Abstract

Background

The clinical impact of phenotyping empyema is poorly described. This study was designed to evaluate clinical characteristics and outcomes based on the two readily available parameters, pleural fluid culture status and macroscopic fluid appearance.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on patients with empyema hospitalised between 2013 and 2020. Empyema was classified into culture-positive empyema (CPE) or culture-negative empyema (CNE) and pus-appearing empyema (PAE) or non-pus-appearing empyema (non-PAE) based on the pleural fluid culture status and macroscopic fluid appearance, respectively.

Results

Altogether, 212 patients had confirmed empyema (CPE: n=188, CNE: n=24; PAE: n=118, non-PAE: n=94). The cohort was predominantly male (n=163, 76.9%) with a mean age of 65.0±13.6 years. Most patients (n=180, 84.9%) had at least one comorbidity. Patients with CPE had higher rates of in-hospital mortality (19.1% versus 0.0%, p=0.017) and 90-day mortality (18.6% versus 0.0%, p=0.017) and more extrapulmonary sources of infection (29.8% versus 8.3%, p=0.026) when compared with patients with CNE. No significant difference in mortality rate was found between PAE and non-PAE during the in-hospital stay and at 30 days and 90 days. Patients with PAE had less extrapulmonary sources of infection (20.3% versus 36.2%, p=0.010) and more anaerobic infection (40.9% versus 24.5%, p=0.017) than those with non-PAE. The median RAPID (renal, age, purulence, infection source, and dietary factors) scores were higher in the CPE and non-PAE groups. After adjusting for covariates, culture positivity was not independently associated with mortality on multivariable analysis.

Conclusion

Empyema is a heterogeneous disease with different clinical characteristics. Phenotyping empyema into different subclasses based on pleural fluid microbiological results and macroscopic fluid appearance provides insight into the underlying bacteriology, source of infection and subsequent clinical outcomes.

Short abstract

Empyema can be phenotyped by pleural fluid culture status (positive or negative) and gross appearance (pus- or non-pus-appearing). These subgroups have different clinical outcomes. Empyema with positive culture has higher in-hospital and 3-month mortality. https://bit.ly/3X76Kx2

Background

Parapneumonic effusion is common among patients with pneumonia attending the emergency department [1], and it may progress into empyema if not promptly treated, leading to high morbidity and mortality rates [2–4]. Although empyema has been considered a single disease entity, its phenotyping and associated clinical impact are poorly described. The possible phenotypes of empyema may be stratified by its diagnostic criteria, the presence of microorganisms in the pleural fluid [5, 6] or a frank pus appearance. Previous studies on the microbiological pattern of empyema mainly focused on the bacteriology, source of infection and clinical outcomes in those with positive pleural fluid microbiological results (i.e. Gram stain or culture) [7, 8], and thus ignored the contribution from those with negative pleural fluid culture. In addition, the relationship between pleural fluid purulence and clinical outcomes, especially mortality, has not been consistently established [7, 9]. Based on these observations, we hypothesised that clinical outcomes would differ in different empyema phenotypes (culture-positive and culture-negative; pus-appearing and non-pus-appearing). The aim of our study was to compare the characteristics and outcomes of empyema based on the pleural fluid culture status and macroscopic fluid appearance.

Methods

This was a single-centre, retrospective study in a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong covering 8 years, from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2020. All admission episodes with a primary hospital discharge diagnosis coded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, with 510.0 or 510.9 (“empyema”, “empyema with fistula”, “empyema without mention of fistula” or “pyothorax without fistula”) were retrieved. Empyema thoracis was defined either by clearly documented pus appearance or microbiological confirmation of microorganisms (positive Gram stain or culture) in the pleural fluid, and clinical features of infection and systemic inflammatory response. The pleural fluid was sent for microbiological testing in sterile plain containers and/or inoculation into culture bottles (BD BACTEC Plus Aerobic/F Culture Vials and BD BACTEC Lytic/10 Anaerobic/F Culture Vials; Becton, Dickinson and Company, North Ryde, Australia). Patients aged ≥18 years were included in this study. Exclusions comprised empyema in body cavities other than the pleural space, complicated parapneumonic effusion not fulfilling the definition of empyema, tuberculous pleuritis, lack of clear documentation on fluid appearance, or pus-like appearance with an alternative explanation, particularly chylothorax and pseudochylothorax [7, 10]. All hospital notes and electronic records of these admission episodes were reviewed manually. The long-term outcomes of patients, including mortality, complications and readmissions after index hospitalisation, were retrieved from the territory-wide healthcare database.

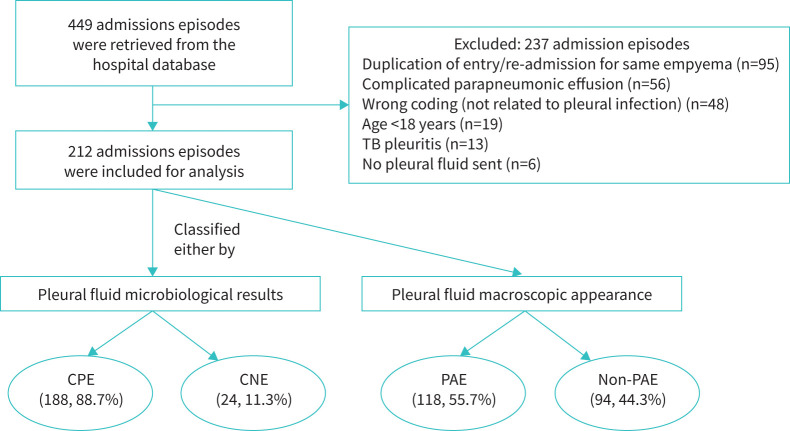

Based on the pleural fluid microbiological results and macroscopic appearance, empyema was classified into two categories and then dichotomously into two subgroups within each category: culture-positive empyema (CPE) or culture-negative empyema (CNE); and pus-appearing empyema (PAE) and non-pus-appearing empyema (non-PAE) (figure 1). These were defined as follows:

CPE: a positive microbiological test (Gram stain or culture of microorganisms) in the pleural fluid, regardless of the pleural fluid macroscopic appearance.

