Abstract

Background:

Although effective contraception is strongly recommended during the therapy of women with multiple sclerosis (MS) with some immunomodulatory drugs, unplanned pregnancies still occur. Adequate medication management is essential to avoid foetal harm in the event of an unplanned pregnancy.

Objective:

The aim was to screen for medications used in women of childbearing age with MS that may pose a risk of side effects on foetal development.

Methods:

Sociodemographic, clinical and medication data were collected from 212 women with MS by structured interviews, clinical examinations and medical records. Using the databases from Embryotox, Reprotox, the Therapeutic Goods Administration and on the German summaries of product characteristics, we assessed whether the taken drugs were potentially harmful regarding the foetal development.

Results:

The majority of patients (93.4%) were taking one or more drugs for which a possible harmful effect on the foetus is indicated in at least one of the four databases used. This proportion was even higher in patients who used hormonal contraceptives (birth control pills or vaginal rings) (PwCo, n = 101), but it was also quite high in patients who did not use such contraceptives (Pw/oCo, n = 111) (98.0% and 89.2%, respectively). PwCo were significantly more likely to take five or more medications with potential foetal risk according to at least one database than Pw/oCo (31.7% versus 6.3%). PwCo were also more severely disabled (average Expanded Disability Status Scale score: 2.8 versus 2.3) and more frequently had comorbidities (68.3% versus 54.1%) than Pw/oCo.

Conclusion:

Data on the most commonly used drugs in MS therapy were gathered to study the risk of possible drug effects on foetal development in female MS patients of childbearing age. We found that the majority of drugs used by patients with MS are rated as having a potential risk of interfering with normal foetal development. More effective contraception and special pregnancy information programmes regarding the therapy management during pregnancy should be implemented to reduce potential risks to mother and child.

Plain Language Summary

Use of drugs not recommended during pregnancy by women with multiple sclerosis

Introduction: Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) often have to take different drugs simultaneously. During the therapy with some immunomodulatory drugs, effective contraception is strongly recommended. Nevertheless, unplanned pregnancies occur regularly in women with MS.

Methods: Here, we investigated whether the 212 patients included in this study were taking drugs with known possibility of harm to the development of an unborn child. This was done using four different drug databases.

Results: A subset of 111 patients was not taking hormonal contraceptives (birth control pills or vaginal rings). Of those, 99 patients were taking at least one drug that is not recommended during pregnancy according to at least one of the four databases. Most of the medications taken have the potential to affect normal foetal development.

Conclusion: To ensure safe use of medications, the patients should be reminded of the importance of effective contraception.

Keywords: adverse drug effects, contraception, fertile age, foetal development, multiple sclerosis, pharmacotherapy, women

Introduction

Approximately 2.8 million people live with multiple sclerosis (MS) worldwide.1 This makes MS the most frequent neuroimmunological disease of the central nervous system at a relatively young age. MS is widely heterogeneous in terms of symptoms, histology and radiology.2 The symptoms of MS range from the soft signs, such as fatigue and cognitive changes,3–5 to paralysis, spasticity,4 bladder dysfunction and sexual dysfunction.6,7

The therapeutic management of MS is complex. As a consequence, MS patients often take several medications, resulting in a relatively high risk of polypharmacy (of up to 59%).7 MS is treated with disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) to alleviate disease activity and slow down disease progression. DMDs have been shown to reduce disease severity and curb the development of new lesions in the central nervous system. Further therapeutics are used to treat MS symptoms. Roughly 66.5% of female MS patients suffer from comorbidities, which also need to be treated.3 Moreover, alternative and complementary medicines are used by many patients in addition to prescribed drugs.8 Many DMDs are not recommended for the use in pregnancy. There are known risks for the foetus when taking DMDs and other drugs during pregnancy.9,10 The list of possible side effects for foetuses is long and ranges, for example, from congenital heart defects and hydrocephalus when taking teriflunomide to an increased risk of malformation of the vascular system in embryogenesis when using fingolimod.11,12

Women are three times more likely to be affected by MS than men and the onset of the disease in women is mostly during the women’s childbearing years.13,14 The initial diagnosis of MS can change the way many patients think about family planning. One-third of MS patients who did not become pregnant after diagnosis reported concerns about the possibility of passing MS to the unborn children. They also see MS as an additional burden on the future parenthood.15 The rate of unplanned pregnancies in the general population is around 33–41% worldwide.16–18 Specifically, the respective rate is estimated to be 32% for female MS patients,19 thus representing a significant risk factor to be considered. The German guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of MS do not make a general recommendation for contraceptive use, but they do list DMDs under which a safe contraception should be carried out (e.g. alemtuzumab, cladribine, fingolimod, mitoxantrone, ocrelizumab and teriflunomide).20 There are also official statements in the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use recommending contraceptive use for MS patients.21 When considering the effectiveness of contraceptives, it is important to distinguish between hypothetical effectiveness and actual effectiveness, which could be decreased by inconsequential or inaccurate use.22

In this study, we aimed to determine the frequency of the use of medications not recommended during pregnancy in female MS patients of childbearing age. To this end, we analysed whether the patients in our real-world cohort were taking medicines that are known to have a risk of side effects that may affect the development of a foetus. Our study highlights the importance of an adequate therapy management in light of the risk of unplanned pregnancies.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study was performed at the Department of Neurology at the Rostock University Medical Centre (Germany) and at the Neurological Department of the Ecumenical Hainich Hospital Mühlhausen (Germany) between March 2017 and May 2020. At both centres, patients with MS were treated either as outpatients or as hospitalised inpatients, depending on their disease course and disease activity.

For this cross-sectional study, 212 women of childbearing age from 18 to 48 years were included. They were required to have the diagnosis of a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or MS according to the revised McDonald criteria.23 Moreover, women aged above 48 years were not included, as it is assumed that the onset of menopause typically occurs between the ages of 49 and 52 years.24

During the waiting period for routine examinations at the clinic, outpatients were asked whether they are willing to participate in the study. Patients who were hospitalised for several days due to changes in therapy, therapeutic side effects or acute/ongoing disease activity were also asked if they are interested to participate.

The Ethics Committees of the Rostock University Medical Centre and of the Physicians’ Chamber of Thuringia approved this study (permit numbers A 2014-0089 and A 2019-0048). We conducted this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Collected data

For the patients included, sociodemographic (age, partnership, years of schooling, number of siblings, number of children, employment status, educational status and place of residence), clinical [comorbidities, MS disease course, age at disease onset, disease duration, type of patient care and the degree of disability according to Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)25] and pharmacological data (active agent, drug name, type of application and dosage) were gathered by a structured interview, an anamnesis, clinical neurological examinations and a review of medical records.

