Abstract

Enterococci are Gram-positive bacteria that can be isolated from a variety of environments including soil, water, plants, and the intestinal tract of humans and animals. Although they are considered commensals in humans, Enterococcus spp. are important opportunistic pathogens. Due to their presence and persistence in diverse environments, Enterococcus spp. are ideal for studying antimicrobial resistance (AMR) from the One Health perspective. We undertook a comparative genomic analysis of the virulome, resistome, mobilome, and the association between the resistome and mobilome of 246 E. faecium and 376 E. faecalis recovered from livestock (swine, beef cattle, poultry, dairy cattle), human clinical samples, municipal wastewater, and environmental sources. Comparative genomics of E. faecium and E. faecalis identified 31 and 34 different antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), with 62% and 68% of the isolates having plasmid-associated ARGs, respectively. Across the One Health continuum, tetracycline (tetL and tetM) and macrolide resistance (ermB) were commonly identified in E. faecium and E. faecalis. These ARGs were frequently associated with mobile genetic elements along with other ARGs conferring resistance against aminoglycosides [ant(6)-la, aph(3′)-IIIa], lincosamides [lnuG, lsaE], and streptogramins (sat4). Study of the core E. faecium genome identified two main clades, clade ‘A’ and ‘B’, with clade A isolates primarily originating from humans and municipal wastewater and carrying more virulence genes and ARGs related to category I antimicrobials. Overall, despite differences in antimicrobial usage across the continuum, tetracycline and macrolide resistance genes persisted in all sectors.

Keywords: comparative genomics, antimicrobial resistance, enterococci, livestock, One Health

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is defined as the ability of the bacterial cell to avoid cell damage by antimicrobials [1]. Some bacteria are naturally resistant to certain antimicrobials through intrinsic or inherent traits. Antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) conferring intrinsic resistance are mostly passed through clonal inheritance and are rarely transferred within or among bacterial populations. However, some ARGs can be acquired and associated with mobile genetic elements (MGEs) including plasmids, transposons, and integrative and conjugative elements. These ARGs can be transferred to other bacteria through horizontal gene transfer [2] and thus contribute to the spread of AMR in different ecosystems [3]. Exposure of bacteria to antimicrobials can facilitate ARG acquisition and the proliferation of resistant populations within ecosystems [4]. In animal production, sub-therapeutic administration of antimicrobials through feed and water to treat or prevent infectious diseases is one example of a practice that can increase AMR. Indeed, the imposed selective pressure can exacerbate AMR in gut microbiomes as large numbers of bacterial members that carry ARGs on MGEs [5] may facilitate their dissemination, including transfer to pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, multiple organizations, including the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS), European Antimicrobial Susceptibility Surveillance in Animals (EASSA), Japanese veterinary antimicrobial resistance monitoring systems (JVARM), and the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS) in the United States are monitoring antimicrobial resistance in food animals and assessing their role in the dissemination of AMR to bacteria associated with humans.

Enterococci are commensal bacteria within the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals [6]. They can also be recovered from broader natural environments, including soil, water, and plants. Some enterococcal species, particularly Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium, are considered human pathogens as they are frequently associated with bacteremia, septicemia, meningitis, endocarditis, and urinary tract and wound infections [7]. The presence of Enterococcus spp. in different ecosystems makes them an ideal species to study AMR from a One Health perspective. We investigated the prevalence and nature of Enterococcus species recovered from swine feces and undertook a comparative analysis of E. faecium and E. faecalis genomes sourced across various sectors of the One Health continuum. More specifically, we evaluated (i) profiles of ARGs, MGEs, and virulence factors of these genomes, (ii) the association of MGEs with ARGs, and (iii) the phylogenetic relatedness of the isolates collected across different sectors.

2. Methodology

2.1. Enterococcus Recovery from Swine Feces and Whole Genome Sequencing

In 2017 and 2018, fecal samples were collected from sows, and weaning and finishing pigs raised on commercial antimicrobial-free farms, as well as conventional farms using penicillin prophylaxis in Quebec, Canada. Isolates were collected at the same time that Enterobacterales isolates were collected in a previous study [8]. Presumptive Enterococcus isolates were recovered from collected samples on Bile Esculin Azide (BEA) agar with and without erythromycin (8 µg/mL) as described previously [9] and a total of 41 isolates were confirmed to be Enterococcus species following PCR with Ent-ES-211-233-F and Ent-EL-74-95-R primers and Sanger sequencing of the PCR product [9]. Confirmed isolates were subjected to short-read Illumina sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted using a Maxwell 16 Cell SEV DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as per manufacturer’s instructions, followed by DNA quantification using a Quant-it High-Sensitivity DNA assay kit (Life Technologies Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada). One nanogram of gDNA was used for genomic library construction using an Illumina NexteraXT DNA sample preparation kit and the Nextera XT Index kit (Illumina Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. All libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Miseq platform generating 2 × 300 base-paired end reads with a 600-cycle MiSeq reagent kit v3 (Illumina).

2.2. Collection of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis Genomes

A total of 622 E. faecium and E. faecalis genomes were included for comparative genomic analysis. These genomes originated from three sources: (i) swine isolates from this study (n = 18), (ii) a collection of genomes recovered from environmental and livestock isolates from Ontario (n = 66), and (iii) previously published data from poultry (n = 32) [10] and One Health continuum (n = 506) [9] studies. The number and the origin of E. faecium and E. faecalis genomes included in the analysis are summarized in Table 1. E. faecium and E. faecalis genomes were categorized into four groups/sectors based on their origin: (i) clinical, (ii) municipal wastewater, (iii) livestock, and (iv) environment.

Table 1.

