Abstract

Purpose:

To assess the role of refractive error (RE) and anterior chamber depth (ACD) as risk factors in primary angle closure disease (PACD).

Methods:

Chinese American Eye Study (CHES) participants received complete eye exams including refraction, gonioscopy, A-scan biometry, and anterior segment OCT imaging. PACD included primary angle closure suspect (PACS; ≥3 quadrants of angle closure on gonioscopy) and primary angle closure/primary angle closure glaucoma (PAC/G; peripheral anterior synechiae or IOP>21mmHg). Logistic regression models were developed to assess associations between PACD and RE and/or ACD adjusted for sex and age. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) curves were plotted to assess continuous relationships between variables.

Results:

3,970 eyes (3,403 open angle; 567 PACD) were included. Risk of PACD increased with greater hyperopia (OR=1.41 per diopter [D]; p<0.001) and shallower ACD (OR=1.75 per 0.1mm; p<0.001). Hyperopia (≥+0.5D; OR=5.03) and emmetropia (−0.5D to +0.5D; OR=2.78) conferred significantly higher risk of PACD compared to myopia (≤0.5D). ACD (standardized regression coefficient [SRC]=−0.54) was a 2.5-fold stronger predictor of PACD risk compared to RE (SRC=0.22) when both variables were included in one multivariable model. The sensitivity and specificity of a 2.6mm ACD cutoff for PACD were 77.5% and 83.2%, of a +2.0D RE cutoff were 22.3% and 89.1%.

Conclusion:

Risk of PACD rises rapidly with greater hyperopia while remaining relatively low for all degrees of myopia. Although RE is a weaker predictor of PACD than ACD, it remains a useful metric to identify patients who would benefit from gonioscopy in the absence of biometric data.

Keywords: Angle closure, refractive error, ocular biometrics, primary angle closure glaucoma

Precis

Risk of primary angle closure disease rises rapidly with greater hyperopia while remaining relatively low for all degrees of myopia. Refractive error is useful for angle closure risk-stratification in the absence of biometric data.

Introduction

Primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG) is a common cause of ocular morbidity and blindness worldwide.1 Angle closure is characterized by apposition between the trabecular meshwork and peripheral iris, which leads to obstruction of aqueous humor outflow, elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP), and increased risk of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Angle closure plays a role in around one quarter of all glaucoma cases, and PACG contributes to around half of glaucoma-related blindness worldwide and 91% of bilateral glaucoma blindness in Asian regions.2-4 The prevalence of PACG is expected to rise rapidly over the next two decades due to aging of the world’s population.2 Therefore, appropriate awareness among eye care providers about the importance of evaluating the angle to detect patients with or at risk for PACG is crucial.

Gonioscopy is the current clinical standard for detecting angle closure and forms the basis of current definitions of primary angle closure disease (PACD), which encompasses the spectrum of angle closure severity with PACG as the most severe disease state.5 The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) recommends all patients undergoing evaluation for glaucoma receive gonioscopy.6 However, gonioscopy remains underperformed by eye care providers, thereby contributing to missed or delayed detection of angle closure.7-9 The decision by eye care providers to perform gonioscopy outside of glaucoma suspects is primarily based on risk factors for angle closure, including refractive error (RE) and ocular biometrics. Hyperopia has been a well-established risk factor for PACG since the early 1950s.10-12 More recently, ocular biometric parameters have been established as important risk factors for angle closure and PACG.13 Shallow anterior chamber depth (ACD), in particular, is strongly associated with hyperopia and increased risk of PACG.14,15

In this study, we perform a deeper investigation on the role of RE and ACD as risk factors in PACD among participants of the Chinese American Eye Study (CHES), a population-based epidemiological study based in Los Angeles, California.16 While previous studies have examined the risk conferred by broad categories of RE (hyperopia, emmetropia, and myopia) and the relationship between RE and anterior segment biometrics, the precise role of continuous measures of RE and ACD as risk factors in PACD is not well characterized. There is also little known about the relative contributions of RE and ACD as risk factors in PACD. Finally, it is unclear if the role of RE and ACD as risk factors differ based on severity of PACD. A deeper understanding of these topics could provide clarity for eye care providers and inform clinical decision-making about performing gonioscopy outside of glaucoma suspects.

Methods

Ethics committee approval was previously obtained from the University of Southern California Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All study procedures adhered to the recommendations of the declaration of Helsinki. All study participants provided informed consent at the time of enrollment.

Clinical Assessment

Study participants were identified from the Chinese American Eye Study (CHES), a population-based, cross-sectional study of 4,582 Chinese participants ages 50 years and older living in Monterey Park, California. CHES participants received complete eye exams by trained ophthalmologists (D.W., C.L.G.), including automated refraction (Humphrey Automatic Refractor, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) if uncorrected visual acuity was less than 20/20 in either eye, IOP measured by Goldman applanation tonometry (GAT), A-scan ultrasound biometry (4000B A-Scan/Pachymeter; DGH Technology, Inc), gonioscopy, and anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT) imaging (CASIA SS-1000, Tomey Corporation, Nagoya, Japan).16 Gonioscopy was performed by trained ophthalmologists masked to other exam findings using a Posner-type 4-mirror lens (Model ODPSG; Ocular Instruments, Inc, Bellevue, WA, USA) under dark ambient lighting (0.1 cd/m2). The angle in each quadrant was graded using the modified Shaffer system: grade 0, no structures visualized; grade 1, non-pigmented trabecular meshwork (TM) visible; grade 2, pigmented TM visible; grade 3, scleral spur visible; and grade 4, ciliary body visible. In addition, the angle was also assessed for peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS).

