Abstract

Synthetic gene circuits that precisely control human cell function could expand the capabilities of gene and cell-based therapies. However, platforms for developing circuits in primary human cells that drive robust functional changes in vivo and have compositions suitable for clinical use are lacking. Here, we develop synthetic transcriptional regulators that are compact and based largely on human-derived proteins (synZiFTRs). As a proof of principle, we engineer gene switches and circuits that allow precise, user-defined control over therapeutically-relevant genes in primary T cells using orthogonal, FDA-approved small molecule inducers. Our circuits can instruct T cells to sequentially activate multiple cellular programs, such as proliferation and antitumor activity, to drive synergistic therapeutic responses. This platform should accelerate development and clinical translation of synthetic gene circuits in diverse human cell types and contexts.

Cells use networks of interacting molecules to integrate and process signals into appropriate output responses. Synthetic biology aims to manipulate this process and drive the development of new biomedical technologies and therapies (1–3). For example, programming human cells with synthetic circuits that allow them to execute desired cellular functions in response to defined stimuli could enable new capabilities for gene and cell-based therapies. One prominent example is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell immunotherapy, in which patientderived T cells are redirected to attack tumors by genetically modifying them to express artificial antigen-targeting receptors. CAR-T cell therapy has shown clinical promise in treating certain cancers, leading to several approved cancer therapies (4). However, engineered T cells also display adverse, sometimes fatal side effects stemming from off-target toxicity and overactivation (4–6). Moreover, CAR-T cells have significantly limited clinical efficacy for most solid tumors (7), and the corresponding push to create more potent therapies has simultaneously heightened the risk of severe adverse side effects (8, 9).

The challenge of balancing efficacy and toxicity to realize the full potential of these emerging therapeutic modalities has motivated recent efforts in mammalian synthetic biology aimed at developing methods for precise, temporal, and context-specific control of therapeutic cellular activity (10–14). Unfortunately, developing even simple synthetic circuits in primary human cells is challenging, particularly circuits capable of the strong outputs necessary to drive functional changes in vivo. Those that do exist harbor molecular components or formulations that are not suitable for clinical use. As such, existing methods are unlikely to scale to allow control over the different aspects of cell behavior – e.g., localization, anti-tumor activity, persistence – that collectively influence and dictate therapeutic outcomes (15–20). Overall, we lack versatile, scalable, and clinically-viable gene circuit engineering platforms with which to reliably engineer relevant human cell types to address therapeutic challenges.

An established method for controlling mammalian cell behavior is by engineering transcriptional regulation. Efforts to control gene expression have primarily focused on a widely-used set of artificial transcriptional regulators, derived from microbial transcription factors (TetR, Gal4) and viral activators (VP16, VP64), that exhibit robust functionality across many cell types and, in the case of TetR-based systems, are induced by a small molecule antibiotic (21, 22). However, these regulators are limited in number thus restricting the number of genes that can be controlled in a circuit, they are challenging to reprogram for new regulatory relationships, and their non-mammalian origins and chemical inducers present clinical hurdles for therapies that depend on persistent expression (23, 24). Programmable DNA-targeting elements, such as the bacterial CRISPR-Cas9 system, have provided new methods for gene expression modulation and synthetic circuit design (25–27). However, the large size of Cas9 constrains what can be designed and delivered to primary human cells, and the high immunogenic potential of Cas9 is also well-documented (28, 29).

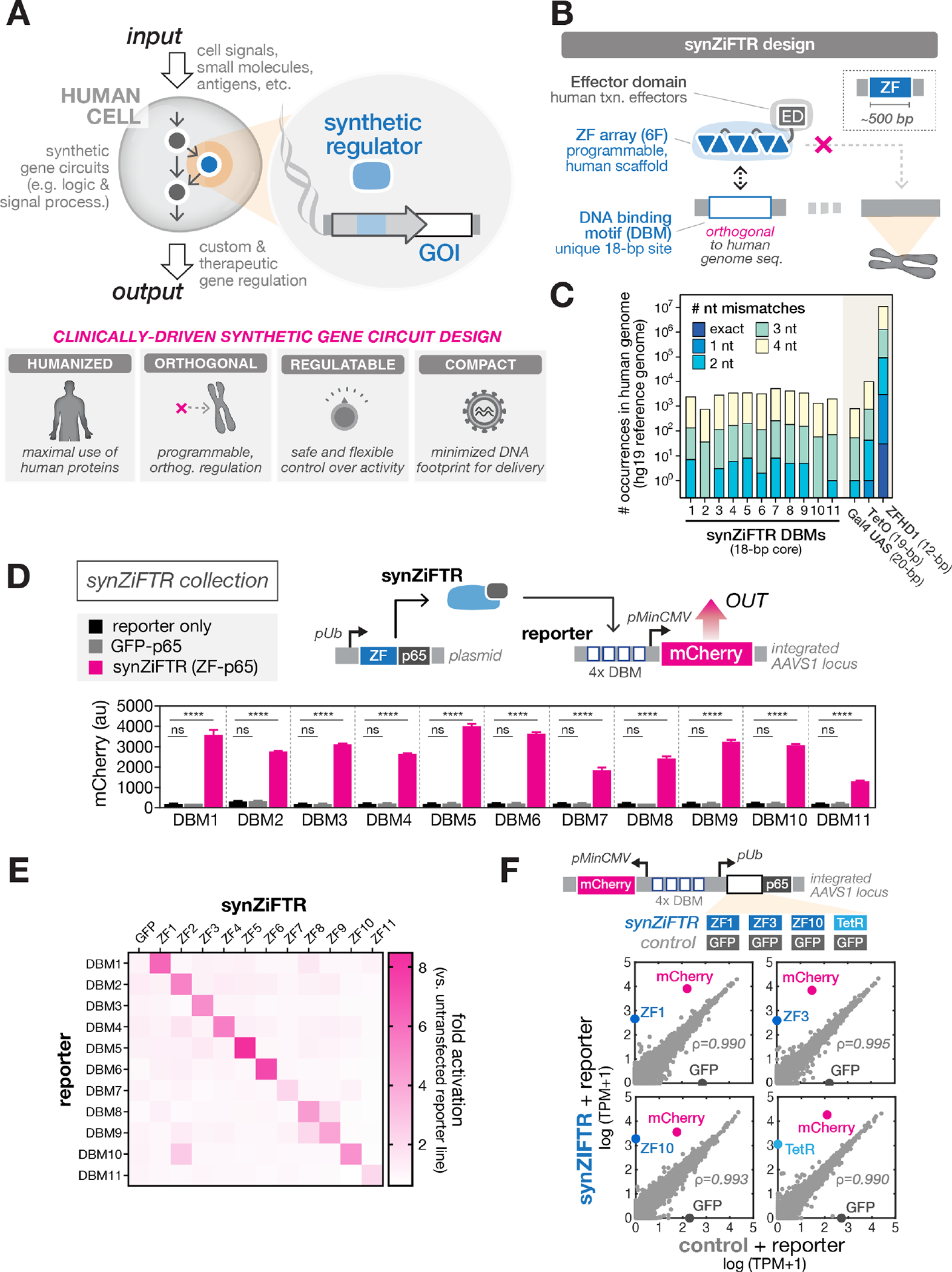

We outlined four basic principles for a toolkit that could support the rapid and scalable construction of gene expression circuits that are effective and potentially suitable for clinical use (Fig. 1A): (1) Humanized – prioritize the use of human-derived proteins, when possible, to minimize immunogenic potential. (2) Orthogonal – in order to minimize cross-talk with native regulation. (3) Safe regulation – gene regulatory activity that can be easily and safely controlled. (4) Compact – minimized genetic footprints for efficient delivery into primary human cells and tissues. As a building block for our toolkit of synthetic regulators, we focused on Cys2His2 zinc fingers (ZFs), which balance clinical favorability and programmability. ZFs are small (~30 amino acid) domains that bind to ~3 bps of DNA (30). They are the most prevalent DNA binding domain (DBD) found in human transcription factors (TFs) (31), suggesting they represent a flexible solution to DNA recognition with low immunogenicity potential. Indeed, a first-generation artificial ZF-based regulatory system showed multi-year functionality in non-human primates with no apparent immunogenicity (32). Moreover, individual ZF domains can be reprogrammed to recognize new motifs and concatenated to generate proteins capable of specifically targeting longer DNA sequences (33–36). While ZF engineering has been applied to generate endogenous genome editing and manipulation tools, we sought to create a collection of composable synthetic regulators with genome-orthogonal specificities.

