Abstract

Introduction

The current gold standard treatment for breast cancer liver metastases (BCLM) is systemic chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy. Nonetheless, greater consideration has been given to local therapeutic strategies in recent years. We sought to compare survival outcomes for available systemic and local treatments for BCLM, specifically surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation.

Methods

A review of the PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase and Cochrane Library databases was conducted. Data from included studies were extracted and subjected to time-to-event data synthesis, algorithmically reconstructing individual patient-level data from published Kaplan–Meier survival curves.

Findings

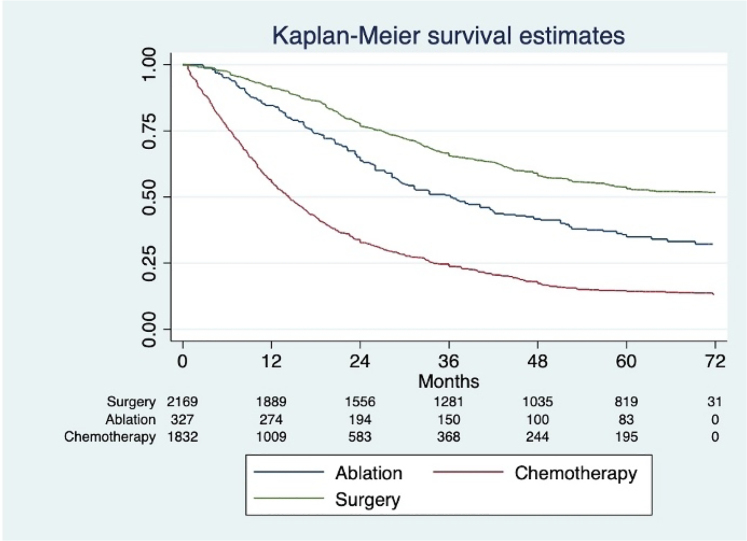

A total of 54 studies were included, comprising data for 5,430 patients (surgery, n=2,063; ablation, n=305; chemotherapy, n=3,062). Analysis of the reconstructed data demonstrated survival rates at 1, 3 and 5 years of 90%, 65.9% and 53%, respectively, for the surgical group, 83%, 49% and 35% for the ablation group and 53%, 24% and 14% for the chemotherapy group (p<0.0001).

Conclusion

Local therapeutic interventions such as liver resection and radiofrequency ablation are effective treatments for BCLM, particularly in patients with metastatic disease localised to the liver. Although the data from this review support surgical resection for BCLM, further prospective studies for managing oligometastatic breast cancer disease are required.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Liver metastases, Hepatic resection, Radiofrequency ablation, Systemic therapy

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women, with 1.67 million cases and 522,000 deaths estimated in 2012.1 Approximately 25–40% of these cases will eventually develop metastases; the majority of metastases will be multi-site, and include the liver.2 Approximately 5% of patients with metastatic disease will present exclusively with breast cancer liver metastases (BCLM).3 A pathophysiological mechanism of liver metastases has been proposed by Ma et al,4 including consecutive steps as follows: intravasation, circulation, margination, extravasation and colonisation.

Patients with BCLM have reported a median survival of 3–6 months from the diagnosis of metastases if left untreated.5 The current gold standard treatment for BCLM with or without extrahepatic disease is systemic chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy, depending on tumour hormone receptor status, and is associated with a median survival time ranging from 19 to 26 months.3

In colorectal cancer, local treatment in the form of liver resection, combined with systematic chemotherapy, has produced significant improvement in overall survival (OS) for patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases and is now recognised as the standard of treatment for this cohort of patients.6 Local therapeutic strategies for liver tumours have been available for years, such as liver resection, microwave/radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolisation, selective internal radiation therapy, stereotactic body radiation therapy and irreversible electroporation. These locoregional therapies have gained increasing consideration in the treatment of BCLM in recent years and many studies conducted in highly selected patients have been published on the matter. Nevertheless, there are no prospective randomised controlled trials comparing all the available local therapies for BCLM7 and, as such, high-level data are scarce.

We sought to compare the outcomes in terms of survival of the available systemic and local treatments for metastatic breast cancer to the liver, reviewing the available literature and pooling the data extracted from each single series. We investigated local resection, radiofrequency ablation and a systemic therapy approach (including chemotherapy and hormonal therapy).

Methods

This review followed PRISM guidelines (Figure 1).8

Figure 1 .

Flow chart of study selection

Research strategy

A systematic literature research was conducted in the PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase and the Cochrane Library databases by two independent researchers (KR and LL). The following search terms were used: (1) breast cancer AND (liver metastasis OR liver metastases) AND (liver resection OR hepatectomy OR partial hepatectomy OR surgical treatment); (2) breast cancer AND (liver metastasis OR liver metastases) AND (microwave frequency ablation OR radiofrequency ablation OR ablation OR locoregional therapy); (3) ((chemotherapy[Title/Abstract] OR hormonal[Title/Abstract]) AND breast cancer[Title/Abstract]) AND ((liver metastasis[Title/Abstract]) OR liver metastases[Title/Abstract]). We also extended the research to the list found on each reviewed paper with inclusion of any relevant studies. Suitable studies published up to 7 July 2020 were included.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All articles with published survival (Kaplan–Meier) curves for survival following surgical, chemotherapy/hormonal or radiofrequency ablation treatment for BCLM were included. When studies from the same institution presented accumulating data published multiple times, we selected the most recent and complete reports. To extract patient-level data, studies reporting patient-level data or including Kaplan–Meier curves for survival were included. Abstracts without published manuscripts, case reports, editorials and expert opinions were excluded, as were non-English language articles and studies with fewer than ten patients. When studies compared locoregional treatments for liver metastases from different types of tumour we selected the specific Kaplan–Meier curve for survival for BCLM.

