Abstract

Purpose

Measuring the impact burn injuries have on social participation is integral to understanding and improving survivors’ quality of life, yet there are no existing instruments that comprehensively measure the social participation of burn survivors. This project aimed to develop the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation Profile (LIBRE), a patient-reported multidimensional assessment for understanding the social participation after burn injuries.

Methods

192 questions representing multiple social participation areas were administered to a convenience sample of 601 burn survivors. Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were used to identify the underlying structure of the data. Using item response theory methods, a Graded Response Model was applied for each identified sub-domain. The resultant multidimensional LIBRE Profile can be administered via Computerized Adaptive Testing (CAT) or fixed short forms.

Results

The study sample included 54.7% women with a mean age of 44.6 (SD 15.9) years. The average time since burn injury was 15.4 years (0–74 years) and the average total body surface area burned was 40% (1–97%). The CFA indicated acceptable fit statistics (CFI range 0.913–0.977, TLI range 0.904–0.974, RMSEA range 0.06–0.096). The six unidimensional scales were named: relationships with family and friends, social interactions, social activities, work and employment, romantic relationships, and sexual relationships. The marginal reliability of the full item bank and CATs ranged from 0.84 to 0.93, with ceiling effects less than 15% for all scales.

Conclusions

The LIBRE Profile is a promising new measure of social participation following a burn injury that enables burn survivors and their care providers to measure social participation.

Keywords: Item response theory, Computerized adaptive test, Burns, Social reintegration

Introduction

For patients with burn injuries, social participation is a complex, unexplored process requiring a deep understanding of the needs of this population [1]. Identifying the social needs of burn survivors can inform the design of future therapeutic interventions for optimal recovery beyond a patient’s physical needs. However, the impact burns have on relationships and societal roles has received little attention in burn survivors’ recovery.

To measure social participation after a burn injury, a conceptual framework is useful to define the domains of burn survivors’ social life that are most affected by their injury. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a conceptual model for health that incorporates biological, personal, and social aspects of a person’s life and has been widely used in the rehabilitation field. The ICF defines “participation” as engagement in a life situation. Using this conceptualization, we can examine the areas of social participation where burn survivors experience the most difficulty.

Burn survivors often experience burn-related sequelae that cause significant physical, psychological, and environmental challenges that impact their social participation [2, 3]. Physical challenges include contractures, joint deformities, neurologic and musculoskeletal problems, scarring, pain, itch, temperature intolerance, and fatigue [4]. Nearly 50% of burn survivors experience psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress [5]. These factors frequently impact the social, functional, and employment outcomes in burn survivors [6–9]. A recent literature review found 28% of burn survivors never return to any form of employment. Another study found only 37% of burn survivors had returned to the same job, without accommodations, 24 months after injury [9, 10].

Previous research has identified social interaction as one of the most common problems for individuals with burns, especially those with burns to the facial area. Scars and amputations can alter a person’s appearance and attract negative reactions from the general public. Meeting new people, developing close relationships, and securing a job can be more difficult when first impressions are negative [7, 11, 12]. Other social barriers include the ability to deal with individual’s perceptions and one’s own behavior in social situations, triggering episodes of social inhibition and decrements in social skills. Physical symptoms from a burn can also limit a person’s social activities, leading to increased isolation and frustration [11]. Identifying these areas provides opportunities for targeting and addressing them to improve burn survivors’ social participation problems.

In terms of sexual functioning, psychological dysfunction and decreased self-esteem are tightly linked to body image and disfigurement among those with burns [13]. Bianchi and coworkers found significant relationships between severity of burn injury and sexual-esteem, sexual-depression, and sexual-preoccupation in burn-injured men, ages 19–39 years [14]. Even though sexual function is highly relevant in terms of long-term quality of life, it is not often a priority for therapeutic interventions after a burn.

The increasing number of burn injury survivors requires adequate treatment to improve social participation [15]. However, measures of social participation following burn injuries are severely lacking. While generic tools are available to measure aspects related to participation, they lack the nuanced factors that are directly tied to the experience of the burn survivor. Prior disease specific assessments include the Young Adult Burn Outcomes Questionnaire and the Burn Outcomes Questionnaire [16, 17]. These assessments are limited in their breadth and depth of measurement of social participation and focus more on quality of life as a whole. Patient-reported outcomes such as the SF-36 and the suite of PROMIS measures are general and do not focus sufficiently on the social considerations of burn survivors’ social participation [18–22].

The objective of this work is to describe the development of a new measure called the “Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) Profile.” This paper reports on the initial psychometric evaluation of a new measure that can be administered via a computerized adaptive test (CAT). The CAT will administer brief but precise computer-generated assessments to measure the social participation of burn survivors. This measure provides caregivers, patients, and families with a means of profiling the social participation of burn survivors.

