Abstract

Background

Ageing traits and frailty are important health issues in modern medicine. Evidence supporting the causal effects of tobacco smoking on various ageing traits is required.

Methods

This study performed Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis instrumenting 377 genetic variants associated with being an ever‐smoker at a genome‐wide significance level to test the causal estimates from tobacco smoking. The outcome data were obtained from 337 138 white British ancestry participants from the UK Biobank. Leucocyte telomere length, appendicular lean mass index, subjective walking pace, handgrip strength, and wristband accelerometry‐determined physical activity degree were collected as ageing‐related outcomes. Summary‐level MR analysis was performed using the inverse variance‐weighted method and pleiotropy‐robust MR methods, including weighted median and MR‐Egger. Observational association between the outcome traits and phenotypically being an ever‐smoker was also investigated.

Results

Summary‐level MR analysis indicated that a higher genetic predisposition for tobacco smoking was significantly associated with shorter leucocyte telomere length (twofold increase in prevalence of smoking towards standardized Z‐score, −0.041 [−0.054, −0.028]), lower appendicular lean mass index (−0.007 [−0.010, −0.005]), slower walking pace (ordinal category, −0.047 [−0.054, −0.033]) and lower time spent on moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (hours per week, −0.39 [−0.56, −0.23]). The causal estimates were non‐significant towards handgrip strength phenotype (kg, 0.074 [−0.055, 0.204]). Pleiotropy‐robust MR results generally supported the main causal estimates. The observational findings also showed significant association between being an ever‐smoker and the ageing traits.

Conclusions

Genetically predicted and observational tobacco smoking status are significantly associated with poor ageing phenotypes. Healthcare providers may continue to reduce tobacco use, which may be helpful in reducing the burden of ageing and frailty.

Keywords: ageing, tobacco, cigarette, frailty, sarcopenia, Mendelian randomization

Introduction

The ageing epidemic is an important socio‐economic burden. 1 , 2 The global population aged ≥60 years is more than one billion, and the number is rapidly increasing. Ageing is an important health status related to frailty syndrome, 3 a state characterized by muscle loss and low physical activity. Ageing occurs differently among individuals, and those with accelerated ageing have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. 4 , 5 , 6

Tobacco smoking is another important global health problem that increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, malignancy and death. 7 The causal linkage between tobacco smoking and ageing traits needs further study. Tobacco exposure causes cellular senescence, 8 and it is assumed that biological ageing is accelerated by tobacco use. Despite some observational studies supporting the association, 9 the direct causal effect is difficult to reveal by conventional study design because of complex confounding and reverse causal effects. 10 A higher level of evidence suggesting the causal effect would be important, as it would firmly support that social interventions to reduce tobacco use would be helpful in reducing the rapidly increasing burden of ageing.

In recent biobank databases (e.g. UK Biobank), ageing‐related traits including leucocyte telomere length (indicator for biologic ageing), sarcopenia phenotypes (appendicular lean mass index, walking pace and handgrip strength) and objectively measured physical activity traits are available in the population scale. 11 The availability of large‐scale ageing traits with associated genotypes has enabled various studies to evaluate the risk factors and outcomes related to ageing. Particularly, genetic epidemiological analysis and Mendelian randomization (MR) have been widely performed. MR utilizes a genetic instrumental variable, which is minimally biased by confounding effects or reverse causation, as it is fixed before birth, to demonstrate causal estimate. 10 MR analysis has also been performed in studies related to ageing phenotypes, and the method would be a useful tool to investigate the causal effects of tobacco smoking on ageing. 12 , 13 , 14

In this study, we hypothesized that tobacco smoking has causal effects on various ageing traits. We performed MR analysis in the UK Biobank, implementing genetic instruments developed from a large‐scale genome‐wide association study (GWAS) meta‐analysis of tobacco smoking phenotypes. We found that tobacco smoking may accelerate biological ageing, physical inactivity and sarcopenia.

Methods

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (No. E‐2203‐053‐1303) and the UK Biobank Consortium (application no. 53799). 11 , 15 The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the attending institutional review board because this study investigated an anonymous public database without medical intervention.

