Abstract

In many low-income countries, the conservation of natural resources in protected areas relies on tourism revenue. However, tourist numbers in Africa were severely reduced by the COVID-19 pandemic, thus, putting the conservation of these important protected areas at risk. We use records from gate passings at national parks across Tanzania to demonstrate the immediate and severe impact on tourist numbers and revenues resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions, and whether international and local (East African) tourists were affected equally. We discuss mechanisms that may reduce future negative impacts of sudden loss of revenue from international tourism, such as increasing the revenue portfolio and thereby decrease the dependency on revenues from international tourists. More important, we encourage local governments, national park authorities, and the world community to further develop and initiate external funding options to reduce the dependency on income from international nature-based tourism to preserve national parks and biodiversity. An additional long-term goal for ensuring sustained conservation would be to increase benefits to local communities adjacent to national parks, encouraging local involvement and thereby reducing the dependence on external funding in the future.

Keywords: Conservation, COVID-19, National parks, Pandemic, Revenues, Tourism decline

1. Tourism and conservation

A prominent strategy to safeguard biodiversity is through establishments of protected areas (Watson et al., 2014). Low-income countries in the south host many important protected areas including in the form of national parks, that typically are subject to more intense threats than protected areas in high income countries (Schulze et al., 2018). In many of these countries, tourism revenues generate a substantial part of the funding needed to support biodiversity conservation (Steven et al., 2013). The East African country of Tanzania has one of the largest shares of protected land in the world, comprising more than 300,000 square kilometres (km2), representing more than 30 % of Tanzania's total land area (Riggio et al., 2019). Among twenty-two national parks comprising over 100,000 km2, five generate approximately 95 % of the total annual revenues from national parks in Tanzania (TANAPA unpublished data). These include well-known parks in the northern circuit with the following rank: Serengeti, Kilimanjaro, Tarangire, Lake Manyara, and Arusha. Tanzania is among the top biodiversity hotspot countries in the world (Hunt and Gorenflo, 2019), and several protected areas are either biosphere reserves, world heritage or Ramsar sites.

The annual number of tourists to Tanzania has increased at a relatively constant rate during the past two decades (Fyumagwa et al., 2013). The economy of Tanzania depends on tourism, which has been estimated to contribute directly and indirectly as much as 17 % of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 (WBG, 2021). Taxation of the tourism industry creates national revenue that, in principle, may be used to develop infrastructure such as roads, schools, and other public goods and services. Although there are also costs associated with living close to protected areas (Green et al., 2018), local people surrounding national parks or other protected areas may diversify their livelihood portfolios and benefit from income generating activities associated with adjacent eco-tourism ventures (Zacarias and Loyola, 2017; Kideghesho et al., 2021). Before COVID-19, Tanzanian national parks were self-sustained based on income from tourist revenues. However, during and after COVID-19 these national parks now rely on receiving subsidies from the government to fund park administration, park rangers, other maintenance costs, and outreach activities (URT, 2020), in addition to donor support. Protected areas in Eastern Africa largely rely upon state support, constituting a larger proportion than donor funding (Lindsey et al., 2018). Thus, the financial sustainability1 of national parks and conservation in this region, to a large extent, relies either upon revenues generated from and/or priorities of the government (Emerton et al., 2006). As a consequence, conservation has become vulnerable to fluctuations and particularly sudden decreases in international tourism, for instance, due to unpredictable events, including the COVID-19 pandemic (Corlett et al., 2020; Kideghesho et al., 2021).

Protected areas may be important for local livelihoods through benefit sharing (Kegamba et al., 2022). Although most revenue generated by wildlife tourism remains under governmental control (Ingram et al., 2014), policies in most countries promote that more of these funds should be shared with adjacent communities. Moreover, local communities are widely believed to be more likely to protect wildlife if they benefit from national park conservation. Furthermore, nature-based tourism is also seen offer job opportunities for local communities. However, around Serengeti national park, benefits seem to be distributed at the community-level, rather than household or individual level (Kaltenborn et al., 2008).

2. Tourism and COVID-19

International tourism has been negatively impacted by COVID-19 with severe consequences (Gössling et al., 2021; Škare et al., 2021). Tourism in Tanzania is no exception (Kideghesho et al., 2021). COVID-19 was first reported in December 2019 in the Hubei Province, China (Huang et al., 2020). Following the first documented COVID-19 victim in Tanzania (16 March 2020, week 12), all international passenger flights were suspended, to Europe (17 March 2020, week 12) and the rest of the world (12 April 2020, week 15). However, Tanzania was among the first African countries to re-open borders (TCAA, 2020) in mid-May 2020 (Patterson, 2022). Yet information about the implications for tourism entries and revenue collection in Tanzania's national parks remains largely unexplored.

