Abstract

Background

Increasing evidence shows that tRNA‐derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) are not only by‐products of transfer RNAs, but they participate in numerous cellular metabolic processes. However, the role of tsRNAs in skeletal muscle regeneration remains unknown.

Methods

Small RNA sequencing revealed the relationship between tsRNAs and skeletal muscle injury. The dynamic expression level of 5'tiRNA‐Gly after muscle injury was confirmed by real‐time quantitative PCR (q‐PCR). In addition, q‐PCR, flow cytometry, the 5‐ethynyl‐2'‐deoxyuridine (Edu), cell counting kit‐8, western blotting and immunofluorescence were used to explore the biological function of 5'tiRNA‐Gly. Bioinformatics analysis and dual‐luciferase reporter assay were used to further explore the mechanism of action under the biological function of 5'tiRNA‐Gly.

Results

Transcriptome analysis revealed that tsRNAs were significantly enriched during inflammatory response immediately after muscle injury. Interestingly, we found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly was significantly up‐regulated after muscle injury (P < 0.0001) and had a strong positive correlation with inflammation in vivo. In vitro experiments showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL‐1β, P = 0.0468; IL‐6, P = 0.0369) and the macrophages of M1 markers (TNF‐α, P = 0.0102; CD80, P = 0.0056; MCP‐1, P = 0.0002). On the contrary, 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited the mRNA expression of anti‐inflammatory cytokines (IL‐4, P = 0.0009; IL‐10, P = 0.0007; IL‐13, P = 0.0008) and the mRNA expression of M2 markers (TGF‐β1, P = 0.0016; ARG1, P = 0.0083). Flow cytometry showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the percentage of CD86+ macrophages (16%, P = 0.011) but inhibited that of CD206+ macrophages (10.5%, P = 0.012). Immunofluorescence showed that knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly increased the infiltration of M2 macrophages to the skeletal muscles (13.9%, P = 0.0023) and inhibited the expression of Pax7 (P = 0.0089) in vivo. 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted myoblast the expression of myogenic differentiation marker genes (MyoD, P = 0.0002; MyoG, P = 0.0037) and myotube formation (21.3%, P = 0.0016) but inhibited the positive rate of Edu (27.7%, P = 0.0001), cell viability (22.6%, P = 0.003) and the number of myoblasts in the G2 phase (26.3%, P = 0.0016) in vitro. Mechanistically, we found that the Tgfbr1 gene is a direct target of 5'tiRNA‐Gly mediated by AGO1 and AGO3. 5'tiRNA‐Gly dysregulated the expression of downstream genes related to inflammatory response, activation of satellite cells and differentiation of myoblasts through the TGF‐β signalling pathway by targeting Tgfbr1.

Conclusions

These results reveal that 5'tiRNA‐Gly potentially regulated skeletal muscle regeneration by inducing inflammation via the TGF‐β signalling pathway. The findings of this study uncover a new potential target for skeletal muscle regeneration treatment.

Keywords: inflammation, skeletal muscle regeneration, Tgfbr1, TGF‐β signalling pathway, tsRNAs

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is the most abundant tissue of the human body, comprising approximately 40% of the body mass. 1 Skeletal muscle is critical in various functions, including movement, breathing and postural maintenance. 2 The importance of skeletal muscle becomes apparent upon impairment of its functions following injury. Skeletal muscle injury can result from mechanical trauma, heat stress, myotoxic factors, ischaemia, nerve damage and other conditions. 3 Fortunately, skeletal muscle can repair itself through complex cellular responses, which involve the formation of new myofiber, restoration of muscle function and recovery of muscle metabolism. 3 Skeletal muscle regeneration involves distinct cellular behaviours and regulatory networks at each repair process. Briefly, myofibers first undergo degeneration, accompanied by infiltration of inflammatory cells. Proinflammatory immune cells then switch to anti‐inflammatory immune cells, providing critical microenvironments for the proliferation and differentiation of muscle satellite cells. 4 Recent findings indicate that various inflammatory and immune cells play central roles in almost all stages of muscle regeneration. 5 Upon muscle tissue injury, early hematoma releases signalling molecules cause dilatation and increased permeability of blood vessels. 6 Circulating inflammatory and immune cells from the periphery are then recruited to the necrotic or damaged areas. M1 macrophages and T cells maintain a proinflammatory environment to declutter the site of injury and play important roles in removing muscle debris and activating muscle stem cells. 7 , 8 This is necessary to make room for the corresponding anabolic anti‐inflammatory progression. The anti‐inflammatory environment is dominated by M2 macrophages, which create an environment that stops inflammation and eventual tissue regeneration. 9 In addition, M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) promote the differentiation of satellite cells and maturation of the newly formed myofibers. 10 Cytokines produced during the inflammatory response determine cell fate and, thus, the direction of the healing process, which might be muscle regeneration or fibrosis. 11 In general, inflammatory response is the first response after muscle injury and is key to the repair process. Therefore, uncovering the mechanisms underlying the inflammation response after muscle injury can reveal new potential targets for treating muscle injuries and disorders.

Non‐coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are indispensable regulatory factors in various biological processes, and many studies have found that they play an important role in muscle regeneration. For example, miR‐29 modulates the transcription of mRNAs for Rybp and Yy1 genes, promoting Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) muscle regeneration. 12 , 13 circMYBPC1 stimulates skeletal muscle regeneration after muscle by directly binding MyHC. 14 lncRNA MAR1 regulates the expression of Wnt5a protein by sponging miR‐487b, promoting muscle differentiation and regeneration. 15 To date, numerous ncRNAs derived from transfer RNAs (tRNAs) have been discovered. ncRNAs are tRNA‐derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) that regulate numerous biological processes. 16 tsRNAs are potential therapeutic targets for caloric restriction (CR) pre‐pretreatment to improve myocardial ischaemic injury. 17 Regulation of 3'‐tRF‐ProTGG‐19 in salt‐induced hypertensive rats and human hypertensive renal sclerosis has also been confirmed. 18 The mesenchymal stem cell exosome tsRNA‐21109 alleviates systemic lupus erythematosus by inhibiting macrophage M1 polarization. 19 Studies have also shown that hypoxia induces the expression of Dicer1 in colorectal cancer (CRC) cells. Dicer1 increases the expression of tRF‐20‐MEJB5Y13 under hypoxia, which promotes the invasion and migration of CRC cells. 20 Recent research has revealed a novel tRNA pathway that participates in the innate immune response by assigning ‘immune activation’ to 5'‐tRNA half molecules of tRNAHisGUG. 21 However, to date, the role of tsRNAs in muscle regeneration has not been reported.

