Abstract

Objective:

The study of human genomics has established that pathogenic variation in genes with diverse cellular and molecular functions can underlie a single disorder. For example, hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) can be a phenotypic trait associated with over 80 genes; frequently only a few individuals are described for each gene. Herein we describe molecular and clinical characterization of a large cohort of individuals with biallelic variation in ENTPD1, a gene previously linked to spastic paraplegia 64 (MIM# 615683).

Methods:

Individuals were recruited worldwide through GeneMatcher. Deep phenotyping and molecular characterizations were performed.

Results:

A total of 22 previously undescribed individuals from 13 unrelated families were studied and additional phenotypic information was collected from published cases. Nine novel pathogenic ENTPD1 variants: c.398_399delinsAA; p.(Gly133Glu), c.540del; p.(Thr181Leufs*18), c.640del; p.(Gly216Glufs*75), c.185T>Gspan style=“font-family:’Times New Roman’“>; p.(Leu62*), c.1531T>C; p.(*511Glnext*100), c.967C>T; p.(Gln323*), including three recurrent variants c.1109T>A; p.(Leu370*), c.574-6_574-3del (splicing variant), and c.770_771del; p.(Gly257Glufs*18) were delineated. Common shared clinical findings include: early childhood onset, progressive spastic paraplegia, intellectual disability, dysarthria, dysmorphic facies, and brain hypomyelination. In vitro assays demonstrate that ENTPD1 expression and ATP hydrolysis are impaired and that the c.574-6_574-3del variant causes exon skipping.

Interpretation:

The ENTPD1 locus trait consists of childhood disease onset, intellectual disability, progressive spastic paraparesis, dysarthria, dysmorphic facies, and brain hypomyelination, with some individuals showing apparent regression of neurocognition. Investigation of an allelic series of ENTPD1: i) expands previously described clinical features of ENTPD1-related neurological disease, ii) highlights the importance of genotype-driven deep phenotyping, and iii) provides insights into the neurobiology of the disease trait.

Introduction

Genome sequencing and clinical genomics have markedly improved molecular diagnostic rates in rare Mendelian disorders by accelerating novel disease gene and variant allele discovery and expanding the phenotypic spectrum associated with known disease genes1–3. This progress has resulted in the understanding that a single family of disorders can be caused by pathogenic variation in genes with diverse functions. For example, hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSP) are a large group of neurological disorders affecting 1.8 in 100,000 individuals globally4. Inheritance patterns for HSP disease traits are variable, including autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), X-linked, de novo, and mitochondrial inheritance5. Despite shared clinical and pathophysiologic features, HSP results from pathogenic variation in over 80 genes/loci involved in distinct cellular processes, including mitochondrial functioning, lipid metabolism, vesicle/axonal trafficking, and myelination6. With the rapid pace of novel disease gene discovery7, this number will likely continue to expand. In fact, an “HSPome” of known HSP disease genes, candidate disease genes, and proximal interactors has implicated almost 600 potential HSP genes8.

As with the hereditary neuropathies9, the allelic spectrum of HSP is unevenly distributed across known disease genes. For example, pathogenic variation in SPAST, the cause of AD spastic paraplegia 4 (MIM# 182601), accounts for approximately 60% of HSP diagnoses10–13. The abundance of AD spastic paraplegia 4 and other “common” HSP causes reflects historical population-specific events, e.g. founder effect or population bottlenecks, or high frequency mutational events occurring as a consequence of genomic architecture, e.g. Alu/Alu-mediated rearrangements (AAMRs) due to abundance of Alu repetitive elements and genomic instability within SPAST14.

The remaining allelic spectrum of HSP disease exhibits extensive molecular heterogeneity and is a collection of ultra-rare diseases, often with only a few individuals described for each gene locus. Studies investigating the phenotypic spectrum from different families and ethnicities worldwide and diverse pathogenic variant alleles, i.e. an allelic series for individual HSP genes, are often lacking. For example, AR spastic paraplegia type 64 (SPG64, MIM #615683) due to biallelic pathogenic variants in ENTPD1, the gene encoding the ectonucleosidase ENTPD1 involved in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis, has been described in only a few individuals with limited and seemingly dissimilar phenotypic characterization8; 15–17. It is critical to deeply phenotype large cohorts of individuals with rare diseases, potentially revealing previously undescribed features (i.e. phenotypic expansion) and therefore providing a comprehensive clinical understanding of the disease process and gene-associated trait.

HSP is clinically classified into “pure” and “complex/complicated” with unifying features of corticospinal tract nerve axonopathy, resultant progressive gait difficulty, and axonal length-dependent neuropathy18. Complex HSP has a broad phenotypic spectrum which additionally encompasses developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID), structural brain abnormalities, white matter abnormalities, ataxia, epilepsy, amyotrophy, and visual abnormalities19. Given the large molecular and phenotyptic spectrum of HSP, complex HSP frequently overlaps with other neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD); e.g. leukodystrophies, cerebellar ataxias, and syndromic DD/ID20.

Herein, we molecularly characterize and comprehensively describe the phenotypic and molecular features of a large cohort of individuals with biallelic variants in ENTPD1 and provide evidence for a complex neurodevelopmental disorder with progressive spastic paraplegia.

Materials and methods

Patient identification and recruitment

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Baylor College of Medicine (Protocol H-29697) or through other collaborative local IRBs. Additional affected participants were identified through GeneMatcher21 or personal communication. Written consent, including consent for publication of photographs, was obtained for all participants. Study participants were examined by a clinical geneticist and/or neurologist and phenotypic features were described using Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms22. Brain magnetic resonance images (MRIs) were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed by a board certified neuroradiologist (JVH).

Exome sequencing

For family 1, trio exome sequencing (ES) was performed at the Human Genome Sequencing Center (HGSC) at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) through the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (BHCMG) initiative as previously described23. For all other identified families, ES was performed by local institutions or commercial clinical molecular diagnostic laboratories.

Absence of heterozygosity

BafCalculator (https://github.com/BCM-Lupskilab/BafCalculator)2, an in-house developed bioinformatic tool that extracts the calculated B-allele frequency (ratio of variant reads/total reads) from unphased exome data, was used to calculate genomic intervals and total genomic content of absence of heterozygosity (AOH) intervals as a surrogate measure for runs of homozygosity (ROH) likely representing identity-by-descent (IBD) genomic intervals. B-allele frequency was transformed by subtracting 0.5 and taking the absolute value for each data point before being processed by circular binary segmentation using the DNAcopy R Bioconductor package. The estimated coefficient of inbreeding values from ROH were calculated as the fraction of the sum of AOH genomic intervals >1.5 Mb in size to the length of the autosomal genome (3,100 Mb).

Confirmation of alternative splicing

Whole blood RNA from family 5 was extracted using the PAXgene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with poly-dT (20) primers according to manufacturer’s protocol. Amplicons were generated from control, proband, and parental cDNA using HotStartTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to manufacturer’s protocol. DNA bands at various sizes were excised, purified via the PureLink PCR purification and gel extraction kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), and Sanger sequenced at the BCM sequencing core facility.

Real-time PCR

Immortalized lymphoblast cell lines from affected individuals were established from blood samples at The Centre for Applied Genomics (Toronto, Canada). Total RNA was obtained from affected and control lymphoblast cell lines with the RNeasyMinikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) with iScript kit (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was amplified with gene-specific primers and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and read on a CFX96 Touch Real-time PCR Detection System. Gene expression was quantified using the standard Ct method with CFX software, and all data corrected against GAPDH as an internal control.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 10 mg/mL each of aprotinin, phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, and leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Protein samples were resolved by standard SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, incubated in blocking, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibody (ENTPD1, Abcam ab108248). Membranes were washed and incubated with secondary antibody (HRP conjugated anti-rabbit; BioRad Laboratories). Blots were visualized by autoradiography using the Clarity Western ECL substrate (BioRad Laboratories). Control protein was extracted from healthy, unrelated, age-matched control cell lines.

ATPase and ADPase assay

A total of 250,000 lymphoblasts were harvested per technical replicate from each cell line. The cells were washed and each replicate plated in a single well of a round bottom 96-well plate. Cells were then incubated with either 10 mM ADP or 10 mM ATP, or left untreated, for 30 min at 37°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new, flat bottom 96-well plate and phosphate concentration was measured using the Malachite Green Phosphate Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The normalized phosphate production reported is fold change relative to untreated samples.

Flow Cytometry

Blood samples were collected in 3 ml EDTA tubes and analyzed for immune cell subsets using the following surface markers: CD16, CD56, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD2, CD15, CD19, CD20, HLA-DR, CD39 and CD73. All samples were analyzed using Beckman Coulter dual Laser Navios Flow Cytometer equipped with 488nm Argon and a 635 nm-diode laser, allowing six color fluorescence data acquisition (Beckman Coulter, Inc., 250 S., Kraemer Blvd, Brea, CA).

Sural nerve biopsy

Paraffin embedded sural nerve biopsy sections of the patient and a control sample were stained immunohistochemically for CD39 (Leica/Novocastra, 1cc, clone NCL-CD39, LOT-6017994, 1:50), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and standard staining protocols.