3. Past disruptions in tourism

The August 1998 bombings of the United States embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam and the September 2001 (9/11) terrorist attack in the United States had considerable albeit temporary impacts on East African and worldwide tourism, respectively (Kuto and Groves, 2004; Sandler and Enders, 2008; Korstanje and Clayton, 2012). The global financial crisis in 2008–2009 also slowed down tourism in Tanzania to some extent, although tourist numbers again rapidly recovered (Gereta and Røskaft, 2010; Fyumagwa et al., 2017). These past events have shown how vulnerable conservation is to sudden reductions in international tourism and the associated loss of revenue (Thirgood et al., 2009).

Here we aim to explore the effect of such shocks by assessing the impacts of COVID-19 on tourist numbers and its consequences on national park funding. Thereafter we discuss alternatives for diversifying sources of income for maintaining sustainable national parks in Tanzania and other low-income countries. Although this is a Tanzania case-study, our findings are relevant for conservation in other low-income countries that are equally dependent on international tourism.

4. Methods

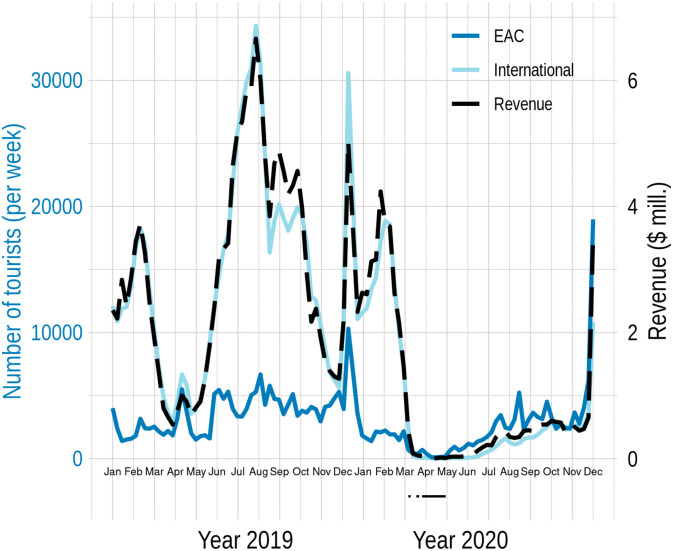

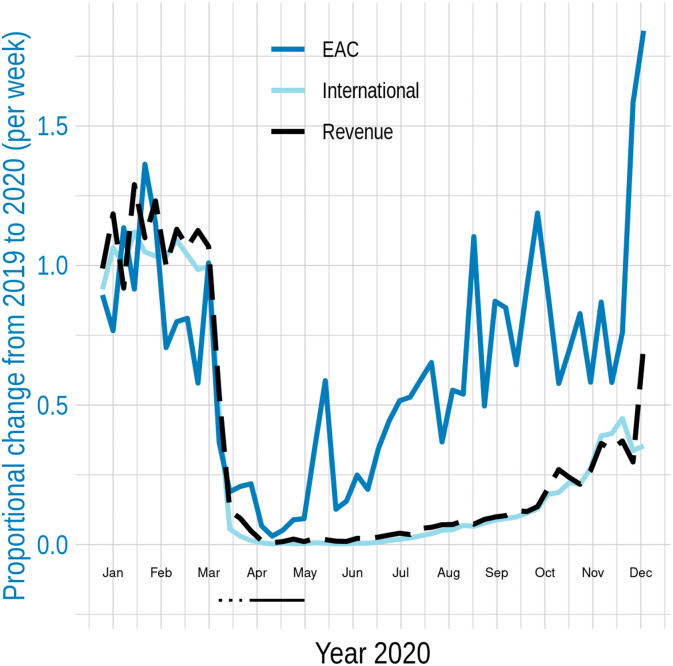

We aggregated daily tourist entry records from the gates of all Tanzanian national parks during 2019–2020, categorizing the weekly number of tourists into two major groups; a) tourists originating in countries belonging to the East African Community (hereafter ‘EAC’), and b) international tourists (all countries outside the EAC). Expatriates were excluded, on average comprising just about 2 % of visitor numbers annually. We also gathered data on the weekly revenues recorded at each gate (TANAPA, 2021). As mentioned above, tourist numbers in Tanzania have been increasing annually (Thirgood et al., 2009; Gereta, 2010; Fyumagwa et al., 2017). Therefore, weekly tourist numbers in the year 2019 (see Fig. 1 ), before the outbreak of COVID-19 in Tanzania, serves as the baseline expected number of tourists in 2020 (i.e., although this is an underestimate due to the constant increase). Thus, proportions above 1.00 in Fig. 2 represent an increase in 2020 versus 2019, whereas proportions below 1.00 represent a decrease in tourist numbers from 2019 to 2020 for a given week (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Weekly number of registered visitors from national park gates and the revenues generated, across Tanzanian national parks 2019–2020. EAC = East African Community. Weekly data are aggregated from daily park entries, TANAPA, Arusha, Tanzania (TANAPA, 2021). Horizontal line below x-axis represents the period of lockdown (dashed from mid-March to mid-April, indicating suspension of European flights, and solid from mid-April to mid-May indicating suspension of all international flights).

