reached retirement age after the Second World War and have hardly experienced the turn of the 70 s. After confirming the increase of close friendship ties among the studied populations, we consider this trend from the dual perspective of progress and inequalities. First, we examine to which extent it is associated with the increase of other resources among older adults. Second, we deepen the issue of unequal opportunities to have and maintain close friendship in older age over historical time, considering the influence of the individual position in social stratification and various individual resources.

Method

Data

Our analyses are based on the comparison of data from two cross-sectional surveys conducted 32 years apart on the health and living conditions of older adults. Until 1979, only experts were solicited by the public authorities to guide aging policies; the survey obtained that year was the first in Switzerland, where the voice of the older adults was heard. For the research team, the main issues were dependency and isolation (Lalive d’Epinay et al., 1983). The 2011 data collection was part of the most ambitious gerontological survey ever done in Switzerland, which questioned 3,600 adults aged 65 + in five cantons, including the two areas surveyed in 1979 (Ludwig et al., 2014). These data have already been exploited in more than 60 publications1 (for a complete critical assessment applying the total survey error model, see Oris et al., 2016). The main issues in 2011 turned around the paradoxical relationship between progress and inequalities. Despite differences in societal and scientific interests, the purpose of repeating a similar survey design, using a number of identical questions, was to seize the rare opportunity of forsaking impressionism and aggregating figures for a precise study of the changes that occurred over three decades.

Both surveys were carried out on random samples of individuals aged 65 years and older in each region, stratified by sex and quinquennial age groups. The samples used in the analyses included 1,519 individuals in 1979 and 1,097 in 2011. The comparable population includes individuals between 65 and 94 years of age who were cognitively able to answer the questionnaires and lived in private households in two contrasted regions of French-speaking Switzerland (see Table 1 for the main characteristics). These regions are the urbanized and socioeconomically advanced canton of Geneva, with a highly diverse population and a Calvinist tradition, and Central Valais, a mountainous area with mixed activities that has been a stronghold of Catholicism for a long time (Nicolet, 2018). Largely, this diversity reflects that of Switzerland and most of northwest Europe.

Table 1.

Surveyed Regions’ Main Characteristics.

| Region | Type | Historical confessiona | Life expectancy in 2010/2011 (years) | Tertiary education in 2012b (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||||

| Geneva (GE) | Urban | Protestant | 85.7 | 81.1 | 39 |

| Valais (VS) | Semi-urban | Catholic | 84.1 | 79.3 | 23 |

Note. Table taken from Duvoisin (2020: 47, own translation) and completed with data derived from the Federal Statistical Office (Office fédéral de la statistique [OFS] n.d.).

Majority confession may differ from historical one. However, historical confessions always influence the institutional and cultural frameworks of each region (Monnot 2013).

Proportion of people with tertiary education among the resident population aged 25 years and older (Office fédéral de la statistique [OFS] n.d.).

Variables

A question about the existence of a friend was repeated in the two surveys. In 1979, the research team followed the suggestion of a few pioneering studies, asking participants to separate their “best” friends from the others and to state if they had a “close” friend (Adams, 1986b, p. 40; Matthews, 1983). We analyzed the replies in a binary form (having at least one close friend: yes, no). In this way, we examined one pattern of friendship. Defined as particularly “close” by the individuals, this friend represents a relationship on which the individual can count on, both emotionally and/or practically.

Coherently with the literature review introducing this paper, different variables have been identified as being associated with the existence of a close friend in a personal network. In addition to age, sex, and region (the variables that stratify the samples and refer to various dimensions of social stratification, that is, age and gender norms, and sociocultural context), particular attention was given to two crucial resources: the level of education (compulsory, upper secondary, tertiary) and health through self-rated indicator (poor, satisfactory, good). In addition to be an important factor for the development and maintenance of non-kin relationships, education is an excellent proxy of the individual socioeconomic position, for instance highly correlated to poverty risk among older adults (Oris et al., 2017). Furthermore, this information is comparable across the period 1979–2011 and is available for each individual, while a direct measure such as household monthly income is missing for 15% of the sample (Oris et al., 2016). Regarding self-rated health, this indicator has been shown to offer a reliable assessment of both psychological and physical conditions (Idler et al., 1999; Jylhä, 2009) through a simple variable.

To study friendship within a broader set of social relationships and activities, our analyses considered the family network through three variables documenting: (1) the living arrangement (married, not married and living alone, not married but cohabiting)2, (2) the existence of descendants (none, having at least one living child, having a child(ren), and at least one grandchild), and (3) the existence of at least one living sibling (yes, no). We also included various types of social participation through four variables: the involvement in associations (nonmember, member, active member going to meetings at least once a month or having responsibilities), commitment to the community (attending political/trade union demonstrations or village/neighborhood events at least once a year: yes, no), community sociability (going to café or playing board games at least once a month: yes, no), and family visits (visiting or receiving visits from the family at least once a month: yes, no).

Except for the level of education – since in the studied birth cohorts, the highest diploma was usually obtained early in life – all the variables we use described the individuals’ situation at the time of the survey. Because they were collected simultaneously, we cannot affirm that a statistical association implies a causal link with friendship. Nevertheless, they refer back to a “system of resources” (Lalive d’Epinay et al., 2000), in which it is pertinent to examine the links to the presence of a close friend (which is a part of this system) and, specifically, the changes in these associations between 1979 and 2011. The distribution of the older population on the various variables at the two historical points in time is presented in Table 2 and addressed at the beginning of the results section.

Table 2.

