ABSTRACT

Changes in the gut microbiota have been linked to metabolic endotoxemia as a contributing mechanism in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Although identifying specific microbial taxa associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes remains difficult, certain bacteria may play an important role in initiating metabolic inflammation during disease development. The enrichment of the family Enterobacteriaceae, largely represented by Escherichia coli, induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) has been correlated with impaired glucose homeostasis; however, whether the enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae in a complex gut microbial community in response to an HFD contributes to metabolic disease has not been established. To investigate whether the expansion of Enterobacteriaceae amplifies HFD-induced metabolic disease, a tractable mouse model with the presence or absence of a commensal E. coli strain was established. With an HFD treatment, but not a standard-chow diet, the presence of E. coli significantly increased body weight and adiposity and induced impaired glucose tolerance. In addition, E. coli colonization led to increased inflammation in liver and adipose and intestinal tissue under an HFD regimen. With a modest effect on gut microbial composition, E. coli colonization resulted in significant changes in the predicted functional potential of microbial communities. The results demonstrated the role of commensal E. coli in glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism in response to an HFD, indicating contributions of commensal bacteria to the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes. The findings of this research identified a targetable subset of the microbiota in the treatment of people with metabolic inflammation.

IMPORTANCE Although identifying specific microbial taxa associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes remains difficult, certain bacteria may play an important role in initiating metabolic inflammation during disease development. Here, we used a mouse model distinguishable by the presence or absence of a commensal Escherichia coli strain in combination with a high-fat diet challenge to investigate the impact of E. coli on host metabolic outcomes. This is the first study to show that the addition of a single bacterial species to an animal already colonized with a complex microbial community can increase severity of metabolic outcomes. This study is of interest to a wide group of researchers because it provides compelling evidence to target the gut microbiota for therapeutic purposes by which personalized medicines can be made for treating metabolic inflammation. The study also provides an explanation for variability in studies investigating host metabolic outcomes and immune response to diet interventions.

KEYWORDS: commensal Escherichia coli, obesity, type 2 diabetes, high-fat diet, metabolic inflammation

INTRODUCTION

The gut microbiota has been identified as a contributing factor to obesity and associated metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes and its precursor, insulin resistance (IR) (1, 2). Several mechanisms have been proposed through which changes in the gut microbiota influence host body weight regulation and glucose homeostasis (3–5). One of the most compelling mechanisms is that the gut microbiota induces chronic low-grade inflammation in multiple organs in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes (6, 7). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), the major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, have been considered an established factor in inducing such an inflammatory response (7–9). This is supported by the fact that the severity of metabolic disease induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) was drastically attenuated in animal models where the host was unable to respond to LPS (10).

It should be noted that the LPS structure varies among bacterial species, which links to different immunogenicity and host outcomes (11). For example, Bacteroides species in the gut produced a distinct form of LPS in structure and function compared with LPS from Escherichia coli, which exerted distinct immune-stimulatory responses (12, 13). Therefore, variations in gut microbial composition might contribute to metabolic inflammation to different extents during the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Although identifying a specific taxonomic signal associated with the obesity phenotype remains difficult due to inconsistencies across studies and large diversities of microbiome compositions (14, 15), accounting for the functional diversity of microbial molecules such as LPS allows for recognition of select bacteria and host factors driving the inflammatory processes.

Compared with the phylum Bacteroidetes, the family Enterobacteriaceae, and in particular the commensal E. coli, has been linked to stronger immunostimulatory properties and endotoxin activities associated with obesity and insulin resistance (16, 17). Increased abundance of commensal E. coli has been a common observation in metabolically unhealthy patients and individuals with excessive weight gain (16, 18). It is noteworthy that an overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae has been considered a consequence of intestinal inflammation provoked by an HFD treatment which supports the growth of aerotolerant bacteria (19). However, colonizing germfree mice with an Enterobacter strain induced systemic inflammation and excessive fat accumulation in response to an HFD treatment, indicating a causal relationship between the Enterobacteriaceae member and the pathogenesis of obesity (20).

To date, research has been conducted in monocolonized mouse models to demonstrate a direct causal effect of Enterobacteriaceae members on obesity phenotypes and glucose metabolism (7, 20). However, in monocolonization studies, Enterobacteriaceae species colonized the mouse gut, reaching a density of 1010 to 1012 CFU/g feces, whereas conventional mice typically harbor 104 to 106 CFU/g feces of these species (7, 20, 21). Therefore, with the robust colonization of Enterobacteriaceae species in the gut due to niche availability, monocolonization studies may not reflect the effects of the species on host metabolism as commensals, which also limited interactions between the microorganism and the complex microbial community. Using our established E. coli free-mouse model (21), we demonstrated the role of commensal E. coli in glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism in response to dietary treatment.

RESULTS

Commensal E. coli increased body weight and adiposity after HFD challenge.

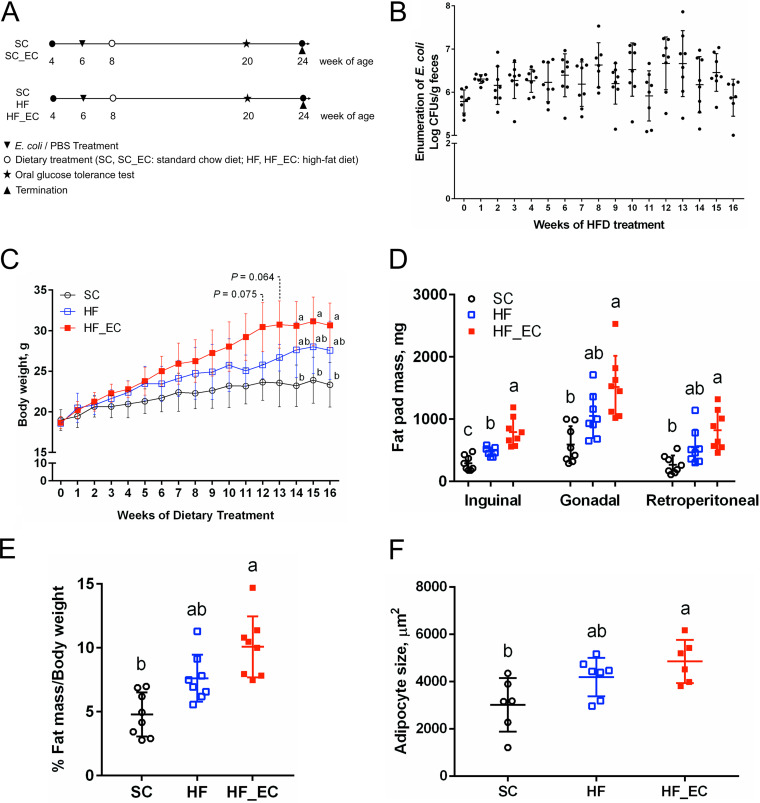

Mice were successfully and stably colonized by the commensal E. coli isolate LE, whose levels ranged from 1.30 × 105 to 2.14 × 106 CFU/g feces and did not change throughout 16 weeks of standard-chow SC diet treatment (P = 0.883) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). In contrast, the HFD induced a 0.8-log-CFU/g increase in fecal E. coli (Fig. 1B). Body weights were comparable between the standard-chow treated group (SC) group and the group fed the standard-chow with E. coli colonization (SC_EC group) (P = 0.546) (Fig. S1B), indicating that E. coli colonization did not affect body weight changes in the setting of a standard-chow diet. Sixteen weeks of an HFD treatment significantly increased body weight of mice receiving the HFD with E. coli treatment (HF_EC mice) compared with SC mice (30.7 ± 2.7 g versus 23.3 ± 2.7 g; P = 0.028) (Fig. 1C). No significant difference was observed in caloric intake between SC, HFD treatment without E. coli colonization (HF), and HF_EC groups; however, HFD-treated mice tended to have higher energy input than SC mice (Fig. S1C).

FIG 1.

Commensal E. coli increased body weight and adipose tissue mass induced by a high-fat diet. (A) Experimental protocol. (B) Enumeration of fecal E. coli during 16 weeks of HFD treatment. (C) Body weights of SC, HF, and HF_EC mice in 16 weeks of dietary treatment. (D) Fat pad mass after 16 weeks of dietary treatments. (E) Percentage of white adipose tissue mass relative to body weight after 16 weeks of dietary treatment. (F) Size of adipocytes in gonadal fat after 16 weeks of dietary treatment. (A to E) For all treatment, n = 8. (F) For all treatment, n = 6 or 7. Data are means and standard deviations (SD). Means that do not share a letter are significantly different. α = 0.05.

