Abstract

Upon ligand binding to a G protein–coupled receptor, extracellular signals are transmitted into a cell through sets of residue interactions that translate ligand binding into structural rearrangements. These interactions needed for functions impose evolutionary constraints so that, on occasion, mutations in one position may be compensated by other mutations at functionally coupled positions. To quantify the impact of amino acid substitutions in the context of major evolutionary divergence in the G protein–coupled receptor subfamily of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), we combined two phylogenetic-based algorithms, Evolutionary Trace and covariation Evolutionary Trace, to infer potential structure–function couplings and roles in mGluRs. We found a subset of evolutionarily important residues at known functional sites and evidence of coupling among distinct structural clusters in mGluR. In addition, experimental mutagenesis and functional assays confirmed that some highly covariant residues are coupled, revealing their synergy. Collectively, these findings inform a critical step toward understanding the molecular and structural basis of amino acid variation patterns within mGluRs and provide insight for drug development, protein engineering, and analysis of naturally occurring variants.

Keywords: G protein–coupled receptor, G protein, structure–function, protein evolution, coevolutionary signals

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are class C G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that play essential roles in modulating synaptic transmission and plasticity in the central nervous system (1). Given the wide range of therapeutic potential of mGluRs in neuronal and psychiatric disorders, including pain regulation, drug addiction, depression, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), there have been concerted efforts to understand the relationships between structure and function of mGluRs. Previous studies on conformational dynamics and dimerization compatibility of mGluRs contributed significantly to understanding activation mechanisms and establishing pharmacological profiles (8, 9, 10); however, less is known about the residues involved in these behaviors.

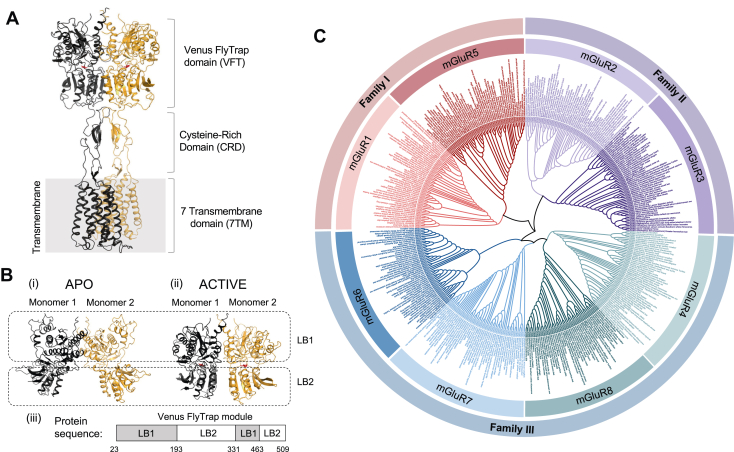

Five main classes of GPCRs (class A, B, C, F, and adhesion) evolved from a common ancestor and share a structural feature of seven transmembrane helices (7TMs) (11, 12). Unlike other classes, the uniqueness of class C receptors such as mGluRs lies in obligate dimerization and distinctively large N-terminal extracellular domains composed of a venus flytrap (VFT) module and cysteine-rich domain (13, 14) (Fig. 1A). Full-length mGluR structures were recently solved and demonstrated that ligand binding at the VFT triggers a large conformational change of the VFT from an open to a closed state, causing subsequent changes in residue interactions and domain rearrangement of the cysteine-rich domain and 7TMs (9, 14, 15, 16) (Fig. 1B). In addition, emerging evidence in dimerization compatibility between mGluR subtypes and asymmetric activations provide additional complexity in their signaling mechanisms by expanding impacts of mGluR subtype–specific ligands (17).

Figure 1.

Structure and phylogenetic tree of mGluRs.A, mGluRs are composed of structurally independent venus flytrap (VFT) domain, cysteine-rich domain (CRD), and seven transmembrane helices (7 TM) and function as obligate dimers. Active-state homodimerized mGluR5 with bound ligand (red) is shown (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 6N51(9)). B, VFT domain dimers are shown in (i) Apo (PDB ID: 6N52 (9)) and (ii) active (PDB ID: 6N51 (9)) states. Each VFT contains two lobes, named ligand binding 1 (LB1) domain and ligand binding 2 (LB2) domain. (iii) The protein sequence regions contributing to LB1 and LB2. C, A phylogenetic tree including homologous protein sequences from mGluR1 to mGluR8. mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptor.

To disentangle this complexity, it is critical to explain the functional impacts of residues and their functional connectivity in mGluRs. Pattern recognition applied to naturally occurring variations over evolution can provide pivotal information about protein properties, such as structure, stability, interactions, and functional sites (18, 19, 20). In the evolution of mGluRs, a single encoded mGluR in invertebrates was duplicated into eight subtypes (mGluR1–mGluR8) in vertebrates and its functions diversified as the nervous system became more complex (21, 22, 23, 24). The eight mGluRs are divided into three families based on sequence identity and receptor function. Group I (mGluR1 and mGluR5) stimulates phospholipase C via coupling to Gαq/11, which leads to elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels, whereas group II (mGluR2 and mGluR3) and group III (mGluR4, mGluR6, mGluR7, and mGluR8) activate Gαi/o, which can inhibit adenylate cyclase or regulate ion channels (25, 26). Despite this functional divergence, mGluR subtypes share a common dimer interface (15) and highly conserved residues at the endogenous ligand-binding pocket (27). In addition, identification of mGluR subtypes in different vertebrates that play similar roles in signal transduction (28, 29, 30) suggests that evolutionarily preserved features exist across species (ortholog) and between mGluR subtypes (paralog).

Here, we apply a phylogenetic approach to disentangle the functional impacts of individual residues and their connectivity in mGluRs. To quantify the patterns of naturally occurring amino acid variation over evolution, we used in silico tools real-valued Evolutionary Trace (rvET) (31) and a recent Covariation ET (CovET) on the eight subtypes of mGluRs in vertebrates. rvET predicts the functional impact of individual residue positions based on the correlation of their amino acid substitutions with phylogenetic divergence. Building upon rvET, CovET further computes the degree of amino acid covariation between pairs of residue positions. We confirmed that residues of evolutionary importance as measured by rvET are notably condensed near endogenous ligand and allosteric ligand-binding sites, the dimer interface, and the sixth TM helix. Moreover, highly covaried residue pairs are likely to make contact in an mGluR structure. Of note, when compared with other open source covariation algorithms, including statistical coupling analysis (SCA) (32), direct-coupling analysis (DCA) (33), EVfold (34), Evcoupling (35), Mip (36), and direct information (DI) (37), CovET shows improvements in identifying contact residue pairs, located at a distance in the primary sequence, and better clustered in the folded structure. Phenotypic characterization of long-distance highly covaried residue pairs presents functional relatedness, where the effect of a residue position is influenced by another. These data demonstrate the potential to map functional coupling in known structures and identify long-range determinants of cooperativity.

