Abstract

Background

As defined by the WHO, the term post-COVID syndrome (PCS) embraces a group of symptoms that can occur following the acute phase of a SARS-CoV-2 infection and as a consequence thereof. PCS is found mainly in adults, less frequently in children and adolescents. It can develop both in patients who initially had only mild symptoms or none at all and in those who had a severe course of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

The data presented here were derived from a systematic literature review.

Results

PCS occurs in up to 15% of unvaccinated adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. The prevalence has decreased in the most recent phase of the pandemic and is lower after vaccination. The pathogenesis of PCS has not yet been fully elucidated. Virus-triggered inflammation, autoimmunity, endothelial damage (to blood vessels), and persistence of virus are thought to be causative. Owing to the broad viral tropism, different organs are involved and the symptoms vary. To date, there are hardly any evidence-based recommendations for definitive diagnosis of PCS or its treatment.

Conclusion

The gaps in our knowledge mean that better documentation of the prevalence of PCS is necessary to compile the data on which early detection, diagnosis, and treatment can be based. To ensure the best possible care of patients with PCS, regional PCS centers and networks embracing existing structures from all healthcare system sectors and providers should be set up and structured diagnosis and treatment algorithms should be established. Given the sometimes serious consequences of PCS for those affected, it seems advisable to keep the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections low by protective measures tailored to the prevailing pandemic situation.

While the vast majority of patients recover from acute infection with SARS-CoV-2 without discernible sequelae, a proportion of patients experience long-term effects that can last for months (1– 4, e1). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that following the acute phase of infection, 10–20% of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals complain of persisting or new-onset symptoms in the longer course, which is referred to as post-COVID syndrome (PCS) (e2). PCS affects patients that were asymptomatic or had only mild acute symptoms and who self-isolated at home as well as patients with moderate or severe disease that required hospitalization or care on an intensive care unit. The lack of control group in the numerous studies carries the risk of overestimating the prevalence of PCS (5, e45), since comparable symptoms potentially occurring in a control group are not included in the calculation. In principle, long-term sequelae can develop independently of severity and with or without demonstrable organ pathology. In the case of acute disease requiring intensive care, it may be difficult to differentiate PCS from post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), since the latter can be associated with similar clinical symptoms.

cme plus

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. The deadline for submission is 26.01.2024.

Methods

For the statement (6) on which this review article is based, the literature for the publishing period 2020–2022 was collated and reviewed in a structured, methodological review process (for a detailed description of the literature search, see eMethods, eTables 1– 4). Searches were carried out between 19 July 2022 and 22 July 2022. The recommendations are based on these studies.

Definition

The terminology and definition of long-COVID and PCS is not standardized. The term “long-COVID” emerged as a hashtag on social media during the early phase of the pandemic and is still used there by the majority of people (7, e3). Since the term PCS has become established in the specialist literature, including the S1 guideline of the the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF) (8), it will be used in the following. The WHO has developed the following definition of PCS by a Delphi consensus (9): The symptoms must still be present more than 12 weeks after acute infection and persist for at least 2 months. There can be no other etiological explanation. The clinical course may be persistent, relapsing, or fluctuating (ICD-10 U09.9).

Protracted symptoms in the second and third month following SARS-CoV-2 infection are classified as persistent symptomatic infection and delayed recovery, respectively. In such cases, the ICD-10 code U08.9 may indicate the need for healthcare in the context of COVID-19. The authors of this statement do not consider the exacerbation or aggravation of preexisting diseases as PCS in the narrower sense.

Causes

Although the pathogenesis of PCS is not yet fully understood, there is very good evidence to support diverse general as well as organ-specific causes, which will be presented below (10, 11, e4).

The many and diverse organ manifestations of SARS-CoV-2-related disorders are due, in part, to the broad tropism of the virus, which is defined by the distribution of the viral receptor. Cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 begins with its binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor (12). The ACE2 receptor is abundantly present in tissues in the human body. It has been demonstrated in the lungs, kidneys, small intestine, olfactory neuroepithelium, heart, testes, muscle cells, and substantia nigra in the brain (13, e5– e9). Accordingly, the number of organs in which the virus or viral components can be found is large. Infection typically begins on the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and lungs and can spread in the further course. The presence of ACE2 receptors in the vascular endothelium as well as the development of accompanying inflammatory and immunological processes provide a first possible explanation for the great diversity in the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (e9).

Endothelial dysfunction

SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause vascular inflammation (11) that leads to impaired microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction (ED) (14). A third of patients with PCS exhibit ED in endothelial dysfunction testing (EndoPAT) as well as elevated levels of the potent vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 (ET-1) 6 months following mild COVID-19 (e10). ED can also cause changes to the retina (e11) and affect reproductive health (e12), for example, through new-onset erectile dysfunction (e13).

Viral persistence

A number of studies show that residual SARS-CoV-2 can persist for more than 6 months after the acute phase of COVID-19 (11), despite the fact that viral replication can no longer be demonstrated. One study showed a persistent spike 1 (S1) protein in CD16 + monocytes of patients with PCS (e14). The gut can be a reservoir for viral persistence—a link to PCS has not been investigated (15, e15). It is possible that persistent viral components cause ongoing inflammation that could ultimately lead to PCS.

Autoimmunity

Autoantibodies (AAB) are detectable not only during acute infection but also in PCS (16). For example, AAB against type-1 interferons as well as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) that have an effect on the control of the autonomic nervous system (e16) have been detected in PCS patients (e16). Antineuronal AAB have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurological manifestations of PCS (e17). It was shown in a large collective that the detection of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), interferon-alpha AAB, and proinflammatory cytokines in the acute phase correlated with the development of gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms in the setting of PCS (e18).

Persistent inflammation

Persistent inflammation is an established pathomechanism in PCS (e19), even when SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication can no longer be detected. As long as 8 months following infection, PCS patients still show immunological abnormalities, characterized by an inflammatory cytokine signature, compared to non-infected individuals or patients infected with other viruses. In particular, persistent inflammation was observed in the lungs, heart, and central nervous system (17, e20, e21). A major aspect of persistent inflammation is the defective repair of the sequelae of inflammation (e22). In studies, this inflammatory cytokine signature has a positive predictive value of 79–82% for the development of long-term symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, or chest pain, and includes, for example, type I and type III interferons (18). PCS patients also exhibit altered activation patterns of monocytes, granulocytes, and dendritic cells (e21).

Psychosocial factors

In addition to the direct biological sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection consistent with a postviral syndrome, one must also consider psychosocial factors, which could either be, for example, the manifestation of separate mental illnesses or the result of measures taken to contain the pandemic. Not only the stressors associated with the effects of COVID-19 infection but also the measures taken against the pandemic can lead many people to develop new-onset mental illness or experience a worsening of existing mental health disorders (19). These stressors may be due to the situation arising from quarantine, loneliness, home office, home schooling, uncertainty about how the pandemic will evolve, threat to economic livelihood, or concern about relatives. This worsening is clearly linked not only to a reduction in the quality of medical care but also to unfavorable health-related behavior, for example, lower levels of physical activity, longer times spent in bed, and increased rumination. Negative effects of the pandemic and the measures for its containment have also been described for other mental illnesses, for example anxiety disorders and eating disorders, as well as for psychosocial stressors such as domestic violence and family conflicts. They result in greater utilization of mental health services (e23, e24). These associations are similar for children and adolescents.