Angle closure was defined as an angle quadrant in which pigmented TM was not visible on static gonioscopy. Primary angle closure suspect (PACS) was defined as an eye with three or more quadrants of angle closure in the absence of PAS, IOP > 21 mmHg, and potential causes of secondary angle closure, such as inflammation or neovascularization.5 Primary angle closure with or without glaucoma (PAC/G) was defined as an eye fitting the definition of PACS with PAS in at least one quadrant or IOP > 21 mmHg. There was no distinction made between eyes with (PACG) and without (PAC) glaucomatous optic neuropathy in this study due to low statistical power associated with the number of PACG eyes (fewer than 15).

CHES participants who received complete eye exams were eligible for the current study. Participants with history of laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) or cataract surgery were excluded from the analysis due to their potential effects on refractive status and ACD. Participants without documented gonioscopy or with indeterminate PACD severity, including those missing intraocular pressure (IOP) or peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) data, were also excluded from the analysis.

Ocular biometry

AS-OCT imaging was performed by a single trained ophthalmologist in the seated position under dark ambient lighting (0.1 cd/m2) after gonioscopy and prior to pupillary dilation. AS-OCT data was imported into the Tomey SS OCT Viewer software (version 3.0, Tomey Corporation, Nagoya, Japan) and analyzed by one grader (A.A.P.) masked to the identities and examination results of the subjects who confirmed the segmentation and marked the scleral spurs in each image.17 Four images per eye spaced 45 degrees apart were analyzed to capture the majority of each angle’s anatomical variation.18,19 The first image analyzed was oriented along the horizontal (temporal-nasal) meridian. Eyes in which 3 or more of the 8 scleral spurs could not be identified were excluded from the analysis.

The following biometric parameters describing angle width were analyzed in each image: angle opening distance (AOD750) and trabecular iris space area (TISA750) measured at 750 μm from the scleral spur, anterior chamber width (ACW), iris area (IA), and lens vault (LV). These parameters have previously been defined.20 In brief, AOD750 is the distance of a line drawn from a point on the corneal endothelial surface 750 μm from the scleral spur to a point on the iris that is perpendicular to the iris surface. TISA750 is the area of a trapezoid bounded anteriorly by the AOD750, posteriorly by a line drawn from the scleral spur perpendicular to the plane of the inner scleral wall to the iris, superiorly by the inner corneoscleral wall, and inferiorly by the iris surface. ACW is the horizontal scleral spur-to-spur distance. Iris area is the cross-sectional area of the full length of the iris from scleral spur to pupil. Lens vault is the perpendicular distance from the anterior surface of the lens to a horizontal line connecting the scleral spurs. Measurements were averaged across the four images. Intra-observer repeatability of AS-OCT parameter measurements from the CASIA SS-1000 has been reported for the study grader (A.A.P.).21 The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) for parameters used in the current study indicated excellent measurement repeatability, ranging between 0.93 to 0.99.

Central corneal thickness (CCT), anterior chamber depth (ACD), lens thickness (LT), and axial length (AL), were measured by A-scan ultrasound biometry. Vitreous length (VL) was calculated by subtracting CCT, ACD, and LT from AL.

Statistical analysis

One eye per participant was selected for analysis. If both eyes had the same disease status (open angle, PACS, or PAC/G), then one was selected at random. If the eyes were asymmetric, the eye with the more severe disease status was selected. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression modeling was performed to assess the relationship between RE and/or ACD and risk of PACD. Three separate multivariable models were developed for RE, ACD, and RE and ACD, adjusting for sex and age. Variable inflation factors (VIF) < 3 were confirmed to rule out multicollinearity. Standardized regression coefficients (SRC) for RE and ACD were computed for the multivariable model to standardize units and allow for direct comparison of the log odds of covariates on a standardized scale. Pseudo R-squared and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) metrics were computed to assess model fit and classification performance. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) curves were fit to these predicted values to visualize the continuous relationship between RE or ACD and probability of PACD. Histograms were generated to visualize proportion of patients with PACD in 1-diopter steps of RE and 0.25 mm steps of ACD. Separate sex- and age-adjusted multivariable logistic regions models were developed to assess the association between risk of mild, severe, and all-stage PACD and categories of RE: myopia (≤ −0.5 D), emmetropia (−0.5 D to + 0.5 D), and hyperopia (≥ + 0.5 D). The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to compare biometric measurements across these three categories of refractive error. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

In total, 4,582 CHES participants were recruited. 111 participants (2.4%) who did not receive gonioscopy, 431 participants (9.4%) with prior history of LPI or surgery, and 70 participants (1.5%) with indeterminate disease status were excluded from the analysis. 3,970 eyes of 3,970 participants qualified for analysis. 3,403 eyes had open angles (85.7%), 451 (11.5%) had PACS, and 116 (2.9%) had PAC/G.