Results

Highly ranked rvET residues display mGluR-specific patterns in a structure

In order to quantify the relative functional importance of individual residue positions in mGluRs, we aligned amino acid sequences of eight subtypes of mGluRs from mGluR1 to mGluR8 in vertebrates, the evolutionary clade they arose in (Fig. 1C). mGluR residue numbering in this study was based on human mGluR5 and generic seven TMs numbering scheme was followed according to the study by Pin et al. (38) for class C GPCRs and Ballesteros–Weinstein (39) for class A GPCRs. The rvET algorithm (31) was applied to this multiple sequence alignment (MSA) to rank individual residues based on how amino acid substitutions at individual residue positions accompany the divergence of the entire sequence into evolutionary branches. Mathematically, the raw rvET rank ρ, at a given position i, is computed by summing the Shannon entropy (40) over every subsequent subalignment of g, defined by the phylogenetic tree (41, 42) (Fig. 2A). Consequently, the more substitutions a position has which do not track with phylogenetic divergence, the more it will be penalized by added Shannon entropy terms, leading to larger values of ρ. Following past convention, we converted the raw value of rvET ρ into rankings in percentile of 0 to 100, with a rvET rank of 100 representing the greatest penalty and the least likely inferred functional importance.

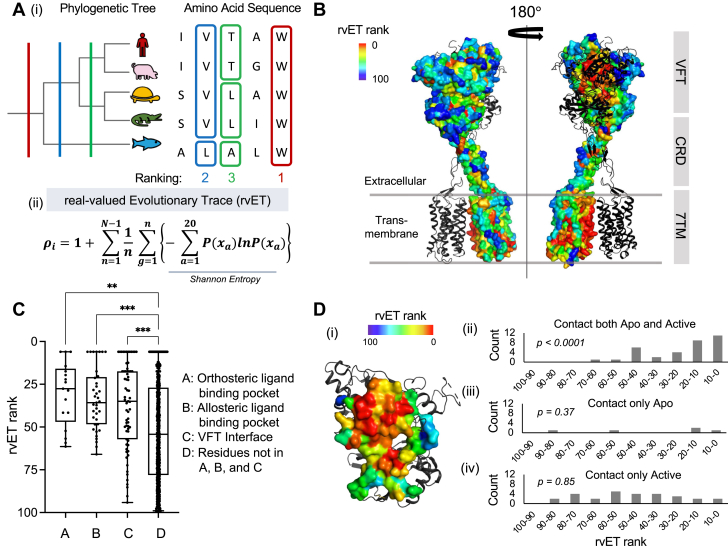

Figure 2.

Evolutionary Trace identifies functionally important residues.A, Schematic view of rvET algorithm workflow. Applying correlations between amino acid substitutions and phylogenetic tree, each residue position is ranked based on the occurrence of variations over major evolutionary divergences. (i) An invariant position (red) is the rank highest, and then a position where variations are occurred at larger branches in the phylogenetic tree (blue) is ranked higher than a position with variations in smaller branches (green). (ii) Measurement of rvET rank, ρ, at position i is shown, where N-1 represents all possible branches in the phylogenetic tree, g is subalignment defined by the phylogenetic tree branches, and P(xa) is the frequency of amino acid type, a, at a given position i. B, Individual residue rvET ranks are mapped onto mGluR structure (Protein Data Bank ID: 6n51 (9)) and colored in rainbow scheme. C, Highly ranked residues by rvET algorithm are located at known functional sites of the receptors; orthosteric ligand-binding pocket, allosteric ligand-binding pocket, and interface residues. p Value of Kruskal–Wallis test is 0.0057, 0.0004, and 0.0002, respectively. D, (i) Dimer interface contact residues (<8 Å) are shown and colored by rvET rank. (ii–iv) rvET rank distributions are plotted into three types of residue interface contacts: (ii) contacts maintaining from apo to active state (iii) contacts only apo state (iv) contacts only active state. p Value of Kruskal–Wallis test is <0.0001, 0.37, and 0.85, respectively. rvET, real-valued Evolutionary Trace.

Color-coding residues by rvET rank revealed significant clustering of highly ranked residues within the mGluR structure (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the contribution of these residues to characterized functional sites, residues were classified according to their proximity to known functional sites in published structures. Residues were defined as being located at orthosteric or allosteric ligand-binding pockets if their minimum distances to the ligands in structures of complexes are less than 4 Å (SI Appendix and Table S1). Two different distance criteria were compared for residues at the VFT dimer interface: ≤4 Å or ≤8 Å (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S1). Compared with the rest of the protein, residues located at these three functional sites—orthosteric and allosteric ligand-binding pockets, and VFT dimer interface—are biased toward high rvET rank, with p values of 0.0057, 0.0004, and 0.0002, respectively (Kruskal–Wallis test) (Fig. 2C). Further analysis of the VFT dimer interface showed that comparison of active (agonist-bound) and inactive (apo) structures revealed that most (34 of 39) of the residues satisfying the 8 Å proximity criterion at the VFT dimer interface do so in both states. Such residues were strongly biased to top rvET ranks (Kruskal–Wallis test p < 0.0001) as compared with nonclassified residues, suggesting that the dimer interface in the apo state might hold evolutionary constraints in dimer propensities between mGluR subtypes. This strong bias was not evident in those residues that form intersubunit interactions only in the active state (Kruskal–Wallis test p = 0.85) (Fig. 2D). These data confirmed that residues involved in primary functions of the mGluRs were identified by rvET.

In addition to those known functional sites, we also observed top rvET ranks concentrated on the helix sixth of the TM domain. As in other classes of GPCRs, the TM segments of mGluRs play a pivotal role in signaling by coupling with corresponding downstream effectors such as heterotrimeric G-proteins and β-arrestins. To test whether GPCRs share similar molecular features, we explored the evolutionary pressures on 7TMs of mGluRs and compared them with those of three class A GPCRs with different ligand types: dopamine receptors (aminergic ligands), vasopressin receptors (peptide ligands), and cannabinoid receptors (lipid ligands) (Fig. 3). We observed that relative functional importance from the first helix to fourth helix follows similar trends between GPCRs, while variations are observed between GPCRs for other helices. Notably, sixth helix (TM6) is the most functionally important helix for mGluRs, and the median ranking is also the highest in comparison with class A GPCRs (Fig. 3). Indeed, 92% (24 of 26) of residues located in TM6 of mGluRs are either invariant or subtype-specific variant amino acid substitutions across different vertebrates: 69% (18 of 26) of residues located on TM6 of mGluR are highly conserved across different vertebrates as well as mGluR subfamily, and the other 23% (6 of 26) of residues are subtype-specific variants (6.38, 6.40, 6.57, 6.58, 6.59, and 6.60, Appendix and Fig. S2). Together, our phylogenetic lineage analysis with rvET demonstrated that amino acid substitution patterns over evolutionary divergence reflects protein functionality, by recovering the sites of ligand binding and dimer interfaces for mGluRs. In addition, residues on TM6 of mGluRs are highly intolerant of variations over evolution compared with class A GPCRs. These data show distinctive molecular features of mGluRs, implying that they might have evolved under different mechanistic pressures from those acting on class A GPCRs.

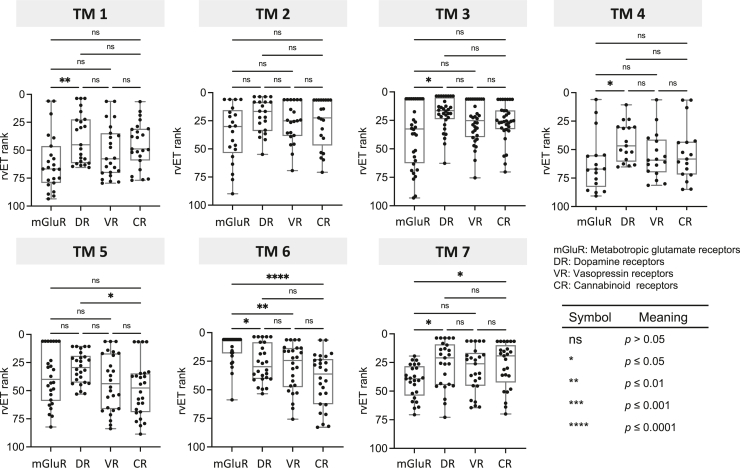

Figure 3.

rvET rank distributions on7TMare compared byeachhelixbetween metabotropic glutamate receptors(mGluRs) andthreeother class A G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Each data point represents rvET rank of a residue position on the corresponding TM region and receptor. CR, cannabinoid receptor; DR, dopamine receptor; rvET, real-valued Evolutionary Trace; VR, vasopressin receptor.