Genetic instruments for tobacco smoking

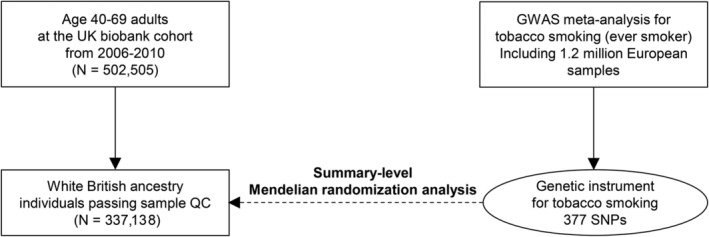

We used the genetic variants for tobacco smoking from one of the largest GWAS meta‐analysis on 1.2 million European ancestry individuals, including more than half a million ever‐smokers (Figure 1 ). 16 There were 29 studies included in the meta‐analysis, and the 23andMe, UK Biobank, deCODE and HUNT were representative studies that provided a relatively large number of samples. The 378‐lead single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with the phenotype of being a regular smoker (smoking initiation) with a conditionally genome‐wide significant association were selected as genetic instruments for tobacco smoking (Table S1 ).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. GWAS, genome‐wide association study; QC, quality control; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Genetic instruments for MR analysis should meet three core assumptions to demonstrate causal estimates. 10 First, the relevance assumption is that the instruments should be closely associated with the exposure phenotype, and this was considered attained as the SNPs were identified from the large‐scale GWAS meta‐analysis. Genome‐wide significant SNPs explained 2% of the variance for smoking initiation, providing sufficient power for MR analysis considering the size of the outcome dataset. 16 Second, the independence assumption is that the instruments should not be associated with confounding phenotypes. We used pleiotropy‐robust MR analysis methods (MR‐Egger, weighted median), which relax the assumption that causal estimates are not affected by such pleiotropy. 17 , 18 The MR‐Egger intercept P value was calculated to test the likelihood of the presence of directional pleiotropy. Furthermore, we performed sensitivity analysis with additional exclusion for SNPs that were significantly associated with other phenotypes in the GWAS catalogue, in which the search was already performed in the previous GWAS meta‐analysis. 16 , 19 Third, the exclusion‐restriction assumption is that the causal pathway should be through the exposure of interest. We used the weighted median method, which relaxes the assumption for up to half of the instrumented genetic weights. 18 In addition, a direct effect from an SNP towards an outcome phenotype would invalidate the assumption, so we disregarded SNPs with direct genome‐wide significant association (P < 5E‐8) with an outcome phenotype when performing the analysis.

UK Biobank outcome data

UK Biobank data are a prospective cohort study on approximately 500 000 individuals aged 40–69 years at baseline. 11 , 15 The database includes deep phenotyping and genotyping information for the samples and has been widely used in modern medical research. Because of the large sample size, availability of diverse phenotypes and large‐scale genotype data, UK Biobank data have been used in various MR studies. 12 , 13 , 14 , 20

We used data from white British ancestry samples from the UK Biobank data, as ethnic‐specific analysis is important for MR analysis, and the genetic instruments were developed from a European ancestry population. 19 , 20 After disregarding those with excess kinship, sex chromosomal aneuploidy or outliers regarding heterogeneity or missing rate, a total of 337 138 white British ancestry individuals were included in the analysis.

Outcome ageing traits

We collected data on diverse traits related to ageing and frailty. (i) First, leucocyte telomere length was collected. 13 The phenotype was used to reflect proxies of biological ageing, as those with accelerated ageing exhibit shortening of telomeres. Log‐transformed and standardized Z‐scores for leucocyte telomere length were collected from 326 075 samples. (ii) Second, we collected an objective parameter for muscle mass loss, the appendicular lean mass adjusted for body mass index (appendicular lean mass/body mass index), measured by a BC418MA body composition analyser (Tanita, Tokyo, Japan) and available in 329 903 samples. 12 , 21 (iii) Third, we collected functional parameters for sarcopenia, including walking pace, self‐reported as slow, average or brisk category and handgrip strength, measured isometrically using a Jamar J00105 hydraulic hand dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument Company, IN, USA). 12 The information for walking pace was collected from the electronic questionnaire asking ‘How would you describe your usual walking pace?’ and was available in 335 288 samples. The handgrip strength, which was available in 335 061 samples, was measured once for each hand, and the average value was used in the analysis. 12 (iv) Lastly, the objective data for physical activity were included, which were collected from wristband accelerometry. 22 We used the time for physical activity with moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity (activity as >100 milligravities in intensity), and the data were available in 71 433 samples. 14

