Abstract

Background

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a main cause of chronic renal failure. Despite decades of extensive study, the molecular mechanisms underlying diabetic tubulointerstitial injury remain unclear. We aim to identify key transcription factor genes involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury.

Methods

A microarray dataset (GSE30122) from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) was downloaded. A total of 38 transcription factor genes based on 166 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by UCSC_TFBS.

Results

The regulatory network showed connections between the top 10 transcription factors and their target DEGs. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of targeted DEGs indicated that extracellular space, extracellular exosome, cell surface and complement and coagulation cascades were most significantly enriched. Utilizing Nephroseq v5 online platform, the mRNA expression pattern analysis of transcription factor genes demonstrated that mRNA expression of CDC5, CEBPA, FAC1, HFH1, IRF1, NFE2 and TGIF1 increased in renal tubulointerstitium of DN patients compared with normal controls while that of CEBPB and FOXO4 decreased in renal tubulointerstitium of DN patients compared with normal controls. Correlation analysis between mRNA expression of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium and clinical features showed that AP1, BACH1, CDC5, FAC1, FOXD1, FOXJ2, FOXO1, FOXO4, HFH1, IRF1, POU3F2, SOX5, SOX9, RSRFC4, S8 and TGIF1 may be related to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury.

Conclusions

(1) CDC5, FAC1, FOXO4, HFH1, IRF1 and TGIF1 may be key transcription factor genes. (2)Transcription factors involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury may become prospective targets for diagnosis and treatment of DN.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-023-04069-8.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathies, Tubulointerstitial injury, Transcription factor, Computational biology, Regulatory network

Background

As a common complication of diabetes, diabetic nephropathy (DN) has become a primary cause of end stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide [1, 2]. It was demonstrated that glomerular lesions play a key role in the early occurrence and development of DN. However, studies in recent years have also shown that tubulointerstitial changes contribute to development and progression of DN, even independently of glomerular lesions [3, 4]. Besides, proximal tubulopathy has been viewed as a key initial factor in the progression of DN [5]. Certain transcription factors (TFs) have been demonstrated to play an important role in these pathologies [6]. Clinical data has showed positive correlations between the transcription factors in tubular epithelial cells and DN progression, such as zinc-finger transcription factor snail homolog 1(Snai1) [7], X-box binding protein 1(XBP1) [8], hypoxia-inducible factor-1α(HIF-1α) [9], and nuclear factor of activated T cells 1(NFATc1) [10]. With in vivo studies, myocardin-related transcription factor A (MRTF-A) can promote transcription of type I and II collagen in an epigenetic manner [11]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) has been reported to mediate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular injury in a murine model of type 1 diabetes [12, 13]. Yin Yang 1 (YY1) has been shown to accelerate renal fibrosis in db/db mice by upregulating α-SMA expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [14]. In addition, our previous studies have also demonstrated that Rap1b ameliorates diabetic tubular injury [15], and the inhibition of NFATc1/TRPC6 signaling mitigates diabetic tubulointerstitial inflammation with in vivo and in vitro study [10]. Despite decades of extensive study, the molecular mechanisms underlying diabetic tubulointerstitial injury remain unclear. Thus, it is of great significance to identify key TFs associated with diabetic tubulointerstitial injury, as specific therapeutics can then be developed to target activation of selected TFs.

Recently, bioinformatic methods have been broadly employed to screen differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and transcription factor genes. As research reported, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened out and functional annotation was performed to identify TFs that regulate these DEGs. In this study, a mRNA microarray dataset downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) was used for further analysis. DEGs between renal tubulointerstitial tissues of DN patients and normal controls were selected to predict transcription factor genes. The regulatory network between the top 10 transcription factors and their target DEGs was constructed by Cytoscape software. Possible mechanisms on how these TFs might exert their influence on diabetic tubulointerstitial injury via target DEGs were investigated through Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. The mRNA expression pattern analysis of transcription factor genes as well as correlation analysis between mRNA expression of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium and clinical features of DN was performed using Nephroseq v5 online platform. Taken together, a total of 38 transcription factor genes based on 166 DEGs were identified, which may become potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for diabetic tubulointerstitial injury.

Methods

Microarray data information

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) is a public genomics data repository storing abundant high throughput gene expression data [16]. The series of GSE30122 [17] was downloaded from GEO database which is based on GPL571(Affymetrix Human Genome U133A 2.0 Array) platform. This microarray data includes 24 normal controls and 10 renal tubulointerstitial tissue samples from DN patients.

Data preprocessing and differential expression analysis

The raw data were preprocessed by log2 transformation and Z-score normalization. The expression level of genes with more than one probe was averaged. Based on GEO database, we found 166 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury under DN state. DEGs (adjusted P-value < 0.05 and | log FC (fold change) | > 1) between renal tubulointerstitial tissues of DN patients and healthy controls were screened by limma package [18] in R software. Afterwards, volcano plot of DEGs was drawn by gplots package [19] in R software.

Identification of transcription factor genes and regulatory network construction of top 10 transcription factors

Transcription factor genes (adjusted P-value < 0.05) involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury were selected by UCSC_TFBS (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/) on Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID 6.8, http://david.ncifcrf.gov/). The top 10 TFs were selected based on the number of DEGs associated with each TF. The regulatory network between top 10 transcription factors and their target genes was visualized by Cytoscape software [20] (http://www.cytoscape.org, version 3.7.0) based on the data from UCSC_TFBS.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway analyses

As an online bioinformatics database, Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery [21, 22] provides comprehensive functional annotation information on multiple genes. GO enrichment analysis covers categories of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF) [23]. KEGG is a widely used database in conducting pathway analysis [21]. GO enrichment and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analyses of targeted genes that regulated by identified transcription factors were performed using DAVID online tools. Gene count > 2 and P < 0.05 were set as the cutoff value.

