Abstract

In this IMR Country Report, we draw attention to Costa Rica as a strategic location for expanding research and theory on migrants in need of protection (MNP), who have migrated abroad primarily to evade an imminent threat to their survival. MNP constitute an increasing share of all international migrants in Costa Rica and worldwide, yet research on these migrants and their migration dynamics remains comparatively underdeveloped relative to research on migrants who relocate abroad primarily in pursuit of material gains, social status, or family reunification. As we highlight, Costa Rica is an instrumental site to deepen understandings of MNP populations and migration dynamics because its large and rapidly growing MNP population is incredibly diverse with respect to national origins, demographic characteristics, and underlying motivations for migration. This diversity presents ample opportunities to better understand heterogeneity in the different types of threats MNP seek to evade; how and why MNP incorporation is shaped by individuals’ demographic attributes and pre-migration threats; and how the social networks of various MNP subpopulations develop and overlap with time. Moreover, the geographic concentration of MNP in two regions in Costa Rica lends itself to primary data collection among this population and generates opportunities for estimating local MNPs’ demographic characterization, even in the absence of a reliable sampling frame.

Introduction

Migrants “in need of international protection” (MNP)—refugees and internationally displaced migrants in “refugee-like situations” who move abroad to evade imminent threats to their survival—account for an increasing share of all international migrants worldwide (United Nations 2017; UNHCR 2018c). Although there is no universally held definition of MNP, we conceive of this population as including refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, asylum-seekers, stateless persons, Palestinian refugees under UNRWA’s mandate, Venezuelans and Syrians displaced abroad, and others whom the UNHCR deems “persons of concern.” Defined this way, international MNP more than doubled during the 2010s, from 20.8 to 46.8 million (UNHCR 2021).1 Despite this growth, most demographic and sociological studies of migrants continue to overlook MNP, whose migration is primarily motivated by threat evasion, or “the desire to escape an immediate threat to emotional or physical wellbeing” (Massey 2018, p. 4; see also Davenport, Moore and Poe 2003; Holland and Peters 2020). Instead, past literature tends to focus on migration motivated by material gains, economic risk diversification, social connections, or social status (for reviews, see Massey et al. 1999; Delgado-Wise 2014; Lee, Carling and Orrenius 2014), Consequently, much remains unknown about MNPs’ push and pull factors, living conditions, societal incorporation, family dynamics, and health outcomes.