To calculate the association between genetic instruments and outcome phenotype, linear regression analysis was performed for SNPs using PLINK 2.0, and the genetic effect sizes were adjusted for age, sex, age × sex, age2 and 10 genetic principal components. 23

Summary‐level MR analysis

The multiplicative random‐effects inverse variance‐weighted method was the main MR analysis, following the current guidelines. The method allows balanced pleiotropic effects of the utilized variants. 19 , 24 Next, the weighted median method, which relaxes the MR assumptions for up to half of instruments, was used. 18 MR‐Egger regression with bootstrapped standard error was performed. 17 MR‐Egger regression is a method that provides pleiotropy‐robust causal estimates under the attainment of the InSIDE assumption. Another strength of the method is that the MR‐Egger intercept P value can be calculated, which is a measure to assess the presence of directional pleiotropy. If the intercept was significantly non‐zero (P < 0.05), directional pleiotropy was suspected. However, MR‐Egger regression has a weak statistical power compared with other MR methods. The summary‐level MR analysis was performed using the ‘TwoSampleMR’ package in R (version 0.4.26). 25 As we are performing analysis towards five outcome traits, Bonferroni‐adjusted two‐sided P value <0.05/5 by the inverse variance‐weighted method was used to indicate statistical significance. The causal estimates were scaled to the effects of a twofold increase in the prevalence of smoking by multiplying 0.693 with the raw causal estimates. 26

Power calculation for MR analysis

Post hoc power calculations for MR analysis are available online (https://sb452.shinyapps.io/power/). We followed the method suggested by Burgess et al. (http://mendelianrandomization.com/) to calculate the power in genetically predicting binary exposure. 26 , 27 We calculated beta2 × 2 × MAF × (1 − MAF), where MAF indicates the minor allele frequency of each genetic instrument, and the sum of the values was the coefficient of determination of exposure. Despite this limitation, this approach of using odds ratios as a proxy for prevalence ratio was necessary, as genetic beta effect sizes were not scaled to prevalence increase of a unit of an exposure in GWAS. The effect sizes of causal estimates by the inverse variance‐weighted method towards outcome traits were used as the effect size of the causal effect to calculate the statistical power of the MR analysis.

Observational association

We additionally investigated the observational association between being an ever smoker (including phenotype of ex‐smoker and current‐smoker) and the ageing traits. As the observational association is more prone to be affected by confounding effects than MR results, we first tested the age–sex adjusted linear regression results. Then, an additional multivariable model was constructed including the major clinical covariates (e.g. history of medication for hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus).

Results

Characteristics of the outcome data

The final study sample included as the outcome data for the MR analysis had a median age of 58 years (interquartile range, 51–63 years) (Table 1 ). Male sex was identified in 46.3% of patients, and the median body mass index was 26.7 (interquartile range, 24.1–29.9) kg/m2. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 4.8%, and 20.9% and 17.5% of the participants were using medications for hypertension and dyslipidaemia, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary‐level MR results

| Variables | Study sample(N = 337 138) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 [51;63] |

| Sex | |

| Female | 181 027 (53.7%) |

| Male | 156 111 (46.3%) |

| Hypertension medication users | 70 021 (20.9%) |

| Dyslipidaemia medication users | 58 533 (17.5%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 179 (4.8%) |

| Systolic BP | 136.5 [125.0;149.5] |

| Diastolic BP | 82.0 [75.5;89.0] |

| Hb A1c (mmol/L) | 35.1 [32.7;37.7] |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.72 [24.13;29.85] |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90 [80;99] |

| Smoking history | |

| Non‐smoker | 183 640 (54.7%) |

| Ex‐smoker | 118 403 (35.24%) |

| Current‐smoker | 33 922 (10.1%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Telomere (standardized Z‐score) | ‐0.03 [−0.67;0.61] |

| Appendicular lean mass index | 0.85 [0.72;1.02] |

| Handgrip strength (average of measurements for each hand) | 29.00 [22.50;39.00] |

| Walking pace | |

| Slow | 25 105 (7.5%) |

| Average | 175 921 (52.5%) |

| Brisk | 134 262 (40.0%) |

| Accelerometry‐determined moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (hours/week) | 11.09 [7.56;14.95] |

Categorical variables are presented as N (%), and continuous variables as medians (interquartile ranges).

