Abstract

Combination therapy with estrogen and spironolactone may help some transgender women achieve desired results. We used two databases, OptumLabs® Data Warehouse (OLDW) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA), to examine trends in feminizing therapy. We included 3368 transgender patients from OLDW and 3527 from VHA, all of whom received estrogen, spironolactone, or both between 2006 and 2017. In OLDW, the proportion receiving combination therapy increased from 47% to 75% during this period. Similarly, in VHA, the proportion increased from 39% to 69% during this period. We conclude that the use of combination hormone therapy has become much more common over the past decade.

Keywords: aldosterone antagonists, drug therapy, hormones, transgender persons

Background

Exogenous hormones are the most commonly used gender-affirming medical intervention for transgender patients.1,2 For transfeminine patients in the United States, individuals assigned a male sex at birth who have female gender identity, gender-affirming hormone treatment most commonly consisting of estrogen, with or without an adjunctive anti-androgen.3,4 In the United States, spironolactone is the most common adjunctive anti-androgen.

Estrogen acts directly on the estrogen receptor to promote the expression of feminine characteristics. In addition, estrogens act centrally to suppress the gonadotropin axis, resulting in lower levels of testosterone. While estrogen can reduce testosterone levels, unless given in supratherapeutic doses, it is not always effective in decreasing levels into the cisgender-female range. Spironolactone can be given along with estrogen to help reduce the effects of endogenous testosterone, when the patient has not undergone orchiectomy and is not receiving centrally acting hormone-blocking therapy, such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs. Spironolactone can help achieve more effective feminization without the need to pursue supratherapeutic levels of estrogen.5

There have been relatively few studies characterizing national patterns of feminizing hormone therapy in the transgender population in the United States, and those that have been published have used convenience samples.

While guidelines for managing feminizing therapy have not changed appreciably in the past decade, it can take a decade or more for best practices to be fully adopted into practice6; therefore, many clinicians may still be adjusting their practice patterns to these recommendations suggesting use of both estrogen and spironolactone. A lack of self-identified gender data has limited the use of large national databases to study these issues.7 Our group has recently developed methods to identify transgender patients and further identify those receiving feminizing and masculinizing treatment, unlocking our ability to use large administrative databases to study the care provided to transgender patients.8–10

We, therefore, used two such databases to examine trends in feminizing hormones for transgender patients over time. We used a database comprising commercially insured patients and another that consists of military veterans. Thus, we are able to report trends in feminizing hormone therapy that likely apply to a broad range of U.S. patients, while also commenting on differences in practice between the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system and a sample of commercially insured patients.

Materials and Methods

Our study relied on two large U.S. databases: the OptumLabs® Data Warehouse (OLDW) and the VHA. OLDW is a deidentified administrative claims database of commercially insured patients.11 Commercially insured patients tend to be younger and healthier than the general population. VHA is the nation's largest integrated health care system. VHA patients are known to have poorer health and more disability than the general U.S. population.12 Altogether, these two databases capture a relatively broad picture of care for transgender patients in the United States.

We previously published our methods to identify transgender patients in both databases.8,10 Briefly, in the OLDW, we used multiple strategies to identify transgender patients. While most patients were identified as transgender based on gender dysphoria (GD) diagnosis codes (69% of them), we were able to identify additional transgender persons by using several non-GD strategies, including a combination of diagnosis codes for endocrine disorder not otherwise specified (Endo NOS), surgical procedures often used for gender affirmation, and receiving hormones usually intended for one gender while being identified as the other gender.8

In our previous publication, we showed that these non-GD strategies were particularly important in earlier years of the study, and helped identify a sample of transgender patients that was more representative and more similar to the patients identified by GD codes in later years.8

Finding transgender patients in VHA data was a somewhat different process, in that there is no billing in VHA per se, and therefore no incentive for clinicians to use codes such as “Endocrine disorder NOS” to ensure payment by insurance companies. We found that the best strategy to use in VHA data was in fact to depend entirely on the GD codes, since other non-GD strategies (such as the ones we had used with OLDW) identified too many false positives. This approach was found to have a positive predictive value of 0.83 for finding transgender patients, compared with a gold standard of chart review.10

