Significance

The combined radical and nonradical reactions induced by peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation can promise deep mineralization and selective removal of micropollutants from complex wastewater. However, nonhomogeneous metal-based catalysts with single active sites lead to a low efficiency of electron cycling for both radical and nonradical generation. In this study, asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites were constructed to achieve rapid electron cycling while achieving site synergy, thus effectively activating PMS to generate radicals and nonradicals. The presence of asymmetric sites can tune and optimize the catalytic performance through structural modulation, which can effectively remove and mineralize micropollutants from organic and inorganic compounds under the environmental background.

Keywords: Asymmetric Co-O-Bi sites, Electron transfer, PMS activation, Radical and nonradical reactions, Micropollutants

Abstract

The peroxymonosulfate (PMS)-triggered radical and nonradical active species can synergistically guarantee selectively removing micropollutants in complex wastewater; however, realizing this on heterogeneous metal-based catalysts with single active sites remains challenging due to insufficient electron cycle. Herein, we design asymmetric Co–O–Bi triple-atom sites in Co-doped Bi2O2CO3 to facilitate PMS oxidation and reduction simultaneously by enhancing the electron transfer between the active sites. We propose that the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites result in an electron density increase in the Bi sites and decrease in the Co sites, thereby PMS undergoes a reduction reaction to generate SO4•- and •OH at the Bi site and an oxidation reaction to generate 1O2 at the Co site. We suggest that the synergistic effect of SO4•-, •OH, and 1O2 enables efficient removal and mineralization of micropollutants without interference from organic and inorganic compounds under the environmental background. As a result, the Co-doped Bi2O2CO3 achieves almost 99.3% sulfamethoxazole degradation in 3 min with a k-value as high as 82.95 min−1 M−1, which is superior to the existing catalysts reported so far. This work provides a structural regulation of the active sites approach to control the catalytic function, which will guide the rational design of Fenton-like catalysts.

Micropollutants (MPs, such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and pesticides), exposure to these chemicals present in amounts (ng/L to μg/L) above the natural background levels in water bodies, pose a high risk to both ecological security and clean water supply (1, 2). Advanced oxidation process (AOP) based on peroxymonosulfate (PMS) is a promising water treatment technology for MP decontamination (3, 4). PMS with asymmetric structure (H–O–O–SO3-) can serve as an electron acceptor and an electron donor to generate free radicals [especially, sulfate radicals (SO4•-), hydroxyl radical (•OH)], and nonfree radical [especially, singlet oxygen (1O2)] (5). It is well-known that SO4•- (E0 = 2.5 to 3.1 VNHE) and •OH (E0 = 1.9 to 2.7 VNHE) have a high redox potential and a wide pH range for efficient mineralization of MPs; however, they also exhibit poor selectivity and suffer from radical recombination or scavenging by PMS and background ions (6, 7). While for 1O2, it can selectively degrade MPs under environmental interference, but is still restricted by insufficient oxidation capacity (8, 9). Therefore, the combination of free and nonfree radicals will be superior to single active species for the rapid removal and deep mineralization of MPs in both pure water and complex actual wastewater.

In order to promote heterogeneous PMS activation with simultaneous generation of free and nonfree radicals, several efficient strategies have been used, such as single-atom modifications (10–12) and heterojunction engineering (13–15). Single-atom catalysts present many unique advantages, such as homogeneous active site structure, maximum metal atom utilization efficiency, uniquely high activity, and the ability to bridge homogeneous and multiphase. It is generally involved in four steps: PMS adsorbed on low-valence metal sites (Mn), the subsequent PMS reduction reactions to generate SO4•- and •OH (Eqs. 1 and 2), PMS readsorbed on high-valence metal sites (Mn+1), and eventually PMS oxidation reactions to generate 1O2 (Eqs. 3 and 4) (8, 16). For example, Gao et al. (17) constructed Fe single-atom (FeSA–N–C) catalysts for PMS activation, which is faster in removing BPA by both free radical and nonfree radical pathways under the background ion interference. However, these catalysts usually depend on a single metal site to generate radicals and nonradicals sequentially, which results in a slow electron cycling efficiency of radical and nonradical generation. If it is possible to construct separate dual sites for PMS oxidation and reduction on the catalyst surface, it will greatly improve the efficiency of activated PMS to generate free radicals and nonfree radicals.

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

| [4] |

Recently, asymmetric sites have been put forward to endow the two metal sites with different charge distributions, thus constructing dual reactive centers (18–20). In metal oxides (MxOy), for example, the oxygen atoms usually have high symmetric coordination with the cations (M–O–M), and a simple way to break the high symmetry of oxygen is to substitute one of the cations coordinated to the O atom, forming an asymmetric triple-atomic site (M1–O–M2) (21). In these asymmetric sites, the intermediate oxygen atom can act as a bridge for rapid electron transfer between metal M1 and metal M2 (22, 23). Differences in metal valence or electronegativity lead to asymmetric electron distribution in the triatomic sites, creating electron-poor and electron-rich centers. For example, Zhu et al. (19) fabricated triple-atom Zn–O–Ge sites confined in Zn2GeO4 nanosheets, and the asymmetric electron distribution on the triple-atom Zn–O–Ge sites causes distinct electron differences on the adsorbed CO* intermediates, thus obtaining a considerable CO2-to-CH3COOH conversion ratio. Therefore, we speculate that the asymmetric M1–O–M2 sites can achieve rapid electron cycling while realizing sites’ synergy, thus satisfying the requirement for efficient PMS activation to generate radicals and nonradicals.

Here, inspired by the above considerations, we first constructed asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites on atomically thin two-dimensional Co-doped Bi2O2CO3 (Co-BOC) nanosheets for efficient PMS activation. In situ characterization techniques and theoretical calculations indicate that the Co doping induces an asymmetry of charge distribution in the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites, resulting in the highly efficient electronic cycle. During the reaction, the electron from PMS at the Co site can be transferred to the adsorbed PMS at the Bi site via the Co–O–Bi bridge, thus enabling the simultaneous rapid oxidation and reduction of PMS to generate free radicals (SO4•- and •OH) and nonfree radicals (1O2), respectively. We experimentally determined that the mineralization of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) was achieved by the synergistic interaction of SO4•-, •OH, and 1O2, and SMX can be decomposed almost 100% in 3 min with a k-value as high as 82.95 min−1 M−1, which is superior to the existing catalysts reported so far.

Results and Discussion

Structure and Morphology of Co-BOC.

The single-unit-cell Co-doped Bi2O2CO3 was synthesized by a hydrothermal method using CoCl2·6H2O, BiCl3, CTAB, and HMT as precursors (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Control samples including pristine Bi2O2CO3 (denoted as BOC) and different Co-doping amounts were also prepared as references, and four representative doping concentrations were selected: 0.2, 0.6, 1, and 2% (where the percentage was defined as the relative atomic mass of Co:Bi). Among all the samples, the Co-doped Bi2O2CO3 with 1% Co doping was selected as a typical sample in this study due to the best performance (denoted as Co-BOC).

