Abstract

Aims

Data on sex and left ventricular assist device (LVAD) utilization and outcomes have been conflicting and mostly confined to US studies incorporating older devices. This study aimed to investigate sex‐related differences in LVAD utilization and outcomes in a contemporary European LVAD cohort.

Methods and results

This analysis is part of the multicentre PCHF‐VAD registry studying continuous‐flow LVAD patients. The primary outcome was all‐cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included ventricular arrhythmias, right ventricular failure, bleeding, thromboembolism, and the haemocompatibility score. Multivariable Cox regression models were used to assess associations between sex and outcomes. Overall, 457 men (81%) and 105 women (19%) were analysed. At LVAD implant, women were more often in Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) profile 1 or 2 (55% vs. 41%, P = 0.009) and more often required temporary mechanical circulatory support (39% vs. 23%, P = 0.001). Mean age was comparable (52.1 vs. 53.4 years, P = 0.33), and median follow‐up duration was 344 [range 147–823] days for women and 435 [range 190–816] days for men (P = 0.40). No significant sex‐related differences were found in all‐cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79 for female vs. male sex, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.50–1.27]). Female LVAD patients had a lower risk of ventricular arrhythmias (HR 0.56, 95% CI [0.33–0.95]) but more often experienced right ventricular failure. No significant sex‐related differences were found in other outcomes.

Conclusions

In this contemporary European cohort of LVAD patients, far fewer women than men underwent LVAD implantation despite similar clinical outcomes. This is important as the proportion of female LVAD patients (19%) was lower than the proportion of females with advanced HF as reported in previous studies, suggesting underutilization. Also, female patients were remarkably more often in INTERMACS profile 1 or 2, suggesting later referral for LVAD therapy. Additional research in female patients is warranted.

Keywords: Advanced heart failure, Left ventricular assist device, Utilization, Sex, Survival

Introduction

Both men and women are frequently affected by heart failure (HF), and in both sexes, HF is strongly associated with morbidity and mortality. 1 , 2 However, several sex‐related differences exist, such as the distribution of HF phenotypes and the aetiology of HF. 2 , 3 , 4 Although the overall lifetime risk of developing HF is comparable between men and women, women are underrepresented in HF trials. 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 Additionally, women are less likely to be treated with guideline‐recommended drugs. Reports on potential underutilization of device therapies such as implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy in women have been inconsistent. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 Even though it is suggested that women make up approximately one‐third of the advanced HF population, several studies have shown lower utilization of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) in women. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Furthermore, studies investigating sex‐related differences in LVAD outcomes provided conflicting results. Analyses of large US and European LVAD registries demonstrated worse clinical outcomes in women, whereas a smaller study and a meta‐analysis showed similar survival for women and men. 15 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 However, these previous studies contained only a very small proportion of the newest and currently predominant HeartMate 3 LVADs and primarily included data on US patients. Improving our understanding of sex differences in present‐day European LVAD management is necessary to further enhance LVAD care. Therefore, this analysis aimed to assess sex‐related differences in LVAD utilization and outcomes in a contemporary European cohort of LVAD patients.

Methods

The methods of the observational PCHF‐VAD registry have been described previously. 22 Briefly, continuous‐flow LVAD patients were included from 13 European HF tertiary referral centres by HF specialists—alumni of the Postgraduate Course in Heart Failure (PCHF) of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Heart Academy, forming the PCHF‐VAD registry. All participating centres acquired approval from the local ethics review boards (predominantly, a waiver of informed consent was obtained by the individual centres). The patient baseline (time of implantation) and outcome data were recorded and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools—a secure, web‐based application, 23 hosted at the University of Zagreb School of Medicine, serving as the data‐coordinating centre.

At the moment of this analysis, 583 patients implanted with a durable ventricular assist device between December 2006 and January 2020 were included in the registry. Patients with a pulsatile device (n = 4) or biventricular assist device (n = 11), as well as patients aged <18 years (n = 6), were excluded from this analysis. In total, 562 patients were included in this analysis.

The primary outcome was all‐cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included heart transplantation, weaning from LVAD support, hospitalization for HF, right ventricular (RV) failure (acute and chronic), LVAD‐related infection requiring systemic antibiotics, non‐fatal thromboembolic events, intracranial bleeding, non‐intracranial bleeding, LVAD exchange, and the haemocompatibility score (HCS).

Haemocompatibility score

To analyse the aggregate burden of haemocompatibility‐related adverse events (HRAEs), the HCS was calculated for all patients. Each HRAE received a points score, based on its clinical relevance (Table S1 ). The HCS was calculated for each patient by summing up all points associated with all HRAEs experienced by the patient during the follow‐up period. 24

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) for non‐normally distributed data and were compared between men and women by the Student's t‐test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data are expressed as counts and percentages and were compared by the Pearson's χ 2 test.

Cumulative survival was assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and was compared between men and women using the log‐rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for female vs. male sex for the different outcomes. For the survival analyses, the time of LVAD implantation was considered as the index date. The follow‐up duration was defined as time to last contact, heart transplantation, weaning from LVAD support, or death, whichever occurred first.

For the main analysis, a multivariable Cox regression model was used to test whether sex was associated with the outcomes. The association between sex and outcomes was adjusted for age, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) profile, baseline creatinine serum levels, need for mechanical circulatory support prior to LVAD implantation, need for vasopressor use prior to LVAD implantation, and the LVAD implant date quartile.

Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed to adjust the association between all‐cause mortality and sex for baseline covariates that were selected in a forward stepwise Cox proportional hazards model. Age, cardiac implantable electronic devices (including implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy) status; heart rate, LVAD type, LVAD intention, INTERMACS profile, aetiology of HF, known history of chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation/flutter, or ventricular arrhythmias, significant ventricular arrhythmias pre‐LVAD surgery, prior cardiac surgery, concomitant procedure with LVAD implant, life support pre‐LVAD surgery, diuretic use, beta‐blocker use, ivabradine use, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use, vasopressor use, ultrafiltration, mechanical ventilation, creatinine values, left ventricular (LV) internal dimension at end‐diastole, and LVAD implant date quartile were assessed in a forward stepwise selection process with a significance level of 0.05 and 0.10 for entry and removal thresholds, respectively. Following this process, the baseline covariates that came out significant were used in a Cox proportional hazard model for the secondary outcomes.

