Abstract

Although kidney transplantation provides a significant benefit over dialysis, many patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are conflicted about their decision to undergo kidney transplant. We aimed to identify the prevalence and characteristics associated with decisional conflict between treatment options in ESRD patients presenting for transplant evaluation. Among a cross-sectional sample of patients with ESRD (n=464) surveyed in 2014 and 2015, we assessed decisional conflict through a validated 10-item questionnaire. Decisional conflict was dichotomized into no decisional conflict (score=0) and any decisional conflict (score>0). We investigated potential characteristics of patients with decisional conflict using bivariate and multivariable logistic regression. The overall mean age was 50.6 years, with 62% male patients and 48% African American patients. Nearly half (48.5%) of patients had decisional conflict regarding treatment options. Characteristics significantly associated with decisional conflict in multivariable analysis included male sex, lower educational attainment, and less transplant knowledge. Understanding characteristics associated with decisional conflict in patients with ESRD could help identify patients who may benefit from targeted interventions to help patients make informed, value-based, and supported decisions when deciding how to best treat their kidney disease.

Keywords: conflict, dialysis, patients, transplant, treatment, uncertainty

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Compared to long-term dialysis, kidney transplantation is the preferred method of treatment for most patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), offering a better quality of life, decreased likelihood of hospitalization, lower treatment cost, and increased survival.1,2 Despite the known benefits of kidney transplantation vs dialysis, patients with ESRD who are minorities, elderly, women, or are of lower socioeconomic status have diminished access to kidney transplantation.3–5 Several socioeconomic elements, including neighborhood poverty, employment status, insurance status, and educational attainment, are known to impact whether an ESRD patient moves forward with each successive step in the multifaceted kidney transplant process.6–9

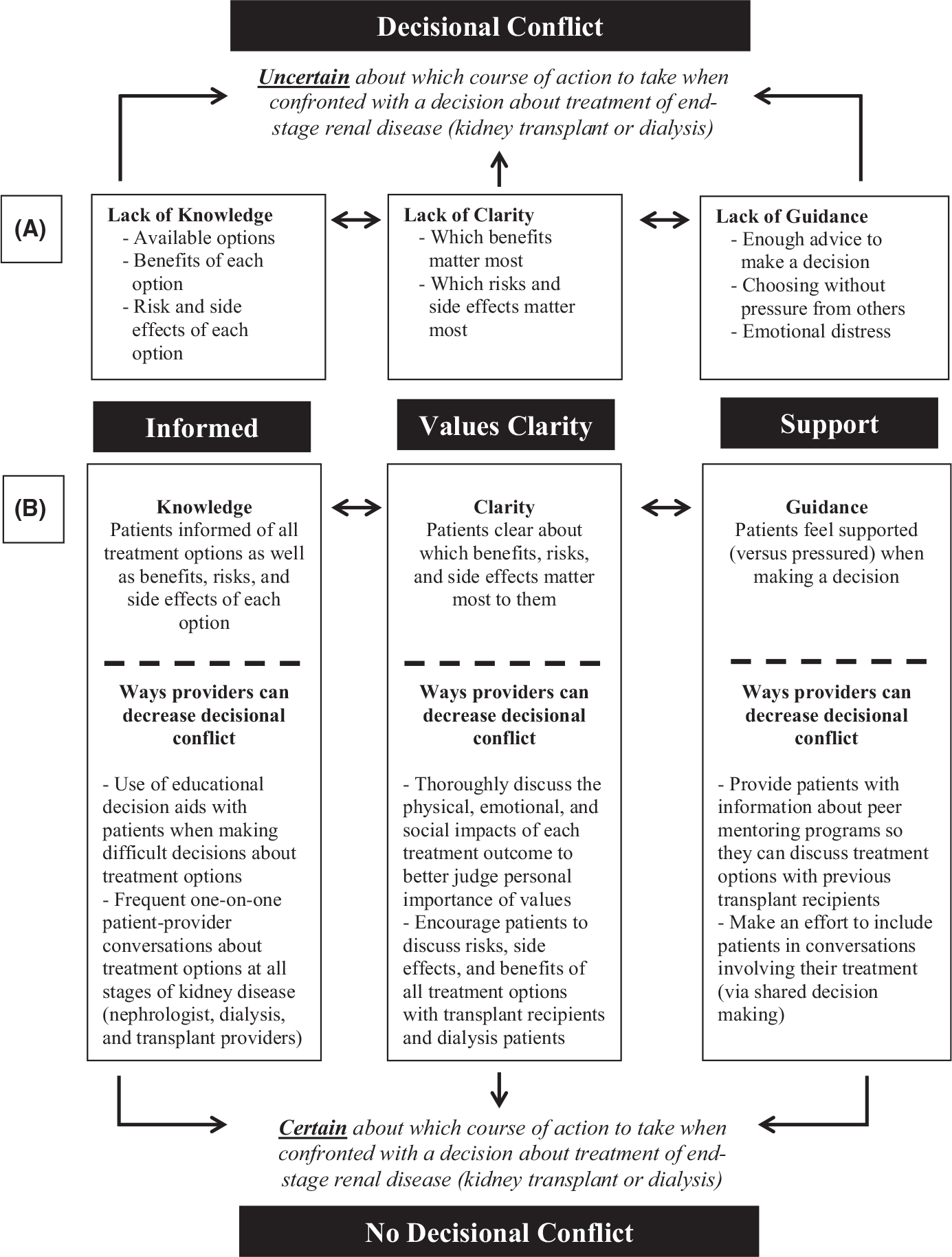

Although interventions have been developed to educate patients with ESRD about the benefits and survival advantage of kidney transplant, some patients may still feel conflicted about their decision to pursue kidney transplant over dialysis.3,10–15 Decisional conflict is defined as “a state of uncertainty about which course of action to take” and it can be assessed through various measurement tools such as O’Connor’s validated decisional conflict scale and subscales,16 previously used to assess treatment option decisional conflict among breast cancer, prostate cancer, and anticoagulated patient populations.17–20 According to O’Connor, distinct factors can be modified to either intensify (Figure 1A) or alleviate (Figure 1B) decisional conflict, all of which can be applied in the setting of ESRD treatment option uncertainty.16,21 Patients with ESRD may be more conflicted when they feel uninformed about treatment risks and benefits. Previous literature found a substantial number of kidney disease patients’ access to information about ESRD treatment modalities to be minimal, which could exacerbate patients’ level of decisional conflict. More specifically, a multicenter cross-sectional study found that approximately 30% of study patients had a low perceived knowledge of treatment options,22 and a cohort study reported that only two-thirds of patients indicated they had been informed of transplant as a treatment modality at the time of dialysis initiation.11

FIGURE 1.