Statistical analysis

mRNA expression pattern [17, 24, 25] of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium in DN patients compared with normal controls was analyzed by Nephroseq v5 online platform (http://v5.nephroseq.org). Also, Pearson correlation analysis between transcription factor genes and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [17, 25], serum creatine level (SCR) [24, 25], proteinuria [25], body weight [25] and body mass index (BMI) in renal tubulointerstitium in DN patients was performed. Insignificant results are not shown. Data were checked for compliance with the normal distribution by Shapiro–Wilk test and were expressed as the means ± SDs. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed using unpaired the student’s t test. A two-tailed value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Screening of DEGs involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury

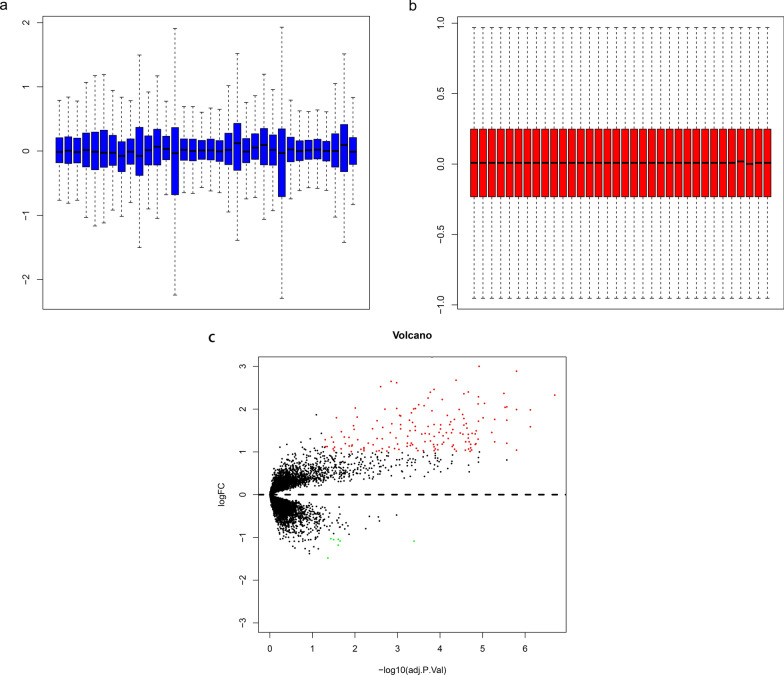

To identify DEGs related to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury, the mRNA expression microarray (GSE30122) was downloaded from GEO. After normalization of the raw microarray data (Fig. 1a and b), 166 DEGs associated with diabetic tubulointerstitial lesions were identified using limma package as shown in the volcano plot (Fig. 1c). Among them, 159 genes were upregulated and 7 genes were downregulated.

Fig. 1.

Box plot of normalized data and volcano plot analysis. a, b Box plot of normalized data from 34 samples. c Volcano plot analysis of DEGs. Red dots represent upregulated genes and green dots represent downregulated genes

Identification of transcription factor genes and regulatory network construction of top 10 transcription factors

