Abstract

Objectives

We assessed the prevalence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM against four endemic human coronaviruses and two SARS-CoV-2 antigens among vaccinated and unvaccinated staff at health care centers in Uganda, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Methods

The government health facility staff who had patient contact in Goma (Democratic Republic of Congo), Kambia District (Sierra Leone), and Masaka District (Uganda) were enrolled. Questionnaires and blood samples were collected at three time points over 4 months. Blood samples were analyzed with the Luminex MAGPIXⓇ.

Results

Among unvaccinated participants, the prevalence of IgG/IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain or nucleocapsid protein at enrollment was 70% in Goma (138 of 196), 89% in Kambia (112 of 126), and 89% in Masaka (190 of 213). The IgG responses against endemic human coronaviruses at baseline were not associated with SARS-CoV-2 sero-acquisition during follow-up. Among the vaccinated participants, those who had evidence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM at baseline tended to have higher IgG responses to vaccination than those who were SARS-CoV-2 seronegative at baseline, controlling for the time of sample collection since vaccination.

Conclusion

The high levels of natural immunity and hybrid immunity should be incorporated into both vaccination policies and prediction models of the impact of subsequent waves of infection in these settings.

Keywords: Seroprevalence, Hybrid immunity, Cross-reactivity, SARS-CoV-2, Human coronaviruses

Introduction

Natural immunity and ‘hybrid immunity’, generated after a mixture of both natural infection and vaccination, could illicit more effective and longer-lasting protection against subsequent symptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2 than vaccination alone [1,2]. Vaccine coverage with at least one dose of a prophylactic COVID-19 vaccine was 4.6% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), 34.1% in Sierra Leone, and 40.5% in Uganda in August 2022 [3]. The outcome of the future waves of SARS-CoV-2 infection will be determined by both the natural and hybrid immunity and whether other common circulating pathogens, such as endemic human coronaviruses (HCoVs) produce a nonspecific protective response.

Before SARS-CoV-2, the most common HCoVs were the alpha-HCoVs (OC43, HKU1) and the beta-HCoVs (NL63 and 229E), which cause mild to moderate respiratory tract diseases. Worldwide, most people acquire one or more of these viruses in their lifetime and develop symptoms, such as cough, sore throat, runny nose, fever, headache, and general malaise [4], [5], [6]. In prepandemic samples, OC43 and HKU1 antispike antibodies have displayed cross-binding to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with some neutralizing activity [7,8]; although, it is still unclear whether previous exposure to HCoVs provides any protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection [9,10]. In addition, both vaccination and natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 have been shown to generate immunoglobulin G (IgG) which binds spike proteins from other beta-HCoVs (HKU1 and OC43; but not alpha-HCoVs NL63 or 229E) [7,9,11,12]. SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or vaccination may stimulate memory responses and generate the production of IgG to HCoVs in adults with previous exposure to HCoVs or there may simply be cross-binding to common epitopes. Results differ on whether these anamnestic responses are protective against infection with SARS-CoV-2. Pre-existing IgG antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein (NP) of HCoV 229E were weakly correlated with remaining uninfected with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort of health care workers but were not correlated with protection from infection in a large retrospective analysis of stored samples and electronic health records [13]. However, both studies found that pre-existing IgG antibodies to HCoVs correlated with less severe symptoms in those who did become SARS-CoV-2-positive [13,14]. It may be important to account for the levels of previous exposure to other HCoVs when estimating the natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and to control for the presence of cross-reactive antibodies to HCoVs when using the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 as a marker of exposure to the virus [7,8].

We aimed to assess the prevalence of IgG and IgM in two SARS-CoV-2 antigens, the NP, a marker of natural exposure, and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein, which could be a marker of natural exposure or vaccine-induced immunity among vaccinated and unvaccinated staff at health care centers in Uganda, Sierra Leone, and the DRC. We assessed the IgG and IgM responses to four endemic HCoVs and explored whether these correlated with a reduced risk of acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 during the study or affected the immune responses to subsequent vaccination. We hypothesized that there may be different rates of sero-acquisition across the different settings that may be correlated with differences in HCoV seroprevalence or other risk factors.

Methods

Study design

This was a longitudinal observational study of SARS-CoV-2 serology among staff working within primary health care facilities. Blood samples were collected over 4 months at three time points from February to June 2021 in DRC, March to July 2021 in Sierra Leone, and July to November 2021 in Uganda.

Study setting and population

The study took place in the city of Goma, DRC, and both urban and rural locations in Kambia District, Sierra Leone, and Masaka District in Uganda. A list of all government health facilities in each area was compiled. In Masaka District, all 25 government health centers were selected. In Goma, all 21 urban and accessible health centers were selected. In Kambia District, a random number generator was used to select 29 health facilities, proportional to the total number of health posts and health centers in the district.

Sierra Leone reported its first COVID-19 case on March 31, 2020 [15], the DRC on March 10, 2020 [16], and Uganda on March 21, 2020 [17]. COVID-19 vaccination was launched in Sierra Leone on March 15, 2021 [18], in DRC on April 19, 2021 [19], and in Uganda on March 10, 2021 [20,21].

Sample collection and processing

We administered a short questionnaire to consenting staff at the selected health facilities to collect demographic data, information on comorbidities, vaccination status, reported symptoms of COVID-19, and contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases in their household, community, or at work. At each site, a trained phlebotomist in appropriate personal protective equipment, compliant with local guidelines, collected a 5-ml venous blood sample into a serum sample separator tube. In each country, blood samples were allowed to clot upright and transported from the field to the local laboratories at 2-15°C. In the laboratory, serum was separated into aliquots and was frozen at −20°C. Each participant was followed up at two further visits at 2-month intervals. At each visit, updated information on his/her COVID-19 vaccination status and contact data were recorded and a blood sample was collected. One aliquot of serum from each visit from the DRC and Uganda was shipped at −80°C to the research laboratory in Kambia town, Sierra Leone.