Following the suggestions by Laroni et al.26 and Marrie et al.27 (International Workshop on Comorbidities in MS), comorbidities were defined based on patient interviews, medical expertise and clinical records.

Drug characterisation

The term ‘drug’ refers to both individual active agents and combinations of active agents that are marketed as medications. Only those drugs that were actually taken by the patients were included in the analysis. The drugs were classified according to the prescription status, the interval of the drug use and according to the treatment goal.

Prescription status: Prescription (Rx) or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs.

Interval of drug use: Acute drug use (drugs on demand, DOD) or drug use in regular intervals (e.g. weekly or monthly) for long-term treatment of diseases (long-term drugs, LTD).

Therapeutic goal: Immunomodulatory MS drugs (DMDs), symptomatic MS drugs or drugs to treat comorbidities (not related to MS) or drugs for other conditions (e.g. contraception, which here means the use of an oral hormonal contraceptive or the use of vaginal rings at the time of data collection).

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy was defined as the simultaneous intake of at least five drugs. This definition is most commonly used in the literature.28

Assessment of the drugs according to the suitability in pregnancy

The classification of the safety of drugs with regard to their suitability for the use during pregnancy was based on four different sources of information: the Embryotox database,29,30 the register of the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA),31 the German online portal of summaries of product characteristics (SmPC)32,33 and the Reprotox database.34 The drug safety classification took place from June to August 2020. We entered both individual active substances and combinations of active substances in the databases.

Each database is based on a different classification to describe the drug effects (Supplementary Table 1). Each drug was searched in the respective database, and the risk rating was recorded. The following categories were considered to indicate a potentially harmful effect during pregnancy: category red in Embryotox; category B3, C, D and X in TGA; category 2, 3 and 4 in SmPC; category 3 in Reprotox.

Based on the information from each database, we classified the drugs that were used by the patients into the following: (1) no harmful effects for the foetus or newborn are to be expected, (2) the data situation is insufficient and therefore the drug use during pregnancy cannot be recommended and (3) the drug may interfere with the normal development of a foetus.

We then calculated how many women with MS were taking drugs that potentially have harmful effects when used during pregnancy according to at least one database, according to ⩾ 2 or ⩾ 3 databases or consistently according to all 4 databases. We also calculated how many patients were simultaneously taking two, three, four or more drugs that are categorised as posing a risk to foetal development in at least one database.

Statistics

PASW Statistics 27 (IBM) was used for analysing the sociodemographic, clinical and pharmacological data. Descriptive statistics included frequencies, medians and ranges, and means and standard deviations. The patient cohort was divided into patients using either birth control pills or vaginal rings as contraceptives (PwCo) and patients not using such contraceptives (Pw/oCo) and patients with and without polypharmacy. Two-tailed Student’s t tests, chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for the comparative analysis of patient groups and a significance level of α = 0.05 was set. Using a false discovery rate (FDR)35 of 5%, the alpha error accumulation caused by multiple testing was corrected.

Results

Clinical and demographic data

The study population consisted of 212 women with an average age of 36.3 ± 7.6 years. Most women were employed (52.8%), skilled workers (60.4%) and living in a partnership (75.5%). One-third of the female patients lived in a rural community (35.9%). Almost 40% of the women with MS were taking five or more medications (39.2%). The mean age at the onset of MS was 27.8 ± 7.2 years, with a median disease duration of 7 years (range, 0–30 years) and a median EDSS score of 2.0 (range, 0.0–8.0). The most common disease course was relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS, 85.8%), followed by secondary progressive MS (SPMS, 7.1%), CIS (6.1%) and primary progressive MS (PPMS, 1.0%). Most women had at least one concomitant disease in addition to MS (60.9%), with the number of concomitant diseases ranging from zero to seven (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, clinical and pharmaceutical data of female MS patients of childbearing age stratified by contraceptive use.

| Characteristic | Total patient cohort (n = 212) |

Patients using contraceptivesa

(n = 101) |

Patients using no contraceptivesa

(n = 111) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data | ||||

| Age at data acquisition (years), M (SD) [range] | 36.3 (7.6) [19–48] | 36.6 (7.0) [19–48] | 36.0 (8.1) [19–48] | 0.501t |

| School years, median [range] | 10 [8–18] | 10 [8–14] | 10 [8–18] | 0.205U |

| Educational level, n (%) | 0.086Chi | |||

| No training | 13 (6.1) | 3 (3.0) | 10 (9.0) | |

| Skilled worker | 128 (60.4) | 67 (66.3) | 61 (55.0) | |

| Technical college | 27 (12.7) | 9 (8.9) | 18 (16.2) | |

| University | 44 (20.8) | 22 (21.8) | 22 (19.8) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | 0.760Chi | |||

| In training | 7 (3.3) | 3 (3.0) | 4 (3.6) | |

| In studies | 5 (2.4) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Employed | 112 (52.8) | 50 (49.5) | 62 (55.9) | |

| Unemployed | 11 (5.2) | 7 (6.9) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Disability pensioned | 69 (32.5) | 36 (35.6) | 33 (29.7) | |

| Others | 8 (3.8) | 3 (3.0) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Partnership, n (%) | 0.524Fi | |||

| Single | 52 (24.5) | 27 (26.7) | 25 (22.5) | |

| Any partnership | 160 (75.5) | 74 (73.3) | 86 (77.5) | |

| Place of residence, n (%) | 0.499Chi | |||

| Rural community | 76 (35.9) | 35 (34.7) | 41 (36.9) | |

| Provincial town | 38 (17.9) | 15 (14.9) | 23 (20.7) | |

| Medium-sized town | 34 (16.0) | 16 (15.8) | 18 (16.2) | |

| City | 64 (30.2) | 35 (34.7) | 29 (26.1) | |

| No. children, n (%) | 0.861Chi | |||

| 0 | 84 (39.6) | 43 (42.6) | 41 (36.9) | |

| 1 | 51 (24.1) | 24 (23.8) | 27 (24.3) | |

| ⩾2 | 77 (36.3) | 34 (33.6) | 43 (38.8) | |

| No. siblings, n (%) | 0.199Chi | |||

| 0 | 25 (11.8) | 10 (9.9) | 15 (13.5) | |

| 1 | 140 (66.0) | 66 (65.3) | 74 (66.7) | |

| ⩾2 | 47 (22.2) | 25 (24.8) | 22 (19.8) | |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Patient care, n (%) | 0.128Fi | |||

