Abstract

Objective:

This study examined the trends in receipt of smoking cessation medications among smokers with and without mental illness, including serious mental illness, from 2005–2019 and characterized provider attitudes and practices related to tobacco screening and cessation treatment.

Methods:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data was analyzed to examine receipt of smoking cessation medications bupropion, varenicline, and nicotine replacement therapy among 55,662 total smokers, 18,353 with evidence of mental illness and 7,421 with serious mental illness, from 2005–2019. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 40 general internists and psychiatrists between October and November 2017 using a semi-structured interview guide. MEPS data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and interviews were analyzed using hybrid inductive-deductive coding.

Results:

From 2005–2019, at least 83% of smokers with or without mental illness did not receive varenicline, NRT, and/or bupropion. Across the 14-year study, the proportion of smokers receiving varenicline peaked at 2.1% among those with no documented mental illness, 2.9% among those with any mental illness, and 2.4% among those with serious mental illness. The comparable proportions for receipt of NRT peaked at 0.4%, 1.1%, and 1.6% and for bupropion peaked at 1.2%, 8.4%, and 16.7%. Qualitative themes were consistent across general internists and psychiatrists; providers viewed cessation treatment as challenging due to the perception of nicotine as a coping mechanism and agreed on barriers to treatment, including contra-indications for people with mental illness and lack of insurance coverage.

Conclusions:

System and provider-level strategies to support evidence-based smoking cessation treatment delivery for people with and without mental illness are needed.

INTRODUCTION

People with mental illness have a higher prevalence of tobacco smoking and smoke more frequently than people with no mental illness.(1–4) Rates of smoking declined significantly during the 2000s among individuals without mental illness, but not among individuals with mental illness.(5, 6) Estimates show less than 22% of individuals without mental illness smoke,(1) but this increases to about 30% among people with any mental illness and over 60% among people with schizophrenia.(1, 6, 7) Smokers with mental illness are also less likely to quit,(4, 5) with one study finding a 25% lower likelihood of quitting by a 2-year follow-up for those with versus those without a diagnosis.(2) High use and low quit rates contribute to individuals with mental illness being at significantly greater risk of dying from tobacco-linked diseases – such as chronic lower respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers – which account for an average of 50% of deaths among people with bipolar disorder, depression, and/or schizophrenia.(8, 9)

Smoking cessation programs are most effective when they include pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions,(10–13) but only 4.7% smokers receive cessation treatment that includes both.(14) Evidence-based behavioral interventions include clinician counseling or cognitive therapy aimed at changing/managing behaviors, situations, and environmental cues associated with smoking; and pharmacotherapy treatment includes three evidence-based medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).(12, 15) Pharmacotherapy is safe and effective for smokers with mental illness, as evidence shows these medications improve outcomes without worsening psychiatric symptoms.(16–19) However, estimates show only 25% of specialty mental health treatment facilities offer NRT and 21% offer non-nicotine cessation medications.(20) To date, no studies have examined cessation medication patterns in a nationally representative sample of people with and without mental illness.

Smokers with mental illness may experience specific barriers to smoking cessation treatment, in part due to incorrect beliefs among healthcare providers that smokers with mental illness do not want to quit or would not benefit from quitting.(21–23) People with mental illness commonly report that smoking alleviates mental health symptoms like poor concentration and stress;(23–25) but, research shows that smoking is associated with worse long-term behavioral and physical health outcomes for patients with mental illness.(26, 27) Despite this, providers have reported that they lack confidence to adequately address smoking cessation in patients with mental illness, and tensions exist between primary care providers and psychiatrists in deciding whose role it is to provide cessation treatment.(22, 24, 28) To better understand how psychiatrists and general internists delineate care related to cessation treatment for people with mental illness, more evidence is needed.

This study has two objectives. First, to examine trends in receipt of smoking cessation medications among smokers with and without mental illness among a nationally representative sample of the United States population. Second, to characterize general internist and psychiatrist attitudes and practices related to tobacco screening, smoking cessation treatment, and facilitators and barriers to delivering cessation treatment for patients with mental illness.

METHODS

Quantitative

We analyzed Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) survey data from 2005 to 2019 to examine receipt of smoking cessation medications among people with and without any mental illness, including serious mental illness. MEPS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics covering the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population. It is the most complete data source on health insurance coverage and the cost/use of health care.(29)

MEPS data files on demographics, medical conditions, prescribed medicines, inpatient and outpatient services, and office-based visits were merged across the 14 years of our study period (2005–2019). Final analytic files were constructed at the person-year-level. Our sample was restricted to individuals 18 years and older. People who smoke were identified by a binary variable of current smoking status for 2005–2017 and 2019. In 2018, MEPS removed this variable, so we created a comparable binary smoking variable using a categorical variable on how often the patient smoked: smoking every day or some days was categorized as a current smoker. In 2017, MEPS included both variables and sensitivity analysis showed less than 5% difference in identifying current smokers between measures.

