Abstract

The synthesis, electrochemistry, and photophysical characterization of five 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine ruthenium complexes (Ru-tpy complexes) is reported. The electrochemical and photophysical behavior varied depending on the ligands, i.e., amine (NH3), acetonitrile (AN), and bis(pyrazolyl)methane (bpm), for this series of Ru-tpy complexes. The target [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ complexes were found to have low-emission quantum yields in low-temperature observations. To better understand this phenomenon, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to simulate the singlet ground state (S0), Te, and metal-centered excited states (3MC) of these complexes. The calculated energy barriers between Te and the low-lying 3MC state for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ provided clear evidence in support of their emitting state decay behavior. Developing a knowledge of the underlying photophysics of these Ru-tpy complexes will allow new complexes to be designed for use in photophysical and photochemical applications in the future.

1. Introduction

Metal complexes have been extensively studied and have been widely utilized in various aspects of research during the past 50 years.1−15 It can be generalized from these studies that the relative energetics between triplet metal-to-ligand charge transfer emitting states (3MLCT, Te) and triplet metal-centered excited states (3MC, emission quencher) of ruthenium polypyridine complexes would determine the suitability for a specific photochemical application.16,17 For example, the rate constant for an internal conversion from 3MLCT to 3MC, kic (3MLCT → 3MC state), for Ru-polypyridine complexes quenches the phosphorescence at room temperature (RT),18 a characteristic that could be harmful to photodynamic therapy (PDT) but favorable for photochemotherapeutic (PCT) applications.19,20

The electronic excited states of transition-metal complexes were first demonstrated experimentally by Crosby during 1970–1975.7,21−23 In these seminal studies, the behavior of excited states of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine) was experimentally probed by the emission spectra at 77 K. Since then, [Ru(bpy)3]2+ has become a classic model of ruthenium polypyridine complexes, and Ru polypyridyl analogues of this complex have been widely discussed in many studies.6,24−29 In addition, based on their photophysical and photochemical character, this class of complexes has been utilized in a variety of applications, including in dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs),24,25,30−32 photocatalysis,33,34 PCT,35,36 and PDT.37,38

Comparably, [Ru(tpy)2]2+ is another classic model of a ruthenium polypyridine complex. Photophysical and photochemical properties of [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine) and its analogues have been reported in a large number of publications in the past 40 years.39−45 [Ru(tpy)2]2+ appears to have different structural characteristics in comparison to [Ru(bpy)3]2+ with efficient excited-state quenching at room temperature. For example, the bite angle between Ru and tpy is about 157°, which is an unfavorable angle and causes the Ru-tpy moiety to have a weaker ligand field than that for a Ru-bpy moiety.46 Consequently, [Ru(tpy)2]2+ should have a more stable ligand-field state (metal-centered state, 3MC state) than [Ru(bpy)3]2+, a characteristic that enhances the probability of an ic (3MLCT → 3MC state) and a decreased energy barrier (3MLCT → 3MC state) for [Ru(tpy)2]2+.44 This perspective is further supported by the observations of nonemission at RT for [Ru(tpy)2]2+ and phosphorescence emission at RT for [Ru(bpy)3]2+.2,45,47−49

The energy gap (3MLCT → 3MC state) is an important parameter that determines the probability of ic (3MLCT → 3MC state). If the 3MC state of a Ru-polypyridine complex is lower in energy than its 3MLCT state, ic (3MLCT → 3MC state) can take place easily, being favorable for PCT. On the other hand, if a complex has a higher 3MC state over the 3MLCT state, the probability of ic (3MLCT → 3MC state) would decrease and would have more potential for PDT. The presence of the tpy ligand could result in a stable 3MC state as mentioned above, and varying the second ligand may introduce the possibility of tuning the relative energetics between 3MC and 3MLCT states.

In this study, we attempt to control the relative energetics between 3MLCT and 3MC through adjusting the ligands of Ru-tpy complexes, being characterized by joint experimental and theoretical approaches. A series of Ru-tpy complexes were synthesized, and the ground and excited states were comprehensively characterized. The phosphorescence emission energies of these Ru-tpy complexes were measured as 13 000–18 000 cm–1 (555–769 nm) at 77 K in the presence of amine (NH3), acetonitrile (AN), and bis(pyrazolyl)methane (bpm) ligands. Furthermore, the nonradiative decay rate constant (knr) of the Te state at room temperature may contain the kic in the ruthenium polypyridine complex system. However, the knr of a classical Ru-bpy complex can be inferred to be much greater than kic under low-temperature conditions at 77 K, as it complies with the energy gap law.3,50,51 This consequently suggests that a series of classical Ru-bpy complexes could be used as a reference to compare with other series of complexes. In the present study, the series of classical Ru-bpy complexes (1)–(5) (the structures of these complexes are shown in Figure S1A1)51 were also utilized to highlight the special properties of Ru-tpy complexes (a)–(e) (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Ru-tpy Complexes Used in This Study.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Synthesis of Compounds

In this work, five Ru-tpy complexes (a)–(e) were prepared, and the skeletal structures of these target Ru-tpy complexes are shown in Scheme 1. The [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a) and [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c) were prepared by literature procedures.41,52 Details concerning the starting material and methods used for the synthesis of the new complexes [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e) are presented in Section S1. The NMR (1H and 13C) spectra and elemental analyses for these complexes are shown in Section S1.

2.2. Instrumentation

Details concerning the electrochemistry, absorption spectra, 77 K emission, 77 K emission lifetime, and 77 K emission quantum yield (Φ(em)) measurements are presented in Section S1. On the other hand, the 77 K condition would decrease the probability of another quenching state and allow focusing on probing the 3MLCT emission.

2.3. Computational Details

The optimizations of the geometry for the singlet ground state (S0) and the triplet excited states (Te and 3MC) for all of the Ru-tpy complexes were characterized at the density functional theory (DFT) level with the B3PW91 functional53−56 and the Stuttgart/Dresden effective core potential (SDDall) basis set57−59 in the Gaussian 16 package.60 To confirm the minimum structures, harmonic frequency analyses were carried out. The theoretical electronic absorption spectra were simulated by time-dependent DFT calculations with the IEF-PCM solvation model (acetonitrile).61−63 The natural transition orbitals (NTOs)64 for the selected excited states for the Ru-tpy complexes were calculated to provide a better vision of the excited states for TD-DFT (see Figure S3C1A–C5C).