Fig. 1. Clinically-driven design of compact, humanized, synthetic gene regulators (synZiFTRs) for mammalian cell engineering.

(A) Synthetic gene circuits are used to convert diverse input signals into desired gene expression outputs in order to precisely control human cell function (top). Criteria for clinically-driven gene circuit design framework (bottom).

(B) SynZiFTR design. SynZiFTRs have a modular design based on compact, human-derived protein domains. An engineered ZF array mediates interactions with a unique, human genome-orthogonal DNA-binding motif (DBM), and human-derived effector domains (EDs) are used to modulate transcriptional activity.

(C) Prevalence of synZiFTR recognition motifs in the human genome. Occurrences of exact and increasingly mismatched sequences for each synZiFTR DBM and response elements from common artificial regulators (Gal4 UAS, TetO, ZFHD1).

(D) SynZiFTRs strongly activate gene expression at corresponding response promoters. Response element vectors were stably-integrated into HEK293FT cells to generate reporter lines for each synZiFTR (ZF-p65 fusion). SynZiFTR (or control) expression vectors were transfected into corresponding reporter lines, and mCherry was measured by flow cytometry after 2 days. Bars represent mean values for three measurements ± SD. Statistics represent one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparisons; ns: not significant; ****: p < 0.0001. pUb, Ubiquitin C promoter; pMinCMV, minimal CMV promoter; p65, aa361-551.

(E) SynZiFTRs have mutually orthogonal regulatory specificities. Each synZiFTR expression vector was transfected into every reporter line, and mCherry was measured by flow cytometry after 2 days. Fold activation levels represent mean values for three biological replicates.

(F) SynZiFTRs exhibit specific and orthogonal transcriptional regulation profiles in human cells. Correlation of transcriptomes from RNA-sequencing measurements of HEK293FT cells stably expressing synZiFTR or TetR-p65 versus a GFP-p65 control. Points represent individual transcript levels normalized to TPM, transcripts per kilobase million, averaged between two technical replicates. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for native (grey) transcripts. See Fig. S3 for extended analyses.

We leveraged an archive of engineered two-finger (2F) units that explicitly account for context-dependent effects between adjacent fingers (34, 36). By linking 2F units using flexible ‘disrupted’ linkers (37), it is possible to construct functional six-finger (6F) arrays capable of recognizing 18 bps, a length for which a random sequence has a high probability of being unique in the human genome (Fig. 1B, S1B). We prioritized 6-bp subsites that are underrepresented in the human genome and selected arrays to minimize identity with the human genome; this yielded 11 targetable synthetic DNA-binding motifs (DBMs) (Fig. 1C, S1C–D, Methods). We next sought to engineer synthetic Zinc Finger Transcription Regulators (synZiFTRs) capable of strong and specific regulation at these synthetic cis-elements. We fused ZFs predicted to bind each DBM to the human p65 activation domain and screened for the most active candidates in HEK293FT reporter lines (Fig. S2A–C). Selected synZiFTRs strongly activate corresponding, but not non-cognate, reporters (Fig. 1D–E). To evaluate their impact on native regulation, we performed RNA-sequencing analysis on cell lines expressing three representative synZiFTRs (ZF1, ZF3, ZF10), benchmarking these against a TetR-based activator. SynZiFTR regulation profiles are highly specific, minimally affecting native transcript profiles, and compare favorably with the profile of TetR (Fig. 1F, S3). These results establish a collection of compact, humanized, and genome-orthogonal transcriptional regulators (synZiFTRs) optimized for gene expression control and synthetic circuit design in human cells.