The present study included data from the OLDW and VHA from 2006 through 2017. We performed identical analyses in both datasets to ensure comparable results. Patients were considered to have received estrogen if they had received at least one of several estrogen products (Appendix A1). Because spironolactone is used for other reasons than gender affirmation, patients were considered to have received spironolactone for gender affirmation if they received a dose exceeding 50 mg/day, and did not have a diagnosis code for chronic liver disease or congestive heart failure (Appendix A2). These requirements for spironolactone (minimal dose requirement, absence of severe liver or heart disease) were intended to ensure that the spironolactone was being given for transgender hormone therapy.

We grouped the 12-year study period into four periods of 3 years each (2006–2008, 2009–2011, 2012–2014, and 2015–2017) to increase cell sizes and allow for more stable trends over time. Each unique patient was counted in the first period when they received therapy, and was not counted for later periods. We examined what proportion of patients received estrogen monotherapy, spironolactone monotherapy, or combination therapy for gender-affirming therapy. Statistical tests included chi-square tests and tests for linear trend over time. We used SAS 9.4 to perform all analyses (SAS Corporation, Cary, NC). Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Bedford VA Medical Center, the RAND Corporation, and Boston University.

Results

A comparable number of transgender patients in each dataset had received femininizing hormones: 3368 in the OLDW and 3527 in the VHA. Table 1 compares baseline characteristics of the two populations receiving femininizing hormones by age and comorbid conditions. The OLDW sample was younger; for example, 44% of the OLDW sample was ages 18–29, compared with 14% of the VHA sample (p<0.001). The VHA sample had a higher burden of chronic conditions, and for some conditions this was a marked difference, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (27% VHA vs. 6% OLDW, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Transgender Patients, Receiving Feminizing Hormone Therapy, in Each Database

| OptumLabs Data Warehouse (n=3368) | Veterans Health Administration (n=3527) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 1470 (44%) | 504 (14%) | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 756 (22%) | 574 (16%) | |

| 40–49 | 524 (16%) | 626 (18%) | |

| 50–64 | 502 (15%) | 1518 (43%) | |

| 65+ | 116 (3%) | 305 (9%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 2430 (72%) | 2941 (83%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 339 (10%) | 120 (3%) | |

| Hispanic | 290 (9%) | 106 (3%) | |

| Asian | 115 (3%) | 40 (1%) | |

| Other/unknown | 194 (6%) | 320 (9%) | |

| Region | |||

| Midwest | 882 (26%) | 756 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Northeast | 336 (10%) | 398 (11%) | |

| South | 1338 (40%) | 988 (28%) | |

| West | 812 (24%) | 1385 (39%) | |

| Health conditions | |||

| Alcohol use disorder | 201 (6%) | 271 (8%) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | 351 (10%) | 531 (15%) | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | 146 (4%) | 132 (4%) | 0.21 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 35 (1%) | 32 (1%) | 0.58 |

| Depression | 1546 (46%) | 2040 (58%) | <0.001 |

| Drug use disorder | 256 (8%) | 382 (11%) | <0.001 |

| HIV | 132 (4%) | 73 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1062 (32%) | 1222 (35%) | 0.006 |

| Hypertension | 875 (26%) | 1132 (32%) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 37 (1%) | 29 (1%) | 0.24 |

| post-traumatic stress disorder | 195 (6%) | 941 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco use | 515 (15%) | 778 (22%) | <0.001 |

In the OLDW, combination therapy became much more common over time, rising from 47% in 2006–2008 to 75% in 2015–2017 (p<0.001 for trend, Fig. 1). Estrogen monotherapy became much less common over the same period, decreasing from 45% to 14% (p<0.001 for trend); spironolactone monotherapy was somewhat uncommon throughout the study period (∼10% at all time points). Excluding patients who had undergone prior orchiectomy (91 patients, or 3% of the sample) did not meaningfully change these results (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Trends in feminizing therapy in the OptumLabs Data Warehouse.