Additionally, the B3LYP,65,66 PBE0,67 CAM-B3LYP,68 and LC-wPBE69 functionals were benchmarked with B3PW91 for describing the low-energy 1MLCT electronic absorption envelopes of [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (see Figure S3A1). It appeared that data collected using the B3PW91 functional are in better agreement with the experimental absorption peaks, being consistent with other early reports and our previous studies.3,50,51,70 Therefore, the B3PW91 functional was finally utilized to simulate the ground and excited states of the Ru-tpy complexes.

3. Results

3.1. Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Properties of the Complexes

3.1.1. Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed at room temperature for each complex in acetonitrile solutions containing 0.1 M n-TBAH, and the measured potentials are listed in Table S1. All of the series of Ru-tpy complexes showed reversible Ru-based oxidation and reversible ligand-based reduction. The cyclic voltammogram for [Ru(tpy)2]2+ displayed two tpy0/1– oxidation couples at −1.27 and −1.51 V vs Ag/AgCl, and the other Ru-tpy complexes exhibited only one tpy0/1– oxidation couple in the negative potential (see Figure S2A1).

3.1.2. UV–Vis Absorption Spectroscopy

The room-temperature (RT) absorption spectra for the Ru-tpy complexes (a)–(e) are shown in Figure 1, and the low-temperature absorption spectra for the Ru-tpy complexes (a)–(e) are shown in Figure S2B3. In Figure 1, the spectra of [Ru(tpy)2]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ were in agreement with previously reported spectra.41,44 For all of the complexes (a)–(e), the low-energy absorption bands were dominated by MLCT absorption and were assigned as the Ru(dπ) → tpy (π*) CT band. The absorbance maximum (εmax) of two Ru-tpy moieties for complex (a), [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (black curve in the lower panel of Figure 1), was about 15 800 M–1 cm–1 (at 21 000 cm–1), a value that is about 3 times larger than the εmax of one Ru-tpy moiety for the target complexes (b)–(e) (about 4000–5000 M–1 cm–1 as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Top panel: 298 K absorption spectra of target complexes (Ru-tpy complexes) [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b, red), [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c, blue), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d, dark cyan), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e, magenta) in acetonitrile; lower panel: 298 K absorption spectra of target complexes [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a, black).

On the other hand, in Figure 1, when comparing the energies of the absorption maximum (hνmax(abs)) of 1MLCT absorption of [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b, red) and [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c, blue), it could be observed that the hνmax(abs) of [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ is higher than that of [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (see Table 1), a difference that can be attributed to the significant disparity of the ligand field for the π-withdrawing AN ligand and the σ-only donor NH3 ligand. A similar case can be observed when comparing the hνmax(abs) of [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d, dark cyan) and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e, magenta).

Table 1. Ambient Absorption, 77 K Emission, Emission Decay Constants, and Emission Yield of the Ru-tpy Complexesa.

| 77 K emissionb | 77 K lifetimeb |

77 K quantum yieldb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| code | complexes | hνmax(abs), cm–1/103, 298 K (87 K)a | hνmax(em), cm–1/103 (hνave(em), cm–1/103)c | kobs, μs–1 (τmean, μs)d,e | kr, μs–1 f | knr, μs–1 f | Φem × 104 |

| (a) | [Ru(tpy)2]2+ | 21.03 (20.92) | 16.55 (15.70) | 0.09 (11.17) | 0.030 | 0.059 | 3400 ± 700 |

| (b) | [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ | 18.50 (17.48) | 13.01 (12.50) | 2.63 (0.38) | 0.025 | 2.607 | 95 ± 15 |

| (c) | [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ | 22.96 (22.62) | 18.07 (16.86) | 0.06 (16.2) (60%) | 2090 ± 200 | ||

| 0.58 (1.72) (40%) | |||||||

| (d) | [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ | 21.51 (21.46) | 14.47 (13.69) | 0.78 (1.28) | 0.031 | 0.75 | 399 ± 50 |

| (e) | [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ | 23.09 (23.36) | 15.96 (15.13) | 0.18 (5.71) | 0.015 | 0.16 | 840 ± 260 |

In acetonitrile.

In butyronitrile.

νave ≈ ∫νmImdνm/∫Imdνm.

Mean emission lifetime (τ).

Mean excited-state decay rate constant, kobs=1/τ.

kr is the radiative rate constant, and knr is the nonradiative rate constant, kobs = kr + knr.

