Significance

Bismuth (Bi) is an ideal material platform for abundant and intriguing solid-state physics, such as spin orbitronics, where spin-charge conversion (SCC) attracts great attention both in fundamental and applied physics. However, the SCC efficiency of Bi was quite small despite its large spin-orbit interaction, which is one of the biggest mysteries in condensed-matter physics for the decade. We solved the mystery and achieved the first large spin conversion efficiency in Bi (17 to 27%) by introducing rhombohedral (110) Bi by finding the anisotropic effective g-factor of Bi is the key for the successful observation of the large efficiency of Bi(110) and the negligibly small efficiency of Bi(111). Our finding opens new directions for spin-related condensed-matter physics focusing on anisotropy of the effective g-factor.

Keywords: spin Hall effect, bismuth, g-factor

Abstract

While the effective g-factor can be anisotropic due to the spin-orbit interaction (SOI), its existence in solids cannot be simply asserted from a band structure, which hinders progress on studies from such viewpoints. The effective g-factor in bismuth (Bi) is largely anisotropic; especially for holes at T-point, the effective g-factor perpendicular to the trigonal axis is negligibly small (<0.112), whereas the effective g-factor along the trigonal axis is very large (62.7). We clarified in this work that the large anisotropy of effective g-factor gives rise to the large spin conversion anisotropy in Bi from experimental and theoretical approaches. Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance was applied to estimate the spin conversion efficiency in rhombohedral (110) Bi to be 17 to 27%, which is unlike the negligibly small efficiency in Bi(111). Harmonic Hall measurements support the large spin conversion efficiency in Bi(110). A large spin conversion anisotropy as the clear manifestation of the anisotropy of the effective g-factor is observed. Beyond the emblematic case of Bi, our study unveiled the significance of the effective g-factor anisotropy in condensed-matter physics and can pave a pathway toward establishing novel spin physics under g-factor control.

Physical properties of solids can be largely dependent on crystal axis. A good example is the electric conductivity, the second-rank tensor, which can be anisotropic in a crystal with low crystal inversion symmetry. Such anisotropy is determined by the anisotropy in energy eigenvalues, i.e., an energy band structure. The spin Hall conductivity, which plays a dominant role in modern spin physics such as spintronics, spin orbitronics, and spin conversion physics, is the third-rank tensor. Since the additional rank comes from the spin direction, the spin Hall conductivity couples with the anisotropy of spin magnetic moment, i.e., the effective g-factor, g*, expressed as the coefficient of the effective Zeeman splitting EZ* = g*μBH, where μB is the Bohr magneton and H is the magnetic field (1). In the case where the relativistic correction is relevant, the spin current Js is described as the product of the velocity v times the spin magnetic momentum g*σz/2, where σz is the z-component of the Pauli spin matrix (e.g., equation [90] in ref. 1 and the other studies (2–4). Details will be described in the Discussion part). Therefore, the anisotropy of spin magnetic moment, or effective g-factor, yields the anisotropy of the spin Hall conductivity. Note that the Js = σzv is often used to describe the spin current by assuming g* = 2 and the g* does not appear explicitly. Since the effective g-factor anisotropy is attributed to the spin-orbit interaction (SOI) and sensitive to the description of the wave function (5), the existence of the anisotropy of the effective g-factor cannot be simply asserted from the anisotropy of the Fermi surface in the band structure and enables exploring novel unprecedented spin-related physical phenomena. In general, the effective g-factor anisotropy is quite small in weak SOI elements [1.06 in graphite (6), 1.0006 in silicon (7), and 2.2 in strained Ge (8)]. Bismuth (Bi) is one of the most intensively studied elements in condensed matter physics, and indeed, a wide variety of attractive physics such as the Seebeck effect, the Nernst effect, the Shubnikov–de Hass oscillation, and de Haas–van Alphen effect, has been discovered by using Bi. These discoveries are ascribed to unique and exotic electronic states of Bi, and the largest SOI among safe elements and the anisotropic and large effective g-factor [14.4 for electron at the L-point and 560 for hole at the T-point (9–13)] also originate from the electronic state of Bi. Considering the coupling between the spin Hall conductivity and effective g-factor, spin conversion properties in Bi can be gigantically dependent on the crystal orientation.

The SOI plays a pivotal role in condensed matter physics and has attracted broad attention in view of spin-momentum locking in topological quantum materials (14–16), spin-charge interconversion in solids (17, 18), spin manipulation in inorganic semiconductors (19–22), etc. Among the SOI-originated spin functions, spin-charge interconversion using the SOI is now attracting many physicists to accelerate the understanding of fundamental spin physics in solids. A representative spin-charge interconversion effect attributed to the SOI is the inverse spin Hall effect (23, 24), the reciprocal effect of the spin Hall effect (SHE) (20, 21). The spin Hall angle θSH is an index of the spin conversion efficiency and is regarded to depend on the magnitude of the SOI. The strength of the SOI is roughly proportional to the fourth power of atomic number Z (25, 26), and the magnitudes of the θSH of heavy elements such as β-Ta (27), β-W (28), and Pt (29) are estimated to be 0.12, 0.33 and 0.08, respectively. Here, the magnitude ζ of the SOI for the 5d electrons in Pt was calculated to be 46.1 mRy (30, 31). If the SOI of a material is the sole factor determining the spin conversion efficiency, Bi (ζ ~ 106.8 mRy for the 6p electrons) could exhibit the highest efficiency, resulting in the largest θSH. However, spin conversion in Bi was quite small (θSH << 0.1) in previous studies using rhombohedral (111) and polycrystalline Bi (32–37). Given that Bi inherently possesses substantial SOI strength, the reason for the negligibly small θSH in the previous studies is quite unclear, which is one of the biggest mysteries in solid-state physics.

