Abstract

Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation (NOIS) has been the backbone of anxiety alleviation in dentistry for a long time. Advantages of nitrous oxide (N2O) include anxiolysis, mild analgesia, and amnesia. It also has the ability to raise the patient pain threshold, providing rapid analgesia (RA), thus enhancing the action of any local anesthesia used. This paper describes the technique of NOIS in detail and highlights its objectives, advantages, indications, monitoring, and safety profile. Other than the specialty of pediatric dentistry, this paper also highlights the applications and merits of NOIS in adult, geriatric, and special healthcare needs dentistry. Away from dentistry, it also brings to light the multidisciplinary applications of NOIS in other medical streams. This review could be a valuable interpretation on the present position of N2O sedation in dentistry and a valuable starting point for future perspectives.

How to cite this article

Khinda V, Rao D, Singh Sodhi SP. Nitrous Oxide Inhalation Sedation Rapid Analgesia in Dentistry: An Overview of Technique, Objectives, Indications, Advantages, Monitoring, and Safety Profile. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2023;16(1):131-138.

Keywords: Inhalation sedation, Nitrous oxide, Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation, Oxygen, Rapid analgesia

Introduction

The use of nitrous oxide (N2O) as a tool for painless dental and surgical procedures was discovered by Horace Wells, an American dentist.1 Wells is now recognized as the Father of Anesthesia. Since this discovery in Connecticut on December 11, 1844, nitrous oxide inhalation sedation (NOIS) has undergone phenomenal change in the way it is practiced and has become the mainstay of pharmacological behavior modification and rapid analgesia (RA). From its earlier role of being a solo gas technique resulting in many complications, the standard of care currently demands dilution with oxygen (O2) to achieve desired level of titration.2 The present approach is to de-emphasize the analgesic effects of nitrous oxide–oxygen (N2O–O2) associated with high concentrations and focus on the sedative, tranquilizing, and euphoric benefits of dilute concentrations. An examination of the international guidelines makes it evident that the titrated N2O in O2 is counted as a reliable and valuable dental sedation modality and endorsed as a first-line option particularly for children.3,16 Benefits of N2O include anxiolysis, mild analgesia, and amnesia.11 It is considered as an effective calming relaxation drug commonly referred to as an anxiolytic agent.12 It also has the ability to raise the patient's pain threshold, thus enhancing the action of any local anesthetic agent used.4 It takes the edge off and delivers a comfortable patient.

Avoidance of dental treatment due to fear and anxiety (DFA) are recognized as foremost deterrents to oral health.17,21 Malamed22 states that fear, anxiety, and pain have long been connected with the practice of dentistry, and he clarifies that the semblance of the dentist as an instrument of pain is not correct. The spectrum of DFA management options include the nonpharmacological, noninvasive approaches as a starting point and then making use of invasive pharmacological approaches if required. Majority of the situations in dentistry can be managed with the nonpharmacological techniques of behavior modification but many cases must be sedated to go through a successful appointment. Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation has been one technique which has found high level of acceptance worldwide. Long-standing safety profile and a track record of minimal complications have enhanced its popularity.23 But in spite of a proven history of safety and efficacy, NOIS continues to be underutilized as a technique of pharmacological behavior modification in many parts of the world. Reasons could be lack of adequate training in the undergraduate university programs, and availability of insufficient opportunities for practising dentists to upgrade their skills in sedation protocols. Dental practitioners need to learn the technique well and all other aspects related with it to gain confidence. An example of good training at university level can be found at the faculty of dentistry, Dalhousie University.24 The students of dentistry are provided an opening to join a course on N2O sedation in their fourth year of DDS program. The course fulfils the requirements specified in the guidelines of the various jurisdictions in Canada. It is not mandatory to complete the course to graduate, but most of the students sign up for it every year. Those who complete the course are provided with certification.

