Abstract

Objective:

To assess the clinical practice, barriers, and facilitators in promoting smoking cessation in primary healthcare clinics in Mexico City.

Materials and methods:

A mixed method design was used. Surveys (n = 70) and semi-structured interviews (n = 9) were conducted with health personnel involved in smoking cessation clinics. Results: Quantitative data revealed that physicians were more likely than nurses to 1) ask patients if they smoke (57.9% vs 34.5%, p = .057), 2) ask patients if they are interested in quitting smoking (65.7% vs 26.9%, p = .003), 3) provide advice to quit smoking (54.3% vs 29.2%, p = .056), and 4) assess whether pharmacotherapy is needed (21.9% vs 10%, p = .285). Qualitative data showed that nurses were more likely than physicians to report lack of resources to refer patients to smoking cessation services, lack of pharmacotherapy availability, and lack of provider training in smoking cessation. Reported barriers include lack of motivation among patients, lack of time for assessment, long appointment wait times, and lack of training. Reported facilitators include existence of smoking cessation programmes and pharmacotherapy at no cost to the patient, and having a multidisciplinary team.

Conclusions:

Due to numerous barriers, smoking cessation interventions are partially implemented in primary care clinics in Mexico City. A restructuring of services is necessary, and nurses should be given a more prominent role.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Primary healthcare, Barriers to access to health services, Medical care

Resumen

Objetivo:

Evaluar las prácticas clínicas, barreras y facilitadores para dejar de fumar en clínicas de primer nivel de atención en la Ciudad de México.

Material y métodos:

Diseño de métodos mixtos. Se realizaron encuestas (n = 70) y entrevistas semiestructuradas (n = 9) a personal de salud involucrado en el servicio de las clínicas para dejar de fumar.

Resultados:

Datos cuantitativos muestran que el personal médico realizó más que el de enfermería las siguientes prácticas: preguntar a pacientes si fumaban (57,9% vs. 34,5%, p = 0,057), si tenían interés en dejar de fumar (65,7% vs. 26,9%, p = 0,003), brindar asesoría (54,3% vs. 29,2%, p = 0,056) y necesidad de farmacoterapia (21,9% vs. 10%, p = 0,285). El personal de enfermería informó más que el personal médico la falta de recursos, farmacoterapia y necesidad de capacitación para asesoría. Los resultados cualitativos muestran como barreras: percepción de falta de motivación para dejar de fumar entre pacientes, falta de tiempo en consulta, largos tiempos de espera para citas y falta de capacitación; y como facilitadores: contar con servicio para dejar de fumar, farmacoterapia sin costo, y equipo multidisciplinario.

Conclusiones:

Las intervenciones para dejar de fumar se implementan parcialmente. Es necesaria una reestructuración de los servicios, donde el personal de enfermería tenga un mayor rol.

Introduction

Smoking causes 6 million deaths a year worldwide, which is predicted to increase to 8 million by 2030.1 Approximately 4 million people will die from tobacco-related diseases in the next decade if smoking rates do not change.1 Article 14 of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) states that parties to the Convention “shall take effective measures to promote cessation of tobacco use and adequate treatment for tobacco dependence”.2 Mexico is one of 15 countries with a high burden of tobacco-related diseases;3 with a total population of 120 million,4 > 14.3 million adults (16.4%) are current smokers5 and rates remained unchanged from 2009 to 2015. According to the 2017 Global Adult Tobacco Survey,5 80% of smokers were planning or considering quitting, 60% had tried to quit in the past 12 months and only 5.9% were advised to quit by physicians.5 It is imperative that access to smoking cessation resources, programmes, and services are ensured to reduce smoking-related morbidity and mortality in Mexico.

Primary healthcare services, as the gateway to the population, constitute a great opportunity to facilitate access to resources for people who want to quit smoking. Mexico’s primary healthcare providers are an excellent platform to reduce tobacco use in Mexico.6 One of the main interventions recommended by the WHO7 for smoking cessation is based on the 5 As: Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange. The results of a systematic review showed that 65% of medical staff “Ask”, 63% “Advise”, 36% “Assess”, 44% “Assist”, and 22% “Arrange”.8 A meta-analysis evaluating smoking cessation interventions delivered by nurses showed a modest but positive effect on smoking cessation in adults.9 In Mexico, healthcare providers only ask, assist, and advise smokers and thus are missing the opportunity to meet all 5 As.10