| Outpatient | 169 (79.7) | 76 (75.2) | 93 (83.8) | |

| Inpatient | 43 (20.3) | 25 (24.8) | 18 (16.2) | |

| Age at MS onset (years), M (SD) [range] | 27.8 (7.2) [12–47] | 28.1 (6.5) [12–47] | 27.5 (7.9) [12–47] | 0.497t |

| Disease duration (years), median [range] | 7 [0–30] | 7 [0–30] | 6 [0–26] | 0.316U |

| EDSS, median [range] | 2.0 [0–8] | 2.0 [0–8] | 2.0 [0–7.5] | 0.022 U |

| Disease course, n (%) | 0.206Chi | |||

| CIS | 13 (6.1) | 5 (5.0) | 8 (67.2) | |

| RRMS | 182 (85.8) | 84 (83.2) | 98 (88.3) | |

| SPMS | 15 (7.1) | 11 (10.9) | 4 (3.6) | |

| PPMS | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| No. comorbidities, n (%) | 0.009Chi * | |||

| 0 | 83 (39.1) | 32 (31.7) | 51 (45.9) | |

| 1 | 56 (26.4) | 24 (23.8) | 32 (28.8) | |

| 2 | 40 (18.9) | 29 (28.7) | 11 (9.9) | |

| 3 | 18 (8.5) | 7 (6.9) | 11 (9.9) | |

| 4 | 9 (4.2) | 4 (4.0) | 5 (4.5) | |

| ⩾5 | 6 (2.9) | 5 (5.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Pharmaceutical data | ||||

| Polypharmacy, n (%) | <0.001 Fi ** | |||

| No | 129 (60.8) | 41 (40.6) | 88 (79.3) | |

| Yes | 83 (39.2) | 60 (59.4) | 23 (20.7) | |

| No. drugs taken, median [range] | ||||

| All drugs | 4 [0–15] | 5 [1–15] | 3 [0–11] | <0.001 U ** |

| Rx drugs | 2 [0–14] | 4 [0–14] | 2 [0–7] | <0.001U ** |

| OTC drugs | 1 [0–6] | 1 [0–6] | 1 [0–5] | 0.753U |

| DOD | 0 [0–7] | 0 [0–7] | 0 [0–4] | 0.339U |

| LTD | 3 [0–11] | 4 [0–11] | 2 [0–9] | <0.001U ** |

| DMDsb | 1 [0–2] | 1 [0–2] | 1 [0–1] | 0.003 U * |

| Symptomatic drugs | 1 [0–9] | 1 [0–9] | 1 [0–5] | 0.053U |

| Comorbidity drugs | 2 [0–10] | 2 [0–10] | 1 [0–6] | <0.001 U ** |

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; DMDs, disease-modifying drugs for MS; DOD, drugs on demand; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; FDR, false discovery rate; LTD, long-term drugs; MS, multiple sclerosis; n, number of patients; No., number of; OTC, over-the-counter; p, p-value; PPMS, primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS, relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis; Rx, prescription; SD, standard deviation; SPMS, secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; Significance values <0.05 are indicated in bold.

FDR < 0.05. **FDR < 0.001.

The grouping of patients was based on the use of either birth control pills or vaginal rings as hormonal contraceptives.

The use of methylprednisolone was counted within the DMD category.

Chi-squared test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Two-sample two-tailed Student’s t test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Use of contraceptives

Among the patients analysed, 101 women (47.6%) reported taking oral contraceptives or using vaginal rings (PwCo group). Polypharmacy was three times more frequent among PwCo than in Pw/oCo (59.4% versus 20.7%). PwCo took significantly more medications than Pw/oCo (medians of 5 versus 3 medications). This was also reflected by significant differences between PwCo and Pw/oCo with respect to the use of long-term medications, Rx medications, DMDs and comorbidity medications, with PwCo taking significantly more of those medications than Pw/oCo (p ⩽ 0.003). SPMS was more common in PwCo than in Pw/oCo (10.9% versus 3.6%). The average EDSS score was significantly higher in PwCo (2.8 versus 2.3). PwCo also had significantly more comorbidities than Pw/oCo (chi-square test: p = 0.009). There were no other significant differences between the two groups in the dataset (Table 1). For similar comparisons related to the polypharmacy status of the patients, the reader is referred to the Supplementary Tables 2–5.

Risk assessment of medications in terms of the potential harmfulness in pregnancy

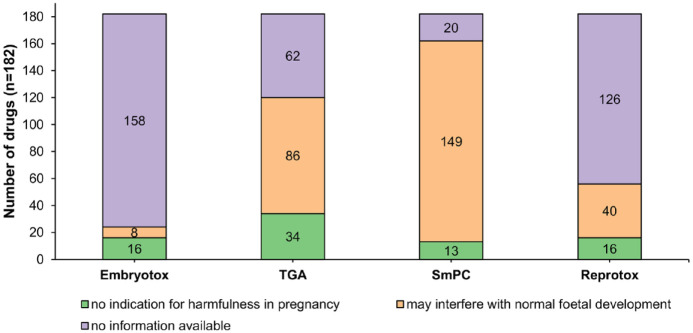

The 212 patients took a total of 182 different drugs. The classification of the 182 different medications varied widely across the four databases. The number of drugs classified as potentially harmful during pregnancy per database ranged from 8 (Embryotox) to 149 (SmPC). The number of drugs classified as ‘no indication of harmfulness in pregnancy’ per database ranged from 13 (SmPC) to 34 (TGA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Drug assessment based on databases recording potential effects during pregnancy. A total of 182 different drugs were taken by the MS patients and classified based on different sources of information (Embryotox, TGA, SmPC and Reprotox). The figure shows the proportions of drugs, which were classified as not harmful in pregnancy or potentially interfering with the foetal development. For some drugs, no information was available in the databases.

n, number of drugs; SmPC, summaries of product characteristics; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration.