All samples from all participants were run on the Luminex MAGPIXⓇ platform (Luminex, TX, USA) to test for IgG and IgM antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 NP and RBD, OC43 NP, 229E NP, HKU1 NP, NL63 S1, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus NP by adapting a previously established assay [22]. The IgG assay achieved sensitivity and specificity of 98.8% and 97.9% for RBD, respectively, and 95.3% and 99.0% for NP, respectively. The IgM assay achieved the sensitivities and specificities of 95.6% and 100% for RBD, respectively, and 65.8% and 100% for NP, respectively (personal communication K. K. A. Tetteh, 2022). The results of the multiplex assay were reported in units of mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) and were defined as seropositive if they were three SDs above the mean MFI of 40 European prepandemic negative controls provided by Public Health England, which were samples taken in 2016. Positive SARS-COV-2 control pools were from The National Institute for Biological Standards and Control in the UK (NIBSC) and were used as plate controls (20/B770; 20/130).

Statistical analysis

The seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 was defined if a sample was seropositive for IgG or IgM to either the SARS-CoV-2 RBD or the NP and was tabulated stratified by vaccination status. The seroprevalence of other endemic HCoVs was not possible to define given the lack of true-negative controls. In the sensitivity analyses of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence, we excluded samples with very high MFI to the endemic HCoVs to check if SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence estimates changed in this subset of samples. We defined these samples as those with MFI units to endemic HCoVs that were three or more SDs above the MFI to that HCoV antigen in the SARS-CoV-2-negative control samples. The SARS-CoV-2-negative control samples were sera from European adults and likely included some who had a history of exposure to HCoVs but these represented the closest we had to an HCoV-naïve population because HCoV infections are thought to be less prevalent in Europe than in Africa [23].

Correlations in IgG responses that could indicate cross-binding were assessed by plotting the MFI units of IgG to each antigen against one another and calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Exploratory analyses examined the factors associated with remaining IgG/M seronegative, i.e., not seroconverting to SARS-CoV-2 RBD/N-protein during follow-up, using logistic regression among unvaccinated participants in Goma. There were too few participants who remained seronegative in Masaka and Kambia to perform this analysis there. In addition, the distributions of log IgG MFI units to HCoVs at baseline were compared among participants who subsequently seroconverted to SARS-CoV-2 during follow-up and those who remained negative during follow-up to determine if pre-existing IgG responses to endemic HCoVs predicted the risk of acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study. Log IgG MFI unit distributions were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Linear regression of MFI units was used to determine if there was significant waning of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 RBD/NP over time, controlling for clustering of data by participant.

Among participants who received one or two doses of any COVID-19 vaccine before or during the study, we plotted the IgG MFI to SARS-CoV-2 RBD by time since vaccination and by dose, using the recorded date of vaccination in their vaccination records. In an exploratory analysis, we looked at whether seropositivity to SARS-CoV-2 at baseline influenced the subsequent postvaccination SARS-CoV-2 RBD IgG MFI, controlling for the time of sampling since vaccination.

Results

The study population

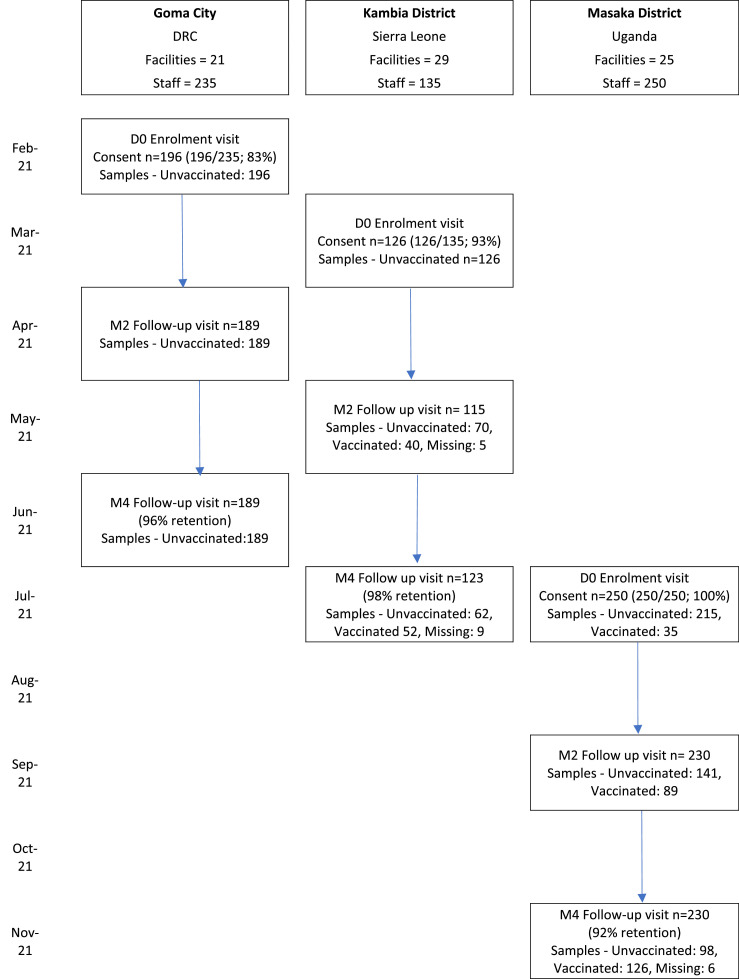

The baseline serosurvey enrolled 196 participants in February 2021 in Goma, DRC; 126 participants in March 2021 in Kambia, Sierra Leone; and 250 participants in July of the same year in Masaka District, Uganda. Retention at month 4 was 96% in Goma (189 of 196), 98% in Kambia (123 of 126), and 92% in Masaka (230 of 250) (Figure 1 ). The study populations, which included everyone with patient contact at the selected health facilities, were distinct in the different settings (Table 1 ). A high proportion of Sierra Leonean staff had a mid-upper arm circumference of >31 cm (79 of 126; 63%) and known pre-existing conditions (98 of 126; 78%). At least one contact with a known COVID-19 case over the previous month was reported by 41% (103 of 250) of Ugandan participants, 27% (52 of 196) of participants in DRC, but only one participant in Sierra Leone.