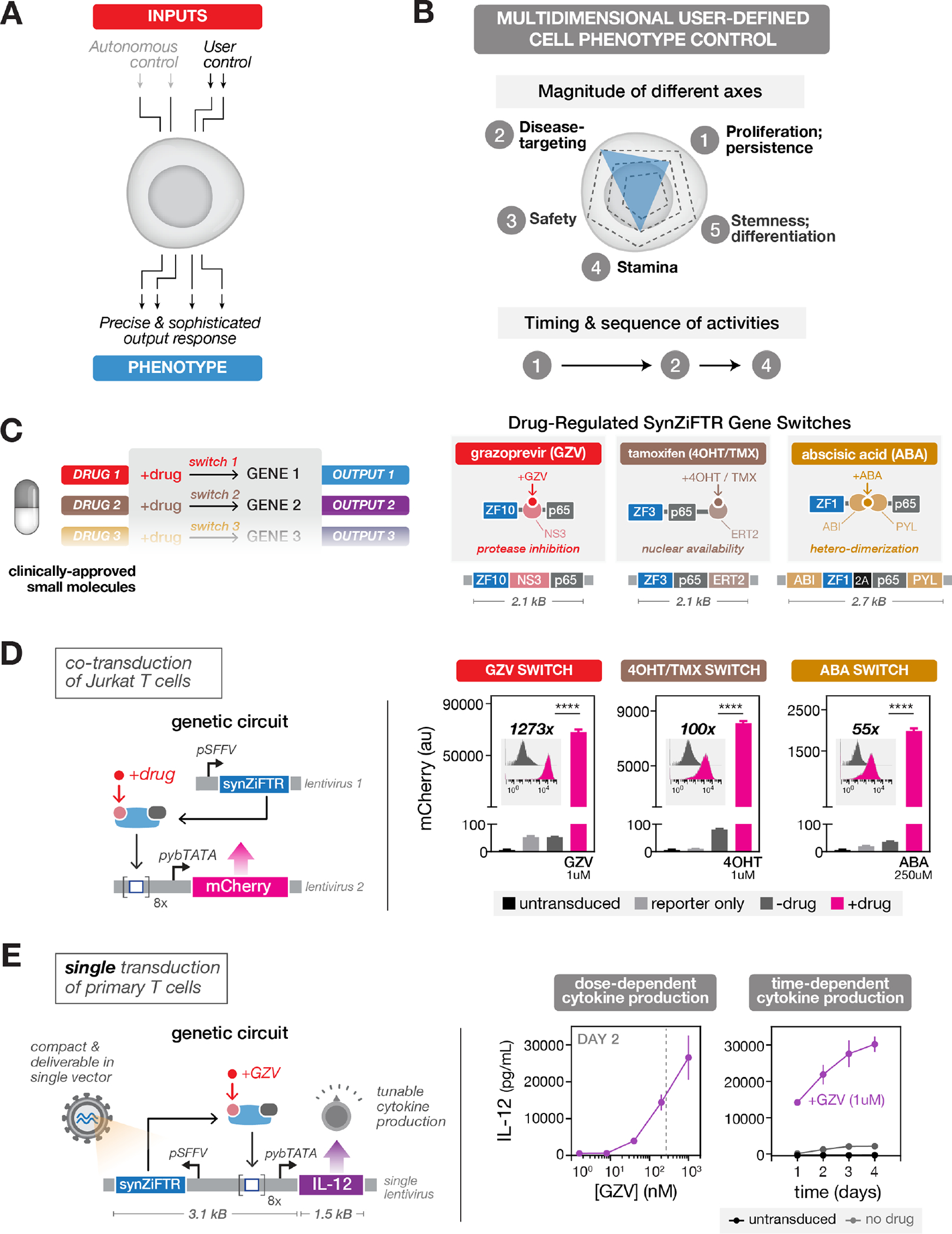

To achieve the goal of regulatable synZiFTR circuits, we considered methods for enacting gene regulation control in response to defined input stimuli (Fig. 2A). We focused our attention on user-defined regulation, which in principle allows total control over timing, level, and context over which a therapeutic gene is expressed. Moreover, regulated circuits with user-defined control over multiple genes could be used to instruct engineered cells to dynamically activate different, complementary cellular programs to achieve optimal phenotypes (Fig. 2B). One promising approach for user-defined control is using small molecules, which could be administered systemically or locally to switch ON a gene circuit and/or activate production of a therapeutic gene product. We prioritized compounds that are already clinically-approved or otherwise known to have favorable safety profiles. This nominated three classes of small molecules that can regulate synZiFTR activity through distinct mechanisms, offering the potential for up to three orthogonal channels of gene expression control (Fig. 2C, S4A): 1) Grazoprevir (GZV), an FDA-approved antiviral drug from a family of protease-inhibiting compounds, which has an exceptional safety profile and is commonly taken at a high dose (100 mg/day) for up to 12 weeks (38). The addition of GZV stabilizes synZiFTRs incorporating the NS3 self-cleaving protease domain (from hepatitis C virus (HCV)), driving gene transcription (39, 40). 2) 4-Hydroxytamoxifen / tamoxifen (4OHT/TMX), the FDA-approved and widely prescribed breast cancer drug that selectively modulates the nuclear availability of molecules fused to sensitized variants of the human estrogen receptor, ERT2 (41, 42). 3) Abscisic acid (ABA), a plant hormone naturally present in many plant-based foods and classified as non-toxic to humans, which mediates conditional binding of complementary protein fragments (ABI and PYL) from the ABA stress response pathway to reconstitute an active synZiFTR (43). Note that there are trade-offs in priorities: for example, allowing incorporation of minimal non-humanderived domains into the synZiFTR scaffold allows the use of drugs that minimally interfere with native cellular machinery (e.g., GZV), or of inexpensive non-toxic molecules (e.g., ABA).

Fig. 2. SynZiFTR gene switches allow precise, user-defined control over gene expression in human cells using clinically-approved small molecules.

(A) Two forms of cellular control: circuits can be designed to enact cell-autonomous phenotype control (e.g., via recognition of disease-relevant cell surface molecules) or external, user-defined phenotype control (e.g., via administration of small molecules).

(B) User-defined control over different axes of a cellular phenotype (top) and the chronology of cellular activities (bottom).

(C) Implementing multi-gene user control with orthogonal gene switches that are regulated by clinically-viable small molecules (right). Design of three distinct synZiFTR gene switches that are controlled by orthogonal small molecules: grazoprevir (GZV), 4-hydroxytamoxifen / tamoxifen (4OHT / TMX), and abscisic acid (ABA) (right). NS3, hepatitis C virus NS3 protease domain; ERT2, human estrogen receptor T2 mutant domain; ABI, ABA-insensitive 1 domain (aa 126–423); PYL, PYR1-like 1 domain (aa 33–209).

(D) Optimized synZiFTR switches enable strong inducible gene expression in Jurkat T cells. Jurkat T cells were co-transduced with reporter and synZiFTR expression lentiviral vectors in an equal ratio. mCherry fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry 4 days following induction by small molecules at indicated concentrations. Bars represent mean values for three measurements ± SD. Statistics represent two-tailed Student’s t test; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001. Histograms show absolute levels and mean fold activation for one representative measurement (insets). pSFFV, Spleen Focus-Forming Virus promoter; pybTATA, synthetic YB_TATA promoter.

(E) Compact, single lentivirus-encoded synZiFTR switches enable titratable control over the expression of therapeutically-relevant genes in primary human immune cells. Human primary T cells were transduced with a single lentiviral vector encoding GZV-regulated IL-12 (see Methods). IL-12 production was measured by ELISA at specified time points following induction (with or without 1 uM GZV). Points represent mean values for three measurements ± SD. Dashed line, estimate of the Cmax for traditional clinical dosing of GZV.

We constructed GZV-, 4OHT/TMX- and ABA-inducible gene switches using distinct ZFs (ZF1, ZF3, ZF10) and tested their performance in Jurkat T cells (Fig. S4A,B). The three systems exhibited titratable control of reporter output, minimal leakage relative to reporter-only cells, strong dynamic ranges, no cross-reactivity, and returned to basal levels upon removal of inducer (Fig. S4C,D). Due to the orthogonality of the inducers and the modularity of the synZiFTR architecture, more elaborate gene switches can be readily designed for more complex forms of temporal control, including multiplexed ON/OFF switching (Fig. S5).

In order to optimize synZiFTR circuit dynamics, we screened arrangements of DBM arrays and minimal promoters to identify combinations that reduced basal expression and improved dynamic range (44) (Fig. S6A). This produced optimized designs for GZV-, 4OHT-, and ABA-inducible synZiFTR circuits, encodable in either dual or single lentiviral vectors (Figs. 2D, S6B), that can enable dose- and time-dependent control of therapeutically-relevant payloads, such as the immunomodulatory factor IL-12, in therapeutically-relevant primary human cells (Fig. 2E).