Collection of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis genomes included in the comparative genomic analysis and antimicrobials used in livestock.

| Sources of Genome | Number of Genome | Antimicrobial Usage | Location (Year of Sample Collection) |

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. faecium (n = 246) |

E. faecalis (n = 376) |

|||||

| Municipal waste water (MW) | 56 | 110 | - | Alberta (March 2014–April 2016) |

[9] | |

| Clinical isolates (CL) | 36 | 149 | - | |||

| Livestock (LS) | Bovine cattle | 57 | 33 | Conventional (tetracycline, macrolides), natural (antibiotic-free) |

||

| Dairy cattle | - | 22 | NA | Ontario (2004) |

This study | |

| Swine | - | 06 | NA | |||

| 12 | 06 | Conventional (penicillin), antibiotic-free (organic, certified-humane, AGRO-COM) |

Quebec (2017–2018) |

|||

| Poultry | 23 | 09 | Bambermycin, bacitracin, salinomycin, and β-lactams | British Colombia (2005–2008) |

[10] | |

| - | 05 | NA | Ontario (2004) |

This study | ||

| Environment (EV) | Natural water sources | 46 | 19 | - | Alberta (March 2014–April 2016) |

[9] |

| River water | 16 | 07 | - | Ontario (2004) |

This study | |

| Domestic animals | - | 03 | NA | |||

| Wild animals | - | 07 | - | |||

2.3. Genome Assembly and Data Analysis

All enterococcal genomes included in this study were assembled de novo using the Shovill pipeline v.1.1.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/shovill accessed on 15 November 2022). Illumina adapters were removed using Trimmomatic v.0.36.5 [11]. All reads were then assembled de novo into contigs by SPAdes v.3.11.1 [12]. Assembly was evaluated by QUAST version 5.2.0 [13]. The contigs were then annotated using Prokka v.1.13.1 [14].

The annotated genomes were screened for the presence of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes using ABRicate v.1.0.1 (https://github.com/tseemann/ABRICATE accessed on 20 November 2022) against the NCBI Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance Reference Gene Database (NCBI BioProject ID: PRJNA313047) and the VirulenceFinder database (PMID: 34850947) [15], respectively. All contigs were screened for the presence of plasmids using Mob-recon version 3.0.0 (https://github.com/phac-nml/mob-suite accessed on 10 January 2023) [16].

E. faecium (n = 246) and E. faecalis (n = 376) genomes were used for comparative genomics (Table 1). The core-genome phylogenomic trees were constructed using the SNVphyl pipeline version 1.2.3. The phylogenetic tree was generated by aligning paired-end Illumina reads against the respective reference genomes of E. faecalis (strain ATCC 47077/OG1RF; CP002621.1) and E. faecium (strain DO; CP003583.1) using SMALT (version 0.7.5; https://sourceforge.net/projects/smalt/ accessed on 12 January 2023). The generated read pileups were then subjected to quality filtering (minimum mean mapping quality score of 30), coverage cut-offs (15× minimum depth of coverage), and a single nucleotide variant (SNV) abundance ratio filter of 0.75 to obtain a multiple sequence alignment of SNV-containing sites. This SNV alignment (with no SNV density filtering) was used to create a maximum likelihood phylogeny using PhyML version 3.0. The generated Newick file was visualized using Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) version 6 [17].

Additionally, for E. faecium genomes, a groEL-based tree was constructed to investigate whether the genomes could be assigned to previously described hospital (clade A) or community (clade B) clades [18]. The extracted groEL gene sequence was aligned with E. faecium strain 75 V68 (Clade A) and E. faecium strain 81 (Clade B) using MAFFT version 7.490. The analysis included the E. hirae R17 (accession CP015516.1) groEL gene as an outgroup. The maximum-likelihood tree was then created with IQTree version 2.1.4.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was also used to study the population structure and evolution of bacterial species. E. faecium and E. faecalis sequence types were assigned through the MLST scheme of each respective species using PubMLST tool (http://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST/ accessed on 15 January 2023) [19].

3. Results

3.1. Enterococci Recovered from Swine Feces

3.1.1. Species Identification

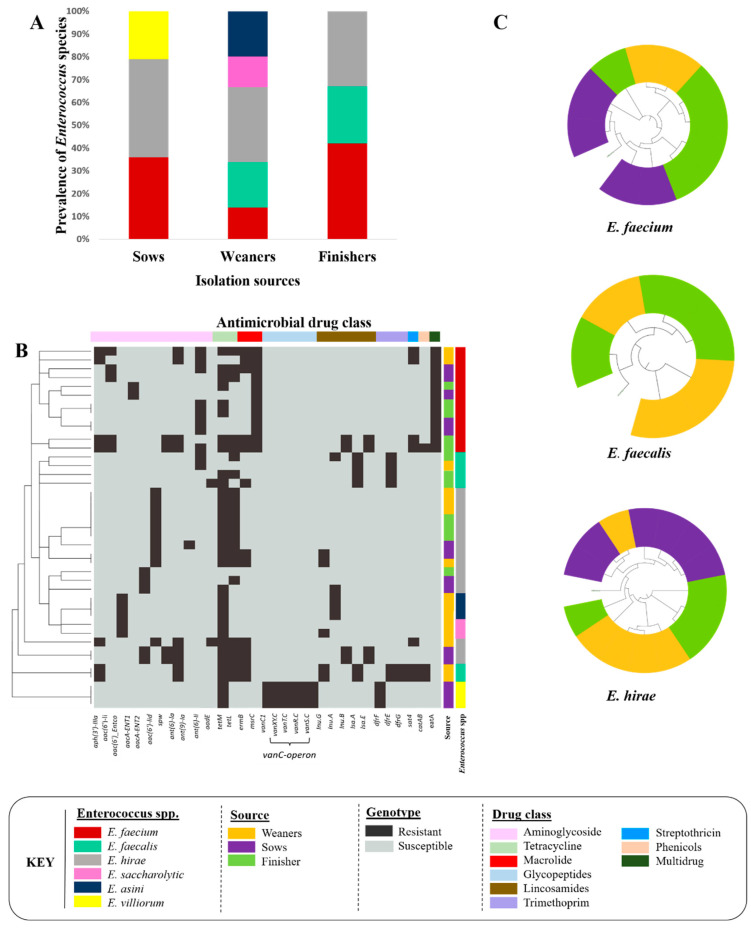

Of the Enterococcus spp. recovered from fecal samples, 14 isolates were from sows, 15 isolates were from weaners, and 12 isolates were from finishers. Six different enterococcal species were identified [E. hirae (n = 15), E. faecium (n = 12), E. faecalis (n = 6), E. saccharolyticus (n = 3), E. villorum (n = 3), and E. asini (n = 2)] (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Enterococcus species recovered from fecal samples collected from sows (n = 14), and weaning (n = 15) and finishing (n = 12) pigs. (A) Prevalence of Enterococcus species. (B) Antimicrobial resistance gene profiles of Enterococcus isolates. (C) Core-genome-based phylogenetic tree of E. faecium (n = 12), E. faecalis (n = 6), and E. hirae (n = 15) recovered from different pig production stages.