3.1.3. 77 K Emission Spectra

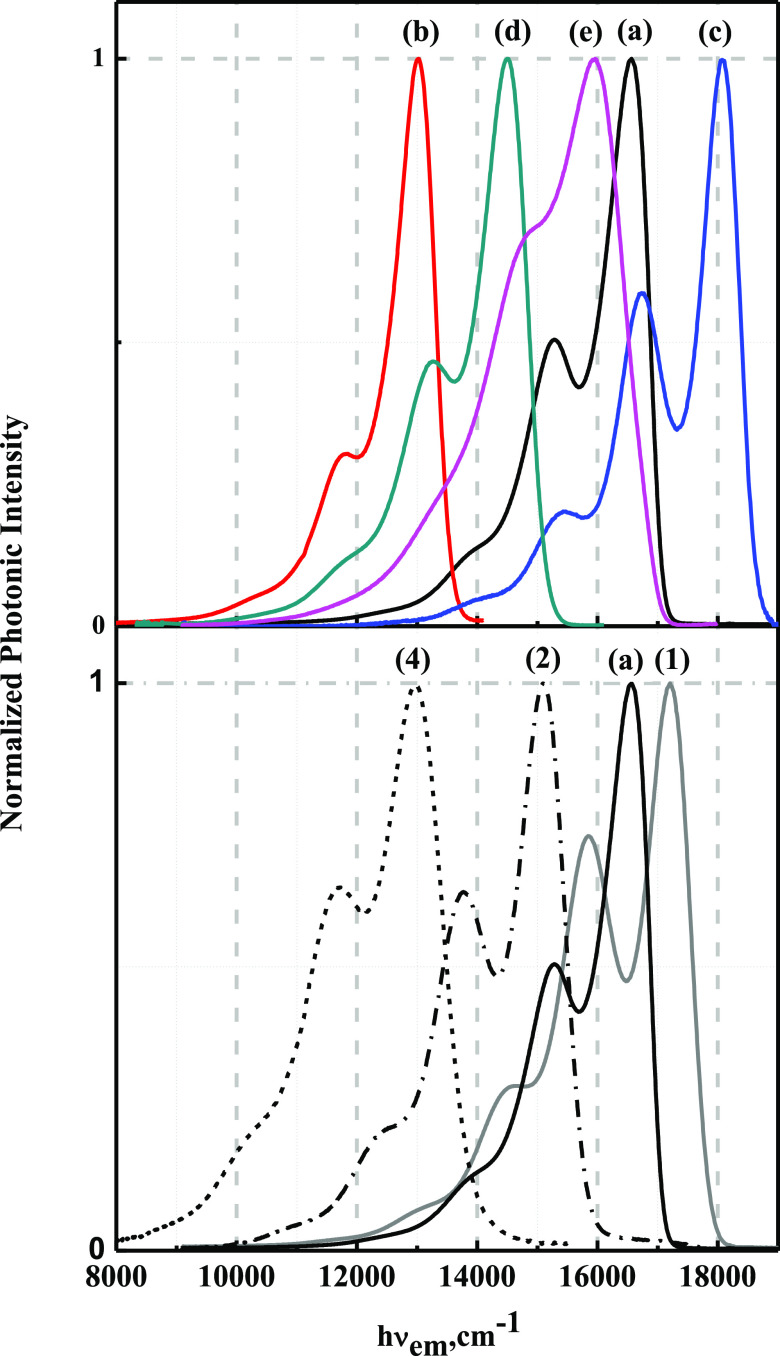

The 77 K emission from the Ru(dπ) → bpy(π*) 3MLCT state was observed for the Ru-bpy complexes (1), (2), and (4),3,71 and from the Ru(dπ) → tpy(π*) 3MLCT state, the emission was observed for Ru-tpy complexes (a)–(e),40,49 respectively; see Figure 2. The band shapes of the 77 K emission for the Ru-bpy and Ru-tpy complexes consist of a fundamental band (I0′–0) and vibronic sidebands (I0′–j, and j ≠ 0).72 For example, the 77 K emission spectra of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (1, gray) shows a fundamental band at about 16 500–18 000 cm–1 and a vibronic sideband at about 15 000–17 000 cm–1 (sum of first-order vibronic components, I0′–1). Basically, first-order vibronic sidebands originate from some vibrational modes (distortion modes). According to the literature, the assignment of intense vibrational modes for [Ru(bpy)3]2+ is in the inter-ring of the bpy ligand. The relative intensities of the first-order vibrational mode contributions were obtained from time-dependent resonance-Raman (TD-rR) data.72,73 Unfortunately, TD-rR data is not easy to obtain and no TD-rR data for the Ru-tpy complexes was found in the literature, so we were unable to perform an analysis of the contribution of the first-order vibronic mode for the Ru-tpy complexes. However, we were still able to observe that the intensity of the vibronic sideband in the emission spectra of the Ru-tpy complexes was lower than that for the Ru-bpy complexes with a similar emission energy (hνem) region. For example, in Figure 2, the intensity of the vibronic sideband for complex (b) is smaller than that for complex (1) with similar emission energies. On the other hand, the intensities of the vibronic sideband in the 3MLCT emissions of the class of Ru-bpy complexes decrease with decreasing energy of the 3MLCT emission,51,72,74 a trend that was also observed in Ru-tpy complexes. Moreover, the emission spectra of [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ contain a broad and special vibronic sideband. As mentioned above, each of the Ru-tpy complexes should have its intrinsic Raman vibronic contribution to the emission intensity.

Figure 2.

Top panel: 77 K emission spectra of all of the Ru-tpy complexes in butyronitrile solvent glasses: [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a, black), [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b, red), [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c, blue), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d, dark cyan), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e, magenta); lower panel: 77 K emission spectra of target complexes [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a, black) and reference complexes [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (1, gray), [Ru(bpy)2(en)]2+ (2, dash dot), and [Ru(bpy)(en)2]2+ (4, black dash).

3.1.4. Comparison of the 77 K Emission Quantum Yield for the Target Complexes

Basically, the 77 K knr of the typical Ru-bpy complexes was not influenced by the kic (emitting 3MLCT state to 3MC state) and the 77 K emission quantum yields (QYs) for the typical Ru-bpy complexes (red squares, codes (1)–(5); see Figure S1A1), and this decreased systematically with decreasing hνave(em) (this trend is not rigorously considered to be fundamental; see the red dashed line in Figure 3).3,51 On the other hand, the 77 K quantum yields (QY) for the Ru-tpy complexes (c) and (e) with an AN ligand are lower than expected in the given emission energy, as indicated by the blue dashed line for the 77 K QY of the Ru-tpy complexes in Figure 3 (see black arrow in Figure 3). On the basis of the Ru-tpy complexes, it is possible that a 3MC state exists that could cause emission quenching. We assume therefore that the unusually low 77 K quantum yield for complexes (c) and (e) that could exist as 3MC excited states would reduce the value of the quantum yield at 77 K. This conclusion is consistent with our DFT calculations that have been discussed in detail in Section 4.1. As mentioned above, in the case of the Ru-tpy complexes, it is easier to control the probability of ic (3MLCT → 3MC) compared to the Ru-bpy complexes, a result that causes the Ru-tpy complex to have more flexibility for different applications.

Figure 3.

Comparison of ln(Φ) vs hνave(em) for typical Ru-bpy complexes (red square) and target Ru-tpy complexes: [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a, blue square), [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b, blue square), [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c, green square), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d, blue square), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e, green square). The red-dashed least-square line indicates typical Ru-bpy complexes3 (1–5, red square) and the blue-dashed least-square line indicates target Ru-tpy complexes (a, b, d, blue square); the trend for these data is not considered to be rigorously fundamental.