(A) Conceptual model of decisional conflict as it relates to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients’ decision-making about kidney transplantation vs dialysis. (B) Conceptual model outlining potential pathways to decrease the likelihood of ESRD patients having decisional conflict when confronted with a decision about their treatment options (Figure adapted and modified from Mahant et al.30)

Other primary factors contributing to increased decisional conflict include a lack of clarity about personal values (what benefits, risks, and side effects matter most) and support/guidance when making a decision between treatment options.16,21 Given the behavioral manifestations that may develop secondary to decisional conflict, such as prolonged decision-making, indecisiveness about personal values, and physical anguish, decisional conflict may be an important measure to capture in the ESRD patient population to reduce patient uncertainty and decrease time from referral to evaluation, waitlisting, and subsequently transplantation. To our knowledge, the prevalence of decisional conflict is unknown among the ESRD population; a validated decisional conflict scale is yet to be used to evaluate ESRD patient decisional conflict regarding dialysis vs kidney transplantation and to compare the demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics of patients with and without decisional conflict.17,21

The overall purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of decisional conflict in patients with ESRD being evaluated at a transplant center and identify patient characteristics associated with decisional conflict between treatment options. By evaluating ESRD patients’ level of decisional conflict, there is potential to identify patients who may need additional assistance in making a decision about their treatment options. Moreover, identifying ESRD patient characteristics associated with decisional conflict could help target future intervention efforts on modifiable factors to reduce patient uncertainty and ensure patients make an informed, value-based, and supported decision about treatment of their kidney disease.

2 |. METHODS

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of a baseline survey and clinical data collected on patients with ESRD as part of, the iChoose Kidney Decision Aid for Treatment Options (iChoose Kidney) randomized controlled trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02235571). Further details of the ongoing clinical trial can be found elsewhere.23 The Emory Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB1485996), and written informed consent was obtained for all study participants.

2.1 |. Study protocol and population

Patients were recruited from three large transplant centers in the United States, including the Emory Transplant Center in Atlanta, GA, the Renal and Pancreatic Transplant Program at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) in New York, NY, and the Kovler Organ Transplantation Center in Chicago, IL from November 1, 2014 through October 31, 2015. A total of 470 patients with ESRD were recruited into the study by a coordinator at the three study sites during the patient’s kidney transplant evaluation. To meet study inclusion criteria, patients must have been between the age of 18 and 70 years, English-speaking, with no severe cognitive or visual impairments. Patients with a history of a solid organ or multi-organ transplant were not eligible for the study. Consent was obtained from patients. Patients were asked to complete a baseline survey prior to being evaluated and educated by a transplant nephrologist or surgeon, which included a 10-item questionnaire assessing decisional conflict.21 The survey was designed with a HIPAA compliant web-based tool, SurveyMonkey, and administered via an iPad or paper, depending on the patient’s preference. At the time of baseline survey administration, intervention patients had not yet received the iChoose Kidney intervention13; our analysis focuses only on baseline data.

Using selected demographic and socioeconomic questions and the baseline decisional conflict questionnaire, a cross-sectional analysis was performed. Of the 470 patients initially recruited, participants were excluded from analyses if more than one of the 10 decisional conflict questions were missing a response (n=6). A total of 464 participants were deemed eligible for analyses.

2.2 |. Outcome variable

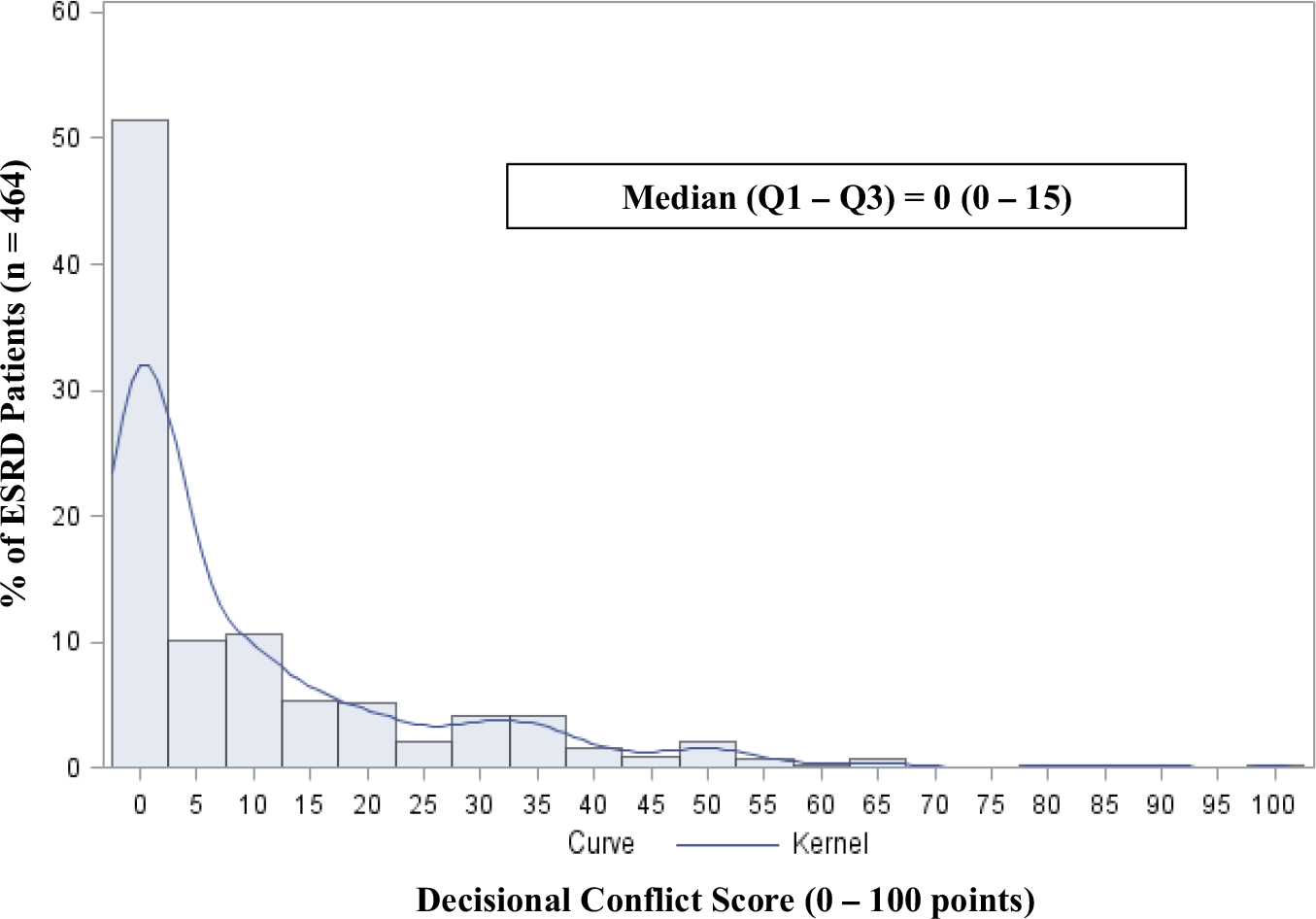

The primary outcome variable for this cross-sectional study was decisional conflict regarding kidney disease treatment options (dialysis vs kidney transplant). The data were collected in a 10-item, 3-response category format adapted from version 4.3 of O’Connor’s validated decisional conflict scale for individuals with “limited reading or response skills”.21 To calculate and interpret a patient’s total decisional conflict score, we followed the instructions outlined in O’Connor’s decisional conflict user manual. Items were given a score value of 0, 2, or 4 for responses “Yes,” “Unsure,” or “No,” respectively. The 10 items were then summed, divided by 10, and multiplied by 25 to determine a patient’s total decisional conflict score on a 100-point scale.21 Total decisional conflict scores could range from 0 (no decisional conflict) to 100 (extremely high decisional conflict), with higher scores representing a greater likelihood of “uncertainty about a course of action” with respect to deciding between transplant and dialysis.21 A total of n=11 patients were only missing one item from the scale; the total decisional conflict score for patients with missing data was calculated by summing the 9 nonmissing items, dividing by 9, and multiplying by 25. Approximately half (52%) of our study population had no decisional conflict with a score of 0; therefore, for analyses, decisional conflict was dichotomized as no decisional conflict (score of 0) or any decisional conflict (score>0; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of decisional conflict score in patients with end-stage renal disease presenting for transplant evaluation at three US transplant centers, 2014–2015 (n=464)

We conducted a more specific analysis using the four decisional conflict subscores (informed, values clarity, support, and uncertainty) to examine which decisional conflict factors were most prominent among our patient population. Results of this subanalysis may better guide intervention development to target modifiable cognitive and/or societal factors contributing to decisional conflict among patients with ESRD (Figures 1A,B). Each of the subscores was calculated and interpreted similarly to the total decisional conflict score by using a subset of the 10 items that focus on a particular factor influencing patients’ level of decisional conflict.21

2.3 |. Potential factors associated with decisional conflict

Selected patient characteristics were abstracted from patients’ medical records at the time of kidney transplant evaluation. Demographic characteristics included age (in years) and sex. Patient race/ethnicity was self-reported at baseline. In the event of a missing self-reported race variable, the patient’s race/ethnicity listed in their patient chart was used. Clinical characteristics including body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, albumin level, ESRD status, and dialysis type (not on dialysis, hemodialysis, or peritoneal dialysis) were also abstracted directly from the chart at time of transplant evaluation.

Socioeconomic variables including marital status (married vs nonmarried), educational attainment (professional/graduate degree, some college/college degree, some high school/high school degree, or 8th grade or less), employment status (unemployed, employed, or retired), primary health insurance status (private, nonprivate, or none), and household income were obtained. Additional variables included social support (at least one family member or friend accompanying the patient at their transplant evaluation), health literacy (calculated using Newest Vital Sign on a scale from 0 to 6), numeracy (calculated using the Lipkus scale on a scale from 0 to 11), transplant knowledge (measured using eight survey questions about survival benefits of transplantation in the baseline survey), and a multiple choice question assessing treatment preference. (Which treatment option [dialysis, kidney transplantation, unsure] do you prefer? Please check one).23–25 Transplant knowledge and treatment preference were collected prior to when patients saw a transplant nephrologist or surgeon during their evaluation. Health literacy and numeracy were collected after the patient had spoken with the transplant nephrologist or surgeon during their evaluation and used to assess patients’ general literacy applied to health information and ability to understand numeric information, respectively. Finally, transplant center location was used to represent participants’ geographic location. However, institutions were identified as Transplant Center A, B, and C to ensure transplant center confidentiality.

2.4 |. Data analyses

Demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics of patients with and without decisional conflict were compared using chi-square tests of independence for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. For all analyses, results were considered to be statistically significant at α <.05. All variables collected and abstracted from medical records with potential to be associated with decisional conflict were considered to be candidate variables. Variables were screened using bivariate and correlation analyses. To examine the degree of linear correlation between similar, continuous characteristics, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients. If two continuous variables were found to be moderately correlated with one another (r>.3 or r<−.3), only one was selected for the final multivariable model, using the effect estimate strength in bivariate analyses as a guide. The full model was built using nonautomated backward elimination, starting with all candidate variables in the model and testing the removal of each variable. Multiple imputation was used in cases of missing covariate data. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed to compare the characteristics of patients with (n=6) and without missing decisional conflict data to ensure that data were missing at random. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient characteristics

Of the 464 patients included in the analyses, the average age was 50.6 years (SD: 10.2) with 62.1% male, 47.6% African American, and 10.6% white, Hispanic (Table 1). At the time of transplant evaluation, 78.7% of all patients had been previously diagnosed with hypertension, while 37.9% had a diabetes diagnosis, and 18.3% had a BMI >35 kg/m2. The median time on dialysis prior to transplant evaluation was 361 days (IQR: 170.0–1174.5), with 32.8% of patients not on dialysis prior to transplant evaluation. Approximately 38.8% of patients were employed, and 23.9% had earned a high school diploma or GED. The mean health literacy score and numeracy score for all patients were 3.6 of 6 (SD: 2.1) and 6.1 of 11 (SD: 3.2), respectively (Table 1). In sensitivity analyses examining characteristics of patients excluded for missing decisional conflict data (n=6), characteristics were similar to patients without missing data (n=464). Among the 657 patients approached to participate in the study, only 81 (12.3%) declined to participate, which was primarily due to time limitations or a nonspecific lack of interest.

TABLE 1.

Selected characteristics of patients with ESRD by decisional conflicta score at three large transplant centers (n=464), 2014–2015

| Study population N (%) | No decisional conflict (score=0) | Any decisional conflict (score>0) | Significance testingc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristicb | N=464 | N=239 (51.5) | N=225 (48.5) | Test statistic | P-valued |

| Demographic characteristics at time of transplant evaluation | |||||

| Age, mean±SD, y | 50.6±10.2 | 50.2±10.5 | 51.1±9.8 | −0.92 | .36 |

| Male, n (%) | 288 (62.1) | 134 (56.1) | 154 (68.4) | 7.54 | .01 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 13.46 | <.01 | |||

| African American | 221 (47.6) | 100 (41.8) | 121 (53.8) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 162 (34.9) | 101 (42.3) | 61 (27.1) | ||

| White, Hispanic | 49 (10.6) | 20 (8.4) | 29 (12.9) | ||

| Othere | 31 (6.7) | 17 (7.1) | 14 (6.2) | ||

| Institution, n (%) | 2.83 | .24 | |||

| Transplant Center A | 158 (34.1) | 73 (30.6) | 85 (37.8) | ||

| Transplant Center B | 143 (30.8) | 76 (31.8) | 67 (29.8) | ||

| Transplant Center C | 163 (35.1) | 90 (37.7) | 73 (32.4) | ||

| Clinical characteristics at time of transplant evaluation | |||||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Body mass index >35 kg/m2 | 85 (18.3) | 40 (16.7) | 45 (20.0) | 0.83 | .45 |

| Hypertension | 365 (78.7) | 187 (78.2) | 178 (79.1) | 0.05 | .82 |

| Diabetes | 176 (37.9) | 83 (34.7) | 93 (41.3) | 2.15 | .14 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 43 (9.3) | 20 (8.4) | 23 (10.2) | 0.47 | .49 |

| Albumin <3.5 g/dL | 81 (17.4) | 36 (15.1) | 45 (20.0) | 2.34 | .13 |

| Type of dialysis, n (%) | 1.32 | .52 | |||

| Not on dialysis | 152 (32.8) | 83 (34.7) | 69 (30.7) | ||

| Hemodialysis | 239 (51.5) | 122 (51.1) | 117 (52.0) | ||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 73 (15.7) | 34 (14.2) | 39 (17.3) | ||

| Time on dialysis prior to evaluation, n (%) | 5.03 | .08 | |||

| Not on dialysis | 152 (32.8) | 83 (34.7) | 69 (30.7) | ||

| <1 y on dialysis | 156 (33.6) | 87 (36.4) | 69 (30.7) | ||

| ≥1 y on dialysis | 156 (33.6) | 69 (28.9) | 87 (38.7) | ||

| Self-reported socioeconomic characteristics at time of transplant evaluation | |||||

| Married, n (%) | 273 (58.8) | 153 (64.0) | 120 (53.3) | 5.78 | .02 |

| Social supportf, n (%) | 250 (53.9) | 132 (55.2) | 118 (52.4) | 1.19 | .27 |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | 22.16 | <.01 | |||

| 8th grade or less | 11 (2.4) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (3.1) | ||

| Some high school | 26 (5.6) | 9 (3.8) | 17 (7.6) | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 111 (23.9) | 41 (17.2) | 70 (31.1) | ||

| Some college or vocational school degree | 130 (28.0) | 71 (29.7) | 59 (26.2) | ||

| College or vocational school degree | 109 (23.5) | 60 (25.1) | 49 (21.8) | ||

| Professional or graduate degree | 71 (15.3) | 49 (20.5) | 22 (9.8) | ||

| Employment status, n (%) | 6.65 | .04 | |||

| Employed | 180 (38.8) | 106 (44.4) | 74 (32.9) | ||

| Unemployed | 171 (36.9) | 80 (33.5) | 91 (40.4) | ||

| Retired | 104 (22.4) | 48 (20.1) | 56 (24.9) | ||

| Primary health insurance status, n (%) | 7.57 | .01 | |||

| Private | 264 (56.9) | 150 (62.8) | 114 (50.7) | ||

| Government | 194 (41.8) | 85 (35.6) | 109 (48.4) | ||

| Health literacy scoreg, mean±SD | 3.6±2.1 | 4.0±1.9 | 3.2±2.1 | 4.37 | <.01 |

| Numeracy scoreh, mean±SD | 6.1±3.2 | 6.6±3.2 | 5.6±3.2 | 3.32 | <.01 |

| Transplant knowledgei, mean±SD | 5.0±2.1 | 5.5±2.0 | 4.5±2.2 | 5.23 | <.01 |

| ESRD treatment preference, n (%) | 18.8 | <.01 | |||

| Kidney transplant | 346 (74.6) | 190 (79.5) | 156 (69.3) | ||

| Dialysis | 98 (21.1) | 48 (20.1) | 50 (22.2) | ||

| Don’t know | 16 (3.5) | 0 | 16 (7.1) | ||

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; IQR, interquartile range.

O’Connor.16

Percentages may not all add up to 100% due to missing data. Covariates with missing data: race (n=1); albumin <3.5 g/dL (n=17); marital status (n=5); social support (n=41); educational attainment (n=6); employment status (n=8); primary health insurance status (n=6); household income before taxes (n=8); literacy (n=22); numeracy (n=22); ESRD treatment preference (n=4).

By chi-square (categorical variables) or t-value (continuous variables).

Bolded values indicate statistically significant differences at alpha <0.05

Includes Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, East Indian, and multiracial.

Defined as at least one family member or friend accompanying the patient at transplant evaluation.

Literacy score calculated using Newest Vital Sign, NVS, on a scale from 0 to 6.

Numeracy score calculated using the Lipkus scale, on a scale from 0 to 11.

Transplant Knowledge calculated using a 8-item questionnaire administered to patients prior to seeing a transplant nephrologist/surgeon at their transplant evaluation, on a scale from 0 to 9.

At the time of transplant evaluation, nearly half (48.5%) of patients had some level of decisional conflict (Median: 0, Q1-Q3: 0–15) with a score>0 (Table 1, Figure 2). Among patients with any decisional conflict, results of the subscore analyses suggested that feeling uninformed about options (Median: 16.7, Q1-Q3: 0–50) and unclear about personal values (Median: 25, Q1-Q3: 0–50) more heavily contributed to a patient’s total decisional conflict score than feeling unsupported (Median: 0, Q1-Q3: 0–6.7) and uncertain (Median: 0, Q1-Q3: 0–50) when making a treatment decision. Among patients with decisional conflict (n=225), approximately 68% were male and 54% were African American. Comorbidities, including hypertension (79.1% vs 78.2%; P=.82), diabetes (41.3% vs 34.7%; P=.14), cardiovascular disease (10.2% vs 8.4%; P=.49), high BMI (20.0% vs 16.7%; P=.45), and low serum albumin (20.0% vs 15.1%; P=.13), were more prevalent in patients with decisional conflict vs patients with no decisional conflict. Patients without decisional conflict (n=239) were more likely to be married (64.0% vs 53.3%; P=.02), have a college or professional degree (20.5% vs 9.8%; P<.01), employed (44.4% vs 32.9%; P=.04), and privately insured (62.8% vs 50.7%; P=.01). On average, patients without decisional conflict performed better by one point (of nine possible points) on the transplant knowledge portion of the survey than those with decisional conflict (P<.01; Table 1). The median number of days on dialysis prior to transplant evaluation among nonconflicted patients was 293 days (IQR: 168–1027), approximately 48 days less than patients with decisional conflict (Table 1).

3.2 |. Characteristics associated with decisional conflict

Bivariate associations between demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic factors and decisional conflict are presented in Table 2. Unadjusted covariates, including traditional sociodemographic factors such as sex (male vs female OR: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.16, 2.49), race (African American vs white, non-Hispanic OR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.33, 3.03), ethnicity (white, Hispanic vs white, non-Hispanic OR: 2.40; 95% CI: 1.25, 4.61), marital status (single vs married OR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.09, 2.30), and education (high school vs graduate education OR: 3.87; 95% CI: 2.10, 7.14) were all significant predictors of decisional conflict. Patients with nonprivate health insurance as opposed to private health insurance also had an increased probability (OR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.16, 2.45) of expressing uncertainty regarding kidney treatment options. Lower health literacy (OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.74, 0.90) and lower numeracy (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.85, 0.96) scores had a statistically significant effect on decisional conflict for patients with ESRD (Table 2). Additionally, for every one-point increase in a patient’s transplant knowledge score, there was a 21% decrease in the odds of having decisional conflict (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.72, 0.87; Table 2). In regard to patient clinical characteristics, the odds of having decisional conflict in patients on dialysis ≥1 year are higher compared to patients on dialysis <1 year prior to transplant evaluation (OR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.49; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics associated with decisional conflicta in patients with ESRD presenting for kidney transplant evaluation from bivariate and multivariable logistic regression at three large transplant centers, 2014–2015

| Unadjusted model |

Adjusted modelb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristicc | OR (95% CI) | P-valued | aOR (95% CI) | P-valued |

| Age, y | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | .36 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | .19 |

| Sex | .006 | .01 | ||

| Female (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 1.70 (1.16, 2.49) | 1.74 (1.15, 2.63) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .004 | .31 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| White, Hispanic | 2.40 (1.25, 4.61) | 1.76 (0.87, 3.59) | ||

| African American | 2.00 (1.33, 3.03) | 1.51 (0.91, 2.48) | ||

| Othere | 1.36 (0.63, 2.96) | 1.42 (0.61, 3.33) | ||

| Institution | .24 | |||

| Transplant Center A (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Transplant Center B | 0.78 (0.48, 1.19) | |||

| Transplant Center C | 0.70 (0.45, 1.08) | |||

| Body mass index >35 kg/m2 | .36 | |||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.24 (0.78, 1.99) | |||

| Hypertension diagnosis | .82 | |||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.05 (0.68, 1.64) | |||

| Diabetes diagnosis | .14 | |||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.32 (0.91, 1.93) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease diagnosis | .49 | |||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.25 (0.67, 2.34) | |||

| Albumin <3.5 g/dL | .13 | |||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.46 (0.90, 2.36) | |||

| Type of dialysis | .52 | |||

| Not on dialysis (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Hemodialysis | 1.15 (0.77, 1.73) | |||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 1.38 (0.79, 2.42) | |||

| Time on dialysis prior to evaluation | .08 | .19 | ||

| <1 y (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not on dialysis | 1.05 (0.67, 1.64) | 1.54 (0.94, 2.54) | ||

| ≥1 y | 1.60 (1.02, 2.49) | 1.39 (0.85, 2.26) | ||

| Marital status | .02 | .26 | ||

| Married (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not married | 1.58 (1.09, 2.30) | 1.28 (0.84, 1.97) | ||

| Social supportf | .28 | .40 | ||

| Yes (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| No | 1.24 (0.84, 1.83) | 1.20 (0.79, 1.85) | ||

| Educational attainment | <.001 | .02 | ||

| Professional or graduate degree (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Some college or college degree | 1.84 (1.05, 3.23) | 1.61 (0.88, 2.95) | ||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 3.87 (2.10, 7.14) | 2.57 (1.28, 5.14) | ||

| Employment status | .03 | |||

| Employed (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Unemployed | 1.63 (1.07, 2.49) | |||

| Retired | 1.67 (1.03, 2.72) | |||

| Primary health insurance status | .006 | |||

| Private (referent) | 1.00 | |||

| Government Only | 1.69 (1.16, 2.45) | |||

| Health literacy scoreg | 0.81 (0.74, 0.90) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.84, 1.06) | .35 |

| Numeracy scoreh, i | 0.91 (0.85, 0.96) | .001 | ||

| Transplant knowledgej | 0.79 (0.72, 0.87) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.95) | .002 |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

O’Connor.16

Adjusted for age, sex, race, time on dialysis prior to transplant evaluation, marital status, social support, educational attainment, transplant knowledge, and health literacy.

All characteristics were collected at the time of patients’ transplant evaluation.

Statistically significant at P<.05.

Includes Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, East Indian, and multiracial.

Defined as at least one family member or friend accompanying the patient at transplant evaluation.

Literacy score calculated using Newest Vital Sign, NVS, on a scale from 0 to 6.

Numeracy score calculated using the Lipkus scale, on a scale from 0 to 11.

Numeracy and health literacy were linearly correlated (Pearson correlation: r=.6); Health literacy was selected for the final, adjusted model secondary to the association of health literacy with health outcomes among kidney disease patients examined in previous literature.

Transplant Knowledge calculated using a 8-item questionnaire administered to patients prior to seeing a transplant nephrologist/surgeon at their transplant evaluation, on a scale from 0 to 9.

The final multivariable model adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, time on dialysis, marital status, social support, educational attainment, transplant knowledge, and health literacy (Table 2). Male sex (vs female OR: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.15, 2.63), high school education (vs graduate OR: 2.57; 95% CI: 1.28, 5.14), and lower transplant knowledge (OR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.77, 0.95) were significantly associated (P<.05) with higher odds of having decisional conflict in this ESRD patient population (Table 2). Numeracy and health literacy were linearly correlated (Pearson correlation r=.6), so we selected health literacy for the final model due to the association of health literacy with health outcomes among kidney disease patients examined in the previous literature.26,27

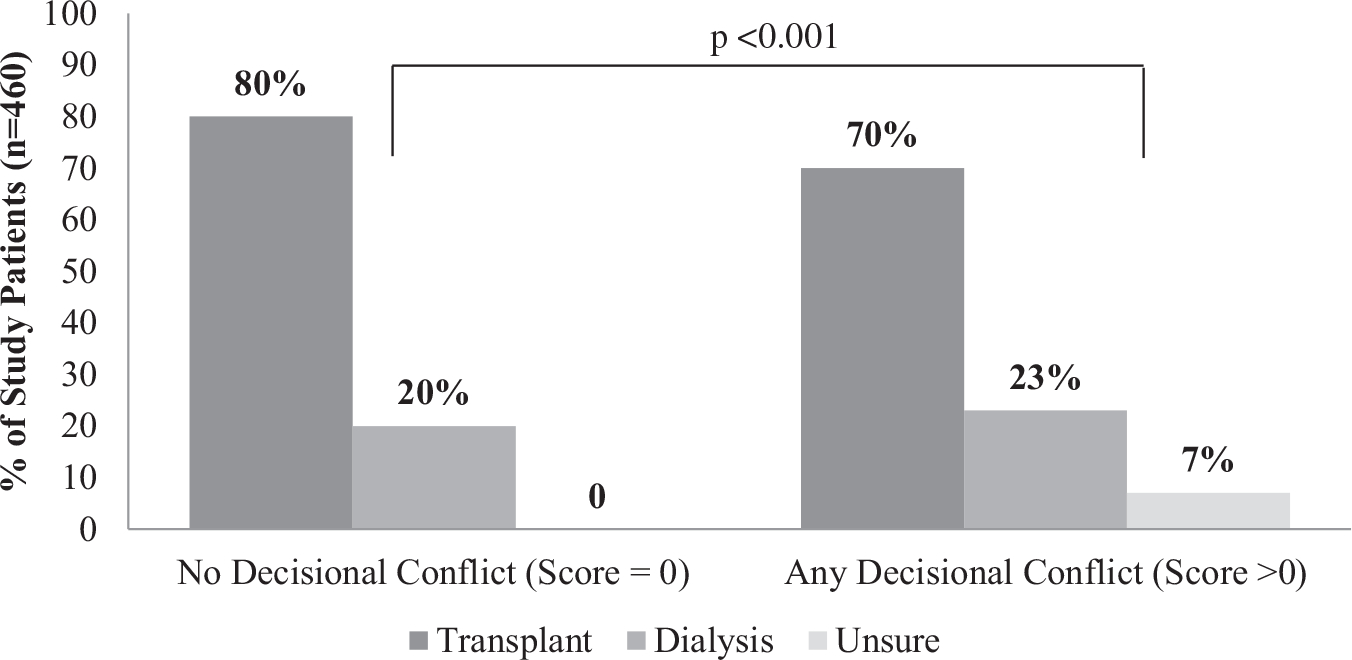

3.3 |. Treatment preference by decisional conflict score

Regardless of decisional conflict score, when asked which treatment method they preferred, a majority of participants selected kidney transplant vs dialysis (Table 1, Figure 3). Among patients with any decisional conflict, 70% preferred kidney transplant, while 80% of patients without decisional conflict favored kidney transplant over dialysis treatment (P<.001; Table 1, Figure 3). A total of 16 patients with decisional conflict (vs 0 patients without decisional conflict) did not appear to have a partiality for either treatment method by indicating they were unsure when asked which treatment method they most preferred.

FIGURE 3.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) treatment preferences (transplant, dialysis, and unsure) among ESRD patients with and without decisional conflict (n=460; four patients excluded due to missing data) at three US transplant centers in 2014–2015

4 |. DISCUSSION

We found that approximately half of patients with ESRD presenting for kidney transplant evaluation with a transplant nephrologist or surgeon at Emory, Columbia, and Northwestern transplant centers between November 2014 and October 2015 had some decisional conflict regarding ESRD treatment options. The majority of patients selected kidney transplant vs dialysis as their preferred ESRD treatment option, suggesting that even patients who prefer and pursue the optimal ESRD treatment method1,2 are not entirely confident in their decision. However, patients without decisional conflict more often selected kidney transplant as their preferred treatment compared to patients with decisional conflict. As patients with decisional conflict more frequently waver between treatment options and delay decision-making,21,28 it may not be uncommon for patients’ decisional conflict to manifest at the time of ESRD diagnosis and remain unresolved at their transplant evaluation. After controlling for several demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic patient characteristics in multivariable analysis, male sex, lower educational attainment, and less transplant knowledge continued to be associated with decisional conflict at the time of transplant evaluation. While being a male and having lower levels of formal education are considered to be less-modifiable characteristics, limited transplant knowledge is a patient characteristic that providers can intervene on and modify in clinical practice.29

The noticeable presence of decisional conflict at time of transplant evaluation, specifically among those who have a preference for kidney transplant compared to dialysis, supports the importance of capturing this validated measurement among patients with kidney disease at varying stages in their disease course. Becoming familiar with modifiable characteristics of patients with decisional conflict could help clinicians to risk stratify patients to receive additional interventions about their treatment options prior to transplant evaluation. Understanding the factors of decisional conflict most prominently contributing to patient uncertainty could also guide the development and use of more targeted interventions among patients in clinical practice. As discussed by O’Connor, several factors can improve (Figure 1A) or exacerbate (Figure 1B) patients’ level of decisional conflict, including how informed patients are about their treatment options, how clear patients are about what risks and benefits matter most to them, and how supported patients feel when making a difficult decision about treatment of their kidney disease.16,21,30 Our findings suggest that limited knowledge about kidney transplant and uncertainty about the physical, emotional, and social impact of kidney transplant vs dialysis are more prominently contributing to decisional conflict than a lack of social support among patients with ESRD.

The use of educational decision aids among patients with decisional conflict could help facilitate more in-depth provider-patient discussions about kidney transplant and dialysis, increase transplant knowledge, and ultimately decrease decisional conflict (Figure 1B). In Stacey et al.’s31 systematic review of decision aids for patients facing treatment decisions, results from 115 studies led researchers to conclude that the use of decision aids improves patients’ knowledge about their treatment options as well as lessens patients’ level of decisional conflict. O’Connor’s decisional conflict scale has been utilized within cancer literature, and results from three studies indicate an association between increased knowledge and reduced decisional conflict about treatment options with the use of decision aids.18,32,33 The iChoose Kidney mobile and web-based application13 part of the ongoing iChoose Kidney randomized controlled trial23 and the PREPARED video testimonials and comprehensive handbook34 are examples of ESRD treatment option decision aids designed to be used in a clinical and home setting, respectively.

Additionally, providing transplant education to patients at numerous time points throughout the transplant process, specifically at the time of or before dialysis initiation, would give patients more opportunities to formulate questions and surround themselves with a supportive group of family and friends as they consider their treatment options. Previous literature found a longer waiting time on dialysis to be one of the most significant risk factors for poor transplant outcomes.35 While a significant association between time on dialysis and decisional conflict disappeared in multivariable analysis, the direction of effect suggests that complacency with dialysis treatment and increased discomfort with asking someone for a kidney may be consequences of delayed decision-making secondary to a longer time on dialysis.36

In addition to limited knowledge, ESRD patients with decisional conflict may also struggle with determining which aspects of a treatment option they value most. Dialysis and transplant providers could familiarize themselves with what patients value most, such as financial concerns or survival advantage, in terms of treating their kidney disease to better guide their conversations about treatment options37 (Figure 1B). Patients seeking clarity about their personal values may also benefit from speaking with current/previous dialysis patients and previous transplant recipients about their experiences as dialysis patients have indicated in previous studies that they receive social support from their dialysis facility communities.38 Dialysis facility and transplant center staff could encourage patients with decisional conflict to speak with post-transplant recipients about their experiences. By sharing their personal journeys to transplant, transplant recipients could relate to pretransplant patients on a personal-level and provide support to patients with questions about the kidney transplant process and what to expect after undergoing a transplant.

Our results suggest there may be similarities between patients that have better recollection of education materials,11 take a more active role in their health care,39 and have minimal decisional conflict. Patients who take an active role in their health care may have better recall of educational information, and in turn, less decisional conflict about their treatment options. The incorporation of shared decision-making tools and strategies focused on the treatment options of ESRD may help patients may feel more empowered, supported, and confident when it comes time to make significant decisions about treatment options of their kidney disease (Figure 1B).

4.1 |. Study strengths and limitations

Our findings are part of a larger multisite randomized control trial, where patients presented for kidney transplant evaluation at three large transplant centers throughout the United States. The geographic diversity of our patient cohort is a major strength of this study in that it enhances the representativeness and diversity of our patient population. Second, the use of a cross-sectional design allowed for a more accurate and complete data collection in a short time period without the limitation of lost to follow-up. Furthermore, by collecting data at the time of transplant evaluation, we were able to use up-to-date demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics in our analysis.

This study does have its limitations, however. While we were able to collect data from patients with ESRD being evaluated at transplant centers throughout the country, we were unable to survey patients in previous stages of the transplant process. The demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics of patients with ESRD presenting for evaluation at a transplant center may differ from patients with ESRD presenting for routine appointments with their nephrologist or dialysis patients who have not initiated the transplant evaluation process. We must be cautious not to generalize our findings to all patients with ESRD, specifically to patients with ESRD who have not yet been referred for transplant evaluation, as patients with ESRD in our study population may be biased to kidney transplant as their preferred treatment option. We acknowledge that dichotomizing our primary outcome, decisional conflict, is a limitation of this study due to the distribution of the decisional conflict score among our patient population. As half of study patients had no decisional conflict, we were unable to keep this as a continuous variable and use linear regression for analyses. Despite our best efforts to abstract all demographic and clinical-related variables from patients’ medical records, some patient data were electronically unavailable. In those instances, we had to rely on self-reported baseline survey data, opening up the potential for recall bias. Due to time constraints during patient recruitment, we were unable to include a multi-item scale to more robustly examine patients’ level of social support, which we recognize as a limitation.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Decisional conflict between dialysis and kidney transplant appears to be prevalent among the ESRD population presenting for a kidney transplant evaluation, most commonly among male patients with lower levels of formal educational training and limited transplant knowledge. Understanding characteristics that contribute to decisional conflict among patients with ESRD, specifically more-modifiable characteristics could help providers identify patients who may require additional transplant educational resources or intervention efforts to increase transplant knowledge and create support networks. The decisional conflict scale could be utilized in future research to determine the prevalence of decisional conflict between treatment options in patients at varying stages of kidney disease and why a substantial proportion of patients with ESRD still feel uncertain about their treatment options at the time of their transplant evaluation. Further analyses can also be performed to more thoroughly evaluate the association of decisional conflict with access to transplantation, including dialysis vintage, evaluation completion, waitlisting, and transplantation. Future studies among patients already pursing kidney transplant should be carried out to assess decisional conflict regarding deceased vs living donor transplant as well as programs specific to transplant, such as paired exchange and receipt of higher risk organs.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Danovitch GM. Options for patients with kidney failure. In: Danovitch GM, ed. Handbook of Kidney Transplantation, 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2093–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal trans-plantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA. 1998;280:1148–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Churak JM. Racial and ethnic disparities in renal transplantation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg PP, Furth SL, Fivush BA, Powe NR. Impact of gender on access to the renal transplant waiting list for pediatric and adult patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Schrager JD, et al. The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the Southeastern United States. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:358–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keith D, Ashby VB, Port FK, Leichtman AB. Insurance type and minority status associated with large disparities in prelisting dialysis among candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashby VB, Kalbfleisch JD, Wolfe RA, Lin MJ, Port FK, Leichtman AB. Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996–2005. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(5 Pt 7):1412–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohan S, Mutell R, Patzer RE, Holt J, Cohen D, McClellan W. Kidney transplantation and the intensity of poverty in the contiguous United States. Transplantation. 2014;98:640–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Why hemodialysis patients fail to complete the transplantation process. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schold JD, Gregg JA, Harman JS, Hall AG, Patton PR, Meier-Kriesche HU. Barriers to evaluation and wait listing for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1760–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patzer RE, Basu M, Larsen CP, et al. iChoose kidney: a clinical decision aid for kidney transplantation versus dialysis treatment. Transplantation. 2016;100:630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patzer RE, Paul S, Plantinga L, et al. A randomized trial to reduce disparities in referral for transplant evaluation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;28:935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon EJ. Patients’ decisions for treatment of end-s tage renal disease and their implications for access to transplantation. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:971–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koedoot N, Molenaar S, Oosterveld P, et al. The decisional conflict scale: further validation in two samples of Dutch oncology patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan AL, Crespi CM, Saucedo JD, Connor SE, Litwin MS, Saigal CS. Decisional conflict in economically disadvantaged men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer: baseline results from a shared decision-making trial. Cancer. 2014;120:2721–2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong C, Kim S, Curnew G, Schulman S, Pullenayegum E, Holbrook A. Validation of a patient decision aid for choosing between dabigatran and warfarin for atrial fibrillation. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e229–e237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor AM. User Manual-Decisional Conflict Scale. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, et al. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1178–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patzer RE, Basu M, Mohan S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a mobile clinical decision aid to improve access to kidney transplantation: iChoose kidney. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;1:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipkus IM, Samsa G, Rimer BK. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazley AS, Hund JJ, Simpson KN, Chavin K, Baliga P. Health literacy and kidney transplant outcomes. Prog Transplant. 2015;25:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain D, Green JA. Health literacy in kidney disease: review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. World J Nephrol. 2016;5:147–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray MA, Brunier G, Chung JO, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing decision-making in adults living with chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:995–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahant S, Jovcevska V, Cohen E. Decision-making around gastrostomy-feeding in children with neurologic disabilities. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1471–e1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):Cd001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam WW, Chan M, Or A, Kwong A, Suen D, Fielding R. Reducing treatment decision conflict difficulties in breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2879–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau YK, Caverly TJ, Cao P, et al. Evaluation of a personalized, web-based decision aid for lung cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:e125–e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ameling JM, Auguste P, Ephraim PL, et al. Development of a decision aid to inform patients’ and families’ renal replacement therapy selection decisions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: a paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation. 2002;74:1377–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salter ML, Gupta N, King E, et al. Health-related and psychosocial concerns about transplantation among patients initiating dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green JA, Boulware LE. Patient education and support during CKD transitions: when the possible becomes probable. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jayanti A, Neuvonen M, Wearden A, et al. Healthcare decision-making in end stage renal disease-patient preferences and clinical correlates. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]