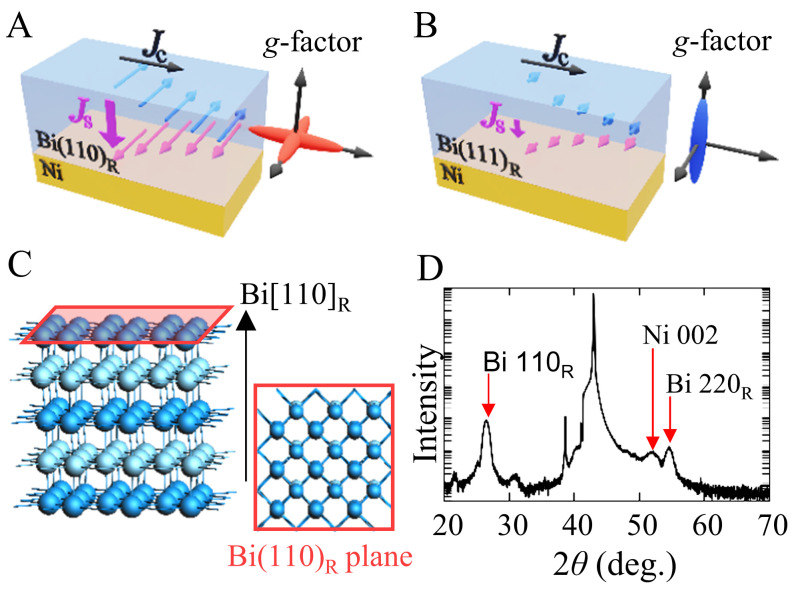

Here, in this work, we shed light on the spin conversion physics of rhombohedral (110) Bi [Bi(110)R], which has been a less explored structure of Bi. Contrary to rhombohedral (111) Bi [Bi(111)R], a large spin conversion efficiency can be expected in Bi(110)R because its semimetallicity and large effective g-factor help generation of high spin polarization in plane of Bi film, which cannot occur in Bi(111)R where possible electron evacuation in thin films takes place (38) and the effective g-factor of holes can have a finite component only in the trigonal [Bi(111)R] direction (9–11) (Fig. 1 A and B). An accomplished method to estimate the spin Hall angle of solids, spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR), was applied, and the effect of the self-induced spin-orbit torque (SOT) (39–43) in an adjacent ferromagnet of the Bi(110)R was taken into account to obtain compelling results enabling precise estimation of the θSH of Bi(110)R. The θSH of Bi(110)R is estimated to be 0.17, although that of Bi(111)R was quite small (32–37). Harmonic Hall measurements provided steadfast supporting evidence of this large efficiency. By considering the anisotropy of the effective g-factor in Bi, our findings resolve the mystery of the reported quite small spin conversion efficiency which is incompatible with the large SOI in Bi.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the relationship between the anisotropic effective g-factor of Bi and generation of a spin current via SHE Js for (A) Bi(110)R (in this study) and (B) Bi(111)R. Here, the subscript R indicates a rhombohedral structure. (C) Schematic of Bi(110)R structure and the Bi(110)R plane view from the Bi[110]R direction. (D) X-ray diffraction pattern (Cu-Kα radiation) of the Ni/Bi film. Peaks at 38.5 and 43.1° were obtained from the MgO(001) substrate in Kβ radiation and Kα radiation, respectively.

Results

An epitaxial Ni(5 nm)/Bi(tBi) film was grown on a single-crystal MgO(001) substrate by molecular beam epitaxy. The Bi layer, the thickness tBi of which ranged from 0 to 12 nm with a wedged structure, was grown with substrate cooling (<250 K) to obtain a (110)-oriented rhombohedral epitaxial film (44) (Fig. 1C). Fig. 1D shows a θ-2θ X-ray diffraction profile obtained from the Ni/Bi film. A clear face-centered cubic (fcc) 002 Ni peak and a rhombohedral 110 Bi peak were observed, indicating that highly oriented Bi(110)R was grown on single-crystal Ni, as expected from the in situ reflection high energy diffraction (RHEED) measurement during the growth process (see SI Appendix for the RHEED spectra). We also prepared Ni/Bi and Fe/Bi samples with and without substrate cooling during the Bi growth for control experiments. Unless otherwise noted, the Ni/Bi film with substrate cooling is used in the main text. The Ni/Bi film was formed into 10 μm × 65 μm rectangular channels and connected to Ti(3 nm)/Au(150 nm) electrodes by using Ar-ion milling, electron-beam (EB) lithography, and EB evaporation (See SI Appendix for the effect of baking on the Ni/Bi interface). For the ST-FMR measurement, the electrode was fabricated as the channel in the form of the signal lines of shorted coplanar waveguides. Here, the longitudinal direction of the Ni/Bi channel was designed to be in the Ni[010] direction. The ST-FMR measurement (29, 45) was carried out by injecting an rf current with an input power of 10 mW and applying an external magnetic field along ϕ = 45° and ϕ = 225° with respect to the longitudinal direction of the Ni/Bi channel (Fig. 2A). An Oersted field and a spin current from Bi produced by the SHE induce magnetization precession in Ni. Then, the resistance of the channel oscillates due to the anisotropic magnetoresistance, resulting in the DC voltage VDC as a spin-torque diode effect (45) (see Materials and Methods for details).

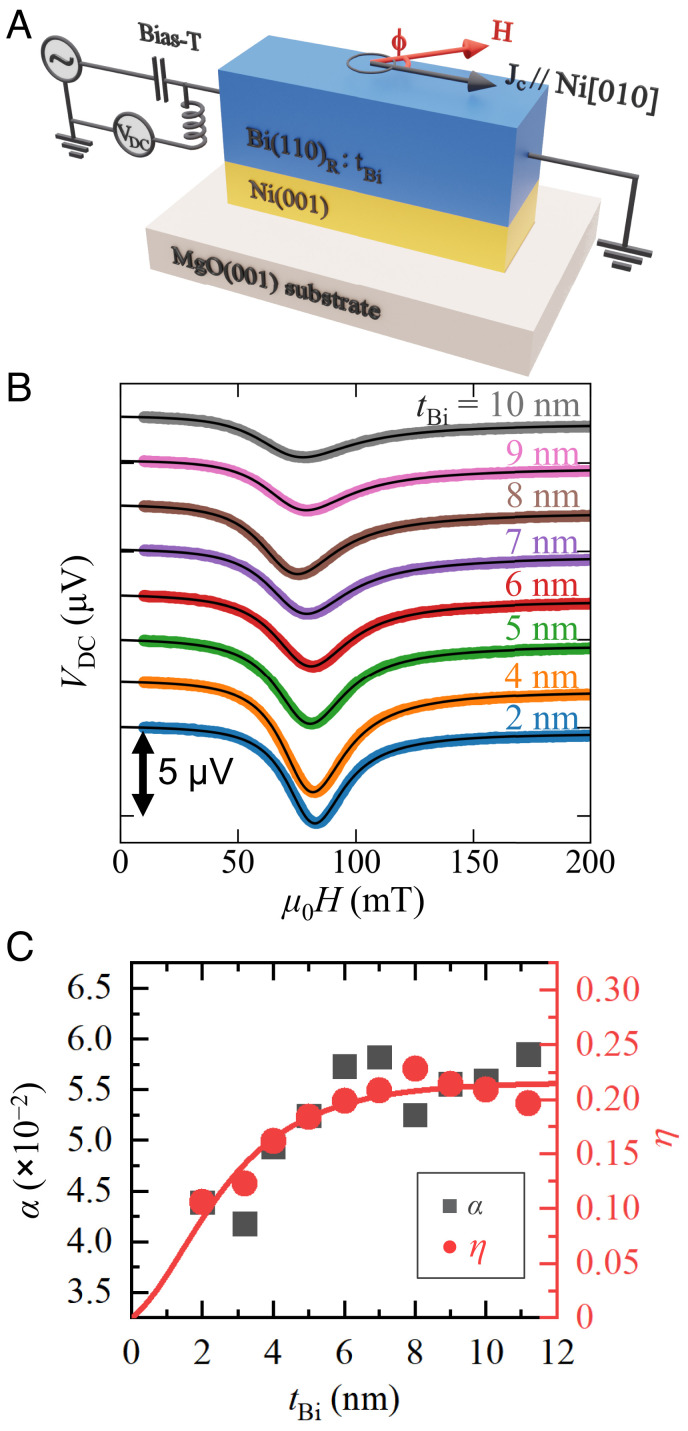

Fig. 2.

ST-FMR measurement on Ni/Bi(110)R. (A) Schematic of the setup of the ST-FMR measurement. (B) ST-FMR signals obtained from the Ni/Bi(tBi) channel at 7 GHz. Here, tBi ranges from 2 to 12 nm. Solid lines indicate the fitting with Eq. 1 for each tBi. (C) Bi thickness dependence of the Gilbert damping parameter α (black squares) and the spin-charge conversion efficiency η (red filled circles). α and η increase with increasing Bi thickness and start to saturate at approximately 6 nm Bi thickness. The red solid line indicates the fitting result considering the self-induced SOT in Ni. The calculation well reproduces the data when θBi is equal to 0.17.

Fig. 2B shows the Bi thickness dependence of the ST-FMR spectra. The frequency was set to 7 GHz in this experiment. The ST-FMR signal can be deconvoluted into symmetric and antisymmetric Lorentzian signals by fitting the following equation (29):

| [1] |

where C is a coefficient concerning the anisotropic magnetoresistance, S is the symmetric component, A is the antisymmetric component, μ0 is the vacuum permeability, Hres is the resonance field, Δ is the half-width at half-maximum of the spectrum, and a and b are coefficients of the linear background. Here, Hres and Δ are related to the characteristics of the magnetization dynamics and are evaluated through frequency dependence. Since we used single-crystal fcc (001) Ni as the ferromagnetic layer, the Kittel equation concerning the magnetocrystalline anisotropy was used to fit the frequency dependence of Hres (see SI Appendix for the full expression of the Kittel equation) (46). The frequency f dependence of Δ can be fitted with the following equation (47): Δ = Δ0 + 2παf/γ, where Δ0 is the frequency-independent scattering parameter, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, and α is the Gilbert damping parameter. Both frequency dependences were well fitted, and thus, we can discuss the magnetic properties based on the ST-FMR measurement results (see SI Appendix for the frequency dependence of the ST-FMR signals and their evaluations). The Gilbert damping parameter increases with increasing Bi thickness and starts to be saturated at approximately tBi = 6 nm (Fig. 2C). Since the Gilbert damping parameter depends on the spin torque induced by the injection of the spin current from Bi via the SHE, it depends on the spin diffusion length of Bi (48). Thus, this result indicates that we observed the SHE in bulk Bi, not interfacial effects, and more importantly, the saturation of the damping parameter at approximately 6 nm is a manifestation of the short spin diffusion length in Bi(110)R.

The spin-charge conversion (SCC) efficiency, η, is in principle estimated from the ratio of S and A. The Bi thickness dependence of η is shown in Fig. 2C, where the dependence is quite similar to that of α. For precise estimation of the efficiency in ST-FMR, the self-induced SOT in Ni is taken into account as follows. Recently, the SHE occurring in a ferromagnet itself has been receiving attention (49–54). Since the SHE in a ferromagnet provides a substantial contribution in ST-FMR, the SOT induced by the spin current generated in the ferromagnet can be superimposed in the ST-FMR measurement (39–43). In particular, when the nonmagnetic layer of the ST-FMR device is highly resistive, most of the rf current is injected into the ferromagnetic layer, and the SOT generated in the ferromagnetic layer becomes large, resulting in overestimation of the spin-charge conversion efficiency of the nonmagnetic layer (43). Here, the typical conductivities of Bi and Ni are 2.4 × 105 S/m (55) and 8.0 × 106 S/m (53, 56), respectively, so the SOT from Ni should be considered for precise estimation of the spin-charge conversion in Bi. The red solid line in Fig. 2C shows the fitting result of the thickness dependence of η considering the self-induced SOT in Ni (see SI Appendix for the detailed parameters in the calculation). θBi = 0.17 allows the best fit in reproducing our experimental results, and the Bi layer is responsible for the spin-charge conversion in the Ni/Bi channels despite its high resistivity (notably, θBi can be augmented when the conductivity of Bi increases, i.e., the estimated efficiency here is a kind of lower limit; see also SI Appendix). The efficiency in Bi(110)R is comparable to that in heavy metals such as Pt and β-W, which means realization of one of the largest spin conversion efficiencies in solids. More importantly, a substantially large spin-charge conversion efficiency can be achieved in Bi(110)R, in sharp contrast to Bi(111)R (32, 33).

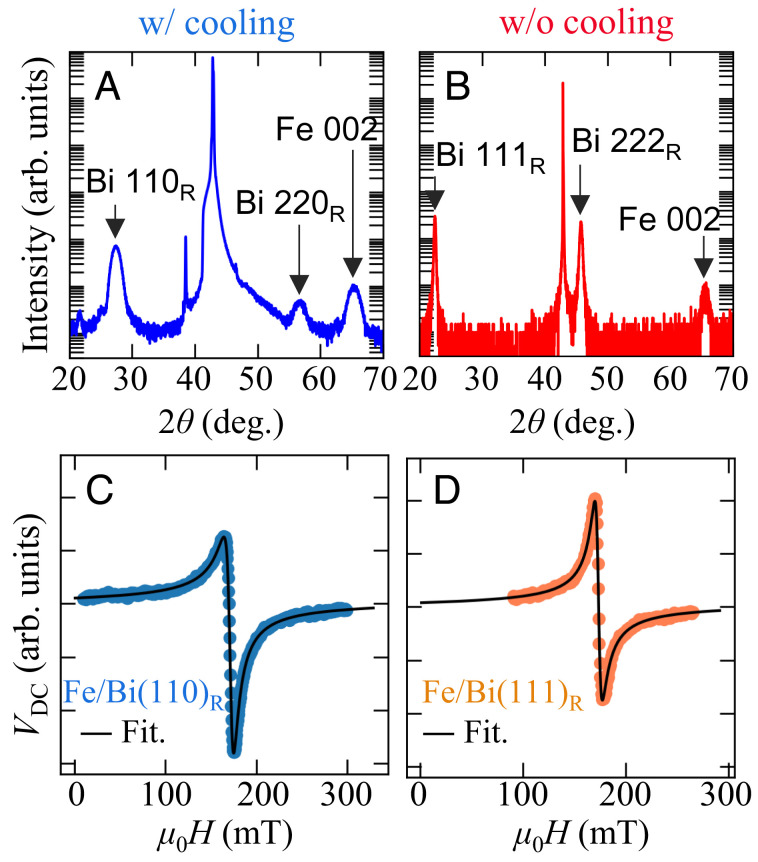

For the Fe/Bi samples, the substrate cooling changed crystal orientation of the Bi, Bi(110)R from the sample with cooling and Bi(111)R from the sample without cooling, as indicated by the XRD patterns (Fig. 3 A and B). Although XRD patterns were measured at different conditions and a peak from MgO looks different from each other, clear difference of Bi peaks due to their crystallinity was observed. We carried out the ST-FMR measurements on the Fe(6 nm)/Bi(10 nm) samples with different crystal structures as shown in Fig. 3 C and D. The ST-FMR signal strongly depends on the crystal orientation of Bi; the signal obtained from Fe/Bi(111)R exhibits almost only anti-symmetric component and the symmetric component attributed to the spin-orbit torque was almost missing. We estimated the spin-charge conversion (SCC) efficiency η to be 0.34 for Fe/Bi(110)R and −0.027 for Fe/Bi(111)R, respectively. As the previous study, Bi(111)R showed quite small SCC efficiency. On the other hand, we observed the large SCC in Bi(110)R as demonstrated in Ni/Bi(110)R as described above, indicating that crystal orientation strongly affects the SCC in Bi. These experiments and previous reports claiming the small SCC on Bi, especially for Bi(111)R allow concluding that the SCC of Bi possesses a large anisotropic SCC efficiency for Bi(110)R and Bi(111)R. We also emphasize that the large SCC is realized from the Bi grown from Fe with substrate cooling (lower temperature growth), while the small SCC takes place in the Bi grown on Fe without substrate cooling (higher temperature growth).

Fig. 3.

ST-FMR measurements on Bi(110)R and Bi(111)R. XRD spectra obtained from (A) Fe/Bi with (w/) substrate cooling, and (B) Fe/Bi without (w/o) substrate cooling during the Bi growth. ST-FMR signals obtained from (C) Fe/Bi(110)R, with substrate cooling during the Bi growth, and (D) Fe/Bi(111)R, without cooling.

To confirm the large spin-charge conversion efficiency in Bi(110)R, we carried out a harmonic Hall measurement (57–59). The Hall bar structure was fabricated from a Ni/Bi film, where the Bi thickness was 11 nm. The harmonic Hall measurement was carried out by injecting an rf current with an effective amplitude of 5 mA and applying an external magnetic field rotating in the plane of the Ni/Bi interface (ϕ = 0° – 360°). The second harmonic Hall voltage V2ω was measured with a lock-in amplifier (see Fig. 4A and SI Appendix for details). Fig. 4B shows the ϕ dependence of V2ω with μy0H = 0.2 T and μ0H = 4.0 T (see also SI Appendix for the result with other magnetic fields). V2ω was fitted with the following equation (59–61):

| [2] |

Fig. 4.

Harmonic hall measurement on Ni/Bi(110)R. (A) Schematic of the setup of the harmonic Hall measurement. Here, the Bi thickness was 11 nm. (B) Azimuth angle ϕ dependence of the second harmonic Hall voltage V2ω for various magnetic fields. Here, the magnetic field rotates in the plane of the Ni/Bi interface (ϕ = 0° – 360°). Solid lines indicate the fitting with Eq. 2 in the main text. (C) Magnetic field dependence of the fitting parameter A(H). A(H) was deconvoluted into the anomalous Hall voltage (red line), ordinary Nernst effect in Bi (green line), and anomalous Nernst effect in Ni (blue line). The black line indicates the sum of the three components. (D) Magnetic field dependence of the fitting parameter B(H). The solid line indicates the fitting with the definition of B(H) in Eq. 2.

where HDL and HFL are the damping-like torque effective field and the field-like torque effective field, respectively, HOe is the Oersted field, HK is the out-of-plane anisotropy field, VANE is the anomalous Nernst voltage, and VONE is the ordinary Nernst voltage. VAHE = 2.50 mV and VPHE = −0.72 mV are the anomalous Hall voltage and planar Hall voltage obtained from first harmonic voltage V1ω (see SI Appendix for details of the harmonic Hall measurement and fitting parameters). Fig. 4C shows the magnetic field H dependence of the fitting parameter, A(H). A(H) can be deconvoluted into three components (VAHE, VANE, and VONE as shown in Eq. 2), and we can derive μ0HDL = 160 μT from the VAHE component. From the magnetic field dependence of B(H), μ0(HFL + HOe) was estimated to be 29 μT (Fig. 4D). Here, μ0HOe = μ0IBi/2w was estimated to be 28 μT, where IBi is the electric current in Bi. The damping-like torque efficiency ξDL and field-like torque efficiency ξFL can be described with HDL and HFL as follows (62):

| [3] |

where w is the width of the Ni/Bi channel. ξDL and ξFL were estimated to be 2.7 × 10−1 and 2.4 × 10−3, respectively. We postulate transparency at the Ni/Bi interface, and θBi ~ ξDL = 0.27 was obtained from the harmonic Hall measurement. The ratio ξFL/ξDL was small, estimated to be 8.7 × 10−3 from the harmonic Hall measurement, which is very similar to the results of the ST-FMR measurement (see SI Appendix for details). Note that the difference in θBi obtained from the different measurements originated from the difference in the effects considered in the analysis except for the SHE in Bi: the ST-FMR analysis considered the self-induced SOT in the Ni layer, and the harmonic Hall measurement analysis included thermal effects such as the anomalous Nernst effect (ANE) in Ni and the ordinary Nernst effect (ONE) in Bi. Despite such differences, both measurements indicated a large spin-charge conversion efficiency in Bi. Thus, the result obtained from the harmonic Hall measurement strongly supports our claim that a large spin-charge conversion efficiency was achieved in our Bi(110)R, obtained from ST-FMR.

Discussion

Considering the large θBi (= 0.17) in our Bi(110)R and the negligibly small θBi in Bi(111)R (see Fig. 3 for control experiments on Fe/Bi(111)R and Fe/Bi(110)R. See also our previous study (32) and the study by the other group (33)), the anisotropy of physical properties in Bi should shed light on. Here, we emphasize that while the large θBi can inherently originate from the large atomic SOI of Bi, the large atomic SOI does not always rationalize the highly anisotropic θBi. Hence, we shed light on the anisotropy of the effective g-factor of Bi, which can couple with the spin Hall conductivity and determine spin conversion efficiency from a theoretical viewpoint to reveal the underlying physics of our findings.