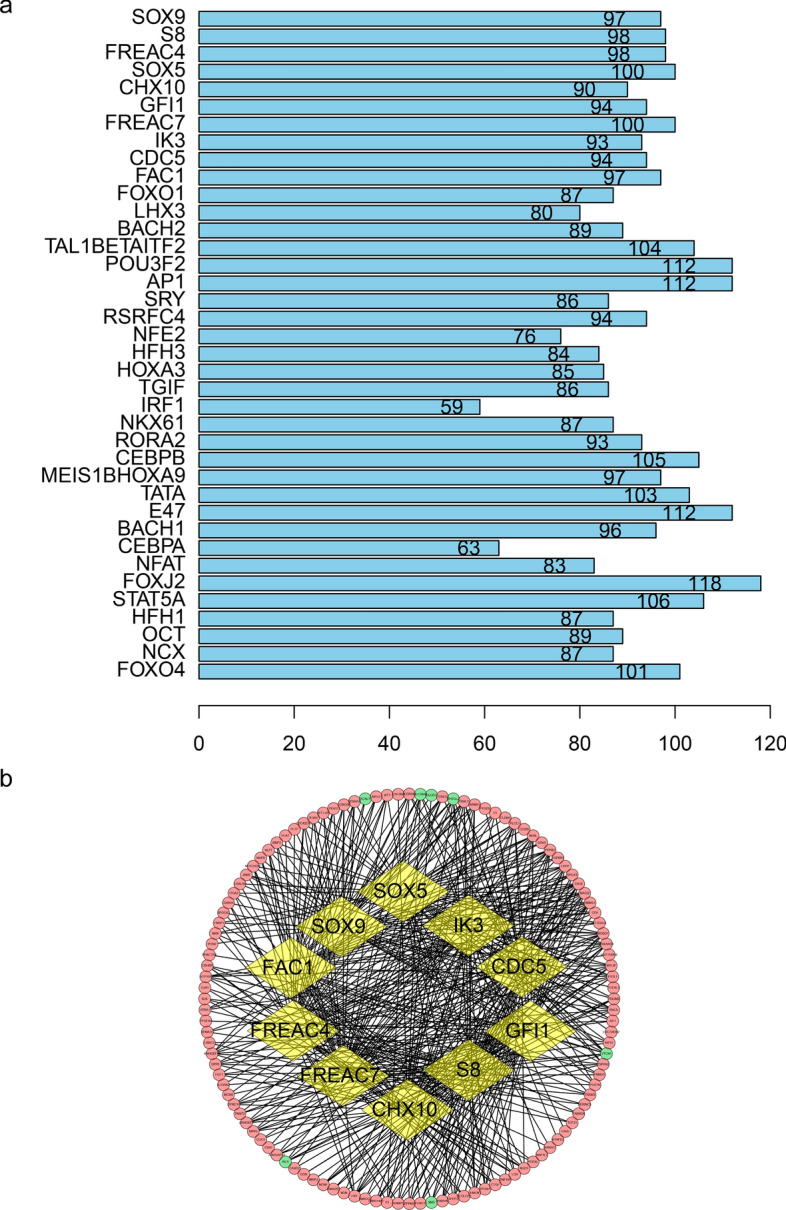

To determine transcription factor genes related to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury, UCSC_TFBS online tool on DAVID was employed to identify transcription factor genes that regulate DEGs. As shown in Fig. 2a, a total of 38 transcription factor genes were indicated to be involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury. Based on the number of DEGs associated with each TF, the top 10 transcription factors and their target DEGs were applied to create the regulatory network via Cytoscape software. The regulatory network consisted of 500 interactions between 10 transcription factors and 116 DEGs (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Transcription factor genes identified by UCSC_TFBS and network construction of top 10 transcription factors. a Bar plot of 38 transcription factor genes. Numbers in the bar represent the amount of DEGs modulated by corresponding transcription factors. b Regulatory network of top 10 transcription factors. Yellow circles represent transcription factors. Red and green circles represent upregulated and downregulated DEGs respectively

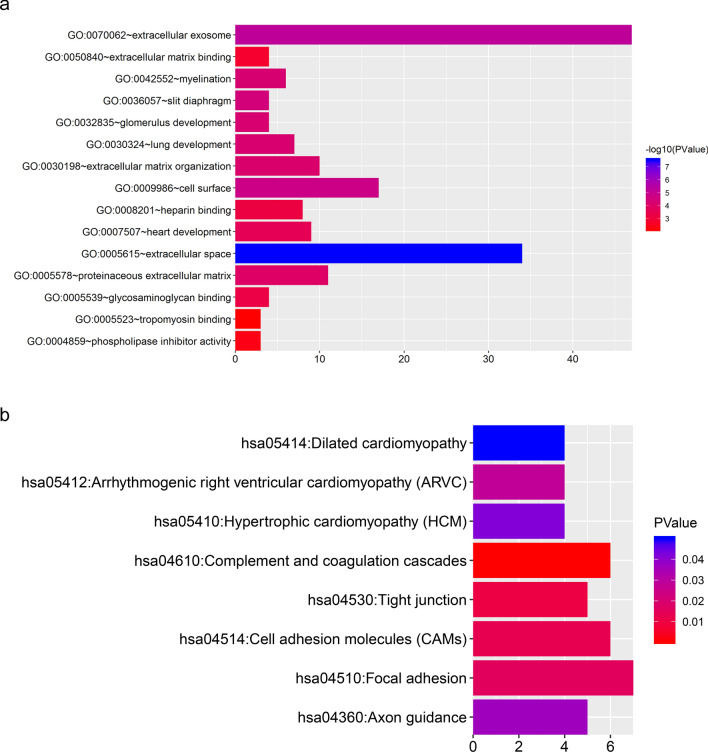

GO enrichment analysis of targeted DEGs

To investigate biological roles of DEGs modulated by 38 transcription factors, GO enrichment analysis was conducted via DAVID. Myelination (P < 0.001), glomerulus development (P < 0.001), lung development (P < 0.001), extracellular matrix organization (P < 0.001) and heart development (P < 0.001) were the top5 significant enrichment of biological process (Fig. 3a). Extracellular space (P < 0.001), extracellular exosome (P < 0.001), cell surface (P < 0.001), slit diaphragm (P < 0.001) and proteinaceous extracellular matrix (P < 0.001) were the top5 significant enrichment of cell component (Fig. 3a). Glycosaminoglycan binding (P < 0.001), heparin binding (P < 0.001), extracellular matrix binding (P = 0.001), phospholipase inhibitor activity (P = 0.004) and tropomyosin binding (P = 0.006) were the top5 significant enrichment of molecular function (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses of DEGs modulated by identified transcription factors. a GO enrichment analysis for targeted DEGs. b KEGG pathway analysis for targeted DEGs. GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

KEGG pathway analysis of targeted DEGs

To explore the signaling pathways of DEGs modulated by identified transcription factors, KEGG pathway analysis was performed via DAVID. Figure 3b showed that these DEGs were primarily enriched in complement and coagulation cascades (P < 0.001), tight junction (P = 0.010) and cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) (P = 0.012).

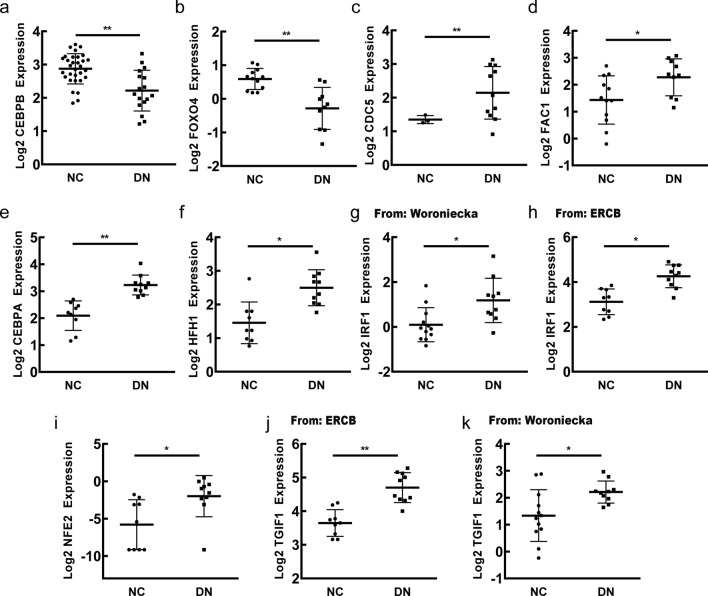

The mRNA expression pattern of transcription factor genes in diabetic renal tubulointerstitium

To find out the mRNA expression pattern of selected transcription factor genes, relevant analysis was performed by Nephroseq v5 online platform. The results demonstrated that the mRNA expression of CDC5, CEBPA, FAC1, HFH1, IRF1, NFE2 and TGIF1 increased in renal tubulointerstitium of DN patients compared with normal controls while that of CEBPB and FOXO4 decreased in renal tubulointerstitium of DN patients compared with normal controls (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The mRNA expression pattern of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium of DN patients compared with normal controls. a, b The decreased mRNA expression of CEBPB, FOXO4 in DN patients compared with normal controls. c–k The increased mRNA expression of CDC5, FAC1, CEBPA, HFH1, IRF1, NFE2, TGIF1 in DN patients compared with normal controls. NC: normal control; DN: diabetic nephropathy. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

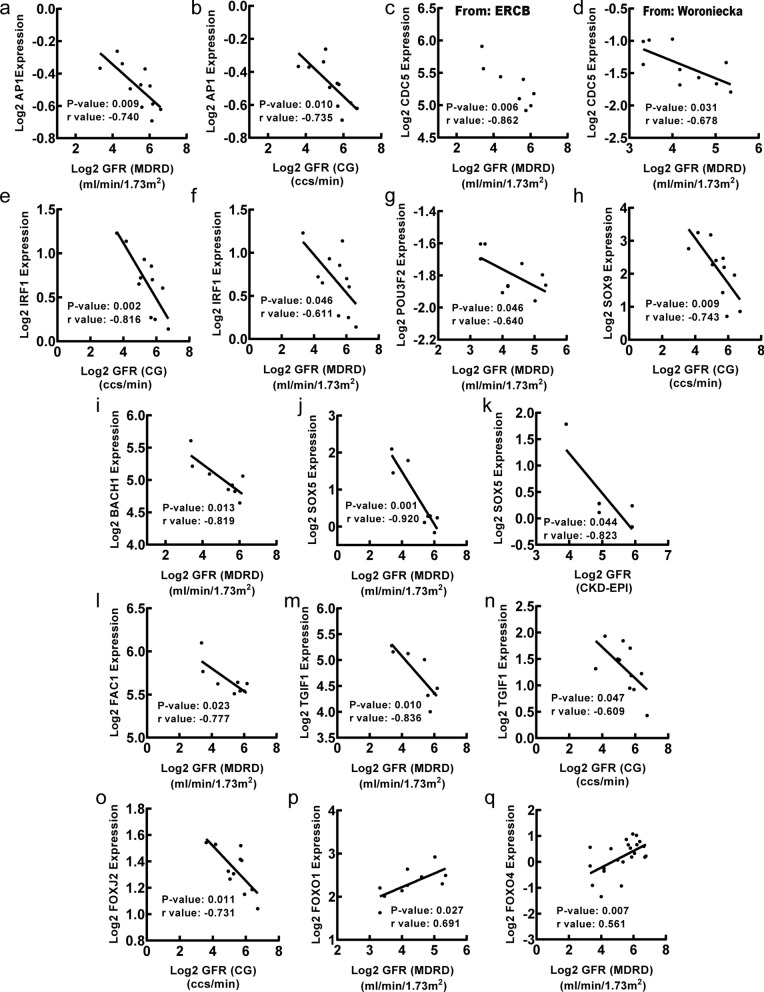

Association between mRNA expression of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium and clinical features of DN

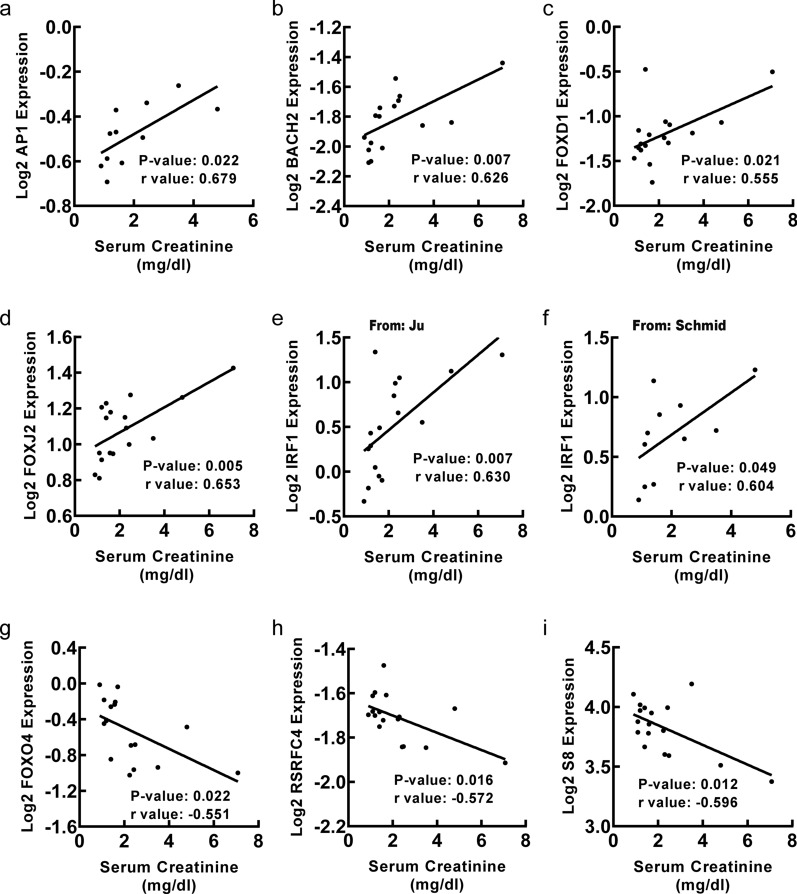

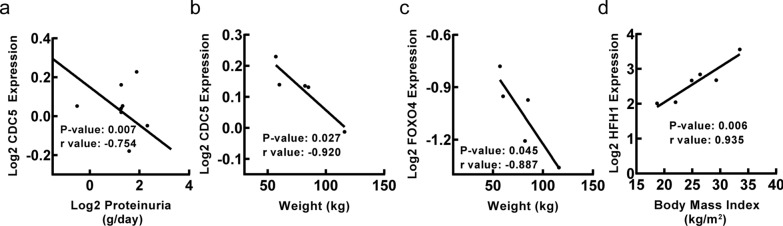

To explore clinical significance of identified transcription factors in DN, correlation analysis between transcription factor genes and clinical features of DN was conducted by Nephroseq v5 online tool. Firstly, the results showed that mRNA expression of AP1, BACH1, CDC5, FAC1, FOXJ2, IRF1, POU3F2, SOX5, SOX9 and TGIF1 in renal tubulointerstitium reversely correlated with GFR in DN patients (Fig. 5), suggesting that those transcription factor genes may contribute to the progression of DN. Meanwhile, the mRNA expression of FOXO1 and FOXO4 in renal tubulointerstitium positively correlated with GFR in DN patients (Fig. 5), indicating that the two transcription factor genes may play a renoprotective role in DN. In this study, MDRD, CG or CKD-EPI GFR were used for further correlation analysis of TFs with GFR as they were used to calculate GFR based on different populations and calculation formulas. The primary data was obtained from different studies, which used different GFR calculation formulas including MDRD, CG and CKD-EPI. Secondly, the mRNA expression of AP1, BACH2, FOXD1, FOXJ2 and IRF1 in renal tubulointerstitium positively correlated with SCR in DN patients (Fig. 6), suggesting that those transcription factor genes may promote the progression of DN. Besides, the mRNA expression of FOXO4, RSRFC4 and S8 in renal tubulointerstitium negatively correlated with SCR in DN patients (Fig. 6), indicating that the three transcription factor genes may have renoprotective roles in DN. Thirdly, the mRNA expression of CDC5 in renal tubulointerstitium negatively correlated with proteinuria in DN patients (Fig. 7a). Besides, the mRNA expression of CDC5 and FOXO4 in renal tubulointerstitium negatively correlated with weight of DN patients (Fig. 7b, c). Moreover, the mRNA expression of HFH1 in renal tubulointerstitium positively correlated with body mass index in DN patients (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between mRNA expression of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium and GFR in DN patients. a–o The mRNA expression of AP1 (p = 0.009, r = − 0.740; p = 0.010, r = − 0.735), CDC5(from ERCB: p = 0.006, r = − 0.862; from Woroniecka: p = 0.031, r = − 0.678), IRF1 (p = 0.002, r = − 0.816; p = 0.046, r = − 0.611 ), POU3F2 (p = 0.046, r = − 0.640), SOX9 (p = 0.009, r = − 0.743), BACH1 (p = 0.013, r = − 0.819), SOX5 (p = 0.001, r = − 0.920; p = 0.044, r = − 0.823), FAC1 (p = 0.023, r = − 0.777), TGIF1 (p = 0.010, r = − 0.836; p = 0.047, r = − 0.609), FOXJ2 (p = 0.011, r = − 0.731) negatively correlated with GFR. p, q The mRNA expression of FOXO1 (p = 0.027, r = 0.691), FOXO4 (p = 0.007, r = 0.561) positively correlated with GFR. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. GFR: glomerular filtration rate; MDRD: modification of diet in renal disease; CG: Cockcroft Gault

Fig. 6.

Correlation between mRNA expression of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium and SCR in DN patients. a–f The mRNA expression of AP1 (p = 0.022, r = 0.679), BACH2 (p = 0.007, r = 0.626), FOXD1 (p = 0.021, r = 0.555), FOXJ2 (p = 0.005, r = 0.653), IRF1 (from Ju: p = 0.007, r = 0.630; from Schmid: p = 0.049, r = 0.604) positively correlated with SCR. g–i The mRNA expression of FOXO4(p = 0.022, r = − 0.551), RSRFC4 (p = 0.016, r = − 0.572), S8 (p = 0.012, r = − 0.596) negatively correlated with SCR. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SCR, serum creatine

Fig. 7.

Correlation between mRNA expression of transcription factor genes in renal tubulointerstitium and proteinuria, weight and body mass index in DN patients. a The mRNA expression of CDC5 negatively correlated with proteinuria (p = 0.007, r = − 0.754). b The mRNA expression of CDC5 negatively correlated with weight (p = 0.027, r = − 0.920). c The mRNA expression of FOXO4 negatively correlated with weight (p = 0.045, r = − 0.887). d The mRNA expression of HFH1 positively correlated with body mass index (p = 0.006, r = 0.935). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Discussion

Diabetic nephropathy is a globally leading cause of chronic renal failure. In recent years, diabetic tubulopathy has been recognized to have crucial roles in the development of DN [3, 26]. Transcription factors regulate—turn on and off—genes via binding to specific DNA sequences, which are vital for various pathophysiological processes [27]. Such TFs also play key roles in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury as TGF-β [28], HIF-1 [29] and MRTF-A [11]. Although vigorous efforts have been made, the underlying mechanisms of diabetic tubulointerstitial injury still await clarification. The widespread use of microarray technology and bioinformatic methods enables us to identify key transcription factor genes involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury, which might yield additional interventional strategies for DN.

A total of 38 transcription factor genes based on 166 DEGs between renal tubulointerstitial tissues of DN patients and normal controls were predicted via UCSC_TFBS. Certain genes such as CEBP and NFAT were observed significantly changed, which corresponded with our earlier researches [10, 30]. As reported, downregulated CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBP-β) in db/db mice was proven to induce activated SOCS3/STAT3 signaling pathway, and consequently promote diabetic tubulointerstitial inflammation [30]. Nuclear factor of activated T cell 1 (NFATc1) accompanied with TRPC6 formed a feedback loop to participate in diabetic tubulointerstitial inflammation [10]. Given these validated TFs, it is suggestive to further identify the core TFs and their dominant mechanism, providing reliable research interests. Unfortunately, several indexes including NLRP3, RIPK3, MCP1, KIM-1 and NGAL, were not shown in our analysis, though they were demonstrated might be used as biomarkers of tubular injury in DN condition [31, 32]. Here, we mainly selected DEGs or TFs whose expression change were greater than 2-fold according to the database. It would be worthy to analyze the correlation between these important genes and tubular injury under hyperglycemia condition with more databases.

The regulatory network showed connections between the top 10 transcription factors and their target DEGs. GO enrichment analysis of targeted DEGs demonstrated that extracellular space, extracellular exosome and cell surface were most significantly enriched. The extracellular space refers to the part of a multicellular organism outside the cells, in which extracellular matrix presents. Diabetic tubulointerstitial fibrosis is characterized by increasing deposition of extracellular matrix in the extracellular space [33]. Besides, particular molecules derived from extracellular exosomes have been suggested to serve as potential diagnostic biomarkers in DN including AQP2 [34], AQP5 [34] and let-7c-5p [35]. The loss of molecular binding events between cell surfaces is also involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial fibrosis [36]. Also, GO enrichment analysis displayed that glycosaminoglycan binding and phospholipase inhibitor activity was both significantly enriched, indicating that mitochondria should inevitably become dysfunctional. Correspondingly, increasing data have suggested that persistent mitochondrial dysfunction has a role in the early stages and progression of renal diseases, including diabetic nephropathy [37–40]. Our previous study has also revealed that NRF2/PINK-mediated mitochondrial quality control exerts important effects in diabetic tubular damage and mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorates this tubular injury [41]. KEGG pathway analysis of targeted DEGs showed that these DEGs were primarily mapped to complement and coagulation cascades, tight junction and cell adhesion molecules. Existing findings support that activated complement system and procoagulant events contribute to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury [42–45]. An in vitro study conducted in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell line has demonstrated that exposure to high glucose can result in a significant perturbation of the tight junction associated tubular barrier [46]. Tight junctions (TJs) are responsible for adjusting the paracellular transport of solutes and water. They were found to have structural and functional abnormalities in DN condition, impairing the glomeruli, proximal tubules and podocytes [47, 48]. Moreover, cell adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 [49] and ICAM-1 [50] have been reported to play an important role in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury. Together, all these publications are consistent with our results.

Among 38 transcription factor genes, CDC5, FAC1, FOXO4, HFH1, IRF1 and TGIF1 were not only differentially expressed between renal tubulointerstitial tissues of DN patients and normal controls, but also closely related to clinical features of DN. Thus, these 6 candidates may be key transcription factor genes involved in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury. Forkhead box O4 (FOXO4) is a transcription factor involved in the modulation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1A) [51], cell cycle [52] and insulin signaling pathway [53]. It has already been recognized as a key transcriptional regulator in DN [54]. Intriguingly, a previous study demonstrated that the induction of FOXO4 was responsible for podocyte apoptosis mediated by advanced glycation end products [55]. However, the results of our study suggested that FOXO4 may have a renoprotective role in diabetic tubulointerstitial injury, raising the possibility that one transcription factor may exert a distinctive effect on different parts of the kidney.

Yet, there is still limited report on the association between other 5 transcription factor genes (CDC5, FAC1, HFH1, IRF1 and TGIF1) and diabetic nephropathy. Cell division cycle 5 like (CDC5) is a DNA-binding protein that regulates cell cycle [56]. FAC1, also named as bromodomain PHD finger transcription factor (BPTF), is a transcription factor gene related to chromatin remodeling [57]. HFH1 (Forkhead box Q1, FOXQ1) has been reported to mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition in various human cancers [58]. Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) is a transcription factor regulating multiple cellular processes, especially for the modulation of interferon (IFN) and IFN-inducible genes [59]. TGFB induced factor homeobox 1 (TGIF1) can act as a transcriptional corepressor of SMAD2 [60] and suppress the function of retinoid X (RXR) receptor [61]. Notably, recent studies have discovered increased TGIF1 can promote the activation of TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling pathway, thus contributing to diabetic inflammation and fibrosis in the kidney [62], as well as chronic renal fibrosis [63].

Taken together, translation factors work in many ways to have an impact on diabetic tubulointerstitial injury, despite the mechanisms underlying its role need further exploration. Some limitations in this study should be noted. There are not enough samples from patients and not enough data has not been collected at present. In addition, all the above predicted results should be confirmed by laboratory data. More data and further analysis are encouraged to elucidate those meaningful translational factors and their target genes involved in the inflammatory and fibrotic pathogenesis of DN. With the application of advanced nanomaterials, kidney-targeted therapeutic approaches have rapidly developed [64]. Combining studies on those key molecules and their underlying mechanisms based on bioinformatics analysis, this novelty treatment that precisely intervenes on the target becomes promising.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study was intended to search for key transcription factor genes related to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury. A total of 38 transcription factor genes based on 166 DEGs were screened by UCSC_TFBS, which may provide new insights into pathogenesis and potential druggable targets for DN. Of them, CDC5, FAC1, FOXO4, HFH1, IRF1 and TGIF1 may be key transcription factor genes. Further experimental studies are needed to confirm our results and delineate biofunctions of those TFs related to diabetic tubulointerstitial injury.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DN

Diabetic nephropathy

- ESRD

End stage renal disease

- TFs

Transcription factors

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- UCSC_TFBS

A category provided by DAVID

- DAVID

The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- SCR

Serum creatine level

Author contributions

JL and GD designed the research and drafted the manuscript. JL, WY and SZ acquired data, analyzed data and performed statistical analysis. FL, YP, SL, YL and LX revised manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants (No. 82170744) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (No. 2020zzts286). The funders had a role in the data collection, analysis and writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from GEO GSE30122 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). Source code is available at the “Supplementary Information” section (Additional file 1).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Central South University, the Second Xiangya hospital approved the study and waived the need of informed written/verbal consent for this anonymous study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jialu Liu and Guangzhong Duan are co-first authors

References

- 1.Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, Shi Y, He X, Zhou Z, Li Y, Yeung RO, Wang J, Matsushita K, et al. Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:905–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbertson DT, Liu J, Xue JL, Louis TA, Solid CA, Ebben JP, Collins AJ. Projecting the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2015. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3736–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeni L, Norden AGW, Cancarini G, Unwin RJ. A more tubulocentric view of diabetic kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2017;30:701–17. doi: 10.1007/s40620-017-0423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1819–34. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert RE. Proximal tubulopathy: prime mover and key therapeutic target in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2017;66:791–800. doi: 10.2337/db16-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez AP, Sharma K. Transcription factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e13. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohnuki K, Umezono T, Abe M, Kobayashi T, Kato M, Miyauchi M, Yamamoto N, Kimura M, Toyoda M, Suzuki D. Expression of transcription factor Snai1 and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in progressive nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2012;25:233–9. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.8449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindenmeyer MT, Rastaldi MP, Ikehata M, Neusser MA, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Schlondorff D. Proteinuria and hyperglycemia induce endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2225–36. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagar SK, Zhang C, Guo Q, Yi R, Lin T. Role of expression of endothelin-1 and angiotensin-II and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in the kidney tissues of patients with diabetic nephropathy. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24:959–64. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.118098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S, Wang H, Liu Y, Yang W, Liu J, Han Y, Liu Y, Liu F, Sun L, Xiao L. Tacrolimus ameliorates tubulointerstitial inflammation in diabetic nephropathy via inhibiting the NFATc1/TRPC6 pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:9810–24. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu H, Wu X, Qin H, Tian W, Chen J, Sun L, Fang M, Xu Y. Myocardin-related transcription factor a epigenetically regulates renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1648–60. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nayak BK, Shanmugasundaram K, Friedrichs WE, Cavaglierii RC, Patel M, Barnes J, Block K. HIF-1 mediates renal fibrosis in OVE26 type 1 diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2016;65:1387–97. doi: 10.2337/db15-0519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang N, Zhao H, Han Y, Li L, Xiong S, Zeng L, Xiao Y, Wei L, Xiong X, Gao P, et al. HIF-1alpha ameliorates tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy via HO-1-mediated control of mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Prolif. 2020;53:e12909. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang T, Shu F, Yang H, Heng C, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Qian X, Du L, Zhu X, Lu Q, Yin X. YY1: a novel therapeutic target for diabetic nephropathy orchestrated renal fibrosis. Metabolism. 2019;96:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao L, Zhu X, Yang S, Liu F, Zhou Z, Zhan M, Xie P, Zhang D, Li J, Song P, et al. Rap1 ameliorates renal tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2014;63:1366–80. doi: 10.2337/db13-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH, Sherman PM, Holko M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D, Thomas DB, Pullman JM, Susztak K. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2011;60:2354–69. doi: 10.2337/db10-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warnes GR, Bolker B, Bonebakker L, Gentleman R, Huber W, Liaw A, Lumley T, Maechler M, Magnusson A, Moeller S et al. gplots: various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data. R Package Version 2 2009.