The mean age of study participants was 60.24 ± 7.9 years (Table 1). The PAC/G group was the oldest, followed by the PACS and normal groups. There were more females (63.3%) than males (36.7%) overall and in the PACS and PAC/G groups. There were significant differences (p < 0.001) in ACD, AL, LT, IOP, and mean Shaffer grade among the groups (Table 1). Hyperopia was the most common RE status overall (42.2%), followed by myopia (35.7%) and emmetropia (21.2%). The most common RE status was myopia in the normal group (39.5%) and hyperopia in the PACS (65.2%) and PAC/G (74.1%) groups. The proportions of myopes, emmetropes, and hyperopes were significantly different among the three disease categories (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and biometrics of the study population.

| Normal |

PACS |

PAC/G |

P-value |

Overall |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup size (N, %) | 3,403 (85.7%) | 451 | 116 | <0.001 | 3,970 |

| Mean age (mean, SD) | 59.64 (7.50) | 63.51 (9.18) | 64.92 (9.23) | <0.001 | 60.24 (7.90) |

| Sex (N, %) | |||||

| Female | 2091 (61.4%) | 350 (77.6%) | 71 (61.2%) | <0.001+ | 2512 (63.3%) |

| Male | 1312 (38.6%) | 101 (22.4%) | 45 (38.8%) | 1458 (36.7%) | |

| CCT (mean, SD, μm) | 560.18 (35.75) | 557.80 (33.36) | 561.16 (39.45) | 0.18 | 559.94 (35.60) |

| ACD (mean, SD) | 2.89 (0.31) | 2.42 (0.26) | 2.42 (0.28) | <0.001 | 2.82 (0.34) |

| LT (mean, SD) | 4.42 (0.37) | 4.67 (0.36) | 4.70 (0.36) | <0.001 | 4.46 (0.38) |

| VL (mean, SD) | 15.62 (1.34) | 14.65 (0.85) | 14.59 (0.89) | <0.001 | 15.48 (1.32) |

| AL (mean, SD) | 24.04 (1.38) | 22.86 (0.86) | 22.83 (0.90) | <0.001 | 23.88 (1.38) |

| IOP (mean, SD) | 15.15 (2.91) | 15.18 (2.47) | 18.72 (5.18) | <0.001 | 15.26 (3.01) |

| Shaffer grade (mean, SD) | 3.08 (0.58) | 0.94 (0.55) | 0.70 (0.57) | <0.05 | 2.77 (0.96) |

| RE (N, %) | |||||

| Hyperopia (≥+0.5D) | 1,295 (38.1%) | 294 (65.2%) | 86 (74.1%) | <0.001+ | 1,675 (42.2%) |

| Emmetropia (−0.5 to +0.5D) | 733 (21.5%) | 95 (21.1%) | 14 (12.1%) | 842 (21.2%) | |

| Myopia (≤−0.5D) | 1,344 (39.5%) | 60 (13.3%) | 15 (12.9%) | 1,419 (35.7%) |

ACD = anterior chamber depth; AL = axial length; CCT = central corneal thickness; IOP = intraocular pressure; LT = lens thickness; PAC/G = primary angle closure/glaucoma; PACS = primary angle closure suspect; RE = refractive error; SD = standard deviation; VL = vitreous length.

Chi-square test of association between PACD status (Normal, PACS and PAC/G) and RE status (Hyperopia, Emmetropia and Myopia).

All other p-values are from Kruskal-Wallis Test of median comparisons.

Female sex (OR = 1.81), older age (OR = 1.05 per 1 year), more hyperopic RE (OR = 1.43 per 1 diopter increase), and shallower ACD (OR = 1.79 per 0.1 mm decrease) were significantly associated with PACD status (p < 0.001) in the univariable analysis (Table 2). Associations were stable for RE (OR = 1.49) and ACD (OR = 1.75) in separate multivariable models adjusted for age and sex. The association between RE and PACD status was weaker (OR = 1.24) whereas the association between ACD and PACD status was stable (OR = 1.69) when RE and ACD were both included in single multivariable model. SRC analysis showed that ACD (SRC = − 0.54) was a 2.5-fold stronger predictor of PACD risk compared to RE (SRC = 0.22). The association between PACD status and RE was stable when PACD was stratified into PACS (OR = 1.39) and PAC/G (OR = 1.46) groups in separate multivariable models (Supplementary Table 1). The association between PACD status and ACD was similar for PACS (OR = 1.75) and PAC/G (OR = 1.67) in separate multivariable models.

Table 2.