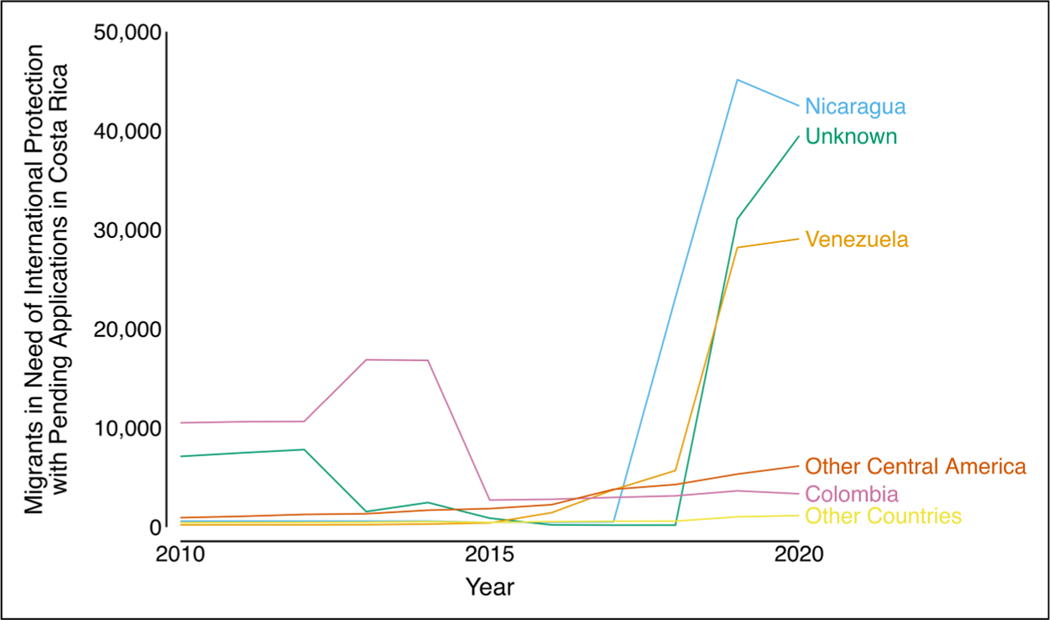

In this IMR Country Report, we draw attention to Costa Rica—a small, politically stable, middle-income country in southern Central America—as a strategic locale to expand research and theory on threat evasion and MNP. Our perspective is informed by our ongoing research in the country, including focus groups, in-depth interviews, surveys with MNP, and informal conversations with local MNP service providers, conducted since 2019. Costa Rica, we suggest, is illustrative of the global explosion of MNP because its estimated MNP population grew from approximately 8,000 in 2016 to 122,000 in 2020 (UNHCR 2021), alongside worsening gang and drug violence, economic crises, and political turmoil in Latin America (UNHCR 2018a). Today, Costa Rica receives a combination of northbound and southbound MNP, most of whom originate from Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, or elsewhere in Central America (Figure 1, UNHCR Data Finder 2021). Costa Rica, thus, provides a unique opportunity to study a diverse and rapidly growing MNP population in a middle-income country, with notable implications for migration scholars’ understanding of South-South migration, of the different threats MNP seek to evade and their impacts on MNPs’ incorporation, of the development of social networks among different MNP subpopulations, and of the implications of MNP population growth for receiving contexts.

Figure 1.

Migrants in need of international protection with pending applications in Costa Rica, by country of origin. Note: We calculate these estimates with data from the UNHCR’s Refugee Data Finder: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/. See Footnote 1 for further information.

Costa Rica as a Destination

Starting in the 1960s and continuing through the 1990s, Costa Rica received thousands of migrants evading civil and political conflicts in Nicaragua, Colombia, Cuba, Argentina, and Chile (OECD and Fundación de la Universidad de Costa Rica para la Investigación 2017). For many MNP, Costa Rica’s political stability and lack of military have been appealing pull factors (Walker Gates 2019), as has been its free public education, which is available to migrant children, including those with irregular status (Walker Gates 2019). While Nicaraguans need a visa to enter the country, most other nationalities do not (DGME 2021), although Costa Rica did begin requiring visas for Venezuelans in February 2022 (Murillo 2022).2

Although technically legal in Costa Rica, the detention of immigrants with irregular status is rare and treated as a last resort, with only 1,637 migrants deported in 2019 (DGME 2019) and only one small detention center with a total capacity of 50 people (Global Detention Project 2020). Those who are denied asylum in Costa Rica are typically encouraged to appeal their cases or to find alternative means to remain in the country legally, such as through employment (Walker Gates 2019).3

Alongside its increasing number of MNP, Costa Rica continually hosts a large number of economic migrants, despite higher unemployment levels than most other Latin American countries (World Bank 2021). Most economic migrants in Costa Rica originate from Nicaragua or Panama (Voorend and Rivera 2012; Groh and José 2017) and work seasonally in agriculture or tourism or work longer term in domestic services (Otterstrom 2008; Vandegrift 2008; Groh and José 2017). Beyond economic migrants and MNP, Costa Rica continually receives migrant entrepreneurs and retirees from high-income countries (Morales-Gamboa 2008; Groh and José 2017; Chaves González and Mora 2021).

Studying Threat Evasion and MNP in Costa Rica

While Costa Rica receives both economic migrants and MNP, research on migration to Costa Rica tends to focus more on the former than on the latter (Groh and José 2017), paralleling global trends in the study of migration (as outlined by Delgado-Wise 2014; Lee, Carling and Orrenius 2014; and Massey et al. 1999). That is, the vast majority of scholarship on migration to Costa Rica investigates economic migration from Panama or Nicaragua, transnational families straddling these countries, or policies regarding them (Borge 2006; Morales-Gamboa 2008; Brenes-Camacho 2010; Sandoval García 2010; Fouratt 2014; Winters 2014; Groh and José 2017).