We constructed measures indicating receipt of a prescription(s) for each FDA-approved smoking cessation medication – varenicline, bupropion, and NRT – and receipt of any cessation medication. Any mental illness was defined as: an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis of mental illness (ICD-9 295–301, 306–309, 311–314 and corresponding ICD-10s), any psychotropic drug use, a Kessler-6 score greater than 12, and/or a PHQ score greater than two. The Kessler-6 is a 6-item global measure of psychological distress drawing from depressive and anxiety related symptomology and PHQ is a nine-question instrument screening for the presence and severity of depression. Serious mental illness was defined by ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder (ICD-9 295–298), and/or a Kessler-6 score greater than 12.(30)

We characterized the study sample by age (18–34, 35–54, 55–74, 75+), sex, race/ethnicity and insurance status. The sample was adult smokers between 2005–2019 and analyzed between smokers with and without mental illness, including serious mental illness. We measured the proportion of smokers that received either varenicline, bupropion, or NRT and the proportion that received any cessation medication. We used survey weights in the analysis to generate representative estimates. Data analysis was completed using StataIC.

Qualitative

To understand facilitators and barriers in delivering smoking cessation medications to patients with mental illness, we interviewed general internists and psychiatrists between October and November 2017. We used MedPanel, a healthcare provider research panel, to screen and recruit providers for our study.(31) General internists were eligible if at least 30% of their work was clinical practice and their primary practice was either hospital outpatient, private practice, or a federally qualified health center. Psychiatrists were eligible if at least 30% of their work was clinical practice and either: 1) at least 10% of their patients had either schizophrenia and/or bipolar disorder; or 2) their primary practice was a community mental health clinic. MedPanel screened based on region so our sample was geographically diverse.

Interviews were conducted over the phone using a semi-structured interview guide. On average, interviews lasted 16 minutes. Interviews were conducted by a graduate-level research team member trained in qualitative data collection. An oral consent process was completed before each interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Transcripts were validated using the audio recordings and personally identifying information was removed from all transcripts.

The interview guide was created based on a review of the literature and our research questions. All interviewees estimated the proportion of their patients with any mental illness and serious mental illness, defined as major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and/or bipolar disorder. The domains of the guide were: 1) current cessation treatment practices; 2) barriers/facilitators delivering cessation treatment to individuals with mental illness; and 3) differences in cessation treatment between individuals with and without mental illness (internists only, as psychiatrists do not treat patients without mental illness).

Transcripts were analyzed using a hybrid inductive/deductive approach. The codebook development was informed by previous literature, the study team’s a priori knowledge, and summary memos created by the interviewer after each interview. The initial codebook was pilot tested and refined by two members of the study team through blind and independent double coding until the organization of themes was consistent across reviewers. The final codebook was applied to all interview transcripts. Coding and identification of themes was completed using NVivo 11. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Quantitative

The MEPS sample consisted of 55,662 smokers, 18,353 with evidence of any mental illness and 7,421 with evidence of serious mental illness. Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample was mostly white (79.8%), male (55.5%), and between 35–54 years old (41.4%). Most smokers with mental illness and serious mental illness in the sample were female (56.0% and 57.0%, respectively), relative to 38.9% of smokers without mental illness. Nearly 39% of smokers without mental illness were privately insured, but less than 27% of smokers with any mental illness and 18% of smokers with serious mental illness were privately insured.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) sample, 2005–20191

| Demographics | All Smokers | Smokers without a mental illness | Smokers with a mental illness | Smokers with a serious mental illness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=55,662 | N=37,309 | N=18,353 | N=7,421 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 29,738 | 55.5 | 22,098 | 61.2 | 7,640 | 44.0 | 2,991 | 43.0 |

| Female | 25,924 | 44.5 | 15,211 | 38.8 | 10,713 | 56.0 | 4,430 | 57.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 38,779 | 79.8 | 25,416 | 78.5 | 13,363 | 82.5 | 5,367 | 81.4 |

| Black | 12,646 | 13.8 | 8,895 | 14.9 | 3,751 | 11.7 | 1,525 | 12.1 |

| Hispanic | 9,121 | 10.0 | 6,655 | 11.2 | 2,466 | 7.8 | 1,077 | 8.5 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 17,405 | 31.4 | 12,389 | 33.0 | 5,016 | 28.2 | 1,995 | 28.7 |

| 35–54 | 23,175 | 41.4 | 15,148 | 40.5 | 8,027 | 43.4 | 3,367 | 43.9 |

| 55–74 | 13,598 | 24.4 | 8,739 | 23.7 | 4,859 | 25.9 | 1,878 | 25.0 |

| 75+ | 1,484 | 2.7 | 1,033 | 2.8 | 451 | 2.5 | 181 | 2.4 |

| Insurance | ||||||||

| Private | 16,254 | 34.7 | 12,270 | 38.7 | 7,090 | 26.7 | 1,023 | 17.5 |

| Medicaid | 7,031 | 9.5 | 3,622 | 7.2 | 3,984 | 14.2 | 1,744 | 19.1 |

| Medicare | 6,523 | 11.4 | 3,735 | 10.1 | 3,409 | 13.8 | 1,126 | 15.1 |

| Dual Medicaid/Medicare | 2,037 | 2.8 | 757 | 1.4 | 2,590 | 5.5 | 674 | 7.8 |

| Uninsured/Unknown | 23,817 | 41.6 | 16,925 | 42.6 | 1,280 | 39.8 | 3,020 | 40.4 |