Fig. 2.

Weekly proportional change (i.e. weekly 2020 numbers divided by numbers from the corresponding weeks in 2019) in tourist numbers and revenues to national parks across Tanzania in 2020. EAC = East African Community. Based on daily park entries, TANAPA, Arusha, Tanzania (TANAPA, 2021). Horizontal line below x-axis represents the period of lockdown (dashed from mid-March to mid-April, indicating suspension of European flights, and solid from mid-April to mid-May indicating suspension of all international flights).

We have assessed to what degree encouraging local tourism can alleviate the economic loss from sudden loss of international tourists, and we discuss alternative strategies that have formerly been adopted in this region.

5. Results and discussion

Our results document the loss of more than 550,000 international tourists in the period March 12th-December 31st, 2020 compared to pre-covid March 12th-December 31st, 2019 (i.e. a 91 % decline), and a corresponding revenue loss of more than 100 mill. USD (i.e. a 88 % decline). An immediate decline in tourists entering Tanzanian national parks was observed from March 2020 following the restrictions on international fights (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The number of tourists visiting Tanzania in March is usually low, therefore during the following months, the economic loss in international tourist revenues gradually became more prominent - a time generally regarded as the high tourist season in Tanzania (June–October, especially July and August). During the peak in the first week of August 2020 (week 32), there were 32,979 fewer international tourists than during the same week in 2019 (i.e. a 96 % decrease). This translates into a $6.25 million (or 94 %) reduction in generated revenue compared to the same week the year before (i.e. 2019). Interestingly, the international tourist numbers during high season remained low also after the borders were re-opened and thus were not only driven by Tanzania's national travel ban but instead by the general impact of the pandemic on international tourism. The severe drop in revenue was similar across the five financially most important national parks (see Fig. S1).

Domestic tourists were encouraged to visit Tanzania's national parks to ameliorate the dramatic loss of revenue from the lack of international tourists (TANAPA, 2020). A combination of this encouragement and potentially more affordable offers (Stone et al., 2021) may have offered an opportunity for more locally-based tourists. This is reflected in the higher number of visiting EAC tourists towards the end of 2020 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Despite the increase in EAC tourists, revenues remained instead closely related to the number of international tourists (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, S1), as EAC tourists pay lower park fees than international tourists (i.e. less than one-tenth of the price; TANAPA, 2019). Therefore, locally-based tourism alone could not compensate for the absence of revenue from international tourists. However, note the sudden improvement in revenue proportionally towards the end of 2020 likely caused by a substantial increase in EAC visitors (Fig. 2).

6. Impacts on local livelihoods

In many western countries, reduced mobility due to COVID-19 had a positive environmental impact (Gibbons et al., 2022). Moreover, temporary absence of visitors due to COVID-19 restrictions, have revealed the need to discuss how protected areas are managed, in order to avoid over-crowding and its negative impacts on wildlife (McGinlay et al., 2020; Newsome, 2021). In Africa, substantial adverse effects have also been observed (Lindsey et al., 2020). In some African protected areas, the reduced presence of tourists combined with weaker law enforcement due to the associated economic impacts has enabled poaching syndicates to increase and expand their operations (Rondeau et al., 2020). In addition, broken commodity chains have forced rural populations to rely more on surrounding natural resources (McNamara et al., 2020). Moreover, lockdowns shutting down private and public jobs effectively forced workers in major cities and migrant workers abroad to return home and take up rural livelihood activities, including hunting, increasing the strain on local wildlife populations (McNamara et al., 2020).

7. Future strategies

Protected areas in low-income countries have been underfunded for the past decades (Spergel, 2001; Lindsey et al., 2018; Schulze et al., 2018), largely affecting protected area management effectiveness (Leverington et al., 2010). Thus, protected areas which rely heavily on funding by revenue become especially vulnerable during crises like COVID-19 (Lindsey et al., 2020).