The mechanism of action of N2O was revisited by Yee et al.23 in 2019. They also reviewed the current gas delivery systems in use. Commenting on the existing data related with complications and the safety profile of the NOIS they also provided suggestions on equipment, training, and practices for safe N2O–O2 inhalation sedation. Kharouba et al.25 in 2020 reviewed the safety of N2O as a sedative agent at various concentrations in pediatric dentistry setting and concluded that 60% concentration of N2O was more effective. Ergüven et al.26 studied the effects of conscious sedation on cognitive functions and concluded that the capability to perform fine motor skills was not entirely regained 15 minutes after cessation of sedation and concluded that patients must be informed about avoiding activities that require attention/focus soon after N2O sedation. Yun et al.27 in their study on elderly hypertensive patients investigated the safety and efficacy of NOIS-assisted extractions under local anesthesia. They found that NOIS-assisted local anesthesia can be a safe and effective anesthetic method in tooth extraction of elderly patients with hypertension. Sandhu et al.28 in their 2017 randomized split-mouth cross-over study investigated the physiological stress reduction during lengthy periodontal surgeries. They assessed the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative stress levels with and without NOIS as an adjunct during surgical procedures. Evaluation of serum cortisol levels was performed, and vital parameters were examined preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively. The findings showed a decline in serum cortisol levels, blood pressure (BP) and pulse rate, and an enhancement in respiratory rate and arterial blood O2 saturation during which was significant statistically during surgical procedures in periodontics under NOIS. They concluded that NOIS when used as an adjunct to local anesthesia for periodontal surgical procedures was efficient in decreasing stress physiologically during lengthy periodontal surgical procedures. Ryding and Murphy24 surveyed views of the dentists regarding tactics to pain and anxiety management in Canada and discussed the implications of their findings for curriculum setup.

This paper describes the technique of NOIS and highlights its objectives, advantages, indications, monitoring, and safety profile and could be a valuable interpretation on the present position of N2O sedation in dentistry and a valuable starting point for future perspectives. Use of safe anxiolytic agents, such as N2O for our patients, could have favorable outcomes for them and the dentists.

Objectives/Advantages of NOIS4,23,24,29–31

Rapid onset of action.

Peak clinical actions in a time span permitting titration.

Two-way titrability.

Flexible duration of action.

Decrease or eradication of anxiety.

Decrease of inappropriate movement and response to dental therapy.

Enhance communication and cooperation of the patients.

Raise the pain reaction threshold.

Increase tolerance for longer appointments.

Aid in treatment of the special heathcare and medically compromised patients.

Reduce gagging.

Enhance the potency of other sedatives.

Particularly useful for the first-time patient.

Allows increased working time.

Very useful for patients who tire quickly, or experience patient burn out.

Rapid and complete recovery.

Disadvantages of NOIS4,23,25,29–31

Deficit of potency.

Dependent mostly on psychological reinforcement.

Obstruction of the nasal hood with injection to the maxillary anterior region.

Failure in patients with nasal blockage.

Probable environmental pollution and occupational exposure hazard.

Space occupied by equipment within the dental surgery suite.

Indications of NOIS4,23,25,29–31

Patients who are anxious or fearful.

Special healthcare needs patients.

Patients with gag reflex that obstructs dental care.

In patients where effective local anesthesia cannot be achieved.

Lengthy dental procedures in an otherwise cooperative child.

Contraindications of NOIS4,23,25,29–31

Few chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases.

Ongoing upper respiratory tract infections.

If the patient has had a middle ear disturbance/surgery in the recent past.

Drug addictions.

During first trimester of pregnancy.

Deficiency of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and cobalamin (vitamin 12).

Adult patients having a compulsive personality.

Claustrophobic patients.

Serious emotional conflicts and patients with serious personality disorders who are under psychiatric care.

If the patient is on bleomycin sulfate, receiving psychotropic drugs or mood elevating antidepressants.

Review of the Patient's Medical History4,23,25,29–31

Review must be performed before the choice of using NOIS is made. This evaluation must include:

History of allergies or adverse drug reactions in the past.

Current medications.

Diseases, physical abnormalities, and pregnancy status.

Previous hospitalization (when, why).

Recent illnesses (e.g., cold or congestion) that may compromise the upper respiratory tract.

Safety Features of N2O2 Delivery Systems30–33

Oxygen failure warning alarm.

Minimum O2 liter flow control.

Minimum O2 percentage control.

Oxygen flow-related auto-termination of N2O.

Oxygen fail-safe device.

Oxygen flush mechanism.

Emergency air inlet.

Quick connect for positive-pressure O2.

Diameter-index safety feature.