Participants’ Characteristics 32 Years Apart.

| n | Distributiona | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Modalities | 1979 | 2011 | 1979 | 2011 | p value | |

| Gender | Women | 756 | 530 | 60% | 55% | .00 | *** |

| Men | 763 | 567 | 40% | 45% | |||

| Age | 65–94 years old | 1,519 | 1,097 | mean: 72.9 | mean: 74.2 | .00 | *** |

| sd: 5.98 | sd: 6.58 | ||||||

| Level of education | Compulsory | 989 | 225 | 67% | 20% | .00 | *** |

| Upper secondary | 358 | 543 | 23% | 50% | |||

| Tertiary | 170 | 329 | 10% | 30% | |||

| Self-rated health | Very poor – poor | 277 | 91 | 19% | 8% | .00 | *** |

| Satisfactory | 513 | 395 | 34% | 34% | |||

| Good – very good | 713 | 596 | 47% | 58% | |||

| Living arrangement | Married | 850 | 637 | 52% | 60% | .00 | *** |

| Not married and living alone | 471 | 374 | 34% | 32% | |||

| Not married but not living alone | 198 | 84 | 14% | 8% | |||

| Descendants | No child living | 381 | 157 | 26% | 14% | .00 | *** |

| At least one living child | 271 | 124 | 18% | 13% | |||

| At least one grandchild | 867 | 816 | 57% | 73% | |||

| Living sibling | Yes | 1,143 | 810 | 75% | 78% | .08 | * |

| No | 376 | 276 | 25% | 22% | |||

| Community sociability | Yes | 967 | 906 | 61% | 86% | .00 | *** |

| No | 548 | 176 | 39% | 14% | |||

| Associative involvement | Nonmember | 809 | 340 | 54% | 29% | .00 | *** |

| Member | 287 | 412 | 18% | 37% | |||

| Goes to meetings at least 1×/month or has responsibilities | 423 | 345 | 27% | 34% | |||

| Community commitment | Yes | 648 | 637 | 42% | 64% | .00 | *** |

| No | 867 | 445 | 58% | 36% | |||

| Family visits | Yes | 1,138 | 823 | 75% | 76% | .39 | NS |

| No | 379 | 262 | 25% | 24% | |||

| Close friendship | Yes | 951 | 815 | 63% | 80% | .00 | *** |

| No | 560 | 243 | 37% | 20% | |||

Abbreviation: NS = not significant.

Note. *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

Weighted analyses.

Analyses

Various analyses were carried out on an amalgamated database bringing together the two surveys. Weighting coefficients were computed for each survey to restore the real population structure, biased by the stratified design of the survey sample (e.g., StataCorp, 2011). These were used in all analyses. A series of descriptive analyses provided an initial image of the distribution of friendships and other resources in the older adult population from 1979 to 2011.

Thereafter, the first set of logistic regressions was used to assess the effect of historical differences in population composition (readable in terms of progress) on the increased frequency of close friendships observed over time. The various models calculated the effect of the survey period on the likelihood to declare a close friend. We started with an initial model including the survey period and the basic sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender, age, and regions), to which we added various groups of variables (education, health, family structure, and social participation; the successive models are indicated with Arabic numerals). The comparison of the various models with the initial model indicated to which extent the changes in population composition explain the increase in close friendships.

The second set of regression analyses further study the factors associated with having a close friend at an individual level, also considering possible historical differences in those associations (the different models are indicated with Roman numerals). For this purpose, interaction effects between the survey period variable and the other co-variables were introduced in the regression models. For the sake of parsimony, only interaction effects whose p-value < .1 were kept in the models. Further, we presented two intermediary models (including sociodemographic variables, on the one hand, sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and health variables on the other hand) in addition to the complete model (including family and social variables as well); however, we proceeded step by step, adding variables by variables, and remained aware of possible cross effects and links between co-variables. These analyses supported a discussion about a system of social inequalities and individual resources that includes close friendship, and its possible change toward greater individualization.

Average marginal effects (AMEs) are used to present the regression results concerning the effect of the population's composition on the historical difference in friendship and the differential effect of the associated resources discussed above, according to the survey period. This method is based on the calculation of predictive values from the parameters estimated in regression models. AMEs represent the predicted change in the value of the dependent variable based on the value of the independent variable (e.g., they can be interpreted as, “on average, being a woman increases the probability of having a friend by × percentage points (pp)”; for more details, see Long, 2014). In addition to providing a simple and obvious means of summing up the effects of the different variables, AMEs have the advantage of enabling a reliable comparison of the various models resulting from logistic regressions (for more details, see Mood, 2010).

Results

Increased Friendship Ties and Other Historical Changes among Older Adult Populations from 1979 to 2011

From 1979 to 2011, there was a clear and significant increase from 63 to 80% (p < .001) in the proportion of older adults declaring that they had a friend to whom they felt particularly close.

More generally, the older adults in 2011 were clearly not the same as the older adults in 1979 (Table 2). As expected, the 65–94 years old living in private households in our two surveyed Swiss regions were on average older in 2011 than in 1979. Although a majority of women were observed, their proportion has decreased because of the progress in male longevity (Remund et al., 2019). A rapid analysis of the resources’ distributions reveals the extent to which the general features of this population significantly evolved over three decades. There was an impressive increase in the level of education from a majority with only basic education in 1979 to less than a quarter of such individuals in 2011. Regarding health, the older adults declared themselves generally to be in better health in 2011 (58% rated their health as good or very good, compared to 47% in 1979). Their social integration also appeared to have improved. In 2011, they were not only more likely to have a varied family network but were also more engaged in various social activities outside their household and family circle. Overall, the signs of progress are undeniable.

Effects of Population Composition on Friendship

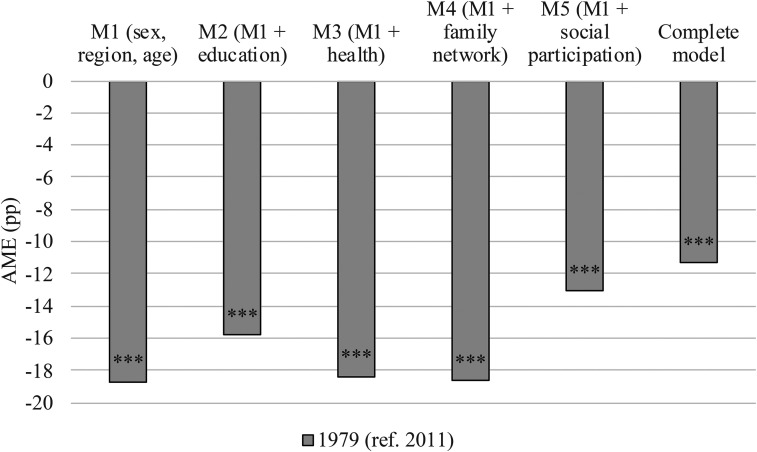

The first set of regression analyses shows the effect of the survey period by checking for different resources (Figure 1). Comparing the various results reveals the effects of change in population composition on the increase of close friendships.