An important question emerging in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, therefore, is: “how can negative impacts on conservation resulting from a sudden loss of tourism revenues in low-income countries be reduced in the future?” Given the strong link between tourism numbers and protected area funding in low-income countries, an important step in adapting to potential future crises and increasing resilience would be to diversify revenue streams by developing a broader spectrum of income sources, thereby making national parks less dependent on revenue from one source (i.e., international tourists). Simultaneously, there is a need for increased awareness among local communities about their often high reliance on adjacent national parks through benefit-sharing programs and ecosystem services, including directly harvesting natural resources (Kegamba et al., 2022). For instance, Jiao et al. (2019) found that on average, 20 % (range 8–39 %) of total household income (subsistence and cash income combined) in 25 communities surrounding the Greater Serengeti-Mara Ecosystem originated from environmental resources and that reliance on ecosystem service derived income (livestock, agriculture and environmental income combined) was on average 75 % (range 70–89 %). Furthermore, households living closer to the boundary of the protected areas relied more on environmental income and were poorer. This highlights the importance of sustainable use to avoid compromising the livelihoods of these vulnerable households.

8. Increased variation in tourists

An already initiated process in Tanzania is to promote local tourism, including south-south and national tourism, to make revenues from nature-based tourism more stable (Jensen, 2018). Income from more locally based tourists could partially ameliorate the negative impacts of sudden decreases in international tourism. However, global events such as pandemics, economic crises, and social instability, among others, could also affect local tourism. The number of local tourists necessary to replace the revenue generated by international tourists would furthermore impose significant pressure on protected areas (see e.g. Schulze et al., 2018), through increased habitat degradation and disturbance (Wolf et al., 2019). To minimize such stressors, local tourism should, under normal circumstances, be encouraged during the low season, i.e., when the number of international tourists is at its lowest, to spread the pressure on infrastructure and natural resources more evenly across seasons. However, the lower revenue rates from this tourist segment would probably require an unrealistically large volume of local tourists (i.e. approximately a ten-fold increase) to compensate for the sudden loss of revenues from international tourism. Such a strategy is, therefore, hardly sustainable and can only complement other sources of income. However, an additional benefit of increasing locally-based tourism is that it may contribute to increased awareness and appreciation of national natural resources.

Other future innovative sources of revenue currently not realized to their full potential include virtual (real-time) tourism. Although largely untested in the Tanzanian safari context, studies examining the importance of virtual nature-based tourism for conservation are starting to emerge (Barker and Rodway-Dyer, 2022). Virtual tourism does not rely on physical presence and would, therefore, be less vulnerable to travel restrictions. Although virtual tourism existed prior to COVID-19, the pandemic has led to a substantial increase in demand for such activities (Sarkady et al., 2021). There is an urgent need for capacity building and infrastructure development to take advantage of this growing opportunity. Furthermore, it would require appropriate marketing by the tourism industry and national park authorities, including Tanzania National Parks. Although it is doubtful that this source of income could replace conventional tourism, it may complement current sources of income (Verkerk, 2022). A significant advantage of virtual tourism is that it creates almost no direct pressure on the national parks, in contrast to known negative effects of recreation (Schulze et al., 2018). Moreover importantly, park authorities have to develop a system that targets this kind of revenue in order to receive shares of this activity. Importantly, we urge future studies to fully monitor the effectiveness of virtual nature-based tourism in relation to tourism demand and its capacity to generate revenue.

9. Increased funding to national parks

According to Balmford et al. (2015), investments in the protection of national parks based on income from nature-based tourism are disproportional to the value of global ecosystem services provided by these areas. The international community, and especially the western world, should, according to Balmford and Whitten (2003), take greater responsibility for supporting low-income countries to sustain their valuable natural resources in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals (UN-SDGs). Protected areas that were already underfunded before COVID-19 (Lindsey et al., 2018) are faced with an even worse situation due to the multifaceted adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Lindsey et al., 2020). Hence, the gap between available and necessary funding for sustainable management of national parks and other protected areas is growing.

Several Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), including the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), and World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF), as well as international organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), have directly supported protected areas. Also, private funds such as the Grumeti Fund and Friedkin Conservation Fund have invested in local development and supported local development in communities surrounding protected areas. Moreover, these private funds may also support other conservation projects, e.g. research and anti-poaching initiatives. However, most conservation funding in East Africa has been governmental (Lindsey et al., 2018). Thus, there is potential for substantial increases in funding from the private sector.

In many countries, the Payment for Environmental Services (PES) (Wunder et al., 2008; Wunder, 2013; Whitelaw et al., 2014) functions as a reliable source of income that is not directly dependent on tourist revenues. Some PES projects, including in Costa Rica, have been considered successful (Sánchez-Azofeifa et al., 2007). However, reviewing the experience from a large body of PES projects (Wunder, 2013) found that such projects may be challenging in low-income countries. For instance, in Uluguru Mountains, lack of investors and high level of poverty were highlighted as the biggests challenges and a likely contributor to why there are proportionally few PES projects in tropical Africa (Lopa et al., 2012). In East Africa, issues such as tenure and livelihood security and appropriate communication with the local community turned out to be more critical for the success of community-based conservation projects than PES payments (Davis and Goldman, 2019). Moreover, across Tanzanian national parks there is a huge potential for investment in carbon finance projects (Koh et al., 2021).