In mice fed an HFD, notable differences were observed in major white adipose tissue (WAT) pad weight. Specifically, compared with SC mice, HF_EC mice developed larger gonadal (P < 0.001) and retroperitoneal (P = 0.001) (Fig. 1D) depots; however, there was no significant difference in visceral WAT pads between HF and SC mice (P = 0.059) (Fig. 1D). In addition, the presence of E. coli further increased the inguinal fat mass in response to the HFD treatment (P = 0.002) (Fig. 1D). When expressed as a percentage of total body weight, the proportion of WAT was significantly higher in HF_EC mice than in SC mice, as measured by the combined weight of fat depots (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1E). Histological analyses of gonadal WAT revealed that HF_EC mice had larger adipocytes than SC mice (P = 0.006) (Fig. 1F). No changes in the weight of liver and muscle were observed among groups, indicating that the increased body weight in HF_EC mice was largely attributable to adipose tissue mass. Consistent with the comparable body weight, no difference was detected in WAT pad, liver, and muscle weights between SC and SC_EC mice (Fig. S1D and E).

The presence of commensal E. coli aggravated impaired glucose tolerance induced by an HFD.

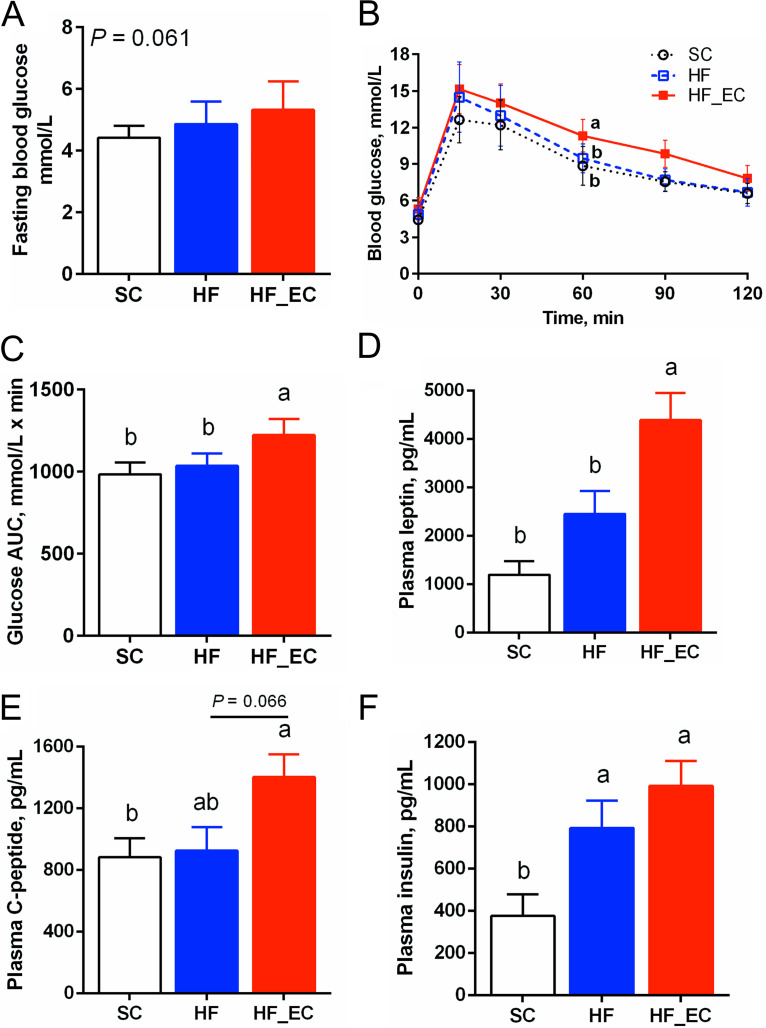

In the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at 12 weeks, HF_EC mice tended to show higher levels of fasting glucose than SC mice (P = 0.058) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no difference was observed in fasting blood glucose levels between HF and SC mice (P = 0.450). HF_EC mice displayed impaired glucose disposal during the OGTT (Fig. 2B) and exhibited 19.5% and 18.2% higher areas under the curve (AUC) for glucose than SC and HF mice, respectively (Fig. 2C), indicating that the presence of commensal E. coli exacerbates the HFD-induced glucose intolerance. No difference in the rate of glucose clearance from circulation was detected between SC and HF mice (Fig. 2B and C). When mice were fed a standard-chow diet, there was no difference in fasting blood glucose levels or glucose disposal capacity between SC and SC_EC mice, indicating an interaction between commensal E. coli and HFD in altering glucose and insulin homeostasis (Fig. S1F to H).

FIG 2.

Commensal E. coli aggravated impaired glucose tolerance induced by an HFD treatment. (A) Fasting blood glucose levels. (B) Glucose curve in 120 min of an oral glucose tolerance test. (C) Area under the curve of oral glucose tolerance test. (D to F) Plasma levels of leptin, C peptide, and insulin after 16 weeks of dietary treatment. For all treatments, n = 8. Data are means and SD. Means that do not share a letter are significantly different. α = 0.05.

Plasma leptin, an adipocyte-derived hormone, was higher in HF_EC mice than in SC and HF mice, consistent with the increased adiposity in HF_EC mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2D). In addition, plasma connecting peptide (C-peptide) was elevated in HF_EC mice compared with SC mice (P = 0.043) (Fig. 2E). The HFD increased plasma insulin levels; however, the presence of commensal E. coli did not significantly affect plasma insulin (P = 0.237) (Fig. 2F). Plasma levels of amylin, ghrelin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), glucagon, pancreatic polypeptide (PP), peptide YY (PYY), and resistin were not different among the SC, HF, and HF_EC groups (Table S1). No significant changes were detected in circulating metabolic hormones between SC and SC_EC mice (Table S2).

Commensal E. coli, in combination with an HFD, enhanced lipid accumulation and inflammation in liver and adipose tissue.

The impaired insulin sensitivity induced by an HFD treatment is frequently associated with pathological liver and adipose tissue changes, which plays a crucial role in maintaining blood glucose homeostasis. As expected, mice that received the HFD treatment for 16 weeks developed hepatic steatosis, as reflected by a notable accumulation of lipid droplets in the liver (Fig. S2A). HF_EC mice had a markedly greater area of all macrovacuolar structures and Feret y diameter compared with SC and HF mice (Table 1), indicating an enhanced macrovacuolar fatty change in the liver of HF_EC mice. In addition, the HFD treatment induced changes in microvacuolar lipid droplets, including increased vacuole count and area (Table S3). Interestingly, the presence of commensal E. coli increased Feret diameters of microvacuoles, suggesting enlarged hepatic microvacuoles in HF_EC mice (Table S3). No macrovacuoles were detected in the SC treatment arm, and microvacuoles in the liver of SC and SC_EC mice were comparable (Table S4).

TABLE 1.

Hepatic lipid macrovacuoles (diameter, 26 to 1,000 μm)a

| Parameter | SC |

HF |

HF_EC |

P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | ||

| Fat vacuole count | 0.57b | 0.30 | 7.67ab | 5.89 | 470.40a | 103.60 | <0.001 |

| Total area (μm2) | 60.60b | 15.25 | 339.30b | 237.70 | 33,638.00a | 9,134.00 | <0.001 |

| Fractional area (%) | 0.06b | 0.02 | 1.02ab | 0.54 | 3.47a | 0.94 | 0.009 |

| Avg size (μm2) | 46.76 | 10.66 | 46.16 | 5.18 | 65.78 | 7.39 | 0.105 |

| Perimeter (μm) | 31.08 | 3.34 | 27.58 | 1.29 | 31.40 | 1.55 | 0.220 |

| Circularityc | 0.59b | 0.03 | 0.74a | 0.02 | 0.78b | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Solidityd | 0.77b | 0.05 | 0.84a | 0.01 | 0.87a | 0.01 | 0.010 |

| Feret diam (μm) | 11.57 | 0.66 | 9.94 | 0.44 | 11.04 | 0.49 | 0.127 |

| Feret x diam (μm) | 125.30b | 53.05 | 559.80ab | 132.50 | 983.00a | 26.06 | 0.002 |

| Feret y diam (μm) | 186.30c | 82.95 | 411.90b | 75.65 | 750.30a | 19.66 | <0.001 |

| Feret angle (°) | 83.29 | 36.19 | 97.48 | 10.97 | 92.26 | 3.88 | 0.805 |

| Minimum Feret diam (μm) | 6.83 | 0.56 | 7.00 | 0.37 | 8.30 | 0.40 | 0.052 |

SC, standard-chow diet (n = 3; not detected, n = 4); HF, high-fat diet (n = 7; not detected, n = 1); HF_EC, high-fat diet with E. coli (n = 7). Means that do not share a letter are significantly different. α = 0.05.