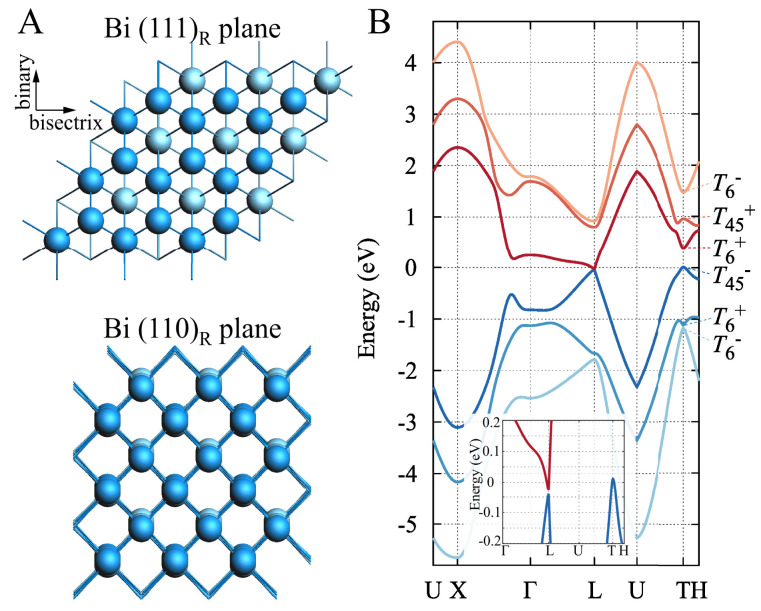

The anisotropy of the magnetic moment (or the effective g-factor) in Bi has been well established both experimentally and theoretically (9–13). In particular, the anisotropy of the effective g-factor of holes at the T-point is very large. Here, the effective g-factor is the coefficient that determines the spin magnetic moment of itinerant electrons, and it should be distinguished from Landé-like g-factor for the electrons in the isolated atom. The symmetry of the hole wave function (T45−) prohibits the effective g-factor from being oriented perpendicular to the trigonal direction (12) (Fig. 1 A and B). The effective g-factor of holes can have a finite component only in the trigonal direction, and indeed, this Ising-like effective g-factor has been experimentally confirmed (9–11). Fig. 5 shows the crystal structure and band structure of bulk Bi calculated by Liu-Allen's tight-binding model (63). The Bi [111]R direction corresponds to the trigonal axis. The thin Bi(111)R film consists of buckled honeycomb bilayers (BL). In contrast, the thin Bi(110)R film consists of almost flat quasi-square BL. In bulk Bi, electrons appear at the L-point, and holes appear at the T-point. The effective mass tensor mi, cyclotron mass mc, and effective g-factor g* for both electrons and holes determined experimentally are listed in Table 1 (11, 13). The spin splitting factor, given by the multiplication of the effective g-factor and the cyclotron mass as M = g*mc/2, expresses the SOI’s impact. (Note that M can be determined by the phase of the quantum oscillation.) Table 1 clearly shows that the M for holes is highly anisotropic compared to that for electrons. The effective g-factor perpendicular to the trigonal axis is shown to be vanishingly small (gbin = gbis < 0.112 within the experimental accuracy), whereas the effective g-factor along the trigonal axis is very large (gtri = 62.7) (see Materials and Methods for anisotropic effective g-factor due to the crystalline SOI).

Fig. 5.

Crystal structures of Bi(111)R and Bi(110)R. (A) Crystal structure of Bi. The atoms of different colors belong to different bilayers. (B) Band structure calculated by Liu-Allen's tight-binding model (63). T45,6 indicates the symmetry of the wave function at the T-point (12).

Table 1.

Effective mass tensor mi, cyclotron mass mc, effective g-factor g*, and spin splitting factor M = g*mc/2 for electrons and holes (11, 13)

| For electrons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1 (binary) | 2 (bisectrix) | 3 (trigonal) | 4 |

| mi | 0.00124 | 0.257 | 0.00585 | −0.0277 |

| m c | 0.0272 | 0.00189 | 0.0125 | – |

| g * | 66.2 | 1084 | 151 | – |

| M | 0.90 | 1.02 | 0.94 | – |

| For holes | ||||

| i | 1 (binary) | 2 (bisectrix) | 3 (trigonal) | 4 |

| mi | 0.0678 | 0.0678 | 0.721 | 0 |

| m c | 0.221 | 0.221 | 0.0678 | – |

| g * | 0.112 | 0.112 | 62.7 | – |

| M | 0.012 | 0.012 | 2.13 | – |

The spin current is strongly restricted by this directivity of the effective g-factor of hole. The spin Hall conductivity σs is given by the correlation function of spin current Js along y-direction and charge current Jc along x-direction as follows (1–4):

| [4] |

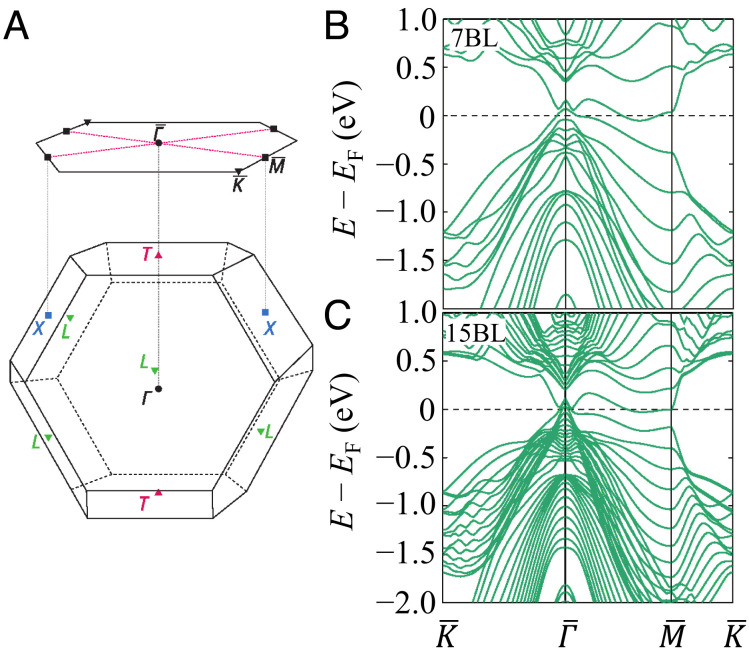

where the vi (i = x, y) is the velocity along i-direction, σz is the z-component of the Pauli spin matrix, and g* is the effective g-factor. (Precisely speaking, the current operator should be symmetrized as {gz*σz/2, vy}/2.) In the conventional nonmagnets, g* is regarded to be 2 and Js can be described as σzvy, where the effective g-factor does not appear explicitly. However, when g* is not equal to 2, that is the case for Bi, the contribution of the g* on σs should be considered and the full expression of Eq. 4 should be used. In the SHE, the spin current flows in the direction perpendicular to both the electric current and the effective g-factor. For holes at the T-point of Bi, the spin current can flow only in the trigonal plane, i.e., in the plane parallel to the (111)R interface. Consequently, the spin current is prohibited from being injected through the Bi(111)R interface. This can be the reason for the vanishingly small θBi in Bi(111)R. Meanwhile, the spin current can flow through the Bi(110)R interface, taking advantage of the large effective g-factor. Note that contributions from the electrons at the L-point have not been detected in Bi(111)R structures, which is ascribable to the evacuation of bulk electrons caused by the remarkable size effect with the tiny effective mass (mtri = 0.00585). In fact, such evacuation of bulk electrons has been observed for ultrathin Bi(111)R films (below 30 bilayers (30BL), less than 11.7 nm) (38). The previous [up to 10BL (64)] and our present first-principles (up to 15BL) calculations also support bulk electron evacuation in ultrathin Bi(111)R films. Fig. 6 shows the two-dimensional (2D) BZ for Bi(111)R film and its band structures for 7BL and 15BL. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using BAND software of Amsterdam Modeling Suite (65, 66) (see Materials and Methods for details). For the Bi(111)R surface, the -point in the 2D BZ corresponds to the Γ- and T-points in the bulk three-dimensional (3D) BZ, where holes appear. The -point in 2D corresponds to the L-point in 3D, where electrons appear. The bulk valence bands cross the Fermi energy at approximately the -point in the films with ≥ 7BL. In contrast, the bulk conduction bands ( -point) do not cross the Fermi energy in the films with ≤13BL. These results agree well with the previous calculations below 10BL (64). Even in the 15BL film (~6 nm), the bulk electron density is extremely low, although the bulk conduction band crosses the Fermi energy. This evacuation of bulk electrons is consistent with the experimental observation by Hirahara et al. (38). [see SI Appendix for the results of the first-principles calculations for various Bi thickness and Bi(110)R film]. Thus, the largely anisotropic effective g-factor of holes for Bi(111)R and Bi(110)R, and possible evacuation of electrons in Bi(111)R can rationalize the substantially large spin conversion efficiency in Bi(110)R and the absence of spin conversion in Bi(111)R.

Fig. 6.

Brillouin zone and band structure of Bi(111)R. (A) Brillouin zone for Bi(111)R and its band structures for (B) 7BL and (C) 15BL by DFT. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the Fermi energy.

Since Bi is an anisotropic material, we consider the other possible factors of the anisotropic spin Hall conductivity of Bi. It is well known that the electronic band structure of Bi is highly anisotropic. Therefore, the most plausible origin for the anisotropy except for the anisotropic effective g-factor can lie in the anisotropic band structure, which can be characterized in terms of the effective mass. Here, Bi(111)R has been previously studied and reported as the small spin Hall material (32–37), and electron evacuation has been observed from both experimental (38) and our theoretical studies. Therefore, we consider the anisotropy of holes in Bi. If we drop the effective g-factor, i.e., according to Eq. 4, the anisotropy of σs,yx is simply given in terms of the velocity, which is proportional to the square root of effective mass, in the form:

| [5] |

The effective mass is given as m = 0.068 for the binary and bisectrix axes and m = 0.72 for the trigonal axis in Bi(111)R (11). According to this calculation, there is no reason that the SHE for Bi(111)R is vanishingly small. (The anisotropy of spin Hall conductivity is evaluated to be 3.3 at most, σs,yx(Bi(110)R)/σs,yx(Bi(111)R) ≤3.3. see Materials and Methods for details.) Consequently, the anisotropic effective mass (and conductivity) scenario lacks enough theoretical grounds, and the large anisotropy of the SCC in Bi is nicely explained by considering the anisotropic effective g-factor of Bi. Another case of the anisotropic spin Hall angle was reported in IrMn3 (67), where notably large spin Hall angle of at maximum 0.35 was reported. However, its anisotropy is attributed to the non-collinear spin structure originating from Mn atoms where antiferromagnetic but ferroic magnetic domains are formed in the triangles within the (111) plane, which is essentially different physical concept from the effective g-factor anisotropy that governs the anisotropic spin conversion in Bi in our study.

We observed large spin conversion anisotropy in Bi. Unlike negligibly small efficiency in Bi(111)R, Bi(110)R exhibits large spin-charge conversion of 17%. This long-term–awaited large efficiency stems from the coexistence of the anisotropy of the effective g-factor and semimetalllic nature of Bi(110)R. The theoretical consideration focusing on the large effective g-factor anisotropy in Bi enables reconciliation of the large SOI in Bi and missing spin conversion in Bi(111)R. Although it has been widely recognized that the effective g-factor can be anisotropic due to the crystal SOI since more than half century ago, spin conversion utilizing the effective g-factor anisotropy has been unexplored. This work unveiled the significance of the effective g-factor anisotropy in condensed-matter physics. Furthermore, beyond the emblematic case of Bi, our findings can pave an avenue toward establishing novel spin physics under g-factor control.

Materials and Methods

Sample Fabrication.

An epitaxial Ni(5 nm)/Bi(tBi) film was grown on a single-crystal MgO(001) substrate by molecular beam epitaxy. First, the MgO substrate was annealed at 800 °C for 10 min. The 5 nm Ni layer was deposited at room temperature and postannealed at 350 °C for 15 min. The Bi layer, the thickness tBi of which ranged from 0 to 12 nm with a wedged structure, was grown with substrate cooling (<250 K) to obtain a (110)-oriented rhombohedral epitaxial film (44). The multilayer was capped with a MgO(5 nm)/SiO2(5 nm) layer to avoid surface oxidization. The Ni/Bi film was formed into 10 μm × 65 μm rectangular channels and connected to Ti(3 nm)/Au(150 nm) electrodes by using Ar-ion milling, EB lithography, and EB evaporation. For the ST-FMR measurement, the electrode was fabricated as the channel in the form of the signal lines of shorted coplanar waveguides. In contrast, for the harmonic Hall measurement, the channel was formed in the typical Hall bar structure, where the distance between two terminals was 35 μm and the width of the terminals were 5 μm. Here, the longitudinal direction of the Ni/Bi channel was designed to be in the Ni[010] direction. For EB lithography, we used a charge-dissipating agent (ESPACER 300Z, Showa Denko) on the EB lithography resist to avoid charge-up with the insulative substrate. To make ohmic contact on the channel with the electrode, Ar-ion milling in a load-lock chamber was performed to remove the capping layer prior to electrode deposition.

Measurement Setup.

The ST-FMR measurement (29, 45) was carried out by injecting an rf current with an input power of 10 mW produced by a signal generator and applying an external magnetic field along 45° and 225° with respect to the longitudinal direction of the Ni/Bi channel (Fig. 2A). The DC voltage VDC induced by the ferromagnetic resonance of the Ni layer was measured with a bias-T and a lock-in amplifier. The rf current frequency ranged from 7 to 12 GHz. For the Bi thickness dependence measurement, the frequency was set to 7 GHz. All measurements were carried out at room temperature.

The harmonic Hall measurement (57–59) was carried out by injecting an rf current with an effective amplitude of 5 mA and a frequency of 17 Hz produced by the internal source meter of a lock-in amplifier and applying an external magnetic field produced by a Physical Property Measurement System (Quantum Design) (Fig. 4A). The magnetic field ranged from 0.2 T to 4.0 T. The 2nd harmonic Hall voltage V2ω was measured by the lock-in amplifier with the magnetic field rotating in the plane of the Ni/Bi interface (ϕ = 0° – 360°). For estimation of the fitting parameters, 1st harmonic measurements with an out-of-plane magnetic field (anomalous Hall measurement) and with an in-plane ϕ = 0° – 360° (planar Hall measurement) were carried out. All measurements were carried out at room temperature.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using BAND software of Amsterdam Modeling Suite (65, 66). We used the Fast Inertial Relaxation Engine for geometry optimization (68). In the Generalized Gradient Approximation of DFT, the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional was used (69) together with double-zeta–polarized basis sets and numerical orbitals with a large frozen core. The relativistic effects were taken into account by the noncollinear method.

Anisotropic Effective g-Factor due to the Crystalline SOI.

The general formula of the effective g-factor is given in the following form:

| [6] |

| [7] |

where m is the electron mass and En is the energy of the n-th band (n = 0 is the band under consideration). tn and un are the interband matrix elements of the velocity operator between the 0th and nth bands for the same spins and opposite spins, respectively. The hole band (the top valence band) in Bi has T45− symmetry (cf. Fig. 5). It has the matrix elements only with T45+ and T6− as follows (12):

| [8] |

| [9] |

| [10] |

where an and bn are complex numbers and operator C is the product of space inversion and time-reversal operators, i.e., and are the Kramers doublet. The x-, y-, and z-directions are taken to be the binary, bisectrix, and trigonal directions, respectively. From Eq. 7, the effective g-factor is given by the outer products of tn and un. Therefore, only Gz has a finite component (cf. Eqs. 8–10). In contrast, Gx,y is zero because (tn × un)x,y = 0. Consequently, the effective g-factor is finite only when the magnetic field is parallel to the trigonal direction (Bi[111]R direction), and it is zero when the field is perpendicular to the trigonal direction. A schematic view of the highly anisotropic effective g-factor for holes is given in Fig. 1 A and B.

Evaluation of the Anisotropic SCC in Bi due to the Anisotropic Effective Mass.

Here, we consider the anisotropy of the SCC of holes in Bi when g* = 2 and σs can be expressed as Eq. 5. We also assume that (110) direction is close to the bisectrix axis. In the reality, they do not perfectly parallel, and the following estimation can overestimate the anisotropy. (Nevertheless, it is not enough to explain the observed anisotropy.) As for hole in Bi, binary and bisectrix axes are equivalent to each other so that we call them as bi-axes.

As for the Bi(111)R, charge current along average of bi-axes generates spin current along trigonal axis (tri-axis). Therefore, σs is described as

| [11] |

As for the Bi(110)R, charge current along tri- or binary-axes generates spin current along bisectrix-axis. When the charge current flows along tri-axes, σs is described as

| [12] |

Therefore, the ratio of σs in Bi(110)R to that in Bi(111)R is estimated as follows:

| [13] |

On the other hand, when the charge current flows along bi-axes, σs and the ratio are described as

| [14] |

| [15] |

By considering texture structure of Bi(110)R, the charge current flowing direction is mixture of bi- and tri-axes, so that we average them by using geometric mean:

| [16] |

As a result, the anisotropy of spin Hall conductivity can be estimated at most 3.3 only by considering the anisotropic effective mass. For the spin Hall angle, we also consider the anisotropy of conductivity along the charge current flowing direction. The conductivity is isotropic where charge current flows along binary axis, and the conductivity becomes anisotropic where charge current flows along trigonal axis. By taking their average, the anisotropy of the conductivity can be described as follows:

| [17] |

By using Eqs. 16 and 17, the ratio of the spin Hall angles is estimated to be 5.8. Consequently, the anisotropic effective mass (and conductivity) scenario lacks enough theoretical grounds.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (No. 16H06330), JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 19H01850), JSPS Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (A) (No. 22H00290), and the Spintronics Research Network of Japan. A part of this work was supported by the Kyoto University Nano Technology Hub through the “Nanotechnology Platform Project” sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Author contributions

R.O., Y.F., T.S., Y.A., S.M., and M. Shiraishi designed research; N.F., M.M., S.S., M. Shiga, and S.M. performed research; M.A. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; N.F., R.O., M.A., Y.F., and E.S. analyzed data; T.S. and Y.A. reviewed the manuscript critically; and N.F., R.O., Y.F., S.M., and M. Shiraishi wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. K.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Contributor Information

Ryo Ohshima, Email: ohshima.ryo.2x@kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Masashi Shiraishi, Email: shiraishi.masashi.4w@kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Fuseya Y., Ogata M., Fukuyama H., Transport properties and diamagnetism of dirac electrons in bismuth. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 012001 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukazawa T., Kohno H., Fujimoto J., Intrinsic and extrinsic spin hall effects of dirac electrons. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86, 094704 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernes A., Györffy B. L., Weinberger P., Spin currents, spin-transfer torque, and spin-Hall effects in relativistic quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. B 76, 012408 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowitzer S., Ködderitzsch D., Ebert H., Spin projection and spin current density within relativistic electronic-transport calculations. Phys. Rev. B 82, 140402(R) (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yafet Y., g factors and spin-lattice relaxation of conduction electrons. Solid State Phys. 14, 1–98 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagoner G., Spin resonance of charge carriers in graphite. Phys. Rev. 118, 647–653 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson D. K., Feher G., Electron spin resonance experiments on donors in silicon. III. Investigation of excited states by the application of uniaxial stress and their importance in relaxation processes. Phys. Rev. 124, 1068–1083 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson D. K., Electron spin resonance experiments on shallow donors in germanium. Phys. Rev. 134, A265–A286 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith G. E., Baraff G. A., Rowell J. M., Effective g factor of electrons and holes in bismuth. Phys. Rev. 135, A1118–A1124 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 10.V. S. Édel’man, Electrons in bismuth. Adv. Phys. 25, 555–613 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Z., Fauqué B., Fuseya Y., Behnia K., Angle-resolved Landau spectrum of electrons and holes in bismuth. Phys. Rev. B 84, 115137 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuseya Y., et al. , Origin of the large anisotropic g factor of holes in bismuth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 216401 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Z., Fauqué B., Behnia K., Fuseya Y., Magnetoresistance and valley degree of freedom in bulk bismuth. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 313001 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasan M. Z., Kane C. L., Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi X.-L., Zhang S.-C., Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armitage N. P., Mele E. J., Vishwanath A., Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otani Y., Shiraishi M., Oiwa A., Saitoh E., Murakami S., Spin conversion on the nanoscale. Nat. Phys. 13, 829–832 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando Y., Shiraishi M., Spin to charge interconversion phenomena in the interface and surface states. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86, 011001 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nitta J., Akazaki T., Takayanagi H., Enoki T., Gate control of spin-orbit interaction in an inverted In0.53Ga0.47As/In0.52Al0.48As heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1335–1338 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato Y. K., Myers R. C., Gossard A. C., Awschalom D. D., Observation of the spin hall effect in semiconductors. Science 306, 1910–1913 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami S., Nagaosa N., Zhang S.-C., Dissipationless quantum spin current at room temperature. Science 301, 1348–1351 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S., et al. , Synthetic Rashba spin–orbit system using a silicon metal-oxide semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 20, 1228–1232 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saitoh E., Ueda M., Miyajima H., Tatara G., Conversion of spin current into charge current at room temperature: Inverse spin-Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 182509 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valenzuela S. O., Tinkham M., Direct electronic measurement of the spin Hall effect. Nature 442, 176–179 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjorken J. D., Drell S. D., Relativistic Quantum Mechanics (McGraw-Hill Science Engineering, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H. L., et al. , Scaling of spin hall angle in 3d, 4d, and 5d metals from Y3Fe5O12/metal spin pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 197201 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L., et al. , Spin-torque switching with the giant spin hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pai C.-F., et al. , Spin transfer torque devices utilizing the giant spin Hall effect of tungsten. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 122404 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L., Moriyama T., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance induced by the spin hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koelling D. D., Harmon B. N., A technique for relativistic spin-polarised calculations. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 10, 3107–3114 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai T., et al. , Split fermi surface properties of LaTGe3 (T: transition metal) and PrCoGe3 with the non-centrosymmetric crystal ctructure. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 064717 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emoto H., et al. , Transport and spin conversion of multicarriers in semimetal bismuth. Phys. Rev. B 93, 174428 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yue D., Lin W., Li J., Jin X., Chien C. L., Spin-to-charge conversion in Bi films and Bi/Ag bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 037201 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangiao S., et al. , Control of the spin to charge conversion using the inverse Rashba-Edelstein effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 172403 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sangiao S., et al. , Optimization of YIG/Bi stacks for spin-to-charge conversion and influence of aging. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 54, 375305 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou D., et al. , Interface induced inverse spin Hall effect in bismuth/permalloy bilayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 042403 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sánchez J. C. R., et al. , Spin-to-charge conversion using Rashba coupling at the interface between non-magnetic materials. Nat. Commun. 4, 2944 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirahara T., et al. , Role of quantum and surface-state effects in the bulk fermi-level position of ultrathin Bi films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 106803 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y., Yang Y., Yao K., Xu B., Wu Y., Self-current induced spin-orbit torque in FeMn/Pt multilayers. Sci. Rep. 6, 26180 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W., et al. , Anomalous spin–orbit torques in magnetic single-layer films. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 819–824 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim K.-W., Lee K.-J., Generalized spin drift-diffusion formalism in the presence of spin-orbit interaction of ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 207205 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ochoa H., Zarzuela R., Tserkovnyak Y., Self-induced spin-orbit torques in metallic ferromagnets. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 538, 168262 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoki M., et al. , Anomalous sign inversion of spin-orbit torque in ferromagnetic/nonmagnetic bilayer systems due to self-induced spin-orbit torque. Phys. Rev. B 106, 174418 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong X.-X., et al. , Possible p-wave superconductivity in epitaxial Bi/Ni bilayers. Chinese Phys. Lett. 32, 067402 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tulapurkar A. A., et al. , Spin-torque diode effect in magnetic tunnel junctions. Nature 438, 339–342 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kittel C., On the theory of ferromagnetic resonance absorption. Phys. Rev. 73, 155–161 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nembach H. T., et al. , Perpendicular ferromagnetic resonance measurements of damping and Landé g−factor in sputtered (Co2Mn)1−xGex thin films. Phys. Rev. B 84, 054424 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ganguly A., et al. , Thickness dependence of spin torque ferromagnetic resonance in Co75Fe25/Pt bilayer films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 072405 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miao B. F., Huang S. Y., Qu D., Chien C. L., Inverse spin hall effect in a ferromagnetic metal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 066602 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsukahara A., et al. , Self-induced inverse spin Hall effect in permalloy at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 89, 235317 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du C., Wang H., Yang F., Hammel P. C., Systematic variation of spin-orbit coupling with d-orbital filling: Large inverse spin Hall effect in 3d transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 90, 140407(R) (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seki T., et al. , Observation of inverse spin Hall effect in ferromagnetic FePt alloys using spin Seebeck effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 092401 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Omori Y., et al. , Relation between spin Hall effect and anomalous Hall effect in 3d ferromagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014403 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leiva L., et al. , Giant spin Hall angle in the Heusler alloy Weyl ferromagnet Co2MnGa. Phys. Rev. B 103, L041114 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao S., Wei D., Jin X., Bi(111) thin film with insulating interior but metallic surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 166805 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu J., Li Y., Hou D., Ye L., Jin X., Enhancement of the anomalous Hall effect in Ni thin films by artificial interface modification. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 162401 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim J., et al. , Layer thickness dependence of the current-induced effective field vector in Ta|CoFeB|MgO. Nat. Mater. 12, 240–245 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garello K., et al. , Symmetry and magnitude of spin–orbit torques in ferromagnetic heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 587–593 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayashi M., Kim J., Yamanouchi M., Ohno H., Quantitative characterization of the spin-orbit torque using harmonic Hall voltage measurements. Phys. Rev. B 89, 144425 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avci C. O., et al. , Interplay of spin-orbit torque and thermoelectric effects in ferromagnet/normal-metal bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 90, 224427 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chi Z., et al. , The spin Hall effect of Bi-Sb alloys driven by thermally excited Dirac-like electrons. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2324 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pai C.-F., Ou Y., Vilela-Leão L. H., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Dependence of the efficiency of spin Hall torque on the transparency of Pt/ferromagnetic layer interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064426 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y., Allen R. E., Electronic structure of the semimetals Bi and Sb. Phys. Rev. B 52, 1566–1577 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koroteev Yu. M., Bihlmayer G., Chulkov E. V., Blügel S., First-principles investigation of structural and electronic properties of ultrathin Bi films. Phys. Rev. B 77, 045428 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 65.te Velde G., Baerends E. J., Precise density-functional method for periodic structures. Phys. Rev. B 44, 7888–7903 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.BAND 2021.1 (SCM, Theoretical Chemistry, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands: ), https://www.scm.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang W., et al. , Giant facet-dependent spin-orbit torque and spin Hall conductivity in the triangular antiferromagnet IrMn3. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600759 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bitzek E., Koskinen P., Gähler F., Moseler M., Gumbsch P., Structural relaxation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170201 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.