ABSTRACT

Negative-strand RNA viruses (NSVs) represent one of the most threatening groups of emerging viruses globally. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) is a highly pathogenic emerging virus that was initially reported in 2011 from China. Currently, no licensed vaccines or therapeutic agents have been approved for use against SFTSV. Here, L-type calcium channel blockers obtained from a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved compound library were identified as effective anti-SFTSV compounds. Manidipine, a representative L-type calcium channel blocker, restricted SFTSV genome replication and exhibited inhibitory effects against other NSVs. The result from the immunofluorescent assay suggested that manidipine inhibited SFTSV N-induced inclusion body formation, which is believed to be important for the virus genome replication. We have shown that calcium possesses at least two different roles in regulating SFTSV genome replication. Inhibition of calcineurin, the activation of which is triggered by calcium influx, using FK506 or cyclosporine was shown to reduce SFTSV production, suggesting the important role of calcium signaling on SFTSV genome replication. In addition, we showed that globular actin, the conversion of which is facilitated by calcium from filamentous actin (actin depolymerization), supports SFTSV genome replication. We also observed an increased survival rate and a reduction of viral load in the spleen in a lethal mouse model of SFTSV infections after manidipine treatment. Overall, these results provide information regarding the importance of calcium for NSV replication and may thereby contribute to the development of broad-scale protective therapies against pathogenic NSVs.

IMPORTANCE SFTS is an emerging infectious disease and has a high mortality rate of up to 30%. There are no licensed vaccines or antivirals against SFTS. In this article, L-type calcium channel blockers were identified as anti-SFTSV compounds through an FDA-approved compound library screen. Our results showed the involvement of L-type calcium channel as a common host factor for several different families of NSVs. The formation of an inclusion body, which is induced by SFTSV N, was inhibited by manidipine. Further experiments showed that SFTSV replication required the activation of calcineurin, a downstream effecter of the calcium channel. In addition, we identified that globular actin, the conversion of which is facilitated by calcium from filamentous actin, supports SFTSV genome replication. We also observed an increased survival rate in a lethal mouse model of SFTSV infection after manidipine treatment. These results facilitate both our understanding of the NSV replication mechanism and the development of novel anti-NSV treatment.

KEYWORDS: SFTSV

INTRODUCTION

Negative-strand RNA viruses (NSVs) represent one of the most threatening groups of emerging viruses for global human health. However, the initial symptoms are similar among different NSV infections, making it difficult for healthcare providers to select the proper treatments early. In general, viremia during the early stage of infection correlates with patient mortality. Therefore, broad-spectrum antivirals, which do not yet exist, could be an ideal primary option to treat NSV infections. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), an emerging infectious disease caused by the SFTS virus (SFTSV, SFTS phlebovirus, or Huaiyangshan banyangvirus), has a high mortality rate of up to 30% (1–3). SFTSV was originally reported in China in 2011 and previously classified into the genus Banyangvirus of the family Phenuiviridae, order Bunyavirales (1, 2). SFTSV, which is a tick-borne virus, has been detected not only in China but also in Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan (3–6). Other phleboviruses that are phylogenetically related to SFTSV, namely, Heartland virus and Malsoor virus, were isolated in the United States (Missouri) and western India, respectively (7, 8). Currently, the International Committee of Taxonomy Viruses recognizes SFTSV as Dabie bandavirus, and it belongs to genus Bandavirus of the family Phenuiviridae, order Bunyavirales.

The antiviral effects of ribavirin and interferons against SFTSV in vitro have been previously reported (9, 10). In addition, the efficacy of T-705, also known as favipiravir, against SFTSV replication was recently demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo (11). However, no effective vaccines or antiviral agents have yet been approved for the treatment of SFTSV infection.

Drug repurposing screens have recently emerged as an effective approach to accelerate drug development. This approach has led to the identification of potential novel candidate therapies for infections by Ebola (12, 13), hepatitis C (14), Zika (15), Japanese encephalitis (16), and Lassa viruses (17).

In this study, we aimed to identify the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved chemical compounds that can be applied in the clinic to treat patients with SFTS and found that L-type calcium channel blockers exhibited a significant anti-SFTSV effect. The antiviral effects of manidipine were not restricted to SFTSV alone but were also observed against other NSVs, including vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus (VSV; Indiana vesiculovirus, Rhabdoviridae), Hazara virus (HAZV; Hazara orthonairovirus, Nairoviridae), lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV; Arenaviridae), Junin virus (JUNV; Candid#1 strain, Arenaviridae), and influenza A virus (IAV; H3N2, Aichi, Orthomyxoviridae). Formation of the inclusion body, which is induced by SFTSV N and known to facilitate viral genome replication, was inhibited by the manidipine. Inhibiting the activation of calcineurin, which is located downstream of the calcium signaling pathway, using tacrolimus (FK506) or cyclosporine (CysA), reduced the propagation of SFTSV. Furthermore, we found that globular (G) actin, the conversion of which is regulated by cations including calcium from filamentous actin (actin depolymerization) (18–20), supports SFTSV genome replication. Finally, we observed an increased survival rate in a lethal mouse model of SFTSV infection after manidipine treatment. Given that some of the compounds tested in this study have already been approved for clinical use, they may represent effective primary options for treating such NSV infections. The results shown in this study also enhance our understanding of the replication and propagation mechanisms of NSVs and may assist in the development of novel anti-NSV therapeutic agents.

RESULTS

Screening of an FDA-approved compound library to identify anti-SFTSV compounds.

To identify effective anti-SFTSV drugs, an FDA-approved compound library was examined. SW13 cells, which strongly support SFTSV replication and propagation, were seeded onto 96-well plates. The following day, the cells were infected with SFTSV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, and the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing 20 μg/mL of each compound at 1.5 h postinfection (h p.i.) (Fig. 1A). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as a control on both sides of the 96-well plates (Fig. 1A). At 48 h p.i., the infected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After the blocking treatment and permeabilization of the cells, staining with SFTSV N antibody and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody was performed, as described in Materials and Methods. All wells were observed and images were captured using a laser confocal microscope. SFTSV N-positive cells were counted manually. The mean number of N-positive cells among the DMSO-treated wells was assigned a value of 1, and the relative number of N-positive cells in each other treatment group was calculated. The same treatment procedures, but without SFTSV infection, were performed to examine the viability of the cells upon treatment with the test compounds. The relative numbers of N-positive cells and cell viability data are illustrated in Fig. S1 in the supplemental materials. Among 635 compounds, 27 were selected as positive for anti-SFTSV activity (<30% N-positive cells and >70% cell viability, compared with the DMSO-treated wells) (Fig. 1B and Table S1). Among the positive compounds, six were L-type calcium channel blockers (nicardipine, manidipine, nisoldipine, felodipine, cilnidipine, and flunarizine) (Fig. 1C). Although our experiments revealed several compounds with inhibitory effects against SFTSV replication, including monoamine blockers and ligands for nuclear receptors, we focused on the L-type calcium channel blockers in this study. To assess the inhibitory effect of the SFTSV N expression by the L-type calcium channel blockers, manidipine, one of the representative L-type calcium channel blockers, was selected. The SFTSV N expression by the virus infection upon treatment with DMSO, manidipine, or nifedipine, another L-type calcium channel blocker and not included in our compound library, was examined by Western blotting (WB). The band intensities of the SFTSV N were measured and quantified. Manidipine treatment reduced the SFTSV N expression significantly, while nifedipine only partially reduced the SFTSV N expression (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Identification of L-type calcium blockers as inhibitors for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV). (A) Schematic representation of the screening method. (B) Among the 635 screened compounds from a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved compound library, 27 were selected as positive for anti-SFTSV activity. The cutoff criteria for selection were a 70% inhibitory effect of SFTSV replication (<30% N-positive cells) and 30% cell toxicity (>70% cell viability) compared with the control dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatment. (C) Selected images captured from the initial screening. Each of the L-type calcium channel blockers was administered at 20 μg/mL to SFTSV-infected SW13 cells at 1.5 h postinfection (h p.i.). At 48 h p.i., the cells were fixed and stained with an anti-SFTSV N antibody. (D) SFTSV N expression was detected by Western blotting (WB). SFTSV-infected SW13 cells were treated with DMSO, manidipine (mani; 10 and 20 μg/mL), or nifedipine (nife; 20 and 100 μg/mL). At 48 h p.i., cell lysate was collected, performed SDS-PAGE, followed by WB to detect SFTSV N (left, representative figure). Band intensities were measured and the relative N expression was shown (right, DMSO treatment was set as 1.0). The expression of actin was shown as a loading control. The data shown here are representative of four independent experiments.