CNE: a negative microbiological test in the pleural fluid, but with a macroscopic pus appearance.

PAE: a macroscopic pus appearance of pleural fluid regardless of the microbiological results.

Non-PAE: an absence of macroscopic pus appearance (i.e. clear, turbid, purulent) of pleural fluid but positive microbiological results (empyema with clear or purulent appearance, but not up to the extent of pus, were also included).

FIGURE 1.

Classification of empyema and number of patients based on pleural fluid microbiological results and macroscopic appearance. This figure shows the distribution of empyema cases based on two clinical characteristics: pleural fluid microbiological results and macroscopic appearance. They can be grouped as culture-positive empyema (CPE) or culture-negative empyema (CNE) based on the microbiological results, and as pus-appearing empyema (PAE) or non-pus-appearing empyema (non-PAE) based on the macroscopic appearance. Cases with negative pleural fluid microbiological results and non-pus appearance were excluded from the analysis. TB: tuberculosis.

Various domains of clinical data were recorded, including pleural fluid macroscopic appearance, microbiological results and clinical outcomes. The source of empyema was classified into pulmonary and extrapulmonary origin, and community- and hospital-acquired as previously described [7, 10, 11]. Further details are provided in the supplementary file.

The primary outcomes of the study were the differences in in-hospital mortality between the CPE and CNE groups, and between the PAE and non-PAE groups. Secondary outcomes included the differences in 30-day and 90-day mortality rates, clinical characteristics, pleural fluid results and source of infection between the CPE and CNE groups and the PAE and non-PAE groups; bacteriology in the CPE groups and the difference in bacteriology between the PAE and non-PAE groups; and the reasons for negative pleural fluid culture.

The demographic and clinical characteristics are presented with descriptive statistics, as mean±sd, median (interquartile range (IQR)) and n (%), as appropriate. Comparison between empyema groups was performed by independent t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Multivariable analysis with the Cox regression backward selection model was used to identify the independent predictors of mortality. All tests were two-tailed, and the significance was set at p<0.05. Data were analysed using the Statistical Package of the Social Science Statistical Software for Window, Version 26 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC reference: 2018.194). Patient consent was not required owing to the retrospective nature.

Results

Among 449 admission episodes retrieved from the hospital database, 237 episodes were excluded and 212 episodes of empyema remained for subsequent analysis (figure 1). According to the microbiological results, 188 episodes (88.7%) were classified as CPE and 24 episodes (11.3%) as CNE. According to the macroscopic pleural fluid appearance, 118 episodes (55.7%) were classified as PAE and 94 episodes (44.3%) as non-PAE.

Baseline demographics, comorbidities and medication use are shown in table 1 and supplementary table S1. The cohort was predominantly male (76.9%) with a mean age of 65.0±13.6 years. Most patients (n=180, 84.9%) had at least one comorbidity and 23.1% of them had active malignancy. The use of immunosuppressive agents (4.2%) or inhaled corticosteroids (4.7%) before the empyema episode was uncommon.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and comorbidities of the whole cohort and different empyema subgroups

| Patients | Whole cohort | CPE | CNE |

p-value

(CPE versus CNE) |

PAE | Non-PAE |

p-value

(PAE versus non-PAE) |

| Total | 212 (100.0) | 188 (88.7) | 24 (11.3) | NA | 118 (55.7) | 94 (44.3) | NA |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, years (mean±sd) | 65.0±13.6 | 65.1±13.7 | 64.3±14.3 | 0.801ƒ | 63.9±14.2 | 66.3±13.2 | 0.212## |

| Male | 163 (76.9) | 144 (76.7) | 19 (79.2) | 0.778 | 92 (78.0) | 71 (75.5) | 0.676 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| At least one comorbidity | 180 (84.9) | 160 (85.1) | 20 (83.3) | 0.766 | 100 (84.7) | 80 (85.1) | 0.942 |

| Metabolic risk factors# | 118 (55.7) | 103 (54.8) | 15 (62.5) | 0.474 | 66 (55.9) | 52 (55.3) | 0.929 |

| Cardiac comorbidities¶ | 37 (17.5) | 35 (18.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0.266 | 18 (15.3) | 19 (20.2) | 0.345 |

| Neurological comorbidities+ | 35 (16.5) | 33 (17.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0.382 | 22 (18.6) | 13 (13.8) | 0.348 |

| Respiratory comorbidities§ | 29 (13.7) | 28 (14.9) | 1 (4.2) | 0.212 | 14 (11.9) | 15 (16.0) | 0.389 |

| Active malignancy | 49 (23.1) | 46 (24.5) | 3 (12.5) | 0.190 | 25 (21.2) | 24 (25.5) | 0.456 |

Data presented as n (%), unless otherwise indicated. CPE: culture-positive empyema; CNE: culture-negative empyema; PAE: pus-appearing empyema; NA: not applicable. #: includes hypertension, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia; ¶: includes ischaemic heart disease, cardiac arrhythmia and congestive heart failure; +: includes cerebrovascular accident, dementia and parkinsonism; §: includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, asthma and interstitial lung disease; ƒ: difference 0.8 (95% CI −5.1–6.7); ##: difference −2.4 (95% CI −6.1–1.4).

The presenting symptoms, baseline investigations and pleural fluid analysis are listed in tables 2 and 3 and supplementary table S2. Shortness of breath, fever, productive cough, chest pain or pleurisy were common at presentation. Inflammatory markers, including white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in the blood, and WBC count and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the pleural fluid were elevated, while the pH and glucose levels in the pleural fluid were depressed. Thoracic ultrasound (TUS) examination was performed before the pleural intervention in 182 episodes (85.5%). Among the 107 patients who had ultrasonographic features reported, septation in the pleural space was common (93.5%). Other than macroscopic pus appearance (n=118, 55.7%), 65 episodes (30.7%) were documented to have a purulent appearance but not to the extent of frank pus, while 29 episodes (13.7%) were of clear fluid appearance.

TABLE 2.

Presenting symptoms upon admission of the whole cohort and different empyema subgroups

| Presentation symptoms | Whole cohort | CPE | CNE | p-value (CPE versus CNE) | PAE | Non-PAE | p-value (PAE versus non-PAE) |

| Total patients, n | 212 | 188 | 24 | 118 | 94 | ||

| Shortness of breath | 140 (66.0) | 129 (68.6) | 11 (45.8) | 0.026 | 72 (61.0) | 68 (72.3) | 0.084 |

| Fever | 124 (58.5) | 111 (59.0) | 13 (54.2) | 0.648 | 69 (58.5) | 55 (58.5) | 0.996 |

| Cough | 123 (58.0) | 106 (56.4) | 17 (70.8) | 0.177 | 68 (57.6) | 55 (58.5) | 0.897 |

| Sputum | 104 (49.1) | 91 (48.4) | 13 (54.2) | 0.595 | 58 (49.2) | 46 (48.9) | 0.975 |

| Pleurisy | 95 (44.8) | 84 (44.7) | 11 (45.8) | 0.915 | 53 (44.9) | 42 (44.7) | 0.973 |

| Appetite loss | 31 (14.6) | 30 (16.0) | 1 (4.2) | 0.215 | 16 (13.6) | 15 (16.0) | 0.623 |

| Weight loss | 30 (14.2) | 27 (14.4) | 3 (12.5) | 1.000 | 17 (14.4) | 13 (13.8) | 0.905 |

| Haemoptysis | 15 (7.1) | 13 (6.9) | 2 (8.3) | 0.681 | 12 (10.2) | 3 (3.2) | 0.049 |

| Confusion | 5 (2.4) | 3 (1.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0.099 | 4 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0.385 |

Data presented as n (%), unless otherwise indicated. CPE: culture-positive empyema; CNE: culture-negative empyema; PAE: pus-appearing empyema.

TABLE 3.

Blood, ultrasonographic and pleural fluid non-microbiological results during the presentation of the whole cohort and different empyema subgroups

| Whole cohort | CPE | CNE | p-value (CPE versus CNE) | PAE | Non-PAE | p-value (PAE versus non-PAE) | |

| Patients, n | 212 | 188 | 24 | 118 | 94 | ||

| Blood results | |||||||

| WBC, ×109 per L | 14.9 (10.5–20.3) | 15.0 (10.5–20.2) | 13.7 (10.4–22.1) | 0.914 | 14.8 (10.1–20.5) | 15.3 (11.1–19.6) | 0.763 |

| CRP, mg·L−1 | 208.1 (124.5–304.8) | 213.9 (124.4–309.5) | 174.1 (124.8–234.8) | 0.173 | 204.0 (114.3–295.5) | 208.9 (133.0–306.7) | 0.591 |

| Urea, mmol·L−1 | 5.8 (4.0–9.2) | 6.0 (4.4–9.6) | 4.6 (3.3–6.6) | 0.019 | 5.2 (3.8–8.7) | 6.5 (4.6–10.7) | 0.015 |

| Albumin, g·L−1 | 24.5 (19.8–29.0) | 24.0 (19.0–29.0) | 26.5 (23.0–30.3) | 0.131 | 24.5 (19.3–29.0) | 24.5 (20.0–30.0) | 0.750 |

| Right-sided empyema | 119 (56.1) | 105 (55.9) | 14 (58.3) | 0.919 | 68 (57.6) | 51 (54.3) | 0.490 |

| Septation in pleural space on TUS, n/N (%)# | 100/107 (93.5) | 88/94 (93.6) | 12/13 (92.3) | 1.000 | 57/63 (90.5) | 43/44 (97.7) | 0.236 |

| Macroscopic fluid appearance | |||||||

| Pus | 118 (55.7) | 94 (50.0) | 24 (100.0) | <0.001 | 118 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Turbid (but not pus-appearing) | 65 (30.7) | 65 (34.6) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) | 65 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Clear | 29 (13.7) | 29 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.052 | 0 (0.0) | 29 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Pleural fluid results¶ | |||||||

| Fluid WBC, cells·mL−1 | 37 820.5 (10 875.0–129 600.0) | 34 560.0 (9250.0–111 200.0) | 109 900.0 (74 750.0–235 425.0) | 0.007 | 91 400.0 (25 640.0–199 200.0) | 19 900.0 (3662.5–49 067.5) | <0.001 |

| n/N | 151/212 | 133/188 | 18/24 | 81/118 | 70/94 | ||

| Fluid TP, g·L−1 | 40.0 (25.3–47.8) | 40.0 (25.0–48.0) | 38.0 (29.0–46.5) | 0.984 | 36.0 (21.0–46.8) | 43.0 (35.5–53.0) | 0.001 |

| n/N | 170/212 | 151/188 | 19/24 | 90/118 | 80/94 | ||

| Fluid LDH, U·L−1 | 5360.0 (1250.5–12 837.5) | 5091.0 (1147.5–12 082.0) | 14 618.0 (4633.3–23 265.8) | 0.003 | 9422.0 (2868.5–18 239.5) | 2537.0 (607.5–6898.8) | <0.001 |

| n/N | 171/212 | 151/188 | 20/24 | 91/118 | 80/94 | ||

| Fluid glucose, mmol·L−1+ | 0.3 (0.2–2.2) | 0.2 (0.2–2.2) | 0.3 (0.2–1.4) | 0.636 | 0.3 (0.2–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–2.4) | 0.464 |

| n/N | 118/212 | 105/188 | 13/24 | 65/118 | 53/94 | ||

| Fluid pH | 6.7 (6.5–7.1) | 6.7 (6.5–7.1) | 6.7 (6.5–6.9) | 0.900 | 6.7 (6.5–6.9) | 6.8 (6.5–7.1) | 0.073 |

| n/N | 118/212 | 103/188 | 15/24 | 60/118 | 58/94 | ||

| Fluid ADA, U·L−1§ | 89.0 (33.5–183.0) | 87.0 (29.0–165.0) | 183.0 (70.0–200.0) | 0.031 | 162.0 (69.0–200.0) | 46.0 (20.0–97.0) | <0.001 |

| n/N | 122/212 | 109/188 | 13/24 | 61/118 | 61/94 |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. CPE: culture-positive empyema; CNE: culture-negative empyema; PAE: pus-appearing empyema; WBC: white blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; TUS: thoracic ultrasound; TP: total protein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; ADA: adenosine deaminase. #: out of the 107 patients who had ultrasonographic nature of pleural fluid reported; ¶: some pleural fluid parameters were not available because the fluid was unfit for haematological and biochemical analysis due to the viscous nature or not investigated, so the number of empyema with available information is quoted below the data; +: the lowermost limit for pleural fluid glucose analysis is 0.2 mmol·L−1; §: the uppermost limit for pleural fluid ADA analysis is 200 U·L−1.

The bacteriology of pleural fluid is shown in tables 4 and 5. Among those with positive microbiological identification from pleural fluid and tissue, a total number of 277 microbiological isolates were recovered. Aerobic Gram-positive bacteria (n=144, 52.0%) was the most common group of bacteria cultured, followed by anaerobes (n=73, 26.4%), aerobic Gram-negative bacteria (n=53, 19.1%) and fungi (n=7, 2.5%). Polymicrobial isolates were recovered from 62 empyema episodes (29.2%), and anaerobes were involved in more than half of them (n=38, 61.3% of polymicrobial empyema isolates). Recent pleural intervention, prolonged placement of a foreign body into the pleural space (chest drain or indwelling pleural catheter) or drain wound infection contributed to more than half of the extrapulmonary sources (supplementary table S3). Despite negative pleural fluid cultures in the CNE group, some of the patients had positive microbiological workup from other respiratory and non-respiratory specimens (supplementary table S4).

TABLE 4.

Classification of empyema based on the number of bacterial isolates and results of Gram stain or presence of anaerobes

| Number of bacterial isolates | ||||

| Empyema category | Whole cohort | PAE | Non-PAE | p-value |

| Total number | 212 (100.0) | 118 (100.0) | 94 (100.0) | |

| Culture-positive empyema# | 188 (88.7) | 94 (79.7) | 94 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Single isolates | 126 (59.4) | 63 (67.0) | 63 (67.0) | 1.000 |

| Non-anaerobes | 101 (47.6) | 46 (48.9) | 55 (58.5) | 0.188 |

| Anaerobes | 25 (11.8) | 17 (18.1) | 8 (8.5) | 0.053 |

| Multiple isolates | 62 (29.2) | 31 (33.0) | 31 (33.0) | 1.000 |

| Non-anaerobes containing | 24 (11.3) | 8 (8.5) | 16 (17.0) | 0.080 |

| Anaerobes containing | 38 (17.9) | 23 (24.5) | 15 (16.0) | 0.146 |

| Empyema containing Gram-positive bacterial isolates¶ | 129 (68.6) | 62 (66.0) | 67 (71.3) | 0.432 |

| Empyema containing Gram-negative bacterial isolates¶ | 40 (21.3) | 18 (19.1) | 22 (23.4) | 0.476 |

| Empyema containing anaerobic bacterial isolates¶ | 63 (33.5) | 40 (42.6) | 23 (24.5) | 0.009 |

| Empyema containing fungal isolates¶ | 7 (3.7) | 2 (2.1) | 5 (5.3) | 0.444 |

| Culture-negative empyema | 24 (11.3) | 24 (20.3) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

Data presented as n (%). PAE: pus-appearing empyema. #: includes Gram stain and culture results from the pleural fluid and pleural tissue; ¶: as a percentage of culture-positive empyema.

TABLE 5.

Microbiological results of pleural fluid or tissue among total number of microbiological isolates (n=277)

| Aerobic Gram-positive bacteria | 144 (52.0) | Aerobic Gram-negative bacteria | 53 (19.1) | Anaerobes | 73 (26.4) | Fungi | 7 (2.2) |

| Streptococcus species | 86 (31.0) | Klebsiella species | 12 (4.3) | Peptostreptococcus species | 15 (5.4) | Candida albicans | 6 (1.8) |

| Streptococcus viridans (non-milleri group) | 54 (19.5) | Escherichia coli | 8 (2.9) | Fusobacterium species | 11 (4.0) | Aspergillus species | 1 (0.4) |

| Streptococcus milleri | 21 (7.6) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 8 (2.9) | Prevotella species | 10 (3.6) | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 3 (1.1) | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3 (1.1) | Actinomyces species | 7 (2.5) | ||

| Other Streptococcus species | 8 (2.9) | Acinetobacter species | 3 (1.1) | Lactobacillus species | 4 (1.4) | ||

| Staphylococcus species | 30 (10.8) | Haemophilus influenzae | 2 (0.7) | Bacteroides species | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 13 (4.7) | Salmonella enteritidis | 2 (0.7) | Veillonella species | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | 10 (3.6) | Enterobacter species | 2 (0.7) | Porphyromonas gingivalis | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus | 7 (2.5) | Citrobacter species | 2 (0.7) | Atopobium species | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Enterococcus species | 13 (4.7) | Neisseria species | 2 (0.7) | Propionibacterium species | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Enterococcus faecium | 7 (2.5) | Others# | 8 (3.2) | Non-typeable anaerobes | 18 (6.6) | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 5 (1.8) | ||||||

| Other Enterococcus species | 1 (0.4) | ||||||

| Others | 15 (5.4) | ||||||

| Corynebacterium species | 4 (1.4) | ||||||

| Diphtheroids | 2 (0.7) | ||||||

| Bacillus species | 2 (0.7) | ||||||

| Non-typeable (Gram-positive but culture-negative) | 7 (2.5) |

Data presented as n (%). #: includes Serratia species (1), Proteus mirabilis (1), Campylobacter rectus (1), Clostridium perfringens (1), Aeromonas species (1), Myroides species (1), Legionella pneumophila (1) and non-typeable Gram-negative bacilli (2).

The treatment given and outcomes of empyema are shown in tables 6 and 7 and supplementary table S5. The in-hospital, 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were 17.1%, 11.8% and 16.6%, respectively, with causes of mortality at different times listed in supplementary table S6. One patient in the CNE group died by suicide after discharge and was thus excluded from the analysis of mortality. The median RAPID (renal, age, purulence, infection source and dietary factors) score in the cohort was 3 (IQR 2–4). A median of 2 (IQR 1–2) pleural intervention episodes were performed in each empyema episode. Less than half of the patients required intrapleural fibrinolytic and surgical referral for unresolved empyema despite pleural drainages. The median total duration of antibiotic use and hospital stay were 42 and 30 days, respectively. Acute liver and renal impairment were the most common complications.

TABLE 6.

Management of empyema, clinical outcomes and complications of the whole cohort and different empyema subgroups

| Whole cohort | CPE | CNE | p-value (CPE versus CNE) | PAE | Non-PAE | p-value (PAE versus non-PAE) | |

| Patients, n | 212 | 188 | 24 | 118 | 94 | ||

| Management of empyema | |||||||

| Antibiotic concordance | 151 (71.6) | NA | NA | NA | 80 (67.8) | 71 (76.3) | <0.001 |

| Number of therapeutic pleural intervention episodes# | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.519 | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.101 |

| Number of days of pleural intervention after admission (or onset of empyema if hospital-acquired empyema) | 3 (2–6) | 2 (1–6) | 4 (2–7) | 0.037 | 2 (2–5) | 3 (2–7) | 0.240 |

| Use of intrapleural fibrinolytic | 78 (36.8) | 68 (36.2) | 10 (41.7) | 0.599 | 45 (38.1) | 32 (35.1) | 0.650 |

| Need of surgical decortication¶ | 29 (33.3) | 27 (35.1) | 2 (20.0) | 0.485 | 15 (29.4) | 14 (38.9) | 0.356 |

| ICU admission | 30 (14.2) | 28 (14.9) | 2 (8.3) | 0.541 | 17 (14.4) | 13 (13.8) | 0.905 |

| Inotrope use | 29 (13.7) | 26 (13.8) | 3 (12.5) | 1.000 | 20 (16.9) | 9 (9.6) | 0.121 |

| Source of infection | |||||||

| Hospital-acquired | 62 (29.2) | 57 (30.3) | 5 (20.8) | 0.336 | 30 (25.4) | 32 (34.0) | 0.171 |

| Extrapulmonary | 58 (27.4) | 56 (29.8) | 2 (8.3) | 0.026 | 24 (20.3) | 34 (36.2) | 0.010 |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. CPE: culture-positive empyema; CNE: culture-negative empyema; PAE: pus-appearing empyema; ICU: intensive care unit; NA: not applicable. #: diagnostic thoracentesis and surgical decortication were not included in the number of therapeutic pleural interventions; ¶: out of the 87 patients who were referred for surgery.

TABLE 7.

The mortality rates and the RAPID score of the whole cohort and different empyema subgroups

| Whole cohort | CPE | CNE | p-value (CPE versus CNE) | PAE | Non-PAE | p-value (PAE versus non-PAE) | |

| Patients, n | 212 | 188 | 24 | 118 | 94 | ||

| Mortality rate# | |||||||

| In-hospital | 36 (17.1) | 36 (19.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.017 | 17 (14.5) | 19 (20.2) | 0.275 |

| 30-day | 25 (11.8) | 25 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.084 | 12 (10.3) | 13 (13.8) | 0.425 |

| 90-day | 35 (16.6) | 35 (18.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.017 | 16 (13.7) | 19 (20.2) | 0.204 |

| RAPID score¶ | |||||||

| Median RAPID score (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (2–3) | 0.020 | 3 (2–4) | 4 (2–4) | <0.001 |

| RAPID category | 0.051 | 0.012 | |||||

| Low risk (score 0–2) | 71 (33.5) | 58 (30.9) | 13 (54.2) | 49 (41.5) | 22 (23.4) | ||

| Medium risk (score 3–4) | 96 (45.3) | 87 (46.3) | 9 (37.5) | 50 (42.4) | 46 (48.9) | ||

| High risk (score 5–7) | 45 (21.2) | 43 (22.9) | 2 (8.3) | 19 (16.1) | 26 (27.7) |

Data presented as n (%), unless otherwise indicated. RAPID score: renal, age, purulence, infection source and dietary factors score; CPE: culture-positive empyema; CNE: culture-negative empyema; PAE: pus-appearing empyema; IQR: interquartile range. #: a patient who died by suicide was excluded from the analysis for mortality; ¶: renal (R) score based on serum urea level (0 if <5 mmol·L−1, 1 if 5–8 mmol·L−1, 2 if >8 mmol·L−1); age (A) score based on age (0 if <50 years, 1 if 50–70 years, 2 if >70 years); purulence (P) score based on fluid purulence (0 if purulent, 1 if not purulent or clear); infection (I) score based on infection source (0 if community-acquired, 1 if hospital-acquired); dietary (D) score based on serum albumin level (0 if ≥27 g·L−1, 1 if <27 g·L−1).

Comparison between CPE and CNE

There was no significant difference in the mean age between the CPE and CNE groups (mean difference 0.8, 95% CI −5.1–6.7 years). The CPE group had a higher prevalence of empyema history; was more likely to present with shortness of breath; and had lower pleural fluid WBC, LDH and adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels, earlier pleural intervention after disease onset and a longer acute hospital stay. Otherwise, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, presenting symptoms, TUS findings, treatment received or need for organ support between the two groups (tables 1–3 and 6 and supplementary tables S1, S2 and S5). All mortality happened in the CPE group, and a positive pleural fluid culture was associated with higher in-hospital mortality rates (CPE: 19.1%, CNE: 0.0%, p=0.017) and 90-day mortality rates (CPE: 18.6%, CNE: 0.0%, p=0.017) (table 7 and supplementary figure S1). The difference in mortality remained significant even if the non-PAE episodes in the CPE group were excluded (supplementary table S7). The median RAPID score was higher in the CPE group. However, after adjusting for covariates, culture positivity was not independently associated with mortality on multivariable analysis (supplementary table S8). The source of infection was more likely extrapulmonary in the CPE group (29.8% versus 8.3%, p=0.026).

Comparison between PAE and non-PAE

There was no significant difference in the mean age between the PAE and non-PAE groups (mean difference −2.4, 95% CI −6.1–1.4 years). When compared with the non-PAE group, the PAE group was more likely to present with haemoptysis and have significantly lower plasma urea and creatinine levels and higher pleural fluid WBC, LDH and ADA levels. They were also more likely to receive a larger size of initial chest drain. Otherwise, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, presenting symptoms, TUS findings, treatment received, need for organ support and length of hospital stay between the PAE and non-PAE groups (tables 1–3 and 6 and supplementary tables S1, S2 and S5). No significant difference in mortality rate was found between the two groups at different time points, although the median RAPID score was higher in the non-PAE group (table 7 and supplementary figure S2). The non-PAE group had more extrapulmonary sources (PAE: 20.3% versus non-PAE: 36.2%, p=0.010) and a disease course more likely to be complicated by hospital-acquired pneumonia (PAE: 2.5% versus non-PAE: 11.7%, p=0.010) and decompensated heart failure (PAE: 0.0% versus non-PAE: 4.3%, p=0.037). More anaerobes were recovered from the PAE group (table 4).

Factors affecting the microbiological yield

No factors were found to affect the pleural fluid culture yield between the CPE and CNE groups (supplementary table S9). Culture bottles of 21 pleural fluid specimens (9.9%) were also sent, which retrieved two additional anaerobes (Fusobacterium species and Actinomyces israelii) and appropriate typing of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus as Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Pleural biopsies were performed in 35 patients (16.5%), and seven out of 10 sent for bacterial culture were positive.

Discussion

The current retrospective study focused on differential clinical outcomes based on empyema phenotypes. CPE was associated with higher in-hospital and 90-day mortality rates and was more likely to originate from extrapulmonary sources than CNE, while PAE was associated with more anaerobic involvement and pulmonary infection sources than non-PAE, but with no difference in mortality.

The bacteriology of the current cohort followed the geographically based microbiological pattern of pleural infection, with a predominance of aerobic Gram-positive bacteria, especially Streptococcus viridans or Streptococcus milleri [2, 4, 12]. Also, polymicrobial infection was common in the cohort, with significantly more anaerobic involvement in CPE [13]. However, the microbiological analysis of empyema would not be complete if CNE were excluded. The entity of CNE is clinically significant because the culprit organisms remain unidentified, and antimicrobial treatment is entirely empirical. However, epidemiological and clinical research focusing on the outcomes of CNE is surprisingly limited. We suspect that identifying CNE in clinical databases could be difficult because this diagnosis relies purely on the macroscopic fluid appearance while excluding complicated parapneumonic effusion. Thus, most prior studies narrowed the disease spectrum to CPE only or extended it to cover the large bulk of pleural infections including complicated parapneumonic effusion [9, 14–16]. In the cohort reported by Chen et al. [12], the incidence of CNE was 18.7% (32 of 171 patients), while the possible incidence of CNE may lie between 20.5% and 90.0% in other cohorts with pleural infection [2, 5, 11, 15, 17, 18], subject to the nature of patients included. The mystery of culture negativity was solved by the TORPIDS study, which employed 16S rRNA next-generation sequencing and identified the total microbiome in pleural infection. Pathogens were identified in almost all fluid samples, and 79% were predominately polymicrobial, which matches our findings. Several individual bacterial species were correlated with clinical outcomes, including death [19].

The association between pleural fluid culture status and the distinct bacteriology and source of infection can be clinically valuable by prompting physicians to consider adequate antibiotic coverage against anaerobes, and searching for a septic source outside the lungs in an appropriate clinical context (e.g. absence of pneumonic changes on the thoracic imaging or unusual pathogens cultured from the pleural fluid) [7, 12, 17, 20, 21]. However, because the effect of management strategies based on pleural fluid culture status was not included in the current study, the clinical application of these observations requires prospective validation.

Prognosis and mortality rate were worse in the CPE group, and more aggressive management should be considered. Park et al. [17] reported a similar finding, that pleural infection with positive pleural fluid culture had a significantly higher 30-day mortality rate. However, they included a broad spectrum of pleural infection and early phase of complicated parapneumonic effusion, so simple extrapolation of the impact of culture positivity on mortality should be interpreted cautiously. In the TORPIDS study, the authors did not compare the outcomes between culture-positive and culture-negative groups, and therefore the effect of pleural fluid culture status could not be estimated [19]. Differential clinical behaviours based on culture status have also been observed in other infectious conditions. Negative cultures in sepsis requiring intensive care unit admission [22], in pneumonia [23] and in osteomyelitis [24, 25] have been associated with more favourable clinical outcomes (lower complication or mortality rates), possibly due to a lower bacterial load. Whether there is a link between the degree of pleural inflammation and worse clinical outcomes is an area for further research, though such an association has been reported [26]. Although the effect of culture positivity is minimised after combining it with RAPID score for predicting mortality, the pleural fluid culture status can describe the prognosis of empyema in another direction, because the RAPID score does not include any essential microbiological features of the empyema [7, 10]. By contrast, a relationship between fluid purulence and long-term outcomes could not be established in the current study. Indeed, such a link is poorly established, with divided observations in previous studies [7, 9]. Differences in the definition of pleural infection, the broad spectrum of fluid purulence included and the possibility of inter-observer variation may account for the heterogeneity in prognosis [7, 9] and limited data on the incidence [17].

The prognostic implication for empyema is more complicated than previously believed owing to its heterogeneous disease nature. During the dynamic process from the onset of parapneumonic effusion to empyema, the interplay between bacterial invasion and the immunological response can alter the pleural fluid's culture status and extent of fluid purulence. In addition, culture sensitivity also depends on the timing of pleural fluid sampling, type of culture medium used, prior use of antibiotics, bacterial load and the host immune response [27]. Therefore, the artificial classification of different stages of pleural infection or parapneumonic effusion cannot fully reflect the nature of the infection, though it traditionally guides the treatment and prognosticates the outcome in a broader term. We believe that a single diagnosis entity of empyema is probably oversimplified. As shown in the current study, differential outcomes can be stratified simply based on a pragmatic classification into several distinct clinical groups. The differences in prognosis, source of infection and anaerobic bacterial infection all underpin the need for a better understanding of empyema phenotype and consideration of a personalised treatment plan instead of a one-size-fits-all management strategy. In the era of precision medicine [28], the concept of “disease phenotyping” has been applied to different diseases, e.g. phenotyping malignant pleural effusion to guide management [29], immune phenotyping in sepsis and severe pneumonia [30], choosing the types of biologicals in asthma [31] and treatment of heart failure based on preserved or reduced ejection fraction [32]. Future studies should focus on further phenotyping the disease to understand the diverse presentation of empyema, predict the treatment response and identify a high-risk patient group.

This study has several limitations. First, fluid appearance can be variable, ranging from clear, turbid, purulent to pus, subject to personal perception. Among these, an observation of a grossly pus appearance should be less controversial. Therefore, a dichotomous classification into pus-appearing and non-pus-appearing empyema was used here to minimise recall bias. Second, searching empyema patients through the ICD diagnostic codes may introduce selection bias and the retrospective nature has its intrinsic disadvantage of missing essential clinical information (e.g. TUS findings). However, all available electronic and hardcopy clinical records were manually reviewed to ensure data accuracy. Third, there was a possibility of false-negative pleural fluid culture results owing to the low employment rate of dedicated culture medium [33]. A higher yield of pleural fluid culture positivity may be achieved by bacterial culture using pleural tissue [34] or by applying DNA sequencing to the pleural fluid specimens [35].

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated the heterogeneous behaviour of empyema based on the pleural fluid culture status and gross appearance. CPE was associated with significantly higher in-hospital and 90-day mortality rates and more likely originated from extrapulmonary sources than CNE, while PAE was associated with more anaerobic involvement and pulmonary sources of infection than non-PAE. The study results also challenge the traditional oversimplified classification of empyema and inspire future research. Further prospective studies of pleural infection should consider including the subgroup of CNE as part of the bacteriology and incorporate empyema phenotypes to test their clinical utility in different management strategies.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00534-2022.SUPPLEMENT (678.3KB, pdf)

Acknowledgement

We thank Jack Kit-chung Ng (Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong) and Tat-on Chan (The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong) for advising on statistical analysis. Part of the study results were presented as an oral presentation at the 25th Congress of the Asian Pacific Society of Respirology in 2021.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Data availability: All data relevant to the study are included in the article. All data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC ref.: 2018.194).

Author contributions: K.P. Chan is the guarantor of the study, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. S.S.S. Ng, K.C. Ling, K.C. Ng, L.P. Lo, W.H. Yip, J.C.L. Ngai, K.W. To, F.W.S. Ko, Y.C.G. Lee and D.S.C. Hui contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dean NC, Griffith PP, Sorensen JS, et al. Pleural effusions at first ED encounter predict worse clinical outcomes in patients with pneumonia. Chest 2016; 149: 1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsang KY, Leung WS, Chan VL, et al. Complicated parapneumonic effusion and empyema thoracis: microbiology and predictors of adverse outcomes. Hong Kong Med J 2007; 13: 178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson AD, Prescott RJ, Selkon JB, et al. The clinical course and management of thoracic empyema. QJM 1996; 89: 285–289. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.4.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedawi EO, Hassan M, Rahman NM. Recent developments in the management of pleural infection: a comprehensive review. Clin Respir J 2018; 12: 2309–2320. doi: 10.1111/crj.12941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman NM, Maskell NA, West A, et al. Intrapleural use of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 518–526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maskell NA, Davies CW, Nunn AJ, et al. U.K. controlled trial of intrapleural streptokinase for pleural infection. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 865–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman NM, Kahan BC, Miller RF, et al. A clinical score (RAPID) to identify those at risk for poor outcome at presentation in patients with pleural infection. Chest 2014; 145: 848–855. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cargill TN, Hassan M, Corcoran JP, et al. A systematic review of comorbidities and outcomes of adult patients with pleural infection. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900541. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00541-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies CW, Kearney SE, Gleeson FV, et al. Predictors of outcome and long-term survival in patients with pleural infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160: 1682–1687. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9903002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamazaki A, Ito A, Ishida T, et al. Polymicrobial etiology as a prognostic factor for empyema in addition to the renal, age, purulence, infection source, and dietary factors score. Respir Investig 2019; 57: 574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks DJ, Fisk MD, Koo CY, et al. Thoracic empyema: a 12-year study from a UK tertiary cardiothoracic referral centre. PLoS One 2012; 7: e30074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KY, Hsueh PR, Liaw YS, et al. A 10-year experience with bacteriology of acute thoracic empyema: emphasis on Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients with diabetes mellitus. Chest 2000; 117: 1685–1689. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyanova L, Djambazov V, Gergova G, et al. Anaerobic microbiology in 198 cases of pleural empyema: a Bulgarian study. Anaerobe 2004; 10: 261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brims F, Popowicz N, Rosenstengel A, et al. Bacteriology and clinical outcomes of patients with culture-positive pleural infection in Western Australia: a 6-year analysis. Respirology 2019; 24: 171–178. doi: 10.1111/resp.13395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan M, Cargill T, Harriss E, et al. The microbiology of pleural infection in adults: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900542. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00542-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asai N, Suematsu H, Hagihara M, et al. The etiology and bacteriology of healthcare-associated empyema are quite different from those of community-acquired empyema. J Infect Chemother 2017; 23: 661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park CK, Oh HJ, Choi HY, et al. Microbiological characteristics and predictive factors for mortality in pleural infection: a single-center cohort study in Korea. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0161280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maskell NA, Batt S, Hedley EL, et al. The bacteriology of pleural infection by genetic and standard methods and its mortality significance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 817–823. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-074OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanellakis NI, Wrightson JM, Gerry S, et al. The bacteriology of pleural infection (TORPIDS): an exploratory metagenomics analysis through next generation sequencing. Lancet Microbe 2022; 3: e294–e302. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00327-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corcoran JP, Psallidas I, Gerry S, et al. Prospective validation of the RAPID clinical risk prediction score in adult patients with pleural infection: the PILOT study. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2000130. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00130-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan PSC, Badiei A, Fitzgerald DB, et al. Pleural empyema in a patient with a perinephric abscess and diaphragmatic defect. Respirol Case Rep 2019; 7: e00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phua J, Ngerng W, See K, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of culture-negative versus culture-positive severe sepsis. Crit Care 2013; 17: R202. doi: 10.1186/cc12896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labelle AJ, Arnold H, Reichley RM, et al. A comparison of culture-positive and culture-negative health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest 2010; 137: 1130–1137. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floyed RL, Steele RW. Culture-negative osteomyelitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22: 731–736. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000078901.26909.cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JA, Lin HC, Wei HM, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of culture-negative versus culture-positive osteomyelitis in children treated at a tertiary hospital in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2021; 54: 1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrightson JM, Wray JA, Street TL, et al. S113 Predictors of bacterial ‘load’ in pleural infection. Thorax 2021; 69: A60–A61. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206260.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavez-Galan L, Vesin D, Segueni N, et al. Tumor necrosis factor and its receptors are crucial to control Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin pleural infection in a murine model. Am J Pathol 2016; 186: 2364–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.König IR, Fuchs O, Hansen G, et al. What is precision medicine? Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700391. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00391-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lui MMS, Fitzgerald DB, Lee YCG. Phenotyping malignant pleural effusions. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016; 22: 350–355. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rello J, Perez A. Precision medicine for the treatment of severe pneumonia in intensive care. Expert Rev Respir Med 2016; 10: 297–316. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1144477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGregor MC, Krings JG, Nair Pet al. Role of biologics in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 433–445. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1944CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022. AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022; 79: e263–e421. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menzies SM, Rahman NM, Wrightson JM, et al. Blood culture bottle culture of pleural fluid in pleural infection. Thorax 2011; 66: 658–662. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.157842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Psallidas I, Kanellakis NI, Bhatnagar R, et al. A pilot feasibility study in establishing the role of ultrasound-guided pleural biopsies in pleural infection (The AUDIO Study). Chest 2018; 154: 766–772. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krenke K, Sadowy E, Podsiadły E, et al. Etiology of parapneumonic effusion and pleural empyema in children. The role of conventional and molecular microbiological tests. Respir Med 2016; 116: 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00534-2022.SUPPLEMENT (678.3KB, pdf)