Figure 1.

Average marginal effects (AME) of survey period on the probability of having a close friend in six regression models. Note. This figure shows the effect of being surveyed in 1979 versus 2011 on the probabilities of reporting close friend in various regression models: the difference in results between the first (“baseline”) model (M1) and the other models (M2–M5 and Complete model) refers to the share of the survey effect explained by the specific variables included in each last models. For instance, comparing M1 and M2, we see that the survey effect is reduced from about −19 pp to −16 pp with “equal education,” that is the change in education level between the two surveys explained about 3 pp of the survey effect on probabilities of reporting close friendship; *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

The results of the initial model (including only sex, age group, and region) unsurprisingly confirm that, on average, there was a smaller probability (−19 percentage points [pp]) of having a close friend in 1979 than in 2011.

When considering the impacts of various groups of covariables on the effect of the survey period, mixed results were noted. The level of education (Model 2) captures the survey period's effect only to a limited degree, reducing the lower chance of having a friend in 1979 compared with 2011, from −19 to −16 pp. In other words, with the same level of education, older adults would still have a 16% greater chance of having a close friend in 2011 compared with 1979. The inclusion of variables for health resources (Model 3) does not affect the period effect. Similarly, the indicators of kin availability (family network) (Model 4) do not affect the period effect. The most impressive reduction in the survey period effect, −13 pp, results from the introduction of social participation indicators (Model 5).

The complete model—including all variables together—underlines the fact that the observed survey effect cannot be wholly explained with the variables we mobilized.

Changes and Continuity in the Friendship-Related Profiles

A further examination of the factors associated with close friendship ties and their possible change according to survey period reveals a tension between change and continuity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression of Having a Close Friend: Models with Interaction Terms Between Survey and Other Factors (n = 2,510).

| Model I | Model III | Model V | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p > z | OR | p > z | OR | p > z | |

| 1979 | 0.28 | .00*** | 0.59 | .17 | 0.87 | .75 |

| Men | 0.62 | .01*** | 0.56 | .00*** | 0.53 | .00*** |

| Valais | 0.58 | .00*** | 0.61 | .00*** | 0.59 | .00*** |

| Age (ref. 65–69) | ||||||

| 70–74 | 0.95 | .84 | 1.01 | .97 | 1.12 | .66 |

| 75–79 | 0.70 | .14 | 0.78 | .32 | 0.85 | .53 |

| 80–84 | 0.79 | .37 | 0.90 | .69 | 1.04 | .89 |

| 85–94 | 0.40 | .00*** | 0.46 | .00*** | 0.64 | .09* |

| Education (ref. upper secondary) | ||||||

| Compulsory | 0.74 | .01** | 0.77 | .04** | ||

| Tertiary | 1.14 | .39 | 1.07 | .66 | ||

| Self-rated health (ref. poor) | ||||||

| Satisfactory | 1.65 | .09* | 1.32 | .38 | ||

| Good | 1.95 | .02** | 1.49 | .20 | ||

| Living arrangement (ref. alone) | ||||||

| Married | 0.96 | .73 | ||||

| Cohabiting | 0.92 | .61 | ||||

| Descendants (ref. none) | ||||||

| Child | 0.84 | .28 | ||||

| Grandchild | 0.77 | .06* | ||||

| Sibling alive | 1.15 | .23 | ||||

| Associative involvement (ref. no) | ||||||

| Member | 1.88 | .00*** | ||||

| Active participation | 2.18 | .00*** | ||||

| Community commitment | 1.20 | .09* | ||||

| Community sociability | 1.62 | .00*** | ||||

| Visits from/to family | 1.57 | .00*** | ||||

| Interaction effects | ||||||

| 1979 × men | 1.55 | .03** | 1.63 | 0.02** | 1.48 | .07* |

| 1979 × Valais | 1.54 | .03** | 1.60 | 0.02** | 1.64 | .02** |

| 1979 × age (ref. 65-69) | ||||||

| 70–74 | 0.89 | .70 | 0.83 | .52 | 0.74 | .31 |

| 75–79 | 1.02 | .96 | 0.92 | .78 | 0.91 | .76 |

| 80–84 | 0.63 | .16 | 0.54 | .07* | 0.53 | .07* |

| 85–94 | 0.50 | .08* | 0.45 | .04** | 0.39 | .02** |

| 1979 × self-rated health (ref. poor) | ||||||

| Satisfactory | 0.67 | .24 | 0.74 | .38 | ||

| Good | 0.48 | .03** | 0.54 | .08* | ||

| 1979 × associative involvement (ref. no) | ||||||

| Member | 0.88 | .62 | ||||

| Active participation | 0.55 | .03** | ||||

Abbreviation: OR = odds ratio.

Note. Weighted analyses.