The median appendicular lean mass index was 0.85 (interquartile range, 0.72–1.02), and the handgrip strength was 29.0 (interquartile range, 22.5–39.0) kg. There was 40.0% of individuals who reported a brisk walking pace, whereas 52.5% reported an average walking pace, and 7.5% reported a slow walking pace. The median time for moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity, measured by wristband accelerometry, was 11.09 (interquartile range, 7.56–14.95) hours per week.

Genetic instruments

A total of 377/378 SNPs were identified in the UK Biobank data (Table S1 ). Those without genome‐wide significant associations with an outcome trait were included as genetic instruments in the analysis. There were 14 SNPs with genome‐wide significant associations with other phenotypes, such as educational attainment, inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy and body mass index, which were identified from the GWAS catalogue. The SNPs were disregarded in the additional sensitivity analysis.

Summary‐level MR analysis results

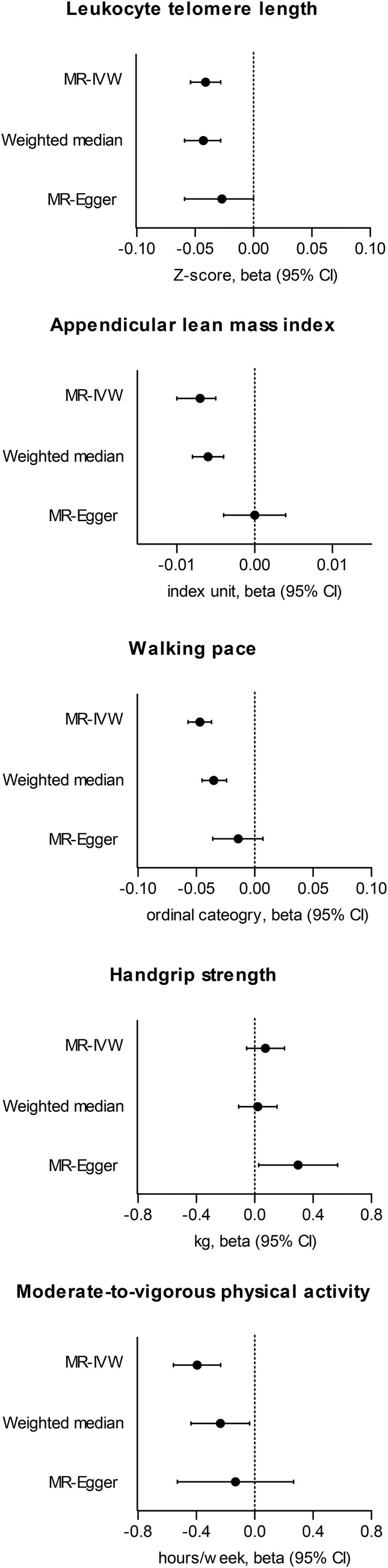

Genetically predicted smoking initiation was significantly associated with shorter telomere length (−0.041[−0.051, 0.031], P < 0.001) (Figure 2 and Table 2 ). The results remained significant by the MR‐Egger regression with bootstrapped standard error (−0.027 [−0.059, 0.000], P = 0.048) and weighted median method (−0.043[−0.059, −0.028], P < 0.001). Additionally, the MR‐Egger regression intercept P value indicated a non‐significant pleiotropic effect (P = 0.65), supporting the main causal estimates. The results were similar, even after disregarding the SNPs reported to be associated with other traits (Table S2 ).

Figure 2.

Causal estimates from the Mendelian randomization analysis. The x‐axis shows causal estimates (beta and 95% confidence inter. The multiplicative random‐effect inverse variance‐weighted method (MR‐IVW), weighted median and MR‐Egger regression with bootstrapped standard errors are presented. The outcome phenotypes were leucocyte telomere length (log‐transformed, standardized to Z‐score), appendicular lean mass index (appendicular lean mass/body mass index), walking pace (self‐reported ordinal category, slow, average and brisk), handgrip strength (kg, average from two measurements from each hand) and wristband accelerometer defined time for moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity. Causal estimates were scaled towards a twofold increase in the prevalence of tobacco smoking.