Pin-index safety system.

Locks.

Color coding.

Reservoir bag.

Monitoring3,13,23,30,33

Recording of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative vital signs is the standard of care. Blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate are mandatory. Preoperative notes serve as the baseline values against which the values may be compared. Additional vital signs include O2 saturation, temperature, height, and weight. The vitals must be recorded on patient's chart during every new appointment. Recording of baseline vital signs must be performed at a non-threatening time. Pulse monitoring is recommended for all patients in routine preoperative evaluation. Below 60 and above 110 beats/minute (in adults) must be assessed prior to starting treatment (Table 1). Several methods exist to monitor BP. Blood pressure can be recorded at regular intervals (e.g., every 2 minutes) using the newer monitors encoded accordingly (Table 2). Adequacy of respiration may be monitored by (1) ascertaining the respiratory rate, (2) watching the rise and fall of chest wall, (3) examining the color of oral mucous membranes and fingernail beds, and (4) watching the reservoir bag inflate and deflate (Table 3). Pulse oximeter is an electronic device for the measurement of O2 saturation of the arterial blood (SpO2). When we breathe ambient air at sea level, normal O2 saturation is 96–99%; at an altitude of 5,000 feet, about 92%, and at 10,000 feet, approximately 88%. Pulse oximeter detects and quantifies hypoxemia. Recording of temperature is not as crucial as are cardiovascular and respiratory parameters. Nevertheless, it is essential to ascertain whether the patient has raised temperature prior to the commencement of the treatment. Fever increases the workload of cardiovascular and respiratory systems. The ability of the patient to bear stress declines. Besides enlisting the help of the monitoring equipment, all patients undergoing conscious sedation should be observed throughout the procedure for the presence of the following five parameters.

Table 1.

Average pulse rate at different ages

| Age | Lower limits of normal | Average | Upper limits of normal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn | 70 | 120 | 170 |

| 1-11 months | 80 | 120 | 160 |

| 2 years | 80 | 110 | 130 |

| 4 years | 80 | 100 | 120 |

| 6 years | 75 | 100 | 115 |

| 8 years | 70 | 90 | 110 |

| 10 years | 70 | 90 | 110 |

From Behrman RE, Vaughn VC III: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, ed 12, Philadelphia, 1983, WB Saunders

Table 2.

Normal blood pressure for various ages (figures have been rounded off to nearest decimal place)

| Age | Mean systolic ± 2 SO | Mean diastolic ± 2 SO |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn | 80 ± 16 | 46 ± 16 |

| 6 months-1 year | 89 ± 29 | 60 ± 10* |

| 1 year | 96 ± 30 | 66 ± 25* |

| 2 years | 99 ± 25 | 64 ± 25* |

| 3 years | 100 ± 25 | 67 ± 23* |

| 4 years | 99 ± 20 | 65 ± 20* |

| 5-6 years | 94 ± 14 | 55 ± 9 |

| 6-7 years | 100 ± 15 | 56 ± 8 |

| 7-8 years | 102 ± 15 | 56 ± 8 |

| 8-9 years | 102 ± 15 | 57 ± 9 |

| 9-10 years | 107 ± 16 | 57 ± 9 |

| 10-1 1 years | 111 ± 17 | 58 ± 10 |

| 1 1-12 years | 1 13± 18 | 59 ± 10 |

| 12-13 years | 115 ± 19 | 59 ± 10 |

| 13-14 years | 118 + 19 | 60 + 10 |

From Nades AS, Flyer DC:Pediatric Cardiology, ed 3, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders. *In this study, the point of muffling was taken as the diastolic pressure

Table 3.

Respiratory rate by age

| Age | Rate/minute |

|---|---|

| Neonate | 40 |

| 1 week | 30 |

| 1 years | 24 |

| 3 years | 22 |

| 5 years | 20 |

| 8 years | 18 |

| 12 years | 16 |

| 21 years | 12 |

From Behrman RE, Vaughn VC Ill: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, ed 12, Philadelphia, 1983, WB Saunders

Consciousness

It is crucial that the patient remains conscious at all times during the procedure. The best means of monitoring the state of consciousness is verbal contact with the patient. However, excessive talking should not be encouraged as speaking tends to encourage mouth breathing and a subsequent decrease in drug effect. Appropriate response to the verbal commands (open or close your mouth, etc.) that ordinarily accompany dental procedures will serve the purpose of establishing verbal contact.