Boldface indicates statistical significance.

The circularity is defined by the formula 4π *area/perimeter2), ranging from 0 to 1. A value of 1.0 indicates a perfect circle.

The solidity measures the density of an object, which is a pure value between 0 and 1. It is defined as area/convex area. The convex area of an object is the area of the convex hull that encloses the object.

HF_EC mice showed the highest hepatic triglyceride (TG) content among groups, consistent with histological changes in the liver (Fig. S2B). However, plasma TG levels were not different among SC, HF, and HF_EC mice (P = 0.400) (Fig. S2B). The HFD treatment increased total cholesterol levels in liver and plasma; however, no difference was observed between HF and HF_EC groups (Fig. S2C). There was no difference in cholesterol or TG levels in plasma and liver between SC and SC_EC mice (Fig. S2D and E).

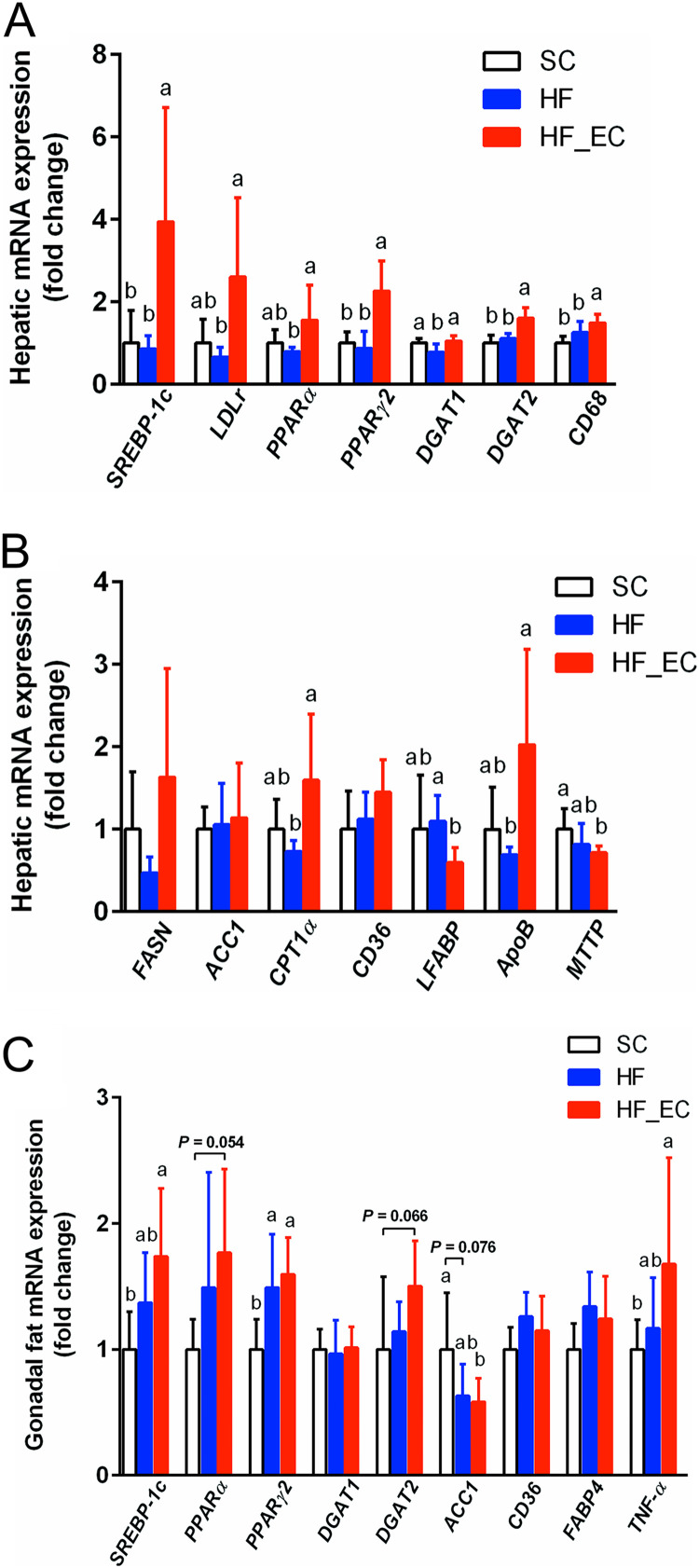

Increased hepatic lipid accumulation in HF_EC mice was associated with changes in lipogenic genes in the liver. Specifically, HF_EC mice showed upregulation of genes encoding sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2 (PPARγ2), and acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA):diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2) compared with SC and HF mice (Fig. 3A). Hepatic genes involved in lipogenesis (fatty acid synthase [FASN]), fatty acid oxidation (carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1α [CPT1α]), fatty acid uptake (liver fatty acid binding protein [LFABP]), and very-low-density-lipoprotein secretion (apolipoprotein B [ApoB] and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein [MTTP]) were altered in the HF_EC group, indicating an impaired hepatic lipid metabolism resulting from commensal E. coli colonization (Fig. 3B). In addition, the expression of the macrophage marker gene CD68 was higher in the HF_EC liver, suggesting enhanced hepatic inflammation (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Commensal E. coli, in combination with an HFD, enhanced lipid accumulation and inflammation in liver and adipose tissue. (A and B) Hepatic lipogenic-gene expression in SC, HF, and HF_EC mice after 16 weeks of dietary treatment, including genes involved in lipogenesis (FASN and ACC1), fatty acid oxidation (CPT1α), fatty acid uptake (CD36 and LFABP), and VLDL secretion (ApoB and MTTP). (C) Lipogenic-gene and inflammatory-gene expression in the gonadal fat of SC, HF, and HF_EC mice after 16 weeks of dietary treatment. For all treatment, n = 8. Data are means and SD. Means that do not share a letter are significantly different. α = 0.05. Bar charts without letters have no observed statistical difference among treatment groups.

Consistent with increased adipose tissue mass in HF_EC mice, gene expression of adiposity markers and lipid-metabolizing mediators, including SREBP-1c, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), and PPARγ2, were upregulated in gonadal fat of HF_EC mice compared with SC and HF mice (Fig. 3C). The gene DGAT2, involved in TG synthesis, tended to be higher in HF_EC mice than SC mice (P = 0.073). Furthermore, the mRNA expression of TNF-α was higher in the gonadal fat of HF_EC mice than in SC mice (P = 0.011) (Fig. 3C). These results suggested that the presence of commensal E. coli promoted the lipid load and low-grade chronic inflammation in adipose tissue in response to HFD treatment.

It is worth noting that an increased level in another known proinflammatory mediator, LPS-binding protein (LBP), was observed in plasma samples from HFD-treated mice compared with samples from SC mice (Fig. S3A). As a surrogate marker for antigen load derived from gut microbes, LBP showed positive correlations with plasma levels of leptin and insulin (Fig. S3B and C).

Colonization of commensal E. coli altered gut microbial communities.