Next, we examined the effects of manidipine on the growth of SFTSV. Manidipine treatment (20 μg/mL = 30 μM) resulted in a significant reduction of SFTSV production in SW13 cells at 24 (2 logs) and 48 (3 logs) h p.i. compared with the control DMSO treatment (Fig. 2A). There was no significant cytotoxic effect on the manidipine-treated cells at 48 h posttreatment (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the cell-type dependency of this reduction of SFTSV production by manidipine, Huh-7 cells were infected with SFTSV and treated with manidipine (Fig. S2). Both 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of SFTSV production and 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of manidipine in SW13 and Huh-7 cells were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the selectivity index (SI; CC50/IC50) was also calculated (Fig. S2). IC50 and CC50 in SW13 cells were 2.83 and 57.03 μM, respectively. IC50 and CC50 in Huh-7 cells were 3.17 and 28.2 μM, respectively. Therefore, the SI of manidipine in SW13 and Huh-7 cell lines were 20.15 and 8.19, respectively (Fig. S2). Next, a fluorescent calcium indicator was used to examine if the manidipine treatment in our study reflected the calcium influx (Fig. S3). Inhibition of calcium influx was not observed at 1 μg/mL of manidipine treatments. In contrast, the treatment from 3 to 20 μg/mL of manidipine reduced calcium influx. Taken together, these results confirmed our screening result that manidipine inhibited the replication and propagation of SFTSV by inhibiting the calcium influx.

FIG 2.

(A) Effect of manidipine (20 μg/mL) on severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) propagation in SW13 cells. Viral titers in culture media were determined at 0, 24, and 48 h p.i. L.O.D., limit of detection. (B) SW13 cells were treated with 0 (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] control), 10, or 20 μg/mL manidipine. At 48 h posttreatment, the cell viability was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The data are averages and standard deviations from four independent experiments. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student's t test (***, P < 0.001).

To further confirm if the effect we observed by manidipine was calcium influx dependent or not, we examined if calcium ionophores rescue the virus production that is reduced by manidipine treatment. Manidipine (5 μM) treatment reduced SFTSV production about 3-fold compared to DMSO treatment. Ionomycin (1 μM) treatment without manidipine treatment did not affect SFTSV production, and 1 μM ionomycin rescued the reduction caused by the manidipine treatment (Fig. S4).

Next, to compare the anti-SFTSV effect with the previously reported broad-spectrum antiviral T-705 (favipiravir), Huh-7 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 and then treated with several doses of either manidipine or T-705 (11). At 48 h p.i., culture media were collected to measure each viral titer (Fig. 3). In all of the tested doses of the compounds, manidipine showed a higher anti-SFTSV effect compared to T-705. The IC50 was also calculated for T-705 (5.62 μM) and is shown together with that of manidipine (Fig. 3; Fig. S2; 3.17 μM).

FIG 3.

Comparison of the anti-severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) effect between T-705 and manidipine. Huh-7 cells were infected with SFTSV at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 and treated with the indicated concentration (0, 1, 5, or 20 μM) of either T-705 or manidipine. At 48 h postinfection, the culture supernatant was used to measure the viral titer. The data are averages and standard deviations of four independent experiments. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student's t test (*, P < 0.05). The 50% inhibitory concentrations of T-705 and manidipine were calculated and shown on the right side of the figure.

Manidipine affected SFTSV replication at a postentry step.

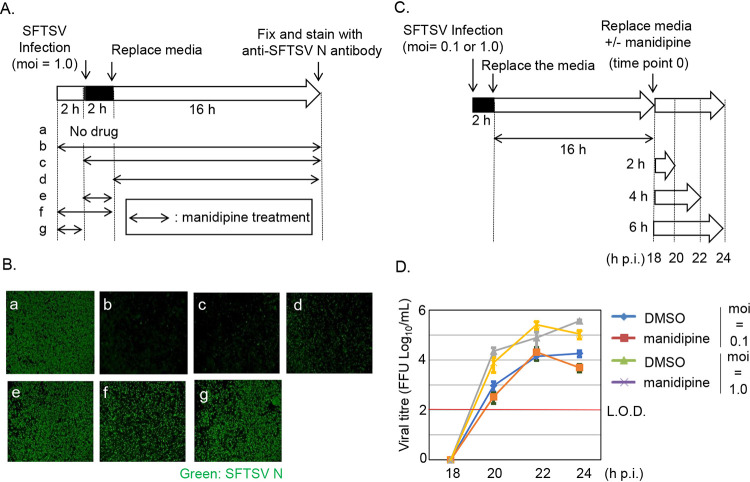

Next, we ruled out targets of manidipine. For this purpose, a time course infection assay was performed (Fig. 4A). It was reported that the fusion events of the SFTSV at the entry occur at 15 to 60 min postentry (21). Also, the expression of N in SW13 cells could be detected by WB from 20 h p.i. (Fig. S5) Based on this report and our observations, SW13 cells were treated with manidipine at various combinations of time points (preentry [2 h], during-entry [2 h], and postentry [16 h]). All of the infected cells (MOI = 1.0) were fixed at 18 h p.i., and the number of SFTSV N-positive cells was determined (Fig. 4B). In SW13 cells, manidipine treatments at a postentry step (Fig. 4Bb to d) significantly reduced the number of N-positive cells compared with DMSO treatment (Fig. 4Ba). In contrast, preentry and/or during-entry manidipine treatments (Fig. 4Be to g) slightly reduced the number of N-positive cells. Since the anti-SFTSV effect of manidipine was more significant in the postentry step than in the preentry and during-entry steps, we focused on the manidipine effect in the postentry step here.

FIG 4.

A time-course assay of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) infection revealed that manidipine targets replication of SFTSV at a postentry step. (A) Illustration of the manidipine treatment combinations (a to g) used for examining the viral replication steps targeted by manidipine. Manidipine was administered at various combinations of the three time points of preentry (2 h), during-entry (2 h [1 h at 4°C and 1 h at 37°C]), and postentry (16 h). The application of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) throughout the experimental period was used as a control. Cells were infected with SFTSV at a multiplicity of infection of 1.0. (Ba to g) The cells were fixed at 18 h postinfection (h p.i.), stained with an anti-SFTSV N antibody, and then observed under a fluorescence microscope. (C) Illustration of the experimental procedure for examining the effect of manidipine on SFTSV release. SFTSV was allowed to replicate in SW13 cells for 18 h. At 18 h p.i., the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or 20 μg/mL manidipine. At 18, 20, 22, and 24 h p.i., samples of the culture media were collected for measurements of the viral titers. SFTSV was administered at two doses (MOI = 0.1 and 1). (D) The viral titer from each time point was normalized by deducting the titer at 18 h p.i. to compare the virion production in the presence of each compound. L.O.D., limit of detection. The data are averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Manidipine did not affect the release of SFTSV from the host cells.

We further examined the effect of manidipine on SFTSV release from the infected cells. After 2 h of infection with two different doses of SFTSV (MOI = 0.1 and 1), the culture media were replaced with fresh media and incubated for an additional 16 h to permit a single cycle of replication. The culture media were then replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL). The time at which the media were replaced was assigned as time point 0 (18 h p.i.). Culture media from 2, 4, and 6 h after media replacement (20, 22, and 24 h p.i., respectively) were collected, and their viral titers were measured together with the media from “time point 0” (Fig. 4C). Each viral titer was plotted on a graph after normalization by deducting the titer at time point 0 (Fig. 4D). For both doses of virus (MOI = 0.1 and 1), no apparent reduction in the release of infectious viral particles was observed with manidipine treatment. In a similar experiment, the culture supernatant was collected at 12 h posttreatment (30 h p.i.) and examined the effect of manidipine after a longer incubation time (>6 h) (Fig. S6A). Consistent with the results shown in Fig. 4D, there was no significant difference on viral production between cells treated with DMSO or manidipine (Fig. S6B).

Manidipine reduced the genome replication of SFTSV.

To further explore the mechanism underlying the effect of manidipine on the replication of SFTSV, reverse transcription real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed. SW13 cells were infected with SFTSV at an MOI of 1.0 and incubated for 1.5 h. After the incubation period, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL). The infected cells were further incubated for 17 h. RNA was isolated from the SFTSV-infected cells at 1.5 and 18.5 h p.i., as described in Materials and Methods. Using a biotinylated primer, the isolated RNA was used to generate cDNA, which was then purified using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. The purified cDNA was then used for qPCR. As shown in Fig. 5A, manidipine treatment significantly reduced the viral RNA production at 18.5 h p.i. to a level similar to that at 1.5 h p.i. This result was further supported by the quantification of SFTSV N expression at 18.5 h p.i. (Fig. 5B). Although SFTSV N could be detected with the DMSO treatment, its expression was below the detection limit when treated with either 10 or 20 mg/mL manidipine (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Manidipine reduced the genome replication of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV). (A) SW13 cells were infected with SFTSV, and at 1.5 h postinfection (h p.i.), the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or manidipine (20 μg/mL) and then incubated for a further 17 h (18.5 h p.i.). At 1.5 and 18.5 h p.i., cellular RNA was collected, and a reverse transcription reaction was performed with the biotinylated primer. The cDNA was then purified using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and used as a template for qPCR. The copy number of SFTSV vRNA from 1.5 h p.i. was assigned a value of 1, and the relative copy number at 18.5 h was indicated for each treatment. (B) Infection and treatment were performed as described in panel A except using two manidipine doses (10 and 20 μg/mL). Cell lysate was collected to perform Western blotting to detect SFTSV N (left). The band intensities were measured and quantified, and DMSO treatment was set at 1.0. Relative band intensities were shown (right). The data are averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student's t test (***, P < 0.001).