*p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

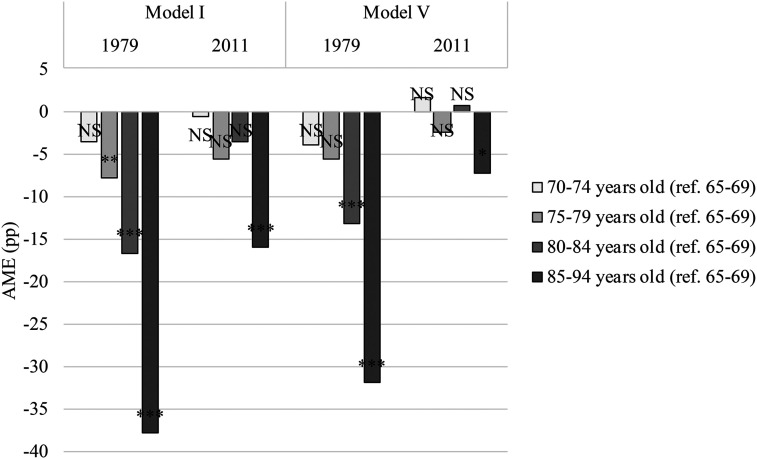

First, the negative impact of chronological age decreased over time. While friendship was globally less present among older individuals than among the youngest elders in 1979, only the 85–94-year-old still showed an appreciably smaller probability of sustaining a friendship in 2011 (Figure 2). Moreover, the age impact was reduced when we introduced the other factors (comparing Models I and V), especially social participation variables.

Figure 2.

Average marginal effects (AME) of age groups on the probability of having a close friend in 1979 and 2011. Note. *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01, NS = not significant; control variables in Model I: sex and region; control variables in Model V: sex, region, education, health, family network variables, and social participation variables.

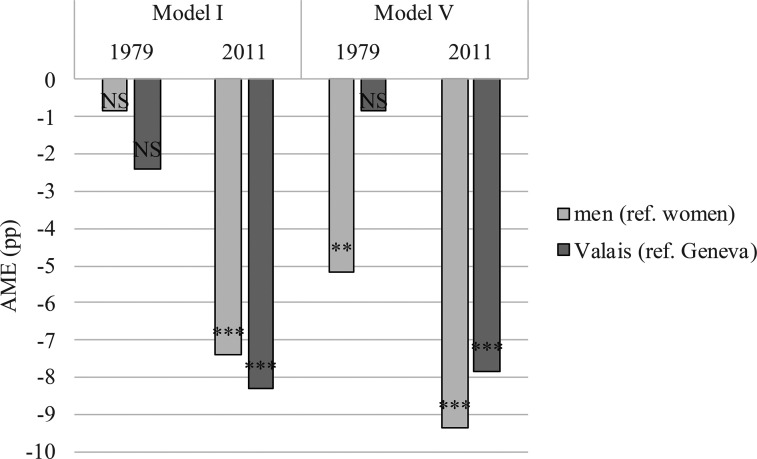

The results also attest to a growing differentiation favoring women from 1979 to 2011. As shown in Figure 3, controlling for age and region, women in 1979, unlike in 2011, had no more chance of having a close friend than men. It is only when we control for other variables—which distribution contributes to promoting friendship among men3—that women appear to have a greater chance of having a close friend already in 1979. However, these chances remained lower in 1979 than in 2011.

Figure 3.

Average marginal effects (AME) of sex and region on the probability of having a close friend in 1979 and 2011. Note. *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01, NS = not significant; control variables in Model I: age and region; control variables in Model V: age, region, education, health, family network variables, and social participation variables.

Growing differentiation is also observable when we consider the regional context effect. Figure 3 shows the emerging positive impact of living in urban Geneva on the probability to have a close friend in 2011 compared to 1979. This regional impact cannot generally be explained by the difference in composition of the other factors.

The results regarding the level of education emphasize the persistence of its impact over time (Table 3). Individuals who attended only compulsory education showed a lower probability of sustaining a close friendship in old age, and this did not change between 1979 and 2011.

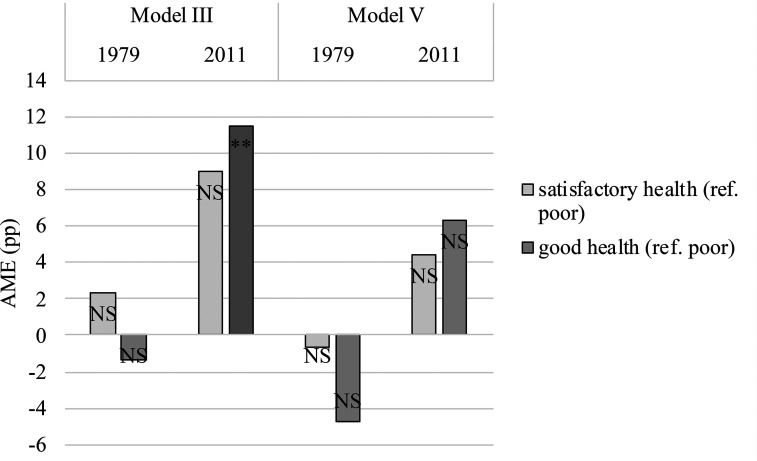

Conversely, we observed a growing association with self-rated health. Although in 2011 we do not see a robust link in the complete model, an intermediary model (Figure 4) shows a positive and significant relationship between feeling in good health and having a close friend. The capture of this significant link by the inclusion of social participation variables in the fifth model (Model V) suggests a generally healthy and active way of life observable after retirement.

Figure 4.

Average marginal effects (AME) of self-rated health on the probability of having a close friend in 1979 and 2011. Note. *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01, NS = not significant; control variable in Model III: sex, age, region, and education; control variables in Model V: sex, age, region, education, family network variables, and social participation variables.

Indeed, our analysis emphasized the important and complementary links between friendship and social activities. Unsurprisingly, practicing forms of community sociability and being engaged in community or family interactions were significantly linked to having a close friend in both 1979 and 2011. This link was strengthened in the case of associative activities—in 2011, appeared a significant association between being actively involved in an association and having a close friend.

The analysis of the relationships between the indicators of the entourage (household and family) and friendship showed the stability and relative independence afforded by these types of ties (Table 3). Only having grandchildren was negatively linked to having close friends, and this relationship only appeared when we controlled for social participation variables.

Discussion

Our analyses focused on data from an original database, offering a rare chance for robust comparisons over a 32-year period. They confirmed an increased prevalence of friendship: Only a minority of older adults did not mention having a close friend in 2011. In this paper, we studied this trend from a double perspective of progress and inequalities.