The handful of studies explicitly examining MNP in Costa Rica tend to focus on MNP who arrived 20 to 40 years ago. Specifically, these studies track when and where Nicaraguan refugees resettled in Costa Rica in the 1980s (Larson 1993); examine the government’s policy responses to MNP inflows from Nicaragua and El Salvador in the 1980s and early 2000s (Basok 1990; Larson 1992; Fouratt 2014); and investigate how the Costa Rican government’s immigration policy affected Cuban MNP in the 1980s (Fernández and Narváez 1987). Together, this small body of work documents the evolution of Costa Rican immigration policy between the 1980s and early 2000s and these policies’ implications for select MNP populations in the country. What these studies leave open, however, are pivotal questions about the current numbers and organization of MNP, the different precipitating threats of distinct MNP subpopulations, and the implications of various threats for MNPs’ health and wellbeing, family dynamics, and incorporation into Costa Rica. For instance, it remains unclear which MNP are most likely to apply for asylum in the country and what determines whether they stay, return, or migrate elsewhere if their asylum claim is denied. Likewise, little is understood about the linkages between prior and successive waves of MNP in Costa Rica or whether social networks of MNP from diverse backgrounds overlap.

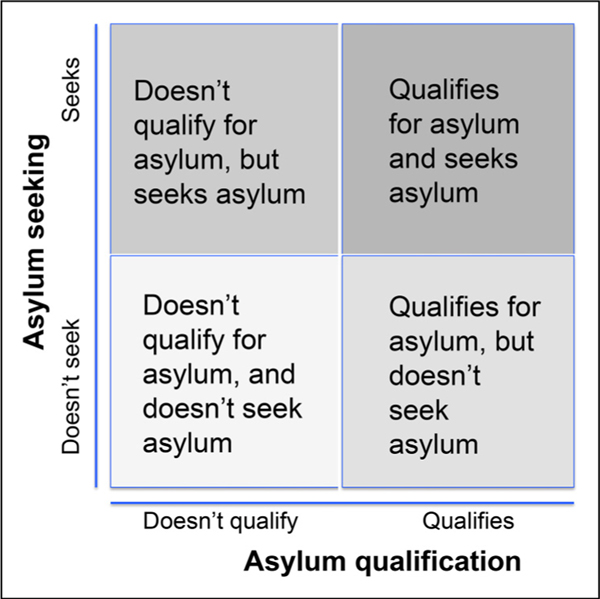

Answering these questions in Costa Rica and elsewhere is complicated by several factors. First, no reliable sampling frame for MNP exists, both because there is no universally agreed-upon definition of MNP (FitzGerald and Arar 2018) and because some MNP avoid immigration institutions altogether (Larson 1993). For instance, drawing on a list of asylum applications from the Ministry of Migration or UNHCR risks excluding MNP who do not apply for asylum, even if eligible (Figure 2). Drawing on a list of all visa applicants may similarly miss MNP who never register in the country or who overstay their visa. Moreover, drawing on a list of all visa applicants would be inefficient, given that many visa-holders may migrate for reasons not related to threat evasion.

Figure 2.

Asylum qualification and seeking Among migrants in need of international protection.

Second, in most reception contexts, including in Costa Rica, MNP’s socioeconomic conditions can make them hard to reach. Some may be too poor to access the Internet or keep a cellphone connected regularly, which impedes initiating and maintaining contact with them (Jauhiainen, Özçürümez and Tursun 2021). Others may be mistrusting of strangers or socially isolated, particularly if they did not arrive in Costa Rica through social network connections (Turner 1995; Arar 2016; Greene 2019). Third, even when MNP can be reached, they can be difficult to follow over time because their liminal legality and low economic status exacerbate their risk of eviction, homelessness, and housing instability (Kissoon 2010). Likewise, being in an economically vulnerable position can lead MNP to prioritize income opportunities above all else (Verwiebe et al. 2019), thereby impeding their research participation.