The research and the data extraction were conducted by two independent investigators (KR and LL), data were reviewed and discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus.

The outcome of interest of this review was long-term survival at 1, 3 and 5 years. When more than one Kaplan–Meier curve for survival was reported in the study, eg comparing two different chemotherapeutic treatments, we considered the curves individually and we extracted data from both.

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Our review strategy was a time-to-event data synthesis, based on the method described by Guyot et al9 to reconstruct individual patient data from published Kaplan–Meier survival curves, using a newly developed algorithm that assumes constant censoring. We digitised the Kaplan–Meier curves data using the software Plot Digitiser v.2.6.8.0 and we entered the numbers obtained into the algorithm, using R statistical software. We then aggregated the reconstructed individual patient survival data to create a combined survival curve, comparing the long-term outcomes of the three therapeutic strategies analysed, using Stata (v.16; StataCorp).

Statistical analysis of the data is presented in supplementary Tables S1–S3 (including age, median follow-up) and in Tables 1–6 (including presence of single metastases, synchronous metastases, hormone receptors, extrahepatic disease, R0 resection for the surgical group and complete ablation for the ablation group, additional treatment of primary tumour and neoadjuvant treatment in the surgical group). The statistical analysis was conducted only on the studies in which the data were available, therefore the mean values and percentages presented refer only to the studies in which the data were included.

Table 1 .

Breast cancer liver metastases status for surgical group

| Study | Total no. of patients | Single metastases (%) | Synchronous metastases (%) | Mean age at hepatectomy ± sd | Resection margins | Receptor status | Extrahepatic disease (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 | R1/2 | ER+ | PR+ | HER+ | ||||||

| Chun10 | 136 | – | 56 (41) | – | – | – | 88 (65) | 51 (38) | 47 (36) | 31 (23) |

| Feng11 | 65 | 42 (65) | – | 51±11 | 62 (95) | 3 (5) | – | – | 32 (49) | 50 (77) |

| He12 | 67 | 43 (64) | 1 (1) | 51±11 | 64 (96) | 3 (4) | – | – | 14 (21) | 14 (21) |

| Lucidi13 | 72 | 33 (46) | 21 (29) | – | – | – | 57(79) | 45(63) | 32(40) | 21 (29) |

| Sundén14 | 29 | 19 (66) | – | 54 | 17 (59) | 6 (21) | 13 (59) | 9 (45) | 9 (45) | – |

| Cheung15 | 21 | – | – | 45 | 21 (100) | – | 11 (52) | 8 (38) | 5 (24) | – |

| Bacalbasa16 | 67 | 33 (49) | 54 (81) | – | 62 (93) | 5 (7) | 31(46) | 30(45) | 1(1) | – |

| Labgaa17 | 59 | 31 (62) | 6 (11) | 58 | 36 (71) | 15 (30) | – | – | – | 24 (41) |

| Ruiz18 | 139 | – | 11 (8) | – | 77 (55) | 51 (37) | 74 (53) | 40 (29) | 35(25) | 67 (48) |

| Ruiz19 | 139 | 56 (41) | – | 49±11 | – | – | 55 (82) | 41 (65) | 17 (34) | – |

| Abbas20 | 23 | 15 (65) | 8 (35) | 54 | 16 (73) | – | 17 (94) | 9 (50) | 5 (28) | 4 (17) |

| Ruiz21 | 139 | 56 (40) | 11 (8) | 51±11 | 77 (55) | 51 (37) | 74 (53) | 39 (28) | 35 (25) | 41 (29) |

| Margonis22 | 131 | – | – | 54±14 | 108 (90) | 11 (10) | 66 (73) | 53 (59) | 54 (54) | 15 (13) |

| Sadot23 | 69 | 44 (64) | 7 (10) | 51±11 | 43 (84) | – | 42 (78) | 32 (59) | 29 (45) | – |

| Bacalbasa24 | 43 | 24 (56) | 4 (9) | 53±11 | 39 (91) | 4 (91) | 22 (82) | 22 (82) | 27 (62) | – |

| Sabol25 | 15 | 9 (60) | 1 (6) | 49±9 | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (53) | 6 (40) | 4 (26) | 3 (20) |

| Kim26 | 13 | 7 (54) | 2 (15) | 51±9 | – | – | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 5 (38) | 6 (46) |

| Mariani27 | 100 | 65 (65) | 7 (7) | 50±7 | 82 (82) | 18 (18) | – | – | 12 (12) | 22 (22) |

| Kostov28 | 42 | 22 (52) | – | – | 35 (83) | 7 (17) | 19 (45) | 4 (9) | 9 (21) | 20 (47) |

| Dittmar29 | 34 | 12 (35) | 6 (17) | – | 21 (61) | 13 (39) | – | – | 22 (64) | 12 (35) |

| Polistina30 | 12 | 12 (100) | – | 60±10 | 11 (91) | 1 (9) | 9 (75) | 5 (41) | – | – |

| van Walsum31 | 32 | 22 (68) | 6 (18) | 50±6 | 29 (90) | 3 (10) | 20 (62) | – | 8 (25) | 28 (87) |

| Groeschl32 | 115 | – | 24 (20) | – | 92 (80) | 23 (20) | – | – | – | – |

| Abbott33 | 86 | 53 (62) | 25 (29) | – | 77 (90) | 9 (10) | 59 (69) | 59 (69) | 32 (37) | 24 (27) |

| Duan34 | 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rubino35 | 18 | 10 (55) | 1 (5) | 46±7 | 18 (100) | 0 (0) | 12 (66) | 12 (66) | 4 (22) | 0 (0) |

| Hoffmann36 | 41 | 20 (49) | 4 (10) | – | 32 (78) | 9 (22) | 18 (44) | 14 (34) | 11 (26) | 12 (30) |

| Caralt37 | 12 | – | 2 (16) | 57±11 | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | 9 (75) | – | 1 (8) |

| Lubrano38 | 16 | 12 (75) | 0 (0) | 53±7 | 16 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (83) | 8 (66) | – | 0 (0) |

| Thelen39 | 39 | 20 (51) | 6 (15) | – | 28 (72) | 11 (28) | 26 (66) | 19 (48) | 14 (35) | 13 (33) |

| Adam40 | 85 | 32 (37) | 9 (11) | 47±8 | 56 (66) | 29 (34) | 44 (51) | 21 (24) | 24 (28) | 27 (31) |

| Sakamoto41 | 34 | 19 (56) | 4 (11) | 51±8 | – | – | 17 (50) | – | – | 9 (26) |

| Vlastos42 | 31 | 20 (64) | 9 (29) | 46±7 | – | – | 18 (53) | 11 (35) | – | 0 (0) |

| Elias43 | 54 | – | 12 (22) | 49±5 | 44 (81) | 10 (19) | 32 (59) | 32 (59) | – | 0 (0) |

| Selzner44 | 17 | 12 (71) | – | 49±12 | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | – | – | 3 (17) |

| Pocard45 | 52 | 36 (69) | – | 47±9 | 51 (98) | 1 (2) | 19 (67) | – | – | 11 (23) |

Table 6 .

Breast cancer liver metastases additional treatments for chemotherapy group

| Study | Total no. of patients | Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant targeted therapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant radiotherapy for breast primary (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chun10 | 763 | – | – | – | – |

| Lu54 | 54 | – | – | – | – |

| Sundén14 | 33 | – | – | – | – |

| Aarts55 | 176 | – | – | – | – |

| Ruiz19 | 523 | 281 (54) | 248 (48) | 46 (9) | – |

| Abbas20 | 27 | 14 (61) | 17 (74) | 4 (17) | – |

| Sadot23 | 98 | 39 (60) | 43 (61) | 30 (31) | 37 (53) |

| Er56 | 132 | 34 (26) | 35 (27) | – | 59 (45) |

| Pentheroudakis57 | 500 | 265 (53) | – | – | – |

| Eichbaum58 | 301 | – | – | – | – |

| Li59 | 20 | 20 (100) | – | – | 9 (45) |

| Nabholtz60 | 392 | 74 (19) | 74 (19) | – | – |

| Hoe61 | 44 | – | – | – | – |

BCLM = breast cancer liver metastases

Findings

Included studies

A total of 2,403 papers were identified using this research strategy and 387 abstracts were evaluated. Of these, 241 relevant full-text articles were identified and assessed. After applying all the remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria, 54 papers were selected for final data synthesis (Figure 1). Thirty-six papers were categorised into surgical treatment, 10 papers ablation and 13 chemotherapy/hormonal therapies. Among these papers, one study compared surgical treatment, chemotherapy and ablation therapy and was included in all three categories,20 four studies10,14,19,23 comparing surgical and chemotherapy treatments were included in both categories, as was one study comparing surgical and ablation therapy.30

Surgical group

In the surgical group (n=2,063), the mean (± sd) age of the patients from papers that reported participant age was 50.40±10.40 years. Median follow-up in the included studies was 47.48 months (supplementary Table S1).

Single metastases were presented in 54.13% of the cases and synchronous metastases in 19.30%. Hormone receptors were categorised as: oestrogen receptor (ER; positive in 54.76% of cases), progesterone receptor (PR; positive in 41.17% of cases) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2; positive in 29.60% of cases).

Extrahepatic disease was present in 29.51% of the cases, and a microscopically margin-negative resection (R0 resection) was achieved in 78.10% of cases (Table 1).

Regarding systemic treatment, adjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer was used in 56.30% of the cases, adjuvant hormone therapy in 39.06%, adjuvant targeted therapy in 11.04% and adjuvant radiotherapy in 59.59%. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for BCLM was used in 67.80% of the cases, neoadjuvant hormone therapy in 53.01% and neoadjuvant targeted therapy in 25.93% (Table 2).

Table 2 .

Breast cancer liver metastases additional treatment for surgical group

| Study | Total no. of patients | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for BCLM (%) | Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy for BCLM (%) | Neoadjuvant targeted therapy for BCLM (%) | Adjuvant systemic therapy non-specified for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant targeted therapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant radiotherapy for breast primary (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chun10 | 136 | 93 (68) | – | 43 (32) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Feng11 | 65 | – | – | – | – | 54 (88) | 42 (65) | 6 (9) | 40 (62) |

| He12 | 67 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lucidi13 | 72 | 60 (83) | 63 (88) | 24 (33) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sundén14 | 29 | – | – | – | 29 (100) | – | – | – | – |

| Cheung15 | 21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bacalbasa16 | 67 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Labgaa17 | 59 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ruiz18 | 139 | 98 (71) | – | – | – | 58 (42) | 47 (34) | – | 94 (68) |

| Ruiz19 | 139 | – | – | – | – | 81 (58) | 47 (34) | 9 (7) | – |

| Abbas20 | 23 | – | – | – | – | 11 (48) | 16 (73) | 6 (27) | – |

| Ruiz21 | 139 | – | – | – | – | 81 (58) | 47 (34) | 9 (6) | 72 (52) |

| Margonis22 | 131 | 39 (75) | 51 (49) | 35 (40) | – | 41 (51) | 43 (47) | 21 (27) | – |

| Sadot23 | 69 | – | – | – | – | 52 (81) | 31 (51) | 11 (16) | 44 (68) |

| Bacalbasa24 | 43 | – | – | – | – | 41 (96) | – | – | – |

| Sabol25 | 15 | 5 (26) | – | – | 15 (100) | – | – | – | – |

| Kim26 | 13 | 2 (15) | – | – | 13 (100) | – | – | – | – |

| Mariani27 | 100 | 79 (79) | 91 (91) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kostov28 | 42 | 42 (100) | 23 (54) | 9 (21) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dittmar29 | 34 | 19 (38) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Polistina30 | 12 | 11 (91) | 10 (8) | 9 (75) | – | – | – | – | – |

| van Walsum31 | 32 | 13 (40) | 5 (15) | 2 (6) | – | 19 (59) | 17 (53) | 4 (12) | 22 (68) |

| Groeschl32 | 115 | 100 (86) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Abbott33 | 86 | 65 (76) | – | 24 (75) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Duan34 | 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rubino35 | 18 | 4 (22) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hoffmann36 | 41 | 14 (34) | 2 (4) | – | – | 24 (58) | 12 (29) | – | 17 (41) |

| Caralt37 | 12 | 6 (50) | – | – | 12 (100) | – | – | – | – |

| Lubrano38 | 16 | 16 (100) | 12 (75) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Thelen39 | 39 | – | – | – | 39 (100) | – | – | – | – |

| Adam40 | 85 | 71 (83) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sakamoto41 | 34 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Vlastos42 | 31 | – | – | – | – | 25 (81) | 14 (52) | – | – |

| Elias43 | 54 | 52 (96) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Selzner44 | 17 | 10 (59) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pocard45 | 52 | 29 (56) | 7 (19) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

BCLM = breast cancer liver metastases

Ablation group

In total 305 cases were included. The mean (± sd) age of the patients from the papers that reported participant age 51.60±10.01 years. Median follow-up in the included studies was 27.71 months (supplementary Table S2)

Single metastases were found in 54.91% of the cases and synchronous metastases in 20.66%. A complete ablation was accomplished in the 93.90% of the metastases. They were found to be ER-positive in 52.82% of cases, PR-positive in 43.08% and HER-positive in 28.32%. Extrahepatic disease was found in 49.44% of cases (Table 3).

Table 3 .

Breast cancer liver metastases status for ablation group

| Study | Total no. of patients | Single metastases (%) | Synchronous metastases (%) | Mean age at hepatectomy ± sd | Total no. of metastases | Complete ablation (on total no. of metastases) | Incomplete ablation (on total no. of metastases) | Receptor status (%) | Extrahepatic disease (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER + | PR + | HER + | |||||||||

| Bai46 | 69 | 35 (51) | 3 (4) | 50.3±10 | 135 | 125 (93) | 10 (7) | 43(62) | 37 (54) | 22 (32) | 32 (46) |

| Onal47 | 22 | 19 (86) | 3 (14) | – | 29 | – | – | 17 (77) | 13 (59) | – | 15 (48) |

| Abbas20 | 11 | 5 (45) | 3 (27) | 54 | – | – | – | 5 (63) | 2 (25) | 1 (14) | 4 (36) |

| Veltri48 | 45 | 27 (60) | 6 (13) | 45±8 | 87 | 78 (90) | 9 (10) | – | – | – | 18 (40) |

| Taşçi49 | 24 | – | – | 50±2 | 57 | – | – | 6 (25) | 4 (16) | 6 (25) | – |

| Polistina30 | 14 | 1 (7) | – | 56±13 | 54 | 51 (94) | 3 (6) | 11 (78) | 8 (57) | 3 (21) | – |

| Carrafiello50 | 13 | 8 (61) | – | 54±13 | 21 | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | – | – | – | 8 (61) |

| Meloni51 | 52 | – | 8 (15) | 55±14 | 87 | 83 (95) | 4 (5) | – | – | – | 27 (52) |

| Jakobs52 | 43 | – | 27 (32) | 57±8 | 111 | 107 (96) | 4 (4) | 18 (42) | 18 (42) | 11 (25) | 18 (42) |

| Sofocleous53 | 12 | – | – | 55±7 | 14 | 13 (92) | 1 (8) | 3 (25) | 2 (16) | 6 (50) | 10 (83) |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for BCLM was used in 77.56% of cases and hormonal therapy in 32.67% (Table 4).

Table 4 .

Breast cancer liver metastases additional treatment for ablation group

| Study | Total no. of patients | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for BCLM (%) | Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy for BCLM (%) | Neoadjuvant targeted therapy for BCLM (%) | Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant targeted therapy for breast primary (%) | Adjuvant radiotherapy for breast primary (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai46 | 69 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Onal47 | 22 | 19 (86) | 3 (14) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Abbas20 | 11 | – | – | – | 5 (45) | 5 (45) | 1 (9) | – |

| Veltri48 | 45 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Taşçi49 | 24 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Polistina30 | 14 | 14 (100) | 13 (92) | – | 9 (64) | 11 (78) | – | 11 (78) |

| Carrafiello50 | 13 | 7 (53) | 7 (53) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Meloni51 | 52 | 40 (77) | 10 (19) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jakobs52 | 43 | 39 (90) | – | 11 (25) | – | 19 (44) | – | – |

| Sofocleous53 | 12 | 2 (16) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

BCLM = breast cancer liver metastases

Chemotherapy group

In total, 3,062 patients were in this group. Mean age (± sd) from the papers that reported participant age was 51.43±10.20 years. Median follow-up in the included studies was 41.28 months (supplementary Table S3).

Single metastases were found in 12.87% of cases. Hormone receptor status was as follows: ER-positive in 56.90% of cases, PR-positive in 47.45% and HER-positive in 27.57%. Extrahepatic disease was present in 74.03% of the cases (Table 5).

Table 5 .

BCLM status for chemotherapy group

| Study | Total no. of patients | Single metastases (%) | Synchronous metastases (%) | Mean age at hepatectomy ± sd | Receptor status | Extrahepatic disease (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER+ | PR+ | HER+ | ||||||

| Chun10 | 763 | – | 248 (33) | – | 454 (60) | 341 (45) | 242 (32) | – |

| Lu54 | 54 | – | – | – | 115 (62) | 106 (57) | 44 (24) | – |

| Sundén14 | 33 | 23 (70) | – | 54 | 13 (59) | 9 (45) | 9 (45) | – |

| Aarts55 | 176 | – | 32 (18) | – | 135 (80) | 111 (66) | 29 (19) | 129 (73) |

| Ruiz19 | 523 | 13 (13.8) | – | 49±11 | 182 (63) | 122 (43) | 97 (35) | – |

| Abbas20 | 27 | 3 (11) | 4 (15) | 54 | 12 (80) | 4 (27) | 5 (33) | 17 (63) |

| Sadot23 | 98 | 29 (30) | 28 (29) | 47±3 | 55 (59) | 46 (50) | 28 (34) | – |

| Er56 | 132 | – | 13 (10) | 54±8 | 39 (29) | 23 (17) | – | – |

| Pentheroudakis57 | 500 | – | – | 54±9 | 270 (54) | 270 (54) | – | 385 (77) |

| Eichbaum58 | 301 | 56 (16) | – | 50±11 | 204 (68) | 207 (69) | – | 199 (57) |

| Li59 | 20 | 5 (25) | – | 55±12 | – | – | – | – |

| Nabholtz60 | 392 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 305 (78) |

| Hoe61 | 44 | – | – | 58±10 | 14 (70) | 6 (30) | – | 11 (25) |

BCLM = breast cancer liver metastases

Adjuvant chemotherapy was used for primary breast cancer in 42.97% of the cases, hormonal therapy in 35.58% and radiotherapy in 42.00% (Table 6).

Survival outcome

Individual patient survival data were reconstructed using the algorithm published by Guyot et al9 for a total of 2,063 patients in the surgical group, 305 in the ablation group and 3,062 in the chemotherapy group.

In the overall population, pooled data showed a significant improvement in survival with surgery compared with systemic chemotherapy (risk ratio (RR) 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 0.94; p<0.001) (Figure 3). Analysis of the reconstructed data demonstrated survival rates at 1, 3 and 5 years of 90% (95% CI 89.2–92), 65.9% (95% CI 63–67) and 53% (95% CI 51–56), respectively, for the surgical group. This is significantly higher than survival rates for the ablation group of 83% (95% CI 78–87), 49% (95% CI 43–55) and 35% (95% CI 29–41) (p<0.003, log rank test) and higher than for the systemic therapy group which had survival rates of 53% (95% CI 50–55.1), 24% (95% CI 22–26) and 14% (95% CI 12.5–16) (p<0.001, log rank test) (Figures 2 and 3). Overall comparison p<0.001, log rank test.

Figure 3 .

Forest plot comparing outcomes for surgery and chemotherapy in breast cancer liver metastases

Figure 2 .

Combined Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival at 72 months, comparing surgical, ablation and chemotherapy groups

Restricted mean survival was 51 months (95% CI 48–53) for the surgery group, 36 months for the ablation group (95% CI 29.3–42.1) and 14.3 months for the chemotherapy group (95% CI 13.5–15.5). The risk of publication bias was visually assessed as low (supplementary Figure S1), with no significant bias risk as measured by Egger’s test (p>0.05).

Discussion

Distant metastatic disease affects 25–40% of patients diagnosed with breast cancer, and 15% of them develop liver metastases with or without other sites.2 Whereas patients with metastatic breast cancer were traditionally considered candidates for palliative chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy only, with very poor survival,62 this meta-analysis suggests that the use of local disease control in the form of surgical resection or tumour ablation may contribute to significantly improved survival outcomes in appropriately selected populations of oligometastatic disease confined to the liver.

The benefits of localised treatment of liver metastases is well established in other populations such as colorectal and neuroendocrine liver metastases. Liver resection is increasingly becoming the standard of care for patients with colorectal liver metastases, reaching 5-year survivals of >40%.63 Retrospective studies have reported a 5-year survival of 60–80% for curative resection of liver metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms, compared with 30% of patients with unresected metastases.64

Interestingly, since updating our meta-analysis, there continues to be increasing evidence in the literature of satisfactory long-term results after liver resection. Feng et al11 reported a mean OS and 1, 3 and 5-year OS rates of 61.8 months, 92.6%, 54.7% and 54.7%, respectively, for hepatic resection compared with no resection (38.6 months, 79.2%, 45.6% and 21.9%; p<0.007). Lucidi et al also suggest good oncological outcomes with surgical intervention with a median OS of 50 months.13

To date, the role of local therapy in BCLM has been less well accepted, in part due to the presumed pathophysiological mechanism of metastatic spread. Liver involvement in colorectal tumours is thought to occur via the portal circulation, resulting in a majority of patients with metastatic disease that may be limited to the liver. By contrast metastatic involvement of the liver in the setting of breast cancer implies a systemic spread, with reduced survival rates of this population even if undergoing local therapies. As expected, the highest percentage of patients with extrahepatic disease were individuals in the chemotherapy and radiofrequency ablation group, because often patients without isolated liver metastases are offered less-invasive non-surgical treatment. Although little information is included in the radiofrequency ablation studies about the type of extrahepatic disease or how this was treated, it was associated with reduced survival, which may account for some of the differences noted on the OS between groups.13,40 However, radiofrequency ablation can be used successfully in extrahepatic disease as long as stable.45 A worse OS in some of the papers included in the chemotherapy group, when compared with the surgery and radiofrequency ablation groups, may be due to the high percentage of patients included with extrahepatic disease, although other independent baseline predictors may also account for this, such as higher liver tumour burden.49

Local treatments have also been trialled for breast cancer lung metastases; the International Registry of Lung Metastases database reports a median survival of 37 months after complete metastases resection, compared with 25 months after incomplete resection. Advantageous outcomes, considering the reported median survivals are 13 to 25 months after chemotherapy and hormonal therapy of isolated lung metastases in the few cited observational studies.65

In this review, we sought to compare three different strategies available for BCLM. We investigated the surgical approach, ablative approach (radiofrequency and microwave ablation techniques) and systemic therapy approach (including chemotherapy and hormonal therapy). Although other forms of local treatment have also been described, we considered only the most commonly reported modalities for which sufficient data were available.

The primary limitation of our study is the limited quality of data with a lack of comparative data or clear selection criteria for resectability of BCLM. As a result, the included data were highly heterogenous and precluded any adjusted or case-matched analysis. Single metastases were present only in 48% of cases and extrahepatic disease in 25%. As a result, the included data are unable to control for patient or disease factors, and are subject to selection bias with differences between different treatment groups.

In addition, the survival outcomes reported in some retrospective series may reflect patient selection, increasing the possibility of inherent selection bias as opposed to a distinct therapeutic benefit of surgery, which may not have appropriate propensity score matching.10 This may also occur because not all patients will have been eligible candidates for surgical intervention or radiofrequency ablation, thereby introducing further bias.

These results illustrate the potential survival advantage that may be gained by the addition of local tumour control strategies to systemic therapy. Additional effects on survival rates may be ascribed to the advance of chemotherapeutic agents over time. For the purposes of our analysis, treatment with chemotherapy was pooled, regardless of which agents were used, potentially introducing additional heterogeneity.

Another limitation concerns the immunohistochemical profile of tumour subtypes. The hormone receptor profiles of both the primary breast cancer and liver metastases were not analysed in all studies; this may have some bearing on prognostication and stratifying disease management in patients.66,67 This may also affect the outcomes reported due to the introduction, in the past two decades, of her2neu therapy as neoadjuvant treatment for primary disease, due to the wide range of included dates in the inclusion criteria.

In addition, although we have reported receptor status in the subgroups, the lack of consistent data across the studies limits the analysis of any differences in cohorts of receptors, particularly as we know that patients with ER-positive disease and her2neu disease may do well with systemic therapy, where triple-negative outcomes are uniformly worse. However, although studies did report the number of patients receiving neoadjuvant targeted therapy, no sub-analysis is provided to allow for further elucidation on the impact this could have had on OS.

Conclusions

Local therapies such as liver resection and radiofrequency ablation may be considered safe and effective techniques for BCLM treatment in select populations, either in isolation or in conjunction with systemic therapies. Insufficient data are available to directly compare these treatments or clearly define patient selection strategies. Further prospective studies to define the best approach for oligometastatic breast cancer, particularly with reference to BCLM, are required as to date there have been no randomised controlled trials comparing the outcomes between hepatic resection and non-hepatic resection in BCLM patients.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit Ret al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guarneri V, Conte P. Metastatic breast cancer: therapeutic options according to molecular subtypes and prior adjuvant therapy. Oncologist 2009; 14: 645–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singletary SE, Walsh G, Vauthey JNet al. A role for curative surgery in the treatment of selected patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 2003; 8: 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma R, Feng Y, Lin Set al. Mechanisms involved in breast cancer liver metastasis. J Transl Med 2015; 13: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Castiglione M. Relapse of breast cancer after adjuvant treatment in premenopausal and perimenopausal women: patterns and prognoses. J Clin Oncol 1988; 6: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passot G, Soubrane O, Giuliante Fet al. Recent advances in chemotherapy and surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Liver Cancer 2016; 6: 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardoso F, Costa A, Senkus Eet al. 3rd ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 3). Breast 2017; 31: 244–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SCet al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis Of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000; 283: 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, Welton NJ. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published kaplan-meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun YS, Mizuno T, Cloyd JMet al. Hepatic resection for breast cancer liver metastases: impact of intrinsic subtypes. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020; 46: 1588–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Y, He XG, Zhou CMet al. Comparison of hepatic resection and systemic treatment of breast cancer liver metastases: A propensity score matching study. Am J Surg 2020; 220: 945–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He X, Zhang Q, Feng Yet al. Resection of liver metastases from breast cancer: a multicentre analysis. Clin Transl Oncol 2020; 22: 512–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucidi V, Bohlok A, Liberale Get al. Extended time interval between diagnosis and surgery does not improve the outcome in patients operated for resection or ablation of breast cancer liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020; 46: 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundén M, Hermansson C, Taflin Het al. Surgical treatment of breast cancer liver metastases - A nationwide registry-based case control study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020; 46: 1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung TT, Chok KS, Chan ACet al. Survival analysis of breast cancer liver metastasis treated by hepatectomy: A propensity score analysis for Chinese women in Hong Kong. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2019; 18: 452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacalbasa N, Balescu I, Ilie Vet al. The impact on the long-term outcomes of hormonal status after hepatic resection for breast cancer liver metastases. In Vivo (Brooklyn) 2018; 32: 1247–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labgaa I, Slankamenac K, Schadde Eet al. Liver resection for metastases not of colorectal, neuroendocrine, sarcomatous, or ovarian (NCNSO) origin: A multicentric study. Am J Surg 2018; 215: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz A, Sebagh M, Wicherts DAet al. Long-term survival and cure model following liver resection for breast cancer metastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018; 170: 89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz A, van Hillegersberg R, Siesling Set al. Surgical resection versus systemic therapy for breast cancer liver metastases: results of a european case matched comparison. Eur J Cancer 2018; 95: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbas H, Erridge S, Sodergren MHet al. Breast cancer liver metastases in a UK tertiary centre: outcomes following referral to tumour board meeting. Int J Surg 2017; 44: 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz A, Wicherts DA, Sebagh Met al. Predictive profile-nomogram for liver resection for breast cancer metastases: An aggressive approach with promising results. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 535–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margonis GA, Buettner S, Sasaki Ket al. The role of liver-directed surgery in patients with hepatic metastasis from primary breast cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2016; 18: 700–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadot E, Lee SY, Sofocleous CTet al. Hepatic resection or ablation for isolated breast cancer liver metastasis: A case-control study With comparison to medically treated patients. Ann Surg 2016; 264: 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacalbasa N, Dima SO, Purtan-Purnichescu Ret al. Role of surgical treatment in breast cancer liver metastases: a single center experience. Anticancer Res 2014; 34: 5563–5568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabol M, Donat R, Chvalny Pet al. Surgical management of breast cancer liver metastases. Neoplasma 2014; 61: 601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JY, Park JS, Lee SAet al. Does liver resection provide long-term survival benefits for breast cancer patients with liver metastasis? A single hospital experience. Yonsei Med J 2014; 55: 558–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariani P, Servois V, De Rycke Yet al. Liver metastases from breast cancer: surgical resection or not? A case-matched control study in highly selected patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013; 39: 1377–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostov DV, Kobakov GL, Yankov DV. Prognostic factors related to surgical outcome of liver metastases of breast cancer. J Breast Cancer 2013; 16: 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dittmar Y, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Schüle Set al. Liver resection in selected patients with metastatic breast cancer: a single-centre analysis and review of literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013; 139: 1317–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polistina F, Costantin G, Febbraro Aet al. Aggressive treatment for hepatic metastases from breast cancer: results from a single center. World J Surg 2013; 37: 1322–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Walsum GA, de Ridder JA, Verhoef Cet al. Resection of liver metastases in patients with breast cancer: survival and prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012; 38: 910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groeschl RT, Nachmany I, Steel JLet al. Hepatectomy for noncolorectal non-neuroendocrine metastatic cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2012; 214: 769–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbott DE, Brouquet A, Mittendorf EAet al. Resection of liver metastases from breast cancer: estrogen receptor status and response to chemotherapy before metastasectomy define outcome. Surgery 2012; 151: 710–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan XF, Dong NN, Zhang T, Li Q. Comparison of surgical outcomes in patients with colorectal liver metastases versus non-colorectal liver metastases: A Chinese experience. Hepatol Res 2012; 42: 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubino A, Doci R, Foteuh JCet al. Hepatic metastases from breast cancer. Updates Surg 2010; 62: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann K, Franz C, Hinz Uet al. Liver resection for multimodal treatment of breast cancer metastases: identification of prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17: 1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caralt M, Bilbao I, Cortés Jet al. Hepatic resection for liver metastases as part of the ‘oncosurgical’ treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 2804–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lubrano J, Roman H, Tarrab Set al. Liver resection for breast cancer metastasis: does it improve survival? Surg Today 2008; 38: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thelen A, Benckert C, Jonas Set al. Liver resection for metastases from breast cancer. J Surg Oncol 2008; 97: 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adam R, Aloia T, Krissat Jet al. Is liver resection justified for patients with hepatic metastases from breast cancer? Ann Surg 2006; 244: 897–907; discussion -8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakamoto Y, Yamamoto J, Yoshimoto Met al. Hepatic resection for metastatic breast cancer: prognostic analysis of 34 patients. World J Surg 2005; 29: 524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vlastos G, Smith DL, Singletary SEet al. Long-term survival after an aggressive surgical approach in patients with breast cancer hepatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2004; 11: 869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elias D, Maisonnette F, Druet-Cabanac Met al. An attempt to clarify indications for hepatectomy for liver metastases from breast cancer. Am J Surg 2003; 185: 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selzner M, Morse MA, Vredenburgh JJet al. Liver metastases from breast cancer: long-term survival after curative resection. Surgery 2000; 127: 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pocard M, Pouillart P, Asselain B, Salmon R. Hepatic resection in metastatic breast cancer: results and prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol 2000; 26: 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bai XM, Yang W, Zhang ZYet al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic analysis of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in liver metastasis from breast cancer. Int J Hyperthermia 2019; 35: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Onal C, Guler OC, Yildirim BA. Treatment outcomes of breast cancer liver metastasis treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. Breast 2018; 42: 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veltri A, Gazzera C, Barrera Met al. Radiofrequency thermal ablation (RFA) of hepatic metastases (METS) from breast cancer (BC): an adjunctive tool in the multimodal treatment of advanced disease. Radiol Med 2014; 119: 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taşçi Y, Aksoy E, Taşkın HEet al. A comparison of laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation versus systemic therapy alone in the treatment of breast cancer metastasis to the liver. HPB (Oxford) 2013; 15: 789–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carrafiello G, Fontana F, Cotta Eet al. Ultrasound-guided thermal radiofrequency ablation (RFA) as an adjunct to systemic chemotherapy for breast cancer liver metastases. Radiol Med 2011; 116: 1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meloni MF, Andreano A, Laeseke PFet al. Breast cancer liver metastases: US-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation–intermediate and long-term survival rates. Radiology 2009; 253: 861–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jakobs TF, Hoffmann RT, Schrader Aet al. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatic metastases from breast cancer. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009; 32: 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sofocleous CT, Nascimento RG, Gonen Met al. Radiofrequency ablation in the management of liver metastases from breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189: 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Q, Lee K, Xu Fet al. Metronomic chemotherapy of cyclophosphamide plus methotrexate for advanced breast cancer: real-world data analyses and experience of one center. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2020; 40: 222–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aarts BM, Klompenhouwer EG, Dresen RCet al. Intra-arterial mitomycin C infusion in a large cohort of advanced liver metastatic breast cancer patients: safety, efficacy and factors influencing survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019; 176: 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Er O, Frye DK, Kau SWet al. Clinical course of breast cancer patients with metastases limited to the liver treated with chemotherapy. Cancer J 2008; 14: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pentheroudakis G, Fountzilas G, Bafaloukos Det al. Metastatic breast cancer with liver metastases: a registry analysis of clinicopathologic, management and outcome characteristics of 500 women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 97: 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eichbaum MH, Kaltwasser M, Bruckner Tet al. Prognostic factors for patients with liver metastases from breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 96: 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li XP, Meng ZQ, Guo WJ, Li J. Treatment for liver metastases from breast cancer: results and prognostic factors. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 3782–3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nabholtz JM, Senn HJ, Bezwoda WRet al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus mitomycin plus vinblastine in patients with metastatic breast cancer progressing despite previous anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoe AL, Royle GT, Taylor I. Breast liver metastases–incidence, diagnosis and outcome. J R Soc Med 1991; 84: 714–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tasleem S, Bolger JC, Kelly MEet al. The role of liver resection in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review examining the survival impact. Ir J Med Sci 2018; 187: 1009–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abbas S, Lam V, Hollands M. Ten-year survival after liver resection for colorectal metastases: systematic review and meta-analysis. ISRN Oncol 2011; 2011: 763245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cavalcoli F, Rausa E, Conte Det al. Is there still a role for the hepatic locoregional treatment of metastatic neuroendocrine tumors in the era of systemic targeted therapies? World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 2640–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedel G, Pastorino U, Ginsberg RJet al. Results of lung metastasectomy from breast cancer: prognostic criteria on the basis of 467 cases of the international registry of lung metastases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002; 22: 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soni A, Ren Z, Hameed Oet al. Breast cancer subtypes predispose the site of distant metastases. Am J Clin Pathol 2015; 143: 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kimbung S, Kovács A, Danielsson Aet al. Contrasting breast cancer molecular subtypes across serial tumor progression stages: biological and prognostic implications. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 33306–33318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]