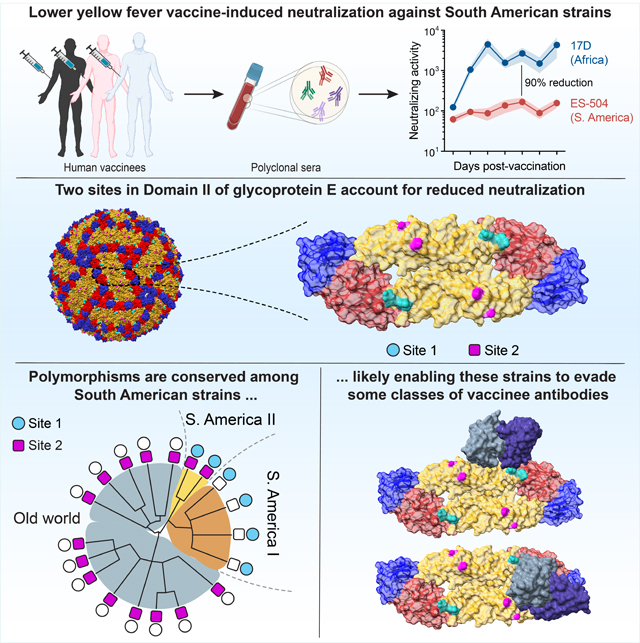

Summary

The resurgence of yellow fever in South America has prompted vaccination against the etiologic agent, yellow fever virus (YFV). Current vaccines are based on a live-attenuated YF-17D virus derived from a virulent African isolate. The capacity of these vaccines to induce neutralizing antibodies against the vaccine strain is used as a surrogate for protection. However, the sensitivity of genetically distinct South American strains to vaccine-induced antibodies is unknown. We show that antiviral potency of the polyclonal antibody response in vaccinees is attenuated against an emergent Brazilian strain. This reduction was attributable to amino acid changes at two sites in central domain II of the glycoprotein E, including multiple changes at the domain I–domain II hinge, which are unique to and shared among most South American YFV strains. Our findings call for a reevaluation of current approaches to YFV immunological surveillance in South America and suggest approaches for updating vaccines.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Yellow fever virus (YFV), a prototypic flavivirus and the etiologic agent of yellow fever, is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Central and South America. Although YFV largely circulates in a sylvatic cycle between mosquitoes and nonhuman primates, mosquito-borne viral transmission from nonhuman primates to humans can occur due to encroachment by the latter into forested areas. Further, high population densities in urban areas can trigger cycles of human-to-human transmission that are maintained by anthropophilic mosquitoes. YFV has periodically resurged in endemic areas in South America since the 1960s, but especially intense reemergence events have been documented in both endemic and non-endemic areas in the past decade (Douam and Ploss, 2018). The 2016–19 YFV epidemic centered in southeastern Brazil was the largest in over 70 years, with >2,000 cases and >750 deaths (Hill et al., 2020; de Oliveira Figueiredo et al., 2020).

The live-attenuated YF-17D virus was derived from the virulent African strain Asibi and was further passaged to yield closely related variants (e.g., YF-17D-204 and YF-17DD; hereafter, YF-17D) that form the basis of YFV vaccines currently in use. These are among the most effective vaccines ever created and remain the linchpin of global efforts to control yellow fever (Barrett and Teuwen, 2009). Single doses of YF-17D are expected to confer protection for at least 2–3 decades post-immunization (Barrett and Teuwen, 2009; Monath, 2012). The drivers of YFV reemergence in South America and elsewhere in the face of YF-17D vaccination are likely complex and related to multiple factors, including ecological disruptions attendant to human activity and climate change, inadequate mosquito control, and suboptimal vaccination rates exacerbated by ongoing vaccine shortages (WHO, 2018). An understanding of the factors that influence YFV reemergence and vaccine efficacy is crucial for the prevention and management of future outbreaks.

Current evidence indicates that the 2017–19 YFV epidemic in Brazil was associated with an emerging strain, YFV 2017–19, which bears multiple nonsynonymous changes at conserved sequences in several nonstructural proteins (Bonaldo et al., 2017; Giovanetti et al., 2019; Gómez et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2020). These observations prompted hypotheses that one or more viral genome sequence polymorphisms could influence YFV emergence, transmission, and/or virulence (Bonaldo et al., 2017). However, previous studies have not examined the alternative or additional possibility that antiviral activity of the vaccine-induced antibody response could be affected by genetic changes in circulating YFV strains.

The induction of neutralizing, or viral entry-blocking, antibodies targeting the envelope protein, E, is considered the most important surrogate marker for vaccine-induced protection and has been described as the major mechanism that confers long-lasting protection against flavivirus disease (Mason et al., 1973; Plotkin, 2010). Here, we show that the neutralization potency of the YFV vaccine-induced human polyclonal antibody and monoclonal antibody responses against the emergent, and now endemic, YFV 2017–19 strain is substantially lower than that predicted from classical potency assays employing the vaccine strains or a wild-type African YFV strain. This reduction was largely attributable to genetic changes at two sites in the central domain II of the YFV 2017–19 E protein. Our phylogenetic analysis of available YFV genome sequences revealed that these changes are completely absent in all African and Asian (ex-African) sequences but shared among essentially all South American sequences dating back to 1977. Finally, analysis of a large panel of vaccinee-derived E-directed monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) pointed to the existence of currently undefined antibody specificities that contribute to viral neutralization by vaccinee sera in a manner that is sensitive to sequence polymorphisms in the domain I–domain II hinge. Our findings have potential implications for understanding the molecular basis of YFV’s adaptation to sylvatic cycles following its introduction into the Americas, managing outbreaks through YF-17D vaccination in South America, and designing updated YFV vaccines.

Results

The Brazilian isolate YFV-ES-504 is poorly neutralized by YFV-17D vaccinee sera

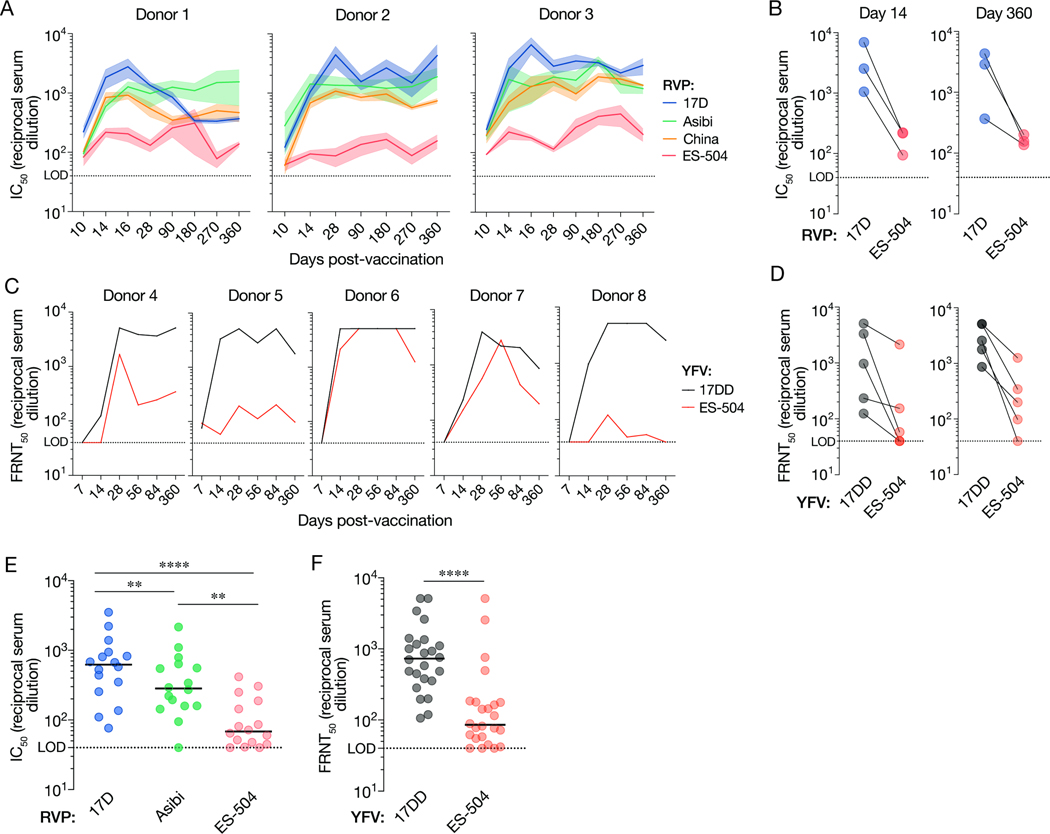

We first examined the breadth of the anti-YFV neutralizing antibody response over time in three previously described U.S. YF-17D vaccinees (donors 1–3) with no serological evidence of prior flavivirus exposure and well-characterized mAbs responses (Wec et al., 2020) (Table S1). Neutralizing activity in sera from the U.S. donors was measured at days 0, 10, 14, 16, 28, 90, 180, 270 and 360 post vaccination (Figure 1A–B) with a widely employed West Nile virus-based reporter viral particle system (RVP) (Pierson et al., 2006). RVPs faithfully recapitulate the behavior of authentic flaviviruses in studies of virus structure, function, and antibody recognition and neutralization (Bohning et al., 2021; Bradt et al., 2019; Dowd et al., 2011; Goo et al., 2016, 2017; Mattia et al., 2011) (Figure S1). Serum neutralizing titers against RVPs bearing the structural proteins C-prM-E from the YF-17D vaccine strain (RVP17D) and the virulent African strains Asibi (RVPAsibi) and China (ex-Angola) (RVPChina) (Figure 1A) rose sharply, peaked at days 14–16, and remained stable thereafter, as reported previously (Lindsey et al., 2018; Wec et al., 2020; Wieten et al., 2016). By contrast, we observed little or no increase in neutralizing titers against RVPES-504, bearing E from the prototypic YFV 2017–19 isolate YFV-ES-504 (ES-504/BRA/2017) (Bonaldo et al., 2017) over days 10–16 in all three donors, and the titers remained at ~10-fold lower levels relative to RVP17D at all timepoints tested (Figure 1A–B).

Figure 1. Antiviral potency and breadth of the neutralizing antibody response elicited by YF-17D vaccination.

(A) Serum neutralizing titers (half-maximal inhibitory concentration values from dose-response curves [IC50]) for three YF-17D–vaccinated U.S. donors over time against the indicated RVPs. Means±SEM, n=9–15 from 3–5 independent experiments. (B) Serum neutralizing titers for the three donors in panel A at days 14 and 360 post-vaccination. Means, n=9–15 from 3–5 independent experiments. (C) Serum neutralizing titers (half-maximal inhibitory concentration values in a focus reduction neutralization test [FRNT50]) for five YF-17DD–vaccinated Brazilian donors over time against the indicated authentic viruses. Means, n=3. (D) Serum neutralizing titers (FRNT50) for the five donors in panel C at days 14 and 360 post-vaccination. Means, n=3. (E) Serum neutralizing titers for a U.S. vaccinee cohort (n=16 donors) against the indicated RVPs. n=9–12 from 3–4 independent experiments. (F) Serum neutralizing titers (FRNT50) for a Brazilian vaccinee cohort (n=24 donors against the indicated authentic viruses. n=3. In panels E–F, lines indicate group medians. Groups in E were compared by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. Groups in F were compared by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. **, P<0.002. ****, P<0.0001. LOD, limit of detection.

We next assessed the neutralizing antibody response to YF-17D vaccination in five Brazilian donors (donors 4–8) with unknown flavivirus exposure history at days 0, 7, 14, 28, 56, 84 and 360 post vaccination (Figure 1C and Table S1). Comparison of serum neutralizing titers against authentic YFV-17D and YFV-ES-504 revealed blunted increases in YFV-ES-504 neutralizing activity at early times post-vaccination and substantially reduced neutralization potency relative to the vaccine strain, especially at later times, in three of five donors (Figure 1C–D). Donor sera from larger cohorts of U.S. and Brazilian vaccinees (Figures 1E–F and Table S1) corroborated this trend and revealed statistically significant reductions in YFV-ES-504 neutralization relative to YF-17D. Together, these findings indicate that vaccination with YF-17D elicits an antibody response that is substantially less effective at in vitro neutralization of the Brazilian YFV-ES-504 isolate than of the vaccine strains.

Reduced YFV-ES-504 recognition and neutralization by a panel of mAbs isolated from YF-17D vaccinees

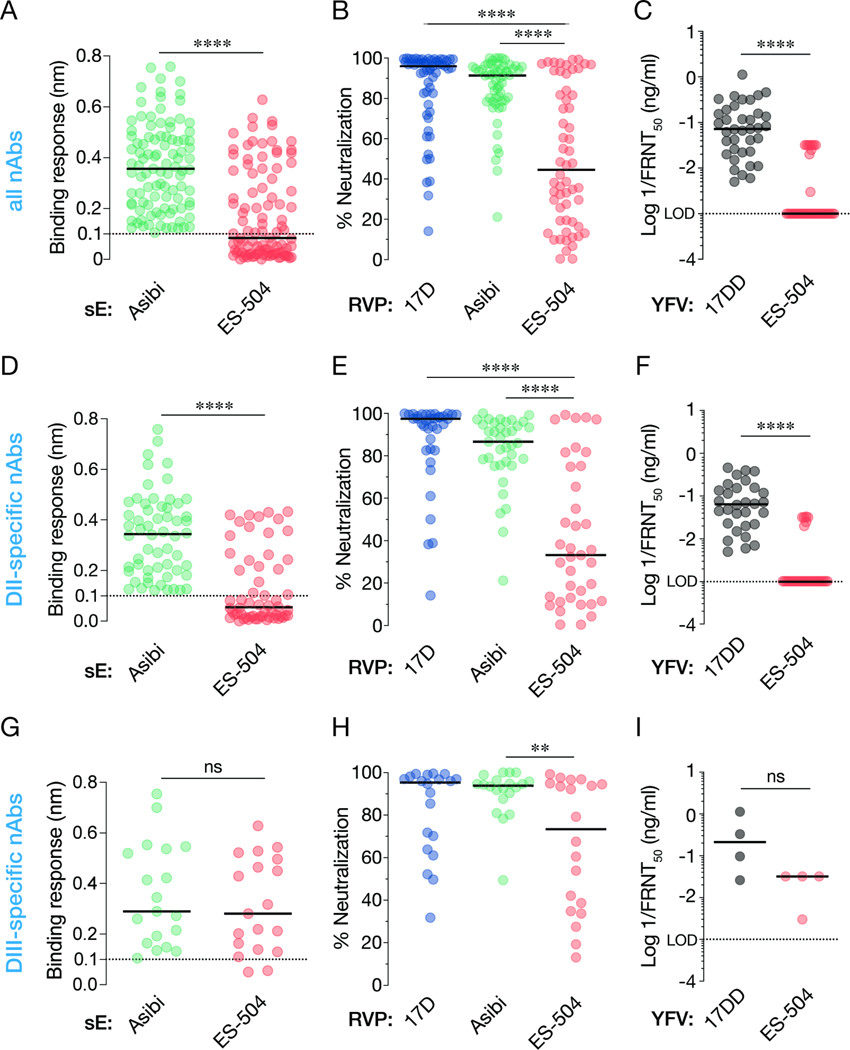

We previously isolated and characterized a large collection of YFV E-specific mAbs from U.S. YF-17D vaccinees (donors 1–3) (Wec et al., 2020). To further investigate the antiviral breadth of the vaccine-elicited antibody response, we screened 105 mAbs from this collection for their capacity to recognize the ES-504 E protein and neutralize viral particles bearing it. We measured large reductions in nAb binding to a recombinant YFV-ES-504 E protein relative to YFV-Asibi E by biolayer interferometry (BLI) (Figure 2A). Similar trends in loss of YFV-ES-504 neutralization potency were observed in neutralization assays with RVPs (Figure 2B) and the authentic viruses (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Binding and neutralization breadth of a panel of nAbs isolated from YF-17D vaccinees.

(A) 99 nAbs were tested for their binding response to recombinant, soluble E (sE) proteins from the indicated viruses by biolayer interferometry. (B) Neutralizing activities of selected nAbs (10 nM) against the indicated RVPs. Means, n=6–9 from three independent experiments, (C) Neutralizing activities of selected mAbs against the indicated authentic viruses. (D) A subset of nAbs comprising DII binders were evaluated for sE binding as in panel A. (E–F) Neutralizing activities of DII-specific nAbs against the indicated RVPs (E) and authentic viruses (F), as in panels B–C. (G–I) Binding (G) and neutralization activities (H–I) of DIII-specific nAbs, as in panels B–C. In all panels, lines indicate group medians. Groups in A, C, D, F, G, and I were compared by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Groups in B, E, H were compared by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. **, P<0.002. ****, P<0.0001. ns, not significant. Only the significant comparisons are shown in panels B, E, H. LOD, limit of detection.

The major surface protein E of YFV resembles those of other flavivirus envelope glycoproteins in comprising three domains, domain I, II and III (hereafter, DI, DII and DIII, respectively). In the mature virion, 90 head-to-tail dimers of E are organized into a T=3 icosahedral capsid that packages the viral genome and mediates its cytoplasmic delivery (Rey et al., 2018). A majority of the neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) in our panel recognize non-fusion–loop antigenic sites in domain II (DII) of the YFV-17D E protein, whereas a significant minority recognize domain III (DIII) (Wec et al., 2020). To begin to define the molecular basis of reduced YFV-ES-504 binding and neutralization by YF-17D vaccinee antibodies, we curated subsets of potent DII- and DIII-specific nAbs and screened them for binding and neutralization, as above (Figure 2D–I and Data S1). We found that the YFV-ES-504–dependent reductions in nAb:E binding could be largely recapitulated by the DII nAbs alone (Figure 2D and G). Concordantly, the DII nAbs suffered substantial reductions in neutralizing potency against viral particles bearing YFV-ES-504 E (Figure 2E–F), whereas the DIII nAbs were only moderately affected (Figure 2H–I). These findings raised the possibility that antibodies in human vaccinee sera specific for DII, and to a lesser degree, DIII, could significantly influence the capacity of these sera to neutralize YFV-ES-504 in vitro (Figure 1).

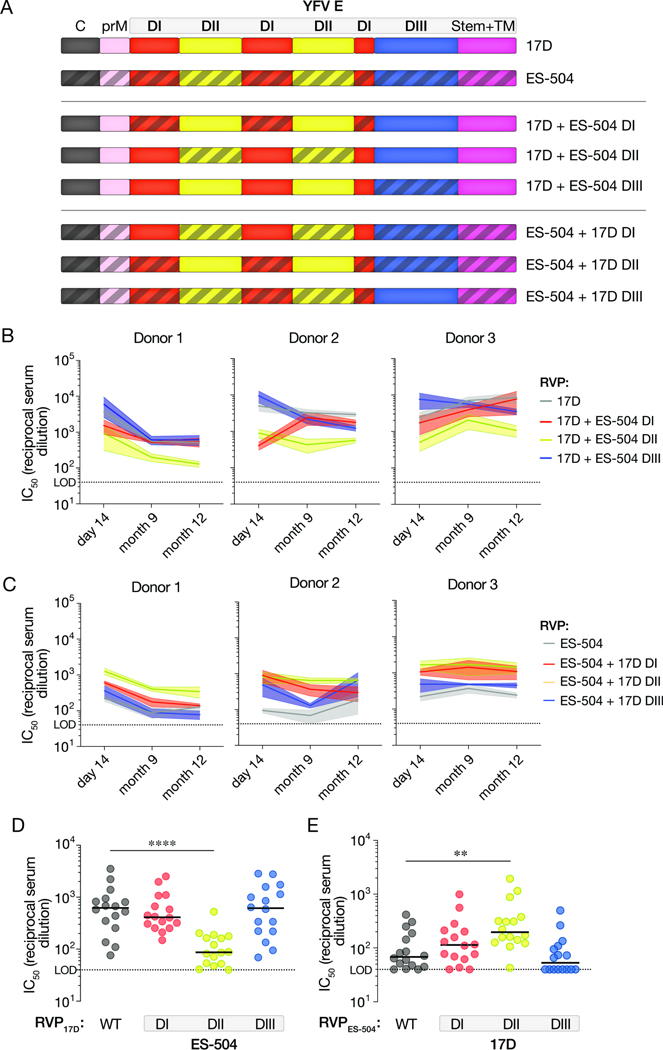

Sequence polymorphisms in domain II of the glycoprotein E largely account for the reduced neutralization sensitivity of YFV-ES-504

To uncover the genetic basis of this viral strain-dependent difference in neutralization sensitivity, we next generated and tested RVPs bearing a panel of E chimeras in which DI, DII, or DIII were exchanged between YFV-17D and YFV-ES-504 (Figure 3A). RVP17D bearing YFV-ES-504 DII were much less sensitive to neutralization by the DII-specific nAbs, but remained susceptible to the DIII-specific nAbs, as expected (Figure S2). Importantly, these DII-chimeric RVPs also showed reduced sensitivity to neutralization by the U.S. vaccinee sera relative to wildtype (WT) RVP17D at all three timepoints tested (Figure 3B). Conversely, the reciprocal RVPES-504 chimera bearing YFV-17D DII showed enhanced neutralization sensitivity relative to its parent (Figure 3C). Analysis of a larger cohort of U.S. YFV-17D vaccinees (n=16; see Figure 1E) corroborated these trends: we measured a ~10-fold reduction in median neutralization titer with RVP17D–ES-504 DII relative to RVP17D-WT (Figure 3D) and a smaller (~3–4-fold), but statistically significant, increase in titer with RVPES-504–17D DII relative to RVPES-504-WT (Figure 3E). The DI chimeras afforded smaller, but concordant, changes in neutralization sensitivity, whereas the DIII chimeras were unaffected (Figure 3D–E). These findings indicate that one or more sequence polymorphisms in DII of glycoprotein E largely account for the reduced sensitivity of YFV-ES-504 to neutralization by YF-17D vaccinee sera.

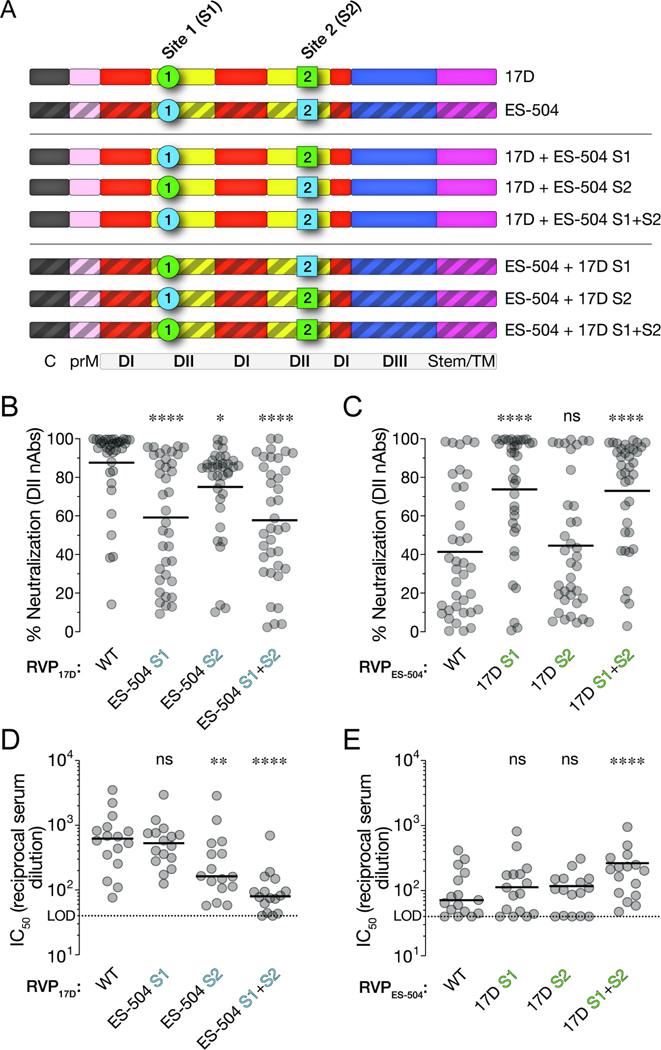

Figure 3. Neutralizing activities of vaccinee sera against RVPs bearing 17D/ES-504 domain-swapped E proteins.

(A) Schematic of the 17D/ES-504 E protein chimeras. (B–C) Serum neutralizing titers for the three U.S. donors (see Figure 1A) at the indicated times post-vaccination against the indicated RVPs. Means±SEM, n=6–12 from 2–4 independent experiments. (D–E) Serum neutralizing titers for a U.S. vaccinee cohort (n=16 donors; see Figure 1E) against the indicated RVPs. n=6–12 from 2–4 independent experiments. Parental RVP17D and RVPES-504 controls are from Figure 1E. Groups in D–E were compared to WT by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. **, P<0.002. ****, P<0.0001. Only the significant comparisons are shown. In all panels, lines indicate group medians. LOD, limit of detection.

Two sites in domain II influence YFV neutralization by YF-17D vaccinee sera

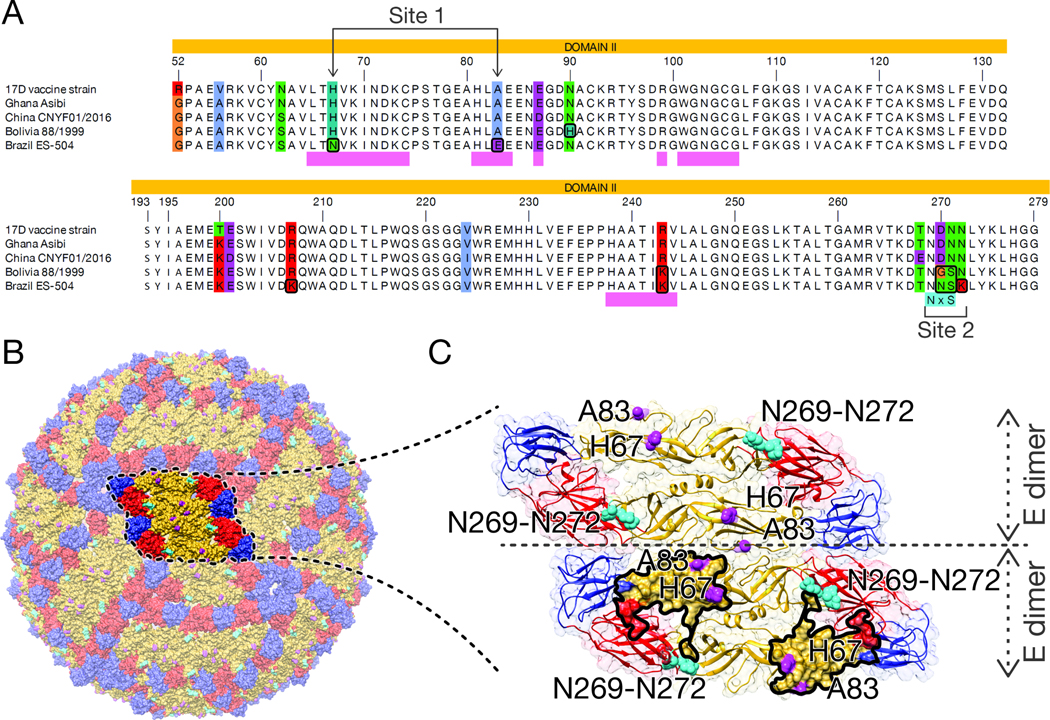

A comparison of the amino acid sequences of African (17D, Asibi, China) and South American YFV strains (ES-504) revealed nonconservative changes unique to YFV-ES-504 at five positions in DII: H67N, A83E, D270E, N271S, and N272K (Figure 4A). The first two positions (Site 1: residues 67 and 83) map within or near the binding footprints of the recently described protective nAb 5A (Figure 4) ((Lu et al., 2019; Wec et al., 2020) and a large cohort of potent, 5A-competing neutralizers we recently isolated from YF-17D vaccinees (Lu et al., 2019; Wec et al., 2020). These nAbs recognize overlapping, fusion loop-proximal DII epitopes in E proteins from African strains (Lu et al., 2019; Wec et al., 2020). The last three polymorphic residues (Site 2: residues 270–272) are located in the kl loop that forms part of the hinge region connecting DII and DI ((Lu et al., 2019) and PDB: 6EPK) (Figures 4B–C).

Figure 4. YFV strain-dependent sequence polymorphisms in DII of the E protein.

(A) Amino acid sequence alignments of the portion of E corresponding to DII are shown for the indicated sequences. The colored residues in the alignment correspond to positions where residue identities are not identical in all five sequences. Polymorphic sites 1 and 2 are indicated below the alignment. (B) Amino acid positions with unique residue identities in YFV-ES-504 E are shown on a YFV virion, which was constructed in Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) using the atomic coordinates of YFV E (Lu et al., 2019) and the symmetry matrix of the dengue virus 2 virion (Zhang et al., 2004). (C) Close-up view displaying two neighboring dimers. Highlighted surface area in the lower dimer corresponds to the nAb 5A binding interface as dictated by PISA (relative buried surface area ≥ 10%) (Krissinel and Henrick, 2007). Residue numbering corresponds to that of the mature YFV-17D E protein.

To investigate the effects of these localized amino acid substitutions, we evaluated the neutralization sensitivity of RVPs bearing additional 17D-ES-504 E chimeras in which these two sites (Site 1: residues 67 and 83; Site 2: residues 270–272) were exchanged (Figure 5A). Swapping Site 1 between YFV-17D and -ES-504 E proteins reduced the neutralizing activity of the DII-specific vaccinee nAbs, concordant with the preponderance of known 5A-competing nAbs in this panel (Figures 5B–C and S3). Strikingly, however, these Site 1 chimeras had little or no impact on viral neutralization by the YF-17D vaccinee sera (Figure 5D–E). Conversely, whereas the DII nAbs (Figure 5B–C) and their 5A-competing subset (Figure S3) were much less affected by the Site 2 chimeras, the introduction of ES-504 Site 2 into RVP17D was associated with substantial losses in serum neutralizing activity (Figure 5D). The reciprocal RVPES-504 chimeras bearing 17D Site 1 or Site 2 showed small, but not statistically significant, increases in sensitivity to the vaccinee sera (Figure 5E) However, combining both sets of changes in each strain background afforded larger shifts in serum neutralizing titer (Figures 5D–E). Taken together, these findings indicate that sequence polymorphisms at Sites 1 and 2 in DII largely account for the reduced neutralizing activity of YF-17D vaccinee sera against YFV-ES-504, especially when both sets of 17D→ES-504 changes are simultaneously present. They also suggest that this phenotype observed with polyclonal sera cannot be readily attributed to changes in activity of the potently neutralizing, 5A-competing, nAbs alone.

Figure 5. Effects of polymorphisms at Sites 1 and 2 on the neutralizing activities of vaccinee nAbs and sera.

(A) Schematic of YFV-17D and -ES-504 E proteins chimerized at Sites 1 and 2. (B–C) Neutralizing activities of selected DII-specific nAbs (10 nM) against the indicated RVPs. Means, n=6–12 from 2–4 independent experiments, Parental RVP17D and RVPES-504 controls are from Figure 2. (D–E) Serum neutralizing titers for a U.S. vaccinee cohort (n=16 donors; see Figure 1E) against the indicated RVPs. Means, n=6–12 from 2–4 independent experiments. Parental RVP17D and RVPES-504 controls are from Figure 1E. Groups were compared to WT by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. **, P<0.002. ****, P<0.0001. ns, not significant. In all panels, lines indicate group medians. LOD, limit of detection.

N–glycosylation at residue 269 and Asn-to-Lys change at residue 272 both contribute to YFV-ES-504 neutralization resistance

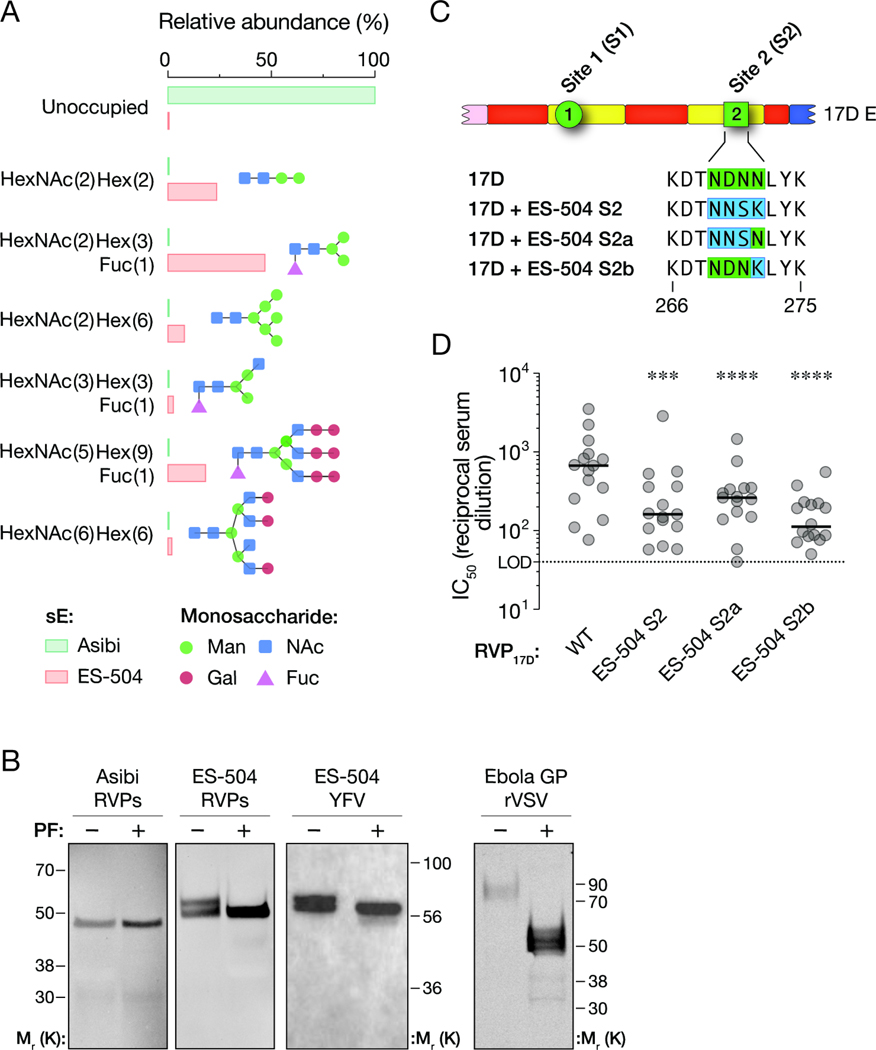

The central portion of the kl loop contains Site 2 ((Lu et al., 2019) and PDB: 6EPK) and is not known to be a critical binding determinant of YFV E-specific mAbs (Daffis et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2019). Through both manual inspection and a search for eukaryotic linear motifs, we identified a putative N–linked glycosylation site (NXS/T sequon) at Site 2 residues 269–271 (NNS) in YFV-ES-504 but not YFV-17D or -Asibi (NDN) (Figure 4A) (Gupta and Brunak, 2002). To obtain experimental evidence for viral strain-dependent E glycosylation at this position, we subjected recombinant, soluble YFV-Asibi and YFV-ES-504 E proteins (sE) produced in S2 cells to mass spectrometry. Consistent with the bioinformatic predictions, LC-MS/MS analysis of tryptic glycopeptides revealed a high degree of N–glycan occupancy at amino acid residue Asn 269 in YFV-ES-504 sE (>90%) but no detectable N–glycosylation at the same position in YFV-Asibi sE (Figure 6A). We next exposed RVPs bearing Asibi or ES-504 E proteins to the enzyme protein N–glycosidase F (PNGase F) to selectively remove N–linked glycans and then resolved these proteins on polyacrylamide gels and detected them by Western blot (Figure 6B). Asibi E migrated as a single species whose electrophoretic mobility was not altered by PNGase F treatment at conditions that completely deglycosylated Ebola virus GP, consistent with the lack of NXS/T sequons in the former protein. By contrast, ES-504 E migrated as a doublet that shifted down to the faster-migrating species following PNGase F treatment. A similar result was obtained with authentic YFV ES-504 E. We conclude that ES-504 E is modified by N–linked glycosylation at Asn 269, but that N–glycan occupancy at this site varies in a host cell-dependent manner.

Figure 6. Effects of polymorphisms at subsite 2a and 2b on N–linked glycosylation of YFV E and neutralization sensitivity to vaccinee sera.

(A) Occupancy and relative abundance of the indicated glycan structures at residue Asn 269 in recombinant soluble E proteins (sE) from YFV-Asibi and YFV-ES-504 E were determined by mass spectrometry. (B) E protein immunoprecipitates from RVPAsibi and RVPES-504, and postnuclear lysates from authentic virus ES-504–infected cells were subjected to PNGase F treatment and detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Viral particles bearing the Ebola virus glycoprotein (GP) were used as an internal control for PNGase F activity. Representative blots are shown. (C) Schematic of YFV-17D E protein chimerized at subsites 2a and 2b. (D) Serum neutralizing titers for a U.S. vaccinee cohort, n=15, against the indicated RVPs. Means, n=6 from 2 independent experiments. Parental RVP17D controls are from Figure 1E. Groups were compared to WT by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. ***, P<0.0002. ****, P<0.0001. In all panels, lines indicate group medians. LOD, limit of detection.

To independently assess the roles of this sequon (Site 2a) and the Asn-to-Lys change at residue 272 (N272K; Site 2b) in determining the Site 2 neutralization phenotype, we tested two additional RVP17D chimeras bearing ES-504 Site 2a or Site 2b (Figure 6C). Changes at both subsites reduced the neutralizing activity of YF-17D vaccinee sera, with the Site 2b change having the larger effect (Figure 6D).

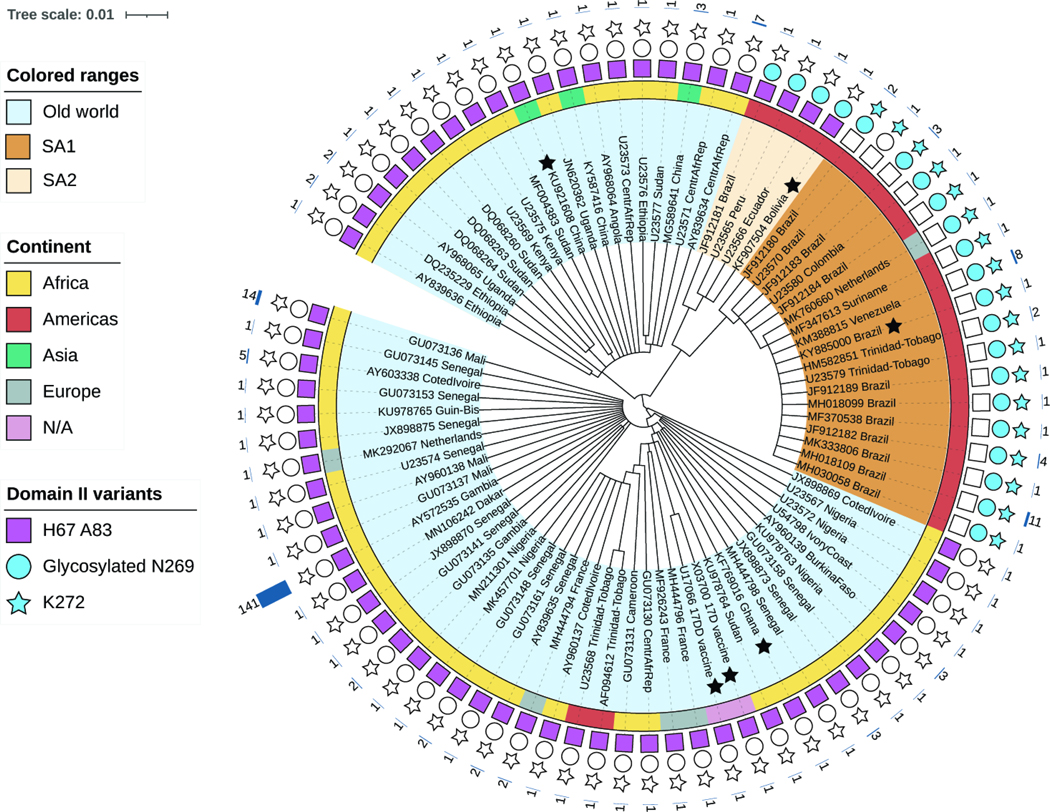

Changes at Sites 1 and 2 show distinct patterns of conservation among South American E sequences

We aligned a representative set of 82 non-redundant YFV E protein sequences encompassing the sequence space of 281 fully sequenced YFV E genes (see Methods) (Data S2). This alignment revealed that the Site 1 and 2 changes were unique to YFV sequences of South American origin (Figure 7) but also uncovered subclade-specific differences in the occurrence of these polymorphisms. Specifically, the 17D→ES-504 changes at Site 1 and Site 2b were observed in nearly all sequences from the subclade to which YFV-ES-504 belongs (South American ‘genotype I’), but not in any of the unique South American ‘genotype II’ sequences available for analysis. By contrast, both genotype I and II strains encoded a sequon at Asn 269, albeit with different sequences (genotype I, NNS; genotype II, NGS) (Figure 4A). RVPs bearing E from a prototypic genotype II strain, YFV-Bolivia (YFV/BOL/88/1999), also displayed resistance to neutralization by YF-17D vaccinee sera (Figure S4), although at reduced levels relative to YFV-ES-504. YFV-Bolivia’s intermediate phenotype may reflect that it and other South American genotype II strains combine N–glycosylation at Asn 269, a YFV-ES-504–like signature, with YFV-17D/Asibi-like signatures at Sites 1 and 2b (Figures 6B and 4A), although other sequences polymorphic between YFV-ES-504 and YFV-Bolivia may also play a role. Taken together, our findings indicate that genetic variation at two distinct sites in DII influences the reduced sensitivity of YFV-ES-504 and other South American strains to neutralization by YF-17D vaccinee sera.

Figure 7. Genetic makeup of YFV strains at polymorphic sites 1 and 2.

Amino acid-based tree depicting E proteins from representative YFV strains (scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site). Colored ranges denote viral origin and clade(s): i) Old World (light blue), ii) SA1 (South American genotype 1, brown). SA2 (South American genotype 2, beige). Black stars indicate YFV sequences used in this study. The inner ring is color-coded according to the continent of origin. Note that all sequences of apparent Asian or European origin are ex-African (if clustering with Old World) or ex-South American (if clustering with SA1). N/A, not applicable. Sequence features are represented with a square (Site 1: H67 A83), circle (Site 2a: predicted glycan at N269), or star (Site 2b: K272). Features present in sequence are represented with filled shapes. The outer char bar denotes the number of strains being represented at each branch of the tree.

Discussion

Mass vaccination campaigns have historically been, and remain, a vital tool in the public health armamentarium against YFV. Despite considerable efforts, however, attaining sufficient population vaccine coverage in endemic areas and ‘surging’ vaccination during epidemics has proven challenging. In Brazil, shortages in the locally manufactured and highly effective YFV-17D vaccine represent one major logistical hurdle to widespread vaccination and necessitated the use of dose-sparing strategies to maximize coverage during the 2016–19 epidemic (Boëte, 2016; de Oliveira Figueiredo et al., 2020). A further challenge to maintaining long-term population immunity is the World Health Organization’s recommendation that individuals receive a single lifetime dose of the vaccine. The emerging consensus points instead to the need for a second dose to boost waning immunity and mitigate the demonstrated risk of re-infection in YF-vaccinated individuals (Campi-Azevedo et al., 2019b, 2019a; Estofolete and Nogueira, 2018; Vasconcelos, 2018).

Measurement of antiviral neutralizing antibodies in human sera is the most widely used biomarker for YFV vaccine immunogenicity and provides a key correlate of vaccine protection (Mason et al., 1973; Plotkin, 2010). Specifically, YFV neutralizing titers in vaccinee sera are conventionally determined using the YF-17D vaccine strain or one of its variants (e.g., YF-17DD), ultimately derived from the virulent African strain, YFV-Asibi. However, despite evidence for the antigenic distinctiveness of African and South American strains as far back as 1960 (Clarke, 1960), the choice of indicator viral strain on the determination and interpretation of serum neutralizing titers in South American vaccinees has not been systematically explored. Here, we found that neutralizing antibody responses induced by YF-17D vaccination were markedly attenuated against South American strains YFV-ES-504 and YFV-Bolivia (belonging to genotypes I and II, respectively) (Figures 1 and S4). Because the genetic features of these sequences that influence neutralization sensitivity appear to be shared by most South American YFV strains (see below), we conclude that available serological data likely overestimate the potency and longevity of neutralizing antibody responses in South American vaccinees.

We genetically mapped the reduced neutralization sensitivity of YFV-ES-504 versus YFV-17D to the central domain II (DII) of the E protein (Figure 4), which is the major target of polyclonal neutralizing antibody responses in flavivirus vaccinees and convalescents (Vratskikh et al., 2013; Wec et al., 2020). Further genetic dissection of DII revealed two polymorphic sites. The first (Site 1) is a fusion loop-proximal sequence containing or overlapping the epitopes of the protective nAb, 5A (Lu et al., 2019) (Figure 4C) and those of a large panel of 5A-competing nAbs we recently isolated from YF-17D vaccinees (Wec et al., 2020) (Figures 2 and S3 and Data S1). Site 2 is a sequence at the apex of the kl loop, which forms part of the hinge region between DI and II (Figure S5A–B). We found that the 5A-competing, DII-specific nAbs were much more sensitive to the changes at Site 1 than to those at Site 2 (Figures 5B–C and S3), whereas YF-17D vaccinee sera displayed the opposite pattern, especially in the YFV-17D genetic background (Figure 5D–E). Nevertheless, combining the Site 1 and Site 2 polymorphisms afforded the largest changes in YFV neutralization by vaccinee sera (Figure 5D–E). These findings suggest that YF-17D vaccination elicits currently undefined mAb specificities with key roles in viral neutralization.

We provide genetic and biochemical evidence for two determinative changes at Site 2 associated with YFV-17D→ES-504 neutralization resistance: (i) the acquisition of an N–linked glycosylation site at Asn 269 that is associated with near-complete N–linked glycan occupancy in insect-cell expressed soluble E protein and partial occupancy in mammalian cell- expressed and viral particle-bound full-length E; and (ii) an Asn-to-Lys change at residue 272 (N272K) (Figure 6). Although N–glycosylation of YFV E has been sporadically observed (e.g., at Asn 153 in the YFV-17DD vaccine variant only (Post et al., 1992) (Data S2), this protein is generally reported to not bear any N–glycans, possibly because only African clade sequences have been used in most prior analyses (Carbaugh and Lazear, 2020; Post et al., 1992). Indeed, we could find only one report in which the presence of a sequon at Asn 269 was noted in five South American YFV sequences (Chang et al., 1995). Here, we show that predicted N–glycosylation at Asn 269 is almost universally observed in South American YFV strains, including both genotypes I and II and in both ‘Old’ and ‘New’ genotype I strains (Carrington and Auguste, 2013; Gómez et al., 2018), but not in any African or other Old World YFV strains sequenced to date (Figure 7). Intriguingly, South American genotype I and II strains possess distinct Asn 269 sequons (NNS and NGS, respectively), raising the possibility that they may have independently evolved this feature. The N272K change at the DI-DII hinge in the YFV E protein has not been previously described, to our knowledge.

An extensive body of work has shed light on the patterns and functional significance of N–linked glycosylation in flavivirus E proteins (Carbaugh and Lazear, 2020; Yap et al., 2017). Although the number of N–glycans vary in a virus-, strain-, and lineage-dependent manner, recurrent N–glycosylation is only observed at two positions: Asn 67 in DII and Asn 153/154 in the variable ‘150-loop’ sequence in DI. Current evidence indicates that N–linked glycans at Asn 67 and/or Asn 154 play cell type- and host-dependent roles in flavivirus multiplication, by virtue of which they can impact virulence, pathogenesis, and mosquito-borne transmission (Carbaugh and Lazear, 2020; Yap et al., 2017). To our knowledge, N–glycosylation at Asn 269 in the DI-DII hinge has not been observed in any other flavivirus E protein to date. Although more work is needed to understand the molecular basis and implications of partial glycan occupancy associated with the Asn 269 sequon in mammalian cell-expressed YFV ES-504 E (Figure 6B), we speculate that its acquisition by South American YFV E proteins was an early adaptation event that afforded the virus a selection advantage in its new sylvatic environments in the New World.

Our observation that two distinct changes at the DI–DII hinge in the kl loop could independently impact viral neutralization sensitivity by polyclonal sera raises the possibility that they induce allosteric changes in the E protein and influence the structural dynamics of the entire glycoprotein shell (“breathing”) in a manner that regulates the availability of other epitopes, as has been documented most extensively for dengue virus (DENV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) (Barba-Spaeth et al., 2016; Brien et al., 2010; Dejnirattisai et al., 2015; Dowd et al., 2015; Gallichotte et al., 2018; Goo et al., 2017, 2018; Martinez et al., 2020; Messer et al., 2012; Sukupolvi-Petty et al., 2013; VanBlargan et al., 2021; Wahala et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2013). Indeed, the asymmetric effects of the YFV-17D/ES-504 Site 2 chimeras on serum neutralization (Figure 5C–D) appear consistent with such allosteric models. The analysis of predicted and known B-cell epitopes in YFV E and its structural superposition with other flavivirus E:nAb complexes (Berman et al., 2000) identified multiple nAb footprints in proximity to residues in the kl loop (Figure S5C–L and Data S3). Several of these nAbs recognize complex quaternary epitopes that span multiple E subunits in the intact viral particles of other flaviviruses (reviewed in (Dussupt et al., 2020; Sevvana and Kuhn, 2020). Indeed, previous work with both YFV and DENV suggests that quaternary epitope binders may constitute a substantial fraction of the neutralizing activity in human immune sera (de Alwis et al., 2012; Vratskikh et al., 2013). We anticipate that such antibodies are underrepresented in our nAb panel, which was isolated by B-cell sorting with a largely monomeric recombinant sE protein (Wec et al., 2020).

Although the genetic distinctiveness of the South American and African YFV clades has been previously noted, the implications of specific clade- and lineage-dependent differences for viral transmission, virulence, and immune evasion have not been investigated. Here, we identify conserved genetic and biochemical features unique to South American YFV strains that influence their reduced susceptibility to nAbs in human vaccinee sera. These results argue for a reevaluation of current approaches to YFV immunological surveillance in South America. They also point to an urgent need to expand and update our understanding of the quantitative relationship(s) among vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies, T cells, and vaccine-mediated protection against YFV, especially in light of the genotype-dependent effects uncovered herein. Finally, our findings provide a roadmap to explore updates to the current gold-standard vaccine that forms the basis of WHO’s comprehensive global strategy to eliminate YF epidemics (EYE) (WHO, 2018).

Limitations of the study

We note the following limitations. First, the significance of the reduced neutralizing potency of vaccine-elicited antibodies for protection against YFV ES-504 and other viruses from South American clades is unknown and needs to be investigated. Second, most of our genetic mapping experiments were conducted with surrogate reporter viral particles, and thus, future studies with authentic viruses engineered at Sites 1 and 2 are warranted. Third, our analyses with RVPs bearing chimeric E proteins may not fully capture differences observed with the authentic agents.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact.

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Kartik Chandran.

Materials Availability.

Plasmids in this study, together with documenting information, will be made available upon request and following execution of a UBMTA between Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the recipient institution.

Data and Code Availability.

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

The U.S. cohort.

This study group consisted of 17 vaccinees (age range, 24 to 77 years; median age, 43 years; 8 female and 9 male) (Table S1). Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained before vaccination. Study subjects (donors 1 to 3) were vaccinated with the YFV-17D Stamaril vaccine. Heparinized blood (50 to 100 cc) was obtained from subjects before vaccination and for over one year following vaccination as described previously (Wec et al., 2020). In addition, from donors 2 and 3 after 3 and 2 years respectively. Additional consented volunteers (donors 9 to 18) with history of YFV vaccination (Stamaril or YF-Vax, both YF-17D-204 virus strain) were recalled for plasma collection at the indicated timepoints ranging up to 20 years post first YFV vaccination. Samples were processed in the Immune Monitoring and Flow Cytometry Core laboratory at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College to obtain plasma and to isolate peripheral blood-derived B cells. Isolated cells and plasma were stored frozen in aliquots at − 80 °C. This study complies with all relevant ethical regulations for work with human participants and was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, and Dartmouth College. Additional blood samples were collected from healthy adult volunteers after giving informed consent (donors 19 to 22) with history of YFV vaccination (Stamaril or YF-Vax). Blood was drawn by venipuncture to collect serum. Serum was centrifuged, aliquoted and stored at −80°C. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (IRB number 2016–6137).

The Brazilian cohort.

This study group consisted of 29 vaccinees (age range, 24 to 74 years; median age, 44 years; 13 female and 16 male) (Table S1). Study subjects (donors 4 to 8 and donors 23 to 46) were selected between October 2011 and April 2014, among people who attended the Reference Centre of Special Immunobiologicals at the Clinics Hospital in the University of São Paulo (CRIE-HCFMUSP). Individuals looking for the attenuated yellow fever vaccine, either HIV-positive or not, were evaluated by medical personnel and invited to participate in the study, if they were naïve for the vaccine. They were between 18 and 59 years old and should not have auto-immune diseases or other health issues that could impact on the vaccination. A team researcher clarified the terms of the study, presenting the aims of the research, the potential risks, and the procedures. The individuals who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. The study subjects were then vaccinated with the YF-17DD attenuated vaccine (Biomanguinhos, Fiocruz), and blood was drawn from 5 donors (donors 4 to 8) over 1 year. Another 24 donors (donor 23 to 46) had their first vaccine dose at the same center and samples were collected one to two years post-vaccination. Whole blood from vaccinees was collected in EDTA tubes. For plasma separation samples were centrifuged at 1800 rpm for 10 min. The plasma was collected and centrifuged again at 2800 rpm for 10 min to remove cellular debris. After centrifugation, plasma was aliquoted and stored at −20°C for further use. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Project Analysis (CAPPesq) from the Clinics Hospital at the University of São Paulo (CAAE: 83631318.000.068).

Cells.

Human hepatoma-derived Huh 7.5.1 cells (originally from Dr. Frank Chisari and received from Dr. Jan Carette) were passaged using 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA solution (Gibco) every three to four days and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM high glucose, Gibco) complemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, heat-inactivated, Atlanta Biologicals), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S, Gibco), 1% Gluta-MAX (Gibco) and 25 mM HEPES (Gibco).

Human embryonal kidney 293FT cells, purchased from Thermo Fisher, were passage every 3 to 4 days using 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA solution (Gibco) and maintained in DMEM high glucose (Gibco) complemented with 10% FBS (heat-inactivated, Atlanta Biologicals), 1% P/S (Gibco), 1% Gluta-MAX (Gibco) and 25 mM HEPES (Gibco).

Vero cells (ATCC-CCL81) were maintained in Earle’s 199 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 0.25% sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich), and 40 mg/mL gentamicin (Gibco) in an incubator at 37°C with wet atmosphere and 5% CO2.

C6/36 cells, kindly provided by Dr. Anna-Bella Failloux (Institut Pasteur, Paris), were grown in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Gibco), supplemented with 5% FBS, 10% tryptose broth, and 40 mg/mL gentamicin in an incubator at 28°C.

Virus generation.

Yellow Fever virus 17D (YFV-17D) was obtained from BEI Resources (Cat# NR-115). Huh 7.5.1 cells were seeded into 15cm dishes and confluent cells were infected using 90 μL of passage 2 stock of the YFV-17D supernatant in 3 mL infection media (DMEM low glucose (Gibco), 7% FBS (heat-inactivated, Atlanta Biologicals), 1% P/S (Gibco), 1% Gluta-MAX (Gibco), 25 mM HEPES (Gibco)) for 1 hour at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Three days later supernatant was harvested and cleared from cell debris by centrifugation twice at 4,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The cleared viral supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C.

YFV ES-504 was isolated from the blood of a non-human primate found dead in Espírito Santo, Brazil, in February 2017 (Bonaldo et al., 2017). The viral stock was produced in C6/36 cells. Cells were seeded at a density of 80,000 cells/cm² in a T-75 flask 24 hours before infection with 3 mL of viral isolate suspension. After 1 h incubation at 28°C, 40 mL of supplemented Leibovitz’s L-15 medium was added. After 8 days, the supernatant was centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

YFV-17DD was recovered from the lyophilized vaccine ampoule produced by Biomanguinhos-FIOCRUZ/RJ with supplemented Earle’s 199 medium. The viral stock was obtained in Vero cells seeded at 62,500 cells/cm² in a T-150 culture flask. Viral adsorption was carried out for 1 h, after which 40 mL of medium was added. Cells were observed daily until the cytopathic effect was detectable. The cell supernatant was centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Reporter virus particle (RVP) generation.

West Nile virus (WNV) subgenomic replicon- expressing plasmid pcDNA6.2-WNIIrep-GFP/zeo was a generous gift from Ted Pierson (Pierson et al., 2006). The structural proteins C, prM and E of YFV-17D, ES-504, China and Bolivia (Genbank: X03700.1, KY885000.2, KU921608.1 and KF907504.1 respectively) as well as their mutated forms were synthesized and codon-optimized for expression in human cells by Epoch Life Science, Inc. and subcloned into the pCAGGS vector for mammalian expression. For RVPYFV- 7D/ES-504 chimeras, DI (amino acid residues 1–51, 132–192 and 280–295), DII (residues 52–131 and 193–279) and DIII (residues 296–394) were exchanged. For RVP17D or RVPES-504 carrying site mutations, Site 1 (residues 67 and 83) and Site 2 (residues 270–272 DNN/NSK were interchanged (Figure 4). For RVP17D NSN/NDK mutations at 270–272 were introduced accordingly (Figure 6). Amino acid labelling according to the E protein sequence of YFV-17D. 293FT cells (Thermo Fisher) were transfected with 12 μg of total DNA per 15 cm plate in a ratio of 1:3 using the WNV replicon plasmid and the respective virus C-prM-E plasmid. Eight hours post-transfection, media was exchanged to low glucose DMEM (Gibco) media containing 5% FBS (heat-inactivated, Atlanta Biologicals) and 25mM HEPES (Gibco). After 3 to 4 days at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the cell supernatant containing RVPs was harvested and to remove the cell debris centrifuged twice for 15 min at 4,000 rpm at 4 °C. The viral supernatant was pelleted using a SW28 rotor (Beckman Coulter) in a Beckman Coulter Optima LE-80K ultracentrifuge for 4 hours at 4 °C through a 2 mL cushion of 30% (v/v) D-sucrose in PBS (pH 7.4). The pellet was resuspended overnight on ice in 100 μl PBS (pH 7.4), aliquoted and stored at −80°C till further use.

Production of recombinant YFV antigens.

The coding sequence for the entire prM and soluble E (sE) regions (amino acid residues 122–678 of the YFV polyprotein) of the YFV Asibi Strain (Uniprot ID: Q6DV88) or YFV ES-504 strain (Uniprot ID: A0A1W6I1A1) were cloned into an insect expression vector encoding a C-terminal double strep tag, pMT-puro. The expression construct design was based on previously published structures of flavivirus antigens (Modis et al., 2003, 2005; Rey et al., 1995). The YFV prM/E constructs were used to generate an inducible, stable Drosophila S2 line. Protein expression was induced with addition of copper sulfate and allowed to proceed for 5 to 7 days. Recombinant proteins were affinity purified from the culture supernatant with a StrepTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) and an additional purification step was carried out using size-exclusion chromatography step using an S200 Increase column (GE Healthcare). The final protein preparations were stored in PBS (pH 7.4) supplemented with an additional 150 mM NaCl, aliquoted and stored at −70°C.

Monoclonal antibodies.

The isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies used in this study have been described previously in detail in (Wec et al., 2020). In short, IgGs were expressed in S. cerevisiae cultures grown in 24-well plates, as described previously (Bornholdt et al., 2016). After 6 days, the cultures were harvested by centrifugation and IgGs were purified by protein A-affinity chromatography. The bound antibodies were eluted with 200 mM acetic acid/50 mM NaCl (pH 3.5) into 1/8th volume 2 M Hepes (pH 8.0) and buffer-exchanged into PBS (pH 7.0).

METHOD DETAILS

Biolayer Interferometry Kinetic Measurements (BLI).

For monovalent apparent KD determination, IgG binding to recombinant YFV E antigen was measured by biolayer interferometry (BLI) using a FortéBio Octet HTX instrument (Molecular Devices). The IgGs were captured (1.5 nm) to anti-human IgG capture (AHC) biosensors Molecular Devices) and allowed to stand in PBSF (PBS with 0.1% w/v BSA) for a minimum of 30 min. After a short (60 s) baseline step in PBSF, the IgG-loaded biosensor tips were exposed (180 s, 1000 rpm of orbital shaking) to YFV E antigen (100 nM in PBSF) and then dipped (180 s, 1000 rpm of orbital shaking) into PBSF to measure any dissociation of the antigen from the biosensor tip surface. Data for which binding responses were > 0.1 nm were aligned, inter-step corrected (to the association step) and fit to a 1:1 binding model using the FortéBio Data Analysis Software, version 11.1.

Microtiter neutralization assays.

Plasmas were serially diluted in DMEM high glucose medium (Gibco) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Atlanta Biologicals), 1% Gluta-MAX (Gibco), 1% P/S (Gibco) and 25 mM HEPES (Gibco). Dilutions were incubated at room temperature (RT) with YFV-17D or RVPs for one hour. Monoclonal antibodies at a concentration of 10nM were pre-incubated with RVPs for 1 hour at RT before adding to cell monolayers. The antibody-virus mixture was added in triplicates to 96-well plates (Costar, cat# 3595) containing 5,000 Huh 7.5.1 cell monolayers seeded the day before and incubated for 2 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Afterwards, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 10 mins washed with PBS (pH 7.6), three times. Fixed YFV-17D infected-cells were incubated with a pan-flavivirus mouse mAb 4G2 (ATCC) at 2 μg/ml in PBS containing 3% nonfat dry milk powder (BioRad), 0.5% Triton X-100 (MP Biomedicals), and 0.05% Tween 20 (Fisher Scientific) for one hour at RT. Afterwards, cells were washed and incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen) at a 1:500 dilution for one hour at RT. Finally, YFV-17D and RVP infected cells were washed and nuclei were stained with Hoechst-33342 (Invitrogen) in a 1:2,000 dilution in PBS. Viral infectivity was measured by automated enumeration of Alexa Fluor 488-positive or GFP-positive cells from captured images using a Cytation-5 automated fluorescence microscope (BioTek) and analyzed using the Gen5 data analysis software (BioTek). The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the plasma was calculated using a nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism software. Viral neutralization data were subjected to nonlinear regression analysis to extract the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values (4-parameter, variable slope sigmoidal dose-response equation; GraphPad Prism).

Focus Reduction neutralization (FRNT) assays.

Virus-specific neutralizing responses were titrated as previously described in (Magnani et al., 2017). Briefly, sera or antibodies were serially diluted in Earle’s 199 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 5% FBS and incubated 1 h at 37°C with YFV-17DD or -ES504. After incubation, the antibody-virus or sera-antibody mix was added to 96-well plates in triplicates containing Vero CL81 cells monolayers. Plates were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. The inocula were discarded, and the cells were overlaid with viral growth medium containing 1% CMC (carboxymethyl cellulose). Plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 2–3 days after which cells were fixed with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) at room temperature for 30 min, washed twice with PBS, and treated with CytoPerm Wash (BD Biosciences) for 5 min, followed by 1 h incubation with the primary antibody 4G2 (MAB10216, EMD Millipore) diluted 1:2,000. Afterwards, plates were washed three times, followed by an hour-long incubation with a secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to peroxidase (KPL) (SeraCare) or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (115035146, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Detection proceeded with the addition of True-Blue Peroxidase Substrate (KPL), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The number of foci was analyzed with a C.T.L. S6 Ultimate-V Analyzer (ImmunoSpot). The endpoint titer was determined to be the highest dilution with a 50% reduction (IC50) in the number of plaques compared to control wells.

Mass spectrometry of glycopeptides.

YFV-ES-504 and YFV-Asibi proteins (20 μg) were reduced for 1 hour in 200 μl of a buffer containing 8 M urea and 5 mM DTT and were alkylated with 20mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 30 min. Next, the protein solution was added to Vivaspin columns (10 kDa) and washed three times with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0, for buffer exchange. Finally, 1 μg of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) diluted in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added to the samples and the mixture was incubated for 18 h at 37°C. After incubation, the peptide solutions were dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Prior to mass spectrometry analysis, samples were desalted using a 96-well plate filter (Orochem) packed with 1 mg of Oasis HLB C-18 resin (Waters). Briefly, the samples were resuspended in 100 μl of 0.1% TFA and loaded onto the HLB resin, which was previously equilibrated using 100 μl of the same buffer. After washing with 100 μl of 0.1% TFA, the samples were eluted with a buffer containing 70 μl of 60% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA and then dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Samples were resuspended in 10 μl of 0.1% TFA and loaded onto a Dionex RSLC Ultimate 300 (Thermo Scientific), coupled online with an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (Thermo Scientific). Chromatographic separation was performed with a two-column system, consisting of a C-18 trap cartridge (300 μm ID, 5 mm length) and a picofrit analytical column (75 μm ID, 25 cm length) packed in-house with reversed-phase Repro-Sil Pur C18-AQ 3 μm resin. Peptides were separated using a 135 min linear gradient consisting of 0–32% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid over 120 min followed by 5 min of 32–80% acetonitrile and 5 min of 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The mass spectrometer was set to acquire spectra in a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Briefly, the full MS scan was set to 400–2000 m/z in the orbitrap with a resolution of 120,000 (at 200 m/z) and an AGC target of 4×10e5. MS/MS was performed in the orbitrap using an AGC target of 5×10e4 and an HCD collision energy of 30 for fragmentation of glycopeptide ions. Protein Metrics software (Version 3.10, Byonic™) was used to extract the glycopeptide fragmentation data from raw files. N-glycan library from Protein Metrics was used to identify the glycans, together with glycopeptide fragmentation data, which contains b, y and oxonium ions. Glycopeptide with its corresponding extracted ion chromatographic (XIC) area was used to calculate the relative amount, by dividing to the summation of all XIC from all different glycans and unoccupied with an identical peptide sequence.

Co-Immunoprecipitations, PNGase F treatment, and Western blotting.

RVPs were produced as described above. E proteins were immunoprecipitated with mAb 4G2 (ATCC) immobilized on Protein G magnetic beads (Dynabeads™ Protein G; Invitrogen). Briefly, 50 μL of Dynabeads were incubated with 5 μg mAb 4G2 overnight at 4°C. Beads were then washed with PBS + 0.3% BSA and subsequently rotated for 4 h at 4°C with 300 μL RVPs. Beads were washed 3 times with PBS and resuspended in 50 μL PBS. Immunoprecipitates and a concentrated preparation of a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus bearing Ebola virus GP (Wong et al., 2010) were treated with 2 μL PNGase F (New England Biolabs) under nondenaturing conditions for 24 h. Samples were analyzed using Bolt 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membranes using the iBlot Dry Blotting System (Invitrogen). For detection, mAb 4G2 was conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) using the EZ-Link Plus Activated Peroxidase Kit (Thermo Scientific). E proteins were then labeled with the mAb 4G2-HRP for 1 h, followed by 5 washes with water. Membranes were developed using the Pierce ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific) and images were obtained using the iBright FL1500 Imaging System (Invitrogen). Pre-stained Chameleon Duo Protein Protein Ladder (Li-Cor) was used as a marker

To generate infected cell lysates, Vero cells were seeded 24 h prior to infection with YFV ES-504 at MOI of 0.5 PFU per cell. After 1 h incubation at 37°C, viral inocula were removed and cells were overlaid with 3 mL of supplemented Earle’s 199 medium. The supernatants were discarded after 48 h incubation, and cell monolayers were lysed using the cOmplete Lysis-M buffer (Roche) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Cell lysates were treated with PNGase F for 24 h as above. Samples were analyzed using 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes as above. E proteins were labeled with mAb 4G2 (EMD Millipore) for 2 h, followed by washing with TBS-T buffer (TBS pH 7.4 with 0.1 % Tween 20). Finally, PVDF membranes were treated with a secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated with HRP (KPL). Blots were developed with the ECL Prime Western Blotting System (Amersham) and images captured with the Bio-Rad gel documentation system. Broad-range prestained SDS-PAGE Standards (Bio-Rad) were used as a marker.

Phylogenetic tree assembly.

We first collected an initial envelope protein sequence dataset comprising 695 yellow fever strains using VIPR (Pickett et al., 2012). We filtered out 335 viral protein sequences with unidentified residues and non-canonical starting and end positions, using as a reference the envelope protein corresponding to the 17D vaccine strain. Next, we filtered out duplicates mapping to the same GenBank identifier, envelope proteins without information regarding their country of origin and envelope proteins corresponding to vaccine strains (except 17D and 17DD vaccines strains). The remaining 281 envelope proteins were further filtered based on pairwise sequence identity (100% sequence identity) and geographical location, keeping only one envelope protein representing identical envelope proteins from different viral strains isolated in the same country. Sequence filtering was performed with CD-HIT (Li and Godzik, 2006). The final non-redundant set of envelope proteins involved 82 yellow fever strains (including vaccine strains 17D and 17DD). Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree reconstruction was performed using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) and PhyML (Guindon et al., 2009) through phylogenetic.fr (Dereeper et al., 2008). Tree visualization was performed with iTol (Letunic and Bork, 2016).

Modeling of the glycosylated loop in the envelope protein structure of 17D YFV.

We used the modeller plugin (Sali and Blundell, 1993) within Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) to model the glycan containing loop in the prefusion state of the 17D envelope dimer structure (missing residues 269 to 272) (Lu et al., 2019). For the glycan, we structurally superimposed the glycosylated N153 found in the envelope protein of Flavivirus Dengue 2 (Rouvinski et al., 2015) to Asn 269 of the 17D YFV envelope protein structure. We chose a loop conformation compatible with the glycosylation that does not lead to steric clashes between the glycan moiety and the envelope dimer.

Structural alignment of Flavivirus E proteins complexed with mAbs and the 17D YFV with the modeled glycan.

We structurally aligned the experimentally determined monomeric structure of E proteins (complexed with mAbs) from different flaviviruses and the monomeric structure of the 17D E protein (with the modeled glycan) using Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). Steric clashes between the modeled glycan and the mAbs (bound to the structurally aligned flavivirus E proteins) were identified using Chimera.

B-cell epitope annotation in the envelope protein of YFV.

All experimentally known B-cell epitopes on the envelope of YFV strains were extracted from IEDB (Vita et al., 2019). In addition, we predicted B-cell epitopes on the 17D envelope protein using BepiPred-2 (Jespersen et al., 2017).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The n number associated with each dataset in the figures indicates the number of biologically independent samples. The number of independent experiments and the measures of central tendency and dispersion used in each case are indicated in the figure legends. Dose-response neutralization curves were fit to a logistic equation by nonlinear regression analysis. Statistical comparisons are indicated in the Figure Legends. All curve-fitting and statistical testing was performed in GraphPad Prism 8.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. mAb reactivity against YFV 17D and ES-504. Related to Figure 2. Comprehensive analysis of mAbs: antibody competition, heavy and light chain, BLI reactivity and neutralization of RVPs and authentic virus.

Data S2. A subset of YFV strains from the Americas consistently show particular amino acid variants at the 5A epitope and the kl loop. Related to Figure 7. Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of the E protein from 82 non-redundant YFV strains representing the sequence space of 281 E proteins.

Data S3. The kl loop of YFV E protein overlaps with mAb-binding regions in other flavivirus E proteins. Related to Figure 4. List of PDB entries describing flavivirus E proteins bound to mAbs and whether the modelled glycan in ES-504 would sterically clash with the superimposed mAb.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | ThermoFisher | Cat# A-11001; RRID:AB_2534069 |

| 4G2 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_J890 |

| 4G2 | EMD Millipore | Cat# MAB10216; RRID:AB_827205 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), HRP Conjugated - KPL | SeraCare | Cat # 074–1806: RRID:AB_2891080 |

| Peroxidase-AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 115035146; RRID:AB_2307392 |

| All other monoclonal antibodies | Wec et al. 2020 | N/A |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| YFV-17D | BEI Resources | Cat# NR-115 |

| YFV-ES504 | Bonaldo et al., 2017 | N/A |

| YFV-17DD | Bio Manguinhos-FIOCRUZ/RJ | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Sera of Stamaril vaccinees (donors 1 to 3) | Wec et al. 2020 | N/A |

| Sera of Stamaril or YF-Vax vaccinees (donors 9 to 18) | This study | N/A |

| Sera of 17DD vaccinees (donors 4 to 8, donors 23 to 46) | This study | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Recombinant YFV Asibi antigen | Wec et al. 2020 | N/A |

| Recombinant YFV ES504 antigen | Wec et al. 2020 | N/A |

| DL-Dithiothreitol | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# D0632 |

| Iodoacetamide | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# I6125 |

| Ammonium bicarbonate | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# A6141 |

| Sequencing grade modified trypsin | Promega | Cat# V5111 |

| Acetonitrile OptimaTM LC/MS grade | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A955–4 |

| Pierce™ trifluoroacetic acid sequencing grade | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 28904 |

| Oasis HLB 30μm | Waters | Cat# 186007549 |

| Repro-Sil Pur C18-AQ 3μm | Dr. Maisch GmbH | Cat# r13.aq.0003 |

| Pierce™ formic acid LC/MS grade | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 28905 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| S-Trap™ micro columns | Protifi | Cat# C02-micro-80 |

| 96-well filter plate | Orochem | Cat# OF1100 |

| C-18 Trap Cartridge | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 160454 |

| Picofrit analytical column | Polymicro Technologies | Cat# 1068150019 |

| Dynabeads™ Protein G | Invitrogen | Cat# 10004D |

| Deposited data | ||

| Does not apply | ||

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Human: hepatoma Huh7.5.1 | Dr. Jan Carrette (Originally from Dr. Frank Chisari) | N/A |

| Human: 293FT | ThermoFisher | Cat# R70007; RRID: CVCL_6911 |

| African green monkey: Vero cells | ATCC | Cat# CCL81; RRID:CVCL_0059 |

| Aedes albopictus: C6/36 cells | Dr. Anna-Bella Failloux (Institut Pasteur, Paris) | N/A |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Does not apply | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Does not apply | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pcDNA6.2-WNIIrep-GFP/zeo | Pierson et al., 2006 | N/A |

| pcDNA6.2-WNI-CPrME (Strain NY99) | Pierson et al., 2006 | N/A |

| pCAGGS vectors carrying YFV strains/mutants/chimeras | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism (version 8.3.0(538)) | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Adobe Photoshop (version 21.1.3) | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/ |

| Adobe Illustrator (version 24.1.3) | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/ |

| Pymol 2.4 | Schrödinger, LLC | https://pymol.org/2/ |

| SnapGene | SnapGene | https://www.snapgene.com/ |

| NetNGlyc 1.0 Server | Gupta and Brunak, 2002 | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/ |

| Chimera | Pettersen et al., 2004 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ |

| CD-HIT | Li and Godzik, 2006 | http://weizhongli-lab.org/cd-hit/ |

| MUSCLE | Edgar, 2004 | http://www.drive5.com/muscle/ |

| PhyML | Guindon et al., 2009 | https://github.com/stephaneguindon/phyml |

| Phylogeny.fr | Dereeper et al., 2008 | http://www.phylogeny.fr |

| iTol | Letunic and Bork, 2016 | https://itol.embl.de |

| Modeller | Sali and Blundell, 1993 | https://salilab.org/modeller/ |

| BepiPred-2 | Jespersen et al., 2017 | http://tools.iedb.org/bcell/ |

| Byonic™ | Protein Metrics | https://proteinmetrics.com/ |

| Other | ||

| Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader | BioTek | N/A |

| C.T.L. S6 Ultimate-V Analyzer | ImmunoSpot | N/A |

| Database: VIPR | Pickett et al., 2012 | https://www.viprbrc.org/brc/home.spg?decorator=vipr |

| Database: PDB | Berman et al. 2000 | https://www.rcsb.org |

| Database: IEDB | Vita et al., 2019 | https://www.iedb.org |

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Gutierrez, E. Valencia and L. Polanco for laboratory management and technical support. We thank Dr. T.C. Pierson for his provision of the WNV-based RVP system. This work was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grant R01AI132633 (to K.C.), “Preventing and Combating the Zika Virus” MCTIC/FNDCT-CNPq/MEC-CAPES/MS-Decit. (Grant 440865/2016-6) (to M.C.B.) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (Grant 312446/2018) (to M.C.B.). M.C.B. is a recipient of CNPq fellowship for Productivity in Technological Development and Innovative Extension (Grant 309471/2016-8). Si.Si. and St.St. were supported by the Leukemia Research Foundation (Hollis Brownstein New Investigator Research Grant), AFAR (Sagol Network GerOmics award), Deerfield (Xseed award) and the NIH Office of the Director (1S10OD030286-01). Y.S. gratefully acknowledges the NIH grant R01GM129350-04. C.A.C. is a recipient of the PhD scholarship provided by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior Brasil (CAPES). A.L.T. was partially supported by NIH training grant 2T32GM007288-45 (Medical Scientist Training Program) at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

K.C. is a member of the scientific advisory boards of Integrum Scientific, LLC, Biovaxys Technology Corp., and the Pandemic Security Initiative of Celdara Medical, LLC. A.Z.W., M.S., and L.M.W. are/were employees of Adimab, LLC, and may hold shares in Adimab, LLC. L.M.W. is an employee of Adagio Therapeutics, Inc., and holds shares in Adagio Therapeutics, Inc. C.L.M and Z.A.B are employees of Mapp Biopharmaceutical, Inc.

Inclusion and Diversity

The author list of this paper includes contributors from the location where the research was conducted who participated in the data collection, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of the work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- de Alwis R, Smith SA, Olivarez NP, Messer WB, Huynh JP, Wahala WMPB, White LJ, Diamond MS, Baric RS, Crowe JE, et al. (2012). Identification of human neutralizing antibodies that bind to complex epitopes on dengue virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 7439–7444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Spaeth G, Dejnirattisai W, Rouvinski A, Vaney M-C, Medits I, Sharma A, Simon-Lorière E, Sakuntabhai A, Cao-Lormeau V-M, Haouz A, et al. (2016). Structural basis of potent Zika-dengue virus antibody cross-neutralization. Nature 536, 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett ADT, and Teuwen DE (2009). Yellow fever vaccine - how does it work and why do rare cases of serious adverse events take place? Curr. Opin. Immunol 21, 308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat TN., Weissig H., Shindyalov IN., and Bourne PE. (2000). The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boëte C.(2016). Yellow fever outbreak: O vector control, where art thou? J. Med. Entomol 53, 1048–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohning K, Sonnberg S, Chen H-L, Zahralban-Steele M, Powell T, Hather G, Patel HK, and Dean HJ (2021). A high throughput reporter virus particle microneutralization assay for quantitation of Zika virus neutralizing antibodies in multiple species. PLoS ONE 16, e0250516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaldo MC, Gómez MM, Dos Santos AA, de Abreu FVS, Ferreira-de-Brito A, de Miranda RM, de Castro MG, and Lourenço-de-Oliveira R.(2017). Genome analysis of yellow fever virus of the ongoing outbreak in Brazil reveals polymorphisms. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 112, 447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornholdt ZA, Turner HL, Murin CD, Li W, Sok D, Souders CA, Piper AE, Goff A, Shamblin JD, Wollen SE, et al. (2016). Isolation of potent neutralizing antibodies from a survivor of the 2014 Ebola virus outbreak. Science 351, 1078–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradt V, Malafa S, von Braun A, Jarmer J, Tsouchnikas G, Medits I, Wanke K, Karrer U, Stiasny K, and Heinz FX (2019). Pre-existing yellow fever immunity impairs and modulates the antibody response to tick-borne encephalitis vaccination. Npj Vaccines 4, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brien JD, Austin SK, Sukupolvi-Petty S, O’Brien KM, Johnson S, Fremont DH, and Diamond MS (2010). Genotype-specific neutralization and protection by antibodies against dengue virus type 3. J. Virol 84, 10630–10643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi-Azevedo AC, Reis LR, Peruhype-Magalhães V, Coelho-Dos-Reis JG, Antonelli LR, Fonseca CT, Costa-Pereira C, Souza-Fagundes EM, da Costa-Rocha IA, Mambrini JV de M., et al. (2019a). Short-Lived Immunity After 17DD Yellow Fever Single Dose Indicates That Booster Vaccination May Be Required to Guarantee Protective Immunity in Children. Front. Immunol 10, 2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi-Azevedo AC., Peruhype-Magalhā es V., Coelho-Dos-Reis JG., Antonelli LR., Costa-Pereira C., Speziali E., Reis LR., Lemos JA., Ribeiro JGL., Bastos Camacho LA., et al. (2019b). 17DD Yellow Fever Revaccination and Heightened Long-Term Immunity in Populations of Disease-Endemic Areas, Brazil. Emerging Infect. Dis 25, 1511–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbaugh DL, and Lazear HM (2020). Flavivirus envelope protein glycosylation: impacts on viral infection and pathogenesis. J. Virol 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington CVF, and Auguste AJ (2013). Evolutionary and ecological factors underlying the tempo and distribution of yellow fever virus activity. Infect. Genet. Evol 13, 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang GJ, Cropp BC, Kinney RM, Trent DW, and Gubler DJ (1995). Nucleotide sequence variation of the envelope protein gene identifies two distinct genotypes of yellow fever virus. J. Virol 69, 5773–5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DH (1960). Antigenic analysis of certain group B arthropodborne viruses by antibody absorption. J. Exp. Med 111, 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffis S, Kontermann RE, Korimbocus J, Zeller H, Klenk H-D, and Ter Meulen J.(2005). Antibody responses against wild-type yellow fever virus and the 17D vaccine strain: characterization with human monoclonal antibody fragments and neutralization escape variants. Virology 337, 262–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejnirattisai W, Wongwiwat W, Supasa S, Zhang X, Dai X, Rouvinski A, Jumnainsong A, Edwards C, Quyen NTH, Duangchinda T, et al. (2015). A new class of highly potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies isolated from viremic patients infected with dengue virus. Nat. Immunol 16, 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, et al. (2008). Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W465–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douam F, and Ploss A.(2018). Yellow fever virus: knowledge gaps impeding the fight against an old foe. Trends Microbiol. 26, 913–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd KA, Jost CA, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, and Pierson TC (2011). A dynamic landscape for antibody binding modulates antibody-mediated neutralization of West Nile virus. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd KA., DeMaso CR., and Pierson TC. (2015). Genotypic differences in dengue virus neutralization are explained by a single amino acid mutation that modulates virus breathing. MBio 6, e01559–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussupt V, Modjarrad K, and Krebs SJ (2020). Landscape of monoclonal antibodies targeting zika and dengue: therapeutic solutions and critical insights for vaccine development. Front. Immunol 11, 621043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estofolete CF, and Nogueira ML (2018). Is a dose of 17D vaccine in the current context of Yellow Fever enough? Braz. J. Microbiol 49, 683–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallichotte EN, Baric TJ, Nivarthi U, Delacruz MJ, Graham R, Widman DG, Yount BL, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, de Silva AM, et al. (2018). Genetic Variation between Dengue Virus Type 4 Strains Impacts Human Antibody Binding and Neutralization. Cell Rep. 25, 1214–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanetti M, de Mendonça MCL, Fonseca V, Mares-Guia MA, Fabri A, Xavier J, de Jesus JG, Gräf T, Dos Santos Rodrigues CD, Dos Santos CC, et al. (2019). Yellow Fever Virus Reemergence and Spread in Southeast Brazil, 2016–2019. J. Virol 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez MM, de Abreu FVS, Santos AACD, de Mello IS, Santos MP, Ribeiro IP, Ferreira-de-Brito A, de Miranda RM, de Castro MG, Ribeiro MS, et al. (2018). Genomic and structural features of the yellow fever virus from the 2016–2017 Brazilian outbreak. J. Gen. Virol 99, 536–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo L, Dowd KA, Smith ARY, Pelc RS, DeMaso CR, and Pierson TC (2016). Zika virus is not uniquely stable at physiological temperatures compared to other flaviviruses. MBio 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo L, VanBlargan LA, Dowd KA, Diamond MS, and Pierson TC (2017). A single mutation in the envelope protein modulates flavivirus antigenicity, stability, and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo L., DeMaso CR., Pelc RS., Ledgerwood JE., Graham BS., Kuhn RJ., and Pierson TC. (2018). The Zika virus envelope protein glycan loop regulates virion antigenicity. Virology 515, 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Delsuc F, Dufayard J-F, and Gascuel O.(2009). Estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies with PhyML. Methods Mol. Biol 537, 113–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, and Brunak S.(2002). Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. Pac. Symp. Biocomput 310–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SC, de Souza R, Thézé J, Claro I, Aguiar RS, Abade L, Santos FCP, Cunha MS, Nogueira JS, Salles FCS, et al. (2020). Genomic Surveillance of Yellow Fever Virus Epizootic in São Paulo, Brazil, 2016 – 2018. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen MC, Peters B, Nielsen M, and Marcatili P.(2017). BepiPred-2.0: improving sequence-based B-cell epitope prediction using conformational epitopes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W24–W29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, and Henrick K.(2007). Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, and Bork P.(2016). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W242–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey NP, Horiuchi KA, Fulton C, Panella AJ, Kosoy OI, Velez JO, Krow-Lucal ER, Fischer M, and Staples JE (2018). Persistence of yellow fever virus-specific neutralizing antibodies after vaccination among US travellers. J. Travel Med 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, and Godzik A.(2006). Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Xiao H, Li S, Pang X, Song J, Liu S, Cheng H, Li Y, Wang X, Huang C, et al. (2019). Double lock of a human neutralizing and protective monoclonal antibody targeting the yellow fever virus envelope. Cell Rep. 26, 438–446.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani DM, Rogers TF, Beutler N, Ricciardi MJ, Bailey VK, Gonzalez-Nieto L, Briney B, Sok D, Le K, Strubel A, et al. (2017). Neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies prevent Zika virus infection in macaques. Sci. Transl. Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez DR., Yount B., Nivarthi U., Munt JE., Delacruz MJ., Whitehead SS., Durbin AP., de Silva AM., and Baric RS. (2020). Antigenic variation of the dengue virus 2 genotypes impacts the neutralization activity of human antibodies in vaccinees. Cell Rep. 33, 108226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RA, Tauraso NM, Spertzel RO, and Ginn RK (1973). Yellow fever vaccine: direct challenge of monkeys given graded doses of 17D vaccine. Appl. Microbiol 25, 539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattia K, Puffer BA, Williams KL, Gonzalez R, Murray M, Sluzas E, Pagano D, Ajith S, Bower M, Berdougo E, et al. (2011). Dengue reporter virus particles for measuring neutralizing antibodies against each of the four dengue serotypes. PLoS ONE 6, e27252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer WB, Yount B, Hacker KE, Donaldson EF, Huynh JP, de Silva AM, and Baric RS (2012). Development and characterization of a reverse genetic system for studying dengue virus serotype 3 strain variation and neutralization. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 6, e1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, and Harrison SC (2003). A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 6986–6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, and Harrison SC (2005). Variable surface epitopes in the crystal structure of dengue virus type 3 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol 79, 1223–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monath TP (2012). Review of the risks and benefits of yellow fever vaccination including some new analyses. Expert Rev. Vaccines 11, 427–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]