Given these challenges, few representative studies of MNP exist anywhere in the world (for a description of notable exceptions, see Enticott et al. 2017).4 Moreover, only a handful of studies follow MNP longitudinally, including the Indochinese Health and Adaptation Research Project (IHARP), which surveyed a sample of Southeast Asian refugee households in San Diego twice in the 1980s (Rumbaut and Weeks 1989); the Somali Youth Longitudinal Study, which surveyed a panel of adolescent Somali refugees across five major North American cities (Salhi et al. 2021); and the Building a New Life in Australia Study, which surveyed a diverse sample of humanitarian visa applicants four times between 2013 and 2018 (Wu et al. 2021). Two other recent studies collected multiple rounds of data in refugee camps in Bangladesh and Kenya (Egger et al. 2021; Lopez-Pena et al. 2021).

Overall, these panel studies offer new insights into the health challenges and gradual, yet limited, incorporation of (documented) refugees. At the same time, they stem from data collected on select MNP populations in only a few cities in Australia, Canada, and the United States and in refugee camps in Bangladesh and Kenya. The vast majority of MNP, however, do not reside in camps or wealthy countries (UNHCR 2021), and MNP resettlement patterns may differ widely as a function of social safety net accessibility, employment and educational opportunities, language barriers, and racial and ethnic discrimination (UNHCR 2018b; Blair, Grossman and Weinstein 2021). Diversifying the study contexts of MNP to be more inclusive of migrants living outside refugee camps and relocating to lower-and middle-income countries like Costa Rica is, therefore, crucial to expanding understandings of the lived realities of millions of MNP worldwide.

Opportunities for Studying Threat Evasion and MNP in Costa Rica

By many metrics, Costa Rica’s socioeconomic conditions are similar to those encountered by MNP in various other middle-income countries like Chile and Panama in Latin America or Malaysia and Thailand in Southeast Asia. Anecdotal evidence from our fieldwork suggests that most MNP in Costa Rica resettle either in San José and the surrounding Central Valley or along the Nicaraguan border. In both cases, MNP’s geographic concentration makes it easier to collect plausibly representative samples using methods like respondent-driven sampling (Tyldum and Johnston 2014) because this concentration indicates that MNP social networks are already taking shape. Moreover, MNP’s geographic concentration should reduce barriers to their retention in longitudinal studies by making it easier for most participants to access strategically located study offices.

Costa Rica’s large and growing MNP population, which is diverse in its national origins (Figure 1), encompasses a wide range of precipitating threats, ranging from gang and drug violence to civil conflict, persecution, and natural disasters. It also includes both established and more recently arrived MNP (OECD and Fundación de la Universidad de Costa Rica para la Investigación 2017). This diversity presents unique opportunities to understand how different types of precipitating threats and background characteristics affect MNP’s incorporation, network development, and familial and health trajectories, while holding their reception context constant. What is more, much of the research on MNP focuses on sub-populations originating from sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, or Southeast Asia and resettling in the United States, Europe, or Australia (e.g., Porter and Haslam 2005; Ellis et al. 2008; Fazel et al. 2012; Reed et al. 2012). Given Costa Rica’s location in Latin America and given its reception of predominantly Latin American MNP, it is well suited for developing a foundational understanding of the causes and consequences of threat evasion as a process of South-South migration.

Studying MNP in Costa Rica also offers theoretical advancements for research on contemporary international migration more broadly. What long-term consequences does forced international migration have on people’s identity formation, aspirations, and patterns of behavior (see Pugh 2018)? How does the arrival of MNP alter the social dynamics of receiving countries like Costa Rica and sending countries like Venezuela and Nicaragua (see Zhou and Shaver 2021)? Are the uncertainty and instability that MNP experience comparable to that experienced during other traumatic events, including violent conflict, political alienation, and community disintegration (see Betancourt et al. 2015)? More broadly, how do answers to these questions differ between MNP who are politically recognized as refugees or asylees and MNP who are not?

