Abstract

Background

Role modelling’s pivotal part in the nurturing of a physician’s professional identity remains poorly understood. To overcome these gaps, this review posits that as part of the mentoring spectrum, role modelling should be considered in tandem with mentoring, supervision, coaching, tutoring and advising. This provides a clinically relevant notion of role modelling whilst its effects upon a physician’s thinking, practice and conduct may be visualised using the Ring Theory of Personhood (RToP).

Methods

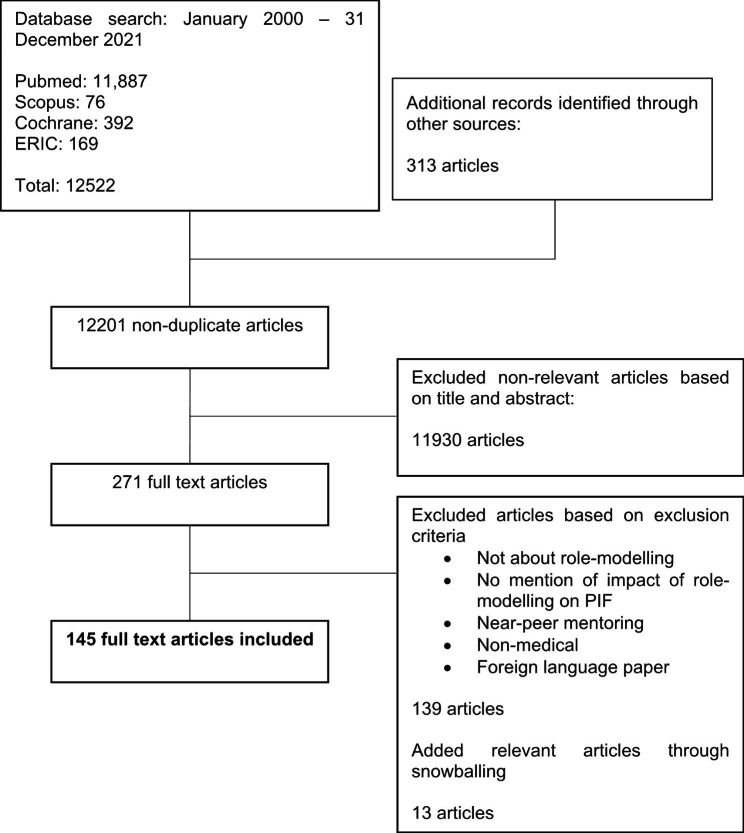

A Systematic Evidence Based Approach guided systematic scoping review was conducted on articles published between 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2021 in the PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, and ERIC databases. This review focused on the experiences of medical students and physicians in training (learners) given their similar exposure to training environments and practices.

Results

12,201 articles were identified, 271 articles were evaluated, and 145 articles were included. Concurrent independent thematic and content analysis revealed five domains: existing theories, definitions, indications, characteristics, and the impact of role modelling upon the four rings of the RToP. This highlights dissonance between the introduced and regnant beliefs and spotlights the influence of the learner’s narratives, cognitive base, clinical insight, contextual considerations and belief system on their ability to detect, address and adapt to role modelling experiences.

Conclusion

Role modelling’s ability to introduce and integrate beliefs, values and principles into a physician’s belief system underscores its effects upon professional identity formation. Yet, these effects depend on contextual, structural, cultural and organisational influences as well as tutor and learner characteristics and the nature of their learner-tutor relationship. The RToP allows appreciation of these variations on the efficacy of role modelling and may help direct personalised and longitudinal support for learners.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-023-04144-0.

Keywords: Role model, Mentoring, Mentoring umbrella, Professional identity formation, Ring Theory of Personhood

Introduction

Role modelling in medical education boosts cognitive skills [1], shapes moral values [2, 3], moulds professional practice [6–8], and instils professional, clinical, sociocultural expectations, standards of practice, professional codes of conduct, goals, roles and responsibilities [4, 5]. However, despite this burgeoning array of functions, it is role modelling’s ability to shape “what being a good doctor means and the manner in which he or she should behave” [4, 5] in “the foundational process one experiences during the transformation from lay person to physician” (professional identity formation or PIF) [5, 6] that has garnered the most attention.

However, till now, deeper evaluation of role modelling has been hampered by a lack of a clear definition [7], continued conflation with other practices, and focus upon the learner-tutor dyad, often to the exclusion of wider contextual considerations, learner and tutors related factors [8]. There has also been a failure to consider role modelling’s unintended, long-lasting negative and positive effects [7].

Krishna, Toh [8] and Radha Krishna, Renganathan [9]’s concepts of the mentoring umbrella offers a unique opportunity to study role modelling in a new light. The mentoring umbrella posits that role modelling is part of a spectrum of intertwined approaches including mentoring, supervision, coaching, tutoring and advising [10, 11]. As is increasingly reported, role modelling in the mentoring umbrella is often applied in tandem with one or more of these approaches. This perspective allows accounts of role modelling to be studied in tandem, negating the need to unpick one from the other for closer scrutiny. In light of this, a review into what is known of role modelling is proposed to better employ, structure, support and oversee its use in medical training.

Theoretical framework

Role modelling’s ability to shape professional identity, thinking, feeling, attitudes and practice is best described by a constructivist ontological and relativist epistemological position. This lens also best captures its part in the guided immersion of medical students, the experiential learning of physicians in training, and the wider clinical, professional, environmental and sociocultural influences upon role modelling.

This theoretical lens also allows use of Radha Krishna and Alsuwaigh [12]’s concept of the Ring Theory of Personhood (RToP) to capture the wider effects of the mentoring umbrella [13] on professional, personal and research development and professional identity formation (PIF) [15–19]. Appreciation of these particularised effects upon the various aspects of a medical student or physician in training (henceforth learner) will allow better appreciation of the mechanism behind role modelling.

The theoretical lens: the ring theory of personhood

Previous reviews [14, 15, 16, 17, 18] have revealed and mapped the inevitable tensions or ‘conflicts’ between the rings of the RToP in the face of moral distress and identity formation, and their impact upon self-concepts of personhood and identity. It is posited that the RToP will forward a better understanding of how role modelling inculcates new professional values, beliefs, and principles and shapes a learner’s professional identity.

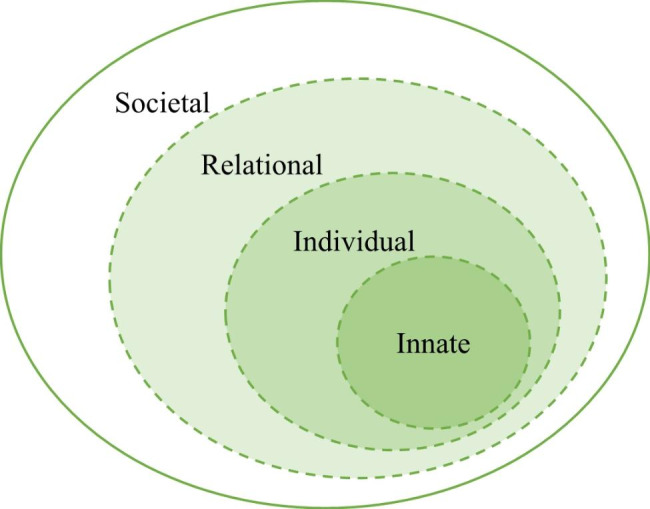

The RToP suggests that personhood is composed of the Innate, Individual, Relational and Societal domains (Fig. 1). Each ring possesses a belief system containing the patient’s values, beliefs and principles. The Innate Identity considers religious, gender, cultural, community-based beliefs, moral values and ethical principles [19–23]. The Individual Identity encompasses personal values, beliefs, and personalities [24–27] whilst the Relational and Societal Identities pivot on familial and societal values, beliefs, expectations, and principles, respectively [24–27]. The integration of new experiences, insights, norms, codes of practice and ideals into current values, beliefs and principles that underpin a learner’s identity is likely to cause ‘conflict’ within the rings (disharmony) and between the rings (dyssynchrony) [28]. Understanding the tensions will enhance appreciation of the mechanism by which role modelling integrates and attends to ‘conflicts’ within and between the rings.