3.1.5. 77 K Emission Lifetimes

To gain insights into the photophysical behavior of the Ru complexes, we probed the emission decay lifetime (τem) for Ru-tpy complexes. As shown in Table 1, all of the Ru-tpy complexes are marked by their 3MLCT excited-state lifetimes with one-exponential decay fitting, except for complex (c), [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+. The lifetime of [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ presents two-exponential decay (16.2 μs, 60%; and 1.72 μs, 40%), and the longer one could be characterized by the relaxation process Ru-tpy 3MLCT → ground state (S0); this data, which is similar to the lifetime of [Ru(tpy)2]2+ in the given region, and the short-lifetime component could be attributed to the process 3MLCT → 3MC. This behavior has been discussed in Section 4.

On the other hand, the function of the observed rate constant (kobs) from the emission decay lifetime (τem) could be given by1

| 1 |

where kr is a radiative rate constant, knr is a nonradiative rate constant, and kq is the quenching reaction rate constant. Additionally, if no kq mechanism is operative, the ideal model for emitting state decay, eq 1, would exclude kq and can be given by45,75

| 2 |

According to the formalism eq 1 and eq 2, the knr values can be obtained from emission quantum yield (Φem) and one exponential lifetime data (τem), Φem = kr/kobs, for the Ru-tpy complexes (a), (b), (d), and (e). On the other hand, the behavior of nonradiative decay (knr) for these four target complexes can be compared with the reference complexes (1)∼(5) in the next section.

3.1.6. Comparison of Nonradiative Decay (knr) for Target and Reference Complexes

As the nonradiative decay (knr) at 77 K plays a vital rule in the excited-state decay kinetics, the formalism, eq 3 and eq 4, based on a single distortion mode (hνk) provides a method to probe the knr for different chromophores.76,77

| 3 |

| 4 |

where Cnr ≈ (Heg2)[8π3/(h3νkhνave)]1/2 and A ≈ ln(hνave/λk) – 1. The νk frequency is assumed to be a harmonic distortion mode, Heg is a function of spin–orbit coupling for a phosphorescence-emitting state, and λk is obtained from the Huang–Rhys parameters for this νk mode.78,79 We use the average emission energy (hνave(em), Table 1) for Ru-bpy and Ru-tpy phosphorescence chromophores in eq 4 to fit the red and blue linear plots, respectively; see Figure 4. However, the lifetime of this complex (c) can be fitted by two exponential decays, thus making it impossible to show in Figure 4. In Figure 4, the fits within the Ru-bpy and Ru-tpy complexes reveal that each polypyridine (bpy and tpy) can be described by a single line (red and blue lines), indicating that both MLCT chromophores are in reasonable agreement with the energy gap law.76 The hνave scale in Figure 4 is related to the hνave/hνk scale of a target active distortion mode, νk, and is associated with the harmonic model whose energy approximates that of the emitting state, jhνk ≈ hνave. On the other hand, the slopes of the red and blue lines for two different chromophore complexes are similar, and this resemblance indicates that the trends for the overall results of nonradiative decay for these two different chromophore series have a certain degree of similarity based on the low temperature observation. Since the multiatom molecular-type chromophores can be considered to be multidistortion modes of the photophysical relaxation from an emitting state, attempts were made to find the Huang–Rhys parameters by time-dependent resonance-Raman (TD-rR) observations for many compound systems.78 However, rare Ru-diimine complexes can be obtained with Huang–Rhys parameters by TD-rR observations, such as the [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (15 νk modes)73 and [Ru(NH3)4(bpy)]2+ (11 νk modes).79 The interpretation of the TD-rR results must be rigorous and it is difficult to compare the intrinsic terms (Heg and νk) in Cnr amplitudes between the fitted parameters of least-square lines from Ru-bpy and Ru-tpy chromophores, as shown in Figure 4. Based on Figure 4, the only conclusion is that the low-temperature knr behaviors of the target Ru-tpy (exclude complex c) and the typical Ru-bpy chromophores are similar, and the low-temperature knr relaxation of the typical Ru-bpy chromophore can be considered to be “pure knr relaxation” for 3MLCT → S0.3

Figure 4.

Low-temperature ln(knr) vs hνave(em) for Ru-bpy complexes (red square) and Ru-tpy complexes (blue squares): [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a), [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e). The respective slope, intercept, and R2 for least-squares trend lines are as follows: −1.11, 29.5, and 0.99 (red line for Ru-bpy complexes)3; −1.15, 29.2, and 0.99 (blue line for Ru-tpy complexes).

3.2. Computational Results

3.2.1. Calculated Absorption Spectra

The correlation between ΔE1/2 and the calculated S1 transition (using S0-optimized structures) appeared to maintain a linear relationship, as shown in Figure 5, where ΔE1/2 denotes the difference of the first oxidation E1/2(1st) (RuIII/II) and reduction E1/2(1st) (tpy0/1–) from the electrochemical measurements.

Figure 5.

Correlation of the calculated (B3PW91) S1 transition using S0 minimum geometry and electrochemical data FΔE1/2 for the [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a), [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b), [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e) complexes. The linear dashed line was fitted with the slope of 1.02 and the intercept of −2209.

In Figure 6, the most notable electronic transitions, corresponding to the observed strong absorption peaks in the 15 000–25 000 cm–1 region for complexes (a), (b), and (d), can be assigned to 1MLCT absorption. The detailed electronic structural information representing these experimental observed peaks were characterized by the significant oscillator strengths that were obtained by the TD-DFT calculations. The corresponding natural transition orbitals of these identified theoretical transitions (see Figure 6) appear to be localized on the Ru and tpy ligand for the donor and acceptor orbitals, respectively.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the observed absorption (black curves) and DFT-calculated absorptions (red curves) for B3PW91 functionals in the left panels (red bars for Sn with oscillator strengths in the logarithm scale, log(f)), and their selected NTOs (right panel) of target complexes [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a, panel A), [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b, panel B), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d, panel C).