Smoking control policies in Mexico do not include smoking cessation services or programmes in all healthcare facilities. There are 155 smoking cessation clinics,11 mainly embedded in primary care units of a public sub-sector that provides care to government employees. Barriers to implementing smoking cessation services in public health systems in low/middle income countries such as Mexico include inadequate training, lack of time and limited number of health professionals to deliver these services.12,13 Studies on strategies to scale up smoking cessation treatment services in primary care have been mainly conducted in high-income countries.14

The present study aimed to evaluate clinical practice barriers and facilitators within the framework of the clinical programme for smoking cessation from the perspective of healthcare providers in two primary health units in Mexico City. Our intention is that the results of this study will help to decrease smoking in Mexico by improving the design, implementation, and evaluation of future health actions at the national level, and the uptake of smoking cessation services in primary healthcare in Mexico.

Methods

Study design

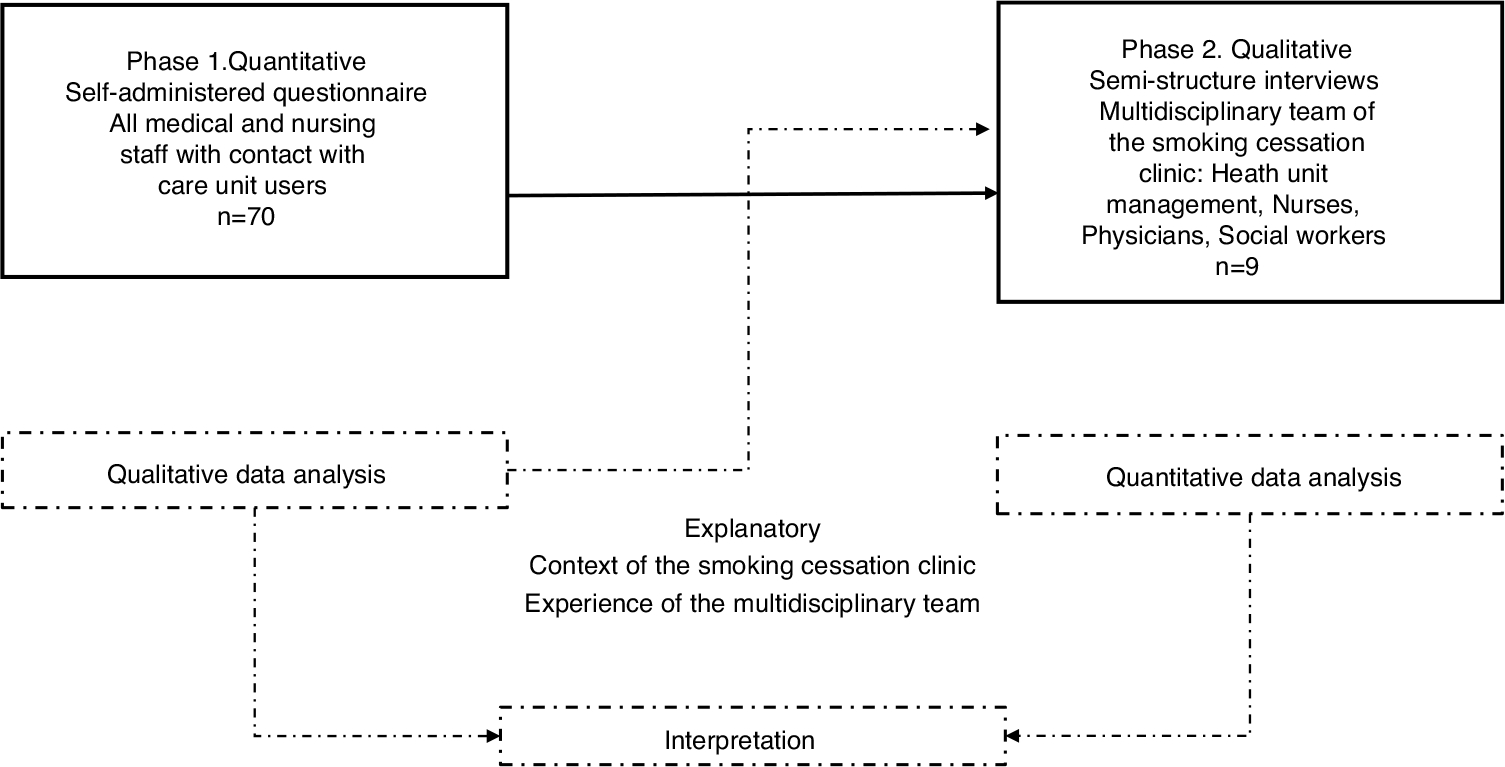

Explanatory sequential mixed methods design (quantitative and qualitative)15 conducted in two phases (Fig. 1). The first phase (quantitative) sought to determine the perspective of the medical and nursing staff regarding clinical practice and the barriers they identify in the service provided by the smoking cessation clinic in their health unit. The second phase (qualitative) examined the experience of the multidisciplinary team that runs the smoking cessation clinic, regarding clinical practices, barriers, and facilitators. The aim of conducting this type of study was that the quantitative phase would provide information to strengthen the in-depth research in the qualitative phase. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Study setting