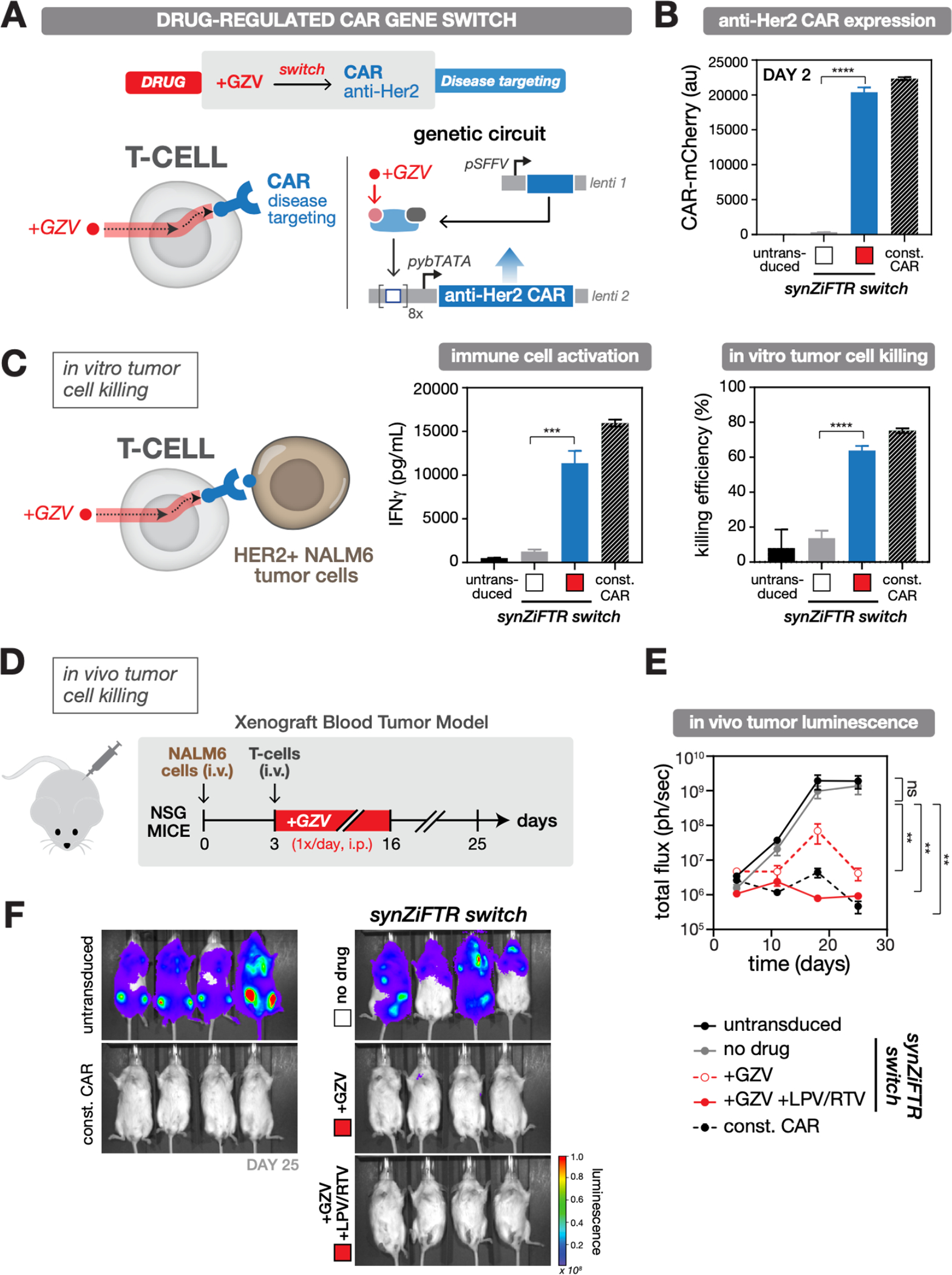

Do synZiFTR circuits enable in vivo, clinically-relevant gene expression outputs? To investigate this, we turned to CAR T cell therapy as a proof-of-principle, initially choosing to develop a gene switch to control CAR expression and activate tumor-targeting functionality (Fig. 3A). This modality allows rapid evaluation of whether small molecule-dependent synZiFTR activity is sufficient to elicit functional (disease-modifying) changes in vitro and in vivo, and recent work has established the value of controlling timing of activation of CAR signaling for improved CAR T cell fitness and outcomes (45–47). We developed a GZV-regulated anti-Her2 CAR (Fig. 3A). Her2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is overexpressed in many tumors, including a small subset of leukemias (48). We previously demonstrated this anti-Her2 CAR in a xenograft liquid tumor model, thus providing a convenient platform to evaluate the efficacy of our synZiFTR circuits (49). Our gene switch exhibited GZV-dependent CAR expression in primary human T cells, expressing to comparable levels to that of a constitutively-expressed CAR, and with minimal output in the absence of inducer (Fig. 3B). When co-cultured with Her2-overexpressing (HER2+) NALM6 leukemia cells (Fig. S7C), synZiFTR-regulated CAR cells were capable of drug-dependent activation and efficient tumor cell killing in vitro (Fig. 3C). These synZiFTR circuits are easily reconfigurable. By swapping the anti-Her2 CAR with an anti-CD19 CAR, we reproduced these in vitro results for a second CAR payload, demonstrating the generalizability of our platform (Fig. S7).

Fig. 3. SynZiFTR gene circuit for drug-regulated, post-delivery control over CAR expression and T-cell killing in vivo.

(A) Design of the synZiFTR gene circuit for GZV-dependent control over anti-Her2 CAR expression and tumor cell targeting and killing.

(B) GZV-regulated CAR expression in primary T cells. Human primary T cells were co-transduced with equal ratios of lentiviral vectors encoding the synZiFTR CAR gene circuit (see Methods). Expression of anti-Her2 CAR-mCherry was measured by flow cytometry two days following induction (with or without 1 uM GZV). White box, uninduced; red box, GZV induced. Const. CAR, constitutively expressed (pSFFV-CAR). Bars represent mean values for three measurements ± SD. Statistics represent two-tailed Student’s t test; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001.

(C) GZV-regulated immune cell activation and tumor cell killing in vitro. SynZiFTR-controlled CAR T cells (pre-induced with or without 1 uM GZV for 2 days) were co-cultured with HER2+ NALM6 target leukemia cells in a 1:1 ratio (left). IFNγ secretion from activated immune cells was measured by ELISA (center) and tumor cell killing by flow cytometry (right), one day following co-culturing. White box, uninduced; red box, GZV induced.

(D) Testing in vivo efficacy of synZiFTR-regulated CAR T cells using a xenograft tumor mouse model. Timeline of in vivo experiment, in which NSG mice were injected i.v. with luciferase-labeled HER2+ NALM6 cells to establish tumor xenografts, followed by treatment with T cells. GZV was formulated alone or in combination with LPV/RTV and administered i.p. daily over 14 days. Mice were imaged weekly on days 4, 11, 18, 25 to monitor tumor growth via luciferase activity. GZV, 25 mg/kg. LPV/RTV, 10 mg/kg.

(E) Tumor burden over time, quantified as the total flux (photons/sec) from the luciferase activity of each mouse using IVIS imaging. Points represent mean values ± SEM (n=4 mice per condition). Statistics represent two-tailed, ratio paired Student’s t test; ns: not significant; **: p < 0.01.

(F) IVIS imaging of mouse groups treated with (1) untransduced cells, (2) synZiFTR-regulated CAR T cells, (3) synZiFTR-regulated CAR T cells with GZV, (4) synZiFTR-regulated CAR T cells with GZV+LPV/RTV, (4) constitutive CAR cells. (n=4 mice per condition).

Next, we tested the in vivo efficacy of synZiFTR-regulated CAR T cells using a simple xenograft blood tumor model (49) (Fig. 3D, Methods). Mice receiving synZiFTR-controlled CAR T cells and treated with GZV, either alone or in combination with lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/RTV), a cocktail known to increase drug bioavailability (50), were able to clear the tumor, while those not treated with inducer developed high tumor burdens as determined by IVIS imaging of luciferase-expressing HER2+ tumors (Fig. 3E–F, Fig. S8A,B). While both inducer conditions led to tumor eradication, clearance rates were faster with the cocktail, on par with the constitutive CAR positive control and consistent with the ability of LPV/RTV to increase GZV bioavailability (Fig. 3E, S8C). These results demonstrate that synZiFTR circuits can be used to program drug-dependent, post-delivery control over T cell anti-tumor activity in vivo.

In addition to controlling CAR-mediated tumor targeting, synZiFTRs are also suited to control the expression of other proteins, such as IL-2 or IL-12, immunomodulatory cytokines that have long been considered to be potential anti-cancer agents due to their role in stimulating and regulating immune responses (51, 52). Equipping engineered immune cells to produce cytokines is a compelling approach to improve their antitumor efficacy. However, high doses of IL-2 or IL-12 are known to cause severe side effects. Regulated expression represents a safer approach to leverage the potential of these factors for augmenting immune cell efficacy. Moreover, as a T cell growth factor, user-regulated IL-2 production could serve as an exciting basis for achieving on-demand cellular proliferation.