Results

Index proband

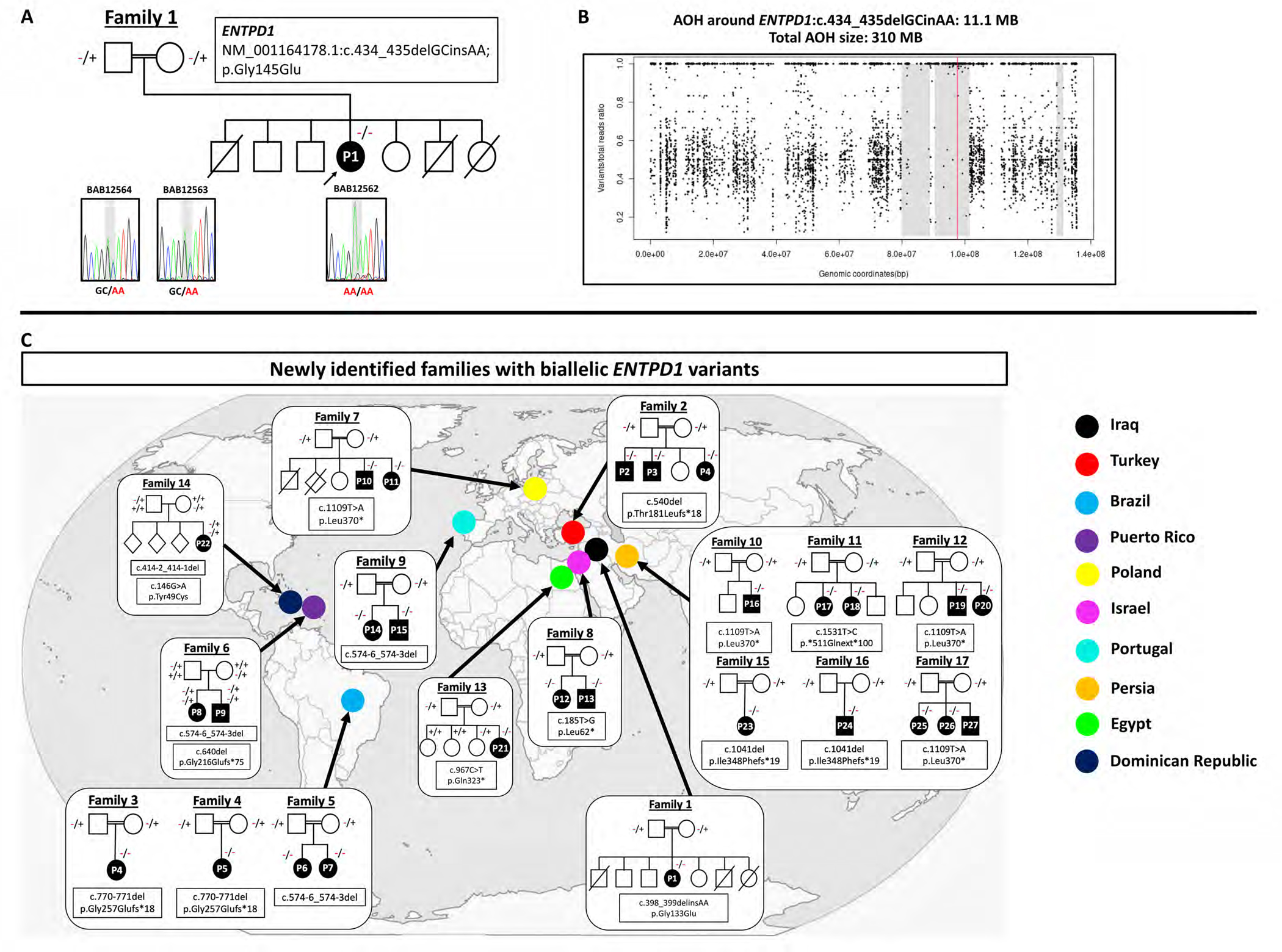

The index patient (P1, family 1; Fig. 1A) is an eight-year-old girl referred to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (BHCMG) for DD/ID, spastic paraplegia and progressive gait impairment. She was born at term to first cousin Iraqi parents and has three healthy living siblings and three unaffected deceased siblings (age of death at five years, 13 years, and five years from leukemia, unknown etiology, and febrile illness, respectively). Her prenatal course was complicated by intrauterine growth restriction of unknown etiology. Concerns about the proband’s development arose at one year of age due to lack of independent ambulation. First steps did not occur until after two years of age. At three years of age, the ability to ambulate independently deteriorated and she developed spastic paraplegia. Her neurological examination at 8y showed dysarthria, muscle weakness with amyotrophy, and hyperreflexia in the upper extremities with areflexia in the lower extremities (Table S1). Trio ES revealed a novel homozygous variant in ENTPD1, NM_001776.6: c.398_399delinsAA; p.(Gly133Glu). Sanger sequencing confirmed the multinucleotide variant allele in the homozygous state in the proband and in the heterozygous state in her unaffected parents (Fig. 1A). The variant is absent from gnomAD, is only found in this family in our research database of >13,000 exomes, and the affected amino acid residue is fully conserved across species (Fig. 1C, Table 1). ENTPD1: c.398_399delinsAAis located in an 11.1 Mb AOH block and the total AOH size of the proband is 310 Mb, consistent with the offspring of a first cousin mating (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Pedigrees and variant information for families with ENTPD1-related neurological disease.

(A) Pedigree and Sanger sequencing results of index family 1 with the homozygous variant NM_001766.6: c.398_399delinsAA; p.(Gly133Glu). (B) Absence of heterozygosity (AOH) plot of P1 showing a total AOH size of 310 Mb and 11.1 Mb of AOH around ENTPD1: c.398_399delinsAA (red line). (C) Conservation of amino acid residue p.Gly145 (D) Pedigrees and variant information of newly identified families with biallelic ENTPD1 variants and countries of origin.

Table 1.

ENTPD1 variants identified in this study.

| Family # | Ancestry | Genomic Position (hg19) | Transcript | Nucleotide change | Amino Acid change | Zygosity | gnomAD AF | CADD (v1.6) score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | Iraq | Chr10:97602236 GC>AA | NM_001776.6 | c.398_399delinsAA | p.Gly133Glu | hmz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | - |

| 2 | Turkey | Chr10:97604358del | NM_001776.6 | c.540del | p.Thr181Leufs*18 | hmz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | - |

| 3,4 | Brazil | Chr10:97605310_11del | NM_001776.6 | c.770_771del | p.Gly257Glufs*18 | hmz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | - |

| 6 | Caucasian, Puerto Rico | Chr10:97605179del | NM_001776.6 | c.640del | p.Gly216Glufs*75 | cmp htz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | - |

| 5, 6, 9 | Brazil, Puerto Rico, Portugal | Chr10:97605106_9del | NM_001776.6 | c.574-6_574-3del | - | hmz, cmp htz in 6 | 0 htz, 0 hmz | - |

| 7, 10, 12 | Poland, Iran | Chr10:97620260 T>A | NM_001776.6 | c.1109 T>A | p.Leu370* | hmz | 2 htz, 0 hmz | 33 |

| 8 | Arabic | Chr10:97599488 T>G | NM_001776.6 | c.185 T>G | p.Leu62* | hmz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | 36 |

| 11 | Persia | Chr10:97626138 T>C | NM_001776.6 | c.1531 T>C | p.*511Glnext*100 | hmz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | - |

| 13 | Egypt | Chr10:97607356 C>T | NM_001776.6 | c.967 C>T | p.Gln323* | hmz | 0 htz, 0 hmz | 32 |

AF-allele frequency; CADD-combined annotation dependent depletion; hmz-homozygous; htz-heterozygous; cmp htz-compound heterozygous

Recruitment of additional families with biallelic ENTPD1 variation

Given limited phenotypic characterization of ENTPD1-related neurological disease, we identified additional cases through GeneMatcher (https://genematcher.org/) and inquiries with neurogenetic research laboratories from around the globe. These efforts resulted in a total of 13 unrelated families with 22 affected individuals (Fig. 1D, Table 1, Table S1). Additional recruited familis were from diverse countries and backgrounds, including Turkey (Family 2), Brazil (Families 3, 4, and 5), Puerto Rico (Family 6), Poland (Family 7), Israel (Family 8), Portugal (Family 9), Persia (Families 10, 11, 12), and Egypt (family 13). All affected individuals were born to consanguineous parents except family 6. Review of the literature revealed an additional five families with nine affected individuals for whom further phenotypic data were obtained (Table S1)8; 15–17.

Phenotypic spectrum of ENTPD1-related neurological disease

Comparison of phenotypic features using HPO terms among all affected individuals revealed both major similarities as well as differences, suggestive of a phenotypic spectrum with a ‘clinical synopsis’ of shared commonalities in individuals with an ENTPD1-related pleiotropic neurological disease trait (Table 2, Table S1). The average age of the cohort at last examination was 16 years (range 3–30 years, median 15 years). All affected individuals had symptom onset in early childhood, global developmental delay/intellectual disability, and progressive spastic paraplegia with impaired ambulation. Behavioral abnormalities, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), aggression, and stereotypies were common and occurred in 15/31 individuals. A total of 18/31 individuals had neurocognitive regression in addition to progressive spastic paraplegia. Language regression and regression in the ability to complete activities of daily living were common in these individuals.

Table 2.