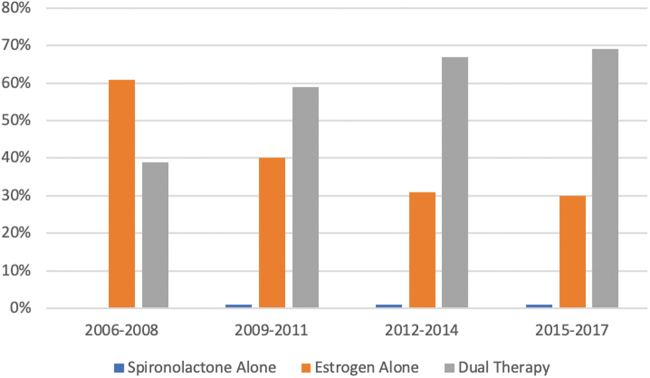

In the VHA, a similar pattern was observed, although the change in practice appeared to occur somewhat earlier, with little change in practice during the final 3 years of the study (Fig. 2). Combination therapy increased from 39% in 2006–2008 to 69% in 2015–2017 (p<0.001 for trend). Estrogen monotherapy decreased from 61% in 2006–2008 to 30% in 2015–2017 (p<0.001 for trend). Spironolactone monotherapy was extremely uncommon (1% in all years).

FIG. 2.

Trends in feminizing therapy in the VHA system. VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Discussion

We report 12-year patterns of feminizing hormone therapy among transgender patients in two large U.S. databases. We found that combination therapy (estrogen+spironolactone) became almost twice as common by the end of the study as it was at the beginning. Estrogen monotherapy became less common over the same period. To our knowledge, this is the first such report to use large administrative databases and exemplifies the kind of study that can be conducted when transgender patients can be identified in population-level data.

These trends may result from a number of factors. One possible explanation is that more clinicians have gained expertise in transgender medicine during the study period,13 allowing more transgender patients to receive care from a provider with expertise in transgender health care. VHA, for example, engaged in a multi-year effort to increase the supply of clinicians qualified to deliver such care.14

Another possible explanation is that while guideline recommendations have not changed markedly over this period,3,15,16 guidelines may have been codified into clinical protocols over time at the level of the organization, clinic, or hospital, which could lead to more use of combination hormone therapy. For example, VHA promulgated clinical recommendations for transgender hormone therapy in 2011 that recommended at least considering combination therapy for many patients.17 Before this, VHA recommendations were much less clear, and so the clarifying guidance may have led to a considerable change in practice patterns.

Finally, over the course of the study period, VHA and many commercial insurers issued clearer statements that transgender hormone therapy would indeed be covered18; while such therapy was not explicitly forbidden at the beginning of the study, clearer statements allowing its use may have also encouraged different forms of therapy over time. However, our database study is not equipped to examine the role that these changes may have had in producing the patterns we observed.

Another reason why estrogen monotherapy may have persisted despite guidelines calling for a combination therapy approach is that many patients may not need or want to take spironolactone. Indeed, some patients have undergone surgical orchiectomy or are using GnRH analogs, both of which render spironolactone unnecessary.3,15 Other patients may not have a goal of maximizing feminine characteristics,16 for example, due to a nonbinary gender identity, and therefore may not need spironolactone to achieve their goals.

Although these data indicate that estrogen monotherapy has become less common and combination therapy more common over the past 12 years, these trends may not continue indefinitely. For example, as more patients become more comfortable expressing a nonbinary gender identity, this may reduce the proportion of patients who have a goal of maximizing feminine characteristics.

Our study suggests that treatment patterns may differ across health systems or across patient populations, with estrogen monotherapy being more common in VHA than in OLDW, both at the beginning of the study (61% vs. 45%, p<0.001) and at the end of the study (30% vs. 14%, p<0.001). In contrast, spironolactone monotherapy was used for some patients in OLDW, but rarely in the VHA (11% vs. 1%, averaged across the study, p<0.001).

Differences in illness burden between the patient populations may play a role in this difference in therapy, as the VHA population was older and had a higher level of comorbid illness, possibly making clinicians more hesitant to use spironolactone, lest it precipitate hyperkalemia.16 There may also be differences between these two populations in terms of the proportion of patients seeking to maximize feminine characteristics. Nonetheless, our study shows clear trends in the increased use of combination therapy among transgender people, which suggests that practice trends are increasingly aligning with national guidelines for transgender care.

Our study has several limitations. In OLDW, we could not perform a chart review, because free text notes were not available to us, so we cannot be certain that the patients in our study indeed identified as transgender. However, we used thoughtful approaches that favored specificity over sensitivity.

In addition, we chose to count each patient once, based on the first period in which they received therapy. We could have counted them in each period in which they appeared, but since many patients continue the same therapy, we believe this would have given a false impression of how prescribing patterns are changing over time. Furthermore, we included patients who had undergone orchiectomy in the sample. It was a deliberate choice to include such patients to characterize hormone therapy among a broad population of transfeminine patients. However, in a sensitivity analysis, excluding them did not change the results.

In conclusion, patterns of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender patients changed considerably during the period from 2006 to 2017 in the United States, with combination therapy (estrogen+spironolactone) becoming much more common over this period, while estrogen monotherapy became a much less commonly used regimen. This study shows how we can gain further insight into the care of transgender patients by unlocking the power of large, representative databases.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the academic affiliates, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Abbreviations Used