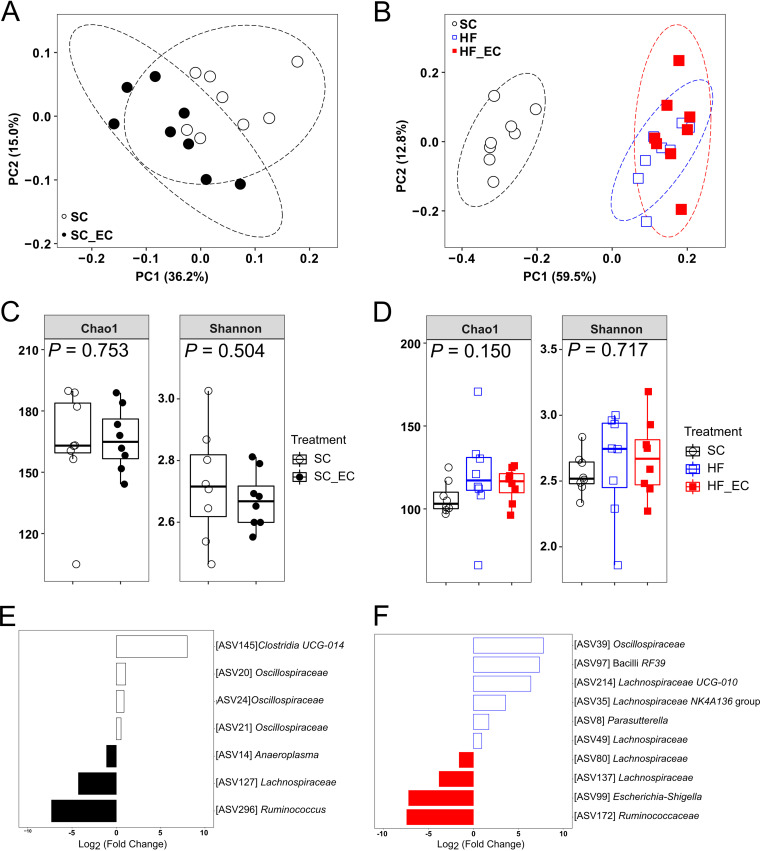

Although the differences were modest, community structures of colonic microbiota were significantly different between SC and SC_EC mice (permutational multivariate analysis of variance [PERMANOVA], P = 0.012) (Fig. 4A) and between HF and HF_EC mice (R2 = 0.164; adjusted P = 0.033) (Fig. 4B). Dietary type performed as a major driver in shifting colonic microbial communities as reflected by a clear separation between SC- and HFD-treated mice (F = 17.361; R2 = 0.623; P = 0.003) (Fig. 4B). The significant impact of dietary type on community structures was consistently detected in the microbiota of the ileum and cecum (Fig. S4A and B). The modulatory effect of diets on gut microbial communities matched altered fecal short-chain-fatty-acid (SCFA) profiles, as reflected by significantly reduced levels of propionate, butyrate, and valerate but increased levels of caproate and isobutyrate in HFD-treated groups compared with the SC group (Table S6). However, the presence of the E. coli strain did not significantly impact SCFA profiles compared with those in HF mice (Table S5).

FIG 4.

Colonization of commensal E. coli altered gut microbial communities. (A and B) PCoA plots of bacterial communities based on a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix. Each point represents an individual mouse. (C and D) Alpha diversity indices (Chao1 and Shannon) of bacterial communities. The ASV table was rarefied to even depth (21,059 and 23,567 reads/sample for panels C and D, respectively). Data are presented as box plots, where the boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentiles and the lines within the boxes represent the medians. (E and F) DESeq2 analysis results indicating the fold change of amplicon sequencing variants in SC fecal bacterial communities relative to SC_EC mice (E) and HF fecal bacterial communities relative to HF_EC mice (F) (FDR-adjusted P < 0.05). For all treatment groups, n = 8. Means that do not share a letter are significantly different. α = 0.05.

No differences were detected in alpha diversity indices between SC and SC_EC mice (P = 0.834) (Fig. 4C). HF mice tended to have higher Chao1 index values than SC mice in the colonic microbiota (P = 0.066) (Fig. 4D). However, no difference in Shannon index values calculated from the colonic microbial communities was observed between SC, HF, and HF_EC groups (P = 0.150) (Fig. 4D). Ileal microbial communities from HFD-treated groups exhibited greater Chao1 (P < 0.001) and Shannon (P = 0.003) indices than those from SC mice (Fig. S4C). Both alpha diversity indices calculated from cecal microbial communities were not affected by treatment (Fig. S4D).

The DESeq2 analysis of ASVs between SC and SC_EC groups as well as HF and HF_EC groups revealed modest but consistent changes in response to E. coli colonization along the gastrointestinal tract. This included increased Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae and decreased Oscillospiraceae (Fig. 4E and F; Fig. S4E and F).

In accordance with diet being the major driver of differences in beta diversity, multiple ASVs were altered in HFD-treated groups (Fig. S5A). In general, HFD consumption resulted in an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in HFD-treated mice (0.27, 0.54, and 0.67 for SC, HF, and HF_EC, respectively). Specifically, the genus Alistipes, which belongs to the phylum Bacteroidetes, was reduced at all intestinal sites, whereas members of the families Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Peptostreptococcaceae were increased in HF and HF_EC mice. The genus Akkermansia was significantly enriched in the cecum and colon of HF and HF_EC mice. These results indicated that dietary type played a greater role in shaping gut microbial communities, whereas E. coli colonization impacted the microbial profile to a lesser extent.

Functional predictions identified 250 differentially present MetaCyc pathways between HF and HF_EC colonic microbiota, suggesting that commensal E. coli may largely contribute to gut microbial functional changes in the context of the HFD treatment. Principal-component analysis of pathways and enzymes showed clear separations between HF and HF_EC groups (Fig. S5B and C). The largest significant differences were in the superpathway of amine and polyamine biosynthesis, the superpathway of l-phenylalanine and l-tyrosine biosynthesis, fucose and sucrose degradation, LPS biosynthesis, and enterobactin biosynthesis (Fig. S5D).

Commensal E. coli induced elevated levels of colonic inflammation under HFD challenge.

Sixteen weeks of HFD significantly enhanced colonic inflammation as indicated by elevated levels of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and IL-12p40 (Table S6). However, the presence of commensal E. coli, in the context of the HFD treatment, further influenced the colonic cytokine/chemokine profiles. For instance, HF_EC mice exhibited the highest level of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-12p40, IL-17, and keratinocyte chemoattractant among the treatment groups. In addition, levels of colonic IL-22 (P = 0.054), IL-6 (P = 0.073), and MIP-2 (P = 0.084) in HF_EC mice tended to be higher than those in SC mice, indicating an enhanced colonic inflammation induced by the colonization of commensal E. coli in the context of HFD.