The study was conducted in two primary care units in the south of Mexico City, between February and July 2015. These centres provide health services to the eligible population, State workers. Both centres have a smoking cessation clinic (group counselling and pharmacotherapy treatment) that is free of charge.

Eligibility

In the quantitative phase, all the physicians and nurses with direct contact with health unit users were eligible (approximately 45 people per unit, 78% response rate). In the qualitative phase, the staff of the multidisciplinary team staffing the smoking cessation clinic was eligible; this team includes health unit management, medical, nursing, and social work staff.

Data collection instruments

Phase I. Quantitative

A self-administered questionnaire, developed by the research team and validated by experts, was used on two topics: clinical practices and barriers. The questions explored healthcare providers’ actions during the first and subsequent medical visits regarding users’ smoking behaviour, as well as the barriers they perceive to providing smoking cessation services in their healthcare facility. With prior informed consent, the questionnaire was administered by the research team in groups during one of the monthly educational sessions held by healthcare staff in their work units.

Phase II. Qualitative

A semi-structured interview guide was used, developed by the research team based on the data from the quantitative phase and validated by experts, around three domains: practices and experiences in identifying patients who smoke and referral to a smoking cessation programme, barriers, and facilitators in the care process for patients who smoke. The interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were conducted by members of the research team with experience in qualitative work and with healthcare personnel. They were conducted in private spaces in the health units and by appointment with the staff to be interviewed. With prior informed consent, all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis

Sample means, standard deviations and frequencies were calculated for the quantitative data. Differences were assessed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact probability tests if the cells had a count of less than 5.

We used Atlas-Ti® (v.6.1) for the qualitative data analysis. Two members of the research team coded the interviews independently and had meetings to reach agreements. The steps of the analysis were based on the method proposed by Taylor and Bogdan,16 which covers: 1) identification of themes and development of concepts and propositions; 2) coding of the data according to the large blocks of themes identified and, 3) understanding of the data according to the context and the respondents themselves. Eight categories were identified on clinical practices, barriers, and facilitators of care, 1) Identification: ask patients if they smoke; 2) Advise: patients about quitting smoking; 3) Assess: whether the patient wants to try to quit smoking; 4) In patients: ask about motivation to quit smoking; 5) Time as a constraint; 6) Lack of training; 7) Free service; and 8) Interdisciplinary team coordination.

Results

Phase I. Quantitative

A total of 70 participants completed the survey. The majority were physicians (57.1%, n = 40) and 42.9% (n = 30) nurses. Table 1 shows the differences in the practices of each group at the first and subsequent visits. During the first visit, significantly more physicians “Ask” patients if they smoke or use any type of tobacco (57.9%), compared to 34.5% of nurses (p = .057); and 65.7% of physicians and 26.9% of nurses (p = .003) “Advise” by asking patients who smoke if they are interested in quitting. Just over half of the physicians (54.3%) compared to 29.2% of the nurses “Assess” by providing smoking cessation advice (p = .056). Statistically significant differences were found in all four practices in subsequent visits, and a significantly higher proportion of the physicians implement all four practices compared to the nurses.

Table 1.

Clinical practice of healthcare personnel during first and subsequent medical consultations with smokers in primary care clinics of Mexico City, n = 70.