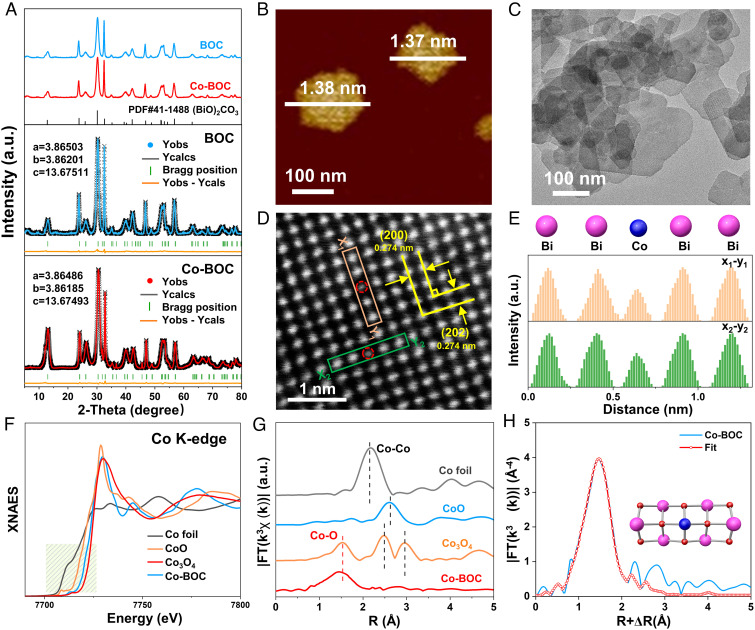

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns shown in Fig. 1A indicate that the prepared BOC and Co-BOC have good crystallinity assigned to orthorhombic Bi2O2CO3 (JCPDS card number: 41-1488) (24). Additionally, the Rietveld refinement analysis reveals that Co-BOC possesses a structure with a space group of Imm2 and lattice parameters of a = 3.8649 Å and c = 13.6749 Å, indicating that the crystallinity does not change significantly after Co doping (SI Appendix, Table S1) (25). The successful synthesis of the target samples was further supported by Raman and FT-IR spectra (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3), and the two-dimensional ultrathin nanosheet morphology of BOC and Co-BOC was confirmed by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with an average thickness of ~1.37 nm (Fig. 1 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S6). Fast Fourier transform (FFT)-selective area electron diffraction (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B) and high-angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images (Fig. 1D) reveal the high orientation along the [010] projection of Co-BOC (26). Elemental mapping (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D) by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) reveals the presence and uniform distribution of Co, Bi, C, and O on Co-BOC. The aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image further clearly shows the uniform dispersion of Bi atoms on the Co-BOC, where the weak intensity spots in the red ring correspond to Co atoms (27). And the line intensity profile analysis further shows that isolated Co atoms substitute for Bi atoms in the lattice (Fig. 1E), implying the construction of asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites (28).

Fig. 1.

Structural characterizations of Co-BOC. (A) XRD and refined XRD patterns of BOC and Co-BOC. (B) AFM and (C) TEM images of Co-BOC. (D) Atomic-scale HAADF-STEM image of Co-BOC and (E) the line scan measured along the x–y rectangle regions. (F) XANES spectra at the Co K-edge, (G) FT k3-weighted EXAFS spectra of Co-BOC and references, and (H) fit of the corresponding FT-EXAFS spectra for Co-BOC in R space.

To further reveal the successful construction of asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites, we conducted X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and synchrotron radiation-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy analysis. XPS survey spectrum confirms the existence of C, O, Bi, and Co elements in Co-BOC (SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8) (14, 24, 29). The high-resolution XPS spectra of Co 2p exhibit peaks at 779.8 and 781.2 eV, corresponding to Co3+ and Co2+ (14), respectively, implying that Co may be substituting for Bi in the lattice (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). To further elucidate the valence state and coordination environment of Co atoms, X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) was applied. The Co K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra of the Co-BOC and the reference compounds show that the position of the absorption edge (line position) of the Co atoms is located between CoO and Co3O4, demonstrating that the valence states of the Co species are between +2 and +3 in Co-BOC (Fig. 1F) (30). Furthermore, the Fourier transform (FT) extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of Co-BOC and reference samples show that only a prominent peak corresponding to the Co–O coordination at 1.53 Å for Co-BOC, and no Co–Co peak at 2.18 Å or larger bond distance is detected (31, 32), confirming the absence of Co or CoO clusters or particles in Co-BOC (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The Co K-edge wavelet transform (WT)-EXAFS was also applied which reveals that only a maximum intensity at 3.8 Å attributed to the Co–O shell in BOC (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) (33), further confirming the dispersed existence of Co species in Co-BOC. The quantitative structural parameters of the Co atom were further surveyed using quantitative least-squares EXAFS curve fitting (Fig. 1E). The best-fitting analysis displays that the first shell of the central atom Co is assigned a coordination number of 4.1, directly connected to four O atoms, with mean bond lengths of 1.89 Å (Fig. 1H and SI Appendix, Table S3). This result confirms that the Co species are substituting the Bi atom in the lattice, thus successfully constructing the asymmetric Co–O–Bi site, in agreement with the HAADF-STEM results.

Catalytic Performance for MP Degradation in the Co-BOC/PMS System

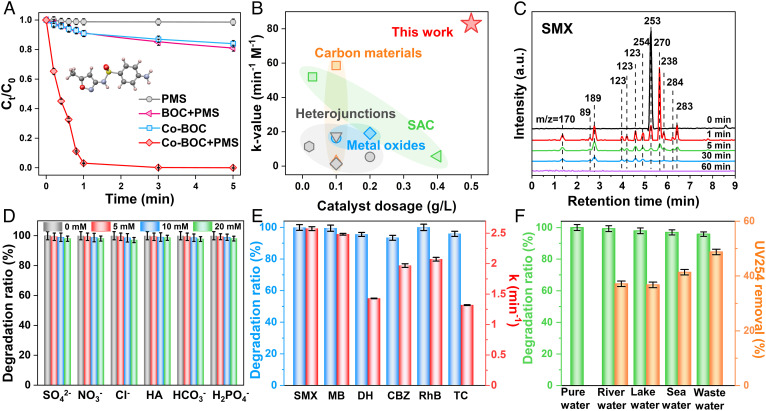

The catalytic performance of Co-BOC by activating PMS was then evaluated using sulfamethoxazole (SMX), a typical broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent (physicochemical properties of SMX are shown in SI Appendix, Table S4), as a target pollutant, and the optimal amounts of Co-BOC and PMS were fixed at 0.6 g L−1 and 1 mM, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Without any catalysts, the PMS can only result in 0.7% SMX removal in 5 min. And before the addition of PMS, the removal of SMX owing to the adsorption by Co-BOC is also negligible (16.7%). Notably, the degradation efficiency of the Co-BOC/PMS system reaches 99.3%, while the BOC exhibits only 18.7% SMX degradation within 3 min, which indicates the superiority of PMS activation on the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites compared to symmetric Bi–O–Bi sites (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). More importantly, the Co-BOC is robust and recyclable with a steady degradation efficiency, and the leakage of Co ions during the cycle (<0.16 mg L−1) is far below the discharge standard (GB 25467–2010 and USEPA’s secondary drinking water standard, 1 mg L−1), indicating that the Co–O–Bi site has excellent stability performance and can suppress the leaching of metal species (SI Appendix, Figs. S14–S17 and Table S5). Remarkably, the Co-BOC catalyst with asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites degrades SMX with a k-value of 82.95 min−1 M−1 (34), showing the best catalytic performance among all the recently reported catalysts (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Table S6). Fig. 2C shows the chromatograms of 10 ppm SMX solution at different degradation times. The m/z = 253 peak with a retention time of 5.3 min is associated with SMX, decays with increasing degradation time, and finally disappears after 3 min. And all peaks disappear after 90 min, indicating that SMX and the intermediate product are finally mineralized to CO2 and H2O (35).

Fig. 2.

Catalytic performance of the Co-BOC. (A) SMX removal by various systems. (B) Comparison of k-values for SMX removal with state-of-the-art materials. (C) LC-MS chromatograms of SMX and its degradation intermediates in reaction solutions at different degradation time intervals. (D) Effect of background ions, (E) removal of multiple pollutants, and (F) the degradation rate of SMX in different water bodies by Co-BOC/PMS system. Reaction conditions: [SMX] = [MB] = [DH] = [CBZ] = [RhB] = [TC] = 10 mg L−1; [catalyst] = 0.6 g L−1; [PMS] = 1 mM; [Temp] = 20 °C; initial pH = 6.7.

It was reported that inorganic anions in natural water could rapidly react with free radicals through electron exchange and change the acid–base conditions of the reaction solution, thus affecting the degradation efficiency of the target contaminants (7, 36, 37). As shown in Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S18, the addition of SO42−, NO3−, Cl−, humic acid (HA), HCO3−, and H2PO4− has no noticeable effect on SMX removal efficiency (36), indicating that the Co-BOC/PMS system with •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2 can effectively resist the interference of background ions. In addition, the effects of reaction temperature and pH on degradation further indicate that the contaminant degradation is achieved through intrinsic chemical reactions and that the Co-BOC/PMS system can tolerate a wide pH range (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). Apart from SMX, Co-BOC/PMS system can also efficiently oxidize a variety of refractory pollutants in wastewater, including carbamazepine (CBZ), methylene blue (MB), rhodamine (RhB), tetracycline (TC), and doxycycline hydrochloride (DH) (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Table S7), suggesting that the free radical and nonfree radical synergistic Fenton-like system is broadly adaptable.

To further check the potential practical application of Co-BOC, we sampled real water matrices (the main compositions are displayed in SI Appendix, Table S8), and the degradation rate of SMX and the removal rate of UV254 were used as indicators (38). As shown in Fig. 2F, impressively, the removal of SMX in river and lake water (98.9% and 97.2%, respectively) is comparable to that in pure water. Despite the high Cl- concentration (6947 mg L−1) in seawater, the removal of SMX and UV254 is still 96.5% and 43.8%, respectively, showing the advantages of combining free radicals and nonfree radicals. Wastewater samples (TOC: 1,273 mg L−1, Cl-: 3,276 mg L−1) from the Jinnan wastewater treatment plant (Tianjin, China) are more complex, and the removal of SMX and UV254 within 3 min is still as high as 90.8% and 48.8%, respectively. All the results above demonstrate the enormous potential of Co-BOC with asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites for practical environmental remediation.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Their Contribution to MP Degradation

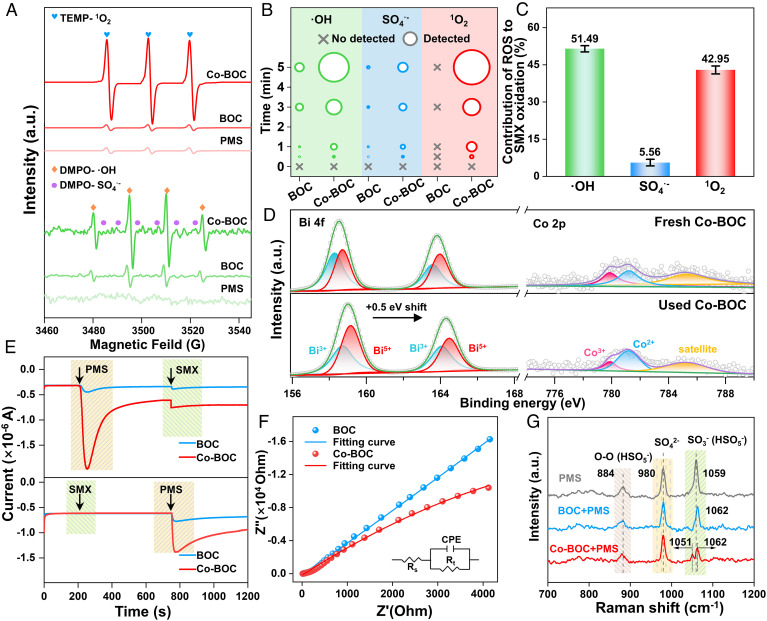

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technology was subsequently used to detect the generated ROS in the Co-BOC/PMS system. To determine whether singlet oxygen (1O2) is generated, we used 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinol (TEMP) as a spin-trapping agent (39). As shown in Fig. 3A, the 1:1:1 triplet signal of TEMP-1O2 is observed weakly in the BOC/PMS system, and the signal intensity is basically consistent with that of the PMS system, which rules out the possibility that the BOC itself activates the PMS to generate 1O2. In the Co-BOC/PMS system, the characteristic peaks of TEMP-1O2 increase significantly, indicating that Co-BOC can activate PMS to generate a considerable amount of 1O2. The possibility of transfer of other ROS to 1O2 was further eliminated by the addition of the corresponding bursting agents (SI Appendix, Figs. S20 and S21A). These results reveal that the construction of the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites strongly accelerates the formation of 1O2. To further investigate the free radicals in the system, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) was used as a spin-trapping agent for O2•-, SO4•-, and •OH (3). In the three systems (PMS, BOC/PMS, and Co-BOC/PMS systems), there is no significant difference in DEMP-O2•- signal intensity, ruling out the presence of O2•- (SI Appendix, Fig. S21B). On the contrary, the characteristic peaks of DMPO-SO4•- and DMPO-•OH are detected in the BOC/PMS and Co-BOC/PMS systems, indicating that both samples are able to activate PMS to generate SO4•- and •OH. However, the characteristic peak intensity of the Co-BOC/PMS system containing Bi–O–Co sites is significantly stronger than that of the BOC/PMS system. The above results further demonstrate that the Co-BOC/PMS system can rapidly remove contaminations compared to the BOC/PMS system because the asymmetric Co–O–Bi site not only generates 1O2 but also accelerates the generation efficiency of the SO4•- and •OH by establishing a fast electron cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S22). In addition, the results of EPR measurement were further validated by quantitative experiments (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S23) and scavenger quenching tests (SI Appendix, Fig. S24). Methanol (MeOH), tert-butanol (TBA), and L-histidine were used as quenchers of SO4•-, •OH, and 1O2, respectively (8, 40). Further, the contribution of free radicals was quantified (Fig. 3C), where the contributions of •OH (λ(•OH)), SO4•- (λ(SO4•-)), and 1O2 (λ(1O2)) are 51.5%, 5.6%, and 42.9%, respectively. The same results from EPR measurement and scavenger quenching experiments indicate that •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2 jointly facilitate the degradation of SMX in complex water bodies.

Fig. 3.

Identification of active species and their contribution. (A) EPR spectra for 1O2 in the presence of TEMP and •OH/SO4•- in the presence of DMPO in various systems. (B) Quantitative analyses of •OH/SO4•- and 1O2 present in Co-BOC/PMS system. (C) Contribution of ROS to SMX oxidation over the Co-BOC with PMS; XPS spectra of (D) Bi 4f and Co 2p before and after reaction in Co-BOC. (E) Amperometric i-t curve measurements upon the addition of PMS and SMX using Co-BOC as the working electrode. (F) EIS spectra of different samples. (G) In-situ Raman spectra of different reaction conditions.

To investigate the PMS activation mechanism, XPS was used to analyze the valence changes of Bi and Co in fresh and used Co-BOC (Fig. 3D). In the high-resolution XPS Bi 4f spectra of Co-BOC, the two peaks at 163.8 and 158.5 eV are assigned to the binding energies of Bi 4f5/2 and Bi 4f7/2, respectively. Furthermore, a careful deconvolution of the Bi 4f spectrum of Co-BOC reveals that the Bi species in Co-BOC are Bi3+ and Bi5+. After the reaction with PMS, the two peaks of Bi 4f shift 0.5 eV toward the higher binding energy and the Bi3+/Bi5+ content is slightly lower, which indicates the increase of the Bi oxidation state due to the electron loss during the reaction, confirming the reduction reaction of PMS at the Bi site on Co-BOC (SI Appendix, Table S9) (41). Meanwhile, a careful deconvolution of the XPS spectra of Co 2p can identify the presence of Co in Co-BOC in the form of Co2+ and Co3+. After reacting with PMS, the content of Co3+ in Co-BOC decreases, while the content of Co2+ increases, demonstrating that Co may have obtained electrons in the reaction process (42). According to the ROS in the system and the change of elemental valence before and after the reaction, we conclude that PMS undergoes oxidation reactions at the Co site and reduction reactions at the Bi site to generate •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2 (15).

To further reveal the electron transfer pathway, amperometric i-t curves were recorded in Fig. 3E (43). After adding PMS, the current density of Co-BOC decreases significantly, which may be attributed to the electron redistribution caused by the binding between the PMS and asymmetric sites. In contrast, when SMX was initially added to the electrochemical system, no electron transfer between SMX and the catalyst occurs. These observations demonstrate the generation of “substable PMS/Co-BOC surface complexes.” Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and Tafel polarization curves show that the resistance of Co-BOC is lower than that of BOC (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Fig. S25) (44), which further confirms that the asymmetric Co–O–Bi site increases the electron transfer efficiency. In-situ Raman and ATR-FTIR measurements were carried out to distinguish further the PMS action sites on the catalyst surface (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S26) (45). In-situ Raman measurement detects that the intensity of the SO3− (HSO5−) vibrational peak (1,059 cm−1) and the intensity of the O–O peak (884 cm−1) decrease after the addition of Co-BOC, indicating the decomposition of PMS. After interaction with PMS, O–O and SO42− peaks appear in the Raman spectra of Co-BOC/PMS, indicating that PMS is adsorbed on Co-BOC (46). It is noteworthy that in the Co-BOC/PMS system, the SO3− (HSO5−) peak splits into two small peaks located at 1,051 cm−1 and 1,062 cm−1. And the characteristic vibrational peaks of the SO3− (HSO5−) appear both red shifted (1,051 cm−1) and blue shifted (1,062 cm−1), suggesting that electron transfer occurs between the asymmetric sites and the PMS as well as the orientation may be different (47–49). Combined with XPS analysis, it can be concluded that the red shift and blue shift come from PMS gaining electrons from the Bi site and losing electrons at the Co site, respectively. The same experimental phenomena observed in the in-situ FTIR spectra also confirm the above finding (SI Appendix, Fig. S25).

Electron Cycle Process on the Asymmetric Co–O–Bi Site

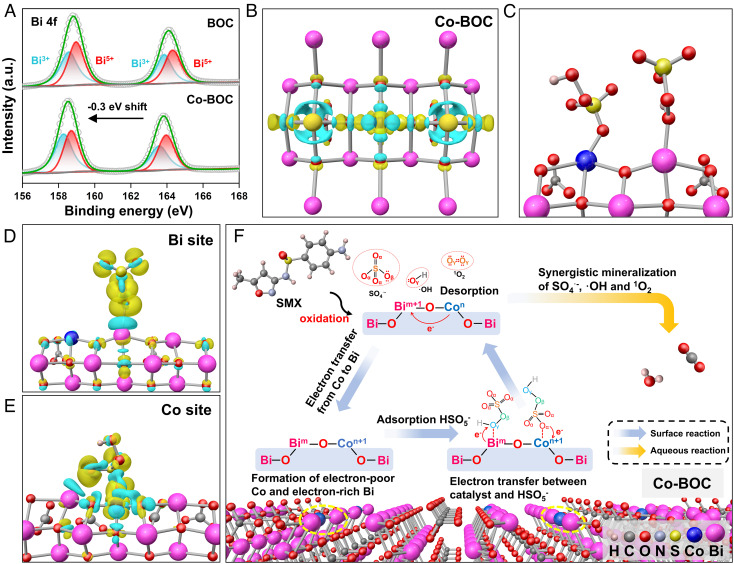

To figure out the effect of Co doping for electron distribution on BOC, XPS spectra before and after doping were analyzed. As shown in Fig. 4A, compared to the BOC, the XPS spectra of Bi 4f shift 0.3 eV toward the lower binding energy after Co doping, indicating that Co doping increases the electron density of the Bi sites (28). To further confirm this conclusion, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to shed light on the electron distribution on the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites. First, the charge density differences (CDDs) of Co-BOC reveal the asymmetric distribution of electrons on Bi and Co atoms, which indicates that the Co doping causes a redistribution of charge, i.e., electron donation from Co to Bi atoms, in agreement with our experimental results (Fig. 4B) (50). After deciphering the distribution of electrons on the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites, the optimized adsorption conformations of PMS on Co-BOC reveal that the Co and Bi sites can adsorb two PMS molecules simultaneously in the form of end-on (Fig. 4C). Notably, the locations where PMS is adsorbed are different, with the Bi site and the Co site adsorbing the hydrogen O atom and terminal O atom of PMS, respectively. Furthermore, the CDD of the Co-BOC with adsorbed PMS further demonstrates that the adsorbed PMS molecules are more likely to gain electrons in the electron-rich Bi sites to generate SO4•- and •OH and lose electrons in the electron-poor Co sites to generate 1O2 (Fig. 4 D and E), which is consistent with the experimental conclusions (17, 51).

Fig. 4.

Proposed mechanism of asymmetric Co–O–Bi site on PMS activation. (A) XPS spectra of Bi 4f before and after co doping. (B) Top view of the charge distribution in Co-BOC. (C) Optimized adsorption conformation of PMS at Bi and Co sites on Co-BOC. Charge density difference induced by PMS on Bi site (D) and Co site (E). Yellow and cyan regions represent the electron accumulation and the electron depletion, respectively. (F) Proposed mechanism for the SMX oxidative catalyzed by Co-BOC.

From the above results, the reaction mechanism is proposed in Fig. 4F, and we found that the construction of asymmetric Bi–O–Co sites is the origin of the high activity of Co-BOC. After Co doping, charge redistribution through Bi–O–Co sites promotes the feedback of electrons from Co to Bi, which not only provides electron-rich Bi active sites, but also creates electron-poor Co catalytic sites. Specifically, the construction of asymmetric site can increase the charge density of individual Bi atoms and promotes the reduction of PMS to form more SO4•- and •OH. On the contrary, the electron-poor Co sites make it possible for PMS to be oxidized to 1O2. Therefore, the efficient redox of PMS can be achieved through the electron cycle between the Co and Bi sites on the asymmetric Co–O–Bi site, realizing the efficient removal of micropollutants from the actual water through the synergistic effect of free radicals (SO4•- and •OH) and nonfree radicals (1O2).

Free Radical and Nonfree Radical Synergistic Degradation Pathways

Active sites of SMX molecules can be predicted by DFT calculations, which can give assistance to explore the degradation of organic pollutants from the electronic structure perspective (42). First, the orbital-weighted Fukui functions f0 and f- were applied to analyze the SMX molecule (SI Appendix, Fig. S27). The Fukui index analysis reveals that 11(N), which exhibits the highest f0 value, is the most active site of radical (SO4•- and •OH) attack in the SMX molecule, followed by 23(N), 2(C), and 5(C). Interestingly, 11(N), which possesses the highest f- value, is also the active site of electrophilic (1O2) attack, followed by 1(C), 5(C), and 17(N) (SI Appendix, Table S10). Thus, 11(N) presents the highest f0 and f- values, indicating that it has the most vulnerable site in the degradation process (52). In addition, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) were also investigated, as they represented the electron-donating and -accepting capacity, respectively (42). As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S27 E and F, the N atom and the aniline ring, as well as the S–N bond, are the most likely to be oxidized.

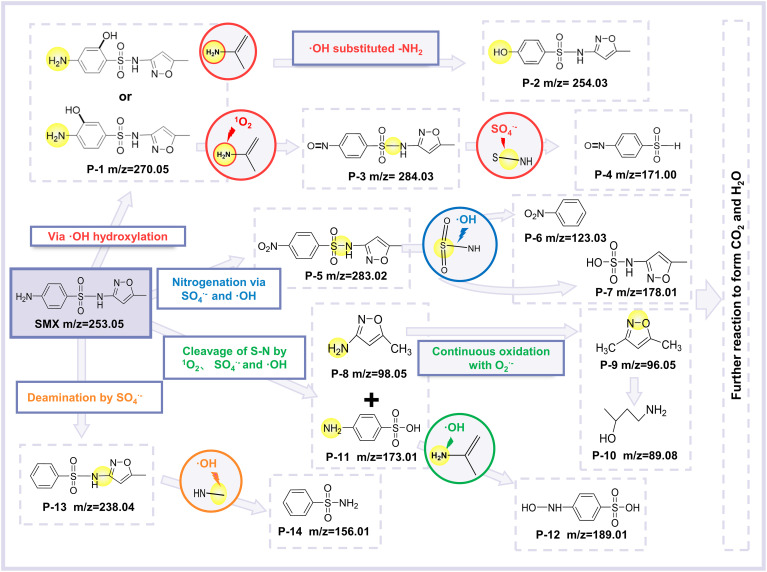

The intermediates after SMX oxidation in the Co-BOC/PMS system were determined by LC-MS analysis (SI Appendix, Table S11). Combined with the electronic structure analysis of SMX molecules from DFT calculations, a possible degradation pathway of SMX in Co-BOC/PMS systems was proposed (Fig. 5). To start with, SMX is prone to hydroxylation reactions due to the presence of •OH, and the resulting product P-1 is generated. Based on the calculation of the orbital weighted Fukui function of SMX, the •NH2 in P-1 readily underwent substitution reaction with •OH and oxidation reaction with 1O2 to form products P-2 and P-3, respectively. In another pathway, the aniline group in SMX is oxidized by SO4•- and •OH to form the product P-5 (52). The sulfonamide bond in sulfonamide antibiotics is easily broken by 1O2, SO4•-, and •OH attacks in SMX. As a result, the S–N bonds in P-3, P-5, and SMX are broken by single or synergistic attacks of SO4•-, •OH, and 1O2, respectively. In this, the products P-8 and P-11 are generated from the S–N bond break in SMX. Subsequently, P-8 is continuously oxidized to products P-9 and P-10, eventually being mineralized, while •NH2 in P-11 is replaced by •OH to produce P-12. Besides, the aniline group in SMX, in addition to being easily oxidized, is also attacked by SO4•- to be deaminated, resulting in the product P-13 (53). Ultimately, SMX is finally completely mineralized to CO2 and H2O via the synergistic effect of •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2, consistent with the results obtained from TOC (SI Appendix, Fig. S28) and LC-MS measurements (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 5.

Proposed free radical and nonfree radical synergistic degradation pathways of SMX.

Besides, it was essential to consider the toxicity of SMX and degradation intermediates in the pollutant removal process. The ecological structure activity relationship (ECOSAR) program was used to predict the acute (short term) and chronic (long term or delayed) toxicity of SMX and its TPs (SI Appendix, Fig. S29 and Tables S12 and S13) (54). After the synergistic action of free and nonfree radicals, SMX molecules are broken down into small molecules and finally mineralized. Thus, the toxicity of SMX is greatly reduced after treatment in the Co-BOC/PMS system.

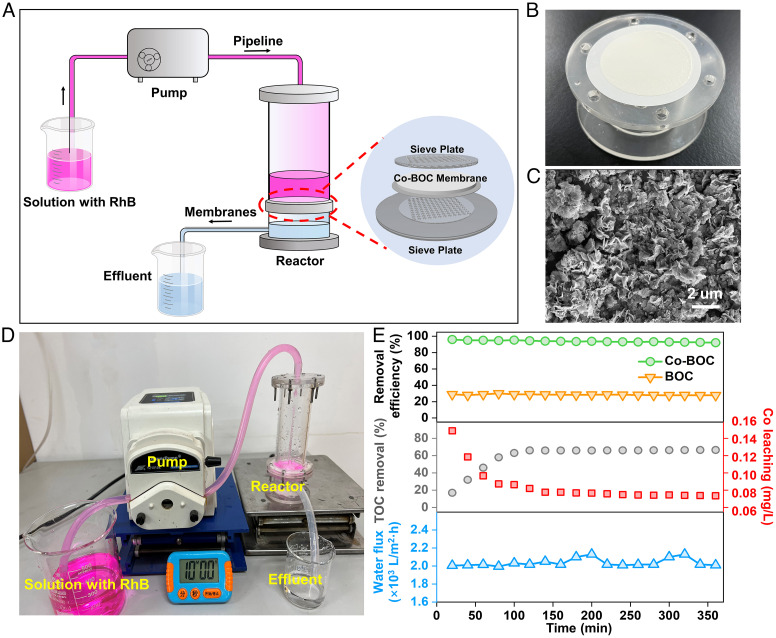

Investigation of the Organic Wastewater Treatment System

To evaluate the potential utility of Co-BOC, a continuous flow reactor consisting of Co-BOC membranes was used to treat the long-term degradation of pollutants, and the schematic diagram of the device is shown in Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S30 (47). Co-BOC membranes were made of PVDF liner vacuum-assisted filtration of Co-BOC catalyst suspensions with flexible elasticity, and SEM shows the random accumulation of Co-BOC nanosheets without obvious cracks (Fig. 6 B and C) (33, 55). To visualize the effect of the catalyst on the degradation rate, RhB was used instead of SMX. After PMS was added to the solution, the effluent from the reactor becomes colorless, suggesting that RhB is efficiently removed by the Co-BOC membrane (Fig. 6D) (1, 33). To evaluate the effectiveness of the reactor in removing micropollutants from the actual wastewater, SMX from the secondary effluent of the Jinnan Wastewater Treatment Plant (Tianjin, China) was treated with Co-BOC membranes. As shown in Fig. 6E, the removal efficiency of SMX was maintained above 95% and the TOC removal rate was over 60% in the continuous operation of SMX solution at a flow rate of 2,000 L (m2 h)−1 for 360 min, reflecting the good catalytic activity and durability of Co-BOC.

Fig. 6.

Applications in water treatment of the Co-BOC/PMS system. (A) Schematic diagram of the continuous-flow reactor. (B) Image of the catalyst-loaded membrane. (C) SEM images of membrane surfaces. (D) Photograph of experiment device (RhB as indicator pollutant); (E) SMX removal performance of wastewater treatment equipment with Co catalyst, TOC removal rate and Co ion concentration, and water flow rate in the device in the effluent with filtration time.

Conclusions

In summary, we first designed an asymmetric Co–O–Bi site on Co-BOC catalyst by a simple one-step solvothermal method, which shows excellent performance in activating PMS for efficient and stable MPS removal. Based on the chemical state analysis, In situ characterization results, and DFT calculations, the Co doping induces an asymmetry of charge distribution in the asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites, resulting in an electron density increase in the Bi sites and decrease in the Co sites. Chemical capture experiments and EPR measurements confirm that the ROS that play a role in the Co-BOC/PMS system are SO4•-, •OH, and 1O2. Analyzing the elemental valence changes before and after the reaction, we can confirm that PMS undergoes a reduction reaction to generate SO4•-, and •OH at the Bi site and an oxidation reaction to generate 1O2 at the Co site. As a result, the synergistic degradation of SO4•-, •OH, and 1O2 enables efficient removal and mineralization of pollutants without interference from organic and inorganic compounds under the environmental background. Ultimately, the SMX degradation experiments show that the construction of asymmetric Co–O–Bi sites significantly improves the catalyst activity, in which 10 ppm SMX can decompose almost 100% within 3 min with a k-value of up to 82.95 min−1 M−1, making it superior to the existing catalysts reported so far. Our work provides precious guidance for free radical and nonfree radical synergistic degradation and the practical application of Fenton-like catalysts.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

All chemical reagents were of analytical grade and used without further treatment. Cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2·6H2O), anhydrous ethanol (EtOH), hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), methenamine (HMT), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), bismuth chloride (BiCl3), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), carbamazepine (CBZ), methylene blue (MB), rhodamine (RhB), tetracycline (TC), doxycycline hydrochloride (DH), sodium chloride (NaCl), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4), humic acid (HA), methanol (MeOH), tert-butanol (TBA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), L-histidine, salicylic acid, p-Hydroxybenzoic acid (HBA), diphenylamine (DPA), potassium thiocyanate (KSCN), methanol (high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) ultra), deuterium oxide (D2O), nafion, potassium monopersulfate triple salt (KHSO5·0.5KHSO4·0.5K2SO4, ≥47%), 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO, 97%), and 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine (TEMP, ≥98%) were purchased from Aladdin Co., Ltd.

Preparation of Catalyst.

For the synthesis of Bi2O2CO3 (BOC), 300 mg CTAB was dissolved in the mixed solution of 35 mL ethanol and 2 mL DI. After vigorous stirring at 300 r min−1 for 10 min, 300 mg HMT was added to the above solution with continuous stirring. Next, 600 mg Na2CO3 and 1 g BiCl3 were dissolved and then stirred for another 1 h. The obtained mixed solution was introduced into a 50-mL Teflon autoclave and heated at 140 °C for 12 h. Finally, the final product was cooled down to room temperature, separated by centrifugation, and washed several times with DI and EtOH, followed by drying in a vacuum overnight. The white powder of Bi2O2CO3 was then obtained. The synthesis of the x% Co-doped Bi2O2CO3 (x% Co-BOC) catalysts was similar to that of Bi2O2CO3, except a certain amount of CoCl2·6H2O was also added (here x is the at.% of CoCl2·6H2O relative to BiCl3 and x = 0.2, 0.6, 1, and 2).

Characterizations.

The structure and morphology of the synthetic samples were examined with XRD powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/Max 2200PC X-ray diffractometer) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm). The morphology was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM 7800F), atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Atomic Force Microscope), HRTEM (JEOL JEM-ARM200F NEOARM), and HAADF-STEM-EDX (dual aberration correctors and four EDS detectors, each of which has an effective area of 30 mm2, were used to detect EDS signals). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was collected using the KBr method and the signal was recorded on an FT-IR spectrometer (Shimadzu). Raman spectra were collected on a RM1000 spectrometer with an Ar ion laser as excitation source. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on Thermal ESCALAB 250 electron spectrometer. The elemental content of the samples was determined through the ICP-MS (X7 Series, Thermo Electron Corporation). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR, Bruker A300 spectrometer) spectra were performed at room temperature. Amperometric i-t curve measurement was performed using the electrochemical workstation (CHI660B, Shanghai Chenhua). The attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) spectra data were obtained by NICOLET iS10. In-situ Raman spectra were tested with an HR Evolution Raman spectrophotometer (HORIBA Scientific Inc.).

Experimental Procedures and Analyses.

The organic degradation experiment was made in a 50-mL glass beaker with SMX solution (50 mL, 10 ppm), PMS (1 mM), and catalyst (0.03 g L−1). All experiments were performed in triplicate under aerobic conditions (298 ± 2 K) in a rotating shaker at 300 rpm. As the reaction proceeded, 1 mL of the reaction solution was extracted with a syringe at predetermined time intervals, immediately quenched with 50.0 μL Na2S2O3 (150.0 mM) and immediately filtered through a microporous filter (0.22 μm) for HPLC analysis. Degradation intermediates were analyzed by a UPLC-HRMS system equipped with a Waters C18 column (150 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm). The detergents were acetonitrile and water (both containing 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min−1. The solution was adjusted to the desired pH with 0.1 M H2SO4 or NaOH. The adsorption experiments were similar to the degradation experiments, but without the addition of PMS.

The leaching of cobalt ions from the Co-BOC catalyst was determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Avio200, PerkinElmer). The stability of Co-BOC was evaluated by cycling tests. At the end of each cycle, the catalyst was recovered by filtration, rinsed with ultrapure water, dried, and reused. The EPR assays for SO4•-/•OH and O2•- were performed in aqueous and methanolic media, respectively, using DMPO as the spin trapping agent. The single-linear state oxygen was detected by EPR spectroscopy in an aqueous solution with the spin trapping agent of TEMP.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Measurements.

The X-ray absorption fine structure spectra (Co K-edge) were collected at 1W1B station in Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF). The storage rings of BSRF were operated at 2.5 GeV with a maximum current of 250 mA. Using Si (111) double-crystal monochromator, the data collection was carried out in transmission mode using an ionization chamber. All spectra were collected in ambient conditions.

Calculation of Free Radical and Nonfree Radical Contribution Rates.

We quantitatively determined the contributions of •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2. The reaction rate constants after the addition of TBA, MeOH, and carotene were noted as k1, k2, and k3, respectively, and the initial reaction rate constant without quencher was k0. The contributions of •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2 were calculated according to Eqs. 5–7.

| [5] |

| [6] |

| [7] |

where λ(•OH), λ(SO4•-), and λ(1O2) were the contribution of •OH, SO4•-, and 1O2 to degradation of SMX, respectively.

Calculation Details.

Calculation Method. Spin-polarized first-principle calculations were performed by the density functional theory (DFT) using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP). The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional was used to describe the electronic exchange and correlation effect. Uniform G-centered k-point meshes with a resolution of 2π × 0.04 Å−1 and Methfessel–Paxton electronic smearing were adopted for the integration in the Brillouin zone for geometric optimization. The simulation was run with a cutoff energy of 500 eV throughout the computations. These settings ensure convergence of the total energies to within 1 meV per atom. Structure relaxation proceeded until all forces on atoms were less than 1 meV Å−1 and the total stress tensor was within 0.01 GPa of the target value.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the Natural Science Foundation of China as a Shandong joint fund project (grant No. U1906222) and general projects (grant Nos. 22225604, 22076082, 21874099, 22176140, 22006029, and 42277059), the Tianjin Commission of Science and Technology as key technologies R&D projects (grant Nos. 19YFZCSF00920, 19YFZCSF00740, 20YFZCSN01070, and 21YFSNSN00250), the Frontiers Science Center for New Organic Matter (grant No. 63181206), Haihe Laboratory of Sustainable Chemical Transformations, the Ministry of Science and Technology of People’s Republic of China as a key technology research and development program project (grant No. 2019YFC1804104).

Author contributions

Q.Z. and P.W. designed research; Q.Z. and C.S. performed research; Z.Z. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; C.S., Z.Z., Y.L., and S.Z. analyzed data; and Q.Z. and P.W. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All data of this study are included in the article and SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Guo Z. Y., et al. , Electron delocalization triggers nonradical Fenton-like catalysis over spinel oxides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2201607119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin L., You S., Ren N., Ding B., Liu Y., Mo vacancy-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate for ultrafast micropollutant removal using an electrified MXene filter functionalized with Fe single atoms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11750–11759 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang M., et al. , Facilely tuning the intrinsic catalytic sites of the spinel oxide for peroxymonosulfate activation: From fundamental investigation to pilot-scale demonstration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2202682119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y. J., et al. , Simultaneous nanocatalytic surface activation of pollutants and oxidants for highly efficient water decontamination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3005 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang P., Yang Y., Duan X., Liu Y., Wang S., Density functional theory calculations for insight into the heterocatalyst reactivity and mechanism in persulfate-based advanced oxidation reactions. ACS Catal. 11, 11129–11159 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao Y., et al. , Generating high-valent Iron-oxo identical withFe(IV) =O complexes in neutral microenvironments through peroxymonosulfate activation by Zn-Fe layered double Hydroxides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202209542 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li F., Lu Z., Li T., Zhang P., Hu C., Origin of the excellent activity and selectivity of a single-atom copper catalyst with unsaturated Cu-N2 sites via peroxydisulfate activation: Cu(III) as a dominant oxidizing species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8765–8775 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L. S., et al. , Carbon nitride supported high-loading Fe single-atom catalyst for activation of peroxymonosulfate to generate 1O2 with 100% selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 21751–21755 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B., Li X., Akiyama K., Bingham P. A., Kubuki S., Elucidating the mechanistic origin of a spin state-dependent FeNx-C catalyst toward organic contaminant oxidation via peroxymonosulfate activation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 1321–1330 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang L., et al. , Fe single-atom catalyst for efficient and rapid fenton-like degradation of organics and disinfection against bacteria. Small 18, e2104941 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Y., Zhu Y., Chen Z., Hu C., Nitrogen-coordinated cobalt embedded in a hollow carbon polyhedron for superior catalytic oxidation of organic contaminants with peroxymonosulfate. ACS ES&T Engg. 1, 76–85 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M., et al. , Unveiling the origins of selective oxidation in single-atom catalysis via Co–N4–C intensified radical and nonradical pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11635–11645 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao P., et al. , Copper in LaMnO3 to promote peroxymonosulfate activation by regulating the reactive oxygen species in sulfamethoxazole degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 125163 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X., et al. , Graphene oxide-supported three-dimensional cobalt-nickel bimetallic sponge-mediated peroxymonosulfate activation for phenol degradation. ACS ES&T Engg. 1, 1705–1714 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y., An H., Feng J., Ren Y., Ma J., Impact of crystal types of AgFeO2 nanoparticles on the peroxymonosulfate activation in the water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4500–4510 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Y., Chen Z., Zhu Y., Li T., Hu C., New insights into the generation of singlet oxygen in the metal-free peroxymonosulfate activation process: Important role of electron-deficient carbon atoms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1232–1241 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Y., et al. , Unraveling the high-activity origin of single-atom iron catalysts for organic pollutant oxidation via peroxymonosulfate activation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 8318–8328 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H., et al. , Asymmetric coordination of single-atom co sites achieves efficient dehydrogenation catalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2207408 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J., et al. , Asymmetric triple-atom sites confined in ternary oxide enabling selective CO2 photothermal reduction to acetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18233–18241 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuang L., et al. , Defect-induced Pt-Co-Se Coordinated sites with highly asymmetrical electronic distribution for boosting oxygen-involving electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 31, e1805581 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu K., Lou L. L., Liu S., Zhou W., Asymmetric oxygen vacancies: The intrinsic redox active sites in metal oxide catalysts. Adv. Sci. 7, 1901970 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma D., et al. , Enhanced catalytic ozonation for eliminating CH3SH via stable and circular electronic metal-support interactions of Si-O-Mn bonds with low Mn loading. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3678–3688 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Z., et al. , Modulating the electronic metal-support interactions in single-atom Pt1 -CuO catalyst for boosting acetone oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202200763 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao F., et al. , Maximizing the formation of reactive oxygen species for deep oxidation of NO via manipulating the oxygen-vacancy defect position on (BiO)2CO3. ACS Catal. 11, 7735–7749 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan S., et al. , Efficient and stable noble-metal-free catalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 13, 2294 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zu X., et al. , Ultrastable and efficient visible-light-driven CO2 reduction triggered by regenerative oxygen-vacancies in Bi2O2CO3 nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 13840–13846 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo L., et al. , Synergy of Pd atoms and oxygen vacancies on In2O3 for methane conversion under visible light. Nat. Commun. 13, 2930 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang D., et al. , Tailoring of electronic and surface structures boosts exciton-triggering photocatalysis for singlet oxygen generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2114729118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao Y., et al. , Highly efficient activation of peroxymonosulfate by bismuth oxybromide for sulfamethoxazole degradation under ambient conditions: Synthesis, performance, kinetics and mechanisms. Sep. Purif. Technol. 276, 119203 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun T., et al. , Single-atomic cobalt sites embedded in hierarchically ordered porous nitrogen-doped carbon as a superior bifunctional electrocatalyst. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 12692–12697 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z., et al. , Co-based catalysts derived from layered-double-hydroxide nanosheets for the photothermal production of light olefins. Adv. Mater. 30, e1800527 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng X., et al. , Ru-Co pair sites catalyst boosts the energetics for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202205946 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z., et al. , Cobalt single atoms anchored on oxygen-doped tubular carbon nitride for efficient peroxymonosulfate activation: Simultaneous coordination structure and morphology modulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202202338 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B., et al. , A site distance effect induced by reactant molecule matchup in single-atom catalysts for fenton-like reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202207268 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J., et al. , Organic wastewater treatment by a single-atom catalyst and electrolytically produced H2O2. Nat. Sustain. 4, 233–241 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen F., et al. , Efficient decontamination of organic pollutants under high salinity conditions by a nonradical peroxymonosulfate activation system. Water. Res. 191, 116799 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z., et al. , Toward selective oxidation of contaminants in aqueous systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14494–14514 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altmann J., Massa L., Sperlich A., Gnirss R., Jekel M., UV254 absorbance as real-time monitoring and control parameter for micropollutant removal in advanced wastewater treatment with powdered activated carbon. Water. Res. 94, 240–245 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J., et al. , Efficient catalytic elimination of CH3SH by a wet-piezotronics system over Ag cluster-deposited BaTiO3 with electronic metal-support interaction. ACS ES&T Engg. 2, 1179–1187 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li N., et al. , Correlation of active sites to generated reactive species and degradation routes of organics in peroxymonosulfate activation by Co-loaded carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 16163–16174 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Z., et al. , Oxygen and chlorine dual vacancies enable photocatalytic O2 dissociation into monatomic reactive oxygen on BiOCl for refractory aromatic pollutant removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3587–3595 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi J., et al. , Interface engineering of Co(OH)2 nanosheets growing on the KNbO3 perovskite based on electronic structure modulation for enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5200–5212 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou X., et al. , Identification of Fenton-like active Cu sites by heteroatom modulation of electronic density. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2119492119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian X., et al. , New insight into a fenton-like reaction mechanism over sulfidated beta-FeOOH: Key role of sulfidation in efficient iron(III) reduction and sulfate radical generation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5542–5551 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang T., Zhu H., Croue J. P., Production of sulfate radical from peroxymonosulfate induced by a magnetically separable CuFe2O4 spinel in water: Efficiency, stability, and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 2784–2791 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y., Zhang G., Liu H., Qu J., Confining free radicals in close vicinity to contaminants enables ultrafast fenton-like processes in the interspacing of MoS2 membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 8134–8138 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang X., et al. , Coordination number dependent catalytic activity of single-atom cobalt catalysts for fenton-like reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203001 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu L., et al. , Oxygen vacancy-induced nonradical degradation of organics: Critical trigger of oxygen (O2) in the Fe-Co LDH/peroxymonosulfate system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15400–15411 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miao J., et al. , Spin-state-dependent peroxymonosulfate activation of single-atom M-N moieties via a radical-free pathway. ACS Catal. 11, 9569–9577 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dai J., et al. , Single-phase perovskite oxide with super-exchange induced atomic-scale synergistic active centers enables ultrafast hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 11, 5657 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X., et al. , Single cobalt atoms anchored on porous N-doped graphene with dual reaction sites for efficient fenton-like catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12469–12475 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du J., et al. , Hydroxyl radical dominated degradation of aquatic sulfamethoxazole by Fe0/bisulfite/O2: Kinetics, mechanisms, and pathways. Water. Res. 138, 323–332 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang A., et al. , Motivation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by a novel non-thermal plasma coupled with calcium peroxide system for synergistic removal of sulfamethoxazole in waste activated sludge. Water. Res. 212, 118128 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qian K., et al. , Single-atom Fe catalyst outperforms its homogeneous counterpart for activating peroxymonosulfate to achieve effective degradation of organic contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 7034–7043 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y., et al. , Pulsed hydraulic-pressure-responsive self-cleaning membrane. Nature 608, 69–73 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All data of this study are included in the article and SI Appendix.