Univariable and sex- and age-adjusted multivariable models of the association between PACD and continuous measures of RE and/or ACD.

| Parameter |

Univariable Analysis OR (CI) |

Multivariable Analysis OR (CI) |

Standardized Regression Coefficients (RE+ACD) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RE

|

ACD

|

RE+ACD

|

|||

| Age (year) | 1.05 (1.05-1.07) | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 0.03 |

| Sex (female) | 1.81 (1.48-2.22) | 2.17 (1.76-2.70) | 1.49 (1.16-1.93)* | 1.50 (1.16-1.94)* | 0.40 |

| RE (per 1D increase) | 1.43 (1.35-1.51) | 1.41 (1.33-1.49) | - | 1.24 (1.17-1.32) | 0.22 |

| ACD (per 0.1mm decrease) | 1.79 (1.72-1.89) | - | 1.75 (1.67-1.85) | 1.69 (1.64-1.79) | −0.54 |

ACD = anterior chamber depth; CI = 95% confidence interval; mm = millimeter; OR = odds ratio; PACD = primary angle closure disease; RE = refractive error.

P-values for all OR are <0.001 unless noted below.

p=0.002

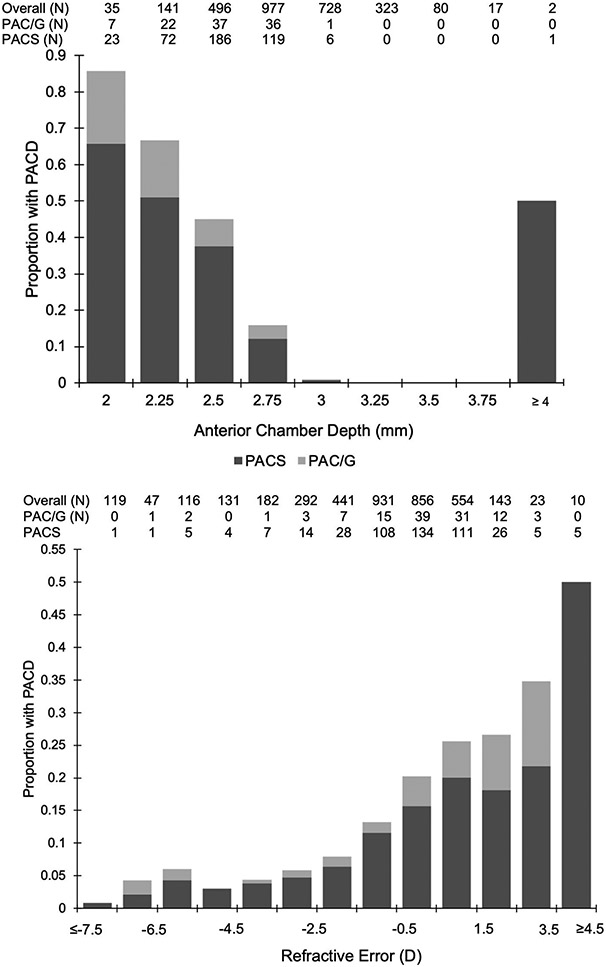

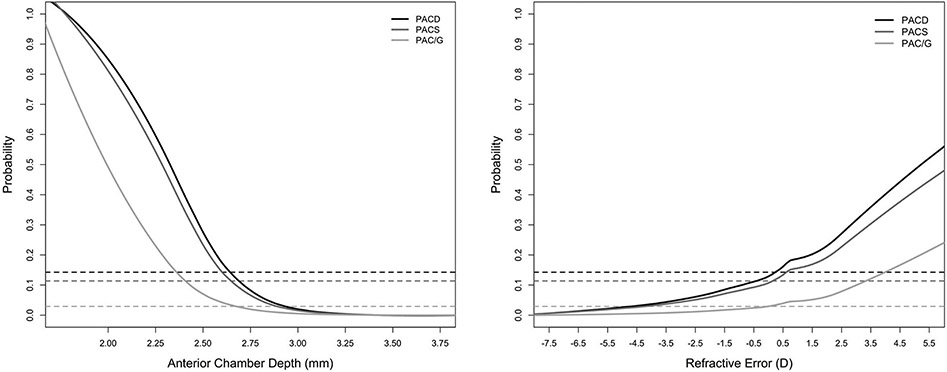

Proportions of eyes with PACS, PAC/G, and PACD increased with more hyperopic RE and shallower ACD, although sample sizes diminished at measurement extremes (Figure 1). LOWESS curves fit to predictions by the logistic regression models reflected an increase in PACD probability with increasing RE and decreasing ACD that was consistent with these data. The predicted probability of PACD exceeded that of the CHES population (12.1%) and rose rapidly at around RE of 0 D and ACD of 2.7 mm (Figure 2). These effects were similar for PACS and PAC/G groups. Furthermore, sensitivity and specificity of different RE and ACD cutoffs showed that a cutoff at +2.0 D (22.3% sensitivity, 89.1% specificity) and ACD of 2.60 mm (77.5% sensitivity, 82.3% specificity) yielded the highest sensitivity while maintaining a specificity over 80% (Table 5).

Figure 1.