From the first point of view, the analyses were intended to record the effects of historical differences (i.e., the “progresses”) in socioeconomic, health, and social embeddedness characteristics of the retired population on the increased prevalence of friendship. Results were unable to demonstrate the existence of fully explanatory mechanisms. As mentioned in the conceptual approach to the impact of historical change in the aging process, the involved mechanisms are multiple and interlinked. Contributing to the study of these mechanisms, our results align with other studies in other national contexts concerning the role of the improvements in socioeconomic conditions, and especially the increased access to medium and high diplomas across the cohorts, in the rise of friendship among the older adults. However, in the Swiss context, these changes do not explain much of the rising prevalence of friendship observed between 1979 and 2011. Additionally, compared to a few other studies, in Switzerland, improvement in health status—measured through self-rated health—had no obvious impact.

Overall, the assumption that progress in socioeconomic and health conditions explains the rise in friendship is only very partially validated through our study. Besides that, the main result, the most original considering the existing literature, is that the increase in the frequency of friendship over three decades went together with an increasingly socially active way of life in older age. Indeed, even if the sense of causality between increasing friendship ties and increasing social participation cannot be established with our cross-sectional data4, our result indicates that the progression in opportunities to make and maintain friends over time did not emerge in isolation. It was part of a broader sociocultural change in older adults’ behavior, including growing individual participation outside the household and family circle.

However, we should add that the examination of the resources system associated with close friendship existence shows that it was not associated with a lack of family ties or contact. Overall, one tie did not replace the other. The only negative link between friendship and a family indicator concerns the grandparent status and this occurs only under the control of other social participation variables. This suggests that even if social participation overall progressed and retirees occupied a multitude of roles inside and outside the family, they had to find a balance between all of them (Gourdon, 2015). In this context, it could be that the relationships with grandchildren were emotionally rewarding enough (Hughes et al., 2007) and/or that family norms still influenced individual choices and ties (Lüscher & Pillemer, 1998), with preference given to the younger offspring.

From the perspective of individual resources and social inequalities, the further examination of the profiles of the individuals mentioning a close friend produced other important results. At least for the period and the birth cohorts covered, we invalidated the assumption of a decrease in social inequalities. The only movement toward homogenization in the chances of having a close friend concerned the differences between age groups. From 1979 to 2011, the increase was particularly impressive among the oldest individuals, and close friendship became a more important resource in the later stages of life. This trend has been observed in other national contexts (especially in the Netherlands, see Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011; Suanet et al., 2013). Generally, the literature explains the decline of friendship ties with aging through a process of loss and selection (Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011). In this context, the trend toward minimizing the impact of age could involve various nonexclusive mechanisms. First, it can refer to the impact of demographic change on social ties. In particular, the growth of life expectancy at 65 years of age and the process of rectangularization of survival curves (Oris & Lerch, 2009) defer the deaths of friends and companions who made up the “social convoy” (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987), with whom the older adults had gone through life. In addition to its impact on the structure of opportunity to maintain friendship, increasing longevity—in particular, if the older adults are aware of this change—can also influence their motivation to invest in old, and new friendship ties as well, increasing their time perspective (Fiori et al., 2020; Huxhold, 2019). At the macro level, this refers more broadly to the sociocultural dimension of historical change and evolving age norms. Principally, as supported for instance by the active aging concept and policies that became dominant, contemporary social expectations foster older adults to be active agents of their own life, enhancing their perception of control and encouraging them to exploit their potentials (Drewelies et al., 2019; Huxhold, 2019).

Finally, conversely to the decreasing impact of chronological age on friendship, our results demonstrated the emergence of a positive association between good health and friendship from 1979 to 2011. While chronological age can be interpreted as a social dimension of individual aging, referring to the impact of various social expectations about roles and behaviors, health refers more directly to biological aging. The contrast between the observations for each of those two indicators raises questions about the individualization process of the factors determining friendship in 2011. Since the impact of age apparently became less important than health problems, further investigation is required as the inherent limits of cross-sectional data make it difficult to strictly interpret the mechanisms behind these differences.

A historical perspective on the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries also obviously questions gender inequalities. In contradiction with the postulate of decreasing gender norms in a more individualized society, analyses have brought to the fore, the growing differentiation of men and women regarding close friendship. In particular, while women are still discriminated regarding their health, revenue, or residential isolation (based on our current data, see Baeriswyl, 2018; Oris et al., 2017), there are advantages of recent historical trends in close friendships. We have to state that the cohorts studied, even the younger born at the latest in 1946, grew and evolved in a Swiss society still strongly marked by gender inequalities; most have been socialized during the “conservative restoration” of the interwar period (Duvoisin, 2020). For now, our results confirm women's advantage in terms of social relations as mentioned in the literature (Arber et al., 2003; Chambers, 2018), while stressing that this can be relatively new concerning friendship in older age. This has important implications in terms of vulnerability, defined here as latent situations of exposure to risks and stresses (Oris, 2017): through close friendship, older women have greater access to an important socioemotional resource, compensating to some extent persisting gender inequalities.

For regional disparities, increasing inequalities in friendship resources were also observable. This trend benefits Geneva being an urban region, indicating the modern dimension of the individual investment in non-kin ties, favored in a less traditional sociocultural context. In addition, population density is a positive factor of friendship ties by improving the structure of opportunity to invest in such ties (Angelini & Laferrère, 2013). Nonetheless, this result is rather interesting in terms of vulnerability because urban culture has long been considered to be hostile to aging people who would face a higher risk of isolation (Lalive d’Epinay et al., 2000). Conversely, friendship emerged as a specific resource in this context, compared to a more traditional one.

Our analyses have also stressed the stability of the socioeconomic stratification of this elective tie from 1979 to 2011. Going beyond the apparent stability of the effect of the individual's socioeconomic status (specifically, the negative impact of a low level of education), changes concerning the population structure should not be overlooked. In over three decades, the number of older adults with limited educational capital fell from a clear majority to a minority. The latter thus became even more marginalized compared with the rest of the population that, for its part, has taken advantage of the considerable progress in access to education during the second half of the twentieth century.

