Abstract

Objectives:

A perception derived from cross-sectional studies of small SLE cohorts is that there is a marked discrepancy between antinuclear antibody (ANA) assays, which impacts on clinician’s approach to diagnosis and follow-up. We compared three ANA assays in a longitudinal analysis of a large international incident SLE cohort retested regularly and followed for five years.

Methods:

Demographic, clinical, and serological data was from 805 SLE patients at enrolment, year 3 and 5. Two HEp-2 indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA1, IFA2), an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and SLE-related autoantibodies were performed in one central laboratory. Frequencies of positivity, titres/units, and IFA patterns were compared using McNemar, Wilcoxon, and kappa statistics, respectively.

Results:

At enrolment, ANA positivity (≥1:80) was 96.1% by IFA1 (median titre 1:1280 [IQR 1:640–1:5120]), 98.3% by IFA2 (1:2560 [IQR 1:640–1:5120]), and 96.6% by ELISA (176.3AU [IQR 106.4–203.5]). At least one ANA assay was positive for 99.6% of patients at enrolment. At year 5, ANA positivity by IFAs (IFA1 95.2%; IFA2 98.9%) remained high, while there was a decrease in ELISA positivity (91.3%, p<0.001). Overall, there was >91% agreement in ANA positivity at all time points and ≥71% agreement in IFA patterns between IFA1 and IFA2.

Conclusion:

In recent-onset SLE, three ANA assays demonstrated commutability with a high proportion of positivity and titres/units. However, over five years follow-up, there was modest variation in ANA assay performance. In clinical situations where the SLE diagnosis is being considered, a negative test by either the ELISA or HEp-2 IFA may require reflex testing.

Keywords: Antinuclear antibodies, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, longitudinal, performance, immunoassays, ELISA

INTRODUCTION

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing has an integral approach to accurately diagnose and classify SLE (1). A systematic literature review and meta-regression of indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) reported high sensitivity (97.8%) for SLE diagnosis at a titer of ≥ 1:80 (2). This presaged the decision to include a positive ANA at that titer on HEp-2 cell IFA “or an equivalent positive test on other diagnostic platforms” occurring at least once as an entry criterion for the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology (EULAR/ACR) SLE Classification Criteria (3, 4).

Previous longitudinal examinations of ANA and SLE-related autoantibodies suggest that a patient’s ANA status can change from positive to within the normal range and vice versa during the disease course (2, 5–16). However, these studies have typically been limited to small, single center cohorts with incomplete disease characterization, short follow-up, and/or using outdated assays with conflicting results. The factors influencing changes in ANA have also not been thoroughly studied. Taken together, this has left clinicians with uncertainty about the value and interpretation of ANA testing in making a diagnosis of, or classifying, SLE. In addition, the clinically actionable value of repeat ANA testing once a diagnosis of SLE is established requires clarification (17, 18).

Much of the confusion and debate on the clinical utility of ANA testing in SLE is related to reported variations in HEp-2 IFA assay performance in cross-sectional cohorts (19–22), and some have questioned whether the ANA IFA should continue to be the “gold standard” screening test (23–25). For instance, in a cross-sectional study, Pisetsky et al. tested the same sera using different ANA assays (e.g., IFA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], and multiplex bead assay) (21) and reported that the frequency of an ANA test within normal reference range in SLE patients with disease duration ranging from 0.1 to 33.4 years varied from 4.9%–22.3%. Further, it has been proposed that the IFA could be replaced or complemented by newer generation solid phase multi-analyte immunoassays (SPMAI) such as ELISA and/or addressable laser bead immunoassays (ALBIA) (24–26). A recent systematic review and meta-regression analysis of ANA testing in >13,000 SLE patients with disease duration ranging from 0–17 years reported that only ~2.5% of these patients had an IFA ANA <1:80 (2), although a higher prevalence of ANA within the normal reference range has been reported in other cohorts including the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) Inception Cohort (6.2% were <1:160 at inception) (27).

The primary goal of this study was to gain a more thorough understanding of ANA detection and its clinical value by comparing the performance of three currently available ANA assays in a longitudinal analysis (at least 5 years) of a large multinational SLE inception cohort.

METHODS

Study Population

Between 1999 and 2011, SLICC (https://sliccgroup.org) (28) enrolled 1827 patients fulfilling the 1997 Updated ACR SLE Classification Criteria for definite SLE (29) within 15 months of diagnosis from 31 medical centres in 11 countries. Sera, clinical and demographic data were collected at enrolment and annually thereafter. Of the 1827 patients, 1432 (78.4%) were followed for ≥4 years; of these 1432 patients, we included the 805 patients who provided an enrolment and two additional serum samples within five years of enrolment, with the third sample being ≥4 years after enrolment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site. Permission from the SLICC Biological Material and Data Utilization Committee was obtained to access the required data and biobanked serum samples.

ANA and Autoantibody Testing

Aliquots of sera were obtained from the 805 patients in the SLICC Inception Cohort at three time points: 1) enrolment (sample #1), 2) two to four years after enrolment (sample #2), and 3) four to 10 years after enrolment (sample #3). Hereafter, samples #1 – 3 are referred to as enrolment, year 3, and year 5, respectively. Samples were stored at −80°C until required for immunoassays and analyzed centrally at MitogenDx Laboratory (Calgary, Canada). Three US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved and Conformitè Europëenne (CE) marked ANA tests were used, including two HEp-2 IFA, IFA1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA) and IFA2 (NovaLite, Werfen, San Diego, USA), and an ELISA (Werfen, San Diego, USA). In accordance with the manufacturers’ directions, a positive test was defined as a titer of ≥1:80 for IFA1 and IFA2 (titre <1:80 is considered normal range) and ≥20 absorbance units (AU) for ELISA. IFA1, IFA2, and ELISA were tested on the full patient cohort (n=805) sera from all three time points. IFA results (titres and patterns) were initially read by an automated digital IFA microscope and then checked manually by a technologist with 30 years of experience. ANA IFA patterns were classified according to the new International Consensus on ANA Patterns recommendations (http://www.anapatterns.org/index.php) (30). Quality control was performed by repeating all ANA results that were within the normal range and a random selection of ANA-positive samples to ensure inter-test reliability. SLE-related autoantibodies (Supplemental Table 1) were also performed on each patient at enrolment, year 3 and 5.