- 20.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ju W, Nair V, Smith S, Zhu L, Shedden K, Song PXK, Mariani LH, Eichinger FH, Berthier CC, Randolph A, et al. Tissue transcriptome-driven identification of epidermal growth factor as a chronic kidney disease biomarker. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:316ra193. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid H, Boucherot A, Yasuda Y, Henger A, Brunner B, Eichinger F, Nitsche A, Kiss E, Bleich M, Grone HJ, et al. Modular activation of nuclear factor-kappab transcriptional programs in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55:2993–3003. doi: 10.2337/db06-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slyne J, Slattery C, McMorrow T, Ryan MP. New developments concerning the proximal tubule in diabetic nephropathy: in vitro models and mechanisms. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(Suppl 4):iv60–67. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, Taipale J, Hughes TR, Weirauch MT. The human transcription factors. Cell. 2018;172:650–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hills CE, Squires PE. The role of TGF-beta and epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takiyama Y, Harumi T, Watanabe J, Fujita Y, Honjo J, Shimizu N, Makino Y, Haneda M. Tubular injury in a rat model of type 2 diabetes is prevented by metformin: a possible role of HIF-1alpha expression and oxygen metabolism. Diabetes. 2011;60:981–92. doi: 10.2337/db10-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang WX, Liu Y, Zhang SM, Wang HF, Liu YF, Liu JL, Li XH, Zeng MR, Han YZ, Liu FY, et al. Epac activation ameliorates tubulointerstitial inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43:659–71. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00689-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Horany HE, Abd-Ellatif RN, Watany M, Hafez YM, Okda HI. NLRP3 expression and urinary HSP72 in relation to biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy patients. IUBMB Life. 2017;69:623–30. doi: 10.1002/iub.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satirapoj B. Tubulointerstitial Biomarkers for diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:2852398. doi: 10.1155/2018/2852398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hills CE, Siamantouras E, Smith SW, Cockwell P, Liu KK, Squires PE. TGFbeta modulates cell-to-cell communication in early epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Diabetologia. 2012;55:812–24. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossi L, Nicoletti MC, Carmosino M, Mastrofrancesco L, Di Franco A, Indrio F, Lella R, Laviola L, Giorgino F, Svelto M, et al. Urinary excretion of kidney aquaporins as possible diagnostic biomarker of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:4360357. doi: 10.1155/2017/4360357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Yang S, Qiao R, Zhang J. Potential value of urinary exosome-derived let-7c-5p in the diagnosis and progression of type II Diabetic Nephropathy. Clin Lab. 2018;64:709–18. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2018.171031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siamantouras E, Hills CE, Squires PE, Liu KK. Quantifying cellular mechanics and adhesion in renal tubular injury using single cell force spectroscopy. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:1013–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.12.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhargava P, Schnellmann RG. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:629–46. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hallan S, Sharma K. The role of Mitochondria in Diabetic kidney disease. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:61. doi: 10.1007/s11892-016-0748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei PZ, Szeto CC. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;496:108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saxena S, Mathur A, Kakkar P. Critical role of mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired mitophagy in diabetic nephropathy. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:19223–36. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao L, Xu X, Zhang F, Wang M, Xu Y, Tang D, Wang J, Qin Y, Liu Y, Tang C, et al. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorated tubular injury mediated by mitophagy in diabetic kidney disease via Nrf2/PINK1. Redox Biol. 2017;11:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morita Y, Ikeguchi H, Nakamura J, Hotta N, Yuzawa Y, Matsuo S. Complement activation products in the urine from proteinuric patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:700–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V114700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly KJ, Liu Y, Zhang J, Dominguez JH. Renal C3 complement component: feed forward to diabetic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:48–56. doi: 10.1159/000371426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng JM, Ren XG, Jiang ZH, Chen DJ, Zhao WJ, Li LJ. Lectin-induced renal local complement activation is involved in tubular interstitial injury in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;482:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sommeijer DW, Florquin S, Hoedemaker I, Timmerman JJ, Reitsma PH, Ten Cate H. Renal tissue factor expression is increased in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;101:e86–94. doi: 10.1159/000086646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mongelli-Sabino BM, Canuto LP, Collares-Buzato CB. Acute and chronic exposure to high levels of glucose modulates tight junction-associated epithelial barrier function in a renal tubular cell line. Life Sci. 2017;188:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kielgast F, Schmidt H, Braubach P, Winkelmann VE, Thompson KE, Frick M, Dietl P, Wittekindt OH. Glucocorticoids regulate tight Junction Permeability of Lung Epithelia by modulating Claudin 8. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:707–17. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0071OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eftekhari A, Vahed SZ, Kavetskyy T, Rameshrad M, Jafari S, Chodari L, Hosseiniyan SM, Derakhshankhah H, Ahmadian E, Ardalan M. Cell junction proteins: crossing the glomerular filtration barrier in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;148:475–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koga M, Otsuki M, Kubo M, Hashimoto J, Kasayama S. Relationship between circulating vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1998;15:661–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199808)15:8<661::AID-DIA645>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chow FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Ozols E, Atkins RC, Tesch GH. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 deficiency is protective against nephropathy in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1711–22. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang TT, Lasky LA. The forkhead transcription factor FOXO4 induces the down-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha by a von Hippel-Lindau protein-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30125–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–7. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kops GJ, de Ruiter ND, De Vries-Smits AM, Powell DR, Bos JL, Burgering BM. Direct control of the Forkhead transcription factor AFX by protein kinase B. Nature. 1999;398:630–4. doi: 10.1038/19328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hong Q, Zhang L, Das B, Li Z, Liu B, Cai G, Chen X, Chuang PY, He JC, Lee K. Increased podocyte Sirtuin-1 function attenuates diabetic kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2018;93:1330–43. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chuang PY, Yu Q, Fang W, Uribarri J, He JC. Advanced glycation endproducts induce podocyte apoptosis by activation of the FOXO4 transcription factor. Kidney Int. 2007;72:965–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lei XH, Shen X, Xu XQ, Bernstein HS. Human Cdc5, a regulator of mitotic entry, can act as a site-specific DNA binding protein. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 24):4523–4531. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JH, Kim MS, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. BPTF, a chromatin remodeling-related gene, exhibits frameshift mutations in gastric and colorectal cancers. APMIS. 2016;124:425–7. doi: 10.1111/apm.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qiao Y, Jiang X, Lee ST, Karuturi RK, Hooi SC, Yu Q. FOXQ1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3076–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oshima S, Nakamura T, Namiki S, Okada E, Tsuchiya K, Okamoto R, Yamazaki M, Yokota T, Aida M, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2 distinctively up-regulate gene expression and production of interleukin-7 in human intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6298–310. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6298-6310.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wotton D, Knoepfler PS, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Massague J. The smad transcriptional corepressor TGIF recruits mSin3. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:457–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertolino E, Reimund B, Wildt-Perinic D, Clerc RG. A novel homeobox protein which recognizes a TGT core and functionally interferes with a retinoid-responsive motif. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31178–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang L, Wang Q, Ju J, Li Y, Cai Q, Hao L, Zhou Y. Magnoflorine ameliorates inflammation and fibrosis in rats with diabetic nephropathy by mediating the Stability of lysine-specific demethylase 3A. Front Physiol. 2020;11:580406. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.580406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding H, Xu Y, Jiang N. Upregulation of miR-101a suppresses chronic renal fibrosis by regulating KDM3A via blockade of the YAP-TGF-beta-smad signaling pathway. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:1276–89. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eftekhari A, Maleki Dizaj S, Ahmadian E, Przekora A, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM, Ardalan M, Zununi Vahed S, Valiyeva M, Mehraliyeva S, Khalilov R, Hasanzadeh M. Application of advanced nanomaterials for kidney failure treatment and regeneration. Materials. 2021;14:2939. doi: 10.3390/ma14112939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from GEO GSE30122 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). Source code is available at the “Supplementary Information” section (Additional file 1).