Another option to attract external funding is through Conservation Trust Funds (CTFs). CTFs have proven successful across several continents, aiming to support and secure vulnerable areas, mainly in the global south (Spergel and Taïeb, 2008). Although CTFs are private grant-making institutions, they are often a part of protected areas' long-term cost management and must be designed considering the local context. Tanzania's first conservation trust fund was initiated in 2001, ensuring long-term, predictable support to reduce deforestation in the Eastern Arc Mountains (Eastern Arc Mountains Conservation Endowment Fund, EAMCEF). A review indicates that several conservation trust funds have functioned as intended during the past decades (Spergel and Taïeb, 2008). However, despite their success, prospects for new CTFs in Africa are uncertain, in part, due to a general lack of national biodiversity strategies and challenges in raising external funds (Spergel and Taïeb, 2008). Willingness to invest in CTFs may be facilitated by tax exemption for donations to conservation initiatives (Pasquini et al., 2011), debt for nature swaps, either inter-governmental or bilateral, converting debt into conservation funding and environmental taxes and levies on specific income streams (Spergel, 2001).

To further encourage investment from the private sector, models for more collaborative management between governments and the private sector, i.e., Collaborative Management Partnerships (CMPs), have been suggested (Baghai et al., 2018). This implies that the government (partially or fully) delegates authority to manage protected areas to a private entity and has positively demonstrated the ability to encourage private and non-profit operators to fund conservation. However, many African governments have thus far been reluctant to engage in such ventures, presumably due to concerns about undermining their sovereign power and control (Lindsey et al., 2021). In other cases, such as Tanzania's Wildlife Management Areas, decentralization policies appears to have been rolled back in effect, recentralizing central government control of financial streams and some scholars remark that the concept may have been designed for accumulation by dispossessing local communities of their land (Kicheleri et al., 2021).

10. Local community recovery

In addition to the urgent need to secure funds to safeguard protected areas, there is an urgent and associated need to reverse the adverse effects of COVID-19 on local communities and national economies. The choice of policy response to restore national economies post-COVID-19 will significantly affect future biodiversity (Sandbrook et al., 2020). Moreover, the OECD (2020) calls for ambitious support to developing countries, specifically aimed at reducing poverty rates that have increased due to the pandemic and stabilizing national economies. Sustainable long-term goals should include appropriately targeted benefits to local communities linked to the continued protection of national parks and the presence of wildlife, decreasing the impetus for poaching and illegal grazing.

11. Conclusion

In conclusion, COVID-19 has highlighted the need to urgently diversify the income portfolios to finance national park management in Africa in general and perhaps Tanzania in particular, and most importantly, decrease the future dependency on tourism revenue to fund the protection of national parks. Diversifying income sources will reduce the dependence on revenues generated from international tourism alone. Exploiting options through more locally based and virtual tourist markets could contribute to increased resilience. Increased funding beyond governmental support is also urgently needed. Many African countries consistently underfund national parks, posing a severe threat to biodiversity. There are several options for attracting external funding. We encourage a higher degree of commitment to conservation in Africa from the international community, especially during global crises such as COVID-19, to help preserve vulnerable biodiversity in national parks and other protected areas. However, further research is required to determine the optimal design and evaluate the impacts of such funding schemes. Finally, improved awareness of the reliance on protected areas in surrounding communities and involvement in their management and sharing of resulting benefits could contribute to lowering the pressure on these resources. This paper has highlighted the high economic dependency of national park management in Tanzania on revenue from nature-based international tourism and the urgent need to revert this dependency to a more sustainable future for national parks.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Proportional changes in the number of international visitors (a), EAC visitors (b) and revenue (c) for the five economically most influential national parks in Tanzania. Proportional change refers to the change from 2019 to 2020. Thus, when proportions are 1.00 the values in 2019 were equal to 2020. Horizontal line below x-axis represents the period of lockdown (dashed from mid-March to mid-April, indicating suspension of European flights, and solid from mid-April to mid-May indicating suspension of all international flights).