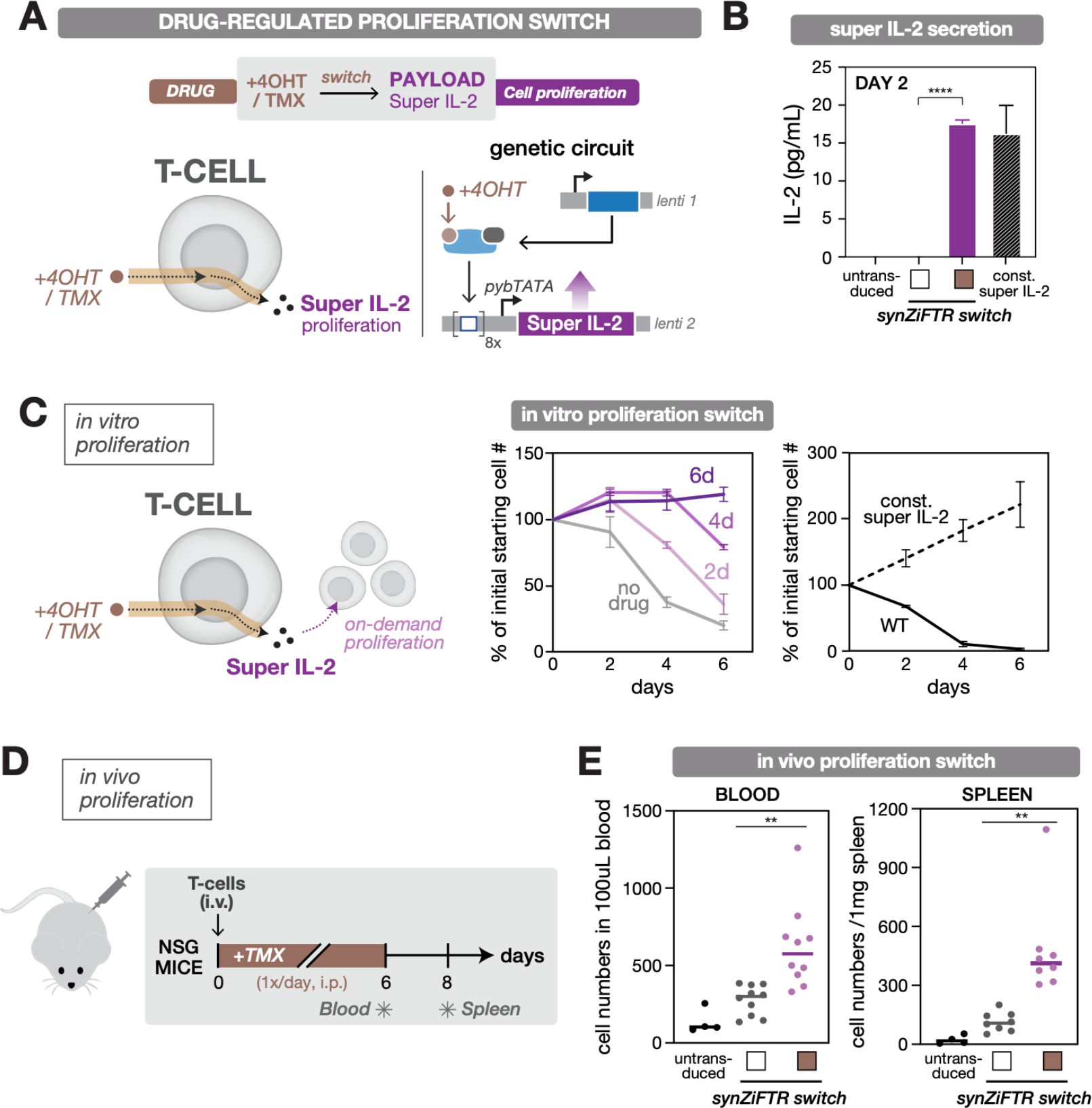

To establish a proliferation gene switch, we used a tamoxifen (TMX)-inducible synZiFTR to regulate expression of super IL-2, an enhanced version of IL-2 with stronger affinity to CD122 (53) (Fig. 4A). Our gene switch exhibited 4OHT/TMX-dependent super IL-2 production in vitro in primary T cells, once again to comparable levels to that of the constitutive control and with minimal output in the absence of inducer (Fig. 4B). Primary T cells require exogenous IL-2 to remain viable over long periods of time in culture, which provides a simple way to test the performance of the proliferation switch. We cultured equal numbers of engineered cells in media lacking IL-2 and induced them with 4OHT for different durations. Cells harboring the inducible super IL-2 switch exhibited duration-dependent proliferation (Fig. 4C). The synthetic system also exhibits dose-dependent control over super IL-2 production and cellular proliferation (Fig. S9). Finally, to demonstrate the ability of the proliferation switch to control T cell growth in vivo, we injected engineered T cells into NSG mice intravenously and administered TMX daily via intraperitoneal injection for six days. We observed enhanced T cells levels in the peripheral blood (day 6) and spleen (day 8) in mice receiving engineered T cells and exposed to TMX compared to mice receiving engineered T cells without TMX or untransduced cells only (Fig. 4D,E). These results establish a synZiFTR gene switch for TMX-dependent control over super IL-2 production and in vivo, on-demand cell expansion.

Fig. 4. SynZiFTR gene circuit for drug-regulated, on-demand immune cell proliferation.

(A) Design of the synZiFTR gene circuit for 4OHT/TMX-dependent control over super IL-2 expression and cell proliferation.

(B) 4OHT-regulated super IL-2 production in primary T cells. Human primary T cells were co-transduced with equal ratios of lentiviral vectors encoding the synZiFTR-regulated proliferation gene circuit (see Methods). Secretion of super IL-2 was measured by ELISA (for IL-2) two days following induction (with or without 1 uM 4OHT). White box, uninduced; brown box, 4OHT induced. Const. super IL-2, constitutively expressed (pSFFV-super IL-2). Bars represent mean values for three measurements ± SD. Statistics represent two-tailed Student’s t-test; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001.

(C) 4OHT-regulated T cell proliferation in vitro. SynZiFTR-regulated primary T cells were cultured in IL-2-free media, induced with 4OHT (1 uM) for different durations, and live-cell numbers were quantified by flow cytometry at indicated days (center). Untransduced (WT) and constitutively expressing (const. super IL-2) T cells were cultured and quantified similarly (right). Lines represent mean values for three measurements ± SD.

(D) Testing in vivo efficacy of the drug-regulated, on-demand proliferation switch. Timeline of in vivo experiment, in which NSG mice were injected i.v. with primary T cells followed by daily treatment with TMX over six days. The blood and spleen were individually sampled on days 6 and 8, respectively, to quantify the change in T cell numbers. TMX, 75mg/kg.

(E) TMX-regulated T cell expansion in vivo. Human T cell numbers from blood and spleen samples were quantified by flow cytometry by gating for hCD3+ / mCD45- cells, following staining for human CD3 (hCD3) and mouse CD45 (mCD45). Lines indicate the mean value; dots represent each mouse. Blood sample (n=10), and spleen sample (n=8). White box, uninduced; brown box, TMX induced. Statistics represent two-tailed Student’s t-test; **: p < 0.01.

Thus the synZiFTR platform enables development of compact gene switches that are effective for dose- and time-dependent control of therapeutically-relevant genes both in vitro and in vivo, setting the stage for genetic circuits that allow simultaneous and independent multi-gene control in the same cell. To investigate whether synZiFTRs can regulate two orthogonal gene programs, we transduced primary human T cells with vectors encoding GZV-regulated anti-Her2 CAR and TMX-regulated super IL-2 switches (Fig. 5A). Next, we induced cells with different combinations of the two drugs and used distinguishable reporters to measure gene activation for each channel. Engineered cells exhibited the desired orthogonal patterns of gene activation (Fig. S10A); following induction with both drugs, >14% of cells simultaneously expressed high levels of both genes (Fig. 5A). Thus, our full dual-switch genetic circuit was delivered to a significant population of cells and both switches are functional and orthogonal.