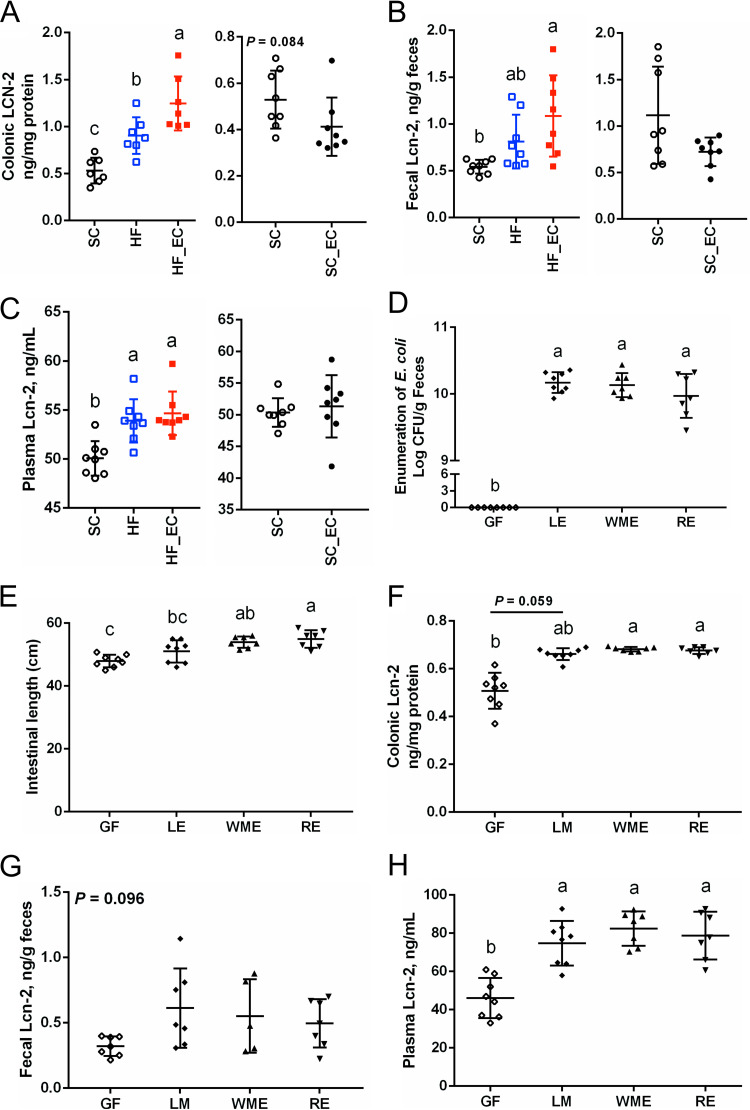

The biomarker of intestinal inflammation lipocalin-2 (Lcn-2) was altered by HFD feeding and the presence of commensal E. coli. Levels of colonic Lcn-2 in HF_EC mice were higher than in SC (P < 0.001) and HF (P = 0.010) mice. Conversely, SC_EC mice did not induce an increased secretion of colonic Lcn-2, indicating the requirement for an interaction between HFD and E. coli (Fig. 5A). The fecal Lcn-2 level in HF_EC mice was increased compared with that in SC mice (P = 0.004) (Fig. 5B). In addition, among treatment groups, HF_EC mice had the highest level of plasma Lcn-2, which tended to show a positive correlation with plasma levels of LBP (Fig. S3D; Fig. 5C). In the context of the standard-chow diet, the presence of commensal E. coli showed a minimal impact on fecal and plasma Lcn-2 levels (Fig. 5B and C).

FIG 5.

Commensal E. coli enhanced colonic inflammation under an HFD challenge. Lcn-2 levels in (A) colon, (B) feces, and (C) plasma after 16 weeks of dietary treatment (n = 7 or 8). (D) Enumeration of fecal E. coli strains (LE, WME, and RE) in monocolonization studies (n = 7 or 8). (E) Intestinal lengths of germfree mice and mice monocolonized with E. coli strains. (F to H) Lcn-2 levels in (F) colon, (G) feces, and (H) plasma of mice from monocolonization studies (n = 5 to 8). Data are means and SD. Means that do not share a letter are significantly different. α = 0.05.

To investigate if the observed colonic inflammation as indicated by Lcn-2 levels is due to the particular strain of E. coli, monocolonization of germfree (GF) mice using different commensal E. coli isolates were conducted. All three commensal E. coli strains stably colonized mouse intestine at a similar level and reached an average value of (1.40 ± 0.64) × 1010 CFU/g feces (mean ± standard deviation) (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the monocolonization by commensal E. coli strains increased the total length of intestine compared with that in GF mice (Fig. 5E). Mice monocolonized with different commensal E. coli strains for 2 weeks exhibited higher colonic Lcn-2 levels than the GF group (Fig. 5F). Fecal Lcn-2 levels in E. coli-colonized mice were numerically higher than those in GF mice, although the difference failed to reach statistical significance (Fig. 5G). However, E. coli-treated mice had elevated plasma Lcn-2 levels, indicating that the stimulation of Lcn-2 secretion by commensal E. coli was not a strain-specific phenomenon (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5H).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, a tractable mouse model was successfully established by adding a single bacterium to a complex microbial ecosystem to investigate the effect of commensal E. coli on metabolic outcomes and microbial interactions in the context of HFD. The results showed that the presence of commensal E. coli exacerbated HFD-induced impairment of glucose metabolism.

Even after 16 weeks of HFD, HF mice failed to show significant increases in body weight compared with SC mice. This was consistent with a previous study that reported a significance only after 27 weeks of an HFD in female C57BL/6J mice (22). However, the presence of commensal E. coli in combination with HFD led to a significant body weight gain, promoted adipogenesis in adipose and liver tissues, and reduced glucose tolerance. In addition, the fat accretion and the concomitant increase in plasma leptin level, which was correlated with plasma insulin and C-peptide levels, were observed in HF_EC mice, indicating a pronounced impairment of leptin action resulting from E. coli colonization and HFD treatment (23, 24).

HF_EC mice showed hepatic macrovacuolar steatosis, with large intracytoplasmic lipid vacuoles displacing the nucleus to the periphery of cells, as reflected by greater vacuolar area than in SC and HF mice. Hepatic lipid metabolism is complex and dynamic with multiple biological functions, including lipogenesis, fatty acid uptake, fatty acid oxidation, and secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). Increased expression of transcriptional factor genes SREBP-1c, PPARγ2, and DGAT2 in HF_EC mice was consistent with their role in regulating de novo lipogenesis and the development of steatosis (25, 26). The elevated expression of genes involved in lipid oxidation and VLDL secretion, such as CPT1α and ApoB, suggested enhanced lipid disposal in the liver of HF_EC mice. Therefore, HF_EC mice exhibited altered hepatic lipid metabolism with enhanced de novo fatty acid synthesis and lipid removal; however, the increases in disposal were likely insufficient to compensate for increases in synthesis.

A state of low-grade inflammation in various tissues, including the hypothalamus, adipose tissue, and liver, is involved in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes (27–29). HFD consumption could lead to enhanced LPS translocations into the circulation, triggering adipose inflammation, and impaired insulin and leptin actions (6). In the current study, an increased expression of TNF-α in adipose tissue and CD68 in liver was seen only in the presence of E. coli in combination with HFD, indicating that commensal E. coli was required to initiate this inflammatory response induced by the HFD.

An altered ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes was observed in HFD-treated groups, consistent with previous reports (30–32). However, the absence of metabolic change in HF mice suggested that the shift from Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes was not a main driver of disease phenotype, consistent with a meta-analysis of human studies (14). Although the presence of commensal E. coli had minimal effects on microbial composition, it resulted in significant changes in the predicted functional potential of microbial communities. It is possible that the colonization of the commensal E. coli isolate led to other strain-level differences in the gut microbiota that were not detected by the 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis. No significant impact of commensal E. coli on fecal SCFA profiles was observed, suggesting other potential mechanisms underlying the impaired glucose metabolism and enhanced metabolic inflammation in HF_EC mice.

Interestingly, HFD-treated mice tended to show higher plasma LBP levels, which were comparable between HF and HF_EC mice. With an ability to bind a variety of LPS chemotypes, LBP could act as a marker for antigen load derived from gut bacteria (33). It is likely that, although similar levels of circulating microbial antigens were detected, particular bacterial taxa, such as E. coli, containing more immunogenic LPS may drive the adverse metabolic outcomes, as observed in the current study. In addition, an increase in Enterobacteriaceae has been associated with improved outcomes in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients (34–36); however, the increase in Enterobacteriaceae likely reflected the degree to which the intestinal microbial ecosystem was disrupted and did not support a causal link between increased Enterobacteriaceae in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and health outcomes. Another bacterial taxon, Akkermansia, which has been associated with improved metabolic outcomes (37), was similarly increased in HF and HF_EC mice. Inconsistencies in altered abundance of Akkermansia responding to an HFD treatment has been observed (38–40), and this organism did not appear to be an important player in the current study.

In line with an enhanced production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, HF_EC mice had higher colonic and fecal levels of Lcn-2. As a biomarker of intestinal inflammation, Lcn-2 has a role in shaping microbial ecology by scavenging iron (41, 42). Moreover, circulating Lcn-2 was found to be dramatically increased in obese humans and positively associated with obesity phenotypes such as adiposity, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance (28). The increased level of Lcn-2 implied an enhanced inflammation in the gut of HF_EC mice, which may also be a host response to suppress the overgrowth of E. coli. The broadly distinct microbial functions predicted in the HF_EC group indicated changes in bacterial products such as LPS and flagellin, which could stimulate the myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling pathway, known to induced Lcn-2 secretion (42). Different commensal enterobactin-expressing E. coli strains isolated from various rodent hosts induced Lcn-2 secretion in monocolonization studies; however, it has yet to be shown whether other E. coli strains induce obesity. A recent study reported that commensal E. coli isolates exhibited different capacities to elicit acute intestinal inflammation in mice harboring a minimal bacterial community and treated with dextran sulfate sodium (43). Although we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that the proinflammatory response induced by E. coli depends on the characteristic of the strain due to the diversity of this species, the current study demonstrated a potential contribution of commensal E. coli to the low-grade systemic inflammation in the context of long-term HFD treatment. Future studies specifically targeting a reduction in the E. coli population may reveal improved metabolic outcomes in animal models harboring a greater diversity of E. coli species. We also expect that other Enterobacteriaceae and bacteria containing more immunogenic LPS that thrive in response to a Western diet may result in adverse outcomes similar to those observed for E. coli in this study.