Table 2.

Causal estimates by summary‐level MR analysis

| Outcome | N of instrumented SNPs | MR‐Egger intercept P value | MR methods | Causal estimates [beta (95% CI)] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leucocyte telomere length (Z‐score) | 377 | 0.654 | MR‐IVW | −0.041 (−0.054, −0.028) | < 0.001 |

| Weighted median | −0.043 (−0.059, −0.028) | < 0.001 | |||

| MR‐Egger | −0.027 (−0.059, 0.000) | 0.048 | |||

| Appendicular lean mass index | 353 | 0.306 | MR‐IVW | −0.007 (−0.01, −0.005) | < 0.001 |

| Weighted median | −0.006 (−0.008, −0.004) | < 0.001 | |||

| MR‐Egger | 0 (−0.004, 0.004) | 0.48 | |||

| Walking pace (ordinal category) | 375 | 0.257 | MR‐IVW | −0.047 (−0.057, −0.037) | < 0.001 |

| Weighted median | −0.035 (−0.045, −0.024) | < 0.001 | |||

| MR‐Egger | −0.014 (−0.036, 0.007) | 0.01 | |||

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 376 | 0.557 | MR‐IVW | 0.074 (−0.055, 0.204) | 0.26 |

| Weighted median | 0.022 (−0.11, 0.153) | 0.75 | |||

| MR‐Egger | 0.298 (0.028, 0.568) | 0.02 | |||

| Time on moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (hours/week) | 377 | 0.666 | MR‐IVW | −0.394 (−0.556, −0.233) | < 0.001 |

| Weighted median | −0.235 (−0.437, −0.034) | 0.02 | |||

| MR‐Egger | −0.131 (−0.529, 0.267) | 0.26 |

MR, Mendelian randomization; MR‐IVW, multiplicative random‐effect inverse variance‐weighted method; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Causal estimates are scaled towards twofold increase in prevalence of tobacco smoking.

Genetically predicted being a regular smoker was also significantly associated with lower appendicular lean mass index (−0.007 [−0.010, −0.005], P < 0.001). Again, the results remained significant using the weighted median method (−0.006 [−0.008, −0.004], P < 0.001). Although the MR‐Egger regression intercept was approximately zero (P = 0.31), the causal estimates by MR‐Egger regression were attenuated (0.000 [−0.004, 0.004], P = 0.48). However, the main causal estimate remained significant in the sensitivity analysis, disregarding the SNPs associated with potential confounders.

The causal estimates of walking pace indicated that a higher genetic liability for being a smoker was significantly associated with having a slower walking pace category (−0.047 [−0.057, −0.037], P < 0.001). The results were similar to those of the weighted median methods (−0.035 [−0.045, −0.024], P < 0.001) and marginal for MR‐Egger regression (−0.014 [−0.036, 0.007], P = 0.10). The MR‐Egger regression intercept P value indicated a low probability of directional pleiotropy (P = 0.26), and the results remained similar in the sensitivity analysis with fewer instrumented SNPs. However, the main causal estimate from genetically predicted tobacco smoking towards handgrip strength was non‐significant (0.074 [−0.055, 0.204], P = 0.26).

The summary‐level MR analysis demonstrated that genetically predicted tobacco smoking was significantly associated with less time spent on moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (−0.394 [−0.556,‐0.233], P < 0.001). Although the results of the weighted median method (−0.235 [−0.437, −0.034], P = 0.02) and the MR‐Egger regression were marginal (−0.131 [−0.529, 0.267], P = 0.26), the direction of the effect size was the same as the main estimate, and the MR‐Egger intercept P value was non‐significant (P = 0.67), indicating that the main estimate was less likely to be affected by directional pleiotropy.

Post hoc power calculation results for MR analysis

The calculated coefficient for determination was 0.055, except for analysis with the appendicular lean mass index outcome, which yielded a coefficient of 0.051, as a large number of SNPs were disregarded due to their genome‐wide significant association with the outcome itself (Table 3 ). The post hoc power towards the outcome phenotypes was sufficient for telomere length (99.8%), appendicular lean mass (100%), walking pace (100%) and accelerometer‐defined moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (100%). However, the relative effect sizes of the main causal estimate for handgrip strength considering the standard deviation were relatively small compared with others, and the power was limited (10.5%) in the analysis with handgrip strength outcome.