Phenotypic features of ENTPD1-related neurological disease

| Clinical features | This cohort | Prior publications | All affected individuals |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Early childhood age of onset (HP:0011463) | 22/22 | 9/9 | 31/31 |

| Developmental delay/intellectual disability (HP:0012758) | 22/22 | 9/9 | 31/31 |

| Progressive spastic paraplegia (HP:0007020) | 22/22 | 9/9 | 31/31 |

| Gait impairment (HP:0002355) | 22/22 | 9/9 | 31/31 |

| Abnormal reflexes (HP:0031826) | 11/22 | 9/9 | 20/31 |

| Dysarthria (HP:0001260) | 13/22 | 7/9 | 20/31 |

| Developmental regression (HP:0002376) | 15/22 | 3/9 | 18/31 |

| Dysmorphic facies (HP:0001999) | 16/22 | NR | 16/31 |

| Weakness (HP:0001324) | 14/22 | 3/9 | 17/31 |

| Behavioural abnormalities (HP:0000708) | 10/22 | 5/9 | 15/31 |

| Cerebral hypomyelination (HP:0006808) | 11/18 | 3/8 | 14/26 |

| Neuropathy (HP:0009830) | 13/22 | NR | 13/31 |

| Hand and foot deformities (HP:0001155 and 0001760) | 8/22 | 3/9 | 11/31 |

| Hypotonia (HP:0001252) | 5/22 | NR | 5/31 |

| Cataracts (HP:0000518) | 3/22 | 1/9 | 4/31 |

| Epilepsy (HP:0001250) | 2/22 | NR | 2/31 |

| Scoliosis (HP:0002650) | 3/22 | NR | 3/31 |

NR-not reported

The neurological examination revealed dysarthria (20/31), axial hypotonia (14/31), amyotrophy (8/31), and weakness (17/31). Abnormal reflexes were common and included hyperreflexia (8/31), hyporeflexia (9/31), and areflexia (6/31) in the lower extremities, consistent with mixed upper and lower motor neuron dysfunction. Additionally, a total of eight individuals had electromyography/nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS). Four individuals had normal EMG/NCS despite abnormal reflexes (P5, P8, P30, P31). The remainder had findings consistent with motor axonal neuropathy (P13, P14), myopathic changes (P17), and polyradiculopathy (P22; Table S1). Dysmorphic facies were common (16/31) and included low anterior hairline, synophrys, low-set ears with fleshy lobes, prominent philtrum, and mild micrognathia (Fig. 2A). Centripetal obesity, scoliosis, and genu valgus were observed (Fig. 2B). Additional musculoskeletal abnormalities included camptodactyly, spatulated fingers, broad toes, and pes cavus with progressive worsening of camptodactyly with age (Fig. 2C–H). Spine radiographs confirmed scoliosis (Fig. 2I). Hip x-rays performed due to progressive gait difficulties were generally unremarkable with normal bone structure (Fig. 2J).

Figure 2. Representative photographs and radiographs of individuals with ENTPD1-related neurological disease.

(A) Facial pictures of P17 at 7 years of age and P22 at 8 years showing low anterior hairline, synophrys, low-set ears with fleshy lobes, prominent philtrum, and micrognathia. (B) Pictures of P1 at 8 years of age and P22 at 8 years showing centripetal obesity, thoracic kyphosis, decreased lumbar lordosis, genu valgus, and cubitus valgus. (C) Representative hand images of P1, P6, and P10 at 8, 15, and 3 years, respectively, showing broad fingers with camptodactyly and spatulated finger tips (P1), mild camptodactyly of 4th and 5th digits (P6), and camptodactyly of all digits (P10). (D) Representative foot images of P1, P6, and P10 at 8, 15, and 3 years, respectively, showing broad toes with camptodactyly (P1), pes cavus with camptodactyly (P6), and broad great toes bilaterally and broad right 4th toe with camptodactyly (P10). (E) Hand radiographs of P1 at 8 years of age showing severe camptodactyly. (F) Foot radiographs of P1 at 8 years showing camptodactyly. (G) Foot radiographs of P6 at 15 years showing cavus and camptodactyly. (H) Foot radiographs of P28 at 19 years of age showing severe camptodactyly. (I) Sagittal spine radiograph of P1 at 8 years showing lumbar lordosis. (J) Hip radiograph of P10 at 3 years showing no gross abnormalities.

ENTPD1-related neurological disease causes a unique pattern of hypomyelination

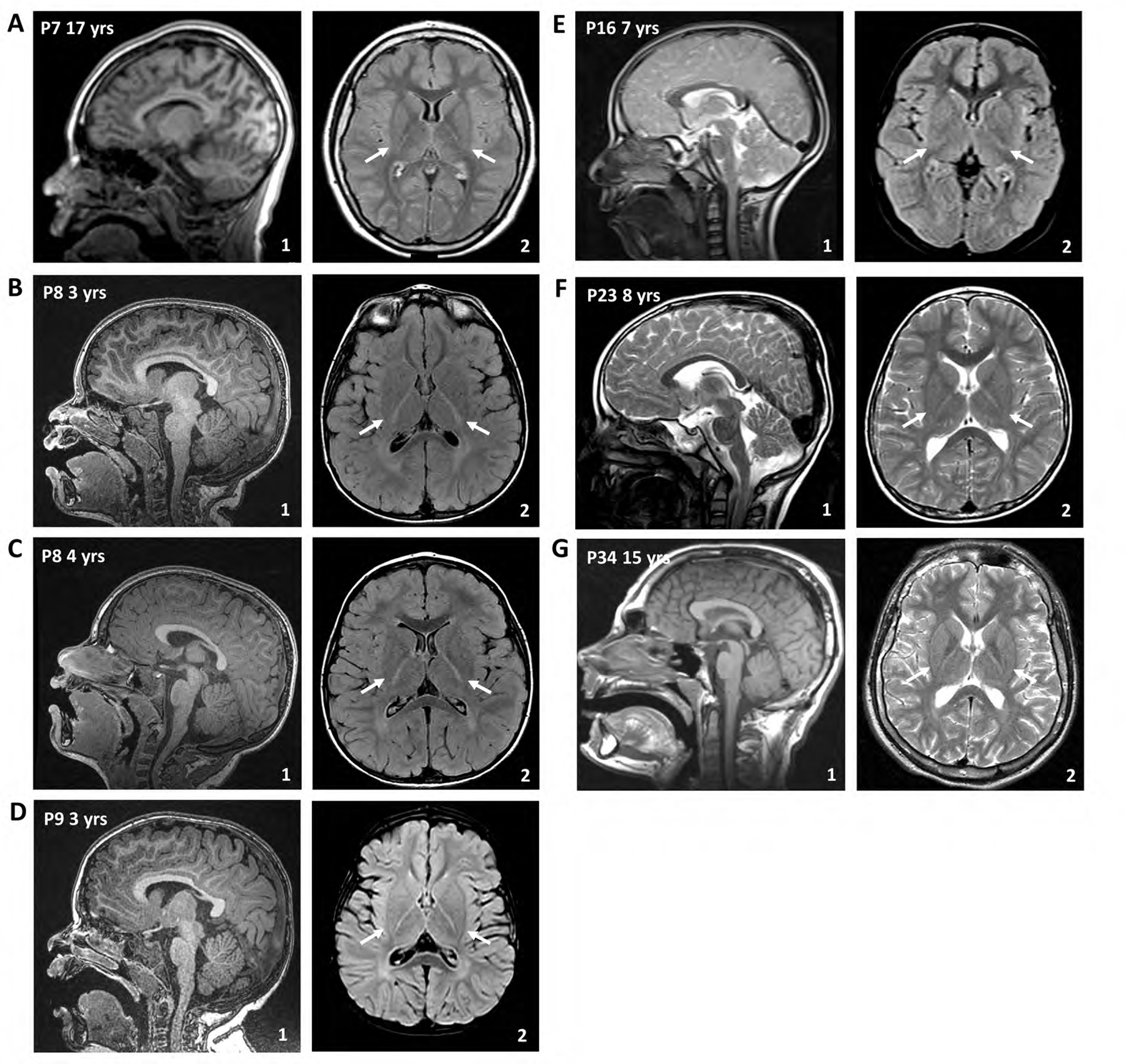

As previous reports of affected individuals with biallelic pathogenic ENTPD1 variants described brain white matter abnormalities in only two of nine affected individuals8, we sought to better characterize neuroimaging features of the ENTPD1-related disease trait. Brain MRI images were available for nine individuals and were reviewed with and by a board certified pediatric neuroradiologist (Fig. 3A–F). For an additional nine other individuals, the referring clinicians provided an MRI interpretation. Finally, for four individuals, no neuroimaging was obtained.

Figure 3. Individuals with biallelic pathogenic ENTPD1 variants have hypomyelination of the brain.

Representative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain of affected individuals from different families at different ages. Arrows in the axial images are highlighting hypomyelination of the posterior limb of the internal capsule. (A) Sagittal T1-weighted imaging (1) and axial T2-FLAIR of P8 at 17 years of age. (B) and (C) Sagittal T1-weighted imaging (1) and axial T2-FLAIR of P9 at 3 and 4 years, respectively. (D) Sagittal T1-weighted imaging (1) and axial T2-FLAIR of P10 at 3 years. (E) Sagittal T2-weighted imaging (1) and axial T2-FLAIR of P17 at 7 years. (F) Sagittal T1-weighted imaging (1) and axial T2 of P29 at 15 years.

Thinning of the corpus callosum was present in three individuals for whom a brain MRI was available for review or per report from the referring clinicians. Delayed myelination and subsequent hypomyelination was observed in 14 individuals. In young children, a diffuse hypomyelinating pattern was observed (Fig. 3B–D). In older children/adolescents, persistent hypomyelination of the posterior limb of the internal capsule was most evident (Fig. 3A,E). Review of a previously published individual (Family 17, P29)16 not initially reported to have brain MRI abnormalities was subsequently found to also have hypomyelination with absence of myelination in the posterior limb of the internal capsule at 15 years of age (Fig. 3F).