Effect of manidipine on the propagation of other NSVs.

We clearly showed that manidipine significantly inhibited the propagation of SFTSV (Fig. 2A). We further examined whether this inhibitory effect was restricted to SFTSV or whether manidipine can also target other NSVs. SW13 cells were infected with VSV (Fig. 6A), HAZV (Fig. 6B), LCMV (Fig. 6C), or JUNV (Fig. 6D). In addition, MDCK cells were also infected with IAV (Fig. 6E). At 1.5 h p.i., the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine (10 or 20 μg/mL). Viral production was measured at 0, 24, and 48 h p.i. (only 24 and 48 h p.i. for IAV and JUNV, respectively). Consistent with the outcome for SFTSV, manidipine reduced the production of VSV by 1 log (Fig. 6A), HAZV by 1 log (Fig. 6B), LCMV by 1.5 logs (Fig. 6C), and IAV by 2 logs (Fig. 6E) at 24 h p.i. and significantly reduced that of VSV by 1.5 logs (Fig. 6A), HAZV by 1.5 logs (Fig. 6B), LCMV by 3 logs (Fig. 6C), and JUNV by 2 logs (Fig. 6D) at 48 h p.i.

FIG 6.

Effects of manidipine on the growth of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV; A), Hazara virus (HAZV; B), lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV; C), Junin virus (JUNV; D), and influenza A (H3N2; E) virus. Each virus was administered to SW13 or MDCK cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. At 1.5 h postinfection, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 20 μg/mL manidipine. At 0, 24, and 48 h postinfection (h p.i). (for the JUNV Candid#1 strain and influenza A virus, only 48 and 24 h p.i., respectively), samples of the culture media were collected for measurements of the viral titer. L.O.D., limit of detection. The data are averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student's t test (***, P < 0.001).

Manidipine suppressed the replication of LCMV at a postentry step and the cytopathic effect of VSV.

Manidipine treatment not only reduced the production of SFTSV but also suppressed that of other viruses, including VSV and LCMV (Fig. 6). Our results suggested that manidipine mainly targets the replication of SFTSV at a postentry step (Fig. 4). To examine whether manidipine inhibits the replication of other NSVs at the same step, SW13 cells were infected with two different doses of LCMV (MOI = 1 or 5), and at 2 h p.i., the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL) and incubated for a further 16 h to allow single-cycle infection (22–24). The cells were subsequently fixed and then stained with a LCMV NP antibody (Fig. 7A). At both MOIs, manidipine treatment significantly reduced NP expression (Fig. 7B). SW13 cells were also infected with VSV, and at 1 h p.i., the media were replaced with or without manidipine (20 μg/mL), and the cells were incubated for a further 7 h and then fixed. The fixed cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to assess the cells that were viable (Fig. 7C). VSV-infected DMSO-treated cells showed clear cytopathic effects owing to VSV replication, whereas VSV-infected manidipine-treated cells showed less severe cytopathic effects (Fig. 7D). These qualitative results indicated that manidipine reduced the replication of LCMV at the steps from postentry to viral protein translation and suppressed the replication-dependent cytopathic effect of VSV.

FIG 7.

Manidipine inhibited the replication of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). (A) Schematic representation of the LCMV infection experiment. SW13 cells were infected with LCMV at either a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 or 5. At 2 h postinfection (h p.i.), the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or manidipine (20 μg/mL), and the cells were incubated for an additional 16 h and then fixed. LCMV-infected cells were detected using an anti-LCMV NP antibody. (B) Capture of the fluorescent image of the LCMV-infected cells stained with anti-LCMV NP and DAPI. (C) Schematic representation of the VSV infection experiment. SW13 cells were infected with VSV at MOI = 1. At 1 h p.i., culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL), and the cells were incubated for 7 h and then fixed. The fixed cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (D) Capture of the light field image of VSV-infected cells. The data shown here are representative of three independent experiments.

SFTSV N-induced inclusion body formation was inhibited by the manidipine treatment.

To elucidate how manidipine affects the SFTSV genome replication, we focused on the inclusion body (IB) that is formed by the SFTSV-N and is known to be important for efficient viral genome replication (25). Huh-7 cells were transfected with SFTSV-N expression plasmid and then treated with either DMSO or manidipine. Immunofluorescent staining of the SFTSV N exhibited that the N forms the IB with the DMSO control treatment. In contrast, IB formation was hardly detected but rather distributed throughout the cytoplasm with the manidipine treatment (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Manidipine treatment interfered SFTSV N-induced inclusion body (IB) formation. Huh-7 cells were transfected with SFTSV N expression plasmid and treated with either DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL). At 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed and stained with anti-SFTSV N antibody, followed by staining the second antibody. DAPI was stained to recognize nuclei. Samples were observed and figures were captured using a laser scanning microscope (LSM; Zeiss). Bar = 20 μm.

Calcineurin is involved in SFTSV production.

The concentration of calcium in the cytoplasm is lower than that outside the cell. The entry of calcium into the cell through membrane receptors or channels results in the activation of calcineurin (26). Activated calcineurin dephosphorylates NFAT proteins, leading to their entry into the nucleus. In the nucleus, NFAT proteins assemble on DNA and induce gene transcription, including that of several cytokines. To examine the role of calcineurin, which is a downstream factor of the L-type calcium channel, on SFTSV propagation, two chemical compounds that inhibit calcineurin function, namely, FK506 and cyclosporine (CysA), were used. CysA was identified as having an anti-SFTSV activity from our initial screen (Table S1). SW13 cells were infected with SFTSV at an MOI of 0.1, and the media were replaced with fresh media containing FK506 (20 μM) and CysA (10 μg/mL [8.3 μM]). At 0, 24, and 48 h p.i., the viral titers were measured in the culture supernatant (Fig. 9A). CysA at 10 μg/mL and FK506 at 20 μM significantly reduced SFTSV production compared with DMSO treatment. To confirm that these effects were not caused by cytotoxicity, the viability of SW13 cells in the presence of FK506 and CysA was measured. The concentrations of these agents used in the study did not affect the viability of SW13 cells (Fig. 9B).

FIG 9.

FK506 and cyclosporine (CysA) inhibited severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) propagation. (A) SW13 cells were infected with SFTSV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 and treated with FK506 or CysA at the indicated concentrations. Viral titers measured at 0, 24, and 48 h p.i. are indicated. (B) The viability of the SW13 cells upon treatment with the indicated compounds is indicated (24 and 48 h posttreatment). The control dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatment was assigned a value of 1. L.O.D., limit of detection. The data are averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student’s t test (***, P < 0.001).

Globular (G)-actin supports SFTSV replication.

