Abstract

Purpose:

Current glioma diagnostic guidelines call for molecular profiling to stratify patients into prognostic and treatment subgroups. In case the tumor tissue is inaccessible, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been proposed as a reliable tumor DNA source for liquid biopsy. We prospectively investigated the use of CSF for molecular characterization of newly diagnosed gliomas.

Experimental Design:

We recruited two cohorts of newly diagnosed patients with glioma, one (n = 45) providing CSF collected in proximity of the tumor, the other (n = 39) CSF collected by lumbar puncture (LP). Both cohorts provided tumor tissues by surgery concomitant with CSF sampling. DNA samples retrieved from CSF and matched tumors were systematically characterized and compared by comprehensive (NGS, next-generation sequencing) or targeted (ddPCR, droplet digital PCR) methodologies. Conventional and molecular diagnosis outcomes were compared.

Results:

We report that tumor DNA is abundant in CSF close to the tumor, but scanty and mostly below NGS sensitivity threshold in CSF from LP. Indeed, tumor DNA is mostly released by cells invading liquoral spaces, generating a gradient that attenuates by departing from the tumor. Nevertheless, in >60% of LP CSF samples, tumor DNA is sufficient to assess a selected panel of genetic alterations (IDH and TERT promoter mutations, EGFR amplification, CDKN2A/B deletion: ITEC protocol) and MGMT methylation that, combined with imaging, enable tissue-agnostic identification of main glioma molecular subtypes.

Conclusions:

This study shows potentialities and limitations of CSF liquid biopsy in achieving molecular characterization of gliomas at first clinical presentation and proposes a protocol to maximize diagnostic information retrievable from CSF DNA.

Translational Relevance.

In primary brain tumors, the presence of the blood–brain barrier hampers the release of significant tumor DNA into the circulation, limiting the feasibility of blood-based liquid biopsy strategies. The possibility to exploit cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as an alternative source of circulating tumor DNA for broad genetic profiling of gliomas is currently under investigation. This is the first study that prospectively explores the use of CSF-based liquid biopsy for molecular characterization of newly diagnosed malignant gliomas. Here, we show that the yield of tumor DNA in CSF from lumbar puncture is very poor, preventing the application of a comprehensive next-generation sequencing analysis in most cases. Nevertheless, we demonstrate the systematic feasibility of a high-sensitivity droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)-based protocol (ITEC) covering a set of glioma-specific genetic alterations with diagnostic and predictive significance. This tool may be applied when the tumor is not surgically approachable, allowing a presumptive molecular diagnosis according to WHO 2021 criteria and a tailored treatment.

Introduction

The 2021 WHO classification of brain tumors emphasizes the primacy of molecular characterization for glioma subtyping (1, 2). Accordingly, on the one hand, detection of an IDH wild-type (WT) gene is required to classify a glioma as a glioblastoma (GBM); on the other hand, the presence of a limited set of genetic features, such as IDH WT gene together with either telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter (pTERT) mutation, or EGFR gene amplification, or gain of entire chromosome 7 combined with loss of chromosome 10, is sufficient to classify a glioma as a GBM even in the absence of distinctive GBM histopathological features (1–3). Among IDH-mutant gliomas, grading takes into account the presence of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/B (CDKN2A/B) homozygous deletion, which defines grade 4 and results in worse prognosis regardless of histopathology. Characterization of such genetic biomarkers has, therefore, diagnostic and prognostic implications and requires to be implemented in the routine clinical setting. Besides, although the number of recognized biomarkers is currently limited, the increased cost-effectiveness of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies offers the opportunity to replace targeted with comprehensive sequential analyses (4).

In gliomas, standard molecular characterization based on tumor tissue samples can occasionally be unfeasible, due to inaccessible tumor location, or it can suffer from several limitations, including failure to recapitulate the well-known intratumor glioma genetic heterogeneity (5) and to detect genetic alterations (in particular gene copy-number loss) for excessive contamination by non-tumor tissue. Moreover, if longitudinal patient monitoring is needed, repeated biopsies can be hard to obtain, precluding a new molecular characterization of recurrent tumors.

In recent years, liquid biopsy of cell-free circulating tumor DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as an intriguing alternative to tissue biopsy. Beside portability, liquid biopsy offers better chances to capture tumor genetic heterogeneity and to assist in longitudinal monitoring of the patient, being in principle able to provide information on tumor genetic evolution over time, and on the ensuing emergence of predictive or response biomarkers (6–8). This is critical to select patients for targeted therapies that recently yielded encouraging results (9–12). Moreover, liquid biopsy could help to measure tumor burden in response to treatments, as MRI-based neuroimaging can fail to identify pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse (13).

Unlike in other tumors, blood was shown to be a poor source of brain tumor cfDNA (14–16). Conversely, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) seems to offer the opportunity to retrieve tumor DNA and to analyze genetic alterations either by targeted or more comprehensive NGS methodologies in both adult and pediatric gliomas and medulloblastomas (15–23). However, substantial questions await to be solved for translating CSF liquid biopsy into clinical practice and to align liquid biopsy purposes with our current understanding of glioma genetics and its impact on clinical management.

In particular, we still need prospective studies that systematically address: (i) the possibility of finding tumor DNA in CSF collected by lumbar puncture (LP-CSF) in patients with glioma at first diagnosis, before surgery and radiotherapy; (ii) the qualitative and quantitative features of CSF tumor DNA, which depend on the still unclear sources of the DNA and its circulation dynamics in CSF, and strongly influence the possibility of detection by current techniques; (iii) whether performing an extensive NGS analysis of CSF tumor DNA is feasible in newly diagnosed, presurgical patients; (iv) how closely the genetic alterations found in LP-CSF recapitulate those found in matched tumor tissues.

To answer these questions, in this work we analyzed two cohorts of gliomas at first diagnosis, one providing peritumoral CSF, the other LP-CSF, and both giving tumor tissues by surgery concomitant with CSF sampling.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

Cohort 1 patients with a diagnosis of primary brain tumor according to WHO guidelines were enrolled and treated at the “Città della Salute e della Scienza” (University of Torino, Italy) in a prospective observational trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03347318) approved by the Ethical Committee of Città della Salute e della Scienza (Torino, Italy). In Cohort 2, patients with a diagnosis of primary brain tumor according to WHO guidelines were enrolled and treated at “IRCCS, Humanitas Research Hospital” (Humanitas University, Italy) in a prospective observational trial (ONC/OSS-06/2017) approved by the Ethical Committee of IRCCS, Humanitas Research Hospital (Rozzano, Milan, Italy). For both cohorts, informed written consent stating that the samples collected could be used for research was obtained from all patients and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient data and samples were de-identified before processing.

Analysis of imaging data

Pre-operative brain MRI scans performed just before CSF sampling, and including at least T1 pre- and post-contrast enhancement, T2, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion weighted sequences, were collected and analyzed to describe tumor characteristics in a blinded manner to information about DNA concentration. The area of tumor was measured using the maximal diameter (D) and a second perpendicular measurement (d) on the axial slides of T1 post-contrast enhancement or FLAIR sequences, according to the presence or absence of contrast-enhancement, respectively. The lesion was defined as abutting the CSF space if in contact with at least one of the primary liquor reservoirs such as ventricles or basal and other cisterns. Tumor disease progression was established according to Radiological Assessment in Neuro-oncology (RANO) criteria or after a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion.

Sample collection and preprocessing

In Cohort 1 patients, peritumoral CSF samples were collected at the opening of the surgical field, in proximity of the tumor and before tumor removal, by leakage from the subarachnoid space (n = 43) or by aspiration from the ventricle (n = 2). In all Cohort 2 patients, CSF was collected by LP, in 38/39 patients before surgery and, in one patient (MG2046), 2 months after the primary diagnosis to relieve obstructive hydrocephalus. In one patient (MG2049), CSF was collected twice, before first and second surgery for tumor recurrence, so that Cohort 2 provided a total of 40 LP-CSF samples. In both cohorts, after collection, CSFs were immediately centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10′ at room temperature (RT) according to previous protocols (16, 17, 23) and the presence of blood traces was annotated. Supernatants were carefully recovered for cfDNA isolation, further centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 minutes and immediately stored at −80°C. In Cohort 2, after the first centrifugation, pellets were recovered for cellular DNA isolation, and stored at −80°C. From each patient, at least 5 mL of whole blood was collected in Na2EDTA-coated tubes and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10′ RT. Then, plasma was recovered, centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10′ RT and stored at −80°C. The remaining cellular fraction underwent erythrocyte lysis using 10 vol/vol ACK lysis solution (0.15 mol/L NH4Cl, 1 mmol/L KHCO3, 0.1 mmol/L Na2EDTA, pH 7.4) and centrifugation at 1,200 rpm for 5′. The pellet (containing leukocytes) was resuspended in PBS and stored at −80°C. Fresh tumor tissues were collected during surgery and stored −80°C, or formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE).

DNA extraction, quantitative, and qualitative analyses

DNA extraction was centralized for all samples. DNA from CSF supernatant was extracted using a QIAamp MinElute ccfDNA Mini Kit (Qiagen); DNA from fresh tumor tissues, blood leukocytes, and CSF pellet was extracted using ReliaPrep gDNA Tissue Miniprep System (Promega); DNA from FFPE tumor tissue samples was extracted using Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE Kit (Promega). DNA from CSF supernatant and pellet was quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and qualitative fragmentation analysis was performed using Agilent High-Sensitivity DNA Kit and 2100 Bioanalyzer Instrument (Agilent). DNA from tumor tissues and blood leukocytes were analyzed with DS-11 FX Series Spectrophotometer/Fluorometer (DeNovix) and quantified using Qubit dsDNA HS/BR Assay Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All procedures related to DNA extraction and analysis were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sanger sequencing (Cohort 1 and 2 tumors)

In tumor gDNA samples (Cohort 1), IDH1/2 and pTERT hotspot mutations, and TP53 and PTEN full-length sequences were analyzed by Sanger Sequencing as detailed in Supplementary Information. In Cohort 2, pTERT hotspot mutations were analyzed by Sanger Sequencing as well. Data were processed by Chromas Lite 2.01 software (http://www.technelysium.com.au/chromas_lite.html) and compared with reference sequences from the Homo sapiens assembly GRCh37. All identified variants were analyzed for possible pathogenicity using MutationTaster2021 (24) and compared with those in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC, https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) and in IARC TP53 DATABASE (https://tp53.isb-cgc.org/; ref. 25).

Evaluation of IDH1 and 2 mutations (Cohort 2 tumors)

IDH1 and 2 mutations targeted to specific codons (R132 in IDH1 and R172 in IDH2) were tested by pyrosequencing using an IDH1/2 status kit (Diatech Pharmacogenetics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. IDH1 R132H mutation was revealed also by IHC using anti-IDH1 R132H mouse mAb (Clone H09; Dianova GmbH) on Benchmark Instrument (Ventana).

Gene copy-number variation analysis by qPCR (Cohort 1 tumors)

Gene copy-number variation (CNV) analysis was performed by real-time PCR, using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and the ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). TaqMan copy-number assays are listed in Supplementary Information (Key Resource Table) and Supplementary Data S1. Relative gene CNVs were calculated by normalizing versus multiple endogenous controls (GREB1, TERT, APOA1, RNAseP; results are reported vs. RNAseP). For CDKN2A/B locus, a CDKN2A-specific probe was used. A normal diploid human gDNA was used as calibrator to obtain the ΔΔCt. The copy number of each gene was calculated with the formula 2×2−ΔΔCt. Aberrant CNVs have been defined as follows: amplifications, CN > 5; deletions, CN < 1.5; gains, 3 > CN > 5.

EGFR CNV by FISH analysis (Cohort 2 tumors)

FISH was performed on 4 μm paraffin sections using the Tissue Digestion Kit (Kreatech Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The analyses were performed using EGFR/CEN7 dual-color probes (ZytoVision GmbH). Labeled SPEC EGFR probe is specific for the EGFR gene at 7p11.2. One hundred tumor cell nuclei were scored in 3 different fields. EGFR is considered amplified if EGFR/CEN7 ratio is > 2 or if EGFR green signal clusters are observed.

ddPCR (Cohort 1 and 2, tumors and CSF)

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) was performed using probe-based assays with ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP; Bio-Rad) following the manufacturers’ instructions. Droplets were generated using AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad) and analyzed on a QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System using QX Manager Software Standard Edition, Version 1.2 (Bio-Rad). CDKN2A, CDK4, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) CNV were normalized versus EIF2C1, RPP30, and AP3B1. EGFR CNV was normalized versus EIF2C1, RPP30, and AP3B1 or versus VOPP1 and ASL (mapping near chr 7 centromere), as to distinguish real CNV from chr 7 polysomy. IDH1, TP53, and PTEN mutations were analyzed following the manufacturer's instructions. pTERT analysis was performed according to ref. 26. For all assays, the minimum number of PCR-positive droplets (n = 30) was calculated according to ref. 27. The presence of mutations was confirmed when 3/30 droplets amplified the mutation. Specific ddPCR assays are reported in Supplementary Information (Key Resource Table). The following are the aberrant CNVs defined: amplifications, CN > 5; deletions, CN < 1.5; gains, 3 > CN > 5.

NGS analysis by a targeted panel (Cohort 1 and 2, tumors and CSF)

We designed a 388,773 kb capture-based custom panel, including all coding regions of 54 glioma-associated genes (see Supplementary Data S2). Libraries were constructed starting from >10 ng DNA using the “SureSelectXT HS Target Enrichment System for Illumina Paired-End Multiplexed Sequencing Library” kit (Agilent Technologies), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Libraries were sequenced on MiSeq sequencer (Illumina) with 150 bps paired-end reads. NGS data were processed both using a custom analysis pipeline developed in collaboration with OncoDNA (www.oncodna.com; ref. 28) using SureCall software as caller (version 4.1.1.5, Agilent Technologies) and the bioinformatic pipeline previously described in refs. 29 and 30. A metanormal was built from fastq files obtained by 10 PBMC samples sequenced as previously described (31). To delete NGS artifacts, mutations were further filtered as previously described (30, 31). Indels were called using Pindel tool in both alignments and only somatic indels with fractional abundance >10% were reported. Gene CNVs analysis was performed in the matched samples (tumor/liquor/pellet vs. metanormal) for each patient. Gene CN was calculated as the ratio of median gene depth and the median depth of all genomic regions covered in the panel. For each gene, the CNV was calculated as the ratio between CN of metanormal sample and CN of the same gene in the tumor/liquor/pellet one as previously reported (29–31). Sample authentication was performed using the list of “panel-covered” single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) listed in dbSNP version 147. An allele was considered only if the fractional abundance was higher than 30% with a minimum depth of 20X (31). All SNP_ID were compared to establish the correct sample matching. All identified variants were analyzed for possible pathogenicity as above. Amplifications and deletions were considered significant in oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes, respectively, based on annotation in OncoKB (https://www.oncokb.org/; ref. 32).

Analysis of MGMT promoter methylation (Cohort 1 and 2, tumors and CSF)

Bisulfite conversion of DNA extracted from tumors or CSF was performed by the EZ DNA methylation Gold kit (Zymo Research). In Cohort 1 tumors and CSF, and in Cohort 2 CSF, MGMT (O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase) promoter methylation was assessed by methyl-BEAMing multistep digital PCR according to ref. 33. In Cohort 2 tumors, it was assessed by pyrosequencing. For details see Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

When appropriate, descriptive statistical data were reported (median, confidence interval). Statistical comparisons were performed using the non-parametric Spearman's rank correlation. Where indicated, Fisher exact test with Bonferroni correction or χ2 test were applied. Data were summarized as frequencies and proportions or as medians and range, as appropriate. For continuous data, the Wilcoxon (Mann–Whitney) t test was used to compare differences between groups and the Pearson correlation coefficient to evaluate linear correlation. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated using Kaplan–Meier curves. All the reported P values were two-sided. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 or Prism v8.0 software (GraphPad).

Data availability

Complete datasets related to NGS analysis (referring to Figs. 2I and 3G; Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Tables S5 and S10) are available as Supplementary Data S2 (sheets 1–3). Raw NGS data are available at the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession number PRJEB55332, study ERP140225 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/search). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, Supplementary Information, and Supplementary Data S1 and S3. Other related data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Figure 2.

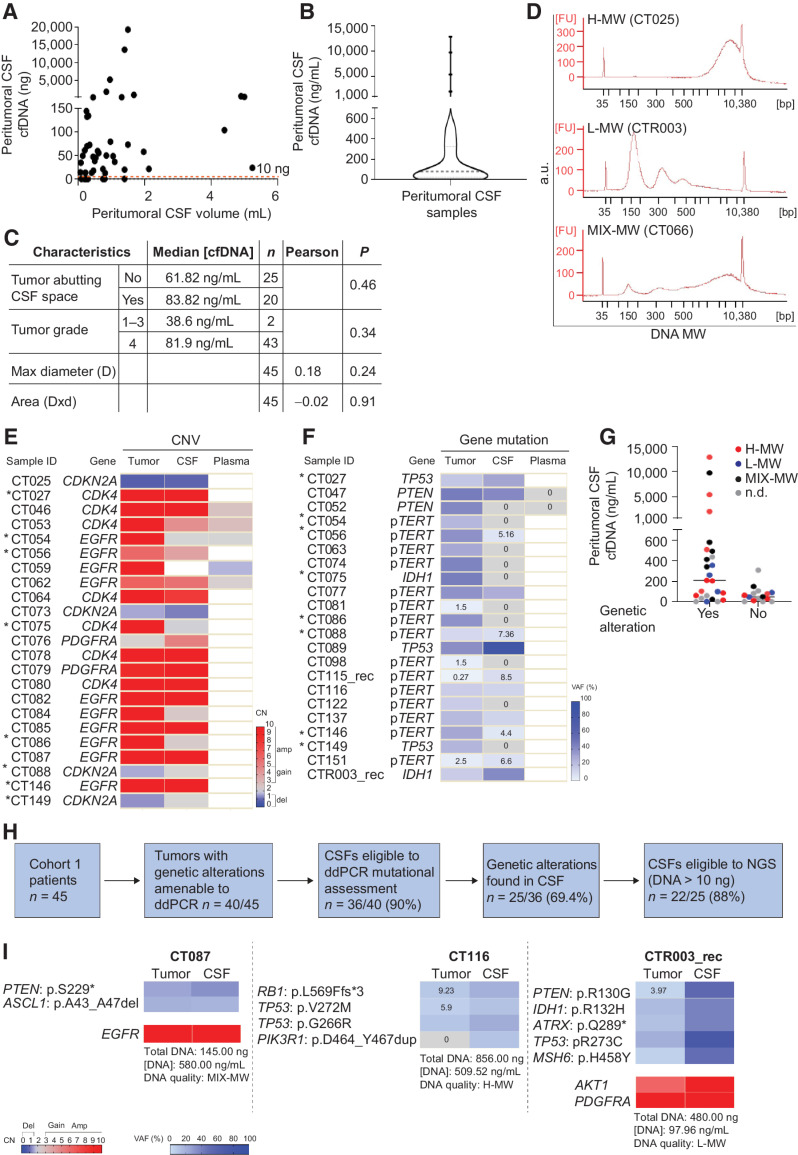

Cohort 1: Comparative analysis of peritumoral CSF and tumor tissues. A, Analysis of DNA amount versus CSF volume in peritumoral CSF samples from Cohort 1 (n = 45). Red line indicates the threshold of minimal DNA content (10 ng) for NGS analysis (Spearman correlation between total CSF DNA amount and volume, r = 0.36, P = 0.014). B, Analysis of cfDNA concentration in peritumoral CSF samples from Cohort 1 (n = 45). Gray line, median DNA concentration = 77.2 ng/mL. C, Correlation between peritumoral CSF cfDNA concentration and tumor features such as proximity to a CSF space (ventricle or cistern), tumor grade, and size. Median cfDNA concentrations were compared between groups defined by proximity to CSF space or tumor grades (non parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test). Maximal tumor diameter and areas (as reported in Supplementary Table S1) were correlated with cfDNA concentration in all CSF samples (Pearson correlation). n, number of tumors. D, cfDNA analysis showing the presence of either low (L) or high (H) or mixed (MIX) molecular weight (MW) DNA in representative CSF samples (Bioanalyzer output). E and F, Heatmaps showing peritumoral CSF samples eligible to ddPCR (n = 36) analyzed for selected genetic alterations found in the corresponding tumors. E, copy-number variations (CNV). Red, amplifications (CN > 5) and gains (3 < CN < 5); blue, deletions (CN < 1.5). Color legend for CNV is shown. F, Gene mutations. Color legend for VAF (variant allele frequency) is shown. VAF < 10% are reported. *, Samples tested for both CNV and mutations. G, Dot plot indicating cfDNA concentration and MW features in the groups of peritumoral CSF samples where tumor genetic alterations were detected (yes) or not (no) by ddPCR. No statistically significant association was found between DNA MW type and the possibility to detect mutations in CSF (χ2 test for a Ptrend = 0.39, df = 1). H, Flow-chart: Shortlisting of peritumoral CSF samples from sample collection to eligibility to NGS analysis. I, Comparative NGS analysis showing correspondence between matched peritumoral CSF cfDNAs and tumor tissue DNAs. CSF cfDNA total amount, concentration and quality (MW), and VAF < 10% are reported. Color legends for heatmaps (CN and VAF) are shown.

Figure 3.

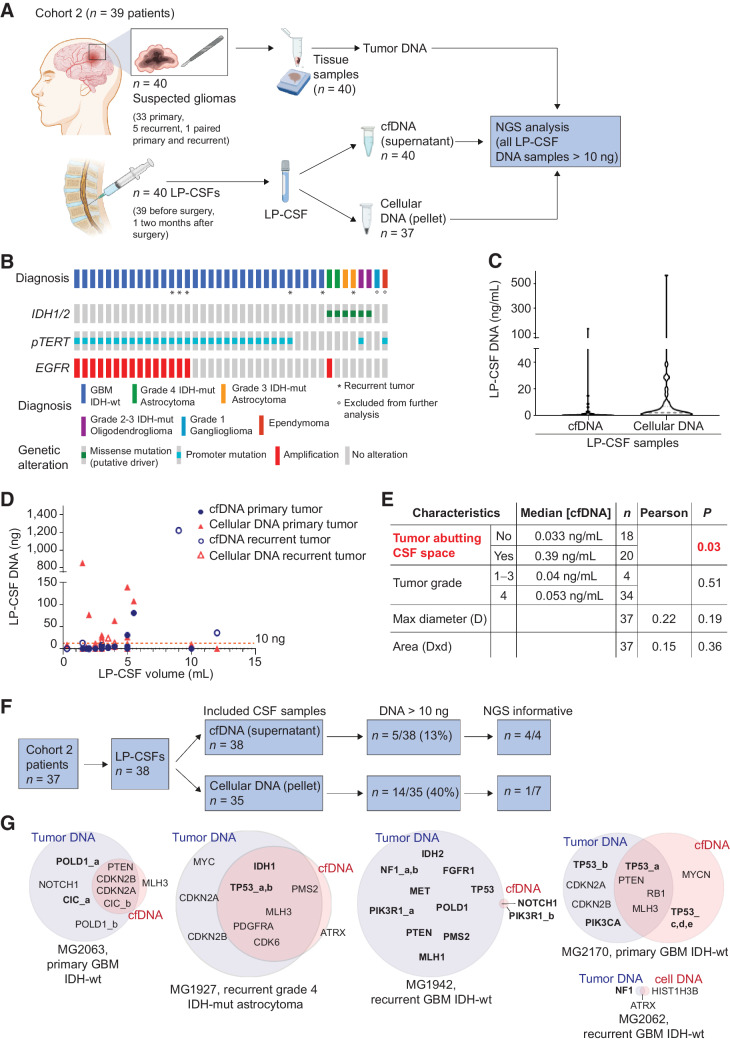

Cohort 2: LP-CSF NGS analysis. A, Experimental design. Cohort 2 patients yielded fresh or archive tumor tissues (n = 40) and CSF sampled by LP (LP-CSF, n = 40). From LP-CSF, DNA was recovered from either the supernatant (cfDNA) or the pellet (cellular DNA). Wherever possible, tumor tissue DNA and LP-CSF DNA were compared by NGS analysis. B, Oncoprint of Cohort 2 patients based on detection of IDH1/2 mutation by IHC, pTERT sequencing, and EGFR amplification analysis by FISH. C, Analysis of DNA concentration in LP-CSF samples (cfDNA from supernatants or cellular DNA from pellets) in Cohort 2. Gray line, Median DNA concentration (cfDNA = 0.05 ng/mL; cellular DNA = 2.14 ng/mL). D, Analysis of DNA amount (cfDNA from supernatants and cellular DNA from pellets) versus LP-CSF volume in samples from Cohort 2 (n = 38). Primary or recurrent tumors are indicated. Red line indicates the threshold of minimal DNA content (10 ng) required for NGS analysis (Spearman correlation between cfDNA amount and LP-CSF volume, r = 0.38, P = 0.021; between cellular DNA and LP-CSF volume, r = 0.10, P = 0.56). E, Correlation between tumor features (proximity to CSF space, tumor grade, and size) on the one hand, and LP-CSF cfDNA concentration on the other. Median DNA concentrations were compared between groups defined by proximity to CSF space or tumor grades (non parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test). Maximal tumor diameter and areas (as reported in Supplementary Table S9) were correlated with DNA concentration in LP-CSF samples (Pearson correlation). n, Number of tumors. Red, statistically significant correlation. F, Flow-chart, shortlisting of LP-CSF samples from collection to NGS eligibility and overall results. G, Venn diagrams summarizing NGS results, showing the degree of correspondence between paired LP-CSF (cfDNA or cellular DNA) and tumor tissue DNA. Pairing between tumor and LP-CSF was verified by SNP ID (Supplementary Data S3). Bold, single-nucleotide variations. Regular, copy-number variations. (A, Created with BioRender.com.)

Results

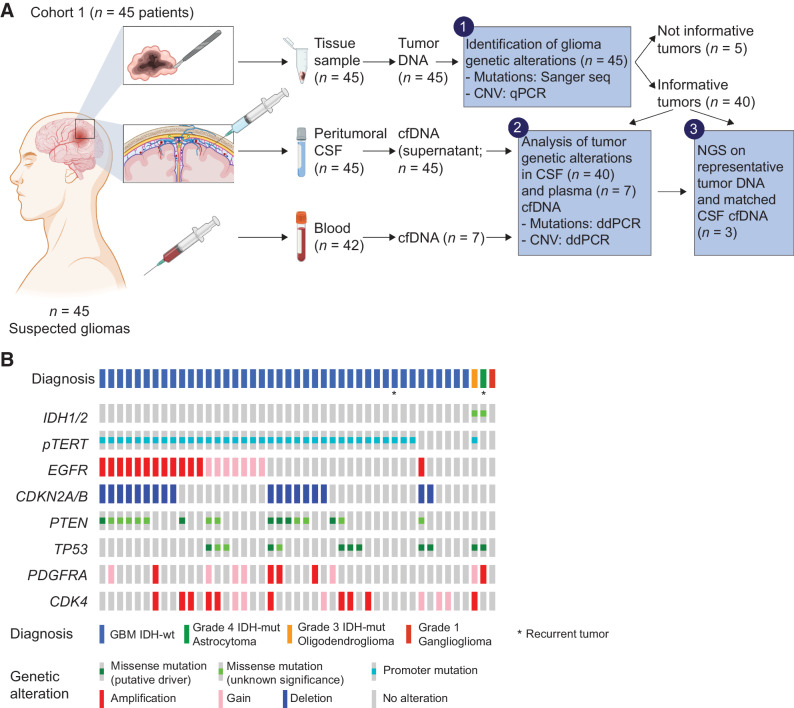

A glioma cohort for comparative analysis of peritumoral CSF and tumor tissue

To systematically investigate the feasibility of CSF liquid biopsy by NGS in newly diagnosed patients with glioma, we collected a cohort of 45 patients with presumptive primary GBM at the time of surgery (Cohort 1; Supplementary Table S1). From each patient, we retrieved a tumor tissue sample, a peritumoral CSF sample (cell-free supernatant) from brain liquoral spaces in proximity with the surgical field, and a blood sample, with the aim to assess whether the main genetic alterations found in tumor tissues could be detected in the matched CSF and blood plasma as well (Fig. 1A). DNA from each tissue sample (n = 45) was analyzed with Sanger sequencing or qPCR to investigate IDH1/2 status and the presence of additional alterations relevant for molecular characterization (TERT promoter mutation, EGFR amplification, and CDKN2A/B deep deletion; refs. 1, 2), or known to recur in at least 15% of the GBM population (PTEN and TP53 mutation, and PDGFRA and CDK4 amplification). After this analysis, 40/45 tumor tissues displayed at least one genetic alteration to be searched in CSF and plasma (Fig. 1A and B; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1.

Cohort 1: Experimental design for glioma and CSF comparative analysis, and tumor characterization. A, Experimental design. Cohort 1 patients provided fresh tumor tissues (n = 45), CSF sampled from liquoral spaces in proximity with the surgical field (peritumoral CSF, n = 45) and blood samples (n = 42). Tumor tissue DNA underwent analysis of frequently occurring glioma genetic alterations (by Sanger sequencing and qPCR, step 1). Genetic alterations of informative tumors were searched in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) isolated from CSF or blood plasma by ddPCR assays tailored on the specific sequence alterations (step 2). Selected tumor tissue and CSF DNA samples underwent NGS (step 3). B, Glioma histopathological and molecular diagnosis, and genetic alterations in a selected panel of GBM-associated genes, detected by Sanger sequencing (mutations) and qPCR analysis (copy-number variations) in tumor tissues. (A, Created with BioRender.com.)

Comparative targeted genetic analysis of peritumoral CSF and tumor tissues

Peritumoral CSF samples underwent quantitative cfDNA analysis, showing that the majority of samples (38/45) contained 10–200 ng of DNA, whereas the remaining 7/45 samples did not contain detectable DNA (median concentration of all samples: 77.2 ng/mL; Fig. 2A and B; Supplementary Table S3). A weak positive correlation between the CSF volume and its total cfDNA amount was found (r = 0.36, P = 0.014; Fig. 2A). The median CSF cfDNA concentration was higher in tumors defined as abutting the liquoral spaces versus those that were not, and in grade 4 tumors versus grade 1–3, although without reaching statistical significance. No correlation was observed between cfDNA concentration on the one hand and tumor size on the other (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Tables S1 and S3).

The cfDNA-qualitative analysis to determine DNA molecular weight (MW) showed that 6/45 samples contained only low-MW DNA, 16/45 contained only high-MW DNA, and 8/45 contained both low- and high-MW DNA; in the remaining 15/45 samples, the DNA MW profile could not be analyzed for technical reasons (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Table S3). In CSF from patients with brain tumor, the presence of low-MW DNA, derived from apoptotic tumor DNA fragmentation and supposed to be released in CSF by ultrafiltration, is expected (34). The unforeseen presence of poorly soluble high-MW DNA in 24/45 samples suggested that this DNA could derive from tumor cells that had accumulated in peritumoral CSF spaces. This conclusion was supported by experiments showing that GBM primary cells (neurospheres derived from Cohort 1 patients CT025 and CT151), after incubation in artificial CSF, could survive for days and then release high-MW DNA, likely after necrosis (Supplementary Fig. S1A–S1C).

Next, to verify whether CSF cfDNA contained circulating tumor DNA, genetic alterations found in tumor tissues were searched in the corresponding CSFs by highly sensitive and specific ddPCR assays (n = 40, including those where DNA could not be quantified; Fig. 2E and F; Supplementary Table S4). Excluding a fraction of CSF cfDNAs that failed to provide a positive control for ddPCR amplification (n = 4/40), in the remaining cases at least one genetic alteration, either a CNV, or gene mutation, could be found in 25/36 CSFs (Fig. 2E and F; Supplementary Table S4). A high amount of cfDNA was associated with high probability to detect circulating tumor DNA (χ2 for a Ptrend = 0.0096, df = 1), but it was not an absolute requirement. Indeed, 14/15 CSFs with high cfDNA concentration (>200 ng/mL) displayed the tumor alteration, whereas CSFs displaying a cfDNA concentration of 10–200 ng/mL, which represented the majority of cases, included cases that either displayed (n = 8/20) or not (n = 12/20) the tumor genetic alteration. Importantly, even 3/6 CSF samples with very low cfDNA concentration (<10 ng/mL) displayed the tumor mutation, attesting the extreme sensitivity of the ddPCR technique (Fig. 2G). Mutations were detected not only in low-MW but also in high-MW DNA, in comparable sample fractions (Fig. 2G), indicating that tumor cells invading CSF spaces may be a relevant source of cfDNA.

Blood plasma is known to rarely contain cfDNA released by adult gliomas (14). In line with previous observations, in 7/7 blood plasma analyzed we could not detect the genetic alterations present in tissues and CSFs (Fig. 2E and F; Supplementary Table S4), leading to discontinue plasma analysis.

In summary, in Cohort 1, 40/45 patients displayed, in their tumor tissues, at least one mutation suitable to the design of a ddPCR assay. Of these patients, 36/40 yielded peritumoral CSFs containing cfDNA that could be amplified for ddPCR and undergo assessment of the tumor genetic alteration. In 25/36 cfDNAs assessed by ddPCR, the tumor genetic alteration was detected, indicating the unequivocal presence of circulating tumor DNA in CSF. Of these 25 CSF samples, 22 provided the minimal DNA amount required for NGS (>10 ng; Fig. 2H). Within this group, 3 cases, including CSF samples representative of either low-, high-, or mixed DNA MW (Supplementary Table S3), were chosen to undergo the NGS analysis.

Comparative NGS analysis of peritumoral CSF and tumor DNA

The NGS analysis of peritumoral CSF and matched tumor tissue DNA (n = 3 pairs) was performed by using a panel, including 54 glioma-related genes (Supplementary Data S2). In both tissues and CSFs, NGS analysis confirmed the presence of the genetic alterations revealed by targeted analysis and detected additional alterations, identical in paired tissues and CSFs, with the exception of a PIK3R1 mutation, which was found at low frequency only in patient CT116 cfDNA. Moreover, NGS showed that VAFs and CNVs were increased in CSF cfDNAs compared with matched tissue DNAs, indicating that, at least in this sample panel, CSF was relatively enriched in tumor DNA (Fig. 2I; Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Data S2).

A prospective glioma cohort for analysis of CSF DNA retrieved by LP

The results of tumor and peritumoral CSF comparative analysis encouraged to explore the possibility to apply NGS to CSF collected by LP (hereafter indicated as LP-CSF), in view of potential application in daily clinical practice for patients with glioma ineligible to surgery, or for a longitudinal genomic monitoring over the course of treatments. As systematic information on LP-CSF reliability for NGS analysis of newly diagnosed gliomas is missing (6, 7), we collected a prospective cohort of 39 patients with suspected gliomas based on radiologic criteria and eligible to surgery (Cohort 2, Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S6). Cohort 2 provided 33 primary, 5 recurrent, and a pair of primary and recurrent tumors from the same patient (MG2049), for a total of 40 tumor samples (Fig. 3A). LP-CSFs were mostly collected immediately before surgery (n = 39) or, in one case, 2 months after the first surgery, during LP to relieve hydrocephalus, for a total of 40 LP-CSFs (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S6). Considering that analysis of peritumoral cfDNA showed the frequent presence of high-MW DNA (Fig. 2D and G), which is likely released from cells invading CSF spaces, and that glioma cells can survive longtime in the CSF milieu (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B), in most cases (n = 37) we extracted DNA not only from CSF supernatants (cfDNA), but also from intact cells contained in CSF pellets (cellular DNA; Fig. 3A). CSF supernatants were expected to contain both low- and high-MW DNA, while CSF pellets were expected to contain mostly high-MW DNA.

After surgery, tumor tissues underwent routine histopathological diagnosis and analysis of IDH1/2 mutation, pTERT and EGFR amplification, leading to diagnose 31 GBM IDH-wt, 4 IDH-mutant (IDH-mut) astrocytomas, 2 IDH-mut oligodendrogliomas, 1 ependymoma, and 1 ganglioglioma (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). Ependymoma and ganglioglioma were excluded from the study as they are rare entities, not classified as adult-type diffuse gliomas, and displaying a distinct molecular profile. Tumor tissues were further exploited to validate NGS analysis of LP-CSF (Fig. 3A).

In Cohort 2, LP-CSF displayed a modest median DNA concentration of 0.05 ng/mL in the supernatant and 2.14 ng/mL in the pellet (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Table S8), remarkably lower than the median cfDNA concentration (77.2 ng/mL) found in peritumoral CSFs (Cohort 1, Fig. 2B). Like in Cohort 1, a weak positive correlation between the LP-CSF volume and its DNA content was found (Fig. 3D; correlation between cfDNA amount and LP-CSF volume, r = 0.38, P = 0.021; between cellular DNA and LP-CSF volume, r = 0.10, P = 0.56). Interestingly, the median cfDNA concentration in LP-CSF from newly diagnosed tumors was lower than in recurrent tumors, without reaching statistical significance (0.04 ng/mL vs. 0.81 ng/mL, Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.13; Supplementary Table S8). DNA-qualitative analysis of LP-CSF supernatants (feasible only in 8/40 samples) showed that 5/8 samples contained only low-MW DNA, 2/8 mixed-MW DNA, and 1/8 only high-MW DNA. As expected, cellular DNA was invariably high-MW (Supplementary Table S8).

As previously reported (15), in Cohort 2, a significant correlation was found between median LP-CSF cfDNA concentration and tumor proximity with liquoral spaces, again supporting the notion that CSF cfDNA mostly derives from cells invading such spaces (Fig. 3E; Supplementary Table S9). No correlation was found between LP-CSF cfDNA concentration and tumor grade, or tumor size (tumor maximal diameter or tumor area; Fig. 3E), or tumor progression (Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B).

Overall, in Cohort 2 patients, the minimal absolute DNA quantity required for NGS (10 ng) was reached in only 5/38 cfDNA samples from supernatants and in 14/35 cellular DNA samples from pellets, for a total of 19/73 samples. These samples corresponded to 16/37 patients, including 10/31 primary and 6/6 recurrent gliomas (Fig. 3D and F; Supplementary Table S8).

Comparative NGS analysis of LP-CSF and tumor DNA

Eleven LP-CSF samples containing at least 10 ng of DNA, including 4/5 cfDNAs (corresponding to 2 primary and 2 recurrent tumors) and 7/14 cellular DNAs (corresponding to 6 primary and 1 recurrent tumor), underwent NGS analysis together with the corresponding tumor tissues. NGS detected genetic alterations in 4/4 LP-CSF cfDNAs (corresponding to 2/32 primary and 2/6 recurrent tumors) and in 1/7 cellular DNAs (corresponding to the recurrent tumor), indicating that most cellular DNAs seem to be of non-tumor origin (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Table S10). Unlike in peritumoral cfDNA (Cohort 1), where an almost perfect match with tumor genetic alterations was found (Fig. 2I), in the case of LP-CSF cfDNA the overlapping degree was only partial, and a variable number of private alterations in either tumor or CSF were detected (Fig. 3G; Supplementary Fig. S3A–S3F, Supplementary Table S10, and Supplementary Data S2). These data suggest that CSF may contain subclone(s) different from those sampled in glioma tissues, well known to encompass a complex subclonal composition (35, 36).

Considering the current sensitivity limits of NGS, the low quantity of cfDNA in LP-CSF (>10 ng in only 5/38 samples) and the low rate of NGS success in cellular DNA (informative in only 1/7 cases tested), it can be concluded that attempting NGS in LP-CSF of patients with primary untreated gliomas may be debatable.

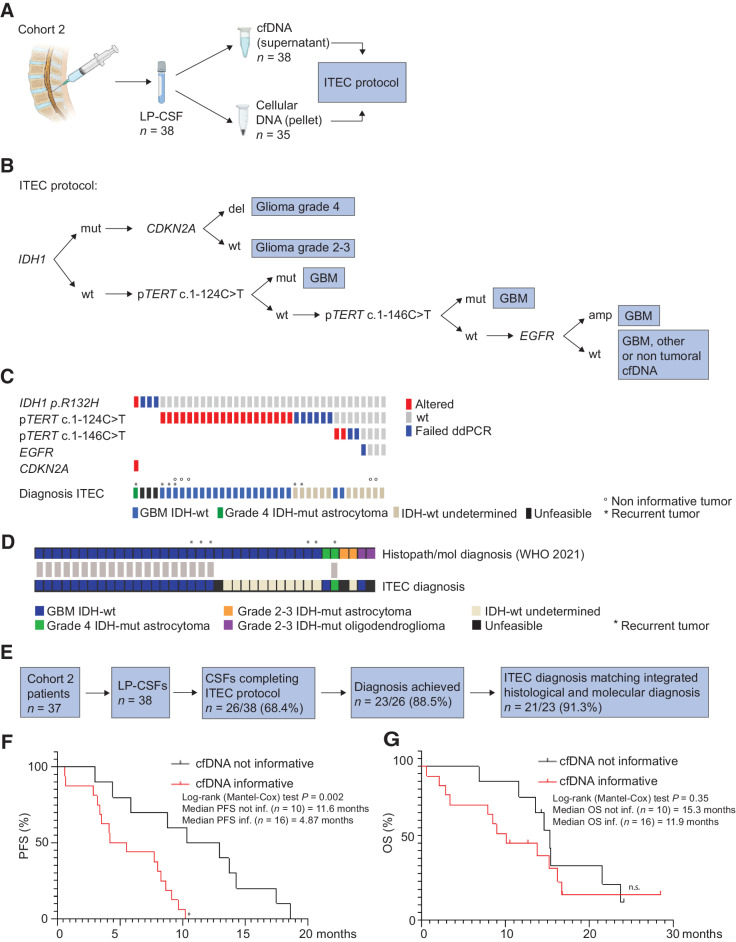

Design of LP-CSF DNA analysis by a selected panel of genetic alterations: the ITEC protocol

Next, we reasoned that: (i) cfDNA amounts found in CSF are within the sensitivity range of ddPCR, as shown by successful detection of tumor alterations in peritumoral CSF with undetectable DNA (Fig. 2E–G); (ii) a limited set of genetic alterations (IDH1/2 mutation, pTERT mutations, EGFR amplification, and CDKN2A/2B homozygous deletion) is currently recommended to achieve differential diagnosis between main glioma molecular subgroups, including IDH WT GBM on the one hand, and IDH-mut astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma on the other (1, 2); (iii) at least three ddPCR-independent analyses should be compatible with the scanty DNA amounts recovered from LP-CSF. Indeed, the ddPCR sensitivity threshold for the above mutations is 10−2 ng DNA, as we measured by limiting dilution experiments (Supplementary Fig. S4A–S4F). Therefore, we set out to systematically analyze LP-CSF DNA (both cfDNA from supernatants and cellular DNA from pellets) by a multi-step ddPCR protocol (IDH1-pTERT-EGFR-CDKN2A protocol, hereafter named as ITEC; Fig. 4A and B). ITEC starts with analysis of IDH1 mutation R132H, accounting for 88.2% of overall IDH1/2 mutations (www.cbioportal.org) and used to discriminate IDH-wt GBM from IDH-mut gliomas (1, 2). IDH1-mut cases are then assessed for CDKN2A homozygous deletion, which associates with poor prognosis and identifies grade 4 gliomas (1, 2). IDH1-wt DNAs (which, in principle, may include GBM, other tumor and non-tumor DNAs) are analyzed for pTERT mutations (c.1–124C>T and, if negative, c.1–146C>T). As pTERT mutations are cumulatively expected to occur in approximately 90% of IDH-wt GBM (37), combination of IDH1-wt and pTERT mutations is highly suggestive of GBM diagnosis (Fig. 4B; refs. 1, 2). In IDH1-wt and pTERT-wt cases, EGFR amplification (expected in 55% of GBM; www.cbioportal.org) is searched to support GBM diagnosis (Fig. 4B; refs. 1, 2). We envisaged that one or more ITEC steps could fail, or that all the analyses could detect a WT status, leaving the diagnosis inconclusive (Fig. 4B). However, considering the frequency of the investigated genetic alterations and ddPCR assay sensitivity, we foresaw to reach a molecular diagnosis in at least 50% of cases.

Figure 4.

Cohort 2: Targeted analysis of LP-CSF for glioma differential diagnosis. A, Experimental design. In Cohort 2 patients with glioma, DNA recovered from LP-CSF (n = 38), either from supernatant (cfDNA, n = 38) or pellet (cellular DNA, n = 35), underwent the ITEC protocol. B, Schematic of ITEC protocol. C, Oncoprint of genetic alterations detected through the ITEC protocol and the resulting diagnosis according to WHO 2021 definitions. IDH-wt undetermined, GBM or other tumor type or non-tumoral DNA; unfeasible, ITEC protocol stopped at first step. D, Graph showing concordance (gray bars) between diagnosis based on histopathological and molecular criteria (according to WHO 2021) and ITEC-based molecular diagnosis. E, Flowchart, sample shortlisting from LP-CSF sample collection to ITEC protocol outcome. F and G, Correlation between attainment of ITEC diagnosis and progression-free survival (PFS, significant; F) and overall survival of primary patients with GBM (not significant but in the same trend; G). (A, Created with BioRender.com.)

LP-CSF DNA analysis by the ITEC protocol

ITEC analysis of 38 LP-CSFs showed that the first step (IDH1 mutation) could be accomplished in 35/38 cases, whereas it failed in the remaining 3/38 cases, likely for insufficient DNA, leading to protocol termination (diagnosis defined as “unfeasible,”; Fig. 4C; Table 1; Supplementary Table S11). Among the above 35 samples, IDH1 R132H mutation was detected in 1 case, followed by identification of CDKN2A homozygous deletion, together supporting the diagnosis of grade 4 IDH-mut glioma (Fig. 4C; Table 1; Supplementary Table S11). Among IDH1-wt cases, 22/34 were pTERT mutated (either c.1–124C>T or c.1–146C>T), supporting GBM diagnosis (cases defined as “GBM IDH-wt,”; Fig. 4C; Table 1; Supplementary Table S11). In the remaining 12/34 cases (“IDH-wt undetermined”), the molecular diagnosis was not informative, because all the genetic alterations tested were WT (3/12 cases) or the protocol failed at the pTERT or EGFR step for DNA exhaustion (9/12 cases; Fig. 4C; Table 1; Supplementary Table S11). In these 12 cases, it remains undetermined whether CSF DNA was non-tumoral or related to an IDH-wt/pTERT-wt/EGFR-wt GBM (or to another IDH-wt brain tumor). Indeed, 2 LP-CSF defined as “IDH-wt undetermined” corresponded to GBM tumor tissues that were concomitantly IDH, pTERT, and EGFR-wt (non-informative GBMs: MG2051, MG2056; Fig. 4C; Table 1; Supplementary Tables S6, S7, and S11). Of note, 3 GBM cases, reported to be pTERT-wt by tissue analysis through Sanger sequencing, provided LP-CSF DNA where pTERT mutation was detected, likely as result of ddPCR higher sensitivity (MG2057, MG2062_rec, and MG2064), allowing to reach the molecular diagnosis of GBM IDH-wt (Fig. 4C; Table 1; Supplementary Tables S7 and S11).

Table 1.

Cohort 2, ITEC protocol results (ddPCR).

| Sample ID | IDH1 | pTERTa | pTERTb | EGFR | CDKN2A | Histopath./mol. diagnosis (WHO 2021) | ITEC diagnosis | Matched diagnosis | DNA type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG1926 | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GBM IDH-wt | Unfeasible | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG1927_rec | mut | — | — | — | del | Grade 4 IDH-mut astrocytoma | Grade 4 IDH-mut astrocytoma | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG1928 | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Grade 3 IDH-mut astrocytoma | Unfeasible | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG1938 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG1942_rec | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG1943 | wtc | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | — | Grade 3 IDH-mut astrocytoma | IDH-wt undetermined | No | cfDNA |

| MG1944 | wt | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG1945 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2046 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2047 | wt | wt | wt | Failed | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2048 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | Both |

| MG2049 | wt | wt | Failed | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2049_rec | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2050 | wt | wt | mut | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2051d | wt | wt | wt | wt | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2052 | wt | wt | Failed | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2053 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2054 | wt | wt | mut | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2055_rec | wt | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2056d | wt | wt | wt | wt | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2057d | wt | mutc | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2058_rec | wt | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2059 | wt | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2060 | wt | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2061 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2062_recd | wt | mutc | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2063 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2064d | wt | mutc | — | — | — | Grade 4 IDH2-mut astrocytoma | GBM-IDH wt | No | cfDNA |

| MG2065 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2166 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | Both |

| MG2168 | Failed | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Grade 2 IDH-mut oligodendroglioma | Unfeasible | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2169 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2170 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | Both |

| MG2171 | wt | wt | wt | wt | — | GBM IDH-wt | IDH-wt undetermined | n.d. | cfDNA |

| MG2172 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2173 | wtc | mute | — | — | — | Grade 3 IDH-mut oligodendroglioma | GBM IDH-wt | No | cellDNA |

| MG2177 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

| MG2179 | wt | mut | — | — | — | GBM IDH-wt | GBM IDH-wt | Yes | cfDNA |

Abbreviations: n.a., not assessed, after failure of IDH1 or pTERT analysis; —, not assessed, after protocol termination; n.d., not determined.

apTERT mutation c.1–124C>T.

bpTERT mutation c.1–146C>T.

cCSF discordant from tissue molecular diagnosis (Supplementary Table S7).

dIDH1-wt and pTERT-wt “non-informative” tumors (Supplementary Table S7).

epTERT mutation detected only in CSF cellular DNA.

Concerning the LP-CSF fraction (supernatant or cellular pellet) containing tumor DNA, in all cases but one (n = 22/23) mutations were found in cfDNA from supernatant (Table 1). Cellular DNAs from pellets were mostly WT, except in 4 cases (Table 1; Supplementary Table S11). Interestingly, in 1/4 cases, tumor genetic alterations were found in cellular but not in cfDNA. These data suggest that LP-CSF cfDNA should be analyzed in the first place, but cellular DNA from pellet should not be discarded in principle.

Comparison between ITEC and standard tissue diagnosis

Molecular diagnosis reached by the ITEC protocol was consistent with histopathological and molecular diagnosis performed on tissues according to WHO 2021 guidelines (1, 2), at least as far as GBM IDH-wt are concerned (Fig. 4D; Table 1). The majority of cases defined as GBM IDH-wt by tissue histopathological and molecular diagnosis (n = 32) were either recognized (20/32), or at least defined as IDH-wt (11/32), whereas only 1/32 remained as fully undetermined (unfeasible) by ITEC (Fig. 4D; Table 1). Among tumors defined as IDH-mut astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma by tissue diagnosis (n = 6), the ITEC outcome was less informative (Fig. 4D; Table 1). Beside the grade 4 IDH-mut astrocytoma (MG1927, see above), which was correctly identified by ITEC as a high-grade glioma, 2/6 low-grade cases failed at the first ITEC step (MG1928: grade 3 astrocytoma, MG2168: grade 2 oligodendroglioma; both defined as “unfeasible diagnosis”; Fig. 4D; Table 1). In the remaining 3/6 cases, ITEC failed to identify IDH1 R132H mutation: MG1943 (grade 3 IDH-mut astrocytoma) failed at the ensuing pTERT step and remained as a “IDH-wt undetermined,” possibly because LP-CSF DNA was non-tumoral (Fig. 4D; Table 1). In two other cases (MG2064 and MG2173), ITEC reached a diagnosis inconsistent with tissue histopathological and molecular characterization. A grade 4 astrocytoma (MG2064) could not be recognized as IDH-mut because it was a rare case of IDH2 rather than IDH1 mutant, and it was identified by ITEC as GBM IDH-wt for the presence of pTERT mutation (Fig. 4C and D; Table 1; Supplementary Table S7). Such pTERT mutation was not detected in the tumor tissue, where, however, EGFR amplification was found, leaving open the possibility that this tumor had ambiguous features; in any case, this tumor was assigned with grade 4 by histopathology (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). The second case of inconsistency between ITEC and histopathological diagnosis was a typical 1p/19q co-deleted, IDH1-mut oligodendroglioma (MG2173). In this case, ITEC failed to detect IDH1 mutation, but it detected pTERT mutation (found also in tissue), leading to the definition of GBM IDH-wt (Fig. 4D; Table 1; Supplementary Table S7).

In summary, the ITEC protocol could be completed in 26/38 LP-CSFs, allowing to reach a molecular diagnosis in 23/26 cases. ITEC diagnosis matched integrated histological and molecular diagnosis in 21/23 cases, correctly identifying 20/32 GBM IDH-wt and 1/6 IDH-mut tumors (Fig. 4D and E; Table 1). Interestingly, within the newly diagnosed GBM group (n = 26) there was a significant correlation between shorter PFS (but not OS) on the one hand, and the possibility to reach an ITEC diagnosis, that is, to retrieve informative DNA in LP-CSF (Fig. 4F and G; Table 1; Supplementary Table S12). These data, together with the inconclusive ITEC results in the majority of lower grade tumors, are consistent with the notion that the presence of tumor DNA in LP-CSF is a sign of tumor aggressiveness.

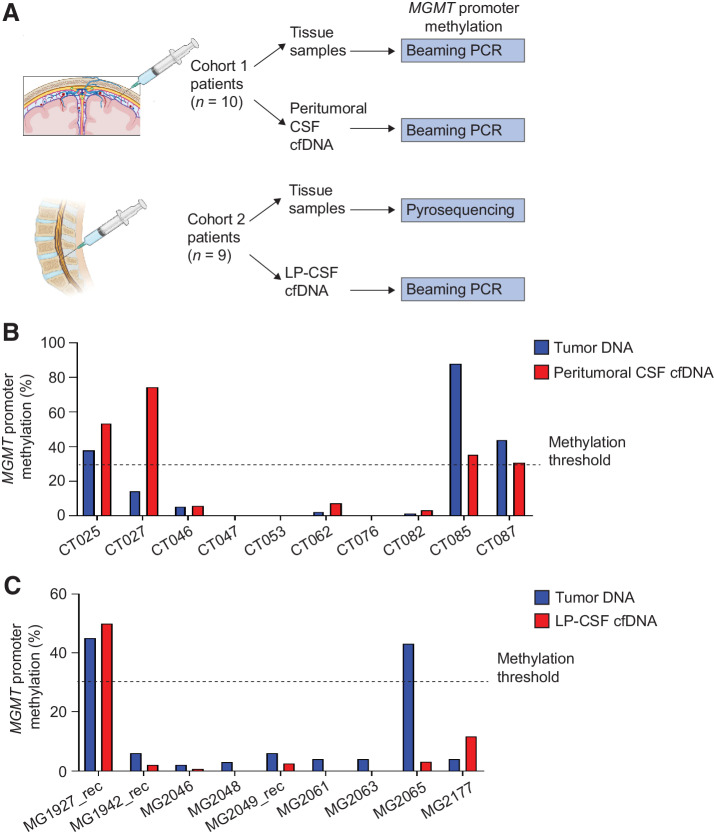

Detection of MGMT promoter methylation in peritumoral and LP-CSF DNA

Beside genetic diagnosis, another clinically relevant marker is MGMT promoter methylation, which predicts response to the alkylating agent temozolomide (38). A panel of CSF cfDNAs was chosen from both Cohorts 1 (n = 10 primary GBM IDH-wt) and 2 (n = 9, including 6 primary and 2 recurrent GBM IDH-wt, and 1 recurrent grade 4 IDH-mut astrocytoma), based on sample availability after completion of respective genetic analysis protocols by ddPCR and/or NGS. CSF samples underwent MGMT promoter methylation analysis by beaming PCR, whereas matched tissues were analyzed by the same methodology in Cohort 1, or by pyrosequencing as part of routine diagnosis in Cohort 2 (Fig. 5A). In Cohort 1, this analysis revealed full concordance between peritumoral CSF and tumor DNA in 9/10 cases, whereas, in 1/10 cases, MGMT promoter methylation was detected in CSF but not in tissue (Fig. 5B; Supplementary Table S13). Also, in Cohort 2 full concordance between matched tumors and LP-CSFs was observed in 8/9 cases, whereas in the remaining case MGMT promoter methylation was detected in tissue but completely absent in LP-CSF (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Table S13).

Figure 5.

Cohort 1 and 2: MGMT promoter methylation in peritumoral and LP-CSF cfDNA. A, Experimental design. A panel of matched tumor tissues and CSFs (Cohort 1, n = 10; Cohort 2: n = 9) underwent evaluation of MGMT promoter methylation either by beaming PCR or pyrosequencing. B, Cohort 1, the percentage of MGMT promoter methylation measured by beaming PCR in a panel of matched tumor DNAs and peritumoral CSF cfDNAs. C, Cohort 2, the percentage of MGMT promoter methylation measured in a panel of matched tumor DNAs (pyrosequencing) and LP-CSF cfDNAs (beaming PCR). Dotted line, threshold to define MGMT promoter methylation (30%). (A, Created with BioRender.com.)

This analysis demonstrates general feasibility of MGMT promoter methylation detection in LP-CSF cfDNA in both recurrent and first presentation tumors. However, the DNA quantity required for this analysis is relatively high and, considering the expected overall DNA amounts retrievable from LP-CSF, will require careful prioritization.

Discussion

In patients with primary brain tumors, previous work showed that tumor DNA can be retrieved from CSF and exploited to perform comprehensive NGS, as well as more targeted analysis with high-sensitivity methodologies (16–18, 22). However, relevant questions remain open in view of systematic clinical translation of CSF-based liquid biopsy, in particular whether a broad genetic characterization is feasible in gliomas at first diagnosis. To address these issues, in the present study we analyzed two separate cohorts of newly diagnosed patients with glioma, one providing peritumoral CSF collected during surgical procedures (Cohort 1), the other affording CSF by LP immediately before surgery (Cohort 2). In both cohorts, tumor tissue and CSF genetic alterations could be systematically compared.

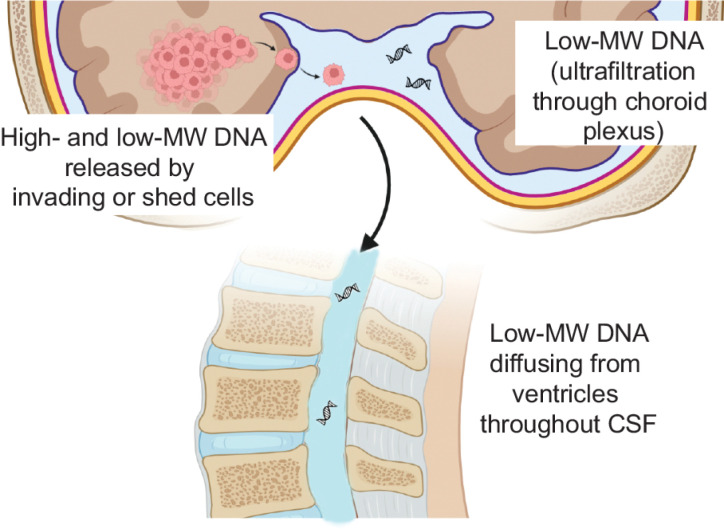

Consistently with previous studies (14, 16), in Cohort 1 we found that peritumoral CSF often contains relatively high cfDNA concentrations, which, through collection of a few CSF milliliters, provided DNA amounts sufficient to perform a reliable NGS analysis. However, by peritumoral cfDNA-qualitative analysis, we observed previously unreported or unappreciated features, which may strongly affect tumor DNA circulation in CSF and, eventually, if and how to perform CSF liquid biopsy. In more than half peritumoral CSFs, DNA displayed, at least in part, high MW while harboring tumor-specific mutations. This evidence supports that CSF DNA can often come from tumor cells that invaded liquoral spaces, or that it can be released by shedding from the surface of tumors grown up to touch such spaces. Indeed, microanatomical considerations indicate that tumor DNA can transfer into CSF only minimally by ultrafiltration through the choroid plexus barrier: the latter can be crossed only by low-MW molecules (as testified by CSF physiological composition) and, unlike the brain–blood barrier, given its circumscribed localization, it is unlikely disrupted by brain tumors. Together with such observations and considerations, our experiments, showing that glioma cells can survive in CSF for a few days and then release high-MW DNA (likely by necrosis), support a scenario in which glioma cells invading liquoral spaces release their DNA close to the tumor, where DNA can be abundantly retrieved (Fig. 6). Such DNA origin (cells actively invading CSF, or shed from tumors touching liquoral spaces) and DNA features (high-MW) greatly affect DNA circulation within CSF, and the possibility to retrieve tumor DNA at a distance from peritumoral CSF reservoirs. Indeed, high-MW DNA is poorly soluble and thus it is expected to remain concentrated close to cells that released it (Fig. 6). Tumor cells invading liquoral spaces could in principle circulate throughout CSF, making possible their collection (or collection of DNA released by them) at a remarkable distance from their site of invasion, for example, by LP.

Figure 6.

Features and origins of DNA found in CSF. Evidence provided in this study supports that brain tumor DNA found in CSF mostly derives from tumor cells invading liquoral spaces (or shed from tumors touching liquoral spaces), which can release both high- and low-molecular weight (MW) DNA as result of necrosis and/or apoptosis, respectively. A small amount of low-MW DNA is expected to be secreted into CSF by ultrafiltration at the physiological site of CSF formation (choroid plexus). High-MW DNA is poorly soluble and minimally diffuses throughout CSF. Low-MW DNA is soluble, but the slow dynamic of CSF circulation can prevent its diffusion from the site of cell invasion to the distant point of CSF collection (lumbar puncture). (Created with BioRender.com.)

However, analysis of our second patient cohort indicates that cell-free tumor DNA, or intact tumor cells, are scanty in LP-CSF of newly diagnosed patients with glioma, supporting a scenario where tumor DNA or cell shedding gradients rapidly fade away by departing from the tumor (Fig. 6). This is not surprising, as the low CSF pressure, and CSF circulation speed and direction are unlikely to support vigorous molecular or cellular diffusion. In our cohort, considering both LP-CSF cfDNA and cellular DNA (usually discarded in CSF liquid biopsy), 16/37 patients provided sufficient DNA (at least 10 ng) to perform NGS. However, because tumor genetic alterations were detected in all cfDNA tested, but only in a small fraction of cellular DNAs (1/7 tested), and cfDNA retrieved from LP-CSF is usually scanty, the fraction of patients expected to provide an informative NGS result is <20%, and even lower considering only newly diagnosed patients with gliomas. Conversely, Miller and colleagues (18) reported the presence of sufficient tumor DNA for NGS analysis in CSF cfDNA of 42/85 patients with glioma who underwent LP following clinical indications. However, in this study, CSF was collected long after surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, when the tumor was likely progressing toward a more aggressive and invasive stage, and therapies themselves could have favored tumor cell spread to liquoral spaces.

Although in our cohort the number of LP-CSFs eligible to NGS was limited, our study was designed to provide a still missing systematic comparison between LP-CSF and tumor tissue DNA. Concordance between each tumor tissue DNA and its matched LP-CSF DNA was only partial, with several genetic alterations shared and a few alterations private either to the tumor tissue or to LP-CSF. Although the pathogenic meaning of such private alterations remains to be determined, these results suggest that LP-CSF DNA may represent only a fraction of the subclonal composition of the tumor tissue, possibly corresponding to cells endowed with greater ability to invade CSF. These findings, together with the current sensitivity limits of capture-based NGS techniques (elective to detect CNVs, critical for glioma characterization) discourage the clinical use of LP-CSF liquid biopsy for extensive genetic characterization of diffuse gliomas at first clinical presentation.

Nonetheless, the amount of DNA retrieved from LP-CSF was within the sensitivity range of ddPCR, suggesting the possibility to analyze only the few molecular alterations essential for the differential diagnosis of adult-type diffuse glioma subgroups (in particular GBM IDH-wt on the one hand and IDH-mut astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas on the other), according to the 2021 WHO classification of central nervous system tumors (1, 2). We therefore set up the multi-step ddPCR protocol named ITEC, sequentially analyzing IDHR132H mutation, pTERT mutations, EGFR amplification, CDKN2A homozygous deletion. When at least one genetic alteration was detected (in particular IDH1 or pTERT mutation), the degree of diagnostic concordance between the ITEC protocol and the histo-molecular examination of tumor tissues was overall very satisfactory (91.3%; 21/23 cases).

The ITEC protocol performed well in recognizing IDH-wt GBMs (20/32 identified as IDH-wt/pTERTmut), whereas it was less informative in the 6 cases of IDH-mut gliomas. In one case, ITEC recognized a grade 4 IDH-mut recurrent glioma; in the remaining cases, ITEC failed likely for lack of tumor DNA in CSF (3 cases) or for the presence of a rare IDH2 rather than IDH1 mutation; only a grade 3 oligodendroglioma was misdiagnosed for a GBM IDH-wt, as IDH1 mutation was not recognized and pTERT mutation was found. The latter case suggested the occurrence of a false-negative IDH1 R132H detection, as reported in blood-based ddPCR of IDH-mut advanced cholangiocarcinoma (39), but it could not rule out true negativity resulting from tumor genetic heterogeneity. Overall, in lower-grade gliomas (and in part of GBMs), ITEC can be unfeasible owing to reduced aggressiveness and propensity to invade liquoral spaces, and thus to release tumor DNA in CSF. Consistently, in our exploratory analysis, newly diagnosed patients with GBM that were identified by ITEC showed shorter PFS as compared with those that were not, likely because more aggressive tumors released a greater amount of tumor DNA in the CSF.

In spite of the above limitations, ITEC could split patients with glioma into the two main molecular subgroups (IDH-wt vs. IDH-mut) carrying a different prognosis and therapeutic approach. Acquiring this information by a minimally invasive and overall safe (as no adverse events were registered in our cohort) LP-CSF collection might hire an extraordinary clinical significance in the management of all those cases where anatomical location or patient's comorbidities make surgical procedures challenging or simply unfeasible, or where conventional sampling methods fail to be informative. In the current formulation, the ITEC protocol does not allow a distinction between IDH-mut tumors of astrocytic and oligodendroglial origin, which could be made possible by including a test assessing chromosome 1p/19q co-deletion, representing the molecular signature of oligodendrogliomas. However, in the current clinical practice, the standard post-surgical treatment for high-risk IDH-mut tumors, consisting of radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy, does not differ regardless of histology. Clinicians might be helped in the differential diagnosis process by a careful revision of brain MRI, including perfusion-weighted sequences, looking for typical radiological features of oligodendroglial tumors.

We can conclude that the ITEC protocol can be proposed as an alternative to broad genetic characterization for suspected gliomas not surgically approachable, at first diagnosis and during longitudinal follow-up. Although suffering from an absolute limitation such as lack of sufficient tumor DNA in LP-CSF, which could be at least in part overcome by repeating CSF collection, the protocol is flexible and amenable to introduction of tests for detection of additional or alternative genetic alterations, useful to stratify or monitor patients in much needed clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Tables S1-S13, Description of Supplementary Data 1-3, Supplementary Materials and Methods, Supplementary References.

Primers and probes.

NGS analysis - Complete dataset.

SNP ID.

Acknowledgments

Schemes (Figs. 1A, 3A, 4A, 5A, and 6) were created with BioRender.com. We thank F. Di Nicolantonio for discussion; R. Altieri for help with patients’ management; and G. Reato, E. Casanova, M. Prelli, A. Bartolini, B. Mussolin, B. Martinoglio, R. Porporato, S. Gilardi, V. Pessei, and L. Pasqualini, for technical help. This work was supported by AIRC—Italian Association for Cancer Research Investigator grant nos. 19933 (to C. Boccaccio) and 23820 (to P.M. Comoglio); Comitato per Albi98 (to C. Boccaccio); Italian Ministry of Health RC 2022 (to C. Boccaccio); IOV intramural research grant 2017–5 × 1000 (MAGIC-2; to S. Indraccolo); and Italian Ministry of Health, Alleanza Contro il Cancro (ACC) Network Project RCR-2021–23671213 (to S. Indraccolo, C. Boccaccio, and M. Simonelli).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This article is featured in Highlights of This Issue, p. 1161

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

A. Gasparini reports other support from Thermo Fisher Scientific outside the submitted work. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors' Contributions

F. Orzan: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. F. De Bacco: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. E. Lazzarini: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation. G. Crisafulli: Data curation, formal analysis, validation. A. Gasparini: Data curation, investigation, methodology. A. Dipasquale: Resources, data curation, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. L. Barault: Data curation, investigation, methodology. M. Macagno: Data curation, investigation. P. Persico: Resources. F. Pessina: Resources. B. Bono: Resources. L. Giordano: Formal analysis. P. Zeppa: Resources, data curation. A. Melcarne: Resources. P. Cassoni: Resources. D. Garbossa: Resources, supervision. A. Santoro: Resources, supervision. P.M. Comoglio: Supervision, funding acquisition. S. Indraccolo: Data curation, supervision, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration. M. Simonelli: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, supervision, funding acquisition, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing. C. Boccaccio: Conceptualization, data curation, supervision, funding acquisition, visualization, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol 2021;23:1231–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M, Le Rhun E, Tonn JC, Minniti G, et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021;18:170–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wen PY, Packer RJ. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: clinical implications. Neuro Oncol 2021;23:1215–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chakravarty D, Solit DB. Clinical cancer genomic profiling. Nat Rev Genet 2021;22:483–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nicholson JG, Fine HA. Diffuse glioma heterogeneity and its therapeutic implications. Cancer Discov 2021;11:575–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simonelli M, Dipasquale A, Orzan F, Lorenzi E, Persico P, Navarria P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tumor DNA for liquid biopsy in glioma patients' management: close to the clinic? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020;146:102879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Escudero L, Martínez-Ricarte F, Seoane J. ctDNA-based liquid biopsy of cerebrospinal fluid in brain cancer. Cancers 2021;13:1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soffietti R, Bettegowda C, Mellinghoff IK, Warren KE, Ahluwalia MS, De Groot JF, et al. Liquid biopsy in gliomas: a RANO review and proposals for clinical applications. Neuro Oncol 2022;24:855–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mellinghoff IK, Ellingson BM, Touat M, Maher E, De La Fuente MI, Holdhoff M, et al. Ivosidenib in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 - mutated advanced glioma. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wen PY, Stein A, van den Bent M, De Greve J, Wick A, de Vos FYFL, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600E-mutant low-grade and high-grade glioma (ROAR): a multicentre, open-label single-arm, phase 2, basket trial. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doz F, van Tilburg CM, Geoerger B, Højgaard M, Øra I, Boni V, et al. Efficacy and safety of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive primary central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol 2022;24:997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meric-Bernstam F, Bahleda R, Hierro C, Sanson M, Bridgewater J, Arkenau HT, et al. Futibatinib, an irreversible FGFR1–4 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring FGF/FGFR abberations: a phase I dose-expansion study. Cancer Discov 2022;12:402–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Le Fèvre C, Constans JM, Chambrelant I, Antoni D, Bund C, Leroy-Freschini B, et al. Pseudoprogression versus true progression in glioblastoma patients: a multiapproach literature review. Part 2—Radiological features and metric markers. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021;159:103230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224ra24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Y, Springer S, Zhang M, McMahon KW, Kinde I, Dobbyn L, et al. Detection of tumor-derived DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with primary tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Proc National Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:9704–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Mattos-Arruda L, Mayor R, Ng CKY, Weigelt B, Martínez-Ricarte F, Torrejon D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat Commun 2015;6:8839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pentsova EI, Shah RH, Tang J, Boire A, You D, Briggs S, et al. Evaluating cancer of the central nervous system through next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2404–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller AM, Shah RH, Pentsova EI, Pourmaleki M, Briggs S, Distefano N, et al. Tracking tumour evolution in glioma through liquid biopsies of cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 2019;565:654–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mouliere F, Mair R, Chandrananda D, Marass F, Smith CG, Su J, et al. Detection of cell-free DNA fragmentation and copy number alterations in cerebrospinal fluid from glioma patients. EMBO Mol Med 2018;10:e9323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Juratli TA, Stasik S, Zolal A, Schuster C, Richter S, Daubner D, et al. Promoter mutation detection in cell-free tumor-derived DNA in patients with IDH wild-type glioblastomas: a pilot prospective study. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:5282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang TY, Piunti A, Lulla RR, Qi J, Horbinski CM, Tomita T, et al. Detection of histone H3 mutations in cerebrospinal fluid-derived tumor DNA from children with diffuse midline glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2017;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martínez-Ricarte F, Mayor R, Martínez-Sáez E, Rubio-Pérez C, Pineda E, Cordero E, et al. Molecular diagnosis of diffuse gliomas through sequencing of cell-free circulating tumor DNA from cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2812–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Escudero L, Llort A, Arias A, Diaz-Navarro A, Martínez-Ricarte F, Rubio-Perez C, et al. Circulating tumour DNA from the cerebrospinal fluid allows the characterisation and monitoring of medulloblastoma. Nat Commun 2020;11:5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steinhaus R, Proft S, Schuelke M, Cooper DN, Schwarz JM, Seelow D. MutationTaster2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:W446–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Andrade KC, Lee EE, Tookmanian EM, Kesserwan CA, Manfredi JJ, Hatton JN, et al. The TP53 database: transition from the International Agency for Research on Cancer to the US National Cancer Institute. Cell Death Differ 2022;29:1071–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corless BC, Chang GA, Cooper S, Syeda MM, Shao Y, Osman I, et al. Development of novel mutation-specific droplet digital PCR assays detecting TERT promoter mutations in tumor and plasma samples. J Mol Diagn 2019;21:274–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology 2003;227:309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lombardi G, Barresi V, Indraccolo S, Simbolo M, Fassan M, Mandruzzato S, et al. Pembrolizumab activity in recurrent high-grade gliomas with partial or complete loss of mismatch repair protein expression: a monocentric, observational and prospective pilot study. Cancers 2020;12:2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corti G, Bartolini A, Crisafulli G, Novara L, Rospo G, Montone M, et al. A genomic analysis workflow for colorectal cancer precision oncology. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2019;18:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crisafulli G, Mussolin B, Cassingena A, Montone M, Bartolini A, Barault L, et al. Whole exome sequencing analysis of urine trans-renal tumour DNA in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. ESMO Open 2019;4:e000572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Crisafulli G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Lazzari L, Pietrantonio F, Amatu A, Macagno M, et al. Temozolomide treatment alters mismatch repair and boosts mutational burden in tumor and blood of colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Discov 2022;12:1656–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, Kundra R, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;2017:PO.17.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li M, Chen WD, Papadopoulos N, Goodman SN, Bjerregaard NC, Laurberg S, et al. Sensitive digital quantification of DNA methylation in clinical samples. Nat Biotechnol 2009;27:858–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J, Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:223–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sottoriva A, Spiteri I, Piccirillo SG, Touloumis A, Collins VP, Marioni JC, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc National Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:4009–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim J, Lee IH, Cho HJ, Park CK, Jung YS, Kim Y, et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of the primary glioblastoma genome. Cancer Cell 2015;28:318–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barthel FP, Wei W, Tang M, Martinez-Ledesma E, Hu X, Amin SB, et al. Systematic analysis of telomere length and somatic alterations in 31 cancer types. Nat Genet 2017;49:349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reifenberger G, Wirsching HG, Knobbe-Thomsen CB, Weller M. Advances in the molecular genetics of gliomas—implications for classification and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:434–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lapin M, Huang HJ, Chagani S, Javle M, Shroff RT, Pant S, et al. Monitoring of dynamic changes and clonal evolution in circulating tumor DNA from patients with IDH-mutated cholangiocarcinoma treated with isocitrate dehydrogenase inhibitors. JCO Precis Oncol 2022;6:e2100197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Tables S1-S13, Description of Supplementary Data 1-3, Supplementary Materials and Methods, Supplementary References.

Primers and probes.

NGS analysis - Complete dataset.

SNP ID.

Data Availability Statement

Complete datasets related to NGS analysis (referring to Figs. 2I and 3G; Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Tables S5 and S10) are available as Supplementary Data S2 (sheets 1–3). Raw NGS data are available at the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession number PRJEB55332, study ERP140225 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/search). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, Supplementary Information, and Supplementary Data S1 and S3. Other related data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Figure 2.

Cohort 1: Comparative analysis of peritumoral CSF and tumor tissues. A, Analysis of DNA amount versus CSF volume in peritumoral CSF samples from Cohort 1 (n = 45). Red line indicates the threshold of minimal DNA content (10 ng) for NGS analysis (Spearman correlation between total CSF DNA amount and volume, r = 0.36, P = 0.014). B, Analysis of cfDNA concentration in peritumoral CSF samples from Cohort 1 (n = 45). Gray line, median DNA concentration = 77.2 ng/mL. C, Correlation between peritumoral CSF cfDNA concentration and tumor features such as proximity to a CSF space (ventricle or cistern), tumor grade, and size. Median cfDNA concentrations were compared between groups defined by proximity to CSF space or tumor grades (non parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test). Maximal tumor diameter and areas (as reported in Supplementary Table S1) were correlated with cfDNA concentration in all CSF samples (Pearson correlation). n, number of tumors. D, cfDNA analysis showing the presence of either low (L) or high (H) or mixed (MIX) molecular weight (MW) DNA in representative CSF samples (Bioanalyzer output). E and F, Heatmaps showing peritumoral CSF samples eligible to ddPCR (n = 36) analyzed for selected genetic alterations found in the corresponding tumors. E, copy-number variations (CNV). Red, amplifications (CN > 5) and gains (3 < CN < 5); blue, deletions (CN < 1.5). Color legend for CNV is shown. F, Gene mutations. Color legend for VAF (variant allele frequency) is shown. VAF < 10% are reported. *, Samples tested for both CNV and mutations. G, Dot plot indicating cfDNA concentration and MW features in the groups of peritumoral CSF samples where tumor genetic alterations were detected (yes) or not (no) by ddPCR. No statistically significant association was found between DNA MW type and the possibility to detect mutations in CSF (χ2 test for a Ptrend = 0.39, df = 1). H, Flow-chart: Shortlisting of peritumoral CSF samples from sample collection to eligibility to NGS analysis. I, Comparative NGS analysis showing correspondence between matched peritumoral CSF cfDNAs and tumor tissue DNAs. CSF cfDNA total amount, concentration and quality (MW), and VAF < 10% are reported. Color legends for heatmaps (CN and VAF) are shown.

Figure 3.