Fig. 1.

The Ring Theory of Personhood

Methodology

A Systematic Evidence Based Approach guided systematic scoping review (henceforth SSR in SEBA) [29–42] is used to study the effects of role modelling amongst medical students and physicians in training where increasing use of experiential learning and clinical integrated programs see them exposed to similar role modelling, training cultures, practices and environment, and hidden curricula. We recognise that role modelling will differ amongst specialists, consultants and attendings who are not involved in formal training programs and thus exclude them from this study.

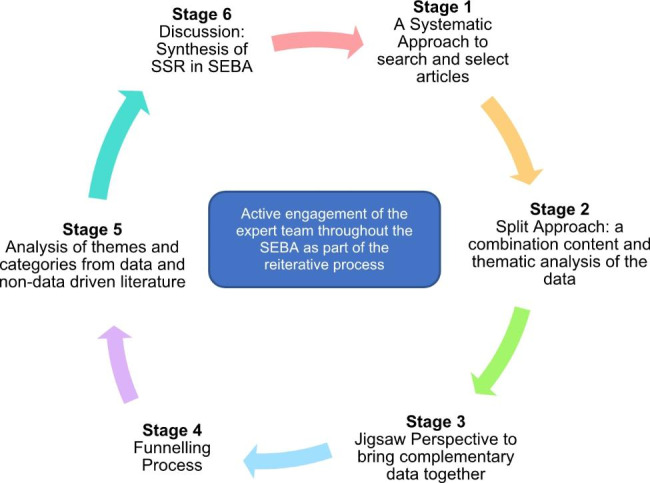

This SSR in SEBA is overseen by an expert team comprising medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), and local educational experts and clinicians at NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School who guide, oversee and support all stages of SEBA to enhance reproducibility and accountability of the study process (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The SEBA Process

Stage 1 of SEBA: systematic approach

The research and expert teams set the overarching goals, study population, context and remediation programs to be evaluated and were guided by the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study Design (PICOS) elements of the inclusion criteria [43, 44] Table 1.

Table 1.

PICOs, Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria Applied to Database Search

| PICOS | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

• Medical students, junior doctors and residents in all specialities and subspecialities of psychiatry, medicine, surgery, paediatrics, family medicine and obstetrics and gynaecology • In formal training programs or structured and assessed longitudinal programs, including residency and advanced training programs, specialist training, surgical training, and other speciality and subspeciality training programs. |

• Allied health specialties such as dietetics, nursing, psychology, chiropractic, midwifery, social work • Non-medical specialties such as clinical and translational science, veterinary, dentistry • Not in training programs such as attendings, consultants and or physicians who have exited structured training programs. |

| Intervention |

• Role modelling • Supervision • Coaching • Teaching • Tutoring • Novice mentoring involving junior physicians, residents and/or medical students mentored by senior clinicians aimed at advancing the professional and/or personal development of the mentee o Mentoring processes o Mentor factors o Mentee factors o Mentoring relationship o Host organization o Outcomes of mentoring o Barriers to mentoring o Mentoring structure o Mentoring framework o Mentoring culture o Mentoring environment |

• Peer mentoring, Near-peer mentoring, mentoring for leadership, mentoring patients or mentoring by patients, interdisciplinary mentoring |

| Comparison | • Comparisons accounts of mentoring between mentoring programs, editorials and perspective, reflective, narratives and opinions pieces | |

| Outcome |

• Personal outcomes of mentoring such as values, beliefs, identity as a medical professional etc. • Professional development outcomes such as on career choices (including academia positions/careers) |

• Papers that did not discuss impact of role modelling on personal or professional development outcomes |

| Study design |

• All study designs are included o Descriptive papers o Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed study methods o Systematic review, literature reviews, and narrative reviews • Perspectives, opinion, commentary pieces, and editorials • Year: 1st Jan 2000–31st December 2021 |

Given that this review sees role modelling as part of the mentoring umbrella and intimately entwined with practices such as mentoring, supervision, coaching, tutoring, and teaching, these terms were included in the general search. However, given resource limitations and data from our recent reviews of the various constituents of the mentoring umbrella separate searches of each of these practices were not conducted. Focus was upon role modelling and any accounts of its combined use with other aspects of the mentoring umbrella.

Independent searches were carried out between 18th October 2021 and 17th January 2022. The searches involved PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, ERIC and grey literature databases (GreyLit, OpenGrey, and Web of Science). Additional ‘snowballing’ of references of the included articles ensured a more comprehensive review of the articles [45] This search was carried out between 17th January 2022 and 24th April 2022.

Using an abstract screening tool, the research team independently reviewed abstracts to be included and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included [46].

Stage 2 of SEBA: split approach

The Split Approach [17, 47] sees concurrent thematic and directed content analysis of the included full-text articles by three independent teams. The first team summarised and tabulated the included full-text articles (Appendix A).

Thematic analysis and directed content analysis

Using Braun and Clarke [48]’s approach to thematic analysis, the second team ‘actively’ read the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data and achieved consensus on the final list of themes. [49–53].

Using Hsieh and Shannon [54]’s approach to directed content analysis, the third team identified categories from Cruess and Cruess [55]’s article, “The Development of Professional Identity” and achieved consensus on the final list of categories.

The final codes were compared and discussed with the final author who checked the primary data sources to ensure that the codes made sense and were consistently employed. Any differences in coding were resolved.

‘Negotiated consensual validation’ was used as a means of peer debrief in all three teams to further enhance the validity of the findings [56].

Stage 3 of SEBA: jigsaw perspective

The Jigsaw Perspective employs Phases 4 to 6 of France et al. France, Wells [57]’s adaptation of Noblit et al. Noblit and Hare [58]’s seven phases of meta- ethnographic approach to view the themes and categories as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle where overlapping/complementary pieces are combined to create a bigger piece of the puzzle referred to as themes/categories. This process would see themes and subthemes compared with the categories and subcategories identified. These similarities were verified by comparing the codes contained within them. If they are complementary in nature, the subtheme and subcategory are combined to create a bigger piece of the jigsaw puzzle.

Stage 4 of SEBA: funnelling

Themes/categories were compared with the tabulated summaries [57, 58]. These funnelled domains created from this process formed the basis of the discussion’s ‘line of argument’.

Results

A total of 145 articles were included (Fig. 3). Sixty eight articles explored role modelling in the undergraduate context, 36 were in the postgraduate context, and 41 explored role modelling in both undergraduate and postgraduate settings.

Fig. 3.

PRISMA Flowchart

The themes identified were theories, indications, characteristics, impact and influences on the role modelling process. The categories identified were theories, characteristics, indications, influences and impact of role modelling.

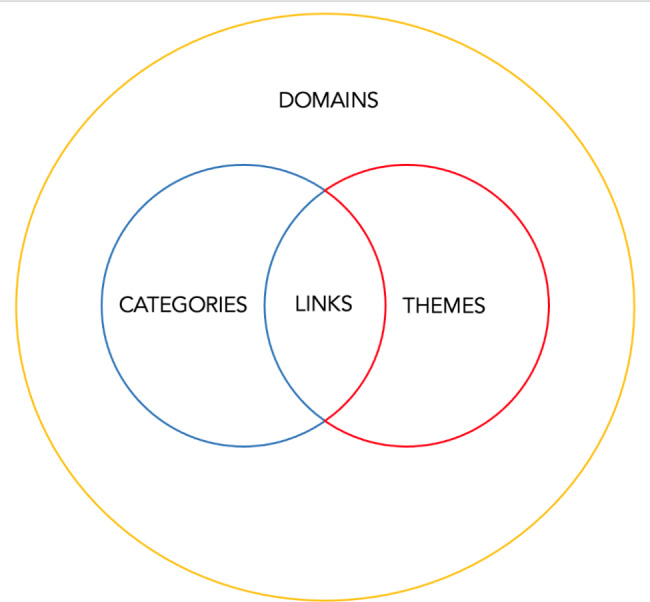

The funnelled domains (Fig. 4) created from the combination of the themes and categories were (1) existing theories, (2) definitions, (3) indications, (4) characteristics of role models, (5) the impact of role modelling.

Fig. 4.

Domains, Categories, Themes

Domain 1. existing theories

Most current theories are built on the notion that role modelling hinges on active observation of the role model’s personal, clinical, and/or social circumstances, practice, attitudes, decisions and skills; reflection on these observations; translation of these insights into principles and actions; and integration of these insights into practice, thinking, attitudes, skills, deliberations and conduct [59–76]. Many of these theories focus on learner attitudes, belief system, narratives, clinical experiences, contextual considerations and positive outcomes of role modelling [1, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 77–118]. There is little consideration for the wider sociocultural, programmatic and practical factors impacting role modelling.

Domain 2. definitions

Krishna et al. [7]’s review describe role modelling as “a process which may be formal or informal [1, 59, 63–70, 80, 81, 84–90, 92, 94, 97, 100–105, 108, 116, 119–146], immediate or delayed (requiring post-reflection) [59, 60, 65, 67, 69, 81, 86, 88, 89, 94, 98, 101, 106–108, 110, 114, 121, 142, 146–149], involving seniors, peers, or others within the profession as a role model [1–3, 59, 61, 62, 65, 67, 68, 70–72, 74, 76, 89, 91, 94, 97, 100, 102–106, 108, 109, 113, 114, 116, 118, 132, 134, 135, 137, 138, 141–146, 148–168], advertent or inadvertent by both the role model or the learner [1, 59, 60, 64, 66, 68–70, 92, 102, 103, 106–108, 110, 112–114, 116, 122, 134, 141, 142, 147, 150], and clinical or non-clinical [1–3, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 70–76, 82, 83, 85, 89–91, 97, 99, 100, 102–106, 108, 109, 111–114, 116, 118, 120, 126, 131, 137, 141–146, 148–150, 152, 154, 159–174], in which positive or negative behaviours, actions or attitudes [1–3, 59–64, 66, 67, 69–72, 74, 77–118, 141–146, 148, 149, 159–168] are emulated or rejected by the learner” [1, 60, 61, 67, 69–71, 91, 100, 106–108, 110–112, 114, 115, 117, 141, 142, 150, 162, 167, 175].

Domain 3. indications

Passi et al. [111]’s BEME Guide on role modelling, describes three key indications for role modelling.- transmitting professional behaviours [59–62, 65, 66, 68, 76, 77, 82, 100–103, 106, 108, 111, 114, 115, 121, 130, 135, 140, 143, 146, 148, 152, 161, 168], influencing the development of professional attributes of learners [1, 2, 59, 63, 64, 68–70, 72, 73, 75–77, 79, 81, 95–98, 100, 102, 103, 105, 108, 110–113, 115, 117, 119–122, 125, 126, 128, 132, 134, 135, 141, 144, 147, 148, 150, 152–154, 156, 161, 171, 172, 176–178] and influencing career aspirations of learners [59, 60, 70, 71, 73, 75–78, 80, 86, 88–90, 95, 98, 99, 102, 109, 111–113, 118, 126, 134, 135, 137, 138, 140, 143, 153, 155, 157, 158, 160, 162, 166, 169, 170, 174, 177, 179–185]. However, despite suggestions of a role in PIF, this has not been captured here.

Domain 4. characteristics of role models

Effective role modelling depends on characteristics of the role models. Factors that draw learners to a role model include their personal characteristics, relatability, ability to build relationships with the learner, and their clinical and teaching competencies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of role models

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

| Clinical competencies | |

|

• Clinical knowledge and skills (107, 112, 118) • ‘diagnostic and clinical skills’ (111) • ‘comprehensive approach to management, treatment and investigations’ (111) |

• Insufficient medical knowledge (118) • Insensitive to the needs of patients (102) • Inadequate relations with patients (118) • Uncooperative interaction with health care workers (102, 118) • Focused on tutor-centred patient interactions in order to save time (102) • Inappropriate medical reasoning (118) |

| Teaching skills | |

|

• Concern for student well-being (75) • Inspirational (174) • Student-focused (174) • Knowledgeable (174) • Patience (174) • Aware and prepared for their roles as role models (59, 63–66, 73, 81, 85, 88–91, 93, 95, 96, 98, 99, 101, 103, 107, 110, 117, 119, 126, 130, 132, 134, 135, 137, 153, 154, 176, 177, 186, 187) • Keeping the teaching simple, clear, informative, well-organised, and well-illustrated (172) • Demonstrating professionalism in daily work, • Explicitly explaining to learners the rationale behind actions, • Guiding the reflective process of learners, and providing timely • And meaningful formative feedback (86, 88, 96, 98, 110, 119) |

• Rarely give feedback (116) • Humiliation of students (102) • Demoralising to learners (109) |

| Personal characteristics | |

|

• Effective interpersonal skills (107, 112, 150) • Positive outlook (112) • Leadership (112) • Dedication (112) • Commitment to excellence (107, 112) • Altruism (150) • Politeness (112) • Inspiring (112) • Enthusiasm (112) • Ethical and moral practice (77) • Care and compassion (77) • Punctuality, professionalism (77) • Commitment to job (77) • Honest communication (77) • Good listening (77) • Discipline (77) • Rule-following (77) • Charismatic individual (1, 60, 150) • Humanistic and collaborative relations with patients and colleagues (118) • External manifestations of professional (118) • Cooperation rather than competitiveness (109) • Gender or sexual identity (71, 72, 75, 159), race (72, 75), and personality (111) • Learners emulate role models that they feel are closer to their own present identity (71, 72, 74, 75, 111, 159) |

• Poor interpersonal relations (1) • Lack of self-confidence (118) • Absence of leadership (118) • May be rude to patients, students or staff, and may exhibit condescending behaviour (77) • Lack of integrity (1) • Lack professionalism (77) • Inadequate external appearance (118) |

| Institutional factors | |

|

• Promotes balanced working practices, • Incentivises tutors, • Provides them with ‘protected time’ to teach and role model (84, 94, 107, 121, 127, 134, 136, 153, 157) • Time for reflection (59, 60, 65, 67, 69, 81, 86, 88, 89, 94, 98, 101, 106, 107, 110, 114, 121, 146, 147) • Aligned implicit curriculum, or “hidden” or “informal” curriculum, with the explicit, or “formal” curriculum boosts positive role modelling(108), • Consistent approach (175) • Making behaviours more intentional (86, 88, 96, 98, 110, 119) |

• Time pressures • Lack of protected time, • External stress, • Bureaucracy, • Conflicts between explicit and implicit curriculums (63, 79, 86, 88, 96, 98, 108, 110, 119, 123, 154, 175, 188) |

Domain 5. impact of role modelling through the lens of the RToP

Role modelling has an array of effects upon the learner. These effects are summarised in Table 3 for ease of review. Perhaps more significantly, the impact of these effects vary from learner to learner. The RToP explains that these differences are a result of ‘resonance’ between regnant belief systems and the practices, guidance, expectations, roles, responsibilities and standards being introduced [67, 100, 155] or ‘conflict’ which take the form of disharmony [84, 99–101] and/or dyssynchrony [84].

Table 3.

The Impact of Role modelling

| Innate | • Reassurance of success regardless of gender or gender identity (71, 159, 160, 181) • Tolerance (60, 69, 74, 80, 165) • Humanistic attitude (67, 87, 98, 100, 111, 116–118, 122, 126, 137, 141, 147, 152, 154, 169, 171, 189) |

|---|---|

| Individual |

• Personal care and wellness (68, 75, 76, 100, 108, 128, 163, 178, 190) • Influences career choice (59, 60, 70, 71, 73, 75–78, 80, 86, 88–90, 95, 98, 99, 102, 109, 111–113, 118, 126, 134, 135, 137, 138, 140, 143, 153, 155, 157, 158, 160, 162, 166, 169, 170, 174, 177, 179–185) • Ability to build rapport and communicate with patients (68, 80, 85, 90–92, 96, 98, 101, 113, 117, 120, 126, 141, 145, 147, 152, 154, 178) • Communication with peers and colleagues (1, 68, 92, 102, 105, 109, 112, 118, 119, 126, 141, 144, 149, 150, 162, 165, 191, 192) • Communicating with juniors and students (68, 73, 97, 102, 112, 118, 120, 122, 126, 152, 162–165) • Career success (97, 160, 173) • Knowledge (66, 77, 82, 83, 85, 94, 96, 102, 113, 116, 120, 122, 137, 141, 154–156, 165, 169, 173, 174, 191, 193) • Teaching skills (73, 75–77, 80, 82, 85, 88–91, 96, 97, 100, 102, 104, 112, 122, 126, 131, 137, 151, 152, 154, 156, 157, 165, 170, 172, 174, 192–194) • Career satisfaction (71, 73, 76, 154, 155, 177) • Motivating and inspiring, positivity (66, 71, 73, 76, 80, 89, 90, 97, 102, 109, 111, 113, 116, 128, 153–155, 157, 165, 171, 189, 195) • Readiness to express feelings (1, 84, 116) • Humility (80, 91, 102, 108, 120, 137, 147, 150, 154, 171, 189) • Empathy (61, 67, 68, 77, 80, 85, 89, 91, 92, 96, 102, 108, 111, 113, 117, 122, 128, 130, 131, 144, 150, 154, 161, 176, 189, 190, 192) • Honesty/Integrity (1, 66, 68, 73, 80, 85, 90, 92, 97, 102, 103, 108, 113, 119, 128, 131, 137, 144, 147, 152–154, 157, 161, 162, 165, 170, 178, 189, 190, 193) • Respectfulness (68, 73, 77, 80, 82, 85, 92, 102, 108, 111–113, 117, 122, 128, 131, 142, 149, 151, 152, 154, 161, 162, 165, 178, 190, 192, 193) • Compassion (66, 67, 73, 76, 77, 80, 84, 85, 90–92, 97, 102, 108, 111, 113, 117, 122, 128, 131, 142, 144, 149, 152, 154, 161–163, 171, 174, 178, 189, 190, 192, 193) • Curiosity (92, 108, 178, 189) • Contending with Cynicism (60, 76, 92, 112, 115, 116, 125, 142, 144, 154, 164) • Dedication (66, 80, 102, 113, 137, 142, 161, 170, 189) • Self-improvement (68, 73, 85, 113, 152–154, 161) • Leadership (70, 71, 73, 80, 89–91, 102, 113, 118, 131, 153, 154, 157, 163, 189) • Commitment to excellence (73, 102, 108, 113, 153, 154, 157, 189) • Patience/calmness (85, 112, 122, 147, 154, 174, 192) • Altruism (111, 128, 154, 171, 190) • Responsibility (80, 119, 154, 190) • Resilience (128, 140, 154, 189) • Self-confidence (154) |

| Relational |

• Relationship with family (71, 73, 128) • Able to balance work with familial duties and obligations (71, 73, 75) |

| Societal |

• Maintaining a hierarchy in the profession (96, 109, 112, 116, 150, 165) • Treatment of juniors (66, 102, 104, 113, 130, 149, 150, 165, 172, 190) • Support of students (116, 163, 165) • Contribution to research (85, 89, 90, 118, 154, 162, 170, 173, 191) • Relationship with patients (61, 66, 76, 77, 80, 88, 96, 97, 100, 102, 111, 113, 116–118, 130, 137, 141, 142, 144, 145, 150, 153, 154, 162, 164, 165, 176) • Commitment to teach (66, 68, 80, 97, 102, 104, 116, 120, 122, 154, 157, 162, 163, 165, 192, 195) • Attitude towards collaboration, competition, cooperation, and collegiality (63, 64, 68, 85, 98, 108, 116, 141, 154, 169, 192) • Relationship with colleagues including allied health (1, 76, 77, 89, 90, 96, 97, 102, 105, 109, 111, 112, 118, 141, 144, 149, 150, 154, 162, 165, 192) • Relationship with students/juniors (66, 73, 82, 83, 88–91, 96, 111, 120, 122, 151, 153, 154, 157, 170) • Clinical competency (61, 64, 66, 67, 73, 75, 76, 82, 83, 85, 89, 90, 97, 99, 100, 102, 111–113, 116, 118, 120, 126, 131, 137, 141, 149, 150, 152, 154, 163, 167, 169–174) • Motivation to develop professionalism (1, 113, 116, 162) • Maintaining of patient confidentiality (68, 145) • Avoiding use of derogatory humour (112, 115, 125, 153, 196, 197) • Patient-centred care (67, 68, 75, 100, 137, 154, 171) • Not discriminating against certain patient profiles (139, 196, 197) • Proper disclosure of medical information or errors (66, 68, 92, 93) • Organisation, management, efficiency (64, 80, 87, 118, 128, 154, 170) |

Stage 5 of SEBA: analysis of evidence and non-evidence driven literature

To address concerns about data from grey literature, which was neither quality-assessed nor necessarily evidence-based, the study team thematically analysed data from grey literature and non-evidence-based pieces such as letters, opinion and perspective pieces, commentaries and editorials drawn from the bibliographic databases separately and compared these themes against themes drawn from peer-reviewed, evidence-based data. Similar themes were reveal suggesting that non-evidence-based articles did not bias the analysis.

Discussion

In answering its research question, this SSR in SEBA on role modelling amongst medical students and physicians in training reveals a wider concept of role modelling than previously theorised. Rather than hinging almost exclusively on the learner’s active observation, cognitive base, clinical insight, reflective practice and ability to integrate their new insights and reflections, this SSR in SEBA reveals tutor-dependent and context-specific considerations.

Learner-centric considerations

The data suggests that there is more to learner-centric considerations than previously proposed. These include the learner’s narrative which informs the learner’s ‘internal decision-making processes’. These ‘internal decision-making processes’ include the ability to detect a learning moment (sensitivity); determine if what they are observing is of interest or relevance, a positive or negative experience or observation and if they should ponder on these experiences (judgement); whether they have the ability, time, competency, and motivation to integrate the lessons learnt into practice and address any dissonance that may arise (willingness); and whether they can and are able to balance other considerations at hand as these lessons are integrated (balance).

These ‘internal decision-making processes’ are influenced by several other factors. Like the learner’s narrative and belief systems, their clinical insights and cognitive base influence their attention, motivations, sensitivity, judgement, willingness, reflections, balance, and beliefs. The learner’s contextual considerations include their interpretation of regnant practice, social, cultural, familial, relational, existential and clinical factors, together with their belief systems which contain their personal values, beliefs and principles. These help to fashion their personal moral and ethical compass and their attitudes towards practices, conduct, skills and/or attitudes being role-modelled. This combination helps to mould their efforts as they attend to resonances, disharmony and/or dyssynchrony with their prevailing identity. Having the learner primed to receiving and valuing lessons learnt through purposeful role modelling also underlines the role of tutor-dependent and contextual factors.

Tutor dependent factors

Tutor dependent factors include the tutor’s training, role modelling, feedback and support skills; their motivations, accessibility, experience, availability, ability; and their willingness to provide personalised, appropriate, timely and longitudinal support and feedback helps to configure the role-modelling process. At the heart of these considerations is the ability of the tutor to attract attention and change thinking. This is helped in part by the tutor’s position of influence, seniority, respect and ability to inspire the learner.

Tutor-dependent facets of role modelling also reveal setting-specific and tutor-learner relationship-contingent elements. Perhaps exemplifying this is the nature, significance, and depth of the pre-existing tutor-learner relationship and the presence of trust.

Overall tutor-dependent features reiterate the importance of tutor training, longitudinal tutor support, and the importance of preparing learners for their role modelling experiences.

Contextual considerations

Contextual considerations pivot on structured and personalised aspects. A personalised approach ensures that the physician’s cognitive base, narratives, belief system, emotional state, clinical insights, and internal decision making processes are well-accomodated. It also ensures that mentored guidance in the observation, reflection, feedback and integration phases of role modelling is provided. This personalised aspect facilitates individualised guidance to help learners resolve conflicts between their current position and the values, beliefs and principles drawn from the role model. It also considers the learner’s social, cultural, familial, relational, existential, psycho-emotional state; and regnant environmental, sociocultural, professional, academic, clinical, research and curricular factors.

The structured aspect includes a consistent approach framed by the presence of clearly stipulated goals, clear expectations, standards of practice, codes of conduct, timelines, the presence of protected time for reflection and training, roles and responsibilities, and a training framework which includes ‘protected time’ for learning, reflection, debriefing, feedback and personalised and timely support. The structured aspect also considers the tutor’s accessibility, availability and motivations as well as their contextual and motivations. Overall, the structured approach introduces the importance of the formal program, the role of the host organisation and the structure of the program.

Cruess and colleagues (55, 65, 107, 198) underscore the significance of contextual considerations in role modelling by highlighting the socialisation process. The authors report that planned and structured role modelling carried out by trained tutors and overseen by a formal training program within a nurturing learning environment promotes integration of new values, practices, principles, beliefs, conduct and competencies [55, 65, 107, 198]. Perhaps less apparent but nonetheless critical is the role of the host organisation in ensuring effective balance between the personalisation and consistency (flexibility) of the role modelling process. In addition, the host organisation plays a pivotal role in ensuring oversight of support, feedback and remediation.

Role modelling and professional identity formation

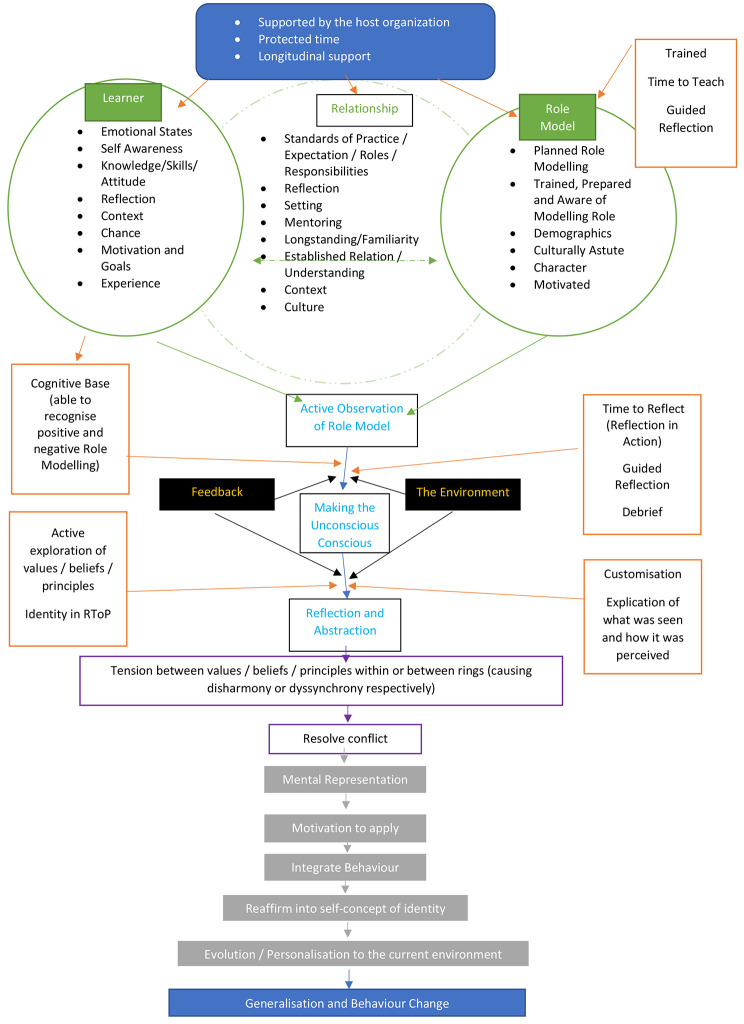

Acknowledging that role modelling introduces new practices, skills, knowledge, attitudes and competencies that will guide how a learner will feel, think and act as a physician, role modelling clearly has a key role in nurturing the professional identity of learners. To achieve this, role modelling shapes their belief system which in turn influences how they see themselves. Built upon data accrued in this study, the mechanism behind role modelling is summarised in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Mechanism of Role Modelling

To attend to the effects of ‘disharmony’ and or ‘dyssynchrony’, adaptations are made to one’s belief system and professional identity. Learners must once again be motivated, willing and capable of balancing the wider considerations to achieve a viable professional identity. These changes in values, beliefs and principles and subsequent self-concepts of personal identities highlight the links between personal identity and PIF. This process also sees the learner’s interpretations and personalisation of what has been role modelled and how they have been employed.

Limitations

There are several areas that limited this study. As the included articles comprised of reviews and primary studies, there were overlaps in the primary studies addressed in the reviews and those identified independently by the study team. Although the overlaps were considered in the analysis, no structured approach was undertaken.

Whilst there is a relative dearth of data on role modelling, perceiving role modelling as part of the mentoring umbrella has allowed it to be studied more widely together with similar practices. This allows a practical and modern perspective of current practices surrounding role modelling.

To ensure that this search approach is reproducible the SEBA approach was adopted. Whilst well evidenced in medical education and palliative care research, the need for three independent teams has restricted the focus of this study to medical students and physicians in training. Yet such a move may be justified by the fact that it builds on earlier studies on the mentoring umbrella, prevents conflation of data across different groups of healthcare professionals with distinct training practices and recognises the need to recognise the contextual influences of role modelling.

Focus upon reports published in English may have also restricted the search results. Similarly, focus upon role modelling published in the English language saw most of the data drawn from North America and the European countries that may not necessarily be transferable beyond these regions. However, given that practices in much of Asia are influenced by Western style education practices, it is entirely likely that the lessons learnt will be transferable albeit with some context specific adaptations to take into account local healthcare and education systems and sociocultural considerations.

Conclusion

Role-modelling impacts PIF and influences personal identity, yet its true impact still needs further elucidation in order for it to be effectively guided and assessed. Missing also is evidence of the balancing process and adjustments to the belief system. Whilst it might be notions of identity patching and identity splinting such as those submitted by Pratt et al. [199] at play, it is clear that further study is required. The longitudinal impact of role modelling should also be evaluated through guided reflections on planned role modelling and through use of portfolios that span the training program.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna and A/Prof Cynthia Goh whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this review. The authors would also like to thank Annelissa Mien Chew Chin for her assistance.

Abbreviations

- PIF

Professional Identity Formation

- SSR

Systematic Scoping Review

- SEBA

Systematic Evidence Based Approach

- PICOS

Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome

Author Contribution

EYHK, KKK, YR and LK were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA.

Consent for publication

NA.

Conflict of interest and source of funding

EYHK, KKK, YR and LK have no competing interests and no funding was received for this review.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Armyanti I, Mustika R, Soemantri D. Dealing with negative role modelling in shaping professional physician: an exploratory study. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2020;70(9):1527–32. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.29558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnhoorn PC, Houtlosser M, Ottenhoff-de Jonge MW, Essers G, Numans ME, Kramer AWM. A practical framework for remediating unprofessional behavior and for developing professionalism competencies and a professional identity. Med Teach. 2019;41(3):303–8. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1464133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mak-van der Vossen M, Teherani A, van Mook W, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA. How to identify, address and report students’ unprofessional behaviour in medical school. Med Teach. 2020;42(4):372–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1692130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsui T, Sato M, Kato Y, Nishigori H. Professional identity formation of female doctors in Japan – gap between the married and unmarried. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1479-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarraf-Yazdi S, Teo YN, How AEH, Teo YH, Goh S, Kow CS, et al. A scoping review of professional identity formation in Undergraduate Medical Education. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3511–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07024-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J. Professional identity formation in medical education: the convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24(4):245–55. doi: 10.1007/s10730-012-9197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radha Krishna LK, Renganathan Y, Tay KT, Tan BJX, Chong JY, Ching AH, et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine – a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):439. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishna L, Toh YP, Mason S, Kanesvaran R. Mentoring stages: a study of undergraduate mentoring in palliative medicine in Singapore. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0214643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radha Krishna L, Renganathan Y, Tay K, Tan B, Chong J, Ching A, et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine - a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):439. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toh R, Koh K, Lua J, Wong R, Quah E, Panda A, et al. The role of mentoring, supervision, coaching, teaching and instruction on professional identity formation: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:531. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03589-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ong Y, Quek C, Pisupati A, Loh E, Venktaramana V, Chiam M, et al. Mentoring future mentors in undergraduate medical education. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0273358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radha Krishna LK, Alsuwaigh R. Understanding the Fluid Nature of Personhood – the Ring Theory of Personhood. Bioethics. 2015;29(3):171–81. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teo K, Teo M, Pisupati A, Ong R, Goh C, Seah C, et al. Assessing professional identity formation (PIF) amongst medical students in Oncology and Palliative Medicine postings: a SEBA guided scoping review. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21:200. doi: 10.1186/s12904-022-01090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, Chia JL, Chan NPX, Abdurrahman ABHM et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician’s personhood: a systematic scoping review. 2020;15(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Ho CY, Kow CS, Chia CHJ, Low JY, Lai YHM, Lauw SK, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):516. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, Kuek JTY, Chia JL, Chan NPX et al. Impact of Caring for Terminally Ill Children on Physicians: A Systematic Scoping Review.American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2020:1049909120950301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Chan N, Chia J, Ho C et al. Extending the Ring Theory of Personhood to the Care of Dying Patients in Intensive Care Units. Asian Bioethics Review. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Huang H, Toh RQE, Chiang CLL, Thenpandiyan AA, Vig PS, Lee RWL et al. Impact of Dying Neonates on Doctors’ and Nurses’ Personhood: A Systematic Scoping Review.J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wei SS, Krishna LKR. Respecting the wishes of incapacitated patients at the end of life. Ethics & Medicine: An International Journal of Bioethics. 2016;32:15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Huang Y, Radha Krishna L, Puvanendran R. Role of the nasogastric tube and Lingzhi (Ganoderma lucidum) in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(4):794–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishna L, Lee R, Sim D, Tay K, Menon S, Kanesvaran R. Perceptions of Quality-of-life Advocates in a Southeast Asian Society. Diversity & Equality in Health and Care. 2017;14.

- 22.Loh AZ, Tan JS, Jinxuan T, Lyn TY, Krishna LK, Goh CR. Place of care at end of life: what factors are Associated with Patients’ and their family members’ preferences? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(7):669–77. doi: 10.1177/1049909115583045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quah E, Chua K, Lua J, Wan D, Chong C, Lim Y, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder perspectives of dignity and assisted dying. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;S0885–3924(22):00924–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishna LKR, Watkinson DS, Beng NL. Limits to relational autonomy—the singaporean experience. Nurs Ethics. 2014;22(3):331–40. doi: 10.1177/0969733014533239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishna LKR, Ho S. Reapplying the ‘Argument of Preferable Alternative’ Within the Context of Physician-Assisted Suicide and Palliative Sedation.Asian Bioethics Review. 2015;7(1).

- 26.Krishna LKR, Menon S, Kanesvaran R. Applying the welfare model to at-own-risk discharges. Nurs Ethics. 2015;24(5):525–37. doi: 10.1177/0969733015617340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishna LK. Addressing the concerns surrounding continuous deep sedation in Singapore and Southeast Asia: a Palliative Care Approach. J Bioeth Inq. 2015;12(3):461–75. doi: 10.1007/s11673-015-9651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Lim YX, Goh CK, Lim J, Wan DWJ, et al. A systematic scoping review on patients’ perceptions of dignity. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12904-022-01004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Kamal NHBA, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, Ong ZH, Ghazali HZB, Tan LHE, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):372. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, Tay KT, Hee JM, Chiam M, et al. Enhancing mentoring in Palliative Care: an evidence based Mentoring Framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649. doi: 10.1177/2382120520957649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamal NHA, Tan LHE, Wong RSM, Ong RRS, Seow REW, Loh EKY et al. Enhancing education in Palliative Medicine: the role of Systematic Scoping Reviews. Palliative Medicine & Care: Open Access. 2020;7(1):1–11.

- 33.Ong RRS, Seow REW, Wong RSM, Loh EKY, Kamal NHA, Mah ZH et al. A Systematic Scoping Review of Narrative Reviews in Palliative Medicine Education. Palliative Medicine & Care: Open Access. 2020;7(1):1–22.

- 34.Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW, Loh EKY, Kamal NHA, Ong RRS et al. A Systematic Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews in Palliative Medicine Education. Palliative Medicine & Care: Open Access. 2020;7(1):1–12.

- 35.Ngiam LXL, Ong YA-O, Ng JX, Kuek JTY, Chia JL, Chan NPX et al. Impact of Caring for Terminally Ill Children on Physicians: A Systematic Scoping Review. (1938–2715 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, Ong ZH, Ghazali HZB, Tan LHE, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho CY, Kow CS, Chia CHJ, Low JY, Lai YHM, Lauw S-K, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong DZ, Lim AJS, Tan R, Ong YT, Pisupati A, Chong EJX, et al. A systematic scoping review on portfolios of medical educators. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211000356. doi: 10.1177/23821205211000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, Chia JL, Chan NPX, Abdurrahman ABHM, et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician’s personhood: a systematic scoping review. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2020;15(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13010-020-00096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tay KT, Ng S, Hee JM, Chia EWY, Vythilingam D, Ong YT, et al. Assessing professionalism in Medicine–A scoping review of Assessment Tools from 1990 to 2018. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520955159. doi: 10.1177/2382120520955159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tay KT, Tan XH, Tan LHE, Vythilingam D, Chin AMC, Loh V et al. A systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of interprofessional mentoring in medicine from 2000 to 2019.Journal of interprofessional care. 2020:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Zhou YC, Tan SR, Tan CGH, Ng MSP, Lim KH, Tan LHE, et al. A systematic scoping review of approaches to teaching and assessing empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews2015 April 29, 2019. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v1.pdf.

- 45.Pham MA-O, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. (1759–2887(Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. springer publishing company; 2006.

- 47.Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, Tay KA-O, Tan XH, Ong YT et al. Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. (1932–6203 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development: sage; 1998.

- 50.Sawatsky AP, Parekh N, Muula AS, Mbata I, Bui TJMe. Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. 2016;50(6):657–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Voloch K-A, Judd N, Sakamoto KJHmj. An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho’ola Post-Baccalaureate students at the University of Hawai’i John A. Burns School of Medicine. 2007;66(4):102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, Martial C, Charland-Verville V, Lallier F, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0193001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H. Ponzer SJMt. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. 2010;32(2):148 – 53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cruess SR, Cruess RL. The Development of Professional Identity2018 05 October 2018.

- 56.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Reviews. 2016;5(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1203–10. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McKenzie S, Burgess A, Mellis C. A taste of Real Medicine”: Third Year Medical students’ report experiences of early workplace encounters. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:717–25. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S230946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sawatsky AP, Santivasi WL, Nordhues HC, Vaa BE, Ratelle JT, Beckman TJ, et al. Autonomy and professional identity formation in residency training: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2020;54(7):616–27. doi: 10.1111/medu.14073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brissette MD, Johnson KA, Raciti PM, McCloskey CB, Gratzinger DA, Conran RM, et al. Perceptions of unprofessional attitudes and behaviors: implications for Faculty Role modeling and Teaching Professionalism during Pathology Residency. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141(10):1394–401. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0477-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Côté L, Laughrea PA. Preceptors’ understanding and use of role modeling to develop the CanMEDS competencies in residents. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2014;89(6):934–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for Medical Education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185–91. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foster K, Roberts C. The heroic and the Villainous: a qualitative study characterising the role models that shaped senior doctors’ professional identity. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horsburgh J, Ippolito K. A skill to be worked at: using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marisette S, Shuvra MM, Sale J, Rezmovitz J, Mutasingwa D, Maxted J. Inconsistent role modeling of professionalism in family medicine residency: resident perspectives from 2 Ontario sites. Can family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2020;66(2):e55–e61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benbassat J. Role modeling in medical education: the importance of a reflective imitation. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2014;89(4):550–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taylor CA, Taylor JC, Stoller JK. The influence of mentorship and role modeling on developing physician-leaders: views of aspiring and established physician-leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1130–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tomizawa Y. Role modeling for female Surgeons in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;248(3):151–8. doi: 10.1620/tjem.248.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wright SM, Carrese JA. Serving as a physician role model for a diverse population of medical learners. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2003;78(6):623–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wright SM, Carrese JA. Excellence in role modelling: insight and perspectives from the pros. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):638–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McLean M. Is culture important in the choice of role models? Experiences from a culturally diverse medical school. Med Teach. 2004;26(2):142–9. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001653964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McLean M. The choice of role models by students at a culturally diverse south african medical school. Med Teach. 2004;26(2):133–41. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001653973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wyber R, Egan T. For better or worse: role models for New Zealand house officers. N Z Med J. 2007;120(1253):U2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haider SI, Gill RC, Riaz Q. Developing role models in clinical settings: a qualitative study of medical students, residents and clinical teachers. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2020;70(9):1498–504. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abdul-Khaliq I, Ingar A, Sardar S. Medical students perspectives on the ‘enhancement of role modelling in clinical educators’. Med Teach. 2020;42(9):1074–5. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1713310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adkoli BV, Al-Umran KU, Al-Sheikh M, Deepak KK, Al-Rubaish AM. Medical students’ perception of professionalism: a qualitative study from Saudi Arabia. Med Teach. 2011;33(10):840–5. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.541535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, van Mook WN. Community-based education: the influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):174–80. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1246711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baernstein A, Oelschlager AM, Chang TA, Wenrich MD. Learning professionalism: perspectives of preclinical medical students. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2009;84(5):574–81. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819f5f60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bahman Bijari B, Zare M, Haghdoost AA, Bazrafshan A, Beigzadeh A, Esmaili M. Factors associated with students’ perceptions of role modelling. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:333–9. doi: 10.5116/ijme.57eb.cca2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bahmanbijari B, Beigzadeh A, Etminan A, Najarkolai AR, Khodaei M, Askari SMS. The perspective of medical students regarding the roles and characteristics of a clinical role model. Electron physician. 2017;9(4):4124–30. doi: 10.19082/4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baker M, Wrubel J, Rabow MW. Professional development and the informal curriculum in end-of-life care. J cancer education: official J Am Association Cancer Educ. 2011;26(3):444–50. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bazrafkan L, Hayat AA, Tabei SZ, Amirsalari L. Clinical teachers as positive and negative role models: an explanatory sequential mixed method design. J Med ethics history Med. 2019;12:11. doi: 10.18502/jmehm.v12i11.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brown MEL, Coker O, Heybourne A, Finn GM. Exploring the hidden curriculum’s impact on medical students: professionalism, identity formation and the need for transparency. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(3):1107–21. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01021-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doja A, Bould MD, Clarkin C, Eady K, Sutherland S, Writer H. The hidden and informal curriculum across the continuum of training: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Med Teach. 2016;38(4):410–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1073241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Egnew TR, Wilson HJ. Role modeling the doctor-patient relationship in the clinical curriculum. Fam Med. 2011;43(2):99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Healy NA, Cantillon P, Malone C, Kerin MJ. Role models and mentors in surgery. Am J Surg. 2012;204(2):256–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Healy NA, Glynn RW, Malone C, Cantillon P, Kerin MJ. Surgical mentors and role models: prevalence, importance and associated traits. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(5):633–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jayasuriya-Illesinghe V, Nazeer I, Athauda L, Perera J. Role models and teachers: medical students perception of teaching-learning methods in clinical settings, a qualitative study from Sri Lanka. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:52. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0576-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lehmann LS, Sulmasy LS, Desai S. Hidden Curricula, Ethics, and professionalism: optimizing clinical learning environments in becoming and being a physician: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):506–8. doi: 10.7326/M17-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martinez W, Hickson GB, Miller BM, Doukas DJ, Buckley JD, Song J, et al. Role-modeling and medical error disclosure: a national survey of trainees. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2014;89(3):482–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mileder LP, Schmidt A, Dimai HP. Clinicians should be aware of their responsibilities as role models: a case report on the impact of poor role modeling. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:23479. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.23479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mohammadi E, Mirzazadeh A, Sohrabpour AA, Shahsavari H, Yaseri M, Mortaz Hejri S. Enhancement of role modelling in clinical educators: a randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2020;42(4):436–43. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1691720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohammadi E, Shahsavari H, Mirzazadeh A, Sohrabpour AA, Mortaz Hejri S. Improving role modeling in clinical Teachers: a narrative literature review. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2020;8(1):1–9. doi: 10.30476/jamp.2019.74929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Paice E, Heard S, Moss F. How important are role models in making good doctors? BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;325(7366):707–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Potisek NM, Fromme B, Ryan MS. Transform Role Modeling Into SUPERmodeling.Pediatrics. 2019;144(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Stahn B, Harendza S. Role models play the greatest role - a qualitative study on reasons for choosing postgraduate training at a university hospital. GMS Z fur medizinische Ausbildung. 2014;31(4):Doc45. doi: 10.3205/zma000937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tagawa M. Effects of undergraduate medical students’ individual attributes on perceptions of encounters with positive and negative role models. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:164. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0686-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wong A, Trollope-Kumar K. Reflections: an inquiry into medical students’ professional identity formation. Med Educ. 2014;48(5):489–501. doi: 10.1111/medu.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Burgess A, Goulston K, Oates K. Role modelling of clinical tutors: a focus group study among medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:17. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Byszewski A, Gill JS, Lochnan H. Socialization to professionalism in medical schools: a canadian experience. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:204. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0486-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chapman L, Mysko C, Coombridge H. Development of teaching, mentoring and supervision skills for basic training registrars: a frustrated apprenticeship? Intern Med J. 2021;51(11):1847–53. doi: 10.1111/imj.14935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):205–8. doi: 10.1080/01421590600643653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718–25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modelling–making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2008;336(7646):718–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39503.757847.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Herr KD, George E, Agarwal V, McKnight CD, Jiang L, Jawahar A, et al. Aligning the Implicit Curriculum with the Explicit Curriculum in Radiology. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(9):1268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Murakami M, Kawabata H, Maezawa M. The perception of the hidden curriculum on medical education: an exploratory study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2009;8(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1447-056X-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Park J, Woodrow SI, Reznick RK, Beales J, MacRae HM. Observation, reflection, and reinforcement: surgery faculty members’ and residents’ perceptions of how they learned professionalism. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2010;85(1):134–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c47b25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Passi V, Johnson N. The hidden process of positive doctor role modelling. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):700–7. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1087482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, Wright S, Hafferty F, Johnson N. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME Guide No. 27. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1422–36. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pm J, Krüger C, Bergh A-M, Ge P, Van Staden C, Jl R, et al. Medical students on the value of role models for developing soft skills - “That’s the way you do it. Afr J Psychiatry. 2006;9:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sternszus R, Cruess SR. Learning from role modelling: making the implicit explicit. Lancet. 2016;387(10025):1257–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wear D, Aultman JM, Varley JD, Zarconi J. Making fun of patients: medical students’ perceptions and use of derogatory and cynical humor in clinical settings. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2006;81(5):454–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000222277.21200.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wear D, Skillicorn J. Hidden in plain sight: the formal, informal, and hidden curricula of a psychiatry clerkship. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2009;84(4):451–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a80b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2006;81(7):661–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232423.81299.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yazigi A, Nasr M, Sleilaty G, Nemr E. Clinical teachers as role models: perceptions of interns and residents in a lebanese medical school. Med Educ. 2006;40(7):654–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Asghari F, Fard NN, Atabaki A. Are we proper role models for students? Interns’ perception of faculty and residents’ professional behaviour. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1030):519–23. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2010.110361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Azmand S, Ebrahimi S, Iman M, Asemani O. Learning professionalism through hidden curriculum: iranian medical students’ perspective. J Med ethics history Med. 2018;11:10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a best evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No 25 Medical teacher. 2013;35(7):e1252–66. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.789132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Burgess A, Oates K, Goulston K. Role modelling in medical education: the importance of teaching skills. Clin Teach. 2016;13(2):134–7. doi: 10.1111/tct.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Essers G, Van Weel-Baumgarten E, Bolhuis S. Mixed messages in learning communication skills? Students comparing role model behaviour in clerkships with formal training. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):e659–65. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Feraco AM, Brand SR, Mack JW, Kesselheim JC, Block SD, Wolfe J. Communication skills training in Pediatric Oncology: moving Beyond Role modeling. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(6):966–72. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Finn G, Garner J, Sawdon M. You’re judged all the time!‘ students’ views on professionalism: a multicentre study. Med Educ. 2010;44(8):814–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Keis O, Schneider A, Heindl F, Huber-Lang M, Öchsner W, Grab-Kroll C. How do german medical students perceive role models during clinical placements (“Famulatur”)? An empirical study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1624-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Leep Hunderfund AN, Dyrbye LN, Starr SR, Mandrekar J, Naessens JM, Tilburt JC, et al. Role modeling and Regional Health Care Intensity: U.S. Medical Student Attitudes toward and experiences with cost-conscious care. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2017;92(5):694–702. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Leman MA, Claramita M, Rahayu GR. Defining a “Healthy Role-Model” for Medical Schools: Learning Components that Count. J multidisciplinary Healthc. 2020;13:1325–35. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S279574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Leman MA, Claramita M, Rahayu GR. Factors influencing healthy role models in medical school to conduct healthy behavior: a qualitative study. Int J Med Educ. 2021;12:1–11. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5ff9.9a88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Levine MP. Role models’ influence on medical students’ professional development. AMA J ethics. 2015;17(2):144–8. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2015.17.02.jdsc1-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Malpas PJ, Corbett A. Modelling empathy in medical and nursing education. N Z Med J. 2012;125(1352):94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Maudsley RF. Role models and the learning environment: essential elements in effective medical education. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2001;76(5):432–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.McLean M. Clinical role models are important in the early years of a problem-based learning curriculum. Med Teach. 2006;28(1):64–9. doi: 10.1080/01421590500441711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mohammadi E, Mortaz Hejri S, Sohrabpour AA, Mirzazadeh A, Shahsavari H. Exploring clinical educators’ perceptions of role modeling after participating in a role modeling educational program. Med Teach. 2021;43(4):397–403. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1849590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Passi V, Johnson N. The impact of positive doctor role modeling. Med Teach. 2016;38(11):1139–45. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1170780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Patel MS, Reed DA, Smith C, Arora VM. Role-modeling cost-conscious Care–A national evaluation of perceptions of Faculty at Teaching Hospitals in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1294–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3242-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Piccinato CE, Rodrigues MLV, Rocha LA, Troncon LEA. Characteristics of role models who influenced medical residents to choose surgery as a specialty: exploratory study. Sao Paulo medical journal = Revista paulista de medicina. 2017;135(6):529–34. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2017.0053030517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Steele MM, Fisman S, Davidson B. Mentoring and role models in recruitment and retention: a study of junior medical faculty perceptions. Med Teach. 2013;35(5):e1130–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.735382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wittlin NM, Dovidio JF, Burke SE, Przedworski JM, Herrin J, Dyrbye L et al. Contact and role modeling predict bias against lesbian and gay individuals among early-career physicians: A longitudinal study. Social science & medicine (1982). 2019;238:112422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 140.Yoon JD, Ham SA, Reddy ST, Curlin FA. Role models’ influence on Specialty Choice for Residency Training: A National Longitudinal Study. J graduate Med Educ. 2018;10(2):149–54. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00063.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Balmer D, Serwint JR, Ruzek SB, Ludwig S, Giardino AP. Learning behind the scenes: perceptions and observations of role modeling in pediatric residents’ continuity experience. Ambul pediatrics: official J Ambul Pediatr Association. 2007;7(2):176–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Branch J, William T, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissmann P, Gracey CF, Mitchell G, et al. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hansen SE, Mathieu SS, Biery N, Dostal J. The emergence of Family Medicine Identity among First-Year residents: a qualitative study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):412–9. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.450912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lefkowitz A, Meitar D, Kuper A. Can doctors be taught virtue? J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(3):543–8. doi: 10.1111/jep.13398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Thiedke C, Blue AV, Chessman AW, Keller AH, Mallin R. Student observations and ratings of Preceptor’s interactions with patients: the hidden curriculum. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(4):312–6. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1604_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wald HS, Anthony D, Hutchinson TA, Liben S, Smilovitch M, Donato AA. Professional identity formation in medical education for humanistic, resilient physicians: pedagogic strategies for bridging theory to practice. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2015;90(6):753–60. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Jones WS, Hanson JL, Longacre JL. An intentional modeling process to teach professional behavior: students’ clinical observations of preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(3):264–9. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1603_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hendelman W, Byszewski A. Formation of medical student professional identity: categorizing lapses of professionalism, and the learning environment. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:139. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Hoskison K, Beasley BW. A conversation about the role of humiliation in teaching: the Ugly, the bad, and the good. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2019;94(8):1078–80. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Ahmadian Yazdi N, Bigdeli S, Soltani Arabshahi SK, Ghaffarifar S. The influence of role-modeling on clinical empathy of medical interns: a qualitative study. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2019;7(1):35–41. doi: 10.30476/JAMP.2019.41043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Boerebach BC, Lombarts KM, Keijzer C, Heineman MJ, Arah OA. The teacher, the physician and the person: how faculty’s teaching performance influences their role modelling. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e32089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Haider SI, Snead DR, Bari MF. Medical students’ perceptions of clinical Teachers as Role Model. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0150478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Holden J, Cox S, Irving G. Rethinking role models in general practice. Br J Gen practice: J Royal Coll Gen Practitioners. 2020;70(698):459–60. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X712517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Jochemsen-van der Leeuw HG, van Dijk N, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Wieringa-de Waard M. The attributes of the clinical trainer as a role model: a systematic review. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2013;88(1):26–34. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318276d070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kutob RM, Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D. The diverse functions of role models across primary care specialties. Fam Med. 2006;38(4):244–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lindberg O. Gender and role models in the education of medical doctors: a qualitative exploration of gendered ways of thinking. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:31–6. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5e08.b95b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Siegel BS. A view from the residents: effective preceptor role modeling is in. Ambul pediatrics: official J Ambul Pediatr Association. 2004;4(1):2–3. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2004)004<0002:AVFTRE>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Stephens EH, Dearani JA. On becoming a Master Surgeon: Role Models, Mentorship, Coaching, and apprenticeship. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(6):1746–53. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Beanlands RA, Robinson LJ, Venance SL. An LGBTQ + mentorship program enriched the experience of medical students and physician mentors. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(6):e159–e62. doi: 10.36834/cmej.69936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Bhatnagar V, Diaz S, Bucur PA. The need for more mentorship in Medical School. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e7984–e. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Byszewski A, Hendelman W, McGuinty C, Moineau G. Wanted: role models - medical students’ perceptions of professionalism. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Elzubeir MA, Rizk DE. Identifying characteristics that students, interns and residents look for in their role models. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):272–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Haque W, Gurney T, Reed WG, North CS, Pollio DE, Pollio EW, et al. Key attributes of a medical Learning Community Mentor at One Medical School. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(3):721–30. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00746-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Janssen AL, Macleod RD, Walker ST. Recognition, reflection, and role models: critical elements in education about care in medicine. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(4):389–95. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2004;329(7469):770–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Paukert JL, Richards BF. How medical students and residents describe the roles and characteristics of their influential clinical teachers. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2000;75(8):843–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200008000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Scherpbier AJJA. Cognitive apprenticeship in clinical practice: can it stimulate learning in the opinion of students? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(4):535–46. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the Clouds: three professionalism frameworks in Medical Education. Acad medicine: J Association Am Med Colleges. 2016;91(12):1606–11. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Kravet SJ, Christmas C, Durso S, Parson G, Burkhart K, Wright S. The intersection between clinical excellence and role modeling in medicine. J graduate Med Educ. 2011;3(4):465–8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-03-04-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Agarwal R, Sonnad SS, Beery J, Lewin J. Role models in academic radiology: current status and pathways to improvement. J Am Coll Radiology: JACR. 2010;7(1):50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]