3.1.2. Genome Characterization

Across all isolates, 27 different ARGs/determinants were identified (Figure 1B). Overall, 39% of the identified enterococcal species were multidrug-resistant (MDR, resistant to ≥ 3 antimicrobials). MDR isolates were confined to three species: E. faecalis (67%), E. hirae (47%), and E. faecium (41%) (Table 2). The most common ARGs in E. faecium, E. faecalis, and E. hirae were associated with resistance to aminoglycoside (aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-Ia), tetracycline (tetL, tetM), macrolide (ermB), and streptothricin (sat4) drug classes.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance genes profiles, plasmids harboring AMR genes, and virulence genes identified in enterococcal species recovered from swine feces.

| Enterococcal Species | *& Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Profile (Number of Genomes) |

Plasmids (Accession Number) (Total) |

Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Found on Plasmid | Virulence Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-la, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnu(G), dfrG, sat4, catA8 (n = 2) | pBEE99 (NC_013533) (n = 2) |

All ARGs |

|

| tetL, tetM (n = 1) | pSWS47 (NC_022618.1) (n = 1) | All ARGs | ||

| aadE, tetM, ermB (n = 1) | None | None | ||

| tetL, lnu(A) (n = 1) | None | None | ||

| E. faecium | aph(3′)-IIIa, spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnu(B), lsa(E), sat4, catA8 (n = 1) | pM7M2 (NC_016009) (n = 4) |

tetL, tetM |

|

| aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-Ia, tetL, tetM, ermB, sat4 (n = 1) | ||||

| tetL, tetM, ermB (n = 1) | ||||

| tetL, tetM (n = 1) | ||||

| aph(3′)-IIIa, spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnu(B), lsa(E), sat4 (n = 1) | pLAG (KY264168.1) (n = 1) |

ant(6)-Ia, tetM, tetL, lnu(B), lsa(E) | ||

| aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-Ia, ermB, sat4 (n = 1) | None | None | ||

| tetM (n = 3) | None | None | ||

| E. hirae | aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-Ia, aadE, tetL, tetM, ermB, sat4 (n = 1) | p3 (CP006623) (n = 1) |

aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-Ia, ermB, sat4 |

|

| pBC16 (U32369) (n = 1) |

tetM | |||

| spw, ant(6)-Ia, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, lsaE (n = 2) | pEf37BA (MG957432) (n = 2) | All ARGs | ||

| tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuG (n = 2) | pDO1 (CP003584) (n = 2) | tetL, tetM, ermB | ||

| ant(9)-Ia, tetL, tetM (n = 1) | pM7M2 (NC_016009) (n = 1) |

tetL, tetM | ||

| tetL, tetM (n = 7) | pM7M2 (NC_016009) (n = 3) |

tetL, tetM | ||

| pCTN1046 (CP007650) (n = 1) | tetM | |||

| pBC16 (U32369) (n = 1) |

tetL | |||

| tetM, lnuA (n = 1) | (CP029969) (n = 1) | lnu(A) | ||

| E. asini | tetM, lnuG (n = 1) | None | None |

|

| tetM (n = 1) | None | None | ||

| E. villorum | tetM, lsaA (n = 3) | None | None | None |

| E. saccharolyticus | tetM (n = 3) | None | None |

|

* Antimicrobial drug classes and resistance genes: aminoglycoside (ant(9)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(6)-Ia, aadE, spw); tetracycline (tetL, tetM); macrolide (ermB), lincosamide ARG (lnuA, lnuG, lsaA, lsaE), chloramphenicol (catA8), trimethprim (dfrG). & All ARGs except for those shown in column 4 were mapped onto chromosomes.

Nine out of the twenty-seven ARGs conferred intrinsic/inherent resistance, including msrC (100%), eat(A) (100%), and aac(6′)-li (41.6%) in E. faecium; lsa(A) (100%) and dfrE (100%) in E. faecalis; aac(6′)-lid (66.6%) in E. hirae; dfrF (100%) and vanC-operon (100%) in E. saccharolyticus; and aac(6′)-Entco (100%) in E. villorum and E. asini. The three genes, aacA-ENT1, dfrG, and aacA-ENT2, were only identified in E. faecium (16.6%), E. faecalis (33.3%), and E. hirae (33.3%), respectively.

A total of 35 plasmids were identified in Enterococcus spp. [E. faecalis (n = 10), E. faecium (n = 12), and E. hirae (n = 13)] (Table 2). Among these, 11 plasmids harbored ARGs [E. faecalis (n = 2), E. faecium (n = 2), and E. hirae (n = 7)] (Table 2). A total of 34 and 13 virulence genes were identified in E. faecalis and E. faecium, respectively. Most virulence genes were associated with cytolysis, biofilms, and capsule formation (Table 2). The E. faecium core-genome phylogenetic tree formed two distinct clades, where all genomes except two recovered from sows and finishers, were found in one clade. E. faecalis also clustered into two clades, where one clade exclusively contained genomes from weaners. As for E. hirae, one clade contained all genomes except two isolated from finishers (Figure 1C).