In summary, the commensal E. coli strain fills an ecological niche in the gastrointestinal tract with minimal impacts on the overall microbial structure. However, under long-term HFD feeding conditions, commensal E. coli aggravated the HFD-induced glucose dysregulation with increased adiposity and inflammation. Without a drastic increase in the abundance of E. coli after the HFD treatment, an enhanced translocation of bacterial-derived products such as LPS may contribute to the impaired glucose homeostasis, as indicated by systemic proinflammatory responses. The finding highlights the effect of E. coli strain as a member of highly complex commensal communities in the gut on host metabolism in the context of HFD intervention. This proof-of-concept study suggests the importance of investigating the role of the individual gut commensal bacterium in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes and thus developing strategies to manipulate these commensal bacteria to improve metabolic outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, diets, and bacterial strains.

The protocols employed here were approved by the University of Alberta’s Animal Care Committee and in direct accordance with the guideline of the Canadian Council on the Use of Laboratory Animals. Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6J female mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were subjected to dietary treatments, housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions in filter-topped cages with free access to food and water, and handled in a biosafety cabinet. Mice were randomly grouped 3 or 4 per cage by a lab animal technician in a blind fashion and balanced for average body weight. Dietary treatments included a standard chow (5053 [LabDiet]; supplying energy as 13% fat, 25% protein, and 62% carbohydrate) and a high-fat diet (HFD) (D12451i [Research Diets, Inc.]; supplying energy as 45% fat, 20% protein, and 35% carbohydrate). In the non-dietary-challenge arm, mice were allocated to 2 treatments: standard chow (SC) and standard chow with E. coli colonization (SC_EC). In the HFD challenge arm, the mice were allocated to 3 treatments: SC, high-fat diet (HF), and high-fat diet treatment with E. coli colonization (HF_EC) (n = 8 per treatment). Two weeks after E. coli colonization, HF and HF_EC mice were switched to the HFD, while the SC and SC_EC groups continued on a standard-chow diet for 16 weeks. Body weight and food pellets were weighed and recorded weekly. The protocol of the study is shown in Fig. 1A. The experiment was repeated, with a total sample size of 14 for each treatment.

For monocolonization studies, 6- to 8-week-old female GF mice were colonized with different E. coli isolates, while the GF control group received 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were euthanized 2 weeks postcolonization.

Commensal E. coli strains were previously isolated and cultured using MacConkey agar (BD, Sparks, MD) (21, 44), including strain LE, isolated from a healthy laboratory NIH Swiss mouse (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN), strain WME, isolated from wild mouse feces (glycerol stock, Germany), and strain RE, isolated from a healthy laboratory Sprague-Dawley rat. The strains were cultivated in 10 mL of Luria-Bertani medium (Fisher Scientific, Nepean, ON, Canada) at 37°C for 16 h. Mice were exposed to E. coli by oral gavage with 0.1 mL of suspension (~1.0 × 107 CFU). E. coli was enumerated by conducting serial dilutions of feces and spread plating on MacConkey agar.

OGTT.

The OGTT was performed following 12 weeks of dietary treatment, and mice underwent fasting for 16 h prior to the test. The baseline glucose concentration in whole blood taken from the tail vein was measured using a glucometer (Accu-Check Compact Plus; Roche Diagnostics, Laval, QC, Canada) and mice were subsequently given a standard dose of glucose (1 g/kg body weight, 40% [wt/vol] in 1× PBS) by oral gavage. The blood glucose concentration was measured at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min postgavage. The AUC was calculated as described previously (45). Additional blood samples were collected and centrifuged to obtain plasma, which was stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Tissue collection.

Mice fasted for 6 h and were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture in tubes containing EDTA, Complete general protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (EMD Millipore, MA). Sample collection included liver, major WAT depots, intestinal tissue, and digesta. Samples were immediately placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological studies or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80°C.

Gene expression analysis.

Hepatic and gonadal fat RNAs were extracted using the GeneJET RNA purification kit and TRIzol reagent (Thermo Scientific, Nepean, ON, Canada), respectively. Reverse transcription was conducted with 1 μg of RNA using the qScript Flex cDNA synthesis kit (Quantabio, Gaithersburg, MD). The expression of genes listed in Table 2 were analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR. The assay was performed on an ABI StepOne real-time system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using PerfeCTa SYBR green supermix (Quantabio, Gaithersburg, MD), as follows: 95°C for 20 s and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. Genes encoding β2-microglobulin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were used as reference genes for normalization. The fold change of gene expression compared to the SC group was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences used for qPCR assays

| Targeted genea | Primer direction | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| ACC1 | Forward | TGGAGCTAAACCAGCACTCC |

| Reverse | GCCAAACCATCCTGTAAGCC | |

| ApoB | Forward | TCACCATTTGCCCTCAACCTAA |

| Reverse | GAAGGCTCTTTGGAAGTGTAAAC | |

| CD36 | Forward | GATCGGAACTGTGGGCTCAT |

| Reverse | GGTTCCTTCTTCAAGGACAACTTC | |

| CD68 | Forward | TGTCTGATCTTGCTAGGACCG |

| Reverse | GAGAGTAACGGCCTTTTTGTGA | |

| CPT1α | Forward | ATCGTGGTGGTGGGTGTGATAT |

| Reverse | ACGCCACTCACGATGTTCTTC | |

| DGAT1 | Forward | GTGCACAAGTGGTGCATCAG |

| Reverse | CAGTGGGATCTGAGCCATCA | |

| DGAT2 | Forward | TTCCTGGCATAAGGCCCTATT |

| Reverse | AGTCTATGGTGTCTCGGTTGAC | |

| FASN | Forward | AGGGGTCGACCTGGTCCTCA |

| Reverse | GCCATGCCCAGAGGGTGGTT | |

| FABP4 | Forward | AAGGTGAAGAGCATCATAACCCT |

| Reverse | TCACGCCTTTCATAACACATTCC | |

| LDLr | Forward | GAACTCAGGGCCTCTGTCTG |

| Reverse | AGCAGGCTGGATGTCTCTGT | |

| LFABP | Forward | GCAGAGCCAGGAGAACTTTGAG |

| Reverse | TTTGATTTTCTTCCCTTCATGCA | |

| MTTP | Forward | CTCTTGGCAGTGCTTTTTCTCT |

| Reverse | GAGCTTGTATAGCCGCTCATT | |

| PPARα | Forward | GCCTGTCTGTCGGGATGT |

| Reverse | GGCTTCGTGGATTCTCTTG | |

| PPARγ2 | Forward | ATGCACTGCCTATGAGCACT |

| Reverse | CAACTGTGGTAAAGGGCTTG | |

| SREBP-1c | Forward | GGCACTAAGTGCCCTCAACCT |

| Reverse | GCCACATAGATCTCTGCCAGTGT | |

| TNFα | Forward | CACAGAAAGCATGATCCGCGACGT |

| Reverse | CGGCAGAGAGGAGGTTGACTTTCT | |

| β2M | Forward | CATGGCTCGCTCGGTGAC |

| Reverse | CAGTTCAGTATGTTCGGCTTCC | |

| GAPDH | Forward | ATTGTCAGCAATGCATCCTG |

| Reverse | ATGGACTGTGGTCATGAGCC |

ACC1, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; CD36, cluster of differentiation 36; CD68, cluster of differentiation 68; CPT1α, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1α; DGAT, diacylglycerol acyltransferase; FASN, fatty acid synthase; FABP4, fatty acid binding protein 4; LDLr, low-density-lipoprotein receptor; LFABP, liver fatty acid-binding protein; MTTP, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α; PPARγ2, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2; SREBP-1c, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; β2M, β2-microglobulin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Plasma metabolic hormone measurements.

Levels of plasma active amylin, C peptide, active ghrelin, total GIP, active GLP-1, glucagon, insulin, leptin, PP, PYY, and resistin were determined using a multiplex bead panel assay (Eve Technology, Calgary, Canada).

Hepatic lipid extraction and lipid analysis.

Liver tissue was homogenized in a lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and Complete general protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). The total protein concentration of liver homogenates was measured by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Liver lipid extraction was performed using Folch procedure (46). Levels of plasma and hepatic TG (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, MA) and cholesterol (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA) were determined using commercial colorimetric assay kits.