Table 3.

Post hoc power calculation for MR analysis

| Outcome trait | Outcome sample size | N of instrumented SNPs | Coefficient of determination a | Causal estimate effect size (standard deviation change) b | Power (%) c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telomere length | 326 075 | 377 | 0.055 | 0.041 | 99.8 |

| Appendicular lean mass index | 329 903 | 353 | 0.051 | 0.059 | 100 |

| Walking pace | 335 288 | 375 | 0.055 | 0.111 | 100 |

| Handgrip strength | 335 061 | 376 | 0.055 | 0.010 | 10.5 |

| Time for moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity | 71 443 | 377 | 0.055 | 0.097 | 100 |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Coefficient of determination was calculated by summing the beta2 × 2 × MAF × (1 − MAF), where MAF indicates the minor allele frequency of each genetic instrument. The coefficient is a proxy value, as the current MR analysis tested binary tobacco smoking exposure, different from a conventional analysis testing the effects of continuous exposure.

Standardized causal estimate effect sizes were derived from the main causal estimates using the inverse variance‐weighted method, divided by the standard deviation of the outcome phenotype.

Statistical power was calculated using an online power calculator (https://sb452.shinyapps.io/power/), and we followed the method suggested by Burgess et al. (http://mendelianrandomization.com/) to calculate the power in MR analysis with binary exposure.

Observational findings

In the UK Biobank data, the observational analysis provided similar findings as our MR study, as leucocyte telomere length, appendicular lean mass index, walking pace and time on moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity traits were all significantly lower in those with an ever‐smoking history. But the handgrip strength was non‐significantly associated with smoking exposure in the age–sex adjusted model (Table 4 ). The results were similar when we additionally adjusted major co‐morbidities, although handgrip strength was inversely associated with the smoking exposure.

Table 4.

Observational association between being an ever‐smoker and ageing‐related traits

| Outcome trait | Age–sex adjusted model | Multivariable model adjusted for co‐morbidities a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (95% CI) | P | Beta (95% CI) | P | |

| Leucocyte telomere length (Z‐score) | −0.049 (−0.052, −0.043) | <0.001 | −0.046 (−0.052, −0.040) | <0.001 |

| Appendicular lean mass index | −0.010 (−0.011, −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.008 (−0.009, −0.007) | <0.001 |

| Walking pace (ordinal category) | −0.087 (−0.091, −0.083) | <0.001 | −0.074 (−0.078, −0.070) | <0.001 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 0.025 (−0.024, 0.074) | 0.33 | 0.098 (0.049, 0.147) | <0.001 |

| Time on moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (hours/week) | −0.291 (−0.375, −0.207) | <0.001 | −0.209 (−0.293, −0.125) | <0.001 |

N of individuals with the available complete information for the smoking status, covariates and the outcome traits were 324 947/322 438, 329 903/327 090, 334 152/321 298, 333 906/331 022 and 72 461/71 937 for telomere length, appendicular lean mass index, walking pace, handgrip strength and time for moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity, respectively, in the age–sex adjusted model/multivariable model adjusted for co‐morbidities.

The exposure of the analysis was being an ever‐smoker, including phenotypical ex‐smoker and current smoking status.

The multivariable model was adjusted for age, sex, history of medications for hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

In this study, we found that genetically predicted and observational tobacco smoking was significantly associated with shorter leucocyte telomere length, lower appendicular lean mass index, slower walking pace and lower physical activity. We considered important aspects of MR analysis to demonstrate causal estimates, and the results supported that tobacco smoking may be a causal risk factor for ageing traits. This study highlights that reducing tobacco use may be helpful in reducing the rapidly increasing burden of the ageing epidemic in modern medicine.

Ageing traits are important medical dimensions related to various complications (e.g. cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome) and mortality. 4 , 5 The velocity of ageing differs among individuals, and those with accelerated ageing have adverse outcomes related to frailty. Conversely, the causal effect of tobacco smoking, a harmful lifestyle behaviour with increasing global awareness, 7 on ageing traits has been yet determined in a population scale despite the numerous evidence that tobacco exposure accelerates cellular senescence. 8 As the association between tobacco smoking and ageing traits occurring in the later period of life is confounded by many related traits, conventional observational study may have difficulty revealing the causal linkage because of the confounding effects and issue related to reverse causation. 10 A previous MR study investigating the adverse effects from tobacco smoking reported null finding towards telomere length shortening. 28 An additional study with robust genetic instruments and a larger‐scale outcome data, ensuring the statistical power, was warranted. In this study, we showed that genetic predisposition to tobacco smoking is significantly associated with adverse ageing traits by implementing genetic variants reported from a recent large‐scale GWAS meta‐analysis. The main strength of this study is that we assessed certain dimensions of ageing and frailty. Based on our results, medical societies should pay attention to preventing tobacco use in the general population to reduce the socio‐economic burden of ageing traits.

Various experimental studies have established that tobacco smoking causes cellular senescence in organs where direct exposure occurs (e.g. lung). 29 Tobacco smoking has been reported to be a risk factor for skeletal muscle dysfunction, not only in patients with lung disease but also in the general population. 30 , 31 , 32 Smoking directly induces skeletal muscle dysfunction by impaired oxygen deliveries to the mitochondria, in which the chronic condition may lead to muscle atrophy and sarcopenia. In our study, both genetically predicted and observational tobacco smoking status were significantly associated with both the objective and functional dimensions of sarcopenia and physical activity, suggesting that the effect would be generally present by tobacco use in the general population. Our study suggests that a direct effect on cellular senescence, indicated by telomere length attrition, may also contribute to ageing. Future studies may consider testing the effects of reducing or stopping tobacco use on ageing or frailty, further supporting the efforts to educate smokers, even those who already have smoking histories. Furthermore, additional investigation of the mechanisms of the effects of tobacco components on cellular senescence may reveal future directions to reverse this effect.

This study had certain limitations. First, the significance of the causal estimates by MR‐Egger regression is controversial. 19 Some may advocate that the causal estimates by MR‐Egger regression are supportive of the main estimates as the directions were generally consistent and the MR‐Egger intercept indicated a low probability of directional pleiotropy. 33 However, as tobacco smoking is a complex social behaviour, the possibility of a pleiotropic pathway may still need to be considered. Second, there was a certain sample overlap in the two‐sample MR, as the GWAS meta‐analysis for tobacco smoking included the UK Biobank data. If instrumental power is weak, this may cause bias in the causal estimates 34 ; however, considering that most analyses were performed with sufficient power, such an issue may not be substantial. Third, the statistical power of MR for handgrip strength was not secured. However, the main reason may be that the actual effect size of the causal estimate is small, leaving handgrip strength to have a lower priority outcome in consideration of the causal effects of tobacco smoking. Lastly, performing MR analysis with binary exposure tests the association between genetic liability and outcomes. 26 However, utilizing quantitative traits (e.g. smoking heaviness) as exposure phenotypes was not possible for tobacco smoking, as testing the causal estimates only in a subgroup (e.g. smokers) causes collider bias. 35

In conclusion, tobacco smoking may be a causal factor for telomere shortening, loss of muscle mass, slow gait speed and physical inactivity. Healthcare providers should consider the harmful effects of tobacco smoking, particularly those affecting various dimensions of ageing traits.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Information of genetic instruments and their association with outcome phenotypes.

Table S2. Causal estimates by summary‐level MR analysis after disregarding SNPs associated with other phenotypes by the GWAS catalogue screening.

Acknowledgements

This study was based on data provided by the UK Biobank Consortium (application no. 53799). We thank the investigators of the CKDGen consortium, who provided summary statistics for the outcome data of this study. This research was supported by a grant from the MD‐Phd/Medical Scientist Training Program through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea. This study was supported by the Young Investigator Research Grant from the Korean Nephrology Research Foundation 2022. This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT, Ministry of Science and ICT) (2021R1A2C2094586). This study was funded by a research fund from Seoul National University Hospital (3020220160). The authors independently performed this study.

This manuscript certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 36

Park S., Kim S. G., Lee S., Kim Y., Cho S., Kim K., Kim Y. C., Han S. S., Lee H., Lee J. P., Joo K. W., Lim C. S., Kim Y. S., and Kim D. K. (2023) Causal linkage of tobacco smoking with ageing: Mendelian randomization analysis towards telomere attrition and sarcopenia, Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 14, 955–963, 10.1002/jcsm.13174

References

- 1. Partridge L, Deelen J, Slagboom PE. Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature 2018;561:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel JP, et al. The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016;387:2145–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cruz‐Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 2011;305:50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leong DP, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Lopez‐Jaramillo P, Avezum A Jr, Orlandini A, et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet 2015;386:266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Q, Zhan Y, Pedersen NL, Fang F, Hägg S. Telomere length and all‐cause mortality: a meta‐analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2018;48:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ghebreyesus TA. Progress in beating the tobacco epidemic. Lancet 2019;394:548–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nyunoya T, Monick MM, Klingelhutz A, Yarovinsky TO, Cagley JR, Hunninghake GW. Cigarette smoke induces cellular senescence. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:681–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Astuti Y, Wardhana A, Watkins J, Wulaningsih W. Cigarette smoking and telomere length: a systematic review of 84 studies and meta‐analysis. Environ Res 2017;158:480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey SG. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 2018;362:k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 2018;562:203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park S, Lee S, Kim Y, Lee Y, Kang MW, Kim K, et al. Relation of poor handgrip strength or slow walking pace to risk of myocardial infarction and fatality. Am J Cardiol 2022;162:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park S, Lee S, Kim Y, Cho S, Kim K, Kim YC, et al. A Mendelian randomization study found causal linkage between telomere attrition and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2021;100:1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park S, Lee S, Kim Y, Lee Y, Kang MW, Kim K, et al. Causal effects of physical activity or sedentary behaviors on kidney function: an integrated population‐scale observational analysis and Mendelian randomization study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022;37:1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet 2019;51:237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:512–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol 2016;40:304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgess S, Davey Smith G, Davies NM, Dudbridge F, Gill D, Glymour MM, et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations. Wellcome Open Res 2019;4:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park S, Lee S, Kim Y, Lee Y, Kang MW, Kim K, et al. Atrial fibrillation and kidney function: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2816–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, Cawthon PM, McLean RR, Harris TB, et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doherty A, Jackson D, Hammerla N, Plötz T, Olivier P, Granat MH, et al. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: the UK Biobank study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second‐generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 2015;4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomisation (STROBE‐MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2021;375:n2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR‐Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 2018;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burgess S, Labrecque JA. Mendelian randomization with a binary exposure variable: interpretation and presentation of causal estimates. Eur J Epidemiol 2018;33:947–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zeng H, Ge J, Xu W, Ma H, Chen L, Xia M, et al. Type 2 diabetes is causally associated with reduced serum osteocalcin: a genomewide association and Mendelian randomization study. J Bone Miner Res 2021;36:1694–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rode L, Bojesen SE, Weischer M, Nordestgaard BG. High tobacco consumption is causally associated with increased all‐cause mortality in a general population sample of 55,568 individuals, but not with short telomeres: a Mendelian randomization study. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1473–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. University of Essex . In Service UD , ed. Understanding society: waves 1–6, 2009–2015, 8th ed; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chan SMH, Cerni C, Passey S, Seow HJ, Bernardo I, van der Poel C, et al. Cigarette smoking exacerbates skeletal muscle injury without compromising its regenerative capacity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2020;62:217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castillo EM, Goodman‐Gruen D, Kritz‐Silverstein D, Morton DJ, Wingard DL, Barrett‐Connor E. Sarcopenia in elderly men and women: the Rancho Bernardo study. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Locquet M, Bruyère O, Lengelé L, Reginster JY, Beaudart C. Relationship between smoking and the incidence of sarcopenia: the SarcoPhAge cohort. Public Health 2021;193:101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR‐Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burgess S, Davies NM, Thompson SG. Bias due to participant overlap in two‐sample Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol 2016;40:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gkatzionis A, Burgess S. Contextualizing selection bias in Mendelian randomization: how bad is it likely to be? Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:691–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. von Haehling S, Morley JE, Coats AJS, Anker SD. Ethical guidelines for publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle: update 2021. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021;12:2259–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Information of genetic instruments and their association with outcome phenotypes.

Table S2. Causal estimates by summary‐level MR analysis after disregarding SNPs associated with other phenotypes by the GWAS catalogue screening.