Pairwise amino acid covariations between residue positions in mGluRs provide structural information

We demonstrated that variations in amino acid substitutions over major evolution divergences are nonrandomly associated with mGluR functionality. Building upon the rvET analysis, we next asked whether similar quantitative patterns could be found among amino acid variations in pairs of residue positions. For this analysis, we applied the CovET algorithm, which follows the same framework as rvET by penalizing nonconcerted amino acid variations on a given residue pair i and j, iteratively through the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4A). Consequently, the ranking of residue pairs takes into account both pairwise amino acid variations and phylogenetic information over the evolutionary timescale. This scheme yields an overall profile of substitutions among residue pairs. For our analysis, we converted the raw value of CovET into rankings in percentile of 0 to 100, with a CovET score of 0 representing the most highly covaried pairs.

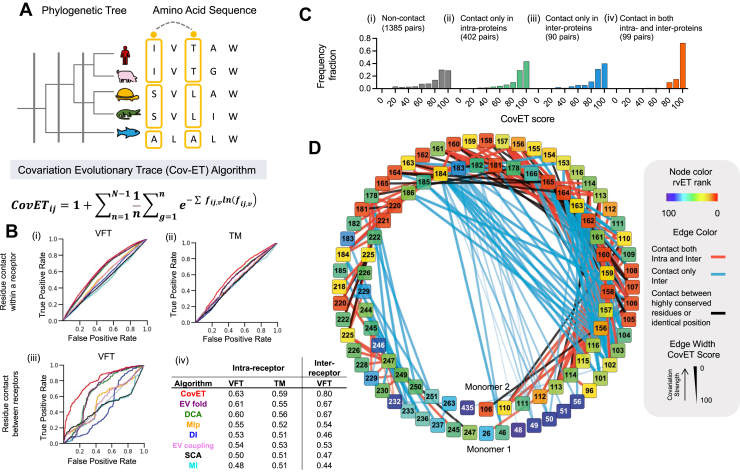

Figure 4.

Covariation of amino acid residues predicts structural proximity.A, Schematic view of CovET algorithm workflow. On a given residue pair I and j, N-1 represents all possible branches in phylogenetic tree, g is subalignment defined by phylogenetic tree branches, and fijv is frequency of nonconcerted variations, v, at a given residue pair i and j. The highlighted positions illustrate co-occurrence of amino acid substitutions over major evolutionary divergences. B, Prediction of structural residue proximity was measured by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) in intrachain residues on (i) venus flytrap (VFT) and (ii) transmembrane (™) excluding neighboring residues of 12, in which |Residue1 - Residue2|>12, and (iii) dimer interface residue contacts on VFT. (iv) Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUCs) from (i–iii) are listed. C, CovET score distributions in four different groups of residue pairs located at the dimer interface. (Skewness of the graphs are (i) −1.48, (ii) −2.00, (iii) −1.73, (iv) −3.40; kurtosis of the graphs are (i) 1.49, (ii) 3.45, (iii) 2.62, (iv) 14.60). D, Dimer contacting residue pairs that are shown in C (iii–iv) are visualized in a network graph. CovET, covariation ET.

To investigate the structural features of coupled residues according to CovET, we measured the predictions of structural contact by a receiver operating characteristic curve. The computed area under the curve (AUC) gauges the extent to which structural contact residue pairs match the covariation score. An AUC of 0.5 is random and implies a lack of discrimination. To capture all possible residue contacts, taking into account the plasticity of the mGluR structures, a minimum atomic distance of 8 Å between two residue pairs was defined based on 38 different mGluR structures in protein data bank (PDB) (SI Appendix and Table S2). Since sequentially neighboring residues tend to be contiguous with each other in a folded protein structure, AUC was computed after removing sequence neighbors (SI Appendix and Fig. S3A). In comparison with seven other covariation algorithms (EVfold, EVcoupling, DI, DCA, MIp, MI, and SCA), CovET captured more structural contact pairs and performed notably better in predicting contacts between residues distant in the primary sequence (Fig. 4B, SI Appendix and Fig. S3A). Moreover, highly covaried residue pairs in the VFT were also likely in contact at the dimer interface (Fig. 4B). Indeed, CovET captured a broad spectrum of residue contacts including not only contacts within a domain but also intersubunit contacts. CovET scores of contact residues were highly negatively skewed (biased toward high CovET ranks) compared with pairs not in contact (Fig. 4C). The dimer interface residue contacts were mapped on a network graph where edge width represents CovET strength (Fig. 4D), confirming that CovET assigned greater weights to interprotein contacts than other algorithms (SI Appendix and Fig. S4). We also observed that highly covaried residue pairs identified by CovET were structurally clustered, further showing that as a group they are nonrandomly distributed in the protein structure. To quantify structural clustering, the top 50 most highly covaried residue pairs ranked by different algorithms were analyzed using selection clustering weight (SCW) z-score (43). SCW z-score measures the statistical significance of structural clustering of a selected set of residues in comparison with expected values from randomly selected sets of the same size. A higher z-score represents increased significance of the extent of clustering of the selected set of residues on the structure. Residue pairs captured by CovET had the highest SCW z-score of 4.21, whereas top-ranked pairs determined by other methods were widely spread over the structure and yielded z-scores ranging from −3.24 to 2.66 (SI Appendix and Fig. S3B). Unlike other covariation algorithms that calculate the most commonly covarying residue pairs across a family, CovET incorporates the divergences at different evolutionary stages by quantifying amino acid variations in every branch in the phylogenetic tree. Our method also does not penalize pair conservation as in other methods. We hypothesize that these differences account for the improved performance identifying more direct residue contacts both within domains and at the dimer interface in the mGluR structure.

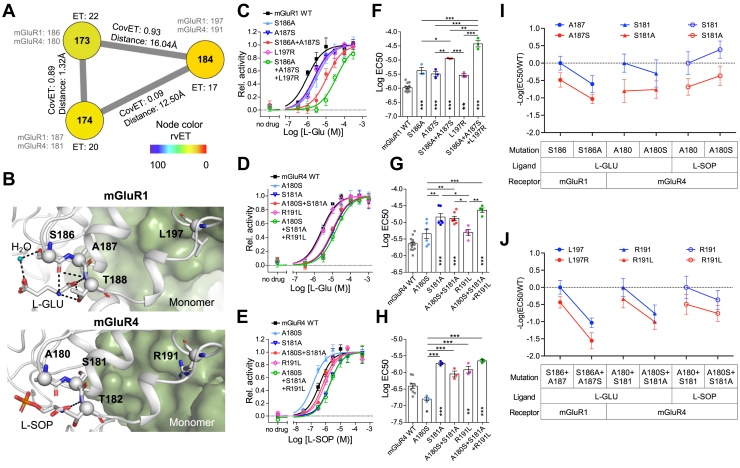

Epistatic interactions are observed between highly covaried pairs of residues at 173/174/184

Although a large proportion of highly ranked CovET residue pairs were in structural proximity, others were not. To test whether these might still have joint functional roles despite their spatial separation, we assayed G-protein activation after mutationally swapping mGluR residues with a specific focus on 173, 174, and 184 among the potential candidates fell into false positives (distance >8 Å) in the structural proximity test (Fig. 4). These selected three positions were predicted to be functionally impactful by rvET and highly covaried with each other by CovET, although residue pairs 173–184 and 174–184 are spatially far apart, 16.04 Å and 12.50 Å, respectively (Fig. 5A). Position 173 and 174 are in the ligand-binding pocket of the VFT and displays subtype-specific amino acid conservation across species. Serine 173 is highly conserved in group I mGluRs, and its hydroxyl group (-OH) interacts with the orthosteric ligand l-glutamate (l-Glu) via a water molecule, whereas the corresponding position within group II and III mGluRs is a conserved alanine. Interestingly, the amino acid at position 174 has an opposite pattern. It is conserved as alanine in group I but serine in group II and III. On the other hand, position 184 is located at the dimer interface and is far from the ligand-binding pocket (Fig 5B, SI Appendix and Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

Epistatic interactions between highly covaried pairs of residues.A, ET, CovET scores, and minimum residue distance on the selected three residue pairs are shown. B, Highly covaried residue pairs 173–174–184, corresponding positions for mGluR1 are 186–187–197 and for mGluR4 are 180–181–182, are show in a protein structure (mGluR1 Protein Data Bank: 1ewk (16) and mGluR4 Protein Data Bank: 7e9h (84)). The green surface represents the opposite monomer in a dimerized conformation. C–H, Functional effects of swapped mutation pairs. C, Representative dose–response curves of mGluR1 with l-glutamate (l-Glu), (D) mGluR4 with l-Glu, and (E) mGluR4 with l-serine-O-phosphate (l-SOP) are shown normalized to tops and bottoms of curve fits. Points represent means ± SEM of three technical replicates. F–H, EC50 values derived from dose–response curves. Points represent means from independent experiments; bars show overall mean ± SEM. All pairs within groups were compared using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-test; asterisks on the bars show comparison with WT. I–J, Epistasis interactions are examined in the comparisons of single and double mutations. CovET, covariation ET; ET, Evolutionary Trace; mGluR1, metabotropic glutamate receptor 1.

To determine the functional relatedness of pairs of residues, amino acids in mGluR1 (group I mGluRs) were swapped to the corresponding positions in mGluR4 (group III mGluRs) and vice versa. We examined mutational effects of single and double or triple mutants. In functional assays of G-protein activation via endogenous Gαq for mGluR1 and cotransfected chimeric Gαqo (44) for mGluR4, the ability of mutants to mediate Ca2+ release from internal stores was measured with two endogenous ligands: l-glutamate (l-Glu), which binds to all mGluRs, and l-serine-O-phosphate (l-SOP), which specifically activates group III mGluRs. On mGluR1, all mutants (S186A, A187S, S186A + A187S, L197R, and S186A + A187S + L197R) had reduced potency (EC50) of activation in response to l-Glu (Fig. 5, C and F), whereas none of the mutations conferred gain-of-function activation by l-SOP (SI Appendix and Fig. S6O). On mGluR4 with l-Glu, all mutants except A180S and R191L significantly reduced potency of activation (Fig. 5, D and G), whereas with l-SOP, potency was reduced for S181A, R191L, and A180S + S181A + R191L but increased for A180S, and the double mutant, A180S + S181A, recovered l-SOP potency toward wildtype (WT) level (Fig. 5, E and H). Overall, these data reveal that compensatory effects depend on the mGluR subfamily type and ligand, as we observed with the mGluR4 mutant A180S + S181A in response to l-SOP. No significant differences in surface expression were observed for these mutants (SI Appendix and Fig. S7). Efficacy of mGluR4 mutants was not significantly altered except for a slight increase of R191L with l-Glu, whereas the mGluR1 mutants all had increased efficacy with l-Glu, compared with WT (SI Appendix and Fig. S6, M, N, T, and U). In additional experiments with two other residue pairs, 411–415 in mGluR1 (equivalent positions for mGluR4 are 407–411) and 553–592 in mGluR1 (equivalent positions for mGluR4 are 548–587), no epistatic interactions were observed (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7 and Table S3). Residue pair 411–415 is in contact, but no epistatic interaction; mutation on either 548 or 587 abolishes surface expression in mGluR4, which made it impossible to quantify efficacy or to measure epistasis, whereas mutations at equivalent positions in mGluR1 were benign.

We next analyzed functional connectivity between two or more residue positions in terms of mutational epistasis, which measures mutational effects contingent on the presence of another mutation (45, 46, 47). To quantify epistasis between two residue positions, we compared changes in the negative logarithm of the EC50 (pEC50) conferred by one mutation with and without the presence of the other mutation. For example, given mutation A at position a and mutation B at position b, an epistatic interaction between positions a and b is defined when the change in pEC50 between WT and A depends on the state of position b. This can be mathematically presented as (45): . In a statistical test of ANOVA contrast, epistasis was observed between residues 180 and 181, and between 180 + 181 and 191 in mGluR4 in response to l-Glu (Table 1 and Fig. 4, I and J). Overall, we observed that residues 180 and 181 in mGluR4 were functionally coupled, and further, these residues 180 + 181 are in epistatic interaction with residue 191, presenting functional long-range interaction. Considering these results were ligand dependent, and not observed in mGluR1, the functional relatedness between highly covaried residue pairs might be dependent on the specific mGluR subfamily and ligand. The assays here assess a limited range of mGluR properties important for survival during evolution, so real functional interactions among coupled residues may be missed.

Table 1.

Epistasis of residue pairs between 186 (180), 187 (181), and 197 (191)

| A | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recaptor | Ligand | WT pEC50 |

Mutant pEC50 |

|

||||||

| 186 (180) |

187 (181) |

186 + 187 (180 + 181) |

||||||||

| W(ab) | SD | W(Ab) | SD | W(aB) | SD | W(AB) | SD | |||

| GRM1 | l-Glu | 5.977 | 0.140 | 5.375 | 0.195 | 5.493 | 0.153 | 4.944 | 0.013 | 0.18 |

| GRM4 | l-Glu | 5.640 | 0.184 | 5.343 | 0.346 | 4.839 | 0.268 | 4.880 | 0.167 | 0.010 |

| GRM4 | l-SOP | 6.409 | 0.231 | 6.796 | 0.092 | 5.726 | 0.059 | 6.046 | 0.154 | 0.260 |

| B | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor | Ligand | WT pEC50 |

Mutant pEC50 |

|

||||||

| 197 (191) |

186 + 187 (180 + 181) |

186 + 187 + 197 (180 + 181 + 191) |

||||||||

| W(ab) | SD | W(Ab) | SD | W(aB) | SD | W(AB) | SD | |||

| mGluR1 | l-Glu | 5.977 | 0.140 | 5.542 | 0.092 | 4.944 | 0.013 | 4.423 | 0.195 | 0.485 |

| mGluR4 | l-Glu | 5.640 | 0.184 | 5.305 | 0.188 | 4.880 | 0.167 | 4.636 | 0.136 | 0.018 |

| mGluR4 | l-SOP | 6.409 | 0.231 | 5.915 | 0.174 | 6.046 | 0.154 | 5.650 | 0.058 | 0.279 |

The epistasis between residue pairs was examined based on changes in the negative logarithm of the EC50 (pEC50), which is annotated as W, depending on the presence of a mutation at positions a and b. For instance, W(ab) indicates the average pEC50 measured on WT replicates. Capital letters, A or B, represent mutations at position a or b, respectively. Epistasis is defined when ΔW(ab->Ab) ≠ ΔW(aB->AB) are statistically significant in ANOVA contrast. Epistasis is examined (A) between 186 and 187 and (B) between 186/187 and 197. Residue numbering is based on mGluR1, and the corresponding positions on mGluR4 are shown in parenthesis, and statistical significance at a p-value less than 0.05 is highlighted in bold.

Discussion

Amino acid substitution patterns in homologous proteins provide a record of past molecular adaptations that maintained fitness over changing evolutionary contexts. Our data revealed that top ranked rvET residues were found at functionally important sites of mGluRs including the ligand-binding pockets and the dimer interface region. This confirms that top rvET positions are likely involved in primary function of the protein (Fig. 2, A–D), consistent with past experiments with rvET including class A GPCR studies (18, 48, 49). Comparing mGluRs to three class A GPCRs, amino acids on TM6 of mGluRs are notably more highly ranked across the vertebrate mGluR subfamily (Fig. 3). This result suggests consistent and important functional pressures in TM6 of mGluRs across species. Previous studies on structural architectures of human GPCRs reveal that a movement of TM6 is critical for GPCR activation for both mGluRs (class C GPCR) and class A GPCRs, despite different activation mechanisms between classes (50, 51). In class A GPCRs, a salt bridge, known as the ionic lock, between D3.50 and E6.30 plays a critical role in stabilizing the inactive conformation. Although positions and amino acids are mismatched, a salt bridge is also observed in mGluRs between K3.50 and E6.35, the disruption of which led to constitutive activity (51). On the other hand, unlike class A GPCRs, activation does not induce major residue contact changes in the TM helices of mGluRs, and the rotation and movement of TM6 in mGluRs appears limited (13 and 2.8 Å) compared with class A GPCRs (38 and 7–13 Å) (50). In addition, mGluR activation is mainly driven by relative changes in distance between TM helices in a dimer conformation, and changes in the TM6–TM6 intersubunit interface is considered to be a hallmark of activation (9, 15, 50). These studies allow us to postulate that evolutionary pressure was exerted differently in class C as compared with class A because of their mechanistic differences, with mGluR TM segments having to respond to ligand binding in the ligand-binding domain of VFT by nearly rigid body reorientations of their TM domains as opposed to more direct interactions inducing changing relative positions and lengths of individual TM helices in class A GPCRs. Our data show about 90% of residues on TM6 of mGluRs are distinctively highly conserved over evolution (SI Appendix and Fig. S2), suggesting that the entire TM6 itself is central to triggering receptor activation.

Dimerization is an important feature of mGluRs. It is increasingly linked to the pharmacological properties of homodimeric and heterodimeric mGluRs (8, 52, 53), but its molecular determinants remain to be uncovered. For both homodimers and heterodimers, the mGluR subfamily members share common dimer interfaces in apo and active states (15), and the dimerization is mediated by strong interactions between residues in LB1 compared with LB2 (14). Indeed, at a low density of receptor expression, alanine substitutions at three residue positions located at LB1 (110, 161, and 165, where residue numbering is based on mGluR5) caused significant loss of dimerization, whereas alanine substitutions at the two interface residue positions, 247 and 225, in LB2 contributed little to dimerization (14). Among the sets of residue pairs located at the dimer interface (SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5), we observed the CovET scores from residue pairs with either 110, 161, or 165 (LB1) were relatively highly ranked compared with residue pairs with either 225 or 247 (LB2) (Mann–Whitney test p value 0.0012) (SI Appendix and Table S5). Consistent with this, the interface residues on LB1 maintaining their contact from apo to active states are highly scored by rvET compared with those at LB2, which contact only in the active state (Fig 2, SI Appendix and Fig. S1). Overall, our data provide the list of residue pairs that may play a role in determining propensities for homodimerization or heterodimerization between mGluR subfamilies.

Advancements in machine learning methods have profoundly increased the accuracy of protein structure prediction from one-dimensional sequence information (54, 55, 56, 57). In part, these methods take advantage of pairwise residue covariation information to guide model building (58, 59, 60, 61). In comparison with some of the widely used open-source covariation algorithms, including SCA (62, 63, 64), DCA (65, 66, 67), EVfold (68, 69), and MIp (70, 71), CovET improved contact residue prediction within the mGluR structure and at its dimer interfaces. Top CovET predictions were also more clustered in the structure (Fig. 3, SI Appendix and Fig. S3). This gain in predictive power may open possibility of more accurate protein structure prediction using CovET as a deep learning training feature.

While a large proportion of highly ranked CovET residue pairs presents their correlation with structural proximity, our data also suggest that some distant in sequence, but highly covaried residue pairs were related in their functionality as measured by epistasis (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Epistasis underlies protein evolution, providing evolutionary relevance between and within proteins (72). However, complex mechanism of epistasis makes it difficult to identify (73) and brings different responses between species (74) or even between strains in same species (75). Those selective responses in epistasis led us to speculate that 173–174–184 pairwise epistasis interactions exhibit functional coupling, but genetic variances driven over paralog make them less interdependent. Although more studies may be required to reach a conclusion, our preliminary observations suggest that residue covariations carry out information on functional coupling between residues, and this present a critical step toward understanding allosteric pathways in mGluRs.

In addition to our tested set of residue pairs, 173–174–184, we observed highly covaried residue pairs with amino acid substitution patterns that distinguish group I mGluRs from group II and III mGluRs. Those pairs constitute 5% of the top 1% of highly covaried residue pairs (595/12,842) and involve 35 residues (SI Appendix and Fig. S8). Group I mGluRs increase neuronal excitability via coupling to Gaq/11, whereas group II and II mGluRs suppress it via Gai/o. Considering differential roles of group I mGluRs from group II and III, these sets of pairs are candidates for future studies of the molecular basis in mGluR subfamilies.

In summary, we showed an integrated approach that combined the evolutionary profiling of single and pairwise amino acid variations to identify components of function and structure in vertebrate mGluRs. rvET measured individual residues, and CovET measured coupled pairs of residues. Furthermore, our data presented that the biological interpretations of residue covariation by CovET were not only limited within a single polypeptide chain but also predicted well intersubunit contact in dimerization. In the future, such improvement may shed further light on protein–protein interactions and protein multimerization.

Experimental procedures

mGluR sequence alignment

mGluR sequences were retrieved from National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and aligned using the MUSCLE alignment tool (76). The sequences annotated as either LOW-QUALITY PROTEIN, hypothetical, or partial based on National Center for Biotechnology Information standard were excluded in this analysis. mGluR sequences from vertebrates were induced in this study to assess amino acid variations occurring in paralogs over evolution. The phylogenetic tree was generated based on sequence identity and visualized using the iTOL v6 online tool (77). Sequence identities between orthologs were higher than 60%, whereas mGluRs in different subfamilies were in the range of 30 to 60%.

Scoring single and pairwise residue importance

All scoring algorithms, both single and pairwise residue computations, used the same mGluR MSA as input. Individual residue importance was quantified by rvET (31). The raw rvET rank, ρ, at a given position i, is computed by summing the Shannon entropy (40) over every subsequent subalignment of g, defined by the phylogenetic tree (41, 42) (Fig. 2A). Then, we converted the raw value of rvET ρ, into rankings in percentiles of 0 to 100, with rvET rank of 100 representing the greatest penalty and the least inferred functional importance.

For computing pairwise residue importance, CovET, DCA, EVfold, EVcoupling, MI, MIP, SCA, and DI were applied. To make them comparable and on the same scale, raw scores were converted in rank percentile of 0 to 100, where 0 represented the most highly covaried residue pairs in all covariation algorithms. The CovET code is available at https://github.com/LichtargeLab/Covariation-ET. CovET follows the same framework as ET, meaning that it penalizes nonconcerted amino acid variations on a given residue pair i and j, iteratively through the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4A). For other open source covariation algorithms were computed in their default setting. DCA (33) was computed using the GaussDCA.jl package in Julia (https://github.com/carlobaldassi/GaussDCA.jl). EVfold was computed by FreeContact package (78) written in C++ (https://rostlab.org/owiki/index.php/FreeContact). EVcoupling was computed by code available at https://github.com/debbiemarkslab/EVcouplings. MI MIp SCA and DI are computed by protein dynamics and sequence analysis (ProDy) package in python (79) (http://prody.csb.pitt.edu). Covaried residues were visualized in a network graph using the Cytoscape, version 3.8.2 (80).

Measurement of residue–residue distance

Distance between two residues was computed from the information in PDB files. The x, y, and z coordinates of each atom in PDB files were read by Biopython.PDB package in python. An atomic distance, d, in a pair of residues i and residue j was computed based on , where x, y, z coordinates of a corresponding atom respectively, and took the minimum among all possible combinations of atoms between two residues. To capture any residue contacts in different conformational states of the mGluR subfamily, the minimum distances across 38 protein structures (Table S2) were taken.

SCW z-score calculation

SCW z-score (43) was implemented to measure the degree of structural clustering in the selected sets of residues. Weight, w, is computed in association of selected residues i and j and their distance, adjacency matrix A:

S represents the selected residue set, where the residue is in the selected set, it is assigned value 1, otherwise 0. Adjacency matrix A is defined by:

where is the minimum atomic distance between residue i and j. Statistical significance is represented as an z-score with a randomized expected average of , annotated as <> and is standard deviation , which is:

(43) describes more details.

Epistasis analysis

To examine functional dependency between a pair of residues, we applied previously defined epistasis model (45), which is:

where represents magnitude changes at residue position a and b from the existing state of mutations, which are annotated as capital letter, A or B. We assessed statistical significance of magnitude changes of pEC50 using ANOVA contrast in the R package.

Cell lines and growth conditions

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were obtained from Michael Zhu (University of Texas) and authenticated at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Cytogenetics and Cell Authentication Core. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

DNA constructs

Signal sequence cleavage sites for human mGluR1 and mGluR4 were predicted using SignalP-5.0 (81), and receptors were cloned into pcDNA3.1 with a Myc tag inserted following the endogenous signal sequence (amino acids 1–18 for mGluR1 and 1–32 for mGluR4) using overlap extension PCR and standard cloning methods, generating pcDNA3.1-ss-Myc-mGluR1 and pcDNA3.1-ss-Myc-mGluR4. Addgene plasmids #66387 and #66389 (gifts from Bryan Roth) (82) were used as PCR templates for human mGluR1 and mGluR4 receptor sequences, respectively. Mutations were introduced in pcDNA3.1-ss-Myc-mGluR1 and pcDNA3.1-ss-Myc-mGluR4 by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quickchange method. Chimeric Gαqo, which consists of mouse Gαq with the five C-terminal residues replaced by those of Gαo, and a hemagglutinin tag replacing residues 125 to 130 (44), was obtained from Bruce Conklin (University of California) and cloned into pcDNA3.1.

Ca2+ mobilization assay

HEK293 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in BME (Gibco) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific), and ∼45,000 to ∼60,000 cells/well were seeded in black clear-bottom poly-d-lysine–coated 96-well plates (Corning BioCoat). The next day, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For mGluR4, wells were cotransfected with 50 ng (for l-Glu) or 100 ng (for l-SOP) pcDNA3.1-ss-Myc-mGluR4 and 150 ng pcDNA3.1-Gαqo. For mGluR1, wells were transfected with 1, 50, or 100 ng pcDNA3.1-ss-Myc-mGluR1, as indicated, and no G-protein. Approximately 38 to 42 h after transfection, cells were washed with KRH (120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.8 g/l glucose, pH 7.4, supplemented with 1 mM probenecid), loaded with 2.7 μM Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen) in KRH with 0.01% Pluronic F-127 (Biotium) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, then washed once with KRH. About 120 μl of KRH were added to each well, and plates were prewarmed at 37 °C for 10 min. l-Glu (Sigma) and l-SOP (EMD Millipore) were prepared in KRH and prewarmed at 37 °C. Assays were performed in a Flex Station 3 plate reader (Molecular Devices) set at 37 °C. Fluorescence measurements (excitation/emission 488/520) were acquired every ∼1.6 s; 40 μl of 4× drug were added after 20 s. Assays were performed with three technical replicates of each condition, on at least three different days, except that for mGluR1 mutants with l-SOP, only two technical replicates were included each day. Data analysis was performed as described (48). Raw data from each well were baseline corrected by subtracting the average of the first 12 points (∼19 s), then the maximum response between ∼20 and 60 s was determined, using a custom script in Mathematica, version 12 (Wolfram). Maximum responses were fit with sigmoidal dose–response curves using Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc). Wells with vehicle only were assigned a drug concentration of 9 to 10 for curve fitting. Efficacy was calculated as the difference between the top and bottom plateaus of the curve fit, normalized to the WT control from the same plate. For proteins with no response to a ligand, and therefore no dose–response curve, efficacy was calculated as the maximum of averaged replicates between ∼20 and 60 s, subtracted by the vehicle-only condition, and normalized to WT.

Cell ELISA

HEK293 cells were seeded and transfected as aforementioned, in either black or white poly-d-lysine–coated 96-well plates. Approximately 38 to 42 h after transfection, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, washed three times in PBS, and blocked in PBSA (PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin) for 15 min. Cells were labeled with Myc 9E10 antibody (purified from hybridoma supernatant as described previously (83)), diluted to 3 μg/ml in PBSA for 1 h, washed twice in PBS, then labeled with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antimouse (Jackson) diluted 1:1000 in PBSA for 30 min, and washed three times in PBS. About 50 μl ECL Pico substrate (Pierce) was added to each well, and luminescence was read immediately (all wavelengths) in the Flex Station. Assays were performed with five to six technical replicates for each mutant, with WT and empty vector controls on the same plate. Mean values were subtracted by the mean empty vector value, then normalized to the mean WT value; negative values were set at zero.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HEK293 cells growing on poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips in 24-well plates were transfected with 0.6 μg DNA. Approximately 42 h after transfection, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, washed three times in PBS, and blocked in either PBSA (nonpermeabilizing) or PBSAT (permeabilizing; PBSA with 0.1% Triton X-100) for 15 min. Cells were labeled with Myc 9E10 antibody diluted to 3 μg/ml in either PBSA or PBSAT for 1 h, washed three times in PBS, then labeled with Alexa-555-conjugated antimouse (Invitrogen) diluted 1:1000 in either PBSA or PBSAT for 30 min, washed three times in PBS, and then mounted with Prolong Diamond (Invitrogen). Four images were acquired from each sample with a Zeiss LSM-710 confocal microscope and 63× oil immersion objective. Values were subtracted by the mean empty vector valu and then normalized to the mean WT value. To provide an estimate of the cell confluency in the imaged fields, an image of background fluorescence in the green channel (488 nm laser) was acquired; gain and contrast were turned up such that cells were visible.