3.2. Comparative Genomic Analysis of E. faecalis and E. faecium across the One Health Continuum

3.2.1. Livestock Production

Comparative genomic analysis of E. faecium (n = 91) and E. faecalis (n = 81) collected from cattle, poultry, and swine was performed to investigate similarities and differences in the resistome, virulome, and mobilome profiles as well as the phylogenetic relatedness across the production sectors.

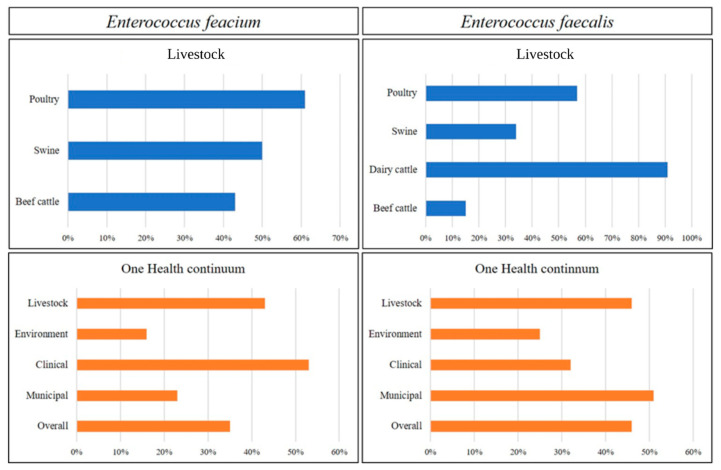

Overall, 48% of E. faecium genomes from livestock were MDR (resistant to ≥3 antimicrobials). Among livestock, E. faecium from poultry had the highest incidence of MDR (61%), followed by swine (50%) and beef cattle (43%) (Figure 2). Among E. faecium of bovine origin, two ARG profiles [(ermB, tetL, tetM) and (ant(6)-Ia, spw, ermB, lnuB, lsaE, tetL, tetM)] were the most frequent (Supplementary Table S1). Isolates harboring dfrE were frequently identified in all sectors. Two ARG profiles [(dfrE, tetL, tetM) and (dfrE, ermB, tetL, tetM)] were present in both swine and poultry, while one profile (dfrE, ermB, and tetM) was common to bovine and poultry isolates. Across livestock, chloramphenicol (fexA and catA) and oxazolidinone-resistant determinants (optrA) were exclusively found in E. faecium from cattle, whereas the vanC-operon was unique to poultry isolates. Aminoglycoside ARGs [ant(6)-Ia, ant(9)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, and spw] were more prevalent in E. faecium isolated from poultry compared to other sectors (Figure 3A). In contrast, tetracycline ARGs (tetL and tetM) were found more frequently in E. faecium from cattle than those from poultry and swine. Moreover, E. faecium isolates from cattle and poultry shared similar ARGs associated with macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin (MLS) resistance (ermA, ermB, lnuB, lnuG, lsaG, and sat4). In E. faecium from swine, only four ARGs associated with MLS resistance (ermB, lsaG, mefA, and sat4) were identified. Across livestock, ermB (57%) was most prevalent in isolates from cattle. In contrast, the trimethoprim-resistant determinant dfrE was found in all E. faecium genomes recovered from swine and 82.6% from poultry. Compared to other sectors, drfE and dfrG were infrequently associated with E. faecium isolated from cattle.

Figure 2.

Multidrug resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis across One Health continuum.

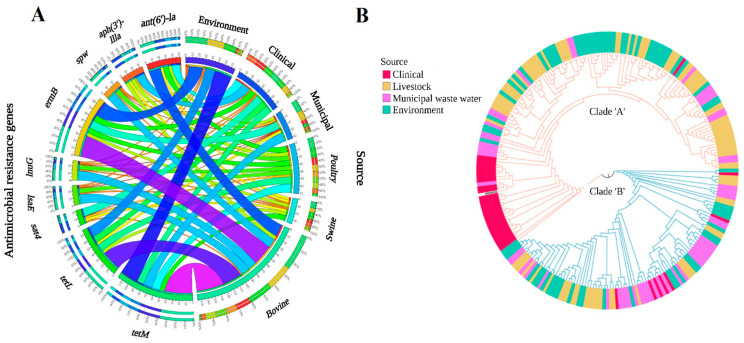

Figure 3.

Comparative genomic analysis of 246 E. faecium genomes across the One Health continuum. (A) Circos plot depicts the relationship between commonly found ARGs and One-Health sectors. The variables (ARGs and genome isolation source) are arranged around the circle and distinguished by different colors. The percentage of ARGs across various sectors is indicated by proportional bars (http://circos.ca/). (B) Maximum likelihood core-genome phylogenetic tree. The Enterococcus faecium DO genome (CP003583.1) was used as a reference genome. The gro-EL gene-based E. faecium tree was overlaid on the core-genome E. faecium tree. Genomes were characterized based on their source of isolation into four groups: livestock, clinical, municipal wastewater, and environmental.

Mobilome analysis of E. faecium genomes showed that >60% of ARG-carrying plasmids were associated with isolates from cattle (Supplementary Table S2). Among these, pL8-A and pM7M2 were also found in poultry and swine isolates, respectively. MLST profiling identified 33 different genomic sequence types (STs) across the enterococci genomes, with 13 STs exclusive to beef cattle. In swine, only 3 STs were identified (ST94, ST133, ST272). In E. faecium from poultry, 10 STs were identified, with ST154 being the most common. None of the STs were shared across all livestock species (Table S3).

The virulome of E. faecium did not vary across livestock species. The majority of virulence genes, including those responsible for biofilm formation (bopD, clpC, clpP), bile-salt hydrolysis (bsh), capsule formation (cap8F, cpsA, cpsB, and hasC), MSCRAMM-like proteins (sgrA), and pili formation (srtC) were found in >70% of the genomes of E. faecium from livestock. Two genes, ebpA and lap (encoding biofilm-associated pili), and a Listeria adhesion protein were identified in one poultry isolate (Supplementary Table S4).