Respiratory Rate

During the induction period, the respiratory rate is our guide. As soon as an increase in the respiratory rate is evident, O2 should be added to the mixture. If this amount is sufficient, the respiratory rate will decrease, if not, the rate will continue to be rapid, with labored respiratory excursions and stertor.

Color

Normal mucous membranes in a well-oxygenated patient are a healthy pink and moist. Color is an important sign of the oxygenation of the patient. Cyanosis is best seen in parts of the body where the overlying epidermis is thin and subepidermal vessels are copious, such as the lips, nose, cheeks, ears, hands, feet, and the oral mucous membranes. However, in anemics, there is no color change except a slight darkening of the lips. In plethorics, there is marked cyanosis. In both these cases, the patient is getting all the O2 necessary to maintain the vital functions. Such facts should not be lost sight of by the clinician.

Comfort

One of the main objectives of N2O–O2 sedation is the production of a state in which the patient is relaxed and comfortable. It is usually achieved with N2O in concentration of about 30–40%. Once an initial state of pleasant relaxation is established, the patient should be informed that this state will be maintained throughout the appointment. On noticing the presence of mouth breathing, the dentist may readjust the N2O concentration to a lower level. Frequent deep breaths by the patient through his nose should indicate to the dentist a need for readjustment of N2O concentrations to higher levels. It is imperative that the dose administered be one that places the patient in a comfortable as well as a conscious state.

Cooperation

Patient cooperation is one of the primary benefits to the dentist to be gained from conscious sedation. Most patients who are properly selected and prepared will exhibit the greatest degree of cooperation while inhaling N2O concentrations between 30 and 40%. Patients remaining uncooperative at concentrations below that range may become cooperative as the concentration is increased. Those patients failing to become cooperative at concentrations touching 50% should be considered for another form of conscious sedation.

Technique of N2O/O2 Administration3,13–16,23,29–31

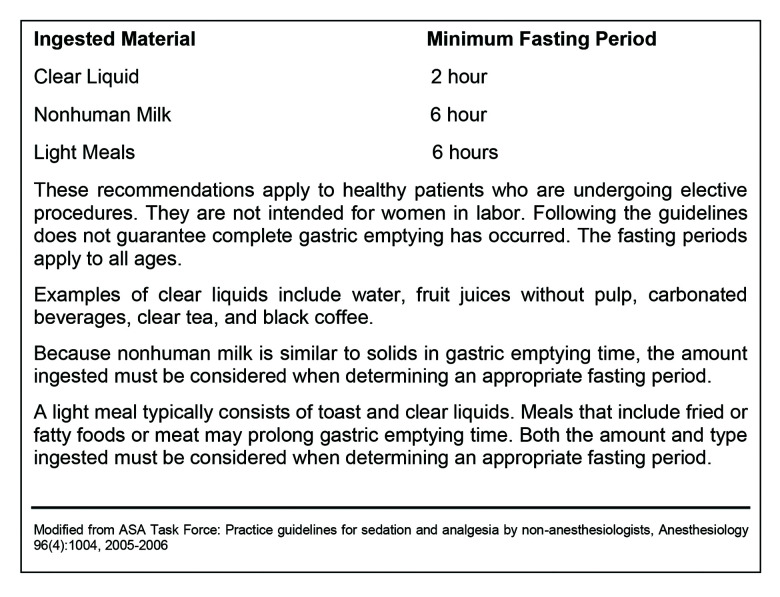

Sound training in the technique and appropriate emergency response is a must for the clinician in charge for the dispensation of analgesic/anxiolytic agents. Fear of unknown leads to phobias, it is thus best to introduce, discuss, and demonstrate to patient the use of N2O–O2 at a pretreatment visit, not at the actual appointment which can backfire. Habituation can relieve fear and promote collaboration between the dentist and the patient. Be honest and clear in your interaction. More open-ended statements must be used, such as “you will feel more comfortable and at ease”, instead of more specific ones like “you will feel tickling in your fingers and toes.” Some patients may not experience suggested signs. At conclusion of the pretreatment appointment, preoperative medications, such as prophylactic antibiotics, antianxiety drugs, or sleep medicines, may be prescribed. Instructions regarding meal/fasting before the actual appointment should be given before dismissing the patient (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preprocedure fasting guidelines

At the beginning of the actual appointment, before starting with the sedation, request the patient to visit the restroom and void if needed. This because when a person is supine, more urine is produced. In case of an urge for urination while the procedure is in progress, the patient must be unsedated, allowed to visit restroom, and resedated again which might not be good for the success of the procedure. Before starting the gases, a thorough review of the medical history and recording of preoperative vital signs must be undertaken. If the patient is a contact lens wearer, have the lenses removed before sedating the patient. This is because if some gas leaks from the mask around the bridge of the nose, it may result in drying of the eyes, and if the patient is wearing contact lenses, it will be irritating to the patient. The chair must be in a semi-reclined position and patient must feel comfortable. Sedation unit must always remain out of sight of the patient, placing it behind the back serves the purpose well. If the patient is able to watch the unit and the controls being adjusted, the positive placebo response can get negated. An appropriate sized nasal hood must be chosen. Most patients usually feel comfortable with a flow rate of 5–6 L/minute. Begin the flow of 100% O2 at 6 L/minute, place the nasal hood over the nose of the patient, and at this point remind the patients that they must breathe through nose as many people continue to breathe through mouth, unless reminded. Patients will not feel suffocated if the hood is placed after starting the flow of gas. Observe the reservoir bag and then the adjustment of flow rate can be performed. The ideal situation for the reservoir bag is that it must pulsate gently with each breath and should not be either overinflated or underinflated. The guidelines recommend introduction of 100% O2 for 1–2 minutes. This must be followed by titration of N2O in 10% intervals. During N2O sedation, the concentration of N2O must not usually exceed 50%. Patient's talking and mouth breathing must be minimized to achieve good sedation. Also make sure that the scavenging vacuum is optimum, too strong a vacuum prevents adequate ventilation of the lungs with N2O. Most of the patients will reach ideal sedation levels between 30 and 40% N2O. Nitrous oxide concentration may be brought down during procedures that are easier (e.g., placement of restorative material) and augmented during more stimulating ones (e.g., administration of local anesthetic, extractions, surgeries). Some of the common signs and symptoms that the patients may experience include light-headedness, tingling (paresthesia) sensation of arms, legs, or oral cavity, and a feeling of warmth, floating, or heaviness. As sedation progresses, the patient's legs and arms relax, and they achieve a “sedated look.” As sedation intensifies, the patient's responses become slower, there is a growing lag time between questions and the patient's answers. Once the patient appears relaxed and signs/symptoms of adequate sedation have been noted, the treatment can commence. If planned procedure continues devoid of any evident signs of discomfort, it can be presumed that sedation is effective. However, it is not uncommon for the patient to make movements, particularly when actual traumatic procedures, such as administration of local anesthetic, are undertaken. In such situations, an upward revision of N2O levels can be performed and the treatment completed. Nitrous oxide is not titrated out of the patient at the end of the procedure, but O2 increased to its preoperative flow rate of 5 to 6 L/minute and N2O flow is simply turned to 0 L/minute (0%). One hundred percent O2 should be administered until the patient has reverted to pretreatment status. The N2O can be terminated few minutes before the anticipated culmination of the procedure. Advantages of early termination of N2O are many. The discharge of the patient from office is hastened. Positive placebo response takes over in most cases and if not informed, patients feel as relaxed as they were when N2O was being administered. The dentist must be sure that complete recovery has happened prior to discharge of the patient. Most patients recover fully following inhalation of 100% O2 for at least 3–5 minutes. The patient must return to pretreatment receptiveness before discharge. If dentist is satisfied, (adult) patient is permitted to leave the office unescorted. This is the only technique of sedation in which unescorted dismissal of adult patients may be considered.