Numerous studies have shown that tsRNAs participate in various cellular responses, such as hypoxia, 22 viral infection 23 and inflammation. 19 Macrophage infiltration and inflammation are the initial stages of muscle injury and an essential part of muscle regeneration. Promoting early inflammatory response can accelerate muscle repair. 24 We speculated that tsRNAs play an important role in cellular stress inflammatory response in the early stage of muscle repair. Therefore, for the first time, we report the expression pattern of tsRNAs induced by inflammation in the early stage of muscle repair. Data were analysed using tsRNAs transcriptome sequencing. The molecular mechanism through which tsRNAs regulate inflammatory cells' polarization is also discussed. The findings of this study provide a new research direction for the genetic regulation of muscle regeneration.

Materials and methods

An extended materials and methods section can be found in the supporting information.

Construction of the cardiotoxin skeletal muscle injury model and knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in vivo

The in vivo studies were performed using 8‐week‐old male C57BL/6J mice (Dossy, China). The right tibialis anterior (TA) muscle was injured through intramuscular injection of 50 μL of 10 μΜ cardiotoxin (CTX) (Sigma‐Aldrich, USA), whereas the contralateral control side was treated with 50 μL of PBS. The anterior tibialis muscle was sampled on Days 3, 7, 14 and 21 after CTX treatment. Antagomir was used to knock down the expression of 5'‐tiRNA‐Gly‐CCC (5'tiRNA‐Gly) in vivo. At 12 h after CTX muscle injury, 40 μL of 10 nM of antagomir‐5'tiRNA‐Gly was injected into the TA muscle of mice. The sequences for the oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1 . The protocols and procedures for animal experiments were approved by the Research and Animal Ethics Committees of Sichuan Agricultural University (Sichuan, China; No. DKY‐B20131403).

Cell culture

C2C12 cells, RAW264.7 cells and 293T cells were purchased from NICR (Beijing, China). C2C12 cells were cultured in a growth medium (GM) supplemented with DMEM/F12 medium (Hyclone, USA), 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco, USA). The differentiation medium (DM) comprised DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 2% horse serum. RAW264.7 and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco). All cells were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation assay

The 5‐ethynyl‐2'‐deoxyuridine (Edu) kit and the cell counting kit‐8 (CCK‐8) were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). C2C12 cells were cultured in a GM supplemented with DMEM/F12 medium (Hyclone), 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) and seeded in 96‐well plates at the rate of 30%. Edu assay was performed 24 h after cell transfection. CCK‐8 assay was performed at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h after transfection. Cell proliferation assays were performed separately using the two experimental methods according to the manufacturer's instructions.

tRF and tiRNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using the RNAiso reagent (Takara, Japan) and pretreated using RNA Pretreatment (Arraystar, USA) to remove modification, including 3'‐aminoacyl, 2',3'‐cyclic phosphate, 5'‐OH, m1A and m3C. cDNA was synthesized and amplified using RT and amplification primers. The target fragment of 135–160 bp (corresponding to the small RNA size of 15–40 nt) was extracted and purified on PAGE gel. The quantity measurement of the completed library was performed using the 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA). Sequencing was performed using the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina, USA). Sequencing data were uploaded to the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database, ID: CRA007436.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (Beyotime) supplemented with 1 mM of phenylmethyl‐sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) for 10 min on ice and centrifuged at 14 000 × g. The supernatants were collected, and whole‐cell extracts were separated by 10% SDS‐PAGE gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (GE, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk (BD, USA) in TBST buffer and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were anti‐Tgfbr1 (1:1000, Abcam) and anti‐β‐actin (1:1000, Abcam). After washing with PBS five times, the membranes were incubated with anti‐rabbit (1:50 000, Abcam) secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature.

Statistical analysis

Continuous normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analysed using the GraphPad Prism software, V. 8.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). Differences between groups were analysed using the two‐tailed Student's t‐test. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

tsRNAs transcriptome profiling in the initial stage of cardiotoxin muscle injury

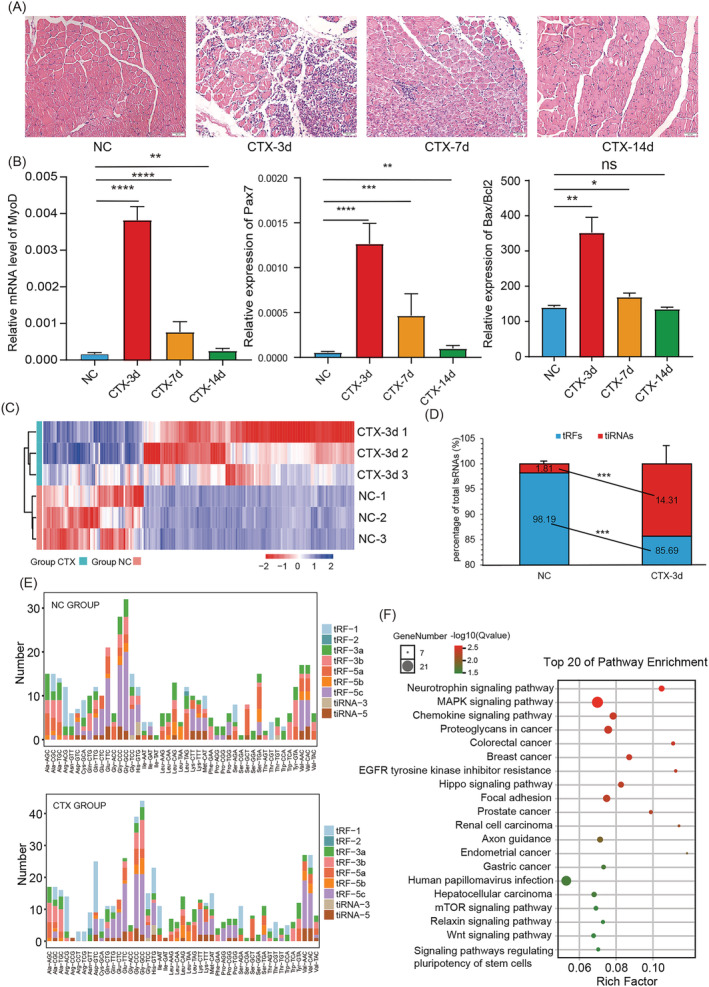

The mice's TA muscles were harvested on Days 0, 3, 7 and 14 after CTX treatment. HE staining revealed inflammation and muscle fibres in the injured anterior tibial muscles, which were highest on Day 3. Then, the muscle gradually recovered at 7 and 14 days after CTX treatment (Figure 1 A ). qRT‐PCR showed that the MyoD and Pax7 expression up‐regulated significantly on Day 3 after CTX treatment and then gradually returned to normal. A similar trend was observed for Bax/Bcl2 (Figure 1 B ). In addition, we found that the expression of myoMirs, such as miR‐1 and miR‐133, decreased significantly after 3 days of CTX treatment and then gradually recovered at 7 and 14 days (Figure S1 ). These results suggest the successful establishment of the CTX skeletal muscle injury model in the experimental mice. The differently expressed tsRNAs between CTX‐3d treatment and negative control (NC) group were identified using tsRNAs sequences.