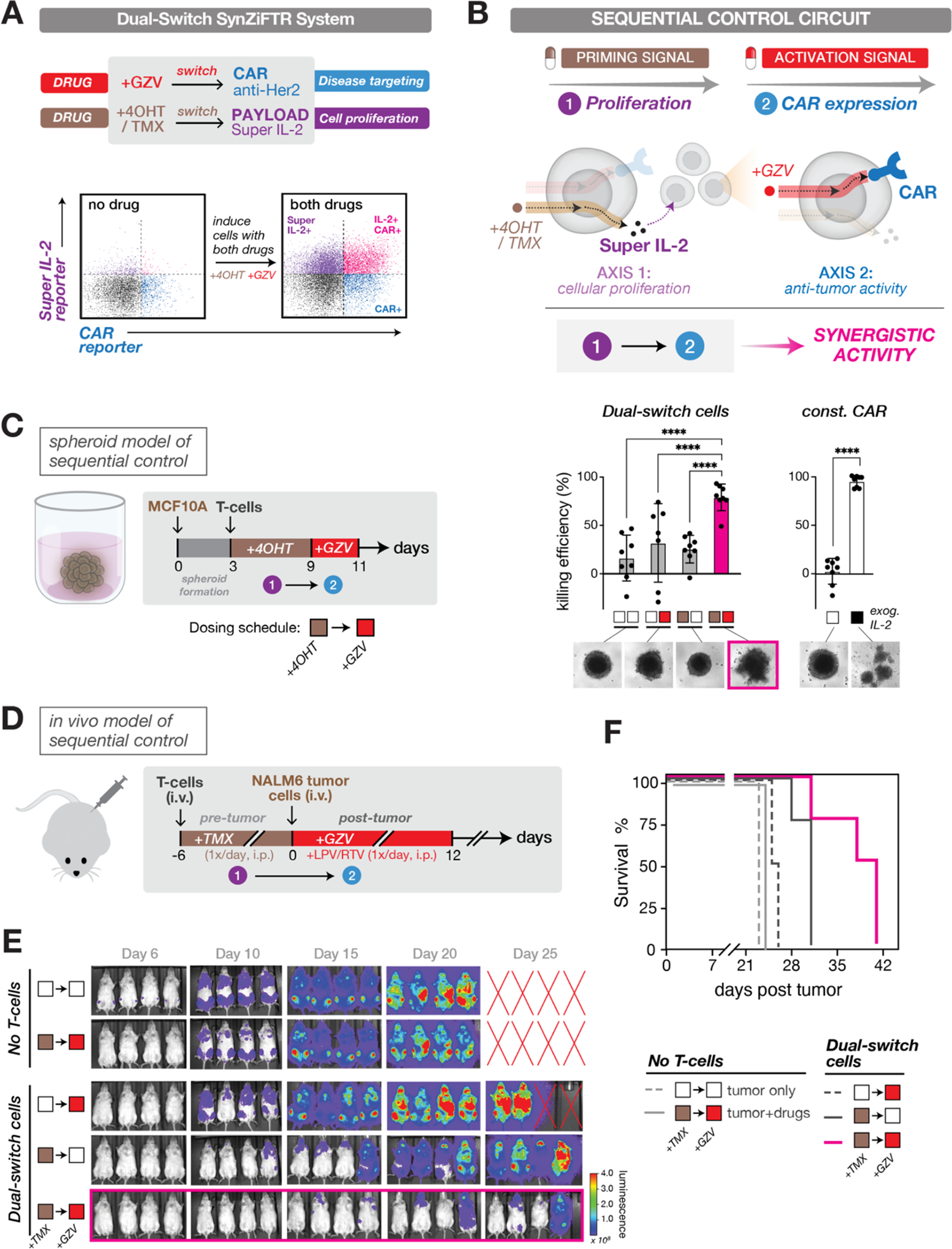

Fig. 5. Enacting sequential control of immune cell function to drive synergistic in vivo responses.

(A) A dual-switch synZiFTR system for orthogonal, drug-inducible control over anti-Her2 CAR and super IL-2 expression (top). Assessing circuit activation in primary T cells following induction with both drugs (1uM GZV and 1uM 4OHT) (bottom). Distinguishable reporters were used to measure gene activation for each channel with or without 1-day of induction: mCherry-fused anti-Her2 CAR and bicistronic super IL-2 reporter (super IL-2-2A-EGFP). See also Fig. S10.

(B) Schema for sequential control in which a priming signal (4OHT/TMX drug) is used to induce cellular proliferation of a small starting population of dual-switch cells via super IL-2 expression, followed by an activation signal (GZV drug) to induce cytotoxic activation via CAR expression.

(C) An in vitro spheroid model used to demonstrate the synergistic efficacy of sequential control over T cell proliferation (+4OHT) and activation (+GZV) behavior (left). T cell killing efficiency was measured by luminescence signals from spheroid, and representative morphology of spheroids at the endpoint is shown below (right). White box, uninduced; brown box, 4OHT induced; red box, GZV induced. Bars represent mean values ± SD. Const. CAR, constitutive CAR cells.

(D) An in vivo model used to demonstrate the synergistic efficacy of sequential control over T cell proliferation (+TMX) and activation (+GZV) behavior. Timeline of in vivo experiment in which NSG mice were injected i.v. with dual-switch T cells (1×106 cells) six days ahead of the tumor challenge. TMX was administered i.p. daily over six days to activate the proliferation switch prior to tumor challenge. HER2+/Luciferase+ NALM6 cells (1×106 cells) were injected i.v. six days after injection of T cells and the GZV-regulated CAR was switched ON by administering GZV in combination with LPV/RTV daily i.p. over 12 days. TMX, 75mg/kg. GZV, 25mg/kg. LPV/RTV, 10mg/kg.

(E) IVIS imaging of tumor burden over time of mouse groups treated with (1) tumor alone (no T cells), (2) tumor with both drugs in sequence (TMX ® GZV), (3) dual-switch T cells treated with GZV alone during the time window of d0 ® d12 (∅ ® GZV), (4) dual-switch T cells treated with TMX alone during the time window of d-6 ® d0 (TMX ® ∅), and (5) dual-switch T cells treated with both drugs in sequence (TMX ® GZV).

(F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the various treatment groups for the in vivo sequential model study. (n=4 mice per condition). White box, uninduced; brown box, TMX induced; red box, GZV induced.

A capability afforded by dual-switch circuits is the possibility of enacting sequential control of cell function (Fig. 5B). Modulating cell functions based on the timing and sequential order of signaling events is a critical regulatory mechanism in living systems (54, 55), including in the immune system (56). Motivated by natural systems, engineered sequential control could dictate when and in what order distinct cellular programs are activated, potentially unlocking underexplored dimensions of cell therapy function. As a proof-of-principle, we envisioned a simple scenario in which a small starting population of engineered cells is first “primed” with one signal (4OHT/TMX: to drive cellular expansion and poise cells for activation) and subsequently “activated” by a second signal (GZV: to induce CAR expression and initiate anti-tumor activity) (Fig. 5B). We then set out to develop models to test that we can establish sequential control of immune cells in vitro and in vivo.

We began with a 2D in vitro model that builds upon the cell proliferation experiments of Fig. 4. We cultured synZiFTR-controlled T cells for 6 days either with or without the priming signal (4OHT), then activated CAR expression (GZV) and subsequently challenged with HER2+ NALM6 tumor cells 1 day following activation, comparing these cells to constitutive CAR expressing cells (Fig. S10B). Only cells harboring the dual-switch circuit exhibited expansion of cell numbers when induced with 4OHT (Fig. S10C). Correspondingly, we found that only dual-switch cells that were 4OHT-primed and subsequently GZV-activated (4OHT → GZV) were capable of efficient tumor cell killing, when challenged with fast-growing tumor cells one week (day 7) after initiating the culture (Fig. S10D). Encouraged by these results, we sought to establish a 3D spheroid model of sequential control (Fig. 5C). Spheroids are an imperfect but useful model of in vivo solid tumors, sharing notable morphological and behavioral similarities, including the development of oxygen and nutrient gradients, formation of a necrotic/apoptotic central core, and recapitulation of 3D cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions (57). We designed a 3D spheroid, based on HER2+ MCF10A breast mammary epithelial cells, which we used to test whether sequential control can drive functional changes to the spheroid targets (Fig. 5C, Methods). Spheroids co-cultured with dual-switch cells and receiving the sequential 4OHT ® GZV dose regiment exhibited synergistic responses, as measured by tumor cell killing and corresponding morphological disruption of spheroids, including loss of their hallmark rounded shape and amorphous cell scattering throughout the well (Fig. 5C). These results provide evidence for engineered sequential control of T cell function in vitro.

Our next goal was to develop an in vivo model of sequential control. To look for conditions where we could evaluate the control circuit, we modulated the infusion timing of constitutive CAR T cells in a NSG mouse leukemia model. Mice received either a pre-infusion (at day −6) or a post-infusion (day 1) of a relatively low number of control constitutive CAR expressing T cells (1×106 cells) (Fig. S11A). At day 0, we injected the mice with HER2+ Nalm6 tumor cells and tracked tumor burden. The pre-infused CAR T cells are less effective at responding to the tumor challenge. The 6-day pre-infusion tumor model offers a window of susceptibility to demonstrate the sequential control circuit. When we tested dual-switch T cells in this mouse model (Fig. 5D), we observed synergistic in vivo activity in reducing tumor burden in mice receiving the engineered T cells and the TMX → GZV dose regiment, relative to other dosing schemes and non-T cell controls (Fig. 5E–F, S11D). Mice that were not pre-conditioned with the TMX stimulus prior to the tumor cell challenge, but were induced to activate CAR expression, were significantly less effective at responding to the challenge, suggesting that the TMX phase was necessary for priming the population. These results provide evidence that we can engineer sequential control of T cell function in vivo using orthogonal FDA-approved drugs as stimuli. They also demonstrate the therapeutic potential of these circuits that can sequentially activate therapeutically-relevant and synergistic genes to prime cells for anti-tumor activity.