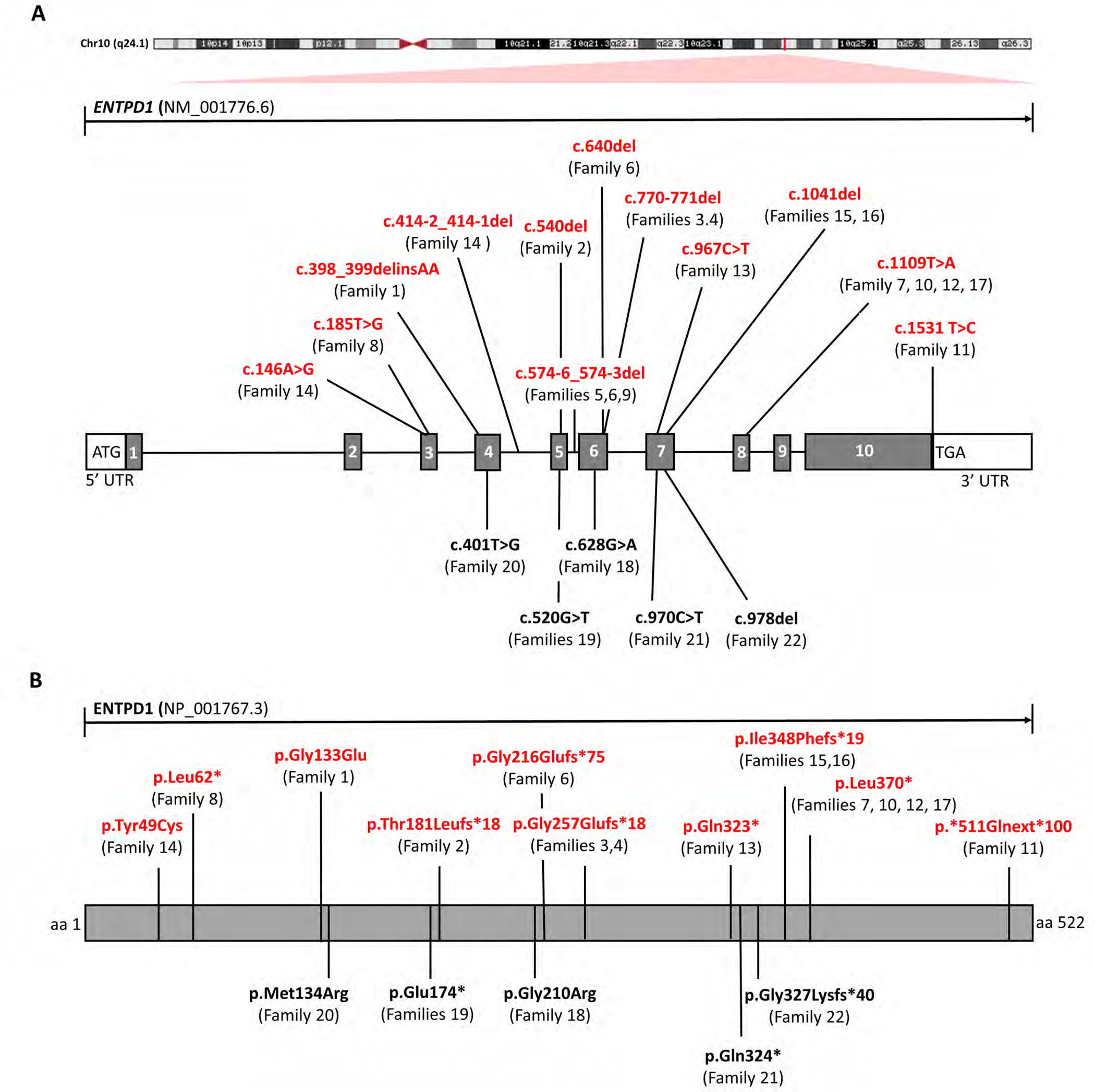

Biallelic pathogenic ENTPD1 variants identified in this cohort

The cohort of individuals with biallelic ENTPD1-related neurological disease is very diverse with 13 newly identified families originating from 9 different countries (Fig. 1D). ENTPD1 is located on chromosome 10 and contains 10 exons; the major annotated canonical transcript is NM_001776.6 (ENST00000371205.5). Previous reports identified five distinct ENTPD1 variants with two missense and three predicted loss-of function (LoF) variant alleles: c.628G>A; p.(Gly210Arg), c.520G>T; p.(Glu174*), c.401T>G; p.(Met134Arg), c.970C>T; p.(Gln324*), and c.978del; p.(Gly327Lysfs*40)8; 15–17. We describe nine novel variants (Fig. 4A, B) of which seven are LoF: c.540del; p.(Thr181Leufs*18), c.640del; p.(Gly216Glufs*75), c.1109T>A; p.(Leu370*), c.185T>G; p.(Leu62*), c.1531T>C; p.(*511Glnext*100), c.967C>T; p.(Gln323*), and c.770_771del; p.(Gly257Glufs*18). Additionally, one multinucleotide variant resulting in a single amino acid substitution, c.398_399delinsAA; p.(Gly133Glu), and one splicing variant, c.574-6_574-3del, were identified (Fig. 4A, B).

Figure 4. Biallelic pathogenic ENTPD1 variants identified in this cohort.

(A) Schematic showing chromosomal location and gene structure of ENTPD1. Previously unreported variants are labeled in red and previously published variants in black. (B) Linear amino acid structure of ENTPD1 and location of previously unreported (red) and published variant alleles (black).

All variants are ultra-rare24 and absent from gnomAD in both the heterozygous and homozygous state. The exception, c.1109T>A; p.(Leu370*), is found in two heterozygotes of European non-Finnish descent; but it is important to note the bias of European descent genomes in the gnomAD database. All variants are predicted damaging by in silico analysis and have high CADD scores when available (Table 1). The most common variants observed in this cohort were the splicing variant c.574-6_574-3del found in families 5 (Brazilian), 6 (Puerto Rican), and 9 (Portuguese) and c.1109T>A; p.(Leu370*) found in families 7, 10 and 12 (Polish and Persian).

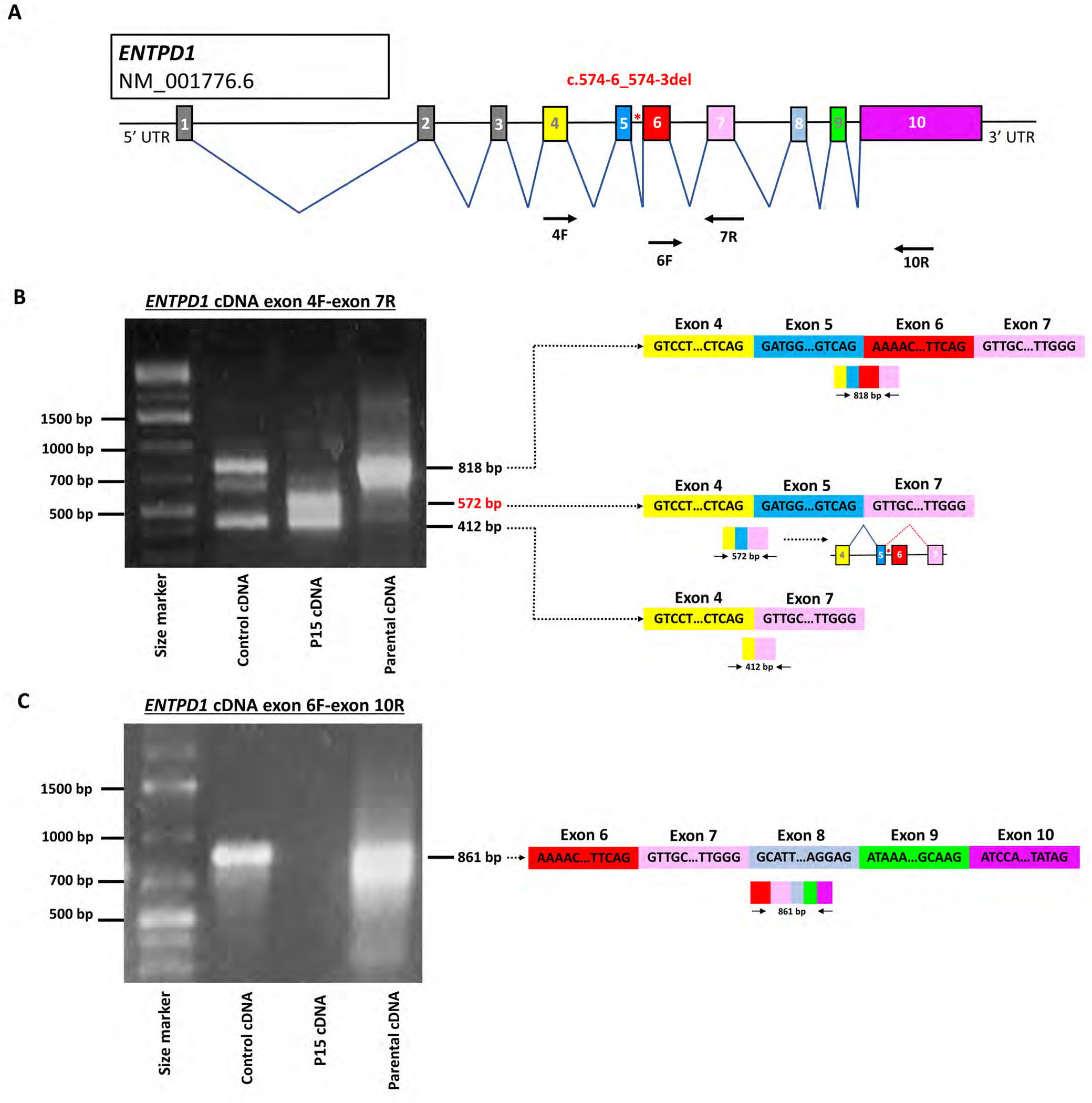

Intronic splicing variant results in alternative splicing and exon skipping

The majority of ENTPD1 variants identified in this study are LoF variants predicted to undergo nonsense mediated decay or result in a truncated protein (Fig. 4B)25. However, the impact on gene function of the intronic variant c.574-6_574-3del was unclear. As the variant falls within intron 5, we hypothesized it causes aberrant splicing via either exon skipping, intron inclusion or a combination of both. To test this hypothesis, cDNA was synthesized from control, homozygous proband (P16), and heterozygous carrier parents from family 9 and amplified using separate primer pairs for exons 4–7 and exons 6–10 (Fig. 5A). Amplification of exons 4–7 showed an 818 bp product in wildtype control and heterozygous parent but not the homozygous affected proband (Fig. 5B). Sanger dideoxynucleotide DNA sequencing confirmed that this product contains exons 4, 5, 6, and 7. Furthermore, the proband showed a 572 bp product absent from the control and parental samples. Sanger sequencing of the 572 bp product showed exons 4, 5, 7 and complete absence of exon 6, evidence confirming exon skipping in the affected proband. As a second confirmatory step of exon 6 skipping in the proband, primers for exon 6 and exon 10 were used for amplification (Fig. 5C). In the control and parental samples, an 861 bp PCR product was detected with Sanger sequencing confirming presence of exons 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. No amplification was present in the proband P7, consistent with absence of cDNA transcript including exon 6.

Figure 5. Alternative splicing due to ENTPD1:c.574-6_574-3del results in skipping of exon 6.

(A) Schematic of ENTPD1 NM_001776.6, the most widely expressed trancript, showing 10 different exons. ENTPD1: c.574-6_574-3del is located in intron 5 (red asterisk). Arrows show location of primers for cDNA amplification. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis image of ENTPD1 cDNA exon 4F and 7R amplification and schematic of resultant splicing products. Unaffected wildtype control cDNA and heterozygous parental cDNA show amplification of a bands at 818 bp not found in the affected proband sample (P7). Sanger sequencing confirmed that the 818 bp band contains exons 4, 5, 6, and 7 in control and unaffected parent. By contrast, the proband P7 who carries the homozygous ENTPD1: c.574-6_574-3del variant contains an alternative 572 bp product including exons 4, 5, and 7 only and thus skipping exon 6 completely. All three samples additionally contain a smaller product at 412 bp only containing exons 4 and 7. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis image of ENTPD1 cDNA exon 6F and 10R amplification. Unaffected wildtype control cDNA and heterozygous parental cDNA show amplification of an 861 bp band containing exons 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. No amplification is present in the homozygous proband sample.

Biallelic ENTPD1 variants impair ATP hydrolysis and ENTPD1 expression

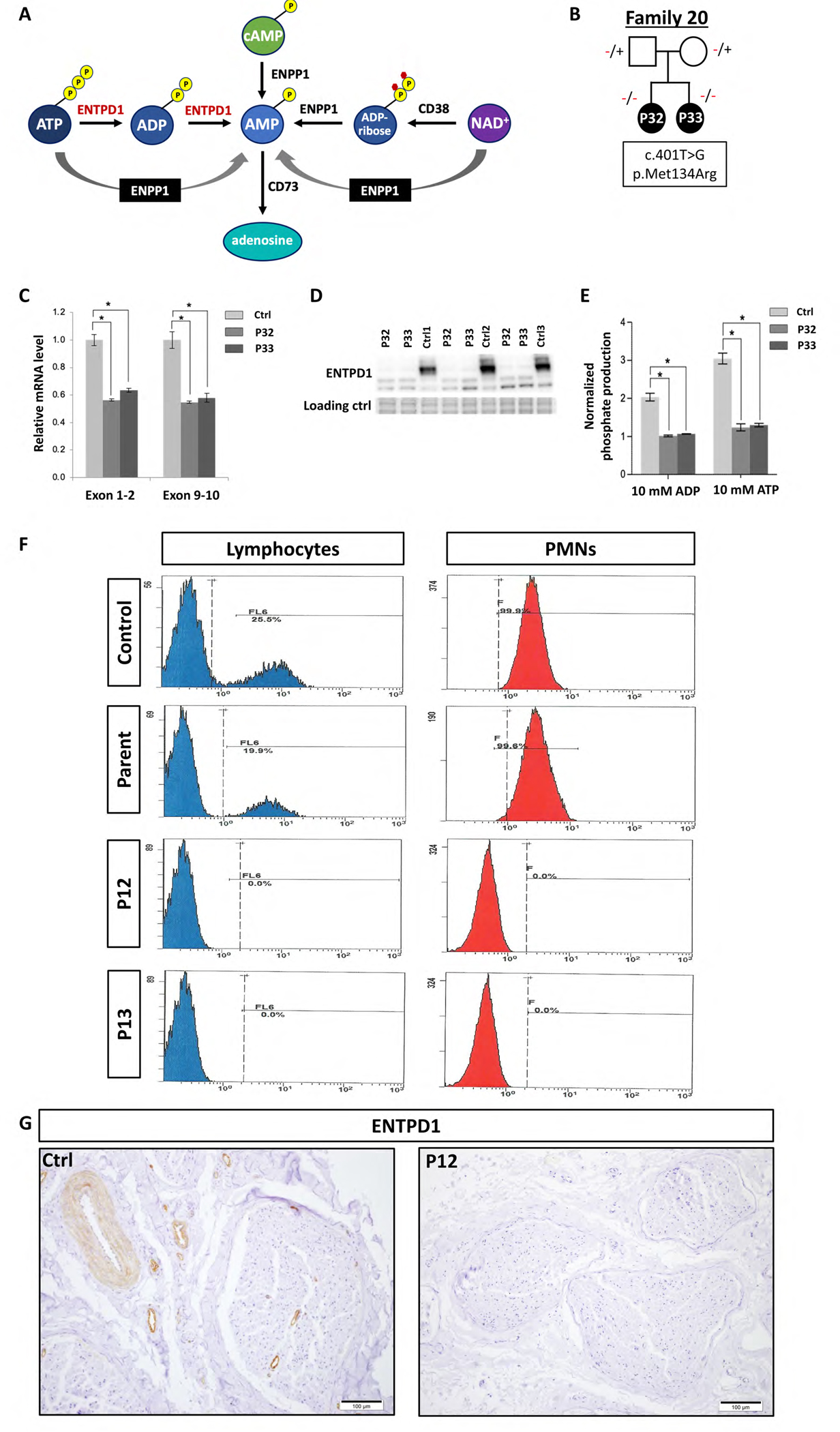

Given that ENTPD1 is an essential enzyme in the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and ADP to AMP (Fig. 6A), we next tested the effect of the homozygous ENTPD1 missense variant c. 401T>G; p.(Met134Arg) on ATP/ADP metabolism. Patient lymphoblasts were obtained fom family 16 (P27 and P28) (Fig. 6B). Quantitative PCR of control and proband samples revealed significantly decreased mRNA levels in both affected individuals compared to control with approximately 50% reduction (Fig. 6C). Western blot analysis of ENTPD1 protein from control and affected probands showed a substantial reduction in the predominant, higher molecular weight/relative molecular mass (Mr) band compared to control individuals with concurrent increase in the intensity of the lower weight band. However, overall ENTPD1 protein levels were still markedly decreased in the affected individuals compared to controls (Fig. 6D). To test the functional effect of altered ENTPD1 protein expression on ATP and ADP hydrolysis, ATPase and ADPase activity of proband samples were measured using normalized phosphate production as a readout. This experiment showed significantly decreased phosphate production in lymphoblasts obtained from P27 and P28 compared to control, consistent with impaired ATP/ADP hydrolysis due to the homozygous missense variant ENTPD1:c.401T>G (Fig. 6E). Given that ENTPD1 is highly expressed in lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), flow cytometry was performed on whole blood from P13, P14, and heterozygous parental sample with ENTPD1:c.185T>G; p.(Leu62*), which showed complete absence of ENTPD1+ cells in homozygous individuals compared to parental and wildtype control (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, immunohstochemistry for ENTPD1 on paraffin sections of sural nerve from P13 showed complete absence of endo- and epineural vascular staining compared to control sample (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6. Biallelic ENTPD1 variants impair ATP hydrolysis and ENTPD1 expression.

(A) ATP metabolic pathway showing the role of ENTPD1 in hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and ADP to AMP. (B) Lymphoblasts were derived from family 16 with two affected siblings (P27 and P28) with homozygous ENTPD1:c.401T>G; p.(Met134Arg) variant. (C) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR of ENTPD1 mRNA levels, using primers spanning both exons 1–2 and exons 9–10 showing significantly decreased ENTPD1 mRNA levels in lymphoblasts from individuals with homozygous ENTPD1:c.401T>G variant. (D) Western blot of ENTPD1 p.(Met134Arg) showing deceased protein levels in patient lymphoblasts. The stain-free gel serves as the loading control. (E) Measured ATPase and ADPase activity using normalized phosphate production after incubation with either ATP or ADP at a final concentration of 10 mM for 30 min. * p<0.05. (F) Flow cytometry of ENTPD1+ lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) in blood samples from P13 and P14 with homozygous ENTPD1:c.185T>G; p.(Leu62*) variant compared to control and heterozygous parental samples. (G) Immunohistochemical staining for ENTPD1 performed on paraffin sections of sural nerve biopsy from P13 with variant ENTPD1:c.185T>G shows complete absence of endo- and epineural vascular staining compared to control sample.