Figure 1.

The tsRNAs' expression profile in the initial stage of muscle injury induced by CTX treatment. (A) HE staining of tibial anterior muscle sections on Days 0, 3, 7 and 14 after treatment with CTX. Scale: 1 bar represents 50 μm. (B) q‐PCR for the mRNA levels of MyoD, Pax7 and Bax/Bcl2 in the anterior tibial muscle on Days 0, 3, 7 and 14 after CTX treatment. (C) The cluster heatmap for the dysregulated tsRNAs in anterior tibial muscle on Day 3 after CTX treatment. (D) The proportion of tiRNAs and tRFs to total tsRNAs in the NC group and the CTX‐3d group. (E) The different subtypes of tsRNAs from different tRNAs in the NC group and the CTX group. (F) Enrichment analysis of the top 10 overexpressed tsRNAs after CTX treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.05, *** represents P < 0.001 and **** represents P < 0.0001. ns, not significant. The relative mRNA levels are normalized to β‐actin.

There was a significant difference in the expression of tsRNAs between the NC group and the CTX‐3d group. A total of 621 differentially expressed tsRNAs were identified. Of these, 126 tsRNAs were overexpressed, and 61 tsRNAs were under‐expressed in the CTX‐3d group (|log2FC| ≥ 1, P‐value < 0.05). All differentially expressed tsRNAs were shown with a hierarchical clustering heatmap (Figure 1 C ). Further analysis showed that the percentage of tRFs between 21 and 24 nt decreased significantly after CTX treatment, whereas the percentage of tRNA‐derived stress‐induced RNAs (tiRNAs) at 30–33 nt length increased significantly (Figure 1 D ). Given that tiRNAs have been linked to cellular stress, 25 we speculated that the production of these tiRNAs was related to the muscle injury following CTX treatment. In addition, the proportion of tsRNA subtypes from different tRNAs changed after CTX treatment. We found that tsRNAs from tRNA‐Gly‐CCC/GCC were the most abundant subtype (Figure 1 E ). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of the top 10 overexpressed tsRNAs revealed that the up‐regulated tsRNAs were enriched in the pathways related to inflammation, including the chemokine signalling pathway and the pathway that regulates the pluripotency of stem cells (Figure 1 F ). In summary, these results showed that compared with normal muscle tissue, the expression profile of tsRNAs was significantly different in the early stage of muscle injury, and the overexpressed tsRNAs participate in inflammation in the early stage of muscle injury.

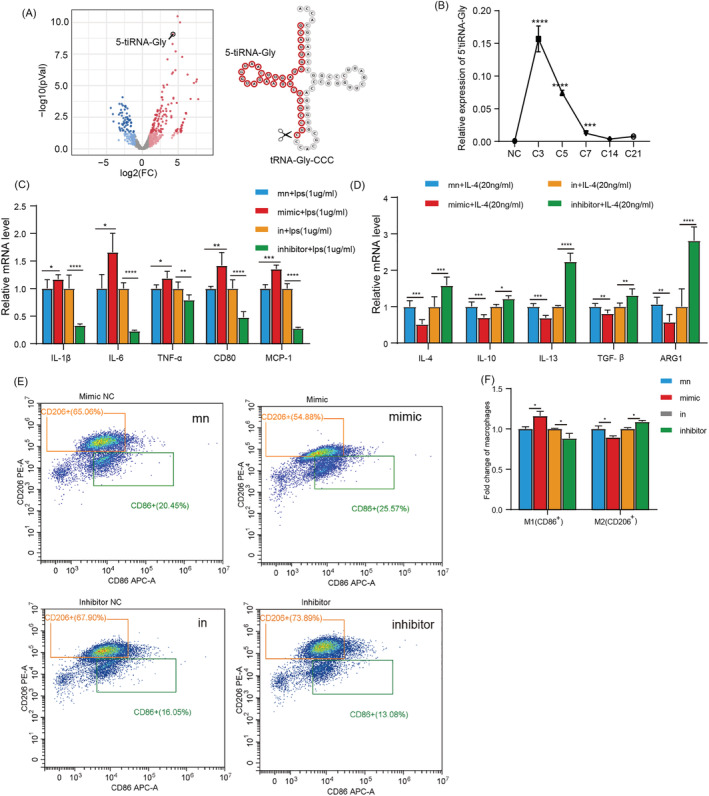

5'tiRNA‐Gly promotes macrophages inflammation and M1 polarization

The relationship between the up‐regulated tsRNAs and inflammation in the early stage of muscle injury was explored. We used q‐PCR to find that 5'tiRNA‐Gly derived from 5'‐end tRNA‐Gly‐CCC‐2‐1 (Figure 2 A ) was significantly up‐regulated, consistent with the small sequencing results, and positively correlated with the inflammation level (Figure 2 B ). Therefore, we chose 5'tiRNA‐Gly for further experiments. Interestingly, it has been reported in previous studies that tiRNAs are produced by the cleavage of mature tRNA anticodon loops by angiogenin (ANG). 26 Therefore, we quantified the mRNA expression of ANG after CTX muscle injury. The expression patterns of ANG and 5'tiRNA‐Gly were consistent (Figure S2A ). In addition, the expression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly was the highest in muscles except for the liver and spleen (Figure S2B ). These results suggest that 5'tiRNA‐Gly may be associated with inflammation and muscle development after muscle injury. Inflammation is vital and inevitable in injured skeletal muscle. The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on inflammation was explored using RAW264.7. To clarify the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on inflammatory cytokines and polarization of macrophages, the RAW264.7 cells were treated with 1 μg/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or 20 ng/mL of IL‐4 for 24 h to induce M1/M2 polarization. We first explored the changes in the endogenous 5'tiRNA‐Gly expression after LPS or IL‐4 treatment. The results showed that compared with the IL‐4, LPS treatment significantly increased the expression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly, indicating that 5'tiRNA‐Gly may be involved in the inflammatory response and polarization of macrophages (Figure S2C ). Similarly, we found that the expression of ANG was significantly positively correlated with the expression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly after IL‐4 and LPS treatment (Figure S2D,E ).

Figure 2.