As shown in Fig. 9A, calcium-mediated calcineurin activation, followed by the activation of several transcription factors, seems to be involved in this process. To further explore the involvement of calcium in SFTSV replication, we focused on actin, since calcium was reported to be involved in actin depolymerization (18–20, 27). In general, actin presents as either a free monomer called globular (G)-actin or as part of a linear polymer microfilament called filamentous (F)-actin. In cells, G-actin polymerizes to form F-actin, an essential element of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, and F-actin could easily release G-actin from the end (Fig. S8A). Several cellular components are known to promote actin depolymerization, including divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) (Fig. S8A) (18–20, 27). First, we examined if dsRNA produced by SFTSV genome replication could colocalize with either G-actin or F-actin and assessed this point qualitatively by the immunofluorescent assay. Huh-7 cells were infected with SFTSV and fixed at 48 h p.i. Fixed cells were stained with anti-dsRNA antibodies and G-actin- or F-actin (phalloidin)-specific antibodies. As shown in Fig. 10A, SFTSV dsRNA colocalized with G-actin but not with F-actin. Next, we examined if actin-polymerization inhibitors (latrunculin A [Lat A] and cytochalasin D [Cyt D]) affect SFTSV replication. Huh-7 cells were infected with SFTSV, and media were replaced with compound-containing fresh media at 1.5 h p.i. to allow us to examine these compounds on virus replication/transcription but not a viral entry step. Infected cells were incubated for 16 h and then fixed and stained with anti-SFTSV N antibody. Although we did not observe the reduction of SFTSV N-positive cell number, brighter foci were observed in SFTSV N-positive cells treated with actin-polymerization inhibitors compared to that of DMSO control cells (Fig. 10B). To quantify if these actin-polymerization inhibitors facilitate SFTSV genome replication, SFTSV minigenome (MG) system was established as described in Materials and Methods. The MG system totally relies on the plasmid transfection, and we found that Cyt D and manidipine treatments significantly reduced transfection-based protein expression levels (Fig. S8D) with modest cell toxicity (Fig. S8B). Therefore, Cyt D and manidipine treatments were excluded from the MG assay. Lat A treatment significantly increased MG replication (4.5 times). Mycalolide B (Myc B), which stabilizes G-actin, was also used to confirm our observation. Myc B treatment also increased MG replication (2.3 times) but to a lesser extent compared to Lat A. To further confirm that calcium-mediated actin depolymerization is involved in SFTSV replication, an actin mutant plasmid was constructed. Asp11 (D10), Gln136 (Q136), and Asp153 (D153) of actin are known to be key amino acids to capture divalent cations and maintain the structure of actin (28). Two Asp (D) and Gln (Q) were mutated to Val (V) and Leu (L) in HA-tagged actin expressing plasmid as D10, D153V, and Q136L, respectively. Huh-7 cells were transfected with SFTSV MG plasmid cassette with actin-WT, mutant plasmids, together with firefly luciferase (Fluc) encoding plasmid as a transfection control plasmid. As shown in Fig. 10D, overexpression of Q136L, D10, and D153V increased MG expression 8-fold and 4-fold compared to WT overexpression, respectively.

FIG 10.

Globular (G)-actin supports SFTSV genome replication. (A) SFTSV dsRNA colocalizes with G-actin but not with filamentous (F)-actin. Huh-7 cells were infected with SFTSV and fixed at 48 h p.i. Fixed cells were stained with anti-dsRNA antibody, DAPI, and either G-actin or F-actin-specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Bar = 20 μm. (B) Huh-7 cells were infected with SFTSV. At 1 h p.i., culture media were replaced with DMSO, Lat A, or Cyt D containing media. At 16 h p.i., cells were fixed and stained with anti-SFTSV N antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated second antibody. Images were captured with the same condition. (C) Huh-7 cells were transfected with the SFTSV minigenome (MG) plasmid cassette, together with firefly expressing control plasmid (pGL4.54). At 6 h posttransfection (h p.t.), media were replaced with DMSO-, Lat A-, or Myc B-containing media. At 48 h p.t., Dual-Glo luciferase assay was performed to detect both Rluc and Fluc. Relative ratio (Rluc/Fluc) was shown in the graph. ED Huh-7 cells were transfected with SFTSV MG plasmid cassette and pGL4.54 together with empty (control), actin-WT, or actin-Mut. plasmids, respectively. At 48 h p.t., Dual-Glo luciferase assay was performed as described above. Relative ratio (Rluc/Fluc) was shown in the graph. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Manidipine treatment increased survival rate in a lethal animal model of SFTSV infection.

We and others have reported that SFTSV causes a lethal infection in type-I interferon receptor knockout (IFNAR−/−) mice (11, 29, 30). Therefore, we used this model to examine the in vivo effect of manidipine on SFTSV infections. The IFNAR−/− mice were subcutaneously injected with 10 fluorescent focus units (FFU) of SFTSV. 10 mg/kg of manidipine or PBS-T (control) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) twice per day on days 4 and 5 p.i. A modest, but statistically significant, increase in the survival rate was observed upon manidipine treatment (Fig. 11A). Experiment with the same condition was performed to measure viral titers in the spleen, kidney, serum, and liver at day 7 p.i. Viral titers in the spleen (Fig. 11B) and kidney (Fig. S9A) were significantly reduced upon the manidipine treatment. On the other hand, viral titers in the serum (Fig. S9B) and liver (Fig. S9C) were not affected by the manidipine treatment. In the case of the T-705 treatment with the same procedure (10 mg/kg, twice per day on days 4 and 5, i.p. injection), similar protection efficiency was observed (Fig. S10).

FIG 11.

Manidipine treatment prolonged survival in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV)-infected mice. (A) IFNAR−/− mice in each group were inoculated subcutaneously with 10 PFU of SFTSV (YG1). Mice were treated with PBS-T or manidipine at a dose 10 mg/kg, twice per day on days 4 and 5 p.i. (shaded in gray with the survival curves). Survival analysis was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test to compare the manidipine-treated mice to control-treated mice. (B) IFNAR−/− mice in each group were subcutaneously inoculated with 10 PFU of SFTSV (YG1). Mice were treated with PBS-T or manidipine at a dose of 10 mg/kg, twice per day on days 4 and 5 p.i. At day 7 p.i., mice were euthanized and the spleen was collected to measure viral titers. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by the Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

NSVs can result in asymptomatic cases to severe illness upon infection. Humans have limited options for prophylaxis and treatment against these viral infections. One approach for developing antivirals is to understand the molecular mechanism of viral replication in infected cells and to develop drugs targeting the identified process. However, the disadvantage of this approach is the long period between the identification of the drug targets and treatments for use in the clinic. Another approach is drug repurposing screening, which has recently been recognized as an effective approach to reevaluate chemical compounds that are currently used in the clinic for other purposes. This approach has been already used to identify compounds with activities against Ebola (12, 13), hepatitis C (14), Zika (15), Japanese encephalitis (16), and Lassa virus infections (17).

In this study, we performed a drug repurposing screen using an FDA-approved chemical compound library. Recently, a similar approach was used to identify several anti-SFTSV compounds (31–35). In this study, the L-type calcium channel blocker manidipine was identified as an SFTSV inhibitor and its underlying mechanism was partially revealed. The effect of manidipine on SFTSV replication was not cell-type dependent, since both SW13 and Huh-7 cell lines showed approximately the same IC50 against SFTSV production (2.83 and 3.17 μM, respectively) (Fig. S2). A similar observation was reported from another group (32). Consistent with their findings, we revealed that a postentry step of SFTSV is the major target of manidipine. Manidipine treatment also affects to pre- and during-entry step of SFTSV infection modestly (Fig. 4). We further found that the antiviral effect of manidipine was not restricted to SFTSV, since it also targeted other NSVs, including VSV, HAZV, LCMV, and JUNV. Notably, manidipine also reduced IAV production, of which the viral genome replicates inside the nucleus, rather than inside the cytoplasm as with SFTSV (Fig. 6). In the cases of LCMV, our results showed that manidipine also affected the postentry step within the host cells (Fig. 7B). Since these results were not quantitative but only qualitative, more precise experiments should examine manidipine’s target against these viruses’ replication. The reduction of SFTSV production by manidipine treatment was rescued by the addition of ionomycin, one of an ionophore, suggesting the restriction of SFTSV production by manidipine was due to the inhibition of the calcium influx through the L-type calcium channel (Fig. S4).

Calcium affects nearly every aspect of cellular life (36). Among these broad roles, the calcium signaling pathway is a well-characterized regulator of developmental events and immune responses (37, 38). The relation between the viral life cycle and calcium signaling in host cells has been recently documented for some viruses, including the Ebola and Marburg viruses (Filoviridae) (39, 40), human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1; Retroviridae) (41), and Lassa virus and JUNV (Arenaviridae) (39). Endosomal calcium channels, which are two-pore channels, were reported to be involved in filovirus entry (40). Calcium provided from the endoplasmic reticulum through the 1,4,5-inositol trisphosphate receptor is important for HIV-1 Gag assembly and release (41). ORAI1 and its stimulator, STIM1, have been reported to be involved in the production of hemorrhagic fever viruses (39). These previous reports and our findings showed that calcium has an impact on nearly all of the viral life cycle events, including entry, replication, and release, but it affects each of those processes in a different way. One could speculate that an L-type calcium channel blocker might induce an innate immune response to inhibit NSV replication. However, manidipine treatment preentry and/or during-entry did not significantly reduce the number of SFTSV N-positive cells in our time course infection assay (Fig. 4). This result suggested that the induction of specific host gene expression, including innate immunity-related gene expression, which could inhibit the SFTSV replication and following N expression with a 2-h treatment before the infection was not the major mechanism underlying the antiviral effect of manidipine. In addition, using FK506 and CysA, which bind to the intracellular proteins FKBP and cyclophilin, respectively, to inhibit the calcium signaling pathway, we showed that these two chemical compounds significantly reduced SFTSV production without inducing cytotoxicity (Fig. 9B). Both manidipine and CysA inhibited the NFAT activity upon ionomycin and PMA stimulation (Fig. S7A). These results indicated that the calcium signaling pathway including the NFAT activity might be involved in the replication and propagation of SFTSV. NF-κB, which is also a downstream factor of the calcium signaling pathway, was reported to be involved in the SFTSV replication (42). This suggests that the inhibition of the NF-κB by the manidipine treatment might be one of the mechanisms of the anti-SFTSV activity by the manidipine treatment. Importantly, the L-type calcium channel blocker manidipine, as well as the calcium signaling inhibitors FK506 and CysA, have all been already used as medications, which strongly suggests that these compounds could be applied to SFTS patients in the clinic faster than the time required for the normal drug development process. Especially, 1 μg/mL of CysA, which is less than the maximum concentration by the i.v. injection (~1.5 μg/mL) used in the clinic, reduced SFTSV production significantly (Fig. S7B).

In addition to the role of calcium signaling on SFTSV replication, we also revealed the role of G-actin, the formation of which is facilitated by calcium, on SFTSV genome replication. Actin presents as either a free monomer called G-actin or as part of a linear polymer microfilament called F-actin. In cells, G-actin polymerizes to form F-actin, an essential element of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, and F-actin could easily release G-actin from the end (Fig. S9A). Several cellular components are known to regulate actin polymerization and depolymerization, including divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) (Fig. S9A). Three amino acids in actin (D10, Q136, and D153) are known to be important to capture these divalent cations (43). First of all, we examined if either G-actin or F-actin could colocalize with dsRNA, which is produced by SFTSV replication, and found that G-actin, but not F-actin, colocalized with SFTSV dsRNA (Fig. 10A). We also observed that two actin polymerization inhibitors (Lat A and Cyt D) enhanced the brightness, but not the number of positive cells, of SFTSV N-specific antibody specific foci in the cell, when the treatment was conducted after the virus entry step (Fig. 10B). To quantify this observation, SFTSV MG assay was established (Fig. S8C) and the effect of Lat A, together with Myc B, which stabilizes G-actin, on SFTSV genome replication was examined. The MG system can be used as a surrogate system to analyze the virus replication, transcription, and translation, which could be measured with the reporter gene expression. As shown in Fig. 10C, inhibiting actin-polymerization and stabilizing G-actin promoted SFTSV MG replication, indicating the important role of G-actin on SFTSV genome replication. To further explore the role of calcium in this process, an actin-mutant (Q136L, D10, and D153V) plasmid was constructed and the effect on SFTSV MG replication was examined. As shown in Fig. 10D, the overexpression of actin-mutants, which reduced the holding capability of divalent cations, increased SFTSV MG expression. These results indicated that G-actin, which captures calcium ion, supports SFTSV genome replication. In contrast, overexpression of the divalent cation binding mutants of actin (D10V, Q136L, or D153V) reduced the transcription activity of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), currently known as human orthopneumovirus, genus Orthopneumovirus, family Pneumoviridae, order Mononegavirales (44). It was reported that the intracellular transport of SFTSV-carrying endocytic vesicles is dependent on actin filaments at the cell periphery and then on microtubles toward the cell interior (21). Accordingly, cytochalasin D-mediated inhibition of actin filament elongation was shown to interfere with SFTSV infection (21). It is possible that the SFTSV N-induced IB formation, which was aborted by the manidipine treatment (Fig. 8), is G-actin dependent. Based on these observations, it might be interesting to investigate more precisely the difference of the actin requirements among other NS RNA viruses and also among the different steps of the virus replication, including the role of actin on the IB formation.

We also compared the anti-SFTSV effect of manidipine with the broad-spectrum antiviral compound T-705 and found that manidipine showed a stronger anti-SFTSV effect than T-705 at the same concentration (Fig. 3; manidipine, IC50: 3.17 μM; T-705 IC50, 5.62 μM). It has been reported that IC50 and IC90 of T-705 in Vero cells were 6 and 22 μM, respectively, suggesting that the anti-SFTSV effect of T-705 in Huh-7 cells was similar to Vero cells (Fig. 3) (11). In contrast, the administration of T-705 protected SFTSV-infected IFNAR−/− mice (11), while manidipine treatment slightly increased their survival rate, but with statistical significance (Fig. 11A). It should be noted that when T-705 was administered with the same dose and condition with manidipine in this study, the survival rate between manidipine and T-705 was equivalent (Fig. 11 and Fig. S10). This result also provides the information that 10 mg/kg (twice per day on days 4 and 5) of T-705 administration could exhibit a protective effect against the SFTSV infection in mice. Although the exact mechanisms of the lethality and pathogenicity of SFTSV have not been revealed, the viral titers in the spleen (Fig. 11B) and kidney (Fig. S9A) were significantly reduced upon manidipine treatment at day 7 p.i. This reduction of viral load in the spleen and kidney might explain the increase in the survival rate with the manidipine treatment upon SFTSV infection (Fig. 11A). On the other hand, viral titers in serum and liver were not affected upon manidipine treatment (Fig. S9B and S9C). It is worth noting that the viral titer in the serum became below the detection limit when measured just before the mice died (day 8 p.i., data not shown), which corresponded to previous reports (11, 30). We are currently investigating the reason for the virus elimination from the serum at the late stage of the infection. Since the anti-SFTSV mechanism seems to be different between manidipine and T-705, it might be possible to use both T-705 and manidipine to obtain additive or synergic anti-SFTSV effects. In addition, the coadministration of each compound at lower doses would reduce the side effects of the compounds. Although it is not clear if T-705- and manidipine-resistant viruses could appear, recent studies showed the appearances of manidipine-resistant Japanese encephalitis virus (16) and T-705-resistant Chikungunya, influenza, and Junin viruses (45–47). Therefore, administration of more than two antivirals, which possess different modes of action, would reduce the possibility of drug-resistant viruses. Recently, Li et al. (32) conducted and reported a retrospective clinical investigation among more than 2,000 SFTS patients and found that administration of calcium channel blocker (nifedipine) enhanced virus clearance, improved clinical recovery, and reduced the case fatality rate by more than 5-fold. These findings strongly supported our findings that calcium channel blockers could be a novel SFTSV drug, but careful examinations and observations of them before their clinical use are required to determine the appropriate dose and timing against SFTS patients to avoid any undesired side effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, reagents, viruses, antibodies, and plasmids.

Vero 76 cells (a simian kidney cell line) obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (JCRB9007) and SW13 cells (a human adrenal gland adenocarcinoma cell line) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The obtainment and maintenance of the Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cell line were described previously (48). An FDA-approved chemical compound library was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (BML-2841J-0100; Farmingdale, NY, USA). Manidipine hydrochloride, cyclosporine, and FK506 were obtained from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN, USA), AdipoGen (San Diego, CA, USA), and Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), respectively. Nifedipine was obtained from Cayman (number 11106). T-705 was provided by Dr. Y. Furuta (Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd., Toyama, Japan). MEYLON (sodium bicarbonate) was purchased from Otsuka Pharmaceutical company (Tokushima, Japan). The SFTSV YG1 strain, which was isolated in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan, was obtained from Dr. K. Maeda (Yamaguchi University) (3), and the virus was propagated using Vero 76 cells. All SFTSV used in this study was prepared as passing them less than five times. The HAZV was a gift from Dr. R. Hewson (Public Health England, UK). The rescue of recombinant LCMV (Armstrong strain) was performed as described previously (24, 49). The VSV Indiana and IAV (H3N2, Aichi) were kind gifts from Dr. H. Kida (Hokkaido University). The JUNV Candid#1 strain was a gift from Dr. J.C. de la Torre (The Scripps Research Institute, USA). Anti-SFTSV N antibodies were either obtained from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID), Japan, or produced by immunizing rabbits with recombinant SFTSV-N (Eurofins Genomics, Tokyo, Japan). To construct pC-YG1-N, the open reading frame (ORF) encoding SFTSV N was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) from SFTSV (YG-1) viral RNA using the primers 5′-AAAAGAGCTCCACCATGTCAGAGTGGTCCAGGATTG-3′ and 5′-GGGTTACAGGTTTCTGTAAGCAGCGG-3′ and inserted into SacI/SmaI site of the pCAGGS plasmid using the Ligation high enzyme (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). To construct pC-YG1-L, the ORF encoding L was amplified by RT-PCR from SFTSV (YG-1) viral RNA using the primers 5′-TCATCGATCCACCATGAACTTGGAAGTGCTTTGTGG-3′ and 5′-GGGTCAACCCCACATAATGGTGCTC-3′ and inserted into SmaI site of the pCAGGS plasmid using the In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (TaKaRa Bio, Ōtsu, Japan). To prepare the plasmid expressing M-segment-based minigenome (pT7-M-hRen), the humanized Renilla luciferase (Rluc) gene was inserted between 5′ and 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of M segment in a negative sense using In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (TaKaRa Bio). The fragment was inserted between T7 promoter and hepatitis delta ribozyme sequences of p3E5EGFP vector (50, 51) In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (TaKaRa Bio). T7-poly was described previously (51). pGL4.54 for the expression of firefly luciferase (Fluc) was purchased from Promega. Ionomycin was purchased from abcam (ab120116). Latrunculin A and cytochalasin D were purchased from Sigma (L5163 and C8273, respectively). Mycalolide B was purchased from Wako (132-12081). To construct pC-HA-actin, the PCR fragment was amplified using 5′-AGATTACGCTGGAGGAGATGATGATATCGC-3′ and 5′-CCTGAGGAGTGAATTCTAGAAGCATTTGCG-3′ with pAcGFP1-actin (Clontech) as a template. This fragment was further elongated to attach HA-tag at the 5′ end with 5′-ATGTATCCATATGACGTTCCAGATTACGCT-3′ and 5′-TTTTGGCAAAGAATTACCATGTATCCATAT-3′ (both forward) and the common reverse primer 5′-CCTGAGGAGTGAATTCTAGAAGCATTTGCG 3′ with GXL polymerase (TaKaRa Bio). Amplified and purified fragments were inserted into pCAGGS plasmid using In-fusion enzyme (TaKaRa Bio). The actin mutant plasmids (Q136L, D10, and D153V) were constructed with combining two overlapping fragments amplified with primer set number 1 (5′-CCACTGGCATCGTGATGGTCTCCGGTGACGGGGTC-3′ and 5′-CCTGAGGAGTGAATTCTAGAAGCATTTGCG-3′) and primer set number 2 (5′-CGCCGCGCTCGTCGTCGTCAACGGCTCCGGCATG-3′ and 5′-GACCCCGTCACCGGAGACCATCACGATGCCAGTGG-3′) from pC-HA-actin using KOD plus enzyme (TOYOBO). These two fragments were combined using KOD plus enzyme and then inserted into pCAGGS plasmid as described above.

Evaluation of the activity of the FDA-approved chemical library against SFTSV replication.

SW13 cells (2.5 × 104) were seeded on a black-walled high-content imaging plate with a 0.2-mm glass bottom (4580; Corning, Corning, NY, USA). On the following day, the cells were infected with SFTSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 90 min, and then the media were replaced with fresh media containing one of the various chemical compounds (20 μg/mL) or DMSO as a control (Fig. 1A). At 48 h p.i., the cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and then incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at RT. FBS (10%) in dilution buffer (3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) was applied to block nonspecific reactivity for more than 1 h at 4°C. Then, a rabbit polyclonal anti-SFTSV N antibody was applied as the primary antibody for 2 h at RT, and then the cells were washed with PBS twice. FITC-anti rabbit IgG antibody (ab6009; abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as the secondary antibody. Pictures of all wells were captured by an LSM780 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), N-positive cells were counted manually in four different fields per experiment, and the mean number of N-positive cells among the DMSO-treated wells was assigned a value of 1. All experiments were performed twice.

SW13 cells (2.5 × 104) were seeded on a 96-well clear plate (167008; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). On the following day, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either chemical compounds or DMSO (Fig. 1A). At 48 h posttreatment, cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and a luminometer (TriStar LB 941; Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). The mean viability of the DMSO-treated control cells was assigned a value of 1. Plates were prepared in duplicate and all experiments were performed twice.

Samples showing a 70% or greater reduction in the number of SFTSV N-positive cells and a 30% or less reduction in cell viability were selected as positive compounds (Table S1).

Evaluation of the chemical compounds’ effects on SFTSV production.

Either SW13 cell (2.5 × 104) or Huh-7 (2 × 104) cells were infected with SFTSV at MOI = 0.1 in a 96-well plate. At 1.5 h p.i., media were replaced with fresh media containing the indicated concentration of compounds. At 24 and/or 48 h p.i., culture media were collected to measure virus titration as described below.

Cell viability assay.

The potential cytotoxicity of manidipine, FK506, or CysA treatments was assessed in SW13 cells using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega). Briefly, 1 × 104 SW13 cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate (167008; Thermo Fisher Scientific). On the following day, the cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the compounds (see Fig. 2B and 9B). At 24 and/or 48 h posttreatment, the CellTiter-Glo reagent was added, and the intensity of the generated luminescence was determined. The cytotoxicity of manidipine, latrunculin A, cytochalasin D, and mycalolide B was assessed in Huh-7 cells (2 × 104 cells) with the same procedure described above (Fig. S2 and S8B).

Measurement of free calcium concentration.

SW13 cells (3 × 104) were seeded on a black-walled high-content imaging plate as described above. The following day, culture media were replaced with DMSO or manidipine-containing (1, 3, 10, or 20 μg/mL) media. At 24 or 48 h posttreatment, Fluo-8 AM (21081; AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was added at a 5-μM final concentration and further incubated for 20 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA. Fluorescence was quantified using an ARVO MX Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter, PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA).

Time-course infection assay.

For SFTSV, 3 × 104 SW13 cells were seeded on a 96-well plate. The culture media of the wells shown in Fig. 4Bb, f, and g were replaced with fresh media containing manidipine (20 μg/mL) and incubated for 2 h (preentry treatment). For the remaining samples, the culture media were replaced with fresh media. All samples were infected with SFTSV at an MOI of 1 for 2 h (1 h at 4°C and then 1 h at 37°C). For wells shown in Fig. 4Bb, c, e, and f, manidipine was included in the virus-containing media (during-entry treatment).After the viral infection step, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO (wells in Fig. 4Ba, e, f, and g) or manidipine (wells in Fig. 4Bb to d) (postentry treatment). After incubation for 16 h, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with an anti-SFTSV N antibody as described above. Pictures were captured using a BZ-X700 microscope. To examine the release of viral particles, the cells were infected with either virus at an MOI of 0.1 or 1 for 2 h. The culture media were then replaced with fresh media, and the cells were incubated for a further 16 h. Afterward, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine. Samples of the culture media were collected every 2 h for up to 24 h p.i. Viral titers were measured and normalized by deducting the corresponding titer from that at time point 0 (18 h p.i.).

Effects of chemical compounds against NSVs.

SW13 cells (3 × 104 cells) were seeded on a 96-well plate. On the following day, the cells were infected with VSV, HAZV, LCMV, or JUNV (Candid#1 strain) at MOI = 0.1 (Fig. 6). After incubating the cells for 1.5 h to allow viral absorption, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing the indicated compounds or DMSO as a control. At the indicated times after infection, the culture supernatants were used for viral titration as described below. MDCK cells (2 × 104 cells) were seeded on a 96-well plate. On the following day, the cells were infected with IAV at an MOI of 0.1. At 1.5 h p.i., and the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine. At 24 h p.i., the culture media were collected to analyze using plaque assay. For LCMV and VSV (Fig. 7), 3 × 104 SW13 cells were seeded on a 96-well plate. On the following day, the cells were infected with LCMV (MOI = 1 or 5) or VSV (MOI = 1) for 2 h, and then the media were replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL). For LCMV, the cells were incubated for a further 16 h and then fixed with 4% PFA. The fixed cells were stained with an anti-LCMV NP antibody and DAPI. For VSV, the cells were incubated for 7 h after a 1-h infection and then were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with DAPI. Pictures were captured using a BZ-X700 microscope.

Viral titration.

The titers of SFTSV and LCMV were determined by an immunofocus assay. Vero 76 cells (3 × 104 cells) were seeded on a 96-well plate 1 day before infection. The cells were infected with 1:10 serial dilutions of the viruses, and incubation was continued for 16 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cells were then fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min at RT and incubated with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at RT. Blocking with 10% FBS in dilution buffer was performed at 4°C overnight. For SFTSV titration, the SFTSV-N protein was detected using an anti-SFTSV-N antibody, followed by an anti-rabbit IgG-FITC antibody (Abcam). For LCMV titration, anti-LCMV NP rat-IgG antibody (VL-4; BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) and Alexa Fluor 488-anti rat IgG antibody (ab150157; Abcam) were used. Samples were observed using an AxioVert.A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss). The numbers of SFTSV N- or LCMV NP-positive cells were determined and normalized as FFU per mL. The titers of VSV and JUNV (Candid#1 strain) were determined by a plaque assay using Vero 76 cells and described as PFU per mL. The titers of HAZV were determined by the plaque assay using SW13 cells and described as PFU per mL. The titer of IAV was determined by a plaque assay described previously (48).

Quantification of SFTSV viral RNA by qPCR upon manidipine treatment.

SW13 cells (1 × 105 cells) were infected with SFTSV at MOI = 1, and at 1.5 h postinfection, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing DMSO or manidipine (20 μg/mL). At 1.5 and 17.5 h p.i., RNA was collected using TRIzol LS reagent (Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of RNA were used for reverse transcription (cloned AMV reverse transcriptase, 12328-019; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using a 5′-biotinylated primer (5′-AGGAAAGACGCAAAGGAGTG-3′) that targets viral RNA (vRNA). After the synthesis of cDNA from the isolated vRNA, the biotinylated cDNA products were purified using Dynabeads M-280 streptavidin (11205D; Invitrogen). The purified cDNA was then used as a template for qPCR using the primers 5′-GCTGAAGGAGACAGGTGGAG-3′ and 5′-GCAACCCTCACAGGAGTGAT-3′ with SYBR Premix Ex Taq, Tli RNase H plus (RR420A; TaKaRa Bio, Ōtsu, Japan) and a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A plasmid containing the whole SFTSV S segment was diluted and used to obtain a standard curve.

Western blot analysis.

SFTSV-infected SW13 cells were treated with DMSO or L-type calcium channel blockers with the indicated concentration. To detect and analyze the expression of SFTSV N in the infected cells, cell lysate was prepared with lysis A buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 62.5 mM EDTA, and 0.4% sodium deoxycholate). WES (ProteinSimple, Tokyo, Japan) was used to detect SFTSV N with Ez Standard Pack 1 (PS-ST01EZ-8; ProteinSimple), anti-rabbit chemiluminescence detection module (DM-001l ProteinSimple), together with anti-SFTSV N antibody, which was described above.

SFTSV minigenome assay.

Huh-7 cells (1 × 105) were transfected with pC-YG-1 N (125 ng), pC-YG-1 L (125 ng), pT7-M-hRen (125 ng), pGL4.54 (50 ng), and T7-poly (250 ng) using LT1 (Mirus) according to the instructions. At 6 h posttransfection, culture media were replaced with fresh media containing DMSO or other actin-related reagents. One day posttransfection, both Fluc and hRen were detected using Dual-Glo Luciferase assay system (Promega).

Animals.

IFNAR−/− mice were produced by mating DNase II/IFN-I receptor double knockout mice (strain B6.129-Dnase2a<tm10sa>Ifnar1<tm1Agt>) (52, 53) and C57BL/6 mice as described previously (30). DNase II/IFN-IR double-knockout mice, deposited by Shigekazu Nagata (Biochemistry and Immunology, Immunology Frontier Research Center, Osaka University) and Michel Aguent (ISREC-School of Life Sciences, EPFL), were provided by the RIKEN BioResource Center, Japan, through the National Bio-Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan.

Animal experiments.

IFNAR−/− mice were bred and maintained in an environmentally controlled specific pathogen-free animal facility of Nagasaki University. Six- to 8-week-old male or female mice were used. In infection experiments, each mouse was infected with SFTSV by subcutaneous injection (200 μL of virus solution for 10 FFU). Each group of mice were administered PBS-T (PBS with 2% Tween 20, control) or 10 mg/kg of manidipine twice a day at day 4 and day 5 p.i. by i.p. injection (100 μL). Manidipine was resolved by PBS-T before each injection. The same procedure was used for T-705 injection but T-705 was resolved by MEYLON. One set of groups was monitored for the survival rate. Mice from another set of groups were euthanized at day 7 p.i. to collect spleen, kidney, liver, and serum to measure the virus titer.

Ethics statement.

All experiments associated with animals were performed in animal biological safety level 3 (BSL-3) containment laboratories at Nagasaki University under strict regulations of the animal experimentation guidelines of the Nagasaki University (approval no.1310151247 for working with recombinant DNA including work with knockout mice). All experimental procedures were reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nagasaki University and finally approved by the president (no. 1511301262).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Maeda (Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi, Japan) for providing the SFTSV YG1 strain. We also thank S. Morikawa and S. Fukushi (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) for providing the anti-SFTSV N antibody. In addition, we thank J. C. de la Torre (The Scripps Research Institute), H. Kida (Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan), and R. Hewson (Public Health England, UK) for providing the JUNV Candid#1 strain (J.C.T.), the VSV Indiana (H.K.), HAZV (R.H.), and SW13 cells (R.H.). We gratefully acknowledge Y. Furuta (Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd., Toyama, Japan) for providing agents. We are grateful to all the members of the Department of Emerging Infectious Diseases, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University. We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

This research was supported by a grant from the Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from Japan Agency for Medical Research and development (AMED) under grant number 17fk0108202h0805 and a Grant-in-Aid from the Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation and Kato Memorial Bioscience Foundation.

We declare that there are no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Shuzo Urata, Email: shuzourata@nagasaki-u.ac.jp.

Jiro Yasuda, Email: j-yasuda@nagasaki-u.ac.jp.

Rebecca Ellis Dutch, University of Kentucky College of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, Liu Y, Li JD, Sun YL, Zhang L, Zhang QF, Popov VL, Li C, Qu J, Li Q, Zhang YP, Hai R, Wu W, Wang Q, Zhan FX, Wang XJ, Kan B, Wang SW, Wan KL, Jing HQ, Lu JX, Yin WW, Zhou H, Guan XH, Liu JF, Bi ZQ, Liu GH, Ren J, Wang H, Zhao Z, Song JD, He JR, Wan T, Zhang JS, Fu XP, Sun LN, Dong XP, Feng ZJ, Yang WZ, Hong T, Zhang Y, Walker DH, Wang Y, Li DX. 2011. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med 364:1523–1532. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu B, Liu L, Huang X, Ma H, Zhang Y, Du Y, Wang P, Tang X, Wang H, Kang K, Zhang S, Zhao G, Wu W, Yang Y, Chen H, Mu F, Chen W. 2011. Metagenomic analysis of fever, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia syndrome (FTLS) in Henan Province, China: discovery of a new bunyavirus. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002369. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi T, Maeda K, Suzuki T, Ishido A, Shigeoka T, Tominaga T, Kamei T, Honda M, Ninomiya D, Sakai T, Senba T, Kaneyuki S, Sakaguchi S, Satoh A, Hosokawa T, Kawabe Y, Kurihara S, Izumikawa K, Kohno S, Azuma T, Suemori K, Yasukawa M, Mizutani T, Omatsu T, Katayama Y, Miyahara M, Ijuin M, Doi K, Okuda M, Umeki K, Saito T, Fukushima K, Nakajima K, Yoshikawa T, Tani H, Fukushi S, Fukuma A, Ogata M, Shimojima M, Nakajima N, Nagata N, Katano H, Fukumoto H, Sato Y, Hasegawa H, Yamagishi T, Oishi K, Kurane I, Morikawa S, Saijo M. 2014. The first identification and retrospective study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan. J Infect Dis 209:816–827. 10.1093/infdis/jit603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KH, Yi J, Kim G, Choi SJ, Jun KI, Kim NH, Choe PG, Kim NJ, Lee JK, Oh MD. 2013. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1892–1894. 10.3201/eid1911.130792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran XC, Yun Y, Van An L, Kim SH, Thao NTP, Man PKC, Yoo JR, Heo ST, Cho NH, Lee KH. 2019. Endemic severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis 25:1029–1031. 10.3201/eid2505.181463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin TL, Ou SC, Maeda K, Shimoda H, Chan JP, Tu WC, Hsu WL, Chou CC. 2020. The first discovery of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Taiwan. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:148–151. 10.1080/22221751.2019.1710436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, MacNeil A, Goldsmith CS, Metcalfe MG, Batten BC, Albarino CG, Zaki SR, Rollin PE, Nicholson WL, Nichol ST. 2012. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med 367:834–841. 10.1056/NEJMoa1203378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Basu A, Shete A, Patil DY, Zawar D, Majumdar TD, Kokate P, Sarkale P, Raut CG, Jadhav SM. 2014. Malsoor virus, a novel bat phlebovirus, is closely related to severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and heartland virus. J Virol 88:3605–3609. 10.1128/JVI.02617-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimojima M, Fukushi S, Tani H, Taniguchi S, Fukuma A, Saijo M. 2015. Combination effects of ribavirin and interferons on severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection. Virol J 12:181. 10.1186/s12985-015-0412-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimojima M, Fukushi S, Tani H, Yoshikawa T, Fukuma A, Taniguchi S, Suda Y, Maeda K, Takahashi T, Morikawa S, Saijo M. 2014. Effects of ribavirin on severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in vitro. Jpn J Infect Dis 67:423–427. 10.7883/yoken.67.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tani H, Fukuma A, Fukushi S, Taniguchi S, Yoshikawa T, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Sato Y, Suzuki T, Nagata N, Hasegawa H, Kawai Y, Uda A, Morikawa S, Shimojima M, Watanabe H, Saijo M. 2016. Efficacy of T-705 (Favipiravir) in the treatment of infections with lethal severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. mSphere 1:e00061-15. 10.1128/mSphere.00061-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kouznetsova J, Sun W, Martinez-Romero C, Tawa G, Shinn P, Chen CZ, Schimmer A, Sanderson P, McKew JC, Zheng W, Garcia-Sastre A. 2014. Identification of 53 compounds that block Ebola virus-like particle entry via a repurposing screen of approved drugs. Emerg Microbes Infect 3:e84. 10.1038/emi.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen LM, DeWald LE, Shoemaker CJ, Hoffstrom BG, Lear-Rooney CM, Stossel A, Nelson E, Delos SE, Simmons JA, Grenier JM, Pierce LT, Pajouhesh H, Lehar J, Hensley LE, Glass PJ, White JM, Olinger GG. 2015. A screen of approved drugs and molecular probes identifies therapeutics with anti-Ebola virus activity. Sci Transl Med 7:290ra89. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He S, Lin B, Chu V, Hu Z, Hu X, Xiao J, Wang AQ, Schweitzer CJ, Li Q, Imamura M, Hiraga N, Southall N, Ferrer M, Zheng W, Chayama K, Marugan JJ, Liang TJ. 2015. Repurposing of the antihistamine chlorcyclizine and related compounds for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Sci Transl Med 7:282ra49. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrows NJ, Campos RK, Powell ST, Prasanth KR, Schott-Lerner G, Soto-Acosta R, Galarza-Munoz G, McGrath EL, Urrabaz-Garza R, Gao J, Wu P, Menon R, Saade G, Fernandez-Salas I, Rossi SL, Vasilakis N, Routh A, Bradrick SS, Garcia-Blanco MA. 2016. A screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 20:259–270. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Liu Y, Guo J, Wang P, Zhang L, Xiao G, Wang W. 2017. Screening of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J Virol 91:e01055-17. 10.1128/JVI.01055-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P, Liu Y, Zhang G, Wang S, Guo J, Cao J, Jia X, Zhang L, Xiao G, Wang W. 2018. Screening and identification of Lassa virus entry inhibitors from an FDA-approved drugs library. J Virol 92:e00954-18. 10.1128/JVI.00954-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janmey PA. 1994. Phosphoinositides and calcium as regulators of cellular actin assembly and disassembly. Annu Rev Physiol 56:169–191. 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh TP, Weber A, Davis K, Bonder E, Mooseker M. 1984. Calcium dependence of villin-induced actin depolymerization. Biochemistry 23:6099–6102. 10.1021/bi00320a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalghi MG, Ferreira-Gomes M, Rossi JP. 2018. Regulation of the plasma membrane calcium ATPases by the actin cytoskeleton. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 506:347–354. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Xu M, Tang B, Hu L, Deng F, Wang H, Pang DW, Hu Z, Wang M, Zhou Y. 2019. Single-particle tracking reveals the sequential entry process of the bunyavirus severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Small 15:e1803788. 10.1002/smll.201803788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urata S, Ngo N, de la Torre JC. 2012. The PI3K/Akt pathway contributes to arenavirus budding. J Virol 86:4578–4585. 10.1128/JVI.06604-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urata S, Kenyon E, Nayak D, Cubitt B, Kurosaki Y, Yasuda J, de la Torre JC, McGavern DB. 2018. BST-2 controls T cell proliferation and exhaustion by shaping the early distribution of a persistent viral infection. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007172. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urata S, Yun N, Pasquato A, Paessler S, Kunz S, de la Torre JC. 2011. Antiviral activity of a small-molecule inhibitor of arenavirus glycoprotein processing by the cellular site 1 protease. J Virol 85:795–803. 10.1128/JVI.02019-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lokupathirage SMW, Tsuda Y, Ikegame K, Noda K, Muthusinghe DS, Kozawa F, Manzoor R, Shimizu K, Yoshimatsu K. 2021. Subcellular localization of nucleocapsid protein of SFTSV and its assembly into the ribonucleoprotein complex with L protein and viral RNA. Sci Rep 11:22977. 10.1038/s41598-021-01985-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchholz M, Ellenrieder V. 2007. An emerging role for Ca2+/calcineurin/NFAT signaling in cancerogenesis. Cell Cycle 6:16–19. 10.4161/cc.6.1.3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenmund C, Westbrook GL. 1993. Calcium-induced actin depolymerization reduces NMDA channel activity. Neuron 10:805–814. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90197-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anonymous . 1986. Arenaviruses. Fourth International Symposium of the Heinrich-Pette-Institut fur Experimentelle Virologie und Immunologie an der Universitat Hamburg. Hamburg, 23–26 September 1985. Med Microbiol Immunol 175:61–220. 10.1007/BF02122415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Wu B, Paessler S, Walker DH, Tesh RB, Yu XJ. 2014. The pathogenesis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection in alpha/beta interferon knockout mice: insights into the pathologic mechanisms of a new viral hemorrhagic fever. J Virol 88:1781–1786. 10.1128/JVI.02277-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshikawa R, Sakabe S, Urata S, Yasuda J. 2019. Species-specific pathogenicity of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus is determined by anti-STAT2 activity of NSs. J Virol 93:e02226-18. 10.1128/JVI.02226-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan S, Chan JF, Ye ZW, Wen L, Tsang TG, Cao J, Huang J, Chan CC, Chik KK, Choi GK, Cai JP, Yin F, Chu H, Liang M, Jin DY, Yuen KY. 2019. Screening of an FDA-approved drug library with a two-tier system identifies an entry inhibitor of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Viruses 11:385. 10.3390/v11040385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Zhang LK, Li SF, Zhang SF, Wan WW, Zhang YL, Xin QL, Dai K, Hu YY, Wang ZB, Zhu XT, Fang YJ, Cui N, Zhang PH, Yuan C, Lu QB, Bai JY, Deng F, Xiao GF, Liu W, Peng K. 2019. Calcium channel blockers reduce severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) related fatality. Cell Res 29:739–753. 10.1038/s41422-019-0214-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen S, Zhang Y, Yin Z, Zhu Q, Zhang J, Wang T, Fang Y, Wu X, Bai Y, Dai S, Liu X, Jin J, Tang S, Liu J, Wang M, Guo Y, Deng F. 2022. Antiviral activity and mechanism of the antifungal drug, anidulafungin, suggesting its potential to promote treatment of viral diseases. BMC Med 20:359. 10.1186/s12916-022-02558-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bang MS, Kim CM, Kim DM, Yun NR. 2022. Effective Drugs Against Severe Fever With Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus in an in vitro Model. Front Med 9:839215. 10.3389/fmed.2022.839215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Yan Y, Dai Q, Yin J, Zhao L, Li Y, Li W, Zhong W, Cao R, Li S. 2022. Tilorone confers robust in vitro and in vivo antiviral effects against severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Virol Sin 37:145–148. 10.1016/j.virs.2022.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clapham DE. 2007. Calcium signaling. Cell 131:1047–1058. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Im SH, Rao A. 2004. Activation and deactivation of gene expression by Ca2+/calcineurin-NFAT-mediated signaling. Mol Cells 18:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crabtree GR, Schreiber SL. 2009. SnapShot: Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Cell 138:210–210.e1. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han Z, Madara JJ, Herbert A, Prugar LI, Ruthel G, Lu J, Liu Y, Liu W, Liu X, Wrobel JE, Reitz AB, Dye JM, Harty RN, Freedman BD. 2015. Calcium regulation of hemorrhagic fever virus budding: mechanistic implications for host-oriented therapeutic intervention. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005220. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakurai Y, Kolokoltsov AA, Chen CC, Tidwell MW, Bauta WE, Klugbauer N, Grimm C, Wahl-Schott C, Biel M, Davey RA. 2015. Ebola virus. Two-pore channels control Ebola virus host cell entry and are drug targets for disease treatment. Science 347:995–998. 10.1126/science.1258758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ehrlich LS, Medina GN, Photiadis S, Whittredge PB, Watanabe S, Taraska JW, Carter CA. 2014. Tsg101 regulates PI(4,5)P2/Ca(2+) signaling for HIV-1 Gag assembly. Front Microbiol 5:234. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendoza CA, Yamaoka S, Tsuda Y, Matsuno K, Weisend CM, Ebihara H. 2021. The NF-kappaB inhibitor, SC75741, is a novel antiviral against emerging tick-borne bandaviruses. Antiviral Res 185:104993. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otterbein LR, Graceffa P, Dominguez R. 2001. The crystal structure of uncomplexed actin in the ADP state. Science 293:708–711. 10.1126/science.1059700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harpen M, Barik T, Musiyenko A, Barik S. 2009. Mutational analysis reveals a noncontractile but interactive role of actin and profilin in viral RNA-dependent RNA synthesis. J Virol 83:10869–10876. 10.1128/JVI.01271-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delang L, Segura Guerrero N, Tas A, Querat G, Pastorino B, Froeyen M, Dallmeier K, Jochmans D, Herdewijn P, Bello F, Snijder EJ, de Lamballerie X, Martina B, Neyts J, van Hemert MJ, Leyssen P. 2014. Mutations in the chikungunya virus non-structural proteins cause resistance to favipiravir (T-705), a broad-spectrum antiviral. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:2770–2784. 10.1093/jac/dku209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]