Beyond these theoretical insights, the study of MNP in Costa Rica offers methodological contributions for research on hard-to-reach migrant populations, including adapting sophisticated chain referral methods (like respondent-driven sampling) to estimate population parameters in the absence of a reliable sampling frame; characterizing the network linkages between current and earlier MNP arrivals and between MNP and other types of migrants; and developing strategies for successfully retaining vulnerable and highly mobile migrants such as MNP in longitudinal surveys.

Concluding Thoughts

Costa Rica’s geographic, political, and infrastructural characteristics make it ideally suited to develop new data sources on a large and growing MNP population. Such data sources are pivotal to making inferences about MNP population parameters and dynamics, to understanding a fuller range of MNP threat profiles, and to tracking how MNPs’ incorporation unfolds over time. Studies of Costa Rica’s growing and diverse MNP population can, thus, enhance migration scholars’ understanding of threat evasion and its personal and societal implications, in comparison to economically and socially motivated migration more traditionally explored in migration studies (Massey et al. 1999; Delgado-Wise 2014; Lee, Carling and Orrenius 2014). Ultimately, expanding data on threat evasion and MNP in Costa Rica promises to bolster knowledge of the migration dynamics and experiences of people who become uprooted because of targeted or pervasive violence, political turmoil, disasters, and other pressing threats. Each year, such migrants account for a growing percentage of all migrants worldwide, most of whom resettle in low- or middle-income countries like Costa Rica (UNPD 2017). Our understandings of this expanding migrant population can be enhanced by developing new, comprehensive data sources that track the experiences and growth of MNP populations in Costa Rica, which subsequently can inform research in other countries in the Global South, where MNP inflows are steadily increasing.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible with funding from a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (K01HD099313, PI Weitzman) and with a population center grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin (P2CHD042849). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, (grant number K01HD099313, P2CHD042849).

Footnotes

Our estimates of MNP globally and in Costa Rica come from UNHCR’s Refugee Data Finder: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

To enter Costa Rica, foreigners need a passport that is valid for at least three months after arrival (Embajada de Costa Rica en Washington D.C. 2022).

Transcontinental MNP also increasingly pass through Costa Rica in transit to the United States (Selee et al. 2021). In contrast to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, Costa Rica has not signed an “Asylum Cooperative Agreement” with the United States (Blinken 2021).

For two more recent exceptions, see Koning et al. (2021) and Lopez-Pena et al. (2021).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Abigail Weitzman, Department of Sociology & Population Research Center, University of Texas.

Gilbert Brenes Camacho, Centro Centroamericano de Población, Universidad de Costa Rica.

Arodys Robles, Centro Centroamericano de Población, Universidad de Costa Rica.

Matthew Blanton, Department of Sociology & Population Research Center, University of Texas.

Jeffrey Swindle, Population Research Center, University of Texas.

Katarina Huss, Department of Sociology & Population Research Center, University of Texas.

References

- Arar Rawan Mazen. 2016. “How Political Migrants’ Networks Differ from Those of Economic Migrants: ‘Strategic Anonymity’ Among Iraqi Refugees in Jordan.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (3): 519–35. 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1065716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basok Tanya. 1990. “Welcome Some and Reject Others: Constraints and Interests Influencing Costa Rican Policies on Refugees.” International Migration Review 24 (4): 722–47. 10.1177/019791839002400404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt Theresa S., Abdi Saida, Ito Brandon S., Lilienthal Grace M., Agalab Naima, and Ellis Heidi. 2015. “We Left One War and Came to Another: Resource Loss, Acculturative Stress, and Caregiver–Child Relationships in Somali Refugee Families.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 21 (1): 114–25. 10.1037/a0037538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair Christopher W., Grossman Guy, and Weinstein Jeremy M.. 2021. “Liberal Displacement Policies Attract Forced Migrants in the Global South.” American Political Science Review 116 (1): 351–358. 10.1017/S0003055421000848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blinken, Secretary of State Anthony J. 2021. “Suspending and Terminating the Asylum Cooperative Agreements with the Governments El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.” US Department of State Press Statement. Retrieved September 24, 2021 https://www.state.gov/suspending-and-terminating-the-asylum-cooperative-agreements-with-the-governments-el-salvador-guatemala-and-honduras/. [Google Scholar]