5'tiRNA‐Gly promotes macrophages inflammation and M1 polarization. (A) Volcano map of the significantly differentially expressed tsRNAs between the NC and CTX groups. The arrow shows the 5'tiRNA‐Gly position and the position of the 5'tiRNA‐Gly on the secondary structure of the tRNA. (B) q‐PCR of the relative expression level of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in injured skeletal muscle. (C) The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression and knockdown on proinflammatory factors IL‐1β, IL‐6 TNF‐α, CD80 and MCP‐1 mRNA expression in RAW264.7 cells. The evaluation was performed using q‐PCR. (D) q‐PCR for the effect of the overexpression and knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly for anti‐inflammatory cytokines and the relative mRNA expression of M2 macrophage markers, including IL‐4, IL‐10, IL‐13, TGF‐β1 and ARG1 in RAW264.7 cells. (E‐F) Flow cytometry for the levels of M1 and M2 macrophages. CD86+ represents M1 type, and CD206+ represents M2 type. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.05, *** represents P < 0.001 and **** represents P < 0.0001. in, inhibitor NC; mn, mimic NC; ns, not significant. The relative mRNA levels are normalized to β‐actin.

To further explore the role of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in inflammation, 5'tiRNA‐Gly was overexpressed in RAW264.7 cells before LPS or IL‐4 treatment (Figure S2F ). Then the expression of inflammatory cytokines and marker genes for M1/M2 polarization in RAW264.7 was measured. We found that the overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL‐1β and IL‐6, and M1 markers, including TNF‐α, CD80 and MCP‐1 (Figure 2 C ). At the same time, the overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited the expression of anti‐inflammatory cytokines, including IL‐4, IL‐10 and IL‐13, and the expression of M2 markers, including TGF‐β1 and ARG1 (Figure 2 D ). Flow cytometry revealed comparable findings. Flow cytometry showed that overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the percentage of CD86+ macrophages but inhibited that of CD206+ macrophages (Figure 2 E,F ).

The regulatory effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on inflammation was further validated by inhibiting 5'tiRNA‐Gly expression using corresponding inhibitors (Figure S2G ). At the same time, we also verified whether the inhibitor of 5'tiRNA‐Gly would affect the expression of tRNA‐Gly‐CCC‐2‐1. The results showed that the expression of tRNA‐Gly‐CCC‐2‐1 was not affected by the inhibitor of 5'tiRNA‐Gly (Figure S2H ). We found that the knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly down‐regulated the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL‐1β and IL‐6, and M1 markers, including TNF‐α, CD80 and MCP‐1 (Figure 2 C ). In addition, it promoted the expression of anti‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐4, IL‐10 and IL‐13, and M2 markers TGF‐β1 and ARG1 (Figure 2 D ). At the same time, 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown inhibited the percentage of CD86+ macrophages and promoted the percentage of CD206+ macrophages (Figure 2 E,F ). In summary, these results showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly could promote the expression of proinflammatory factors and M1 polarization and inhibit the expression of anti‐inflammatory factors and M2 polarization.

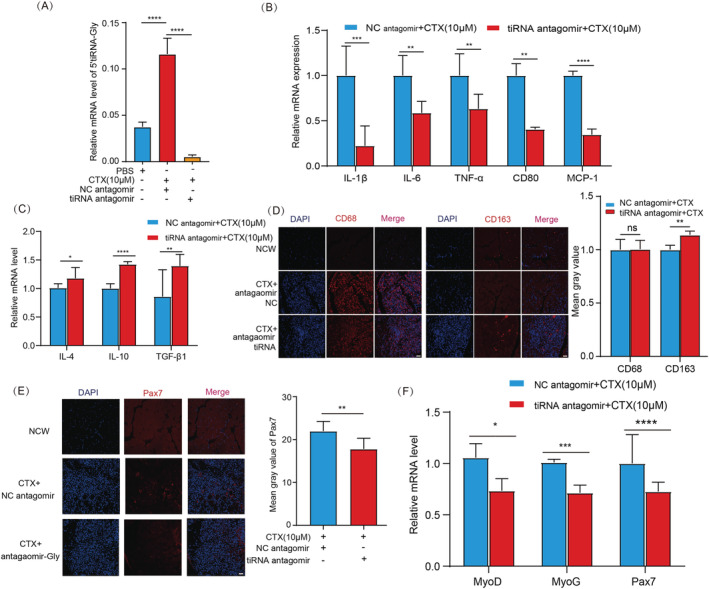

Knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibits inflammation and activates satellite cells in vivo

To further understand the role of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in inflammation, which was most overexpressed on Day 3 after CTX treatment in mice, we blocked 5'tiRNA‐Gly function using antagomir in vivo (Figure 3 A ). We found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown modulated the expression of mRNAs for proinflammatory factors and genes for M1 markers (Figure 3 B ) but up‐regulated the expression of mRNAs for anti‐inflammatory cytokines and markers for M2 genes (Figure 3 C ), consistent with in vitro results. Immunofluorescence results showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown had no effect on the number of macrophages. However, 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown increased the infiltration of M2 macrophages to the skeletal muscles (Figure 3 D ). These results showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown inhibited early inflammation in vivo. q‐PCR and immunofluorescence analyses further showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown modulated the expression of Pax7 in vivo (Figure 3 E ). Pax7 regulates satellite stem cell activation, implying that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown inhibited the activation of satellite stem cells. Satellite stem cells are one of the main contributors to muscle regeneration. After activation, they differentiate into myoblasts and then myotubes to repair damaged muscle fibres. 27 , 28 Therefore, we further explored the changes in the mRNA expression of myogenic differentiation factors MyoD and MyoG in the skeletal muscles. We found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown modulated the expression of MyoD and MyoG mRNAs in vivo (Figure 3 F ). Together, these results demonstrated that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown inhibits inflammation and activation of muscle satellite cells in vivo.

Figure 3.

The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown on inflammation and the activation of satellite cells in vivo. (A) Validation of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibition using q‐PCR. (B) The relative mRNA expression of IL‐1β, IL‐6, TNF‐α, CD80 and MCP‐1 in vivo by q‐PCR after 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown. (C) Relative mRNA expression of anti‐inflammatory cytokines and M2 macrophage marker genes in vivo, including IL‐4, IL‐10 and TGF‐β1 by q‐PCR after 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of CD68 (left side) and CD163 (right side) in tibialis anterior muscle in the NC group, the CTX + antagomir NC group and the CTX + antagomir tiRNA group. Scale: 1 bar represents 100 μm. The immunofluorescence images were analysed using the ImageJ software. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis of Pax7 levels in tibialis anterior muscle in the NC group, the CTX + antagomir NC group and the CTX + antagomir tiRNA group. Scale: 1 bar represents 100 μm. The amount of Pax7 was quantified using the ImageJ software. (F) The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown on Pax7, MyoD and MyoG mRNA expression in vivo after CTX treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.05, *** represents P < 0.001 and **** represents P < 0.0001. ns, not significant. The relative mRNA levels are normalized to β‐actin.