The number of missing data in the variables mentioned above is shown in Table S2 . Variables with <30% missing data were imputed using multiple imputation, whereas those with a larger proportion of missing data were not included in this analysis. If the missing variables showed a monotone pattern of missing values, the monotone method was used. Otherwise, an iterative Markov chain Monte Carlo method was used with a number of 10 iterations. A total of five imputations was performed, and the pooled data were analysed. The imputed data were only used for the multivariable analysis. A two‐sided P‐value of 0.05 or lower was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In this analysis, a total of 562 patients with a mean age of 53.1 ± 12.0 years were included. The cohort included 457 (81.3%) male and 105 (18.7%) female patients. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 . A higher proportion of women were critically ill at the time of LVAD implantation as women were more often in INTERMACS profile 1 or 2 (55.3% vs. 41.2%, P = 0.009) and more often in need of mechanical circulatory support pre‐LVAD implantation (39.2% vs. 23.0%, P = 0.001). Serum creatinine levels were lower and LV size was smaller in women. Additionally, women less often had diabetes mellitus or atrial fibrillation or flutter at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Overall population (n = 562) | Men (n = 457) | Women (n = 105) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 53 ± 12 | 53 ± 12 | 52 ± 12 | 0.33 |

| Geographical area | ||||

| Northwest Europe (the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany) | 373 (66.4) | 292 (63.9) | 81 (77.1) | 0.01 |

| Southeast Europe (Croatia, Poland, Lithuania, Italy, Spain, and Greece) | 189 (33.6) | 165 (36.1) | 24 (22.9) | |

| Quartiles of date of LVAD implant | ||||

| 1st quartile (6 Dec 2006–29 Oct 2012) | 143 (25.4) | 110 (24.1) | 33 (31.4) | 0.41 |

| 2nd quartile (30 Oct 2012–4 Aug 2015) | 143 (25.4) | 121 (26.5) | 22 (21.0) | |

| 3rd quartile (5 Aug 2015–16 Apr 2017) | 139 (24.7) | 114 (24.9) | 25 (23.8) | |

| 4th quartile (17 Apr 2017–28 Jan 2020) | 137 (24.4) | 112 (24.5) | 25 (23.8) | |

| ICD status | 0.34 | |||

| No ICD | 294 (53.3) | 235 (52.2) | 59 (57.8) | |

| Primary prevention | 180 (32.6) | 147 (32.7) | 33 (32.4) | |

| Secondary prevention | 78 (14.1) | 68 (15.1) | 10 (9.8) | |

| CRT status | ||||

| No CRT | 406 (74.1) | 325 (72.9) | 81 (79.4) | 0.12 |

| CRT‐P carrier | 14 (2.6) | 14 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CRT‐D carrier | 128 (23.4) | 107 (24.0) | 21 (20.6) | |

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 83.3 ± 19.0 | 82.5 ± 17.8 | 87.1 ± 23.3 | 0.072 |

| SBP, mmHg | 99.5 ± 13.9 | 100.0 ± 14.1 | 97.7 ± 13.0 | 0.16 |

| DBP, mmHg | 64.2 ± 10.9 | 64.4 ± 10.5 | 63.2 ± 12.2 | 0.32 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 4.6 | 26.1 ± 4.5 | 24.9 ± 5.3 | 0.025 |

| LVAD type | ||||

| HeartMate 2 | 265 (47.2) | 215 (47.0) | 50 (47.6) | 0.82 |

| HeartWare HVAD | 119 (21.2) | 94 (20.6) | 25 (23.8) | |

| HeartMate 3 | 157 (27.9) | 130 (28.4) | 27 (25.7) | |

| Other | 21 (3.7) | 18 (3.9) | 3 (2.9) | |

| LVAD destination | ||||

| BTT | 356 (66.8) | 292 (67.1) | 64 (65.3) | 0.081 |

| BTD | 90 (16.9) | 67 (15.4) | 23 (23.5) | |

| DT | 87 (16.3) | 76 (17.5) | 11 (11.2) | |

| INTERMACS profile | ||||

| 1 | 90 (16.5) | 61 (13.7) | 29 (28.2) | 0.004 |

| 2 | 150 (27.4) | 122 (27.5) | 28 (27.2) | |

| 3 | 176 (32.2) | 149 (33.6) | 27 (26.2) | |

| 4–7 | 131 (23.9) | 112 (25.2) | 19 (18.4) | |

| Aetiology of heart failure | ||||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 247 (44.0) | 204 (44.6) | 43 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 256 (45.6) | 211 (46.2) | 45 (42.9) | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 9 (1.6) | 7 (1.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Toxic cardiomyopathy | 15 (2.7) | 6 (1.3) | 9 (8.6) | |

| Non‐compaction cardiomyopathy | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Valvular disease | 6 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Myocarditis | 12 (2.1) | 9 (2.0) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Congenital/genetic | 6 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 6 (1.1) | 42 (9.2) | 17 (16.2) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 128 (22.8) | 105 (23.0) | 23 (21.9) | 0.81 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 114 (20.3) | 100 (21.9) | 14 (13.3) | 0.049 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 137 (24.4) | 117 (25.6) | 20 (19.0) | 0.16 |

| Coronary artery disease | 139 (24.7) | 120 (26.3) | 19 (18.1) | 0.080 |

| Prior MI | 211 (37.5) | 178 (38.9) | 33 (31.4) | 0.15 |

| Prior coronary revascularization | 170 (30.2) | 141 (30.9) | 29 (27.6) | 0.52 |

| COPD | 44 (7.8) | 40 (8.8) | 4 (3.8) | 0.089 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 173 (30.8) | 155 (33.9) | 18 (17.1) | 0.001 |

| Ventricular arrhythmias | 153 (27.2) | 127 (27.8) | 26 (24.8) | 0.53 |

| Cerebrovascular events | 41 (7.3) | 34 (7.4) | 7 (6.7) | 0.78 |

| Significant ventricular arrhythmias pre‐LVAD implant | ||||

| None | 308 (65.5) | 242 (63.2) | 66 (75.9) | 0.093 |

| 1 episode | 78 (16.6) | 64 (16.7) | 14 (16.1) | |

| 2 episodes | 34 (7.2) | 30 (7.8) | 4 (4.6) | |

| 3 episodes | 18 (3.8) | 17 (4.4) | 1 (1.1) | |

| ≥4 episodes | 32 (6.8) | 30 (7.8) | 2 (2.3) | |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 75 (13.3) | 65 (14.2) | 10 (9.5) | 0.20 |