3.2.2. NTOs and Spin Density of the 3MLCT Emitting State and 3MC States for Complexes (a), (c), and (e)

The minimum structures of the 3MLCT and 3MC states were estimated using the ground-state triplet optimizations, where the partial ligand-dissociated geometries were adopted for the starting point of locating the 3MC minimum structures, as has been demonstrated by Soupart et al.2 in 2018. Additionally, to reconfirm the electronic structures of 3MLCT and 3MC minimum structures, the NTO of the first spin-forbidden S1-to-T1 excitation was exanimated by TD-DFT calculations with the aforementioned triplet minimum structures (see Figure S3D1). Because the bite angle of the tpy ligand is about 157°, the tpy ligand could bring a relatively unfavorable ligand field to the d-electrons of the metal. That could consequently destabilize the 3MLCT state and result in an efficient downhill ic (3MLCT → 3MC). However, not all of the synthesized Ru-tpy complexes appeared to have 3MC states lower than 3MLCT states, as indicated by the success of 3MC triplet optimization calculations. The optimized 3MC structures were only identified in the cases of the [Ru(tpy)2]2+, [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+, and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ complexes, however, and could not be achieved in the cases of [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ complexes (see Figure S3D2–D4). These results are in reasonable agreement with our experimental data (Figure 3).

On the other hand, two distinguishable 3MC minimum structures, 3MCa (equatorial plane) and 3MCb (vertical axis), were identified for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+, respectively. For example, the 3MCa denotes the elongation of the equatorial AN to Ru and 3MCb denotes the case of axial ANs for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (see Figure 7). In Figure 7, the orbital compositions of the NTOs of 3MC and 3MLCT states for each complex show very different results, in that the donor and acceptor of 3MLCT states are located on the Ru and the tpy ligand, respectively, but those of 3MC states are mostly located on Ru. On the other hand, the reorganization energies (λreg) of the 3MC states for each complex are larger than those of the 3MLCT state (see Figures 7 and S3F2).

Figure 7.

Illustrations of DFT results with Te, 3MCa, and 3MCb coordinates for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (right panel) and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (left panel). Mulliken orbital population analyses, reorganization energies (λreg) of Ru, and tpy moieties for the NTOs of Te, 3MCa, and 3MCb excited states.

Because of the consistency between the DFT calculations and the experimental results, these complete results could be used as a database to support and explain the photophysical behavior of Ru-tpy complexes in Section 4.

4. Discussion

4.1. Consideration of the Te (3MLCT Emitting State) and 3MC (Emission Quenching State) States for Observing 77 K Low-Emission Quantum Yields

As demonstrated earlier in Figure 3, the unusual 77 K low quantum yields with hνave(em) and two exponential emission lifetimes for the [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ complex suggested the presence of an accessible 3MLCT → 3MC internal conversion process. As reported by Tsai et al.,70 the elongation of the Ru–N coordination distance from the 3MLCT (Te) structure could lead to the formation of an 3MC minimum structure. In Figure 8, the ic (3MLCT → 3MCb) energy barriers from 3MLCT to the lowest 3MC state (3MCb) for complexes (c) and (e) were approximated using the constrained optimization procedure, in which the distances between Ru and AN were internally scanned by optimizing other degrees of geometric freedom. As shown in Figure 8, the ic (3MLCT → 3MC) energy barrier for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ is about 750 cm–1 (see Figure S3E1A–E1C for the details), and the corresponding barrier for [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ is about 1700 cm–1. The ic (3MLCT → 3MCb) energy barrier for [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ is about 8.5 times larger than 4kBT (about 200 cm–1 at 77 K) at 77 K, while the ratio of [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ is less than 4, suggesting a more accessible reaction channel. If ic (3MLCT → 3MCb) occurs, this assumes that the Te (3MLCT) lifetime should have two different fits for the decay rate constant (kobs1 = kr + knr and kobs2 = kic) and the quantum yield for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ should decrease with the population of ic (3MLCT → 3MCb). The current theoretical characterization findings are consistent with the two exponential lifetime data and low quantum yields of hνave(em) for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ at 77 K.

Figure 8.

Transformation of the Te (3MLCT) state into an 3MCb state for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (top) and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (lower). The Ru–N bond distances are elongated by x Å at each point starting from the Te state. (Ru–N(AN′) for (c), x = 0.072; Ru–N(AN″) for (c), x = 0.030; Ru–N(bpm) for (e), x = 0.018; and Ru–N(AN) for (e), x = 0.094).

The [Ru(tpy)2]2+ complex also had an optimized 3MC state, but with a higher energy than Te (see Figure S3D2). This suggests that [Ru(tpy)2]2+ would have an unfavorable or nonobservable ic (3MLCT → 3MCb) at 77 K. Furthermore, the 3MC excited state for [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ could not be theoretically located using the same computational procedure. This is in good agreement with the experimental data for both complexes with their one-exponential decay lifetime for the kobs relaxation at 77 K. Due to the strong ligand stabilization effect of the amino ligands, the interplay of 3MLCT and 3MC states for complexes (b) and (d) can be schematically shown in Figure S3F1 (right), indicating a nonoptimizable 3MC potential energy surface. Finally, according to these results, the Te relaxation processes for [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ do not have an ic (3MLCT → 3MC) process at 77 K.

5. Conclusions

A series of Ru-tpy complexes, including [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (a), [Ru(tpy)(NH3)3]2+ (b), [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (c), [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(NH3)]2+ (d), and [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(AN)]2+ (e), were synthesized and characterized. It is noteworthy that complexes (c) and (e) show low-emission quantum yields, a behavior that can be attributed to the presence of efficient ic (3MLCT → 3MC) pathways at 77 K. The low-lying 3MC states for complexes (c) and (e) could favor PCT applications, while the low-lying 3MLCT states for complexes (b) and (d) could favor PDT applications. The variation in the innocent ligands plays important roles in tuning the relative stability of the 3MLCT or 3MC minimum. Finally, this work demonstrates a complementary experimental and theoretical approach for the systematic characterization of these Ru-tpy complexes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Instrument Center of National Chung Hsing University for help with measurements of element analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c01006.