Percentages are weighted

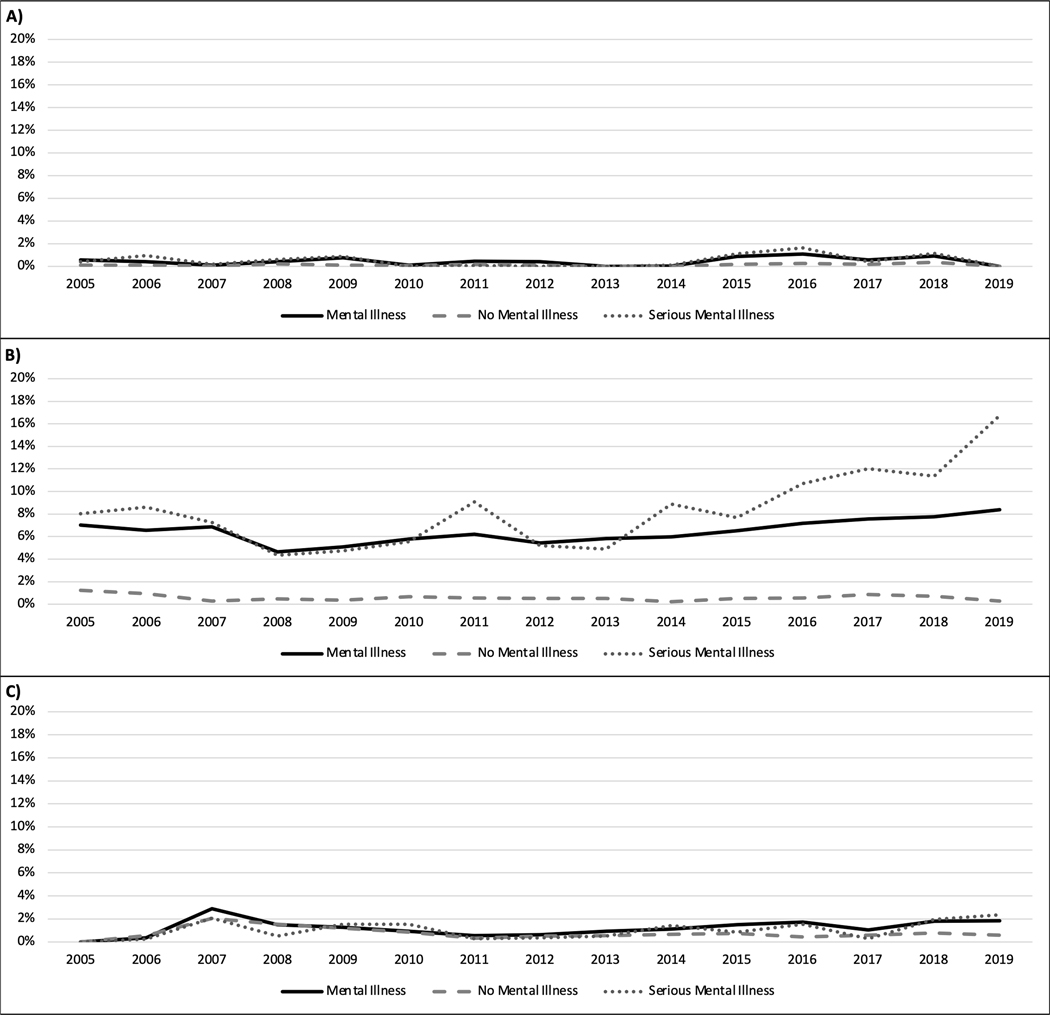

As shown in Figure 1, smoking cessation medications remained vastly under-prescribed for all smokers in our sample from 2005 to 2019. Nearly 83% of smokers without mental illness, smokers with any mental illness, and smokers with serious mental illness were not prescribed varenicline, NRT, and/or bupropion from 2005–2019, increasing to 98% not being prescribed varenicline or NRT – front line treatments for tobacco use disorder. Across the 14-year study period, the proportion of smokers receiving varenicline peaked at 2.1%, in 2007, among those with no documented mental illness, 2.9%, in 2007, among those with any mental illness, and 2.4%, in 2019, among those with serious mental illness. The comparable proportions for receipt of NRT peaked at 0.4% (2018), 1.1% (2016), and 1.6% (2016) and for bupropion peaked at 1.2% (2005), 8.4% (2019), and 16.7% (2019).

Figure 1.