Histograms showing proportion of participants with PACD (entire bar), PACS and PAC/G (grayscale bars) by ACD (top) or RE (bottom). Tables show number of participants and cases per bin.

D = diopter; mm = millimeter; PAC/G = primary angle closure/glaucoma; PACD = primary angle closure disease; PACS = primary angle closure suspect;

Figure 2.

LOWESS plots showing predicted probability of PACD, PACS, and PAC/G along continuous ranges of ACD (right) and RE (left). Dashed lines represent prevalence of respective disease category within the entire CHES cohort.

D = diopter; mm = millimeter; PAC/G = primary angle closure/glaucoma; PACD = primary angle closure disease; PACS = primary angle closure suspect.

Table 5.

Sensitivity and specificity of anterior chamber depth and refractive error cutoffs in detecting PACD.

| ACD Cutoff (mm) | Sensitivity | Specificity | RE Cutoff (D) | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| 3.2 | 99.8% | 15.9% | −5.00 | 98.8% | 9.3% |

| 3 | 98.5% | 34.4% | −4.00 | 98.0% | 12.6% |

| 2.9 | 96.3% | 46.7% | −3.00 | 97.2% | 16.5% |

| 2.8 | 94.0% | 59.1% | −2.00 | 94.7% | 23.2% |

| 2.7 | 88.3% | 72.3% | −1.00 | 91.1% | 33.7% |

| 2.6 | 77.5% | 83.2% | 0 | 82.1% | 44.9% |

| 2.5 | 63.4% | 90.2% | +1.00 | 57.0% | 70.6% |

| 2.4 | 45.2% | 95.3% | +2.00 | 22.3% | 89.1% |

| 2.3 | 28.5% | 97.8% | +3.00 | 5.1% | 98.0% |

| 2.2 | 17.6% | 98.9% | +4.00 | 1.1% | 99.6% |

ACD = anterior chamber depth; D = diopter; mm = millimeter; PACD = primary angle closure disease; RE = refractive error.

In multivariable models investigating the effect of broad categorical measures of RE on PACD and severity subtypes, odds of PACD were significantly higher for emmetropes (OR = 2.78; p < 0.001) and hyperopes (OR = 5.03 p < 0.001) compared to myopes (Table 3). Associations were similar when PACD was stratified into PACS and PAC/G groups. Finer categorical measures of RE (high and mild hyperopia; high, moderate, and mild myopia) were created and assessed using definitions established by previous studies.22,23 In multivariable models with finer categorical measures of RE, odds of PACS, PAC/G, and PACD were similar within broad RE categories (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Sex- and age-adjusted multivariable models of the association between PACD and categorical measures of RE.

| Multivariable Analysis OR (CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter |

PACD

|

PACS

|

PAC/G

|

| Age (year) | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | 1.06 (1.05-1.07) | 1.07 (1.05-1.09) |

| Sex (female) | 2.16 (1.75-2.69) | 2.61 (2.05-3.35) | 1.16 (0.79-1.73)* |

| RE | |||

| Myopia (≤−0.5D) | REFERENCE | ||

| Emmetropia (−0.5 to +0.5D) | 2.78 (2.04-3.82) | 2.90 (2.08-4.08) | 1.73 (0.82-3.63)+ |

| Hyperopia (≥+0.5D) | 5.03 (3.89-6.59) | 5.09 (3.84-6.84) | 5.49 (3.24-9.95) |

CI = 95% confidence interval; D = diopter; OR = odds ratio; PACD = primary angle closure disease; PAC/G = primary angle closure / glaucoma; PACS = primary angle closure suspect; RE = refractive error.

P-values for all OR are <0.001 unless noted below.

p=0.46

p=0.15

Biometric data from ultrasound A-scan and AS-OCT were available for 564 out of 567 eyes with PACD. Comparison of biometric measurements between myopes, emmetropes, and hyperopes with PACD revealed VL and AL differences (p < 0.001) between RE groups (Table 4) whereas no differences were found between ACD, LV, LT, IA, ACW, AOD750, and TISA750 (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Differences among biometric measurements between myopes, emmetropes, and hyperopes with PACD.

| Multivariable Analysis Mean (SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Myopia (N=75) |

Emmetropia (N=109) |

Hyperopia (N=380) |

P-value * |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ultrasound A-scan | ||||

| CCT (μm) | 561.5 (39.94) | 558.90 (32.70) | 558.02 (34.25) | 0.47 |

| ACD | 3.02 (0.33) | 3.00 (0.27) | 2.97 (0.24) | 0.36 |

| Vitreous Length | 15.6 (1.12) | 14.376 (0.73) | 14.47 (0.75) | <0.001 |

| Axial Length | 23.62 (1.14) | 22.98 (0.80) | 22.67 (0.73) | <0.001 |

| Lens Thickness | 4.71 (0.41) | 4.67 (0.31) | 4.67 (0.36) | 0.84 |

| AS-OCT | ||||

| Lens Vault | 0.78 (0.23) | 0.76 (0.22) | 0.78 (0.12) | 0.59 |

| Iris Area (mm2) | 1.57 (0.21) | 1.58 (0.19) | 1.59 (0.21) | 0.91 |

| ACW | 10.78 (1.69) | 10.95 (1.50) | 11.22 (1.18) | 0.67 |

| AOD750 | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.17 (0.07) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.95 |

| TISA750 (mm2) | 0.092 (0.032) | 0.094 (0.041) | 0.094 (0.036) | 0.99 |

ACD = anterior chamber depth; ACW = anterior chamber width (horizontal scleral spur-to-spur distance); AOD750 = angle opening distance 750 (perpendicular distance from the trabecular meshwork at 750 μm from the scleral spur); A-scan = amplitude scan; AS-OCT = anterior segment ocular coherence tomography; PACD = primary angle closure disease; SD = standard deviation; TISA750 = trabecular iris surface area 750 (area of a trapezoid bounded anteriorly by the AOD750, posteriorly by a line drawn from the scleral spur perpendicular to the plane of the inner scleral wall to the iris, superiorly by the inner corneoscleral wall, and inferiorly by the iris surface).

Statistically significant p-values are bolded

Kruskal-Wallis test of medians.

Units are in mm unless otherwise noted.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we assessed the role of RE and ACD as risk factors for PACD among a population-based cohort of Chinese Americans. We find that risk of PACD, including PAC/G, rises rapidly in eyes with any degree of hyperopia and ACD less than 2.7 mm. We also find that ACD is a 2.5-fold stronger predictor of PACD status compared to RE. We believe these findings provide important insights into the clinical roles of RE and ACD for identifying patients at higher risk for angle closure, especially given the low utilization of gonioscopy by eye care providers and the ocular morbidity associated with PACG.7

Our findings support the importance of hyperopia as a risk factor for PACD and motivating factor for gonioscopy. In our continuous analysis of RE, risk of PACD, including PAC/G, rises rapidly even with low degrees of hyperopia. These findings are consistent with previous studies, including a large multi-ethnic hospital-based study that reported a 28% increase in odds of PACG per diopter increase in RE.11 Interestingly, the PACD probability associated with the takeoff point, which lies close to emmetropia, approximates the average risk of PACD (12.1%) in the CHES population. This relationship holds true for both PACS and PAC/G groups, which suggests that RE cutoffs for risk-stratifying patients are conserved across disease severities. In our categorical analysis of RE, hyperopes had at least 5.5 times higher odds of PACS, PAC/G, or PACD than myopes. These results corroborate findings by large, population-based studies on RE and PACD in Asian and multiethnic populations.11,14 However, it is important to reiterate that PACD risk is not uniform among all hyperopes, as some eyecare providers may be led to believe based on categorical studies of RE as a PACD risk factor.22 These findings suggest that high hyperopes (≥ +2.0 D) may benefit from gonioscopy regardless of glaucoma suspect status based on other risk factors.

Our statistical models predict lower risk of PACD in myopic eyes, especially those with moderate or high degrees of myopia. The proportion of myopic PACD in our study (13.3%) was lower than hospital- and clinic-based studies in Asia that reported higher proportions of myopic PACD (17.9% to 37.2%).12,24,25 One explanation for this difference is that myopic patients are more likely to seek eye care and be diagnosed with PACD in hospital- and clinic-based compared to community-based settings. An alternative explanation is that the proportion of myopic PACD is influenced by regional differences in myopia prevalence; population-based studies on myopia reported higher prevalence in Singapore than China and higher prevalence in urban than rural populations.26,27 Despite this lower risk of PACD among myopes, we reiterate that it is crucial to perform gonioscopy in all patients receiving evaluations for glaucoma as per AAO recommendation.

Among biometric parameters describing the anterior segment, ACD is well-established as a strong predictor of angle closure and determinant of angle width.10,15,28 We found PACS and PACD risk rapidly rose when ACD dropped below 2.7 mm. The clinical significance of this cutoff is corroborated by multiple other studies. The population-based Liwan Eye Study reported that an ACD cutoff of 2.7 mm was associated with a rapid rise in prevalence of occludable angles (consistent with our study definition of PACD) and provided the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for predicting 10-year incident PACD.29,30 In the Singapore Asymptomatic Narrow Angle Study (ANA-LIS), the mean ACD of participants with bilateral PACS was also 2.7 mm.31 In addition, we found that PAC/G risk rapidly rose when ACD dropped below 2.4 mm, which is consistent with a previous report that the risk of peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) rises below an ACD cutoff of 2.4 mm.32 While these cutoffs are highly consistent, we recognize that PACD risk conferred by ACD may vary by population, and further work is needed to assess the benefit of using specific ACD cutoffs to screen for PACD or guide prophylactic treatment with laser or surgery.