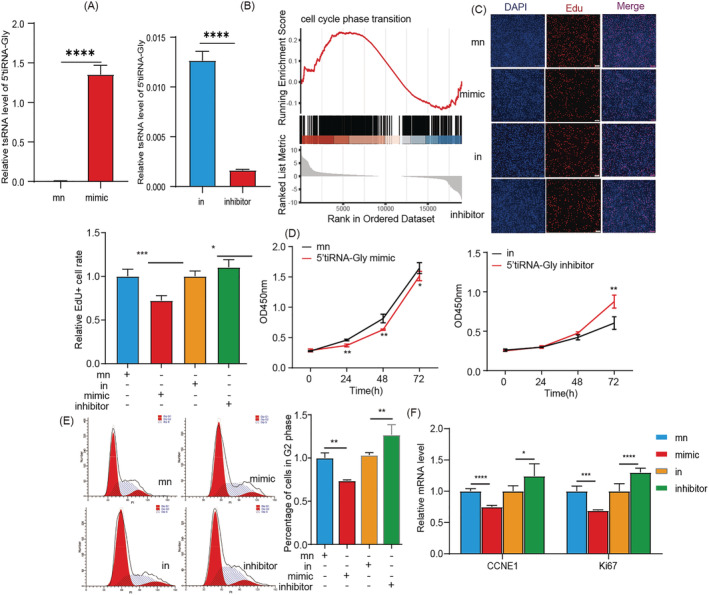

5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibits myoblasts proliferation and promotes myoblasts differentiation

We found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown inhibited the activation of satellite stem cells and may inhibit the differentiation of myoblasts in vivo. Further effects of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on muscle regeneration were analysed in C2C12 cells. We transfected mimic or inhibitor of 5'tiRNA‐Gly into C2C12 cells. After 24 h, the 5'tiRNA‐Gly expression in C2C12 cells increased or decreased significantly (Figure 4 A ). Transcriptome analysis under 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression dysregulated the expression of genes that regulate the cell cycle process (Figure 4 B ). Further, the Edu assay validated the inhibition effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on C2C12 proliferation (Figure 4 C ). CCK‐8 further showed that the overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited the proliferation of C2C12 cells, whereas 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown caused an opposite effect (Figure 4 D ). In addition, the overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly significantly decreased the number of C2C12 cells in the G2 phase and the mRNA expression of cyclin E1 (CCNE1) and Ki67. Contrarily, 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockout increased the number of cells in the G2 phase and the mRNA expression of CCNE1 and Ki67 (Figure 4 E,F ), implying that 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibits the proliferation of myoblasts.

Figure 4.

The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on myoblast proliferation. (A) Expression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in C2C12 cells after overexpression or knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly. (B) GSEA for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression on the cell cycle transition. (C) Edu assay for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression or knockdown on the proliferation of C2C12 cells. Scale: 1 bar represents 100 μm. The ImageJ software results for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression or knockdown on the proliferation of C2C12 cells. (D) CCK‐8 experiment for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on the viability of C2C12 cells. (E) Flow cytometry results for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression (above) or knockdown (below). (F) The relative mRNA expression of CCNE1, a cell cycle‐related gene, and Ki67 after 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression or knockdown in C2C12 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.05, *** represents P < 0.001 and **** represents P < 0.0001. in, inhibitor NC; mn, mimic NC; ns, not significant. The relative mRNA levels are normalized to β‐actin.

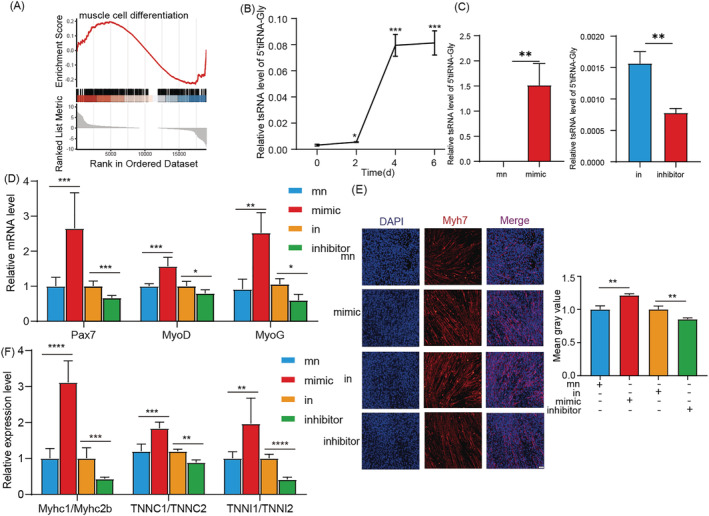

GSEA further validated that the overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly disrupted the differentiation of muscle cells (Figure 5 A ). We found that the expression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly gradually increased at the myogenic differentiation stage, peaking on Day 4, and remained high thereafter (Figure 5 B ). These results suggest that 5'tiRNA‐Gly may participate in regulating myoblast differentiation. Further analyses were performed to assess the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression or inhibition in C2C12 cells during the differentiation period until Day 6 (Figure 5 C ). We found that overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly significantly promoted the expression level of Pax7 mRNA. Also, overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the expression of myogenic differentiation marker genes MyoD and MyoG at 6 days. On the contrary, inhibiting 5'tiRNA‐Gly modulates the expression of MyoD, MyoG and Pax7 mRNAs (Figure 5 D ). Immunofluorescence analysis of Myh7 showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the formation of myotubes in C2C12 cells, whereas 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown caused an opposite effect (Figure 5 E ). Also, we explored the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on the ratio of slow and fast muscles. Based on the marker genes of slow and fast muscles, we found that overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly could promote the ratio of slow and fast muscles, whereas inhibition of 5'tiRNA‐Gly caused an opposite effect (Figure 5 F ). All these results implied that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promotes the differentiation of myoblasts.

Figure 5.

The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on myoblast differentiation. (A) GSEA for the correlation between 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression and the muscle cell differentiation. (B) The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on the self‐differentiation of C2C12 cells. (C) Expression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in C2C12 cells differentiation process after overexpression or knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly. (D) The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression or knockdown on the relative mRNA expression of Pax7, MyoD and MyoG in C2C12 cells differentiation. (E) Immunofluorescence results on the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on the expression of Myh7 in C2C12 cells. The analysis was performed on Day 6 after C2C12 cells differentiation. Scale: 1 bar represents 100 μm. The immunofluorescence images for Myh7 quantities were analysed using the ImageJ software. (F) The effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression or knockdown on slow/fast muscle marker expression during C2C12 cells differentiation. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.05, *** represents P < 0.001 and **** represents P < 0.0001. in, inhibitor NC; mn, mimic NC; ns, not significant. The relative mRNA levels are normalized to β‐actin.