The results about social participation go in the same direction. We already know from another research that active associative participation is marked by important socioeconomic inequalities (contrary to more private or informal forms of participation, see e.g., Baeriswyl, 2017). Our study establishes the strong link between friendship and social participation, suggesting a process of accumulation of social resources instead of subsidiarity between the elective tie and other social engagements. The associations between friendship and various forms of involvement in the public sphere have even grown stronger from 1979 to 2011, with an increasing significance of active commitment to associations. In addition to representing an accumulation of social ties, activities, and resources, this observation tends toward a socioeconomic polarization of retirees’ lifestyles, with a widening gap between a majority of favored multiactive retirees and a minority of disfavored older adults (Baeriswyl, 2017; Baeriswyl & Oris, 2021).

However, certain limitations are inherent in this paper. In addition to the cross-sectional nature of our data, which limited our analysis of friendship factors and the identification of causalities, we noticed that close friendship is only one dimension of friendship. Our study appears similar to what Rawlins (1992, 2004) called “confidantes,” characterized by more intimacy and commitment than “companions.” It exists in a high part of subjectivity in the definition of a close friend: we suspect interindividual variability in the definitions the survey participants gave of a close friend, and we also cannot certify that this heterogeneity did not evolve from 1979 to 2011 as well. It remains, however, an interesting measure because studies have shown that the appraisal of the relation is crucial in terms of support and well-being (Newsom et al., 2005). Additionally, the measure of the fact to feel close to someone who is non-kin is also very interesting in terms of historical change. Lastly, we do not have any information about the characteristics of the older adults’ close friends (e.g., their gender). Consequently, caution is needed. Although other measures of friendships ties (e.g., contact, shared activities, or number of ties), or specific friendship characteristics, are potentially important, we believe that the observed trends are clear, with consistent results, and that the limited availability of recent historical data balances the lack of details in our friendship indicator.

Another limitation concerns the fact that we studied only adults after retirement age (65 years and older): this does not allow us to conclude that the historical differences observed are specific to older age or whether they reflect more broader transformations of the individual life course. Studies have shown that increasing active lifestyle after retirement in the younger cohort is already observable at the early stages of the life course (Bickel, 2014). However, concerning social network investment, studies have historically demonstrated that increasing involvement with network partners, especially friends, could be particularly important around and beyond retirement age (Huxhold, 2019; Suanet & Huxhold, 2020). The age effect found in previous studies in the Netherlands and in our analyses may further provide some indications favoring this view.

Finally, structural and cultural contexts influence friendship patterns (Ueno & Adams, 2006): the national context of this study is another limitation of our findings that is noteworthy. However, on the one hand, the trends observed in friendship distribution and friendship patterns are coherent with findings in other Western countries (Ajrouch et al., 2007; Stevens & Van Tilburg, 2011; Suanet et al., 2013). On the other hand, while most Western countries are promoting social integration from the perspective of healthy and active aging, our results about the accumulation of social inequalities through personal relationships in the context of a small and wealthy country, such as Switzerland, question this mechanism in a broader way. In particular, Switzerland shares strong similarities with liberal countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, by emphasizing individual responsibility and the role of private support in life course management (Armingeon, 2001).

In summary, through our analysis, we have been able to confirm the growth of this type of elective tie among the older population and to integrate this trend into a more general historical trend in lifestyle that became more participative and open to the outside world. Thus, these changes involved increasing diversity and distance between those who took advantage of decades of progress—in terms of education and health—and a minority of sideliners who accumulated penalties. These marginals do not have the material, physical, and associated psychosocial resources (e.g., motivation, control perception), to adopt this new lifestyle promoted in the new historical context. We understand that the new representation of aging though contributes to a positive image of older age by stressing the potentials of older adults, also poses the risk of stigmatization and a depreciation of the value of those who do not follow the majority trend. However, if friendship participates overall to the accumulation of advantage/disadvantage, it appears also as an important resource, growingly available, especially for older women. These trends require consideration, both in the present and in the future.

Author Biographies

Marie Baeriswyl is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for the Interdisciplinary Study of Gerontology and Vulnerability (CIGEV), University of Geneva. She is member of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research LIVES – Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives (NCCR LIVES). Her research focuses on the social participation and social relationships of older adults. In this framework, she is particularly interested in social inequalities, social change and well-being issues.

Michel Oris is a professor of socioeconomics and demography at the School of Social Sciences, University of Geneva. He has been co-director of the Swiss National Centre of Competency in Research “LIVES. Overcoming Vulnerabilities. Life Course Perspectives”. His research focuses on inequalities, with an emphasis on the interactions between individual trajectories and the dynamics of social structures, on vulnerabilities across the life course.

The VLV survey included two questions, about being married and living alone. They are highly correlated (the married individual who live alone were very rare). The constructed variable “living arrangement” takes into account the two questions and focuses on the notion of loneliness at the household level while distinguishing the spouse from other possible “cohabitants.”

In particular regarding variables significantly associated with friendship in 1979, 73% of women had only compulsory school compared to 58% of men, they were also less often members in associations (−11 pp), less involved in community commitment (−14 pp), and sociability (−25 pp). It should be noted that women stay in 2011 have overall disadvantage related to the variables positively linked to friendship: they were still less educated (+14 pp to have only compulsory school), reported less good health (−9 pp) and were less involved in social life even if the gap is smaller (−10 pp on associative membership, −8 pp on collective involvement, −3 pp on community sociability).

Having a friend can promote social participation, and conversely, an active social life can renew or supplement the pool of friends (Carr & Moorman, 2011, p. 152).

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This work was supported by a Sinergia project (grant number CRSII1_129922/1) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research LIVES—Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives (NCCR LIVES; grant number 51NF40-160590), which are both financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation. The authors are grateful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for its financial assistance.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 51NF40-160590, grant number CRSII1_129922/1).