Predisposing factors, risk factors, and protection through vaccination

The currently known risk factors for the development of PCS are summarized in the Box.

Box. Risk factors for post-COVID syndrome (2, 24, 33– 36, e41– e44).

-

Biographical factors

Caucasian population

Middle age

Female sex

-

Preexisting diseases

Bronchial asthma

Poor mental health

Diabetes mellitus

Hypertension

Obesity

-

COVID-19-specific

Multiple (> 5) acute symptoms

High acute viral load

Low baseline SARS-CoV-2 IgG

Diarrhea

Vaccination status

(From [6]: reprinted with kind permission from the German Medical Association [Bundesärztekammer])

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination appears to significantly reduce the risk of PCS (20– 22). Overall, the presence of vaccination was associated with a lower risk or lower likelihood of PCS. Two vaccine doses appear to be more effective than one (20). Figures from the United Kingdom’s COVID Surveillance Study (as of 27.05.2022) (e25) show that triple vaccination can reduce the prevalence of PCS to below 5% (23). Individual susceptibility in adults for the development of PCS appears to be independent of the severity of the acute pulmonary and systemic disease (e26, e27).

Incidence

The variety and frequency of symptoms that can develop following the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection are not always directly comparable across the various studies, given that the investigated cohorts differ in terms of size, selection process, and symptom recording. In addition, studies without control groups harbor the risk of overestimating PCS. In 10 UK longitudinal studies, the percentage of individuals presumed to have COVID-19 that reported long-term symptoms after more than 12 weeks was between 7.8 and 17% (with a total of 1.2–4.8% reporting debilitating symptoms) (24).

Assuming that approximately 5–15% of adult unvaccinated patients develop PCS, a relatively large number of individuals would be affected by PCS. With 22 million individuals having recovered from COVID-19 (as of August 2022), one can assume that statistically, the number of people with PCS in Germany would be several hundred thousand. One needs to bear in mind that this process is subject to dynamic changes that depend in particular on virus variants and the level of immunization in the population.

Symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment

Since the ACE2 receptor is expressed in many organs and COVID-19 manifests in multiple organs, PCS can also present with diverse clinical symptoms and organ manifestations (e21, e28) (table). As a general rule, the main symptoms occurring in adults can also be observed in children and adolescents, albeit far more rarely (25). The course of the pandemic thus far has shown that symptoms and organ manifestations can change depending on the prevailing SARS-CoV-2 virus variant and the vaccination status of those infected (20– 23).

Table. Organ-related disorders with a morphological substrate in PCS.

| Organ | Clinicalsymptoms | Morphological manifestation and findings | Pathophysiologicalmechanisms | |

| Imaging | Histology, immunohistology, molecular pathology | |||

| Olfactory/gustatorysystem see also “CNS and PNS” | Loss of or reduction in sense of taste and smell (dysgeusia, anosmia) | CT and MRI: diffusleyincreased signal intensity in the olfactory bulb, hyperintense foci or microhemorrhages, clumping and thinning of olfactory filia (e46) | Leukocyte infiltration of the lamina propria with apoptotic damage to taste buds, olfactory nerve fibers, and central nervous olfactory centerAutopsy: focal atrophy of the olfactory epithelium (37) | ACE2 receptors in the CNS (olfactory bulb, amygdala, hippocampus, temporal lobe, posterior cingulate cortex, brainstem) |

| Lungs, upper airways | Dyspnea, persistent cough, asthma exacerbation (38) | CT: persistent changes,e.g., ground glass opacity, interstitial thickening, peripheral reticulation, fibrosis, bronchiectasis (e1) | Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), diffuse alveolar fibrosis and scarring, organizing pneumonia (e47), endotheliitis, microhemorrhages (e48),IHC detection of ACE2 + in the lungs (especially type-II pneumocytes and alveolar macrophages) (e49) | Persistent SARS-CoV-2 RNA in lung tissue (virus reservoir) with overactivation of alveolar epithelial cells (ACE2+) and reduction in alveolar macrophages, development of chronic scarring inflammation (e21); detection of profibrotic macrophage responses (e50, e51) |

| Heart/myocardium | Atypical chest pain,sensation of pressure in the chest, tachycardia, palpitation (38, 39), lung congestion, arrhythmias, pericardial friction rub | cMRI: COVID-19-related myocardial inflammation (e51) | Endomyocardial biopsies:active lymphocytic inflammation (e51), thrombi in small and larger heart vessels (39, e48), IHC detection of ACE2 + in monocytes (e49) | Persistent viral load induced in ACE2+ myocytes and myocardial inflammationwith pro-inflammatory cells, infiltrating monocytes, neutrophils, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (e21) |

| Brain (CNS)and peripheral nervous system (PNS) see also “Olfactory/gustatory system” | Sleepiness, fatigue,brain fog, headache, impaired memory/ concentration, diverse psychiatric alterations, numbness, tremor | 18F-FDG PET-basedneuroimaging: hypometabolic CNS regions (olfactory gyrus, temporal lobe, including amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, brainstem, cerebellum) (e52) | Viral neuroinvasion,neuroimmunological response in the peripheral and central nervous system with disrupted blood–brain barrier; detection at autopsy of ACE2 in brainstem cells | Hypothesis: neurotropic SARS-CoV-2 (infects neuronal cell cultures and organoids) affects ACE2+ cells (neurons, astrocytes) and brainstem cells (e53) |

| Skeletal muscle | Muscle weakness, myalgia, arthritis in small joints (38, e54) | Diffuse inflammatory infiltration of muscles, connective tissue, and joints | see cardiac muscle | |

| Kidneys | Reduced glomerularfiltration rate, microhematuria | Thrombosis of small renal vessels, especially in glomeruli; IHC: ACE2+ in the brush border and cytoplasm of the proximal tubular cells (e49) | Persistent SARS-CoV-2 RNA in renal vessels and ACE2+ tubular epithelial cells inducing chronic cell damage | |

| Vessels | Phlebitis and thrombophlebitis | Inflammatory vessel wallinfiltration of the endothelium of small-to-large arteries and sporadically in smooth muscle cells (e51) | Persistent viral invasion ofendothelial cells with inflammation-related alternations as the basis of thrombus formation: often persistent hypercoagulability | |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Nausea, diarrhea,loss of appetite, abdominal pain (40) | Abdominal radiologicalinvestigations are not specific for COVID-19- induced symptoms | IHC detection of ACE2+enterocytes, especially in absorptive enterocytes in the ileum with signs of chronic inflammation (e21) | Viral persistence in ACE2-expressing gastrointestinal cells with subsequent chronic cell damage (e55) |

| Reproductive system | Erectile dysfunction | Endothelial damage | Endothelial cell injury (e13); pituitary–gonadal axis withreduced testosterone (e56) | |

| Islet cell apparatusof the pancreas | Diabetes | IHC detection of ACE2 inpancreatic islet cells (e57) | Viral persistence in ACE2-expressing islet cells with loss of function | |

ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; cMRI, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography;

IHC, immunohistochemistry; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PNS, peripheral nervous system; PET, positron emission tomography; US, ultrasound;

18F-FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; CNS, central nervous system

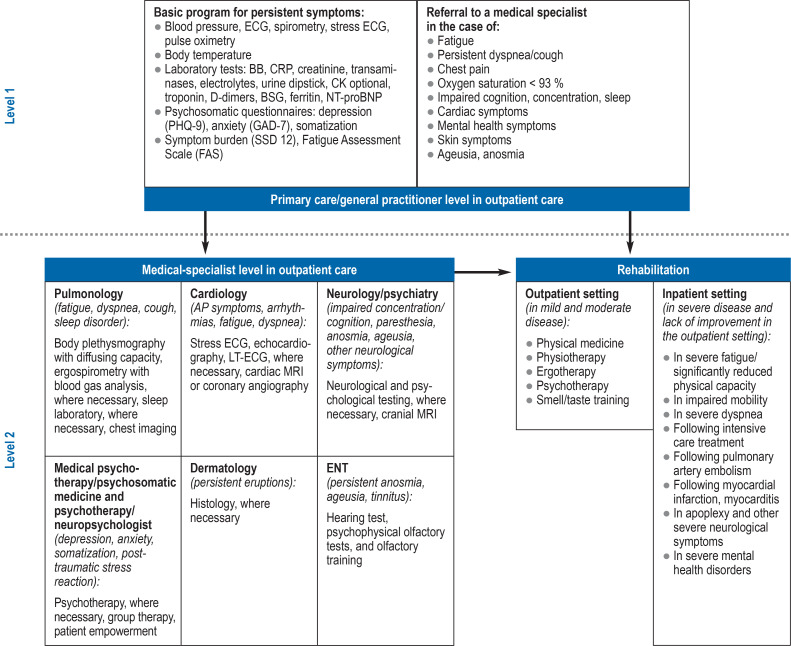

Since no specific diagnostic markers (for example, in blood) or characteristic imaging findings are known to date, the diagnosis of PCS needs to be made on the basis of clinical presentation. This can be particularly challenging in children and adolescents due to the limited self-reported patient history. A prerequisite of establishing the diagnosis of PCS is that the relevant symptoms were not already present prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection and that patients experience impairments in everyday life as well as a level of suffering, meaning that previous medical findings as well as the collaboration of the various healthcare providers take on central importance (Figure). Patients suffering from fatigue and exercise intolerance need to be assessed for myalgic encephalomeylitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) on the basis of clinical diagnostic scores. Differentiation from depression is a common differential diagnostic question due to the 1-year incidence of depression of approximately 8% in the adult population.

Figure 1.

Collaboration between the different care providers

AP, angina pectoris; BB, glycogen phosphorylase; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein;

LT-ECG, long-term electrocardiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NT-proBNT, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone;

(from [6]: reprinted with kind permission from the German Medical Association [Bundesärztekammer])

A targeted assessment of findings, paying particular attention to new-onset symptom-related limitations, and the basic laboratory work-up are of crucial importance (8), since in many cases PCS represents a diagnosis of exclusion. The S1 guideline of the AWMF provides an overview of the individual organ manifestations and the initial assessment in suspected PCS (8). It is important to accurately record the various symptoms in order to offer patients tailored treatment and rehabilitation concepts aimed at shortening the recovery phase.

There are currently no evidence-based, causal, specific treatment options. Only scant interventional studies are available, and no therapeutic concept has been sufficiently validated to date (26). Therefore, no reliable recommendations can be made for numerous procedures, such as apheresis, vitamin replacement, and other pharmacological interventions. Current treatment concepts are based on an interdisciplinary, pragmatic approach that includes physical rehabilitation measures as well as symptom-oriented treatment of the various organ disorders. There are meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies on the efficacy and effectiveness of physical procedures in PCS that support symptom-oriented physical rehabilitation measures (26– 30, e29). In the case of ME/CFS, all diagnostic and therapeutic measures need to be tailored to the often significantly limited physical capacity of individual patients. Pacing, that is to say, sparing, dosed management of the patient’s energy resources and strict avoidance of overexertion, is recommended.

Thus, it remains essential that targeted treatment approaches be identified in the future. Further studies are required on, for example, the effectiveness of vaccinations or the administration of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in PCS (e30). Initial results indicate a lasting improvement in PCS following a second vaccine dose, at least in the median follow-up period of 67 days (31).

Likewise in children and adolescents, treatment has thus far been symptom-oriented (32). In the case of interdisciplinary and, where appropriate, multimodal treatment, somatic and mental health aspects need to be taken into account, and physical capacity must be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Current structures and potential needs regarding PCS treatment and research

The sociomedical and economic impact of PCS cannot be foreseen but is likely to be immense. Since PCS is a multisystem disease, an interdisciplinary (including infectious diseases, internal medicine, neurology, psychiatry and psychotherapy, psychosomatics, pulmonology, cardiology, rheumatology, ENT, physical medicine and rehabilitation, general medicine, pain medicine, pediatrics) and intersectoral collaboration involving cooperation with general practitioners and specialists in pediatric and adolescent medicine seems imperative for the comprehensive care of these patients. Close cooperation is needed between primary care and specialist outpatient healthcare providers and centers in larger hospitals.

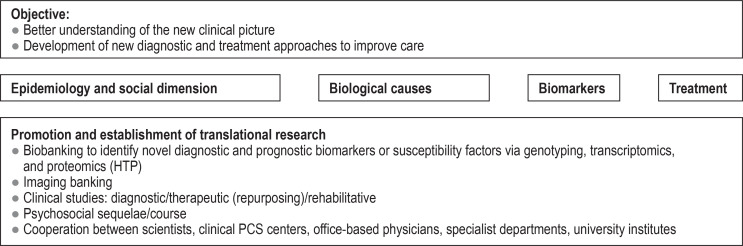

Against this backdrop, the following structures are required: For clinical care, specialized PCS centers need to be set up at maximum-care institutions (generally university hospitals), where specialists from a number of disciplines can provide comprehensive care (figure 2). Structures of this kind already exist at some university hospitals in Germany (e31– e37). These PCS centers should form regional PCS networks with local hospitals and practices or embrace existing networks in order to ensure the provision of care to the large number of primarily adult patients (e38, e39).

Figure 2.

