Abstract

Objective

Noncompressible torso hemorrhage is a high-mortality injury. We previously reported improved outcomes with a retrievable rescue stent graft to temporize aortic hemorrhage in a porcine model while maintaining distal perfusion. A limitation was that the original cylindrical stent graft design prohibited simultaneous vascular repair, given the concern for suture ensnarement of the temporary stent. We hypothesized that a modified, dumbbell-shaped design would preserve distal perfusion and also offer a bloodless plane in the midsection, facilitating repair with the stent graft in place and improve the postrepair hemodynamics.

Methods

In an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved terminal porcine model, a custom retrievable dumbbell-shaped rescue stent graft (dRS) was fashioned from laser-cut nitinol and polytetrafluoroethylene covering and compared with aortic cross-clamping. Under anesthesia, the descending thoracic aorta was injured and then repaired with cross-clamping (n = 6) or dRS (n = 6). Angiography was performed in both groups. Operations were divided into phases: (1) baseline, (2) thoracic injury with either cross-clamp or dRS deployed, and (3) recovery, after which the clamp or dRS were removed. Target blood loss was 22% to simulate class II or III hemorrhagic shock. Shed blood was recovered with a Cell Saver and reinfused for resuscitation. Renal artery flow rates were recorded at baseline and during the repair phase and reported as a percentage of cardiac output. Phenylephrine pressor requirements were recorded.

Results

In contrast with cross-clamped animals, dRS animals demonstrated both operative hemostasis and preserved flow beyond the dRS angiographically. Recovery phase mean arterial pressure, cardiac output, and right ventricular end-diastolic volume were significantly higher in dRS animals (P = .033, P = .015, and P = .012, respectively). Whereas distal femoral blood pressures were absent during cross-clamping, among the dRS animals, the carotid and femoral MAPs were not significantly different during the injury phase (P = .504). Cross-clamped animals demonstrated nearly absent renal artery flow, in contrast with dRS animals, which exhibited preserved perfusion (P<.0001). Femoral oxygen levels (partial pressure of oxygen) among a subset of animals further confirmed greater distal oxygenation during dRS deployment compared with cross-clamping (P = .006). After aortic repair and clamp or stent removal, cross-clamped animals demonstrated more significant hypotension, as demonstrated by increased pressor requirements over stented animals (P = .035).

Conclusions

Compared with aortic cross-clamping, the dRS model demonstrated superior distal perfusion, while also facilitating simultaneous hemorrhage control and aortic repair. This study demonstrates a promising alternative to aortic cross-clamping to decrease distal ischemia and avoid the unfavorable hemodynamics that accompany clamp reperfusion. Future studies will assess differences in ischemic injury and physiological outcomes.

Clinical Relevance

Noncompressible aortic hemorrhage remains a high-mortality injury, and current damage control options are limited by ischemic complications. We have previously reported a retrievable stent graft to allow rapid hemorrhage control, preserved distal perfusion, and removal at the primary repair. The prior cylindrical stent graft was limited by the inability to suture the aorta over the stent graft owing to risk of ensnarement. This large animal study explored a dumbbell retrievable stent with a bloodless plane to allow suture placement with the stent in place. This approach improved distal perfusion and hemodynamics over clamp repair and heralds the potential for aortic repair while avoiding complications.

Keywords: Aortic trauma, Endovascular, Aortic cross-clamp, Temporary stent, Torso hemorrhage

Article Highlights.

-

•

Type of Research: Porcine study

-

•

Key Findings: Comparison of a porcine model of aortic cross-clamp (n = 6) vs a dumbbell-shaped rescue stent (dRS) (n = 6) revealed comparable ability to perform open patch repair of a traumatic aortic injury. The dRS conferred dramatic improvement in distal perfusion (average 74 mm Hg higher mean arterial pressure), significant improvement in distal oxygen delivery, improved renal perfusion (8.4-fold), and improved postrepair hemodynamics

-

•

Take Home Message: A dRS offers damage control of traumatic aortic hemorrhage in a porcine large animal model, while allowing simultaneous sutured repair, improved distal perfusion, and superior postrepair hemodynamics.

Traumatic injuries remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States,1 with noncompressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH) as one of the leading causes of death in both civilian and military trauma settings.2 Rapid exsanguination from an injury to the great vessels is compounded by the futility of traditional first aid adjuncts such as manual compression, because the injuries are located deep within the rigid torso. Particularly in the austere environment, such as the battlefield or active civilian shooter scenario, delays in care resulting from inadequate local resources for major aortic repair, a hostile environment or terrain, and transport to higher levels of care remain important barriers to survival.3,4 Management options for NCTH include resuscitative thoracotomy with aortic cross-clamping, as well as endovascular options such as resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA).1,2,4, 5, 6 Because fatal exsanguination occurs rapidly, open clamp repair is logistically impractical; immediate expertise, imaging, and surgical inventory are frequently unavailable in the early period after injury. Meanwhile, minimally invasive REBOA has offered rapid aortic control without major surgical tools or expertise, but at the expense of ischemia-reperfusion injury after prolonged deployment, particularly in zone I aortic injuries7 (as defined in the Stannard classification of traumatic aortic injuries8), as well as limitations from uncontrolled retrograde hemorrhage.9 This scenario is mirrored in clinical REBOA outcomes, with the literature citing higher mortality and complications rates in patients undergoing REBOA,1 despite its relative efficacy in establishing hemostasis.6 Although commercial stent grafts (stents covered in polymer) would seem a natural solution to control of hemorrhage,10 these stents are permanent, requiring significant expertise, wire and catheter exchanges, stent graft inventory, and robust imaging to ensure the stent is not misplaced irreversibly. As a result, although useful electively and sometimes urgently in a controlled environment, the currently available stent grafts present significant logistical barriers for exsanguinating hemorrhage, especially in the austere environment.

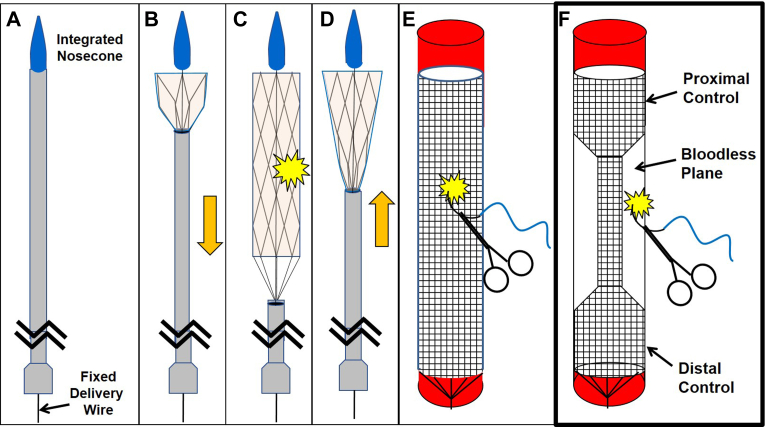

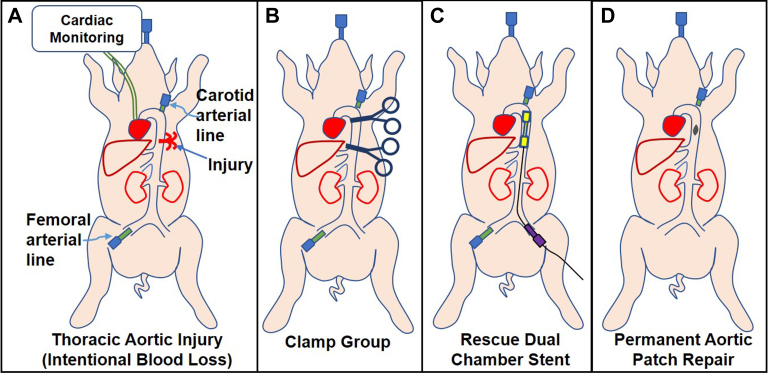

Our group has detailed previously the development of the rescue stent, a retrievable stent graft with a self-contained delivery system9,11, 12, 13 for use as a damage control approach for major torso hemorrhage, which is then removed before a permanent repair is made (Fig 1, A-D). More recently, we have detailed morphometric-based stent algorithms14 to provide triage for sizing of limited device inventory in a diverse human population, but also a novel nonfluoroscopic magnetic positioning approach for positioning stents in vivo when fluoroscopy is not available (Kenawy, February 1, 2023, manuscript in submission). In summary, retrievable stents could provide damage control that allows transfer to a higher level of care or from a trauma bay to an operating room, for instance.

Fig 1.

The retrievable stent provides deployment by sheath withdrawal for damage control of hemorrhage (A, B, and C) and retrieval by sheath advancement over a permanently attached delivery wire to collapse the stent (D). Nevertheless, the cylindrical design (E) is unfavorable for direct suture repair, because the suture might ensnare the stent. Alternately, a dumbbell-shaped stent (F) provides an essentially bloodless compartment for suture placement, all while preserving distal perfusion.

One notable limitation was that the cylindrical stent design prevented concurrent suture repair during stent deployment owing to concern for stent ensnarement (Fig 1, E). We have previously reported a modified dumbbell-shaped retrievable stent graft to divide the aorta hemostatically into two compartments, specifically for the enhancement of visceral perfusion in donor organ recovery.15 We reasoned that this same dumbbell design could provide a bloodless plane overlying the midsection of the stent to facilitate permanent aortic repair, while still providing critical distal perfusion (Fig 1, F). Moreover, the stent graft could be inserted remote from the actual injury from a more easily accessible vessel (infrarenal aorta or femoral) (Fig 2). Although the center lumen does narrow the flow lumen, the hemodynamic literature suggests that diameter reduction of less than 50% has a minimal impact on flow16,17 and is certainly better than no flow at all. In this study, we hypothesized that a dumbbell-shaped rescue stent (dRS) would provide superior hemodynamic and physiological outcomes compared with traditional aortic cross-clamping in the context of injuries to the descending thoracic aorta and allow direct aortic suture repair before removal of the retrievable stent graft. In contrast with previous studies in which stents were hand welded with an adhered polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sleeve, the current study uses more a durable and precise laser-cut nitinol scaffold and a more resilient PTFE encapsulation process.

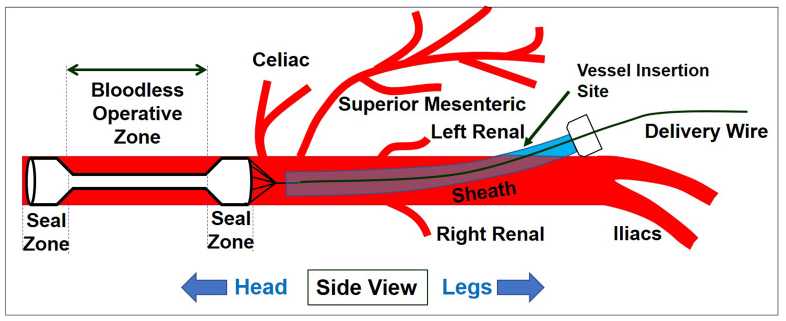

Fig 2.

Aortic control from a more anatomically favorable location. The dual chamber Rescue stent graft inserts from an infrarenal (or more favorable femoral) access remote from the actual operative site, which may be obscured by bleeding. The stent graft creates a bloodless operative zone, while at the same time ensuring distal perfusion.

Methods

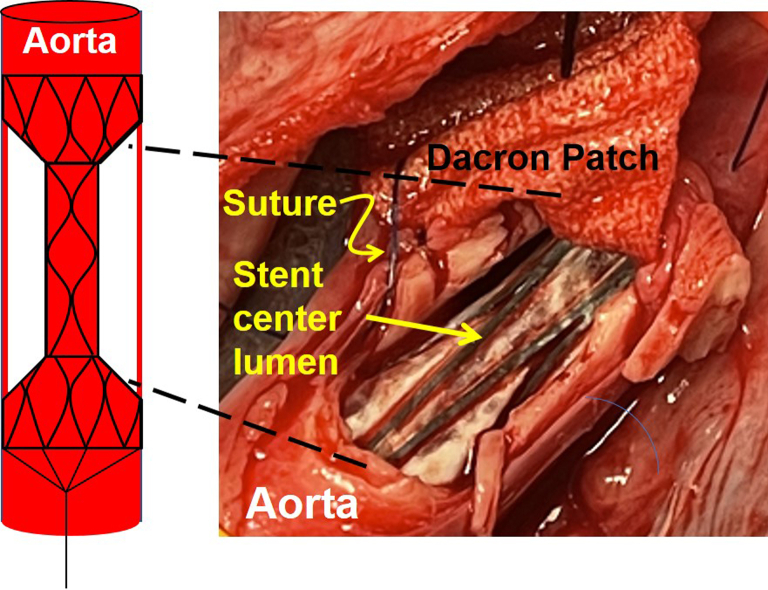

Stent graft design

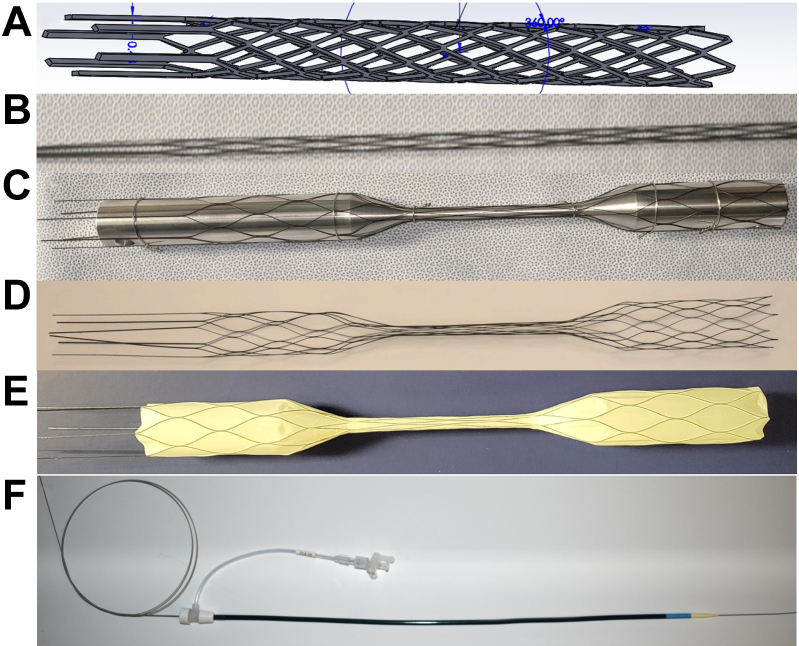

A custom scaffold was designed in Solidworks (Dassault Systèmes SolidWorks Corporation, Waltham, MA) and lasercut from nitinol tubing scaffold (Burpee Materials Technology, Eatontown, NJ) (Fig 3, A, B). After thermal shapesetting as previously described15 using a dumbbell-shaped mandrel, the scaffolds were encapsulated with electrospun PTFE (Bioweb, Zeus, Orangeburg, SC) (Fig 3, C-E). The larger proximal and distal seal zones of the dumbbell stent were 8 cm long and 27 mm in diameter, and the narrow center lumen was 10 cm long and 7 mm in diameter. Inclusive of the tapered transition zones, the entire stent graft length was 30 cm. The stent was affixed to a proximal nosecone and distally was permanently attached to a stiff delivery wire (Lunderquist, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) to allow deployment and retrieval. The self-expanding stent grafts were compressed into a 12F sheath (Cook Medical) for in vivo deployment (Fig 3, F).

Fig 3.

Retrievable rescue stent. A computer modeled stent (A) is laser cut from nitinol to create a scaffold (B), followed by shapesetting onto a dumbbell mandrel (C). The shapeset scaffold (D) is covered with encapsulated polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) (E). Later, a nosecone and a permanently attached delivery wire for the final stent graft before compression into a 12F sheath (F).

Baseline monitoring

This study received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Ohio State University. Yorkshire cross pigs (77.4 ± 10.1 kg) were divided into two groups: control/cross-clamp (n = 4 females, 2 males) and dRS (n = 3 females, 3 males). Animals were sedated and general endotracheal anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane. A dose of 10 mg/kg intravenous amiodarone was administered preoperatively to prevent arrhythmias that are common in porcine models during major surgery.18,19

Hemodynamic monitoring was maintained via electrocardiogram, carotid and femoral arterial lines, and a pulmonary artery catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA), as previously described.9 All animals had baseline hemodynamic parameters recorded, including heart rate, carotid, and femoral mean arterial pressure (MAP), cardiac output (CO), right ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV), and mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2). Heparin (100 units/kg) was administered to both simulate the coagulopathy of the trauma patient and to counteract the robust hypercoagulability inherent to the porcine model.9

Arterial blood gas (ABG) testing became available midway in the study and femoral ABGs were obtained during the injury phase and compared with baseline values to assess distal oxygenation in one-half of the animals. In all animals, bilateral renal artery ultrasonic flow measurements were obtained (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Renal artery flows were reported as a percentage of the CO to better reflect flow in the expectedly hypotensive animal.

Aortic injury phase

The injury model is illustrated in Fig 4. After creating a midline laparotomy, the diaphragm was circumferentially divided posteriorly, the descending thoracic aorta was exposed, and an elliptical 3 cm2 defect was made using a 1.5 cm × 2.0 cm template in the thoracic aorta. Intentional blood loss was set to 22% of total blood volume to simulate class II to III hemorrhagic shock. Shed blood was suctioned into a Cell Saver (Sorin Xtra, Livanova, Houston, TX) and autotransfused immediately. Animals were assigned to either aortic clamp vs dRS for hemorrhage control. In dRS animals, the stent graft was delivered through the infrarenal aorta owing to the small size of the porcine femoral vessels and deployed within the descending thoracic aorta, with the stent graft outer chamber bridging the area of injury. Angiography was performed after cross-clamping and stent deployment to assess for distal perfusion. A sutured Dacron patch repair of the thoracic aorta was performed in both groups. The duration of the clamping or stenting was consistent between groups at 1 hour, regardless of the time for Dacron patch repair completion, to account for expected transport within a hospital, between hospitals, resuscitation, or management of concomitant injuries. Phenylephrine was given in 1-mg boluses with a threshold MAP of less than 30 mm Hg. Finally, clamps were removed and the dRS was retrieved by sheath advancement to collapse the stent graft for removal, followed by primary suture repair of the infrarenal aortic access. Protamine was administered for reversal of heparin. Total blood loss and blood transfused during the injury phase were recorded, in addition to total volume of phenylephrine used. Recovery hemodynamics were averaged over the first 15 minutes after cross-clamp or stent removal. Distal flow and perfusion were assessed using several metrics.

Fig 4.

Study design consisting of (A) terminal porcine model of thoracic aortic injury with intentional blood loss, then use of either (B) aortic cross-clamp or (C) dumbbell rescue stent graft deployment, followed by (D) a permanent aortic repair with a sutured vascular patch while the clamp or stent is in place.

Statistical analyses

The Student t test was used to compare physiological and hemodynamic parameters between cross-clamped and rescue stent animals, unless otherwise specified. ABG data between the groups were compared using a linear mixed effects model with random intercepts to estimate and compare means by group and time while accounting for correlation between repeated measures on the study pigs.

Results

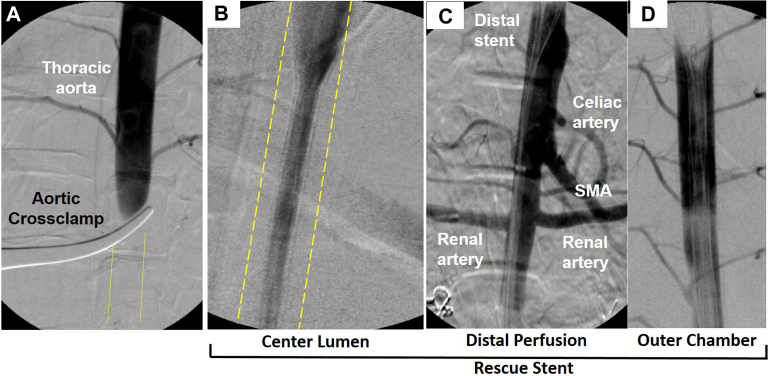

Improved angiographic distal perfusion

Angiography was performed to document both exclusion of the injury and preserved distal flow. Angiographically, no flow was seen distally in cross-clamped animals during the injury phase. Conversely, in addition to hemorrhage control by the dRS, distal perfusion was visualized through the center lumen of the stent graft, including the abdominal viscera (Fig 5). The images further depict the hemostatic outer chamber of the stent graft, defined as the space between the outer circumference of the center lumen and the aortic wall.

Fig 5.

Angiogram after cross-clamping (A) reveals absent distal perfusion. Conversely, a dumbbell rescue stent placed in the thoracic aorta preserves perfusion through the center lumen of the stent (B, aortic wall outlined) and distally to the viscera (C). Simultaneously, the stent graft created an isolated outer chamber (D), which forms a bloodless operative field, aside from small intercostal backbleeding. SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

Hemostasis of the outer dRS chamber

Among animals in the clamp group, traditional hemostasis was conferred by proximal and distal aortic clamp placement, with expected continued bleeding from the intercostal branches. In stent graft-treated animals, after dRS placement across the aortic injury, the outer chamber conferred a relatively bloodless space with both proximal and distal control of bleeding. The bleeding in this space was again a consequence of retrograde bleeding of intercostal vessels as seen with the clamped animals. The otherwise bloodless space in the outer chamber of the stent is depicted in Fig 6.

Fig 6.

Sutured patch repair of the thoracic aorta with dumbbell rescue stent in place and providing proximal and distal hemorrhage control. The stent center lumen is outlined by the thin dashed yellow line.

Improved physiological distal perfusion

Distal perfusion was assayed physiologically by several assays (Table I). First, among clamped animals there was a large decrease from the carotid pressure to the nearly absent femoral pressure, with a difference averaging 86.5 mm Hg and confirming absent distal aortic flow. The findings were strikingly different in dRS-treated animals. Although there was a small carotid to femoral gradient, averaging 12.6 mm Hg, this difference between the carotid and femoral were not significantly different from each other (P = .50); furthermore, this value was significantly different than the decrease noted among the clamped animals (P = .0002). Overall, these findings suggested that the dRS-preserved distal arterial pressure contrasts with the absent distal pressure among clamped animals.

Table I.

Hemodynamic parameters during baseline, injury, and recovery phases in cross-clamp and dumbbell-shaped rescue stent (dRS) animals

| Hemodynamic parameter | Cross-clamp (n = 6) | dRS (n = 6) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, bpm | |||

| Baseline | 79.0 ± 9.5 | 82.6 ± 8.2 | .51 |

| Injury | 147 ± 28 | 119 ± 21 | .082 |

| Recovery | 136 ± 25 | 150 ± 28 | .40 |

| Carotid MAP, mm Hg | |||

| Baseline | 62.7 ± 9.8 | 63.5 ± 6.9 | .87 |

| Injury | 87 ± 26 | 86 ± 29 | .97 |

| Recovery | 33 ± 12 | 53 ± 15 | .033 |

| Femoral MAP, mm Hg | |||

| Injury | 0 ± 0 | 73 ± 34 | .0004 |

| CO, mL/min | |||

| Baseline | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | .36 |

| Injury | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | .18 |

| Recovery | 2.2 ± 1.3 (n = 5) | 5.0 ± 1.7 | .015 |

| RVEDV, mL | |||

| Baseline | 249 ± 67 | 246 ± 63 | .94 |

| Injury | 176 ± 83 | 210 ± 32 | .37 |

| Recovery | 111 ± 34 (n = 5) | 162 ± 19 | .012 |

| SvO2, % | |||

| Baseline | 75.0 ± 6.6 | 77.6 ± 5.5 | .48 |

| Injury | 76 ± 13 | 82.0 ± 6.4 | .34 |

| Recovery | 54 ± 18 (n = 5) | 67.3 ± 8.1 | 0.12 |

CO, Cardiac output; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RVEDV, right ventricular end-diastolic volume; SvO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation;

Values are mean ± standard deviation. P values represent differences between both study groups at each operative phase. Boldface entries indicate statistical significance.

As yet another measure of oxygen delivery and ischemic metabolism after stenting, ABGs were assessed in the selected animals (n = 3 per group) at the baseline, injury, and recovery phases. There was no significant difference between baseline pH of the two study groups, and yet the recovery pH was significantly more acidotic clamp animals as compared with dRS animals (P = .044) (Table II). This finding was mirrored by recovery phase bicarbonate values, which were noted to be significantly higher in dRS animals (P = .006). This latter finding suggested a more significant depletion of bicarbonate, presumably owing to buffering excess acidity.

Table II.

Baseline and recovery arterial blood gas (ABG) values in cross-clamp and dumbbell-shaped rescue stent (dRS) animals

| Cross-clamp | dRS mean | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | n = 3 | n = 6 | -- |

| Baseline | 7.46 ± 0.046 | 7.48 ± 0.035 | .50 |

| Recovery | 7.17 ± 0.070 | 7.24 ± 0.026 | .044 |

| HCO3 | n = 3 | n = 6 | -- |

| Baseline | 32.2 ± 3.9 | 33.7 ± 1.1 | .43 |

| Recovery | 16.2 ± 2.1 | 22.4 ± 3.3 | .0055 |

| pO2 | n = 3 | n = 6 | -- |

| Baseline | 471 ± 118 | 464 ± 75 | .93 |

| Recovery | 175 ± 108 | 311 ± 151 | .12 |

| pO2 | n = 3 | n = 3 | -- |

| Injury, carotid | 364 ± 46 | 400 ± 49 | .48 |

| Injury, femoral | 176 ± 94 | 370 ± 29 | .0060 |

pO2, Partial pressure of oxygen.

Values are mean ± standard deviation. Boldface entries indicate statistical significance.

The partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) also did not demonstrate a significant difference between the groups at either baseline or after recovery; however, the femoral pO2 was significantly higher during the injury phase among dRS animals as compared with the clamp group (P = .00,060). More specifically, there was no difference in carotid vs femoral pO2 during the injury phase in dRS animals (P = .44), whereas a significant difference was observed between the carotid and femoral among the clamped animals (P = .006). Together, these findings suggested improved oxygen delivery at the femoral level in stent-treated animals as compared with those with a clamp for aortic control.

Finally, as an objective measure of visceral perfusion, renal blood flow was quantitated with ultrasonic flow measurements. To account for lower CO expected amidst hemodynamic shock after hemorrhage in the injury phase, renal blood flow measurements were normalized as a percentage of CO (Table III). Although the average renal blood flow was consistently absent after aortic clamping, renal perfusion was decreased but preserved among dRS animals (P < .0001; dRS vs clamp).

Table III.

Injury phase renal flow as a percentage of cardiac output (CO) at baseline and during cross-clamp vs dumbbell-shaped rescue stent (dRS) deployment

| Renal flow as a percentage of CO (n = 12) | Cross-clamp | dRS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (%) | 5.6 ± 2.5 | 4.3 ± 2.6 | .23 |

| Injury (%) | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 1.4 ± 0.76 | <.0001 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation. Boldface entries indicate statistical significance.

Blood loss

It was hypothesized that a dRS would convey similar hemostasis to traditional aortic clamping. This study revealed that blood loss above the intentional blood loss among clamp (1730 ± 625 mL) and stent (1297 ± 991 mL) groups was not significantly different (P = .39), illustrating comparable hemostasis.

Recovery phase physiology

It was anticipated that physiology would be improved in the dRS group as a result of preserved distal perfusion and decreased ischemia-reperfusion injury. Heart rates were not significantly different between the groups at the baseline (P = .51), injury (P = .082), or recovery (P = .40) phases (Table I).

Immediately after either clamp release or stent removal, however, the carotid MAP and CO were significantly higher in the dRS group (P = .033 and P = .015, respectively). The RVEDV, representing preload, was also significantly higher in the dRS group during recovery (P = .012). Although the minimum SvO2 (a measure of oxygen extraction) during recovery was higher in the dRS group, it failed to reach statistical significance (P = .12). Notably, pulmonary artery catheter readings were lost in one of the clamp animals after clamp release owing to measurements falling below the monitor's threshold.

To prevent the cardiac arrest that is known to occur in the porcine model below a MAP of 30 mm Hg,20 animals were administered pressor support in the form of 1-mg phenylephrine boluses at this threshold. The clamp group received significantly more mean phenylephrine as compared with dRS animals (0.90 ± 0.87 mg vs 0.033 ± 0.082 mg; P = .035).

Discussion

NCTH is a tremendously high-mortality injury, with every moment being critical before rapid exsanguination.3 Resuscitative thoracotomy with aortic cross-clamping can provide rapid hemorrhage control and preservation of critical blood flow to the brain and myocardium for patients in extremis,21 albeit at the expense of increased aortic afterload and cardiac ischemia.22 In fact, in patients with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, the aortic cross-clamp time was found to be an independent predictor of mortality.23 Postclamp physiology can be similarly detrimental, with central hypovolemia resulting from increased vascular capacitance of and blood flow to previously ischemic vascular beds.22 This phenomenon is often exacerbated by the use of vasopressors, which preferentially benefit nonischemic tissue, yet worsen the ischemic picture distally.22

Although REBOA is a minimally invasive option that provides comparable hemorrhage control as clamping, several significant drawbacks have been identified for this approach, including retrograde hemorrhage distal to the area of balloon occlusion, distal ischemia, or further mechanical injury to the vessel.6,9 Traumatic zone I aortic placement is most common, particularly with less defined injuries,4 and occlusion times of more than 30 minutes risk significant ischemia-reperfusion injury.7 Although alternatives such as partial and intermittent REBOA have been proposed to combat these adverse effects,5 the impact of these refinements on ischemic complications remains to be determined. Whereas the open surgical clamp often triggers a surgeon's internal clock of ischemic time, the minimally invasive nature of REBOA may offer false reassurance, when in fact the ischemia is probably equally as profound as with the clamp method.

We have previously demonstrated the use of a three-tier rescue stent graft to obtain rapid hemorrhage control of zones I and III aortic injuries while maintaining perfusion of zone II visceral branches as well as the lower extremities.9 Although the use of this stent graft demonstrated superior hemorrhage control, as well as hemodynamic and physiological outcomes compared with REBOA, a major limitation was the inability to perform permanent suture repair of the aorta during deployment, owing to the likelihood for suture ensnarement on the cylindrical design. To address this limitation, a modified dumbbell-shaped design with a 50% diameter decrease in the midsection of the stent was designed to provide a bloodless plane and enable aortic suture repair during stent deployment without sacrificing distal perfusion or hemorrhage control. In practice, the bloodless plane applies only to proximal and distal aortic control; our data clearly reveal ongoing blood loss from intercostal bleeding. Nevertheless, the stent provided an adequately decreased blood loss to allow visualization for repair. For certain, intraluminal suture ligation or posterior clipping of the intercostals may have decreased these losses further.

As expected, distal perfusion was essentially absent in the cross-clamp group. Conversely, distal perfusion with the dRS was validated using multiple metrics, including angiography, hemodynamics, renal blood flow, and distal oxygenation. Although previous cylindrical rescue stent graft designs have also maintained distal perfusion while achieving hemorrhage control,9,11 the ability to perform simultaneous suture repair with the dumbbell shape of the dRS without suture ensnarement represents a clear advantage of this design.

More specifically, with regard to renal blood flow, animals in the cross-clamp group were observed to have less than 5% of baseline renal flow during the injury phase, whereas dRS animals preserved approximately one-third of their baseline renal flow during stent graft deployment. Although the dRS animals still had a notable decrease in their renal flow during the injury phase, this finding in part is related to the hemorrhagic shock during the second measurement. Furthermore, a study by Best et al24 noted that as little as 25% of baseline renal flow conferred renal protection in a porcine partial nephrectomy model. Given that the kidneys have been shown to be one of the most sensitive viscera to ischemia after aortic occlusion,25 this finding suggests the dRS may prevent the renal ischemic injury and failure that so profoundly impacts non-compressible hemorrhage survivors.

From a cardiac physiological standpoint, animals in the dRS group had multiple measures suggesting improved hemodynamics, such as a higher CO, RVEDV, and MAP during the recovery phase, likely secondary to decreased reperfusion syndrome as compared with the cross-clamp group. Although we were unable to demonstrate evidence of a statistically significant difference in recovery phase SvO2 values between the two groups, it is possible that this was due to our small sample size. Notably, data were unable to be obtained for one of the cross-clamp animals owing to readings below the threshold of our pulmonary artery catheter, indicating that this cross-clamped animal had significantly decreased hemodynamic parameters during the recovery phase of the procedure.

Although ischemic injury is, for certain, a major drawback of cross-clamp-based aortic repair, the effects of reperfusion including acidosis and hypotension further the physiological insult. Our findings revealed increased hypotension and pressor requirements after clamp release as compared with the stent animals, suggested that, by preventing ischemia at the outset, reperfusion hypotension may be avoided. With respect to acid-base status, animals treated with the dRS were notably less acidotic, as indicated by significantly higher pH and bicarbonate levels than in the cross-clamp animals.

A potential limitation of our study was the use of a vascular clamp as a comparison to the dRS because, in an austere environment, a less invasive REBOA would be a more likely damage control approach. This choice of a clamp was made because we have reported previously the outcomes of REBOA in this model,5 and furthermore felt the true asset of the dRS for this study was replacement of the vascular clamp for the definitive open repair. Although the integrated nosecone and simple pin-and-pull deployment facilitate ease of use, competence in vascular access remains critical and we anticipate that, as with the REBOA, there will be a learning curve for use in an emergency. The current laboratory grade sheath size of 12F would benefit from further refinement of the design to decrease access site complications.

Another notable limitation of our stent graft was the need to deliver it through the infrarenal aorta owing to initial theoretical concern of the small diameter of porcine femoral arteries relative to humans Nevertheless, we now routinely deliver this same 12F device percutaneously from the femoral vessels without issue, and the human age demographic subject to penetrating traumatic injury have femoral arteries at least twice the size of the porcine model. Although this terminal study focused on the physiological advantages of dRS, future studies need to fully examine more fully postoperative evidence of organ ischemia, organ failure, and survival.

The logistical complexities of traumatic aortic injuries cannot be overstated. The stark reality is that many patients with these injuries may not even survive to a medical facility. In other cases, a patient may present directly to an environment where immediate permanent open or endovascular repair is appropriate. In addition, injuries of abdominal aorta may be amenable to other, more conventional strategies with balloon occlusion or vascular clamp. This damage control approach may offer particular advantages for the following scenarios: (1) transition of battlefield injuries from a front line to a higher echelon of care, (2) management of mass shootings when the volume of injured patients may outstrip hospital resources, (3) transfer of patients from qualified regional hospitals to a tertiary hospital for definitive repair, (4) injuries near critical visceral branches or with accompanying soilage where a permanent endograft repair may be inappropriate, or (5) care of polytrauma patients when initial resuscitation or management of other injuries (eg craniotomy) may deter an immediate permanent repair. (6) In injuries near visceral branches in particular, the temporary stent graft may cause a temporary loss of flow to that branch until open repair is complete, but certainly it is more favorable than permanent endograft coverage.

Importantly, this was a laboratory-based porcine study; as such, proper regulatory approvals and investigation of this device as part of a human clinical trial will be needed before a dRS can be considered as a viable clinical tool.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the use of a dRS for simultaneous hemorrhage control and aortic repair, with superior hemodynamic and physiological outcomes compared with aortic cross-clamping in a porcine, large animal model. The advantages observed in this study have far-reaching implications beyond traumatic injury, and future studies will compare this approach with aortic clamping in elective open aortic repair.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: DK, YC, BWT

Analysis and interpretation: DK, MAR, BWT

Data collection: DK, ME, TK, MGN, BWT

Writing the article: DK, ME, MAR, TK, MGN, YC, BWT

Critical revision of the article: DK, BWT

Final approval of the article: DK, ME, MAR, TK, MGN, YC, BWT

Statistical analysis: MAR

Obtained funding: YC, BWT

Overall responsibility: BWT

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Defense Medical Research and Development Program under Award No. W81XWH-16-2-0062. Content is solely from the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. † This research was supported by National Institutes of Health under the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award, from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number NIH T32AI106704. Content does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This project was also supported by the UL1TR002733 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Author conflict of interest: B.W.T. and Y.C. have filed intellectual property on the dumbbell stent design.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS-Vascular Science policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Joseph B., Zeeshan M., Sakran J.V., Hamidi M., Kulvatunyou N., Khan M., et al. Nationwide analysis of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in civilian trauma. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:500–508. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison J.J., Rasmussen T.E. Noncompressible torso hemorrhage: a review with contemporary definitions and management strategies. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92:843–858. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.05.002. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alarhayem A.Q., Myers J.G., Dent D., Liao L., Muir M., Mueller D., et al. Time is the enemy: mortality in trauma patients with hemorrhage from torso injury occurs long before the "golden hour". Am J Surg. 2016;212:1101–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo R.M., Neff L.P., Johnson M.A., Williams T.K. Emerging endovascular Therapies for non-compressible torso hemorrhage. Shock. 2016;46(3 Suppl 1):12–19. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner M., Moore L., Dubose J., Scalea T. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) for Use in temporizing Intra-abdominal and Pelvic hemorrhage: physiologic Sequelae and Considerations. Shock. 2020;54:615–622. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner M.L., Moore L.J., DuBose J.J., Tyson G.H., McNutt M.K., Albarado R.P., et al. A clinical series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control and resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:506–511. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31829e5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauvar D.S., Dubick M.A., Martin M.J. Large animal models of proximal aortic balloon occlusion in traumatic hemorrhage: review and identification of knowledge gaps relevant to expanded use. J Surg Res. 2019;236:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stannard A., Eliason J.L., Rasmussen T.E. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) as an adjunct for hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2011;71:1869–1872. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823fe90c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go C., Elsisy M., Chun Y., Thirumala P.D., Clark W.W., Cho S.K., et al. A three-tier Rescue stent improves outcomes over balloon occlusion in a porcine model of noncompressible hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89:320–328. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouawad N.J., Paulisin J., Hofmeister S., Thomas M.B. Blunt thoracic aortic injury - concepts and management. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15:62. doi: 10.1186/s13019-020-01101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Go C., Chun Y.J., Kuhn J., Chen Y., Cho S.K., Clark W.C., et al. Damage control of caval injuries in a porcine model using a retrievable rescue stent. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6:646–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun Y., Cho S.K., Clark W.C., Wagner W.R., Gu X., Tevar A.D., et al. A retrievable rescue stent graft and radiofrequency positioning for rapid control of noncompressible hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:249–255. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsisy M., Tillman B.W., Go C., Kuhn J., Cho S.K., Clark W.W., et al. Comprehensive assessment of mechanical behavior of an extremely long stent graft to control hemorrhage in torso. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2020;108:2192–2203. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Go C., Fish L., Chun Y., Alarcon L., Tillman B.W. The anchor point algorithm: a morphometric analysis of anatomic landmarks to guide placement of temporary aortic Rescue stent grafts for noncompressible torso hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93:488–495. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go C., Elsisy M., Frenz B., Moses J.B., Tevar A.D., Demetris A.J., et al. A retrievable, dual-chamber stent protects against warm ischemia of donor organs in a model of donation after circulatory death. Surgery. 2022;171:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moawad J., Brown S., Schwartz L.B. The effect of 'non-critical' (<50%) stenosis on vein graft longitudinal resistance and impedance. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:517–520. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berguer R., Hwang N.H. Critical arterial stenosis: a theoretical and experimental solution. Ann Surg. 1974;180:39–50. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197407000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bharati S., Levine M., Huang S.K., Handler B., Parr G.V., Bauernfeind R., et al. The conduction system of the swine heart. Chest. 1991;100:207–212. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith A.C.S.M. Anesthesia and Analgesia in laboratory animals. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2008. Anesthesia and Analgesia in swine. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eschbach D., Steinfeldt T., Hildebrand F., Frink M., Scholler K., Sassen M., et al. A porcine polytrauma model with two different degrees of hemorrhagic shock: outcome related to trauma within the first 48 h. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:73. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0162-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biffl W.L., Fox C.J., Moore E.E. The role of REBOA in the control of exsanguinating torso hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:1054–1058. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zammert M., Gelman S. The pathophysiology of aortic cross-clamping. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2016;30:257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doenst T., Borger M.A., Weisel R.D., Yau T.M., Maganti M., Rao V. Relation between aortic cross-clamp time and mortality--not as straightforward as expected. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Best S.L., Thapa A., Holzer M.J., Jackson N., Mir S.A., Cadeddu J.A., et al. Minimal arterial in-flow protects renal oxygenation and function during porcine partial nephrectomy: confirmation by hyperspectral imaging. Urology. 2011;78:961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoehn M.R., Teeter W.A., Morrison J.J., Gamble W.B., Hu P., Stein D.M., et al. Aortic branch vessel flow during resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86:79–85. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]