- Borge Dalia. 2006. “Migración y Políticas Públicas: Elementos a Considerar para la Administración de las Migraciones entre Nicaragua y Costa Rica.” Población y Salud en Mesoamérica 3 (2): 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brenes-Camacho Gilbert. 2010. “The Electoral Cycle of International Migration Flows from Latin America.” Genus 66 (3): 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves González Diego, and Mora María Jesús. 2021. “El Estado de la Política Migratoria y de Integración de Costa Rica.” Migration Policy Institute. November 2021. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/politica-migratoria-integracion-costa-rica. [Google Scholar]

- Groh Chaves, and José María. 2017. “Costa Rica En La Migracion Regional Perspectivas Recientes (2000–2014).” Revista de Ciencias Sociales 157: 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport Christina, Moore Will, and Poe Steven. 2003. “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave: Domestic Threats and Forced Migration, 1964–1989.” International Interactions 29 (1): 27–55. 10.1080/03050620304597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Wise Raúl. 2014. “A Critical Overview of Migration and Development: The Latin American Challenge.” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (1): 643–63. 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Migración Dirección General y de la República de Costa Rica Extranjeria. 2021. “Visa Arribo: Tercer Grupo.” Retrieved May 15, 2021. https://www.migracion.go.cr/Documentos%20compartidos/Visas/Visa%20de%20Arribo.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- de Migración Dirección General y Extranjeria (DGME) de la República de Costa Rica. 2019. Informe Anual 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Egger Dennis, Miguel Edward, Warren Shana S., Shenoy Ashish, Collins Elliott, Karlan Dean, Parkerson A. Doug, et al. 2021. “Falling Living Standards During the COVID-19 Crisis: Quantitative Evidence from Nine Developing Countries.” Science Advances 7 (6): eabe0997. 10.1126/sciadv.abe0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B.Heidi, MacDonald Helen Zelia, Lincoln Alisa K., and Cabral Howard J.. 2008. “Mental Health of Somali Adolescent Refugees: The Role of Trauma, Stress, and Perceived Discrimination.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76 (2): 184–93. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embajada de Costa Rica en Washington D.C. 2022. “Visas by Nationality.” Accessed on January 25, 2022. http://www.costarica-embassy.org/index.php?q=node/51.

- Enticott Joanne C., Shawyer Frances, Vasi Shiva, Buck Kimberly, Cheng I.-Hao, Russell Grant, Kakuma Ritsuko, Minas Harry, and Meadows Graham. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Studies with a Representative Sample of Refugees and Asylum Seekers Living in the Community for Participation in Mental Health Research.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 17 (1): 37. 10.1186/s12874-017-0312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel Mina, Reed Ruth V., Panter-Brick Catherine, and Stein Alan. 2012. “Mental Health of Displaced and Refugee Children Resettled in High-Income Countries: Risk and Protective Factors.” The Lancet 379 (9812): 266–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)600512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Gastón, and Narváez León. 1987. “Refugees and Human Rights in Costa Rica: The Mariel Cubans.” International Migration Review 21 (2): 406–15. 10.1177/019791838702100209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald David Scott, and Arar Rawan. 2018. “The Sociology of Refugee Migration.” Annual Review of Sociology 44 (1): 387–406. 10.1146/annurev-soc073117-041204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouratt Caitlin E. 2014. “‘Those Who Come to Do Harm’: The Framings of Immigration Problems in Costa Rican Immigration Law.” International Migration Review 48 (1): 144–80. 10.1111/imre.12073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Detention Project. 2020. “Costa Rica Immigration Detention Profile.” Global Detention Project. Retrieved September 23, 2021. https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/americas/costa-rica. [Google Scholar]

- Greene R.Neil. 2019. “Kinship, Friendship, and Service Provider Social Ties and How They Influence Well-Being among Newly Resettled Refugees.” Socius 5. 10.1177/2378023119896192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland Alisha C., and Peters Margaret E.. 2020. “Explaining Migration Timing: Political Information and Opportunities.” International Organization 74 (3): 560–83. 10.1017/S002081832000017X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jauhiainen Jussi S., Özçürümez Saime, and Tursun Özgün. 2021. “Internet and Social Media Uses, Digital Divides, and Digitally Mediated Transnationalism in Forced Migration: Syrians in Turkey.” Global Networks 22 (2): 197–210. 10.1111/glob.12339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kissoon Priya. 2010. “From Persecution to Destitution: A Snapshot of Asylum Seekers’ Housing and Settlement Experiences in Canada and the United Kingdom.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 8 (1): 4–31. 10.1080/15562940903575020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koning Stephanie M., Scott Kaylee, Conway James H., and Palta Mari. 2021. “Reproductive Health at Conflict Borders: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Human Rights Violations and Perinatal Outcomes at the Thai-Myanmar Border.” Conflict and Health 15 (1): 1–10. 10.1186/s13031-021-00347-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson Elizabeth M. 1992. “Costa Rican Government Policy on Refugee Employment and Integration, 1980–1990.” International Journal of Refugee Law 4 (3): 326–42. 10.1093/ijrl/4.3.326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- />Larson Elizabeth M. 1993. “Nicaraguan Refugees in Costa Rica from 1980–1993 Yearbook.” Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers 19: 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jennifer, Carling Jørgen, and Orrenius Pia. 2014. “The International Migration Review at 50: Reflecting on Half a Century of International Migration Research and Looking Ahead.” International Migration Review 48 (1_suppl): 3–36. 10.1111/imre.12144.24791036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Pena Paula, Davis C. Austin, Mobarak A. Mushfiq, and Raihan Shabib. 2020. “Prevalence of COVID-19 Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Health Behaviors in Host and Refugee Communities in Cox’s Bazar: A Representative Panel Study.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 11 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. 2018. “The Perils of Seeing Twenty-First Century Migration Through a Twentieth-Century Lens.” International Social Science Journal 68 (227–228): 101–4. 10.1111/issj.12173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Arango Joaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, and Pellegrino Adela. 1999. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Gamboa Abelardo. 2008. Inmigración en Costa Rica: Características Sociales y Laborales, Integración y Políticas Públicas. Santiago de Chile: Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía, División de Población de la Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo Alvaro. 2022. “Costa Rica Imposes Visa Requirements for Venezuelans as Migration Surges.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/costa-rica-imposes-visarequirements-venezuelans-migration-surges-2022-02-17/. Accessed on Feb. 18, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and Fundación de la Universidad de Costa Rica para la Investigación. 2017. Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development in Costa Rica. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Otterstrom Samuel M. 2008. “Nicaraguan Migrants in Costa Rica during the 1990s: Gender Differences and Geographic Expansion.” Journal of Latin American Geography 7 (2): 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Matthew, and Haslam Nick. 2005. “Predisplacement and Postdisplacement Factors Associated With Mental Health of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: A Meta-Analysis.” JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 294 (5): 602–12. 10.1001/jama.294.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh Jeffrey D. 2018. “Negotiating Identity and Belonging through the Invisibility Bargain: Colombian Forced Migrants in Ecuador.” International Migration Review 52 (4): 978–1010. 10.1111/imre.12344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed Ruth V., Fazel Mina, Jones Lynne, Panter-Brick Catherine, and Stein Alan. 2012. “Mental Health of Displaced and Refugee Children Resettled in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: Risk and Protective Factors.” The Lancet 379 (9812): 250–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut Rubén G., and Weeks John. 1989. “Infant Health Among Indochinese Refugees: Patterns of Infant Mortality, Birthweight and Prenatal Care in Comparative Perspective.” Research in the Sociology of Health Care 8: 137–96. [Google Scholar]

- Salhi Carmel, Scoglio Arielle A. J., Ellis Heidi, Issa Osob, and Lincoln Alisa. 2021. “The Relationship of Pre- and Post-Resettlement Violence Exposure to Mental Health Among Refugees: A Multi-Site Panel Survey of Somalis in the Us and Canada.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56 (6): 1015–23. 10.1007/s00127-020-02010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval García Carlos. 2010. Shattering Myths on Immigration and Emigration in Costa Rica. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Selee Andrew, Ruiz Soto Ariel G., Tanco Andrea, Argueta Luis, and Bolter Jessica. 2021. Laying the Foundation for Regional Cooperation: Migration Policy & Institutional Capacity in Mexico and Central America. Washington D.C.: Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Turner Stuart. 1995. “Torture, Refuge, and Trust.” In Mistrusting Refugees, edited by Daniel EV and Knudsen J. Chr., 56–72. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyldum Guri, and Johnston Lisa. 2014. Applying Respondent Driven Sampling to Migrant Populations: Lessons from the Field. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2018b. UNHCR Mapping of Social Safety Nets for Refugees: Opportunities and Challenges. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2018c. As Venezuelans Flee Throughout Latin America, UNHCR Issues New Protection Guidance. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2021. “Refugee Data Finder.” Retrieved May 14, 2021 (www.unhcr.org/refugeestatistics/download).

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2018a. UNHCR Global Report 2018 - The Americas Regional Summary. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD). 2017. Population Facts. December 2017. (https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFacts_2017-5.pdf ).

- UN (United Nations). 2017. International Migration Report 2017: Highlights. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Vandegrift Darcie. 2008. “‘This Isn’t Paradise—I Work Here’: Global Restructuring, the Tourism Industry, and Women Workers in Caribbean Costa Rica.” Gender & Society 22 (6): 778–98. 10.1177/0891243208324999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verwiebe Roland, Kittel Bernhard, Dellinger Fanny, Liebhart Christina, Schiestl David, Haindorfer Raimund, and Liedl Bernd. 2019. “Finding Your Way into Employment Against All Odds? Successful Job Search of Refugees in Austria.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (9): 1401–18. 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1552826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voorend Koen, and Rivera Francisco Robles. 2012. “Migración y Crisis en Costa Rica: Los Rasgos Estructurales de la Demanda de Obra Regional.” Apuntes del Mercado Laboral. III. Organización Internacional del Trabajo y Observatorio Laboral Centroamérica y Repúblic Dominicana. [Google Scholar]

- Gates Walker, Jennifer. 2019. “Costa Rican Asylum – 10 Things to Know.” Walker Gates Vela - Attorneys at Law. Retrieved June 11, 2021 (https://walkergatesvela.com/costa-ricanasylum-10-things-to-know/). [Google Scholar]

- Winters Nanneke. 2014. “Responsibility, Mobility, and Power: Translocal Carework Negotiations of Nicaraguan Families.” International Migration Review 48 (2): 415–41. 10.1111/imre.12062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2021. “World Development Indicators: Unemployment, Total (Percent of Total Labor Force) (Modeled ILO Estimate).” Retrieved September 21, 2021 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS).

- Wu Shuxian, Renzaho Andre M. N., Hall Brian J., Shi Lishuo, Ling Li, and Chen Wen. 2021. “Time-Varying Associations of Pre-Migration and Post-Migration Stressors in Refugees’ Mental Health During Resettlement: A Longitudinal Study in Australia.” The Lancet Psychiatry 8 (1): 36–47. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Yang-Yang, and Shaver Andrew. 2021. “Reexamining the Effect of Refugees on Civil Conflict: A Global Subnational Analysis.” American Political Science Review 115 (4): 1175–1196. 10.1017/S0003055421000502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]