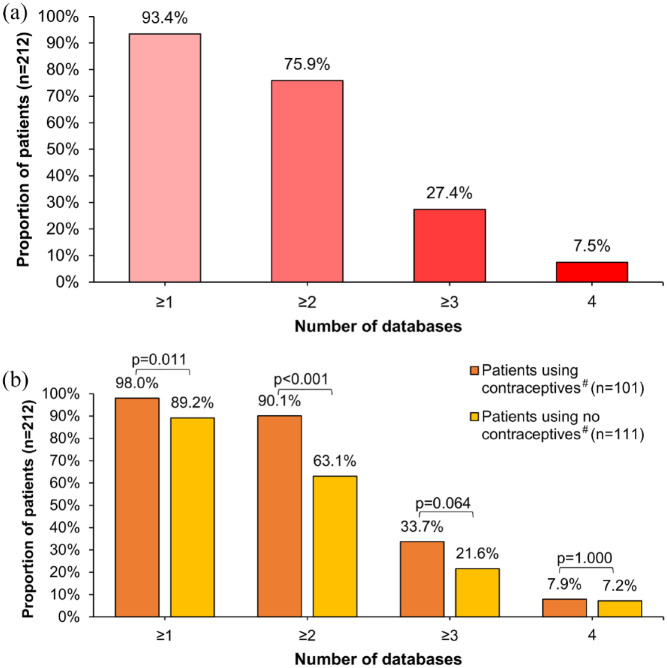

A few patients (6.6%) took either no medication (n = 3) or only medications that were not rated as potentially harmful in any of the four databases used (n = 11). Conversely, more than 93% of the patients (n = 198) had at least one drug in their medication plan that is not recommended during pregnancy according to at least one database. In 7.5% of the patients analysed, at least one medication taken was classified as potentially harmful to the foetus in all four databases [Figure 2(a)]. The patients took a median of three drugs that were classified as potentially harmful during pregnancy in at least one database. One in five women (18.4%) took at least five medications classified as potentially harmful in at least one database (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of female MS patients taking at least one drug not recommended during pregnancy stratified by the level of evidence. Shown is the proportion of women taking at least one drug classified as ‘not recommended during pregnancy’ stratified by the number of databases (a) for the entire study population (n = 212) and (b) for the subgroups PwCo (n = 101) and Pw/oCo (n = 111). More than 90% of the patients took ⩾ 1 drug not recommended during pregnancy by ⩾ 1 of the 4 databases used. Exactly 7.5% of the patients used ⩾ 1 drug that was consistently classified as potentially harmful for the foetal development in all four databases. PwCo took significantly more often ⩾ 1 drug with potential harmfulness in pregnancy according to at least one or two databases than Pw/oCo.

n, number of patients; p, p value (Fisher’s exact test); PwCo, patients using contraceptives#; Pw/oCo, patients using no contraceptives#.

#The grouping of patients was based on the use of either birth control pills or vaginal rings as hormonal contraceptives.

Table 2.

Proportion of female MS patients taking one or more drugs not recommended during pregnancy according to at least one database.

| No. of drugs with potential risk for the foetus | Total patient cohort (n = 212) |

Patients using contraceptivesa

(n = 101) |

Patients using no contraceptivesa

(n = 111) |

p Chi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 14 (6.6%) | 2 (2.0%) | 12 (10.8%) | <0.001** |

| 1 | 39 (18.4%) | 6 (5.9%) | 33 (29.7%) | |

| 2 | 50 (23.6%) | 17 (16.8%) | 33 (29.7%) | |

| 3 | 41 (19.3%) | 23 (22.8%) | 18 (16.2%) | |

| 4 | 29 (13.7%) | 21 (20.8%) | 8 (7.2%) | |

| ⩾5 | 39 (18.4%) | 32 (31.7%) | 7 (6.3%) |

FDR, false discovery rate; MS, multiple sclerosis; n, number of patients; p, p value.

Shown is the number (percentage) of patients who took none, one or more drugs with potentially harmful effects on the foetus or newborn according to at least one of the four databases used; Significance values <0.05 are indicated in bold.

The grouping of patients was based on the use of either birth control pills or vaginal rings as hormonal contraceptives.

Chi-squared test.

FDR <0.001

Almost all PwCo (98.0%) took at least one medication that was classified as potentially harmful in at least one database [Figure 2(b)]. In Pw/oCo, the respective proportion was significantly lower but still high (89.2%, Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.011). This was also reflected by the fact that PwCo took more medications classified as potentially harmful for the foetus according to at least one database than Pw/oCo (median: 4 versus 2, Mann–Whitney U test: p < 0.001). PwCo were five times more likely to take five or more medications with possible foetal risk according to at least one database than Pw/oCo (31.7% versus 6.3%) (Table 2).

Risk classification of drugs frequently used

The most frequently used DMDs were interferon (IFN) beta-1a (12.7%), glatiramer acetate (GA) (12.3%) and fingolimod (9.9%) (Table 3). The most commonly used non-DMDs were cholecalciferol (43.9%), ibuprofen (18.9%) and levothyroxine (14.2%). Three of these six drugs (IFN-beta-1a, fingolimod and ibuprofen) were classified as potentially harmful to the unborn child when taken during (unplanned) pregnancy by two databases. Among the most commonly used drugs, cholecalciferol, immunoglobulin G and magnesium were not found to be potentially harmful during pregnancy in any database. GA, which was classified as potentially harmful only in the SmPC, was used twice as often by Pw/oCo than by PwCo (17.1% versus 6.9%, Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.035) A complete list of drugs used with the respective risk classification is given in Supplementary Table 6.

Table 3.

Most frequently used drugs with level of evidence of potentially harmful effects on foetal development during pregnancy.

| Drug | Total patient cohort (n = 212) |

Patients using contraceptivesa (n = 101) | Patients using no contraceptivesa

(n = 111) |

p Fi | No. of databases indicating potential foetal risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMDs | |||||

| IFN beta-1a | 27 (12.7%) | 15 (14.9%) | 12 (10.8%) | 0.415 | 2 |

| GA | 26 (12.3%) | 7 (6.9%) | 19 (17.1%) | 0.035 | 1 |

| Fingolimod | 21 (9.9%) | 10 (9.9%) | 11 (9.9%) | 1.000 | 2 |

| Alemtuzumab | 17 (8.0%) | 9 (8.9%) | 8 (7.2%) | 0.801 | 1 |

| Methylprednisoloneb | 16 (7.5%) | 16 (15.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 ** | 2 |