Figure 1.

Study timeline and participant flowa. D0, Day of enrolment; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; M2/4, Month 2 or 4 follow-up visit.

aCOVID-19 vaccination programs started in Sierra Leone and Uganda in March 2021, and in DRC in April 2021.

Table 1.

Description of the study population.

| Participant characteristics | Goma DRC N |

% | Kambia Sierra Leone N |

% | Masaka Uganda N |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total enrolleda | 196 | 126 | 250 | |||

| Total at final study visit (month 4) | 189 | 96.4 | 123 | 97.6 | 230 | 92.0 |

| Age (median, range) | 39 | (15-76) | 38 | (20-68) | 35 | (18-74) |

| Female | 111 | 56.6 | 81 | 64.3 | 171 | 68.4 |

| Role in the facilityb | ||||||

| Doctor or clinical officer | 4 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 6.8 |

| Nurse or midwifec | 159 | 81.1 | 29 | 23.0 | 103 | 41.2 |

| Clinical support staffd | 13 | 6.6 | 70 | 55.6 | 70 | 28.0 |

| Laboratory/pharmacy staffe | 18 | 9.2 | 13 | 10.3 | 35 | 14.0 |

| Nonclinical support stafff | 2 | 1.0 | 14 | 11.1 | 25 | 10.0 |

| Highest level of schooling | ||||||

| Noneg | 1 | 0.5 | 7 | 5.6 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Complete primary | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.8 | 7 | 2.8 |

| Incomplete secondary | 15 | 7.7 | 31 | 24.6 | 21 | 8.4 |

| Complete secondary & above | 178 | 90.8 | 86 | 68.3 | 221 | 88.4 |

| Smoker (once per week or more) | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 14 | 11.1 | 2 | 0.8 |

| No | 195 | 100 | 112 | 88.9 | 248 | 99.2 |

| Mid-upper arm circumference | ||||||

| <24 cm | 17 | 8.7 | 2 | 1.6 | 11 | 4.4 |

| 24-31 cm | 139 | 70.9 | 45 | 35.7 | 163 | 65.2 |

| >31 cm | 40 | 20.4 | 79 | 62.7 | 76 | 30.4 |

| Known contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case | ||||||

| Yes | 52 | 26.5 | 1 | 0.8 | 103 | 41.2 |

| No | 144 | 73.5 | 125 | 99.2 | 147 | 58.8 |

| No. people sharing the participant's room to sleep | ||||||

| 0 people | 126 | 64.3 | 44 | 34.9 | 208 | 83.2 |

| 1-2 people | 56 | 28.6 | 18 | 14.3 | 26 | 10.4 |

| 3 people | 11 | 5.6 | 25 | 19.8 | 10 | 4.0 |

| >=4 people | 3 | 1.5 | 39 | 31.0 | 6 | 2.4 |

| Use of a mask at work | ||||||

| None of the time | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Half the time | 33 | 16.8 | 4 | 3.2 | 10 | 4.0 |

| Most but not all of the time | 99 | 50.5 | 70 | 55.6 | 51 | 20.4 |

| All the time | 64 | 32.7 | 50 | 39.7 | 189 | 75.6 |

| Don't know | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Reported COVID-19 symptoms in the last monthh | ||||||

| Yes | 75 | 38.3 | 16 | 12.7 | 116 | 46.4 |

| No | 121 | 61.7 | 110 | 87.3 | 134 | 53.6 |

| Known pre-existing conditionsi | ||||||

| Yes | 37 | 18.9 | 98 | 77.8 | 65 | 26.0 |

| No | 159 | 81.1 | 28 | 22.2 | 185 | 74.0 |

| COVID-19 vaccination status at baseline (≥ 1 dose)j | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 14.0 |

| No | 196 | 100 | 126 | 100 | 215 | 86.0 |

| COVID-19 vaccination status at M2 (≥1 dose)j | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 48 | 39.0 | 89 | 38.7 |

| No | 189 | 100 | 75 | 61.0 | 141 | 61.3 |

| COVID-19 vaccination status at M4 (at least one dose)j | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 60 | 48.8 | 130 | 56.5 |

| No | 189 | 100 | 63 | 51.2 | 100 | 43.5 |

| Immunization record among those vaccinated at any timepoint | ||||||

| Verbal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 53.1 |

| Written | 0 | 0 | 60 | 100 | 14 | 10.8 |

| Vaccine product (dose one)k | ||||||

| AstraZeneca | 0 | 0 | 29 | 48.3 | 14 | 100 |

| SinoPharm | 0 | 0 | 31 | 51.7 | 0 | 0 |

The baseline serosurvey was conducted in February 2021 in Goma, DRC, in March 2021 in Kambia, Sierra Leone and in July 2021 in Masaka district, Uganda. Percentages are column percentages.

All categories include trainees.

Includes registered, enrolled or assistant nurses and midwifes, and community health nurses.

Includes health attendants and assistants, maternal and child health aids, antenatal care workers, community health workers, counselors, peer/health educators, nutritionists, physiotherapists, psychologists, social workers and triage/screening staff.

Includes laboratory technicians and assistants, and pharmacists and pharmacy attendants.

Includes community linkage personnel, ambulance drivers, data clerks, health information assistants, health inspectors, porters, receptionists, retention officers and other support staff incl. traditional birth attendants.

All participants who reported no education or incomplete primary school education were acting as nonclinical support staff or assistants. e.g., in Kambia: 1 was a traditional birth attendant, two were laboratory assistants, one was a porter and one had a role in participant screening.

Symptoms included: History of fever/chills, shortness of breath, aches/pain, general weakness/malaise, diarrhea, cough, nausea/vomiting, sore throat, headache, runny nose, irritability/confusion, loss of sense of smell or taste.

Pre-existing conditions included known ‘diagnoses’ of: Pregnancy, obesity, cancer, diabetes, HIV/other immune deficiency, heart disease, asthma (requiring medication), chronic lung disease (nonasthma), chronic liver disease, chronic hematologic disorder, chronic kidney disease, chronic neurological impairment/disease, organ or bone marrow recipient.

Vaccination status is as recorded at the visit from immunization records or participant recall, no vaccines were delivered at study visits or as part of the study.

Vaccine product was only recorded among participants with a written immunization record. There was no recorded mixing of products among those who were vaccinated with >1 dose.

DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

The baseline surveys were conducted just before the implementation of the national COVID-19 vaccination programs in in DRC and Sierra Leone; in both settings, vaccinations began in April 2021. In Goma, all study participants remained unvaccinated for the duration of the study; in Kambia, 49% (60 of 123) of participants had received at least one dose of vaccine by the end of the study (month 4). In Uganda, COVID-19 vaccination began in March 2021; 14% (35 of 250) of study participants had been vaccinated with at least one dose at the baseline study visit in July and this increased to 56% (130 of 230) by the final study visit in November 2021.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among unvaccinated participants

Among unvaccinated participants, the prevalence of IgG/M to SARS-CoV-2 RBD or N-protein at enrollment was 70% (138 of 196) in Goma, 89% (112 of 126) in Kambia, and 89% (190 of 213) in Masaka (Table 2 ). In Goma, 14% (28 of 186) of unvaccinated participants with IgG and IgM data at all time points were seronegative at baseline and became seropositive during the 4 months of the study, i.e., seroconverted; 7 (4%) seroreverted (Supplement Table 1). In Sierra Leone, 4 of 62 (7%) unvaccinated participants were initially seronegative and seroconverted during follow-up; 9 (15%) were initially seropositive and seroconverted during follow-up (Supplement Table 1). In Uganda, 4 of 98 (4%) unvaccinated participants were seronegative at baseline and seroconverted during follow-up, and 3 of 98 (3%) unvaccinated participants were initially seropositive and seroconverted during follow-up (Supplement Table 1). Among unvaccinated participants, almost all had detectable IgG/IgM to SARS-CoV-2 RBD/NP at least once by the end of the 4 months of follow-up: 88% were seropositive to SARS-CoV-2 at least once in Goma, 100% in Sierra Leone, and 96% in Masaka (Table 2, Supplement Table 1, Supplement Figure 1).

Table 2.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among unvaccinated participantsa and the prevalence of samples with high MFI to other HCoVs.

| Goma, DRC | D0 (February 2021) |

M2 (April 2021) |

M4 (June 2021) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (pos) | % | N | n (pos) | % | N | n (pos) | % | |

| SARS2 RBD IgG | 196 | 98 | 50 | 189 | 116 | 61.4 | 189 | 119 | 63 |

| SARS2 NP IgG | 196 | 110 | 43.9 | 189 | 121 | 64 | 189 | 116 | 61.4 |

| SARS2 RBD/NP IgG | 196 | 125 | 63.8 | 189 | 145 | 76.7 | 189 | 146 | 77.3 |

| SARS2 RBD/NP IgG/IgM | 196 | 138 | 70.4 | 189 | 152 | 80.4 | 189 | 157 | 83.1 |

| MERS NP IgG | 196 | 14 | 7.1 | 188 | 13 | 6.9 | 189 | 12 | 6.3 |

| OC43 NP IgG | 196 | 5 | 2.6 | 189 | 1 | 0.5 | 189 | 7 | 3.7 |

| 229E NP IgG | 196 | 5 | 2.6 | 188 | 3 | 1.6 | 189 | 9 | 4.8 |

| HKU1 NP IgG | 196 | 22 | 11.2 | 189 | 13 | 6.9 | 189 | 22 | 11.6 |

| NL63 S1 IgG | 196 | 9 | 4.6 | 189 | 4 | 2.1 | 189 | 6 | 3.2 |

| Kambia, Sierra Leone | D0 (March 2021) |

M2 (May 2021) |

M4 (July 2021) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (pos) | % | N | n (pos) | % | N | n (pos) | % | |

| SARS2 RBD IgG | 126 | 70 | 55.6 | 75 | 51 | 68.0 | 62 | 34 | 54.8 |

| SARS2 NP IgG | 126 | 90 | 71.4 | 75 | 53 | 70.7 | 62 | 36 | 58.1 |

| SARS2 RBD/NP IgG | 126 | 98 | 77.8 | 75 | 59 | 78.7 | 62 | 43 | 69.4 |

| SARS2 RBD/NP IgG/IgM | 126 | 112 | 88.9 | 75 | 66 | 88 | 62 | 51 | 73.3 |

| MERS NP IgG | 126 | 46 | 36.5 | 75 | 21 | 28.0 | 62 | 14 | 22.6 |

| OC43 NP IgG | 126 | 24 | 19.1 | 75 | 10 | 13.3 | 62 | 4 | 6.5 |

| 229E NP IgG | 126 | 4 | 3.2 | 75 | 1 | 1.3 | 62 | 1 | 1.6 |

| HKU1 NP IgG | 126 | 29 | 23.0 | 75 | 19 | 25.3 | 62 | 12 | 19.4 |

| NL63 S1 IgG | 126 | 10 | 7.9 | 75 | 8 | 10.7 | 62 | 4 | 6.5 |

| Masaka, Uganda | D0 (July 2021) |

M2 (September 2021) |

M4 (November 2021) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (pos) | % | N | n (pos) | % | N | n (pos) | % | |

| SARS2 RBD IgG | 213 | 157 | 73.7 | 141 | 105 | 74.5 | 98 | 81 | 82.7 |

| SARS2 NP IgG | 213 | 135 | 63.4 | 141 | 86 | 61.0 | 98 | 61 | 62.2 |

| SARS2 RBD/NP IgG | 213 | 172 | 80.8 | 141 | 118 | 83.7 | 98 | 86 | 87.8 |

| SARS2 RBD/NP IgG/M | 213 | 190 | 89.2 | 141 | 118 | 83.7 | 98 | 91 | 92.9 |

| MERS NP IgG | 213 | 31 | 14.6 | 141 | 15 | 10.6 | 98 | 10 | 10.2 |

| OC43 NP IgG | 213 | 10 | 4.7 | 141 | 5 | 3.5 | 98 | 5 | 5.1 |

| 229E NP IgG | 213 | 16 | 7.5 | 141 | 2 | 1.4 | 98 | 1 | 1.0 |

| HKU1 NP IgG | 213 | 27 | 12.7 | 141 | 13 | 9.2 | 98 | 15 | 15.3 |

| NL63 S1 IgG | 213 | 28 | 13.1 | 141 | 16 | 11.3 | 98 | 8 | 8.2 |

DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; HCoV, human coronavirus; Ig, immunoglobulin; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; NP, nucleocapsid protein; RBD, receptor-binding domain; S, spike.

SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity was defined as MFI units more than three standard deviations (SD) from the mean of EU negative controls. HCoV seropositivity is also defined as three SD from the mean of EU control samples; however, true negatives were not possible to define due to the endemic nature of HCoVs worldwide; therefore, seropositivity is defined here qualitatively and should be interpreted as indicative of high MFI units rather than a classification of previous exposure or protective titers.

In DRC all participants were unvaccinated for the duration of the study, participants who were vaccinated in Sierra Leone and Uganda are not included in this table.

Correlations between IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 and other HCoVs

Across all three settings, several samples demonstrated high MFI to MERS NP, i.e., responses at least three SDs higher than negative controls. Serum IgG bound to MERS NP, despite no known circulation of MERS or clinical presentation of the disease in these settings. In addition, the level of binding differed by site: in Goma, 7% of samples contained IgG that bound to MERS NP, in Uganda 14%, and in Sierra Leone 37% (Table 2). There were no statistically significant correlations between IgG MFI units to MERS NP and SARS-CoV-2 NP. To determine why the prevalence of IgG binding to MERS NP differed by site, we looked at correlations between IgG MFI to MERS NP protein and other HCoVs. In Goma, IgG MFI units to MERS NP correlated with OC43-NP and 229E-NP. In Uganda, MFI to MERS NP correlated with OC43-NP, HKU1-NP, and NL63 S1. In Sierra Leone, where MERS NP binding was most prevalent but the sample size was smallest, no correlations were seen between MFI units to MERS NP protein and other HCoVs (Supplement Figure 2, Supplement Table 2).

Between 1% and 19% of samples across sites and time points exhibited high IgG MFI units (at least three SD higher than the MFI units in SARS-CoV-2-negative control samples) to endemic coronaviruses (Table 2). At the baseline visit, there were some correlations between MFI units of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 NP and MFI units of IgG to NP of the endemic HCoVs. In samples from Goma, the MFI units of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 NP correlated with OC43-NP and 229E-NP, and IgG to SARS-CoV-2 RBD correlated with IgG to NL63 S1-protein. In samples from Uganda, the MFI units of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 NP correlated with IgG MFI units to 229E-NP only. In Sierra Leone, no significant correlations were detected (Supplement Figure 3, Supplement Table 3).

Due to this indication of cross-binding of IgG, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, excluding samples with high MFI to each HCoV in turn, and there were no significant differences in the estimates of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence estimated across the whole sample set and those estimated in a restricted dataset of samples with low MFI to each HCoV (Supplement Table 4).

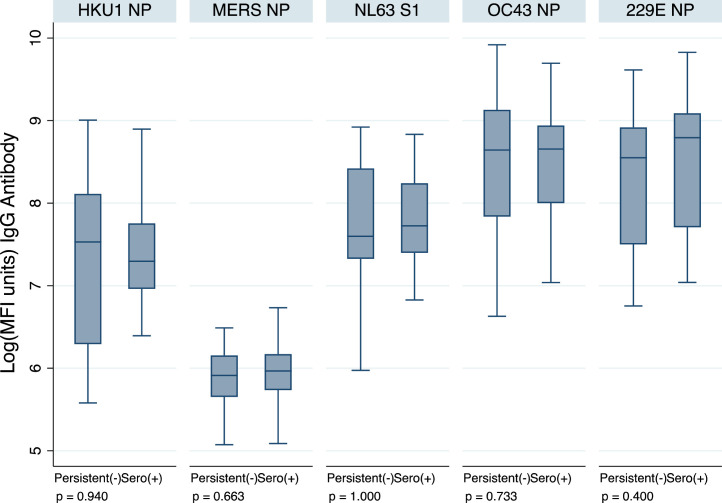

Pre-existing HCoV IgG and ‘acquisition’ of SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated participants

In Goma, 28 of 186 (14%) unvaccinated participants with samples at every time point were initially seronegative but seroconverted or ‘acquired’ SARS-CoV-2 IgG during the study; 23 (12%) participants remained seronegative throughout the follow-up. There were no significant differences in the IgG MFI units to endemic HCoVs at baseline in participants who subsequently went on to acquire SARS-CoV-2 IgG/M compared with those who remained seronegative throughout the follow-up (Figure 2 ). Too few participants remained seronegative during the follow-up in Sierra Leone and Uganda to contribute to this analysis.

Figure. 2.

Human coronavirus IgG MFI units at baseline, comparing 23 participants who remained seronegative during follow-up with 28 participants who were seronegative at baseline and acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection during follow-up (seroconverted to SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain/NP IgG/M at month 2 or 4), in Goma. P-values are for a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Ig, immunoglobulin; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; NP, nucleocapsid protein.