S1, experimental section containing the materials (that were used in this work), syntheses, NMR spectra, and elemental analyses of the new Ru-tpy complexes, and the skeletal of reference and target complexes; S2, instrumentation section containing information on the instruments used, photophysical parameter, electrochemistry, low-temperature absorption, and emission spectra for the Ru-tpy complexes; S3, computational section containing the configurations of the HOMOs and LUMOs of TD-DFT-calculated low-energy Sn(S0) excited states, orbital plots of these HOMOs and LUMOs at an S0 geometry, comparisons of the RT-observed and TD-DFT-calculated absorption transitions, the TD-DFT parameters, NTO plots of Sn(S0) and Tn, the orbital population the triplet transition energies, reorganization energies and the potential energy of the first triplet transition at each triplet geometry, and all of the spin densities of each triplet geometry for the Ru-tpy complexes; S3, detailed data for the energy gap of ic (3MLCT → 3MC) for [Ru(tpy)(AN)3]2+ (PDF)

This work was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (Taiwan, ROC) through Grants 110-2113-M-030-003 and 111-2113-M-003-003.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Juris A.; Ceroni P.; Balzani V.. Photochemistry and Photophysics: Concepts, Research, Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Soupart A.; Dixon I. M.; Alary F.; Heully J.-L. DFT rationalization of the room-temperature luminescence properties of Ru(bpy)32+and Ru(tpy)22+: 3MLCT–3MC minimum energy path from NEB calculations and emission spectra from VRES calculations. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2018, 137, 37. 10.1007/s00214-018-2216-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Z.; Cheng C. C.; Chih Y. R.; Lin Y.-T.; Chen H.-Y.; Chen Y.-J.; Endicott J. F. Low Temperature Spectra and DFT Modeling of Ru(II)-bipyridine Complexes with Cyclometalated Ancillary Ligands: The Excited State Spin-Orbit Coupling Origin of Variations in Emission Efficiencies. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 9431–9449. 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chábera P.; Liu Y.; Prakash O.; Thyrhaug E.; Nahhas A. E.; Honarfar A.; Essén S.; Fredin L. A.; Harlang T. C. B.; Kjær K. S.; et al. A low-spin Fe(iii) complex with 100-ps ligand-to-metal charge transfer photoluminescence. Nature 2017, 543, 695. 10.1038/nature21430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisaun J.; Laramée-Milette B.; Beckwith J. S.; Bierwagen J.; Hanan G. S.; Reber C.; Hauser A.; Moucheron C. Two RuII Linkage Isomers with Distinctly Different Charge Transfer Photophysics. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 3677–3689. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley T. C.; Troian-Gautier L.; Brennaman M. K.; Meyer G. J. Excited-State Decay Pathways of Tris(bidentate) Cyclometalated Ruthenium(II) Compounds. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 13579–13592. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby G. A. Spectroscopic investigations of excited states of transition-metal complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 1975, 8, 231–238. 10.1021/ar50091a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.-X.; Mak E. C.-L.; Lo K. K.-W. Photofunctional transition metal complexes as cellular probes, bioimaging reagents and phototherapeutics. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 4553–4579. 10.1039/D1QI00931A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Cibian M.; Call A.; Yamauchi K.; Sakai K. Photochemical CO2 Reduction Driven by Water-Soluble Copper(I) Photosensitizer with the Catalysis Accelerated by Multi-Electron Chargeable Cobalt Porphyrin. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 11263–11273. 10.1021/acscatal.9b04023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierri A. E.; Muizzi D. A.; Ostrowski A. D.; Ford P. C.. Photo-Controlled Release of NO and CO with Inorganic and Organometallic Complexes. In Luminescent and Photoactive Transition Metal Complexes as Biomolecular Probes and Cellular Reagents; Lo K. K.-W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2015; pp 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Look E. G.; Gafney H. D. Photocatalyzed Conversion of CO2 to CH4: An Excited-State Acid–Base Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 12268–12279. 10.1021/jp401812k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horváth O. Photochemistry of copper(I) complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1994, 135-136, 303–324. 10.1016/0010-8545(94)80071-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cossairt B. M.; Piro N. A.; Cummins C. C. Early-Transition-Metal-Mediated Activation and Transformation of White Phosphorus. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4164–4177. 10.1021/cr9003709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossairt B. M. Shining Light on Indium Phosphide Quantum Dots: Understanding the Interplay among Precursor Conversion, Nucleation, and Growth. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 7181–7189. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elwell C. E.; Gagnon N. L.; Neisen B. D.; Dhar D.; Spaeth A. D.; Yee G. M.; Tolman W. B. Copper–Oxygen Complexes Revisited: Structures, Spectroscopy, and Reactivity. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2059–2107. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie L. K.; Bryant H. E.; Weinstein J. A. Transition metal complexes as photosensitisers in one- and two-photon photodynamic therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 379, 2–29. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A.; Yadav R.; White J. K.; Herroon M. K.; Callahan B. P.; Podgorski I.; Turro C.; Scott E. E.; Kodanko J. J. Illuminating cytochrome P450 binding: Ru(ii)-caged inhibitors of CYP17A1. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 3673–3676. 10.1039/C7CC01459G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.; Mosquera-Vazquez S.; Lawson Daku L. M.; Guénée L.; Goodwin H. A.; Vauthey E.; Hauser A. Experimental Evidence of Ultrafast Quenching of the 3MLCT Luminescence in Ruthenium(II) Tris-bipyridyl Complexes via a 3dd State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13660–13663. 10.1021/ja407225t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu F.; Lamb R. W.; Cameron C. G.; Park S.; Oladipupo O.; Gray J. L.; Xu Y.; Cole H. D.; Bonizzoni M.; Kim Y.; et al. Singlet Oxygen Formation vs Photodissociation for Light-Responsive Protic Ruthenium Anticancer Compounds: The Oxygenated Substituent Determines Which Pathway Dominates. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 2138–2148. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll J. D.; Albani B. A.; Turro C. New Ru(II) Complexes for Dual Photoreactivity: Ligand Exchange and 1O2 Generation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2280–2287. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby G. A.; Demas J. N. Quantum efficiencies of transition-metal complexes. I. d-d Luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 7262–7270. 10.1021/ja00728a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby G. A.; Demas J. N. Quantum efficiencies on transition metal complexes. II. Charge-transfer luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2841–2847. 10.1021/ja00741a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan R. W.; Crosby G. A. Symmetry assignments of the lowest CT excited states of ruthenium (II) complexes via a proposed electronic coupling model. J. Chem. Phys. 1973, 59, 3468–3476. 10.1063/1.1680504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedzki D. M. Photophysical properties of N719 and Z907 dyes, benchmark sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells, at room and low temperature. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 6182–6189. 10.1039/D0CP06629J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grätzel M. Dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2003, 4, 145–153. 10.1016/S1389-5567(03)00026-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sainuddin T.; McCain J.; Pinto M.; Yin H.; Gibson J.; Hetu M.; McFarland S. A. Organometallic Ru(II) Photosensitizers Derived from π-Expansive Cyclometalating Ligands: Surprising Theranostic PDT Effects. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 83–95. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindell M.; Gurgul I.; Janczy-Cempa E.; Gajda-Morszewski P.; Mazuryk O. Moving Ru polypyridyl complexes beyond cytotoxic activity towards metastasis inhibition. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 226, 111652 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manbeck G. F.; Fujita E.; Brewer K. J. Tetra- and Heptametallic Ru(II),Rh(III) Supramolecular Hydrogen Production Photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7843–7854. 10.1021/jacs.7b02142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga M.-a.; Ali M. M.; Koseki S.; Fujimoto K.; Yoshimura A.; Nozaki K.; Ohno T.; Nakajima K.; Stufkens D. J. Proton-Induced Tuning of Electrochemical and Photophysical Properties in Mononuclear and Dinuclear Ruthenium Complexes Containing 2,2′-Bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)–4,4′-bipyridine: Synthesis, Molecular Structure, and Mixed-Valence State and Excited-State Properties. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 3335–3347. 10.1021/ic950083y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrella F.; Petrone A.; Rega N. Direct observation of the solvent organization and nuclear vibrations of [Ru(dcbpy)2(NCS)2]4–, [dcbpy = (4,4′-dicarboxy-2,2′-bipyridine)], via ab initio molecular dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 22885–22896. 10.1039/D1CP03151A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrella F.; Li X.; Petrone A.; Rega N. Nature of the Ultrafast Interligands Electron Transfers in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. JACS Au 2023, 3, 70–79. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrella F.; Petrone A.; Rega N. Understanding Charge Dynamics in Dense Electronic Manifolds in Complex Environments. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 626–639. 10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid L.; Kerzig C.; Prescimone A.; Wenger O. S. Photostable Ruthenium(II) Isocyanoborato Luminophores and Their Use in Energy Transfer and Photoredox Catalysis. JACS Au 2021, 1, 819–832. 10.1021/jacsau.1c00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann M.; Müller C.; Cullen A. A.; Brandon M. P.; Dietzek B.; Pryce M. T. Photophysics of Ruthenium(II) Complexes with Thiazole π-Extended Dipyridophenazine Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 760–773. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna S.; Mansour N.; Audi H.; Bodman-Smith K.; Mroueh M. A.; Taleb R. I.; Daher C. F.; Khnayzer R. S. Enhanced cellular uptake and photochemotherapeutic potential of a lipophilic strained Ru(ii) polypyridyl complex. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 17254–17265. 10.1039/C9RA02615K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrabaugh T. N.; Collins K. A.; Xue C.; White J. K.; Kodanko J. J.; Turro C. New Ru(ii) complex for dual photochemotherapy: release of cathepsin K inhibitor and 1O2 production. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 11851–11858. 10.1039/C8DT00876K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifshits L. M.; Roque Iii J. A.; Konda P.; Monro S.; Cole H. D.; von Dohlen D.; Kim S.; Deep G.; Thummel R. P.; Cameron C. G.; et al. Near-infrared absorbing Ru(ii) complexes act as immunoprotective photodynamic therapy (PDT) agents against aggressive melanoma. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 11740–11762. 10.1039/D0SC03875J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karges J.; Heinemann F.; Jakubaszek M.; Maschietto F.; Subecz C.; Dotou M.; Vinck R.; Blacque O.; Tharaud M.; Goud B.; et al. Rationally Designed Long-Wavelength Absorbing Ru(II) Polypyridyl Complexes as Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6578–6587. 10.1021/jacs.9b13620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubikova E.; Chen W.; Dattelbaum D. M.; Rein F. N.; Rocha R. C.; Martin R. L.; Batista E. R. Electronic Structure and Spectroscopy of [Ru(tpy)2]2+, [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(H2O)]2+, and [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(Cl)]+. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 10720–10725. 10.1021/ic901477m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone M. L.; Crosby G. A. Charge-transfer luminescence from ruthenium(II) complexes containing tridentate ligands. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1981, 79, 169–173. 10.1016/0009-2614(81)85312-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suen H. F.; Wilson S. W.; Pomerantz M.; Walsh J. L. Photosubstitution reactions of terpyridine complexes of ruthenium(II). Inorg. Chem. 1989, 28, 786–791. 10.1021/ic00303a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp M. T.; Shevchenko N.; Hanan G. S.; Kurth D. G. Enhancing the photophysical properties of Ru(II) complexes by specific design of tridentate ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214127 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toupin N.; Steinke S. J.; Nadella S.; Li A.; Rohrabaugh T. N. Jr; Samuels E. R.; Turro C.; Sevrioukova I. F.; Kodanko J. J. Photosensitive Ru(II) Complexes as Inhibitors of the Major Human Drug Metabolizing Enzyme CYP3A4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9191–9205. 10.1021/jacs.1c04155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt J. T.; Vallett P. J.; Damrauer N. H. Dynamics of the 3MLCT in Ru(II) Terpyridyl Complexes Probed by Ultrafast Spectroscopy: Evidence of Excited-State Equilibration and Interligand Electron Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 11536–11547. 10.1021/jp308091t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juris A.; Balzani V.; Barigelletti F.; Campagna S.; Belser P.; von Zelewsky A. Ru(II) polypyridine complexes: photophysics, photochemistry, eletrochemistry, and chemiluminescence. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1988, 84, 85–277. 10.1016/0010-8545(88)80032-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowska M.; Rodziewicz P.; Brus D. M.; Breczko J.; Brzezinski K. Bis(2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine)ruthenium(II) bis(perchlorate) hemihydrate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E 2012, 68, m1414–m1415. 10.1107/S1600536812043917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker C. R.; Gushurst A. K. I.; McMillin D. R. Phenyl substituents and excited-state lifetimes in ruthenium(II) terpyridyls. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 538–541. 10.1021/ic00003a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. C.; Nagle J. K.; Meyer T. J.; Whitten D. G. Electron transfer quenching of nonemitting excited states of Ru(TPP)(py)2 and Ru(trpy)22+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 4773–4778. 