In this work, we designed and tested in human cells a suite of clinically-inspired synthetic gene regulators and circuits with demonstrated therapeutic potential. The synZiFTR platform features de novo engineered ZFs that can be used to implement orthogonal and clinically-viable drug-controlled genetic circuits with minimal genetic footprints. Using the platform, we demonstrated new capabilities for user-defined control over therapeutic cell function, including the creation of multi-input/-output circuits that enable sequential control of immune cell function to drive synergistic in vivo activity in reducing tumor burden.

We undertook the design of ZFs due to their hypercompact size, human origins, and demonstrated clinical viability. Moreover, we and others have demonstrated that ZF systems permit tunability at the level of DNA-binding affinity and cooperativity, which is valuable in designing synthetic circuits with tunable and predictive input/output behaviors (58–60). Other programmable DNA-targeting systems employ large proteins from non-human origin, which may pose issues with regards to immunogenicity. Analysis of our core synZiFTR architecture using an established immunogenicity prediction tool confirmed that our ZF peptides have lower predicted immunogenicity scores compared to those of TetR, Gal4, and sp dCas9 (Methods, Fig. S12). However, evaluating the true immunogenic potential of any synthetic system will ultimately require empirical measurements. While the initial synZiFTR platform is based upon ZFs, alternative methods of gene activation may, in the future, complement the platform, such as CRISPR-Cas systems engineered to have reduced size and immunogenic potential (61–63).

We outlined criteria to guide clinically-driven gene circuit design processes. As we demonstrated with our gene switches, developing systems within this framework is a multi-dimensional optimization problem that will require prioritizing specific criteria depending on the application. Our GZV switch favors safe regulation, prioritizing the use of a clinically-approved, pharmacokinetically-favorable drug that does not target native cellular proteins. The TMX switch offers an entirely human-derived option. Overall, we believe our synZiFTR systems offer superior options to existing drug-regulated systems due to the combination of drug safety, efficacy, regulatory orthogonality, and predicted low immunogenicity. In the future, efforts to predict potential immunogenic peptides (Fig. S12), ‘de-immunize’ synZiFTR domains, and perhaps incorporate new human-derived ligand binding domains with biocompatible inducers could provide pathways to clinical translation. Finally, because of the modularity and orthogonality of the synZiFTR architecture, it should be relatively straightforward to incorporate other regulatory domains, including de novo-designed bioactive protein domains (64, 65), and to use synZiFTRs as the basis of constructing cell-autonomous and multi-antigen recognition circuits (11, 12, 66).

The ability to encode temporal patterns using synZiFTR sequential control circuits could unlock an underexplored dimension of cell therapy function. For instance, the type 2 effector response is typically viewed as pro-tumor; however, evidence is accumulating that it can also mediate anti-tumor immunity (67, 68). One possible way to harness the type 2 response could be to activate it following an initial cytotoxic response by CAR T cells. Our synZiFTR platform would be ideally suited to carry out such a complex therapeutic program safely and effectively.

We expect that our synZiFTR platform will translate widely to other clinically-relevant cell types and contexts, enabling the future development of synthetic circuits for gene and cell therapies. While much development remains and many other clinical considerations to address, we hope these tools will begin to transform the rapid advances we are witnessing in mammalian synthetic biology into new solutions for safer, effective, and more powerful next-generation therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Maggie Bobbin for technical assistance with design of zinc finger arrays. We thank C. Bashor, J. Ngo, and members of the Wong and Khalil laboratories for helpful discussions.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH grant R01EB029483 (K.T.R., W.W.W., A.S.K.), DP1 OD006862 (J.K.J), and NSF Grant MCB-1713855 (A.S.K.). D.V.I. acknowledges funding from an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1247312). A.S.K. acknowledges funding from a DARPA Young Faculty Award (D16AP00142), NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (DP2AI131083), and DoD Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship (N00014-20-1-2825).

Footnotes

Competing interests: D.V.I., J.D.S., J.K.J, and A.S.K. are inventors on a patent related to the synZiFTR technology; H.S.L., D.V.I., K.T.R., W.W.W, and A.S.K. have filed patent applications related to drug-regulated synZiFTRs. J.K.J. is a co-inventor on various patents and patent applications that describe gene editing and epigenetic editing technologies. K.T.R. is a co-founder of Arsenal Biosciences, was a founding scientist/consultant and stockholder in Cell Design Labs, now a Gilead Company, and holds stock in Gilead. J.K.J. has, or had during the course of this research, financial interests in several companies developing gene editing technology: Beam Therapeutics, Blink Therapeutics, Chroma Medicine, Editas Medicine, EpiLogic Therapeutics, Excelsior Genomics, Hera Biolabs, Monitor Biotechnologies, Nvelop Therapeutics (f/k/a ETx, Inc.), Pairwise Plants, Poseida Therapeutics, SeQure Dx, Inc., and Verve Therapeutics. J.K.J.’s financial interests in these companies include consulting fees and/or equity. J.K.J.’s interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. W.W.W. is a scientific co-founder of and holds equity in Senti Biosciences. A.S.K. is a scientific advisor for and holds equity in Senti Biosciences and Chroma Medicine, and is a co-founder of Fynch Biosciences and K2 Biotechnologies.

A mammalian gene circuit engineering platform enables clinically-approved drug-regulated control of therapeutic immune cells

Data and materials availability:

Plasmids encoding select synZiFTR constructs have been deposited at Addgene for distribution. All DNA constructs and cell lines are available from A.S.K. All sequencing data is deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession code PRJNA714135. All other datasets are deposited on Dryad at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s7h44j19v. Computer code is available at https://github.com/khalillab/synZiFTR-analyses and archived on Zenodo at 10.5281/zenodo.7216675.