Proportion of smokers with serious mental illness, any mental illness, and no mental illness receiving smoking cessation medication from a healthcare provider, per year

Notes: Panel A) Proportion of people who smoke who received the smoking cessation medication NRT from a healthcare provider, 2005–2019; Panel B) Proportion of people who smoke who received the smoking cessation medication bupropion from a healthcare provider, 2005–2019; Panel C) Proportion of people who smoke who received the smoking cessation medication varenicline from a healthcare provider, 2005–2019. Mental Illness is defined as an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis of mental illness (ICD-9 295–301, 306–309, 311–314 and corresponding ICD-10s), any psychotropic drug use, a Kessler-6 score greater than 12, and/or a PHQ score greater than two. Serious mental illness was defined by ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (295–298), and/or a Kessler-6 score greater than 12. The sample with mental illness includes any mental illness and serious mental illness.

The proportion of smokers without mental illness prescribed varenicline by a healthcare provider was 0.6% in 2006 – varenicline was not available for patients in 2005 – and 0.6% in 2019 among smokers without mental illness. Among smokers with any mental illness, receipt of varenicline increased from 0.4% in 2006 to 1.8% in 2019. Receipt of varenicline for smokers with serious mental illness increased from 0.3% in 2006 to 2.4% in 2019. Receipt of NRT was less than 0.1% in 2005 and peaked in 2018 at just under 0.4% among smokers without mental illness. Among smokers with any mental illness, receipt of NRT was 0.5% in 2005 and peaked at 1.1% in 2016. The proportion of smokers with serious mental illness being prescribed NRT was 0.4% in 2005 and peaked in 2016 at 1.6%. Among smokers without mental illness, receipt of bupropion decreased from 1.2% in 2005 to 0.3% in 2019. For smokers with any mental illness, receipt of bupropion increased from 7.0% in 2005 to 8.4% in 2019. The largest increase in the prescription of smoking cessation medication for smokers with serious mental illness was found with bupropion, increasing from 8.0% in 2005, to 16.7% in 2019.

Qualitative

We interviewed 20 general internists and 20 psychiatrists; Table 2 describes the provider characteristics. Most physicians were male (67.5%), 12.5% were aged 36–45, 40% were aged 46–55, and 47.5% were over 55 years old. Interviewees most commonly worked in private practices (50%). On average, general internists reported less than one-third of their patient’s had any mental illness and just over one-tenth had serious mental illness. Psychiatrists reported nearly two-thirds of their patients had serious mental illness and all had a mental illness. Most providers (95%) routinely screened patient’s smoking status and reported offering smoking cessation medications, but only 58% personally offered counseling for smoking cessation. Ninety percent of psychiatrists reported that screening for smoking status was integrated into their practice’s electronic health records (EHR), relative to 15% of general internists.

Table 2.

Physicians’ self-reported demographic and practice characteristics (N=40 physicians)

| General Internists | Psychiatrists | |

|---|---|---|

| n=20 | n=20 | |

| Provider Demographics | ||

| # Male | 13 | 14 |

| Provider age | ||

| 36–45 | 2 | 3 |

| 46–55 | 8 | 8 |

| 56+ | 10 | 9 |

| Region of Practice | ||

| Northeast | 3 | 6 |

| Midwest | 6 | 6 |

| West | 5 | 4 |

| South | 6 | 4 |

| Practice Setting | ||

| Private Practice | 13 | 7 |

| Hospital Outpatient | 5 | 9 |

| Community Clinic | 1 | 4 |

| Hospital Inpatient | 1 | 0 |

| Provider-Reported Patient Composition | ||

| Average % of patients with mental illness | 29% | 100% |

| Average % of patients with serious mental illness1 | 11% | 62% |

| Screening Practices | ||

| Routinely asks smoking status | 16 | 18 |

| Assesses patients’ willingness to quit | 20 | 17 |

| Screening for smoking status is integrated in electronic health record at their practice | 3 | 18 |

| Current Smoking Cessation Treatment Practices | ||

| Offers any medication | 20 | 18 |

| Offers varenicline | 19 | 14 |

| Offers bupropion | 18 | 17 |

| Offers nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) | 14 | 15 |

| Makes referrals to other providers for cessation treatment | 14 | 14 |

| Provides cessation counseling | 11 | 12 |

| Refers to hypnotists and/or acupuncturists | 6 | 1 |

| Encourages over the counter NRT | 4 | 1 |

Serious mental illness was defined as severe recurrent depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder

Qualitative themes were largely consistent across general internists and psychiatrists. Table 3 shows provider reported facilitators and barriers to delivering smoking cessation treatment, and differences in treatment approaches for patients with and without any mental illness. Facilitators most consistently noted were: 1) access to resources for patients, noted by 16 providers (8 internists; 8 psychiatrists); 2) the dual use of smoking cessation medications, mentioned by 12 providers (5 internists; 7 psychiatrists); and 3) the importance of insurance coverage for cessation medication, noted by 11 providers (6 internists, 5 psychiatrists). Barriers included: 1) patients’ perception that tobacco is a helpful coping mechanism, noted by 28 providers (12 internists, 16 psychiatrists); 2) unwillingness to engage in cessation practices among patients, mentioned by 19 providers (11 internists, 8 psychiatrists); and 3) inability to use certain medications – due to previous negative side effects for patients or interactions with psychotropic medications – noted by 14 providers (7 internists, 7 psychiatrists).