Methods

Item development

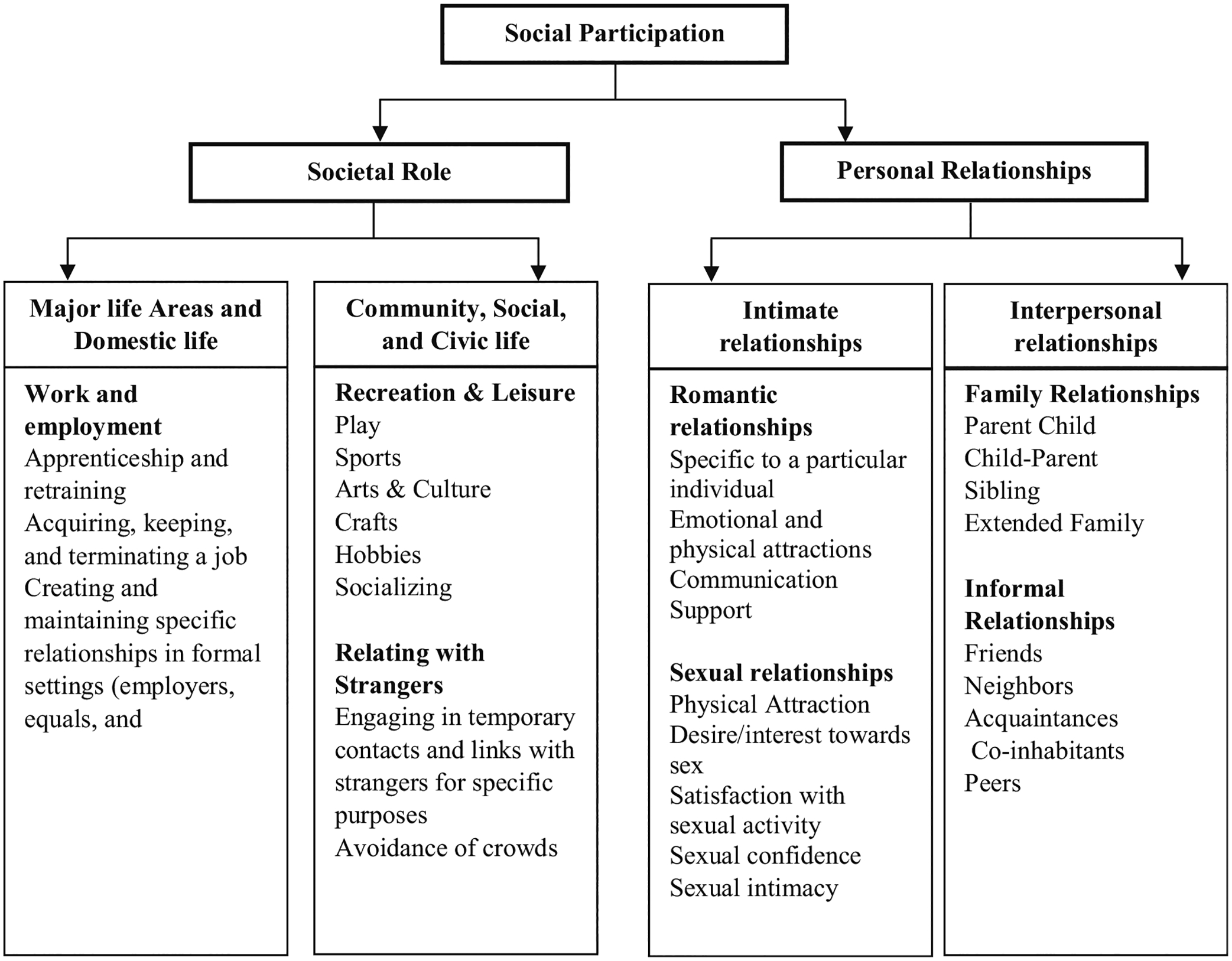

The WHO ICF is the conceptual model that guided the initial qualitative work [23]. We also performed a comprehensive literature review, and consulted with six clinicians who work with burn survivors and survivors themselves about the social impact of burns. The ICF was used to generate topic areas and develop the interview guide that was used for focus groups. Two focus groups were conducted with 23 burn survivors. The focus groups participants contained 11 women and 12 men, ages 20–66 years, 6 months to 35 years since burn injury, and total body surface area (TBSA) range from 18 to 94%. We conducted two additional focus groups with 27 clinicians (12 physicians, 15 other professions) with a range of 1.5–40 years of experience working with burn survivors. Data from the focus groups were used to develop a content framework for the underlying concept of social participation, and to develop items that captured the identified content areas, using grounded theory [24, 25]. The primary construct identified was social participation with two major domains pertinent to burn patients—Societal Role and Personal Relationships (Fig. 4 in Appendix).

Following the development of the initial instrument, we performed cognitive interviews with 23 burn survivors to assess clarity and interpretation of each item and response options. This process led to 192 items representing seven hypothesized subdomains: work, recreation and leisure, relating to strangers, romantic relationships, sexual relationships, family relationships, and informal relationships. Items were both “positively” and “negatively” phrased, and represented a range of ‘difficulty’ along each social impact dimension. The item pool contained questions and statements with three different response categories: “Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree, Not Applicable”; “Never, Almost Never, Sometimes, Often, Always, Not Applicable”; and “Not at All, A Little Bit, Somewhat, Quite a Bit, Very Much, Not Applicable.” Intensity and frequency scaling was used based upon feedback in the cognitive interviews. For example, there was some content burn survivors said was difficult to quantify, so we rephrased them as agreement questions, and other content was more appropriate as a frequency question. In another case, people said that “Because of my burns, I feel uncomfortable in social situations,” is a universal burn survivor experience, but how often it happens is different, and so it is a frequency item [24, 25].

Sampling methods and data collection

192 items were administered to a convenience sample of 601 burn survivors who satisfied the following inclusion criteria:(1) age 18 or older, (2) having survived a burn that was at least 5% total body surface area burned (TBSA), and/or burns to one of four critical areas (face, hands, feet, and genitals), (3) living in the United States or Canada, and (4) had the ability to read and understand English. Individuals who had participated in the focus groups or cognitive interviews were ineligible. The main sources of recruitment were the Phoenix Society (a support network for burn survivors), peer support networks, social media, and mailings. Interested persons were screened for eligibility by phone.

In addition to the 192 items, we collected the following demographic information: age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education level, as well as the time since burn injury, total body surface area burned (TBSA), and if the burn injury was work related. To ensure that burn survivors received questions that were appropriate to their life situation, we asked three filter questions: ‘Are you currently working for pay’? ‘Are you currently in a romantic relationship’? And ‘Are you currently sexually active’? Those who answered ‘no’ to these questions were still eligible but did not receive the items specific to that content area. Eligible participants were given the choice to complete the survey over the internet or by phone with a trained interviewer.

The study was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board (Protocol H-32928) and all subjects provided informed consent (oral for phone participants, written for self-administered participants) prior to participation in any study activities.

Data analysis

Data preparation

Items were removed with response percentage >90% in one of the item categories; and for items with a low frequency category (sample size <10) merged those with the adjacent category. The “Not Applicable” option was treated as missing in the analysis.

Unidimensionality

We conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) by extracting 1 to 10 factors based on full information maximum likelihood estimation method (FIML), followed by Oblique Crawford-Ferguson (CF)—Quartimax Rotation. We compared factor loading patterns, and examined the ratio between the first and second eigenvalues, the percent of variance explained by the first factor, and local dependence between item pairs. We decided on the number of factors by examining these results and similarities between the content in each factor and our elaborated conceptual model. Based on the exploratory factor structure, we conducted a confirmatory factor model (CFA) to examine the magnitude of the item factor loadings (>0.4) and values in the factor correlation matrix using FIML (full information maximum likelihood method). We determined acceptable model fit as Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤0.1, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥0.9 [26–30].

Item fit and item hierarchy

We calibrated the items that emerged from the CFA using the Graded Response Item—Response Theory (IRT) model. We examined the item fit by examining the difference in observed and expected number of subjects in each category at the summed score level using Pearson’s Chi-Square (s-2 statistics) test. Misfit items were identified using the item discrimination parameter to evaluate items for inclusion, and we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment to control for Type 1 error.

Differential item functioning

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) occurs when individuals at the same estimated ability or functional level in a particular content sub-domain respond differently to the same item based on some other variable. We examined the DIF for age (<45 vs. ≥45), gender, race (white vs. non-white), and time since burn (<7 vs ≥7 years) by the 2-step IRT-based DIF method [31–33]. The cut points were decided based upon our sample’s mean and median to have sufficient sample size to conduct the analysis. In the first step, the mean and standard deviation of the reference group was fixed, while it was estimated for the focal group using a two-group IRT model with all item parameters set equally across both. We then fit another two-group IRT model with the mean and SD of the focal sample fixed at the previous estimates, and used the Wald X2 test to determine differences in item parameters. Items that show a difference are DIF Candidate items. In the second step, the item parameters identified in the first step are set equal across reference and focal groups for non-DIF candidate items, and the mean and standard deviation of the focal group are free to estimate. Wald X2 was used to examine the DIF in the rest of the items, again using a two-group IRT model. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used to adjust the p value for the Wald-X2 tests. For the DIF item(s), we calculated the wABC (the weighted absolute difference between item characteristic curves) by integrating the absolute difference between the expected score functions of reference and focal groups over the latent distribution. For 5-category items those with wABC >0.3 and for 4-category items with wABC >0.24 were classified as DIF.

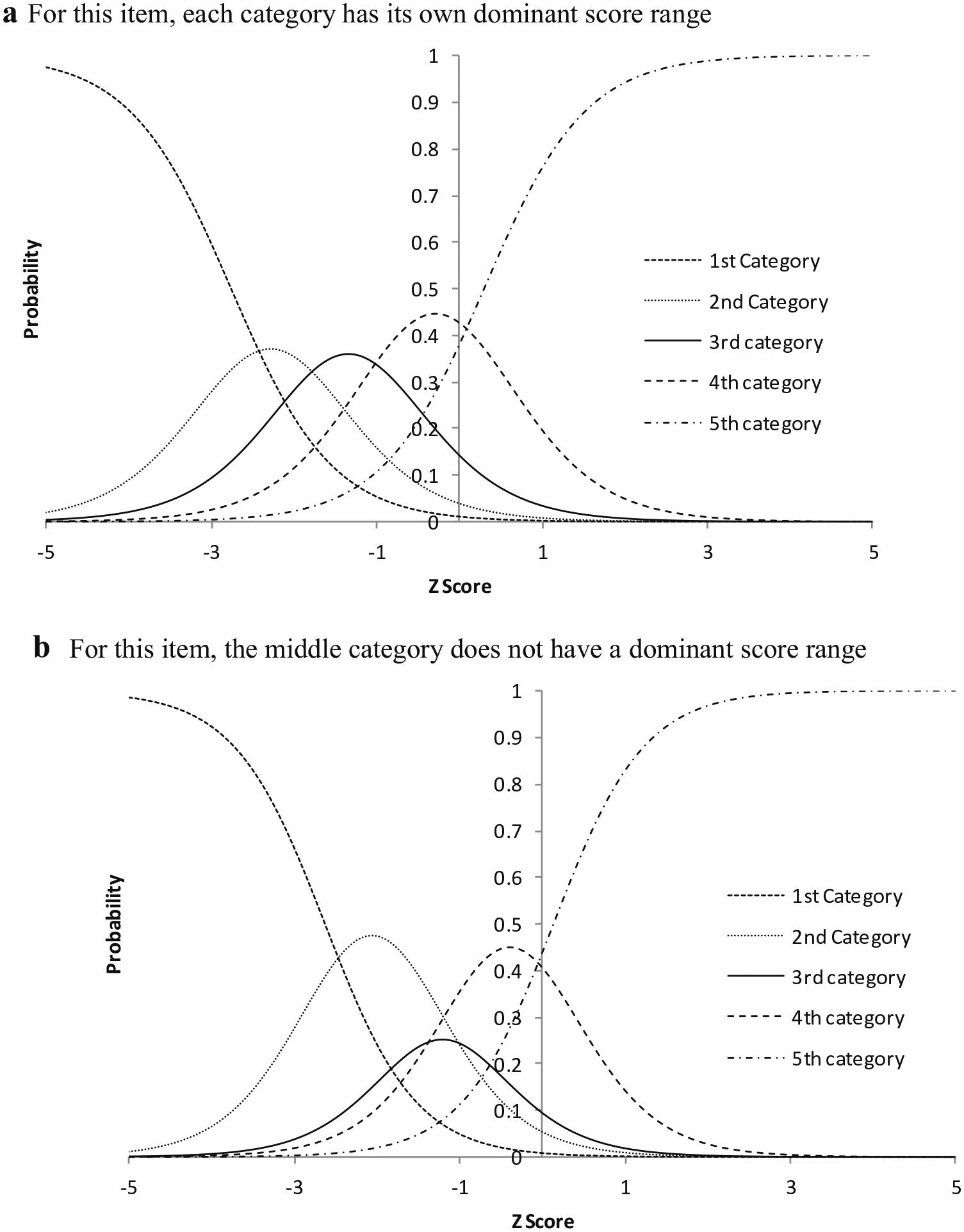

Response category functioning

We examined the functioning of the different response categories also using Graded Response Model methods. We examined whether each category had a certain score range in which the probability of endorsing this category is higher than all the other categories. For every item, each response option should have a range of scores for which it has the highest probability of being selected—referred to as a dominant score range. If a response category has no dominant score range (the probability of endorsing that choice is never higher than all the other categories), it could indicate that the response categories are not functionally optimally. For examples of items with both good and poor response category functioning, see Fig. 5 in Appendix.

To examine the monotonicity, we calculated the mean score for each category and examined whether the mean scores were increasing as the category score increased (e.g., the mean score in the first category should be less than that in the second category). Taking into account the random error, we examined the mean difference by calculating the ratio between the mean difference and combined standard errors, and compared it with a 1.96 threshold. If the mean difference is significant, it would indicate the violation of monotonicity.

Psychometric evaluation

The LIBRE Profile standard scores were transformed to a T-score distribution where the mean = 50, SD = 10; lower scores correspond to poorer performance on the scale.

To examine the psychometric properties of the LIBRE Profile, a plot of the test information function of each scale was generated and superimposed on the histogram of the score distribution of the sample. In scales based upon item response theory, the reliability is different for each score along the continuum of the construct that is being measured. The percentage of subjects whose score was located in the reliability ≥0.9 score range was calculated (in standard normal score distribution, the reliability ≥0.9 equals to test information value ≥10 or standard error ≤3.16 in the T scale). The marginal reliability of the entire item bank (or a set of administered items) was then calculated by (score variance—average of the squared standard errors)/score variance.

Computer adaptive test (CAT)

Computerized Adaptive Tests (CATs) allow for brief but accurate patient-reported outcome assessments [34–38]. Unlike classical test theory methods, IRT models provide an approach for estimating how precise test items are in assessing outcome levels at any point along a latent construct such as the social impact of burn injuries. CAT administration uses an algorithm applied to precisely calibrated questionnaire items. The CAT first selects a highly discriminating item from an item pool. Subsequently, the algorithm selects additional items that have the highest possible information given the person’s previous responses. This adaptive item presentation continues until a predefined ‘measurement precision’ is attained or a specified number of items have been presented and lessens respondent burden.

The calibration sample was used to conduct real data CAT simulations where the CAT program selected the first item with the highest information function value around the mean score of a specific scale. Weighted likelihood estimation was used to estimate the score and standard error. The program selected the subsequent items with the optimal information for that score and re-calculated the score based on the subsequent response. The stopping rule used in the algorithm required a minimum of five items, maximum of 10, and reliability ≥0.90.

We compared the simulated CAT score and the full item bank score based upon the score range, ceiling and floor effects, and marginal reliability. We also calculated the ratio between the average number of administered CAT items and the number of items in the full item bank, and estimated the time saved in the CAT simulations compared to the full item based, assuming a completion rate of three items per minute [39].

The factor analyses were conducted in Mplus, the IRT analyses in IRTPRO, and CAT simulations in SAS.

Results

The sample included 601 burn survivors (Table 1); 54.7% were female and the mean age was 44.6 (SD 15.98) years. The mean TBSA was 40.5% and the average time since burn injury was 15.4 years.

Table 1.

Sample demographics

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age mean ± SD | 44.55 (15.98) | |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 329 | 54.74 |

| Men | 271 | 45.09 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.17 |

| Race | ||

| White | 481 | 80.03 |

| Black/African American | 57 | 9.48 |

| Other | 54 | 8.99 |

| Missing | 9 | 1.50 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| Yes | 41 | 6.82 |

| No | 552 | 91.85 |

| Missing | 8 | 1.33 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 4 | 0.67 |

| High School/GED | 244 | 40.60 |

| Greater than high school | 349 | 58.07 |

| Missing | 4 | 0.67 |

| Time since burn injury mean ± SD | 15.36 (16.18) | |

| <6 months | 40 | 6.7 |

| 6–12 months | 18 | 3.0 |

| >12 months | 538 | 89.5 |

| Missing | 5 | 0.8 |

| TBSA mean ± SD | 40.45 (23.65) | |

| <10% | 197 | 32.78 |

| 10–29% | 82 | 13.64 |

| 30–49% | 158 | 26.29 |

| ≥50% | 165 | 27.29 |

| Self-administration (internet) | 503 | 83.69 |

| Interview administration (telephone) | 98 | 16.31 |

There were no items with a response category percentage >90%. In 12 items where the item categories had <10 subjects, we merged the first, second, and third response categories; in 56 items, we merged the first and second categories. We recoded the category scores with a higher score representing greater ability on a scale. The study design required that participants responded to all questions; therefore there were no non-responses for any of items, as long as a person was administered that domain. The average percent of Not Applicable responses per domain ranged from 2.04 to 3.64%. These Not Applicable responses were treated as missing in the analysis.

Unidimensionality

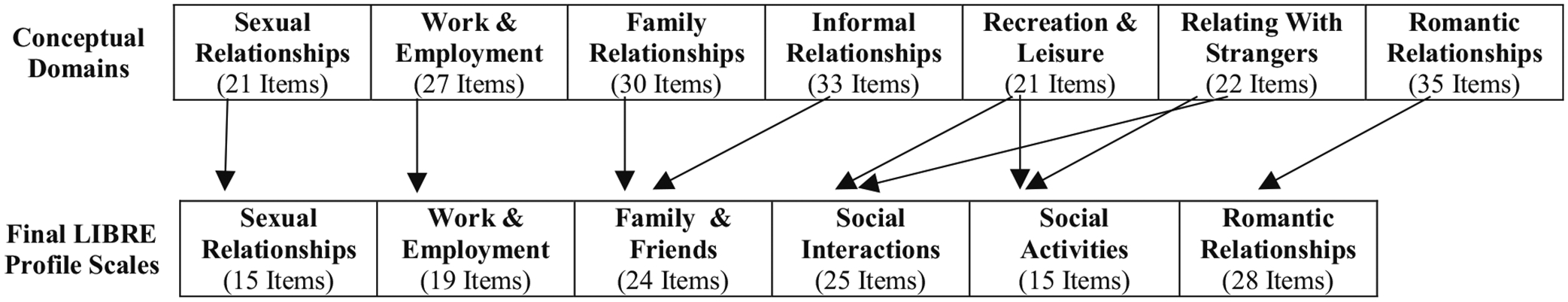

In the EFA analysis, the result was a six factor solution, which we titled: Family & Friends, Social Interactions, Social Activities, Work & Employment, Romanic Relationships, and Sexual Relationships (Fig. 1). In this analysis, 16 items failed to load onto a factor in a conceptually interpretable way, and were removed from additional analyses. To account for the local dependence in each scale, we removed 46 items that had Local Dependence (LD) indicated by a X2 Statistic value >10 with other items [40] (Table 2). Results from the CFA indicated acceptable fit statistics across all subdomains meeting the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤0.1, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥0.9 criteria (Table 2). These results show acceptable goodness of fit—that is, the sample matched the factor structure well, and each of six factors could be scaled as separate unidimensional constructs.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized conceptual domains and final scales of the LIBRE Profile

Table 2.

Internal consistency and CFA results for each Domain

| Family and friends | Social interactions | Social activities | Work and employment | Romantic relationships | Sexual relationships | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio between the first and second eigenvalues | 6.44 | 14.72 | 9.53 | 13.88 | 9.87 | 7.23 |

| % of variance explained by the first factor | 48.19% | 64.34% | 60.71% | 65.71% | 55.59% | 55.59% |

| CFI | 0.913 | 0.970 | 0.962 | 0.977 | 0.962 | 0.954 |

| TLI | 0.904 | 0.967 | 0.956 | 0.974 | 0.959 | 0.946 |

| RMESA | 0.090 | 0.086 | 0.093 | 0.073 | 0.06 | 0.096 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.91 |

Unidimensionality: the ratio between the first and second eigenvalue (>3), % of variance explained by the first factor (>40%). Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index, (TLI). We determined acceptable model fit as RMSEA ≤0.1, CFI and TLI ≥0.9

Item fit

In the IRT analyses, there were two misfitting items, (“I feel comfortable asking for changes at my job that will help me do my work,” and “I enter into sexual relationships too quickly”) and both of them were removed from the item banks. All the other items achieved an acceptable fit.

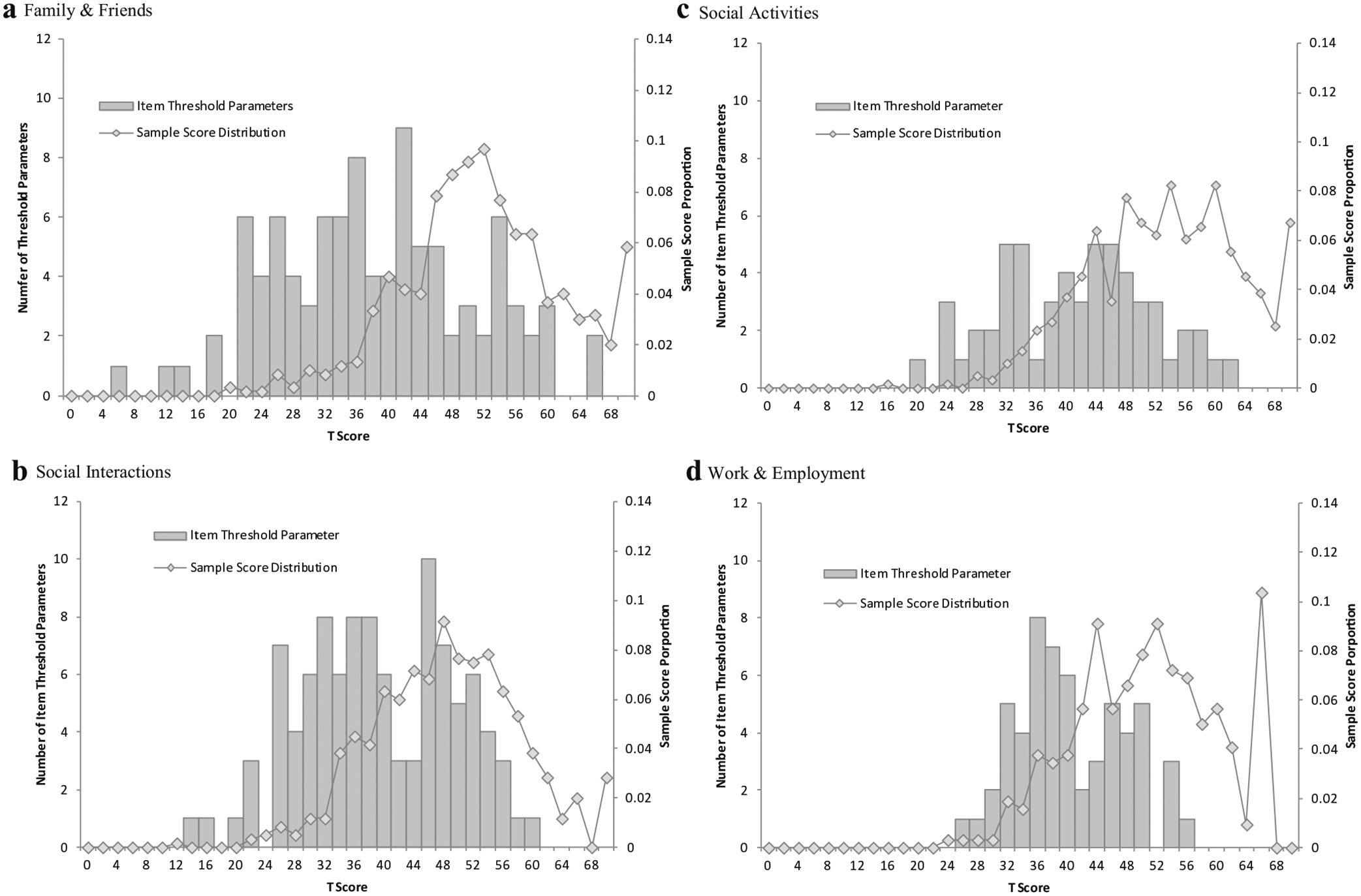

Item hierarchy

Figure 2a–f presents the plots of the distributions of the item threshold parameter and sample scores for each scale. Overall, there is a low frequency of items parameters at the higher end (which related to higher scores). There were also some item threshold density gaps in the score range 40–44 in the Romantic Relationships scale. Finally, there was poorer item coverage in the relatively smaller item banks i.e., Sexual Relationships and Social Activity.

Fig. 2.

a–f Distributions of the item threshold parameter and sample scores

Differential item functioning

Two items (“I am satisfied with my ability to take care of family members who need me” and “My burns limit the time my family has for themselves”) showed DIF by ‘time since the burn injury’ and two items (“I dress to avoid stares” and “My partner does not want sex when I do”) showed gender DIF. Those items were retained in the item bank, but were given different item parameter values for different subgroups on each variable.

Response category functioning

We identified 42 items that showed a response category that was not dominant for any range of scores. (Table 4 in Appendix) The reason for non-dominance in the “Neither agree nor disagree” category, may be because the item content is clear and therefore few participants selected the neutral option, or that the participants completing the survey via the internet (83.69%) were more likely to choose more extreme responses when dealing with a personal subject matter. These items were retained in the item bank for three reasons: First, we had initially collapsed several of the response categories at the beginning of the analysis. Second, all of the items showed acceptable fit. Finally, the poorer performing response categories were at lower score ranges, and we did not want to decrease the ability of the measure to detect the respondents at the lower end of the scale—the population which would be in most need of further clinical support or interventions.

The results from examining monotonicity are available in (Table 5 in Appendix). Most of the mean score reversing happened in lower score categories. Those categories had a smaller sample size, which may have contributed to the mean score reversal. However, the statistical tests supported the interpretation that there is no violation of monotonicity. In further work, one might expand the sample to individuals with hypothesized lower scores (for example those with a recent burn), to have sufficient sample size at the lower end of the scales.

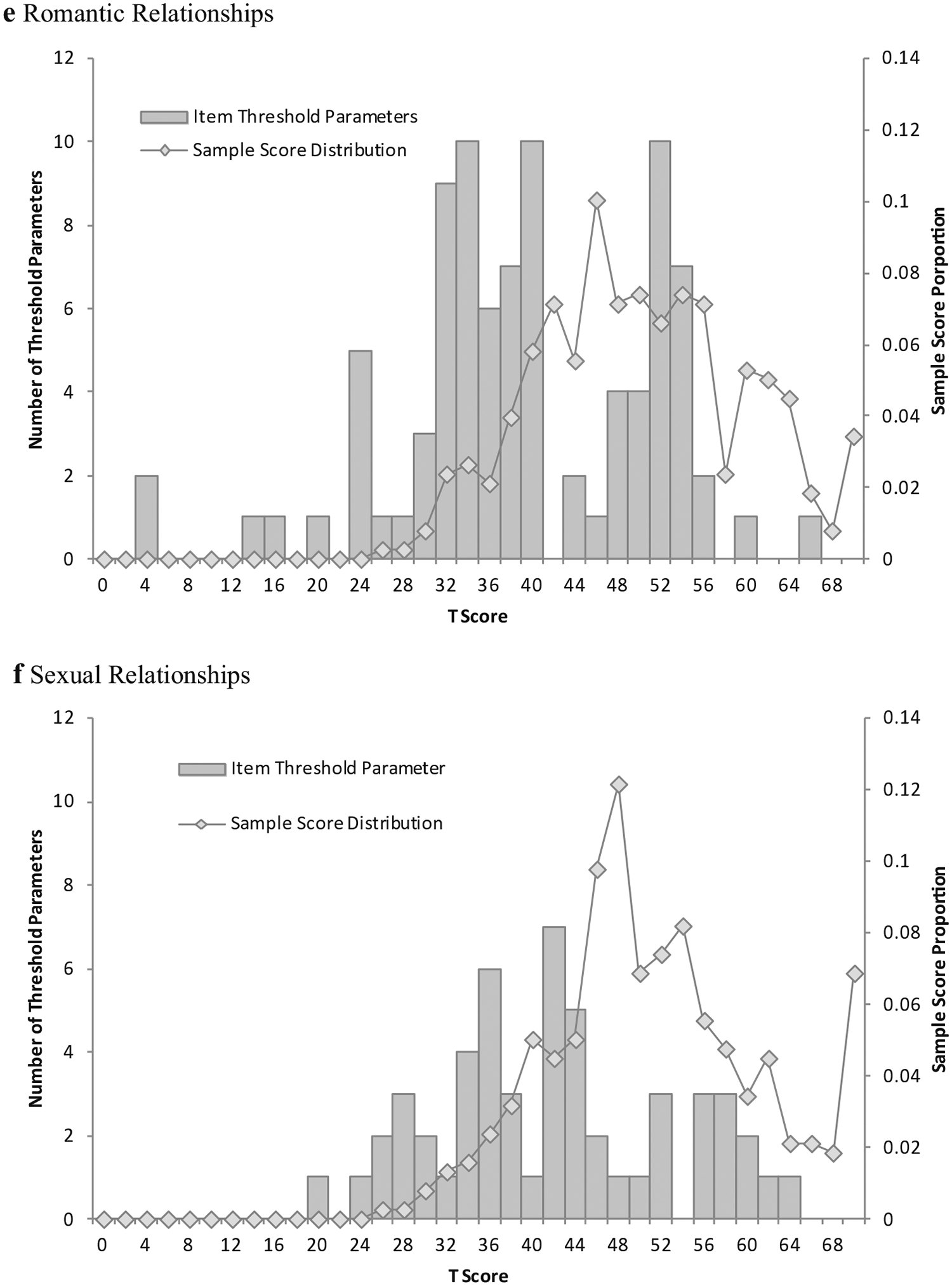

Psychometric evaluation

Table 3 displays results from the IRT analysis comparing the full item bank and CAT simulations. The marginal reliability of the full item bank and CAT ranged from 0.84 to 0.93. Ceiling effects were less than 15% for all scales. The percentages of subjects with score reliability >0.9 in each scale ranged from 72 to 91%. The ratio between the average number of administered CAT items and the number of items in each full item bank ranged from 0.22 to0.47, and the average estimated time for CAT simulations was 1.94–2.63 min. This indicates that the CAT could save about 3–7.25 min per scale with administering the CAT compared to the full item bank.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for simulated CATs and full item bank

| Domain | Mode | N a | Marginal reliability | % Ceiling | % Floor | % Sample score reliability >0.9 | Mean (SD) items in simulated CAT | Ratio of average CAT items and full item bank | Mean (SD) of estimated time in minutes using simulated CATb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family and friends | Full item bank | 598 | 0.91 | 1.67% | 0 | 83.28% | 7.89 (1.99) | 0.33 | 2.63 (0.66) |

| 5–10 item CAT | 598 | 0.85 | 2.84% | 0 | |||||

| Social interactions | Full item bank | 600 | 0.93 | 3% | 0 | 91% | 5.81 (1.78) | 0.23 | 1.94 (0.59) |

| 5–10 item CAT | 600 | 0.89 | 4.33% | 0 | |||||

| Social activities | Full item bank | 594 | 0.87 | 6.73% | 0 | 72.73% | 5.82 (1.78) | 0.39 | 1.94 (0.59) |

| 5–10 item CAT | 594 | 0.85 | 7.58% | 0 | |||||

| Work and employment | Full item bank | 318 | 0.88 | 11.64% | 0 | 78.3% | 6.62 (2.25) | 0.35 | 2.21 (0.75) |

| 5–10 item CAT | 318 | 0.84 | 13.52% | 0.31% | |||||

| Romantic relationships | Full item bank | 378 | 0.92 | 2.12% | 0 | 86.77% | 6.24 (2.07) | 0.22 | 2.08 (0.69) |

| 5–10 item CAT | 378 | 0.85 | 3.7% | 0 | |||||

| Sexual relationships | Full item bank | 378 | 0.89 | 3.44% | 0 | 79.89% | 6.98 (2.12) | 0.47 | 2.33 (0.71) |

| 5–10 item CAT | 378 | 0.86 | 5.03% | 0 |

The sample size in this table is based on the subjects took at least 10 items in each scale. The reason is: since the stopping rule of the CAT is minimal number of items = 5, maximum number of items = 10 and reliability ≥0.9; to have fair comparison among subjects in CAT scores and full item bank scores, we required that the subjects being compared should have taken at least 10 items within each scale

Assuming 1/3 min per item

Figure 3a–f illustrates the score distribution for each scale in the study sample, and the test information function, which estimates the information provided in the region where the majority of the sample scores are located. The shaded gray box indicates the ranges of scores for which the scale’s reliability is above the 0.9 threshold. These boxes correspond with 72–91% of the sample with reliability scores >0.9, as shown in Table 3. The figures illustrate that the score ranges where the sample fell outside of0.9 reliability were primarily focused on higher scores, revealing that burn survivors with lower scores (who would be the target of interventions and clinical work) achieved highly reliable scores. For individuals who were at an ability level of approximately one standard deviation above the mean, scores were somewhat less reliable.

Fig. 3.

a–f Score distribution and test information function

Discussion

The LIBRE Profile is a new patient-reported outcome measure that assesses social participation of burn survivors [24]. It has important implications for gauging the unique needs of this population. Results of this study indicate that six unidimensional domains of social participation were identified and items scale along each dimension from low to high performance: Relationships with Family and Friends, Social Interactions, Social Activities, Work and Employment, Romantic Relationships, and Sexual Relationships. The marginal reliability of the full item bank and CAT ranged from 0.84 to 0.93 revealing good reliability for a wide range of scores for each of the 6 scales. The percentage of score reliabilities greater than 0.90 ranged from 72 to 83%, also indicating the acceptable levels.

Of the final 126 items among the six scales of the LIBRE Profile (Table 6 in Appendix), only four items displayed DIF, suggesting that overall, the items function similarly across the different groups tested.

This work lays an important foundation for developing a set of CATs that give a framework for capturing the social participation of adult burn survivors in the community. The conceptual basis for the development of the item pool includes a rich set of items describing social participation than previously developed tools. Prior work focused on measures that are better suited to the physical, psychological, and role functioning with little attention to the social domain. Burn-specific assessments like the LIBRE profile provide more detail for social issues that are specific to burn survivors.

The Relationships with Family and Friends domain measure different aspects of those relationships. Items ask burn survivors how their burn may impact on family relationships and socializing with the family. Perceptions include how their appearance may affect the individuals’ ability to interact with family members. Included are both the comfort level and activities one participates in with family and friends. Davidson et al. [41] found that measures of social support from family, friends, and peers were significantly related to several outcomes, such as life satisfaction, self-esteem, and participation in social and recreational activities. The authors also report that family support is a positive factor in the recovery process no matter the level of severity of the burn injury. Park et al. [42] describes that lack of family support was significantly related to development of mental distress in those with burns. The authors also found that family support predicted a positive recovery. As a consequence, the evidence signals that family support gives burn survivors the strength to endure the challenges behind the rehabilitation process, with a particular emphasis in long-term social adjustments, as Ledoux et al. [43] found.

The Social Interaction scale measures the ability of burn survivors to interact with people and situations that are familiar. Previous research signals social interaction as a common problem for those with burns; the most commonly reported problems for burn survivors are difficulty and anxiety in social situations, which occurs more often in adults than children [12, 44]. The Social Activities scale involves burn survivors’ perceptions of accomplishing daily activities and their ability to participate with others in these activities. These activities range from involvement in organized social events in the community, sports events for example, to informal gatherings with friends and associates, or to parties with peers from work or other friends. Both Social Activities and Social Interactions include an item pool that is specific to those with a history of burn injuries.

The LIBRE Profile Work and Employment scale covers items such as relationship with coworkers, satisfaction with one’s work, and the relationship with one’s peers on the job [9, 24]. In addition, the scale includes content related to performance of work, work responsibilities, energy on the job, and work absences due to health problems related to the burn injury. This domain can be administered to burn survivors who are back to work in their previous occupation or a new occupation or place of work that assesses the self-perceived work experience [45].

Our analysis led to two separate scales for Romantic Relationships and Sexual Relationships, a distinction which is also supported by our conceptual framework and previous qualitative work. [13, 23, 24] Romantic Relationships measures communication, sharing of problems with a romantic partner, emotional closeness and comfort talking about problems, and enjoyment of the partner. The scale also identifies the conduct of social activities that can be both intimate and emotional. The Sexual Relationships scale is specific to sexual functioning and the physical acts of sex and how that might impact a relationship for the burn survivor. One of the most frequent concerns of long-term recovery for those with burns is sexual functioning and related satisfaction [13, 14]. Overall, individuals with disfigurements and skin alterations have greater difficulty in making contact with partners. Body image and self-esteem have been recognized as important factors in sexual life [7]. The distinctions made for the romantic and sexual CATs are unique rich batteries for monitoring the outcomes of recovery.

These LIBRE Profile scales are empirically reliable and calibrated for a burn-specific population. The LIBRE Profile extends the NIH PROMIS domains related to social health and social functioning that are generic and cover satisfaction with and participating in social roles and activities, companionship, and interpersonal attributes as well as the ability to participate and satisfaction with one’s involvement in social situations [46].

Following burn injuries, the areas that the LIBRE Profile focuses on might be impacted on by psychological symptomatology. For example, those with burn injuries during the recovery process might present with psychiatric problems such as anxiety, depression and/or PTSD [7]. Further, this may impact on social problems such as social isolation and the inability to cope with day to day issues. The LIBRE Profile can serve to identify the needs of burn survivors and provide a guide for future interventions. For example, clinicians or other providers can use scores to make recommendations and referrals if a patient’s score is below an expected score for someone with similar demographic and clinical characteristics.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the 601 subjects were obtained via convenience sampling. However, this sample was national in scope and provided a good deal of variability in the demographics and clinical characteristics contributing to the internal validity of the findings. Nevertheless, there were only fifty-eight participants who were less than one year post burn; future research should be conducted to further validate the LIBRE Profile’s use in this clinical population.

Second, while those with lower social integration achieved highly reliable scores, individuals who were at an ability level of approximately one standard deviation above the mean had scores that were somewhat less reliable, although they were still credible. Third, not surprisingly, there is some loss of reliability when comparing the full item bank with the 5–10 item CAT for each of the domains.

Future research can explore different subgroups of burned patients, such as those with specific socio-demographic characteristics and burns to critical areas with item content that may be more specific to targeted subgroups. Additionally, our study design allowed individuals to select their mode of administration: phone or self-administered over the internet. We examined differences in scores by mode. Subjects who selected the interview format were more likely to be older and less educated. There were no differences in scores between the two groups, except in social activities. It is possible that the interview group may have been less socially active or that social desirability effects were dwarfed by selection effects. Future work can focus on mode effects for the LIBRE Profile. Finally, we can examine how scores may change over time using a longitudinal cohort approach to study reproducibility and responsiveness to change. These studies could be used to establish typical recovery trajectories for a range of burn injury types and to better understand the social recovery process. Recovery curves would allow the LIBRE Profile to be used to follow individuals over time and intervene when difficulties occur. Since many of the items are not burn specific, it is possible that versions of this measure could be validated for use in other populations with social participation challenges, such as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and TBI.

Other health-related QOL constructs could be added to the LIBRE Profile in future studies. Such work involves understanding how other factors such as body image and self-esteem might be related to LIBRE Profile scores, a replenishment of the existing scales with new content, [47] or the development and addition of new scales.

Conclusions

The LIBRE Profile is a burn-specific patient-reported outcome measure that captures levels of social participation after a burn injury. The study framework is based upon the WHO ICF and focus groups/cognitive testing that added to the specificity of the rich item bank detailing the burn survivors’ social recovery process. Analyses yielded six distinct domains that corroborated the conceptual framework. The use of a CAT with 5–10 items administered per domain provides a feasible assessment for administration in a clinical setting or in the subject’s home using web-based approaches. Information from the LIBRE Profile can be of use to the clinician and burn survivor in assessing the social impact of burn injuries.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Award Number 90DP0055.

Appendix

See Figs. 4, 5 and Tables 4, 5, 6.

Fig. 4.

Conceptual model for social participation for burn survivors

Fig. 5.

Examples of all dominant (a) and selected non-dominant (b) response category functioning

Table 4.

Items with a response category that was not dominant for any range of scores

| Scale | Total items in bank | Items without dominant score range for certain category(ies)* | Non-dominant response category(ies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual relationships | 15 | 4 | “Neither agree nor disagree” |

| Family and friends | 24 | 12 | 8 “Neither agree nor disagree” 4 adjacent to “Neither agree nor disagree” |

| Social interactions | 25 | 4 | 2 “Neither agree nor disagree” 2 adjacent to “Neither agree nor disagree” |

| Social activities | 15 | 2 | “Neither agree nor disagree” |

| Work and employment | 19 | 10 | “Neither agree nor disagree” |

| Romantic relationships | 28 | 10 | 8 “Neither agree nor disagree” 2 adjacent to “Neither agree nor disagree” |

Table 5.

Item mean score order and monotonicity

| Factor name | # of items | # of items with mean score reversed | # of items violated monotonicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family friends | 24 | 5 | 0 |

| Social interactions | 25 | 4 | 0 |

| Social activity | 15 | 1 | 0 |

| Work employment | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Romantic relationships | 28 | 4 | 0 |

| Sexual relationships | 15 | 2 | 0 |

Table 6.

LIBRE profile items by scale

Family and friends

|

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Brigham PA, & McLoughlin E (1996). Burn incidence and medical care use in the united states: Estimates, trends, and data sources. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 17(2), 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esselman PC (2011). Community integration outcome after burn injury. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 22(2), 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider JC, Bassi S, & Ryan CM (2009). Barriers impacting employment after burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 30(2), 294–300. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318198a2c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider JC, & Qu HD (2011). Neurologic and musculoskeletal complications of burn injuries. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 22(2), 261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madianos MG, Papaghelis M, Ioannovich J, & Dafni R (2001). Psychiatric disorders in burn patients: A follow-up study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 70(1), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moi AL, Wentzel-Larsen T, Salemark L, Wahl AK, & Hanestad BR (2006). Impaired generic health status but perception of good quality of life in survivors of burn injury. Journal of Trauma, 61(4), 961–968. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195988.57939.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Loey NE, & Van Son MJ (2003). Psychopathology and psychological problems in patients with burn scars. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 4(4), 245–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helm PA, & Walker SC (1992). Return to work after burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 13(1), 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason ST, Esselman P, Fraser R, Schomer K, Truitt A, & Johnson K (2012). Return to work after burn injury: A systematic review. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 33(1), 101–109. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182374439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brych S, Engrav L, Rivara FP, et al. (2001). Time off work and return to work rates after burns: Systematic review of the literature and a large two-center series. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 22(6), 401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cukor J, Wyka K, Leahy N, Yurt R, & Difede J (2015). The treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and related psychosocial consequences of burn injury: A pilot study. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 36(1), 184–192. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson E, Ramsey N, & Partridge J (1996). An evaluation of the impact of social interaction skills training for facially disfigured people. British Journal of Plastic Surgery, 49(5), 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tudahl LA, Blades BC, & Munster AM (1987). Sexual satisfaction in burn patients. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation, 8(4), 292–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terri Lynn G, & Bianchi FNP (1997). Aspects of sexuality after burn injury: Outcomes in men. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 18(2), 182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esselman PC (2007). Burn rehabilitation: An overview. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(12), S3–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan CM, Schneider JC, Kazis LE, et al. (2013). Benchmarks for multidimensional recovery after burn injury in young adults: The development, validation, and testing of the american burn association/shriners hospitals for children young adult burn outcome questionnaire. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 34(3), e121–e142. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31827e7ecf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazis LE, Lee AF, Rose M, et al. (2016). Recovery curves for pediatric burn survivors: Advances in patient-oriented outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, & Gandek B (2000). SF-36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln: Quality Metric Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook K, Kallen M, Cella D, Crane P, Eldadah B, Hays R (2014) The patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) perspective on: universally-relevant vs.disease-attributed scales.

- 20.Hahn EA, DeVellis RF, Bode RK, et al. (2010). Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Item bank development and testing. Quality of Life Research, 19(7), 1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn EA, Beaumont JL, Pilkonis PA, et al. (2016). The PROMIS satisfaction with social participation measures demonstrated responsiveness in diverse clinical populations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 73, 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. (2016). PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 73, 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO I, World Health Organization. (2007). International classification of functioning. Disability and Health (ICF), endorsed by all. 191. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marino M, Soley-Bori M, Jette AM, et al. (2015). Development of a conceptual framework to measure the social impact of Burns. Journal of Burn Care and Research, 37(6), e569–e578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marino M, Soley-Bori M, Jette AM, et al. (2016). Measuring the social impact of burns on survivors: Item development according to a validated conceptual framework. Journal of Burn Care and Research, 38(1), e377–e383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steiger JH (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoyle RH (1995). Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacCallum RC, Browne MW, & Sugawara HM (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, & Paxton P (2008). An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(4), 462–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer MM (2008). A reexamination of Lord’s Wald test for differential item functioning using item response theory and modern error estimation.

- 32.Woods CM, Cai L, & Wang M (2013). The langer-improved wald test for DIF testing with multiple groups evaluation and comparison to two-group IRT. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(3), 532–547. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelen MO, Stucky BD, & Chandra A (2013). Quantifying ‘problematic’DIF within an IRT framework: Application to a cancer stigma index. Quality of Life Research. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hays RD, Morales LS, & Reise SP (2000). Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Medical Care, 38(9 Suppl II), 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Revicki D, & Cella D (1997). Health status assessment for the twenty-first century: Item response theory, item banking and computer adaptive testing. Quality of Life Research, 6(6), 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unick GJ, Shumway M, & Hargreaves W (2008). Are we ready for computerized adaptive testing? Psychiatric Services, 59(4), 369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbons RD, Weiss DJ, Kupfer DJ, et al. (2008). Using computerized adaptive testing to reduce the burden of mental health assessment. Psychiatric Services, 59(4), 361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norris JM (2001). Computer-adaptive testing: A primer. Language Learning & Technology, 5(2), 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hays RD, Bode R, Rothrock N, Riley W, Cella D, & Gershon R (2010). The impact of next and back buttons on time to complete and measurement reliability in computer-based surveys. Quality of Life Research, 19(8), 1181–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai L, Du Toit S, & Thissen D (2011). IRTPRO: Flexible, multidimensional, multiple categorical IRT modeling [computer software]. Chicago: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson TN, Bowden ML, Tholen D, James MH, & Feller I (1981). Social support and post-burn adjustment. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 62(6), 274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S, Choi K, Jang Y, & Oh S (2008). The risk factors of psychosocial problems for burn patients. Burns, 34(1), 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeDoux J, Meyer W, Blakeney P, & Herndon D (1998). Relationship between parental emotional states, family environment and the behavioural adjustment of pediatric burn survivors. Burns, 24(5), 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corry N, Pruzinsky T, & Rumsey N (2009). Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment to burn injury: Social functioning, body image, and health policy perspectives. International Review of Psychiatry, 21(6), 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esselman PC, Askay SW, Carrougher GJ, et al. (2007). Barriers to return to work after burn injuries. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(12), S50–S56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. (2010). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haley SM, Ni P, Jette AM, et al. (2009). Replenishing a computerized adaptive test of patient-reported daily activity functioning. Quality of Life Research, 18(4), 461–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]