References and Notes

- 1.Fischbach MA, Bluestone JA, Lim WA, Cell-based therapeutics: the next pillar of medicine. Sci Transl Med 5, 179ps177 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitada T, DiAndreth B, Teague B, Weiss R, Programming gene and engineered-cell therapies with synthetic biology. Science 359, eaad1067 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie M, Fussenegger M, Designing cell function: assembly of synthetic gene circuits for cell biology applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 507–525 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim WA, June CH, The Principles of Engineering Immune Cells to Treat Cancer. Cell 168, 724–740 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay KA, Cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified (CAR-) T cell therapy. Br J Haematol 183, 364–374 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan RA et al. , Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol Ther 18, 843–851 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuca G, Reppel L, Landoni E, Savoldo B, Dotti G, Enhancing Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Efficacy in Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 26, 2444–2451 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rafiq S, Hackett CS, Brentjens RJ, Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 17, 147–167 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L et al. , Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered with an inducible gene encoding interleukin-12 for the immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 21, 2278–2288 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao XJ, Chong LS, Kim MS, Elowitz MB, Programmable protein circuits in living cells. Science 361, 1252–1258 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roybal KT et al. , Precision Tumor Recognition by T Cells With Combinatorial Antigen-Sensing Circuits. Cell 164, 770–779 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roybal KT et al. , Engineering T Cells with Customized Therapeutic Response Programs Using Synthetic Notch Receptors. Cell 167, 419–432 e416 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schukur L, Geering B, Charpin-El Hamri G, Fussenegger M, Implantable synthetic cytokine converter cells with AND-gate logic treat experimental psoriasis. Sci Transl Med 7, 318ra201 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie M et al. , beta-cell-mimetic designer cells provide closed-loop glycemic control. Science 354, 1296–1301 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi BD et al. , CAR-T cells secreting BiTEs circumvent antigen escape without detectable toxicity. Nat Biotechnol 37, 1049–1058 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golumba-Nagy V, Kuehle J, Hombach AA, Abken H, CD28-zeta CAR T Cells Resist TGF-beta Repression through IL-2 Signaling, Which Can Be Mimicked by an Engineered IL-7 Autocrine Loop. Mol Ther 26, 2218–2230 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu B et al. , Augmentation of Antitumor Immunity by Human and Mouse CAR T Cells Secreting IL-18. Cell Rep 20, 3025–3033 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanitis E, Coukos G, Irving M, All systems go: converging synthetic biology and combinatorial treatment for CAR-T cell therapy. Curr Opin Biotechnol 65, 75–87 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mardiana S, Solomon BJ, Darcy PK, Beavis PA, Supercharging adoptive T cell therapy to overcome solid tumor-induced immunosuppression. Sci Transl Med 11, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong M, Clubb JD, Chen YY, Engineering CAR-T Cells for Next-Generation Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell 38, 473–488 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braselmann S, Graninger P, Busslinger M, A selective transcriptional induction system for mammalian cells based on Gal4-estrogen receptor fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 1657–1661 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gossen M, Bujard H, Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 5547–5551 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Favre D et al. , Lack of an immune response against the tetracycline-dependent transactivator correlates with long-term doxycycline-regulated transgene expression in nonhuman primates after intramuscular injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Journal of virology 76, 11605–11611 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lena AM, Giannetti P, Sporeno E, Ciliberto G, Savino R, Immune responses against tetracycline-dependent transactivators affect long-term expression of mouse erythropoietin delivered by a helperdependent adenoviral vector. J Gene Med 7, 1086–1096 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert LA et al. , CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Pinera P et al. , RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nat Methods 10, 973–976 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zalatan JG et al. , Engineering Complex Synthetic Transcriptional Programs with CRISPR RNA Scaffolds. Cell 160, 339–350 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlesworth CT et al. , Identification of preexisting adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat Med 25, 249–254 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner DL et al. , High prevalence of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9-reactive T cells within the adult human population. Nat Med 25, 242–248 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavletich NP, Pabo CO, Zinc finger-DNA recognition: crystal structure of a Zif268-DNA complex at 2.1 A. Science 252, 809–817 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert SA et al. , The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 175, 598–599 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rivera VM et al. , Long-term pharmacologically regulated expression of erythropoietin in primates following AAV-mediated gene transfer. Blood 105, 1424–1430 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beerli RR, Barbas CF 3rd, Engineering polydactyl zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Biotechnol 20, 135–141 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeder ML, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Sander JD, Voytas DF, Joung JK, Oligomerized pool engineering (OPEN): an ‘open-source’ protocol for making customized zinc-finger arrays. Nat Protoc 4, 1471–1501 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pabo CO, Peisach E, Grant RA, Design and selection of novel Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 70, 313–340 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sander JD et al. , Selection-free zinc-finger-nuclease engineering by context-dependent assembly (CoDA). Nat Methods 8, 67–69 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore M, Klug A, Choo Y, Improved DNA binding specificity from polyzinc finger peptides by using strings of two-finger units. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 1437–1441 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rockstroh JK et al. , Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV 2, e319–327 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs CL, Badiee RK, Lin MZ, StaPLs: versatile genetically encoded modules for engineering drug-inducible proteins. Nat Methods 15, 523–526 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tague EP, Dotson HL, Tunney SN, Sloas DC, Ngo JT, Chemogenetic control of gene expression and cell signaling with antiviral drugs. Nat Methods 15, 519–522 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feil R et al. , Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 10887–10890 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Indra AK et al. , Temporally-controlled site-specific mutagenesis in the basal layer of the epidermis: comparison of the recombinase activity of the tamoxifen-inducible Cre-ER(T) and Cre-ER(T2) recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 4324–4327 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang FS, Ho WQ, Crabtree GR, Engineering the ABA plant stress pathway for regulation of induced proximity. Sci Signal 4, rs2 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ede C, Chen X, Lin MY, Chen YY, Quantitative Analyses of Core Promoters Enable Precise Engineering of Regulated Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells. ACS Synth Biol 5, 395–404 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choe JH et al. , SynNotch-CAR T cells overcome challenges of specificity, heterogeneity, and persistence in treating glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med 13, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyrenius-Wittsten A et al. , SynNotch CAR circuits enhance solid tumor recognition and promote persistent antitumor activity in mouse models. Sci Transl Med 13, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber EW et al. , Transient rest restores functionality in exhausted CAR-T cells through epigenetic remodeling. Science 372, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chevallier P et al. , Overexpression of Her2/neu is observed in one third of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients and is associated with chemoresistance in these patients. Haematologica 89, 1399–1401 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho JH, Collins JJ, Wong WW, Universal Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Multiplexed and Logical Control of T Cell Responses. Cell 173, 1426–1438 e1411 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng HP et al. , Pharmacokinetic Interactions between the Hepatitis C Virus Inhibitors Elbasvir and Grazoprevir and HIV Protease Inhibitors Ritonavir, Atazanavir, Lopinavir, and Darunavir in Healthy Volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J, IL-12 deaths: explanation and a puzzle. Science 270, 908 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leonard JP et al. , Effects of single-dose interleukin-12 exposure on interleukin-12-associated toxicity and interferon-gamma production. Blood 90, 2541–2548 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levin AM et al. , Exploiting a natural conformational switch to engineer an interleukin-2 ‘superkine’. Nature 484, 529–533 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Purvis JE et al. , p53 dynamics control cell fate. Science 336, 1440–1444 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai L, Dalal CK, Elowitz MB, Frequency-modulated nuclear localization bursts coordinate gene regulation. Nature 455, 485–490 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Napolitani G, Rinaldi A, Bertoni F, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations synergistically trigger a T helper type 1-polarizing program in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 6, 769–776 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mittler F et al. , High-Content Monitoring of Drug Effects in a 3D Spheroid Model. Front Oncol 7, 293 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bashor CJ et al. , Complex signal processing in synthetic gene circuits using cooperative regulatory assemblies. Science 364, 593–597 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donahue PS et al. , The COMET toolkit for composing customizable genetic programs in mammalian cells. Nat Commun 11, 779 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khalil AS et al. , A Synthetic Biology Framework for Programming Eukaryotic Transcription Functions. Cell 150, 647–658 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ran FA et al. , In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature 520, 186–191 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pausch P et al. , CRISPR-CasPhi from huge phages is a hypercompact genome editor. Science 369, 333–337 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu X et al. , Engineered miniature CRISPR-Cas system for mammalian genome regulation and editing. Mol Cell 81, 4333–4345 e4334 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langan RA et al. , De novo design of bioactive protein switches. Nature 572, 205–210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Z et al. , Programmable design of orthogonal protein heterodimers. Nature 565, 106–111 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu I et al. , Modular design of synthetic receptors for programmed gene regulation in cell therapies. Cell 185, 1431–1443 e1416 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu M et al. , TGF-beta suppresses type 2 immunity to cancer. Nature 587, 115–120 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bai Z et al. , Single-cell antigen-specific landscape of CAR T infusion product identifies determinants of CD19-positive relapse in patients with ALL. Sci Adv 8, eabj2820 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isalan M, Choo Y, Klug A, Synergy between adjacent zinc fingers in sequence-specific DNA recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 5617–5621 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim JS, Pabo CO, Getting a handhold on DNA: design of poly-zinc finger proteins with femtomolar dissociation constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 2812–2817 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greisman HA, Pabo CO, A general strategy for selecting high-affinity zinc finger proteins for diverse DNA target sites. Science 275, 657–661 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calis JJ et al. , Properties of MHC class I presented peptides that enhance immunogenicity. PLoS computational biology 9, e1003266 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park M, Patel N, Keung AJ, Khalil AS, Engineering Epigenetic Regulation Using Synthetic Read-Write Modules. Cell 176, 227–238 e220 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zufferey R et al. , Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. Journal of virology 72, 9873–9880 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Casini A et al. , R2oDNA designer: computational design of biologically neutral synthetic DNA sequences. ACS Synth Biol 3, 525–528 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kent WJ et al. , The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res 12, 996–1006 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL, Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10, R25 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Plasmids encoding select synZiFTR constructs have been deposited at Addgene for distribution. All DNA constructs and cell lines are available from A.S.K. All sequencing data is deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession code PRJNA714135. All other datasets are deposited on Dryad at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s7h44j19v. Computer code is available at https://github.com/khalillab/synZiFTR-analyses and archived on Zenodo at 10.5281/zenodo.7216675.