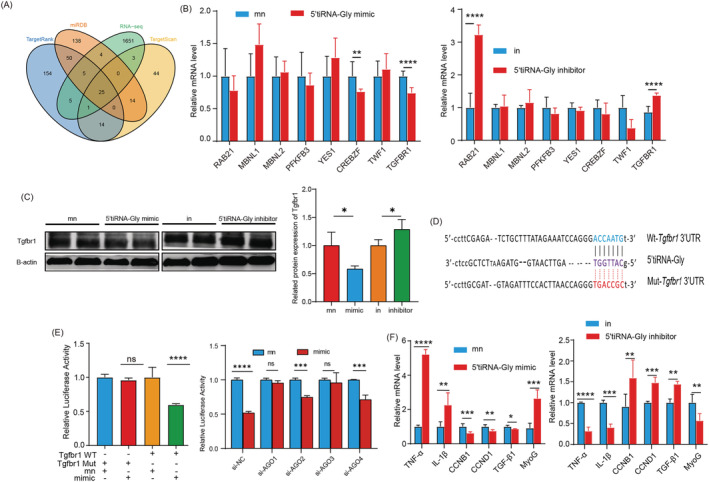

5'tiRNA‐Gly directly targets Tgfbr1 and inhibits the TGF‐β signalling pathway

Many studies and reviews have reported that tsRNAs can target the 3' untranslated region (UTR) region of mRNA in the same mechanism as miRNAs. 22 , 29 , 30 For example, a 22‐nt long 31 CCA tRF uses canonical miRNA machinery to repress replication protein A1 (RPA1) mRNA, among other genes. 31 Deng and colleagues demonstrated that the 3' portion of a 5' tRF (named tRF5‐GluCTC) targets the 3'UTR of APOER2. 32 The mechanism underlying the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly was analysed. The gene targets for 5'tiRNA‐Gly were identified using TargetScan, miRDB, TargetRank and RNA‐seq (Figure 6 A ). Our analysis identified eight potential target genes for 5'tiRNA‐Gly. To validate our findings, we analysed the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression on the expression of mRNA for the target genes. The mRNA levels of the eight potential target genes after 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown were also analysed. We found that overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited the expression of mRNA for Tgfbr1. Meanwhile, 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown caused an opposite effect (Figure 6 B ). Western blot showed that the protein level of Tgfbr1 was also regulated by 5'tiRNA‐Gly (Figure 6 C ). Tgfbr1 is a key component of the TGF‐β signalling pathway, which participates in inflammation, cell proliferation, muscle differentiation and fibrosis processes. 33 Further correlation analysis showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly and Tgfbr1 showed a significant negative correlation trend in the TA muscles, C2C12 cells and RAW264.7 cells (Figure S3 ). Prediction analysis revealed the potential 5'tiRNA‐Gly binding sites in the 3'UTR region of the Tgfbr1 gene (Figure 6 D ). Further analyses were performed using pSiCheck2 reporter vector carrying Tgfbr1 3'UTR wild‐type and 3'UTR mutant‐type sites (Figure 6 D ). The plasmid was co‐transfected along with 5'tiRNA‐Gly or mimic NC into 293T cells for 48 h before the dual‐luciferase reporter assay. We found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly significantly decreased the luciferase activity of 293T cells (Figure 6 E ). Previous studies have shown that Argonautes family protein (AGO) family proteins bind to tsRNA and participate in the regulation of gene expression. 22 Therefore, we knocked out the expression of AGO1, AGO2, AGO3 and AGO4 and observed the changes of luciferase expression. 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited luciferase expression restored by silencing AGO1 and AGO3 (Figure 6 E ). These results suggest that AGO1 and AGO3 mediate 5'tiRNA‐Gly regulation of Tgfbr1 expression. To further verify the relationship between 5'tiRNA‐Gly and TGF‐β signalling pathway, we quantified the expression of mRNA for TGF‐β1 and five genes downstream of the TGF‐β signalling pathway. We found that the overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited the expression of TGF‐β1 mRNA and genes downstream of the TGF‐β signalling pathway, including cyclin B1 (CCNB1), cyclin D1 (CCND1) and MyoG. Knockdown is the opposite (Figure 6 F ). In summary, these results demonstrate that 5'tiRNA‐Gly exerts its biological function by directly targeting Tgfbr1 to regulate the TGF‐β signalling pathway.

Figure 6.

The mechanism underlying the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly on muscle regeneration. 5'tiRNA‐Gly directly targets Tgfbr1 and inhibits the TGF‐β signalling pathway. (A) The genes targeted by 5'tiRNA‐Gly were identified using TargetScan, TargetRank, miRDB and transcriptome sequence analyses. (B) Left: q‐PCR analyses for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly overexpression on the eight potential target genes. Right: q‐PCR for the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly knockdown on the expression of eight potential target genes. (C) The protein level of Tgfbr1 was changed when 5'tiRNA‐Gly was overexpressed and inhibited. (D) The Tgfbr1‐3'UTR‐wt or mut reporter plasmid sequence. (E) Left: relative luciferase activity of the Tgfbr1‐3'UTR‐wt or mut reporter plasmid was co‐transfected into 293T cells with 5'tiRNA‐Gly mimics or mn. Right: relative luciferase activity of the Tgfbr1‐3'UTR‐wt reporter plasmid was co‐transfected into 293T cells with si‐AGO and 5'tiRNA‐Gly mimics or mn. (F) The relative expression of mRNAs for downstream genes of the TGF‐β signalling pathway after overexpression (left) and knockdown (right) of 5'tiRNA‐Gly. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.05, *** represents P < 0.001 and **** represents P < 0.0001. in, inhibitor NC; mn, mimic NC; ns, not significant. The relative mRNA and protein levels are normalized to β‐actin.

Discussion

We identified the top 10 overexpressed tsRNAs in injured skeletal muscles induced using CTX. We found that they were annotated to chemokine signalling pathway and pathways that regulate the pluripotency of stem cells. These results show that inflammation in the early stage of muscle injury may be related to the expression of tsRNAs. Further in vivo analyses revealed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly was overexpressed in injured skeletal muscles and that its expression positively correlated with the degree of inflammation. Interestingly, we also found that the cleavage enzyme ANG of tiRNAs also increased significantly and that the trend of mRNA expression was consistent with the trend of 5'tiRNA‐Gly mRNA expression. We succeeded in overexpressing 5'tiRNA‐Gly many folds via 5'tiRNA‐Gly mimetic transfection. It is well known that endogenous tsRNAs contain multiple types of RNA modifications compared with synthetic tsRNA mimics. At present, the artificial modification technology of nucleic acid is still relatively limited and cannot be systematically studied. Therefore, the study of tsRNA is only based on sequence. We found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted macrophage polarization to M1 type and the release of proinflammatory factors in vitro. However, inhibition of 5'tiRNA‐Gly reversed the above phenomena. Inflammation occurs in the early stages of muscle injury, which is necessary to promote healing. 10 , 34 High infiltration of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils occurs 1–6 h after injury. Macrophages are the dominant inflammatory cells 48 h after injury. 34

Infiltrating macrophages remove damaged myofilaments, muscle sarcolemma and other cytoplasmic structures through phagocytosis. 35 Our results demonstrated that 5'tiRNA‐Gly could promote the inflammation of macrophages, indicating that 5'tiRNA‐Gly accelerates the clearing of damaged or necrotic areas at the early stage of skeletal muscle injury by macrophages, consistent with in vivo results. Knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited inflammation in the early stage of muscle injury, delaying cleaning up the damaged or necrotic areas and, thus, muscle regeneration. We further found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly participates in the activation of satellite stem cells. Knockdown of 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibited the expression of Pax7 in vivo. Activated satellite cells differentiate into new myoblasts before fusing with damaged fibres to form myotubes, which are immature fibres. 36 Further analyses revealed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes but inhibited the proliferation of these cells. In general, we found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted inflammatory response mediated by macrophages in the early stage of skeletal muscle injury and accelerated macrophage clearance of damaged or necrotic areas. Besides, 5'tiRNA‐Gly promoted satellite cell activation and myoblast differentiation, accelerating muscle fibre regeneration.

Further analyses were performed to reveal the molecular mechanism underlying the functioning of 5'tiRNA‐Gly. tsRNAs are widely present in numerous organisms, showing the characteristics of functional regulated ncRNAs. tsRNAs perform numerous biological functions through varied molecular mechanisms. Most studies have found that tsRNAs function in a manner similar to microRNAs. Particularly, tsRNAs regulate transcription of mRNAs by directly binding to these molecules or by combining with AGO. They mainly utilize the 5'‐end seed sequence (evolutionarily conserved fragments on tsRNAs, from the second to the eighth nucleotides) to bind to the 3'UTR of the target gene, thus, silencing the expression of the target gene. Transgene silencing was first demonstrated as a tRF cloned from human mature B cells and was named CU1276. CU1276 inhibits the expression of RPA1 by binding to the 3'UTR region of RPA1 mRNA at the 5'‐end seed sequence, inhibiting cell proliferation. 37 The potential gene targets for 5'tiRNA‐Gly were identified using TargetScan, miRDB and TargetRank tools, as well as RNA‐seq data in cells overexpressing 5'tiRNA‐Gly. We found that Tgfbr1 is a 5'tiRNA‐Gly target. Tgfbr1 showed a significant negative correlation with 5'tiRNA‐Gly. We found that 5'tiRNA‐Gly could significantly reduce the mRNA and protein expression levels of Tgfbr1. The dual‐luciferase reporter assay further confirmed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly directly targets the Tgfbr1 gene mediated by AGO1/3. We speculated that 5'tiRNA‐Gly inhibits Tgfbr1 expression by destabilizing the Tgfbr1 mRNA. Tgfbr1 is a key component in the transmission of extracellular stimuli downstream of the TGF‐β signalling pathway. 38 In order to explore whether 5'tiRNA‐Gly exerts biological functions through the TGF‐β signalling pathway after directly targeting Tgfbr1, we quantified the mRNA expression level changes of several downstream genes of the TGF‐β signalling pathway after overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly. q‐PCR analysis showed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly dysregulated the expression of six genes, including TGF‐β1, related to the TGF‐β signalling pathway. Generally, our analyses revealed that 5'tiRNA‐Gly exerts its effects on inflammation as well as myoblast proliferation and differentiation through the TGF‐β signalling pathway by targeting Tgfbr1.

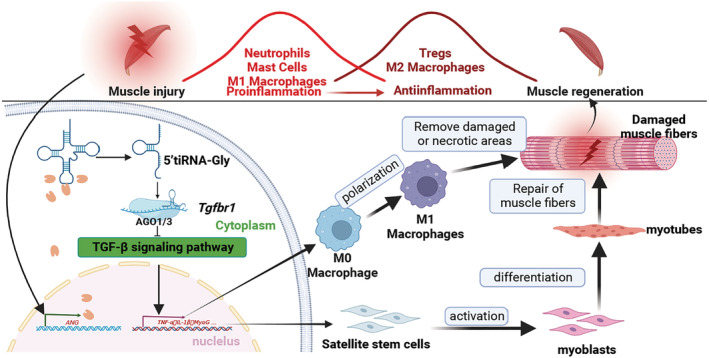

In summary, overexpression of 5'tiRNA‐Gly occurs in the skeletal muscles after injury. Also, 5'tiRNA‐Gly promotes muscle regeneration by promoting early inflammatory response, satellite stem cell activation and myoblast differentiation. Mechanistically, 5'tiRNA‐Gly exerts its effect by directly targeting Tgfbr1 to regulate the TGF‐β signalling pathway (Figure 7 ). The findings of this study provide a new perspective on skeletal muscle injury treatment.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram for the mechanism underlying the effect of 5'tiRNA‐Gly in injured skeletal muscles. During the early stages of muscle injury, the expression of tiRNA cleaving enzyme ANG increased significantly; tRNA‐Gly‐CCC‐2‐1 is cleaved to produce numerous 5'tiRNA‐Gly, which directly disrupt the transcription of genes downstream of the TGF‐β signalling pathway by combining with Tgfbr1 3'UTR (mediated by AGO1/3) and, thus, promoting macrophage inflammation, satellite stem cell activation and myoblast differentiation. These events culminate in the regeneration of muscle injury.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Key Laboratory of Livestock and Poultry Multi‐omics, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Institute of Animal Genetics and Breeding, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, for the experimental site, laboratory equipment and technical support. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31902135, 31972524); Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2021ZDZX008, 2021YJ0265, SCSZTD‐2023‐08‐09); China Agriculture Research System (CARS‐pig‐35). The authors certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 39

Shen L., Liao T., Chen Q., Lei Y., Wang L., Gu H., Qiu Y., Zheng T., Yang Y., Wei C., Chen L., Zhao Y., Niu L., Zhang S., Zhu Y., Li M., Wang J., Li X., Gan M., and Zhu L. (2023) tRNA‐derived small RNA, 5'tiRNA‐Gly‐CCC, promotes skeletal muscle regeneration through the inflammatory response, Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 14, 1033–1045, 10.1002/jcsm.13187

Linyuan Shen and Tianci Liao have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Mailin Gan, Email: ganmailin@stu.sicau.edu.cn.

Li Zhu, Email: zhuli@sicau.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Schmalbruch H, Lewis DM. Dynamics of nuclei of muscle fibers and connective tissue cells in normal and denervated rat muscles. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sass FA, Fuchs M, Pumberger M, Geissler S, Duda GN, Perka C, et al. Immunology guides skeletal muscle regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang W, Hu P. Skeletal muscle regeneration is modulated by inflammation. Journal of orthopaedic translation. 2018;13:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forcina L, Cosentino M, Musarò A. Mechanisms regulating muscle regeneration: insights into the interrelated and time‐dependent phases of tissue healing. Cells. 2020;9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muñoz‐Cánoves P, Serrano AL. Macrophages decide between regeneration and fibrosis in muscle. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2015;26:449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall JS. Mast‐cell responses to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fielding RA, Manfredi TJ, Ding W, Fiatarone MA, Evans WJ, Cannon JG. Acute phase response in exercise. III. Neutrophil and IL‐1 beta accumulation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R166–R172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba‐Amer Y, van Rooijen N, Plonquet A, et al. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1057–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karalaki M, Fili S, Philippou A, Koutsilieris M. Muscle regeneration: cellular and molecular events. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2009;23:779–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fiore D, Judson RN, Low M, Lee S, Zhang E, Hopkins C, et al. Pharmacological blockage of fibro/adipogenic progenitor expansion and suppression of regenerative fibrogenesis is associated with impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. Stem Cell Res. 2016;17:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang L, Zhou L, Jiang P, Lu L, Chen X, Lan H, et al. Loss of miR‐29 in myoblasts contributes to dystrophic muscle pathogenesis. Mol Ther J Am Soc Gene Ther. 2012;20:1222–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zanotti S, Gibertini S, Curcio M, Savadori P, Pasanisi B, Morandi L, et al. Opposing roles of miR‐21 and miR‐29 in the progression of fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:1451–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen M, Wei X, Song M, Jiang R, Huang K, Deng Y, et al. Circular RNA circMYBPC1 promotes skeletal muscle differentiation by targeting MyHC. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;24:352–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang ZK, Li J, Guan D, Liang C, Zhuo Z, Liu J, et al. A newly identified lncRNA MAR1 acts as a miR‐487b sponge to promote skeletal muscle differentiation and regeneration. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9:613–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schimmel P. The emerging complexity of the tRNA world: mammalian tRNAs beyond protein synthesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu W, Liu Y, Pan Z, Zhang X, Qin Y, Chen X, et al. Systematic analysis of tRNA‐derived small RNAs discloses new therapeutic targets of caloric restriction in myocardial ischemic rats. Frontiers Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:568116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pan X, Geng X, Liu Y, Yu M, Mishra MK, Xu X, et al. Transfer RNA fragments in the kidney in hypertension. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex: 1979). 2021;77:1627–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dou R, Zhang X, Xu X, Wang P, Yan B. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomal tsRNA‐21109 alleviate systemic lupus erythematosus by inhibiting macrophage M1 polarization. Mol Immunol. 2021;139:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luan N, Mu Y, Mu J, Chen Y, Ye X, Zhou Q, et al. Dicer1 promotes colon cancer cell invasion and migration through modulation of tRF‐20‐MEJB5Y13 expression under hypoxia. Front Genet. 2021;12:638244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pawar K, Shigematsu M, Sharbati S, Kirino Y. Infection‐induced 5'‐half molecules of tRNAHisGUG activate Toll‐like receptor 7. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tao EW, Wang HL, Cheng WY, Liu QQ, Chen YX, Gao QY. A specific tRNA half, 5'tiRNA‐His‐GTG, responds to hypoxia via the HIF1α/ANG axis and promotes colorectal cancer progression by regulating LATS2. J Exp Clin Canc Res: Cr. 2021;40:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shen Y, Yu X, Zhu L, Li T, Yan Z, Guo J. Transfer RNA‐derived fragments and tRNA halves: biogenesis, biological functions and their roles in diseases. J Mol Med (Berl). 2018;96:1167–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chazaud B. Inflammation and skeletal muscle regeneration: leave it to the macrophages! Trends Immunol. 2020;41:481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li S, Xu Z, Sheng J. tRNA‐derived small RNA: a novel regulatory small non‐coding RNA. Genes. 2018;9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elkordy A, Mishima E, Niizuma K, Akiyama Y, Fujimura M, Tominaga T, et al. Stress‐induced tRNA cleavage and tiRNA generation in rat neuronal PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2018;146:560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tidball JG, Villalta SA. Regulatory interactions between muscle and the immune system during muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1173–R1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cantini M, Giurisato E, Radu C, Tiozzo S, Pampinella F, Senigaglia D, et al. Macrophage‐secreted myogenic factors: a promising tool for greatly enhancing the proliferative capacity of myoblasts in vitro and in vivo. Neurological sciences: official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2002;23:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zong T, Yang Y, Lin X, Jiang S, Zhao H, Liu M, et al. 5'‐tiRNA‐Cys‐GCA regulates VSMC proliferation and phenotypic transition by targeting STAT4 in aortic dissection. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids. 2021;26:295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xie Y, Yao L, Yu X, Ruan Y, Li Z, Guo J. Action mechanisms and research methods of tRNA‐derived small RNAs. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maute RL, Schneider C, Sumazin P, Holmes A, Califano A, Basso K, et al. tRNA‐derived microRNA modulates proliferation and the DNA damage response and is down‐regulated in B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1404–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deng J, Ptashkin RN, Chen Y, Cheng Z, Liu G, Phan T, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus utilizes a tRNA fragment to suppress antiviral responses through a novel targeting mechanism. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2015;23:1622–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K. TGF‐β and the TGF‐β family: context‐dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McClung JM, Davis JM, Carson JA. Ovarian hormone status and skeletal muscle inflammation during recovery from disuse in rats. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lescaudron L, Peltékian E, Fontaine‐Pérus J, Paulin D, Zampieri M, Garcia L, et al. Blood borne macrophages are essential for the triggering of muscle regeneration following muscle transplant. Neuromuscular Disorders: NMD. 1999;9:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Collins CA, Olsen I, Zammit PS, Heslop L, Petrie A, Partridge TA, et al. Stem cell function, self‐renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell. 2005;122:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shao Y, Sun Q, Liu X, Wang P, Wu R, Ma Z. tRF‐Leu‐CAG promotes cell proliferation and cell cycle in non‐small cell lung cancer. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2017;90:730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vander Ark A, Cao J, Li X. TGF‐β receptors: in and beyond TGF‐β signaling. Cell Signal. 2018;52:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. von Haehling S, Morley JE, Coats AJS, Anker SD. Ethical guidelines for publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle: update 2021. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12:2259–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting information