Abstract

Curcumin has been credited with a wide spectrum of pharmacological properties for the prevention and treatment of several chronic diseases such as arthritis, autoimmune diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hemoglobinopathies, hypertension, infectious diseases, inflammation, metabolic syndrome, neurological diseases, obesity, and skin diseases. However, due to its weak solubility and bioavailability, it has limited potential as an oral medication. Numerous factors including low water solubility, poor intestinal permeability, instability at alkaline pH, and fast metabolism contribute to curcumin’s limited oral bioavailability. In order to improve its oral bioavailability, different formulation techniques such as coadministration with piperine, incorporation into micelles, micro/nanoemulsions, nanoparticles, liposomes, solid dispersions, spray drying, and noncovalent complex formation with galactomannosides have been investigated with in vitro cell culture models, in vivo animal models, and humans. In the current study, we extensively reviewed clinical trials on various generations of curcumin formulations and their safety and efficacy in the treatment of many diseases. We also summarized the dose, duration, and mechanism of action of these formulations. We have also critically reviewed the advantages and limitations of each of these formulations compared to various placebo and/or available standard care therapies for these ailments. The highlighted integrative concept embodied in the development of next-generation formulations helps to minimize bioavailability and safety issues with least or no adverse side effects and the provisional new dimensions presented in this direction may add value in the prevention and cure of complex chronic diseases.

1. Introduction

Chronic diseases including autoimmune diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hepatocellular, neurological, and renal diseases have persistent high incidence and fatality rates worldwide.1,2 Finding feasible treatment strategies are challenging due to the high prevalence of these diseases and the involvement of several pathways in their development, including JAK/STAT3, JNK, NF-κB, MEK/ERK, p38/MAPK, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR, etc.1−10 Therefore, classical monotarget therapies are insufficient to treat these diseases. Besides, the cost of contemporary pharmaceuticals is high, and have several unfavorable side effects.7,10,11 Indeed, there is an increasing need for the development of safer, effective, multitargeted, and cost-effective therapeutic regimens to replace the current harmful and ineffective treatment approaches. A growing body of preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that natural substances derived from diverse plants are potential therapeutic candidates against a wide range of fatal chronic conditions, and their alternative formulations can be employed to boost the bioavailabilities of these substances.2,7,10,12−14

The perennial herb turmeric, Curcuma longa Linn. belongs to the Zingiberaceae family, is indigenous to South Asia’s tropical areas. The rhizomes of this plant have been used for centuries as a remedy for several diseases in the Indian (Ayurveda) and Chinese Medicinal Systems.15−17 Curcumin is a bioactive phytochemical derived from this rhizome. It has traditionally been used as a spice, food preservative, and coloring ingredient.15,18 The chemical name for curcumin is diferuloylmethane (C21H20O6) and the IUPAC name is (1E-6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy phenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione with a molecular weight of 368.37 g/mol and melting point of 183 °C. The two aryl rings in curcumin are symmetrically connected to a β-diketone moiety by ortho-methoxy phenolic groups.17−21 A pH-dependent keto-enol tautomerism appears in curcumin wherein the stable enol form predominates in an alkaline medium and a keto form in acidic and neutral conditions.17 In addition, curcumin’s color varies depending on the pH level, yielding a brilliant yellow solution between 2.5 and 7.0, and turning to dark red when the pH rises over that level.17,20

Currently, there are several curcumin-based products available in the market, including pills, ointments, capsules, and cosmetics.16,22−24 Turmeric and curcumin have been the established remedies for various ailments, primarily as antiatherosclerotic, antibacterial, anticancerous, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antithrombotic, and antiviral agents.22,25,26 Additionally, a comprehensive analysis of the literature identified curcumin as one of the excellent natural compounds that exhibit analgesic, antirheumatic effects, hypoglycemia, hypolipidemia, hepatoprotective, nephron protective, pulmonoprotective, and cardioprotective activities.18,21,27−35 Besides, in vitro studies have shown that curcumin modulates several cell signaling pathways, upregulates p53, p21, and p27, downregulates cell survival gene products, and induces apoptosis.15,36−39 Numerous clinical studies have demonstrated its outstanding safety, tolerability, and effectiveness even at higher oral dosages, and is currently being sold as a dietary supplement in several countries across the world.27,28,40,41 Curcumin has not yet been authorized as a drug despite its excellent efficacy and safety, and a key issue for this is the relative bioavailability of curcumin. Research over the last three decades has revealed the poor gut absorption, rapid metabolism, and systemic elimination of curcumin that significantly restricts its bioavailability.18,23,42−44 Moreover, curcumin is a hydrophobic molecule with a logP of ∼3.2 (octanol-water partition coefficient), making it practically water-insoluble (with a water solubility of only 30 nM).21,45−47 Curcumin activity has a reported half-life of 10 min in a phosphate buffer of pH 7.4 which further limits its clinical use.46,47 Even after consuming high amounts of conventional curcumin, very low levels of plasma curcumin were detected. Hence, the overarching goal of all strategies is to increase curcumin’s solubility and bioavailability.48−52 Numerous approaches have been used to improve the solubility and subsequently the bioavailability of curcumin including curcumin-piperine complex, curcumin nanoparticles or nanomicelles, liposomal curcumin, phospholipidated curcumin, and phytosomal curcumin complex.18,42,44,47,53,54 Therefore, in the current review, we provide an overview of the bioavailability, safety, tolerability, and efficacy of various curcumin formulations in clinical trials. We have extensively reviewed the completed clinical trials on curcumin formulations of different generations and highlighted their efficacy in treating several chronic diseases. Significant variations in research design, volunteer race, dose, duration, and route of administration were noted. Moreover, we discussed the advantages and limitations of these formulations and highlighted the future perspectives from the podium to clinical practice.

2. Bioavailability of Conventional Curcumin

The major findings from curcumin research are the observation of noticeably low serum levels, limited tissue distribution, rapid metabolism, inactive metabolite formation, and rapid clearance/elimination from the body.18,42,47,48,55 Several studies have shown that administration of a large amount of pure curcumin yielded only a trace amount of serum levels of curcumin in rats owing to its poor absorption from the gut.55−60 Curcumin administered orally at 2 g/kg to rats showed a maximum serum concentration of only 1.35 ± 0.23 μg/mL at 0.83 h, whereas the same dosage showed undetectable or extremely low serum levels, i.e., 0.006 ± 0.005 μg/mL at 1 h.55 Similarly, in another clinical trial, it was shown that administration of 3.6 g of curcumin by the oral route generated serum levels of only 11.1 nmol/L after 1 h.51 More recently, Yang and colleagues demonstrated that curcumin given intravenously (10 mg/kg) produced a maximum serum level of 0.36 ± 0.05 g/mL, whereas a 50-fold increase in dosage of oral supplement produced only a maximum serum level of 0.06 ± 0.01 g/mL in rats.56 Besides, following oral treatment of 400 mg of curcumin in rats, Ravindranath et al. demonstrated that only residues of the unmodified substance were discovered in the liver and kidney.59 This study also showed that 90% of curcumin was noted in the stomach and small intestine at 30 min while only 1% of curcumin was present after 24 h.59 Another study revealed that administration of radiolabeled (tritium or H3) curcumin at 10, 80, and 400 mg doses resulted in the detection of a considerable amount of curcumin in tissues of rats administered with only 400 mg after 12 days.58 Also, the percentage of absorbed curcumin remained constant irrespective of the dosage indicating the dose-independent limitations to bioavailability in these animals.58 Similarly, supplementation of 450–3600 mg of curcumin daily for a week before surgery to patients with colorectal cancer metastases to liver showed no curcumin in their liver tissues.61 In phase II clinical trial on patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, an oral dose of 8 g/day curcumin resulted in only 22–41 ng/mL of plasma concentration.62 Further, orally given curcumin (2 g/kg) to rats had an absorption half-life of 0.31 ± 0.07 and elimination half-life of 1.7 ± 0.58 h, albeit in humans, the same dose did not enable the measurement of these shelf life values since most of the levels were below the detection limit at almost all the periods.55

These studies indicated that the method of administration (whether oral or intravenous) affects the serum levels of curcumin and further suggest that the serum achievable concentrations of curcumin in humans and rats are not exactly comparable. Hence, it is not only imperative to develop bioavailable curcumin but also equally important to find the safety and efficacy of these formulations in humans.

3. Methodology

A literature search was carried out using “curcumin and clinical trials” in two different databases, Pubmed and Scopus, until June 2022. Around 458 articles appeared in PubMed and 3622 articles appeared in Scopus for the mentioned keyword. The studies that appeared were analyzed thoroughly for the mentioned keywords.

The inclusion criteria applied to select the relevant studies were (a) clinical studies that have used various generations of curcumin formulation; (b) studies on human subjects (both healthy and diseased); (c) full-text manuscripts in English. The exclusion criteria were (a) preclinical studies; (b) studies on the pure form of curcumin; (c) full-text not in English; (d) in silico studies; (e) conference abstracts; (f) review articles; (g) meta-analysis; and (h) case reports. All the relevant articles as per these criteria are included in the table, figures, and text.