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (Centre of Excellence Grant 223257) to Peter Sjolte Ranke and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (AfricanBioServices grant no. 641918) to Eivin Røskaft. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Peter Sjolte Ranke: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Reviewing and Editing. Beatrice Modest Kessy, Franco Peniel Mbise, Martin Reinhardt Nielsen, Augustine Arukwe, Eivin Røskaft: Conceptualization, Writing- Reviewing and Editing,

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical staff at TANAPA for collecting and administering the park entry data. The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback on the manuscript. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Financial sustainability for protected areas has been defined as the ability to secure sufficient stable and long-term financial resources, and to allocate them in a timely manner and in appropriate form to cover the full costs of protected areas and to ensure that they are managed effectively and concistently with respect to conservation and other objectives (Emerton et al., 2006).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Baghai M., Miller J.R.B., Blanken L.J., Dublin H.T., Fitzgerald K.H., Gandiwa P., Laurenson K., Milanzi J., Nelson A., Lindsey P. Models for the collaborative management of Africa’s protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2018;218:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balmford A., Whitten T. Who should pay for tropical conservation, and how could the costs be met? Oryx. 2003;37:238–250. doi: 10.1017/S0030605303000413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balmford A., Green J.M.H., Anderson M., Beresford J., Huang C., Naidoo R., Walpole M., Manica A. Walk on the wild side: estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biol. 2015;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J., Rodway-Dyer S. The elephant in the zoom: the role of virtual safaris during the COVID-19 pandemic for conservation resilience. Curr. Issue Tour. 2022 doi: 10.1080/13683500.2022.2132921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corlett R.T., Primack R.B., Devictor V., Maas B., Goswami V.R., Bates A.E., Koh L.P., Regan T.J., Loyola R., Pakeman R.J., Cumming G.S., Pidgeon A., Johns D., Roth R. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020;246 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A., Goldman M.J. Beyond payments for ecosystem services: considerations of trust, livelihoods and tenure security in community-based conservation projects. Oryx. 2019;53:491–496. doi: 10.1017/S0030605317000898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerton L., Bishop J., Thomas L. IUCN; Gland and Cambridge, UK: 2006. Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas: A Global Review of Challenges and Options. 97pp. [Google Scholar]

