Abstract

Atrogin-1 and muscle RING finger 1 (MuRF1) are ubiquitin ligases specifically expressed during skeletal muscle atrophy and mediate muscle protein degradation. In contrast, PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α), which is a master regulator of mitochondrial biosynthesis, protects skeletal muscle from atrophy. Pyrimidine nucleoside 5′-monophosphates, such as cytidine 5′-monophosphate (5′-CMP) and uridine 5′-monophosphate (5′-UMP), induce PGC-1α expression and promote myotube formation in mouse C2C12 cells. In this study, we determined the effect of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP on muscular atrophy in C2C12 myotube cells. 5′-UMP decreased Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels that were upregulated by dexamethasone treatment. 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP ameliorated dexamethasone-mediated atrophy in C2C12 myotubes. Furthermore, the combination of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP further alleviated dexamethasone-mediated atrophy. In addition, cytidine and uridine, the precursors of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, markedly ameliorated dexamethasone-mediated atrophy. Considering nucleotide metabolism and absorption, the active metabolites underlying the observed effects of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP appear to be cytidine and uridine. Our results indicate that 5′-CMP alleviates muscle atrophy by activating PGC-1α and differentiation, and 5′-UMP alleviates muscle atrophy by suppressing the activation of the myolytic system, whereas the combined use of both enhances the muscle atrophy inhibitory effect. 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP may be an effective and safe treatment for muscular atrophy.

Keywords: Cytidine 5′-monophosphate, Uridine 5′-monophosphate, Nutrition, Muscle atrophy, E3 ubiquitin ligase, PGC-1α

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

5′-UMP decreased Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels that were upregulated by dexamethasone treatment in C2C12 myotubes.

-

•

5′-CMP and 5′-UMP ameliorated dexamethasone-mediated atrophy in C2C12 myotubes.

-

•

The combined use of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP enhances the muscle atrophy inhibitory effect.

-

•

Cytidine and uridine, nucleosides corresponding to 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, notably ameliorated dexamethasone-mediated atrophy.

Abbreviations

- 5′-CMP

Cytidine 5′-monophosphate

- 5′-UMP

Uridine 5′-monophosphate

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- BS

Bovine serum

- MuRF1

Muscle RING finger 1

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α

1. Introduction

Muscle atrophy occurs when the rate of protein degradation exceeds the rate of protein synthesis due to a variety of conditions, including aging, disuse, starvation, cancer, diabetes, and glucocorticoid use [1]. Compounds that block proteolysis and/or activate protein synthesis may represent beneficial treatments for skeletal muscle atrophy.

Proteolysis of skeletal muscle is primarily regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, Atrogin-1 and muscle RING finger 1 (MuRF1), are specifically expressed during skeletal muscle atrophy and mediate muscle protein degradation [2].

The atrophy-associated ubiquitin ligases are regulated by specific transcription factors such as FoxO3, which is negatively regulated by the IGF-1/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [3]. Dexamethasone is a synthetic glucocorticoid with anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant properties. Dexamethasone acts via glucocorticoid receptors to alter transcription of target genes. REDD1 and KLF15 are direct target genes of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in skeletal muscle. As well as REDD1, KLF15 inhibits mTOR activity, but via a distinct mechanism involving BCAT2 gene activation. Moreover, KLF15 upregulates the expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligases Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 genes and negatively modulates myofiber size [4]. MuRF1 knockout mice are resistant to dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy [5].

Mitochondria are important in maintaining muscle function. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) plays a central role in the regulation of mitochondrial biosynthesis. PGC-1α protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 activity and atrophy-specific gene transcription [6]. Upregulation of PGC-1α is decreased in dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy and increased PGC-1α expression ameliorates the degradative processes associated with muscle atrophy in mice [7].

Ribonucleotides are the basic components for RNA and are indispensable for life. Nucleotides can be provided by de novo synthesis, but may be deficient under various stress conditions including rapid growth in infant and diseases. Nucleotides are more abundant in breast milk than in bovine milk or bovine milk powder, whereas many infant formulas are supplemented with nucleotides. Therefore, dietary nucleotides are considered essential to withstand various physiological stresses [8,9].