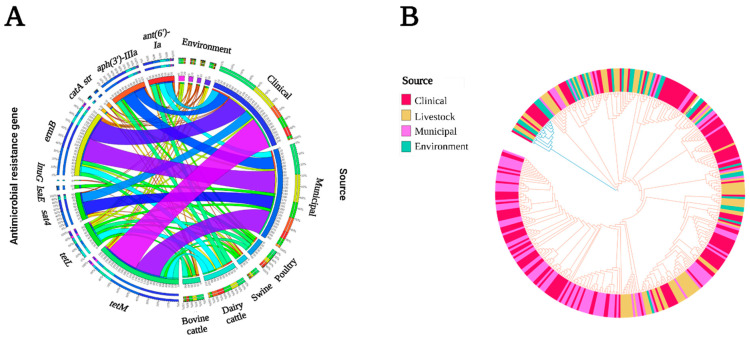

Overall, 46% of E. faecalis were MDR with the highest incidence of MDR associated with isolates from dairy cattle (91%) followed by poultry (57%), swine (34%), and beef cattle (15%) (Figure 2). One ARG profile (ermB, tetM, tetL) was found across all livestock species (Supplementary Table S5). The ARG profile ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, ermB, tetL, and tetM was present in 50% of poultry and 100% of E. faecalis genomes from dairy cattle. Similar to E. faecium, the oxazolidinone resistance gene (optrA) was occasionally (7% of genomes) present in E. faecalis isolated from cattle. The trimethoprim ARG (drfE) was mapped to 17% and 3% of E. faecalis isolates from swine and cattle, respectively, but was absent in poultry isolates. Chloramphenicol resistance profiles differed across sectors, as catA8 was found in isolates from swine, whereas catA7 was found in isolates from dairy cattle and catA7 and fexA in isolates from beef cattle. Similarly, the profile of aminoglycoside ARGs also varied across livestock species. Aminoglycoside ARGs were most prevalent in isolates from dairy cattle, followed by poultry, swine, and beef cattle. Two ARGs, ant(6)-la and aph(3′)-IIIa, were prevalent across livestock species, whereas aph(2″)-Ih and ant(9) were unique to isolates from dairy and beef cattle, respectively. The ARG str, was found only in isolates obtained from beef cattle and poultry. Similarly, aadE was found only in isolates from swine and beef cattle. Tetracycline resistance determinants (tetL and tetM) were found in isolates across livestock sectors (Figure 4A; Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 4.

Comparative genomic analysis of 376 genomes E. faecalis genomes across the One Health continuum. (A) Circos plot depicts the relationship between commonly found ARGs and One Health sectors. The variables (ARGs and genome isolation source) are arranged around the circle and distinguished by different colors. The percentage of ARGs across various sectors is indicated by proportional bars (http://circos.ca/). (B) Maximum likelihood core-genome phylogenetic tree. E. faecalis ATCC 47077/OG1RF (CP002621.1) was used as the reference genome. Genomes were characterized based on their source of isolation into four groups: livestock, clinical, municipal wastewater, and environmental.

Like E. faecium, plasmid profiling of E. faecalis found that 70% of isolates possessed plasmids that carried ARGs (Supplementary Table S6). Four ARG-carrying plasmids (DO plasmid, pCTN1046, p6742_2, pEf37BA, and pBC16) were found in both E. faecium and E. faecalis. Across livestock species, 29 STs were identified, with ST59 shared between swine, bovine, and dairy cattle isolates (Supplementary Table S7). Virulome profiles of E. faecium genomes were similar across livestock species (Supplementary Table S8). A total of 27 of the 39 virulence genes were mapped to several isolates collected across the livestock sectors (40–100% of genomes). Genes encoding cytolysin (cylA, cylB, cylI, cylL, cylM, cylR1, cylR2, and cylS) and the aggregation substance (asa1) were found in only one isolate from swine.

3.2.2. One Health Continuum

Across the continuum, 35% of E. faecium were MDR, with the highest incidence of MDR found in clinical (CL) isolates (53%), followed by livestock (LS) (48%), municipal wastewater (MW) (23%), and environmental (EV) isolates (16%) (Figure 2). The ARG profile dfrE, ermB, and tetM was most common among MDR E. faecium from LS, EV, and MW (Table S1). Aminoglycoside resistance genes were most prevalent in clinical genomes, followed by LS, MW, and EV (Figure 3A). Three aminoglycoside resistance genes, ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, and spw, were found across the One Health continuum, with ant(6)-Ia and aph(3′)-IIIa being frequently mapped to plasmids (73% and 61%, respectively). These genes were found together in 91% of genomes. The bifunctional gene aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia, was found only in CL (5/36, 14%) and MW (3/56, 5.3%) isolates. Genomes harboring aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia were associated with five different plasmids (Supplementary Table S6). This gene was exclusively associated with an IS256 insertion element, except for one plasmid associated with IS6 and IS1216 in combination with ermB and dfrG. Chloramphenicol resistance was found in LS and MW isolates but not among those from other sources. The ARG fexA was associated with Tn554 on plasmid pFSIS1608820, and catA was mapped to two plasmids in MW isolates (Table S2). ARGs conferring resistance to trimethoprim were more prevalent in CL, followed by MW, LS, and EV. Compared to CL isolates, where dfrF and dfrG were more prevalent, dfrE was found in EV, LS, and MW isolates. In all but one dfrG-positive genome, fosX was found in an antisense direction to dfrG at an intergenic distance of ~3.2 kb. Macrolide–lincosamides–streptogramin-resistant genotypes were prevalent in LS, followed by CL, EV, and MW.

Four ARGs conferring macrolide resistance (ermA, ermB, ermT, and mefA) were identified across the continuum. The ARG ermB was associated with plasmids 73% of the time. Moreover, in isolates from CL and LS, ermB along with the aminoglycoside ARGs sat4, aph(3′)-IIIa, and ant(6)-la were associated with Tn3 transposons. Similarly, ermA was also identified on plasmid pL8-A along with ermB and ant(9)-la. The ARG ermA was also found on plasmid pFSIS1608820 with ant(9)-Ia, cfr, optrA, ermA, and fexA. In contrast, ermT mapped only to plasmid p121BS. The lincosamide-resistant genes lnuB and lsaE were found together on 87% of plasmids. Glycopeptide resistance was found in clinical and poultry genomes, where vanA was found in pV24-3 and pF856 plasmids (Supplementary Table S2).