- Fyumagwa R., Gereta E., Hassan S., Kideghesho J.R., Kohi E.M., Keyyu J., Magige F., Mfunda I.M., Mwakatobe A., Ntalwila J., Nyahongo J.W., Runyoro V., Røskaft E. Roads as a threat to the Serengeti ecosystem. Conserv. Biol. 2013;27:1122–1125. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyumagwa R.D., Mfunda I., Ntalwila J., Røskaft E., editors. Northern Serengeti Road Ecology. Fagbokforlaget; Bergen, Norway: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gereta E. In: Conservation of Natural Resources: Some African & Asian Examples. Gereta E., Røskaft E., editors. Tapir Academic Press; Trondheim, Norway: 2010. The role of biodiversity conservation in development of the tourism industry in Tanzania; pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gereta E., Røskaft E., editors. Conservation of Natural Resources. Tapir Academic Press; Trondheim, Norway: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons D.W., Sandbrook C., Sutherland W.J., Akter R., Bradbury R., Broad S., Clements A., Crick H.Q.P., Elliott J., Gyeltshen N., Heath M., Hughes J., Jenkins R.K.B., Jones A.H., Lopez de la Lama R., Macfarlane N.B.W., Maunder M., Prasad R., Romero-Muñoz A., Steiner N., Tremlett J., Trevelyan R., Vijaykumar S., Wedage I., Ockendon N. The relative importance of COVID-19 pandemic impacts on biodiversity conservation globally. Conserv. Biol. 2022;36 doi: 10.1111/cobi.13781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021;29:1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green J.M.H., Fisher B., Green R.E., Makero J., Platts P.J., Robert N., Schaafsma M., Turner R.K., Balmford A. Local costs of conservation exceed those borne by the global majority. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018;14 doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt C.A., Gorenflo L.J. Tourism development in a biodiversity hotspot. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019;76:320–322. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.07.009a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J.C., Wilkie D., Clements T., McNab R.B., Nelson F., Baur E.H., Sachedina H.T., Peterson D.D., Foley C.A.H. Evidence of payments for ecosystem services as a mechanism for supporting biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014;7:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S. In: The Environmental Crunch in Africa Growth Narratives vs. Local Realities. Abbink J., editor. Palgrave Macmillan/Springer; 2018. Is growing urban-based ecotourism good news for the rural poor and biodiversity conservation? A case study of Mikumi, Tanzania. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X., Walelign S.Z., Nielsen M.R., Smith-Hall C. Protected areas, household environmental incomes and well-being in the Greater Serengeti-Mara ecosystem. Forest Policy Econ. 2019;106 doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.101948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn B.P., Nyahongo J.W., Kideghesho J.R., Haaland H. Serengeti and its neighbours – do they interact? J. Nat. Conserv. 2008;16:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2008.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kegamba J.J., Sangha K.K., Wurm P., Garnett S.T. A review of conservation-related benefit-sharing mechanisms in Tanzania. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022;33 doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kicheleri R.P., Mangewa L.J., Nielsen M.R., Kajembe G.C., Treue T. Designed for accumulation by dispossession: an analysis of Tanznia's wildlife management areas through the case of Burunge. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021;3 doi: 10.1111/csp2.360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kideghesho J.R., Kimaro H.S., Mayengo G., Kisingo A.W. Will Tanzania's wildlife sector survive the COVID-19 pandemic? Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2021;14:1–18. doi: 10.1177/19400829211012682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koh L.P., Zeng Y., Sarira T.V., Siman K. Carbon prospecting in tropical forests for climate change mitigation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1271. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21560-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstanje M.E., Clayton A. Tourism and terrorism: conflicts and commonalities. Worldwide Hosp. Tour. Themes. 2012;4:8–25. doi: 10.1108/17554211211198552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuto B.K., Groves J.L. e-Review of Tourism Research (eRTR) Vol. 2. 2004. The effect of terrorism: evaluating Kenya's tourism crisis; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Leverington F., Costa K.L., Pavese H., Lisle A., Hockings M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ. Manag. 2010;46:685–698. doi: 10.1007/s00267-010-9564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey P.A., Miller J.R.B., Petracca L.S., Coad L., Dickman A.J., Fitzgerald K.H., Flyman M.V., Funston P.J., Henschel P., Kasiki S., Knights K., Loveridge A.J., MacDonald D.W., Mandisodza-Chikerema R.L., Nazerali S., Plumptre A.J., Stevens R., Van Zyl H.W., Hunter L.T.B. More than $1 billion needed annually to secure Africa's protected areas with lions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U. S. A. 2018;115:E10788–E10796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805048115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey P., Allan J., Brehony P., Dickman A., Robson A., Begg C., Bhammar H., Blanken L., Breuer T., Fitzgerald K., Flyman M., Gandiwa P., Giva N., Kaelo D., Nampindo S., Nyambe N., Steiner K., Parker A., Roe D., Thomson P., Trimble M., Caron A., Tyrrell P. Conserving Africa's wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:1300–1310. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey P., Baghai M., Bigurube G., Cunliffe S., Dickman A., Fitzgerald K., Flyman M., Gandiwa P., Kumchedwa B., Madope A., Morjan M., Parker A., Steiner K., Tumenta P., Uiseb K., Robson A. Attracting investment for Africa's protected areas by creating enabling environments for collaborative management partnerships. Biol. Conserv. 2021;255 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopa D., Mwanyoka I., Jambiya G., Massoud T., Harrison P., Ellis-Jones M., Blomley T., Leimona B., van Noordwijk M., Burgess N.D. Towards operational payments for water ecosystem services in Tanzania: a case study from the Uluguru Mountains. Oryx. 2012;46:34–44. doi: 10.1017/S0030605311001335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGinlay J., Gkoumas V., Holtvoeth J., Fuertes R.F.A., Bazhenova E., Benzoni A., Botsch K., Martel C.C., Sánchez C.C., Cervera I., Chaminade G., Doerstel J., García C.J.F., Jones A., Lammertz M., Lotman K., Odar M., Pastor T., Ritchie C., Santi S., Smolej M., Rico F.S., Waterman H., Zwijacz-Kozica T., Kontoleon A., Dimitrakopoulos P.G., Jones N. The impact of COVID-19 on the management of European protected areas and policy implications. Forests. 2020;11:1214. doi: 10.3390/f11111214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J., Robinson E., Abernethy K., Midoko Iponga D., Sackey H., Wright J.H., Milner-Gulland E.J. COVID-19, systemic crisis, and possible implications for the wild meat trade in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020;76:1045–1066. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00474-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome D. The collapse of tourism and its impact on wildlife tourism destinations. J. Tour. Futures. 2021;7:295–302. doi: 10.1108/JTF-04-2020-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD; Paris: 2020. Meeting of the OECD Councilat Ministerial Level, 28-29 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini L., Fitzsimons J.A., Cowell S., Brandon K., Wescott G. The establishment of large private nature reserves by conservation NGOs: key factors for successful implementation. Oryx. 2011;45:373–380. doi: 10.1017/S0030605310000876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson A. The Tanzanian state response to COVID-19. UNU-WIDER; Helsinki: 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riggio J., Jacobson A.P., Hijmans R.J., Caro T. How effective are the protected areas of East Africa? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019;17 doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau D., Perry B., Grimard F. The consequences of COVID-19 and other disasters for wildlife and biodiversity. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020;76:945–961. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Azofeifa G.A., Pfaff A., Robalino J.A., Boomhower J.P. Costa Rica's payment for environmental services program: intention, implementation, and impact. Conserv. Biol. 2007;21:1165–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandbrook C., Gómez-Baggethun E., Adams W. Biodiversity conservation in a post-COVID-19 economy. Oryx. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S0030605320001039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler T., Enders W. In: Terrorism, Economic Development, and Political Openness. Keefer P., Loayza N., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2008. Economic consequences of terrorism in developed and developing countries: an overview; pp. 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkady D., Neuburger L., Egger R. In: Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021. Wörndl W., Koo C., Stienmetz J.L., editors. Springer; Cham: 2021. Virtual reality as a travel substitution tool during COVID-19; pp. 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze K., Knights K., Coad L., Geldmann J., Leverington F., Eassom A., Marr M., Butchart S.H.M., Hockings M., Burgess N.D. An assessment of threats to terrestrial protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 2018;11 doi: 10.1111/conl.12435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Škare M., Soriano D.R., Porada-Rochoń M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021;163 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spergel B. Center for Conservation Finance, World Wildlife Fund; Washington DC: 2001. Raising Revenues for Protected Areas: A Menu of Options. [Google Scholar]