Ribonucleotides are not only necessary for RNA synthesis, but also exert a variety of bioactivities, such as liver protection, immune activation, and brain activation [[10], [11], [12]].

In a study of biological activity related to muscle and exercise, it has been reported that rats treated intramuscularly with a mixture of the pyrimidine nucleotides, cytidine 5′-monophosphate (5′-CMP) and uridine monophosphate (5′-UMP), have improved endurance. The glucose levels in hind legs is significantly higher in treated rats [13]. In a previous study, we demonstrated that 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP can enhance the expression of PGC-1α and enhance myotube formation in mouse C2C12 cells [14]. Endogenous pools of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP decrease with age in rats [15]; thus, a reduction in 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP levels may be associated with sarcopenia, an age-related muscular atrophy. Therefore, we aimed to determine the effects of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP on dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in C2C12 myotubes and its putative mechanism.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and differentiation

Cell culture was performed as previously described [14]. Mouse C2C12 myoblasts (RIKEN BRC, RCB0987) were obtained from the RIKEN BRC and grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), low glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To initiate differentiation, the media was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated bovine serum (BS), 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. The medium was changed at least every other day.

2.2. Dexamethasone-induced Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression in C2C12 myotubes

The expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 were evaluated with slight modifications to previously published methods [16]. Briefly, C2C12 cells were grown to 70–90% confluence and differentiated into myotubes over 6 days. The myotubes were treated with 5′-CMP disodium salt (1, 5 mM), 5′-UMP disodium salt (1, 5 mM), cytidine (10, 100 μM) or uridine (10, 100 μM) (YAMASA, Chiba, Japan) for 48 h. Subsequently, the myotubes were cotreated with 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex) for 24 h.

2.3. Dexamethasone-induced C2C12 myotube atrophy model for measurement of myotube diameter

To evaluate myotube diameter, C2C12 cells were grown to 70–90% confluence and differentiated into myotubes over 4 days. Subsequently, the myotubes were treated with 100 μM Dex and cotreated with 5′-CMP disodium salt (1, 5 mM), 5′-UMP disodium salt (1, 5 mM), cytidine (10, 100 μM), uridine (10, 100 μM), mixture of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP (different concentrations and ratios, shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 4) or mixture of cytidine and uridine (various concentrations and ratios, shown in Fig. 4) for 3 days.

Fig. 2.

Both 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP ameliorates dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy

(A) Images of the C2C12 myotubes. The myotubes were treated with 100 μM Dex and various concentrations of 5′-CMP or 5′-UMP for 3 days, and then photographed by phase contrast microscopy. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Diameter of the C2C12 myotubes. The myotubes were photographed by phase contrast microscope (100× magnification) using five culture fields near the center of the well. The top 10 thickest myotubes in the image were selected visually and the diameters were measured using ImageJ software. The average diameter of 50 myotubes for each well was then determined. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6) *P < 0.05 compared with dexamethasone-treated control.

Fig. 4.

Both cytidine and uridine effectively ameliorate dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy.

2.4. Total RNA isolation and quantitative RT–PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed as previously described [14]. Total RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The mRNA was reverse transcribed using the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) and analyzed using a Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) and GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, USA). The PCR amplification consisted of an activation step 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing and extension at 60 °C for 1 min. The expression level of the target genes was normalized to β-actin. The primer sequences used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primers used in this study.

| Genes | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Atrogin-1 | 5′- CAGCTTCGTGAGCGACCTC -3′ | 5′- GGCAGTCGAGAAGTCCAGTC -3′ |

| MuRF1 | 5′- GTGTGAGGTGCCTACTTGCTC -3′ | 5′- GCTCAGTCTTCTGTCCTTGGA -3′ |

| β-Actin | 5′- CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAAC -3′ | 5′- ATGGAGCCACCGATCCACA -3′ |

2.5. Measurement of myotube diameter

Measurement of myotube diameter was performed as previously described [14]. Myotubes from five culture fields located near the center of the wells were photographed under an optical microscope (100× magnification). In each field, the top 10 thickest myotubes were selected visually and the diameter was measured using ImageJ software. A total of 50 myotubes were analyzed from each well and the average diameter was calculated.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Student's t-test was used to compare the mean values of the Dex-untreated group with the mean values of the Dex-treated control group. A one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's test, was used to compare the mean of Dex-treated control group with the means of Dex + test substance treated groups. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP14 software (SAS Institute, Cary, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. 5′-UMP but not 5′-CMP inhibits Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression in dexamethasone-treated C2C12 myotubes

Endogenous pools of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP decrease with age in rats; thus, a reduction of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP may be associated with sarcopenia. We evaluated the effects of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP on the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1, which are muscle atrophy-specific ubiquitin ligases that play an important role in muscle atrophy. Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels were significantly increased by 1 μM dexamethasone treatment. We found that 5 mM 5′-UMP significantly downregulated the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner (1 and 5 mM). In contrast, 5′-CMP (1 and 5 mM) did not significantly downregulate Atrogin-1 or MuRF1 mRNA (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

5′-UMP but not 5′-CMP inhibits the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1

(A) Relative Atrogin-1 mRNA levels. (B) Relative MuRF1 mRNA levels. The expression of each gene was normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. The relative value to the mRNA levels of the dexamethasone-untreated control is presented. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with the dexamethasone-treated control.

3.2. Both 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP ameliorate dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy

We determined the effect of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP on dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy by measuring myotube diameter. The diameter of the myotubes was significantly reduced by 100 μM dexamethasone treatment. Both 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP alleviated dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy; however, these effects did not occur in a dose-dependent manner and even the highest dose (5 mM) could not completely counteract the effect of dexamethasone (Fig. 2A and B). Compared with 5′-UMP, 5′-CMP was more effective at inducing PGC-1α expression [14], whereas only 5′-UMP inhibited muscle atrophy-specific ubiquitin ligase. Thus, 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP may inhibit muscle atrophy by different mechanisms. To determine the muscle atrophy inhibitory effect by combining 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, a total of 1 mM of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP were added to the cells at different ratios. The combined treatment with 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP ameliorated dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy markedly compared with either 5′-CMP or 5′-UMP alone. In particular, the combination of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP at a ratio of 1:1 (0.5 mM and 0.5 mM) resulted in the greatest amelioration of dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy.

3.3. Uridine, the corresponding nucleoside of 5′-UMP, inhibits the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in dexamethasone-treated C2C12 myotubes

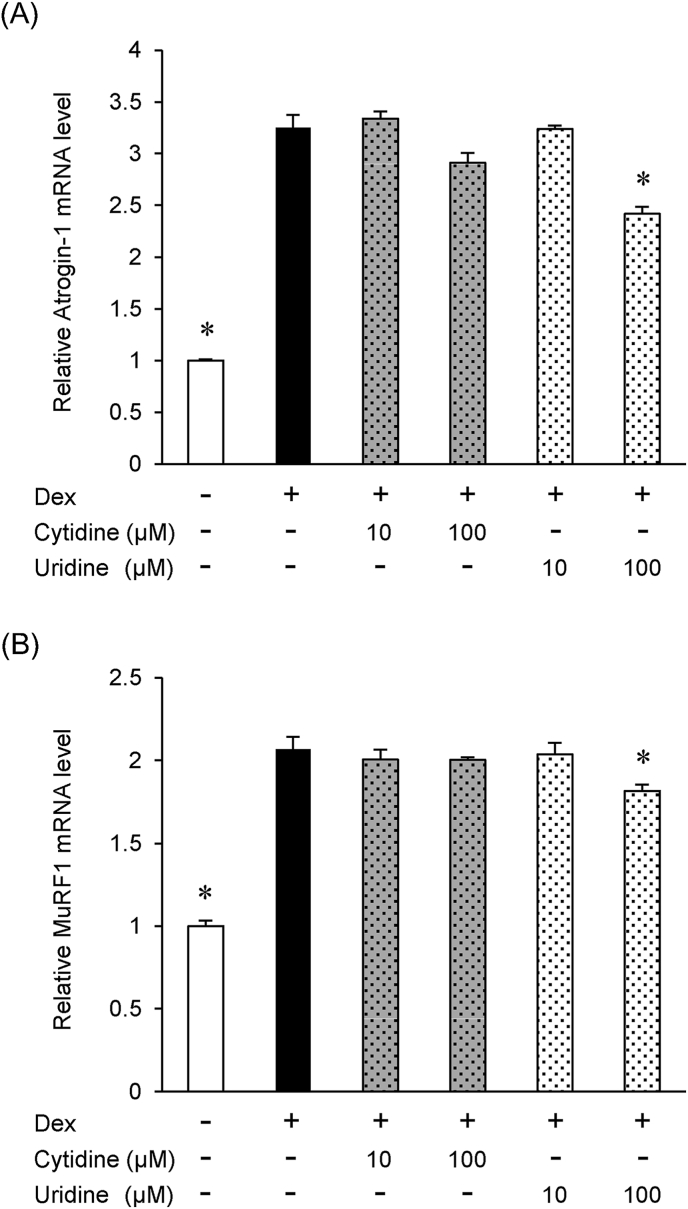

Nucleotides are hydrolyzed to nucleosides in the digestive tract and absorbed as nucleosides [17,18]. Because serum contains 5′-nucleotidase, nucleotides in the medium are degraded to nucleosides [19]. To evaluate the possibility that nucleosides are the active metabolites, we examined the effects of cytidine and uridine, the nucleosides corresponding to 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, on Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. We evaluated the effects of cytidine and uridine, which are nucleosides corresponding to 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, on Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. We found that cytidine (10 and 100 μM) did not downregulate either Atrogin-1 or MuRF1 expression; however, 100 μM uridine significantly downregulated both Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner (10 and 100 μM).

3.4. Both cytidine and uridine ameliorate dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy

We determined the effect of cytidine and uridine on dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy by measuring myotube diameter. Cytidine (1 mM) and uridine (1 mM) ameliorated dexamethasone-induced muscular atrophy to a greater extent compared with 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP. Furthermore, the combination of cytidine and uridine ameliorated dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy more effectively than the combination of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP (Fig. 4).

Diameter of the C2C12 myotubes. The myotubes were photographed by phase contrast microscopy (100× magnification) within five culture fields near the center of the well. The top 10 thickest myotubes in the photograph were selected visually and the diameters were measured using ImageJ software. The average diameter of 50 myotubes from each well was then determined. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6) *P < 0.05 compared with the dexamethasone-treated control.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated a novel role for 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP in C2C12 myotubes undergoing atrophy following dexamethasone treatment. Ribonucleotides are considered conditionally essential nutrients because they tend to be deficient under conditions of stress [9]. Endogenous pools of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP decrease with age in rats, whereas rats ingesting a mixture of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP endured long-term exercise on a treadmill [13]. In our previous study, we demonstrated that 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP enhance the expression of PGC-1α and myotube formation in mouse C2C12 cells [14].

Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are muscle atrophy-specific ubiquitin ligases that play an important role in muscle atrophy [2]. Some active components derived from plants, such as fucoxanthin, matrine, and myricanol can alleviate muscle atrophy induced by dexamethasone, possibly by inhibiting muscle atrophy-specific ubiquitin ligases [16,20,21]. Our data indicate that 5′-CMP did not inhibit Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression; however, 5′-UMP inhibited the expression of both genes in dexamethasone-treated C2C12 myotubes.

In contrast, both 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP alleviate dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. In our previous study, we found that 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, particularly 5′-CMP, enhances the expression of PGC-1α and promotes myotube formation in mouse C2C12 cells. PGC-1α protects skeletal muscle from dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy [22]. The inhibitory effect of 5′-CMP on muscle atrophy is believed to occur through activation of PGC-1α and its differentiation promoting effect. However, the effects of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP did not occur in a dose-dependent manner and even the highest dose (5 mM) could not completely counteract the effects of dexamethasone (Fig. 2A and B). Therefore, we evaluated the effect of the combination of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP, which may have different mechanisms of action on muscle atrophy. Our data indicated that the combination of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP alleviated dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy more effectively compared with 5′-CMP alone or 5′-UMP alone.

Nucleotides are hydrolyzed to nucleosides in the digestive tract and absorbed as nucleosides [17,18]. Because serum contains 5′-nucleotidase, it is possible that 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP are degraded to nucleosides in the medium and exhibit biological activity. To evaluate the possibility that nucleosides are the active metabolites, we examined the effects of cytidine and uridine, the nucleosides corresponding to 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP.

Our data showed that cytidine did not inhibit the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1, but uridine inhibited the expression of both in dexamethasone-treated C2C12 myotubes and at lower concentrations compared with 5′-UMP (Fig. 3). Moreover, both cytidine and uridine potently alleviated dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy compared with 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP (Fig. 4). These results indicate that cytidine and uridine are the active metabolites of the effects observed with 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP.

Fig. 3.

Uridine inhibits the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1

(A) Relative Atrogin-1 mRNA levels. (B) Relative MuRF1 mRNA levels. Gene expression was normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. The relative value to the mRNA level of the dexamethasone-untreated control is presented. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with the dexamethasone-treated control.

A limitation of this study is the lack of further detailed analyses, such as Western blot analyses of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1. In addition, the pretreatment of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP in the evaluation of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression allows us to know about their protective role against the Dex effects, but not about their role in muscle recovery after Dex-treatment. Another limitation is that the detailed mechanisms with which cytidine and uridine inhibit muscle atrophy have not been elucidated. It has not been clarified that cytidine, uridine, or their metabolites (nucleobases, nucleotides, sugar-nucleotides, CDP-choline, etc.) act on receptors or sensors to alleviate muscle atrophy. Therefore, further in vitro studies are warranted to clarify the above issues.

Besides, the muscle atrophy inhibitory effects of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP have not been verified in animals or humans. Additional studies are required to verify the effect of 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP on muscle atrophy in animals or humans.

In conclusion, our results indicate that 5′-CMP may ameliorate muscle atrophy by activating PGC-1α and promoting differentiation and 5′-UMP alleviates muscle atrophy by inhibiting the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1. The combined use of both enhances the muscle atrophy inhibitory effect. Furthermore, cytidine and uridine showed stronger effects than 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP. Because orally ingested 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP are absorbed as cytidine and uridine with high availability, 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP are expected to be effective with oral intake. Therefore 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP may be an effective and safe treatment for muscle atrophy.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Kosuke Nakagawara: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization.

Chieri Takeuchi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation.

Kazuya Ishige: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: All authors are employees of YAMASA Corporation. All authors filed the patent related to this work. The patent has not been published and issued yet. YAMASA Corporation provided the nucleotides and nucleosides.

Acknowledgements

Mouse C2C12 myoblasts (RIKEN BRC, RCB0987) was provided by RIKEN BRC which is participating in the National BioResource Project of the MEXT/AMED, Japan.

References

- 1.Sartori Roberta, Romanello Vanina, Sandri Marco. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: implications in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2021 Jan 12;12(1):330. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodine S.C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V.K., Nunez L., Clarke B.A., Poueymirou W.T., Panaro F.J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z.Q., Valenzuela D.M., DeChiara T.M., Stitt T.N., Yancopoulos G.D., Glass D.J. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy Science. 2001 Nov 23;294(5547):1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stitt Trevor N., Drujan Doreen, Clarke Brian A., Frank Panaro, Timofeyva Yekatarina, Kline William O., Gonzalez Michael, Yancopoulos George D., Glass David J. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2004 May 7;14(3):395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu Noriaki, Yoshikawa Noritada, Ito Naoki, Maruyama Takako, Suzuki Yuko, Takeda Sin-ichi, Nakae Jun, Tagata Yusuke, Nishitani Shinobu, Takehana Kenji, Sano Motoaki, Fukuda Keiichi, Suematsu Makoto, Morimoto Chikao, Tanaka Hirotoshi. Crosstalk between glucocorticoid receptor and nutritional sensor mTOR in skeletal muscle. Cell Metabol. 2011 Feb 2;13(2):170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baehr Leslie M., Furlow J David, Sue C. Bodine Muscle sparing in muscle RING finger 1 null mice: response to synthetic glucocorticoids. J. Physiol. 2011 Oct 1;589(Pt 19):4759–4776. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212845. Published online 2011 Aug 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandri Marco, Lin Jiandie, Handschin Christoph, Yang Wenli, Arany Zoltan P., Lecker Stewart H., Goldberg Alfred L., Spiegelman Bruce M. PGC-1alpha protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006 Oct 31;103(44):16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607795103. Epub 2006 Oct 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenz Tina, Rossi Susana G., Rotundo Richard L., Bruce M Spiegelman, Moraes Carlos T. Increased muscle PGC-1alpha expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009 Dec 1;106(48):20405–20410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911570106. Epub 2009 Nov 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Thorell L., Sjöberg L.B., Hernell O. Nucleotides in human milk: sources and metabolism by the newborn infant. Pediatr. Res. 1996 Dec;40(6):845–852. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199612000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez-Pozo A. A Gil Nucleotides as semiessential nutritional components. Br. J. Nutr. 2002 Jan;87(Suppl 1):S135–S137. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess Jennifer R., Greenberg Norman A. The role of nucleotides in the immune and gastrointestinal systems: potential clinical applications Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2012 Apr;27(2):281–294. doi: 10.1177/0884533611434933.Epub.2012.Mar.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez María José, Sánchez-Medina Fermín, Torres Maribel, Gil Angel, Suárez Antonio. Dietary nucleotides enhance the liver redox state and protein synthesis in cirrhotic rats. J. Nutr. 2004 Oct;134(10):2504–2508. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teather Lisa A., Wurtman Richard J. Chronic administration of UMP ameliorates the impairment of hippocampal-dependent memory in impoverished rats. J. Nutr. 2006 Nov;136(11):2834–2837. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.11.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gella A., Ponce J., Cussó R., Durany N. Effect of the nucleotides CMP and UMP on exhaustion in exercise rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2008 Mar;64(1):9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF03168230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawara Kosuke, Takeuchi Chieri, Ishige Kazuya. 5'-CMP and 5'-UMP promote myogenic differentiation and mitochondrial biogenesis by activating myogenin and PGC-1α in a mouse myoblast C2C12 cell line. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2022 Jul 15;31 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2022.101309.eCollection.2022.Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolla R.I., Miller J.K. Endogenous nucleotide pools and protein incorporation into liver nuclei from young and old rats. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1980 Feb;12(2):107–118. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(80)90087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Li, Chen Linlin, Wan Lili, Huo Yan, Huang Jinlu, Li Jie, Lu Jin, Xin Bo, Yang Quanjun, Guo Cheng. Matrine improves skeletal muscle atrophy by inhibiting E3 ubiquitin ligases and activating the Akt/mTOR/FoxO3α signaling pathway in C2C12 myotubes and mice. Oncol. Rep. 2019 Aug;42(2):479–494. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7205.Epub.2019.Jun.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Buren C.T., Kulkarni A.D., Rudolph F.B. The role of nucleotides in adult nutrition. J. Nutr. 1994;124:160S–164S. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.suppl_1.160S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young James D., Yao Sylvia Y.M., Baldwin Jocelyn M., Cass Carol E., Baldwin Stephen A. The human concentrative and equilibrative nucleoside transporter families, SLC28 and SLC29. Mol. Aspect. Med. 2013;34:529–547. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dixon T.F., Purdom M. Serum 5-nucleotidase. J. Clin. Pathol. 1954;7:341–343. doi: 10.1136/jcp.7.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao Zhiyin, Chen Jinliang, Chen Qiunan, Yang Yunfei, Qian Xiao. Fucoxanthin rescues dexamethasone induced C2C12 myotubes atrophy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021 Jul;139 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111590. Epub 2021 Apr 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen Shengnan, Liao Qiwen, Liu Jingxin, Pan Ruile, Lee Simon Ming-Yuen, Lin Ligen. Myricanol rescues dexamethasone-induced muscle dysfunction via a sirtuin 1-dependent mechanism. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019 Apr;10(2):429–444. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12393. Epub 2019 Feb 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Yujie, Chen Ka, Ren Qingbo, Yi Long, Zhu Jundong, Zhang Qianyong, Mi Mantian. Dihydromyricetin attenuates dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy by improving mitochondrial function via the PGC-1α pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;49(2):758–779. doi: 10.1159/000493040. Epub 2018 Aug 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]