Colonic cytokine/chemokine analysis.

Homogenized colon tissues were analyzed with a mouse cytokine/chemokine panel kit (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Frozen tissues without the distal 1 cm of colon were homogenized in homogenization buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Debris was removed after centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentrations of supernatants were determined with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Nepean, ON, Canada). Cytokine concentrations were normalized to 150 μg of total protein.

Quantification of plasma, colonic, and fecal Lcn-2 and plasma LBP.

The Duoset murine Lcn-2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was applied to plasma, homogenized colonic tissue, and fecal samples (47). Frozen fecal samples were reconstituted in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (100 mg/mL) and mixed with a vortex mixer for 20 min at 4°C to obtain a homogenous suspension. Samples were then centrifuged at 4°C and 12,000 rpm for 10 min to collect clear supernatants, which were stored at −80°C until use. Fecal Lcn-2 levels were measured in a 2× dilution. Plasma was diluted 200× in reagent diluent (1.0% bovine serum albumin in PBS), and colon samples obtained from the cytokine/chemokine analysis were diluted 2× (75 μg of protein) in homogenization buffer for Lcn-2 assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. Colonic Lcn-2 levels were normalized for total protein content, and plasma Lcn-2 levels were expressed in nanograms per milliliter. Plasma LBP concentrations were quantified using a mouse LBP SimpleStep ELISA kit (Abcam, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histology.

The formalin-fixed tissue was embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 3 μm and 5 μm for liver and WAT, respectively, and subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Hepatic steatosis was assessed by a pathologist in a blind manner using an operator-interactive, semiautomated method for data quantification as previously described (48). Adipocyte area was determined using ImageJ software (version 1.46) on at least 300 cells per animal. Images were taken using an EVOS FL autoimaging system (Thermo Scientific, Nepean, ON, Canada).

Microbial composition analysis.

Total DNA was extracted from ileal, cecal, and colonic contents collected at termination using a QIAamp Fast DNA Stool minikit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) with the addition of a bead-beating step. Amplicon libraries amplifying the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene were constructed according to the Illumina 16S metagenomic sequencing library preparation protocol. A paired-end sequencing run was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) using 2 × 300 cycles. Sequences were processed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2, v2021.2) pipeline (49). Demultiplexed paired-end reads were merged and denoised by the Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 plugin (v2021.2.0) incorporated in QIIME2. Based on read quality profiles, forward and reverse reads were truncated at 270 bp and 220 bp, respectively, to remove low-quality nucleotides. An amplicon sequence variant (ASV) feature table was constructed, and features were taxonomically assigned using a pretrained naive Bayes classifier (SILVA database, release 138; 99% identity [50]). A tree was generated using the align-to-tree-mafft-fasttree pipeline from the q2-phylogeny plugin in QIIME2, and downstream analyses were performed in R using multiple functions from phyloseq (v1.34.0) (51), vegan (v2.5-7) (52), and DESeq2 (v1.30.1) (53). The ASV table was rarefied to even depth and filtered to exclude ASVs that showed up less than one time across all samples and ASVs that appeared fewer than three times in at least 20% of analyzed samples. Taxa were agglomerated at each taxonomic rank using the tree_glom function.

The functional profiling of gut microbial communities was predicted using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States version 2 (PICRUSt2, v2.3.0-b) (54). Microbial gene families and pathways were predicted using the MetaCyc database, and group differences in the gene abundance or MetaCyc pathways were estimated using ALDEx2 (v1.24.0) (55).

SCFA analysis.

Fecal samples from SC, HF, and HF_EC groups collected at 12 weeks of dietary treatment were weighed (~50 mg/sample) and homogenized in 800 μL of 25% phosphoric acid. Following centrifugation at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45-μm syringe filter. A 200-μL aliquot of the filtered sample was combined with 50 μL of internal standard isocaproic acid (23 μmol/mL). The mixed sample was further analyzed on a gas chromatography system (Scion 456-GC; Bruker, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a Stabilwax-DA column (Restek, Saunderton, Buckinghamshire, UK). Final concentrations of SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate, valerate, isovalerate, and caproate, were normalized to sample weights.

Statistical analysis and visualization.

The effects of diet and time on body weight were analyzed by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc adjustment in SAS (version 10.0.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). To compare the difference in fecal E. coli load (log transformed), gene expression, metabolic hormone levels, cytokine/chemokine levels, SCFA profiles, and alpha diversity indices between treatments, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of data distribution, and one-way ANOVA for parametric data or the Kruskal-Wallis test for nonparametric data was subsequently performed. P values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Tukey’s or Dunn’s tests. Outliers in data sets were identified based on the interquartile range. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between plasma LBP and metabolic hormone levels. For microbial composition analyses, PERMANOVA was used to assess the difference in community structure (999 permutations, adonis2 function, vegan package). Principal-coordinate analysis based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix was plotted using the phyloseq package. Comparisons of individual ASVs between groups were conducted using DESeq2 at a controlled false discovery rate (FDR) level of 5%. R (v4.1.0) and GraphPad Prism was used for visualizing results.

Data availability.

The data supporting the findings of this study are presented in the article and the supplemental material. The whole-genome sequences of E. coli strains LE, WME, and RE were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers PRJNA352620, PRJNA780221, and PRJNA780235, respectively. Raw sequence reads of the 16S rRNA gene amplicon data are available at the SRA under accession number PRJNA768937.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nicole Coursen and Kunimasa Suzuki from the University of Alberta for their expertise and assistance with animal work and cytokine analysis.

T.J., B.C.T.B., A.J.F., D.M.P., S.T., and C.M.S. generated the data. C.M.S. and B.P.W. reviewed and revised the manuscript. T.J. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. B.P.W. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study.

This research was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grant 436154 to B.P.W. B.P.W. is supported by the Canada Research Chair Program. T.J. was supported by Graduate Student Scholarships from Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures.

We have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Benjamin P. Willing, Email: willing@ualberta.ca.