- Endo NOS

endocrine disorder not otherwise specified

- GD

gender dysphoria

- GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- OLDW

OptumLabs® Data Warehouse

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

Appendix

Appendix A1. List of Feminizing Hormone Prescriptions with No Dose Requirements

DESOG-E.ESTRADIOL/E.ESTRADIOL

DESOGESTREL–ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

ESTRADIOL

ESTRADIOL ACETATE

ESTRADIOL CYPIONATE

ESTRADIOL HEMIHYDRT, MICRONIZED

ESTRADIOL MICRONIZED

ESTRADIOL VALERATE

ESTRADIOL VALERATE/DIENOGEST

ESTRADIOL/DROSPIRENONE

ESTRADIOL/NORETH AC

ESTRADIOL/NORETHINDRONE ACET

ESTRIOL MICRONIZED

ESTROGEN, CON/M-PROGEST ACET

ESTROGEN, ESTER/ME-TESTOSTERONE

ESTROGENS, CONJUGATED

ESTROGENS, CONJ., SYNTHETIC A

ESTROGENS, CONJ., SYNTHETIC B

ESTROGENS, CONJUGATED

ESTROGENS, ESTERIFIED

ESTRONE

ESTROPIPATE

ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

ETHINYL ESTRADIOL/DROSPIRENONE

ETONOGESTREL/ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

L-NORGEST-ETH ESTR/ETHIN ESTRA

L-NORGEST/E.ESTRADIOL-E.ESTRAD

L-NORGEST/E.ESTRADION-E.ESTRAD

LEVONORGESTREL

LEVONORGESTREL-ETH ESTRA

LEVONORGESTREL-ETH ESTRADIOL

LEVONORGESTREL-ETHIN ESTRADIOL

NORELGESTROMIN/ETHIN.ESTRADIOL

NORETH A-ET ESTRA/FE FUMARATE

NORETH-ETHINYL ESTRADIOL/IRON

NORETHIND AC/ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

NORETHINDRONE

NORETHINDRONE A-E ESTRADIOL

NORETHINDRONE AC-ETH ESTRADIOL

NORETHINDRONE ACETATE

NORETHINDRONE-ETHINYL ESTRAD

NORGESTIMATE-ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

NORGESTREL-ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

DESOG-ET ESTRA/ETHIN ESTRA

DROSPIR/ETH ESTRA/LEVOMEFOL CA

DROSPIRENONE/ESTRADIOL

ESTRAD CYP/M-PROGEST ACET

ESTRADIOL BENZOATE

ESTRADIOL/LEVONORGESTREL

ESTRADIOL/NORGESTIMATE

ESTRIOL

ESTROGENS, CONJUGATED/MEPROBAM

ESTROGENS, CONJ/BAZEDOXIFENE

ESTROGENS, CONJUGATED/MEPROBAM

ETHINYL ESTRADIOL/NORELGEST

ETHINYL ESTRADIOL/NORETH AC

ETHYNODIOL D-ETHINYL ESTRADIOL

L-NORGEST-ETH ESTR/PRG TST KIT

LEVONORGEST/ETH.ESTRADIOL/IRON

NORETHINDRONE-E. ESTRADIOL-IRON

NORETHINDRONE-ETHIN ESTRADIOL

NORETHINDRONE-MESTRANOL

QUINESTROL

Appendix A2.

The following products constitute spironolactone, when given in a dose of >50 mg/day.

SPIRONOLACTONE

SPIRONOLACTONE, MICRONIZED

The following rules apply to spironolactone, to consider it as being used as part of gender-affirming therapy.

List of exclusionary diagnoses for spironolactone prescriptions

| Code type | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 398.91 | Rheumatic heart failure (congestive) |

| ICD-9 | 402.01 | Malignant hypertensive heart disease with heart failure |

| ICD-9 | 402.11 | Benign hypertensive heart disease with heart failure |

| ICD-9 | 402.91 | Unspecified hypertensive heart disease with heart failure |

| ICD-9 | 404.01 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, malignant, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified |

| ICD-9 | 404.03 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, malignant, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage V, or end-stage renal disease |

| ICD-9 | 404.11 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, benign, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified |

| ICD-9 | 404.13 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, benign, with heart failure and chronic kidney disease stage V, or end-stage renal disease |

| ICD-9 | 404.91 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, unspecified, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified |

| ICD-9 | 404.93 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, unspecified, with heart failure and chronic kidney disease stage V, or end-stage renal disease |

| ICD-9 | 428 | Heart failure |

| ICD-9 | 456 | Varicose veins of other sites |

| ICD-9 | 456.1 | Esophageal varices without mention of bleeding |

| ICD-9 | 456.2 | Esophageal varices in diseases classified elsewhere |

| ICD-9 | 571 | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis |

| ICD-9 | 571.2 | Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver |

| ICD-9 | 571.3 | Alcoholic liver damage, unspecified |

| ICD-9 | 571.4 | Chronic hepatitis |

| ICD-9 | 571.5 | Cirrhosis of liver without mention of alcohol |

| ICD-9 | 571.6 | Biliary cirrhosis |

| ICD-9 | 571.7 | Fatty (change of) liver, not elsewhere classified/Other specified diseases of liver |

| ICD-9 | 571.8 | Other chronic nonalcoholic liver disease |

| ICD-9 | 571.9 | Unspecified chronic liver disease without mention of alcohol |

| ICD-9 | 572.2 | Hepatic encephalopathy |

| ICD-9 | 572.3 | Portal hypertension |

| ICD-9 | 572.4 | Hepatorenal syndrome |

| ICD-9 | 572.5 | Hepatic fibrosis |

| ICD-9 | 572.6 | Hepatic fibrosis/unspecified cirrhosis of liver/other cirrhosis of liver |

| ICD-9 | 572.7 | |

| ICD-9 | 572.8 | Other sequelae of chronic liver disease |

| ICD-9 | 572.9 | |

| ICD-10 | I09.9 | Rheumatic heart disease, unspecified |

| ICD-10 | I11.0 | Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure |

| ICD-10 | I13.0 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease with heart failure and stage 1 through stage 4 chronic kidney disease, or unspecified chronic kidney disease |

| ICD-10 | I13.2 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease with heart failure and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, or end-stage renal disease |

| ICD-10 | I25.5 | Ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| ICD-10 | I42.0 | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| ICD-10 | I42.5 | Other restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| ICD-10 | I42.6 | Alcoholic cardiomyopathy |

| ICD-10 | I42.7 | Cardiomyopathy due to drug and external agent |

| ICD-10 | I42.8 | Other cardiomyopathies |

| ICD-10 | I42.9 | Cardiomyopathy, unspecified |

| ICD-10 | I43 | Cardiomyopathy in diseases classified elsewhere |

| ICD-10 | I50 | Heart failure |

| ICD-10 | I85 | Esophageal varices |

| ICD-10 | I86.4 | Gastric varices |

| ICD-10 | K70 | Alcoholic liver disease |

| ICD-10 | K71.7 | Toxic liver disease with fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver |

| ICD-10 | K72 | Hepatic failure, not elsewhere classified |

| ICD-10 | K74 | Fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver |

| ICD-10 | K76.7 | Hepatorenal syndrome |

| ICD-10 | P29.0 | Neonatal cardiac failure |

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIH-NIMHD-1R21-MD012371–01).

Cite this article as: Rose AJ, Hughto JMW, Dunbar MS, Quinn EK, Deutsch M, Feldman J, Radix A, Safer JD, Shipherd JC, Thompson J, Jasuja GK (2023) Trends in feminizing hormone therapy for transgender patients, 2006–2017, Transgender Health 8:2, 188–194, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2021.0041.

References

- 1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Simpson TL, et al. Hormone therapy, gender affirmation surgery, and their association with recent suicidal ideation and depression symptoms in transgender veterans. Psychol Med. 2017;48:2329–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869–3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Care of transgender persons. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2451–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prior JC, Vigna YM, Watson D. Spironolactone with physiological female steroids for presurgical therapy of male-to-female transsexualism. Arch Sex Behav. 1989;18:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cahill SR, Baker K, Deutsch MB, et al. Inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity in stage 3 meaningful use guidelines: a huge step forward for LGBT health. LGBT Health. 2016;3:100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jasuja GK, de Groot A, Quinn EK, et al. Beyond gender identity disorder diagnoses codes: an examination of additional methods to identify transgender individuals in administrative databases. Med Care. 2020;58:903–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blosnich JR, Cashy J, Gordon AJ, et al. Using clinician text notes in electronic medical record data to validate transgender-related diagnosis codes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25:905–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfe HL, Reisman JI, Yoon S, et al. Validating data-driven methods to identify transgender individuals in the Veterans Affairs. Am J Epidemiol. 2021. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwab102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. OptumLabs. OptumLabs and OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW) Descriptions and Citation. Eden Prairie, MN: July 2020. PDF. Reproduced with permission from OptumLabs. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252–3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hollenbach AD, Eckstrand KL, Dreger AD. Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender Nonconforming, or Born with DSD: a Resource for Medical Educators. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kauth MR, Shipherd JC. Transforming a system: improving patient-centered care for sexual and gender minority veterans. LGBT Health. 2016;3:177–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Professional Association for Transgender Health Practice Guidelines, Version 7. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deutch MB, ed. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People, 2nd ed. Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, University of California, San Francisco, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Transgender Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy Use. VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. Issued in 2011 and updated February, 2012. Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiggpeuq5f0AhXRgv0HHZIxBaEQFnoECAkQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2F www.pbm.va.gov%2Fclinicalguidance%2Fclinicalrecommendations%2Ftransgendercarecrosssexhormonetherapyfeb2012.doc&usg=AOvVaw0Rh9TjAbPr422ZwtljX50z Accessed November 14, 2021.

- 18. VHA Directive 1341(2). Providing Health Care for Transgender and Intersex Veterans. May 23, 2018. Amended June 26, 2020. Available at: https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=6431 Accessed November 14, 2021.