The core-genome-based phylogenomic tree of E. faecium formed two clades that were completely superimposed with the A and B clades identified by the groEL gene maximum-likelihood tree (Figure 3B). E. faecium genomes did not group based on sample source, except for the clinical isolates in clade A. Furthermore, clade A harboured more virulence genes and ARGs than clade B. Multilocus sequence typing of E. faecium genomes identified 72 different STs (Supplementary Table S3), with ST117 and ST17 being exclusive to human clinical isolates. Across the continuum, 37 virulence genes were identified, of which 15 were found in genomes from all sectors (Supplementary Table S4).

Overall, 40% of E. faecalis were MDR, with MDR isolates being most frequent in MW (51%) followed by LS (46%), EV (25%), and CL (32%) (Figure 2). Across all sectors, ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, ermB, tetL, and tetM were frequently identified in MDR E. faecalis genomes (Supplementary Table S5). A total of 51 plasmids carrying one or more ARGs were identified (Supplementary Table S6). Among these plasmids, two were conjugative plasmids (related to AY855841 and CP028721), and two were identified as mobilizable plasmids (related to CP028286 and CP028836). Aminoglycoside ARGs were more prevalent in MW, followed by LS, CL, and EV (Figure 4A). Across all sectors, eight aminoglycoside ARGs were identified, with five (ant(6)-Ia, aph(2″)-Ih, aph(3′)-IIIa, and str) found in all sectors. Similar to E. faecium, ant(6)-Ia and aph(3′)-IIIa were frequently found together (61 genomes) and mapped to plasmids (71% and 75% of isolates, respectively). Chloramphenicol resistance genes were more prevalent in LS, followed by EV, CL, and MW. Five ARGs (catA7, catA8, catP, cat-TC, and fexA) were identified, with catA7, catA8, and fexA present in all sectors. These three genes were always associated with plasmids (Supplementary Table S6). Trimethoprim ARGs (dfrF/G) were identified more frequently in CL compared to other sectors, with dfrF found in >60% of CL genomes (19% on a plasmid). Across all sectors, MLS resistance was more prevalent in MW, followed by LS, CL, and EV. Three ARGs responsible for macrolide resistance (erm A, ermB, and msr) were identified, with ermB present in 60% of all genomes and frequently associated with plasmids (75%). One ermB-carrying plasmid, CP024844, was found exclusively in CL and MW genomes (40% ermB-positive isolates). Lincosamide ARGs were not found in EV genomes, whereas in CL genomes, only lnuB was identified. Tetracycline resistance was found more frequently in LS genomes, followed by EV, CL, and MW. Five different tetracycline ARGs were identified (tetM, tetL, tetO, tetS, and tetW), with tetM mapping to 76.5% of the genomes. Compared to tetM (18%), tetL (85%) was more frequently found on plasmids. Moreover, in 85% of tetM-positive plasmids, tetL was found together in close proximity with tetM. One tetM- and tetL-carrying plasmid, pS7316, was also prevalent in isolates from LS, CL, and EV. Oxazolidinone resistance ARGs were found only in EV and LS, which were more prevalent in EV than LS. In EV, two ARGs (optrA and cfrC) were identified, whereas in LS, only optrA was found.

Across the continuum, the core-genome-based E. faecalis phylogenomic tree formed two main clades, where one clade contained the majority of CW and MW genomes (Figure 4B). MLST profiling of E. faecalis identified 75 different STs (Supplementary Table S7), where 48 STs were source-specific (CL = 17, LS = 14, EV = 8, MW = 9). We identified 40 virulence genes across all E. faecalis genomes, with 28 shared across all sectors (Supplementary Table S8).

4. Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance is a serious concern for human and animal health and the global economy. One Health approaches to assess AMR recognize the role of multiple ecosystems in generating and spreading antimicrobial resistance genes [2]. In One Health studies, Enterococcus species have been used as ‘indicator bacteria’ to monitor ARG dissemination in ecosystems. In this study, we performed genomic characterization of Enterococcus species recovered from feces of weaners, finishers, and sows. Furthermore, we evaluated the ARGs identified in E. faecium and E. faecalis genomes across livestock and poultry production systems and cumulatively across the overall One Health continuum.

E. hirae was predominantly identified in swine feces, followed by E. faecium and E. faecalis. In studies from the US and Canada, E. hirae was frequently recovered from livestock [9,20]. In poultry, E. faecium has been isolated most frequently [21] and along with E. faecium and E. faecalis are often associated with human infections [9]. In all identified enterococcal species, tetracycline resistance determinants tetL and tetM were frequently found on the mobile plasmid pM7M2 (NC_016009). This plasmid has been previously identified in E. faecalis isolated from dairy cattle feces and was shown to transfer into Streptococcus mutans UA159 through natural transformation [22]. These findings show that these three Enterococcus spp. (i.e., E. faecium, E. faecalis, and E. hirae) can readily acquire ARGs in the gut micro-environment and possibly contribute to gene dissemination through plasmid-mediated ARG transfer.

We aimed to define the impact of differences in AMU across different livestock sectors on the occurrence of ARGs within enterococci. Across all livestock sectors, isolates from bovine sources had the lowest incidence of MDR, which may reflect the extent of antimicrobial usage in this livestock sector in Canada. According to the CIPARS 2019 report, most antimicrobials are administered to swine (<300 mg/PCU), followed by poultry (<200 mg/PCU) and cattle (<100 mg/PCU) (CIPARS, 2019). Regardless of the high MDR in poultry isolates, we did not find any isolates of poultry origin carrying ARGs conferring resistance to antimicrobials that were administered to poultry (Table 1). However, comparative genomics of enterococci identified that tetracycline and macrolide resistance genotypes were more prevalent in the beef production system compared to swine and poultry, a result that may reflect the greater use of these antimicrobials in beef cattle [23,24].