| Practice in the first consultation |

Physicians |

Nurses |

P b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n % | n% | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Ask whether the patient smokes or uses any | No | 16 | 42.1 | 19 | 65.5 | .057 |

| tobacco products | Yes | 22 | 57.9 | 10 | 34.5 | |

| Ask whether the patient is exposed to | No | 28 | 73.7 | 22 | 75.9 | .839 |

| second-hand smoke | Yes | 10 | 26.3 | 7 | 24.1 | |

| If the patient smokes, ask whether they want | No | 12 | 34.3 | 19 | 73.1 | .003 |

| to quit | Yes | 23 | 65.7 | 7 | 26.9 | |

| If the patient smokes, offer advice on how to | No | 16 | 45.7 | 17 | 70.8 | .056 |

| quit smoking | Yes | 19 | 54.3 | 7 | 29.2 | |

| If the patient smokes, discuss whether they | No | 23 | 78.1 | 18 | 90.0 | .285 |

| need pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (NRT, bupropion, varenicline)a | Yes | 7 | 21.9 | 2 | 10.0 | |

| If the patient smokes and if necessary, offer | No | 15 | 45.5 | 14 | 66.7 | .128 |

| pharmacotherapy treatment or refer to a specialist clinica | Yes | 18 | 54.5 | 7 | 33.3 | |

| During the subsequent consultation | ||||||

| Ask about current tobacco use | No | 12 | 36.4 | 16 | 76.2 | .006 |

| Yes | 21 | 63.6 | 5 | 23.8 | ||

| Ask whether the patient who smokes has quit | No | 12 | 37.5 | 16 | 76.2 | .011 |

| smoking or has use any tobacco products | Yes | 20 | 62.5 | 5 | 23.8 | |

| Ask whether the patient who smokes has | No | 17 | 53.1 | 17 | 81.0 | .046 |

| relapsed in their use of tobacco | Yes | 15 | 46.9 | 4 | 19.0 | |

| Reinforce messages about the importance of | No | 8 | 24.2 | 14 | 63.6 | .003 |

| quitting smoking | Yes | 25 | 75.8 | 8 | 36.4 | |

These activities are not specific functions of nurses in Mexico.

p-value calculated using the t-test and χ2 test.

Regarding barriers, although not statistically significant, the nurses reported more lack of resources, lack of smoking cessation medication, lack of training, and lack of experience in cessation interventions compared to the physicians (Table 2).

Table 2.

Barriers to smoking cessation in primary care clinics, Mexico City.

| Barriers |

Physicians | Nurses | P a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n % | n % | |||

|

| ||||

| Lack of resources or referral to smoking | No | 21 67.7 | 13 54.2 | .304 |

| cessation interventions | Yes | 10 32.3 | 11 45.8 | |

| Lack of time for counselling or appropriate | No | 14 40.0 | 12 52.2 | .362 |

| referral | Yes | 21 60.0 | 11 47.8 | |

| Lack of cessation medication | No | 22 71.0 | 17 68.0 | .810 |

| Yes | 09 29.0 | 08 32.0 | ||

| Lack of smoking cessation skills training | No | 19 67.9 | 12 54.5 | .336 |

| Yes | 09 32.1 | 10 45.5 | ||

| Lack de experience in smoking cessation | No | 20 60.6 | 12 48.0 | .339 |

| interventions | Yes | 13 39.4 | 13 52.0 | |

| Quitting smoking is not a priority for smokers | No | 21 60.0 | 15 60.0 | 1.000 |

| when they attend for consultation | Yes | 14 40.0 | 10 40.0 | |

| Pharmacotherapy treatments are not well | No | 11 31.4 | 08 32.3 | .878 |

| accepted by patients who smoke | Yes | 24 68.6 | 16 67.7 | |

χ2 test.

Phase II. Qualitative

Nine professionals who worked in the smoking cessation clinic were interviewed: Medical Directors (1), Programme Directors (2), physicians (2), nurses (2), and social workers (2). The mean age was 49 years, and the majority (55.6%) were women.

After a first reading of the interviews, we decided to continue the analysis by considering the profession of the respondents, since two coinciding forms emerged in the discourse. Therefore, we grouped the multidisciplinary team into two: on the one hand, medical management, programme management, medical and social work staff (for practical purposes we call them medical and administrative staff), and on the other, nursing staff.

Clinical practice

All the healthcare providers reported clinical practice with the smoking population, using the 5 As strategy. They reported primarily including the first two steps of the strategy in their practice: asking patients if they currently smoke and advising them to stop smoking. Only the nurses reported asking beyond the 5 As regarding the patient’s desire to try to quit smoking, which the physicians did not (Table 3).

Table 3.