- Spergel B., Taïeb P. Working Group on Environmental Funds; New York: 2008. Rapid Review of Conservation Trust Funds. Prepared for the Conservation Finance Alliance (CFA) [Google Scholar]

- Steven R., Castley J.G., Buckley R. Tourism revenue as a conservation tool for threatened birds in protected areas. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone L.S., Stone M.T., Mogomotsi P.K., Mogomotsi G.I. The impacts of Covid-19 on nature-based tourism in Botswana: implications for community development. Tour. Rev. Int. 2021;25:263–278. doi: 10.3727/154427221X16098837279958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- TANAPA . Tanzania National Parks; Arusha, Tanzania: 2019. Tariffs from 1st July 2019 to 30th June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- TANAPA . TANAPA; Arusha, Tanzania: 2020. The TANAPA COVID-19 Recovery and Sustainability Plan (2020/21–2022/23) [Google Scholar]

- TANAPA . Arusha; Tanzania: 2021. Records From National Park Gates Tanzania National Parks. [Google Scholar]

- TCAA Tanzania Civil Aviation Authority: Tanzania relaxes air travel restrictions following the decrease of COVID-19 cases. 2020. https://www.tcaa.go.tz/

- Thirgood S., Mlingwa C., Gereta E., Runyoro V., Malpas R., Laurenson K., Borner M. In: Serengeti III: Human Impacts on Ecosystem Dynamics. Sinclair A.R.E., Packer C., Mduma S.A.R., Fryxell J.M., editors. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2009. Chpt 15. Who pays for conservation? Current and future financing scenarios for the Serengeti ecosystem; pp. 443–470. [Google Scholar]

- URT . Vol. 2020. The Finance Act; 2020. The United Republic of Tanzania. No. 8. Act Supplement 17th June, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk V.-A. In: Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2022. Stienmetz J.L., Ferrer-Rosell B., Massimo D., editors. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2022. Virtual reality: a simple substitute or new niche? pp. 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Watson J., Dudley N., Segan D., Hockings M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature. 2014;515:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature13947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WBG . World Bank; Washington DC: 2021. Tanzania Economic Update, July 2021, Issue 16: Transforming Tourism: Toward a Sustainable, Resilient, and Inclusive Sector. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw P.A., King B.E.M., Tolkach D. Protected areas, conservation and tourism – financing the sustainable dream. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014;22:584–603. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.873445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf I.D., Croft D.B., Green R.J. Nature conservation and nature-based tourism: a paradox? Environments. 2019;6:104. doi: 10.3390/environments6090104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder S. When payments for environmental services will work for conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2013;6:230–237. doi: 10.1111/conl.12034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder S., Engel S., Pagiola S. Taking stock: a comparative analysis of payments for environmental services programs in developed and developing countries. Ecol. Econ. 2008;65:834–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zacarias D., Loyola R. In: Ecotourism's Promise and Peril. Blumstein D., Geffroy B., Samia D., Bessa E., editors. Springer; Cham: 2017. How ecotourism affects human communities. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proportional changes in the number of international visitors (a), EAC visitors (b) and revenue (c) for the five economically most influential national parks in Tanzania. Proportional change refers to the change from 2019 to 2020. Thus, when proportions are 1.00 the values in 2019 were equal to 2020. Horizontal line below x-axis represents the period of lockdown (dashed from mid-March to mid-April, indicating suspension of European flights, and solid from mid-April to mid-May indicating suspension of all international flights).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.