Understanding post-COVID syndrome—dimensions of scientific analysis (from [6]: reprinted with kind permission from the

German Medical Association [Bundesärztekammer])

In addition to providing interdisciplinary care, the PCS centers should also collaborate on translational research efforts. The main focus will be to evaluate the concepts of the newly created care structures, to investigate the effects of more interdisciplinary treatment strategies on the course of the disease, and to develop diagnostic guidelines and novel treatments for PCS. Furthermore, the formation of a national PCS network that coordinates the collaboration of all important actors and is also the contact point for both science and policy is proposed.

For housebound or bedridden PCS sufferers, there is an urgent need to strengthen and expand telemedical and outreach care structures (for example, specialized outpatient palliative care [SOPC]).

In addition to providing interdisciplinary care, the PCS centers should collaborate on translational research with the aim of developing scientifically based diagnostic guidelines and novel PCS treatments as rapidly as possible.

The primary focus of this research should be a patient-oriented treatment approach (figure 2) that will advance translational concepts at an internationally competitive level and within an international network as early on as possible.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Systematic literature search

For the statement “Post-COVID-Syndrom (PCS)” (post-COVID syndrome) of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) (6), a systematic search relating to the publication period 2020–2022 was carried out for guidelines, systematic review articles, and randomized controlled studies in medical databases such as the Cochrane COVID-19 study register, for which update searches for studies on humans are performed daily to weekly in numerous specialist databases (https://community.cochrane.org/about-covid-19-study-register). Other sources, such as MEDLINE, the WHO Register, and the Guidelines International Network database were also included in the search. To complete the data, a search was additionally carried out in the Cochrane COVID-19 study register for recent observational studies published in 2022. Peer-reviewed full-text articles were taken into consideration, as were preprints (as yet non-peer-reviewed specialist articles) published in MedRxiv (www.medrxiv.org/). No restrictions were set in terms of language. Searches were carried out between 19.07.2022 and 22.07.2022.

Publications that can be classified into the following PICO framework (population/participants, intervention, comparison group/control, outcome) were included: population/participants were defined as patients following the acute phase of COVID-19. If an intervention had been evaluated, it was defined as any intervention for prevention or treatment (pharmacological or otherwise) in participants, while comparison/control was defined as patients receiving a comparison intervention (studies comparing two interventions) or no intervention. Studies were initially included irrespective of the reported endpoints, with the focus placed on patient-relevant endpoints that evaluated improvement in physical, cognitive, or mental functioning, including quality of life, or symptom relief.

Evidence-based guidelines on PCS were selected as the study design or type of publication. If there were several versions of a guideline, only the most recent version was considered. In addition, systematic review articles and meta-analyses that either investigated interventions for the prevention or treatment of PCS or assessed observational studies on PCS onset were included. Randomized controlled trials that evaluated interventions for the prevention or treatment of PCS or individual symptoms (for example, anosomia) were also included. The search was complemented by observational studies (prospective and retrospective studies) that included a minimum of 1000 participants with symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection and that were published in 2022.

Studies that did not evaluate a control group, as well as comparative studies with a control group, were included. Here, the control group could be made up of participants that had previous SARS-CoV-2 infection or contracted COVID-19 but had not experienced any long-term symptoms, or also comprise a population that had no previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 infection was demonstrated via a PCR or antigen test in the acute phase, via an antibody test, or participants were asked about their previous infection status. No attempt was made to contact study authors for primary data.

Search results were downloaded in the Endnote databases and evaluated in each case by two independent reviewers for a match with inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. If this did not lead to a consensus, a third person was called in to assess whether a publication matched criteria in order to reach a consensus (e40) (etable 1).

Systematic literature search: search history Long C for guidelines, SRs, and studies (cohort studies and RCTs)

Guideline search

Database search strategies

MEDLINE (via OVID)

# Searches

eTable 1. Guideline search.

| Media | Search 22 July 2022 |

| ECRI* | Not available at the moment |

| G-I-N* | 3 |

| New South Wales government* (Australia) | 1 |

| National Covid-19 Clinial Evidence Taskforce* (Australia) | 3 |

| CADTH* | 4 |

| WHO* | 0 |

| CDC* | 2 |

| ECDC* | 0 |

| MEDLINE | 57 |

| TRIP | 7 |

* Searched and screened: post covid, long covid, long term, post acute, sequelae, chronic covid, post intensive, inflammatory multisystem, multisystem inflammatory, PIMS, MIS; ECRI: https://www.ecri.org/about/; G-I-N, Guidelines International Network; CADTH, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; WHO, World Health Organization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ECDC, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

1) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “2019 nCoV”).ti.

2) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 2019nCoV).ti.

3) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 coronavir*).ti.

4) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 coronovir).ti.

5) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 COVID).ti.

6) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 COVID19).ti.

7) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 HCoV*).ti.

8) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “nCov 2019”).ti.

9) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “SARS CoV-2”).ti.

10) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “SARS CoV 2”).ti.

11) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 SARSCoV-2).ti.

12) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “SARSCoV-2”).ti.

13) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”).ti.

14) (post-exertional malaise or PEM or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post corona virus disease” or “post coronavirus disease” or “post intensive care syndrome” or PICs or PIMS or “PIMS-TS” or MIS or “MIS-C” or MISC or MISTIC).ti.

15) ((multisystem inflammatory or multi-system inflammatory or inflammatory multisystem or inflammatory multi-system) adj2 (syndrom* or disease*)).ti.

16) or/1–15

17) exp Practice Guideline/

18) ((practice or treatment* or consensus or clinical) adj guideline*).ab. /freq=3

19) guideline*.ti,kw,kf.

20) or/17–19

21) 16 and 20

22) limit 21 to last 2 years

TRIP

(“long COVID” or “long COVID-19” or “long COVID19” or haul*

“chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or “post-acute” or “postacute” or “post COVID” or “post COVID-19” or “post COVID19”

“long term COVID” or “long term COVID-19” or “long term COVID19”

“post-exertional malaise” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post corona virus disease” or “post coronavirus disease”

“chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or

(pacs OR sequelae* OR “late complication” OR “late complications”) AND (covid OR covid-19 OR covid19)

“post intensive care syndrome” or “persistent COVID” or “persistent COVID-19” or “persistent COVID19” or

(“post intensive care syndrome” OR “persistent covid” OR “persistent covid-19” OR “persistent covid19”) AND (covid OR covid-19 OR covid19)

“late COVID” or “late COVID-19” OR “late COVID19”

(“inflammatory multi-system syndrome” OR “inflammatory multisystem syndrome” OR “inflammatory multi-system disease” OR “inflammatory multisystem disease” OR pims OR “pims-ts” OR “multisystem inflammatory disease” OR “multi-system inflammatory disease” OR “multi-system inflammatory syndrome” OR “ multisystem inflammatory syndrome” OR mis OR “mis-c” OR misc OR mistic) AND (covid OR covid19 OR covid-19) from_date:2021

Evidence syntheses

1) Evidence Aid Coronavirus (Covid-19)