Rate of MFI unit decay among participants unvaccinated and seropositive at baseline

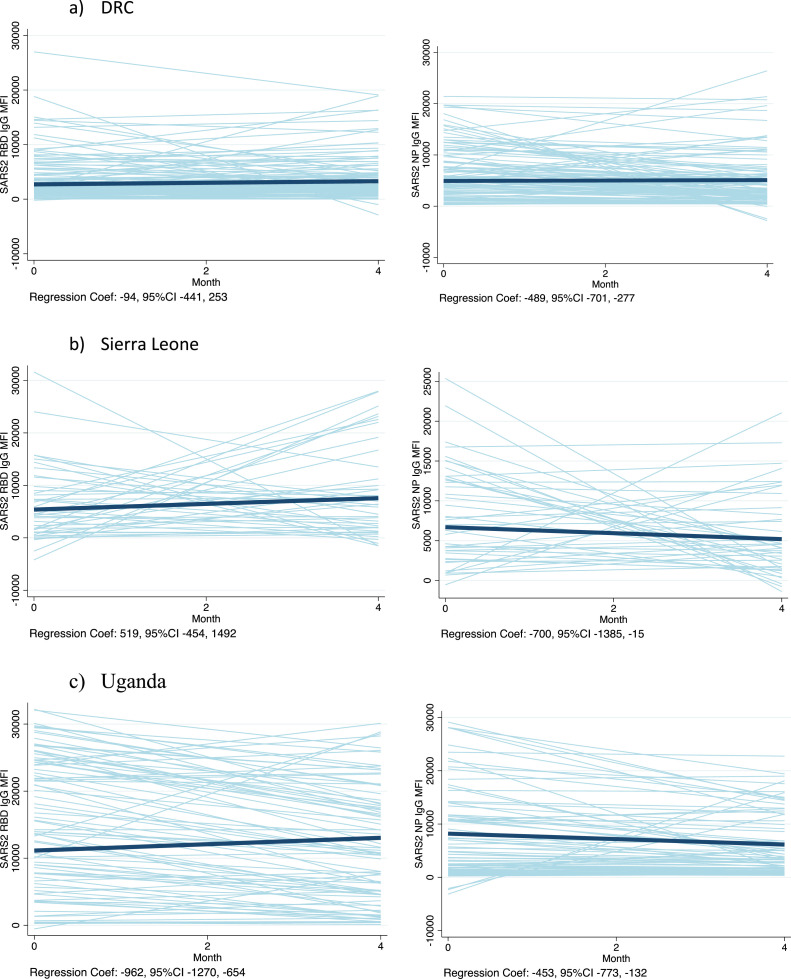

In an analysis of the trend in IgG MFI units over time among unvaccinated participants who were persistently seropositive, the linear regression coefficients indicated MFI waning in Uganda but not in the DRC nor in Sierra Leone (Figure 3 ), controlling for clustering of data by participant with random effects and robust standard errors. In contrast, the IgG to NP waned over time in all three settings (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trends in IgG MFI units to SARS-CoV-2 RBD and NP over time, among those persistently positive for IgG or IgM to RBD or NPa CI, confidence interval; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; Ig, immunoglobulin; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; NP, nucleocapsid protein; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

aSpaghetti plots represent the predicted linear trends for each participant in light blue lines, and the bold line indicates the average slope across participants. The actual linear regression coefficient (slope), controlling for clustering of data by participant with random effects and robust standard errors, is indicated below each graph with its 95% CI. The number of participants included are as follows: DRC n = 119; Sierra Leone n = 41; Uganda n = 83.

Factors associated with remaining seronegative to SARS-CoV-2 among unvaccinated participants

In univariable analyses, sex was the only characteristic that was associated with remaining seronegative compared with participants with at least one seropositive sample in Goma. Male participants had 5.9 times higher odds (95% confidence interval [CI] 2-16) of remaining seronegative than female participants (Supplement Table 5). In this population, there were no differences in the levels of IgG to other endemic HCoVs at baseline among those who remained persistently negative and those who seroconverted (Supplement Figure 4). Too few participants remained seronegative by the end of the study in Sierra Leone and Uganda to complete this analysis in those datasets.

Serological responses to vaccination

In Sierra Leone, 37 of 40 (93%) participants who were vaccinated between baseline and month 2 surveys were seropositive for IgG/M to RBD/N-protein by month 2, but four of these participants had seroreverted by month 4. Eight of the 12 (67%) participants vaccinated between month 2 and 4 had seroconverted by month 4 (Supplement Table 6). When analyzing the IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 RBD alone, by time since first vaccination, 19 of 78 (24%) of IgG responses to RBD were below the threshold defined as ‘seropositive’. The median time since vaccination was 55 days (range 20-93 days) for these samples (Supplement Figure 5). After the second dose, 11 of 33 participants (33%) had not mounted an IgG response to RBD that would be defined as ‘seropositive’ in this study. These samples were taken a median of 36 days after vaccination (range 10-76).

In Uganda, among participants vaccinated before the baseline survey in Uganda, all 34 (100%) were still seropositive by month 4 of follow-up. Among those vaccinated between the baseline and month 2 survey, 98% were seropositive by month 4, and among those vaccinated between month 2 and month 4 surveys, 88% were seropositive at month 4 (Supplement Table 6). When analyzing the IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 RBD by time since vaccination with the first dose, 19 of 128 (15%) of IgG responses to RBD were below the threshold defined as ‘seropositive’—the median time since vaccination was 26 days (interquartile range 14-87) for these samples (Supplement Figure 5).

None of the participants in Goma reported receiving vaccination by the end of the study.

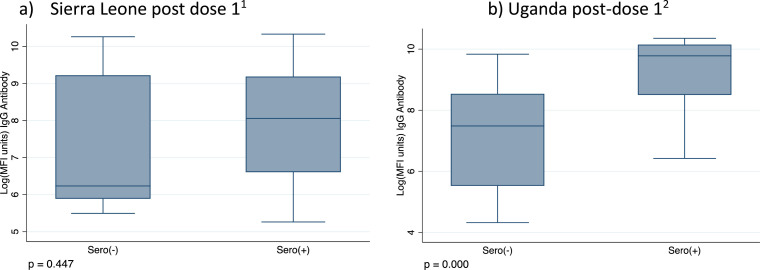

Prevalence of hybrid immunity and its influence on vaccine responses

In Sierra Leone, 70% (43 of 60) of the participants who were vaccinated during the study follow-up period had evidence of natural exposure at baseline, before vaccination, and therefore were likely to have hybrid immunity. There was no evidence of a difference in MFI units after the first dose, comparing those participants who were seronegative at baseline with those seropositive at baseline, restricting to only samples taken at least 14 days after vaccination and controlling for the timing of sample collection since vaccination, but the sample size was small (linear reg coefficient −350; 95% CI −7388-6686; Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

IgG to SARS-CoV-2 RBD >14 days postvaccination with one dose, by serostatus at baseline. Ig, immunoglobulin; IQR, interquartile range; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; NP, nucleocapsid protein; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

aIn Sierra Leone just five seronegative participants at baseline (i.e., seronegative for IgM and IgG to RBD and NP) had a recorded vaccination date and a blood sample >14 days after vaccination (Sero(−) group n = 4), 44 participants were seropositive at baseline (i.e., were seropositive for IgM or IgG to RBD or NP) had a recorded vaccination date and a blood sample >14 days after vaccination (Sero(+) group n = 44); median of 47 days between vaccination and a study sample (IQR 28-56, range 15-79). P-values from the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

bIn Uganda, just 12 unvaccinated and seronegative participants at baseline had a recorded vaccination date after baseline and a blood sample >14 days after vaccination, 96 participants were seropositive at baseline and had a recorded vaccination date after baseline, with a blood sample >14 days after vaccination. Median interval between vaccination and blood sample was 42 days (IQR 28-88). P-values from the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In Uganda, 75% (96 of 120) of the participants who were unvaccinated at baseline and were vaccinated during the study follow-up period and had evidence of natural exposure at baseline and are therefore likely to have hybrid immunity. There was evidence of significantly higher IgG MFI after the first dose among those who were seropositive at baseline than those who were seronegative at baseline, restricting to only samples taken at least 14 days after vaccination and controlling for the timing of sample collection since vaccination (linear reg coefficient 11,904, 95% CI 6233-17,576; Figure 4).

Discussion

We documented 70-90% seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in February-July 2021 among the unvaccinated staff working at health facilities in three distinct settings in sub-Saharan Africa. Very few of the participants who were seronegative at the beginning of the study remained seronegative 4 months later, indicating a high force of infection. Literature indicates that SARS-CoV-2 and other HCoVs are homologous enough for their corresponding antibodies to exhibit cross-binding on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay/multiplex assays [7,9,12] and that this cross-binding can be neutralizing [24]. We found evidence that IgG to SARS-CoV-2 N-protein may cross-bind N-proteins of other endemic HCoVs and that IgG to endemic HCoVs may cross-bind MERS N-protein. It is impossible to determine whether binding IgG results from genuine previous exposure to endemic HCoVs or cross-reactivity within the assay. To attempt to control for this, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence stratified by HCoV serostatus and found no difference in our estimates of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence. However, the numbers of participants with high MFI to endemic HCoVs in some of the comparisons are small.

We found evidence of waning of natural IgG to SARS-CoV-2 RBD in Uganda but not in DRC or Sierra Leone; perhaps the lack of waning was due to natural boosting with repeated re-exposure, a limitation of the study was that we did not collect swab samples for virological analyses. The cross-sectional seroprevalence estimates only provide a snapshot of a dynamic epidemic. The longitudinal follow-up documented how the participants fluctuated between seropositive and seronegative status over time. Pre-existing HCoV IgG did not predict the likelihood of sero-acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 during follow-up in unvaccinated participants, perhaps because of the high force of infection in the study settings. None of the participants reported symptoms during follow-up, and so, we could not analyze the likelihood of symptomatic infection by HCoV serostatus at baseline. Previous studies have indicated that previous exposure to HCoVs may be protective against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 [13,14].

A number of participants in Sierra Leone were seronegative for IgG to RBD 3 or more weeks after vaccination; this was not as much of a problem in Uganda. It may be that participants required more time after vaccination to mount an IgG response to vaccination (given the observational nature of this study, we had no control over when they received vaccination in relation to study visits), or IgG to RBD alone may not be a good marker of vaccination status in our settings. Three-quarters (70-75%) of those vaccinated during follow-up in Sierra Leone and Uganda had evidence of natural immunity before vaccination and therefore had hybrid immunity after vaccination. Previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 correlated with better postvaccination IgG to RBD in Uganda but not in Sierra Leone, the numbers were small in this group and the analysis was limited by the lower IgG responses to vaccination in Sierra Leone. The prevalence of hybrid immunity should be built into predictions of the severity of future waves of the pandemic in these settings [2].

This was an observational cohort; the high SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence at baseline and the start of the COVID-19 vaccination program during follow-up resulted in several analyses containing small numbers of participants, and therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Given the number of antigens, IgGs, and time points, some of the apparent significant findings could have arisen by chance. We had no SARS-CoV-2 virological data and therefore cannot validate our definitions of ‘acquisition of infection’ with antigen data. There may be evidence of more natural boosting (re-exposure) in Sierra Leone and Goma because there was no evidence of waning of MFI units over time among seropositive participants who remained unvaccinated; however, without virological data and/or an estimate of the time of infection, it was difficult to make any conclusions here. SARS-CoV-2 transmission was heterogeneous across time and geography; the findings here do not necessarily represent the overall situation among health care staff across the DRC, Uganda, and Sierra Leone.

Conclusion

There was substantial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among the staff at health care facilities in Goma, DRC; Masaka District, Uganda; and Kambia District, Sierra Leone over a 4-month period. This will have conferred some natural immunity to infection, and subsequent vaccination will confer hybrid immunity. The prevalence of natural infection could be used to inform vaccination policy and prediction models of the impact of subsequent waves of infection in these settings.

Funding

This project was funded by a UKRI (MRC), DHSC (NIHR) research grant (GEC1017, MR/V029363/1, PI Katherine Gallagher). The funder was not involved in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Comite National d'Ethique de la Sante of the DRC, the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review committee, the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee, and local health authorities in each area. Written informed consent was obtained from volunteers before participation.

Author contributions

Conceived & designed the project: K Gallagher, D Watson-Jones, B Greenwood, B Leigh, H Kavunga, E Ruzagira. Collected/ generated project data: K Kasonia, D Tindanbil, J Kitonsa, B Lawal, A Drammeh. Contributed analytic tools: K Tetteh, C Patterson. Performed the analysis: K Gallagher. Initial draft: B Lawal, K Gallagher. Revise and review of all drafts: K Kasonia, D Tindanbil, J Kitonsa, A Drammeh, B Lowe, D Mukadi-Bamuleka, C Patterson, K Tetteh, B Greenwood, M Samai, B Leigh, D Watson-Jones, H Kavunga-Membo, E Ruzagira.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the data collection teams, the health facility staff, and the Ministry of Health officials in the study countries for facilitating the collection of these data. The authors thank Public Health England and NIBSC for supplying the control samples.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.03.049.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.Altarawneh HN, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Tang P, Hasan MR, Yassine HM, et al. Effects of previous infection and vaccination on symptomatic omicron infections. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:21–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SY, Park S, Kim JY, Kim S, Jee Y, Kim SH. Comparison of waning neutralizing antibody responses against the Omicron variant 6 months after natural severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (with or without subsequent coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] vaccination) versus 2-dose COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:2243–2246. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Africa CDC . 2022. COVID-19 Vaccine Dashboard Latest updates from Africa CDC on progress made in COVID-19 vaccinations on the continent.https://africacdc.org/covid-19-vaccination/ [accessed 10 September 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn JS, McIntosh K. History and recent advances in coronavirus discovery. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:S223–S227. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000188166.17324.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santacroce L, Charitos IA, Carretta DM, De Nitto E, Lovero R. The human coronaviruses (HCoVs) and the molecular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Mol Med (Berl) 2021;99:93–106. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-02012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Diseases Control Prevention . 2022. Common human coronaviruses.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/general-information.html#:~:text=Common%20human%20coronaviruses%2C%20including%20types,some%20point%20in%20their%20lives [accessed 11 September 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrwani K, Sharma R, Krishnan M, Jones T, Mayora-Neto M, Cantoni D, et al. Detection of serum cross-reactive antibodies and memory response to SARS-CoV-2 in prepandemic and post-COVID-19 convalescent samples. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:1305–1315. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng KW, Faulkner N, Cornish GH, Rosa A, Harvey R, Hussain S, et al. Preexisting and de novo humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Sci (N Y NY) 2020;370:1339–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.abe1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo L, Wang Y, Kang L, Hu Y, Wang L, Zhong J, et al. Cross-reactive antibody against human coronavirus OC43 spike protein correlates with disease severity in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10:664–676. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1905488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang AT, Garcia-Carreras B, Hitchings MD, Yang B, Katzelnick LC, Rattigan SM, et al. A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: kinetics, correlates of protection, and association with severity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4704. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18450-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Young BE, Li D, Seppo AE, Zhou Q, Wiltse A, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, et al. Broad cross-reactive IgA and IgG against human coronaviruses in milk induced by COVID-19 vaccination and infection. Vaccines. 2022;10:980. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10060980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Li D, Cameron A, Zhou Q, Wiltse A, Nayak J, et al. IgG against human β-coronavirus spike proteins correlates with SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike IgG responses and COVID-19 disease severity. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:474–484. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sagar M, Reifler K, Rossi M, Miller NS, Sinha P, White LF, et al. Recent endemic coronavirus infection is associated with less-severe COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI143380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortega N, Ribes M, Vidal M, Rubio R, Aguilar R, Williams S, et al. Seven-month kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and role of pre-existing antibodies to human coronaviruses. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4740. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24979-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . 2020. Regional Office for Africa. Sierra Leone confirms first case of COVID-19.https://www.afro.who.int/news/sierra-leone-confirms-first-case-covid-19 [accessed 22 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . 2020. Regional Office for Africa. First case of COVID-19 confirmed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.https://www.afro.who.int/news/first-case-covid-19-confirmed-democratic-republic-congo [accessed 22 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olum R, Bongomin F. Uganda's first 100 COVID-19 cases: trends and lessons. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:517–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . 2022. Regional Office for Africa. Nearly 20% of target population vaccinated as Sierra Leone marks one year of COVID-19 vaccine launch.https://www.afro.who.int/countries/sierra-leone/news/nearly-20-target-population-vaccinated-sierra-leone-marks-one-year-covid-19-vaccine-launch [accessed 22 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health policy watch . 2021. DRC finally launches COVID-19 vaccinations after investigating concerns about AstraZeneca.https://healthpolicy-watch.news/dr-congo-finally-launches-covid-19-vaccinations-after-concerns-about-astrazeneca/ [accessed 26 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United nations children's emergency fund Uganda . 2021. Uganda launches first phase of COVID-19 vaccination exercise.https://www.unicef.org/uganda/stories/uganda-launches-first-phase-covid-19-vaccination-exercise [accessed 22 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . 2022. Regional Office for Africa. Africa's COVID-19 vaccine uptake increases by 15%https://www.afro.who.int/news/africas-covid-19-vaccine-uptake-increases-15#:~:text=Brazzaville%20%E2%80%93%20Africa's%20COVID%2D19%20vaccine,health%20impacts%20of%20the%20virus [accessed 26 June 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L, Hall T, Ssewanyana I, Oulton T, Patterson C, Vasileva H, et al. Optimisation and standardisation of a multiplex immunoassay of diverse Plasmodium falciparum antigens to assess changes in malaria transmission using sero-epidemiology. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:26. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14950.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S, Lee Y, Michelow IC, Choe YJ. Global seasonality of human coronaviruses: a systematic review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa443. ofaa443–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyagwange J, Kutima B, Mwai K, Karanja HK, Gitonga JN, Mugo D, et al. Serum immunoglobulin G and mucosal immunoglobulin A antibodies from prepandemic samples collected in Kilifi, Kenya, neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;127:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.