Summary

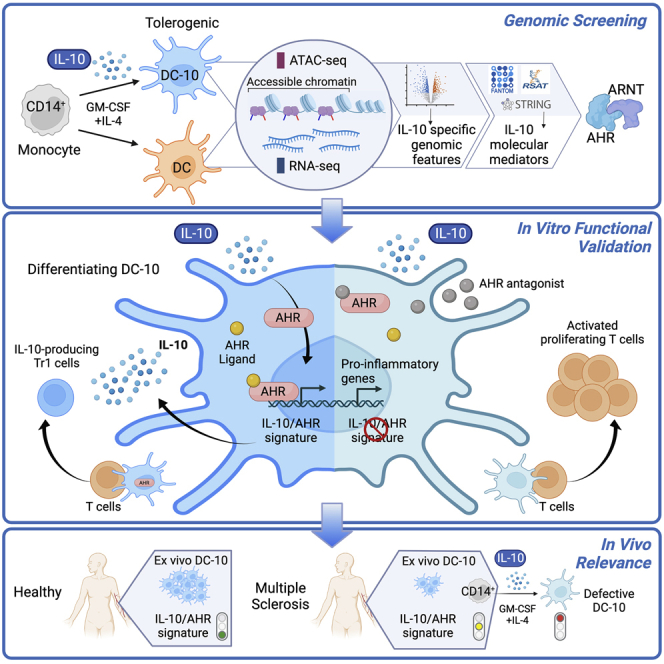

Interleukin (IL)-10 is a main player in peripheral immune tolerance, the physiological mechanism preventing immune reactions to self/harmless antigens. Here, we investigate IL-10-induced molecular mechanisms generating tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDC) from monocytes. Using genomic studies, we show that IL-10 induces a pattern of accessible enhancers exploited by aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) to promote expression of a set of core genes. We demonstrate that AHR activity occurs downstream of IL-10 signaling in myeloid cells and is required for the induction of tolerogenic activities in DC. Analyses of circulating DCs show that IL-10/AHR genomic signature is active in vivo in health. In multiple sclerosis patients, we instead observe significantly altered signature correlating with functional defects and reduced frequencies of IL-10-induced-tolDC in vitro and in vivo. Our studies identify molecular mechanisms controlling tolerogenic activities in human myeloid cells and may help in designing therapies to re-establish immune tolerance.

Keywords: interleukin-10, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, tolerogenic DC, chromatin accessibility, transcriptome, immune tolerance, DC-10, regulatory type 1 T cells, Tr1 cells, multiple sclerosis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

IL-10 imprints chromatin and transcriptome in monocyte-derived tolDCs

-

•

AHR activity is needed downstream of IL-10 to establish IL-10 induced core genes

-

•

IL-10/AHR genomic signature is evident in vivo in healthy tolDCs

-

•

MS patients show alterations in IL-10/AHR genomic signature and tolDCs

Avancini et al. investigate IL-10-mediated induction of human tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDCs) and identify AHR as a key player for establishing genomic and tolerogenic features. They find the IL-10/AHR genomic signature active in circulating healthy tolDCs and altered in multiple sclerosis patients’ IL-10-induced, functionally defective tolDCs.

Introduction

Peripheral immune tolerance is maintained by regulatory cells, immune subsets that control effector responses. T regulatory cells (Tregs) have long been recognized and studied, while antigen-presenting regulatory cells were more recently identified. Therefore, while the molecular mechanisms and gene expression patterns defining the identity and function of Tregs have been deeply studied, the molecular patterns driving tolerogenic activities in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) remain less defined.1

Regulatory cells act via cell-cell contact inhibitory mechanisms and secretion of anti-inflammatory factors. One of the most studied anti-inflammatory cytokines is interleukin-10 (IL-10). Originally identified as a stimulatory cytokine produced by CD4+ T helper type 2 (Th2) cells, IL-10’s immunosuppressive functions on both APC and T cells have then been well established.2 Accordingly, alterations in IL-10 pathways result in loss of immune tolerance and uncontrolled inflammatory responses leading to human pathologies, such as inflammatory bowel disease and neuroinflammation.3,4 The canonical IL-10/IL-10 receptor pathway signals through STAT3, which directly alters gene expression to activate the anti-inflammatory program.2 However, STAT3 can also activate pro-inflammatory genes. The net result of IL-10-mediated gene expression pattern is strictly dependent on the cellular context in which STAT3 is activated, likely relying on the expression of co-factors and the chromatin accessibility of target genes and regulatory elements.5 IL-10 is produced by many immune cells and its expression is regulated by the integration of different stimuli through several pathways.6 In myeloid cells, IL-10 expression is typically activated downstream of pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLR), while both TCR and lineage-inducing cytokines can stimulate IL-10 expression in CD4+ cells. The transcription factor c-MAF appears to act as a transcriptional activator of IL-10 in myeloid and lymphoid immune cells, while its partner aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) has been described as a key activator of IL-10 gene transcription specifically in T regulatory Type 1 (Tr1) cells.7

AHR is a ubiquitously expressed protein, originally identified as an intracellular sensor of environmental pollutants and later recognized as a mediator of numerous cellular processes, including immune responses.8 AHR resides in the cytoplasm under steady-state conditions. Upon binding to an agonist, AHR binds to its canonical partner AHR Nuclear Translocator (ARNT) and translocates to the nucleus, where it can modulate gene transcription. AHR system is highly complex and can activate different gene patterns depending on its ligand and binding partner(s). Several endogenous/exogenous ligands can act as AHR agonists/antagonists (e.g., tryptophan catabolites, diet derivatives, microbiota metabolites), while several interacting protein partners have been documented (e.g., NF-κB, STATs, epigenetic regulators).8,9,10 This implies that the biological result of AHR activation is strictly contextual. Accordingly, in mice, AHR can induce both inflammatory (Th17) and tolerogenic (Tr1 and Treg) pathways.8,9 In humans, instead, AHR activity in immune cells has been mainly associated with tolerogenic mechanisms, as described in monocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and B cells.11,12,13,14,15 AHR has also been shown to control human monocyte differentiation into DCs vs. macrophages.16

We have previously investigated IL-10-mediated induction of regulatory activity in human myeloid cells. Several protocols have exploited the immunosuppressive abilities of IL-10 to generate tolerogenic (tol)DCs, which can be used as a model system for basic studies and as therapeutic tools to re-establish immune tolerance in human T cell-mediated pathologies. Among them, we have developed an in vitro IL-10-based protocol to differentiate tolDCs from human monocytes. These tolDCs, termed DC-10s, can efficiently generate Tr1 cells via secretion of IL-10 and expression of the tolerogenic molecules ILT-4 and HLA-G.17 We have also identified naturally occurring DC-10s in human peripheral blood, which shares markers, mechanisms of action, and gene transcription patterns with its in vitro counterpart and the numbers of which positively correlate with enhanced tolerance.17,18,19,20

Here, we used DC-10s as a model to assess IL-10-directed chromatin and transcriptome patterns in human tolDC. We found that IL-10 induces a pattern of accessible enhancers, which are exploited by AHR to promote expression of a set of core genes needed for IL-10-mediated induction of tolerogenic activities (e.g., suppression of T cell responses and induction of Tr1 cells) in myeloid cells. IL-10-induced enhancers and core genes were also specifically active in ex vivo isolated DC-10s, and their alteration correlated with human autoimmune conditions. This study identifies an IL-10-induced molecular mechanism required for establishing tolerogenic functions in human myeloid cells.

Results

IL-10 alters chromatin accessibility and transcription in human dendritic cells

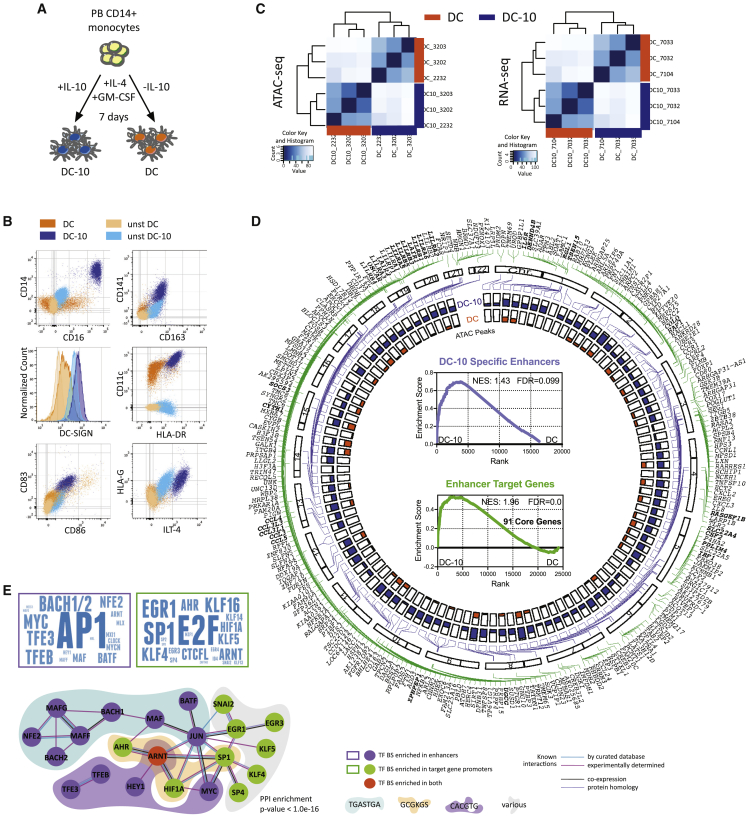

We investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying IL-10-mediated induction of tolerogenic myeloid cells by using DC-10s as a cellular model in comparison with monocyte-derived DCs (Figure 1A). DC-10s are CD14+CD16+CD141+CD163+ and express DC-SIGN, HLA-DR, CD83, and CD86, and the tolerogenic molecules HLA-G and ILT-4 (Figures 1B and S1A).

Figure 1.

IL-10 impacts chromatin and transcription in DCs

(A) Experimental design. Peripheral blood (PB) CD14+ monocytes were differentiated for 7 days in presence of GM-CSF and IL-4, with (DC-10) or without (DC) IL-10.

(B) Representative plots of DC and DC-10 phenotype by flow cytometry (FC).

(C) Unsupervised clustering heatmaps of ATAC-seq (left) and RNA-seq (right) data from DC and DC-10 from three independent donors.

(D) Circoplot depicting the following: outer layer, location of FANTOM5-identified DC-10-specific enhancers (purple lines), and enhancer target genes (green lines) along chromosomes (bold genes = targets of multiple enhancers); inner layer, ATAC broadpeak maximum value for each enhancer in DC-10s (blue) and DCs (orange). Inner core: GSEA analysis of DC-10-specific enhancers (top, purple) and enhancer target genes (bottom, green) in DC-10 vs. DC transcriptome. Normalized enriched score (NES), false discovery rate (FDR), and number of core genes (bottom) are indicated.

(E) Transcription factor (TF) binding predictions. Left, word clouds displaying TFs whose binding sites (BSs) were significantly enriched in the 107 DC-10 enhancers (top, purple) and 268 DC-10 enhancer target protein-coding gene promoters (bottom, green); size of TF is proportional to its enrichment score from motif finder analysis. Right, protein-protein interaction network built on TF from word clouds; only connected nodes are shown. Colored clouds identify TFs with shared BSs, with consensus site indicated below. PPI, protein-protein interaction. See Figure S1.

We used ATAC-seq and RNA-seq to assess chromatin accessibility and transcriptome in DC-10s and DCs differentiated from three independent donors. Following ATAC protocol validation (Figures S1B and S1C), differential analysis revealed that DC-10s and DCs clustered apart and showed thousands of differentially accessible regions and expressed transcripts (Figures 1C and S1D), consistent with the previously described transcriptional profile of DC-10s.18 Matching results obtained by edgeR and DESeq2 algorithms identified 1,593 genomic regions as specifically accessible in DC-10s and not in DCs.

By interrogating FANTOM5 human enhancer atlas21 with the identified DC-10-specific accessible regions, we identified 107 regions defined as robust enhancers that putatively control 268 protein-coding genes (Figure 1D, Table S1). Since active enhancers are actively transcribed and decorated by specific histone marks, we assessed transcription and histone marking of the 107 identified DC-10-specific enhancers.22,23 Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that DC-10-specific enhancers were transcribed and significantly more expressed in DC-10s as compared with DCs (Figure 1D, inner core, top graph). Identified enhancers were also enriched in H3K4me1 and H3K27ac modifications, validating them as bona fide DC-10 active enhancers (Figure S1E). GSEA confirmed significant enrichment in expression of the 268 protein-coding genes associated with DC-10-specific enhancers in DC-10s compared with DCs, further supporting the relevance of the identified enhancer/target gene network in DC-10s, and allowed us to define the leading-edge subset of 91 target genes as DC-10 core genes (Figure 1D, inner core, bottom graph, Table S2).

To identify transcription factors (TFs) that might control DC-10-specific enhancer and gene activity, we used the regulatory sequence analysis tools (RSAT) peak motifs tool. Enhancer and gene promoter sequences were enriched for binding of pleiotropic (AP1, MYC), Treg-associated (BACH2, MAF/ARNT, BATF, TFEB), and broad-function (E2F, SP/KLF family, EGR)7,24,25 TFs. Interestingly, we also found enrichment for ARNT complex (AHR/ARNT/HIF1α) binding sites (Figures 1E and S1F). When assessing functional associations using String,26 we found that TFs putatively binding to DC-10-specific enhancers and promoters were significantly enriched for interactions, when compared with randomly selected TFs, and formed a network around an AHR/ARNT core (Figures 1E and S1G).

These results indicate that IL-10 exposure during monocyte-derived tolDC differentiation prompts the establishment of a specific genomic signature, the activity of which might be controlled by the AHR pathway.

AHR activity regulates IL-10-mediated induction of regulatory functions in DCs

Considering the established roles of AHR in immune tolerance and DC differentiation,7,16,27,28,29,30 we investigated the function of AHR in IL-10-mediated tolDC differentiation and function.

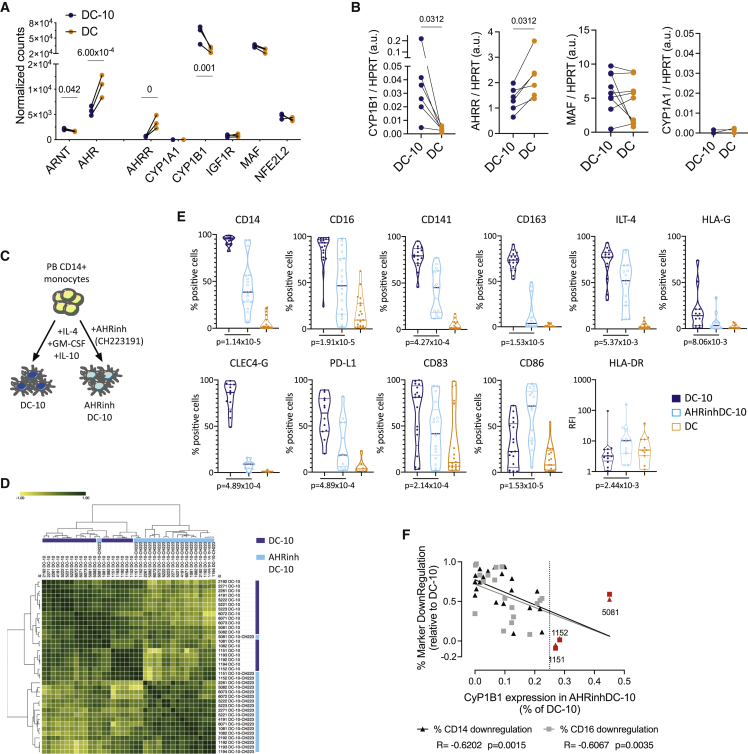

We first verified the activity of the AHR pathway in DC-10s and DCs. In the DC-10 transcriptome, although AHR expression was reduced, the expression of some of its canonical target genes was significantly upregulated as compared with DCs (Figure 2A). However, the AHR functional repressor AHRR was downregulated, suggesting increased AHR activity in DC-10s. We validated by ddPCR differential expression of CYP1B1 and AHRR in DC-10s vs. DCs (Figure 2B). MAF expression was not differentially expressed, and CYP1A1 was not expressed in either condition (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

AHR activity characterizes IL-10-induced tolDC

(A) Expression of AHR-related molecules in DC-10s and DCs by RNA-seq; significant false discovery rates (FDRs) are shown.

(B) Expression of AHR targets by ddPCR. The ratio between molecules/μL of the target gene and molecules/μL of the reference HPRT gene is shown in arbitrary units (a.u.). p value by Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

(C) Experimental design. Peripheral blood (PB) CD14+ monocytes were differentiated for 7 days in the presence of GM-CSF, IL-4, and IL-10 with (AHRinhDC-10) or without (DC-10) AHR inhibitor CH223191. (D and E) Phenotype of DC-10, AHRinhDC-10, and DC by flow cytometry (FC).

(D) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of DC-10 and AHRinhDC-10 samples based on FC parameters shown in (E).

(E) Violin plots displaying median, interquartile range, and single values of percentages of positive cells or relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) for the indicated markers in DC-10, AHRinhDC-10, and DC samples gated on CD11c+ Live/Dead negative population. p values by Wilcoxon matched pairs test (n = 19).

(F) Correlation plot between percentage of CD14 and CD16 downregulation (expressed as 1 − [% positive cells in AHRinhDC-10/% positive cells in donor-matched DC-10]) and CYP1B1 expression in AHRinhDC-10 (% of DC-10) (expressed as normalized CYP1B1 expression in AHRinhDC-10/normalized CYP1B1 expression in DC-10). Linear interpolation, Spearman R and p values are indicated for each marker. Dotted line indicates 25% residual CYP1B1 expression. Samples with a CYP1B1 residual expression >25% are indicated in red. See Figure S2.

To test whether activation of AHR is required for DC-10 differentiation, we differentiated DC-10s in the presence of the AHR-specific antagonist CH223191 (Figure 2C). AHR-inhibited DC-10 (AHRinhDC-10) yield at the end of differentiation was mildly, although statistically significant, reduced compared with DC-10 (Figure S2A). Consistent with a role for AHR activity downstream of IL-10, AHRinhDC-10s showed a deeply altered phenotype and clustered apart from DC-10s in an unsupervised analysis based on Spearman correlation (Figure 2D). Despite donor variability, AHRinhDC-10s displayed significantly decreased expression of DC-10-specific markers (CD14, CD16, CD141, CD163, and CLEC4G) and the tolerogenic molecules ILT-4, HLA-G, and PD-L1, and an increased expression of CD86 and HLA-DR (Figures 2D, 2E, and S2B). DC differentiation was not affected by AHR inhibition, as indicated by comparable DC-SIGN and CD206 levels in AHRinhDC-10s and DC-10s. CD1a expression, which is very low/negative in DC-10,17 was further downregulated in AHRinhDC-10s (Figure S2C). The magnitude of the differences in marker expression between DC-10s and AHRinhDC-10s varied among matched samples. To assess whether different levels of AHR inhibition by CH223191 may explain this variability, we measured the expression of CYP1B1 at the end of differentiation in donor-matched samples. In most cases, we CYP1B1 expression in AHRinhDC-10s was below 25% of the expression detected in donor-matched DC-10 (Figure 2F), indicating that CH223191 efficiently antagonized AHR activity.31,32 CYP1B1 residual expression in AHRinhDC-10s inversely correlated with the extent of DC-10-specific marker downregulation, with the three samples showing >25% CYP1B1 expression clustering together with DC-10 (Figures 2F and 2D). Overall, these results indicate that AHR activity is necessary for the establishment of a tolerogenic phenotype in IL-10-induced DCs.

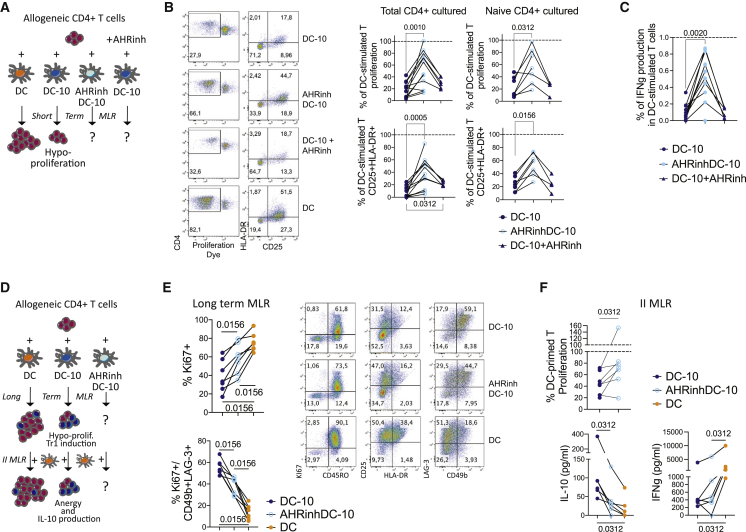

We then investigated the impact of AHR inhibition on IL-10-induced tolerogenic functions: inhibition of T cell proliferation and induction Tr1 cells17 (Figures 3A and 3D). Allogeneic CD4+ T cells were stimulated with DCs, mature DCs (mDCs), DC-10s, AHRinhDC-10s, or with DCs or DC-10s in the presence of CH223191. AHRinhDC-10s induced significantly higher T cell proliferation and activation compared with DC-10s, which, as expected, induced T cell hypo-proliferation and hypo-activation (Figures 3B, S3A, and S3B). Consistently, T cells stimulated by AHRinhDC-10s produced significantly higher levels of IFNγ than DC-10-stimulated T cells (Figures 3C and S3C). The observed differences were due to increased stimulation by AHRinhDC-10s and not to a bystander effect from AHR antagonist leftover in culture, as the addition of CH223191 during CD4+ T cell stimulation did not affect proliferation and IFNγ production (Figures 3B, 3C, and S3A–S3C). Increased response to AHRinhDC-10s was observed in both total and naive CD4+ T cells, indicating that AHRinhDC-10s were bona fide DCs and not undifferentiated monocytes, which cannot prime naive T cells (Figures 3B, 3C, and S3B).

Figure 3.

AHR activation is necessary for IL-10-induced tolerogenic functions in tolDCs generated in vitro

(A) Short-term MLR experimental design. DC stimulation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells for 5 days induces T cell proliferation, while DC-10 stimulation induces T cell hypo-proliferation.

(B) Left, representative plots of proliferation dye dilution (left plots) and CD25 and HLA-DR expression (right plots). Right, percentages of proliferating (top) and CD25+HLA-DR+ activated (bottom) cells after co-culture of total (left graphs, n = 12) and naive (right graphs, n = 7) CD4+ T cells with DC-10s, AHRinhDC-10s, and DC-10s in the presence of AHR inhibitor, relative to the results obtained with donor-matched DC-stimulated T, set at 100% (dotted line).

(C) IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells (total and naive) stimulated with DC-10s, AHRinhDC-10s, and DC-10s in presence of AHR inhibitor, expressed as ratios to the IFNγ production of T cells stimulated by donor-matched DCs, set at 1 (dotted line) (n = 11).

(D) Long-term and secondary (II) MLR experimental design. DC stimulation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells for 10 days induces T cell proliferation, DC-10 stimulation induces T cell hypo-proliferation and generation of Tr1 cells. II MLR: upon re-stimulation with mature DCs from the same donor used in priming, DC-primed T cells proliferate, while DC-10-primed T cells are anergic and produce IL-10.

(E) Long-term MLR. Left, percentage of CD4+ cells proliferating (Ki67+; top) and of Tr1 cells (CD49b+LAG3+; bottom) upon stimulation with DC-10s, AHRinhDC-10s, and DCs (n = 7). Right, representative FC plots.

(F) II MLR. Top, percentage of proliferation of T cells primed with the indicated DCs and restimulated with mature DCs from the same donor used in priming, expressed as (% proliferating cells/% proliferating cells in the donor-matched T cells primed with DCs) (n = 7); 0% = no proliferation; 100% = proliferated as DC-stimulated. Bottom, IL-10 and IFNγ amounts in culture supernatants (n = 6). p values by Wilcoxon matched pairs test. See Figure S3.

We found proliferation and activation of AHRinhDC-10-stimulated T cells significantly higher when compared with DC-10-stimulated T cells also in long-term mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay (Figures 3D, 3E, and S3D). Meanwhile, the percentage of induced Tr1 cells, assessed by co-expression of LAG-3 and CD49b,33 was significantly lower (Figure 3E). Moreover, when restimulated with allogeneic DCs generated from the same DC donor used in priming, AHRinhDC-10-primed T cells showed significantly reduced anergic response and IL-10 production, increased activation, and IFNγ production compared with DC-10-primed T cells (Figures 3F and S3E).

Together, these findings indicate that IL-10-induced differentiation of tolDC is severely impaired when AHR activation is abolished.

AHR-induced tolerogenic features are dependent on IL-10 and are abrogated by MTOR pathway activation

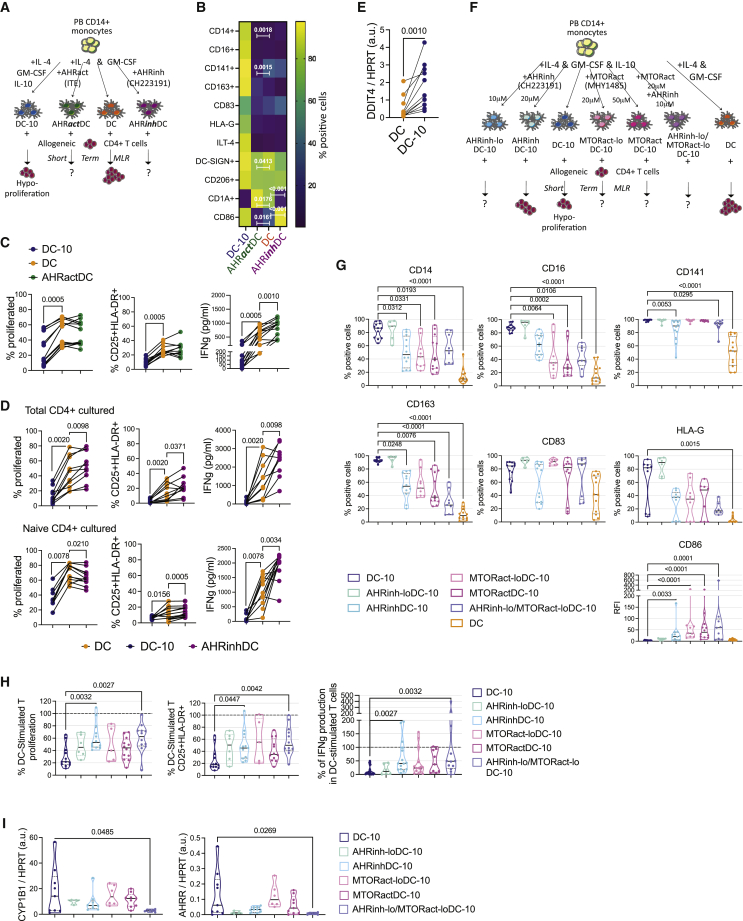

AHR activation can modulate human monocyte-derived DCs toward a regulatory phenotype, independently of IL-10.34,35 We thus investigated if AHR inhibition or activation were able per se to induce a pro-inflammatory or tolerogenic skew, respectively, in monocyte-derived DCs. To test if AHR activation can prompt DC-10-like cell differentiation, we differentiated DCs in the presence of ITE, a non-toxic AHR agonist able to induce human Treg differentiation,36,37 while we differentiated DCs in the presence of CH223191 to test if AHR inhibition induced per se a pro-inflammatory skew. DC-10s were used as tolerogenic reference (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

AHR-induced tolerogenic features are dependent on IL-10 and MTOR pathway inhibition

(A–D) Peripheral blood (PB) CD14+ monocytes were differentiated for 7 days in the presence of GM-CSF, IL-4 and IL-10 (DC-10), GM-CSF, and IL-4 without (DC) or with the AHR agonist ITE (30 μM) (AHRactDC) or the AHR inhibitor CH223191 (20 μM) (AHRinhDC).

(A) Experimental design.

(B) Heatmap displaying the median percentage of positive cells expressing the indicated marker in DC-10s, AHRactDCs, DCs, and AHRactDCs at 7 days of differentiation (n = 11–25). p values by Mixed effect model with Geisser-Greenhouse correction followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test; only AHRinhDC vs. DC and AHRactDC vs. DC p values are shown, the complete list of significant p values is shown in Figure S4C.

(C) Short-term MLR of total CD4+ T cells stimulated with DC-10s, DCs, and AHRactDCs (n = 12). Percentages of proliferating (left) and CD25+HLA-DR+ activated (middle) CD4+ cells, and IFNγ production (right) in the culture supernatants of. p values by Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

(D) Short-term MLR of total (top panels) and naive (bottom panels) CD4+ T cells stimulated with DC-10s, DCs, and AHRinhDCs (n = 10). Percentages of proliferating (left) and of CD25+HLA-DR+ activated (middle) CD4+ cells; IFNγ production (right) in the culture supernatants. p values by Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

(E) DDIT4 expression by ddPCR in DCs and DC-10s expressed as ratio of DDIT4 molecules/mL to HPRT molecules/mL in arbitrary units (a.u.). p value by Wilcoxon matched pairs test (n = 11).

(F) Experimental design describing DC differentiation conditions and short-term MLR assay. Peripheral blood (PB) CD14+ monocytes were differentiated for 7 days in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 (DC), GM-CSF, IL-4, and IL-10 (DC-10) without or with AHR antagonist CH223191 (10 μM, AHRinh-loDC-10; 20 μM, AHRinhDC-10), MTOR activator MHY1485 (20 μM, MTORact-loDC-10; 50 μM, MTORactDC-10), or the combination of CH223191 (10 μM) and MHY1485 (20 μM) (AHRinh-lo/MTORact-loDC-10).

(G) Percentages of positive cells or relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) for the indicated markers in the indicated conditions gated on CD11c+ Live/Dead negative population (n = 6–12).

(H) Percentages of proliferating (left) and CD25+HLA-DR+ activated (middle) cells, and IFNγ production in the supernatant (right) of total CD4+ T cells stimulated with DC-10s, AHRinh-lo DC-10s, AHRinhDC-10s, MTORact-lo DC-10s, MTORactDC-10s, or AHRinh-lo/MTORact-lo DC-10s, relative to the results obtained with donor-matched DC-stimulated T, set at 100% (dotted line) (n = 6–15).

(I) Expression of AHR targets CYP1B1 (left) and AHRR (right) by ddPCR. Arbitrary units (a.u.) are expressed as ratio between molecules/μL of the target gene and molecules/μL of the reference HPRT gene. (G–I) Median, interquartile range and single values are displayed. (F–H) p values by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. See Figure S4.

AHR activation did not affect DC yield, while AHR inhibition significantly reduced it (Figure S4A). Despite efficient modulation of the AHR pathway, as indicated by upregulation and downregulation of CYP1B1 gene expression in ITE-treated DCs (AHRactDCs) and CH223191-treated DCs (AHRinhDCs), respectively, compared with DCs, we observed very limited phenotypic differences when comparing AHR-modulated DCs with DCs (Figures 4B, S4B, and S4C). Expression of DC-10 markers was similar (CD16, CD141, CD163, CD83, HLA-G, ILT-4) or significantly downregulated (CD14 and CD141), and DC markers (DC-SIGN, CD206, CD1a, and CD86) were mostly comparable in AHRactDCs compared with DCs. Most of the tested markers were unaffected in AHRinhDCs, while the fraction of CD1a+ and CD86+ cells was significantly lower and higher, respectively, compared with DCs (Figures 4B, S4C, and S4D).

We then tested the ability of AHR-modulated DCs to induce allogeneic T cell proliferation in a short-term MLR (Figure 4A). As expected, DC-10-primed T cells showed significantly lower proliferation, activation, and IFNγ production, compared with DC-primed T cells. Conversely, AHRactDC-primed T cells showed proliferation and activation profiles similar to that of DC-primed T cells, with a significantly higher IFNγ production (Figure 4C). Accordingly, IL-10 expression was not increased, while IL-6 expression was significantly upregulated in AHRactDCs vs. DCs (Figure S4E). These data indicate that AHR activation, in these DC differentiation conditions, is not sufficient per se to induce DCs with tolerogenic phenotype and function. AHRinhDCs showed reduced CD1a expression (see Figures 4B, S4C, and S4D), suggesting impaired DC differentiation. To test both stimulating ability of the bulk population and priming ability of fully differentiated DCs, we used both total and naive CD4+ T cells as responders in short-term MLR. Proliferation, activation, and IFNγ production of AHRinhDC-stimulated total CD4+ T cells were mildly, although significantly, increased compared with that of DC-stimulated T cells, confirming the pleiotropic functions of AHR in addition to its roles in IL-10-mediated mechanisms (Figure 4D, top panels, and Figure S4F). Conversely, AHRinhDC-primed naive CD4+ T cells showed increased activation and IFNγ production and decreased proliferation compared with DC-primed T cells (Figure 4D, bottom panels, and Figure S4F). These data confirmed that, in our differentiation conditions, AHR is needed for the differentiation of functional DCs and helps restraining a pro-inflammatory phenotype in monocytes.

IL-10 can inhibit the activity of mechanistic target of Rapamycin kinase (MTOR), which in turn can activate HIF1a, an antagonist of AHR activity.12,38,39,40 IL-10 suppression of MTOR activity is mediated by the upregulation of the MTOR inhibitor DDIT4 (also known as REDD1/RTP801).38,41 We found that DC-10s expressed significantly higher levels of DDIT4 compared with DCs (Figure 4E), suggesting that IL-10 may induce AHR-mediated tolerogenic features by inhibiting the MTOR pathway. To assess this hypothesis, we tested AHR activation, phenotype, and tolerogenic functions of DC-10s differentiated in presence of different concentrations of the MTOR activator MHY1485 (20 and 50 μM, MTORact-loDC-10s and MTORactDC-10s, respectively), as compared with DC-10s differentiated in the presence of different doses of CH223191 (10 and 20 μM, AHRinh-loDC-10s and AHRinhDC-10s, respectively) and untreated DC-10s. We also tested the effect of the two drugs combined (10 μM CH223191 + 20 μM MHY1485, AHRinh-lo/MTORact-loDC-10s) (Figure 4F). We confirmed efficient MHY1485-induced MTOR activation by assessing phosphorylation of MTOR target ribosomal protein S6 in DC-10s, MTORact-loDC-10s, and MTORactDC-10s (Figure S4G). If MTOR inhibition is needed for IL-10-mediated AHR activation, we would expect MTOR-activated DC-10s to lose tolerogenic features and AHR activation, similar to what is observed in AHRinhDC-10s. Moreover, the combination of the two drugs should show an additive effect, since used at the suboptimal doses (combination of the highest doses was toxic, data not shown). AHRinh-loDC-10s expressed DC-10 markers and CD86 at levels similar to DC-10s, while DC-10 marker loss and upregulation of CD86 was confirmed in AHRinhDC-10s. MTORactDC-10s and MTORact-loDC-10s showed a significant dose-dependent loss of DC-10 markers and upregulation of CD86, which were in the range of the changes observed in AHRinhDC-10s (Figure 4G). AHRinh-lo/MTORact-loDC-10s showed significantly decreased percentages of cells expressing CD16, CD141, and CD163 and increased expression of CD86 compared with DC-10s, to an extent that was compatible with an additive effect between the two drugs. In a short-term MLR, significant increases in proliferation, activation, and IFNγ production for AHRinhDC-10-stimulated T cells, as compared with DC-10-stimulated T cells, were confirmed (Figures 4H and S4H). Compared with DC-10-stimulated T cells, AHRinh-loDC-10-, MTORact-loDC-10-, and MTORactDC-10-stimulated T cells showed a trend toward higher proliferation, activation and IFNγ production that did not reach significance. Like AHRinhDC-10-stimulated cells, AHRinh-lo/MTORact-loDC-10-stimulated T cells displayed significantly higher proliferation, activation, and IFNγ production compared with DC-10s. Consistently, we found a tendency for a dose-dependent decrease in CYP1B1 and AHRR expression in AHR-inhibited and MTOR-activated DC-10s, while only AHRinh-lo/MTORact-loDC-10s reached significantly lower levels of AHR targets as compared with DC-10s (Figure 4I).

These data indicate that MTOR activity impacts negatively on the differentiation of DC-10s by antagonizing AHR activity and suggest that IL-10 may induce AHR activation by inhibiting the MTOR pathway.

AHR exploits IL-10-induced enhancers to establish tolerogenic signature in DCs

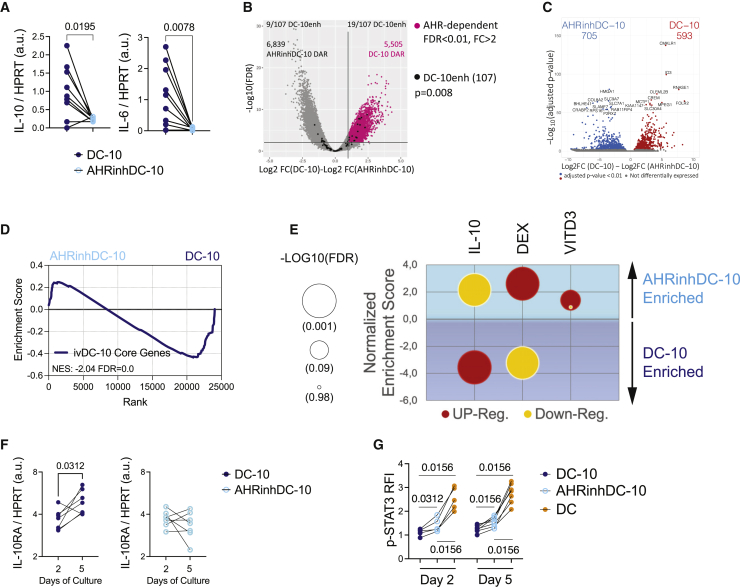

We then investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying loss of tolerogenic activities in AHRinhDC-10s. DC-10s produce high levels of IL-6 and IL-10, the latter mediating their regulatory activity.17 We found, consistent with MLR results, that AHRinhDC-10s expressed significantly lower levels of IL-10 and IL-6 genes compared with DC-10s (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

AHR activity controls IL-10-induced gene expression patterns

(A) Ratio of the indicated transcripts in molecules/μL to HPRT molecules/μL in arbitrary units (a.u.) by ddPCR in DC-10s and AHRinhDC-10s.

(B and C) Volcano plots of differentially accessible regions (DARs) by ATAC-seq (B) and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by RNA-seq (C) in DC-10s and AHRinhDC-10s.

(B) Horizontal line at p = 0.01. Vertical line at logFC = 1. Gray dots = peaks obtained from the DC-10 vs. AHRinhDC-10 analysis; black dots = 107 DC-10-specific enhancers obtained in the DC-10 vs. DC analysis (see Figure 1D), the number of DC-10-specific enhancers enriched in DC-10 and AHRinhDC-10 peaks (p < 0.05) is indicated; pink dots = peaks accessible in DC-10s and not in AHRinhDC-10s. p value by Fisher’s exact test. The number of DARs in the two conditions is indicated.

(C) Gray dots = non-differential genes; Red dots = DEGs (p < 0.01). Ten most significant DEGs in each group are indicated.

(D) GSEA of the 91 DC-10 core genes in the AHRinhDC-10 vs. DC-10 transcriptomes. Normalized enrichment score (NES) and FDR q-value are indicated.

(E) NES (y axis) and FDR q-value (dot size, expressed as -Log10) by GSEA of gene sets upregulated (red bubbles) and downregulated (yellow bubbles) in monocytes upon 24 h of IL-10 exposure (IL-10; GSE59184), in dexamethasone-induced (DEX) tolDC42 and in Vitamin D3-induced tolDC (VITD3; GSE13762), assessed in AHRinhDC-10 vs. DC-10 transcriptomes. Blue area = DC-10 enriched, light blue area = AHRinhDC-10 enriched.

(F) IL-10 receptor alpha (IL10RA) expression by ddPCR in DC-10s and AHRinhDC-10s at 2 and 5 days of in vitro differentiation expressed as the ratio of IL-10 molecules/μL to HPRT molecules/μL in arbitrary units (a.u.).

(G) Phosphorylated-STAT3 (p-STAT3) fluorescence intensity (RFI) by flow cytometry (FC) of IL-10-stimulated, relative to -unstimulated, DC-10s, AHRinhDC-10s, and DCs at days 2 and 5 of differentiation. (A, F, and G) p values by Wilcoxon matched pairs test. See Figure S5.

To assess how AHR inhibition affects IL-10-induced genomic signature in tolDC, we performed ATAC-seq and RNA-seq on AHRinhDC-10s and compared results with those obtained in DC-10s. Even if AHR inhibition severely impacted overall chromatin accessibility, with 5,505 peaks lost in AHRinhDC-10s vs. DC-10s (Figure 5B), DC-10-specific enhancer accessibility was barely reduced (p = 0.008), considering the large sample size, in AHRinhDC-10s compared with DC-10s. This indicates that DC-10-specific enhancer accessibility is not dependent on AHR activity. Interestingly, AHR-dependent peaks overlapped with annotated promoters to a significantly higher extent than DC-10-specific peaks, suggesting that AHR inhibition had major effects on promoter activity and transcription (Figure S5A). Consistently, transcriptome was profoundly altered in AHRinhDC-10s, with 705 and 593 genes downregulated and upregulated, respectively, compared with DC-10s (Figure 5C). As expected, genes downregulated in AHRinhDC-10s were strongly enriched in gene targets of TFs controlled by AHR, such as MAF and NFE2L2 (Figures S5B and S5C).

The expression of DC-10 core genes was significantly depleted in AHRinhDC-10 transcriptome, confirming that AHR activity is required for the expression of DC-10 core genes (Figure 5D). Notably, genes upregulated in AHRinhDC-10s were enriched in classes linked to inflammation (Figure S5D), leading us to investigate whether AHR activity is more broadly involved in promoting tolerogenic pathways in DCs. We found genes upregulated in monocytes upon IL-10 exposure (Table S3)42,43,44,45 significantly depleted in AHRinhDC-10s, confirming that IL-10-induced gene expression relies on AHR activity (Figure 5E). On the contrary, genes upregulated in dexamethasone (DEX)- and Vitamin D3 (VITD3)-induced tolDC (Table S3)42,43,44,45 were enriched in AHRinhDC-10 transcriptome. Of note, genes downregulated in DEX tolDCs were enriched in DC-10 transcriptome (Figure 5E). The inverse correlation between AHR inhibition and gene expression patterns associated with IL-10, but not with those associated with other types of tolDCs, supports a specific link between AHR activity and IL-10-induced pathways.

The documented transcriptional control of IL-10RA by AHR in intestinal epithelial cells46 and the effect of AHR inhibition on genes controlled by IL-10 led us to verify whether AHR inhibition prevented the ability of monocytes to sense IL-10. We assessed IL-10RA expression in AHRinhDC-10s and DC-10s at day 2 of differentiation and observed comparable levels. At day 5, DC-10s upregulated IL-10RA expression, while AHRinhDC-10s did not (Figure 5F). We tested STAT3 phosphorylation in response to IL-10 stimulation and found a significantly higher phosphorylation in AHRinhDC-10s compared with DC-10s at days 2 and 5 of differentiation (Figures 5G and S5E), indicating efficient IL-10R signaling in AHRinhDC-10s. DC-10s showed the lowest STAT3 phosphorylation compared with DCs and AHRinhDC-10s, very likely because of negative feedback mechanisms activated by the exposure to IL-10 during differentiation. These data ruled out a direct effect of AHR inhibition on IL-10 sensing during tolDC differentiation.

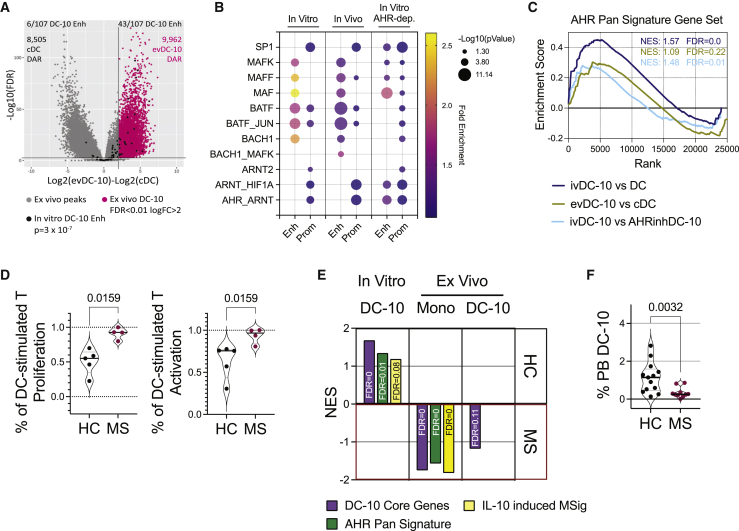

The IL-10/AHR genomic signature is active in vivo and is altered in autoimmune conditions

To determine whether the IL-10/AHR genomic signature identified in in vitro differentiated DC-10s is relevant in ex vivo isolated DC-10s (evDC-10s),17,18 we analyzed chromatin accessibility in evDC-10s and their inflammatory counterpart classical DCs (cDCs) (Figure S6A). Chromatin accessibility was markedly different between the two cell types, with around 10,000 peaks specifically accessible in evDC-10s and not in cDCs (Figure 6A). When testing the distribution of the 107 DC-10-specific enhancers identified in vitro (Figure 1D), we found them significantly enriched among evDC-10 peaks vs. cDC peaks (p = 3 × 10−7; Figure 6A), suggesting that most of the enhancers used by in vitro DC-10s are also used by DC-10s in vivo. Moreover, the 91 DC-10 core genes (Table S1 and Figure 1D) were highly significantly enriched in the transcriptome of evDC-10s vs. cDCs (Figure S6B), supporting a common chromatin signature between in vitro and ex vivo DC-10s.

Figure 6.

IL-10/AHR signature is active in vivo and is altered in autoimmune conditions

(A) DESeq2 volcano plot of ATAC peaks in evDC-10s (n = 6) and cDCs (n = 4) plotting log2(FC) and -log10 (FDR). Horizontal line at p = 0.01. Vertical line at logFC = 2. Gray dots = peaks obtained from the evDC-10 vs. cDC analysis; black dots = 107 DC-10-specific enhancers obtained in in vitro DC-10 vs. DC analysis (see Figure 1D), the number of DC-10-specific enhancers enriched in cDC and evDC-10 peaks (p < 0.05) are indicated, together with the number of differentially accessible regions (DARs); pink dots = accessible peaks in evDC-10s and not in cDCs. p value by Fisher’s exact test.

(B) Bubble plot of indicated TF binding site enrichment by TFmotifView: p value (bubble size) and fold enrichment (bubble color) over background in robust enhancer (enh) and target gene promoter (prom) sequences specific for DC-10s (in vitro) and evDC-10s (in vivo) and lost in AHRinhDC-10s (in vitro AHR dep.). p values >0.05 are not displayed.

(C) GSEA of AHR pan signature gene set in ivDC-10s vs. DCs (blue, leading-edge genes: 70 of 166), evDC-10s vs. cDCs (green, leading-edge genes; 40 of 166) and ivDC-10s vs. AHRinhDC-10s (light blue, leading-edge genes: 31 of 166) transcriptomes. Normalized enrichment score (NES) and FDR are reported.

(D) HC and MS monocytes were differentiated into DCs and DC-10s tested in short-term MLR. Left, percentage of DC-stimulated T cell proliferation expressed as % proliferating DC-10-primed CD4+/% donor-matched proliferating DC-primed CD4+; right, percentage of DC-stimulated T activation expressed as %CD25+ and/or HLA-DR+ DC-10-primed CD4+/% donor-matched CD25+ and/or HLA-DR+ DC-primed CD4+. HC: T cells stimulated by healthy monocyte-derived DC-10s; MS: T cells stimulated by multiple sclerosis-derived DC-10s. Violin plots display median, interquartile range, and single values.

(E) Normalized enrichment score (NES) by GSEA of the 91 DC-10 core (purple), AHR pan signature14 (green), and IL-10-induced molecular signature (MSigDB: GSE43700) (yellow) genes in the transcriptomes of healthy (HC) vs. multiple sclerosis (MS) in vitro differentiated DC-10s (left), monocytes (middle), and ex vivo isolated DC-10s (right). FDR is provided for each gene set. Only significantly enriched gene sets are shown. Details on gene lists used are provided in Tables S2 and S3. Number of leading genes in each group are provided in Table S6.

(F) Violin plot displaying median, interquartile range, and single values of the percentage of DC-10s (CD14+CD16+CD141+CD163+) in the PB of healthy controls (HC) and multiple sclerosis (MS) donors. (D and F) p value by Mann-Whitney test, n = 4–5 (D), n = 10–13 (F). See Figure S6.

FANTOM5 database21 intersection identified 1,105 robust enhancers among the evDC-10-specific peaks and 643 putative enhancer target genes (Table S4). Using TFmotifView,47 we investigated whether the most enriched TF binding sites in in vitro differentiated DC-10s (Figure 1F, light blue and peach clouds) were also enriched in evDC-10 enhancer and target gene promoter sequences. While BACH2 and NFE2 binding sites were not enriched in in vitro or ex vivo sequences by this analysis (not shown), all the other TF binding sites enriched in in vitro DC-10 sequences were significantly enriched also in evDC-10s (Figure 6B). MAF and AHR/ARNT binding sites were enriched in enhancers and promoters, respectively, in in vitro and ex vivo DC-10s, indicating that these TFs are relevant for DC-10 biology. Moreover, BATF binding sites were enriched in both enhancers and promoters in vitro and ex vivo, suggesting a key role for BATF, already described in Tregs upstream of AHR activation,25 in this context. Interestingly, in AHRinhDC-10s we observed enrichment of AHR/ARNT and MAF binding sites in both enhancers and promoters, while BATF binding sites were enriched in promoters only. In AHRinhDC-10s, BATF binding sites were maintained in enhancers, thus we postulated that BATF binding to the enhancer is independent, and likely upstream, of the AHR network. Accordingly, we found that BATF transcription was activated very early upon IL-10 stimulation of monocytes (Figure S6C).

We then assessed the presence of an AHR pan-tissue signature recently described14 in evDC-10 transcriptome. AHR signature was significantly enriched in both in vitro and ex vivo DC-10s, and, as expected, significantly depleted in in vitro AHRinhDC-10s (Figure 6C), further supporting a role for the AHR in in vivo DC-10s.

We finally investigated the relevance of our results for human physiology and studied DC-10s in a severe autoimmune condition, relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). We differentiated in vitro DC-10s from peripheral blood (PB) monocytes of MS patients and healthy controls (HCs). We observed significantly lower percentages of CD163+ cells in MS DC-10s compared with HCs (Figure S6D), suggesting impaired differentiation of MS DC-10s. Accordingly, MS DC-10-primed T cells had a significantly higher proliferation and activation rate compared with HC DC-10-primed T cells (Figure 6D). These data indicate that in vitro differentiated MS DC-10s are functionally defective. To test if these defects were linked to alterations in AHR-related pathways in differentiated DC-10s or their monocyte progenitors, we performed RNA-seq on MS and HC in vitro differentiated and ex vivo isolated DC-10s, and re-analyzed published RNA-seq data obtained from relapsing remitting MS and HC monocytes.48 Unsupervised analysis revealed negligible differences in the transcriptomes of MS and HC DC-10s, both in vitro and ex vivo (Figure S6E). Nevertheless, the expression of the 91 DC-10 core genes, AHR pan-tissue signature genes,14 and genes upregulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) upon IL-10 stimulation (MSigDB: GSE43700; Table S3)49 were significantly depleted in in vitro differentiated MS DC-10s compared with HC DC-10s, correlating with the functional defects observed in MS DC-10s (Figure 6E). Conversely, the three gene lists were significantly enriched in the transcriptome of ex vivo isolated MS monocytes, as compared with HC monocytes. Significant enrichment of DC-10 core genes was also observed in ex vivo DC-10s isolated from MS patients as compared with HCs, while the enrichment in IL-10-induced genes was lost in these cells (Figure 6E).

Since tryptophan metabolism, the main source of AHR ligands, and chronic activation of interleukin signaling have been associated with cellular senescence,50,51,52,53 we tested whether MS monocytes, which displayed upregulated IL-10-induced AHR-mediated pathways, showed signs of senescence in their transcriptome, which may result in reduced fitness and inability to respond efficiently to IL-10 and differentiate into DC-10s in vitro. Eight out of the 11 senescence-associated molecular signatures tested were significantly enriched in MS compared with HC monocytes by GSEA (Table S3; Figure S6F). Accordingly, the percentage of circulating DC-10s in the PB was significantly lower in MS patients as compared with HCs, even if the expression of DC-10 markers/tolerogenic molecules was not significantly different (Figures 6F and S6G). Overall, these data indicate that IL-10-induced AHR-mediated pathways are altered in MS DC-10s and DC-10 precursors and that these alterations correlate with inefficient DC-10 differentiation both in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

We investigated the molecular mechanisms induced by IL-10 during the differentiation of human tolDCs and identified that AHR activation is required for the establishment of IL-10-induced core genes and tolerogenic functions in human DCs. We report here a role for AHR downstream of IL-10 signaling in myeloid cells. Indeed, AHR-specific inhibition in DC-10s leads to loss of expression of IL-10-induced core genes, IL-10 itself, and key tolerogenic molecules (ILT-4, HLA-G, and PD-L1). The in vitro IL-10/AHR genomic signature is also present in DC-10s in vivo, suggesting a role for the identified pathways in tolDC in vivo differentiation. Underlying the relevance of the described signature for human health, DC-10s derived from MS patients’ monocytes showed significant downregulation of the expression of identified IL-10/AHR-activated core genes, correlating with severe defects in tolerogenic functions.

The combined assessment of chromatin status and transcriptome in IL-10-induced tolDCs allowed us to identify a restricted list of core genes that seems to be necessary for the function of IL-10 in these conditions. Among them, ILT-4 and IRF-1 may play key roles. Indeed, we and others have shown IL-10-dependent upregulation of ILT-4 expression mediating tolerogenic functions in monocyte-derived DCs.17,54 IRF-1 can directly control IL-10 gene expression, but its activity seems to be related to the cellular context, as it can induce both tolerogenic (in T and cancer cells) and pro-inflammatory (in T and myeloid cells) gene expression patterns.25,55,56,57,58,59 A full understanding of the role of the identified core genes requires further investigation and might allow the discovery of additional IL-10 functions.

We showed that AHR-specific inhibition in DC-10s resulted in loss of their tolerogenic functions, providing evidence for the necessity of AHR activity in IL-10-mediated induction of tolerance in myeloid cells. AHR is a ligand-induced TF deeply studied as a critical modulator of immune cell functions and immune tolerance. Because of its promiscuity both in ligand and co-factor binding, its activity is strictly dependent on the cellular context in which it acts.8,9,10 Most AHR studies have been performed in mice, where AHR can play both pro-inflammatory and tolerogenic functions in T cells, while it seems to induce tolerogenic mechanisms in DCs. In humans, AHR activation via tryptophan-derived metabolites has been shown to modulate monocyte-derived DCs.34,35 However, activating AHR during DC differentiation in absence of IL-10 did not result in acquisition of tolerogenic activities, indicating that AHR activation is not sufficient per se to induce full tolDC differentiation in our differentiation conditions, and confirming that AHR activity is strongly context dependent. This is further supported by the results obtained in AHRinhDCs, which confirmed that AHR is needed for full DC differentiation14 and restrains pro-inflammatory pathways in the monocyte/DC axis. Overall, modulation, both positive and negative, of AHR in DCs not exposed to IL-10 resulted in limited modulation of tolerogenic/pro-inflammatory phenotypes and functions as compared with results obtained by AHR modulation in DC-10s. This further supports the evidence that AHR, beyond its previously described roles in modulating immune cells, specifically acts in DCs in an IL-10-dependent manner. Several studies have demonstrated that the IL-10 gene is a primary target of AHR transcriptional activity in various immune cells, including mouse DCs.7,11,60,61 We demonstrate here that AHR functions downstream of IL-10 signaling. AHR gene transcription can be activated by STAT3, which mediates signaling of several cytokines, including IL-10, in mouse T cells.12 Nevertheless, we found that AHR transcription is significantly lower in DC-10s compared with DCs and is downregulated at early time points upon IL-10 stimulation of monocytes, suggesting that IL-10-mediated induction of AHR activity does not occur at the transcriptional level.

IL-10 is a pleiotropic cytokine exerting opposite functions depending on the target cell and the molecular mechanisms involved. Nevertheless, its key role in controlling unwanted immune responses has been clearly demonstrated.2,3 IL-10 signaling is mediated by phosphorylated STAT3, which directly activates gene transcription. STAT3 is known to cooperate with AHR to control specific cytokine gene loci in mouse T cells.62,63 Along with the canonical immune pathways activated downstream of IL-10, recent studies have demonstrated that IL-10 also impacts cell metabolism. Indeed, IL-10 can inhibit MTOR activity while increasing mitophagy and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in myeloid cells.38,64,65 IL-10-induced catabolic pathways may induce the production of AHR ligands, while MTOR inhibition may block HIF1a, an inhibitor of AHR, thereby promoting AHR activity.7,10,12,66 Both OXPHOS and MTOR pathways may play a role in IL-10-induced tolDCs. Nevertheless, our experiments showed that AHR-mediated tolerogenic features in IL-10-induced tolDCs are abrogated by MTOR activation, thus putting forth this pathway as a major player in AHR activation mediated by IL-10 in this system. OXPHOS has been associated with tolerogenic phenotypes in DCs.64 Accordingly, OXPHOS-related genes can be induced by several factors currently used to generate tolDCs in vitro, such as VITD3 and DEX.67,68 However, our data show that gene sets specifically upregulated in VITD3- and DEX-induced tolDCs are not enriched in the IL-10-induced transcriptome in DC-10s and are not dependent on AHR activity. These data indicate that, even converging on some specific key tolerogenic genes, different stimuli induce different tolerogenic pathways in monocyte-derived DCs, as previously proposed.69

Although AHR inhibition severely affected chromatin accessibility in DC-10s, likely by altering promoter activity, DC-10-specific enhancer accessibility was not lost in AHR-inhibited DC-10s, indicating that AHR does not play a primary role in establishing IL-10 chromatin signature. This role may be played by BATF, described as a key regulator of chromatin accessibility and gene expression patterns in the differentiation of mouse and human Tregs downstream of IL-27 and IL-33 signaling or OXPHOS metabolism.25,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77 We found BATF binding sites significantly enriched in DC-10 enhancers and maintained upon AHR inhibition, suggesting that BATF acts upstream of AHR. BATF expression was also upregulated at early timepoints in IL-10-stimulated monocytes. Through BATF upregulation, IL-10 may thus impact chromatin accessibility and allow activated AHR to bind key regulatory elements. A similar mechanism has been described in IL-27-induced murine Tr1 cell differentiation, where BATF activity is required to establish genomic accessible regions, gene expression patterns, and AHR binding to the IL-10 gene.25

The IL-10-induced AHR signature characterized not only in vitro differentiated, but also in vivo occurring DC-10s, suggesting a physiological role for this molecular pattern in maintaining immune tolerance. Accordingly, the IL-10/AHR signature was significantly altered in monocytes and DC-10s isolated from MS patients, and this alteration correlated with defects in function and frequencies of in vitro and in vivo DC-10s, respectively.

MS is an autoimmune disease characterized by a CD4+ T cell-triggered immune response against myelin antigens leading to severe neurodegeneration.78 A correlation between MS disease and altered AHR pathways has been proposed by studies in the mouse model and in patients’ plasma.79,80,81 We provide here evidence of defects in the tolerogenic monocyte-DC axis in MS patients. Consistent with the defects in IL-10 pathways and Tr1 cell activity observed in MS patients,82,83,84 our data show impaired ability of MS monocytes to respond to IL-10 and differentiate into functional tolDCs. Further studies are warranted to assess the molecular mechanisms (impaired expression of inhibitory molecules, secretion of cytokines or shedding of soluble CD163) underlying the observed defects and whether the observed alterations play a pathogenic role in MS development.

By identifying a molecular pattern induced by IL-10 in myeloid cells, our studies expand knowledge about the mechanisms controlling human tolerogenic immune cells. This knowledge, on one hand, improves our understanding of the molecular mechanisms controlling the maintenance of immune tolerance and, on the other hand, may help in designing therapies to re-establish it. Indeed, AHR has been already proposed as target of tolerogenic therapies, with beneficial effects already demonstrated in the mouse models of several autoimmune diseases. Upon discovery of the AHR activating and activated pathway downstream of IL-10, these could be manipulated in vivo to overcome possible defects of tolDCs in specific pathologies, and in vitro to enhance the differentiation of tolDCs for cell therapies.

Limitations of the study

We show that IL-10 imprints chromatin and transcriptome of differentiating DCs and that its tolerogenic activity is mainly mediated by AHR activation. Our study does not describe all the pathways/players activated by IL-10 and playing roles in establishing tolerogenic features in DCs. Moreover, it does not provide information on the specific molecular players acting upstream to establish the accessibility of IL-10-induced enhancers exploited by AHR, nor acting downstream of AHR and leading to the tolerogenic fate. Only further analysis of provided sequencing data and targeted experiments using our cellular model will address these issues.

By using an MTOR activator, we provide evidence for the need of MTOR inhibition to obtain IL-10/AHR-mediated tolDC differentiation and propose a direct effect of MTOR in inhibiting AHR by controlling HIF1a. Still, we cannot formally rule out an indirect contribution of autophagy to the system, as MTOR activation inevitably leads to inhibition of autophagy. Also, we have not assessed the possible contribution of endogenous AHR ligands to the AHR activating pathways established downstream of IL-10.

By using AHR agonist ITE we provide evidence that, in our differentiating conditions, AHR activation is not sufficient per se to drive tolDC differentiation. This apparent contrast with published studies describing the ability of AHR to modulate DCs is likely explained by the strong DC differentiating conditions we used in our model. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that the use of different AHR agonists, even in our differentiating conditions, will be more pro-tolerogenic than ITE, given the well-described context-specific activity of AHR agonists.

Finally, we describe a defect in the monocyte-DC axis in MS patients and link this defect to altered IL-10/AHR pathways. At this stage, we cannot assess whether the observed defects are causes or consequences of immune deregulation in these patients because the functional studies on DC-10 differentiation were performed on monocytes isolated from patients with active disease.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti human CD1a-FITC | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 555806;RRID:AB_396140 |

| Anti human CD1a-PE | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 555807;RRID:AB_396141 |

| Anti human CD1c-FITC | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-104-894;RRID:AB_2661158 |

| Anti human CD4-APC | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 345771; RRID:AB_2868799 |

| Anti human CD4-PECy7 | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 557852;RRID:AB_396897 |

| Anti human CD11c-FITC | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 561355; RRID:AB_10611872 |

| Anti human CD11c-PECy7 | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 561356;RRID:AB_10611859 |

| Anti human CD14-FITC | BD | Cat# 345784; RRID:AB_2868810 |

| Anti human CD14-PerCPCy5.5 | BioLegend | Cat# 325622; RRID:AB_893250 |

| Anti human CD14-APC-H7 | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 560180;RRID:AB_1645464 |

| Anti human CD16-Alexa647 | BD | Cat# 557710; RRID:AB_396819 |

| Anti human CD16-PB | BD | Cat# 558122;RRID:AB_397042 |

| Anti human CD16-BV510 | BD | Cat# 563830 |

| Anti human CD25-APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 340907; RRID:AB_2819021 |

| Anti human CD25-BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562442; RRID:AB_11154578 |

| Anti human CD25-PE | BD | Cat# 341011;RRID:AB_2783790 |

| Anti human CD45RA-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555488; RRID:AB_395879 |

| Anti human CD45RO-PerCPCy5.5 | BioLegend | Cat# 304221; RRID:AB_1575041 |

| Anti human CD49b-APC | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-100-396; RRID:AB_2658464 |

| Anti human CD83-BV786 | BD | Cat# 565336; RRID:AB_2739191 |

| Anti human CD83-BUV737 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612823; RRID:AB_2870147 |

| Anti human CD83-PECy7 | BD | Cat# 561132; RRID:AB_10562565 |

| Anti human CD86-PE-CF594 | BD | Cat# 562390; RRID:AB_11154047 |

| Anti human CD86-PerCPCy5.5 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561129; RRID:AB_10562395 |

| Anti human CD141-BV421 | BD | Cat# 565321; RRID:AB_2739180 |

| Anti human CD141-BV711 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563155; RRID:AB_2738033 |

| Anti human CD141-PE | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130090514;RRID:AB_244173 |

| Anti human CD163-PerCPCy5.5 | BD | Cat# 563887; RRID:AB_2738467 |

| Anti human CD163-BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562643; RRID:AB_2737697 |

| Anti human CLEC4G-APC | R&D Systems | Cat# FAB2947A |

| Anti human DC-SIGN (CD209)-PE | BD | Cat# 551265; RRID:AB_394123 |

| Anti human HLA-G-APC | EXBIO | Cat# 1A-292-C100; RRID:AB_10734198 |

| Anti human HLA-G-PE | EXBIO | Cat# 1P-437-C100; RRID:AB_10736118 |

| Anti human HLA-DR-BV510 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563083; RRID:AB_2737994 |

| Anti human HLA-DR-PE | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 555561; RRID:AB_395943 |

| Anti human ILT-4-APC | R&D Systems | Cat# FAB2078A; RRID:AB_663839 |

| Anti human LAG3-PE | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-120-470;RRID:AB_2784078 |

| Anti human PDL1-PE | eBioscience | Cat# 12-5983-42 |

| Anti human Phospho-S6 (Ser235, Ser236)-PECy7 | Thermo Scientific | Cat# 25-9007-42 |

| Anti human phosphoSTAT3 (PY705)-Alexa647 | BD Phosflow | Cat# 557815;RRID:AB_647144 |

| Purified Rat Anti-Human and Viral IL-10 (clone JES3-9D7) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 554497:RRID:AB_395433 |

| Purified Mouse Anti-Human IFNg (clone NIB42) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 551221;RRID:AB_394099 |

| Biotin Anti-Human and Viral IL-10 (clone JES3-12G8) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 554499; RRID:AB_395435 |

| Biotin Anti-Human IFNg (clone 4S.B3) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 554550; RRID:AB_395472 |

| Recombinant Human IL-10 protein | Cell Genix | Cat# 1414-050 |

| Recombinant Human IFNg | R&D Systems | Cat# 285-IF100 |

| Anti H3K27ac | Abcam | Cat# ab4729; RRID:AB_2118291 |

| Anti H3K4me1 | Abcam | Cat# ab8895; RRID:AB_306847 |

| Anti H3K9me3 | Abcam | Cat# ab8898 ;RRID:AB_306848 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| CH-223191 | Invivogen | Cat# INH-CH22 |

| ITE | Invivogen | Cat# tlrl-ite |

| MHY1485 | Calbiochem | Cat# 5005540001 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Human CD14 MicroBeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-050-201 |

| Human CD4 isolation kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-091-155 |

| Human CD45RO MicroBeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-046-001 |

| RNeasy Micro kit | Qiagen | Cat# 74034 |

| miRNeasy Micro kit | Qiagen | Cat# 217084 |

| Tagment DNA enzyme and buffer Small kit | Illumina | Cat# 20034197 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Ex vivo DC-10 and cDC RNA-seq | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-019-0218-0 | GEO: GSE117945 |

| IL-10 stimulated monocyte Microarray | https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-017-0229-5 | GEO: GSE82316 |

| MS and HC monocyte RNA-seq | https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa421 | GEO: GSE137143 |

| ATAC-seq ex vivo DC-10/DC | This paper | GEO: GSE180753 |

| ATAC-seq in vitro DC-10/DC/AHRinhDC-10 | This paper | GEO: GSE180754 |

| RNA-seq in vitro DC-10/DC/AHRinhDC-10 | This paper | GEO: GSE180761 |

| RNA-seq in vitro DC-10 MS/HC | This paper | GEO: GSE180760 |

| RNA-seq ex vivo DC-10 MS/HC | This paper | GEO: GSE180755 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| CYP1A1 FAM-Probe | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# Hs00153120 |

| IL-6 FAM-Probe | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# Hs00985639 |

| IL-10 FAM-Probe | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# Hs00174086 |

| ILT-4 (LIRB2) EvaGreen | Bio-Rad | Cat# dHSaEG5020183 |

| SOCS3 EvaGreen | Bio-Rad | Cat# dHSaEG5001979 |

| HPRT VIC-probe | Bio-Rad | Cat# 1409017 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo v10 | BD | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Prism v9 and v10 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Morpheus | Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/ |

| DESeq2 | https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| EnrichR | https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-128 | https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/) |

| Metascape | https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-128 | metascape.org |

| DiffBind | http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/DiffBind/inst/doc/DiffBind.pdf | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DiffBind.html |

| Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools (RSAT) | https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2012.088 | http://rsat.sb-roscoff.fr/ |

| TFmotifView | https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa252 | http://bardet.u-strasbg.fr/tfmotifview/ |

| String | https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1131 | https://string-db.org |

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) | https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.0506580102 | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp |

| Other | ||

| Recombinant human IL-4 | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-093-922 |

| Recombinant human GM-CSF | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-093-867 |

| Recombinant human IL-10 | Cell Genix | Cat# 1414-050 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Silvia Gregori (gregori.silvia@hsr.it).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Human subjects

Human peripheral blood was obtained from healthy donors on informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under protocols approved by the ethical committee of the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy (TIGET09, TIGET12B).

Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients were enrolled in an active state of disease and in absence of treatment (35,6 ± 9.6 years of age; 6M/6F). Healthy controls were matched to patients by sex and age (33,5 ± 8.7 years of age; 4M/9F).

Cell preparation and DC differentiation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation over Lymphoprep (CEDARLANE) and washed with PBS. Red blood cells were lysed by incubation with ammonium chloride solution and platelets were removed by low-speed centrifugation.

CD14+ monocytes were isolated from PBMCs by positive selection using CD14 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

CD14+ monocytes were differentiated into dendritic cells (DC) in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Euroclone), 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza) at 106 cells/mL, in the presence of 100 ng/mL Recombinant Human GM-CSF (Miltenyi Biotec) and 10 ng/mL Recombinant Human IL-4 (Miltenyi Biotec) for 7 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. Fresh medium with cytokines, at concentrations stated above, was added on day 3. Mature DC were obtained by adding 1 mg/mL lipopolysaccharide at day 5 of differentiation.

DC-10 were generated as previously described.17 Briefly, CD14+ monocytes were cultured as described above for DC differentiation, with the addition of Recombinant Human IL-10 (CellGenix) at 10 ng/mL.

Method details

AHR and MTOR modulation

AHR pathway modulation was performed by adding the AHR agonist 2-(1′H-indole-3′-carbonyl)-thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester (ITE) (Invivogen) (30μM) or the synthetic AHR antagonist CH-223191 (Invivogen) (20μM, unless differently indicated) to the culture medium of differentiating CD14+ monocytes at day 0 (see cell preparation and DC differentiation paragraph above). MTOR activation was performed by adding MHY1485 (Calbiochem) (20μM or 50μM, as indicated) to the culture medium of differentiating CD14+ monocytes at day 0 (see cell preparation and DC differentiation paragraph above). AHR agonist/antagonist and MTOR activator were replenished at day 3 of culturing.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay

Total CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMCs by negative selection using the human CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Naive CD4+ T cells were purified from total CD4+ T cells by negative selection with CD45RO microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Short term MLR

T cells were labeled with Cell Proliferation Dye eFluor450 (eBioscience) according to manufacturer’s instructions and stimulated with allogeneic in vitro differentiated DC/DC-10 (10:1, T:DC ratio) in X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% human serum (Sigma Aldrich) and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza). When indicated, 20 μM CH-223191 was added. Unstimulated and anti-CD3/CD28 bead (T cell activator beads, Invitrogen) stimulated CD4+ T cells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively, of proliferation. After 5 days of culture at 37°C and 5% CO2, MLR supernatants were frozen for ELISA testing and cells were collected and stained. Phenotype and proliferation dye dilution were analyzed by flow cytometry (FC).

Long term MLR and II MLR

Unstained CD4+ T cells were plated with DC/DC-10 as described for short term MLR. After 10 days, cells were counted and a fraction was stained for FC. Another fraction was stained by efluor450 proliferation dye and re-plated with mature DC (10:1, T:DC) derived from CD14+ obtained from the same donor used in long term MLR. After 3 days, MLR supernatants were frozen for ELISA testing and cells were collected and stained. Phenotype and proliferation dye dilution were analyzed by FC.

Flow cytometry (FC) analysis

Unless otherwise specified, all stainings were performed for 10 min at room temperature in the dark in BD Brilliant Buffer (Becton Dickinson).

Only single (as assessed by forward side scatter - high (FSC-H) vs FSC-area (FSC-A) plot), living (live/deadlow) cells were considered in the analysis. Data were analyzed with FlowJo Software.

Relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) for a given staining was calculated as the ratio between MFI of the stained sample and MFI of the unstained sample.

In vitro DC/DC-10 phenotype: at the end of the differentiation, dead cells were stained by blue or orange live/dead staining (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. After washing, cells were stained by cells were stained in Brilliant buffer containing fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against the following surface molecules: CD1a, CD14, CD16, HLA-DR, CD11c, CD163 (Becton Dickinson), CD141 (Miltenyi Biotec), CLEC4G (R&D Systems), CD86 (Life Technologies), CD83, HLAG (MEM-G9), ILT4 (Beckman Coulter), PDL1 (eBioscience), and CD40 (Becton Dickinson), combined according to the staining panels shown below.

| Fluorochrome | Mix 1 | Mix 2 | Mix 3 | Mix 4 | Mix 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FITC | CD1a | CD1a | CD14 | – | CD206 |

| PE | HLA-G | PDL1 | DC-SIGN | DC-SIGN | CD1A |

| PerCPCy5.5 | CD86 | CD163 | CD163 | CD14 | CD14 |

| PE-CF594 | – | – | CD86 | CD86 | CD86 |

| PE-Cy7 | CD11c | CD11c | CD11c | CD11C | CD11C |

| APC | ILT-4 | CLEG4G | HLA-G | HLAG | ILT-4 |

| APC-H7 | CD14 | CD14 | HLA-DR | HLADR | – |

| Pacific Blue/BV421 | CD163 | CD16 | CD16 | CD163 | CD163 |

| Brilliant Violet 510 | CD16 | HLA-DR | – | CD16 | CD16 |

| Brilliant Violet 711 | CD141 | CD141 | CD141 | CD141 | CD141 |

| Brilliant Violet 786 | CD83 | – | – | – | – |

| BUV737 | – | – | CD83 | CD83 | – |

Samples were analyzed by LSR Fortessa and FACSymphony Flow Cytometers (BD Biosciences).

The hierarchical clustering heatmap was obtained via Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/) by using one minus Spearman rank correlation and average as the linkage method. We used, as input parameters, the percentage of positive cells for CD14, CD16, CD141, CD163, CLEGC4-G, ILT-4, HLA-G, PD-L1, CD86, CD83, HLA-DR in 19 DC-10 and 19 DC-10 CH223191 differentiated samples.

MLR experiments: dead cells were stained with near-infrared viability dye according to manufacturer’s instructions (live/dead staining, Miltenyi Biotec). The staining mix in PBS +2% FBS contained the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: PE-Cy7 anti-CD11c, PE anti-CD25, BV510 anti-HLA-DR, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45RO and APC anti-CD4 (short term MLR). Long-term MLR cells were stained at 37°C for 15 min with PE anti-LAG3, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45RO, PE-Cy7 anti-CD4, APC anti-CD49b, BV421 anti-CD25 and BV510 anti-HLA-DR as previously described,33 followed by intra-cellular FITC anti-Ki67 staining using Fix/Perm staining buffers (eBiosciences) following manufacturer’s instructions.

II MLR cells were stained with FITC anti-CD45RA, PE anti-HLA-DR, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45RO, PE-Cy7 anti-CD4 and APC anti-CD25 in PBS +2% FBS.

Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences).

Ex vivo DC-10 staining: 180μL of whole blood were incubated with each of the following antibodies: FITC anti-CD11C, PE anti-HLA-G, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD163, PC7 anti-CD83, APC anti-ILT4, APC-H7 anti-CD14, PB anti-CD141 and BV510 anti-CD16 for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Red blood cells were then lysed by Ammonium Chloride buffer.

Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences).

STAT3 phosphorylation assay: differentiating dendritic cells were harvested at 2 and 5 days of differentiation, washed and seeded in a new plate, where they were exposed or not to IL-10 (10 ng/ml). After 30 min of incubation, cells were fixed by formaldehyde, permeabilized by methanol and stained by phospho-STAT3 antibody (PY705, BD Phosflow). For each condition, phosphorylation level is expressed as the ratio between MFI of IL-10 exposed cells and MFI of not exposed cells. Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences).

Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation assay: differentiated dendritic cells were harvested at 2 days of differentiation and seeded in a new plate, where they were exposed to IL-10 (10 ng/ml) with or without MHY1485 (20μM or 50μM). After 30 min of incubation, cells were fixed by formaldehyde, permeabilized by methanol and stained by Phospho-S6 (Ser235, Ser236) Monoclonal Antibody (cupk43k, Thermo Scientific). For each condition, phosphorylation level is expressed as the ratio between MFI of stained cells and MFI of not stained cells. Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences).

Cytokine production by ELISA

MLR supernatants were tested without dilution by standard ELISA. Below the list of reagents used.

| Coating Ab | Clone | Brand | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Rat Anti-Human and Viral IL-10 | JES3-9D7 | BD Biosciences | 1 μg/mL |

| Purified Mouse Anti-Human IFNg | NIB42 | BD Biosciences | 1 μg/mL |

| Detection Ab | Clone | Brand | Concentration |

| Biotin Anti-Human and Viral IL-10 | JES3-12G8 | BD Biosciences | 1 μg/mL |

| Biotin Anti-Human IFNg | 4S.B3 | BD Biosciences | 1 μg/mL |

| Standard Curve | Brand | Concentration (max:min) | |

| Recombinant Human IL-10 protein | – | CellGenix | 2000 : 15,625 pg/mL |

| Recombinant Human IFNg | – | R&D Systems | 2000 : 15,625 pg/mL |

Quantification of signal was performed using Streptavidin covalently coupled to horseradish peroxidase (strep-POD) and Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate, and optical density (OD) was read at 640nm on a Multiskan GO (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed by SkanIt 4.1. Absolute concentration of each cytokine was quantified by plotting sample OD on a standard curve loaded in duplicate on each plate and obtained by 2-fold serial dilutions.

Cell sorting

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells or monocyte-enriched mononuclear cells (obtained as described in18) were sorted on a FACSAria Fusion Cell Sorter after staining with:

FITC anti-CD1c, PE anti-CD141, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD14, PE-Cy7 anti-CD11c and Alexa 647 anti-CD16 (for evDC-10/cDC isolation used for ATAC-seq; see Figure S6 for gating strategy); Zombie Green, PE anti-CD141, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD14, PE-Cy7 anti-CD11c and Alexa 647 anti-CD16 (for isolation of DC-10 and monocytes from HC/MS donors).

Cells were collected in a cold block under sterile conditions.

Gene expression analysis by droplet digital PCR (dd-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using Fluorometer Qubit with Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher).

cDNA was synthesized by High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and 1-2ng of RNA equivalent were run per well of ddPCR. Amplification of target genes was performed using either QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) and specific primers designed for test targets and house-keeping control (HPRT), or with purchased probe-based systems and ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad). Below the list and sequences of home designed primers.

| Target gene | Chemistry | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHRR | EvaGreen | GACATGAAGCTGCAAGGTG | TGGACACATCTAGCAGCAG |

| CYP1B1 | EvaGreen | AAGACAGTGGAGATGAGGG | CTGTCATCTGTGAGTGTGG |

| HPRT | EvaGreen | CAAAGATGGTCAAGGTCGC | CAAATCCAACAAAGTCTGGCT |

| IRF1 | EvaGreen | CTCTGAAGCTACAACAGATGAG | GTAGACTCAGCCCAATATCCC |

| DDIT4 | EvaGreen | TTAGCAGTTCTCGCTGACC | CTAGGCATGGTGAGGACAG |

Purchased system are provided in the key resources table.

Droplets were generated by a QX200 Droplet Generator (Bio-Rad) and transferred into a 96-well plate for PCR amplification. PCR amplification was performed on a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) and fluorescence was read by QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad). Data were analyzed by QuantaSoft software (Biorad). Expression of a test gene was quantified by normalizing the number of positive droplets per μl of the test gene divided by the number of positive droplets per μl of HPRT in the same sample.

RNA-seq and microarray

RNA was extracted with an miRNeasy Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. After QC by Qubit (ThermoFisher) and TapeStation (Agilent), libraries based on rRNA depletion or polyA-selection (only for MS samples) were built and sequenced by 2x150 Illumina HiSeq 2000 or NovaSeq 6000.

Raw RNA sequences were aligned against the human reference genome GRChg19 using STAR (v 2.7.5a). FeatureCounts (v. 2.0.1) was used to determine the total counts of transcripts per gene. Differential gene expression and clustering were performed in the R statistical environment using the DESeq2 package. Gene set enrichment analyses were performed by Enrichr (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/)85 and Metascape (metascape.org)86 by using default settings and DEG (adjusted p < 0.01) genes as input lists.

We have previously published RNA-seq of ex vivo DC-10 and cDC (GSE117945).18 We have used a published microarray dataset of IL-10 stimulated and unstimulated monocytes (GSE82316)87 and re-analyzed published RNA-seq data from MS and HC monocytes (GSE137143), using only CD14+_RRMS and CD14+_Healthy samples.

ATAC-seq

Library preparation was performed on 0.5-1x105 cells by Tagment DNA enzyme and buffer Small kit (Illumina), as previously described,88 with minor modifications, and sequenced by 2x150 Illumina HiSeq.

Paired-end FASTQ reads were trimmed with trimmomatic (v 0.36) using the Nextera adapter library. Trimmed reads were then mapped on the hg19 version of the human genome using bwa-mem with default settings and duplicates were marked using samblaster (v 0.1.21). Duplicates, blacklisted regions (ENCODE) and reads aligning with mitochondrial DNA were removed using samtools (v 0.1.19). Broad peaks were called using MACS2 (v. 2.1.1; --shift −100 --extsize 200 --broad). The list of called peaks from each sample was used to assess the differentially open chromatin regions through the DiffBind package from the R statistical environment using edgeR and DESeq2 methods (FDR<0.01 and FC > 2 for in vitro data, FC > 4 for ex vivo data, where fold change values were larger). Matching results obtained by the two methods were used to define the list of differentially accessible regions that were in common across both DC-10 and DC. In case of groups with less than 3 samples (AHRinhDC-10 experiment) or more than 3 samples (ex vivo DC-10 experiment), only EdgeR or DESeq2 results were considered, respectively.

ChIP-seq

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed on 2–4 million cells, as previously described,89 by using rabbit polyclonal anti-H3K27ac, H3K4me1 and H3K9me3 antibodies (all from Abcam).

Paired-end FASTQ reads were trimmed with trimmomatic (v 0.36) using the Nextera adapter library. Trimmed reads were then mapped on the hg19 version of the human genome using bwa-mem with default settings and duplicates were marked using samblaster (v 0.1.21). Duplicates, blacklisted regions (ENCODE) and reads aligning with mitochondrial DNA were removed using samtools (v 0.1.19). Broad peaks were called using MACS2 (v. 2.1.1; --shift −100 --extsize 200 --broad).

Enhancer identification and annotation

In order to identify accessible robust enhancers, the list of differentially accessible regions was filtered using the list of human ‘robust’ enhancers from the FANTOM5 project (http://slidebase.binf.ku.dk/human_enhancers/presets - section 1), and the Enhancer - Promoter association matrix made for decomposition-based peak identification clusters (http://slidebase.binf.ku.dk/human_enhancers/presets - section 5) was used to infer the putative target genes of the previously identified enhancers.

To test whether the in vitro identified DC-10-specific robust enhancers tend to be AHR-dependent in vitro and ex vivo DC-10-specific, we performed Fisher’s exact test (FDR<0.01) on 2 x 2 tables, organized as follows:

For AHR dependency (Figure 5B).

| # DC-10 robust enhancers in DC-10 peaks (log2FC > 0 in volcano) | # DC-10 robust enhancers in AHRinhDC-10 peaks (log2FC < 0 in volcano) |