Mobile genetic elements play a significant role in gene dissemination within and across ecosystems. In our study, all ARGs, except those that were intrinsic, were mapped to plasmids in almost 80% E. faecium and E. faecalis isolates. Resistance to aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, trimethoprim, and MLS was identified across all ecosystems, with tetracycline and MLS being the most common. With these antimicrobials broadly used across sectors, the existence and persistence of resistant strains across the continuum is perhaps not surprising [25,26]. Their persistence may also be explained by the co-existence of these genes along with other ARGs, and other studies have found a strong association of tetracycline resistance ARGs (tetL and tetM) with other ARGs, including ermB, ant(6)-la, aph(3′)-IIIa, lnu(G), lsaE, and sat4 [27]. These ARGs were often found on MGEs that may facilitate their spread in different ecosystems. Continuous exposure to one antimicrobial class in a particular ecosystem can also select for ARGs conferring resistance to other antimicrobial classes [28,29,30].

Some antimicrobial resistance determinants were found in some sectors but not others. For example, aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia, which is associated with high-level gentamicin resistance (HLGR), was only identified in E. faecium genomes from CL and MW. However, the association of this gene with MGEs may facilitate its spread to other human pathogens as it mapped to five different plasmids and was frequently associated with IS256 elements. Previously, aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia was associated with IS256 on the Tn5281 composite transposon in a conjugative pBEM10 plasmid in E. faecalis [31], with Tn4001 on plasmid pSK1 in Staphylococcus aureus [32], and Tn4031 in Staphylococcus epidermidis [33]. Glycopeptide-resistant genes vanA and vanC were identified in clinical and poultry isolates. The vanA operon was mapped to two plasmids in CL isolates, pV24-3 and pF856. Along with the vanA-operon, other ARGs (ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, ermB, and sat4) were also mapped to pF856. This particular plasmid was first reported in a hospitalized patient associated with a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus outbreak in Ontario, Canada [34].

Our phylogenomic analysis revealed a similar topology of gro-EL-based [35] and core-genome-based trees, with E. faecium segregating into two main groups. Our core-genome tree topology partitioned into two clades. In contrast, in a recent study by Sanderson et al. [36], clade B formed a paraphyletic clade rather than a monophyletic clade. Our findings also agree with previous studies [35,36], as more ARGs and virulence genes were associated with clade A than clade B isolates. Furthermore, most of the genomes associated with CL isolates clustered in clade A. Phylogenetically, E. faecalis genomes did not cleanly partition into clades by source and instead formed multiple clades that originated from multiple sources.

In conclusion, our study suggests that some resistant strains are universally present in all ecosystems, irrespective of antimicrobial pressure. However, some ARGs are exclusive to particular ecosystems, reflecting antimicrobial usage within that sector. Moreover, we also found that co-selection and association of ARGs with different MGEs likely facilitate the spread of ARGs across the One Health continuum. In addition, clinical E. faecium isolates formed a distinct cluster and were consistently mapped to a hospital associated clade.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Frédéric Beaudoin and Daniel Plante for technical assistance and Guylaine Talbot for her support.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms11030727/s1, Table S1. Antimicrobial resistance genes profiles of E. faecium genomes; Table S2. List of plasmids harboring antimicrobial resistance genes identified in 246 E. faecium genomes; Table S3. Multilocus sequence types of 246 E. faecium genomes; Table S4 List of virulence genes identified in 246 E. faecium genomes; Table S5. Antimicrobial resistance gene profiles of E. faecalis genomes; Table S6. List of plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes identified in 376 E. faecalis genomes; Table S7. Multilocus sequence type profiles of 376 E. faecalis genomes; Table S8. List of virulence genes identified in 376 E. faecalis genomes.