Qualitative phase: comparison by themes and domains, selected testimonies from key respondent interviews, n = 9.

| Domain | Themes | Medical and administrative staff | Nurses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Practice: | Identification: | 1) “Yes, I usually do because it is part of their medical history and to get to know the patient that I’m talking to” (Medical Director, Clinic 2) | “Yes, I do ask them if they smoke. In fact, they arrive impregnated with the smell of smoke and we talk about why they smoke. I let them know that smoking is more harmful for those of |

| Describe your experience caring for smoker patients | Ask patients whether they smoke | 2) “If we can smell it, we ask, are you a smoker? Then we’ll start to give you some information” (Social worker, Clinic 1) 3) “I’m usually very sensitive to smell. I ask them “how many cigarettes do you smoke?”. I don’t ask them if they smoke because I can smell how they smell” (Social worker, Clinic 2) |

us who don’t smoke. We try to make them understand that they should be more considerate, in terms of the way they smoke” (Nurse, Clinic 2) |

| Advise: The patients on how to quit smoking |

1) “Yes, I inform them of the benefits of quitting smoking and that we have a comprehensive smoking cessation programme, with psychological support, medication and medical care”(Physician, Clinic 1) 2) “Yes, I write in their notes, and I tell them about the consequences for their health. Then I invite them to our smoking cessation programme here in the clinic” (Director of the smoking cessation programme, Clinic 2) |

As nurses, we have to give talks on prevention, and so we occasionally give talks to smokers to help” (Nurse, Clinic 1) | |

| Assess: If the patient wants to try to quit smoking | Not reported | “If they want to quit smoking, I refer them to the Director of the smoking cessation programme” (Nurse, Clinic 1) | |

| Barriers: | In the patients: There is no motivation to quit smoking | 1) “If a patient doesn’t have a strong reason to quit smoking, they won’t. That’s what I’ve observed in my experience, people say “well, it’s not doing me any harm, right know, I haven’t been caused any harm; on the contrary, I benefit and gain pleasure from smoking, so I’ll go on smoking, as I see no reason to quit”. So that’s where the problem lies, they don’t know the damage to their health that smoking can cause in the short, medium and long term.” (Director of smoking cessation programme, Clinic 1) | 1) “They find it difficult to start the process of quitting smoking” (Nurse, Clinic 1) |

| What do you think are the factors that prevent patients who smoke from wanting to quit? | 2) “I give my time to help them, but they don’t come back [to the clinic]. It is the hardest addiction to stop, and I’ve had groups of alcoholics anonymous come and tell me that it was easy to give up alcohol but not tobacco” (Director of the smoking cessation programme, Clinic 2) | 2) “I ask them if they really want to quit smoking and they find it difficult, I refer them to the social worker for follow up” (Nurse, Clinic 2) | |

| Time as a constraint | 1) “They only give us 15 minutes and in those 15 minutes we have to include that counselling, but it is not only smoking, but alcohol consumption too, for obvious reasons, it is more entrenched as it entails more mental problems” (Medical Director, Clinic 2) 2) “We have the staff, we have everything to do it, the only thing we need is time! There isn’t enough time for this as in other programmes” (Director of the smoking cessation programme, Clinic 1) 3) “It’s 15 minutes for each consultation, and therefore it’s not enough time. Maybe it should be the responsibility of the nursing staff as well, while the patient is waiting for the consultation, talk to them about smoking, give more information and raise awareness in the patient” (Social worker, Clinic 1) |

"Most of the appointments for the smoking cessation group sessions are in the morning. And a lot of patients can only come in the afternoon because they work in the morning” (Nurse, Clinic 2) | |

| Lack of training | 1) “Well, we need training. There are very few trained in addiction. Those of us who are not trained don’t know how to deal with the patient from the moment they tell us they smoke. We don’t know where to direct them or to give them the right advice” (Physician, Clinic 1) 2) “I think there should be more staff trained in smoking. It’s important to train both the medical and the nursing staff” (Social Worker, Clinic 1) |

“Yes, more training, more tools in the clinic, like posters” (Nurse, Clinic 1) | |

| Facilitators: What do you think are the factors that help patients who smoke to want to quit? | Free service | “We have smoking cessation medication available, and it is a free programme” (Physician, Clinic 1) | “I say yes, we offer free medication. I think a lot of people come for the medication more. I think that it helps them to know that they will get the help they need to quit smoking” (Nurse, Clinic 1) |

| Multidisciplinary team | “Between us we have the capacity to implement the programme. This delegation gives us that capacity. Every two months the Directors receive training” (Director of the smoking cessation programme, Clinic 1) | Not reported | |

Barriers to smoking cessation

Patients’ lack of motivation to quit smoking was perceived as one of the main barriers by all the healthcare providers. Several institutional barriers were also reported, including having little time for brief counselling during the consultation; the nursing staff also mentioned that programme times are limited (Table 3).