Christopher A. Elkins, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

REFERENCES

- 1.Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. 2005. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:11070–11075. 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. 2008. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3:213–223. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäckhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. 2007. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:979–984. 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. 2006. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444:1027–1031. 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutagy NE, McMillan RP, Frisard MI, Hulver MW. 2016. Metabolic endotoxemia with obesity: is it real and is it relevant? Biochimie 124:11–20. 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmée E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrières J, Tanti J-F, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. 2007. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56:1761–1772. 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caesar R, Reigstad CS, Bäckhed HK, Reinhardt C, Ketonen M, Lundén GÖ, Cani PD, Bäckhed F. 2012. Gut-derived lipopolysaccharide augments adipose macrophage accumulation but is not essential for impaired glucose or insulin tolerance in mice. Gut 61:1701–1707. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 71:635–700. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun S, Ji Y, Kersten S, Qi L. 2012. Mechanisms of inflammatory responses in obese adipose tissue. Annu Rev Nutr 32:261–286. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim K-A, Gu W, Lee I-A, Joh E-H, Kim D-H. 2012. High fat diet-induced gut microbiota exacerbates inflammation and obesity in mice via the TLR4 signaling pathway. PLoS One 7:e47713. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caroff M, Karibian D. 2003. Structure of bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Carbohydr Res 23:2431–2447. 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vatanen T, Kostic AD, D’Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, Kolde R, Vlamakis H, Arthur TD, Hamalainen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Ubo R, Mokurov S, Dorshakova N, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Szabo SJ, Porter JA, Lahdesmaki H, Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Cullen TW, Knip M, DIABIMMUNE Study Group . 2016. Variation in microbiome LPS immunogenicity contributes to autoimmunity in humans. Cell 4:842–853. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waidmann M, Bechtold O, Frick J-S, Lehr H-A, Schubert S, Dobrindt U, Loeffler J, Bohn E, Autenrieth IB. 2003. Bacteroides vulgatus protects against Escherichia coli-induced colitis in gnotobiotic interleukin-2-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 1:162–177. 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sze MA, Schloss PD. 2016. Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome. mBio 7:e01018-16. 10.1128/mBio.01018-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanislawski MA, Dabelea D, Lange LA, Wagner BD, Lozupone CA. 2019. Gut microbiota phenotypes of obesity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 5:18. 10.1038/s41522-019-0091-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santacruz A, Collado MC, García-Valdés L, Segura MT, Martín-Lagos JA, Anjos T, Martí-Romero M, Lopez RM, Florido J, Campoy C, Sanz Y. 2010. Gut microbiota composition is associated with body weight, weight gain and biochemical parameters in pregnant women. Br J Nutr 104:83–92. 10.1017/S0007114510000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murugesan S, Ulloa-Martínez M, Martínez-Rojano H, Galván-Rodríguez FM, Miranda-Brito C, Romano MC, Piña-Escobedo A, Pizano-Zárate ML, Hoyo-Vadillo C, García-Mena J. 2015. Study of the diversity and short-chain fatty acids production by the bacterial community in overweight and obese Mexican children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34:1337–1346. 10.1007/s10096-015-2355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson CLJ, Önnerfält J, Xu J, Molin G, Ahrné S, Thorngren-Jerneck K. 2012. The microbiota of the gut in preschool children with normal and excessive body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20:2257–2261. 10.1038/oby.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, Finlay BB. 2007. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe 2:119–129. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fei N, Zhao L. 2013. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice. ISME J 7:880–884. 10.1038/ismej.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ju T, Shoblak Y, Gao Y, Yang K, Fouhse J, Finlay B, So YW, Stothard P, Willing B. 2017. Initial gut microbial composition as a key factor driving host response to antibiotic treatment, as exemplified by the presence or absence of commensal Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e01107-17. 10.1128/AEM.01107-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Smith DL, Keating KD, Allison DB, Nagy TR. 2014. Variations in body weight, food intake and body composition after long-term high-fat diet feeding in C57BL/6J mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22:2147–2155. 10.1002/oby.20811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahrén B, Scheurink AJW. 1998. Marked hyperleptinemia after high-fat diet associated with severe glucose intolerance in mice. Eur J Endocrinol 139:461–467. 10.1530/eje.0.1390461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan WW, Myers MG. 2018. Leptin and the maintenance of elevated body weight. Nat Rev Neurosci 19:95–105. 10.1038/nrn.2017.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimomura I, Shimano H, Korn BS, Bashmakov Y, Horton JD. 1998. Nuclear sterol regulatory element-binding proteins activate genes responsible for the entire program of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in transgenic mouse liver. J Biol Chem 273:35299–35306. 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Xu G, Qin Y, Zhang C, Tang H, Yin Y, Xiang X, Li Y, Zhao J, Mulholland M, Zhang W. 2014. Ghrelin promotes hepatic lipogenesis by activation of mTOR-PPAR signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:13163–13168. 10.1073/pnas.1411571111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun K, Kusminski CM, Scherer PE. 2011. Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J Clin Invest 121:2094–2101. 10.1172/JCI45887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. 2006. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 116:1793–1801. 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. 2003. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112:1821–1830. 10.1172/JCI200319451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hildebrandt MA, Hoffmann C, Sherrill-Mix SA, Keilbaugh SA, Hamady M, Chen Y-Y, Knight R, Ahima RS, Bushman F, Wu GD. 2009. High fat diet determines the composition of the gut microbiome independent of host genotype and phenotype. Gastroenterology 137:1716–1724.E2. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziętak M, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Markiewicz LH, Ståhlman M, Kozak LP, Bäckhed F. 2016. Altered microbiota contributes to reduced diet-induced obesity upon cold exposure. Cell Metab 23:1216–1223. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D, Zárate Rodriguez JG, Rogers AB, Robine N, Loke P, Blaser MJ. 2014. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell 158:705–721. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zweigner J, Schumann RR, Weber JR. 2006. The role of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in modulating the innate immune response. Microbes Infect 8:946–952. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y, Parameswaran P, Crowell MD, Wing R, Rittmann BE, Krajmalnik-Brown R. 2009. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:2365–2370. 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Prifti E, Belda E, Ichou F, Kayser BD, Dao MC, Verger EO, Hedjazi L, Bouillot J-L, Chevallier J-M, Pons N, Le Chatelier E, Levenez F, Ehrlich SD, Dore J, Zucker J-D, Clément K. 2019. Major microbiota dysbiosis in severe obesity: fate after bariatric surgery. Gut 68:70–82. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo Y, Huang ZP, Liu CQ, Qi L, Sheng Y, Zou DJ. 2018. Modulation of the gut microbiome: a systematic review of the effect of bariatric surgery. Eur J Endocrinol 178:43–56. 10.1530/EJE-17-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, de Vos WM, Cani PD. 2013. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:9066–9071. 10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalby MJ, Ross AW, Walker AW, Morgan PJ. 2017. Dietary uncoupling of gut microbiota and energy harvesting from obesity and glucose tolerance in mice. Cell Rep 21:1521–1533. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomas J, Mulet C, Saffarian A, Cavin J-B, Ducroc R, Regnault B, Kun Tan C, Duszka K, Burcelin R, Wahli W, Sansonetti PJ, Pédron T. 2016. High-fat diet modifies the PPAR-γ pathway leading to disruption of microbial and physiological ecosystem in murine small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:E5934–E5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carmody RN, Gerber GK, Luevano JM, Gatti DM, Somes L, Svenson KL, Turnbaugh PJ. 2015. Diet dominates host genotype in shaping the murine gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 17:72–84. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK, Akira S, Aderem A. 2004. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature 432:917–921. 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh V, Yeoh BS, Chassaing B, Zhang B, Saha P, Xiao X, Awasthi D, Shashidharamurthy R, Dikshit M, Gewirtz A, Vijay-Kumar M. 2016. Microbiota-inducible innate immune siderophore binding protein lipocalin 2 is critical for intestinal homeostasis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:482–498.E6. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kittana H, Gomes-Neto JC, Heck K, Geis AL, Segura Muñoz RR, Cody LA, Schmaltz RJ, Bindels LB, Sinha R, Hostetter JM, Benson AK, Ramer-Tait AE. 2018. Commensal Escherichia coli strains can promote intestinal inflammation via differential interleukin-6 production. Front Immunol 9:2318. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ju T, Willing BP. 2018. Isolation of commensal Escherichia coli strains from feces of healthy laboratory mice or rats. Bio Protoc 8:e2780. 10.21769/BioProtoc.2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heikkinen S, Argmann CA, Champy MF, Auwerx J. 2007. Evaluation of glucose homeostasis. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 77:29B–33B. 10.1002/0471142727.mb29b03s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS. 1956. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226:497–509. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chassaing B, Srinivasan G, Delgado MA, Young AN, Gewirtz AT, Vijay-Kumar M. 2012. Fecal lipocalin 2, a sensitive and broadly dynamic non-invasive biomarker for intestinal inflammation. PLoS One 7:e44328. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amella C, Cappello F, Kahl P, Fritsch H, Lozanoff S, Sergi C. 2008. Spatial and temporal dynamics of innervation during the development of fetal human pancreas. Neuroscience 154:1477–1487. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F, Bai Y, Bisanz JE, Bittinger K, Brejnrod A, Brislawn CJ, Brown CT, Callahan BJ, Caraballo-Rodríguez AM, Chase J, Cope EK, Da Silva R, Diener C, Dorrestein PC, Douglas GM, Durall DM, Duvallet C, Edwardson CF, Ernst M, Estaki M, Fouquier J, Gauglitz JM, Gibbons SM, Gibson DL, Gonzalez A, Gorlick K, Guo J, Hillmann B, Holmes S, Holste H, Huttenhower C, Huttley GA, Janssen S, Jarmusch AK, Jiang L, Kaehler BD, Kang KB, Keefe CR, Keim P, Kelley ST, Knights D, et al. 2019. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37:852–857. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. 2013. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D590–D596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. 2013. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8:e61217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, et al. 2019. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5–7.

- 53.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Vega Thurber RL, Knight R, Beiko RG, Huttenhower C. 2013. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol 31:814–821. 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandes AD, Macklaim JM, Linn TG, Reid G, Gloor GB. 2013. ANOVA-like differential expression (ALDEx) analysis for mixed population RNA-Seq. PLoS One 8:e67019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aem.01628-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.2 MB (1.2MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are presented in the article and the supplemental material. The whole-genome sequences of E. coli strains LE, WME, and RE were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers PRJNA352620, PRJNA780221, and PRJNA780235, respectively. Raw sequence reads of the 16S rRNA gene amplicon data are available at the SRA under accession number PRJNA768937.