Author Contributions

R.Z. and T.A.M., designed the study, D.P.-L. provided the data for swine isolates, M.A.R. and M.D. provided the data for poultry isolates, A.S. and E.T. provided the data for a subset of environmental isolates and G.V.D. provided and managed the bioinformatics tools and computing environment; S.-e.-Z.Z. and R.Z. analyzed sequence data; S.-e.-Z.Z. generated figures and analyzed overall data/results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and T.A.M., A.Z. and R.Z. provided funding and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The draft whole genome sequence assemblies of the Enterococcus spp. recovered from One Health sectors (clinical, bovine cattle, dairy cattle, swine, environment, municipal waste water) are available in GenBank under Bio Projects PRJNA604849. Whole genome sequence assemblies of Enterococcus spp. from poultry are available in GenBank under Bio Project PRJNA273513.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The authors are grateful to the Major Innovation Fund of the Government of Alberta in conjunction with the University of Calgary AMR One Health Consortium, the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) Project FOS 10.13, and the Genomics Research and Development Initiative (GRDI) of the Government of Canada for financial support.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Baquero F. Threats of antibiotic resistance: An obliged reappraisal. Int. Microbiol. 2021;24:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s10123-021-00184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White A., Hughes J.M. Critical Importance of a One Health Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance. EcoHealth. 2019;16:404–409. doi: 10.1007/s10393-019-01415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechner I.C., Freivogel K., Stärk K., Visschers V. Exposure Pathways to Antimicrobial Resistance at the Human-Animal Interface—A Qualitative Comparison of Swiss Expert and Consumer Opinions. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:345. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael C.A., Dominey-Howes D., Labbate M. The antimicrobial resistance crisis: Causes, consequences, and management. Front. Public Health. 2014;2:145. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn S.J., Connor C., McNally A. The evolution and transmission of multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: The complexity of clones and plasmids. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019;51:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebreton F., Willems R.J.L., Gilmore M.S. Enterococcus Diversity, Origins in Nature, and Gut Colonization. In: Gilmore M.S., Clewell D.B., Ike Y., Shankar N., editors. En-Terococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; Boston, MA, USA: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Solache M., Rice L.B. The Enterococcus: A Model of Adaptability to Its Environment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019;32:e00058-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulin-Laprade D., Brouard J.-S., Gagnon N., Turcotte A., Langlois A., Matte J.J., Carrillo C.D., Zaheer R., McAllister T.A., Topp E., et al. Resistance Determinants and Their Genetic Context in Enterobacteria from a Longitudinal Study of Pigs Reared under Various Husbandry Conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021;87:e02612-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02612-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaheer R., Cook S.R., Barbieri R., Goji N., Cameron A., Petkau A., Polo R.O., Tymensen L., Stamm C., Song J., et al. Surveillance of Enterococcus spp. Reveals Distinct Species and Antimicrobial Resistance Diversity across a One-Health Continuum. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:3937. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehman M.A., Yin X., Zaheer R., Goji N., Amoako K.K., McAllister T., Pritchard J., Topp E., Diarra M.S. Genotypes and Phenotypes of Enterococci Isolated from Broiler Chickens. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018;2:83. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2018.00083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. Spades: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. Quast: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu B., Zheng D., Zhou S., Chen L., Yang J. VFDB 2022: A general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;50:D912–D917. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson J., Nash J.H.E. MOB-suite: Software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018;4:e000206. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Letunic I., Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung W.-W. Using Groel as the Target for Identification of Enterococcus faecium Clades and 7 Clinically Relevant En-terococcus Species. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019;52:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolley K.A., Bray J.E., Maiden M.C.J. Open-Access Bacterial Population Genomics: BIGSdb Software, the PubMLST.org Website and Their Applications [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved] Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson C.R., Lombard J.E., Dargatz D.A., Fedorka-Cray P.J. Prevalence, species distribution and antimicrobial resistance of enterococci isolated from US dairy cattle. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;52:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diarra M.S., Rempel H., Champagne J., Masson L., Pritchard J., Topp E. Distribution of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes in Enterococcus spp. and Characterization of Isolates from Broiler Chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:8033–8043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01545-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X., Alvarez V., Harper W.J., Wang H.H. Persistent, Toxin-Antitoxin System-Independent, Tetracycline Resistance-Encoding Plasmid from a Dairy Enterococcus faecium Isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:7096–7103. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05168-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson C.A., Reid-Smith R., Irwin R.J., Martin W.S., McEwen S.A. Antimicrobial Use on 24 Beef Farms in Ontario. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2008;72:109–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CARSS Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) Report 2022. [(accessed on 25 January 2023)]. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-system-report-2022.html#a4.1.

- 25.Bartoloni A., Pallecchi L., Rodríguez H., Fernandez C., Mantella A., Bartalesi F., Strohmeyer M., Kristiansson C., Gotuzzo E., Paradisi F., et al. Antibiotic Resistance in a Very Remote Amazonas Community. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2009;33:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nejidat A., Diaz-Reck D., Gelfand I., Zaady E. Persistence and spread of tetracycline resistance genes and microbial community variations in the soil of animal corrals in a semi-arid planted forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021;97:fiab106. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiab106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefańska I., Kwiecień E., Kizerwetter-Świda M., Chrobak-Chmiel D., Rzewuska M. Tetracycline, Macrolide and Lincosamide Resistance in Streptococcus canis Strains from Companion Animals and Its Genetic Determinants. Antibiotics. 2022;11:1034. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11081034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agga G.E., Kasumba J., Loughrin J.H., Conte E.D. Anaerobic Digestion of Tetracycline Spiked Livestock Manure and Poultry Litter Increased the Abundances of Antibiotic and Heavy Metal Resistance Genes. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:614424. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.614424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amachawadi R.G., Scott H.M., Alvarado C.A., Mainini T.R., Vinasco J., Drouillard J.S., Nagaraja T.G. Occurrence of the Transferable Copper Resistance Gene tcrB among Fecal Enterococci of U.S. Feedlot Cattle Fed Copper-Supplemented Diets. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:4369–4375. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00503-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yazdankhah S., Rudi K., Bernhoft A. Zinc and copper in animal feed—Development of resistance and co-resistance to antimicrobial agents in bacteria of animal origin. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2014;25:25862. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v25.25862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodel-Christian S.L., Murray B.E. Characterization of the gentamicin resistance transposon Tn5281 from Enterococcus faecalis and comparison to staphylococcal transposons Tn4001 and Tn4031. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1147–1152. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.6.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska B., Kowalewski C., Krolak-Ulinska A., Marusza W. Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:8088. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas W.D., Jr., Archer G.L. Mobility of Gentamicin Resistance Genes from Staphylococci Isolated in the United States: Identification of Tn4031, a Gentamicin Resistance Transposon from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1335–1341. doi: 10.1128/AAC.33.8.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szakacs T.A., Kalan L., McConnell M.J., Eshaghi A., Shahinas D., McGeer A., Wright G.D., Low D.E., Patel S.N. Outbreak of Vancomycin-Susceptible Enterococcus faecium Containing the Wild-Type vanA Gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:1682–1686. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03563-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer K.L., Godfrey P., Griggs A., Kos V.N., Zucker J., Desjardins C., Cerqueira G., Gevers D., Walker S., Wortman J., et al. Comparative Genomics of Enterococci: Variation in Enterococcus faecalis, Clade Structure in E. faecium, and Defining Characteristics of E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus. mBio. 2012;3:e00318-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00318-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanderson H., Gray K.L., Manuele A., Maguire F., Khan A., Liu C., Rudrappa C.N., Nash J.H.E., Robertson J., Bessonov K., et al. Exploring the Mobilome and Resistome of Enterococcus faecium in a One Health Context across Two Continents. bioRxiv. 2022. preprint . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The draft whole genome sequence assemblies of the Enterococcus spp. recovered from One Health sectors (clinical, bovine cattle, dairy cattle, swine, environment, municipal waste water) are available in GenBank under Bio Projects PRJNA604849. Whole genome sequence assemblies of Enterococcus spp. from poultry are available in GenBank under Bio Project PRJNA273513.