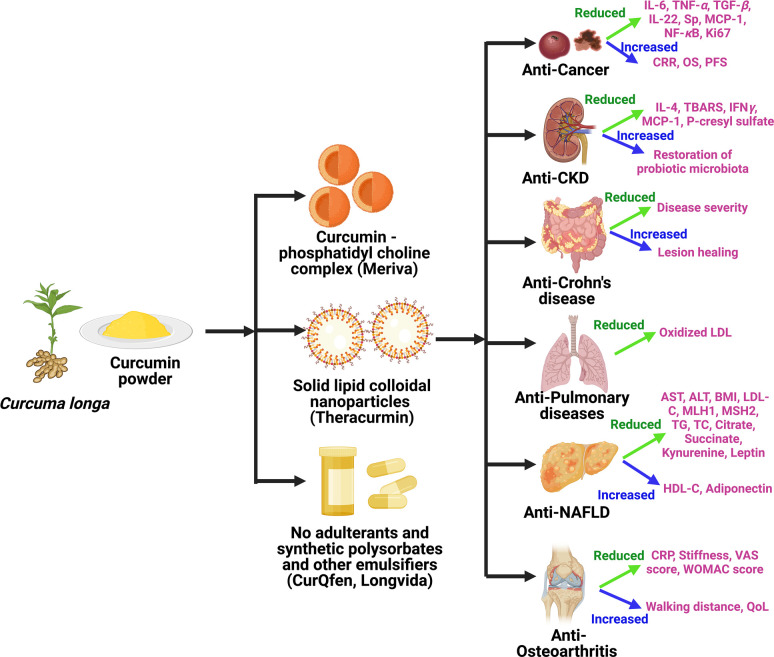

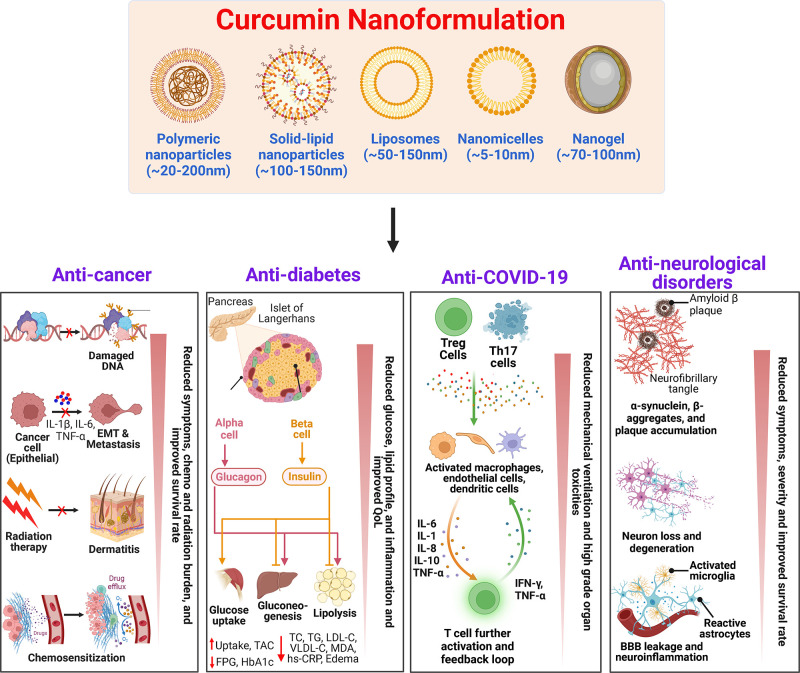

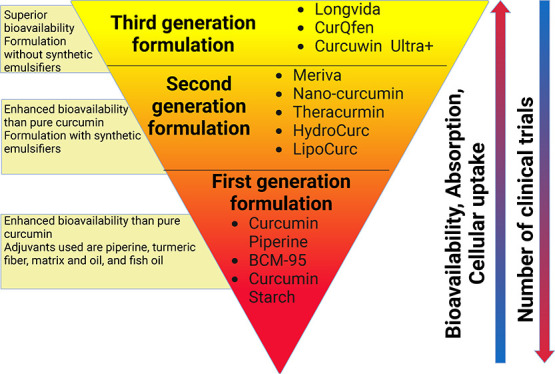

4. Curcumin Formulations

The straightforward ways to address the limitation(s) of curcumin are to enhance its bioavailability, shield it from oxidation and metabolism, and increase its ability to target diseased tissues and/or organs.18,47 One of the main strategies for increasing curcumin’s bioavailability is to utilize adjuvants that can inhibit or delay its metabolism.18,63 Other intriguing innovative formulations that appear to offer longer circulation, improved permeability, and resistance to metabolic processes include liposomes, micelles, nanoparticles, and phospholipid complexes.18,42,64 These bioavailable or bioenhanced formulations of curcumin are generally categorized into three different formulations. The classic example of first-generation formulation includes the use of significant amounts of adjuvants such as piperine from black pepper, turmeric oils, or any other natural compounds that were included to inhibit the essential detoxification enzymes such as hepatic aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase, cytochrome P450, mixed-function oxygenases, and UDP-glucuronyltransferase.18,63,65,66 The first-generation formulation enhances the absorption time of curcumin by inhibiting or delaying its metabolism. The formulations such as curcumin–piperine, C3 complex–piperine (C3 complex/bioperine), turmeric fiber or oil with curcumin, BCM-95, and Cureit belong to the first-generation category.44 In the second-generation, emulsifiers such as carbohydrate complexes, polyethoxylated hydrogenated castor oil, lipid complexes, phospholipid complexes, polysorbates, water-dispersible nanopreparations, and spray drying were used to increase the solubility of curcumin. These included BioCurc, Cavacurcmin, CurcuWIN, Hydrocurc, Meriva, Nanocurcumin, Novasol, Theracurmin, and Turmipure Gold.44 Although increases in plasma curcuminoids levels occur primarily through their conjugated metabolites (glucuronides and sulfates), numerous studies have shown that these conjugated metabolites lack biologically significant effects because of the large size, quick renal elimination, limited membrane, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability.44,67,68 For this reason, delivering curcumin in its free form (naturally unconjugated) is essential to maximize its therapeutic effects. The third-generation curcumin formulations including Longvida and CurQfen have solved the issue of “free” curcuminoids bioavailability, membrane permeability, and cellular uptake without the use of artificial emulsifiers like polysorbates.44 This section details the clinical safety and efficacy of all three generations of curcumin formulations. Different formulations and their composition are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Composition of Various Curcumin Formulations That Are Tested Clinicallya.

| curcumin formulation | composition | ref |

|---|---|---|

| First-Generation Formulation | ||

| active ingredients formulated as soft gel capsules | fish oil 250 mg, phosphatidyl choline concentrated sunflower oil 150 mg, silymarin 75 mg, choline bitartrate 35 mg, curcumin 35 mg, d-α-tocopherol 10 mg for a total of 830 mg | (122) |

| ArtemiC oral spray (1 mL) | 6 mg artemisinin, 20 mg curcumin, 15 mg frankincense, 60 mg vitamin C | (127) |

| BCM-95 | Curcuma longa extract with essential oils from turmeric rhizome, rice flour, vegetable cellulose, vegetable stearate, silica | (116) |

| bioactive capsules | rutin (500 mg), 1.5 g fish oil (18% EPA and 7% DHA), 500 mg curcumin (95% curcuminoids) | (128) |

| C3 complex bioperine | curcuminoid extract containing curcumin, desmethoxycurcumin, bisdesmethoxycurcumin and piperine formulation | (51,61) |

| CartiJoint Forte | curcumin (BCM-95), chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride | (123) |

| Coltect tablet | curcumin 500 mg, green tea 250 mg, and selenium 100 μg | (130) |

| CUC-1 | 300 mg solution of curcumin | (129) |

| CuraMed | 552–578 mg of BCM-95 extracted in ethanol 99% (v/v) and 100% ethyl acetate +49–52 mg volatile oil from C. longa containing 22–23.4 mg aromatic turmerone + inactive excipients (120–140 mg) including phosphatidyl choline, medium chain TGs, glycerol, gelatin, yellow beeswax | (124) |

| Curamin | 350 mg BCM-95 + 150 mg of Boswellia serrata Roxb. ex Colebrgum resin extract corresponding to 75% boswellic acids and 10% 3-O-acetyl-11-keto-boswellic acid | (124) |

| Curcugreen | Dry rhizomes of turmeric extracted with ethyl acetate to form turmeric oleoresin, precipitated and combined with turmeric essential oil | (126) |

| Curcumall | A tincture of curcumin C3 95%, turmeric and ginger dissolved in glycerin and 0.4% alcohol | (131) |

| curcumin chitosan mouthwash | Purified curcuminoid powder 0.1 g (79:19:1 of curcumin/dimethoxycurcumin/bisdemethoxycurcumin) dissolved in 40 mL PEG, 25 mL of 2% low molecular weight chitosan | (87) |

| curcumin capsules from Theravalues Corporation, Tokyo, Japan | 10% curcumin, 2% other curcuminoids, 3.2% gum ghatti, 0.27% citric acid, 54.53% dextrin, and 30% maltose | (133) |

| curcumin forte | 95% curcumin plus 5% piperine | (86) |

| curcuminoid turmeric matrix formulation | 50% Total curcuminoids (41.2% curcumin, 7.3% desmethoxycurcumin, 1.5% bisdemethoxycurcumin), 3% essential oil, 2% protein, 40% total carbohydrate | (138) |

| curcuminoid turmeric oil formulation | 440 mg curcuminoid (347 mg curcumin, 84 mg desmethoxycurcumin, 9 mg bisdemethoxycurcumin), 38 mg of turmeric oil | (139,140) |

| Cureit/Acumin | 46.5% Total curcuminoids (36% curcumin, 9.0% desmethoxycurcumin, 1.5% bisdemethoxycurcumin), 43% total carbohydrates, 5% fiber, 2.4% proteins, 3.2% volatile oil containing aromatic turmerone, dihydroturmerone, turmeronol, curdione, bisacurone | (135) |

| Infla-Kine | Proprietary blend of Lactobacillus fermentum extract, burdock seed, zinc, lipoic acid, papaya enzyme, BCM-95 | (144) |

| Killox | 190 mg curcuminoids, 20 mg resveratrol, 100 mg NAC, 6 mg zinc with the formulation of enterosoma technology to obtain increased bioavailability | (146) |

| LCD capsule | Soft gel capsules containing lutein (20 mg), curcumin (200 mg total curcuminoids), zeaxanthin (4 mg) from marigold flower extract, algal source vitamin D3 (600 IU), medium chain triglyceride oil, linseed oil, olive oil, sunflower lecithin, tocopherol and thyme oil | (147) |

| natural product capsule by Vitacost | Each 500 mg capsule contain 150 mg curcumin, 75 mg resveratrol, 150 mg epigalloatechin-3-gallate, 125 mg soy isoflavone | (148) |

| Nutrafol women’s capsules | A proprietary blend of clinically tested and bio-optimized phytoactive extracts, vitamins, minerals and botanicals; major ingredients include standardized extracts of Ashwagandha, curcumin, piperine, capsiacin, hydrolyzed marine collagen, hyaluronic acid, organic kelp, saw palmetto, tocotrienol rich tocotrienol/tocopherol complex | (153) |

| PureVida | 460 mg of fish oil (DHA and EPA), 125 mg of Hytolive powder (12.5 mg of hydroxytyrosol), 50 mg of curcumin extract (47.5 mg of curcuminoids) | (150) |

| Reglicem | Chromium picolinate 100 μcg Cr, 200 mg curcumin dry extract, 200 mg berberine dry extract, 300 mg inositol, 40 mg banaba dry extract with 1% corosolic acid, silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, dicalcium phosphate, microcrystalline cellulose | (151) |

| Turmix tablet | 300 mg curcumin plus 5 mg piperine | (113) |

| Turmix mouthwash | C. longa dry extract 0.1% w/v standardized to 95% curcumin (tetrahydrocurcumin) along with thymol, eucalyptol, clove oil, mentha oil, tea tree oil | (113) |

| Volatile oil formulation of curcumin | 85.9% curcuminoids (70.2% curcumin, 14.3% demethoxycurcumin, 1.4% bisdemethoxycurcumin), 7–9% essential oil naturally present in turmeric | (135) |

| WEC (hot water extract of curcumin) | C. longa rhizomes were crushed and incubated with hot water. The supernatant was concentrated, mixed with dextrin and spray-dried to obtain powder. The powder was later dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide | (152) |

| Second-Generation Formulation | ||

| Actbiome | curcumin and asafetida complex was incorporated on to turmeric dietary fiber by spray drying process with complete natural matrix via polar–nonpolar sandwich technology | (154) |

| Algocur (Meriva formulation) | each tablet contains 1 g of Meriva | (199) |

| BioCurc/CLDM | 85% curcumin, 13% demethoxycurcumin, 2% bisdemethoxycurcumin, lauryl macrogol-32 glycerides, polysorbate-20, dl-α-tocopherol, hydroxyprolyl cellulose | (155) |

| CartiJoint Forte | Chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride, BCM-95 | |

| CHC (curcumin formulation with hydrophilic carrier) | Novel water-soluble formulation containing turmeric extract 20–28%, a hydrophilic carrier 63–75%, cellulose derivatives 10–40%, natural antioxidants 1–3% | (157) |

| CSL | curcumin/soy lecithin/microcrystalline cellulose in the ratio of 1:2:2 | (137) |

| curcumin nanomicelle gel from Sina Pharmaceuticals | 1% curcumin nanomicelle gel | (264) |