The long waiting times to make an appointment with the smoking cessation clinic were reported as another barrier, because if a patient wants to attend the clinic and the cycle of 12 group sessions has already started, they must wait for the sessions to finish, i.e., 12 weeks:

Respondent: “The problem is that we tell them to come in a few months and by then the patient won’t come” (Programme Director, Clinic 1).

Other perceived barriers concern access to the smoking cessation clinic, as it is not accessible to all patients who attend the health unit, because they need to be eligible members of the sector to which the service is provided. Furthermore, the programme is not sufficiently promoted to the user population:

Respondent: “All the doctors at the clinic know that it [the smoking cessation clinic] exists, unfortunately very few make referrals” (Programme Director, Clinic 1).

Similarly, the nurses, primarily, identified the inadequate management by the unit’s administration in allocating exclusive physical spaces to run the smoking cessation clinic:

Respondent: “There is no exclusive space for this; it’s as if they [the Directors] attach no importance to smoking, and therefore to the problem” (Nurse, Clinic 1).

Lack of training to address smoking cessation is another barrier reported by staff. The Programme Director mentioned that all staff should be able to identify a smoker, but unfortunately this is not the case due to lack of training. Regarding advising patients to quit smoking, not all healthcare providers are prepared to implement this step:

Respondent: “Well, there are not many doctors who are trained in addiction, there are very few who are trained and most of the time those who are trained do not know how to treat the patient when we receive them and confirm that they are smokers. Many of us don’t know how to manage them and many don’t give the right guidance” (Medical director, Clinic 1).

Similarly, the lack of material resources for the programme was described as a barrier:

Respondent: “the staff need the physical resources, such as questionnaires, educational films, and general information to help people who smoke” (Centre Director, Clinic 2).

Facilitators to address smoking cessation

There were few facilitators reported compared to barriers. One facilitator is that the service is free of charge, although only for a certain sector of the population; the smoking cessation clinic service and medication are free of charge for insured patients.

Respondent: “We offer free medication. I think a lot of people come mainly for the medication. I think that helps them to know that they will get the help they need to stop smoking” (Nurse, Clinic 1).

Another facilitator is that the smoking cessation service provided by the clinic is delivered with the multidisciplinary team, who receive continuous training, which enables the successful implementation of the cessation interventions provided there:

Respondent: “We have the capacity among us to implement the programme. Every two months the Directors receive training” (Programme Director, Clinic 1).

Discussion

Although healthcare providers in Mexico are encouraged to address smoking cessation with their patients at every visit,17 most providers do not initiate smoking cessation treatment for their patients.10 The results of this study show opportunities to improve the role of healthcare providers in identifying and providing smoking cessation advice.

The findings suggest that physicians use the “Ask and Advise” strategies more frequently than the “Assess, Assist and Arrange” strategies. This result is consistent with studies conducted in other countries that have evaluated their practices. However, except for the first strategy used to identify smokers (“Ask”), nurses were found to rarely use the other strategies, which is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Turkey.18 This suggests that the possibilities to engage in the process of helping service users to quit smoking varies according to the professional role and possibly according to the time available to them. In countries such as the UK,19 primary care units that have a smoking cessation clinic state that nurses should advise smokers, assess their desire to quit and inform them of available support services and resources. This is relevant because people who smoke and receive assistance in smoking cessation services are four times more likely to quit.19

In our study, there was a significant difference between physicians and nurses in all actions during subsequent visits; this difference could be because follow-up is usually conducted by medical staff. Like the results found in other countries,18,20,21 some barriers were identified concerning the organisation of the care service. These include, mainly reported by the physicians, the lack of time available during the consultation, which coincides with that reported by Panaitescu et al.22 In primary care units in Mexico, the high demand for care and the insufficient number of professionals means that physicians have limited time for the clinical care of service users. Furthermore, the excessive administrative processes that must be recorded for each patient during consultations mean healthcare providers have considerably less time for patients.

Another barrier reported by at least half of the nurses is the lack of training in specific skills to provide smoking cessation care. In this regard, our study’s finding of less involvement of nurses in some of the 5 steps could be related to this perceived barrier, and therefore actions could be guided focussing on the role of nurses in providing smoking cessation services, as suggested by the Pan American Health Organization, which has developed the Strategic Directions for Nursing in the Region of the Americas to reinforce nursing and midwifery.23 The purpose of this strategy is to empower, support and discuss with nursing and midwifery leaders to make them more aware of their role in smoking cessation. Professionals must be able to work across the professions and make decisions that improve working conditions, expand access and universal coverage, and promote social wellbeing.24

In addition to the above barriers, the lack of interest shown by smokers25 was identified, even when they had diseases that could be a consequence their smoking.26 This finding coincides with that reported in other studies25,26 and, together with the time (sometimes up to 12 weeks) that smokers must wait to start the programme, can affect their motivation, and increase their lack of interest in quitting smoking.

The availability of free cessation programmes, as well as an integrated multidisciplinary team, is acknowledged by healthcare workers as a facilitator, and this enhances the smoking cessation clinic. However, this service is only offered to people who qualify for health services (e.g., people who have health insurance through the State).

Despite a strong commitment to tobacco control, there remain gaps in Mexico’s smoking cessation services. Since 2004, the government has signed and ratified the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, and in 2008 enacted the General Law on Tobacco Control,27 seeking the implementation of strategies based on the Mpower Policy Package to Reverse the Tobacco Epidemic.28 Smoking cessation support programmes in Mexico have two components: psychotherapeutic support and pharmacological treatment.17 According to the findings of our study, although medication such as nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline are available, medical staff outside the programme are not adequately trained to prescribe them, and this directly affects patients. While the insufficient supply of medication is a long-standing issue for the Mexican health system, providing brief counselling for staff in settings where medication is available could facilitate support for smoking cessation.

In this regard, it is worth noting that recent evidence suggests other methods that contribute towards decreasing smoking rates in the country, such as advances in mobile technologies that allow for flexible delivery of text messages, used to tailor content to individual motivational and behavioural needs for smoking cessation.29 This is consistent with a Cochrane meta-analysis that indicated that smokers who received text messaging-based interventions were around 1.7 times more likely to quit smoking,30 and with recent research indicating that mobile health interventions in Mexico are feasible and have promising results in Mexican smokers.31

A limitation of the study was that the respondents were healthcare personnel working in an institution that has access to free smoking cessation programmes that are not available to the general population. This may be different from other healthcare personnel working for other health institutions within the Mexican health system. Another limitation of our study is the impossibility of interviewing the professionals more than once, to delve more deeply into more detailed aspects of the care process in the clinic and into the involvement of the other professionals, barriers to this, to inform our feedback on aspects more specific to the participating health units.

From our study we conclude that training should be considered within strategies for tobacco control of all healthcare personnel who have direct contact with service users. This training should include, in addition to strategies such as the 5 As, instruction on where to refer a user who wants to join the smoking cessation clinic, and be involved in the follow-up of this process. We also conclude that nurse leaders should play a central role in tobacco control strategies, as they have played a major role in the history of tobacco control.

We consider that the strategy for tobacco cessation is not sufficiently clear for all health personnel in these care units, or the role that each should assume in the strategy, especially considering that the personnel in this study are highly motivated to become involved.10,32 Future studies should consider piloting interventions to promote nurse leadership in the provision of smoking cessation services.

What is known?

Although healthcare providers in Mexico are encouraged to address smoking cessation with their patients, most providers do not promote smoking cessation treatment. Nurses should play an active role in smoking cessation, as those who receive help are four times more likely to quit smoking.

What does this paper contribute?

Most of the physicians reported a lack of time for giving advice as a major barrier. This contrasts with the nurses who stated that a major barrier was the lack of training to provide smoking cessation advice, which could make a change in the figures for quitting smoking, thus affecting the low motivation of smokers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ISSSTE staff; Administrative Managers, Drs Margarita Blanco, Blanca de la Rosa, Héctor Morales, and Lydia Cecilia López; Directors and Managers of the health units’ smoking cessation programme, Drs Luis Alberto Blanco, Martha Medina, Felipe Ruíz and Lic. Angélica Marina García.

Funding

This paper was funded by Mexico’s Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT)(National Science and Technology Council): Salud-2013-01-201533.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Bolaños R, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Rojas-Carmona A, Cartujano-Barrera F, Arana-Chicas E, Cupertino AP, et al. Prácticas, barreras y facilitadores de proveedores de salud en clínicas para dejar de fumar en México. Enferm Clin. 2022;32:184–194.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, Warning about the dangers of tobacco [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/globalreport/2011/en/, 2011.

- 2.Organización Mundial de la Salud. Artículo 14. In: Organización Mundial de la Salud. Convenio marco de la OMS para el control del tabaco. Ginebra: OMS; 2003. [accessed 18 Ene. 2021]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42811/1/9241591 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/about/partners/bloomberg/mex/en/, 2015.

- 4.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/intercensal/2015/doc/eic2015presentacion.pdf, 2015.

- 5.Encuesta Global de Tabaquismo en Adultos [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/survey/gats/mex-report-2015-spanish.pdf, 2017.

- 6.Lindson-Hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD006936, 10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Licencia: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/51350/9789275320815spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartsch A-L, Härter M, Niedrich J, Brütt AL, Buchholz A. A systematic literature review of self-reported smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168482, 10.1371/journal.pone.0168482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheibmer MS, O’Connell KA. Promoting smoking cessation in adults. Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;37:331–40, 10.1016/s0029-6465(01)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponciano-Rodriguez G The urgent need to change the current medical approach on tobacco cessation in Latin America. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52:S355–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE). Directorio de clínicas para dejar de fumar [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/issste/articulos/directorio-de-clinicas-para-dejar-de-fumar.

- 12.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. London: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becoña E Dependencia del tabaco. Manual de casos clínicos. 1.a ed Madrid: Sociedad Española de Psicología Clínica, Legal y Forense; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen K-A, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2010:199–213, 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL. Choosing a mixed methods design. In: Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL, editors. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Los Ángeles: SAGE; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introducción a los métodos cualitativos en investigación. Barcelona: Paidós; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guía de práctica clínica [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: http://www.cenetec.salud.gob.mx/descargas/gpc/Catalogo-Maestro/108-GPC_ConsumodeTabacoyhumodetabaco/SSA_108_08_EyR1.pdf, 2009.

- 18.Sonmez CI, Aydin LY, Turker Y, Baltaci D, Dikici S, Sariguzel YC, et al. Comparison of smoking habits, knowledge, attitudes and tobacco control interventions between primary care physicians and nurses. Tob Induc Dis. 2015:37, 10.1186/s12971-015-0062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Public Health England [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-smoking-and-quitting-in-england/smoking-and-quitting-in-england, 2015.

- 20.Awareness Jradi H., practices, and barriers regarding smoking cessation treatment among physicians in Saudi Arabia. J Addict Dis. 2017;36:53–9, 10.1080/10550887.2015.1116355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li IC, Lee SY, Chen CY, Jeng YQ, Chen YC. Facilitators and barriers to effective smoking cessation: counselling services for inpatients from nurse-counsellors’ perspectives-a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:4782–98, 10.3390/ijerph110504782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panaitescu C, Moffat MA, Williams S, Pinnock H, Boros M, Oana CS, et al. Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation assistance a qualitative study among Romanian family physicians. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14022, 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panamerican Health Organization. Strategic Directions for Nursing in the Region of the Americas. [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/50956/9789275120729_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 24.Cassiani SHB, Fernandes MNF, Lecorps K, Silva FAM. Leadership in nursing: why should we discuss it? Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2019;43:e46e462, 10.26633/RPSP.2019.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wray JM, Funderburk JS, Gass JC, Maisto SA. Barriers to and facilitators of delivering brief tobacco and alcohol interventions in integrated primary care settings. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2019;21:19m02497, 10.4088/PCC.19m02497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodgers-Melnick SN, Webb Hooper M. Implementation of tobacco cessation services at a comprehensive cancer center: a qualitative study of oncology providers’ perceptions and practices. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:2465–74, 10.1007/s00520-020-05749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diario Oficial de la Federación [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: http://www.conadic.salud.gob.mx/pdfs/ley_general_tabaco.pdf, 2008.

- 28.Organización Mundial de la Salud. MPOWER: un plan de medidas para hacer retroceder la epidemia de tabaquismo. OMS; 2008. [accessed 18 Ene 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_spanish.pdf?ua=1.

- 29.Ybarra ML, Holtrop JS, Bağci BA, Emri S. Design considerations in developing a text messaging program aimed at smoking cessation is among adult smokers in Ankara, Turkey. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e103, 10.2196/jmir.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Rodgers A, Gu Y, Dobson R. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD006611, 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cupertino AP, Cartujano-Barrera F, Perales J, Formagini T, Rodriguez-Bolanos R, Ellerbeck EF, Ponciano-Rodriguez G, Reynales-Shigematsu LM. “Vive Sin Tabaco. . . ¡Decídete!” Feasibility and acceptability of an eHealth smoking cessation informed decision-making tool integrated in primary healthcare in Mexico. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25:425–31, 10.1089/tmj.2017.0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson KV, Verbiest MEA, Crone MR, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Assendelft WJ, Smith BJ. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;16:CD000214, 10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]