Standardized regression coefficients in our multivariable model with both RE and ACD support that ACD is a substantially stronger predictor of PACD risk than RE. For example, a RE cutoff of +2.0 D provided a specificity of 89.1% but a sensitivity of only 22.3% whereas an ACD cutoff of 2.6 mm provided a specificity of 83.2% and specificity of 77.5%. The association between RE and PACD risk remains significant even after adjusting for ACD, suggesting that RE conveys independent information about PACD risk. However, the clinical utility of ACD as risk factor for PACD and guide for performing gonioscopy is limited as it is rarely measured outside of pre-operative biometry. We also found that odds ratios and LOWESS curves from separate multivariable models for PACS and PAC/G eyes resembled those from all PACD eyes, which suggests that the role of RE and ACD are generally consistent across different severities of PACD. However, this finding may not generalize to populations outside of CHES, as other studies found differences in ACD between PACS and PAC/G that was absent in CHES.33,34

Clarifying the role of RE as a risk factor in PACD is crucial to forecast the effects of increasing myopia prevalence worldwide on PACG prevalence. One prevailing belief is that the prevalence of PACD, including PACG, will decrease as the prevalence of myopia increases.29 This belief is supported by our findings that myopes, especially high myopes, have significantly lower risk of PACD compared to hyperopes. However, others have proposed that increased myopia prevalence will only have small effects on population ACD and therefore PACD prevalence.29 We found that among CHES participants with PACD, there was no significant difference in ACD between myopes, emmetropes, and hyperopes, whereas there was a significant difference in AL and VL, which is consistent with previous studies.12,35 These findings raise the question: what biometric changes are responsible for recent increases in myopia prevalence? If shifts toward myopia are primarily due to elongation of the vitreous cavity, then effects on PACG prevalence may be mitigated.

Our study has several limitations. First, the CHES cohort is comprised entirely of Chinese Americans aged 50 years or older living in Los Angeles, California. Therefore, our findings and models may not generalize to individuals of other races, ages, or geographic locations. Second, we did not separate PACD cases based on angle closure mechanism such as pupillary block or plateau iris, which leaves the possibility that relationships with RE and ACD may vary by mechanism.36 Finally, the sample size of participants with over −5.5 diopters of myopia (N = 133) and 3.5 diopters of hyperopia (N = 50) was small, which limits the reliability of our models at the extremes of RE.

This study helps clarify the role of RE and ACD for guiding gonioscopy to detect PACD, at least among Chinese Americans. Given the current under-utilization of gonioscopy in eye exams, we hope these findings encourage eye care providers to be vigilant about evaluating patients for angle closure and serve as a reminder that high hyperopes who have not been designated as glaucoma suspects may benefit from gonioscopy. Our findings also highlight the need for more convenient diagnostic tools, such as AS-OCT imaging supported by artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, to directly detect or evaluate biometric risk factors for angle closure.37-39 Regardless of the method, it remains imperative that patients with angle closure be detected and evaluated prior to the development of PACG and associated vision loss.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Study attrition diagram.

Supplementary Table 1. Sex- and age-adjusted multivariable models of the association between PACS or PAC/G and continuous measures of RE or ACD.

Supplementary Table 2. Sex- and age-adjusted multivariable models of the association between PACD and fine categorical measures of RE.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants EY-017337 and K23 EY029763 from the National Eye Institute, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; a Young Clinician Scientist Research Award from the American Glaucoma Society; and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY. S.Z. was supported by the Dean’s Research Scholars Program of the Keck School of Medicine.

Sources of support:

National Institutes of Health (NIH), American Glaucoma Society (AGS), Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB), Keck School of Medicine (KSOM)