Clinically Defined Samples

Demographic and clinical data (Supplemental Table 2) at enrolment included age, sex, disease duration, race/ethnicity, nephritis (fulfilling the ACR criterion for renal disease or based on a renal biopsy), ACR Classification Criteria, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index – 2000 (SLEDAI-2K), SLICC/ACR Damage Index (SDI), and medication use (current and ever use of glucocorticoids, antimalarials, and immunosuppressives, including biologics). We also collected longitudinal data on nephritis, SLEDAI-2K, SDI, and medications.

Statistical analysis

Demographic, clinical, and serological characteristics were described using summary statistics. Changes over time in demographic and clinical features were described using differences in means or proportions, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). As our analysis used a subgroup of the larger SLICC cohort based on sera availability, we compared the enrolment characteristics of the 805 patients included in this study with the 627 patients who were followed for ≥4 years but were not included as three serial serum samples were unavailable. We also compared the characteristics of the 781 patients providing the third serum sample 4–7 years after enrolment with the 24 patients providing the third serum sample 8–10 years after enrolment.

We assessed the frequency of ANA positivity and titre at each time point. Using the paired McNemar’s test, we calculated changes in ANA positivity between enrolment and year 5 for each test and the inter-test agreement in ANA positivity between tests at each time point. A histogram with a curve of best fit line was used to plot the changes in distribution of titres and units over time were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired data. We examined the frequency of each ANA pattern and how many patients retained their HEp-2 IFA pattern over the three serial samples. ANA patterns were further categorized into three groups: 1) isolated nuclear (AC 1–14, 29), 2) isolated cytoplasmic and/or mitotic (CMP, AC 15–28), and 3) mixed nuclear and CMP patterns. Agreement between IFA1 and IFA2 ANA titres and patterns was assessed using the weighted and unweighted kappa (к) statistic, respectively. Established SLE-related autoantibody profiles of patients with an ANA result within the normal range on IFA1, IFA2, or ELISA alone, on two of three assays, and on all three assays at enrolment and year 5 were examined to understand which autoantibodies were not being captured by the ANA screening assays. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Study Population

Eight hundred and five SLE patients were included. The mean time from disease diagnosis to enrolment was 0.58 years (standard deviation [SD] 0.49); the mean time between the enrolment and the year 3 sample was 2.8 years (SD 0.8) and between the enrolment and the year 5 sample was 5.0 years (SD 1.1). Patients had a mean age at diagnosis of 35.2 years (SD 13.6), 88.7% (714/805) were female and 47.7% (384/805) were of race/ethnicity other than White (Table 1). From enrolment to year 5, the prevalence of lupus nephritis increased by 7.7% [95%CI: 5.7%, 9.7%], mean SLEDAI-2K decreased by 2.3 [95%CI: 1.9, 2.7], and mean SDI increased by 0.52 [95%CI: 0.43, 0.62]. There were significantly fewer patients on glucocorticoids (69.6% vs 56.8%, difference −12.8% [95%CI: −16.5%, −9.1%]) and more patients on antimalarials (70.1% vs 79.4%, difference 9.3% [95%CI: 5.9%, 12.7%]) or immunosuppressants (41.0% vs 50.8%, difference 9.8% [95%CI: 6.1%, 13.5%]). The frequency of most SLE-related autoantibodies decreased at year 5.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at enrolment and year 5 (n=805)

| Characteristic | Enrolment | Year 5 | Difference1 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and Clinical | ||||

| Mean age at dx, yrs (SD) | 35.2 (13.6) | |||

| Female, % | 88.7 | |||

| Mean disease duration, yrs (SD) | 0.58 (0.49) | |||

| Mean number of ACR Criteria without ANA (SD) | 3.9 (1.0) | |||

| Ethnicity, % | ||||

| Asian | 24.3 | |||

| African | 13.5 | |||

| White | 52.3 | |||

| Hispanic | 6.3 | |||

| Other ethnicities2 | 3.5 | |||

| Nephritis3 | 28.9 | 36.6 | 7.7 (5.7, 9.7) | |

| Mean total SLEDAI-2K (SD)4 | 5.4 (5.3) | 3 (3.5) | −2.3 (−2.7, −1.9) | |

| Mean total SDI (SD)5 | 0.34 (0.74) | 0.86 (1.25) | 0.52 (0.43, 0.62) | |

| Medications | ||||

| Current, % | ||||

| Glucocorticoids | 69.6 | 56.8 | −12.8 (−16.5, −9.1) | |

| Antimalarials | 70.1 | 79.4 | 9.3 (5.9, 12.7) | |

| Immunosuppressants | 41.0 | 50.8 | 9.8 (6.1, 13.5) | |

| Ever, % | ||||

| Glucocorticoids | 81.5 | 87.3 | 5.8 (4.1, 7.6) | |

| Antimalarials | 76.6 | 91.1 | 14.4 (11.9, 17) | |

| Immunosuppressants | 43.9 | 66.3 | 22.5 (19.5, 25.5) | |

| Autoantibodies, % | ||||

| dsDNA6 | 34.2 | 29.1 | −5.1 (−8.7, −1.6) | |

| Ribosomal P | 24.3 | 20 | −4.3 (−7.8, −0.9) | |

| Ro52/TRIM21 | 37.5 | 37.4 | −0.1 (−3.4, 3.2) | |

| SSA/Ro60 | 42.5 | 42 | −0.5 (−3.7, 2.7) | |

| SSB/La | 20.7 | 16.3 | −4.5 (−7.5, −1.5) | |

| Sm | 22.7 | 14.7 | −8.1 (−11.1, −5.0) | |

| U1RNP | 28.2 | 23 | −5.2 (−8.5, −2.0) | |

| Histones | 31.3 | 22.7 | −8.6 (−12.1, −5.0) | |

| Cardiolipin IgG/IgM7 | 20.5 | 16.4 | −4.1 (−7.7, −0.6) | |

| β2GP1 IgG/IgM7 | 19.8 | 12.9 | −6.9 (−9.8, −4) | |

| Lupus anticoagulant8 | 20.6 | 16.7 | −3.9 (−9.8, 2) | |

Abbreviations: ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; β2GP1, β2-glycoprotein-1; CI, confidence interval; dx, diagnosis; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; IgG/M, immunoglobulin G/immunoglobulin M; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; SD, standard deviation; SLEDAI-2K, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index-2000; SDI, SLICC Damage index; Sm, Smith; TRIM21, Tripartite Motif Protein (TRIM) 21; yrs, years.

Difference between enrolment and year 5 visit;

Other ethnicities include: Native North American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islanders

Nephritis defined as fulfilling the ACR criterion for renal disease or if a renal biopsy was performed prior to cohort entry

Complete data available for n=793 patients

Complete data available for n= 380 as the disease needs to be present for at least 6 months before the SDI can be calculated.

Complete data available for n=798 patients

Complete data available for n= 800

Complete data available for n=282

The enrolment characteristics of the 805 patients included in our study were similar to the 627 patients who provided ≥4 years of data but did not have three available serial serum samples (Supplemental Table 3). However, there was a higher proportion of Asian (18.8% (95%CI: 15.3, 22.2) and lower proportion of Hispanic participants (−20.6% (95%CI: −24.5, −16.8) in the study cohort compared to the cohort not providing serial samples. The enrolment characteristics of the 781 patients whose year 5 sample was collected between years 4 and 7 were similar to the 24 patients whose year 5 sample was collected between years 8 and 10 (Supplemental Table 4).

ANA Positivity and Agreement Among Different Assays Over Time

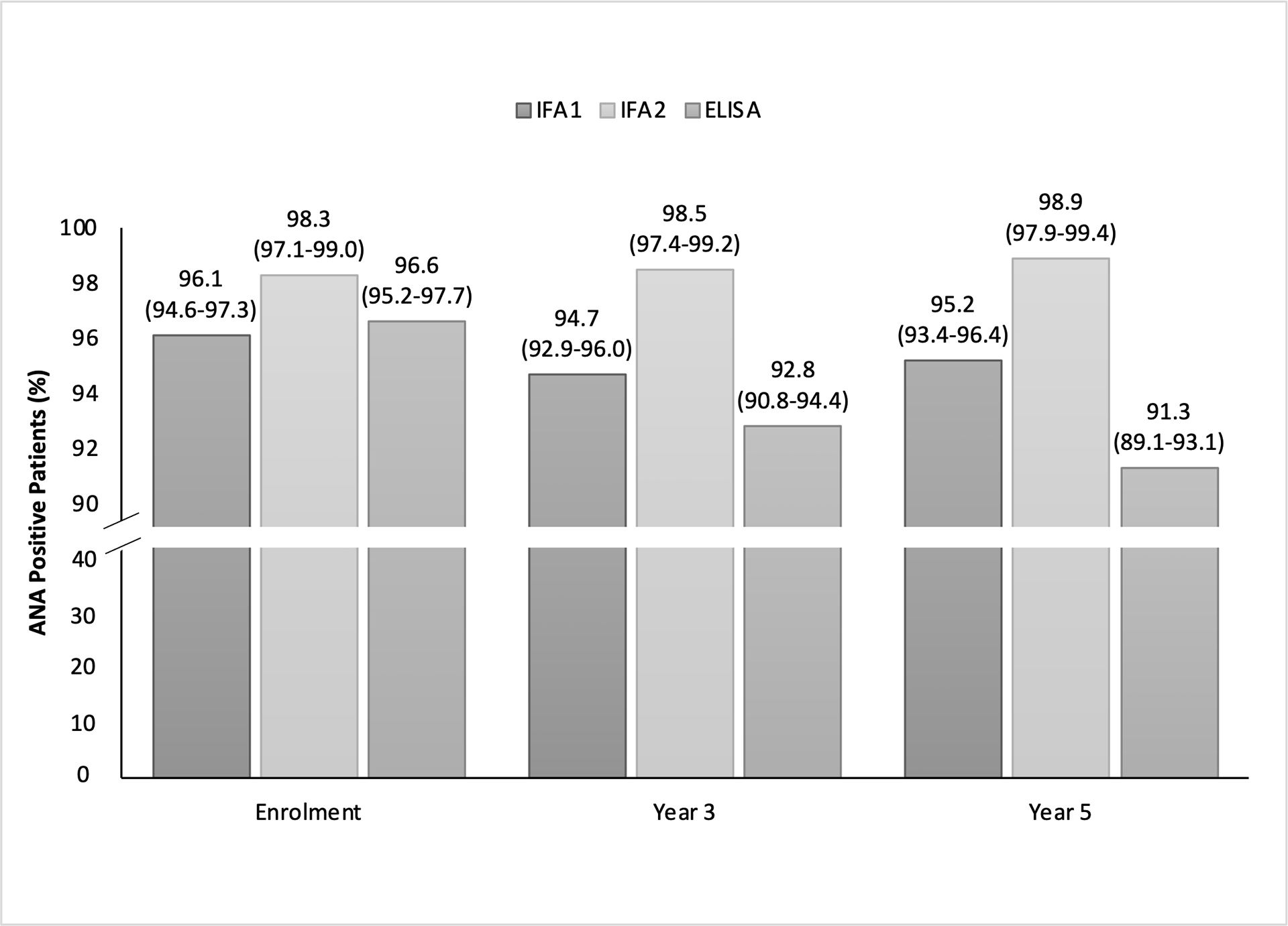

At enrolment, the frequency of ANA positivity by IFA1, IFA2, and ELISA was high (96.1% [95%CI: 94.6–97.3%], 98.3% [95%CI: 97.1–99.0%], and 96.6% [95%CI: 95.2–97.7]), respectively) (Figure 1) and 99.6% (802/805) of patients had ≥1 positive ANA of ≥1:80. An additional five (0.6% incremental effect), three (0.5%), and two patients (0.4%) at enrolment, year 3, and year 5 visits, respectively, would be ANA positive on the ELISA, but within the normal range for both IFA1 and IFA2. There was no significant change in ANA positivity at enrolment compared to year 5 for IFA1 or IFA2. However, ANA positivity by ELISA decreased significantly from enrolment to year 5 (difference −5.3% (95%CI: −7.4, −3.3), p<0.001) such that 91.3% (735/805) of patients were positive by year 5. Notably, 1.2% (10/805) of subjects were within the normal range at all three time points by ELISA compared to 0.9% (7/805) by IFA1 and 0.1% (1/805) by IFA2. At all time points, no patients were classified as being within the normal range if all three of the assays were considered.

Figure 1.

ANA positivity among IFA1 (n=805), IFA2 (n=805) and ELISA (n=805) at enrolment, year 3 and year 5. There is a break in the y-axis between 40% and 90% to enhance the readability of the graph from 90-100%.

Overall, the inter-test agreement for positivity between any pair of assays was >91% (Table 2). In cases where there was disagreement between IFA1 and IFA2, there was significant asymmetry (McNemar’s test) such that most disagreements were due to more patients with an ANA by IFA1 within the normal range and a positive ANA by IFA2 (−IFA1/+IFA2) rather than a positive ANA by IFA1 and an ANA within the normal range by IFA2 (+IFA1/−IFA2) for all three time points (Supplemental Table 5). Regarding the disagreements between IFA1 and ELISA, there was no significant asymmetry until year 5 when there were more cases of disagreement due to +IFA1/−ELISA compared to −IFA1/+ELISA. For disagreements between IFA2 and ELISA, there was significant asymmetry across all time points with more cases of +IFA2/−ELISA than −IFA2/+ELISA.

Table 2.

ANA inter-test percentage agreement among IFA1 (n=805), IFA2 (n=805), and ELISA (n=805)

| Enrolment (%) | Year 3 (%) | Year 5 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFA1 | IFA2 | IFA1 | IFA2 | IFA1 | IFA2 | |

| IFA2 | 96.4% (94.9 –97.6) | 95.2% (93.4–96.5) | 95.5% (93.9–96.8) | |||

| ELISA | 94.8% (93.0–96.2) | 95.7% (94.0–97.0) | 91.2% (89.0–93.0) | 92.5% (90.5–94.3) | 91.4% (89.3–93.3) | 91.2% (89.0–93.0) |

Abbreviations: ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IFA; indirect immunofluorescence assay.

ANA Titres/Units Among Different Assays Over Time

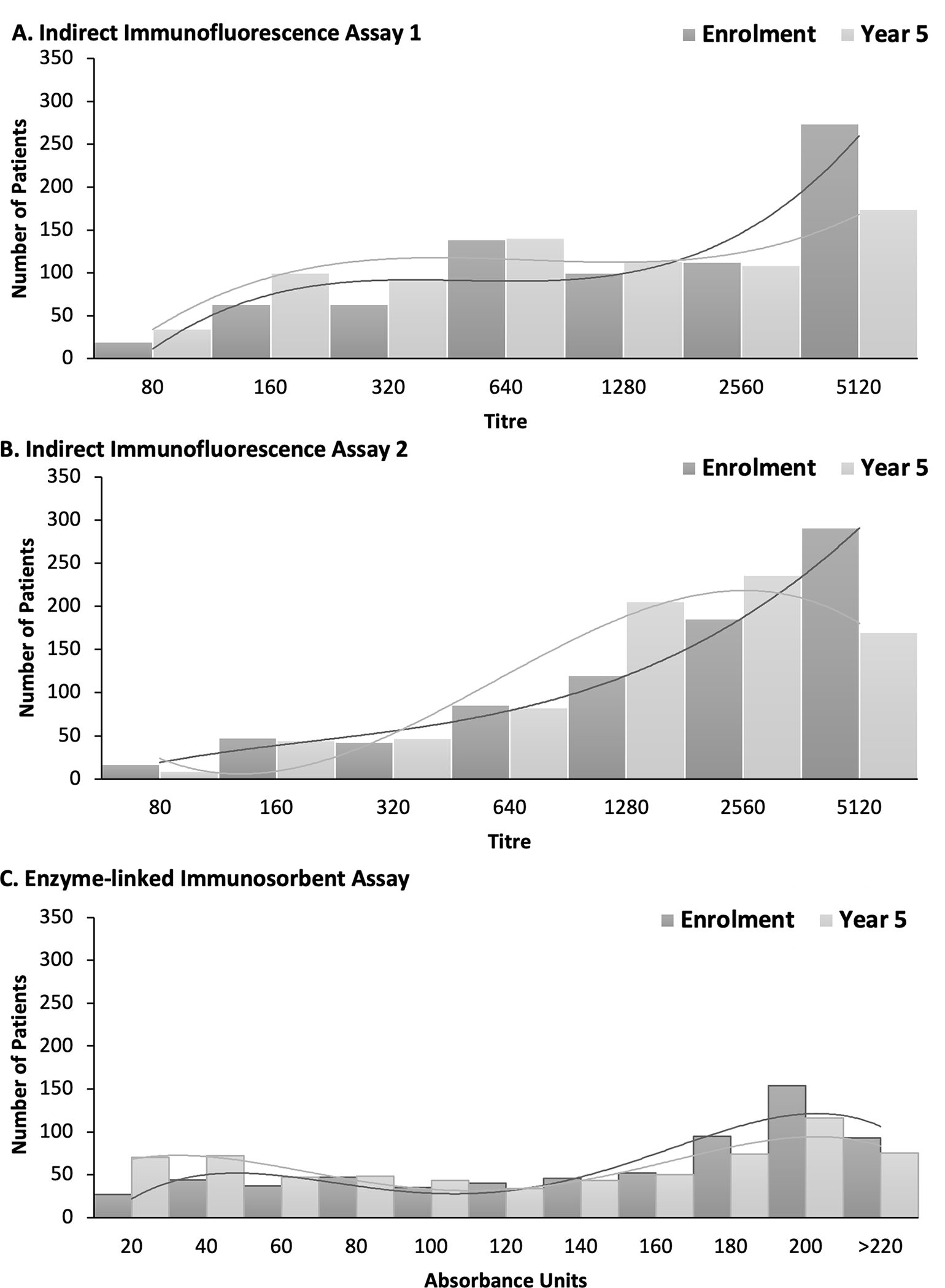

At enrolment, the median ANA titre/unit for IFA1, IFA2, and ELISA were 1:1280 (interquartile range (IQR) 1:640–1:5120), 1:2560 (IQR 1:640–1:5120), and 176.3 AU (IQR 106.4 AU-203.5 AU), respectively (Figure 2). The distribution of ANA titres was skewed to the left for all assays at enrolment (higher proportion of patients with very high ANA titres). Only a small proportion had ANA titres of 1:80 to 1:160 at enrolment (IFA1 10.4% [84/805] and IFA2 8.1% [65/805]). The median titres/units at year 5 were significantly lower compared to enrolment for IFA1 (1:640 (IQR 1:320–1:2560), paired Wilcoxon signed rank p<0.0001, a change in one dilution step) and ELISA (157.3 CU (IQR 66.14 CU- 200.65 CU), p<0.0001)). There was good agreement between IFA1 and IFA2 titres at enrolment, 84.9% (95%CI: 82.2–87.3) agreement, k=0.49 (95%CI: 0.45–0.53); at year 3, 81.1% (95%CI: 78.2–83.7%) agreement, k=0.39 (95%CI: 0.35–0.43%); and at year 5, 82.0% (95%CI: 79.1–84.6%) agreement, k=0.41 (95%CI: 0.37–0.45%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of ANA titres at enrolment and year 5 visit for A) indirect immunofluorescence 1 (IFA1) (n=805), B) IFA2 (n=805) and C) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (n=805). Lines represent the curve of best fit.

ANA Patterns Among Different Assays Over Time

The most common ANA IFA pattern was an isolated nuclear staining pattern for IFA1 (62.1%–68.7%) and IFA2 (59.3%–62.1%) at all visits (Table 3). The top three individual IFA patterns for both IFA1 and IFA2 were AC-1 (homogeneous), AC-4 (nuclear fine specked), and AC-5 (nuclear large speckled) (Supplemental Figure 1). There was fair-to-moderate agreement between IFA1 and IFA2 ANA IFA staining patterns at enrolment, (74.0% [95%CI 70.7–77.0] agreement, κ=0.46 [95%CI 0.39–0.53]), year 3, (71.4% [95%CI 68.0–74.6], κ=0.39 [95%CI 0.33–0.46]), and year 5, (71.0% [95%CI 67.7–74.2], κ=0.39 [95%CI 0.33–0.46]).

Table 3.

ANA patterns over time with indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) 1 (n=805) and IFA2 (n=805)

| Pattern | Enrolment n (%) | Year 3 n (%) | Year 5 n (%) | Same ANA Pattern Over 5 years n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFA 1 Patterns | ||||

| Nuclear | 481 (62.1) | 519 (68.1) | 526 (68.7) | 305 (37.9) |

| Cytoplasmic +/− Mitotic | 17 (2.2) | 18 (2.4) | 21 (2.7) | 1 (0.1) |

| Mixed | 276 (35.7) | 225 (29.5) | 219 (28.6) | 81 (10.1) |

| IFA2 Patterns | ||||

| Nuclear | 491 (62.1) | 477 (60.4) | 472 (59.3) | 273 (33.9) |

| Cytoplasmic +/− Mitotic | 9 (1.1) | 6 (0.8) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mixed | 291 (36.8) | 308 (38.8) | 320 (40.2) | 114 (14.2) |

| IFA1 and 2 agreement (k) | ||||

| Agreement (95%CI) | 74.0 (70.7–77.0)* | 71.4 (68.0–74.6)* | 71.0 (67.7–74.2)* | |

| Kappa (95%CI) | 0.46 (0.39–0.53) | 0.39 (0.33–0.46) | 0.39 (0.33–0.46) | |

Abbreviations: ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; IFA; indirect immunofluorescence assay.

p<0.0001 using unweighted kappa (k) statistics.

ANA Patients Within the Normal Range and Seroconversion

At enrolment and year 5, 8 and 20 patients were within normal range by IFA1 & ELISA, 3 and 4 patients by ELISA & IFA2, and 8 and 6 patients by IFA1 and IFA2 (Table 4). When examining the autoantibody profiles of patients whose ANA were within normal range at enrolment or year 5, depending on the assay 38.7%–53.8% had no detectable SLE-related autoantibodies. Anti-Ro52/TRIM21 and anti-SSA/Ro60, the former not detectable by HEp-2 IFA and the latter does not have a clearly established IFA pattern, were the most frequent autoantibodies detected when the ANA test was within normal range. Seroconversion from ANA positive to normal range (titre <1:80) from enrolment to year 5 was observed in 4.8% (39/805) of patients using IFA1, 1.1% (9/805) using IF2, and 8.7% (70/805) using ELISA. The median titre of ANA at enrolment prior to seroconversion was low (IFA1 1:160 [IQR 1:80–1:640]), IFA2 1:320 [IQR 1:160–1:2560], and ELISA 61.5 CU [IQR 20–158]). Among those who were originally anti-dsDNA positive at enrolment (n=273), the frequency of ANA positivity was high at enrolment irrespective of the ANA assay (99.3–100.0%). At year 5, frequency of ANA positivity for these same patients, irrespective of their anti-dsDNA status at year 5, declined slightly using for the IFAs (IFA −2.2%, IFA2 −1.1%) and −4.8% for the ELISA (data not shown).

Table 4.

Autoantibodies detected in patients with an ANA that was within the normal range on IFA1, IFA2, ELISA, either alone, on two or all three assay at enrolment and year 5*

| ELISA | IFA1 | IFA2 | IFA1&ELISA | ELISA and IFA2 | IFA1&IFA2 | All three assays | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Autoantibodies | Enrolment (N=27) | Year 5 (N=70) | Enrolment (n=31) | Year 5 (n=39) | Enrolment (N=14) | Year 5 (N=9) | Enrolment (N=8) | Year 5 (N=20) | Enrolment (N=3) | Year 5 (N=4) | Enrolment (N=8) | Year 5 (N=6) | Enrolment (N=3) | Year 5 (N=3) |

| None detected | 44.4 | 45.7 | 38.7 | 53.8 | 42.9 | 44.4 | 62.5 | 65.0 | 66.7 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| dsDNA1 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ribosomal P | 3.7 | 11.4 | 6.5 | 10.3 | 7.1 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| Ro52/TRIM21 | 11.1 | 21.4 | 22.6 | 20.5 | 21.4 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| SSA/Ro60 | 7.4 | 12.9 | 25.8 | 10.3 | 21.4 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| SSB/La | 7.4 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sm | 3.7 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| U1RNP | 3.7 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Histones | 0.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Patients who were within the normal range for ANA at enrolment are not necessarily the same patients at year 5 and vice versa.

Abbreviations: ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; β2GP1, β2-glycoprotein-1; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, IFA; indirect immunofluorescence assay; IgG/M, immunoglobulin G/immunoglobulin M; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; Sm, Smith; TRIM21, TRIpartite Motif protein (TRIM) 21.

dsDNA was measured at enrolment for only 26 patients on ELISA, 13 on IFA2, and 2 on both who tested within the normal range for ANA

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest longitudinal, multinational study (805 patients and 2415 serum samples) that compared the performance of different ANA assays in a well-characterized inception cohort of SLE patients. Our study was designed to overcome the limitations of prior reports that studied smaller cohorts and were historical and/or cross-sectional in nature. These data are timely given ANA test positivity is an entry criterion for the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for SLE (31, 32). We found that, regardless of the assay, almost all patients with recent onset SLE (802/805) had a positive ANA at enrolment on ≥1 assay, all were ANA-positive on ≥1 assay at least once across the five years, and the mean ANA titres/values were high. However, over the five years, some variation between ANA assay performance was detected, including a statistically significant decrease in ELISA ANA positivity and reduction in titres for IFA1 and ELISA.

It has been suggested that the variation in performance between different ANA assays may be related to differences in laboratory techniques, equipment, inter-observer consistency and reagents (25, 33). However, in our study, all ANAs were performed and interpreted at one central laboratory by a highly experienced (30 years of experience) technician. Even after controlling for the impact of inter-laboratory and inter-observer variation, we still identified some significant inter-assay disagreement. Disagreement between ELISA and IFA is likely primarily due to factors intrinsic to the test platforms themselves. Unlike the IFA, the ELISA contains extracts of cell homogenates augmented by purified proteins derived from native and/or synthetic, recombinant sources (34). The composition of the different ELISA ANA preparations is diverse and dependent on the manufacturer as to which key target autoantigen(s) associated with autoimmune diseases are included and at what concentrations (34). ELISAs may also have decreased detection of ANA because of poor autoantibody binding, as some antigens may also bind to other targets in the same mixture, resulting in a masking effect. Furthermore, many autoantibody targets are components of macromolecular complexes where key epitopes may be hidden or masked (34). A thorough study of the affinity and avidity of the various autoantibodies would add useful understanding to the use of ANA ELISAs.

Prior studies of more established SLE patients reported that as high as 30% have an ANA below the positive threshold (35). Over time, we observed a decrease in ANA positivity with ELISA, a decrease in ANA titres/values with IFA1 and ELISA, and decreased detection of specific autoantibodies. We postulate that factors such as disease activity and medication exposure influence ANA (36–39). However, the extent to which therapeutic interventions can alter ANA production, especially by long-lived plasma cells, remains to be proven, and the expression of other autoantibodies can occur following diagnosis, attributed to epitope spreading continuing despite therapy(39).

Our study addresses important questions raised about the ANA in the 2019 EULAR/ACR SLE classification criteria (3, 4, 40), which require an “ever positive” ANA of ≥ 1:80 by HEp-2 IFA or an equivalent test on another platform as an entry criterion for classification. For example, it is important to note that all subjects had at least one positive ANA at the 1:80 threshold over the five years of follow-up. The new criteria also state that a solid phase assay of at least equivalent performance can be used in place of the HEp-2 IFA, although a precise definition of ‘equivalent performance’ was not specified. Our results show that although some inter-assay disagreement exists between these three assays, >91% of recent-onset SLE patients will have a positive ANA using either HEp-2 IFA or ELISA, although titres decreased by year 5 for IFA1 and the ELISA. As expected from previous reports (20, 41), ELISA had the highest proportion of SLE patients with an ANA within the normal <1:80 reference range, and therefore, the ELISA used as a screening test may benefit from judicious reflex testing to the HEp-2 IFA. In turn, since the HEp-2 IFA can be negative when the ELISA is positive, the reciprocal reflex approach could be considered.

Importantly, consistent with other studies and emerging recommendations on ANA testing (20, 41), we demonstrated that a combination of two different ANA assays reduced the proportion of SLE patients with ANAs in the normal range; particularly when IFA2 was combined with ELISA. A combination of all three assays resulted in no patients who had an ANA within normal range at enrollment and two subsequent follow-up visits. This helps shed light on the question of the value of ANA testing to follow the clinical course of SLE, but more detailed follow-up studies evaluating disease activity and flares at follow-up visits in the context of ANA testing are still required. Health care providers should be aware of the technical issues for ANA assays used in their jurisdictions and recognize that different ANA assays or simply following manufacturer’s recommended reference ranges might not be optimal in applying ANA testing results (42, 43). Additional longitudinal studies comparing other ELISAs and SPMAI such as other multiplex bead immunoassays and emerging ANA technologies are needed.

Our study has some important strengths. To our knowledge, this is the largest review of ANA status in SLE patients with data collected longitudinally and in a protocolized fashion over a mean follow-up of five years. All ANA testing was conducted in an accredited central laboratory with stringent quality control. However, we acknowledge some important limitations. First, there may be a potential selection bias for SLE patients who are ANA positive to be enrolled into the SLICC cohort compared to patients in conventional clinical care. Second, as enrolment could occur up to 15 months after diagnosis (although mean disease duration at enrolment was 0.58 years), most patients had already been exposed to ≥1 immunomodulatory medication by enrolment, which could potentially influence the ANA result. Third, although we showed that demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort subset with three available serum samples were largely similar to the remainder of the cohort, our sample included a larger proportion of Asian and fewer Hispanic participants. While our sample was racially and geographically diverse, it is not known if our findings are generalizable to other SLE cohorts. Fourth, the duration of follow-up, although relatively long at five years, does not capture potential seroconversions or measure assay performance later in the disease. Last, there are >10 different ANA immunoassays in use world-wide and our study utilized three. Regrettably, some manufacturers declined to participate in this study. Hence, generalization to all ANA assays is not possible (42, 44).

In conclusion, we demonstrated that early in their disease course almost all adult SLE patients had highly positive ANAs. However, as the disease progressed, we observed increased frequency of ANA within the normal range and decreased ANA titres/values by some assays likely related to differences in assay performance, medication exposure, decreased autoantibody responses over time, and lower disease activity. Combining ANA assays resulted in fewer patients that tested within normal range and no patients who tested within the normal range over the five years with all three assays. A clinical implication of this study is that for patients who have a moderate-to-high suspicion of SLE, especially those early in the disease course but without an established diagnosis, screening on both ELISA and HEp-2 IFA is warranted if one or the other provides results in the normal range. And given the rather modest changes in ANA frequency (and/or titers) observed in this longitudinal study of 5 years follow up, it is difficult to perceive of actionable clinical value of ANA IFA or screening ELISA test results over this time period once the diagnosis of SLE has been established. Since there are differences in the performance characteristics of individual ANA assays, clinicians need to be aware of the performance characteristics of the ANA test that their laboratories use. Future studies testing the comparative performance of other ANA immunoassays over time in large populations will help inform approaches to an earlier and more accurate diagnosis and classification of SLE.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages:

What is already known about this subject?

Cross-sectional data of small cohorts suggest significant variation in the performance of antinuclear antibody (ANA) assays from different manufacturers leaving clinicians uncertain about the use or value of ANA testing in making a diagnosis.

What does this study add?

In a longitudinal analysis of well-characterized patients with incident systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), almost all SLE patients early in disease had highly positive ANAs and no patients who tested within the normal range over 5 years of follow up with all three assays.

As the disease evolved over 5 years of follow-up, there was decreased frequency of positive ANAs (above the normal range) and decreased ANA titres by some assays.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

In a patient without an established diagnosis of SLE and in whom the clinical suspicion for SLE is moderate to high, both IFA and ELISA should be performed if one or the other provides results in the normal range.

Acknowledgements:

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Ms. Haiyan Hou, who conducted the laboratory testing, Ms. Meifeng Zhang (MitogenDx, University of Calgary), Ms. Katherine Buhler, Ms. Chynace Lambalgen, and the SLICC nurse coordinators.

Grant Support:

The cost of the immunoassay supplies and labor were supported by the Lupus Foundation of America and MitogenDx.

Dr. May Choi is supported by the Lupus Foundation of America Gary S. Gilkeson Career Development Award and research gifts in kind from MitogenDx (Calgary, Canada).

Dr. Clarke holds The Arthritis Society Research Chair in Rheumatic Diseases at the University of Calgary.

Dr. Costenbader is supported by NIH K24 AR066109.

Dr. Hanly’s work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (research grant MOP-88526).

Dr. Caroline Gordon’s work was supported by Lupus UK, Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust and the NIHR /Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility in Birmingham.

Dr. Sang-Cheol Bae’s work was supported by the Korea Healthcare technology R & D project, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120404).

The Montreal General Hospital Lupus Clinic is partially supported by the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research.

Dr. Rahman and Dr. Isenberg are supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is supported by NIH Grants AR043727 and AR069572

Dr. Paul R. Fortin presently holds a tier 1 Canada Research Chair on Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases at Université Laval, and part of this work was done while he was still holding a Distinguished Senior Investigator of The Arthritis Society.

Dr. Bruce is an NIHR Senior Investigator Emeritus and is funded by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR/Wellcome Trust Manchester Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Dr. Mary Anne Dooley’s work was supported by the NIH grant RR00046.

Dr. Ramsey-Goldman’s work was supported by the NIH (grants 1U54TR001353 formerly 8UL1TR000150 and UL-1RR-025741, K24-AR-02318, and P60AR064464 formerly P60-AR-48098).

Dr. Susan Manzi is supported by grants R01 AR046588 and K24 AR002213

Dr. Ruiz-Irastorza is supported by the Department of Education, Universities and Research of the Basque Government.

Dr. Soren Jacobsen is supported by the Danish Rheumatism Association (A1028) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (A05990).

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

Dr. May Choi has received consulting fees from Janssen and MitogenDx (less than $10,000).

Dr. Ann Clarke has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, BristolMyersSquibb, and Glaxo Smith Kline (less than $10,000 each).

Dr. Costenbader has consulted for or collaborated on research projects with Janssen, Glaxo Smith Kline, Exagen Diagnostics, Eli Lilly, Merck Serono, Astra Zeneca and Neutrolis (less than $10,000 each).

Dr. Gordon has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Abbvie, Amgen, UCB, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono and BMS (less than $10,000 each) and grants from UCB. Grants from UCB were not to Dr. Gordon but to Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust.

Dr. Dafna Gladman received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline (less than $10,000).

Dr. Bruce has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Eli Lilly, UCB, Roche, Merck Serono, MedImmune (less than $10,000 each) and grants from UCB, Genzyme Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Ginzler has paid consultation with investment analysts Guidepoint Global Gerson Lerman Group.

Dr. Kalunian has received grants from UCB, Human Genome Sciences/GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Ablynx, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and has received consulting fees from Exagen Diagnostics, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Anthera (less than $10,000 each).

Dr. Fritzler is Director of Mitogen Diagnostics Corporation (Calgary, AB Canada) and a consultant to Werfen International (Barcelona, Spain), Grifols (Barcelona, Spain), Janssen Pharmaceuticals of Johnson & Johnson and Alexion Canada (less than $10,000 each).

The remainder of the authors have no disclosures.

Ethical Approval Information

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site.

Patient and Public Involvement statement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Data Sharing Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References:

- 1.Choi MY, Fritzler MJ. Autoantibodies in SLE: prediction and the p value matrix. Lupus. 2019;28(11):1285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leuchten N, Hoyer A, Brinks R, Schoels M, Schneider M, Smolen J, et al. Performance of Antinuclear Antibodies for Classifying Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Regression of Diagnostic Data. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(3):428–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(9):1400–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aringer M, Brinks R, Dorner T, Daikh D, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) SLE classification criteria item performance. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heller CA, Schur PH. Serological and clinical remission in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1985;12(5):916–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paz E, Adawi M, Lavi I, Mussel Y, Mader R. Antinuclear antibodies measured by enzyme immunoassay in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: relation to disease activity. Rheumatology international. 2007;27(10):941–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frodlund M, Wettero J, Dahle C, Dahlstrom O, Skogh T, Ronnelid J, et al. Longitudinal anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) seroconversion in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study of Swedish cases with recent-onset disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2020;199(3):245–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faria AC, Barcellos KS, Andrade LE. Longitudinal fluctuation of antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(7):1267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, Scofield RH, Dennis GJ, James JA, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(16):1526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan AB, Lundberg IE, Isenberg D, Wahren-Herlenius M. Serial analysis of Ro/SSA and La/SSB antibody levels and correlation with clinical disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31(3):133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tench CM, Isenberg DA. The variation in anti-ENA characteristics between different ethnic populations with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 10-year period. Lupus. 2000;9(5):374–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Praprotnik S, Bozic B, Kveder T, Rozman B. Fluctuation of anti-Ro/SS-A antibody levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome: a prospective study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17(1):63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher DE, Reeves WH, Wisniewolski R, Lahita RG, Chiorazzi N. Temporal shifts from Sm to ribonucleoprotein reactivity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28(12):1348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barada FA, Jr., Andrews BS, Davis JSt, Taylor RP. Antibodies to Sm in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Correlation of Sm antibody titers with disease activity and other laboratory parameters. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24(10):1236–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acosta-Merida A, Isenberg DA. Antinuclear antibodies seroconversion in 100 patients with lupus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(4):656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gisca E, Duarte L, Farinha F, Isenberg DA. Assessing outcomes in a lupus nephritis cohort over a 40-year period. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(4):1814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritzler MJ. Choosing wisely: Review and commentary on anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) testing. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raissi TC, Hewson C, Pope JE. Repeat Testing of Antibodies and Complements in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: When Is It Enough? J Rheumatol. 2018;45(6):827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossuyt X, De Langhe E, Borghi MO, Meroni PL. Understanding and interpreting antinuclear antibody tests in systemic rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(12):715–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bizzaro N, Brusca I, Previtali G, Alessio MG, Daves M, Platzgummer S, et al. The association of solid-phase assays to immunofluorescence increases the diagnostic accuracy for ANA screening in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(6):541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisetsky DS, Spencer DM, Lipsky PE, Rovin BH. Assay variation in the detection of antinuclear antibodies in the sera of patients with established SLE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):911–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chevrier M, Jordan J, Schreiter J, Benson J, editors. Comparative analysis of anti-nuclear antibody testing using blinded replicate samples reveals variability between commercial testing laboratories (abstract). Arthritis & rheumatology; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumagai S, Hayashi N. Immunofluorescence--still the ‘gold standard’ in ANA testing? Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2001;235:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez D, Gilburd B, Azoulay D, Shovman O, Bizzaro N, Shoenfeld Y. Antinuclear antibodies: Is the indirect immunofluorescence still the gold standard or should be replaced by solid phase assays? Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(6):548–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meroni PL, Chan EK, Damoiseaux J, Andrade LEC, Bossuyt X, Conrad K, et al. Unending story of the indirect immunofluorescence assay on HEp-2 cells: old problems and new solutions? Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(6):e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claessens J, Belmondo T, De Langhe E, Westhovens R, Poesen K, Hue S, et al. Solid phase assays versus automated indirect immunofluorescence for detection of antinuclear antibodies. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(6):533–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi MY, Clarke AE, St Pierre Y, Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Romero-Diaz J, et al. Antinuclear Antibody-Negative Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in an International Inception Cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(7):893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isenberg D, Ramsey-Goldman R, Gladman D, Hanly J. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) group–It was 20 years ago today. Lupus. 2011;20(13):1426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1997;40(9):1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damoiseaux J, von Muhlen CA, Garcia-De La Torre I, Carballo OG, de Melo Cruvinel W, Francescantonio PL, et al. International consensus on ANA patterns (ICAP): the bumpy road towards a consensus on reporting ANA results. Auto Immun Highlights. 2016;7(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aringer M, Costenbader KH, Dorner T, Johnson SR. Importance of high-quality ANA testing for SLE classification. Response to: ‘Role of ANA testing in the classification of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus’ by Pisetsky et al et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;annrheumdis-2019-216337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pisetsky DS, Rovin BH, Lipsky PE. New Perspectives in Rheumatology: Biomarkers as Entry Criteria for Clinical Trials of New Therapies for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: The Example of Antinuclear Antibodies and Anti-DNA. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahler M, Meroni PL, Bossuyt X, Fritzler MJ. Current concepts and future directions for the assessment of autoantibodies to cellular antigens referred to as anti-nuclear antibodies. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:315179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen NJ, Choi MY, Fritzler MJ. Emerging technologies in autoantibody testing for rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pisetsky DS, Thompson DK, Wajdula J, Diehl A, Sridharan S. Variability in Antinuclear Antibody Testing to Assess Patient Eligibility for Clinical Trials of Novel Treatments for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(9):1534–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wohrer S, Troch M, Zwerina J, Schett G, Skrabs C, Gaiger A, et al. Influence of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone on serologic parameters and clinical course in lymphoma patients with autoimmune diseases. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(4):647–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prado MS, Dellavance A, Rodrigues SH, Marvulle V, Andrade LEC. Changes in the result of antinuclear antibody immunofluorescence assay on HEp-2 cells reflect disease activity status in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(8):1271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng KP, Cambridge G, Leandro MJ, Edwards JC, Ehrenstein M, Isenberg DA. B cell depletion therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus: long-term follow-up and predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1259–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pisetsky DS, Lipsky PE. New insights into the role of antinuclear antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(10):565–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aringer M, Dörner T, Leuchten N, Johnson S. Toward new criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus—a standpoint. Lupus. 2016;25(8):805–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bizzaro N Can solid-phase assays replace immunofluorescence for ANA screening? Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(3):e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fritzler MJ, Wiik A, Fritzler ML, Barr SG. The use and abuse of commercial kits used to detect autoantibodies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(4):192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fritzler MJ. The antinuclear antibody test: last or lasting gasp? Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiik AS, Bizzaro N. Missing links in high quality diagnostics of inflammatory systemic rheumatic diseases: It is all about the patient! Auto Immun Highlights. 2012;3(2):35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.