Discussion

ENTPD1 was first identified as a candidate disease gene for AR DD/ID26 and subsequently linked to SPG64 (MIM# 615683) with only few affected individuals described to date8; 15–17. These individuals had overlapping features of spastic paraplegia and DD/ID, but were highly variable in other clinical neurologic characteristics, including reflexes, neuropathic findings, and brain white matter abnormalities (Table S1). The characterization of additional variant alleles and families is critical to provide a comprehensive overview of the AR disease trait associated with this locus. Deep phenotyping using HPO terms of all patients identified to date with biallelic pathogenic variants in ENTPD1 delineated a clinical synopsis of the associated AR disease trait, which consists of: childhood disease onset, intellectual disability, progressive spastic paraparesis, dysarthria, neurocognitive regression, dysmorphic facies, and brain hypomyelination (Table 2, Table S1). Given the progressive nature and potential neurodegenerative process accompanying ENTPD1-related disease, natural history studies and longitudinal follow up may be required.

Overlap between hypomyelinating leukodystrophies and complicated HSP

A remarkable feature of ENTPD1-related neurological disease is the unique pattern of hypomyelination seen in 14 of 18 affected individuals. White matter abnormalities have been observed in other complex HSPs, including SPG2 (OMIM# 312920), SPG5 (OMIM# 270800), SPG35 (OMIM# 612319), SPG44 (OMIM #613206), SPG50 (OMIM# 612936), SPG63 (OMIM#615686), and SPG75 (OMIM# 616680) and the disease spectrum of these disorders frequently overlaps with hypomyelinating leukodystrophies such as the prototype, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (OMIM# 312080)27; 28. Spastic paraplegia is a common manifestation of central nervous system (CNS) hypomyelination but also occurs in other white matter disorders, including multiple sclerosis and demyelinating leukodystrophies, e.g. adrenoleukodystrophy and cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis12; 29. In some cases, the allelic series of a single gene results in either HSP or hypomyelinating leukodystrophy as evidenced by SPG2 and the more severe Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, both of which result from mutations at the PLP1 locus30. To the best of our knowledge, persistent hypomyelination of the posterior limb of the internal capsule has not been described in hypomyelinating leukodystrophies nor HSP and thus may prove pathognomonic for ENTPD1-related neurological disease. It is a subtle neuroradiographic finding that may have an age-dependent penetrance and can be missed as illustrated by Family 17, being detected only upon secondary review. Thus, the frequency of hypomyelination within the cohort may be an underrepresentation of its true incidence.

Spectrum of pathogenic biallelic ENTPD1 variants

We identified nine previously unpublished variants, the majority of which are predicted likely damaging and to cause LoF. Additionally, a multinucleotide variant causing a single amino acid substitution, c.398_399delinsAA (p.Gly13Glu), and one splicing variant, c.574-6_574-3del, were uncovered. Double missense variants, a type of multi-nucleotide variant (MNV), are rare but occur due to replication error introduced by DNA polymerase zeta (pol-zeta) during DNA damage repair and translesion DNA synthesis31. Three recurrent variants were identified including c.574-6_574-3del found in families 5 (Brazilian, homozygous), 6 (Puerto Rican, compound heterozygous), and 9 (Portuguese, homozygous) and c.770_771del; p.(Gly257Glufs*18) in families 3 and 4 (both Brazilian, homozygous). The observation that c.574-6_574-3del and c.770_771del were found in the homozygous state in unrelated consanguineous families from countries with substantial Portuguese ancestry (Brazil and Portugal) may suggest these variants represent founder alleles from the Iberian peninsula homozygosed through clan genomics IBD or population/geographic isolation32,33. Alternatively, the de novo variant allele may be a recurrently derived new mutation in antecedent generations of each clan. Similarly, the stop gain variant c.1109T>A; p.(Leu370*) was found in three unrelated families from Persia and Poland consistent with a recurrent mutation.

Aberrant splicing in neurological disease

Given that the splicing variant c.574-6_574-3del was identified in multiple unrelated families, we hypothesized pathogenicity based on aberrant splicing and found that exon 6 skipping indeed occurs in a proband harboring this variant in the homozygous state (Fig. 5). ENTPD1 has 13 recognized splice variants of which four are protein coding34. The aberrant splice product observed in our studies has not been reported to occur in normal tissue34.

Aberrant splicing in neurological disease is well established. In the healthy cell precursor mRNA splicing removes intervening introns and joins exons in the nucleus before cytoplasmic export for translation. While some sequences are always included in constitutive splicing, others can be selectively included or excluded in a process called alternative splicing, which contributes to proteomic diversity is especially abundant during neurodevelopment35. When alternative splicing is disrupted due to variants affecting critical intronic sequences including consensus 5’ & 3’ splice acceptor/donor sites, exonic or intronic splice enhancers or silencers, polypyrimidine tracts, or branchpoint sequences, aberrant splicing occurs and can result in disease36. Other neurogenetic diseases arising from aberrant splicing include ataxia-telangiectasia, fascioscapulohumoral dystrophy, Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy, Neurofibromatosis Type 1, and Rett syndrome37. The identification of pathogenic splicing variants provides an opportunity for nucleic acid based molecular therapeutic intervention using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and/or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) molecules38.

Function of ENTPD1 in health and disease

ENTPD1, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (MIM*601752) is part of a group of nucleotide triphosphate dihydrolases involved in ATP hydrolysis and purine metabolism and signaling and is important in the central nervous system where it plays an essential role in neuronal activity39. ATP is stored in neuronal synaptic vesicles and glial cells together with classic neurotransmitters, e.g. GABA and glutamate, and is released by exocytosis upon neuronal stimulation40. High concentrations of ATP trigger neurotoxicity through the purinergic receptor P2X7 and are implicated in motor neuron diseases and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A41; 42. ENTPD1 plays an important role in the cell-surface catabolism of ATP (Fig. 6A). A previous study using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) reported that the LoF variant c.185T>G; p.(Leu62*) found in family 8 in this report affects ENTPD1 enzymatic function with impaired ATP and ADP hydrolysis, although no specific clinical details about the family were provided at the time43. Here, we provide evidence from flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry, two clinically accessible tests, that the previously reported impairment of ATP/ADP metabolism caused by the ENTPD1 variant c.185T>G is likely a consequence of the complete absence of ENTPD1 protein in vivo (span style=“font-family:’Times New Roman’; font-weight:bold”>Fig. 6E).

ENTPD1 is a highly glycosylated protein and alterations in glycosylation affect the protein’s electrophoretic mobility, stability and enzymatic activity44. Therefore, it is likely the overall reduction in ENTPD1 protein levels as well as the relative increase in the lower molecular weight species reflecting defective glycosylation in individuals P27 and P28 harboring the homozygous c.401T>G; p.(Met134Arg) variant that may reduce ENTPD1 stability and/or impair ATPase and ADPase activity. This impairment leads to an imbalance of extracellular ATP and adenosine and presumably disturbs purinergic neurotransmission and/or causes neurotoxicity as potential disease mechanism. Similarly, the LoF variant c.185T>C; p.(Leu62*) resulted in absence of ENTPD1 in the vasculature of the epi- and perineurium with possible implications for peripheral nerve health and function (Fig. 6G). Furthermore, an in vitro study using a cellular model of sympathetic neurons demonstrated that ENTPD1 modulates exocytotic and ischemic neurotransmitter release45 and targeted ‘knockout’ LoF Entpd1−/− mouse models exhibit a pro-epileptogenic phenotype46, although epilepsy was only seen in a small fraction of ENTPD1-related neurological disease cohort (2/31) to date. Given the important cellular function of ENTPD1 and its ubiquitous expression it is possible that impaired ENTPD1 function could have additional extra-CNS manifestations. In fact, flow cytometry from individuals with the LoF allele c.185T>C; p.(Leu62*) showed absence of ENTPD1 expression in lymphocytes and PMNs (Fig. 6F). While LoF Entpd1 mouse models exhibit impaired hemostasis and thromboregulation due to platelet dysfunction and hepatic insulin resistance47–50, these features were not observed within this cohort. It remains to be determined if individuals with ENTPD1-related neurological disease develop additional extra-CNS disease manifestations over time.

Treatment and development of therapeutics

The HSPs constitute a spectrum of progressive neurological disorders with supportive therapies, including physical therapy and stretching, but unfortunately no molecular interventions to ameliorate disease5. Pharmacologic intervention using baclofen and benzodiazepines can relieve spasticity and muscle spasms, respectively. A major challenge in therapeutic development stems from the diverse molecular pathways resulting from over 80 disease genes. Another challenge in the evaluation of potential therapeutics is the insidious, slow and progressive nature of the disease, which makes therapeutic endpoints and efficacy assessment challenging. Nevertheless, with current advances in genome medicine and evolving understanding of molecular disease etiology, therapeutic development targeting diverse molecular disease mechanisms are now feasible. Accurate and timely molecular diagnosis and natural history studies will greatly facilitate clinical trials. The known role of ENTPD1 in ATP breakdown and our experimental evidence of impaired ATP/ADP hydrolysis in patients with ENTPD1-related neurological disease suggests antagonism of the purinergic receptor P2X7 may be a worthwhile target for therapeutic intervention.

In conclusion, we establish ENTPD1 as the etiology of a complex neurodevelopmental disorder in the HSP spectrum characterized by intellectual disability, hypomyelination, and progressive spastic paraplegia. Allelic series studies and detailed phenotyping in rare neurological disease research can capture a more comprehensive spectrum of disease and define disease traits. Moreover, such information provides recurrence risk and prognostic information for family counseling, establishes pathophysiological mechanisms, provides neurobiological insights, and may ultimately lead to the development of novel interventional options for rare neurological disorders based on shared molecular features.

Supplementary Material

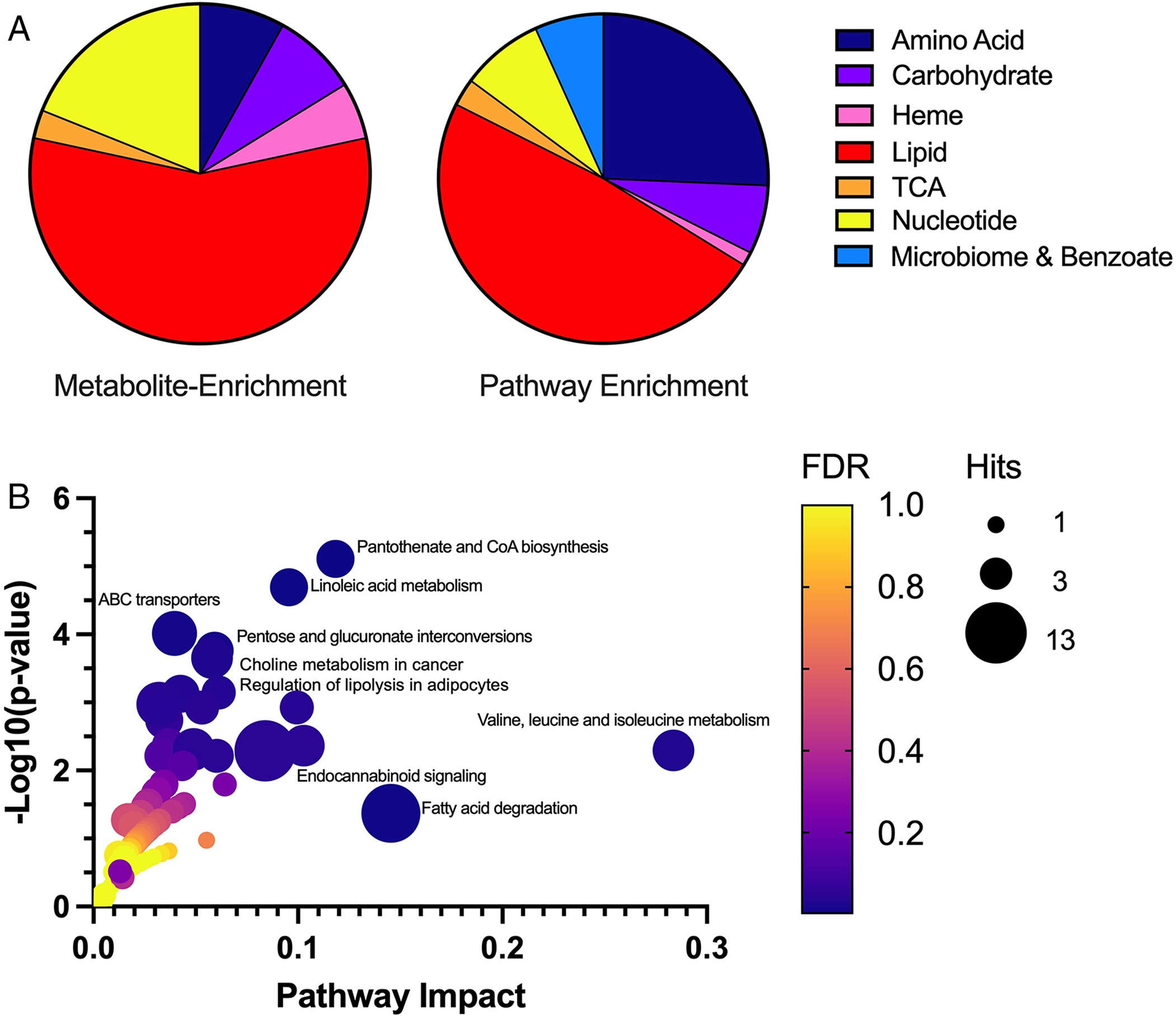

Figure 7.

ENTPD1 deficiency alters multiple metabolic pathways important for lipid and energy metabolism. (A) Metabolite enrichment (left) illustrates molecule distribution of specific perturbed metabolites altered in at least two thirds of tested individuals (n = 37). Pathway enrichment (right) illustrates altered molecules from the same metabolic pathways (n = 148). In pathway enrichment, molecules may or may not be identical between patient samples; however, molecules fall within the same metabolic pathway. The distribution of these molecules across all patient samples illustrates the broader impact of lipid and energy metabolism due to ENTPD1 deficiency. (B) Gene–metabolite disease pathway interaction is shown for significantly perturbed metabolites in plasma of patients with ENTPD1 deficiency. Metabolites assessed (n = 98) are limited to molecules mapped to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. The most significantly altered pathways (p < 0.05) are labeled. ABC = ATP-binding cassette; CoA = coenzyme A; TCA = tricarboxylic acid; FDR = false discovery rate.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families reported in this study for their willingness to contribute to the advancement of science and the understanding of rare neurological disease. Ms. Liat Ben Avi is thanked for her technical assistance.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the U.S. National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHBLI) to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (BHCMG, UM1 HG006542, J.R.L); NHGRI grant to Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center (U54HG003273 to R.A.G.), U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (R35NS105078 to J.R.L. and R01NS106298 to M.C.K.), Spastic Paraplegia Foundation (SPF) (to J.R.L.), and Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) (512848 to J.R.L.). The functional studies performed for Family 16 were supported by the Care4Rare Canada Consortium funded by Genome Canada and the Ontario Genomics Institute (OGI-147), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ontario Research Fund, Genome Alberta, Genome British Columbia, Genome Quebec, and Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundation. S.B. is supported by a Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation Career Development Award. D.M. was supported by a Medical Genetics Research Fellowship Program through the United States National Institute of Health (T32 GM007526-42). T.M. was supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation. D.P. is supported by a Clinical Research Training Scholarship in Neuromuscular Disease by the American Brain Foundation (ABF) and Muscle Study Group (MSG), and International Rett Syndrome Foundation (IRSF grant #3701-1). J.E.P. was supported by NHGRI K08 HG008986. D.G.C. is supported by NIH – Brain Disorders and Development Training Grant (T32 NS043124-19). A.E.M. is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) fellowship award (MFE-176616). J.A.M.S. is supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). V.M. was supported in part by the Karl Kahane Foundation. A.L. was supported in part by the Israeli MOH grant (#5914) and the Israeli MOH/ERA-Net (#4800).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests

J.R.L. has stock ownership in 23andMe, is a paid consultant for Regeneron Genetics Center, and is a co-inventor on multiple United States and European patents related to molecular diagnostics for inherited neuropathies, eye diseases, and bacterial genomic fingerprinting. The Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine receives revenue from clinical genetic testing conducted at Baylor Genetics (BG) Laboratories. M.C.K. is a paid consultant for PTC Therapeutics and Aeglea. Other authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Lupski JR, Liu P, Stankiewicz P, Carvalho CMB, and Posey JE (2020). Clinical genomics and contextualizing genome variation in the diagnostic laboratory. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 20, 995–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karaca E, Posey JE, Coban Akdemir Z, Pehlivan D, Harel T, Jhangiani SN, Bayram Y, Song X, Bahrambeigi V, Yuregir OO, et al. (2018). Phenotypic expansion illuminates multilocus pathogenic variation. Genet Med 20, 1528–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tadahiro Mitani SI, Gezdirici Alper, Gulec Elif Yilmaz, Punetha Jaya, Fatih Jawid M., Herman Isabella, Gulsen Akay Tayfun Haowei Du, Calame Daniel G., Ayaz Akif, Tos Tulay, Yesil Gozde, Aydin Hatip, Geckinli Bilgen, Elcioglu Nursel, Candan Sukru, Sezer Ozlem, Haktan Bagis Erdem Davut Gul, Yasar Emine, Koparir Erkan, Elmas Muhsin, Yesilbas Osman, Kilic Betul, Serdal Güngör Ahmet C. Ceylan, Bozdogan Sevcan, Ture Mehmet, Etlik Ozdal, Cicek Salih, Aslan Huseyin, Yalcintepe Sinem, Topcu Vehap, Ipek Zeynep, Bayram Yavuz, Grochowski Christopher M., Jolly Angad, Dawood Moez, Duan Ruizhi, Jhangiani Shalini N., Doddapaneni Harsha, Hu Jianhong, Muzny Donna M., Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics, Marafi Dana, Akdemir Zeynep Coban, Karaca Ender, Carvalho Claudia MBC, Gibbs Richard A., Posey Jennifer E., Lupski James R., and Pehlivan Davut. (2021). Evidence for a higher prevalence of oligogenic inheritance in neurodevelopmental disorders in the Turkish population. American Journal of Human Genetics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruano L, Melo C, Silva MC, and Coutinho P (2014). The global epidemiology of hereditary ataxia and spastic paraplegia: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Neuroepidemiology 42, 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackstone C (2018). Hereditary spastic paraplegia. Handb Clin Neurol 148, 633–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackstone C (2012). Cellular pathways of hereditary spastic paraplegia. Annu Rev Neurosci 35, 25–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posey JE, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Chong JX, Harel T, Jhangiani SN, Coban Akdemir ZH, Buyske S, Pehlivan D, Carvalho CMB, Baxter S, et al. (2019). Insights into genetics, human biology and disease gleaned from family based genomic studies. Genet Med 21, 798–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novarino G, Fenstermaker AG, Zaki MS, Hofree M, Silhavy JL, Heiberg AD, Abdellateef M, Rosti B, Scott E, Mansour L, et al. (2014). Exome sequencing links corticospinal motor neuron disease to common neurodegenerative disorders. Science 343, 506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiVincenzo C, Elzinga CD, Medeiros AC, Karbassi I, Jones JR, Evans MC, Braastad CD, Bishop CM, Jaremko M, Wang Z, et al. (2014). The allelic spectrum of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in over 17,000 individuals with neuropathy. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2, 522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas S, Proukakis C, Crosby A, and Warner TT (2008). Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical features and pathogenetic mechanisms. Lancet Neurol 7, 1127–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shribman S, Reid E, Crosby AH, Houlden H, and Warner TT (2019). Hereditary spastic paraplegia: from diagnosis to emerging therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol 18, 1136–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burguez D, Polese-Bonatto M, Scudeiro LAJ, Björkhem I, Schöls L, Jardim LB, Matte U, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Siebert M, and Saute JAM (2017). Clinical and molecular characterization of hereditary spastic paraplegias: A next-generation sequencing panel approach. J Neurol Sci 383, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schule R, Wiethoff S, Martus P, Karle KN, Otto S, Klebe S, Klimpe S, Gallenmuller C, Kurzwelly D, Henkel D, et al. (2016). Hereditary spastic paraplegia: Clinicogenetic lessons from 608 patients. Ann Neurol 79, 646–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boone PM, Liu P, Zhang F, Carvalho CM, Towne CF, Batish SD, and Lupski JR (2011). Alu-specific microhomology-mediated deletion of the final exon of SPAST in three unrelated subjects with hereditary spastic paraplegia. Genet Med 13, 582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamelona J, Crapoulet N, and Marrero A (2019). A new case of spastic paraplegia type 64 due to a missense mutation in the ENTPD1 gene. Hum Genome Var 6, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travaglini L, Aiello C, Stregapede F, D’Amico A, Alesi V, Ciolfi A, Bruselles A, Catteruccia M, Pizzi S, Zanni G, et al. (2018). The impact of next-generation sequencing on the diagnosis of pediatric-onset hereditary spastic paraplegias: new genotype-phenotype correlations for rare HSP-related genes. Neurogenetics 19, 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pashaei M, Davarzani A, Hajati R, Zamani B, Nafissi S, Larti F, Nilipour Y, Rohani M, and Alavi A (2021). Description of clinical features and genetic analysis of one ultra-rare (SPG64) and two common forms (SPG5A and SPG15) of hereditary spastic paraplegia families. J Neurogenet, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackstone C (2018). Converging cellular themes for the hereditary spastic paraplegias. Curr Opin Neurobiol 51, 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding AE (1993). Hereditary spastic paraplegias. Semin Neurol 13, 333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fink JK (2013). Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinico-pathologic features and emerging molecular mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 126, 307–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wohler E, Martin R, Griffith S, da S, Rodrigues E, Antonescu C, Posey JE, Coban-Akdemir Z, Jhangiani SN, Doheny KF, Lupski JR, Valle D, Hamosh A, Sobreira N. (2021). PhenoDB, GeneMatcher and VariantMatcher, tools for analysis and sharing of sequence data. Orphanet J Rare Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhler S, Vasilevsky NA, Engelstad M, Foster E, McMurry J, Aymé S, Baynam G, Bello SM, Boerkoel CF, Boycott KM, et al. (2017). The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res 45, D865–d876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karaca E, Harel T, Pehlivan D, Jhangiani SN, Gambin T, Coban Akdemir Z, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Erdin S, Bayram Y, Campbell IM, et al. (2015). Genes that Affect Brain Structure and Function Identified by Rare Variant Analyses of Mendelian Neurologic Disease. Neuron 88, 499–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen AW, Murugan M, Li H, Khayat MM, Wang L, Rosenfeld J, Andrews BK, Jhangiani SN, Coban Akdemir ZH, Sedlazeck FJ, et al. (2019). A Genocentric Approach to Discovery of Mendelian Disorders. Am J Hum Genet 105, 974–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue K, Khajavi M, Ohyama T, Hirabayashi S, Wilson J, Reggin JD, Mancias P, Butler IJ, Wilkinson MF, Wegner M, et al. (2004). Molecular mechanism for distinct neurological phenotypes conveyed by allelic truncating mutations. Nat Genet 36, 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Zemojtel T, Abedini SS, Chen W, Hosseini M, Behjati F, Haas S, Jamali P, et al. (2011). Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature 478, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hobson GM, and Garbern JY (2012). Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease 1, and related hypomyelinating disorders. Semin Neurol 32, 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calame DG, Hainlen M, Takacs D, Ferrante L, Pence K, Emrick LT, and Chao HT (2021). EIF2AK2-related Neurodevelopmental Disorder With Leukoencephalopathy, Developmental Delay, and Episodic Neurologic Regression Mimics Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease. Neurol Genet 7, e539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saute JA, Giugliani R, Merkens LS, Chiang JP, DeBarber AE, and de Souza CF (2015). Look carefully to the heels! A potentially treatable cause of spastic paraplegia. J Inherit Metab Dis 38, 363–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue K (2005). PLP1-related inherited dysmyelinating disorders: Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease and spastic paraplegia type 2. Neurogenetics 6, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q, Pierce-Hoffman E, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Francioli LC, Gauthier LD, Hill AJ, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Karczewski KJ, and MacArthur DG (2020). Landscape of multi-nucleotide variants in 125,748 human exomes and 15,708 genomes. Nat Commun 11, 2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Yesil G, Nistala H, Gezdirici A, Bayram Y, Nannuru KC, Pehlivan D, Yuan B, Jimenez J, Sahin Y, et al. (2020). Functional biology of the Steel syndrome founder allele and evidence for clan genomics derivation of COL27A1 pathogenic alleles worldwide. Eur J Hum Genet 28, 1243–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lupski JR, Belmont JW, Boerwinkle E, and Gibbs RA (2011). Clan genomics and the complex architecture of human disease. Cell 147, 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howe KL, Achuthan P, Allen J, Allen J, Alvarez-Jarreta J, Amode MR, Armean IM, Azov AG, Bennett R, Bhai J, et al. (2021). Ensembl 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D884–d891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ule J, and Blencowe BJ (2019). Alternative Splicing Regulatory Networks: Functions, Mechanisms, and Evolution. Mol Cell 76, 329–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng D, and Xie J (2013). Aberrant splicing in neurological diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 4, 631–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Licatalosi DD, and Darnell RB (2006). Splicing regulation in neurologic disease. Neuron 52, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rinaldi C, and Wood MJA (2018). Antisense oligonucleotides: the next frontier for treatment of neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 14, 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann H (2006). Ectonucleotidases in the nervous system. Novartis Found Symp 276, 113–128; discussion 128-130, 233-117, 275-181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pankratov Y, Lalo U, Verkhratsky A, and North RA (2006). Vesicular release of ATP at central synapses. Pflugers Arch 452, 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cieślak M, Roszek K, and Wujak M (2019). Purinergic implication in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-from pathological mechanisms to therapeutic perspectives. Purinergic Signal 15, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nobbio L, Sturla L, Fiorese F, Usai C, Basile G, Moreschi I, Benvenuto F, Zocchi E, De Flora A, Schenone A, et al. (2009). P2X7-mediated increased intracellular calcium causes functional derangement in Schwann cells from rats with CMT1A neuropathy. J Biol Chem 284, 23146–23158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nardi-Schreiber A, Sapir G, Gamliel A, Kakhlon O, Sosna J, Gomori JM, Meiner V, Lossos A, and Katz-Brull R (2017). Defective ATP breakdown activity related to an ENTPD1 gene mutation demonstrated using (31)P NMR spectroscopy. Chem Commun (Camb) 53, 9121–9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu JJ, Choi LE, and Guidotti G (2005). N-linked oligosaccharides affect the enzymatic activity of CD39: diverse interactions between seven N-linked glycosylation sites. Mol Biol Cell 16, 1661–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corti F, Olson KE, Marcus AJ, and Levi R (2011). The expression level of ecto-NTP diphosphohydrolase1/CD39 modulates exocytotic and ischemic release of neurotransmitters in a cellular model of sympathetic neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 337, 524–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lanser AJ, Rezende RM, Rubino S, Lorello PJ, Donnelly DJ, Xu H, Lau LA, Dulla CG, Caldarone BJ, Robson SC, et al. (2017). Disruption of the ATP/adenosine balance in CD39(−/−) mice is associated with handling-induced seizures. Immunology 152, 589–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enjyoji K, Sévigny J, Lin Y, Frenette PS, Christie PD, Esch JS 2nd, Imai M, Edelberg JM, Rayburn H, Lech M., et al. (1999). Targeted disruption of cd39/ATP diphosphohydrolase results in disordered hemostasis and thromboregulation. Nat Med 5, 1010–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwyer KM, Mysore TB, Crikis S, Robson SC, Nandurkar H, Cowan PJ, and D’Apice AJ (2006). The transgenic expression of human CD39 on murine islets inhibits clotting of human blood. Transplantation 82, 428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dwyer KM, Robson SC, Nandurkar HH, Campbell DJ, Gock H, Murray-Segal LJ, Fisicaro N, Mysore TB, Kaczmarek E, Cowan PJ, et al. (2004). Thromboregulatory manifestations in human CD39 transgenic mice and the implications for thrombotic disease and transplantation. J Clin Invest 113, 1440–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enjyoji K, Kotani K, Thukral C, Blumel B, Sun X, Wu Y, Imai M, Friedman D, Csizmadia E, Bleibel W, et al. (2008). Deletion of cd39/entpd1 results in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 57, 2311–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.