Data availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. Our code is publicly available at GitHub (https://github.com/LichtargeLab/Covariation-ET) or website (http://lichtargelab.org).

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos.: AG068214-01, AG061105, GM066099, and AG074009, GM097207, EY031949) and Welch Foundation (Q0035).

Author contributions

E. H. conceptualization; E. H. methodology; E. H. and M. A. A. validation; E. H. and M. A. A. formal analysis; E. H., M. A. A., T. G. W., and O. L. writing–review & editing; T. G. W. and O. L. supervision; T. G. W. and O. L. project administration.

Funding and additional information

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Henrik Dohlman

Supporting information

References

- 1.Niswender C.M., Conn P.J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson K., Conn P., Niswender C. Glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets for Parkinsons disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2009;8:475–491. doi: 10.2174/187152709789824606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira V., Goudet C. Emerging trends in pain modulation by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:464. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yohn S.E., Galbraith J., Calipari E.S., Conn P.J. Shared behavioral and neurocircuitry disruptions in drug addiction, obesity, and binge eating disorder: focus on group I mGluRs in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019;10:2125–2143. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dogra S., Conn P.J. Targeting metabotropic glutamate receptors for the treatment of depression and other stress-related disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2021;196:108687. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maksymetz J., Moran S.P., Conn P.J. Targeting metabotropic glutamate receptors for novel treatments of schizophrenia. Mol. Brain. 2017;10:15. doi: 10.1186/s13041-017-0293-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stansley B.J., Conn P.J. The therapeutic potential of metabotropic glutamate receptor modulation for schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018;38:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullock T.W., Kammermeier P.J. The evidence for and consequences of metabotropic glutamate receptor heterodimerization. Neuropharmacology. 2021;199 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehl A., Hu H., Feng D., Sun B., Zhang Y., Robertson M.J., et al. Structural insights into the activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 2019;566:79–84. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0881-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J., Munguba H., Gutzeit V.A., Singh D.R., Kristt M., Dittman J.S., Levitz J. Defining the homo- and heterodimerization propensities of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Cell Rep. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredriksson R., Lagerström M.C., Lundin L.-G., Schiöth H.B. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:1256–1272. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Civelli O., Reinscheid R.K., Zhang Y., Wang Z., Fredriksson R., Schiöth H.B. G protein–coupled receptor deorphanizations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013;53:127–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romano C., Yang W.-L., O'Malley K.L. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a disulfide-linked dimer. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:28612–28616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitz J., Habrian C., Bharill S., Fu Z., Vafabakhsh R., Isacoff E.Y., et al. Mechanism of assembly and cooperativity of homomeric and heteromeric metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2016;92:143–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du J., Wang D., Fan H., Xu C., Tai L., Lin S., et al. Structures of human mGlu2 and mGlu7 homo- and heterodimers. Nature. 2021;594:589–593. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunishima N., Shimada Y., Tsuji Y., Sato T., Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., et al. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 2000;407:971–977. doi: 10.1038/35039564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kniazeff J., Prézeau L., Rondard P., Pin J.-P., Goudet C. Dimers and beyond: the functional puzzles of class C GPCRs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;130:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madabushi S., Gross A.K., Philippi A., Meng E.C., Wensel T.G., Lichtarge O. Evolutionary trace of G protein-coupled receptors reveals clusters of residues that determine global and class-specific functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8126–8132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihalek I., Res I., Lichtarge O. Evolutionary and structural feedback on selection of sequences for comparative analysis of proteins. Proteins. 2006;63:87–99. doi: 10.1002/prot.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simkovic F., Ovchinnikov S., Baker D., Rigden D.J. Applications of contact predictions to structural biology. IUCrJ. 2017;4:291–300. doi: 10.1107/S2052252517005115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pani A.M., Mullarkey E.E., Aronowicz J., Assimacopoulos S., Grove E.A., Lowe C.J. Ancient deuterostome origins of vertebrate brain signalling centres. Nature. 2012;483:289–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogdanik L., Mohrmann R., Ramaekers A., Bockaert J., Grau Y., Broadie K., et al. The Drosophila metabotropic glutamate receptor DmGluRA regulates activity-dependent synaptic facilitation and fine synaptic morphology. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9105–9116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2724-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kucharski R., Mitri C., Grau Y., Maleszka R. Characterization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in the honeybee (Apis mellifera): implications for memory formation. Invert. Neurosci. 2007;7:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s10158-007-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krenz W.D., Nguyen D., Pérez-Acevedo N.L., Selverston A.I. Group I, II, and III mGluR compounds affect rhythm generation in the gastric circuit of the Crustacean stomatogastric ganglion. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1188–1201. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pin J.-P., Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cochilla A.J., Alford S. Metabotropic glutamate receptor–mediated control of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mølck C., Harpsøe K., Gloriam D.E., Mathiesen J.M., Nielsen S.M., Bräuner-Osborne H. mGluR5: exploration of orthosteric and allosteric ligand binding pockets and their applications to drug discovery. Neurochem. Res. 2014;39:1862–1875. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arce C., Del Campo A.B., Figueroa S., López E., Aránguez I., Oset-Gasque M.J., et al. Expression and functional properties of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in bovine chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;75:182–193. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comas V., Borde M. Glutamatergic control of a pattern-generating central nucleus in a gymnotiform fish. J. Neurophysiol. 2021;125:2339–2355. doi: 10.1152/jn.00584.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nistri A., Ostroumov K., Sharifullina E., Taccola G. Tuning and playing a motor rhythm: how metabotropic glutamate receptors orchestrate generation of motor patterns in the mammalian central nervous system. J. Physiol. 2006;572:323–334. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mihalek I., Res I., Lichtarge O. A family of evolution–entropy hybrid methods for ranking protein residues by importance. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;336:1265–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halabi N., Rivoire O., Leibler S., Ranganathan R. Protein sectors: evolutionary units of three-dimensional structure. Cell. 2009;138:774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baldassi C., Zamparo M., Feinauer C., Procaccini A., Zecchina R., Weigt M., et al. Fast and accurate multivariate Gaussian modeling of protein families: predicting residue contacts and protein-interaction partners. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marks D.S., Colwell L.J., Sheridan R., Hopf T.A., Pagnani A., Zecchina R., et al. Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hopf T.A., Green A.G., Schubert B., Mersmann S., Schärfe C.P.I., Ingraham J.B., et al. The EVcouplings Python framework for coevolutionary sequence analysis. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1582–1584. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunn S.D., Wahl L.M., Gloor G.B. Mutual information without the influence of phylogeny or entropy dramatically improves residue contact prediction. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:333–340. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weigt M., White R.A., Szurmant H., Hoch J.A., Hwa T. Identification of direct residue contacts in protein–protein interaction by message passing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:67–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805923106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pin J.-P., Galvez T., Prézeau L. Evolution, structure, and activation mechanism of family 3/C G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;98:325–354. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ballesteros J.A., Weinstein H. [19] Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in g protein-coupled receptors. Sealfon S.C., editor. Met. Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shenkin P.S., Erman B., Mastrandrea L.D. Information-theoretical entropy as a measure of sequence variability. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 1991;11:297–313. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lichtarge O., Bourne H.R., Cohen F.E. An evolutionary trace method defines binding surfaces common to protein families. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;257:342–358. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins A., Erdin S., Lua R., Lichtarge O. Evolutionary trace for prediction and redesign of protein functional sites. Met. Mol. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-465-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mihalek I., Res I., Yao H., Lichtarge O. Combining inference from evolution and geometric probability in protein structure evaluation. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:263–279. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conklin B.R., Farfel Z., Lustig K.D., Julius D., Bourne H.R. Substitution of three amino acids switches receptor specificity of Gq alpha to that of Gi alpha. Nature. 1993;363:274–276. doi: 10.1038/363274a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poelwijk F.J., Tănase-Nicola S., Kiviet D.J., Tans S.J. Reciprocal sign epistasis is a necessary condition for multi-peaked fitness landscapes. J. Theor. Biol. 2011;272:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lunzer M., Miller S.P., Felsheim R., Dean A.M. The biochemical architecture of an ancient adaptive landscape. Science. 2005;310:499–501. doi: 10.1126/science.1115649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinreich D.M., Knies J.L. Fisher’s geometric model of adaptation meets the functional synthesis: data on pairwise epistasis for fitness yields insights into the shape and size of phenotype space. Evolution. 2013;67:2957–2972. doi: 10.1111/evo.12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huh E., Gallion J., Agosto M.A., Wright S.J., Wensel T.G., Lichtarge O. Recurrent high-impact mutations at cognate structural positions in class A G protein-coupled receptors expressed in tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2113373118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez G.J., Yao R., Lichtarge O., Wensel T.G. Evolution-guided discovery and recoding of allosteric pathway specificity determinants in psychoactive bioamine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7787–7792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914877107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hauser A.S., Kooistra A.J., Munk C., Heydenreich F.M., Veprintsev D.B., Bouvier M., et al. GPCR activation mechanisms across classes and macro/microscales. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021;28:879–888. doi: 10.1038/s41594-021-00674-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doré A.S., Okrasa K., Patel J.C., Serrano-Vega M., Bennett K., Cooke R.M., et al. Structure of class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 transmembrane domain. Nature. 2014;511:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nature13396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno Delgado D., Møller T.C., Ster J., Giraldo J., Maurel D., Rovira X., et al. Pharmacological evidence for a metabotropic glutamate receptor heterodimer in neuronal cells. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.25233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Habrian C.H., Levitz J., Vyklicky V., Fu Z., Hoagland A., McCort-Tranchepain I., et al. Conformational pathway provides unique sensitivity to a synaptic mGluR. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5572. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13407-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao M., Zhou H., Skolnick J. DESTINI: a deep-learning approach to contact-driven protein structure prediction. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:3514. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40314-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y., Palmedo P., Ye Q., Berger B., Peng J. Enhancing evolutionary couplings with deep convolutional neural networks. Cell Syst. 2018;6:65–74.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pakhrin S.C., Shrestha B., Adhikari B., Kc D.B. Deep learning-based advances in protein structure prediction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:5553. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen C., Wu T., Guo Z., Cheng J. Combination of deep neural network with attention mechanism enhances the explainability of protein contact prediction. Proteins. 2021;89:697–707. doi: 10.1002/prot.26052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y., Hu J., Zhang C., Yu D.-J., Zhang Y. ResPRE: High-accuracy protein contact prediction by coupling precision matrix with deep residual neural networks. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4647–4655. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu J. Distance-based protein folding powered by deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:16856–16865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821309116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmiedel J.M., Lehner B. Determining protein structures using deep mutagenesis. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:1177–1186. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0431-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teşileanu T., Colwell L.J., Leibler S. Protein sectors: statistical coupling analysis versus conservation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mihaljević L., Urban S. Decoding the functional evolution of an intramembrane protease superfamily by statistical coupling analysis. Structure. 2020;28:1329–1336.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seo M.J., Heo J., Kim K., Chung K.Y., Yu W. Coevolution underlies GPCR-G protein selectivity and functionality. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:7858. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morcos F., Pagnani A., Lunt B., Bertolino A., Marks D.S., Sander C., et al. Direct-coupling analysis of residue coevolution captures native contacts across many protein families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 2011;108:E1293–E1301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111471108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng R.R., Morcos F., Levine H., Onuchic J.N. Toward rationally redesigning bacterial two-component signaling systems using coevolutionary information. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E563–E571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323734111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schug A., Weigt M., Onuchic J.N., Hwa T., Szurmant H. High-resolution protein complexes from integrating genomic information with molecular simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:22124–22129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hopf T.A., Colwell L.J., Sheridan R., Rost B., Sander C., Marks D.S. Three-dimensional structures of membrane proteins from genomic sequencing. Cell. 2012;149:1607–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reza Md.S., Zhang H., Hossain M.T., Jin L., Feng S., Wei Y. Comtop: protein residue–residue contact prediction through mixed integer linear optimization. Membranes (Basel) 2021;11:503. doi: 10.3390/membranes11070503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng N., Mao Y., Shi Y., Tao S. Coevolution in RNA molecules driven by selective constraints: evidence from 5S rRNA. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bay D.C., Hafez M., Young M.J., Court D.A. Phylogenetic and coevolutionary analysis of the β-barrel protein family comprised of mitochondrial porin (VDAC) and Tom40. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:1502–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Breen M.S., Kemena C., Vlasov P.K., Notredame C., Kondrashov F.A. Epistasis as the primary factor in molecular evolution. Nature. 2012;490:535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature11510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lehner B. Molecular mechanisms of epistasis within and between genes. Trends Genet. 2011;27:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kondrashov A.S., Sunyaev S., Kondrashov F.A. Dobzhansky–Muller incompatibilities in protein evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:14878–14883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232565499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dowell R.D., Ryan O., Jansen A., Cheung D., Agarwala S., Danford T., et al. Genotype to phenotype: a complex problem. Science. 2010;328:469. doi: 10.1126/science.1189015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Edgar R.C. Muscle: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Letunic I., Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucl. Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaján L., Hopf T.A., Kalaš M., Marks D.S., Rost B. FreeContact: fast and free software for protein contact prediction from residue co-evolution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bakan A., Dutta A., Mao W., Liu Y., Chennubhotla C., Lezon T.R., et al. Evol and ProDy for bridging protein sequence evolution and structural dynamics. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2681–2683. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Almagro Armenteros J.J., Tsirigos K.D., Sønderby C.K., Petersen T.N., Winther O., Brunak S., et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kroeze W.K., Sassano M.F., Huang X.P., Lansu K., McCorvy J.D., Giguère P.M., et al. PRESTO-Tango as an open-source resource for interrogation of the druggable human GPCRome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:362–369. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Agosto M.A., Adeosun A.A.R., Kumar N., Wensel T.G. The mGluR6 ligand-binding domain, but not the C-terminal domain, is required for synaptic localization in retinal ON-bipolar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin S., Han S., Cai X., Tan Q., Zhou K., Wang D., et al. Structures of Gi-bound metabotropic glutamate receptors mGlu2 and mGlu4. Nature. 2021;594:583–588. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. Our code is publicly available at GitHub (https://github.com/LichtargeLab/Covariation-ET) or website (http://lichtargelab.org).