10.1021/ja00483a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage J. P.; Collin J. P.; Chambron J. C.; Guillerez S.; Coudret C.; Balzani V.; Barigelletti F.; De Cola L.; Flamigni L. Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) Bis(terpyridine) Complexes in Covalently-Linked Multicomponent Systems: Synthesis, Electrochemical Behavior, Absorption Spectra, and Photochemical and Photophysical Properties. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 993–1019. 10.1021/cr00028a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu I. C.; Tsai C. N.; Lin Y.-T.; Hung S.-Y.; Chao V. P. S.; Yin C.-W.; Luo D.-W.; Chen H.-Y.; Endicott J. F.; Chen Y. J. Near-IR Charge-Transfer Emission at 77 K and Density Functional Theory Modeling of Ruthenium(II)-Dipyrrinato Chromophores: High Phosphorescence Efficiency of the Emitting State Related to Spin–Orbit Coupling Mediation of Intensity from Numerous Low-Energy Singlet Excited States. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 903–919. 10.1021/acs.jpca.0c05910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R. A.; Tsai C. N.; Mazumder S.; Lu I. C.; Lord R. L.; Schlegel H. B.; Chen Y. J.; Endicott J. F. Energy Dependence of the Ruthenium(II)-Bipyridine Metal-to-Ligand-Charge-Transfer Excited State Radiative Lifetimes: Effects of ππ*(bipyridine) Mixing. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 7393–7406. 10.1021/jp510949x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B. P.; Calvert J. M.; Meyer T. J. Cis-trans isomerism in (trpy)(PPh3)RuC12. Comparisons between the chemical and physical properties of a cis-trans isomeric pair. Inorg. Chem. 1980, 19, 1404–1407. 10.1021/ic50207a066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R.; Binkley J. S.; Seeger R.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XX. A Basis Set for Correlated Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650. 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33, 8822–8824. 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Wang Y. Generalized Gradient Approximation for the Exchange-Correlation Hole of a ManyElectron System. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 16533–16539. 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.16533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. Jr.; Hay P. J.. Modern Theoretical Chemistry; Schaefer H. F., III, Ed.; Plenum: New York, 1976; Vol. 3, pp 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Igel-Mann G.; Stoll H.; Preuss H. Pseudopotentials for Main Group Elements (IIIa through VIIa). Mol. Phys. 1988, 65, 1321–1328. 10.1080/00268978800101811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrae D.; Häußermann U.; Dolg M.; Stoll H.; Preuß H. Energy-Adjustedab Initio Pseudopotentials for the Second and Third Row Transition Elements. Theor. Chim. Acta 1990, 77, 123–141. 10.1007/BF01114537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; et al. Gaussian 16, revision C.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Miertuš S.; Scrocco E.; Tomasi J. Electrostatic Interaction of a Solute with a Continuum. A Direct Utilizaion of AB Initio Molecular Potentials for the Prevision of Solvent Effects. Chem. Phys. 1981, 55, 117–129. 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3093. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalmani G.; Frisch M. J.; Mennucci B.; Tomasi J.; Cammi R.; Barone V. Geometries and Properties of Excited States in the Gas Phase and in Solution: Theory and Application of a Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory Polarizable Continuum Model. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 094107 10.1063/1.2173258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. L. Natural Transition Orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4775–4777. 10.1063/1.1558471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J.; Devlin F. J.; Chabalowski C. F.; Frisch M. J. Ab Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular Dichroism Spectra Using Density Functional Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. A 1994, 98, 11623–11627. 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai T.; Tew D. P.; Handy N. C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. 10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tawada Y.; Tsuneda T.; Yanagisawa S.; Yanai T.; Hirao K. A long-range-corrected time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 8425–8433. 10.1063/1.1688752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. N.; Mazumder S.; Zhang X. Z.; Schlegel H. B.; Chen Y. J.; Endicott J. F. Metal-to-Ligand Charge-Transfer Emissions of Ruthenium(II) Pentaammine Complexes with Monodentate Aromatic Acceptor Ligands and Distortion Patterns of their Lowest Energy Triplet Excited States. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 8495–8508. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-J.; Xie P.; Heeg M. J.; Endicott J. F. Influence of the “Innocent” Ligands on the MLCT Excited-State Behavior of Mono(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) Complexes: A Comparison of X-ray Structures and 77 K Luminescence Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 6282–6297. 10.1021/ic0602547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie P.; Chen Y.-J.; Uddin M. J.; Endicott J. F. The Characterization of the High-Frequency Vibronic Contributions to the 77 K Emission Spectra of Ruthenium–Am(m)ine–Bipyridyl Complexes, Their Attenuation with Decreasing Energy Gaps, and the Implications of Strong Electronic Coupling for Inverted-Region Electron Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 4671–4689. 10.1021/jp050263l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruszewski K.; Bajdor K.; Strommen D. P.; Kincaid J. R. Position-Dependent Deuteration Effects on the Nonradiative Decay of the 3MLCT State of Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium (II). An Experimental Evaluation of Radiationless Transition Theory. J. Phys. Chem. B 1995, 99, 6286–6293. 10.1021/j100017a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-J.; Xie P.; Endicott J. F.; Odongo O. S. Probes of the Metal-to-Ligand Charge-Transfer Excited States in Ruthenium-Am(m)ine-Bipyridine Complexes: The Effects of NH/ND and CH/CD Isotopic Substitution on the 77 K Luminescence. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7970–7981. 10.1021/jp055561x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster L. S. Thermal relaxation in excited electronic states of d3 and d6 metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 227, 59–92. 10.1016/S0010-8545(01)00458-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Englman R.; Jortner J. The energy gap law for radiationless transitions in large molecules. Mol. Phys. 1970, 18, 145–164. 10.1080/00268977000100171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T. J. Excited-State Electron Transfer. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 1983, 30, 389–440. 10.1002/9780470166314.ch8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. B. Resonance Raman Intensities and Charge-Transfer Reorganization Energies. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 911–926. 10.1021/cr950249c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupp J. T.; Williams R. D. Using Resonance Raman Spectroscopy To Examine Vibrational Barriers to Electron Transfer and Electronic Delocalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 808–817. 10.1021/ar9602720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.