ORCID iD: Marie Baeriswyl https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8358-4643

References

- Adams R. G. (1986a). A look at friendship and aging. Generations (San Francisco, Calif), 10(4), 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G. (1986b). Secondary friendship networks and psychological well-being among elderly women. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 8(2), 59–72. 10.1300/J016v08n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch K. J., Akiyama H., Antonucci T. C. (2007). Cohort differences in social relations among the elderly. In Wahl H.-W., Tesch-Romer C., Hoff A. (Eds.), New dynamics in old age: Individual, environmental, and societal perspectives (pp. 43–63). Baywood Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Allan G. (2008). Flexibility, friendship, and family. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 1–16. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00181.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angelini V., Laferrère A. (2013). Friendship, housing environment and economic resources: What influences social network size after age 50? In Börsch-Supan A., Brandt M., Litwin H., Weber G. (Eds.), Active ageing and solidarity between generation in Europe (pp. 323–336). De Gruyter. https://www.degruyter.com/view/book/9783110295467/10.1515/9783110295467.323.xml [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Ajrouch K. J., Webster N. J., Zahodne L. B. (2019). Social relations across the life span: Scientific advances, emerging issues, and future challenges. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1(1), 313–336. 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-085212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Akiyama H. (1987). Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. Journal of Gerontology, 42(5), 519–527. 10.1093/geronj/42.5.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S., Davidson K., Ginn J. (2003). Changing approaches to gender and later life. In Arber S., Davidson K., Ginn J. (Eds.), Gender and ageing. Changing roles and relationships (pp. 1–14). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Armingeon K. (2001). Institutionalising the Swiss welfare state. West European Politics, 24(2), 145–168. 10.1080/01402380108425437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baeriswyl M. (2017). Participations sociales au temps de la retraite. Une approche des inégalités et évolutions dans la vieillesse. In Burnay N., Hummel C. (Eds.), L’impensé des classes sociales dans le processus de vieillissement (pp. 141–170). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Baeriswyl M. (2018). L’engagement collectif des aînés au prisme du genre: Evolutions et enjeux. Gérontologie et Société, 40/157(3), 53–78. 10.3917/gs1.157.0053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baeriswyl M., Oris M. (2021). Social participation and life satisfaction among older adults: Diversity of practices and social inequality in Switzerland. Ageing & Society, 1–25. 10.1017/S0144686X21001057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck U., Willms J. (2004). Conversations with Ulrich Beck. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel J.-F. (2014). La participation sociale, une action située entre biographie, histoire et structures. In Hummel C., Mallon I., Caradec V. (Eds.), Vieillesses et vieillissements. Regards sociologiques (pp. 207–226). Presses universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Bidart C. (1997). L’amitié, un lien social. Ed. La Découverte.

- Bidart C. (2010). Les âges de l’amitié. Transversalités, 113(1), 65–81. 10.3917/trans.113.0065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R., Roberto K. A. (2004). Friendship across the life span: Reciprocity in individual and relationship development. In Lang F., Fingerman K. L. (Eds.), Growing together: Personal relationships across the life span (pp. 159–182). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H.-P., Shavit Y. (2010). Persisting barriers. Changes in educational opportunities in thirteen countries. In Arum R., Beattie I. R., Ford K. (Eds.), The structure of schooling: Readings in the sociology of education (pp. 214–227). Pine Forge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. H. (1979). Neighbors and friends: An overlooked resource in the informal support system. Research on Aging, 1(4), 434–463. 10.1177/016402757914002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., Moorman S. M. (2011). Social relations and aging. In Settersten R. A., Angel J. L. (Eds.), Handbook of sociology of aging (pp. 145–160). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7374-0_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In Jacobs J. E. (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation 1992. Developmental perspectives on motivation (Vol. 40, pp. 209–254). University of Nebraska Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattacin S. (2006). Retard, rattrapage, normalisation. L’Etat social suisse face aux défis de transformation de la sécurité sociale. Studien und Quellen, 31, 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers P. (2018). Older widows and the life course: Multiple narratives of hidden lives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D. (2020). Systemic and reflexive: Foundations of cumulative dis/advantage and life-course processes. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(6), 1249–1263. 10.1093/geronb/gby118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewelies J., Huxhold O., Gerstorf D. (2019). The role of historical change for adult development and aging: Towards a theoretical framework about the how and the why. Psychology and Aging, 34(8), 1021–1039. 10.1037/pag0000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin A. (2020). Les origines du baby-boom en suisse au prisme des parcours féminins. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Elias N. (1991). The society of individuals (E. Jephcott, trans.). Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori K. L., Windsor T. D., Huxhold O. (2020). The increasing importance of friendship in late life: Understanding the role of sociohistorical context in social development. Gerontology, 66(3), 286–294. 10.1159/000505547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel R., Oris M., Studer M., Baeriswyl M. (2015). The persistence of social stratification? A life course perspective on old-age poverty in Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Sociology, 41(3), 465–487. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gourdon V. (2015). Les baby-boomers français, de “nouveaux grands-parents”? In Bonvalet C., Olazabal I., Oris M. (Eds.), Les baby-boomers, une histoire de familles. Une comparaison Québec-France (pp. 203–229). Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Grossetti M. (2005). Where do social relations come from? A study of personal networks in the Toulouse area of France. Social Networks, 27(4), 289–300. 10.1016/j.socnet.2004.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. E., Waite L. J., LaPierre T. A., Luo Y. (2007). All in the family: The impact of caring for grandchildren on grandparents’ health. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 62(2), S108–S119. 10.1093/geronb/62.2.S108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxhold O. (2019). Gauging effects of historical differences on aging trajectories: The increasing importance of friendships. Psychology and Aging, 34(8), 1170–1184. 10.1037/pag0000390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxhold O., Miche M., Schüz B. (2014). Benefits of having friends in older ages: Differential effects of informal social activities on well-being in middle-aged and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69(3), 366–375. 10.1093/geronb/gbt029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L., Hudson S. V., Leventhal H. (1999). The meanings of self-ratings of health: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Research on Aging, 21(3), 458–476. 10.1177/0164027599213006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle A., Oris M., Baeriswyl M., Kliegel M. (2018). The relation of close friends to cognitive performance in old age: The mediating role of leisure activities. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(12), 1753–1758. 10.1017/S1041610218000789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M. (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 69(3), 307–316. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. (2010). Close companion friends, self-expression, and psychological well-being in late life. Social Indicators Research, 95(2), 199–213. 10.1007/s11205-008-9358-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lalive d’Epinay C., Bickel J.-F., Maystre C., Vollenwyder N. (2000). Vieillesses au fil du temps, 1979-1994. Une révolution tranquille. Réalités sociales.

- Lalive d’Epinay C., Christe E., Coenen-Huther J., Hagmann H.-M., Jeanneret O., Junod J.-P., Kellerhals J., Raymond L., Schellhorn J.-P., Wirth G., de Wurstenberger B. (1983). Vieillesses: Situations, itinéraires et modes de vie des personnes âgées aujourd’hui. Ed. Georgi.

- Long J. S. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata (3rd ed). Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig C., Cavalli S., Oris M. (2014). “Vivre/Leben/Vivere”: An interdisciplinary survey addressing progress and inequalities of aging over the past 30 years in Switzerland. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 59(2), 240–248. 10.1016/j.archger.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher K., Pillemer K. (1998). Intergenerational ambivalence: A new approach to the study of parent-child relations in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60(2), 413–425. 10.2307/353858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S. H. (1983). Definitions of friendship and their consequences in old age. Ageing and Society, 3(2), 141–155. 10.1017/S0144686X00009983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monnot C. (2013). Croire ensemble. Analyse institutionnelle du paysage religieux en Suisse. Seismo.

- Mood C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82. 10.1093/esr/jcp006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom J. T., Rook K. S., Nishishiba M., Sorkin D. H., Mahan T. L. (2005). Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: Examining specific domains and appraisals. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(6), P304–P312. 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet M. (2018). Quand l’entourage annonce la mort d’un proche: Les avis de décès comme révélateurs de nos représentations de la mort dans la vieillesse [University of Geneva]. 10.13097/archive-ouverte/unige:110931 [DOI]

- Office fédéral de la statistique [OFS]. (n.d.). Atlas statistique de la Suisse Available online at https://www.atlas.bfs.admin.ch/fr/index.html [Accessed February 25, 2022]

- O’Rand A. M. (2006). Stratification and the life course: Life course capital, life course risks, and social inequality. In R. H. Binstock, L. K. George. (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (pp. 145–162) Elsevier. 10.1016/B978-012088388-2/50012-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oris M. (2017). Vulnerability. A life course perspective. Revue de Droit Comparé Du Travail et de La Sécurité Sociale, 4, 6–17. 10.4000/rdctss.2224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oris M., Baeriswyl M., Ihle A. (2021). The life course construction of inequalities in health and wealth in old age. In Rojo-Pérez F., Fernandez-Mayoralas G. (Eds.), Handbook of active ageing and quality of life: From concepts to applications (pp. 97–109). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-030-58031-5_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oris M., Gabriel R., Ritschard G., Kliegel M. (2017). Long lives and old age poverty: Social stratification and life-course institutionalization in Switzerland. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 68–87. 10.1080/15427609.2016.1268890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oris M., Guichard E., Nicolet M., Gabriel R., Tholomier A., Monnot C., Fagot D., Joye D. (2016). Representation of vulnerability and the elderly. A total survey error perspective on the VLV survey. In Oris M., Roberts C., Joye D., Ernst-Stähli M. (Eds.), Surveying human vulnerabilities across the life course (pp. 27–64). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oris M., Lerch M. (2009). La transition ultime. Longévité et mortalité aux grands âges dans le bassin lémanique. In Oris M., Widmer E. D., De Ribaupierre A., Joye D., Spini D., Labouvie-Vief G., Falter J.-M. (Eds.), Transitions dans les parcours de vie et construction des inégalités (pp. 407–433). Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins W. K. (1992). Friendship matters: Communication, dialectics, and the life course (1 edition). Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins W. K. (2004). Friendship in later life. In Nussbaum J. F., Coupland J. (Eds.), Handbook of communication and aging research (pp. 273–299). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Remund A., Cullati S., Sieber S., Burton-Jeangros C., Oris M. (2019). Longer and healthier lives for all? Successes and failures of a universal consumer-driven healthcare system, Switzerland, 1990–2014. International Journal of Public Health, 64(8), 1173–1181. 10.1007/s00038-019-01290-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. G. B., Dunbar R. I. M. (2011). The costs of family and friends: An 18-month longitudinal study of relationship maintenance and decay. Evolution and Human Behavior, 3(32), 186–197. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E., Litwin H. (2018). Social network changes among older Europeans: The role of gender. European Journal of Ageing, 15(4), 359–367. 10.1007/s10433-017-0454-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuey and K. M., Willson A. E. (2021). The life course perspective. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Medical Sociology, 171–191. 10.1002/9781119633808.ch9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2011). Stata 12 survey data reference manual. Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens N. L., Van Tilburg T. G. (2011). Cohort differences in having and retaining friends in personal networks in later life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(1), 24–43. 10.1177/0265407510386191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suanet B., Huxhold O. (2020). Cohort difference in age-related trajectories in network size in old age: Are networks expanding? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(1), 137–147. 10.1093/geronb/gbx166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suanet B., van Tilburg T. G., van Groenou B. M. I. B (2013). Nonkin in older adults’ personal networks: More important among later cohorts? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 68(4), 633–643. 10.1093/geronb/gbt043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K., Adams R. G. (2006). Adult friendship: A decade review. In Close relationships: Functions, forms and processes (pp. 151–169). Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. (2002). A strategy for active ageing. International Social Security Review, 55(1), 121–139. 10.1111/1468-246X.00118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]