Table 3.

Provider Perceptions of Key Factors Influencing Smoking Cessation Treatment Practices

| Qualitative Themes | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Facilitators | |

| Resources for providers to give patients (e.g. quit hotline number, community programs, specialist access) N=16 total, 8 internists, 8 psychiatrists |

Internist:

Well, the thing that makes it the easiest for me is having a behavioral psychologist down the hall. I mean, that’s a tremendous resource. And then in Oregon, having the Tobacco Quit Line readily available, and if that continues to maintain funding, of course, through tobacco taxes, that’s great. And then again, we have a large population of patients that are on Providence Health Plan because we’re a Providence affiliated hospital. And that particular health plan has pretty good smoking cessation telephone support. Psychiatrist: The availability of programs outside of – or in the community – is really important. Knowing about those programs is really important to me. I don’t think that most of these programs-- either they’re not doing a very good job of publicizing their program or we as clinicians don’t know how to find them because there are just very few of them it seems. I’ve been practicing for a while, and I can name you very, very few programs. For example, in [my city] there’s one that’s pretty popular. So, I know about that one, and I have known about that one for several years, and I tend to refer a lot of people there. But I don’t know of too many other programs around in the city. |

| Dual use of smoking cessation medications for patient illnesses N=12 total, 5 internists, 7 psychiatrists |

Internist:

For a depressed patient, I have seen that Wellbutrin works very well. And I think it hopefully gives them some energy too. And Wellbutrin is a great medicine. I really like that one, and the patients are benefit with that. So that’s good. Psychiatrist: Well, I tried it-- with my depressed patients, I always think of bupropion because it’s good for your depression and it helps them with their smoking. So that’s something that I offer to my depressed patients quite a bit. |

| Insurance coverage of smoking cessation medications N=11 total, 6 internists, 5 psychiatrists |

Internist:

I can provide what is covered. And usually, I work with the psychiatrist to try to do CBT and other things to help them if medications can’t be afforded. Psychiatrist: The state hospital is somewhat limited with resources. So, we do have nicotine patches. There’s bupropion available. I don’t think they provide Chantix on the formulary. Varenicline and the other forms of nicotine gum and candy, I believe you can obtain, but that’s what usually we have on the formulary. It’s usually patches. |

| Barriers | |

| Smoking is utilized as a coping mechanism, and/or perceived as helpful by patients N=28 total, 12 internists, 16 psychiatrists |

Internist:

I think the main challenge is if-- there is a physical addiction for people with mental health issues and people without mental health issues. There is sometimes, or oftentimes, a nicotine addiction. Okay, so that’s already there. But the challenge with mentally impaired people is they have made that connection mentally that when they smoke they feel better. They feel calm. And I think it goes against their common sense to say, “Well, let me take away the cigarette,” because what they hear is, “Let me take away the thing that’s your friend. Let me take away the thing that makes you feel better. Let me take away your comfort stick.” Which would be their cigarette. I think that’s the hardest thing. Psychiatrist: The idea of taking away something that someone uses as a “crutch,” the only thing that gives them pleasure, can seem like it’s punitive or cruel even though it’s in the patient’s interest… The addictive process itself is so difficult to break with tobacco especially, the withdrawal phenomenon. The fact that a patient fools themselves to thinking that they need a cigarette to feel better when it’s really to treat their own withdrawal from the previous cigarette. They’re on this continuous loop of self-medicating their own withdrawal from tobacco. |

| Patient does not have a motivation to quit or is unwilling to try N=19 total, 11 internists, 8 psychiatrists |

Internist:

I try to assess where they are, because if they’re not engaged, then I think there’s really not a chance that they’re going to be successful. Psychiatrist: Oftentimes, the motivation to quit smoking isn’t particularly high because their overall kind of self-care, in terms of health, isn’t terrific. So yeah. So there’s a number of challenges there. |

| Inability to use certain smoking cessation medications due to interactions or side effects with other patient medications N=14 total, 7 internists, 7 psychiatrists |

Internist:

People with mental illness, they’re already on multiple medication for anti-psychotic or anti-depressant or anti-anxiety or any of them. And given the chemical medicines which I’m going to introduce, some always worry about drug-drug interactions. That’s number one. Psychiatrist: So if a person, for example, has bipolar disorder, then they’re more likely to get Chantix because I don’t want to give them-- I don’t want to add an anti-depressant like Bupropion into their treatment regimen. |

| Differences between patients with and without MI (Internists only) | |

| Rate of smoking is greater among patients with and without MI N=15 internists |

Internist: [Patients with a mental illness] have a bigger problem with smoking, absolutely. Especially bipolar and depressives. |

| Provider approach to treatment is different for patients with and without MI (e.g., different medications or counseling) N=15 internists |

Internist: Yes. Depends on what mental illness they have. It’s a little bit different. The conversation’s a bit different with, for instance, with people with major depression, people with obsessive-compulsive. It depends on their underlying mental illness. My conversation’s a little more cautious, and it’s tailored to individual mental health patients. |

| The level of difficulty to quit is greater for patients with and without MI N=11 internists |

Internist: I think this is difficult for the patients with mental illness to quit smoking. Smoking is difficult to quit anyway. This is one of the addictions which is so difficult, and I think with mental illness is a bigger challenge. Sometimes I think they don’t realize. I think one of their problems is it doesn’t go in their head that what they are doing for themselves. I think it’s understanding, especially in the general population and more in the mental illness, that they don’t get it. So we have to work extra hard for those patients. |

Fifteen internists noted a perception that the rate of smoking among patients with mental illness is greater than patients without mental illness. An equal number, 15 internists, said they approached smoking cessation treatment differently for patients with and without mental illness. This included tailoring conversations towards patient’s mental health needs, possibly resulting in different medication/treatment options. Lastly, 11 internists said patients with mental illness often faced greater difficulty quitting than those without mental illness, such as breaking away from the “self-medicating” perception of cigarettes.

DISCUSSION

Prescribing rates for all smoking cessation medications remained low during our 14-year study period, among all smokers. Nearly 98% of smokers from 2005–2019 were not prescribed varenicline and/or NRT – first line treatments for tobacco use disorder – across smokers without mental illness, smokers with any mental illness, and smokers with serious mental illness. Bupropion was slightly more commonly prescribed, particularly among smokers with mental illness, but our data do not allow us to determine whether it was prescribed for smoking cessation, depression, weight loss, or a combination. The proportion of people with serious mental illness prescribed bupropion increased over the study period, a trend potentially driven by the 2009 PORT guidelines recommending bupropion with or without NRT for smokers with serious mental illness.(32) General internists and psychiatrists in our qualitative convenience sample reported offering smoking cessation pharmacotherapy to patients with and without mental illness. This disparity between practices reported in the qualitative interviews and MEPS results may be due to lack of representativeness of the qualitative sample – through under-representation of clinicians practicing in community settings that require documentation of tobacco use in EHRs.(33) Additionally, it may be due to patient’s lack of readiness to quit, their interest in quitting without pharmacotherapy, their ability to receive NRT outside of our data source without a prescription (e.g. over-the-counter or through Quitlines),(34) and/or providers underestimating patient’s readiness to quit, which has been demonstrated in other studies.(21, 22, 24, 25)

In 2009, the FDA added black box warnings to varenicline and bupropion to warn of risks of serious side effects on suicidal thoughts, depression, or hostility.(35) However, these warnings were removed from both medications in 2016 for patients quitting smoking due to a review of large clinical trials showing the mental health side effects of these medications were much lower than initially suspected;(17, 36) the label remains on bupropion for patients using it as an antidepressant drug. Studies examining trends in varenicline and bupropion use among individuals who were advised to quit smoking or made quit attempts found broadly similar trends to those in the present study, with a decline in varenicline use around the black box warning and fairly stable trends in bupropion prescribing.(37, 38) However, our findings demonstrate an uptick in smokers with serious mental illness prescribed bupropion following the removal of black box warnings. Some providers interviewed reported they are hesitant to prescribe varenicline for smokers with serious mental illness due to side effects patients have reported or potential contraindications with medications the patient is taking, but none reported that these medications are clinically inappropriate for smokers with any mental illness.

Another major influence on the receipt of prescribed cessation medications is insurance coverage, which was emphasized by physicians interviewed in this study. More comprehensive insurance coverage of smoking cessation treatment is associated with increased cessation medication uptake and successful cessation rates.(39–41) Coverage for tobacco cessation improved as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA);(42, 43) however, our results do not suggest increases in the prescription of smoking cessation medications following ACA enactment. Evidence indicates there are substantial barriers to more effective coverage like high cost-sharing and prior authorization requirements for treatment, which are widespread in commercial insurers, Medicare, and state Medicaid programs.(44, 45) Further removing insurance barriers like copays, prior authorization, and limits on quit attempts would likely improve access and outcomes related to smoking cessation treatment.(39–41)

Prior research suggests that provider-level factors, like beliefs on tobacco use and behavioral health and knowledge of clinical guidelines, have an important impact on cessation medication delivery.(46, 47) Providers may be uncomfortable engaging patients they perceive are smoking as a coping mechanism and/or not ready to quit,(21, 24, 48) which was the most frequently mentioned barrier to cessation treatment noted by general internists and psychiatrists in our study. Providers should offer pharmacotherapy to patients regardless of perceived quit readiness because medication can reduce cravings and withdrawal, which may shift a patient’s willingness to quit.(49) Additionally, providers may feel more comfortable relating consequences of smoking to medical issues that arise during a visit (e.g. wound healing, cancer screening). This strategy may allow clinicians to incorporate smoking cessation counseling into every visit, despite time constraints or not being a patient’s longitudinal provider.(50)