| curcuminoid cream from GPO Thailand | Tetrahydrocurcuminoid in phosphatidyl choline liposomes | (202) |

| curcuminoid micelles | 7% native curcumin powder containing 82% curcumin, 16% demethoxycurcumin and 2% bisdemethoxycurcumin and 93% Tween-80 filled in Licaps; finally, each capsule contained 20.1 mg curcumin, 3.9 mg demethoxycurcumin, and 0.5 mg bisdemethoxycurcumin | (160,161,163) |

| Curserin | 200 mg curcumin, 120 mg phosphatidylserine, 480 mg phosphatidylcholine and 8 mg piperine from Piper nigrum L. dry extract | (159) |

| CW8 | curcumin in complex with γ-cyclodextrin | (137) |

| FLAVOMEGA | fructose, phospholipidic curcumin, acetyl carnitine-HCL, ascorbic acid, flavoring, coenzyme Q10, Skullcap, Baicalin, green tea catechins, antiagglomerant, acesulfame potassium, sucralose | (164) |

| Flexofytol | bio-optimized curcumin 42 mg mixed with polysorbate Tween-80 | (165,166) |

| HydroCurc | 80% curcumin, 17% demethoxycurcumin, 3% bisdemethoxycurcumin, entrapped in LipiSperse delivery system | (167) |

| Ialuril soft gel tablets | Oral food integrator containing curcumin, quercetin, hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate | (145) |

| Meriva | curcumin complexed with phosphatidyl choline | (179) |

| NE65 | Lipoid S LPC65 (5% w/w), olive oil (20% w/w), potassium sorbate (0.1% w/w) and distilled water | (200) |

| NLC65 | Lipoid S LPC65 (5% w/w), olive oil (2.22% w/w), precirol ATO5 (7.77% w/w) and distilled water | (200) |

| NLC80 | Lipoid S LPC80 (5% w/w), olive oil (2.22% w/w), precirol ATO5 (7.77% w/w) and distilled water | (200) |

| phospholipid curcumin formulation | 19.8% curcuminoids (16.1% curcumin, 3.2% demethoxycurcumin, 0.5% bisdemethoxycurcumin), 40% phospholipids, 40% microcrystalline cellulose | (135) |

| phospholipidated curcumin | ∼20% curcumin and soy phosphatidyl choline in 1:2 weight ratio, 2 parts of microcrystalline cellulose | (204) |

| theracurmin | curcumin dispersed in colloidal nanoparticles- Gum ghatti obtained from exudation of ghatti trees was dissolved in water and mixed with curcumin powder and glycerin, wet grinded and dispersed as colloidal nanoparticle by a high-pressure homogenizer | (282,283) |

| theracurmin beverage | Water, sugar syrup (high-fructose corn syrup, sugar), cinnamon extract, ginger, alanine, acidulant, Theracurmin, vitamin C, flavor, sweetner (licorice, sucralose), niacinamide, calcium pantothenate, vitamin B6, vitamin B2, vitamin B1, vitamin B12 | (286) |

| Third-Generation Formulation | ||

| curcumagalactomannosides | Novel oral delivery for of curcumin prepared using noncovalent complex formation between curcumin and fenugreek galactomannans | (301) |

| curcuRouge | Amorphous formulation of curcumin, modified starch, corn-starch containing 37 w/w% of curcumin | (297) |

| Curcuwin Ultra+ | 63–75% polyvinyl pyrrolidine, 10–40% cellulosic derivatives, 1–3% natural antioxidants, 20–28% turmeric extract | (47,304) |

| Longvida | curcumin in solid lipid formulation containing proprietary blend of vegetable derived stearic acid dextrin, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, soy lecithin, ascorbyl palmitate, silicon dioxide | (306,308) |

Abbreviation: CLDM, Curcumin liquid droplet micromicellar formulation; DHA, Docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, icosapentaenoic acid; HCl, Hydrogen chloride.

4.1. First-generation curcumin formulation

Early attempts to increase absorption of curcumin included the addition of turmeric oil (BCM-95; BioCurcumax; Curcugreen), a small amount of piperine (curcumin C3 complex) to stimulate the gastrointestinal system, prevent curcumin efflux and inhibit hepatic and intestinal glucuronidation, or as a turmeric oleoresin (Curcugen).18,44,55 All of these formulations have shown incremental improvement in curcumin absorption and efficacy clinically (Table 2, Figure 1). For instance, supplementation with curcumin/piperine (500 mg-2g/day curcumin plus 5–20 mg/day piperine) formulation resulted in a significant reduction in ubiquitin, muscle atrophy F box (MAFbx)/atrogin-1, chymotrypsin-like protease, interleukin 2 (IL-2), TNF-α, INF, IL-6, IL-10, and enhancement in bioavailability, safety, tolerability, and delayed onset of muscle soreness in healthy subjects without adverse side effects.55,69,70

Table 2. Effect of Curcumin Formulations on Various Human Diseasesa.

| curcumin formulation | disease/condition | no. of patients | duration | dose | outcome | adverse effect (if any) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation Formulation | |||||||

| active ingredients formulated as soft gel capsules | NAFLD | 126 | 3 months | 2 capsules/day | ↑cholesterol, ↑glucose, ↓AST | safe, well-tolerated, no adverse side effects | (122) |

| ArtemiC oral spray | COVID-19 | 50 | day 1 and day 2 | twice daily | ↑clinical improvement, ↑SpO2 normalization, ↓O2 supplementation, ↓fever, ↓hospital stay | no adverse side effects, safe, well-tolerated | (127) |

| BCM-95 | healthy volunteers | 11 | 2g | ↑bioavailability and retention time compared to curcumin–lecithin and piperine formulation | safe, no adverse side effects | (117) | |

| multiple myeloma | 33 | 28 days | 8 g/day | ↑overall remission, ↓NFκB, ↓TNF-α, ↓VEGF, ↓IL-6 | (118) | ||

| multiple sclerosis | 80 | 24 months | 1 g/day | ↓combined unique active lesions | no serious adverse side effects | (119) | |

| NAFLD | 50 | 12 weeks | 1.5g/day | ↑physical activity, ↓hepatic fibrosis, ↓TNF-α, ↓NF-κB, ↓AST, ↓ALT | safe, well-tolerated, no adverse side effects | (120) | |

| prediabetes | 84 | 90 days | 500 mg/day | ↑HDL, ↓BMI, ↓weight, ↓TC, ↓TG, ↓LDL, ↓ non-HDL-C | no serious adverse side effects | (121) | |

| bioactive capsule + WPI | age-related sarcopenia | 41 | 12 weeks | 7 capsules + 20 g | ↑knee extension strength, ↑gait speed | no serious adverse side effects | (128) |

| C3 complex + bioperine | healthy volunteers | 10 | 12 g + 60 mg | no significant effect | safe | (40) | |

| MetS | 117 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↓LDL-C, ↓non-HDL-C, ↓TC, ↓TG, ↓LPA, ↑HDL-C | safe, well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (92) | |

| 117 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↑SOD, ↓MDA, ↓CRP, ↓glucose, ↓HbA1c, ↓SBP, ↓DBP | safe | (93) | ||

| 117 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↓TNF-α, ↓TGF-β, ↓IL-6, ↓MCP-1 | safe, well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (94) | ||

| 117 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↑adiponectin, ↓leptin | well-tolerated | (95) | ||

| NAFLD | 70 | 12 weeks | 500 mg + 5 mg | ↑TIBC, ↓hematocrit, ↓ESR, ↓AST, ↓ALT, ↓ALP, ↓TC, ↓LDL-C, ↓iron, ↓Hb | no adverse side effects | (96) | |

| 55 | 8 weeks | 500 mg + 5 mg | ↓weight, ↓severity, ↓TNF-α, ↓MCP-1, ↓EGF | no serious adverse side effects | (97) | ||

| 55 | 8 weeks | 500 mg/day + 50 mg/day | no significant on PAB | no serious adverse side effects | (112) | ||

| obesity | 30 | 30 days | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↓TG | safe, well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effect | (98) | |

| 30 | 2 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↓PAB | (105) | |||

| 30 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↑Zn/Cu | (106) | |||

| 30 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↓IL-1β, ↓IL-4, ↓VEGF | (107) | |||

| osteoarthritis | 40 | 6 weeks | 1.5 g/day + 15 mg/day | ↑SOD, ↑GSH, ↓MDA, ↓oxidative stress | (91) | ||

| 53 | 6 weeks | 1.5 g/day + 15 mg/day | ↓IL-4, ↓IL-6, ↓hs-CRP, ↓TGF-β | (108) | |||

| SM-induced chronic pruritus | 96 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↑GPx, ↑SOD, ↑CAT, ↓Sp, ↓VAS, ↓pruritus severity, ↓DLQI scores | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (99) | |

| 96 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↓IL-8, ↓hs-CRP, ↓CGRP | (109) | |||

| SM-intoxicated with pulmonary complications | 78 | 4 weeks | 1.5 g/day + 15 mg/day | ↓FEV1, ↓FVC, ↓IL-6, ↓IL-8, ↓TNF-α, ↓TGF-β, ↓MCP-1, ↓Sp, ↓hs-CRP, ↓CGRP | safe, well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (89) | |

| 89 | 4 weeks | 1.5 g/day + 15 mg/day | ↑GSH, ↑CpAT score ↓MDA, ↓symptoms, ↓SGRQ | safe | (110) | ||

| T2D | 100 | 3 months | 500 mg/day + 5 mg/day | ↓glucose, ↓C-peptide, ↓HbA1c, ↓ALT, ↓AST | no adverse side effects | (90) | |

| 118 | 12 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↑HDL-C, ↓TC, ↓non-HDL-C, ↓LPA, ↓weight, ↓BMI, ↓TG | no adverse side effects | (111) | ||

| TBI | 62 | 7 days | 500 mg/day + 5 mg/day | ↓leptin | well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (100) | |

| 62 | 7 days | 500 mg/day + 5 mg/day | ↑GPx, ↓IL-6, ↓CRP, ↓MCP-1, ↓TNF-α, ↓SOFA score, ↓APACHE II, ↓NUTRIC score | safe, no adverse side effects | (101) | ||

| C3 complex + piperine | PMS | 76 | 10 days/3 CMC | 500 mg + 5 mg | ↑vitamin D, ↓AST, ↓DB | no serious adverse side effects | (102) |

| 124 | 10 days/3 CMC | 500 mg + 5 mg | ↓PSST score, ↓dysmenorrhea pain | no serious adverse side effects | (103) | ||

| T2D | 118 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day + 10 mg/day | ↑TAC, ↑SOD, ↓MDA | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (104) | |

| CartiJoint Forte | osteoarthritis | 53 | 6 weeks | 1.5g/day | ↓VAS score, ↓WOMAC score | no adverse side effects | (123) |

| CUC-1 paclitaxel | metastatic breast cancer | 150 | 12 weeks | 300 mg/week (i.v.) + 80 mg/m2 | ↑ORR, ↑physical performance | anemia, grade 3–4 side effects occurred in 5 patients | (129) |

| Coltect tablet | ulcerative colitis index | 20 | 8 weeks | 2 tablets/day | ↑remission rate, ↓Clinical activity | safe, tolerated | (130) |

| CuraMed | osteoarthritis | 201 | 12 weeks | 1.5 g/day | ↑Physical performance, ↑pain relief, ↑40 m walking speed ↓pain index, ↓stiffness, ↓degree of difficulty to move knee joint, ↓pain on standing from chair, ↓time taken to rise from chair, ↓time taken to ascend or descend from the stairs, ↓WOMAC index | safe, tolerated | (124) |

| periodontitis | 76 | 7 days | 200 mg | ↓postoperative discomfort, ↓pain | no adverse side effects | (125) | |

| CuraMin | osteoarthritis | 201 | 12 weeks | 1.5 g/day | ↑physical performance, ↑pain relief, ↑40 min walking speed, ↓WOMAC index, ↓pain index, ↓stiffness, ↓degree of difficulty to move knee joint, ↓pain on standing from chair, ↓time taken to rise from chair, ↓time taken to ascend or descend from the stairs | safe, tolerated | (124) |

| Curcugreen | obesity | 84 | 90 days | 500 mg/day | ↑physical activity, ↓BMI, ↓FPG, ↓HbA1c, ↓insulin | no serious adverse side effects | (126) |

| Curcugreen + zinc | obesity | 84 | 90 days | 500 mg/day + 30 mg/day | ↑Insulin sensitivity, ↓BMI, ↓FPG, ↓insulin resistance | no serious adverse side effects | (126) |

| Curcumall | OLP | 7 | 21 days | 20 drops/day | no adverse side effects | (131) | |

| curcumin amorphous formulation | NAFLD | 80 | 8 weeks | 500 mg/day | ↓liver fat content, ↓BMI, ↓TC, ↓LDL-C, ↓TG, ↓AST, ↓ALT, ↓glucose, ↓glycated Hb | safe, well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (132) |

| curcumin capsule (from Theravalues Corporation) | exercise-induced oxidative stress | 10 | 2 h before exercise ±2 h after exercise | 90, 180 mg | ↑BAP, ↑GSH, ↑CAT, ↓d-ROMs | (133) | |

| curcumin forte (Solgar) | schizophrenia | 38 | 24 weeks | 3 g/day | ↑PANSS score, ↓CDSS scores | no adverse side effects | (86) |

| curcuminoid-chitosan mouthwash | denture stomatitis | 30 | 2 weeks | 3 × 10 mL/day | ↑anti-Candida activity, complete response in 80% patients | no adverse side effects | (87) |

| Cureit/Acumin | aged adults | 30 | 3 months | 500 mg | ↑handgrip strength, ↑weight-lifting capacity, ↑distance covered ↓time taken to walk the same distance | no serious adverse side effects | (134) |

| healthy volunteers | 45 | single dose | 500 mg | exhibited greater bioavailability than phospholipid formulation and volatile oil formulation | no adverse side effects | (135) | |

| 30 | single dose | 500 mg | ↑VO2 max, ↓CK, ↓VAS score, ↓DOMS occurrence | no adverse side effects | (136) | ||

| CEO (essential oil formulation) | healthy subjects | 12 | 376 mg | ↑absorption | no adverse side effects | (137) | |

| CW8 (γ-cyclodextrin formulation) | healthy subjects | 12 | 376 mg | ↑absorption | no adverse side effects | (137) | |

| curcuminoid turmeric matrix formulation | RA | 36 | 90 days | 500 mg/day 1000 mg/day | ↑ACR response, ↓VAS score, ↓DAS score ↓ESR, ↓CRP, ↓RF values, ↓swollen joints, ↓tender joints | no serious adverse side effects | (138) |

| curcuminoid turmeric oil formulation | T2D | 53 | 10 weeks | 1500 mg/day | ↑adiponectin, ↓TG, ↓hs-CRP | (139) | |

| 53 | 10 weeks | 1500 mg/day | ↓mean weight, ↓BMI, ↓waist circumference, ↓FBS | no adverse side effects | (140) | ||

| curcumin alcohol gel | psoriasis | 10 | 4 weeks | 1% gel | ↓PhK activity, ↓TRR, ↓severity of parakeratosis, ↓CD8+ T cells | (141) | |

| curcumin gel | OSF | 60 | 6 weeks | 3 or 4x 5 mg/day | ↓burning sensation, ↑mouth opening capacity | safe, nontoxic | (142) |

| OSF | 40 | 4 weeks | 2% gel | ↓burning sensation, ↓LDH, ↑mouth opening capacity | safe, noninvasive, no adverse side effects | (143) | |

| curcumin mucoadhesive patch | OSF | 40 | 4 weeks | 2% gel | ↓burning sensation, ↓LDH, ↑mouth opening capacity | safe, noninvasive, no adverse side effects | (143) |

| curcumin + Boswellia + spirulina | benign thyroid nodules | 34 | 12 weeks (3 visits with 6 week interval) | 800 + 100 + 100 mg/day | ↓benign thyroid nodules | no adverse side effects | (81) |

| CU-FEO (curcumin + fennel essential oil) | IBS | 121 | 30 days | 84 mg +50 mg | ↑symptom relief, ↑QoL ↓severity score, ↓abdominal pain | safe, well-tolerated, no adverse side effects | (82) |

| curcumin + piperine | healthy volunteers | 8 | single dose | 2 g+20 mg | ↑bioavailability no adverse side effects | safe, well-tolerated, | (55) |

| recreationally active subjects | 23 | 11 days | 2 g/day +20 mg/day | ↑DOMS time, ↓Ubiquitin, ↓MAFbx/atrogin-1, ↓chymotrypsin-like protease | (69) | ||

| healthy subjects | 16 | 7 days | 500 mg/day +20 mg/day | ↓IL-2, ↓TNF-α, ↓IFN, ↓IL-6, ↓IL-10 | (70) | ||

| arsenic-induced oxidative stress | 286 | 3 months | 1g/day | ↑antioxidant capacity, ↓DNA damage, ↓ROS generation, ↓lipid peroxidation | (71) | ||

| bronchial asthma | 40 | 2 months | 2 × 750 mg/day +5 mg/day | ↓IL-6, ↑FEV1, ↑FVC, ↑ACT score | (72) | ||

| COVID-19 | 140 | 14 days | 2x(525 mg+2.5 mg) | ↑O2 saturation, ↓symptoms, ↓deterioration, ↓hospitalized duration | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (73) | |

| COVID-19 | 46 | 14 days | 2x(500 mg+5 mg)/day | ↓weakness, ↓dry cough, ↓sore throat, ↓sputum cough, ↓ague, ↓muscular pain, ↓headache, ↓dyspnea | no serious adverse side effects | (74) | |

| OSF | 90 | 6 months | 600 mg/day | ↑mouth opening flexibility, ↑tongue protrusion, ↑cheek flexibility, ↓burning sensation | no adverse side effects | (75) | |

| pancreatitis | 20 | 6 weeks | 500 mg/day +5 mg/day | ↑GSH, ↓erythrocyte MDA levels | no adverse side effects | (76) | |

| T2D | 118 | 12 weeks | 1 g/day +10 mg/day | ↑adiponectin, ↓leptin, ↓TNF-α, ↓leptin/adiponectin ratio | (77) | ||

| curcumin + piperine + ginger | RA | 60 | 8 weeks | - | ↓TJC, ↓ESR, ↓SJC, ↓DAS score, ↓inflammation, ↓pain | no serious adverse side effects | (78) |

| curcuminoids + piperine + taurine | hepatocellular cancer | 20 | 3 cycles 30 days each | 4 g + 40 mg +500 mg/day | ↑OS, ↑albumin, ↓IL-10, ↓miR-21, ↓AST, ↓ALT, ↓AFU | (79) | |

| curcuminoids + piperine | healthy volunteers | 8 | 2 days | 16 g + 96 mg | no significant effect on paracetamol metabolization | (115) | |

| Oxy-Q (curcumin + quercetin) | FAP | 5 | 6 months | 1440 mg/day +60 mg/day | ↓polyp number, ↓polyp size | no serious adverse side effects | (83) |

| curcumin tablet lactoferrin + N-acetylcysteine + pantoprazole | H. pylori+ with dyspepsis | 25 | 7 days | 60 mg+200 mg+ 1200 mg +40 mg/day | ↑cure rate, ↓overall severity, ↓serum pepsinogens | (84) | |

| curcumin extract + Calendula extract | CP/CPPS III | 55 | 1 month | 350 mg +80 mg | ↓inflammation | no adverse side effects, well-tolerated | (85) |

| curcumin + propranolol + aliskiren + cilazapril + celecoxib + piperine + aspirin + metformin | glioblastoma | 10 | 10 weeks | - | ↑median survival | minimal adverse effects, safe | (80) |

| Ialuril soft gel tablets | endometriosis | 20 | 12 weeks | 2 pills/day | ↓dysmenorrhea, ↓chronic pelvic pain, ↓dysuria | no adverse side effects | (145) |

| Infla-Kine | healthy volunteers | 24 | 4 weeks | 2 capsules/day | ↑QoL, ↓IL-6, ↓IL-8, ↓NF-κB, ↓TNF-α | (144) | |

| Killox | TURP, TURB, and BPH | 80 | 10–60 days | Once/day | ↓postoperative and late complications, duration of irritation | well-tolerated, no adverse side effects | (146) |

| LCD capsule | dry eye syndrome | 60 | 8 weeks | 1 tablet/day | ↑Schirmer’s strip wetness length, ↑tear volume, ↑TBUT score, ↑SPEED score, ↓OSDI score, ↓corneal and conjunctival staining score, ↓tear osmolarity, ↓MMP-9 positive score | safe, no adverse side effects | (147) |

| MEC | RA with chronic periodontitis | 45 | 6 weeks | 2 × 10 mL/day | ↓ESR, ↓RF, ↓CRP, ↓ACPA, ↓PI, ↓PD, ↓CAL | well-tolerated | (88) |

| NAIOS | ME/CFS | 76 | 15.2 ± 4.81 months | - | ↓IgM-mediated autoimmune response to OSEs and NO- adducts, ↓FF score, ↓severity of illness | (149) | |

| NP capsule by Vitacost | healthy volunteers | 11 | 2 weeks | 1 g/day | ↓TNF-α induced NF-κB activation | safe, well-tolerated | (148) |

| Nutrafol women’s capsule | women with self-perceived hair thinning | 40 | 6 months | 4 capsules/day | ↑number of terminal and vellus hairs, ↑hair growth, ↑quality, ↑volume, ↑thickness | no serious adverse side effects, safe, well-tolerated | (153) |

| PureVida | breast cancer | 45 | 1 month | 3 capsules/day | ↓CRP, ↓pain score | no serious adverse side effects | (150) |

| Reglicem | fasting dysglycemia | 148 | 3 months | 1 tablet/day | ↓FBS, ↓PPBS, ↓HbA1c, ↓insulin, ↓HOMA-index, ↓TG, ↓TC, ↓CRP | no serious adverse side effects | (151) |

| Turmix tablet | OSF | 147 | 12 weeks | 3 times a day | ↑mouth opening flexibility, ↑tongue protruding capacity, ↓burning sensation | (113) | |

| OSF | 12 weeks | 900 mg/day | ↑mouth opening flexibility, ↓burning sensation | no adverse side effects | (114) | ||

| Turmix tablet + Turmix mouthwash | OSF | 147 | 12 weeks | 3 times a day +2 times a day | ↑tongue protruding capacity, ↑mouth opening flexibility, ↓burning sensation | (113) | |

| WEC | healthy subjects | 47 | 8 weeks | 0.75 g | ↑H2O content of the skin, ↓TEWL | no serious adverse side effects | (152) |

| WEC + curcumin | healthy subjects | 47 | 8 weeks | 0.75 g + 30 mg | ↑H2O content of the skin, ↓TEWL | no serious adverse side effects | (152) |

| Second-Generation Formulation | |||||||

| Actbiome | healthy subjects | 30 | 8 weeks | 2 × 250 mg/day | ↑fecal bifidobacteria, ↑fecal lactobacilli, ↑ideal stool form and frequency, ↓IL-10, ↓GSRS score | no adverse side effects | (154) |

| Algocur | men rugby players with osteo-muscular pain | 50 | 10 days | 2 tablets/day | ↑physical function, ↑adherence to treatment, ↓pain, ↓VAS score | safe, well-tolerated | (199) |

| BioCurc/CLDM | healthy volunteers | 15 | 48 h (14 days wash out period) | 6 capsules (64.6 mg) | ↑absorption, ↑bioavailability | safe, no adverse side effects | (155) |

| cavacurcumin + ω-3 FA + astaxanthin + GLA + tocotrienols + hydroxy tyrosol + vitamin D3 + potassium | healthy volunteers | 80 | 4 weeks | 500 mg +675 mg +3 mg+9.5 mg+ 12.5 mg+6.25 mg +1000 IU + 12.5 mg | ↑brachial flow mediated dilation, ↑EPA, ↑ω-3 FA index, ↓hs-CRP, ↓SBP | no adverse side effects, well-tolerated | (156) |

| cCHC | healthy volunteers | 12 | 4 trials separated by 7 days each | 376 mg | ↑absorption compared to CS, CP, CTR | no adverse side effects | (157) |

| diabetic macular edema | 73 | 6 months | 2 tablets/die | ↓CRT, ↓inner retinal layer thickness | safe, no adverse side effects | (158) | |

| CSL (phytosomal formulation) | healthy subjects | 12 | 376 mg | ↑absorption | no adverse side effects | (137) | |

| curcumin phosphatidyl choline + Irinotecan | solid tumors | 23 | 28 days | 1, 2, 3 and 4 g/day + 200 mg/m2 | ↑delay in disease progression | no toxicity, tolerated leukopenia, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea | (41) |

| Curserin | obesity | 80 | 8 weeks | 800 mg/day | ↑HDL-C, ↓FPG, ↓FPI, ↓GGT, ↓HOMA-IR, ↓GOT, ↓GPT, ↓LAP, ↓FLI, ↓TG, ↓non-LDL-C, ↓HSI | no adverse side effects | (159) |

| curcuminoid micelles | healthy subjects | 42 | 6 weeks (4 weeks wash out phase) | 294 mg/day | ↑Bioavailability | safe and well-tolerated GI side effects | (160) |

| MI | 110 | single dose | 480 mg | ↓raise of CK-MB | (163) | ||

| FLAVOMEGA | DMD, FSHD, LGMD | 29 | 24 weeks | 80 g/day | ↑muscle performance, ↑global strength, ↑lower limb strength, ↑isokinetic knee extension, ↑6 min walk distance, ↓CK, ↓ROS, ↓valine, ↓FFA | no adverse side effects, well-tolerated | (164) |

| Flexofytol | osteoarthritis | 22 | 3 months | 6 capsules/day | ↓Coll2–1, ↓CRP, ↓global disease assessment activity | well-tolerated, no serious side adverse | (165) |

| Flexofytol + Boswellia extract + pine bark extract + methylsulfonyl methane | osteoarthritis | 106 | 12 weeks | 168 mg/day +250 mg/day +100 mg/day +1500 mg/day | ↓activity impairment, ↓FIHOA score | no serious adverse side effects | (166) |

| iron + HydroCurc | healthy subjects | 155 | 6 weeks | 18 mg +500 mg/day 65 mg +500 mg/day | ↓TBARS, ↓TNF-α, ↓GI side effects, ↓fatigue, ↓IL-6 | no adverse side effects | (167) |

| HydroCurc + maltodextrin | healthy and young males | 28 | single dose | 500 mg+500 mg | ↑IL-6, ↑IL-10, ↓DOMS pain, ↓TC, ↓capillary lactate and LDH | (168) | |

| lecithinized curcumin | MetS | 120 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | no effect on vitamin E, ↓vitamin E/LDL, ↓vitamin E/TC, ↓vitamin E/TG | no serious adverse side effects | (170) |

| Lipocurc | locally advanced or metastatic tumors | 32 | 8 weeks | 100, 300 mg/m2 | ↓PSA, ↓CEA, ↓CA 19–9 | well-tolerated, anemia, hemolysis | (169) |

| Meriva | healthy subjects | 9 | 209, 376 mg of curcuminoids | ↑absorption | (173) | ||

| healthy subjects | 12 | 7 days | 2 g/day | ↑absorption | no serious adverse side effects | (174) | |

| CKD | 24 | 3 or 6 months | 1000 mg/tablet | ↓MCP-1, ↓IL-4, ↓IFNγ, ↓TBARS, ↓P-cresyl sulfate, ↓carbohydrate intake, ↓protein intake, ↓total fiber intake, ↓phosphorus and potassium intake, ↓Escherichia-Shigella, ↓Enterobacter verrucomicrobia, ↓Firmicutes, ↑Lachnoclostridium spp., ↑Lachnospiraceae family, ↑Lactobacillaceae spp., ↑Prevotellaceae | no adverse side effects | (175) | |

| diabetes with microangiopathy | 50 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day | ↑PO2, ↓skin flux, ↓edema | well-tolerated | (176) | |

| 77 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day | ↑visual acuity, ↑microcirculation, ↓retinal edema, ↓peripheral edema | well-tolerated | (177) | ||

| diabetic macular edema | 11 | 3 months | 1 g/day | ↓macular edema | no adverse side effects | (195) | |

| Gulf War illness | 39 | every 30 ± 3 days four times | 1 or 4 g day | ↓symptom severity | no serious adverse side effects | (178) | |

| hypercholesterolemia | 76 | 4 weeks | 1 g/day | ↓TC, ↓LDL-C, ↓TC/HDL ratio | no adverse side effects | (179) | |

| MetS | 120 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | ↑zinc, ↑zinc/copper ratio | (180) | ||

| NAFLD | 102 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day | ↓TC, ↓TG, ↓LDL-C, ↓non-HDL-C, ↓uric acid | safe, well-tolerated | (181) | |

| 102 | 8 weeks | 1 g/day | ↑hepatic vein flow, ↓portal vein diameter, ↓liver volume ↓BMI, ↓waist circumference, ↓AST, ↓ALT | safe, well-tolerated | (182) | ||

| 36 | 8 weeks | 1.5 g/day | ↑hepatic vein flow, ↓NAFLD severity, ↓BMI, ↓TC, ↓LDL-C, ↓non-HDL-C, ↓TG, ↓portal vein diameter, ↓Liver size, ↓AST, ↓ALT, ↓serum uric acid, ↓HDL | safe, well-tolerated | (183) | ||

| 58 | 8 weeks | 250 mg/day | ↓3-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid, ↓3-hydroxyisobutyrate, ↓citrate, ↓kynurenine, ↓succinate, ↓α-ketolgutarate, ↓methylamine, ↓yrimethylamine, ↓hippurate, ↓indoxyl sulfate, ↓taurocholic acid ↓chenodeoxy cholic acid, ↓lithocholic acid, | (193) | |||

| 65 | 8 weeks | 250 mg/day | ↑HDL-C, ↑adiponectin, ↓leptin | safe, no side effects | (194) | ||

| 54 | 8 weeks | 250 mg/day | ↓MLH1, ↓MSH2, ↓weight, ↓waist circumference, ↓hip circumference, ↓BMI | safe, well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (184) | ||

| osteoarthritis | 50 | 12 weeks | 1 g/day | ↑walking distance in treadmill, ↓WOMAC score, ↓CRP, ↓distal edema, ↓hospitalization, ↓usage of anti-inflammatory drugs | no adverse side effects | (185) | |

| 100 | 8 months | 1 g/day | ↑Karnofsky scale score, ↓stiffness, ↓WOMAC score, ↓negative effects on social function, ↓IL-1β, ↓IL-6, ↓ESR, ↓sCD40L, ↓sVCAM-1, ↑distance covered on treadmill | excellent tolerability, safe | (186) | ||

| pancreatic cancer | 44 | until death | 2 g/day 28 days cycle | ↑response rate, ↑stable disease period, ↑OS, ↑PFS | safe | (187) | |

| prostatic hyperplasia | 61 | 24 weeks | 1 g/day | ↑QoL, ↓signs and symptoms, ↓urinary infections and block | no adverse side effects | (188) | |

| psoriasis | 63 | 12 weeks | 2 g/day | ↓IL-22, ↓PASI | safe and well-tolerated | (189) | |

| risk of T2D | 29 | 12 weeks | 1 g/day | ↓GSK-3β, ↓IAPP, ↓insulin resistance ↓risk of Alzheimer’s disease | no adverse side effects | (190) | |

| solid tumors | 96 | 8 weeks | 900 mg/day | ↑QoL, ↓IL-6, ↓TNF-α, ↓TGF-β, ↓Sp, ↓hs-CRP, ↓CGRP, ↓MCP-1 ↓IL-8 | safe and well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (191) | |

| solid tumors with radio- and chemo-therapy-induced side effects | 158 | 4 months | 500 mg/day | ↓burden of side effects | no serious adverse side effects | (192) | |

| Meriva + fish oil | healthy subjects | 16 | 4 days separated by a week of out period | 180 mg +2 capsules | ↓PPBS, post- prandial insulin | (196) | |

| Meriva + anthocyanin | colorectal adenomatous polyposis | 35 | 4–6 weeks | 1 g/day +1g/day | ↓NFκB, ↓Ki67 | no serious adverse side effects | (198) |

| Meriva + phytosterol | hyper-cholesterolemia | 70 | 4 weeks | 200 mg/day +2 g/day | ↓TC, ↓LDL-C | no adverse side effects | (179) |

| 82 | 4 weeks | 228 mg/day +2.3 g/day | ↓TC, ↓LDL-C, ↓TC:HDL-C ratio, ↓CVD risk, ↓LDL-P number | safe | (197) | ||

| micellar curcumin formulation (beverage) | glioblastoma | 13 | 4 days | 3 × 70 mg | ↑bioavailability, ↑inorganic phosphate, ↓PCr/Pi ratio, ↑intratumoral pH | no serious adverse side effects | (162) |

| nanocurcumin (curcumin nanomicelle from Exir Nano Sina company) | amylotrophic lateral sclerosis | 54 | 12 months | 80 mg/day | ↑survival | safe, no adverse side effects | (218) |

| ankylosing spondylitis | 24 | 4 months | 80 mg/day | ↓RORγ t, ↓IL-17, ↓IL-23, ↓miR-141, ↓miR-155, ↓miR-200, ↓symptoms | (219) | ||

| Behcet’s disease | 36 | 8 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑Treg cells, ↑RNAs of FOXP3, ↑TGF-β, ↑IL-10, ↑miR-25, ↑miR-106b | no adverse side effects | (237) | |

| bladder cancer | 26 | 4 weeks | 160 mg/day | ↑clinical response | well-tolerated | (246) | |

| CAD | 80 | 3 months | 80 mg/day | ↓MMP-9, ↓MMP-2 | safe | (220) | |

| COVID-19 | 40 | 14 days | 160 mg/day | ↓mRNA and serum IL-6, mRNA and serum IL-1β, ↓serum IL-18 | (238) | ||

| COVID-19 | 60 | 2 weeks | 4 soft gels/day | ↑lymphocyte count, ↓symptoms | no adverse side effects | (221) | |

| COVID-19 | 41 | 2 weeks | 160 mg/day | ↑oxygen saturation, ↓symptoms, ↓symptom resolution time, ↓lymphocyte count, ↓hospitalized duration | no serious adverse side effects | (243) | |

| COVID-19 | 80 | 21 days | 160 mg/day | ↑Treg cell frequency, ↑FOXP3, ↑IL-10, ↑IL-35, ↑TGF-β | (239) | ||

| COVID-19 | 40 | 2 weeks | 160 mg/day | ↑IL-4, ↑FOXP3, ↓IFNγ, ↓TBX21 | no adverse side effects | (240) | |

| COVID-19 | 80 | 21 days | 160 mg/day | ↓RORγ t, ↓IL-17, ↓IL-21, ↓IL-23, ↓GM-CSF, ↓symptoms, ↓Th17 count, ↓hospitalized duration ↓mortality rate, | (241) | ||

| COVID-19 | 60 | 7 days | 240 mg/day | ↓mortality rate, ↓IFNγ, ↓TNF-α ↓IL-6, ↓IL-1β | safe and tolerable | (242) | |

| COVID-19 | 48 | 6 days | 160 mg/day | ↑O2 saturation, ↓symptoms, ↓LOS | no adverse side effects | (222) | |

| diabetic foot ulcer | 60 | 12 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑TAC, ↑Insulin sensitivity, ↑GSH, ↓FPG, ↓insulin, ↓TC, ↓LDL-C | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (248) | |

| diabetes on HD | 60 | 12 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑TAC, ↑TN, ↑PPARγ, ↑LDLR, ↓TC, ↓LDL-C, ↓VLDL-C, ↓MDA, ↓TC/HDL-C, ↓hs-CRP, ↓insulin, ↓TG, ↓FPG, | no adverse side effects | (249) | |

| DSPN | 80 | 8 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓HbA1c, ↓FBS, ↓total reflex score, ↓total neuropathy score, ↓waist circumference, ↓temperature, | safe, well-tolerated | (252) | |

| gingivitis | 50 | 4 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓MGI, ↓PBI | no adverse side effects | (261) | |

| hemodialysis | 54 | 3 months | 120 mg/day | ↓serum IL-6 and TNF-α, ↓mRNA IL-6 and TNF-α | (291) | ||

| HNC | 32 | 6 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑OM development duration, ↓OM severity | no adverse side effects | (223) | |

| infertility | 60 | 10 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑sperm count, ↑sperm concentration, ↑sperm motility, ↑TAC, ↑testosterone, ↓MDA, ↓CRP, ↓TNF-α, ↓FSH, ↓LH, ↓PRL | no adverse side effects | (229) | |

| MetS | 50 | 12 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓TG, ↓HOMA-β | (230) | ||

| 50 | 12 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑adiponectin, ↑TAC, ↓MDA | no serious adverse side effects | (253) | ||

| migraine | 44 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓MCP-1, ↓headache attack frequency, ↓headache severity and duration | no adverse side effects | (255) | |

| 100 | 8 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓frequency, severity, duration of headache | no adverse side effects | (256) | ||

| 80 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | no significant effect on VCAM | (257) | |||

| 80 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓headache frequency, ↓IL-1β | no adverse side effects | (258) | ||

| NAFLD | 84 | 3 months | 80 mg/day | ↑HDL, ↑QUICKI, ↑Nesfatin, ↓fatty liver degree, ↓AST, ↓ALT, ↓FBS, ↓FBI, ↓HbA1c, ↓TG, ↓TC, ↓LDL, ↓HOMA-IR, ↓TNF-α, ↓IL-6, ↓hs-CRP | no adverse side effects | (254) | |

| oral mucositis | 50 | 7 weeks | 160 mg/day | ↓pain score, ↓severity | (262) | ||

| OLP | 57 | 1 month | 80 mg/day | ↓pain, ↓lesion, ↓burning sensation | no adverse side effects | (247) | |

| osteoarthritis | 30 | 3 months | 80 mg/day | ↑Treg cells, ↓VAS score, ↓CRP, ↓CD4+ and CD8 T+ cells, ↓Th 17 cells, ↓B cells | no adverse side effects | (226) | |

| 30 | 3 months | 80 mg/day | ↓miR-155, ↓miR-138, ↓miR-16 | (236) | |||

| Parkinson’s disease | 60 | 9 months | 80 mg/day | ↓MDS-UPDRS part III score | well-tolerated, mild GI symptoms | (231) | |

| prostate cancer | 64 | 3 days before RT and during RT | 120 mg/day | ↓radiation-induced proctitis | well-tolerated, no serious adverse side effects | (224) | |

| RA | 65 | 12 weeks | 120 mg/day | ↓DAS score, ↓TJC, ↓SJC | no adverse side effects | (225) | |

| RRMS | 25 | 6 months | 80 mg/day | ↓Th17 cells, ↓RORγ t, ↓IL-17 | (259) | ||

| 50 | 6 months | - | ↑miR-15a, ↑miR-19b, ↑miR-106b, ↑miR-320a, ↑miR-363, ↑miR-31, ↑miR-181c, ↑miR-150, ↑miR-340, ↑miR-599, ↓miR-17-92, ↓miR-16, ↓miR-27, ↓miR-29b, ↓miR-126, ↓miR-128, ↓miR-132, ↓miR-155, ↓miR-326, ↓miR-550 | no systemic adverse effects | (232) | ||

| 50 | 6 months | 80 mg/day | ↑Treg cells frequency, ↑FOXP3, ↑IL-10, ↑TGF-β | (260) | |||

| schizophrenia | 64 | 16 weeks | 80, 160 mg/day | ↑response rate, ↓PANSS positive subscale, ↓PANSS negative subscale score, ↓CGI-S, ↓CGI-I, ↓PANSS general psychopathology subscale score, ↓total PANSS score | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (233) | |

| sepsis | 40 | 10 days | 160 mg/day | ↓PCT, ↓IL-6, ↓TNF-α, ↓duration of mechanical ventilation, ↓SOFA | (244) | ||

| 40 | 10 days | 160 mg/day | ↓MDA, ↓IL-18, ↓IL-1β, ↓ICAM-1, ↓TC, ↓VCAM-1, ↓ IL-6, ↓TLR-4, ↓Bax, ↓FBS, ↓TG, ↓ALT, ↓ALP, ↓GGT, ↓bilirubin, ↓creatinine, ↓prealbumin, ↓SOFA score, ↓duration of ventilation, ↑IL-10, ↑CAT, ↑SOD, ↑TAC, ↑Bcl-2, ↑Nrf-2, ↑TLC | (245) | |||

| 14 | 10 days | 160 mg | ↓ESR, ↓IL-8, ↓neutrophils, ↓platelets, ↓Presepsin, ↓WBCs | no adverse side effects | (227) | ||

| T2D | 40 | 8 weeks | 80 mg/day (with endurance training) | ↓FBG, ↓glycated Hb, ↓insulin | (250) | ||

| T2D associated polyneuropathy | 80 | 8 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓depression, ↓anxiety | safe, well-tolerated | (251) | |

| thyroid cancer undergone thyroidectomy | 21 | 10 days | 160 mg/day | ↓micronuclei in lymphocyte | safe, no adverse side effects | (228) | |

| ulcerative colitis | 56 | 4 weeks | 240 mg/day | ↓score for urgency of defecation, ↓SCCAI score | no serious adverse side effects | (235) | |

| nanocurcumin (from Theravalues Corp. Japan) | MetS | 44 | 6 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑IL-10, ↑BDNF, ↑TAC, ↓IL-6, ↓MDA, ↓hs-CRP | (265) | |

| nanocurcumin | breast cancer | 42 | 2 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓RISR severity, ↓pain | (266) | |

| nanocurcumin | migraine | 38 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓Pentraxin 3 | (267) | |

| 80 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓IL-6 mRNA, ↓IL-6, ↓hs-CRP | no adverse side effects | (268) | ||

| 40 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓IL-17, ↓IFNγ | no adverse side effects | (269) | ||

| nanocurcumin (prepared using wet milling technique) | RA | 10 | 8 months | 20 mg/L and 50 mg/L | ↓inflammation | (270) | |

| nanocurcumin + ω-3 fatty acids | migraine | 72 | 2 months | - | ↓attack frequency, ↓ICAM-1 | (271) | |

| 74 | 2 months | 80 mg/day +2.5 g/day | ↓TNF-α, ↓attack frequency | no adverse side effects | (272) | ||

| 80 | 2 months | 80 mg/day +2.5 g/day | ↓IL-6 mRNA, ↓IL-6, ↓hs-CRP | no adverse side effects | (268) | ||

| 74 | 2 months | 80 mg/day +1800 mg/day | ↓COX-2, ↓iNOS, ↓frequency, severity and duration of headache | (273) | |||

| 80 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓VCAM, ↓headache severity and frequency | (257) | |||

| 80 | 2 months | 80 mg/day | ↓headache frequency, ↓IL-1β | no adverse side effects | (258) | ||

| nanocurcumin + acetretin | psoriasis | 15 | 12 weeks | 3 g/day +0.4 mg/kg/day | ↓PASI | no serious adverse side effects | (274) |

| nanocurcumin + coenzyme Q10 | migraine | 100 | 8 weeks | 80 mg/day +300 mg/day | ↑MSQ score, ↓frequency, severity, duration of migraine, ↓MIDAS score, ↓HIT-6 score | no adverse side effects | (256) |

| nanocurcumin + Nigella sativa oil | postmenopausal women | 120 | 6 months | 80 mg +1 g | ↑miR-21 | no serious adverse side effects | (275) |

| nanocurcumin mouthwash | HNC oral mucositis | 74 | 6 weeks | 0.1% | ↑delayed onset, ↓risk of OM, ↓severity | no adverse side effects | (276) |

| curcumin nanomicelle gel from Sina (Iran) | OLP | 31 | 4 weeks | 1% | ↑efficacy index, ↓REU score | well-tolerated, no adverse side effects | (263) |

| RAS | 48 | 1 week | 3 × 1%/day | ↑efficacy index, ↓lesion size, ↓pain score | no adverse side effects | (264) | |

| curcumin nanomicelle from Minoo Pharmaceuticals Co. with resistance training | NAFLD | 45 | 12 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↓AST, ↓ALT | (277) | |

| nanogel 2% curcumin | chronic periodontitis | 45 | 45 days | 2% gel | ↓Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, ↓Tannerella forsythia, ↓Porphyromonas gingivalis | (278) | |

| curcumin nanoparticle | periodontitis | 20 | 15 days | 50 μg | ↑Veillonella parvula, ↑Actinomyces spp., ↓PPD, ↓CAL, ↓BOP, ↓IL-6, ↓Porphyromonas gingivalis | no adverse side effects | (279) |

| NE 65 | healthy subjects | 15 | 4 weeks | 0.125 g | ↓skin surface permittivity, ↓NMF | (200) | |

| NLC 65 | healthy subjects | 15 | 4 weeks | 0.125 g | ↑TEWL, ↓NMF, ↓skin surface permittivity, ↓urea | (200) | |

| NLC 80 | healthy subjects | 15 | 4 weeks | 0.125 g | ↑TEWL, ↓skin hydration, ↓skin surface permittivity, ↓NMF, ↓urea | (200) | |

| phospholipidated curcumin | MetS | 120 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | no significant improvement in pro- and antioxidant balance | (204) | |

| 120 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | ↓saturated fatty acid intake | (205) | |||

| 120 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | ↓severe anxiety | no serious adverse side effects | (206) | ||

| 80 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | no significant effect on BMI, waist circumference, and serum cathepsin D levels | (207) | |||

| phospholipidated curcuminoids | MetS | 120 | 6 weeks | 1 g/day | no significant effect | (208) | |

| phytosomal curcumin | MetS | 81 | 6 weeks | 1 mg/day | no considerable effect on aryl esterase activities | (203) | |

| curcuminoid cream from GPO, Thailand | focal or generalized vitiligo | 10 | 12 weeks | Twice daily | ↑repigmentation | safe, well-tolerated, minor adverse side effects | (202) |

| Theracurmin | non demented adults | 46 | 18 months | 180 mg/daymonths | ↑verbal and visual memory, ↑attention, ↓depression, ↓FDDNP | Four subjects complained abdominal pain, gastritis, nausea and one subject complained heat and pressure in chest | (280) |

| aged adults | 40 | 18 months | 180 mg/day | ↑improved SRT, ↑visual memory ↑attention, ↓neurodegeneration | safe | (281) | |

| healthy subjects | 14 | single dose | 30 mg | ↑plasma concentration of curcumin, ↑alcohol intoxication, ↓acetaldehyde | no adverse side effects | (282) | |

| healthy subjects | 6 | 150 mg, 210 mg | ↑absorption, ↑bioavailability curcumin, ↑alcohol intoxication, ↓acetaldehyde | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (283) | ||

| healthy subjects | 9 | 182.4 ± 1.0 mg | ↑absorption and bioavailability than BCM-95 and Meriva | no adverse side effects | (116) | ||

| healthy subjects | 14 | 4 weeks | 300 mg/day | ↑MVC torque recovery, ↓CK | (284) | ||

| healthy subjects | 10 | 7 days before exercise | 180 mg/day | ↓IL-8, ↓inflammation | (288) | ||

| healthy subjects | 10 | 7 days after exercise | 180 mg/day | ↑MVC torque, ↑ROM, ↓muscle soreness, ↓CK activity | (288) | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 30 | 12 weeks | 360 mg/day | ↑clinical response rate, ↑lesion healing, ↓endoscopic disease severity | no serious adverse side effects | (290) | |

| COPD | 48 | 24 weeks | 180 mg/day | ↓AT-LDL | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (293) | |

| exercise-induced muscle soreness | 24 | 7 days before and 4 days after exercise | 180 mg/day | ↑ROM, ↓muscle soreness | (287) | ||

| osteochondral diseases | 50 | 12 months | 180 mg/day | ↑JOA score, ↑VAS, ↑JKOM, ↓roughness in lateral compartment of femur, ↓stiffness of knee cartilage | no serious adverse effects | (292) | |

| postmenopausal women | 56 | 8 weeks | 150 mg/day | ↓brachial SBP | no adverse side effects | (289) | |

| noninsulin dependent DM | 33 | 6 months | 180 mg/day | ↓rise in oxidized LDL, ↓TG, ↓γ-GTP | (294) | ||

| theracurmin + exercise | postmenopausal women | 45 | 8 weeks | 150 mg/day | ↓brachial and aortic SBP, ↓radial AIx, ↓DBP | no adverse side effects | (289) |

| theracurmin solution | pancreatic or biliary duct cancer | 16 | >9 months | 200–400 mg/day | no adverse side effects | (285) | |

| theracurmin beverage | healthy subjects | 24 | 30 mg/100 mL | ↑absorption efficiency | no adverse side effects | (286) | |

| valdone curcumin soft gel | ulcerative colitis | 69 | 6 weeks | 100 mg/day | ↑clinical response rate, ↑clinical remission rate | no serious adverse side effects | (201) |

| Third-Generation Formulation | |||||||

| curcumin galactomannan formulation | healthy subjects | 18 | 30 days | 1000 mg/day | ↑α- and β-waves of EEG, memory improvement, ↓α/β ratio, audio-reaction time, ↓choice based-visual reaction time | (302) | |

| osteoarthritis | 80 | 84 days | 400 mg/day | ↑walking performance, ↓VAS ↓stiffness score, ↓IL-1β, ↓VCAM | safe | (298) | |

| CurQfen | occupational stress | 60 | 30 days | 1000 mg/day | ↑QoL, ↑CAT, ↑SOD, ↑GPx, ↑GSH, ↓TBARS, ↓fatigue, ↓lipid peroxidation | safe, no serious adverse side effects | (299) |

| obesity | 22 | 12 weeks | 500 mg/day | ↑HDL, ↓homocysteine | no adverse side effects | (300) | |

| osteoarthritis | 84 | 6 weeks | 400 mg/day | ↑improvement in walking, ↑physical activity, ↓VAS score, ↓WOMAC score, ↓stiffness score, ↓hs-CRP, ↓IL-1β, ↓IL-6, ↓sVCAM | no serious adverse side effects | (301) | |

| curcuRouge | aged adults | 40 | 4 weeks | 180 mg/capsule | ↓WBC count, ↓neutrophil count, ↓neutrophil/lymphocyte | no safety issues | (303) |

| curcuwin Ultra+ | healthy subjects under fasting | 24 | 250, 500 mg | ↑bioavailability | no safety issues | (304) | |

| Longvida | aged adults | 60 | 12 weeks | 400 mg/day | ↑mood-related benefits, ↓fatigue ↑cognitive benefits | safe, well-tolerated | (305) |

| aged adults | 80 | 12 weeks | 400 mg/day | ↑working memory performance ↓fatigue score, ↓tension, ↓anger, effects | no serious adverse side | (306) | |

| middle aged and older adults | 39 | 12 weeks | 2000 mg/day | ↑vascular NO bioavailability, flow-mediated dilation, ↑NO-dependent dilation | safe, well-tolerated ↓oxidative stress, ↑brachial artery | (307) | |

| healthy subjects | 38 | 4 weeks | 80 mg/day | ↑CAT, ↑MPO, ↑NO scavenged radicals, ↓TG, ↓salivary amylase, ↓ALT, ↓Aβ protein, ↓ICAM | (308) | ||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 8 | 2 × 20 g/day | 2 days | ↑detection of amyloid spots in retina | (314) | ||

| obesity | 134 | 16 weeks | 160 mg/day | ↑cerebrovascular responsiveness | (309) | ||

| 152 | 16 weeks (160 mg/day curcumin) | 800 mg | no significant effect on arthritis | no serious adverse side effects | (310) | ||

| OSF | 30 | 3 months | 2 g/day | ↑mouth opening capacity, ↓burning sensation | (312) | ||

| osteoarthritis effects | 50 | 90 days | 2 × 400 mg/day | ↓VAS score, ↓WOMAC score | no serious adverse side | (313) | |

| Longvida + fish oil | obesity | 152 | 16 weeks | 800 mg/day + 400 mg/day EPA + 2 g/day DHA | ↑HDL-C, ↓HR, ↓TG ↓cerebral artery stiffness | no serious adverse side effects | (311) |

| obesity | 134 | 16 weeks | 800 mg/day + 400 mg/day EPA + 2 g/day DHA | ↑cerebrovascular responsiveness 400 mg/day EPA + 2 g/day DHA | (309) | ||

Abbreviations: Aa, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans; ACPA, Anticitrullinated protein antibody; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ACT, Asthma control test; ADPKD, Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; AFU, Alpha-L-fucosidase; ALDH, Aldehyde dehydrogenase; ALP, Alkaline phosphatase; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AOPPs, Advanced oxidation protein products; APACHE II, Acute physiology, and chronic health 370 evaluation II; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; BALP, Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; BANA, N-benzoyl-dl-arginine-2-naphthylamide; BAP, Biological antioxidant potential; BAX, Bcl-2 associated X-protein; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BDNF, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMD, Bone mineral density; BMI, Body mass index; BOP, Bleeding on probing; BPH, Benign prostatic hyperplasia; BSE, Boswellia serra extract; BVAS, Birmingham vascular activity score; CA 19–9, Carbohydrate antigen 19–9; CAL, Clinical attachment level; CAT, Catalase; CD40L, Cluster of differentiation 40 ligand; CD133, Cluster of differentiation 133; CDAI, Crohn’s disease activity index; CDSS, Calgary depression scale for schizophrenia; CEA, Carcinoembryonic antigen; CFU, Colony forming unit; CGI-I, Clinical global impressions-improvement score; CGI-S, Clinical global impressions-severity score; CGRP, Calcitonin gene related peptide; CK, Creatinine kinase; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; CK-MB, Creatinine kinase, MB fraction; CLDM, Curcumin liquid droplet micellar formulation; CLDQ, Chronic liver disease questionnaire; CMC, Consecutive menstrual cycle; Coll2–1, Serum type 2 collagen peptide; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COX-2, Cyclooxygenase 2; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CP, Curcumin phytosome formulation; CpAT, COPD assessment test; CRP, C-reactive protein; CRT, Central retinal thickness; CS, Standardized curcumin; CTR, Curcumin formulation with volatile oils of turmeric rhizome; CTx, C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen; Cu, Copper; CUA, Combined unique activity; Cur, Curcumin; CVD, cadiovascular disease; CXCl1, CXC motif chemokine ligand 1; DAS, Disease activity score; DASS-21, Depression, anxiety, stress scale-21; DB, Direct bilirubin; DBP, Diastolic blood pressure; dFLC, Difference between clonal and nonclonal free-light chain; DFP, Deferiprone; DLQI, Dermatology life quality index; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; DOMS, Delayed onset muscle soreness; DSPN, Diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy; EEG, Electroencephalogram; EGF, Epidermal growth factor; EPA, Eicosapentanoic acid; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FA, Fatty acid; FEV, Forced expiratory volume; FF score, Fibromyalgia and fatigue rating score; FFA, Free fatty acids; FDDNP, -(1-{6-[(2-[F-18]fluoroethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-naphthyl}ethylidene)malononitrile; FIHOA, Functional index for hand osteoarthritis; FLC, Free-light chain; FLI, fatty liver index; FLIP, FLICE inhibitory proteins; FMD, Brachial artery flow-mediated dilation; FOXP3, Forkhead box P3; FPG, Fasting plasma glucose; FPI, fasting plasma insulin; FSH, Follicular stimulating hormone; FSHD, Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy; FVC, Forced vital capacity; GGT, Gamma-glutamyl transferase; GI, Gingival index; GLA, Gamma linoleic acid; GM-CSF, Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; GOT, Glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase; GPT, Glutamate pyruvate transaminase; GPx, Glutathione peroxidase; GSH, Glutathione; GSK-3β, Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; GSRS, Gastrointestinal symptom rating scale; GTP, Guanosine triphosphate; H2O, Water; H2O2, Hydrogen peroxide; HAM/TSP, HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis; Hb, Hemoglobin; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; HDL, High density lipoprotein; HDL-C, HDL-cholesterol; HDR, Headache daily results; HIT-6, Headache impact test 6; HNC, Head and neck cancer; HOMA-β, Homeostatic model assessment for pancreatic beta cell function; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; hs-CRP, High-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HSC, Hematopoietic stem cell; HSI, Hepatic steatosis index; HTLV-1, Human lymphotropic virus type-1; IAPP; Islet amyloid polypeptide; IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, Inflammatory bowel syndrome; ICAM, Intracellular adhesion molecule; IgM, Immunoglobulin M; IFN, Interferon; iFLC, Involved free-light chain ratio; IFNγ, Interferon gamma; IIEF-5, 5-item version of the international index of erectile function; IL, Interleukin; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IPSS, International prostate symptom score; IPSS-S, International prostate symptom score-storage sub score; IPSS-V, International prostate symptom score-voiding sub score; IR, Insulin resistance; JKOM, Japanese knee osteoarthritis measure; JOA, Japanese orthopedic association, LAP, Lipid accumulation, product; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; LDL, Low density lipoprotein; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; LDLR, LDL receptor; LDSI, liver disease symptom index; LGMD, Limb girdle muscular dystrophy; LH, Leutinizing hormone; LNAA, Large neutral amino acids; LOS, Length of hospital stay; LPA, Lipoprotein A; LV, Left ventricular; MAFbx, Muscle atrophy F-box; ME/CSF, Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MDA, Malondialdehyde; MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorder Society sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; MELD, Model for end-stage liver disease; MetS, Metabolic syndrome; MGI, Modified gingival index; MHb, Methemoglobin; MI, Myocardial infarction; MIDAS, Migraine disability assessment; MIF, Monocyte inhibitory factor; miRNA, Micro RNA; MLH1, MutL homologue 1; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinase; MN, Micronuclei; MPO, Myeloperoxidase; MSM, Methylsulfonyl methane; MSH2, MutS homologue 2; MSQ, Migraine-specific quality of life; MVC, Maximal voluntary contraction; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; NAFLD, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NAIOS, Nutraceuticals with anti-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa B; NLC, Nanostructured lipid carriers; NMF, Natural moisturizing factor; NO, Nitric oxide; NO-adducts, Nitroso-adducts; NP, Nanoparticle; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; NTBI, Nontransferrin bound iron; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro hormone B-type natriuretic peptide; NUTRIC, Nutrition risk in critically ill; OLP, Oral lichen planus; OM, Oral mucositis; ORR, Objective response rate; OS, Overall survival; OSDI, Ocular surface disease index; OSE, Oxidative specific epitopes; OSF, Oral submucous fibrosis; PAB, Pro-oxidant antioxidant balance; PANSS, Positive and negative symptoms scale; PASI, Psoriasis area severity index; PBE, Pine bark extract; PBI, Papillary bleeding index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PCOS, Polycystic ovary syndrome; PCr/Pi, Phosphocreatine to inorganic phosphate ratio; PCS, P-cresyl sulfate; PCT, Procalcitonin; PD, Pocket depth; PDT, Photodynamic therapy; PFS, Progress free survival; PGC-1α, Peroxisome proliferator and activated γ receptor coactivator 1 alpha; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2; PI, Plaque index; PhK, Phosphorylase kinase; Pg, Porphyromonas gingivalis; PMS, Premenstrual syndrome; PPARγ, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PPBS, Postprandial blood sugar; PPD, Probing pocket depth; ppFEV1, Predicted forced expiratory volume in one second; PPFT, Periprostatic fat thickness; PON1, paraoxonase-1; PRL, Prolactin; PSA, Prostate-specific antigen; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; PSST, PMS screening tool; PTH, Parathyroid hormone; PV, Prostatic volume; Qmax, maximum flow rate; QoL, Quality of life; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index; RA, Rheumatoid arthritis; RAS, Recurrent aphthous stomatitis; REEDA, Redness, edema, ecchymosis, discharge, approximation; REU, Reticular erosive ulcerative score; RF, Rheumatoid factor; rFLC, Free-light chain ratio; RISR, Radiation induced skin reactions; ROM, Range of motion; RORγ t, Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor gamma; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; RT, radiotherapy; SBI, Sulcus bleeding index; SBP, Systolic blood pressure; SCCAI, Simple clinical colitis activity index; sCD40L, Cluster of differentiation 40 ligand; SGRQ, St. George respiratory questionnaire; SF-36, Short form healthy survey; SJC, Swelling joint count; SM, Sulfur-mustard; SMCs, Subjective memory complaints; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; SODA, Severity of dyspepsia assessment; SOFA, Sequential organ failure assessment; Sp, Substance P; SPEED, Standard patient evaluation of eye dryness; SRT, Selective reminding test; SSQOL, Stroke specific quality of life; sVCAM, Soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule; T2D, Type 2 diabetes mellitus; TAC, Total antioxidant capacity; TBARS, Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; TBUT, Tear-film breakup time; TBX21, T-box transcription factor 21; TC, Total cholesterol; TEWL, Transepidermal water loss; Tf, Tannerella forsythia; TG, Triglyceride; TGF-β, Transforming growth factor-beta; TIBC, Total iron binding capacity; TJC, Tender joint count; TLC, Total lymphocyte count; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; TN, Total nitrite; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor alpha; TRP, Tryptophan; TRR, Transferrin receptor; TURB, Transurethral resection of bladder; TURP, Transurethral resection of prostate; UGT, Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase; uDPYD, Urinary deoxypyridinoline; UIBC, Unsaturated iron-binding capacity; VAS, Visual analog scale; VCAM, Vascular cell adhesion molecule; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; VO2 max, Maximal oxygen consumption; WBC, White blood cells; WEC, Hot water extract; WPI; Whey protein isolate; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index; Zn, Zinc

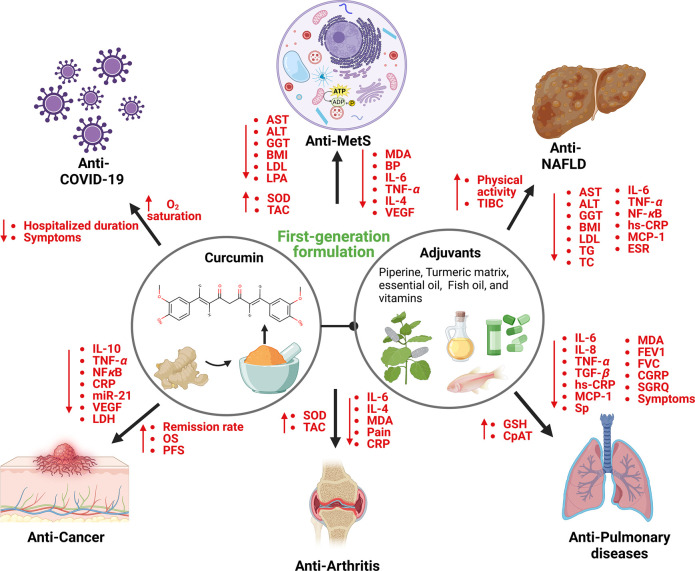

Figure 1.

Broad range of biological activities and molecular mechanisms of first-generation curcumin formulations. The first-generation formulations have shown excellent enhancement in the absorption and cellular uptake of curcumin. Various phase I/II clinical trials demonstrated that these formulations are effective against arthritis, cancer, COVID-19, MetS, NAFLD, and pulmonary diseases by modulating inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress-related molecules, liver enzymes, and lipid profiles. The figure was created using BioRender.com.

In patients with arsenic-induced oxidative stress, this formulation effectively decreased DNA damage, ROS generation, lipid peroxidation, and improved antioxidant capacity.71 In another study, the administration of curcumin (1.5 mg/day) and piperine (5 mg/day) for 2 months resulted in the efficient alleviation of IL-6 and improvement in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and asthma control test scores in bronchial asthma patients compared to those who received regular asthma drugs.72 Moreover, this formulation (1–1.5 g/day curcumin with 5 mg/day piperine) reduced the symptoms including weakness, dry cough, sore throat, sputum cough, ague muscular pain, headache, dyspnea, deterioration, and hospitalized duration in COVID-19 patients without side effects.73,74 Besides, the treatment with this formulation significantly improved mouth opening flexibility, cheek flexibility, and tongue protrusion capacity and suppressed burning sensation in oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) patients compared to placebo (starch and lactose capsules).75 In another randomized placebo-controlled trial, this formulation was shown to effectively augment GSH levels and decrease erythrocyte MDA levels in pancreatitis patients with no adverse side effects.76 In addition, it also reduced leptin and TNF-α levels and increased adiponectin levels in T2D patients over 12 weeks of treatment.77 Curcumin formulation with piperine and ginger ameliorated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), tender joint count (TJC), swelling joint count (SJC), disease activity score (DAS), and relieved pain and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients.78 Another study demonstrated that curcumin along with piperine and taurine remarkably suppressed IL-10, AST, ALT, α-L-fucosidase, and miR-21 levels and improved overall survival in hepatocellular cancer patients.79 Another curcumin/piperine tablet containing other ingredients including propranolol, aliskiren, cilazapril, celecoxib, aspirin, and metformin for 10 weeks enhanced the median survival rate in glioblastoma patients.80 This treatment was also found to be safe with minimal side effects including indigestion and marginal bradycardia (propranolol effect).80 Another study employed two tablets of curcumin–spirulina–Boswellia extract (each tablet with 400 mg curcumin, 50 mg spirulina, and 50 mg Boswellia extract) to patients with benign thyroid nodules and reported the reduced nodule area without adverse side events.81 Also, curcumin and fennel essential oil (FEO) tablets (2 capsules, a total of 84 mg curcumin with 50 mg FEO) caused substantial relief in symptoms and improved quality of life in inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS) patients.82 Moreover, the administration of three Oxy-Q tablets (each tablet containing 480 mg curcumin with 20 mg quercetin) repressed polyp size and number without side effects in familial adenomatous polyposis patients (FAP).83 In another study, a novel curcumin formulation administered as 2 capsules per day (each capsule containing 30 mg curcumin, 100 mg bovine lactoferrin, 15 mg zinc acetate, 100 mg lysolecithin), 600 mg N-acetylcysteine (NAC), and 20 mg pantoprazole inhibited serum pepsinogens, decreased disease severity and improved the cure rate in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori).84 In addition, rectal suppositories of 350 mg curcumin and 80 mg Calendula extract (1 suppository/die, for 1 month) significantly inhibited inflammation compared to those who received a placebo suppository (identical to treatment) without side effects.85 Yet another formulation, Curcumin Forte (95% curcumin plus 5% piperine formulation) remarkably increased positive and negative symptoms scale (PANSS) and reduced Calgary depression scale for schizophrenia (CDSS) scores in schizophrenic patients with no reported adverse side effects compared to identical colored and sized placebo tablets.86 Further, washing the mouth with curcumin and chitosan solution (10 mL) three times a day for 2 weeks inhibited Candida activity and achieved a complete response in 80% of denture stomatitis patients.87 In another study mouthwash containing essential oils and curcumin (MEC) effectively reduced ESR, rheumatoid factor (RF), CRP, anticitrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA), plaque index (PI), pocket depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL) and also was found to be well-tolerated in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with periodontitis.88