| Natalizumab | 16 (7.5%) | 12 (11.9%) | 4 (3.6%) | 0.035 | 2 |

| Dimethyl fumarate | 15 (7.1%) | 5 (5.0%) | 10 (9.0%) | 0.293 | 1 |

| Teriflunomide | 14 (6.6%) | 5 (5.0%) | 9 (8.1%) | 0.416 | 3 |

| Ocrelizumab | 8 (3.8%) | 7 (6.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.029 | 3 |

| Immunoglobulin G | 7 (3.3%) | 3 (3.0%) | 4 (3.6%) | 1.000 | 0 |

| Cladribine | 4 (1.9%) | 2 (2.0%) | 2 (1.8%) | 1.000 | 3 |

| Mitoxantrone | 3 (1.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.8%) | 1.000 | 1 |

| Azathioprine | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 1.000 | 3 |

| IFN beta-1b | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.476 | 2 |

| Non-DMDs | |||||

| Cholecalciferol | 93 (43.9%) | 41 (40.6%) | 52 (46.8%) | 0.407 | 0 |

| Ibuprofen | 40 (18.9%) | 19 (18.8%) | 21 (18.9%) | 1.000 | 2 |

| Levothyroxine | 30 (14.2%) | 30 (29.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001** | 1 |

| Magnesium | 27 (12.7%) | 14 (13.9%) | 13 (11.7%) | 0.684 | 0 |

| Pantoprazole | 24 (11.3%) | 20 (19.8%) | 4 (3.6%) | <0.001** | 2 |

| Cyanocobalamin | 21 (9.9%) | 9 (8.9%) | 12 (10.8%) | 0.819 | 1 |

| Enoxaparin | 17 (8.0%) | 16 (15.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | <0.001** | 2 |

| Ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel | 14 (6.6%) | 14 (13.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001** | 2 |

| Zopiclone | 13 (6.1%) | 10 (9.9%) | 3 (2.7%) | 0.042 | 2 |

| Baclofen | 11 (5.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 3 (2.7%) | 0.122 | 3 |

| Escitalopram | 11 (5.2%) | 6 (5.9%) | 5 (4.5%) | 0.760 | 2 |

DMDs, disease-modifying drugs for MS; FDR, false discovery rate; MS, multiple sclerosis; n, number of patients; non-DMDs, drugs other than DMDs taken by more than 5% of the patients with MS; p, p value.

Shown is the number (percentage) of patients using the drug and the number of databases containing the information that the drug may interfere with normal foetal development, with a larger number of databases indicated by a darker red colour; Significance values <0.05 are indicated in bold.

FDR < 0.001.

The grouping of patients was based on the use of either birth control pills or vaginal rings as hormonal contraceptives.

Quarterly pulse therapy or acute relapse therapy.

Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

The onset of MS in women typically occurs during their childbearing years. Female patients are usually treated with DMDs, some of which carry a teratogenic risk (e.g. fingolimod and teriflunomide).36 In this study, we performed a comprehensive evaluation of drugs used by women with MS in childbearing age with regard to the potential risk of harmful effects on the unborn child in the case of an unplanned pregnancy. For this purpose, four different evidence-based drug databases were used to assess this risk. Earlier studies provided information about potential influences on the normal foetal development when taking selected medications during pregnancy.11 The special feature of our study is that we present an assessment of 182 different drugs and that we included both DMDs and non-DMDs (i.e. symptomatic MS therapeutics and comorbidity drugs).

We found that 93.4% of the patients of childbearing age took one or more drugs for which a possible harmful effect on the foetus is indicated in at least one database. Therefore, the use of effective contraceptives is an important issue in the MS treatment management. Hormonal contraception is one of the safest ways to prevent an unintended pregnancy,37 and in Germany, the ‘pill’ is the most commonly used contraceptive (47%), followed by male condoms (46%) and intrauterine devices (10%).38 A previous study reported that 40.0% of the patients with MS used combined oral contraceptives in the past.39 In our study, the proportion of patients taking birth control pills or vaginal rings was 47.6%. However, as a limitation, we did not take into account other contraceptive methods. There are multiple reasons for this. On the one hand, we did not ask whether the woman had undergone sterilisation or whether her partner uses condoms for contraception. On the other hand, contraceptives are not regularly listed in the medication plans (due to an insufficient exchange between treating physicians and because some contraceptives, e.g. copper-containing intrauterine devices, are classified as medical devices40 rather than drugs41) and some patients do not disclose their use (often because they do not consider them to be a medication). Therefore, we do not know the exact proportion of patients who did not use contraceptives at all and the individual reasons for this decision.

Although it is recommended in the German guidelines for the treatment of MS that effective contraception should be ensured when administering certain DMDs (e.g. cladribine, fingolimod, mitoxantrone, ocrelizumab or teriflunomide),20 there are no explicit statements to use or avoid specific contraceptive methods. However, guidelines for the use of contraceptives in MS patients can be found in the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use.21 According to these recommendations, women with MS with prolonged immobility should use levonorgestrel-releasing or copper-containing intrauterine devices (grade 1) rather than combined hormonal contraceptives (grade 3) because of concerns about possible venous thromboembolism, whereas no restrictions apply to women with MS without prolonged immobility.37 There are also recommendations for contraceptive use at the international level by the World Health Organisation.42 However, these do not provide any specific guidance for patients with MS.

For long-term therapy planning, physicians should regularly check the patient’s desire to have a child. A drug review should be conducted if the patient wishes to become pregnant to evaluate the entire current medication for reproductive toxicity. In particular, the use of DMDs for the treatment of MS in women who wish to become pregnant should always be based on an individual consideration of risks and benefits.43 There are DMDs for which foetal risks cannot be excluded. Discontinuing the therapy with such DMDs in patients with a desire to become pregnant serves to protect an unborn child from potential consequences on its development.44–47 For the mother, however, the discontinuation of DMD treatment implicates an increased risk of disease activity in the period up to conception and until after birth, although it has been established that the rate of MS relapses is markedly decreased during pregnancy.48 Therefore, in women with MS who wish to become pregnant, the use of DMDs that are contraindicated in pregnancy might be discontinued in a controlled manner or, depending on the patient’s history of disease activity, switched to a therapy with IFN-beta or GA, as these DMDs are considered safe in the first weeks of pregnancy for both the mother and the child.33

IFN-beta-1a (which was taken by 12.7% of our patients) and GA (which was taken by 12.3% of our patients) were the most commonly used DMDs in our study. According to the SmPC, there is no evidence of an increased foetal risk when using IFN-beta-1a in the first trimester,33 but there are insufficient data for the second and third trimesters. The SmPC also states that animal studies suggested an increased risk of spontaneous abortions following IFN-beta administration. However, in humans, no correlation between the use of IFN-beta-1a in early pregnancy and an increased rate of spontaneous abortions was found.49 Giannini et al.50 reported seven spontaneous abortions in 88 pregnancies exposed to IFN-beta and one spontaneous abortion in 17 pregnancies exposed to GA. The respective risks of spontaneous abortion are comparable to that of the general population.51 According to the German guidelines20 and the European guidelines52 on the pharmacological treatment of MS, the therapy with GA and IFN-beta can be thus continued until pregnancy is confirmed and also continuing this therapy during pregnancy may be considered in some cases if there is a high risk of disease reactivation.

Some experts recommend the same approach when using natalizumab, which received 7.5% of our patients. Accordingly, the therapy with natalizumab might not be stopped until pregnancy is achieved or even until week 34 of pregnancy.53,54 The patient can be actively involved in such a treatment decision after full discussion of potential implications. However, in our study, we did not ascertain whether some of the patients had consciously decided not to use contraception and to continue the therapy after consulting their doctor. We also did not survey whether the patients would like to receive a better counselling from the neurologist on the use of medications in the context of pregnancy.

Fingolimod and teriflunomide, which were taken by 9.9% and 6.6% of the patients in our study, respectively, carry a potential risk of an abnormal foetal development according to information from the SmPC and TGA. In preclinical studies, fingolimod was found to be associated with an increased teratogenic risk.55 The use of fingolimod during pregnancy is contraindicated, as a doubled risk of congenital malformations has been shown.33 Women of childbearing age are therefore advised to use effective contraception methods during fingolimod therapy.33 After discontinuation of fingolimod, a washout period of at least 2 months prior to conception is recommended.33 Contraception should be continued during the washout period. In our cohort, there were 9 women taking teriflunomide and 11 women taking fingolimod despite not using oral contraceptives or vaginal rings. Although other contraceptive methods may have been used, this may indicate the need that the treating physician should regularly check that appropriate contraception is being followed in female MS patients of childbearing age.

The timing is an important factor in assessing potential risks to foetuses. This applies, for instance, to the DMDs cladribine and alemtuzumab which are administered in annual treatment cycles and can provide long-term disease control. In our study, a subset of 8.0% and 1.9% of the patients, respectively, were on these DMDs at the time of data collection (i.e. they received a dose within the past year). It is currently advised that conception should not be attempted until at least 6 months after cladribine intake and until at least 4 months after the last dose of alemtuzumab, ideally until the end of the treatment cycle.20,33 Another example where the duration and frequency of drug administration matters is corticosteroid pulse therapy: 12 of our patients received intravenous methylprednisolone (which has a short half-life) quarterly for 3–5 consecutive days. In our study, we always considered all the drugs in the medication plans, regardless of their time window of action. Our risk assessment is thus overly conservative, which leads to an overestimation of the actual risk of drug exposure and side effects under (unplanned) pregnancy.

In addition to DMDs, many MS patients have to be treated with symptomatic MS drugs and drugs for comorbidities (not related to MS) or other conditions. In our study, 43.9% of the patients took vitamin D supplements in the form of cholecalciferol, albeit there is currently no conclusive evidence for the benefit of cholecalciferol in MS. Some studies reported a reduction in disease activity,56,57 whereas other studies failed to identify definitive benefits from the treatment with cholecalciferol in patients with MS.58,59 The use of cholecalciferol in pregnancy does not need to be restricted according to the information from all four databases used. However, an issue that should not be neglected is the correct and adequate use of cholecalciferol. Prolonged excess of vitamin D intake can lead to intoxication with devastating consequences, such as pancreatitis or kidney failure.60,61 Approximately 10% of the patients in our study were taking magnesium and cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12), respectively. Interest in such nutritional supplements has increased among MS patients in recent years.62 Dietary supplements might have a positive influence on the quality of life of MS patients,63,64 but further clinical trials are needed to gain a deeper understanding of the use of taking dietary supplements in MS.62

Ibuprofen was the second most commonly used non-DMD in our study. It is often used in the treatment of MS symptoms.65 However, patients with MS also use ibuprofen to treat flu-like symptoms that can occur after the administration of IFN-beta preparations.66 Women becoming aware of their pregnancy are advised to avoid ibuprofen because of the risks it poses for the foetus. Ibuprofen is even contraindicated in the third trimester because it has been associated with foetal renal dysfunction and cardiopulmonary abnormalities according to the SmPC.33 In this study, we did not distinguish between different levels of risk across the trimesters. It should be noted that, while various medicines are known to have a potentially harmful effect in the first two trimesters, such as carbamazepine and phenprocoumon,33 there is typically much less data on the safety of drugs in the third trimester, because in clinical studies, the medication is generally stopped when pregnancy is known, and real-world evidence is often limited.

In this study, we used data from four different databases to assess for each drug whether there is a potential risk of harmful effects on unborn children. To our knowledge, no previous study has assessed the potential harmfulness of drugs to foetuses in patients with MS on the basis of multiple databases in a real-world setting. However, the information provided by the individual databases is very heterogeneous in terms of harmfulness and up-to-dateness. Some of the databases are incomplete. For example, the Embryotox database currently lacks some DMDs for the treatment of MS, such as ocrelizumab and cladribine. Because of the different rating scales (Supplementary Table 1), it is rather difficult to make a consistent statement about the harmfulness of each drug to the unborn child.

Focused and frequent consultations between MS patients and treating physicians with regard to medications, side effects and planned pregnancies can be very useful and should be extended. These could improve the use of contraceptives in women with MS to reduce the likelihood of unplanned pregnancies and drug-exposed pregnancies. A review that was composed of information from 25 different randomised controlled trials pointed out the positive effects of motivational interviewing in terms of effective contraception in women.67 Early planning and open consultations allow for adequate medication changes and necessary washout periods of medications with potential foetal risk. The treating physician should openly discuss the possible risks of Rx and OTC medications in the context of an intended or unplanned pregnancy with the patients. It would also be important to improve the interdisciplinary cooperation between the various specialists, such as family doctors, gynaecologists, pharmacists and neurologists. An early and timely expression of a pregnancy wish allows all specialties to jointly prepare a medication plan that would be well adapted to the needs of the mother and her foetus.

This study has several limitations. Due to the cross-sectional design of this study, we did not capture changes in the patient’s medication use over time. Therefore, longitudinal data are needed to conduct further investigations. The limited number of patients impeded to draw firm conclusions on the use of individual drugs or drug combinations in women with MS of childbearing age. Because this study was conducted in Germany, it is also not possible to make generalised statements on the use of DMDs for MS and contraceptives in other countries. We grouped the patients by the use of oral contraceptives or vaginal rings. However, other contraceptive methods, such as transdermal patches, intrauterine devices, female sterilisation and barrier methods of contraception, were not considered in this work. Of note, in the United States, unlike in Germany,38 female sterilisation is the most commonly used contraceptive method (with high proportions in women aged 30 years and older), followed by oral contraceptive pills (which are preferred by women below the age of 30 years).68 Furthermore, the recording of OTC drugs taken was based on the information provided by the patients and may not be accurate due to erroneous omission of medications during the interview. Finally, we focused on women of childbearing age in this study, but male fertility may also be affected by MS medication use, which could be analysed in more detail as well.

Conclusion

In this study, data from four different databases on a wide spectrum of drugs were collected to analyse whether women with MS (n = 212) used drugs with known possibility of harm to the development of an unborn child if taken during an (unplanned) pregnancy. We found that 89.2% of the female MS patients who did not use birth control pills or vaginal rings for contraception took at least one medication that was classified as posing a potential risk to the foetus according to at least one database. A percentage of 6.3% of these women were even taking five or more drugs for which at least one database indicated that they may have harmful effects during pregnancy. Furthermore, 7.5% of all women were taking drugs for which potential harmful effects were consistently recorded in all four databases used. An improved communication between neurologists, gynaecologists, pharmacists and the patients is needed to ensure that the use of DMDs fits well with the family planning and is in line with current treatment recommendations for MS. The issue of contraception should be regularly discussed with the patient to prevent an unintended pregnancy and avoid possible drug side effects to mother and child.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-6-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nurses and physicians of the outpatient and inpatient MS wards of the Department of Neurology at the Rostock University Medical Centre and the Neurological Department of the Ecumenical Hainich Hospital Mühlhausen for providing help in the data acquisition.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Marie-Celine Haker  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2725-6156

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2725-6156

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Marie-Celine Haker, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Gehlsheimer Str. 20, 18147 Rostock, Germany.

Niklas Frahm, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany.

Michael Hecker, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany.

Silvan Elias Langhorst, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany.

Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany.

Jane Louisa Debus, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany.

Barbara Streckenbach, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany; Department of Neurology, Ecumenic Hainich Hospital gGmbH, Mühlhausen, Germany.

Julia Baldt, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany; Department of Neurology, Ecumenic Hainich Hospital gGmbH, Mühlhausen, Germany.

Felicita Heidler, Department of Neurology, Ecumenic Hainich Hospital gGmbH, Mühlhausen, Germany.

Uwe Klaus Zettl, Neuroimmunology Section, Department of Neurology, Rostock University Medical Center, Rostock, Germany.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The Ethics Committees of the Rostock University Medical Centre and of the Physicians’ Chamber of Thuringia approved this study (permit numbers A 2014-0089 and A 2019-0048). We conducted this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study participation of the patients was on a voluntary basis. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in advance.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Marie-Celine Haker: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Resources; Visualisation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Niklas Frahm: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Michael Hecker: Conceptualisation; Supervision; Visualisation; Writing – review & editing.

Silvan Elias Langhorst: Data curation; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Pegah Mashhadiakbar: Data curation; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Jane Louisa Debus: Writing – review & editing.

Barbara Streckenbach: Data curation; Validation.

Julia Baldt: Data curation; Validation.

Felicita Heidler: Data curation; Validation.

Uwe Klaus Zettl: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Methodology; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: N.F. received travel funds for research meetings from Novartis. M.H. received speaking fees and travel funds from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis and Teva. U.K.Z. received speaking fees, travel support and financial support for research activities from Alexion, Almirall, Bayer, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Octapharma, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva and EU, BMBF, BMWi and DFG. M-C.H., S.E.L., P.M., J.L.D., B.S., J.B. and F.H. declare no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets generated and analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 2020; 26: 1816–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Filippi M, Bar-Or A, Piehl F, et al. Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frahm N, Hecker M, Zettl UK. Polypharmacy in patients with multiple sclerosis: a gender-specific analysis. Biol Sex Differ 2019; 10: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, et al. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15: 210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, et al. Fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis – pathogenesis, clinical picture, diagnosis and treatment. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2015; 83: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rommer PS, Eichstädt K, Ellenberger D, et al. Symptomatology and symptomatic treatment in multiple sclerosis: results from a nationwide MS registry. Mult Scler 2019; 25: 1641–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frahm N, Hecker M, Zettl UK. Polypharmacy among patients with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative systematic review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2020; 19: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kochs L, Wegener S, Sühnel A, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Complement Ther Med 2014; 22: 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vukusic S, Michel L, Leguy S, et al. Pregnancy with multiple sclerosis. Rev Neurol 2021; 177: 180–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Langer-Gould AM. Pregnancy and family planning in multiple sclerosis. Continuum 2019; 25: 773–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Varytė G, Arlauskienė A, Ramašauskaitė D. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: an update. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2021; 33: 378–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varytė G, Zakarevicˇienė J, Ramašauskaitė D, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: an update on the disease modifying treatment strategy and a review of pregnancy’s impact on disease activity. Medicina 2020; 56: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bove R, Chitnis T. The role of gender and sex hormones in determining the onset and outcome of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bove R, Alwan S, Friedman JM, et al. Management of multiple sclerosis during pregnancy and the reproductive years: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124: 1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alwan S, Yee IM, Dybalski M, et al. Reproductive decision making after the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS). Mult Scler 2013; 19: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barton K, Redshaw M, Quigley MA, et al. Unplanned pregnancy and subsequent psychological distress in partnered women: a cross-sectional study of the role of relationship quality and wider social support. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017; 17: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huynh ST, Yokomichi H, Akiyama Y, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with unplanned pregnancy among women in Koshu, Japan: cross-sectional evidence from Project Koshu, 2011-2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020; 20: 397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wasswa R, Kabagenyi A, Atuhaire L. Determinants of unintended pregnancies among currently married women in Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr 2020; 39: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith AL, Cohen JA, Ontaneda D, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: risk of unplanned pregnancy and drug exposure in utero. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2019; 5: 2055217319891744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN) e. V. Diagnose und Therapie der Multiplen Sklerose, Neuromyelitis-optica-Spektrum-Erkrankungen und MOG-IgG-assoziierten Erkrankungen, https://dgn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/030050_LL_Multiple_Sklerose_2021.pdf (2021, accessed 19 September 2022).

- 21. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016; 65: 1–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011; 83: 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takahashi TA, Johnson KM. Menopause. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99: 521–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laroni A, Signori A, Maniscalco GT, et al. Assessing association of comorbidities with treatment choice and persistence in MS: a real-life multicenter study. Neurology 2017; 89: 2222–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marrie RA, Miller A, Sormani MP, et al. Recommendations for observational studies of comorbidity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2016; 86: 1446–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dathe K, Schaefer C. The use of medication in pregnancy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2019; 116: 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dathe K, Schaefer C. Drug safety in pregnancy: the German Embryotox institute. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2018; 74: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. TGA. Therapeutic Goods Administration, https://www.tga.gov.au (2022, accessed 19 September 2022).

- 32. Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. Fachinformation (SPC), https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Arzneimittel/Zulassung/Fachinformation_SPC.html (2006, accessed 19 September 2022).

- 33. Rote Liste® Service GmbH. Fachinfo-Service, https://www.fachinfo.de/ (2022, accessed 19 September 2022).

- 34. Fitzpatrick RB. REPROTOX: an information system on environmental hazards to human reproduction and development. Med Ref Serv Q 2008; 27: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thöne J, Thiel S, Gold R, et al. Treatment of multiple sclerosis during pregnancy – safety considerations. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017; 16: 523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Houtchens MK, Zapata LB, Curtis KM, et al. Contraception for women with multiple sclerosis: guidance for healthcare providers. Mult Scler 2017; 23: 757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hedda N. So verhüten die Deutschen (Statista), https://de.statista.com/infografik/19403/so-verhueten-die-deutschen/ (2019, accessed 19 September 2022)

- 39. Hellwig K, Chen LH, Stancyzk FZ, et al. Oral contraceptives and multiple sclerosis/clinically isolated syndrome susceptibility. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0149094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. Medizinprodukte, https://www.bfarm.de/DE/Medizinprodukte/_node.html (2022, accessed 19 September 2022).

- 41. Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. Arzneimittel, https://www.bfarm.de/DE/Arzneimittel/_node.html (2022, accessed 19 September 2022).

- 42. World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549158 (2015, accessed 19 September 2022). [PubMed]

- 43. Mendibe Bilbao M, Boyero Durán S, Bárcena Llona J, et al. Multiple sclerosis: pregnancy and women’s health issues. Neurologia (Engl Ed) 2019; 34: 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Portaccio E, Annovazzi P, Ghezzi A, et al. Pregnancy decision-making in women with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: I: fetal risks. Neurology 2018; 90: e823–e831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alroughani R, Alowayesh MS, Ahmed SF, et al. Relapse occurrence in women with multiple sclerosis during pregnancy in the new treatment era. Neurology 2018; 90: e840–e846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berenguer-Ruiz L, Gimenez-Martinez J, Palazón-Bru A, et al. Relapses and obstetric outcomes in women with multiple sclerosis planning pregnancy. J Neurol 2019; 266: 2512–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Villaverde-González R, Candeliere-Merlicco A, Alonso-Frías MA, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis to plan a pregnancy: a retrospective registry study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020; 46: 102518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, et al. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler 2011; 17: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Giannini M, Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes after Glatiramer Acetate exposure in patients with multiple sclerosis: a prospective observational multicentric study. BMC Neurol 2012; 12: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nybo Andersen AM, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, et al. Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ 2000; 320: 1708–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2018; 24: 96–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dobson R, Dassan P, Roberts M, et al. UK consensus on pregnancy in multiple sclerosis: ‘Association of British Neurologists’ guidelines. Pract Neurol 2019; 19: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Demortiere S, Rico A, Maarouf A, et al. Maintenance of natalizumab during the first trimester of pregnancy in active multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2021; 27: 712–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Singer BA. Initiating oral fingolimod treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2013; 6: 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Laursen JH, Søndergaard HB, Sørensen PS, et al. Vitamin D supplementation reduces relapse rate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016; 10: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Soilu-Hänninen M, Aivo J, Lindström BM, et al. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial with vitamin D3 as an add on treatment to interferon β-1b in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83: 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jagannath VA, Filippini G, Di Pietrantonj C, et al. Vitamin D for the management of multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 9: CD008422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yeh WZ, Gresle M, Jokubaitis V, et al. Immunoregulatory effects and therapeutic potential of vitamin D in multiple sclerosis. Br J Pharmacol 2020; 177: 4113–4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rolf L, Muris A-H, Bol Y, et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation in multiple sclerosis: symptoms and biomarkers of depression. J Neurol Sci 2017; 378: 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rutkowski M, Grzegorczyk K. Adverse effects of antioxidative vitamins. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2012; 25: 105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tryfonos C, Mantzorou M, Fotiou D, et al. Dietary supplements on controlling multiple sclerosis symptoms and relapses: current clinical evidence and future perspectives. Medicines 2019; 6: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rommer PS, König N, Sühnel A, et al. Coping behavior in multiple sclerosis-complementary and alternative medicine: a cross-sectional study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2018; 24: 784–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mische LJ, Mowry EM. The evidence for dietary interventions and nutritional supplements as treatment options in multiple sclerosis: a Review. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2018; 20: 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Río J, Nos C, Bonaventura I, et al. Corticosteroids, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen for IFNbeta-1a flu symptoms in MS: a randomized trial. Neurology 2004; 63: 525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Reess J, Haas J, Gabriel K, et al. Both paracetamol and ibuprofen are equally effective in managing flu-like symptoms in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients during interferon beta-1a (AVONEX) therapy. Mult Scler 2002; 8: 15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lopez LM, Grey TW, Chen M, et al. Theory-based interventions for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 11: CD007249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-49: United States, 2017-2019. NCHS Data Brief 2020; 388: 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-6-taw-10.1177_20420986221143830 for Therapy of women with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of the use of drugs that may have adverse effects on the unborn child in the event of (unplanned) pregnancy by Marie-Celine Haker, Niklas Frahm, Michael Hecker, Silvan Elias Langhorst, Pegah Mashhadiakbar, Jane Louisa Debus, Barbara Streckenbach, Julia Baldt, Felicita Heidler and Uwe Klaus Zettl in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety