Abstract

Impaired cognition is common in many neuropsychiatric disorders and severely compromises quality of life. Synchronous electrophysiological rhythms represent a core mechanism for sculpting communication dynamics among large-scale brain networks that underpin cognition and its breakdown in neuropsychiatric disorders. Here, we review an emerging neuromodulation technology called transcranial alternating current stimulation that has shown remarkable early results in rapidly improving various domains of human cognition by modulating properties of rhythmic network synchronization. Future noninvasive neuromodulation research holds promise for potentially rescuing network activity patterns and improving cognition, setting groundwork for the development of drug-free, circuit-based therapeutics for people with cognitive brain disorders.

Keywords: transcranial alternating current stimulation, synchronization, cross-frequency coupling, cognition, cognitive deficits, neuropsychiatric disorders

IMPAIRED COGNITION IN NEUROPSYCHIATRY

Cognitive dysfunction is characteristic of numerous neuropsychiatric disorders. Deficits in cognitive domains such as selective attention, working memory, and executive control are symptomatic presentations of various clinical conditions. Attentional impairments are observed in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (1), schizophrenia (2), autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (3), and anxiety and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders (OCD) (4). Altered working memory and executive function manifest as poor planning in ADHD (1), inflexibility in ASD (3), impaired decision making and action initiation in major depressive disorder (MDD) (5), and problems with action inhibition in OCD (4) and bipolar disorder (6). Combinations of these with other deficits are also common, for instance in schizophrenia (2). Given that cognitive impairments contribute to real-world disability and are a core predictor of functional recovery (7), elucidating the mechanisms that give rise to such impairments and developing effective interventions is of prime interest in neuropsychiatric medicine.

While pharmacological interventions have been considerably successful in neuropsychiatric rehabilitation, they offer limited benefits in improving cognitive symptoms (7). Consequently, innovative interventions targeting cognitive dysfunction are urgently needed (8). Here, we highlight research that has laid important groundwork for the potential development of novel, drug-free, circuit-based therapeutics for cognitive improvement. We focus on a noninvasive neuromodulation technique called transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Over the last decade, tACS has been shown to improve various cognitive functions by leveraging the rhythmic functional architecture of cognitive networks (9, 10). We draw attention to specialized tACS designs that manipulate interregional phase synchronization and cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) to improve cognitive function. We briefly review the role of rhythmic brain network synchronization in cognition and its breakdown in psychiatric disorders. We discuss tACS methodology and putative mechanisms of action, and highlight several study design considerations for improved rigor and reproducibility. Finally, we review how tACS can modulate synchronization patterns in healthy humans to improve various cognitive functions that are also implicated in psychiatric disorders, and we speculate on the future of the field with an eye toward clinical applications.

NETWORK SYNCHRONIZATION UNDERPINS HUMAN COGNITION

Human cognition emerges from the coordinated activity of distributed large-scale brain networks operating at different spatiotemporal scales (11). Successful coordination of neural activity depends on transient synchronization (or temporal correlation) among distinct brain rhythms, observable in meso- and macroscale electrophysiological recordings, such as electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), electrocorticography (ECoG), and local field potentials (LFPs) (12–15). Synchronization is remarkably flexible and precise and has been implicated in the neural communication and plasticity underlying flexible goal-directed action and cognition (12–14). By establishing excitability windows, synchronization gates the transmission of information in the form of phase-coordinated local neuronal spiking within or between spatially segregated regions. Synchronization also promotes spike timing–dependent plasticity through correlated timing of pre- and postsynaptic potentials, increasing the probability of inducing synaptic plasticity between regions over time. For these reasons, synchronization is considered a core mechanism to sculpt communication dynamics and plasticity of brain-wide networks that underpin human cognition.

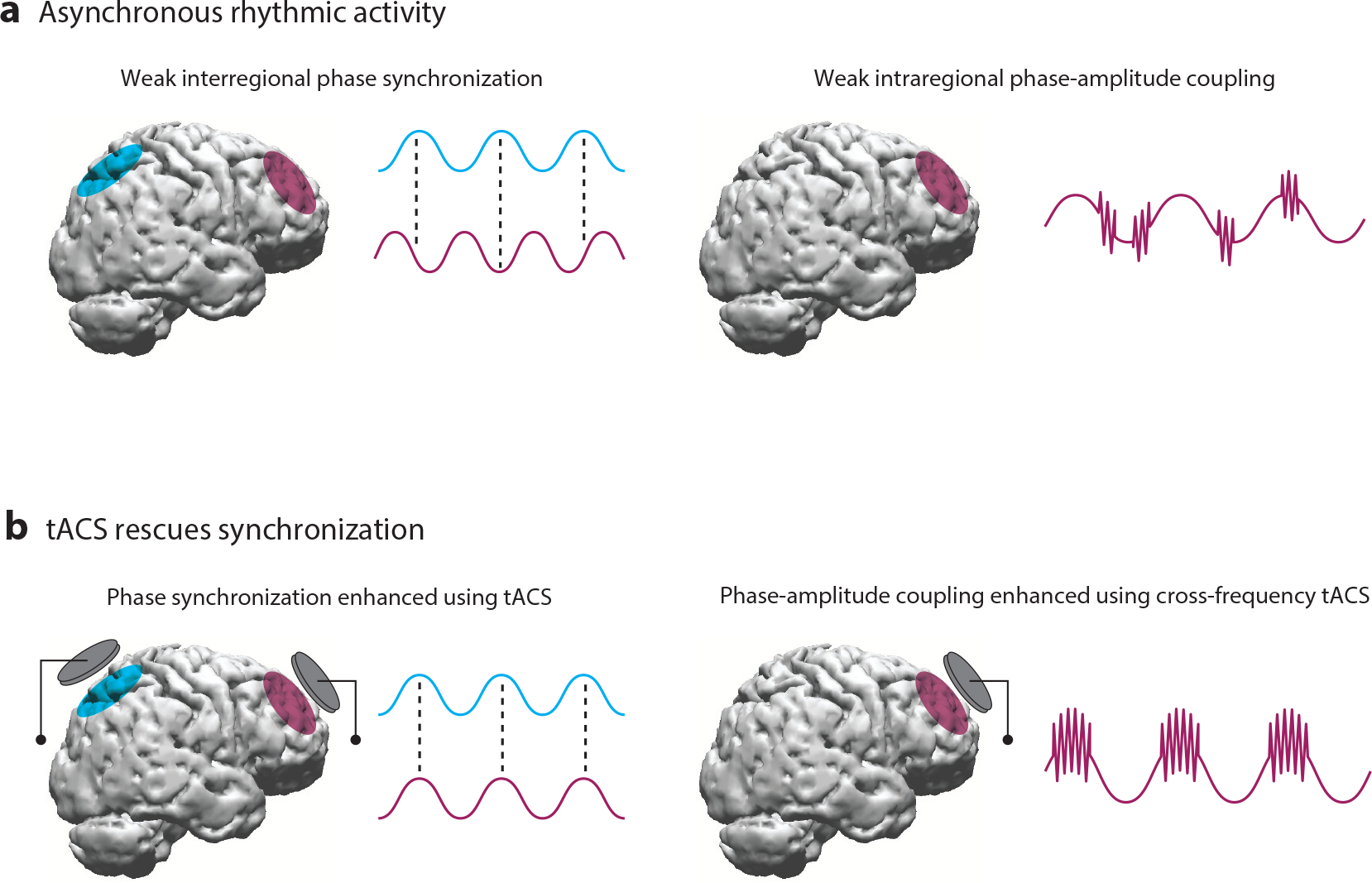

Many synchronization protocols exist for intra- and interregional coordination of neural activity during cognition. One of the most-studied protocols is cross-frequency PAC, which occurs when the amplitude of a high-frequency brain rhythm (proposed to index local neuronal spiking) is synchronized or coupled to the phase of a low-frequency rhythm (proposed to control neuronal excitability) (Figure 1a, right; Figure 1b, right) (16). PAC represents a flexible mechanism for how dynamic information can be integrated across spatiotemporal scales within a nested cortical network (13). In human cognition and goal-directed action, PAC has been observed in, over, or between a variety of brain structures, such as the temporal cortex (17–20), basal ganglia (21), medial frontal cortex (22), prefrontal-motor (23), medial-lateral prefrontal (24), and frontoparietal areas (25). PAC has been recorded using MEG (17, 18, 20), extracranial EEG (18, 19, 22, 24), and intracranial EEG (18, 21, 23, 25), and it has been linked to numerous cognitive processes, such as selective attention (25), working memory (18–20), memory sequencing (17), abstract goal maintenance (23), reward processing (21, 24), and feedback valence coding or decision making (22). The multiple converging lines of evidence across spatial scales, recording techniques, and cognitive domains support PAC as an important synchronization protocol for the coordination of large-scale neuronal activity underlying cognition.

Figure 1.

(a) Asynchronous rhythmic activity in the brain during cognition. Left: The blue and magenta signals reflect rhythmic activity from the corresponding cortical regions. Weak interregional phase synchronization manifests as inconsistent relative phases between the two signals over time, evident in the different phases at which one signal reaches its peak relative to the other signal. Right: During cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling (PAC), the amplitude of a high-frequency rhythm is phase-locked to the phase of a low-frequency rhythm. In this example, the magenta signal from the corresponding cortical region shows high-frequency activity that is only weakly phase-locked to the underlying low-frequency rhythm, thereby exhibiting weak PAC. Although here we show intraregional PAC, PAC can also be observed across regions. (b) Synchronous rhythmic activity following transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Left: Phase-specific multisite tACS at the regions of interest leads to enhancement in interregional phase synchronization reflected in the consistent relative phases between the two regions over time following stimulation. Right: Delivering cross-frequency tACS at the region of interest leads to phase-locking of high-frequency activity to the low-frequency rhythm reflecting enhanced PAC.

Another dominant synchronization protocol critical for orchestrating spatiotemporal neuronal activity relevant to cognition is within-frequency phase synchronization (12, 14, 15, 18). Phase synchronization is the process during which two or more rhythmic neuronal signals oscillate with consistent relative phase angles at the same frequency (Figure 1a, left; Figure 1b, left). Such synchronization is commonly observed between spatially segregated cortical areas and is thought to facilitate integration of information across long distances in the brain. Patterns of interregional synchronization have been observed intracranially (26), as well as in EEG/MEG recordings in humans (19, 20, 27). During cognition, phase synchronization has been observed in various frequency bands including theta (4–8 Hz) (19, 20, 27, 28), alpha (8–12 Hz) (29, 30), beta (12–30 Hz) (29, 31), and gamma (>30 Hz) (29) ranges; across various regions including frontoparietal (27, 29, 31), frontotemporal (19, 20, 26), medial-lateral prefrontal (28), and thalamocortical areas (30); and during various cognitive processes such as working memory (19, 20, 27, 29, 31), selective attention (30), memory retrieval (26), and adaptive or executive control (28). Since synchronized interregional activity is observed during many cognitive functions, its role in facilitating communication across the brain has received considerable interest.

Cross-frequency PAC and interregional phase synchronization are two mechanisms deemed essential for coordinating communication across the brain. In certain instances, breakdown of one mechanism can also have downstream effects on the other, with a significant impact on cognition (19, 32). Their breakdown may form the mechanistic basis of a variety of cognitive deficits in many neuropsychiatric disorders.

ABNORMAL NETWORK SYNCHRONIZATION UNDERPINS COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION

Altered structural and functional connectivity is a fundamental feature of the pathophysiology of many neuropsychiatric conditions (33). As brain rhythms facilitate temporal coordination among functional networks (12, 34), disruptions in establishing these networks and coordinating communication among them may be a consequence of disturbances in these brain rhythms (Figure 1a) (35, 36). Indeed, abnormal synchronization among functionally relevant brain rhythms across different spatiotemporal scales has been documented in various neuropsychiatric conditions (35–41), in addition to the significant alterations in the strength of localized brain rhythms during cognition (37). Here, we document some critical observations of impaired network synchronization during cognitive dysfunction.

Schizophrenia is characterized as a “disconnection syndrome” marked by abnormal interactions among large-scale cortical networks (40). As rhythmic synchronization coordinates these interactions, evidence of disconnection might be instantiated in atypical synchronization during cognition. Indeed, schizophrenia patients show global hyperconnectivity at rest, which leads to inflexibility in changing the synchronization patterns as per task demands (42–44). Inability to change global synchronization patterns dynamically contributes to impairments in sustained attention (42), detection of infrequent stimuli (43), selection of competing responses through cognitive control (44), and maintenance and manipulation of information in working memory (45). Cognitive deficits are further associated with disruptions in cross-frequency PAC. Executive control deficits may arise when gamma activity (46) and theta phase (47), estimated to derive from the lateral prefrontal cortex, fail to synchronize with theta phase over the anterior cingulate cortex. Working memory impairments are accompanied by reduced coupling between theta phase and gamma amplitude in frontal regions (48). Imprecise synchronization reduces the efficiency and increases the metabolic costs of synchronous networks, ultimately disrupting working memory (49). These observations suggest significant presence of suboptimal and atypical synchronization patterns associated with cognitive deficits as predicted by the disconnection hypothesis of schizophrenia.

Various other cognitive disorders show synchronization deficits. Similar to schizophrenia, individuals with ADHD show global hyperconnectivity at baseline, which limits their ability to adjust theta-band connectivity during cognitive control (50). Impairments in working memory have been linked with disruptions in a synchronization framework involving alpha, theta, and gamma frequency activity. Deficits in interregional alpha synchronization are observed during working memory in ASD (51) and Parkinson’s disease (52). Atypical phase-locking of alpha rhythms to gamma rhythms has also been associated with working memory deficits accompanying aging (53). Such deficits have also been linked to reduced interregional phase synchronization in the theta-band and theta–gamma PAC in older adults (19), with the latter also observed during mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (54). In addition to impaired synchronization in cortical networks associated with working memory processing, aberrant synchronization among task-irrelevant networks in the beta band has been reported in MDD (55), suggesting a broad shift in global synchronization architecture. Beyond working memory, impairments in alpha-gamma PAC have also been reported during face processing (56) and joint attention (the ability to share a point of view with another person) (57) which may contribute to deficits in social cognition. Taking the observations of these studies together, a significant prevalence of impaired synchronization during cognitive dysfunction in multiple neuropsychiatric conditions becomes evident.

Association of cognitive dysfunction with atypical patterns of synchrony, particularly in schizophrenia and ASD, has led to an emerging perspective where patterns of synchrony are increasingly recognized as endophenotypes of these disorders (40), bridging behavioral and neurological scales of pathology. We further propose that these synchrony patterns are a promising target for next-generation neuromodulation in medicine. By targeting these synchrony patterns (Figure 1), we can improve the precise timing of communication among dysfunctional brain networks to enhance cognition.

NONINVASIVE RHYTHMIC NEUROMODULATION

tACS is a noninvasive technique designed to perturb macroscopic brain network dynamics (58–60). Low-intensity, sinusoidal electric currents are delivered on the scalp to modulate the activity of an underlying cortical region. Neuronal populations at the targeted region are then entrained to the frequency of the applied alternating current (9, 61, 62). For optimum entrainment, advanced designs using high-definition tACS (HD-tACS) allow optimization of stimulation sites and current amplitudes to maximize the intensity or focality of stimulation at the target region. Side effects of tACS are minimal, limited to itching, tingling, and warming sensations for a few seconds during the ramping phases at the beginning and end of the stimulation (63). These effects can be controlled for using sham stimulation which mimics the ramping of the current but does not typically deliver any current during the rest of the stimulation period (commonly twenty to thirty minutes). In addition, “active” sham protocols are being increasingly used to test frequency and location specificity of the observed effects and rule out potential contributions of peripheral costimulation, such as transretinal or transcutaneous effects (19, 27, 28, 64–68). In sum, tACS allows safe, noninvasive, placebo-controlled, and frequency-specific entrainment of neuronal activity.

The physiological mechanisms that underlie tACS inform its potential as a tool for rehabilitative neuromodulation. During tACS, spiking activity in the targeted regions becomes increasingly phase-locked to the externally applied rhythmic electric field (61). As a consequence, the neuronal networks are entrained to the applied frequency (62). If the applied frequency is similar to the intrinsic frequency of the network, even weak electric fields can lead to entrainment of the network (60). Computational modeling suggests that entrainment at frequencies closer to the intrinsic frequency leads to strengthening of synaptic weights due to spike timing–dependent plasticity (69). As a result, effects observed during stimulation can persist beyond the duration of stimulation (70). Interestingly, cognitive dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders is associated with both deficits in rhythmic activity (37) and changes in synaptic plasticity in cortical areas (71). Through frequency-specific temporal realignment of ongoing neuronal activity and consequent modulations in synaptic plasticity, tACS may be well suited for rehabilitative neuromodulation in neuropsychiatric populations.

The voltage gradient in the target region induced by the applied electric field is an important factor influencing the ability of tACS to modulate neuronal activity. Early studies using in vitro and in vivo rodent models suggested a variable range of 0.2–1 V/m as necessary for neuromodulation via temporal realignment of neuronal activity (72, 73). Subsequent examination in nonhuman primate models and human intracranial studies suggested that scalp currents of 1–2 mA, as commonly used in human tACS studies, produced voltage gradients of 0.12–0.8 V/m at the target sites (74–76), in agreement with the observations in rodent models. Recently, Krause and colleagues have reported corroborating evidence in primate models that voltage gradients as low as 0.2 V/m are effective in reliably locking neuronal activity to the phase of the externally applied electric fields by altering neuronal spike timing, without changing the spiking rate (61). It is important to note that entrainment is a consequence of modulation of neuronal spike timing, and not alterations in spiking rate, which generally require stronger gradients (77). Current intensities needed to achieve voltage gradients sufficient to modulate the spiking rate in the target region are well within the limits deemed safe for human use, and no serious adverse events have been reported so far (63). Thus, tACS produces voltage gradients that are sufficient to entrain the neuronal activity in a given target region in a safe and noninvasive manner.

Several factors motivate the need for personalized neuromodulation designs to improve the effectiveness of tACS. Anatomical differences across individuals can lead to variable voltage gradients in the target regions (78), which can be improved by developing personalized neuromodulation designs via MRI-guided current-flow modeling. Physiological differences across individuals must also be taken into account because neuromodulation has been shown to be superior when tailored to the intrinsic frequency of behaviorally relevant brain networks (19, 64, 70) as predicted by computational models (69). The effects of tACS can also differ with the state of the brain during neuromodulation (79, 80), motivating closed-loop tACS designs where the neuromodulation parameters are adjusted on the fly according to the brain state at a given time. With due consideration of these factors, tACS designs can be personalized to be maximally effective for an individual.

IMPROVING COGNITION BY EXTERNALLY MODULATING NETWORK SYNCHRONIZATION

Over the past decade, multiple studies have used tACS to modulate rhythmic brain activity and behavior. In many such studies, tACS is directed to a single region of interest at one frequency, so as to modulate the rhythmic activity in that region and improve perceptual and cognitive functions (9, 10). Recently, more complex tACS protocols have been developed which manipulate interregional synchronization and cross-frequency PAC. Phase-specific multisite neuromodulation (Figure 1b, left) through application of alternating currents at various cortical sites with precisely controlled relative phases has been shown to influence the degree of entrainment of cortical networks (28, 81) and consequent behavior (19, 27, 28, 82, 83). Cross-frequency PAC can be induced within a region using alternating current waveforms that mimic the PAC profiles relevant for cognition (Figure 1b, right) (65, 84). Here, we elaborate studies which manipulate interregional phase synchronization or cross-frequency PAC to improve cognitive function.

Improvements in working memory have been reported following interregional synchronization of rhythms using tACS. Polanía and colleagues (27) applied a sinusoidally varying current in the theta frequency over the left frontal and parietal sites. Crucially, the currents delivered at the two sites were either inphase (i.e., with 0° relative phases across sites) or antiphase (i.e., with 180° relative phases). Inphase synchronization of frontoparietal areas improved the response speed in a working memory task compared to sham stimulation. Desynchronizing the two areas using antiphase stimulation increased the response speed compared with sham stimulation, suggesting the effects to be acutely specific to the relative phases between frontoparietal areas. A subsequent study added further support. Violante and colleagues (83) synchronized the right frontoparietal network in the theta band in participants performing verbal working memory tasks of varying complexity. Inphase synchrony among the right frontoparietal sites led to faster response speeds in the more complex two-back working memory task. Functional neuroimaging during bursts of tACS in a subsequent experiment showed phase-dependent changes in the local activity and connectivity pattern in the frontoparietal network. Converging observations from both studies suggest that phase-specific manipulation of synchronization within the frontoparietal network can improve working memory.

Synchronizing brain rhythms may be particularly useful for individuals with suboptimal working memory. Reinhart & Nguyen (19) examined synchronization patterns underlying working memory deficits in older adults. Compared with young adults, older adults exhibited poorer working memory performance associated with reduced theta–gamma PAC in the temporal cortex. Further, local PAC deficits in the temporal cortex arose due to reduced theta-phase synchronization between the frontotemporal areas. Using HD-tACS, the authors synchronized activity in the frontotemporal areas at the intrinsic theta frequency of the frontotemporal network individually determined for each participant. Inphase synchronization improved working memory in older adults, and in younger adults with poorer baseline performance, by restoring the deficient PAC in the temporal cortex. Control experiments underscored the crucial role of intrinsic synchrony between the two areas, as neither modulating the frontal cortex or the temporal cortex alone nor inducing synchrony at nonpersonalized frequencies yielded benefits. In young adults, antiphase synchronization was accompanied by impairments in working memory performance. This observation confirms the effects to be sensitive to the relative phase between the frontotemporal areas and suggests that bidirectional control over these circuits could be achieved by manipulating the relative phase among these sites. These findings demonstrate that improving the temporal coordination among functionally relevant networks in a frequency- and phase-specific manner improves working memory in older adults and in poor-performing young adults. Additionally, preferential benefits in individuals with weak working memory have also been reported through synchronization of the parietal cortices. In a series of studies, Tseng and colleagues (68, 85) have shown that synchronizing bilateral parietal cortices inphase in the theta band or antiphase in the gamma band improves working memory performance only in individuals with low working memory capacity. Alpha synchronization within the parietal cortices has been shown to improve inhibition of irrelevant information during working memory maintenance in aging populations (67). Therefore, synchronizing brain rhythms may be most beneficial to populations with suboptimal cognition.

Enhancing coupling among brain regions is also beneficial for other cognitive abilities. The medial frontal cortex synchronizes with the lateral prefrontal cortex in the theta band when there is an increased need for executive control following various events in learning or decision-making contexts, such as motor errors, punishing feedback, conflict, or novel stimuli (86). If the two regions are synchronized by applying inphase HD-tACS, the ability to adapt and learn from feedback improves (28), subject to the intrinsic brain state of the individual (80). Further, desynchronizing the circuit between the medial and lateral frontal cortices with antiphase HD-tACS causes impairments in adaptive control and learning, which can be promptly recovered using inphase HD-tACS (28). These observations indicate that when the coupling across brain networks is precisely targeted, behavioral improvements can be rapidly induced. The importance of timing across frontoparietal cortices is also evident in improving attentional abilities, as pushing the beta connectivity between the left frontal and right parietal cortices out of phase improves target detection (87). In addition to the relative phase of the alternating current, the precise spatial targeting of the relevant cortical circuit appears to play a vital role in determining the effectiveness of tACS in causing bidirectional changes during attention-demanding tasks (88, 89). Other higher-order individual traits such as creativity and intelligence, which are hallmarks of human cognition, can be modulated by inphase stimulation of the bilateral frontal cortices in the alpha band (90). In sum, synchrony modulation among neuronal networks has been demonstrated to impact various cognitive abilities and can be potentially generalized to a broad category of neuropsychiatric conditions where such abilities are most impaired.

In the work summarized, two or more brain regions received sinusoidal stimulation at a particular phase relationship in a given frequency to nudge the brain networks to function synchronously in that frequency (Figure 1b, left). It is also possible to manipulate temporal coordination across frequency bands and deliver more complex neuromodulation waveforms (Figure 1b, right). Alekseichuk and colleagues (65) delivered cross-frequency tACS over the frontal cortex to enhance working memory by modulating the coupling between theta phase and gamma amplitude. The protocol reflected a summation of theta-frequency alternating current and a theta phase–specific gamma-frequency alternating current. Improvements in working memory performance were observed when the gamma power was synchronized with the peaks of the theta wave. Such phase-specific cross-frequency modulations can be useful for populations like older adults who exhibit differences in cross-frequency phase relationships (19, 53). A similar cross-frequency manipulation has been shown to impact decision making. Polanía and colleagues (84) manipulated local PAC in the medial frontopolar and parietal cortices and the relative phases between them. Gamma-frequency alternating currents at each site were modulated by a theta-frequency envelope, with the relative phase of the envelope manipulated between the two sites. Parametric modulations of value-based decision making were observed as a function of the relative phases between the sites, suggesting that local PAC manipulations, when combined with phase-specific interregional synchronization, can further improve the effectiveness of tACS. These reports demonstrate the flexibility of tACS in manipulating complex rhythmic interactions such as cross-frequency PAC underlying cognitive function.

Taken together, these studies highlight that many cognitive abilities can be improved if synchronization in behaviorally relevant networks is modulated through tACS. Specifically targeting interregional phase synchronization and cross-frequency PAC may further enhance the effectiveness of single-site tACS designs that have been shown to induce significant but modest improvements in cognition (10). Despite the encouraging evidence from these studies in healthy humans, such improvements have not yet been translated to clinical populations. To our knowledge, no studies have yet been conducted that have modulated interregional synchronization or cross-frequency PAC in clinical populations. Few pilot studies have examined the effectiveness of synchronous multisite neuromodulation in patients with MDD (66), schizophrenia (91), and therapy-resistant OCD (92). However, these studies observed mixed effects on broad symptom profiles due to small sample sizes and did not explicitly examine improvements in cognitive symptoms. Future research should leverage the prevalent evidence of aberrant synchronization in cognitively impaired populations and examine the effectiveness of synchronizing within- and cross-frequency dynamics in behaviorally relevant networks in improving cognitive deficits sustainably.

CONCLUSION AND THE FUTURE

Cognitive dysfunction is a disabling feature of many neuropsychiatric disorders, affecting abilities such as selective attention, working memory, executive control, and decision making (8). Here, we have reviewed the potential of noninvasively modulating synchronization among brain rhythms using tACS to improve cognition. Such interventions are rooted in decades of basic science suggesting that the functional architecture of cognition rests upon coordinated communication across different spatiotemporal scales in the brain (12). The importance of coordinated communication is evidenced by synchronized rhythmic activity in healthy individuals during cognition and by rhythmic disorganization in clinical disorders (40). We propose that the search for noninvasive, safe, and targeted interventions for improving cognition can be accelerated by capitalizing on neuromodulation therapeutics that selectively target the physiological patterns of synchronization impaired during cognitive dysfunction. While different disorders are characterized by patterns of hyperconnectivity and hypoconnectivity (39), tACS allows bidirectional manipulation of connectivity, suggesting its potential in a wide variety of clinical disorders (19, 28). Additionally, subthreshold neuronal modulation during tACS alleviates any risk of significant discomfort and side effects such as seizures (63). Its safety is complemented by its portability, cost-effectiveness, and ease of administration. These factors make tACS-based neuromodulation of neuronal synchronization particularly attractive for improving cognitive deficits in clinical populations.

Several lines of ongoing research seek to improve our understanding of the mechanisms of tACS and the factors that can improve its effectiveness. Various studies have sought to pair tACS with concurrent neuroimaging such as EEG (62), MEG (93), and functional brain imaging (83), with extensive discussions on how these concurrent measurements can be improved (94), complementing work from animal models examining in vivo effects of electrical neuromodulation (61). Concurrent electrophysiology and neuroimaging also facilitate technical and analytical advancements in the development of closed-loop tACS designs (95). In such designs, neuromodulation parameters are adjusted online according to the physiological characteristics of the networks underlying a cognitive activity to improve the effectiveness of the neuromodulation. Particularly for multisite neuromodulation (Figure 1a, left; Figure 1b, left), better understanding of the spatial distribution of electric fields at different relative phases can lead to improved neuromodulation designs (96, 97) with longer-lasting outcomes. The effects of neuromodulation can be further characterized by examining cognitive networks using graph-theoretic approaches from network science to holistically elucidate the large-scale communication dynamics in the brain (98). Although the field of rhythmic synchronization is still in its infancy, technical advancements that allow sophisticated multimodal neuromodulation designs for performing and analyzing the effects of tACS (see the sidebar titled Subcortical Neuromodulation with Temporal Interference) will inform its best applications in clinical populations.

SUBCORTICAL NEUROMODULATION WITH TEMPORAL INTERFERENCE.

Noninvasive electrical stimulation tools have accelerated the development of targeted therapeutics for cognitive impairments. However, the neuronal targets of these therapeutics are limited to the cortical surface at safe stimulation intensities, leaving subcortical structures relevant for cognition outside the scope of direct modulation. Recently, a form of neuromodulation specifically designed to target subcortical structures has been proposed and validated in rodent models (99). The technique, called temporal interference (TI), uses multisite application of high-frequency oscillatory currents differing in their frequencies by a small amount. On its own, a high-frequency oscillatory current is unable to influence neuronal activity due to the low-pass filtering by neuronal membranes. However, if multiple oscillatory sources differing in frequency by a small amount are placed so as to converge at a deep brain site, their destructive interference produces electric fields oscillating at a frequency slow enough to modulate neuronal activity, without modulating activity in the surrounding tissue. The stimulation target can be steered within the subcortical space by adjusting the current ratios in the stimulating electrodes, providing unprecedented control during online stimulation. Ongoing efforts to adapt this exciting conceptual breakthrough to humans may revolutionize the efforts to enhance cognition impacted by subcortical pathologies.

In conclusion, rhythmic neuromodulation using tACS presents an exciting opportunity for the development of interventions that derive from rigorous observations of large-scale electrophysiology during cognition. Synchronization of functionally relevant brain rhythms may provide robust and sustained relief from cognitive deficits in various neuropsychiatric disorders.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Cognitive dysfunction is central to many neuropsychiatric disorders, and there is an urgent need to develop safe therapeutics for cognitive enhancement.

Interregional phase synchronization and cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) are synchronization protocols fundamental to coordinated communication dynamics in the brain during healthy cognitive function.

Deficits in selective attention, working memory, and executive control in various neuropsychiatric conditions are marked by atypical phase synchronization and cross-frequency PAC.

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) is a safe and noninvasive neuromodulation technique to precisely manipulate the synchronization patterns underlying cognition.

Manipulation of behaviorally relevant synchronization patterns is associated with improvements in attention, working memory, and executive control in healthy humans.

Modulating synchronization patterns using tACS has potential for correcting atypical synchronization underlying cognitive impairments in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, paving the way for safe, noninvasive, and drug-free interventions for cognitive dysfunction.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Can synchrony modulation using tACS be validated as a viable intervention for cognitive enhancement in clinical populations, both alone and in conjunction with existing treatments?

Anatomical and physiological personalization might be key to improve the effectiveness of synchrony modulation. Can we map the anatomical and physiological variables that can enhance the strength and sustainability of the induced enhancements?

Cognitive impairments can manifest in complex patterns across disorders. Can the functional physiological profile be integrated with the characteristic behavioral and symptom profiles from a clinical examination to develop clinically relevant neuromodulation designs?

How are the strength and sustainability of tACS-induced improvements associated with parameters such as intensity, duration, or repetition of dosage of the intervention?

Cognitive function relies on coordinated activity of large-scale networks. Can we develop sophisticated neuromodulation designs capable of stimulating more than two locations simultaneously to target larger brain networks?

Can innovations in neuromodulation technology allow improved flexibility and control over the spatiotemporal profile of the alternating current, including complex cross-frequency waveforms, during multisite stimulation to alter more intricate network interactions and the direction of information flow as per cognitive demands?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-MH-114877, R01-AG-063775) and a generous gift from a private philanthropist. The authors also thank Breanna Bullard for assistance with the literature search.

Glossary

- Selective attention:

The process of selecting certain stimuli in the environment to process while ignoring distracting information

- Working memory:

A limited-capacity system for short-term storage and manipulation of information for goal-directed behavior

- Executive control:

A set of cognitive processes necessary for the control of information processing and behavior using proactive, reactive, or inhibitory measures

- Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS):

A noninvasive neuromodulation technique in which alternating currents are applied transcranially, entraining brain networks to the frequency of the applied waveform

- Phase synchronization:

A synchronization protocol in which multiple brain regions exhibit correlated phases of rhythmic activity at a common frequency

- Phase-amplitude coupling (PAC):

A synchronization protocol in which the amplitude of a high-frequency rhythm is modulated by the phase of a low-frequency rhythm

- Spike timing–dependent plasticity:

A form of synaptic plasticity dependent upon the relative timing of pre- and postsynaptic spiking, hypothesized to underlie tACS effects

- Entrainment:

The temporal alignment of neuronal activity driven by an external rhythmic source such as an alternating current

- High-definition tACS (HD-tACS):

An advanced tACS technique with improved spatial resolution and greater control over intensity and orientation of the electric field delivered to targeted regions

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Vaidya CJ, Stollstorff M. 2008. Cognitive neuroscience of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: current status and working hypotheses. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 14(4):261–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalkstein S, Hurford I, Gur RC. 2010. Neurocognition in schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 4:373–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron-Cohen S, Belmonte MK. 2005. Autism: a window onto the development of the social and the analytic brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28:109–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burdick KE, Robinson DG, Malhotra AK, et al. 2008. Neurocognitive profile analysis in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 14(4):640–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marazziti D, Consoli G, Picchetti M, et al. 2010. Cognitive impairment in major depression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 626(1):83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurtz MM, Gerraty RT. 2009. A meta-analytic investigation of neurocognitive deficits in bipolar illness: profile and effects of clinical state. Neuropsychology 23(5):551–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millan MJ. 2006. Multi-target strategies for the improved treatment of depressive states: conceptual foundations and neuronal substrates, drug discovery and therapeutic application. Pharmacol. Ther. 110(2):135–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brüne M, et al. 2012. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11(2):141–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vosskuhl J, Strüber D, Herrmann CS. 2018. Non-invasive brain stimulation: a paradigm shift in understanding brain oscillations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schutter DJLG Wischnewski M. 2016. A meta-analytic study of exogenous oscillatory electric potentials in neuroenhancement. Neuropsychologia 86:110–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzsáki G 2006. Rhythms of the Brain. Oxford/New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel M, Donner TH, Engel AK. 2012. Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13:121–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helfrich RF, Knight RT. 2016. Oscillatory dynamics of prefrontal cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20(12):916–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fries P 2015. Rhythms for cognition: communication through coherence. Neuron 88(1):220–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. 2012. The origin of extracellular fields and currents—EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13(6):407–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardin JA, Carlén M, Meletis K, et al. 2009. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459(7247):663–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heusser AC, Poeppel D, Ezzyat Y, et al. 2016. Episodic sequence memory is supported by a theta-gamma phase code. Nat. Neurosci. 19(10):1374–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fell J, Axmacher N. 2011. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12(2):105–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhart RMG, Nguyen JA. 2019. Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 22(5):820–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daume J, Gruber T, Engel AK, et al. 2017. Phase-amplitude coupling and long-range phase synchronization reveal frontotemporal interactions during visual working memory. J. Neurosci. 37(2):313–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen MX, Axmacher N, Lenartz D, et al. 2009. Good vibrations: cross-frequency coupling in the human nucleus accumbens during reward processing. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21(5):875–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen MX, Elger CE, Fell J. 2009. Oscillatory activity and phase-amplitude coupling in the human medial frontal cortex during decision making. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21(2):390–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voytek B, Kayser AS, Badre D, et al. 2015. Oscillatory dynamics coordinating human frontal networks in support of goal maintenance. Nat. Neurosci. 18(9):1318–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinhart RMG, Woodman GF. 2014. Oscillatory coupling reveals the dynamic reorganization of large-scale neural networks as cognitive demands change. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26(1):175–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szczepanski SM, Crone NE, Kuperman RA, et al. 2014. Dynamic changes in phase-amplitude coupling facilitate spatial attention control in fronto-parietal cortex. PLOS Biol. 12(8):e1001936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watrous AJ, Tandon N, Conner CR, et al. 2013. Frequency-specific network connectivity increases underlie accurate spatiotemporal memory retrieval. Nat. Neurosci. 16(3):349–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polanía R, Nitsche MA, Korman C, et al. 2012. The importance of timing in segregated theta phase-coupling for cognitive performance. Curr. Biol. 14:1314–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinhart RMG. 2017. Disruption and rescue of interareal theta phase coupling and adaptive behavior. PNAS 114(43):11542–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palva JM, Monto S, Kulashekhar S, et al. 2010. Neuronal synchrony reveals working memory networks and predicts individual memory capacity. PNAS 107:7580–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saalmann YB, Pinsk MA, Wang L, et al. 2012. The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas based on attention demands. Science 337(6095):753–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salazar RF, Dotson NM, Bressler SL, et al. 2012. Content-specific fronto-parietal synchronization during visual working memory. Science 338:1097–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Nicolai C, Engler G, Sharott A, et al. 2014. Corticostriatal coordination through coherent phase-amplitude coupling. J. Neurosci. 34(17):5938–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bullmore E, Sporns O. 2009. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10(3):186–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buzsáki G, Draguhn A. 2004. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science 304(5679):1926–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. 2015. Oscillations and neuronal dynamics in schizophrenia: the search for basic symptoms and translational opportunities. Biol. Psychiatry 77(12):1001–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voytek B, Knight RT. 2015. Dynamic network communication as a unifying neural basis for cognition, development, aging, and disease. Biol. Psychiatry 77(12):1089–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Başar E 2013. Brain oscillations in neuropsychiatric disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15(3):291–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathalon DH, Sohal VS. 2015. Neural oscillations and synchrony in brain dysfunction and neuropsychiatric disorders: It’s about time. JAMA Psychiatry 72(8):840–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. 2006. Neural synchrony in brain disorders: relevance for cognitive dysfunctions and pathophysiology. Neuron 52(1):155–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. 2012. Neuronal dynamics and neuropsychiatric disorders: toward a translational paradigm for dysfunctional large-scale networks. Neuron 75(6):963–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uhlhaas PJ. 2015. Neural dynamics in mental disorders. World Psychiatry 14(2):116–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennan AM, Williams LM, Harris AWF. 2018. Intrinsic, task-evoked and absolute gamma synchrony during cognitive processing in first onset schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 99:10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cea-Cañas B, Gomez-Pilar J, Núñez P, et al. 2020. Connectivity strength of the EEG functional network in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 98:109801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma A, Weisbrod M, Kaiser S, et al. 2011. Deficits in fronto-posterior interactions point to inefficient resource allocation in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 123(2):125–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griesmayr B, Berger B, Stelzig-Schoeler R, et al. 2014. EEG theta phase coupling during executive control of visual working memory investigated in individuals with schizophrenia and in healthy controls. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 14(4):1340–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Popov T, Wienbruch C, Meissner S, et al. 2015. A mechanism of deficient interregional neural communication in schizophrenia. Psychophysiology 52(5):648–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reinhart RMG, Zhu J, Park S, et al. 2015. Synchronizing theta oscillations with direct-current stimulation strengthens adaptive control in the human brain. PNAS 112(30):9448–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barr MS, Rajji TK, Zomorrodi R, et al. 2017. Impaired theta-gamma coupling during working memory performance in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 189:104–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bassett DS, Bullmore ET, Meyer-Lindenberg A, et al. 2009. Cognitive fitness of cost-efficient brain functional networks. PNAS 106(28):11747–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michelini G, Jurgiel J, Bakolis I, et al. 2019. Atypical functional connectivity in adolescents and adults with persistent and remitted ADHD during a cognitive control task. Transl. Psychiatry 9(1):137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Urbain C, Vogan VM, Ye AX, et al. 2016. Desynchronization of fronto-temporal networks during working memory processing in autism. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37(1):153–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiesman AI, Heinrichs-Graham E, McDermott TJ, et al. 2016. Quiet connections: reduced fronto-temporal connectivity in nondemented Parkinson’s disease during working memory encoding. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37(9):3224–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinal D, Zurrón M, Díaz F, et al. 2015. Stuck in default mode: inefficient cross-frequency synchronization may lead to age-related short-term memory decline. Neurobiol. Aging 36(4):1611–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goodman MS, Kumar S, Zomorrodi R, et al. 2018. Theta-gamma coupling and working memory in Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salvadore G, Cornwell BR, Sambataro F, et al. 2010. Anterior cingulate desynchronization and functional connectivity with the amygdala during a working memory task predict rapid antidepressant response to ketamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(7):1415–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khan S, Gramfort A, Shetty NR, et al. 2013. Local and long-range functional connectivity is reduced in concert in autism spectrum disorders. PNAS 110(8):3107–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaime M, McMahon CM, Davidson BC, et al. 2016. Brief report: reduced temporal-central EEG alpha coherence during joint attention perception in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46(4):1477–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bestmann S, Walsh V. 2017. Transcranial electrical stimulation. Curr. Biol. 27(23):R1258–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schutter DJLG. 2014. Syncing your brain: electric currents to enhance cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18(7):331–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miniussi C, Harris JA, Ruzzoli M. 2013. Modelling non-invasive brain stimulation in cognitive neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37(8):1702–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krause MR, Vieira PG, Csorba BA, et al. 2019. Transcranial alternating current stimulation entrains single-neuron activity in the primate brain. PNAS 116(12):5747–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Helfrich RF, Schneider TR, Rach S, et al. 2014. Entrainment of brain oscillations by transcranial alternating current stimulation. Curr. Biol. 24(3):333–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Antal A, Alekseichuk I, Bikson M, et al. 2017. Low intensity transcranial electric stimulation: safety, ethical, legal regulatory and application guidelines. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128(9):1774–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grover S, Nguyen JA, Viswanathan V, et al. 2020. High-frequency neuromodulation improves obsessive-compulsive behavior. Nat. Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alekseichuk I, Turi Z, Amador de Lara G, et al. 2016. Spatial working memory in humans depends on theta and high gamma synchronization in the prefrontal cortex. Curr. Biol. 26(12):1513–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alexander ML, Alagapan S, Lugo CE, et al. 2019. Double-blind, randomized pilot clinical trial targeting alpha oscillations with transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Transl. Psychiatry 9(1):106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borghini G, Candini M, Filannino C, et al. 2018. Alpha oscillations are causally linked to inhibitory abilities in ageing. J. Neurosci. 38(18):4418–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tseng P, Chang Y-T, Chang C-F, et al. 2016. The critical role of phase difference in gamma oscillation within the temporoparietal network for binding visual working memory. Sci. Rep. 6:32138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zaehle T, Rach S, Herrmann CS. 2010. Transcranial alternating current stimulation enhances individual alpha activity in human EEG. PLOS ONE 5(11):e13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vossen A, Gross J, Thut G. 2015. Alpha power increase after transcranial alternating current stimulation at alpha frequency (α-tACS) reflects plastic changes rather than entrainment. Brain Stimul. 8(3):499–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goto Y, Yang CR, Otani S. 2010. Functional and dysfunctional synaptic plasticity in prefrontal cortex: roles in psychiatric disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 67(3):199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reato D, Rahman A, Bikson M, et al. 2010. Low-intensity electrical stimulation affects network dynamics by modulating population rate and spike timing. J. Neurosci. 30(45):15067–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ozen S, Sirota A, Belluscio MA, et al. 2010. Transcranial electric stimulation entrains cortical neuronal populations in rats. J. Neurosci. 30(34):11476–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Opitz A, Falchier A, Yan C-G, et al. 2016. Spatiotemporal structure of intracranial electric fields induced by transcranial electric stimulation in humans and nonhuman primates. Sci. Rep. 6:31236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kar K, Duijnhouwer J, Krekelberg B. 2017. Transcranial alternating current stimulation attenuates neuronal adaptation. J. Neurosci. 37(9):2325–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang Y, Liu AA, Lafon B, et al. 2018. Correction: Measurements and models of electric fields in the in vivo human brain during transcranial electric stimulation. eLife 7:e35178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vöröslakos M, Takeuchi Y, Brinyiczki K, et al. 2018. Direct effects of transcranial electric stimulation on brain circuits in rats and humans. Nat. Commun. 9(1):483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kasten FH, Duecker K, Maack MC, et al. 2019. Integrating electric field modeling and neuroimaging to explain inter-individual variability of tACS effects. Nat. Commun. 10(1):5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alagapan S, Schmidt SL, Lefebvre J, et al. 2016. Modulation of cortical oscillations by low-frequency direct cortical stimulation is state-dependent. PLOS Biol. 14(3):e1002424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nguyen J, Deng Y, Reinhart RMG. 2018. Brain-state determines learning improvements after transcranial alternating-current stimulation to frontal cortex. Brain Stimul. 11(4):723–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schwab BC, Misselhorn J, Engel AK. 2019. Modulation of large-scale cortical coupling by transcranial alternating current stimulation. Brain Stimul. 12(5):1187–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Helfrich RF, Knepper H, Nolte G, et al. 2014. Selective modulation of interhemispheric functional connectivity by HD-tACS shapes perception. PLOS Biol. 12(12):e1002031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Violante IR, Li LM, Carmichael DW, et al. 2017. Externally induced frontoparietal synchronization modulates network dynamics and enhances working memory performance. eLife 6:e22001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polanía R, Moisa M, Opitz A, et al. 2015. The precision of value-based choices depends causally on fronto-parietal phase coupling. Nat. Commun. 6:8090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tseng P, Iu K-C, Juan C-H. 2018. The critical role of phase difference in theta oscillation between bilateral parietal cortices for visuospatial working memory. Sci. Rep. 8(1):349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cavanagh JF, Frank MJ. 2014. Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18(8):414–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yaple Z, Vakhrushev R. 2018. Modulation of the frontal-parietal network by low intensity anti-phase 20 Hz transcranial electrical stimulation boosts performance in the attentional blink task. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 127:11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hsu W-Y, Zanto TP, van Schouwenburg MR, et al. 2017. Enhancement of multitasking performance and neural oscillations by transcranial alternating current stimulation. PLOS ONE 12(5):e0178579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hsu W-Y, Zanto TP, Gazzaley A. 2019. Parametric effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation on multitasking performance. Brain Stimul. 12(1):73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lustenberger C, Boyle MR, Foulser AA, et al. 2015. Functional role of frontal alpha oscillations in creativity. Cortex 67:74–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mellin JM, Alagapan S, Lustenberger C, et al. 2018. Randomized trial of transcranial alternating current stimulation for treatment of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry 51:25–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Klimke A, Nitsche MA, Maurer K, et al. 2016. Case report: successful treatment of therapy-resistant OCD with application of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Brain Stimul. 9(3):463–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Neuling T, Ruhnau P, Fuscà M, et al. 2015. Friends, not foes: magnetoencephalography as a tool to uncover brain dynamics during transcranial alternating current stimulation. Neuroimage 118:406–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Noury N, Siegel M. 2018. Analyzing EEG and MEG signals recorded during tES, a reply. NeuroImage 167:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ketz N, Jones AP, Bryant NB, et al. 2018. Closed-loop slow-wave tACS improves sleep-dependent long-term memory generalization by modulating endogenous oscillations. J. Neurosci. 38(33):7314–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alekseichuk I, Falchier AY, Linn G, et al. 2019. Electric field dynamics in the brain during multi-electrode transcranial electric stimulation. Nat. Commun. 10(1):2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Saturnino GB, Madsen KH, Siebner HR, et al. 2017. How to target inter-regional phase synchronization with dual-site transcranial alternating current stimulation. Neuroimage 163:68–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Avena-Koenigsberger A, Misic B, Sporns O. 2017. Communication dynamics in complex brain networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19(1):17–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grossman N, Bono D, Dedic N, et al. 2017. Noninvasive deep brain stimulation via temporally interfering electric fields. Cell 169(6):1029–41.e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]