Abstract

A tritiated derivative of the sponge-derived natural product spongistatin 1 was prepared, and its interactions with tubulin were examined. [3H]Spongistatin 1 was found to bind rapidly to tubulin at a single site (the low specific activity of the [3H]spongistatin 1, 0.75 Ci/mmol, prevented our defining an association rate), and the inability of spongistatin 1 to cause an aberrant assembly reaction was confirmed. Spongistatin 1 bound to tubulin very tightly, and we could detect no significant dissociation reaction from tubulin. The tubulin-[3H] spongistatin 1 complex did dissociate in 8 M urea, so there was no evidence for covalent bond formation. Apparent KD values were obtained by Scatchard analysis of binding data and by Hummel-Dreyer chromatography (3.5 and 1.1 μM, respectively). The effects of a large cohort of vinca domain drugs on the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin were evaluated. Compounds that did not cause aberrant assembly reactions (halichondrin B, eribulin, maytansine, and rhizoxin) caused little inhibition of [3H]spongistatin 1 binding. Little inhibition also occurred with the peptides dolastatin 15, its active pentapeptide derivative, vitilevuamide, or diazonamide A, nor with the vinca alkaloid vinblastine. Strong inhibition was observed with dolastatin 10, hemiasterlin, and cryptophycin 1, all of which cause aberrant assembly reactions that might actually mask the spongistatin 1 binding site. Spongistatin 5 was found to be a competitive inhibitor of [3H] spongistatin 1 binding, with an apparent Ki of 2.2 μM. We propose that the strong picomolar cytotoxicity of spongistatin 1 probably derives from its extremely tight binding to tubulin.

Keywords: Spongistatin 1, Halichondrin B, Vinca domain, Inhibitors of microtubule assembly, Spongistatin 5, HPLC Hummel-Dreyer analysis

1. Introduction

Inhibitors of microtubule assembly typically inhibit the binding of radiolabeled colchicine or vinblastine to tubulin. Inhibitors of vinblastine binding comprise a large number of natural products, most of which are highly cytotoxic. Most of these compounds show noncompetitive patterns of inhibition of vinblastine binding, implying distinct binding sites on tubulin. Among the noncompetitive inhibitors of vinblastine binding are the peptides and depsipeptides dolastatin 10 [1], hemiasterlin [2], cryptophycin 1 [3], vitilevuamide [4], and tubulysin A [5] and the complex macrocyclic compounds halichondrin B (NSC 609395) [6] and spongistatin 1 (NSC 650378) [7]. Structures of the latter two compounds are shown in Fig. 1, along with that of spongistatin 5 (NSC 661119), a congener of spongistatin 1, used in experiments described here. The structures of spongistatins 1 and 5 shown in Fig. 1 are based on details worked out in chemical syntheses summarized by Crimmins et al. [8]. Antimitotic peptides can act as competitive inhibitors of the binding of radiolabeled dolastatin 10 [2,3] to tubulin, while the halichondrin B analogue eribulin (NSC 707389) and spongistatin 1 yielded noncompetitive patterns of inhibition of dolastatin 10 binding [9,10]. Finally, the binding of [3H]halichondrin B was inhibited competitively by eribulin and noncompetitively by dolastatin 10 and vincristine [11].

Fig. 1.

Structures of spongistatins 1 and 5 and of halichondrin B.

While a pattern of noncompetitive inhibition implies allosteric effects causing reduced ligand binding, all inhibitors of vinblastine binding also inhibit, with varying potency, GDP/GTP entry into or exit from the exchangeable nucleotide site. This led us to postulate that there is a region on tubulin that should be designated the "vinca domain" and that many of the drug inhibition effects were caused by steric factors preventing access of guanine nucleotides, vinca alkaloids, peptide antimitotics, and halichondrin B to their respective binding sites. Available crystallographic evidence is consistent with this model [12-19].

Spongistatin 1, although a strong inhibitor of vinblastine and dolastatin 10 binding, only weakly inhibits halichondrin B binding [11]. In addition, spongistatin 1 is an unusually cytotoxic compound, inhibiting the growth of cell lines with picomolar and subpicomolar IC50 values [7]. To gain greater understanding of the mechanisms involved in the interactions of spongistatin 1 with tubulin and to help clarify the interrelationships among drug binding sites on tubulin, we undertook the preparation of [3H]spongistatin 1. In this paper, we describe how we used [3H]spongistatin 1 to explore the mode of binding of the compound to tubulin and to examine effects of other vinca domain drugs on this binding interaction.

Most of the compounds described above were evaluated by us for effects on the binding of [3H]halichondrin B to tubulin [11] and were evaluated in this study for effects on the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin. These compounds are generally strong inhibitors of vinblastine binding to tubulin. In addition, we have evaluated effects of other strong inhibitors of vinblastine binding (maytansine, rhizoxin) and of three compounds that have little effect on vinblastine or GTP binding but do inhibit GTP hydrolysis [diazonamide A, dolastatin 15, and the latter’s intracellular degradation product, the pentapeptide N,N-dimethylvalylvalyl-N-methylvalylprolylproline (P52)] [20,21].

Spongistatin 1, because of its potent cytotoxicity [7], might have a role to play in the treatment of human cancer patients. Unfortunately, the scarcity of the compound has resulted in only two published anticancer studies in animals. The first published study by Rothmeir et al. [22] was with a human pancreatic cancer model in nude mice. L3.6 pl cells were injected into the pancreatic capsule, and six days later the mice were treated with 10 μg/kg of spongistatin 1 injected daily intraperitoneally until day 27. There was about an 85% reduction in tumor volume and a 50% reduction in tumor weight. In addition, there was about a 70% reduction in lymph node and liver metastases and a 50% reduction in peritoneal carcinosis. The second study by Xu et al. [23] evaluated the effect of a higher dose of spongistatin 1 in human LOX-IMVI melanoma cell tumors in nude mice. The cells were injected subcutaneously, and seven days later treatment began with varying doses of spongistatin 1 injected into the tail veins of the mice every 4 days. The only dose that was effective therapeutically was 0.24 mg/kg, which led to a 75% reduction in tumor volume.

As far as we know, there have been no efforts to include spongistatin 1 in a drug-antibody conjugate. The high cytotoxicity of the compound would seem to make it an ideal candidate for such a therapeutic modality [24].

One of our principal goals in this study was to gain some insight into how the binding site for spongistatin 1 related to those of other vinca domain agents. These compounds may be divided into two categories, those that cause aberrant assembly reactions and those that do not. (An aberrant assembly reaction is defined here as formation of tubulin polymers with nonmicrotubule, but structurally discrete, morphologies.) The former includes the vinca alkaloids and all the peptidic antimitotic agents that have been evaluated for this phenomenon (dolastatin 10 and congeners, cryptophycin 1 and congeners, hemiasterlin and congeners, diazonamide A). The latter includes spongistatin 1, halichondrin B, maytansine, and rhizoxin. The former group seems to require two αβ-tubulin heterodimers to form their binding site, akin to the site being between two heterodimers in a protofilament, with the agents binding between the α-tubulin of one heterodimer and the β-tubulin of the adjacent heterodimer (cf. ref. 12, for vinblastine binding). In contrast, the binding site(s) for the latter group are probably on β-tubulin alone. See ref. 14 for the maytansine binding site, where not only maytansine binds, but also rhizoxin and a peptidic antimitotic agent PM060184, and ref. 16 for the eribulin binding site, which presumably accommodates the macrocycle of halichondrin B, while the spongistatin 1 site remains to be elucidated crystallographically.

The chemical structures of spongistatin 1 and halichondrin B have similarities, both compounds being macrocyclic polyether lactones, and we had originally anticipated that they would share a binding site on tubulin. The comparative studies and binding studies presented here did not confirm this hypothesis.

Finally, with the [3H]spongistatin 1, we hoped to gain insight into the binding mechanism of spongistatin 1 to tubulin. The specific activity of our [3H]spongistatin 1 was too low to evaluate the association rate (the compound seemed to bind instantly to tubulin), but we did learn that, once bound, the spongistatin 1 did not dissociate from tubulin, remaining bound despite extensive gel filtration chromatography. We were able to determine μM apparent KD values by Scatchard and Hummel-Dreyer analyses. These biochemical properties may help explain the high cytotoxicity of spongistatin 1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Electrophoretically homogeneous bovine brain tubulin was prepared as described previously [25], including removal of unbound nucleotide by gel filtration chromatography on Sephadex G-50 (superfine) [26]. The apparent purity of tubulin prepared by this method has been documented by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (no contaminating protein bands observed) and extensive biochemical characterization [25,26]. Spongistatin 1 was synthesized as described before [27] and was tritiated at AmBios Labs (0.75 Ci/mmol). Maytansine, rhizoxin, vinblastine, dolastatin 15, halichondrin B, and eribulin were provided by the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch and the Natural Products Branch, National Cancer Institute. The preparation of [3H]halichondrin B (0.9 Ci/mmol), also at Ambios Labs, was described previously [11]. Cryptophycin 1, vitilevuamide, and P5 were generous gifts, respectively, from Merck Research Laboratories, Dr. Chris M. Ireland (University of Utah), and the Genzyme Corporation. Dolastatin 10 [28], hemiasterlin [29], and diazonamide A [30] were prepared or isolated as described previously.

2.2. Biochemical methods

Binding studies, except as indicated, were performed by centrifugal gel filtration on microcolumns of Sephadex G-50 (superfine) in tuberculin syringe barrels [31]. The Sephadex was swollen in a solution containing 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 M 4-morpholineethanesulfonate (Mes) (1 M stock solution adjusted to pH 6.9 with NaOH). Unless indicated otherwise, all reaction mixtures also contained 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9, as above), as well as 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (the solvent for all drugs). The hydrated bed volume for the microcolumns was 1.0 mL, and, prior to sample application, an initial 4 min centrifugation at 2000 rpm in a Beckman Allegra 6 KR centrifuge with a GH-3.8A horizontal rotor was performed to remove excess buffer from the columns. Reaction mixture volume was generally 0.3 mL, and duplicate 0.145 mL aliquots were applied to two pre-centrifuged microcolumns following incubations as indicated. The microcolumns were again centrifuged for 4 min at 2000 rpm. If reaction mixtures were incubated on ice, centrifugation was at 4 °C. If reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature or 37 °C, centrifugation was at room temperature. Aliquots of the filtrates were analyzed for protein content by the Lowry method and for radiolabel by liquid scintillation counting, and these data were used to determine stoichiometry of binding.

Analysis by size exclusion high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was with an Agilent Technologies system. Either one, two, or three Shodex protein KW-803 columns (8 × 300 mm), together with a Shodex KWG guard column (6 × 50 mm), were used. Column outflow was analyzed in sequence by an Agilent UV monitor at 280 nm and, if appropriate, an IN/US β RAM model 4 flow detector. For Hummel-Dreyer analyses, the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, and 1.0 mL fractions were collected for determination of protein and radiolabel for determination of apparent KD values.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary characterization of the interaction of [3H]spongistatin 1 with tubulin

Initially, we examined the rate of binding of spongistatin 1 to tubulin and the effects of temperature on the reaction. As summarized in Table 1, we observed rapid binding of the ligand to tubulin, and the effects of temperature in the range of 0–37 °C were minimal.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 1 to tubulin.

| I: Rapid binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulina | |

|---|---|

| Incubation time | Stoichiometry of bindingb |

| As fast as possible (estimate: 20 s) | 0.20 |

| 30 s | 0.18 |

| 1 min | 0.18 |

| 2 min | 0.18 |

| 10 min |

0.22 |

| II: Reaction temperature has little effect on [3H]spongistatin 1 bindingc | |

| Temperature |

Stoichiometry of bindingb ± S.D. |

| 0 °C | 0.075 ± 0.008 |

| 22 °C (room temperature) | 0.088 ± 0.005 |

| 37 °C | 0.076 ± 0.003 |

Each sample contained 0.5 mg/mL (5.0 μM) tubulin, 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9), 0.5 mM MgCl2, 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide, and 5.0 μM [3H]spongistatin 1 in a 0.3 mL volume. Incubation was for the indicated times at 22 °C.

Stoichiometry of binding is expressed as mol [3H]spongistatin 1 bound per mol tubulin.

Reaction mixtures were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 15 min and applied to microcolumns at the same temperature. Centrifugation was at 0 °C for the 0 °C experiment, or at 22 °C for the 22 and 37 °C experiments.

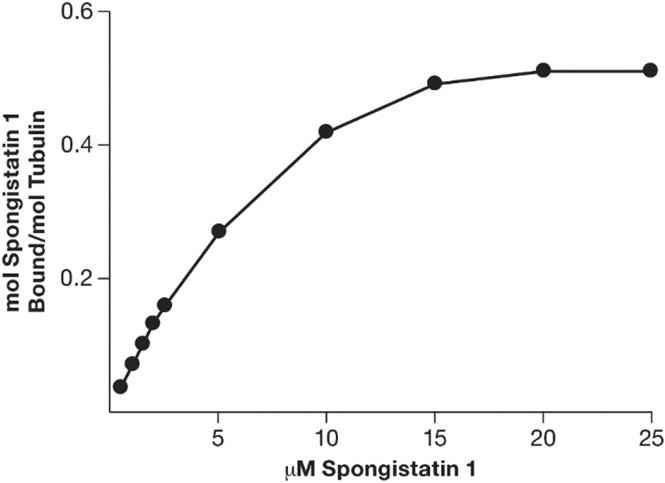

Finally, we found that increasing amounts of [3H]spongistatin 1 in the reaction mixture resulted in increasing amounts of bound compound, with saturation occurring at about half stoichiometry with 15–20 μM spongistatin 1 when the tubulin concentration was 5 μM (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of spongistatin 1 concentration on the stoichiometry of binding to 5.0 μM tubulin. Reaction mixtures contained the indicated concentrations of [3H]spongistatin 1, 5.0 μM (0.5 mg/mL) tubulin, 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9), 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at room temperature before two aliquots of each reaction mixture were applied to microcolumns.

3.2. Inhibitory effects of vinca domain compounds on the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin, with a comparison to [3H]halichondrin B

To gain some insight into the nature of the binding site for spongistatin 1, we examined the effects of a large series of vinca domain compounds on the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 and of [3H]halichondrin B (Table 2). We had initially assumed that their polyether structural similarity (see Fig. 1) would lead to similar patterns of inhibition by other vinca domain drugs, but this was not what was observed.

Table 2.

Effects of vinca domain agents on the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 and [3H]halichondrin B to tubulina.

| Inhibitor | [3H]Spongistatin 1 |

[3H]Halichondrin B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor:Ligand | ||||

| 0.5:1b | 20:1c | 0.5:1b | 20:1c | |

| % Inhibition ± S.D. | ||||

| Spongistatin 1 | 19 ± 8 | 30 ± 10 | ||

| Spongistatin 5 | 0 | 82 ± 2 | 0 | 39 ± 9 |

| Halichondrin B | 0.5 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.7 | ||

| Eribulin | 0 | 0 | 36 ± 2 | 89 ± 0.7 |

| Vinblastine | 17 ± 5 | 13 ± 2 | 4 ± 4 | 62 ± 4 |

| Maytansine | 3 ± 0.9 | 13 ± 0.9 | 3 ± 4 | 11 ± 7 |

| Rhizoxin | 4 ± 0.9 | 14 ± 2 | 6 ± 7 | 9 ± 1 |

| Dolastatin 10 | 57 ± 5 | 86 ± 4 | 50 ± 1 | 85 ± 5 |

| Hemiasterlin | 40 ± 4 | 89 ± 5 | 23 ± 5 | 94 ± 2 |

| Cryptophycin 1 | 27 ± 3 | 70 ± 2 | 4 ± 3 | 4 ± 0.7 |

| Dolastatin 15 | 0 | 10 ± 7 | 0 | 0 |

| P5 | 4 ± 3 | 15 ± 10 | 2d | 16d |

| Vitilevuamide | 2 ± 1 | 9 ± 6 | 0 | 5 ± 7 |

| Diazonamide A | 2 ± 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Reaction mixtures (300 μL) contained 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9), 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide. All experiments were performed twice, except as indicated. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at room temperature before two aliquots of each reaction mixture were applied to microcolumns.

Reaction mixtures contained 1.0 mg/mL (10 μM) tubulin, 10 μM ligand (either [3H]spongistatin 1 or [3H]halichondrin B), and the indicated inhibitors at 5 μM.

Reaction mixtures contained 2.5 μM tubulin, 2.5 μM ligand (either [3H]spongistatin 1 or [3H]halichondrin B), and the indicated inhibitors at 50 μM.

The experiment was performed once.

Most strikingly, and contrary to our assumptions, halichondrin B and its congener eribulin had no ability to inhibit [3H]spongistatin 1 binding to tubulin, and spongistatin 1 and its congener spongistatin 5 had only modest ability to inhibit [3H]halichondrin B binding. The validity of these unexpected results was confirmed with control experiments: spongistatin 5, as well as other spongistatin analogues [9] (data not presented), inhibited [3H]spongistatin 1 binding, and eribulin inhibited [3H]halichondrin B binding.

Maytansine and rhizoxin, which bind at a distinct site on β-tubulin [14], inhibited neither spongistatin 1 nor halichondrin B binding. Similar negative results were obtained with dolastatin 15 and its more potent intracellular degradation product P5 and with the peptidic compounds vitilevuamide and diazonamide A.

Most compounds that cause extensive aberrant assembly reactions, on the other hand, did have inhibitory effects. The vinca alkaloid vinblastine displayed minimal inhibition of [3H]spongistatin 1 binding, but, at the higher concentration examined, it strongly inhibited [3H]halichondrin B binding. The potent antimitotic peptides dolastatin 10 and hemiasterlin strongly inhibited the binding of both [3H]spongistatin 1 and [3H]halichondrin B. The antimitotic depsipeptide cryptophycin 1, however, inhibited only [3H]spongistatin 1 binding, and it was non-inhibitory with [3H]halichondrin B. It should be pointed out that the apparent inhibitory effects of compounds that cause aberrant tubulin assembly reactions might not represent true inhibition but simply masking of the binding sites in the polymers induced by some or all of these compounds.

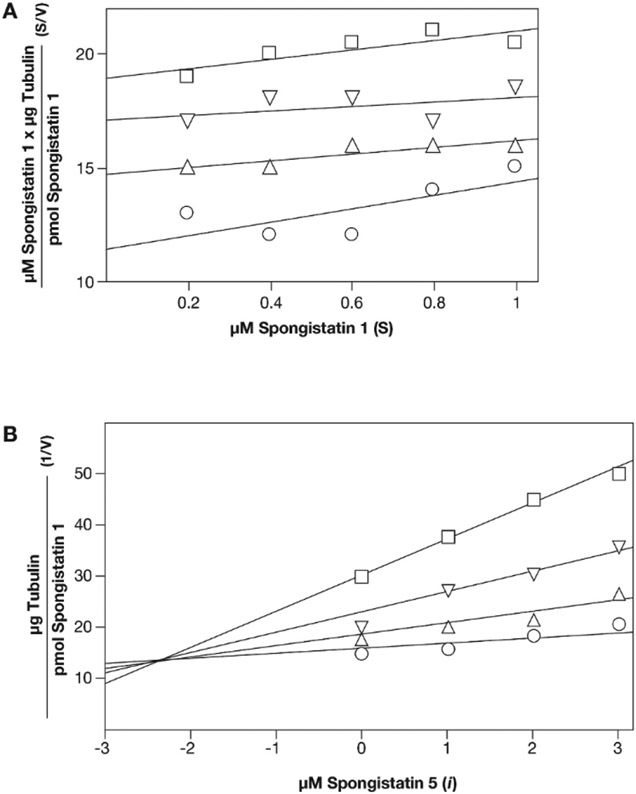

The validity of the [3H]spongistatin 1 binding assay was strengthened by a more extensive study with inhibition by spongistatin 5 (Fig. 3). We had the greatest supply of spongistatin 5 of a series of spongistatin congeners that we had previously studied [9], and thus it was selected for evaluation of potential competitive inhibition. The results obtained with this congener were most consistent with a competitive mode of inhibition, when plotted in the Hanes format where a competitive inhibitor yields a set of parallel curves [32] (Fig. 3A). The apparent Ki for spongistatin 5, obtained from a Dixon plot of the data of Fig. 3A, was 2.2 μM (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A. Competitive inhibition of [3H]spongistatin 1 binding to tubulin by spongistatin 5, as demonstrated by Hanes analysis. Reaction mixtures contained the indicated concentrations of [3H]spongistatin 1, 5.0 μM (0.5 mg/mL) tubulin, 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9), 0.5 mM MgCl2, 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide, and either no spongistatin 5 (o) or spongistatin 5 at either 1.0 (Δ), 2.0 (∇), or 3.0 (□) μM. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at room temperature before two aliquots of each reaction mixture were applied to microcolumns. B. Dixon analysis of the data of Fig. 3A. Symbols: o, 1.0 μM spongistatin 1; Δ, 0.8 μM spongistatin 1; ∇, 0.6 μM spongistatin 1;□, 0.4 μM spongistatin 1. The intercept on the negative side of the abscissa domain indicated an apparent Ki of about 2.2 μM.

Several similar experiments were performed with dolastatin 10 and cryptophycin 1, but no clear results were obtained as to the type of inhibition caused by these agents. This is perhaps consistent with the hypothesis presented above that the ring-like polymers induced by these agents masked the binding site and thus was a sort of pseudo-inhibition.

3.3. Further characterization of the binding interaction of [3H]spongistatin 1 with tubulin

As noted above, an earlier study [11] with nonradiolabeled spongistatin 1 had demonstrated, by HPLC analysis, that the compound only bound to the 100 kDa tubulin αβ-heterodimer and did not cause an aberrant assembly reaction. This finding was confirmed with the [3H]spongistatin 1 (Fig. 4). Radiolabel was found in only the 100 kDa peak and as compound unbound to protein. Studies with radiolabeled agents such as [3H]dolastatin 10 and [3H]vinblastine, depending on compound concentration, lead to radiolabel in the void volume and/or higher molecular weight included peaks [11].

Fig. 4.

Demonstration of [3H]spongistatin 1 binding to tubulin by HPLC chromatography. The reaction mixture, containing 0.75 mg/mL (7.5 μM) tubulin and 10 μM [3H]spongistatin 1, was injected into a single HPLC column (plus guard column) in a 100 μl volume. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. There was a small peak of aggregated tubulin in the void volume, and this was present when no drug was added to the tubulin, but no oligomers or polymers of tubulin induced by spongistatin 1 were observed. Detection of radiolabel. The printout of the flow detector labeled the ordinate as “cps” with the scale being from 0.0 to 220.0. Detection of protein. The printout of the HPLC system labeled the ordinate as “mV” with the scale being from 0.0 to 116.0 and the baseline at 55.0.

Our initial studies with [3H]spongistatin 1, presented above, led us to conclude that the agent bound rapidly to tubulin, at rates that could not be measured with a radiolabeled compound by techniques available to us. These studies also suggested that dissociation of [3H]spongistatin 1 from tubulin was also very slow. One approach to demonstrate this is by more extensive gel filtration. With [3H]halichondrin B, we had found that minimal radiolabel remained bound to tubulin when the drug-tubulin complex was filtered through two HPLC sizing columns in series [11]. This finding is documented again in Table 3. In contrast, the [3H]spongistatin 1 was retained by tubulin following gel filtration, not only through two columns in series, but also when three columns in series were used. These experiments demonstrated that, once bound, dissociation of [3H]spongistatin 1 from tubulin was negligible.

Table 3.

Spongistatin 1, but not halichondlin B, binds tenaciously to tubulin despite extensive HPLC chromatographya.

| Number of columns | [3H]Spongistatin 1 | [3H]Halichondrin B |

|---|---|---|

| pmol compound/pmol tubulin ± SD | ||

| 1 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.17 |

| 2 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0 |

The HPLC and radiolabel detection from column effluent was performed as described in the text. Reaction mixtures applied to the column(s) contained 10 μM tubulin, 10 μM [3H]spongistatin 1 or [3H]halichondrin B, 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9), 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide. Injection volume, 0.1 mL. Flow rate, 1.0 mL/min. The spongistatin 1 experiments were performed twice, the halichondrin B experiment once, since the data were nearly identical to previous results [11].

We also performed a Scatchard analysis of the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin (Fig. 5). The data summarized in Fig. 5 confirmed that there was only one binding site for spongistatin 1 on tubulin. These data yielded an apparent KD of 3.5 μM for the interaction of the compound with tubulin.

Fig. 5.

Scatchard analysis of the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin. Analysis of data from multiple experiments in which reaction mixtures contained the indicated concentrations of [3H]spongistatin 1, 5.0 μM (0.5 mg/mL) tubulin, 0.1 M Mes (pH 6.9), 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 4% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide, with the reaction mixtures incubated for 15 min at room temperature before two aliquots of each reaction mixture were applied to microcolumns. The data were analyzed in the Scatchard format, as indicated in the Figure.

Finally, we performed HPLC Hummel-Dreyer analysis of the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin (Fig. 6). The radiolabel in the column outflow was stable prior to injection of tubulin into the column, and, following tubulin injection, a classic Hummel-Dreyer pattern was obtained, as shown in Fig. 6: radiolabel bound to the protein, and there was a subsequent trough in the radiolabel data approximately equal in size to the protein-bound radiolabel peak, with subsequent return of radiolabel to the baseline level. Four experiments were performed, and the mean apparent KD (±S.D.) was 1.1 ± 0.3 μM, with the value from the experiment shown in Fig. 6 being 0.67 μM.

Fig. 6.

Hummel-Dreyer analysis of the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin. After the column was equilibrated with spongistatin 1, 50 μg of tubulin was injected in 100 μL, and the column was developed at a flow rate of 1.0 μL/min. Fractions (1.0 mL) were collected and analyzed for protein (200 μL) and radiolabel (100 μL), and the data were analyzed to determine the apparent KD for the binding of spongistatin 1 to tubulin, (0.67 μM in this experiment). A. Detection of radiolabel. The printout of the flow detector labeled the ordinate as “cps” with the scale being from 350.0 to just over 700.0. B. Detection of protein. The printout of the HPLC system labeled the ordinate as “mV” with the scale being from 0.0 to 30.0 and the baseline at 5.5.

4. Discussion

We commissioned the tritiation of spongistatin 1 to obtain additional understanding of its interaction with tubulin and of its potent cytotoxicity in cultured cancer cells. In all likelihood, the potent cytotoxicity of spongistatin 1 is derived from its tenacious binding to tubulin. The binding reaction was more rapid than we could measure, and the dissociation reaction was negligible. This latter property is reminiscent of those of colchicine [33] and of dolastatin 10 [34], which binds so tightly to tubulin that its efflux from cells is unmeasurable [35]. We would therefore predict that efflux of spongistatin 1 from cells would be similarly difficult to measure.

We considered that the tight binding of the [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin was caused by a covalent interaction of the compound with tubulin. However, treatment of the drug-tubulin complex with 8 M urea caused complete dissociation of radiolabel from the protein, making a covalent interaction unlikely.

We performed an extensive examination of potential inhibition of the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 by a number of vinca domain agents. Those that did not cause aberrant assembly reactions (halichondrin B and its congener eribulin and maytansine; probably rhizoxin, and possibly dolastatin 15) did not significantly inhibit [3H]spongistatin 1 binding and thus probably bind in other regions of the vinca domain. A congener of spongistatin 1, spongistatin 5, showed competitive inhibition of [3H]spongistatin 1 binding. The strongest inhibition occurred with three (depsi)peptide antimitotics, dolastatin 10, hemiasterlin, and cryptophycin 1. Kinetic analysis with dolastatin 10 and cryptophycin 1 failed to indicate a precise type of inhibition, and it is possible that this inhibition derives from the extensive aberrant assembly reactions that occur with these compounds, with the binding site masked in the aberrant polymer. This is apparently not the case with all aberrant polymers, since the vinca alkaloid vinblastine and diazonamide A, which induces ring oligomers and multi-tubulin complexes detectable by HPLC [36], had little or no inhibitory effect on the binding of [3H]spongistatin 1 to tubulin.

Perhaps the most interesting property of spongistatin 1 is its potent cytotoxicity [7,8], almost as great as that of the depsipeptide cryptophycin 1 [37]. In our hands, spongistatin 1 yielded IC50 values of 25, 25, 100, and 550 pM in the human cancer cell lines HeLa, MCF-7, OVCAR-8, and NCI/ADR-RES, the latter a Pgp-over expressing multidrug-resistant cell line otherwise isogenic with OVCAR-8. (With cryptophycin 1, we obtained IC50 values of 10, 10, 40, and 60 pM, respectively, in the four cell lines.) We have performed more extensive cytotoxic experiments with HeLa, OVCAR-8, and NCI/ADR-RES cells (Table 4), in a futile search for correlations between biochemical and cytological properties of vinca domain compounds (these data with the latter two cell lines have been published previously in the Supplemental Materials for ref. [38]). For example, there is no correlation between formation of aberrant polymer and cytotoxicity, nor between formation of aberrant polymer and overexpression of P-glycoprotein. Annoyingly, perhaps, of the compounds in Table 4 that have undergone clinical trials, eribulin, with a high relative resistance, was successful while compounds active in the P-glycoprotein overexpressing NCI/ADR-RES cells, such as dolastatin 10 and cryptophycin 1 (as a stand-in for cryptophycin 52) failed to show useful activity in human patients. Nevertheless, spongistatin 1 remains worth studying because of its potent interactions with tubulin and because of its potent effects on cancer cell growth, properties that may make it an ideal candidate for an antibody-drug conjugate.

Table 4.

Cytotoxic effects of selected vinca domain compounds in the HeLa, OVCAR-8, and NCI/ADR-RES cell linesa.

| Compound | HeLa | OVCAR-8 | NCI/ADR-RES (RRb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) ± S.D.) | |||

| No apparent formation of aberrant polymers: | |||

| Spongistatin 1 | 0.025 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.01 (5.5) |

| Halichondrin B | 0.40 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0c | 4.0 ± 1 (0.8) |

| Eribulin | 20 ± 0c | 15 ± 3 | 800 ± 200 (53) |

| Maytansine | 2.0 ± 0c | 6.0 ± 2 | 45 ± 10 (7.5) |

| Rhizoxin | 3.0 ± 1 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 16 ± 5 (6.7) |

| Formation of aberrant polymers: | |||

| Cryptophycin 1 | 0.010 ± 0.004 | 0.040 ± 0.01 | 0.060 ± 0.01 (1.5) |

| Vinblastine | 6.0 ± 3 | 30 ± 0c | 500 ± 0c (17) |

| Dolastatin 10 | 0.040 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.01 (1.8) |

| Hemiasterlin | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 3.3 ± 0.9d | 5.0 ± 0.3d (1.5) |

| Diazonamide A | 15 ± 5 | 6.0 ± 2 | 520 ± 200 (87) |

Cells were cultured for 96 h and IC50 values determined as described by Monks et al. [39].

RR (relative resistance), determined by dividing the IC50 obtained for the NCI/ADR-RES cells by that obtained for the OVCAR-8 cells. The two cell lines are isogenic except for over-expression of the P-glycoprotein gene in the former cell line.

A value of 0 for the SD indicates the same value was obtained in all experiments.

Average of two different experimental series.

In conclusion, in this study we demonstrated that spongistatin 1 binds so rapidly to tubulin that we were unable to determine an association rate, possibly because the specific activity of our [3H]spongistatin 1, prepared by a tritium exchange method, was relatively low (0.75 Ci/mmol). Conversely, once bound, there was no demonstrable dissociation of [3H]spongistatin 1 from tubulin, through extensive gel filtration chromatography. Similar apparent KD values were obtained by Scatchard and Hummel-Dreyer analysis. Our efforts to define the binding site on tubulin of spongistatin 1 indirectly were frustrated by distinct behaviors of [3H]halichondrin B and [3H]spongistatin 1 with potential vinca domain inhibitors and, particularly, by their minimal inhibitory effects on each other’s binding to tubulin. The binding site of spongistatin 1 on tubulin is thus probably best approached crystallographically.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Dr. Daniel Lee, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, for his assistance with the structural diagrams of spongistatin 1 and spongistatin 5 presented in Fig. 1. This research was supported by the Developmental Therapeutics Program in the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the National Cancer Institute, which includes federal funds under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations:

- P5

N,N-dimethylvalylvalyl-N-methylvalylprolylproline

- Mes

4-morpholineethanesulfonate

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

References

- [1].Bai R, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Binding of dolastatin 10 to tubulin at a distinct site for peptide antimitotic agents near the exchangeable nucleotide and vinca alkaloid sites, J. Biol. Chem 265 (1990) 17141–17149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bai R, Durso NA, Sackett DL, Hamel E, Interactions of the sponge-derived antimitotic tripeptide hemiasterlin with tubulin: comparison with dolastatin 10 and cryptophycin 1, Biochemistry 38 (1999) 14301–14310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bai R, Schwartz R, Kepler JA, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Characterization of the interaction of cryptophycin 1 with tubulin: binding in the vinca domain, competitive inhibition of dolastatin 10 binding, and an unusual aggregation reaction, Cancer Res. 56 (1996) 4398–4406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Edler MC, Fernandez AM, Lassota P, Ireland C, Barrows LR, Inhibition of tubulin polymerization by vitilevuamide, a bicyclic marine peptide, at a site distinct from colchicine, the vinca alkaloids, and dolastatin 10, Biochem. Pharmacol 63 (2002) 707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Khalil MW, Sasse F, Lunsdorf H, Elnakady YA, Reichenbach H, Mechanism of action of tubulysin, an antimitotic peptide from myxobacteria, Chembiochem 7 (2006) 678–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bai R, Paull KD, Herald CL, Malspeis L, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Halichondrin B and homohalichondrin B, marine natural products binding in the vinca domain of tubulin: discovery of tubulin-based mechanism of action by analysis of differential cytotoxicity data, J. Biol. Chem 266 (1991) 15882–15889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bai R, Cichacz ZA, Herald CL, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Spongistatin 1, a highly cytotoxic, sponge-derived, marine natural product that inhibits mitosis, microtubule assembly, and the binding of vinblastine to tubulin, Mol. Pharmacol 44 (1993) 757–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Crimmins MT, Katz JD, Washburn DG, Allwein SP, McAtee LF, Asymmetric total synthesis of spongistatins 1 and 2, J. Am. Chem. Soc 124 (2002) 5661–5663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bai R, Taylor GF, Cichacz ZA, Herald CL, Kepler JA, Pettit GR, Hamel E, The spongistatins, potently cytotoxic inhibitors of tubulin polymerization, bind in a distinct region of the vinca domain, Biochemistry 34 (1995) 9714–9721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dabydeen DA, Burnett JC, Bai R, Verdier-Pinard P, Hickford SJH, Pettit GR, Blunt JW, Munro MHG, Gussio R, Hamel E, Comparison of the activities of the truncated halichondrin B analog NSC 707389 (E7389) with those of the parent compound and a proposed binding site on tubulin, Mol. Pharmacol 70 (2006) 1866–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bai R, Nguyen TL, Burnett JC, Atasoylu O, Munro MHG, Pettit GR, Smith AB III, Gussio R, Hamel E, Interactions of halichondrin B and eribulin with tubulin, J. Chem. Inf. Model 51 (2011) 1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gigant B, Wang C, Ravelli RBG, Roussi F, Steinmetz MO, Curmi PA, Sobel A, Knossow M, Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine, Nature 435 (2005) 519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cormier A, Marchand M, Ravelli RBG, Knossow M, Gigant B, Structural insight into the inhibition of tubulin by vinca domain peptide ligands, EMBO Rep. 9 (2008) 1101–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Prota AE, Bargsten K, Díaz JF, Marsh M, Cuevas C, Liniger M, Neuhaus C, Andreu JM, Altmann K-H, Steinmetz MO, A new tubulin-binding site and pharmacophore for microtubule-destabilizing anticancer drugs, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 111 (2014) 13817–13821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang Y, Benz FW, Wu Y, Wang Q, Chen Y, Chen X, Li H, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Yang J, Structural insights into the pharmacophore of vinca domain inhibitors of microtubules, Mol. Pharmacol 89 (2016) 233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Doodhi H, Prota AE, Rodríguez-García R, Xiao H, Custar DW, Bargsten K, Katrukha EA, Hilbert M, Hua S, Jiang K, Grigoriev I, Yang C-PH, Cox D, Horwitz SB, Kapitein LC, Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO, Termination of protofilament elongation by eribulin induces lattice defects that promote microtubule catastrophes, Curr. Biol 26 (2016) 1713–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Waight AB, Bargsten K, Doronina S, Steinmetz MO, Sussman D, Prota AE, Structural basis of microtubule destabilization by potent auristatin antimitotics, PLoS One (2016), 10.1371/journal.pone.0160890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wieczorek M, Tcherkezian J, Bernier C, Prota AE, Chaaban S, Rolland Y, Godbout A, Hancock MA, Arezzo JC, Ocal O, Rocha C, Olieric N, Hall A, Ding H, Bramoullé A, Annis MG, Zogopoulos G, Harran PG, Wilkie TW, Brekken RA, Siegel PM, Steinmetz MO, Shore GC, Brouhard GJ, Roulstan A, The synthetic diazonamide DZ-2384 has distinct effects on microtubule curvature and dynamics without neurotoxicity, Sci. Transl. Med 8 (2016), 365ra159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sáez-Calvo G, Sharma A, Balaguer F, Barasoain I, Rodríguez-Salrichs J, Olieric N, Muñoz-Hernández H, Berbís MÁ, Wnedebom S, Peñalva MA, Matesanz R, Canales Á, Prota AE, Jímenez-Barbero J, Andreu JM, Lamberth C, Steinmetz MO, Díaz JF, Triazolopyrimidines are microtubule-stabilizing agents that bind the vinca inhibitor site of tubulin, Cell Chem. Biol 24 (2017) 737–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cruz-Monserrate Z, Vervoort HC, Bai R, Newman DJ, Howell SB, Los G, Mullaney JT, Williams MD, Pettit GR, Fenical W, Hamel E, Diazonamide A and a synthetic structural analog: disruptive effects on mitosis and cellular microtubules and analysis of their interactions with tubulin, Mol. Pharmacol 63 (2003) 1273–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bai R, Edler MC, Bonate PL, Copeland TD, Pettit GR, Ludueña RF, Hamel E, Intracellular activation and deactivation of tasidotin, an analog of dolastatin 15: correlation with cytotoxicity, Mol. Pharmacol 75 (2009) 218–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rothmeir A, Schneiders UM, Wiedmann RM, Ischenko I, Bruns CJ, Rudy A, Zahler S, Vollmar AM, The marine compound spongistatin 1 targets pancreatic tumor progression and metastasis, Int. J. Cancer 127 (2010) 1096–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xu Q, Huang K-C, Tendyke K, Marsh J, Liu J, Qiu D, Littlefield BA, Nomoto K, Atasoylu O, Risatti CA, Sperry JB, Smith III AB, In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of (+)-spongistatin 1, Anticancer Res. 31 (2011) 2773–2780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Beck A, Dumontet C, Joubert N, Antibody-drug conjugates in oncology. Recent success of an ancient concept, M S-Med. Sci 35 (2020) 1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hamel E, Lin CM, Separation of active tubulin and microtubule-associated proteins by ultracentrifugation and isolation of a component causing the formation of microtubule bundles, Biochemistry 23 (1984) 4173–4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Grover S, Hamel E, The magnesium-GTP interaction in microtubule assembly, Eur. J. Biochem 222 (1994) 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Smith AB III, Sfouggatais C, Risatti CA, Sperry JB, Zhu W, Doughty VA, Tomioka T, Gotchev DB, Bennett CS, Sakamoto S, Atasoylu O, Shirakami S, Bauer D, Takeuchi M, Koyanagi J, Sakamoto Y, Spongipyran synthetic studies. Evolution of a scalable total synthesis of (+)-spongistatin 1, Tetrahedron 65 (2009) 6489–6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pettit GR, Singh SB, Hogan F, Lloyd-Williams P, Herald DL, Burkett DD, Clewlow PJ, The absolute configuration and synthesis of natural (−)-dolastatin 10, J. Am. Chem. Soc 111 (1989) 5463–5465. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gamble WR, Durso NA, Fuller RW, Westergaard CK, Johnson TR, Sackett DL, Hamel E, Cardellina II JH, Boyd MR, Cytotoxic and tubulin-interactive hemiasterlins from Auletta sp. and Siphonochalina spp. sponges, Bioorg. Med. Chem 7 (1999) 1611–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lindquist N, Fenical W, Van Duyne GD, Clardy J, Isolation and structure determination of diazonamides A and B, unusual cytotoxic metabolites from the marine ascidian Diazona chinensis, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 (1991) 2303–2304 (Note that the original voucher specimen was misidentified as D. chinensis and was later corrected to D. angulata). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hamel E, Lin CM, Guanosine 5’-O-(3-thiotriphosphate), a potent nucleotide inhibitor of microtubule assembly, J. Biol. Chem 259 (1984) 11060–11069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dixon M, Webb EC, Thorne CJR, Tipton KF, Enzymes, third ed.. Academic Press, New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hastie SB, Interactions of colchicine with tubulin, Pharmacol. Ther 51 (1991) 377–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bai R, Taylor GF, Schmidt JM, Williams MD, Kepler JA, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Interactions of dolastatin 10 with tubulin: induction of aggregation and binding and dissociation reactions, Mol. Pharmacol 47 (1995) 965–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Verdier-Pinard P, Kepler JA, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Sustained intracellular retention of dolastatin 10 causes its potent antimitotic activity, Mol. Pharmacol 57 (2000) 180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bai R, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Fenical W, Pettit GR, Hamel E, Interaction of diazonamide A with tubulin, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 680 (2020), 108217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Smith CD, Zhang X, Mooberry SL, Patterson GML, Moore RE, Cryptophycin: a new antimicrotubule agent active against drug-resistant cells, Cancer Res. 54 (1994) 3779–3784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Peerzada MN, Hamel E, Bai R, Supuran CT, Azam A, Deciphering the key heterocyclic scaffolds in targeting microtubules, kinases and carbonic anhydrases for cancer drug development, Pharmacol. Ther 225 (2021), 107860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Monks A, Scudiero D, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Wolff A, Gray-Goodrich M, Campbell H, Mayo J, Boyd M, Feasibility of a high-flux anticancer drug screen using a diverse panel of cultured human tumor cell lines, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 83 (1991) 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]