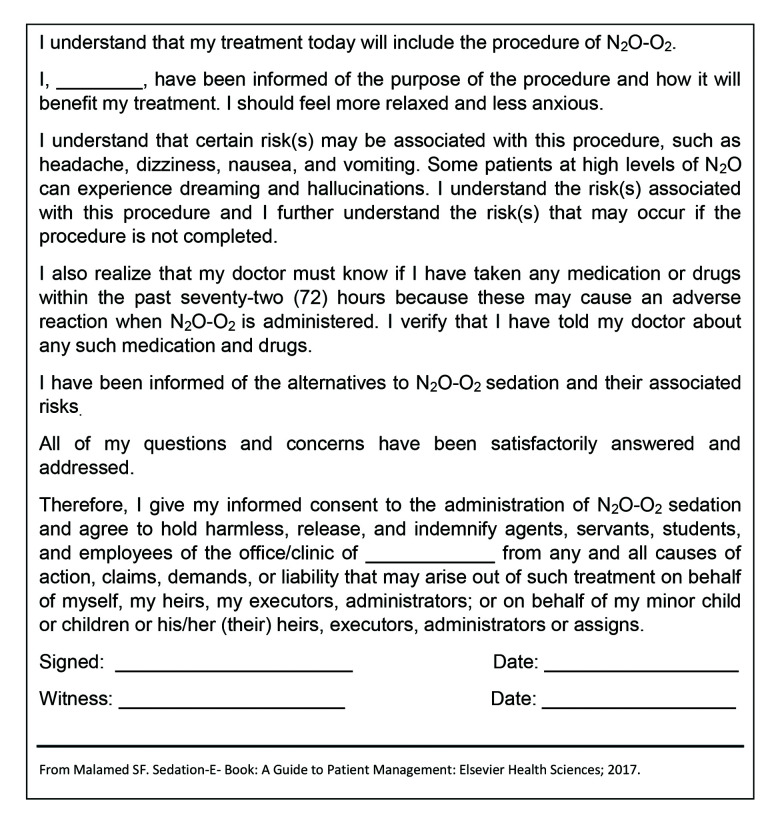

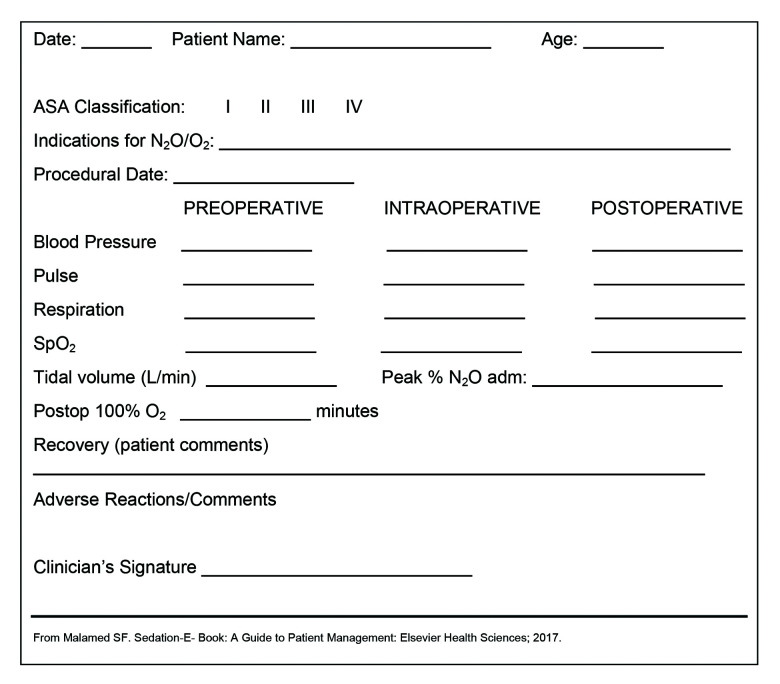

Documentation3,5,13,16,23,30,32

Psychological and physical evaluation must be performed and documented. This includes completion of a health history questionnaire. Medical consultation must be sought if required and comments documented.30 Assessment of patient risk as per the ASA Physical Status Classification must be documented in patient's record.31 Preprocedure fasting guidelines/dietary precautions must be provided5 (Fig. 1). In case of minors, the informed consent must be acquired from the parent and documented in the patient's record prior to administration of N2O–O231 (Fig. 2). Patient's record should include indication for use of N2O–O2 inhalation, N2O dosage (i.e., percentage of N2O–O2 and/or flow rate), duration of the procedure, and posttreatment oxygenation duration and procedure31 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Informed consent for N2O–O2 sedation

Fig. 3.

N2O/O2 sedation record

Review of Dental Procedures Possible Under NOIS27,28,30

Other than pediatric dentistry where NOIS is being used in a variety of situations, the technique has found wide acceptance in adult dentistry as well. In restorative dentistry, it is being used during initial dental examination, restorative clinical work, cementation and removal of provisional crowns and bridges, cementation of prosthesis and occlusal adjustment. It is popular among the endodontists and is of particular help in delivering a profound pulpal anesthesia while gaining endodontic access. In periodontics, it is being used during the probing/initial examination in cases with significant periodontal disease. Besides this, the periodontists use NOIS during procedures, such as scaling, root planning and curettage as well as emergency management of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Stress levels are reduced, and patient comfort is greatly enhanced during the NOIS-assisted periodontal surgeries of any duration. There are huge benefits of NOIS in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Surgical procedures that are longer in duration, management of abscesses, and postoperative complications are greatly benefitted under sedation. Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation eliminates or minimizes the gag reflex and helps reduce the discomfort associated with placement of intraoral films/sensors, a huge benefit in oral radiological techniques. Patients having limitation of anatomy, such as shallow palates, exostosis, or trauma benefit from this modality.

Multidisciplinary Applications of NOIS31

Besides dentistry, NOIS has found takers in a multitude of disciplines, such as emergency medicine (pre-hospital care in ambulance, and in the emergency departments in hospitals), obstetrics and gynecology (gynecologic laparoscopy, labor, and delivery), dermatology (hair transplantation, liposuction, skin treatments, and cancer surgeries), ophthalmology (eye surgery, implant surgery), cryosurgery, psychiatry, and psychology (depression, schizophrenia, hyperactivity, sex research), radiology (painful procedures), endoscopy (gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, bronchoscopy), addiction withdrawal (alcohol, pentazocine, nicotine, and marijuana), podiatry (ambulatory foot surgeries), pediatrics (painful and anxiety-producing situations, amnestic and hypnosuggestive properties), acute myocardial infraction (reduced pain and anxiety, benefits of supplemental O2), and terminally ill patients (used in cancer or terminal illness to improve quality of life).

Conclusion

Nitrous oxide–oxygen inhalation sedation has been the primary technique in the management of dental fears and anxiety for >170 years and remains so today. It also enhances the effect of local anesthetics thus helping in achieving a profound anesthesia. Patient's pain threshold increases as well. When administered under proper monitoring and with well-maintained equipment, the technique has an extremely high success rate.14 On the contrary, the rate of adverse effects and complications remains very low; there is not even a single reported case of death attributed to NOIS. Besides the three major indications for the use of inhalation sedation—anxiety, medically compromised patient, and gagging, there is a range of uses for this modality in other fields of dentistry; this includes procedures that are considered too minor or too short to employ sedation. Besides pediatric dentistry, the NOIS is of immense benefit for the adult and geriatric patients. As the average life spans increase and population ages, there will be a larger pool of potential patients who stand to benefit from a safe, noninvasive fully reversible agent, such as N2O. Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation has unique and distinct advantages that are not easily matched. As the patients become more demanding, expecting gentler, painless, and anxiety free dentistry, the N2O inhalation sedation will find broader applications and more takers to reduce anxiety and provide pain relief to our patients.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Haridas RP. Horace Wells’ demonstration of nitrous oxide in Boston. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(5):1014–1022. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a771ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark MS, Campbell SA, Clark AM. Technique for the administration of nitrous oxide/oxygen sedation to ensure psychotropic analgesic nitrous oxide (PAN) effects. Int J Neurosci. 2006;116(7):871–877. doi: 10.1080/00207450600754012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ADA American. Dental Association. Guidelines for the use of sedation and general anesthesia by dentists. ADA House Delegat adop. 2007;2007:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Council O. Guideline on use of nitrous oxide for. pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent. 2013;36(5):174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):1004–1017. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colleges AOMR. Safe Sedation Practice for Healthcare Procedures. Standards and Guidance. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges London; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee CHSCSDA, Poswillo DE. General anaesthesia, sedation and resuscitation in dentistry: report of an expert working party: Department of Health; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cravero JP. Springer; 2015. Sedation Policies, recommendations, and guidelines across the Specialties and CONTINENTS. Pediatric Sedation Outside of the Operating Room. pp. 17–31. p. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallonsten A-L, Jensen B, Raadal M, et al. EAPD guidelines on sedation in paediatric dentistry. european academy of paediatric dentistry. http://wwweapdgr/dat/5CF03741/file.pdf im internet. Stand. 2013;7:12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holroyd I. Intercollegiate advisory committee for sedation in dentistry: review of the guidelines published in april 2015. Dent Update. 2015;42(8):704–708. doi: 10.12968/denu.2015.42.8.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holroyd I. Conscious sedation in pediatric dentistry. A short review of the current UK guidelines and the technique of inhalational sedation with nitrous oxide. Pediatric anesthesia. 2008;18(1):13–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sury M, Bullock I, Rabar S, et al. Sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341(dec16 1):c6819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association AD. Chicago: ADA; 2007. Guidelines for teaching pain control and sedation to dentists and dental students. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malamed SF, Clark MS. Nitrous oxide-oxygen: a new look at a very old technique. CDA. 2003;31(5):397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An SY, Seo KS, Kim S, et al. Developmental procedures for the clinical practice guidelines for conscious sedation in dentistry for the Korean academy of dental sciences. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2016;16(4):253–261. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2016.16.4.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coté CJ, Wilson S. American academy of pediatrics; american academy of pediatric dentistry. guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients before, during, and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: Update Pediatrics 2016. 2016;138(1):e20161212. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eli I, Uziel N, Baht R, et al. Antecedents of dental anxiety: learned responses versus personality traits. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(3):233–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henning Abrahamsson K, Berggren U, Hakeberg M, et al. Phobic avoidance and regular dental care in fearful dental patients: a comparative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59(5):273–279. doi: 10.1080/000163501750541129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maggirias J, Locker D. Five-year incidence of dental anxiety in an adult population. Commun Dent Health. 2002;19(3):173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong K, Tan J, Chong W, et al. Use of sedation in dentistry. Singapore Dent J. 2000;23(1 Suppl):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ragnarsson B, Arnlaugsson S, Karlsson KÖ, et al. Dental anxiety in Iceland: an epidemiological postal survey. Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61(5):283–288. doi: 10.1080/00016350310005844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malamed SF. Emergency medicine in pediatric dentistry: preparation and management. CDA J. 2003;31(10):749–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yee R, Wong D, Chay PL, et al. Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation in dentistry: an overview of its applications and safety profile. Singapore Dent J. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1142/S2214607519500019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryding HA, Murphy J. Use of nitrous oxide and oxygen for conscious sedation to manage pain and anxiety. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor) 2007;73(8):711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kharouba J, Somri M, Hadjittofi C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of nitrous oxide as a sedative agent at 60% and 70% Compared to 50% concentration in. pediatric dentistry setting. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2020;44(1):60–65. doi: 10.17796/1053-4625-44.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ergüven SS, Delilbaşi EA, Işik B, et al. The effects of conscious sedation with nitrous oxide/oxygen on cognitive functions. Turkish J Med Sci. 2016;46(4):997–1003. doi: 10.3906/sag-1504-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yun S, Xin-he W, Rong-xiang S, et al. Application of nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation sedation in tooth extraction of elderly patients with hypertension. Shanghai Journal of Stomatology. 2013;22(3):302–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandhu G, Khinda PK, Gill AS, et al. Comparative evaluation of stress levels before, during, and after periodontal surgical procedures with and without nitrous oxide-oxygen inhalation sedation. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017;21(1):21. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_226_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duarte LTD, Neto GFD, Mendes FF. Nitrous oxide use in children. Brazil J Anesthesiol. 2012;62(3):451–467. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7094(12)70145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malamed SF. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017. Sedation-E-Book: A Guide to Patient Management. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark MS, Brunick AL. Handbook of nitrous oxide and oxygen sedation. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behrman RE, Vaughan IIIVC. WB Saunders company; 1983. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donaldson M, Donaldson D, Quarnstrom FC. Nitrous oxide-oxygen administration: when safety Donaldson features no longer are safe. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(2):134–143. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]