Footnotes

Disclosures

S.Z., A.A.P., B.B., G.A., A.C., M.T., R.M., X.J., R.V., and B.Y.X. have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley H, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan Y, Varma R. Natural history of glaucoma. In: Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Vol 59. Wolters Kluwer -- Medknow Publications; 2011:S19. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.73682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster PJ. The epidemiology of primary angle closure and associated glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2002;17(2):50–58. doi: 10.1076/soph.17.2.50.14718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster PJ, Buhrmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(2):238–242. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gedde SJ, Vinod K, Wright MM, et al. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(1):P71–P150. doi: 10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2020.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman AL, Yu F, Evans SJ. Use of gonioscopy in medicare beneficiaries before glaucoma surgery. J Glaucoma. 2006;15(6):486–493. doi: 10.1097/01.IJG.0000212287.62798.8F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hertzog LH, Albrecht KG, LaBree L, Lee PP. Glaucoma care and conformance with preferred practice patterns. Examination of the private, community-based ophthalmologist. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(7):1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30573-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apolo G, Bohner A, Pardeshi A, et al. Racial and Sociodemographic Disparities in the Detection of Narrow Angles before Detection of Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma in the United States. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. Published online January 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2022.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe RF. Aetiology of the anatomical basis for primary angle-closure glaucoma. Biometrical comparisons between normal eyes and eyes with primary angle-closure glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1970;54(3):161–169. doi: 10.1136/bjo.54.3.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen L, Melles RB, Metlapally R, et al. The Association of Refractive Error with Glaucoma in a Multiethnic Population. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yong KL, Gong T, Nongpiur ME, et al. Myopia in Asian subjects with primary angle closure: Implications for glaucoma trends in East Asia. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(8):1566–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nongpiur ME, Tun TA, Aung T. Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography: Is There a Clinical Role in the Management of Primary Angle Closure Disease? J Glaucoma. 2020;29(1):60–66. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, Cao WF, Wang YX, Chen CX, Jonas JB. Anterior Chamber Depth and Chamber Angle and Their Associations with Ocular and General Parameters: The Beijing Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(5):929–936.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alsbirk PH. Anterior chamber depth and primary angle-closure glaucoma I. An epidemiologic study in Greenland Eskimos. Acta Ophthalmol. 1975;53(1):89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varma R, Hsu C, Wang D, Torres M, Azen SP. The Chinese American eye study: Design and methods. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20(6):335–347. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2013.823505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho SW, Baskaran M, Zheng C, et al. Swept source optical coherence tomography measurement of the iris-trabecular contact (ITC) index: A new parameter for angle closure. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(4):1205–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2158-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu BY, Israelsen P, Pan BX, Wang D, Jiang X, Varma R. Benefit of measuring anterior segment structures using an increased number of optical coherence tomography images: The Chinese American Eye Study. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):6313–6319. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan J, Pardeshi A, Jiang X, et al. Optimal number and orientation of anterior segment OCT images to measure ocular biometric parameters in angle closure eyes: the Chinese American Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. Published online January 2022:bjophthalmol-2021-319275. doi: 10.1136/BJOPHTHALMOL-2021-319275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu BY, Burkemper B, Lewinger JP, et al. Correlation between Intraocular Pressure and Angle Configuration Measured by OCT. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2018;1(3):158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pardeshi AA, Song AE, Lazkani N, Xie X, Huang A, Xu BY. Intradevice Repeatability and Interdevice Agreement of Ocular Biometric Measurements: A Comparison of Two Swept-Source Anterior Segment OCT Devices. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(9):14. doi: 10.1167/tvst.9.9.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dandona L, Dandona R, Mandal P, et al. Angle-closure glaucoma in an urban population in Southern India: The Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(9):1710–1716. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00274-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loh CC, Kamaruddin H, Bastion MLC, Husain R, Mohd Isa H, Md Din N. Evaluation of Refractive Status and Ocular Biometric Parameters in Primary Angle Closure Disease. Ophthalmic Res. 2021;64(2):246–252. doi: 10.1159/000510925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohamed-Noor J, Abd-Salam D. Refractive errors and biometry of primary angle-closure disease in a mixed Malaysian population. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(8):1246–1250. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2017.08.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu L, Li J, Cui T, et al. Refractive Error in Urban and Rural Adult Chinese in Beijing. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(10):1676–1683. doi: 10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2005.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan CW, Saw SM, Wong TY. Epidemiology of Myopia. Pathol Myopia. Published online January 1, 2014:25–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8338-0_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu BY, Lifton J, Burkemper B, et al. Ocular Biometric Determinants of Anterior Chamber Angle Width in Chinese Americans: The Chinese American Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;220:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin G, Ding X, Guo X, Wing Chang BH, Odouard C, He M. Does myopia affect angle closure prevalence. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(9):5714–5719. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Ye H, Zhang Q, et al. Association between Myopia, Biometry and Occludable Angle: The Jiangning Eye Study. Published online 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baskaran M, Kumar RS, Friedman DS, et al. The Singapore Asymptomatic Narrow Angles Laser Iridotomy Study: Five-Year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(2):147–158. doi: 10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aung T, Nolan WP, Machin D, et al. Anterior chamber depth and the risk of primary angle closure in 2 East Asian populations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(4):527–532. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu BY, Liang S, Pardeshi AA, et al. Differences in Ocular Biometric Measurements among Subtypes of Primary Angle Closure Disease. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2020;0(0). doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma P, Wu Y, Oatts J, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic performance of swept-source anterior segment optical coherence tomography in primary angle closure disease. Am J Ophthalmol. Published online July 17, 2021. doi: 10.1016/J.AJO.2021.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter GM, Wang M, Jiang X, et al. Ocular determinants of refractive error and its age- and sex-related variations in the Chinese American eye study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):724–732. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moghimi S, Torkashvand A, Mohammadi M, et al. Classification of primary angle closure spectrum with hierarchical cluster analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(7). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nongpiur ME, Haaland BA, Perera SA, et al. Development of a score and probability estimate for detecting angle closure based on anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(1). doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu BY, Chiang M, Pardeshi AA, Moghimi S, Varma R. Deep Neural Network for Scleral Spur Detection in Anterior Segment OCT Images: The Chinese American Eye Study. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(2):18–18. doi: 10.1167/TVST.9.2.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu BY, Chiang M, Chaudhary S, Kulkarni S, Pardeshi AA, Varma R. Deep Learning Classifiers for Automated Detection of Gonioscopic Angle Closure Based on Anterior Segment OCT Images. Published online 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Study attrition diagram.

Supplementary Table 1. Sex- and age-adjusted multivariable models of the association between PACS or PAC/G and continuous measures of RE or ACD.

Supplementary Table 2. Sex- and age-adjusted multivariable models of the association between PACD and fine categorical measures of RE.