| Concomitant procedure with LVAD implant | 99 (17.6) | 82 (17.9) | 17 (16.2) | 0.67 |

| Mechanical circulatory support pre‐LVAD implant | ||||

| None | 401 (74.0) | 339 (77.0) | 62 (60.8) | 0.007 |

| ECMO | 40 (7.4) | 30 (6.8) | 10 (9.8) | |

| Temporary LVAD | 5 (0.9) | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Temporary RVAD | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Temporary BiVAD | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IABP | 73 (13.5) | 51 (11.6) | 22 (21.6) | |

| Other | 20 (3.7) | 12 (2.7) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Medications | ||||

| Diuretic | 454 (91.0) | 374 (91.7) | 80 (87.9) | 0.26 |

| Beta‐blocker | 299 (64.4) | 252 (65.5) | 47 (59.5) | 0.31 |

| ACEi/ARB | 213 (44.9) | 176 (44.8) | 37 (45.7) | 0.88 |

| MRA | 315 (72.1) | 265 (73.8) | 50 (64.1) | 0.08 |

| Ivabradine | 45 (10.9) | 38 (11.1) | 7 (9.7) | 0.73 |

| Inotrope | 305 (66.6) | 243 (65.1) | 62 (72.9) | 0.17 |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 127.1 ± 56.0 | 131.4 ± 55.2 | 108.1 ± 55.8 | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin, μmol/L | 24.3 ± 20.5 | 24.8 ± 21.0 | 22.2 ± 18.5 | 0.30 |

| Echocardiographic data | ||||

| LVIDd, mm | 70.7 ± 12.5 | 72.3 ± 12.3 | 63.9 ± 11.3 | <0.001 |

| LVIDd/BSA ratio | 36.5 ± 6.8 | 36.4 ± 6.9 | 36.9 ± 6.6 | 0.61 |

| LVEF, % | 19.4 ± 7.5 | 19.2 ± 7.6 | 20.3 ± 6.8 | 0.24 |

ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; b.p.m., beats per minute; BiVAD, biventricular assist device; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; BTD, bridge to decision; BTT, bridge to transplant; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CRT‐D, CRT‐defibrillator; CRT‐P, CRT‐pacing; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DT, destination therapy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP, intra‐aortic balloon pump; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; INTERMACS, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension at end‐diastole; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Survival

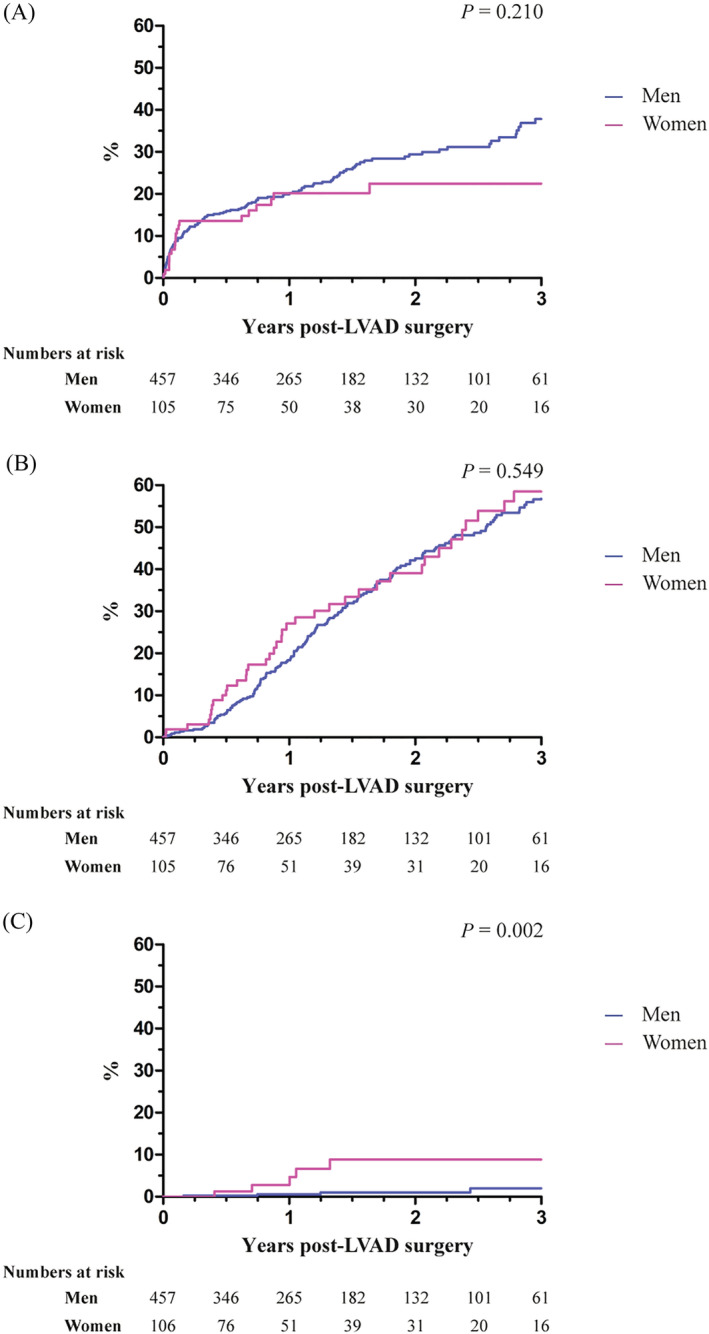

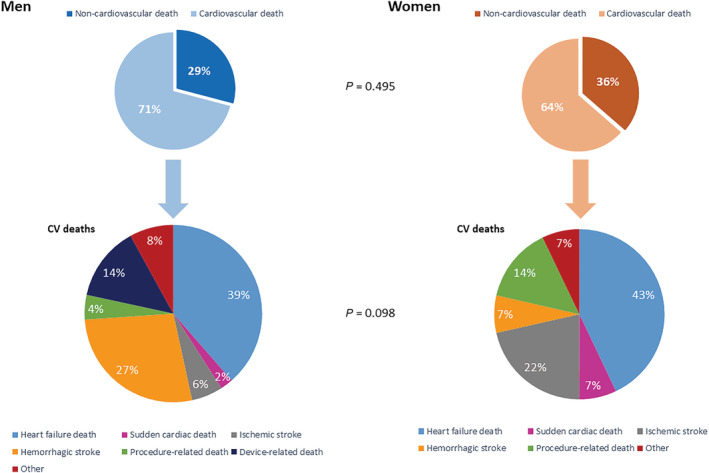

Women and men were followed for a median period of 344 [IQR 147–823] and 435 [IQR 190–816] days, respectively (P = 0.40). No differences were observed in the crude all‐cause mortality between men and women, as shown in Figure 1 . During the entire follow‐up period, 29% of the male and 21% of the female patients died (P = 0.084). Female patients were numerically less likely to die during follow‐up, but this difference was not statistically significant after adjustments for age, INTERMACS profile, creatinine serum levels, preoperative need for mechanical circulatory support or vasodilator use, and the quartiles of date of LVAD implantation (HR 0.79, 95% CI [0.50–1.27]; Table 2 ). The causes of death were not different between men and women and are presented in Figure 2 .

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots of time to (A) all‐cause mortality, (B) heart transplantation (censored for death), and (C) weaning from left ventricular assist device (LVAD) (censored for death) according to sex.

Table 2.

Frequency (proportion) and hazard ratios for the studied endpoints

| Overall population (n = 562) | Men (n = 457) | Women (n = 105) | P‐value | Unadjusted HR [95% CI] | Adjusted HR [95% CI] a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause mortality | 156 (27.8) | 134 (29.3) | 22 (21.0) | 0.084 | 0.75 [0.48–1.18] | 0.79 [0.50–1.27] |

| HF hospitalization | 108 (20.8) | 85 (20.1) | 23 (24.0) | 0.41 | 1.16 [0.73–1.86] | 1.27 [0.78–2.06] |

| RV failure | 116 (21.4) | 87 (19.7) | 29 (29.0) | 0.041 | 1.52 [0.98–2.35] | 1.57 [1.00–2.49] |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 79 (14.8) | 66 (15.2) | 13 (13.0) | 0.57 | 0.83 [0.45–1.54] | 0.98 [0.52–1.86] |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 155 (28.4) | 137 (30.9) | 18 (17.6) | 0.008 | 0.50 [0.30–0.85] | 0.56 [0.33–0.95] |

| LVAD‐related infections requiring AB | 188 (34.6) | 156 (35.4) | 32 (31.4) | 0.44 | 0.84 [0.56–1.25] | 0.76 [0.50–1.14] |

| Non‐intracranial bleeding | 118 (22.1) | 99 (22.7) | 19 (19.6) | 0.51 | 0.88 [0.54–1.45] | 0.88 [0.53–1.46] |

| Intracranial bleeding | 46 (8.6) | 39 (8.9) | 7 (7.1) | 0.56 | 0.87 [0.39–1.94] | 0.78 [0.32–1.89] |

| Pump thrombosis | 41 (7.6) | 38 (8.6) | 3 (3.1) | 0.06 | 0.35 [0.11–1.15] | 0.38 [0.12–1.26] |

| Non‐fatal thromboembolic events | 56 (10.4) | 44 (10.0) | 12 (12.2) | 0.51 | 1.21 [0.64–2.29] | 1.31 [0.68–2.54] |

| Weaning from LVAD | 9 (1.6) | 4 (0.9) | 5 (4.8) | 0.004 | 6.07 [1.63–22.62] | 3.10 [0.68–14.07] |

| LVAD exchange | 22 (4.1) | 18 (4.1) | 4 (4.1) | 0.98 | 0.93 [0.31–2.75] | 0.85 [0.28–2.61] |

| Heart transplantation | 218 (38.8) | 175 (38.3) | 43 (41.0) | 0.61 | 1.11 [0.79–1.55] | 1.01 [0.70–1.46] |

AB, antibiotics; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; RV, right ventricular.

Adjusted for age, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support profile, creatinine serum levels at baseline, preoperative need for life support, preoperative vasodilator use, and quartiles of date of LVAD implantation.

Figure 2.

Detailed causes of death stratified by sex. CV, cardiovascular.

Secondary endpoints

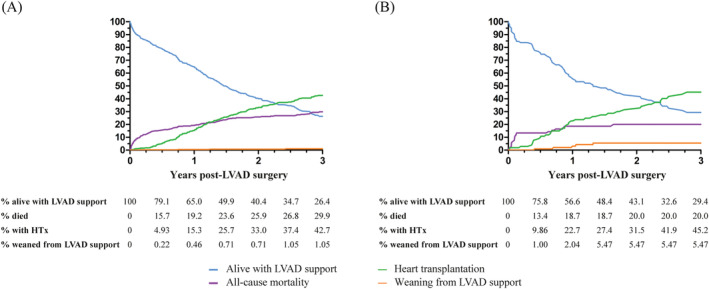

No sex‐related differences were observed in the proportion of patients undergoing heart transplantation (HR 1.01, 95% CI [0.70–1.46]; Figure 1 ). Numerically, women were significantly more often weaned from LVAD support, but this was not statistically significant after multivariable adjustments (HR 3.10, 95% CI [0.68–14.1]; Table 2 ). Peripartum cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy were the most frequent causes of HF in women who recovered from LVAD support (Table S3 ). The results from the competing outcome analysis are shown in Figure 3 .

Figure 3.

Competing event analysis in (A) men and (B) women. HTx, heart transplantation; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Female sex was associated with a significantly lower crude and adjusted risk of ventricular arrhythmias post‐LVAD implant (adjusted HR 0.56, 95% CI [0.33–0.95]; Table 2 ). Female patients had a higher incidence of RV failure, although without statistically significant increase in risk thereof (HR 1.57, 95% CI [1.00–2.49], P = 0.053).

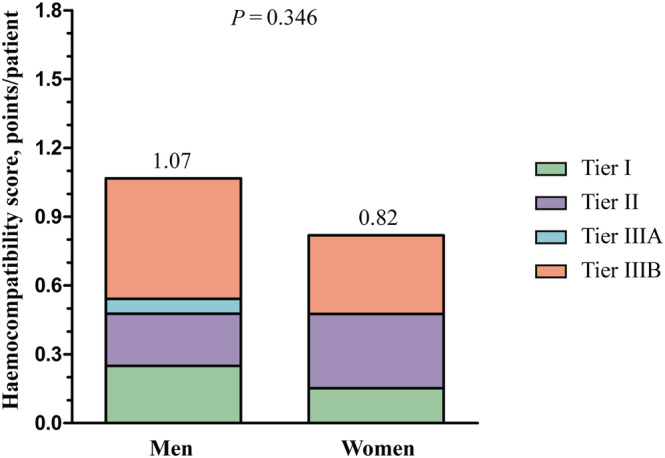

No significant differences between men and women were found in the occurrence of pump thrombosis, non‐fatal thromboembolic events, or bleeding (Table 2 ). A small, non‐significant difference between men and women was found in the median HCS, as shown in Figure 4 . Furthermore, the risk of HF hospitalizations, new‐onset atrial fibrillation or flutter, and LVAD‐related infections requiring antibiotics was similar for men and women (Table 2 ).

Figure 4.

Haemocompatibility score according to sex.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analysis, in which the association between sex and the primary and secondary outcomes was adjusted using a forward stepwise Cox regression model, are shown in Table S4 . Similar to the main analysis, there was no significant difference in all‐cause mortality. However, female sex was significantly associated with RV failure post‐LVAD implantation and weaning from LVAD support.

Discussion

In this contemporary European LVAD registry reflecting real‐world clinical practice at multiple HF tertiary referral centres, we demonstrated that fewer women than men underwent LVAD implantation (19% vs. 81%, respectively). Also, women were implanted at a more advanced stage and were more critically ill pre‐LVAD surgery; nevertheless, no significant survival differences were observed between men and women. Furthermore, only minor sex‐related differences in LVAD‐related outcomes were observed, with women less often at risk of ventricular arrhythmias, more often suffering from RV failure, and more often having explant for recovery (albeit rarely altogether).

Previous studies have investigated sex differences in the utilization and outcomes of LVAD therapy. However, most of these studies have been performed in the United States, reflected an earlier period, and included almost exclusively HeartWare HVAD or HeartMate 2 devices. 15 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 As opposed to these earlier studies, the current study included a relatively large number of patients with a HeartMate 3 device, and this registry therefore provides unique insights into the contemporary LVAD management at European tertiary referral centres using state‐of‐the‐art LVADs. 25 , 26 , 27

Potential left ventricular assist device underutilization

Women remain underrepresented in large pharmacological clinical HF trials, as well as in LVAD clinical trials. 7 , 25 Currently, less women than men receive an LVAD, as demonstrated in this registry as well as in other studies, with the proportion of female patients spanning from 20.8% to 23.2%. 15 , 16 , 17 Despite several large registries showing that women make up approximately one‐third of the advanced and worsening HF populations, only 19% of our cohort were female, suggesting potential LVAD underutilization in female patients. 18 , 28 Several reasons might contribute to the lower utilization of LVADs in women. Firstly, women are more frequently diagnosed with HF with preserved ejection fraction, in whom LVAD support is not indicated. 29 Secondly, the lower inclusion rate of women in LVAD trials has led to a gap of evidence in the effectiveness of LVAD support in women, which might have caused a difference in the utilization of LVAD therapy. Additionally, in the pulsatile‐flow device era, female patients were deemed less suited for implantation of the larger pumps due to their smaller intrathoracic volume. 15 , 20 Thus, for this and potentially other reasons, LVAD therapy may be less often utilized in women. Furthermore, it has been suggested that women are more likely to decline LVAD support than men. 30 , 31 In a multinational European screening study, women were somewhat less likely to be eligible for LVAD and/or heart transplantation but considerably less likely to accept LVAD and/or transplantation if indicated. 32 Additionally, it could be that physicians and patients wait too long with the decision to proceed towards LVAD implantation, as reflected by the strikingly high proportion of women in the worst INTERMACS profile and the higher need for mechanical circulatory support in women. 20 Another explanation for the worse INTERMACS profile and high need for mechanical circulatory support in women might be that they are more often affected by acute disease, which possibly explains their better renal function, lower prevalence of atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias prior to LVAD implantation, and smaller LV size, which possibly reflects less time for remodelling due to acuteness of disease. Finally, the inconsistencies in current literature on sex‐related differences in LVAD outcomes might have influenced LVAD implantation rates in women. 15 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 21

Outcomes after left ventricular assist device implantation

Survival differences between male and female LVAD patients have previously been investigated and inconsistent results have been reported. 15 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 The two largest databases, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and INTERMACS registry, included a combined total of 32 173 LVAD patients, and both studies demonstrated a higher adjusted mortality risk for women. 15 , 16 A smaller European sex‐specific analysis from the European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support (EUROMACS) also demonstrated worse survival in women. 20 Conversely, a sub‐analysis from the Mechanical Circulatory Support Research Network as well as a recently published meta‐analysis did not show survival differences between male and female LVAD recipients. 19 , 21

In contrast to most of the earlier studies, survival for women in our study was at least as good as for men despite a more critically ill state prior to LVAD implantation. This was reflected by lower INTERMACS profile and higher need for mechanical circulatory support, which have been associated with worse outcome. 33 , 34 The observed discrepancy regarding survival differences may partially be attributed to differences in the devices studied. Earlier studies including pulsatile‐flow LVADs predominantly demonstrated worse survival in women. 17 Later studies on sex differences in the continuous‐flow LVAD era mainly incorporated older devices, whereas 28% of our overall study population had a HeartMate 3 device implanted. This is a relatively large proportion compared with the UNOS and EUROMACS studies in which 2.7% and 0.1% of the overall population received a HeartMate 3, respectively, while the INTERMACS study did not incorporate any data from HeartMate 3 LVADs. 15 , 16 , 20 This is important as the MOMENTUM 3 trial demonstrated superiority of the HeartMate 3 LVAD in terms of a lower risk of disabling stroke or reoperation for replacement or removal due to malfunction and is considered the most contemporary LVAD in Europe. 25 An additional subgroup analysis of the MOMENTUM 3 trial showed comparably favourable outcomes for men and women, both on the short and long terms. 35 , 36 The higher proportion of HeartMate 3 devices in our study may further explain why the risk of bleeding and thromboembolic events was comparable for men and women in our study as opposed to earlier studies reporting an increased risk of major bleeding events. 16 , 20 The HVAD and HeartMate 2 have been associated with higher stroke, pump thrombosis, and major bleeding rates, which may translate into a higher mortality risk, as bleeding events and pump thrombosis have been associated with higher risk of mortality. 20 , 25 , 37 , 38 Several studies did not find a difference in bleeding risk, and inconsistent results have been reported on whether women are at an increased risk for thromboembolic events. 16 , 20 , 21 , 39 , 40 To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to investigate sex differences with regard to HRAE by using the HCS and found no significant differences between men and women in our cohort.

In very carefully selected patients with cardiac recovery after LVAD surgery, weaning from LVAD support can be a viable option. 41 Similar to a recent INTERMACS registry analysis, our results demonstrate that women were more likely to recover from LVAD support. 16 This might be explained by the observed difference in the aetiology of HF, especially due to the (partial) reversibility of peripartum cardiomyopathy. 42 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that women have more favourable reverse remodelling on LVAD support compared with men. 43

In line with earlier studies, female LVAD patients showed a trend towards increased risk of RV failure. 19 , 20 It has been suggested that ventricular arrhythmias might explain the increased risk of RV failure in women, but in our study, women were less often affected by ventricular arrhythmias post‐LVAD implant. 20 , 44 However, a higher proportion of women were in INTERMACS profile 1 (28.2% of female vs. 13.7% of male patients) and supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which may explain the higher incidence of RV failure. Furthermore, the smaller LV size of women has been associated with RV failure through leftward shifting of the interventricular septum, which increases RV wall stress and reduces RV contractility, and may therefore also have contributed to the increased risk of RV failure. 45 , 46

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, data missing not at random might have introduced bias to our results, although we have used the multiple imputation method to account for this in the multivariable Cox proportional hazard models. Secondly, due to its retrospective design, causality could not be investigated. Thirdly, due to the small number of patients weaned from LVAD support, our findings on recovery from LVAD support should be interpreted with caution. Finally, selection bias or misclassification of data might have occurred.

Conclusions

In this cohort of contemporary LVAD patients from multiple European HF tertiary referral centres, fewer women underwent LVAD implantation as compared to men. This is important as the proportion of female LVAD patients was lower than the proportion of females with advanced HF as reported in previous studies, suggesting underutilization. Furthermore, female patients were referred for LVAD implantation in an inferior INTERMACS profile, suggesting later referral for LVAD therapy. Despite a more critically ill state prior to implantation, LVAD therapy appears at least as beneficial in terms of survival and clinical outcomes in women as in men. This should reduce the hesitance of referring female patients for LVAD implantation, thus providing opportunities for improved outcome similar to male patients. Additional research is needed to investigate whether LVAD utilization in women is lower than required, why it occurs, and whether this trend can be diverted to a more upstream use of LVAD therapy in women.

Conflict of interest

N.J. reports personal fees and non‐financial support from Servier, personal fees from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Krka, Sanofi Genzyme, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bayer, and non‐financial support from Abbott, outside the submitted work. A.C.P. reports personal fees from Novartis, Bayer, Vifor, and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. I.P. reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Servier, Krka, and Corvia, and personal fees and non‐financial support from Novartis, Pfizer, Bayer, Sandoz, Abbott, and Sanofi Aventis, outside the submitted work. A.J.F. reports personal fees from Alnylam, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius, Imedos Systems, Medtronic, MSD, Mundipharma, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, Vifor, and ZOLL, and grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Novartis, outside the submitted work. L.H.L. reports personal fees from Merck, Bayer, Pharmacosmos, Abbott, Medscape, Myokardia, Sanofi, Lexicon, and Radcliffe Cardiology, grants and personal fees from Vifor‐Fresenius, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis, and grants from Boston Scientific, outside the submitted work. D.M. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Teva, and Servier, outside the submitted work. F.R. has not received personal payments by pharmaceutical companies or device manufacturers in the last 3 years (remuneration for the time spent in activities, such as participation as steering committee member of clinical trials and member of the Pfizer Research Award selection committee in Switzerland, were made directly to the University of Zurich). The Department of Cardiology (University Hospital of Zurich/University of Zurich) reports research, educational, and/or travel grants from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin Heart, B. Braun, Biosense Webster, Biosensors Europe AG, Biotronik, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bracco, Cardinal Health Switzerland, Corteria, Daiichi, Diatools AG, Edwards Lifesciences, Guidant Europe NV (BS), Hamilton Health Sciences, Kaneka Corporation, Kantar, Labormedizinisches Zentrum, Medtronic, MSD, Mundipharma Medical Company, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Orion, Pfizer, Quintiles Switzerland Sarl, Sahajanand IN, Sanofi, Sarstedt AG, Servier, SIS Medical, SSS International Clinical Research, Terumo Deutschland, Trama Solutions, V‐Wave, Vascular Medical, Vifor, Wissens Plus, and ZOLL. The research and educational grants do not impact on F.R.'s personal remuneration. M.C. reports grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants from Abbott, personalfees from GE Healthcare, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Sanofi, and LivaNova, non‐financial support from Corvia, and personal fees and non‐financial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. J.J.B. reports personal fees from Abbott, outside the submitted work. All other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Classification of haemocompatibility score.

Table S2. Number (percentage) of missing data.

Table S3. Etiology of heart failure in patients who were weaned from LVAD support.

Table S4. Numbers and hazard ratios for the endpoints after a forward stepwise selection process.

Radhoe, S. P. , Jakus, N. , Veenis, J. F. , Timmermans, P. , Pouleur, A.‐C. , Rubís, P. , Van Craenenbroeck, E. M. , Gaizauskas, E. , Barge‐Caballero, E. , Paolillo, S. , Grundmann, S. , D'Amario, D. , Braun, O. Ö. , Gkouziouta, A. , Planinc, I. , Macek, J. L. , Meyns, B. , Droogne, W. , Wierzbicki, K. , Holcman, K. , Flammer, A. J. , Gasparovic, H. , Biocina, B. , Milicic, D. , Lund, L. H. , Ruschitzka, F. , Brugts, J. J. , and Cikes, M. (2023) Sex‐related differences in left ventricular assist device utilization and outcomes: results from the PCHF‐VAD registry. ESC Heart Failure, 10: 1054–1065. 10.1002/ehf2.14261.

Sumant P. Radhoe, Nina Jakus, Jasper J. Brugts and Maja Cikes contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Jasper J. Brugts, Email: j.brugts@erasmusmc.nl.

Maja Cikes, Email: maja.cikes@gmail.com.

References

- 1. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Framingham Heart S. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002; 106: 3068–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehta PA, Cowie MR. Gender and heart failure: a population perspective. Heart. 2006; 92: iii14–iii18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. He J, Ogden LG, Bazzano LA, Vupputuri S, Loria C, Whelton PK. Risk factors for congestive heart failure in US men and women: NHANES I epidemiologic follow‐up study. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161: 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Smith G, Fish RH, Steiner JF, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Gender, age, and heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41: 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alehagen U, Ericsson A, Dahlström U. Are there any significant differences between females and males in the management of heart failure? Gender aspects of an elderly population with symptoms associated with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009; 15: 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MC, Straus SM, Hofman A, Deckers JW, Witteman JC, Stricker BH. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure: the Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25: 1614–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lam CSP, Arnott C, Beale AL, Chandramouli C, Hilfiker‐Kleiner D, Kaye DM, Ky B, Santema BT, Sliwa K, Voors AA. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40: 3859–68c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abrahamyan L, Sahakyan Y, Wijeysundera HC, Krahn M, Rac VE. Gender differences in utilization of specialized heart failure clinics. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018; 27: 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galvao M, Kalman J, DeMarco T, Fonarow GC, Galvin C, Ghali JK, Moskowitz RM. Gender differences in in‐hospital management and outcomes in patients with decompensated heart failure: analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). J Card Fail. 2006; 12: 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lenzen MJ, Rosengren A, Scholte OP, Reimer WJ, Follath F, Boersma E, Simoons ML, Cleland JG, Komajda M. Management of patients with heart failure in clinical practice: differences between men and women. Heart. 2008; 94: e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Linde C, Stahlberg M, Benson L, Braunschweig F, Edner M, Dahlstrom U, Alehagen U, Lund LH. Gender, underutilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy, and prognostic impact of QRS prolongation and left bundle branch block in heart failure. Europace. 2015; 17: 424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lund LH, Braunschweig F, Benson L, Stahlberg M, Dahlstrom U, Linde C. Association between demographic, organizational, clinical, and socio‐economic characteristics and underutilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy: results from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017; 19: 1270–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Piña IL, Kokkinos P, Kao A, Bittner V, Saval M, Clare B, Goldberg L, Johnson M, Swank A, Ventura H, Moe G, Fitz‐Gerald M, Ellis SJ, Vest M, Cooper L, Whellan D, Investigators H‐A. Baseline differences in the HF‐ACTION trial by sex. Am Heart J. 2009; 158: S16–S23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Veenis JF, Rocca HB, Linssen GC, Erol‐Yilmaz A, Pronk AC, Engelen DJ, van Tooren RM, Koornstra‐Wortel HJ, de Boer RA, van der Meer P, Hoes AW, Brugts JJ, CHECK‐HF investigators . Impact of sex‐specific target dose in chronic heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020; 28: 957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeFilippis EM, Truby LK, Garan AR, Givens RC, Takeda K, Takayama H, Naka Y, Haythe JH, Farr MA, Topkara VK. Sex‐related differences in use and outcomes of left ventricular assist devices as bridge to transplantation. JACC Heart Fail. 2019; 7: 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gruen J, Caraballo C, Miller PE, McCullough M, Mezzacappa C, Ravindra N, Mullan CW, Reinhardt SW, Mori M, Velazquez E, Geirsson A, Ahmad T, Desai NR. Sex differences in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices for end‐stage heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2020; 75: 807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joshi AA, Lerman JB, Sajja AP, Dahiya G, Gokhale AV, Dey AK, Kyvernitakis A, Halbreiner MS, Bailey S, Alpert CM, Poornima IG, Murali S, Benza RL, Kanwar M, Raina A. Sex‐based differences in left ventricular assist device utilization: insights from the nationwide inpatient sample 2004 to 2016. Circ Heart Fail. 2019; 12: e006082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Costanzo MR, Mills RM, Wynne J. Characteristics of “Stage D” heart failure: insights from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry Longitudinal Module (ADHERE LM). Am Heart J. 2008; 155: 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blumer V, Mendirichaga R, Hernandez GA, Zablah G, Chaparro SV. Sex‐specific outcome disparities in patients receiving continuous‐flow left ventricular assist devices: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. ASAIO J. 2018; 64: 440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Magnussen C, Bernhardt AM, Ojeda FM, Wagner FM, Gummert J, de By T, Krabatsch T, Mohacsi P, Rybczynski M, Knappe D, Sill B, Deuse T, Blankenberg S, Schnabel RB, Reichenspurner H. Gender differences and outcomes in left ventricular assist device support: the European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018; 37: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meeteren JV, Maltais S, Dunlay SM, Haglund NA, Beth Davis M, Cowger J, Shah P, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD, Stulak JM. A multi‐institutional outcome analysis of patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation stratified by sex and race. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017; 36: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cikes M, Jakus N, Claggett B, Brugts JJ, Timmermans P, Pouleur AC, Rubis P, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Gaizauskas E, Grundmann S, Paolillo S, Barge‐Caballero E, D'Amario D, Gkouziouta A, Planinc I, Veenis JF, Jacquet LM, Houard L, Holcman K, Gigase A, Rega F, Rucinskas K, Adamopoulos S, Agostoni P, Biocina B, Gasparovic H, Lund LH, Flammer AJ, Metra M, Milicic D, Ruschitzka F, PCHF‐VAD registry . Cardiac implantable electronic devices with a defibrillator component and all‐cause mortality in left ventricular assist device carriers: results from the PCHF‐VAD registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019; 21: 1129–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mehra MR. The burden of haemocompatibility with left ventricular assist systems: a complex weave. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40: 673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mehra MR, Uriel N, Naka Y, Cleveland JC Jr, Yuzefpolskaya M, Salerno CT, Walsh MN, Milano CA, Patel CB, Hutchins SW, Ransom J, Ewald GA, Itoh A, Raval NY, Silvestry SC, Cogswell R, John R, Bhimaraj A, Bruckner BA, Lowes BD, Um JY, Jeevanandam V, Sayer G, Mangi AA, Molina EJ, Sheikh F, Aaronson K, Pagani FD, Cotts WG, Tatooles AJ, Babu A, Chomsky D, Katz JN, Tessmann PB, Dean D, Krishnamoorthy A, Chuang J, Topuria I, Sood P, Goldstein DJ, Investigators M. A fully magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device—final report. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380: 1618–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jakus N, Brugts JJ, Claggett B, Timmermans P, Pouleur AC, Rubis P, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Gaizauskas E, Barge‐Caballero E, Paolillo S, Grundmann S, D'Amario D, Braun OO, Gkouziouta A, Meyns B, Droogne W, Wierzbicki K, Holcman K, Planinc I, Skoric B, Flammer AJ, Gasparovic H, Biocina B, Lund LH, Milicic D, Ruschitzka F, Cikes M, PCHF‐VAD registry . Improved survival of left ventricular assist device carriers in Europe according to implantation eras—results from the PCHF‐VAD registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022; 24: 1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Radhoe SP, Veenis JF, Jakus N, Timmermans P, Pouleur A, Rubís P, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Gaizauskas E, Barge‐Caballero E, Paolillo S, Grundmann S, D'Amario D, Braun OÖ, Gkouziouta A, Planinc I, Samardzic J, Meyns B, Droogne W, Wierzbicki K, Holcman K, Flammer AJ, Gasparovic H, Biocina B, Lund LH, Milicic D, Ruschitzka F, Cikes M, Brugts JJ. How does age affect outcomes after left ventricular assist device implantation: results from the PCHF‐VAD registry. ESC Heart Fail. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ezekowitz J, Mentz RJ, Westerhout CM, Sweitzer NK, Givertz MM, Pina IL, O'Connor CM, Greene SJ, McMullan C, Roessig L, Hernandez AF, Armstrong PW. Participation in a heart failure clinical trial: perspectives and opportunities from the VICTORIA trial and VICTORIA simultaneous registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2021; 14: e008242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ammar KA, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Kors JA, Redfield MM, Burnett JC Jr, Rodeheffer RJ. Prevalence and prognostic significance of heart failure stages: application of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association heart failure staging criteria in the community. Circulation. 2007; 115: 1563–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bruce CR, Kostick KM, Delgado ED, Wilhelms LA, Volk RJ, Smith ML, McCurdy SA, Loebe M, Estep JD, Blumenthal‐Barby JS. Reasons why eligible candidates decline left ventricular assist device placement. J Card Fail. 2015; 21: 835–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Petrov G, Lehmkuhl E, Smits JM, Babitsch B, Brunhuber C, Jurmann B, Stein J, Schubert C, Merz NB, Lehmkuhl HB, Hetzer R. Heart transplantation in women with dilated cardiomyopathy. Transplantation. 2010; 89: 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lund LH, Trochu JN, Meyns B, Caliskan K, Shaw S, Schmitto JD, Schibilsky D, Damme L, Heatley J, Gustafsson F. Screening for heart transplantation and left ventricular assist system: results from the ScrEEning for advanced Heart Failure treatment (SEE‐HF) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 20: 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, Myers SL, Miller MA, Baldwin JT, Young JB. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015; 34: 1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shah P, Pagani FD, Desai SS, Rongione AJ, Maltais S, Haglund NA, Dunlay SM, Aaronson KD, Stulak JM, Davis MB, Salerno CT, Cowger JA, Mechanical Circulatory Support Research N . Outcomes of patients receiving temporary circulatory support before durable ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017; 103: 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goldstein DJ, Mehra MR, Naka Y, Salerno C, Uriel N, Dean D, Itoh A, Pagani FD, Skipper ER, Bhat G, Raval N, Bruckner BA, Estep JD, Cogswell R, Milano C, Fendelander L, O'Connell JB, Cleveland J, Investigators M. Impact of age, sex, therapeutic intent, race and severity of advanced heart failure on short‐term principal outcomes in the MOMENTUM 3 trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018; 37: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Cleveland JC, Cowger JA, Hall S, Salerno CT, Naka Y, Horstmanshof D, Chuang J, Wang A, Uriel N. Five‐year outcomes in patients with fully magnetically levitated vs axial‐flow left ventricular assist devices in the MOMENTUM 3 randomized trial. JAMA. 2022; 328: 1233–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lalonde SD, Alba AC, Rigobon A, Ross HJ, Delgado DH, Billia F, McDonald M, Cusimano RJ, Yau TM, Rao V. Clinical differences between continuous flow ventricular assist devices: a comparison between HeartMate II and HeartWare HVAD. J Card Surg. 2013; 28: 604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stulak JM, Davis ME, Haglund N, Dunlay S, Cowger J, Shah P, Pagani FD, Aaronson KD, Maltais S. Adverse events in contemporary continuous‐flow left ventricular assist devices: a multi‐institutional comparison shows significant differences. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016; 151: 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morris AA, Pekarek A, Wittersheim K, Cole RT, Gupta D, Nguyen D, Laskar SR, Butler J, Smith A, Vega JD. Gender differences in the risk of stroke during support with continuous‐flow left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015; 34: 1570–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sherazi S, Kutyifa V, McNitt S, Papernov A, Hallinan W, Chen L, Storozynsky E, Johnson BA, Strawderman RL, Massey HT, Zareba W, Alexis JD. Effect of gender on the risk of neurologic events and subsequent outcomes in patients with left ventricular assist devices. Am J Cardiol. 2017; 119: 297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, Potapov E, Lehmkuhl HB, Hetzer R. Long‐term results in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy after weaning from left ventricular assist devices. Circulation. 2005; 112: I37–I45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patel H, Madanieh R, Kosmas CE, Vatti SK, Vittorio TJ. Reversible cardiomyopathies. Clin Med Insights Cardi`ol. 2015; 9: 7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kenigsberg BB, Majure DT, Sheikh FH, Afari‐Armah N, Rodrigo M, Hofmeyer M, Molina EJ, Wang Z, Boyce S, Najjar SS, Mohammed SF. Sex‐associated differences in cardiac reverse remodeling in patients supported by contemporary left ventricular assist devices. J Card Fail. 2020; 26: 494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garan AR, Levin AP, Topkara V, Thomas SS, Yuzefpolskaya M, Colombo PC, Takeda K, Takayama H, Naka Y, Whang W, Jorde UP, Uriel N. Early post‐operative ventricular arrhythmias in patients with continuous‐flow left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015; 34: 1611–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anne Dual S, Nayak A, Hu Y, Schmid Daners M, Morris AA, Cowger J. Does size matter for female continuous‐flow LVAD recipients? A translational approach to a decade long question. ASAIO J. 2022; 68: 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lampert BC, Teuteberg JJ. Right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015; 34: 1123–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Classification of haemocompatibility score.

Table S2. Number (percentage) of missing data.

Table S3. Etiology of heart failure in patients who were weaned from LVAD support.

Table S4. Numbers and hazard ratios for the endpoints after a forward stepwise selection process.