At the system level, electronic decision support systems could incorporate more nuanced approaches for patients interested in quitting but who have not yet set a quit date, such as including pharmacotherapy options for patients prior to quitting, or including a follow up timeframe. It could also explicitly indicate that the known patient mental health diagnoses are not contra-indications to smoking cessation medications, a barrier noted by general internists and psychiatrists in our study, thereby leveraging real-time information from the EHR for provider education. In addition, availability of formulary information and costs for cessation medications may further address potential prescribing barriers.

LIMITATIONS

These findings should be considered with limitations. First, mental illness status was determined through medical records, which may be imprecise. Second, we are unable to determine whether bupropion was prescribed to treat depression, for weight loss, or for smoking cessation. Third, MEPS only captures the prescription of medications. NRT can be obtained outside of a prescription, so we are likely under-capturing the use of NRT. Additionally, MEPS cannot reliably measure the receipt of behavioral counseling for smoking cessation, so we focused on medications which are a critical component of cessation treatment. Future work is needed to examine receipt of medication alongside behavioral therapy. Lastly, qualitative results may be subject to social desirability bias, with providers more likely to report they prescribed cessation medications than they do in practice.

CONCLUSION

Cessation pharmacotherapy for smokers remained vastly under-prescribed across all groups, with at least 83% of smokers with or without mental illness not receiving varenicline, NRT, and/or bupropion during our 14-year study period. Provider- and system-level strategies incorporating evidence-based smoking cessation treatment into standard workflows are needed to improve delivery of smoking cessation medication for people with and without mental illness.

Highlights:

Nearly 98% of smokers from 2005–2019 were not prescribed varenicline and/or nicotine replacement therapy – first line treatments for tobacco use disorder – across smokers without mental illness, smokers with any mental illness, and smokers with serious mental illness.

Only 55% of general internists and 60% of psychiatrists interviewed reported that they offered cessation counseling for smoking. The most common barrier to providing smoking cessation treatment noted by general internists (60%) and psychiatrists (80%) was patient’s perception of smoking as a coping mechanism for their mental illness.

System and provider-level strategies focused on incorporating evidence-based smoking cessation treatment into standard workflows are needed to improve delivery of smoking cessation medication for people with and without mental illness.

Acknowledgments:

Sarah White had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures and acknowledgments:

There are no potential conflicts of interest to report for the authors of this paper. Grant support came from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the supporting grant number is P50MH115842.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lipari RN and Van Horn S: Smoking and Mental Illness Among Adults in the United States, in The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430654/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith PH, Mazure CM, and McKee SA, Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control, 2014. 23(e2): p. e147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snell M, Harless D, Shin S, et al. , A longitudinal assessment of nicotine dependence, mental health, and attempts to quit Smoking: Evidence from waves 1–4 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Addictive Behaviors, 2021. 115: p. 106787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasheen C, Hedden SL, Forman-Hoffman VL, et al. , Cigarette smoking behaviors among adults with serious mental illness in a nationally representative sample. Annals of Epidemiology, 2014. 24(10): p. 776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forman-Hoffman VL, Hedden SL, Miller GK, et al. , Trends in cigarette use, by serious psychological distress status in the United States, 1998–2013. Addict Behav, 2017. 64: p. 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanton CA, Keith DR, Gaalema DE, et al. , Trends in tobacco use among US adults with chronic health conditions: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2005–2013. Preventive medicine, 2016. 92: p. 160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickerson F, Schroeder J, Katsafanas E, et al. , Cigarette Smoking by Patients With Serious Mental Illness, 1999–2016: An Increasing Disparity. Psychiatr Serv, 2018. 69(2): p. 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. , Premature Mortality Among Adults With Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, 2015. 72(12): p. 1172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, et al. , Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res, 2014. 48(1): p. 102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, et al. , Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016. 3: p. Cd008286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, et al. , Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013. 2013(5): p. Cd009329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Coppola EL, et al. , Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA, 2021. 325(3): p. 280–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartmann-Boyce J, Hong B, Livingstone-Banks J, et al. , Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 6(6): p. Cd009670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babb S MA, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A, Quitting Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2017. 65(52): p. 1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General: Interventions for Smoking Cessation and Treatments for Nicotine Dependence, in Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General Washington, DC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555596/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. , Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 2014. 311(2): p. 145–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. , Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet, 2016. 387(10037): p. 2507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts E, Eden Evins A, McNeill A, et al. , Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Addiction, 2016. 111(4): p. 599–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evins AE, Korhonen T, Kinnunen TH, et al. , Prospective association between tobacco smoking and death by suicide: a competing risks hazard analysis in a large twin cohort with 35-year follow-up. Psychological Medicine, 2017. 47(12): p. 2143–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marynak K VB, Tetlow S, et al. , Tobacco Cessation Interventions and Smoke-Free Policies in Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2018. 67: p. 519–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheals K, Tombor I, McNeill A, et al. , A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals’ attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction, 2016. 111(9): p. 1536–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Himelhoch S, Riddle J, and Goldman HH, Barriers to Implementing Evidence-Based Smoking Cessation Practices in Nine Community Mental Health Sites. Psychiatric Services, 2014. 65(1): p. 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeder SA and Morris CD, Confronting a Neglected Epidemic: Tobacco Cessation for Persons with Mental Illnesses and Substance Abuse Problems. Annual Review of Public Health, 2010. 31(1): p. 297–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malone V, Harrison R, and Daker-White G, Mental health service user and staff perspectives on tobacco addiction and smoking cessation: A meta-synthesis of published qualitative studies. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2018. 25(4): p. 270–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Twyman L, Bonevski B, Paul C, et al. , Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open, 2014. 4(12): p. e006414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, et al. , Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 2014. 348: p. g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu NH, Wu C, Pérez-Stable EJ, et al. , Longitudinal Association Between Smoking Abstinence and Depression Severity in Those With Baseline Current, Past, and No History of Major Depressive Episode in an International Online Tobacco Cessation Study. Nicotine Tob Res, 2021. 23(2): p. 267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratschen E, Britton J, Doody GA, et al. , Tobacco dependence, treatment and smoke-free policies: a survey of mental health professionals’ knowledge and attitudes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2009. 31(6): p. 576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Home Page. Rockville, MD, 2021. https://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/. Accessed Sept 23 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. , Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2003. 60(2): p. 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MedPanel. Waltham, MA. www.medpanel.com. Accessed August 18 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. , The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull, 2010. 36(1): p. 71–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamal A, Dube SR, and King BA, Tobacco Use Screening and Counseling During Hospital Outpatient Visits Among US Adults, 2005–2010. Prev Chronic Dis, 2015. 12: p. E132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.North American QuitLine Consortium. What is a Quitline. Phoenix, AZ. https://www.naquitline.org/page/whatisquitline. Accessed Nov 1 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Food and Drug Administration. Public Health Advisory: FDA Requires New Boxed Warnings for the Smoking Cessation Drugs Chantix and Zyban. 2009. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm169988.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Food and Drug Administration. FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-revises-description-mental-health-side-effects-stop-smoking. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah D, Shah A, Tan X, et al. , Trends in utilization of smoking cessation agents before and after the passage of FDA boxed warning in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2017. 177: p. 187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarlenski M, Hyon Baik S, and Zhang Y, Trends in Use of Medications for Smoking Cessation in Medicare, 2007–2012. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2016. 51(3): p. 301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greene J, Sacks RM, and McMenamin SB, The impact of tobacco dependence treatment coverage and copayments in Medicaid. Am J Prev Med, 2014. 46(4): p. 331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reda AA, Kotz D, Evers SM, et al. , Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012(6): p. Cd004305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kostova D, Xu X, Babb S, et al. , Does State Medicaid Coverage of Smoking Cessation Treatments Affect Quitting? Health services research, 2018. 53(6): p. 4725–4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maclean JC, Pesko MF, and Hill SC, PUBLIC INSURANCE EXPANSIONS AND SMOKING CESSATION MEDICATIONS. Economic Inquiry, 2019. 57(4): p. 1798–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McAfee T, Babb S, McNabb S, et al. , Helping smokers quit--opportunities created by the Affordable Care Act. The New England journal of medicine, 2015. 372(1): p. 5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kofman M, Dunton K, and Senkewicz M: Implementation of tobacco cessation coverage under the Affordable Care Act: Understanding how Private Health Insurance Policies Cover Tobacco Cessation Treatments. Washington, DC, Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, 2012. http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/pressoffice/2012/georgetown/coveragereport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiGiulio A, Jump Z, Babb S, et al. , State Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Cessation Treatments and Barriers to Accessing Treatments - United States, 2008–2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 2020. 69(6): p. 155–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson JL, Malchy LA, Ratner PA, et al. , Community mental healthcare providers’ attitudes and practices related to smoking cessation interventions for people living with severe mental illness. Patient Education and Counseling, 2009. 77(2): p. 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prochaska JJ, Smoking and Mental Illness — Breaking the Link. New England Journal of Medicine, 2011. 365(3): p. 196–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gentry S, Craig J, Holland R, et al. , Smoking cessation for substance misusers: A systematic review of qualitative studies on participant and provider beliefs and perceptions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2017. 180: p. 178–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barua RS, Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, et al. , 2018 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Tobacco Cessation Treatment. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2018. 72(25): p. 3332–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rigotti NA, Kruse GR, Livingstone-Banks J, et al. , Treatment of Tobacco Smoking: A Review. JAMA, 2022. 327(6): p. 566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]