Searched and screened: post covid, long covid, long term, post acute, sequelae, chronic covid, post intensive, inflammatory multisystem, multisystem inflammatory, PIMS, MIS

2) Usher Network for COVID-19 Evidence Reviews

eTable 2. Evidence syntheses.

| Search 19 July 2022 | |

| Evidence Ai | 6 |

| Usher | 27 |

| ESP-VA | 57 |

| LOVE | 312 |

| MEDLINE | 274 |

| Total | 676 |

| Total (after deduplication) | 483 |

Searched and screened: post covid, long covid, long term, post acute, sequelae, chronic covid, post intensive, inflammatory multisystem, multisystem inflammatory, PIMS, MIS

3) U.S. Veterans’ Affairs (VA) Evidence Synthesis Program

Searched and screened: post covid, long covid, long term, post acute, sequelae, chronic covid, post intensive, inflammatory multisystem, multisystem inflammatory, PIMS, MIS

4) L*OVE

(“long COVID” or “long COVID-19” or “long COVID19” or haul* or “chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or “post-acute” or “postacute” or “post COVID” or “post COVID-19” or “post COVID19” or “long term COVID” or “long term COVID-19” or “long term COVID19” or “post-exertional malaise” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post corona virus disease” or “post coronavirus disease” or “chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or PACS or sequelae* or “late sequelae” or “post intensive care syndrome” or “persistent COVID” or “persistent COVID-19” or “persistent COVID19” or “post-infectious” or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or “late COVID” or “late COVID-19” OR “late COVID19” or “inflammatory multi-system syndrome” or “inflammatory multisystem syndrome” or “inflammatory multi-system disease” or “inflammatory multisystem disease” or PIMS or “PIMS-TS” or “multisystem inflammatory disease” or “multi-system inflammatory disease” or “multi-system inflammatory syndrome” or “multisystem inflammatory syndrome” or MIS or “MIS-C” or MISC or MISTIC)

Filtered by systematic review

2021: 198 2022: 14

5) Medline (via Ovid)

# Searches

1) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “2019 nCoV”).ti.

2) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 2019nCoV).ti.

3) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 coronavir*).ti.

4) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 coronovir).ti.

5) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 COVID).ti.

6) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 COVID19).ti.

7) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 HCoV*).ti.

8) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “nCov 2019”).ti.

9) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “SARS CoV-2”).ti.

10) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “SARS CoV 2”).ti.

11) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 SARSCoV-2).ti.

12) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “SARSCoV 2”).ti.

13) ((long or haul* or chronic or post-acute or postacute or post or long term or chronic or sequelae* or persistent* or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or late) adj4 “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”).ti.

14) (post-exertional malaise or PEM or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post corona virus disease” or “post coronavirus disease” or “post intensive care syndrome” or PICs or PIMS or “PIMS-TS” or MIS or “MIS-C” or MISC or MISTIC).ti.

15) ((multisystem inflammatory or multi-system inflammatory or inflammatory multisystem or inflammatory multi-system) adj2 (syndrom* or disease*)).ti.

16) or/1–15

17) cochrane database of systematic reviews.jn. or search*.tw. or meta analysis.pt. or medline.tw. or systematic review.tw. or systematic review.pt.

18) 16 and 17

19) limit 18 to dt=20200101–20220720

2021: 140

2022: 134

eTable 3. Randomized controlled studies.

| Database | Search 19 July 2022 |

| CCSR | 310 ref. (104 studies) |

| WHO COVID-19 DB | 428 |

| Total | 732 |

| Total (after deduplication) | 716 |

Randomized controlled trials

CCSR “long COVID” or “long COVID-19” or “long COVID19” or haul* or “chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or “post-acute” or “postacute” or “post COVID” or “post COVID-19” or “post COVID19” or “long term COVID” or “long term COVID-19” or “long term COVID19” or “post-exertional malaise” or “PEM” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post corona virus disease” or “post coronavirus disease” or “chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or PACS or sequelae* or “late sequelae” or “post intensive care syndrome” or PICs or “persistent COVID” or “persistent COVID-19” or “persistent COVID19” or “post-infectious” or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or “late COVID” or “late COVID-19” OR “late COVID19” or “multi-system syndrome” or “multisystem syndrome” or “inflammatory multisystem” or “inflammatory multi-system” or PIMS or “PIMS-TS” or “multisystem Inflammatory” or “multi-system inflammatory” or MIS or “MIS-C” or MISC or MISTIC

Study characteristics

1) Intervention assignment: randomized, quasi-randomized, unclear

2) Study design: parallel/crossover, unclear

Results available: report results

WHO COVID-19 Global literature on coronavirus disease

i:(“long COVID” OR “long COVID-19” OR “long COVID19” OR haul* OR “chronic COVID” OR “chronic COVID-19” OR “chronic COVID19” OR “post-acute” OR “postacute” OR “post COVID” OR “post COVID-19” OR “post COVID19” OR “long term COVID” OR “long term COVID-19” OR “long term COVID19” OR “post-exertional malaise” OR “PEM” OR “post-SARS-CoV-2” OR “post-SARS-CoV-2” OR “post corona virus disease” OR “post coronavirus disease” OR “chronic COVID” OR “chronic COVID-19” OR “chronic COVID19” OR pacs OR sequelae* OR “late sequelae” OR “post intensive care syndrome” OR pics OR “persistent COVID” OR “persistent COVID-19” OR “persistent COVID19” OR “post-infectious” OR “postinfectious” OR “post-infection” OR “postinfection” OR “late complication” OR “late complications” OR “late COVID” OR “late COVID-19” OR “late COVID19” OR “multi-system syndrome” OR “multisystem syndrome” OR “inflammatory multisystem” OR “inflammatory multi-system” OR pims OR “PIMS-TS” OR “multisystem Inflammatory” OR “multi-system inflammatory” OR mis OR “MIS-C” OR misc OR mistic)

AND

(random* OR placebo OR trial OR groups OR “phase 3” OR “phase3” OR p3 OR “pIII”)

Cohort studies

CCSR

eTable 4. Cohort studies.

| Search 19 July 2022 | |

| CCSR | 6330 |

“long COVID” or “long COVID-19” or “long COVID19” or haul* or “chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or “post-acute” or “postacute” or “post COVID” or “post COVID-19” or “post COVID19” or “long term COVID” or “long term COVID-19” or “long term COVID19” or “post-exertional malaise” or “PEM” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post-SARS-CoV-2” or “post corona virus disease” or “post coronavirus disease” or “chronic COVID” or “chronic COVID-19” or “chronic COVID19” or PACS or sequelae* or “late sequelae” or “post intensive care syndrome” or PICs or “persistent COVID” or “persistent COVID-19” or “persistent COVID19” or “post-infectious” or “postinfectious” or “post-infection” or “postinfection” or “late complication” or “late complications” or “late COVID” or “late COVID-19” OR “late COVID19” or “multi-system syndrome” or “multisystem syndrome” or “inflammatory multisystem” or “inflammatory multi-system” or PIMS or “PIMS-TS” or “multisystem Inflammatory” or “multi-system inflammatory” or MIS or “MIS-C” or MISC or MISTIC

Study design

Case series/case control/cohort; cross-sectional; other; time series; single arm/controlled before after; unclear

Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register (CCSR)

The register contains study reports from several sources, including:

weekly searches of PubMed;

daily searches of ClinicalTrials.gov;

weekly searches of Embase.com;

weekly searches of the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP);

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

Questions on the article in issue 4/2023:

Post-COVID Syndrome

The submission deadline is 26 January 2024. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

According to WHO estimates, what percentage of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 develop post-COVID syndrome (as of 2021)?

1–3%

5–10%

10–20%

25–30%

30–40%

Question 2

Which of the following biographical factors are both currently known risk factors for post-COVID syndrome?

Young age, Asian

Advanced age, male sex

Advanced age, Caucasian

Middle age, female sex

Young age, male sex

Question 3

How high was the prevalence of PCS among triple-vaccinated individuals in the UK’s “COVID Surveillance Study” (as of 2022)?

Under 5%

Approximately 10%

Approximately 15%

Under 2%

Over 15%

Question 4

Which vasocontrictor was elevated in a third of patients with PCS in the endothelial dysfunction test 6 months following mild COVID-19 infection?

Adrenaline

Vasopressin

Angiotensin

Nicotine

Endothelin-1

Question 5

What does the abbreviation PICS stand for in the text?

Post-interventional covid syndrome

Post-intensive care syndrome

Post-infectious covid syndrome

Post-infectious cardiac syndrome

Post-interventional cardiac syndrome

Question 6

According to the WHO definition, what is the earliest point at which post-COVID syndrome can be diagnosed in a patient with symptoms persisting for at least 2 months?

> 2 Weeks following acute infection

> 4 Weeks following acute infection

> 8 Weeks following acute infection

> 12 Weeks following acute infection

> 16 Weeks following acute infection

Question 7

Which term is used for the sparing, dosed management of a patient’s energy resources in the case of chronic fatigue syndrome?

Tiptoeing

Walking

Crawling

Sneaking

Pacing

Question 8

The text mentions which important differential diagnosis that needs to be borne in mind in the case of suspected PCS due to its high incidence (approximately 8%) in the adult population?

Hitherto undiagnosed malignancies

Giardiasis

Depression

Previous myocardial infarction

Hepatitis

Question 9

Autoantibodies can be detected in the acute phase of disease and in PCS. Autoantibodies against which of the following structures (also mentioned in the text) have already been detected in patients with PCS?

Interleukin-1 and GABA-A receptors

Potassium channels and Fc receptors

Sodium channels and RAS proteins

Sodium-potassium ATPase and dopamine receptors

Type-1 interferons and G-protein-coupled receptors

Question 10

According to the article, which symptom does not belong to the typical gastrointestinal symptoms of PCS?

Reflux

Nausea

Diarrhea

Loss of appetite

Abdominal pain

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Rye.

Footnotes

Other collaborators

Prof. Dr. med. Reinhard Berner, Prof. Dr. med. Dr. h. c. Manfred Dietel,

Prof. Dr. med. Hans Drexler, Dr. med. Pedram Emami,

Dr. med. Christiana Franke, Dr. med. Johannes Grundmann,

Prof. Dr. med. Ulrich Hegerl, Prof. Dr. med. Karl Hörmann,

Dr. med. Susanne Johna, Univ.-Prof. Dr. med. Florian Klein,

Prof. Dr. med. Thea Koch, Prof. Dr. med. Wilhelm-Bernhard Niebling,

Prof. Dr. med. Johannes Oldenburg, Prof. Dr. med. Klaus Püschel,

Dr. med. Gerald Quitterer, Dr. med. (I) Klaus Reinhardt,

Dr. med. Anett Reißhauer, Prof. Dr. med. Carmen Scheibenbogen,

Prof. Dr. med. Stefan Schreiber, Dr. med. Martina Wenker,

Prof. Dr. med. Fred Zepp

Acknowledgments

The members of the Working Group would like to thank Professor Dr. med. Nicole Skoetz as well as Ana-Mihaela Bora, Caroline Hirsch, Ina Monsef, and Carina Wagner (Working Group on Evidence-Based Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Cologne, Germany [AöR]) for carrying out the systematic literature search.

The statement (6) on which this review article is based, “Post-COVID-Syndrom (PCS)” (post-COVID syndrome [PCS]) (6), was discussed by the Executive Board and the Plenary Meeting of the Scientific Advisory Board on 23.09.2022 and was discussed and adopted by the Executive Board of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) on 23 September 2022.

Conflict of interest statement

PD Dr. Adorjan received funding from the Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care (Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege) as well as the Bavarian State Office for Health and Food Safety (Bayerisches Landesamt für Gesundheit und Lebensmittelsicherheit).

Prof. Behrends received project funding from the Bavarian State Ministry of Science and the Arts (Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst), Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care (Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege), German University Medicine Network (Netzwerk Universitätsmedizin), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung), German Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesgesundheitsministerium), as well as from Weidenhammer-Zöbele Foundation (Weidenhammer-Zöbele-Stiftung) and the Lost Voices Foundation (Lost-Voices Stiftung). She received honoraria from the German Alliance for Pediatric and Adolescent Rehabilitation (Bündnis Kinder- und Jugendreha). She is medical advisor to the German Society for ME/CFS and and a founding member of the board of the German Long COVID medical association.

Prof. Ertl received funding from the Bavarian State Ministry of Science and the Arts (Bayerischen Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst).

Prof. Suttorp is a member of the advisory board of Biontech.

Prof. Lehmann received funding from the North Rhine-Westphalia Ministry of Culture and Science (Ministerium für Kultur und Wissenschaft NRW), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung), the German Center for Infection Research (Deutsches Zentrum für Infektionsforschung), the German University Medicine Network (Netzwerk Universitätsmedizin), and the German Federal Joint Committee/Innovation Fund (gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss/Innovationsfonds). She received speaker’s fees from Biontech, Gilead, Novartis, Pfizer, ViiV, and Janssen. She is a founding member of the board of the German Long COVID medical association.

Prof. Hallek declares that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Augustin M, Schommers P, Stecher M, et al. Post-COVID syndrome in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100122. 100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626–631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet. 2021;398(10302):747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amin-Chowdhury Z, Ladhani SN. Causation or confounding: why controls are critical for characterizing long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:1129–1130. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01402-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundesärztekammer. Post-COVID-Syndrom (PCS) Deutsch Arztebl DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2022.Stellungnahme_PCS (last accessed on 4 January 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made Long Covid. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. 113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AWMF online—Das Portal der wissenschaftlichen Medizin. S1-Leitlinie Post-COVID/Long-COVID. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/020-027l_S1_Post_COVID_Long_COVID_2021-07.pdf (last accessed on 21 June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 (last accessed on 22 June 2022) doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castanares-Zapatero D, Chalon P, Kohn L, et al. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann Med. 2022;54:1473–1487. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2076901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181:1016–1035e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charfeddine S, Ibn Hadj Amor H, Jdidi J, et al. Long COVID 19 syndrome: is it related to microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction? Insights from TUN-EndCOV Study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.745758. 745758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaebler C, Wang Z, Lorenzi JCC, et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;591:639–644. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03207-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang EY, Mao T, Klein J, et al. Diverse functional autoantibodies in patients with COVID-19. Nature. 2021;595:283–288. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03631-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puntmann VO, Martin S, Shchendrygina A, et al. Long-term cardiac pathology in individuals with mild initial COVID-19 illness. Nat Med. 2022;28:2117–2123. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02000-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:210–216. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czaplicki A, Reich H, Hegerl U. Lockdown measures against the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic: negative effects for people living with depression. Front Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.789173. 789173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyungerel B, Paulina S, Justin C, Kylie A, Paul G. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on long COVID: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medrxiv. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Notarte KI, Catahay JA, Velasco JV, et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101624. 101624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28:1461–1467. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayoubkhani D, Bosworth M. Self-reported long COVID after infection with the Omicron variant in the UK: 18 July 2022: The likelihood of self-reported long COVID after a first coronavirus (COVID-19) infection compatible with the Omicron BA1 or BA.2 variants, compared with the Delta variant, using data from the COVID-19 Infection Survey. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/selfreportedlongcovidafterinfectionwiththeomicronvariant/18july2022#toc (last accessed on 26 August 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson EJ, Williams DM, Walker AJ, et al. Long COVID burden and risk factors in 10 UK longitudinal studies and electronic health records. Nat Commun. 2022;13 doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30836-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borch L, Holm M, Knudsen M, Ellermann-Eriksen S, Hagstroem S. Long COVID symptoms and duration in SARS-CoV-2 positive children—a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:1597–1607. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawke LD, Nguyen ATP, Ski CF, Thompson DR, Ma C, Castle D. Interventions for mental health, cognition, and psychological wellbeing in long COVID: a systematic review of registered trials. Psychol Med. 2022:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722002203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fugazzaro S, Contri A, Esseroukh O, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halabchi F, Selk-Ghaffari M, Tazesh B, Mahdaviani B. The effect of exercise rehabilitation on COVID-19 outcomes: a systematic review of observational and intervention studies. Sport Sci Health. 2022:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11332-022-00966-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandan JS, Brown K, Simms-Williams N, et al. Non-pharmacological therapies for postviral syndromes, including Long COVID: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057885. e057885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vieira A, Pinto A, Garcia B, Eid RAC, Mol CG, Nawa RK. Telerehabilitation improves physical function and reduces dyspnoea in people with COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 conditions: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2022;68:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2022.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ. 2022;377 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069676. e069676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DGKJ-Konvent-Gesellschaften mA. Einheitliche Basisversorgung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Long COVID. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00112-021-01408-1.pdf (last accessed on 22 June 2022) doi: 10.1007/s00112-021-01408-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonelli M, Pujol JC, Spector TD, Ourselin S, Steves CJ. Risk of long COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2022;399:2263–2264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00941-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:43–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yong SJ. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis (Lond) 2021;53:737–754. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1924397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yong SJ. Persistent brainstem dysfunction in Long-COVID: a hypothesis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12:573–580. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dennis A, Wamil M, Alberts J, et al. Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391. e048391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weng J, Li Y, Li J, et al. Gastrointestinal sequelae 90 days after discharge for COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:344–346. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Rajan S, Khunti K, Alwan N, et al. In the wake of the pandemic: preparing for Long COVID. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Perego E, Balzarini F, Botteri M, et al. Emergency treatment in Lombardy: a new methodology for the pre-hospital drugs management on advanced rescue vehicles. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:111–118. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i3-S.9421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Nauen DW, Hooper JE, Stewart CM, Solomon IH. Assessing brain capillaries in coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:760–762. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. Afirst step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Qi J, Zhou Y, Hua J, et al. The scRNA-seq expression profiling of the receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 reveals human organs susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Chen M, Shen W, Rowan NR, et al. Elevated ACE-2 expression in the olfactory neuroepithelium: implications for anosmia and upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01948-2020. 562001948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Salamanna F, Maglio M, Landini MP, Fini M. Body localization of ACE-2: on the trail of the keyhole of SARS-CoV-2. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.594495. 594495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Haffke M, Freitag H, Rudolf G, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and altered endothelial biomarkers in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) J Transl Med. 2022;20 doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Hohberger B, Ganslmayer M, Lucio M, et al. Retinal microcirculation as a correlate of a systemic capillary impairment after severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.676554. 676554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Kresch E, Achua J, Saltzman R, et al. COVID-19 endothelial dysfunction can cause erectile dysfunction: histopathological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of the human penis. World J Mens Health. 2021;39:466–469. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.210055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Chu KY, Nackeeran S, Horodyski L, Masterson TA, Ramasamy R. COVID-19 infection is associated with new onset Erectile Dysfunction: insights from a national registry. Sex Med. 2022;10 doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100478. 100478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Patterson BK, Francisco EB, Yogendra R, et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 protein in CD16+ monocytes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 months post-infection. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.746021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Zollner A, Koch R, Jukic A, et al. Postacute COVID-19 is characterized by gut viral antigen persistence in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2022;2:495–506e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Wallukat G, Hohberger B, Wenzel K, et al. Functional autoantibodies against G-protein coupled receptors in patients with persistent Long-COVID-19 symptoms. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Franke C, Ferse C, Kreye J, et al. High frequency of cerebrospinal fluid autoantibodies in COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;93:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Su Y, Yuan D, Chen DG, et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. 2022;185:881–895e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Pierce JD, Shen Q, Cintron SA, Hiebert JB. Post-COVID-19 syndrome. Nurs Res. 2022;71:164–174. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:168–175. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Mehandru S, Merad M. Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:194–202. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Melms JC, Biermann J, Huang H, et al. A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Nature. 2021;595:114–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Witte J, Zeitler A, Batram M, Diekmannshemke J, Hasemann L. Kinder- und Jugendreport 2022: Kinder- und Jugendgesundheit in Zeiten der Pandemie Eine Studie im Auftrag der DAK Gesundheit. www.dak.de/dak/download/wissenschaftlicher-text-von-dr–witte-2572496.pdf (last accessed on 2 September 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E24.Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf. COPSY-Längsschnittstudie. www.uke.de/kliniken-institute/kliniken/kinder-und-jugendpsychiatrie-psychotherapie-und-psychosomatik/forschung/arbeitsgruppen/child-public-health/forschung/copsy-studie.html (last accessed on 2 September 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E25.Office for National Statistics (ONS) UK. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection survey, UK 27 May 2022: percentage of people testing positive for coronavirus (COVID-19) in private residential households in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, including regional and age breakdowns. / www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/27may2022 (last accessed on 2 September 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E26.Amalakanti S, Arepalli KVR, Jillella JP. Cognitive assessment in asymptomatic COVID-19 subjects. Virusdisease. 2021;32:146–149. doi: 10.1007/s13337-021-00663-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Nakamura ZM, Nash RP, Laughon SL, Rosenstein DL. Neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23 doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Nalbandian A, Desai AD, Wan EY. Post-COVID-19 condition. Annu Rev Med. 2022 doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-043021-030635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Ahmadi Hekmatikar AH, Ferreira Junior JB, Shahrbanian S, Suzuki K. Functional and psychological changes after exercise training in Post-COVID-19 patients discharged from the hospital: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Arnold DT, Milne A, Samms E, Stadon L, Maskell NA, Hamilton FW. Are vaccines safe in patients with Long COVID? A prospective observational study. Medrxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- E31.Uniklinik Köln. Post-COVID-Sprechstunde. www.uk-koeln.de/patienten-besucher/post-covid-zentrum/klinische-versorgung-und-ambulanzen/#c9474 (last accessed 02 January 2023) [Google Scholar]

- E32.LMU Klinikum. Ein Jahr Corona-Pandemie in Deutschland. www.lmu-klinikum.de/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/ein-jahr-corona-pandemie-in-deutschland/3dad60a0892ab5a5 (last accessed on 22 June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E33.Universität Regensburg. Anlaufstelle für junge Menschen mit Long Covid & Pädiatrischem Multiorgan Immunsyndrom (PMIS) www.kiss-regensburg.de/nc/aktuelles/detailseite/news/anlaufstelle-fuer-junge-menschen-mit-long-covid-paediatrischem-multiorgan-immunsyndrom-pmis/ (last accessed on 2 September 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E34.München Klinik Schwabing. Post-Covid-Syndrom (Long Covid) Long Covid Ambulanz: Hilfe bei Covid-Spätfolgen für Kinder, Jugendliche und junge Erwachsene bis 18 Jahre. www.muenchen-klinik.de/krankenhaus/schwabing/kinderkliniken/kinderheilkunde-jugendmedizin/spezialgebiete-kinder-klinik/kinder-immunologie-immunschwaeche-immundefekt/therapie-kinder-immunologie-immundysregulation/long-covid-kinder-jugendliche/ (last accessed on 2 September 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E35.Universitätsklinikum Carl Gustav Carus Dresden. Long-/Post-COVID-Ambulanz für Kinder und Jugendliche. www.uniklinikum-dresden.de/de/das-klinikum/kliniken-polikliniken-institute/kik/bereiche/ambulanzen/anmeldung-postcovid (last accessed on 14 November 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E36.Universitätsklinikum Jena. Post-/ Long-Covid 19 Ambulanz für Kinder und Jugendliche ./ www.uniklinikum-jena.de/cscc/Post_COVID_Zentrum/Post_COVID+Ambulanzen/Long_+_+Post_COVID+Ambulanz+Kinder+und+Jugendliche-p-1420.html (last accessed on 9 Januar 2023) [Google Scholar]

- E37.Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Post-COVID-Netzwerk der Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. https://pcn.charite.de/ (last accessed on 7 September 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E38.Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege. Modellprojekt „Post-COVID-Kids Bavaria“: Teilprojekt 2 „Post-COVID-Kids Bavaria—PCFC“ (Post-COVID Fatigue Center) www.stmgp.bayern.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021_post-covid-kids-bavaria-2.pdf (last accessed on 22 June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E39.Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege. Modellprojekt „Post-COVID-Kids Bararia“: Teilprojekt 1, „Post-COVID Kids Bavaria. Langzeitefeffekte von Coronavirusinfektionen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Bayern: Erkennung und frühzeitige Behandlung von Folgeerkrankungen“. www.stmgp.bayern.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021_post-covid-kids-bavaria-1.pdf (last accessed on 22 June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E40.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Taquet M, Dercon Q, Harrison PJ. Six-month sequelae of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective cohort study of 10,024 breakthrough infections. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;103:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Whitaker M, Elliott J, Chadeau-Hyam M, et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community study of 606,434 people in England. Nat Commun. 2022;13 doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29521-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Anaya J-M, Rojas M, Salinas ML, et al. Post-COVID syndrome. A case series and comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Office for National Statistics (ONS) UK. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK 2021, 1 April 2021. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021 [Google Scholar]

- E46.Kandemirli SG, Altundag A, Yildirim D, Tekcan Sanli DE, Saatci O. Olfactory bulb MRI and paranasal sinus CT findings in persistent COVID-19 anosmia. Acad Radiol. 2021;28:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Konopka KE, Perry W, Huang T, Farver CF, Myers JL. Usual interstitial pneumonia is the most common finding in surgical lung biopsies from patients with persistent interstitial lung disease following infection with SARS-CoV-2. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;42 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101209. 101209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Maccio U, Zinkernagel AS, Schuepbach R, et al. Long-term persisting SARS-CoV-2 RNA and pathological findings: lessons learnt from a series of 35 COVID-19 autopsies. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.778489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Yang J-K, Lin S-S, Ji X-J, Guo L-M. Binding of SARS coronavirus to its receptor damages islets and causes acute diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Wendisch D, Dietrich O, Mari T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers profibrotic macrophage responses and lung fibrosis. Cell. 2021;184:6243–6261e27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E51.Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Guedj E, Campion JY, Dudouet P, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;48:2823–2833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E53.Stefanou MI, Palaiodimou L, Bakola E, et al. Neurological manifestations of long-COVID syndrome: a narrative review. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2022;13 doi: 10.1177/20406223221076890. 20406223221076890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E54.Moldofsky H, Patcai J. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E55.Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E56.Sansone A, Mollaioli D, Limoncin E, et al. The sexual long COVID (SLC): erectile dysfunction as a biomarker of systemic complications for COVID-19 long haulers. Sex Med Rev. 2022;10:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E57.Rathmann W, Kuss O, Kostev K. Incidence of newly diagnosed diabetes after Covid-19. Diabetologia. 2022;65:949–954. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05670-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Systematic literature search

For the statement “Post-COVID-Syndrom (PCS)” (post-COVID syndrome) of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) (6), a systematic search relating to the publication period 2020–2022 was carried out for guidelines, systematic review articles, and randomized controlled studies in medical databases such as the Cochrane COVID-19 study register, for which update searches for studies on humans are performed daily to weekly in numerous specialist databases (https://community.cochrane.org/about-covid-19-study-register). Other sources, such as MEDLINE, the WHO Register, and the Guidelines International Network database were also included in the search. To complete the data, a search was additionally carried out in the Cochrane COVID-19 study register for recent observational studies published in 2022. Peer-reviewed full-text articles were taken into consideration, as were preprints (as yet non-peer-reviewed specialist articles) published in MedRxiv (www.medrxiv.org/). No restrictions were set in terms of language. Searches were carried out between 19.07.2022 and 22.07.2022.