Significance

Two important features for cancer are the addiction to nutrients such as glucose, and the ability to escape immune clearance. How these two features are connected is poorly understood. Here, we reveal a link between glucose metabolism and cancer immune evasion. Aberrant glucose metabolism produces high levels of N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc), a ubiquitous form of protein modification. O-GlcNAc suppresses the degradation of the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in cancer cells, the level of which is closely associated with cancer immune evasion. Reducing O-GlcNAc sensitizes cancer cells to immune cell killing, and inhibits tumor growth in mice. The study enhances our understanding of cancer immune regulation, and suggests strategies to improve cancer immune therapy.

Keywords: O-GlcNAcylation, cancer immune evasion, PD-L1, intracellular trafficking

Abstract

Programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and its receptor programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) mediate T cell–dependent immunity against tumors. The abundance of cell surface PD-L1 is a key determinant of the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy targeting PD-L1. However, the regulation of cell surface PD-L1 is still poorly understood. Here, we show that lysosomal degradation of PD-L1 is regulated by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) during the intracellular trafficking pathway. O-GlcNAc modifies the hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HGS), a key component of the endosomal sorting machinery, and subsequently inhibits its interaction with intracellular PD-L1, leading to impaired lysosomal degradation of PD-L1. O-GlcNAc inhibition activates T cell–mediated antitumor immunity in vitro and in immune-competent mice in a manner dependent on HGS glycosylation. Combination of O-GlcNAc inhibition with PD-L1 antibody synergistically promotes antitumor immune response. We also designed a competitive peptide inhibitor of HGS glycosylation that decreases PD-L1 expression and enhances T cell–mediated immunity against tumor cells. Collectively, our study reveals a link between O-GlcNAc and tumor immune evasion, and suggests strategies for improving PD-L1-mediated immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

The ability to escape immune surveillance is one of the hallmarks of cancer (1). The programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) is a key immune checkpoint protein highly expressed on cancer cell surface and closely associated with cancer immune evasion (2, 3). The interaction of PD-L1 with its receptor PD-1 expressed on cytotoxic T lymphocytes induces the inhibitory signal that attenuates their antitumor activity (4, 5). Recently, the immune checkpoint blockade therapy that employs neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to disrupt PD-L1/PD-1 interaction to restore T cell antitumor activity has emerged as a promising strategy for treating multiple tumor types with considerable efficacy (6–8). However, the patient responsive rate is still quite low in various cancer types, and that therapeutic resistance gradually develops as the treatment progresses (9–12). The level of PD-L1 is considered as a key biomarker to evaluate the clinical responsiveness of the anti-PD-L1/PD-1 therapy (13–15). Therefore, it is critical to fully understand the regulation of PD-L1 expression.

The cellular expression of PD-L1 is tightly controlled at both transcriptional and translational levels (16, 17). Multiple transcription factors such as STAT (18, 19), ATF3 (20), c-Myc (21), and NF-κB (22, 23) directly or indirectly induce the expression of CD274 encoding PD-L1. Recent studies also reveal a myriad of posttranslational modifications that regulate PD-L1 activity, stability, and degradation. For example, N-linked glycosylation of the extracellular domain of PD-L1 promotes its stability by inhibiting 26S proteosome-dependent degradation (24). Phosphorylation of PD-L1 S195 by AMP-activated protein kinase induces its ER accumulation and ER-associated protein degradation (25). Palmitoylation of PD-L1 cytoplasmic domain stabilizes PD-L1 by inhibiting its ubiquitination and degradation through the lysosomal pathway (26).

O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is a prevalent protein modification that occurs on thousands of intracellular proteins (27). This modification is biosynthesized in the cell via the glucose metabolism. Fructose-6-phosphate enters the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway to produce uridine-diphosphate GlcNAc (UDP-GlcNAc), the key substrate for the subsequent glycosyl transfer reaction to generate GlcNAc-modified proteins (28, 29). Inside the cell, O-GlcNAc modification is dynamically and reversibly controlled by a set of enzymes with opposing functions: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) catalyzes the addition of O-GlcNAc onto serine/threonine residues of protein substrates; O-GlcNAc hydrolase (OGA) catalyzes the removal of O-GlcNAc from proteins (30, 31). O-GlcNAc levels were consistently up-regulated across a range of cancer types, including hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, lung cancer, and breast cancer (32–34). Studies have revealed critical roles of O-GlcNAc in promoting cancer metabolism, growth and proliferation, and distant organ metastasis (35–37). However, how O-GlcNAc links to cancer immune evasion still remains elusive.

In this study, we revealed a previously unknown link between hyper-O-GlcNAcylation and immune evasion in cancer. O-GlcNAcylation impacts PD-L1 expression mainly via the lysosomal degradation pathway. O-GlcNAcylation inhibited the interaction of PD-L1 with the endosomal sorting machinery, which blocks PD-L1 intracellular trafficking from early endosomes to lysosomes for degradation, leading to enhanced PD-L1 expression and suppression of T cell antitumor activity. Inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation reduced PD-L1 expression and consequently restored T cell cytotoxicity in vitro and in immune-competent mice.

Results

OGT Expression Correlates with Prognosis and Immunogenicity in Cancers.

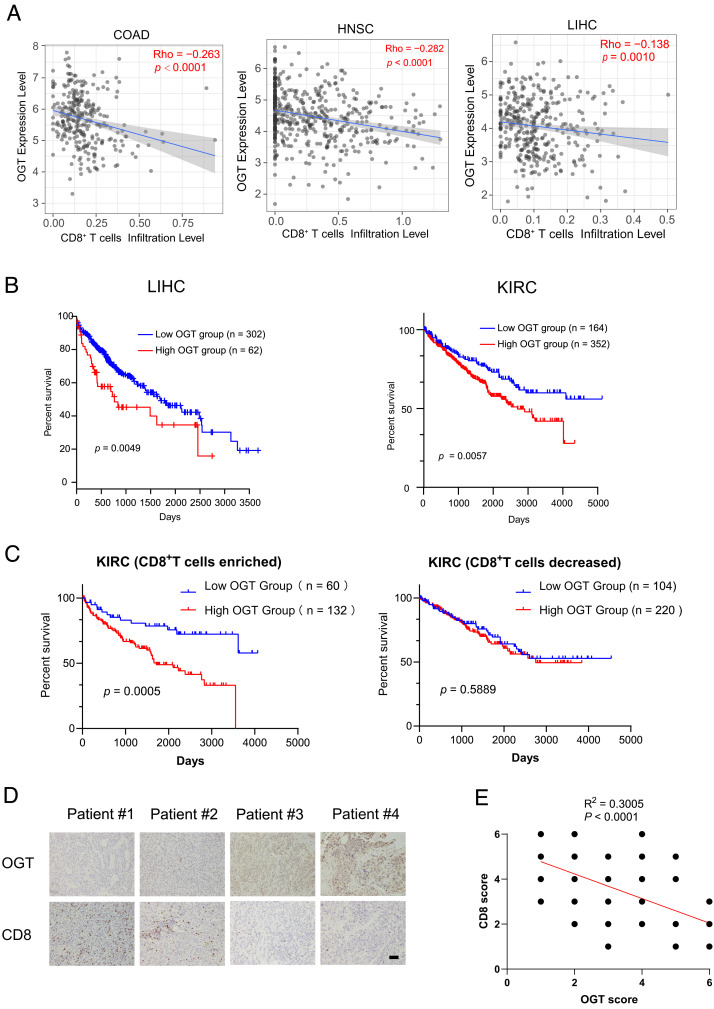

To explore the connection of OGT expression with immunogenicity in cancers, we first analyzed the correlations between OGT mRNA level and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells using the TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org) based on the RNA-seq datasets derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Statistical deconvolution of immune infiltration revealed that OGT expression is inversely correlated with CD8+ T cell infiltration levels relative to either total leukocytes or nontumor cells in various types of cancer. High OGT expression is associated with reduced fraction of CD8+ subsets within the overall leukocytes in liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) and stomach adenocarcinoma, while it is also associated with decreased abundance of CD8+ cells inside the tumor microenvironment in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), bladder urothelial carcinoma, and brain lower-grade glioma (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Consistently, OGT mRNA expression is positively correlated with the expression of T cell exhaustion-related genes such as PDCD1, CD200, TGFBR2, TNFRSF9, CTLA4, SEMA4C, and SEMA7A in the LIHC dataset (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). The Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that high levels of OGT mRNA expression were correlated with poor prognosis in LIHC and kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) patients (Fig. 1B). Notably, when KIRC patients were classified into CD8+ T cell–enriched and CD8+ T cell–decreased populations, the further analysis indicated that OGT expression was only significantly correlated with poor prognosis in the CD8+ T cell–enriched population, but not in the CD8+ T cell–decreased population (Fig. 1C). Further, we performed immunohistochemistry analysis of CD8 and OGT expression in a cohort of 50 LIHC specimens (Fig. 1 D and E). The results showed that the level of CD8 was inversely correlated with OGT expression in the LIHC specimens. Together, these data suggest that OGT plays a role in tumor immunity during the tumor progression.

Fig. 1.

OGT expression correlates with prognosis and immunogenicity in cancers. (A) Correlation analysis of OGT mRNA level and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells using the TIMER2.0 website (http://timer.cistrome.org) based on the RNA-seq datasets derived from TCGA database (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). Infiltration levels of CD8+ T cells within the overall leukocyte population in liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) were estimated by CIBERSORT, while infiltration levels of CD8+ T cells relative to nontumor cells within the gross tumor microenvironment of colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) and head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) were estimated by TIMER. (B) Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves of LIHC (n = 364, cutoff-high% = 17%) and KIRC (n = 516, cutoff-high% = 68%) patients with of high and low OGT mRNA expression obtained from the TCGA database. (C) Overall survival of KIRC patients with decreased (n = 324) or enriched (n = 192) CD8+ T cells and with high or low expression of OGT (cutoff-high% = 68%). Statistical analyses were performed by the two-tailed log-rank test. (D) Immunohistochemistry staining of human LIHC samples with the indicated antibodies. (Scale bar, 40 μm.) (E) The semi-quantitative evaluation of the staining of the tissue sections according to intensity and area. The following proportion scores were assigned to the sections: “no staining (0),” “weak staining (1),” “moderate staining (2),” or “strong staining (3).” A Pearson’s correlation test was used (two tailed) (n = 50). Some of the dots on the graphs are overlapped and represent more than one specimen.

Inhibition of OGT Enhances T Cell–Dependent Tumor Suppression.

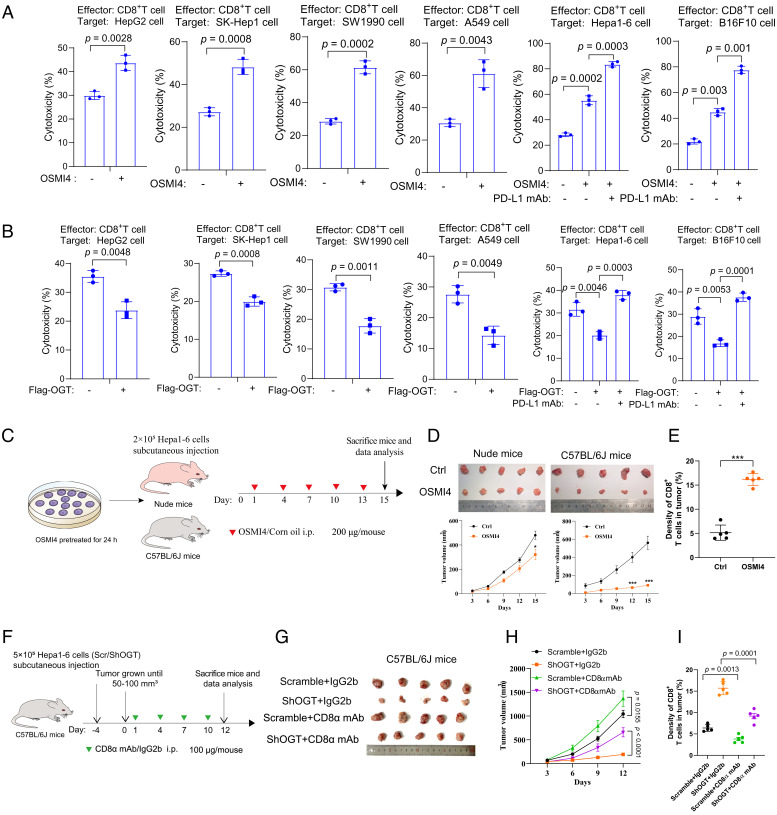

To investigate the role of OGT in tumor immunity, we inhibited OGT activity with a known specific inhibitor OSMI-4 in a range of cancer cell lines, including human hepatoma cell lines HepG2 and SK-Hep-1, pancreatic cancer cell line SW1990, lung cancer line A549, mouse hepatoma cell line Hepa1-6, and mouse melanoma cell line B16F10. Cells were treated with OSMI-4 for 24 h, followed by culturing in the inhibitor-free medium for another 24 h. Cell proliferation of SW1990 and A549 cells was slightly inhibited, while no apparent inhibition was observed in HepG2, SK-Hep1, Hepa1-6, or B16-F10 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). We then carried out T cell–mediated tumor cell-killing assays in which tumor cells were cocultured with activated human lymphocytes (peripheral blood mononuclear cells). Compared to the control (DMSO-treated) cells, OSMI-4-treated cells showed enhanced cell cytotoxicity, accompanied by the reduction of global O-GlcNAcylation levels and PD-L1 levels (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Overexpression of OGT, in contrast, decreased cell cytotoxicity and increased O-GlcNAcylation levels (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). The expression level of PD-1 increased dramatically in the activated T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). Treatment with PD-L1 monoclonal antibody to block the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction enhanced cell cytotoxicity in cells either treated with OSMI-4 or with OGT overexpression (Fig. 2 A and B). Thus, these data suggest that OGT-mediated glycosylation in cancer cells suppresses T cell immunity in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of OGT enhances T cell–dependent tumor suppression. (A and B) T cell cytotoxicity of indicated cancer cells after treatment with 20 μM OSMI-4 (A) or overexpression of OGT (B) for 24 h. Cells were then incubated in OSMI-4-free medium and cocultured with peripheral blood mononuclear cells for another 24 h. PD-L1 mAb (2 μg) was added into the medium and incubated for 24 h. Cell cytotoxicity was analyzed by lactate dehydrogenase release assays (n = 3 independent assays). (C) Schematic depiction of the xenograft study. Hepa1-6 cells pretreated with OSMI-4 or DMSO for 24 h were subcutaneously injected into nude mice or C57BL/6 mice (n = 5). OSMI-4 (200 μg/mouse) or vehicle was intraperitoneally injected into mice at indicated time points. At day 15, mice were killed and analyzed. (D) The images and growth curves of tumors from nude mice and C57BL/6 mice. Tumor volumes measured at indicated time points. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of CD8+ T cells in C57BL/6 mice bearing tumors with an anti-CD8 antibody. (F) Schematic depiction of the tumor formation in C57BL/6 mice. C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were injected with scramble shRNA-infected or shOGT-infected Hepa1-6 cells and further treated with IgG2b or CD8α mAb at indicated time points. (G) Images of the dissected tumors at the experimental end point. (H) Growth curves of tumors measured at indicated time points. (I) Immunohistochemical analysis of CD8+ T cells in tumors (n = 5). Error bars in A–I denote the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

To investigate whether inhibition of OGT enhances T cell antitumor activity in vivo, we injected mouse hepatoma cell line Hepa1-6 subcutaneously into nude mice and immune-competent C57BL/6 mice. Pretreatment with OSMI-4 greatly suppressed tumor growth in C57BL/6 mice, but only modestly in nude mice (Fig. 2 C and D). Similar effect was observed in OGT knockdown (KD) cell-derived tumors as compared to the control (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Immunohistochemistry assays indicated an increased number of tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in tumors treated with OSMI-4 as compared to the control (Fig. 2E). To further verify whether the OGT-mediated antitumor effect is dependent on CD8+ T cells, we employed a CD8α monoclonal neutralizing antibody (mAb) to block the CD8+ T cell activity in C57BL/6 mice. The immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype CTRL (IgG2b) treatment was used as a control experiment. In mice bearing control tumors, CD8α mAb treatment promoted tumor growth moderately as compared to the IgG2b treatment (Fig. 2 F–H). Notably, in mice bearing OGT knockdown tumors, CD8α mAb treatment significantly promoted the tumor burden (Fig. 2 F–H). Consistently, the presence of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues negatively correlated with the tumor burden (Fig. 2I). Taken together, these results suggest that OGT inhibition suppressed tumor growth in a manner dependent on CD8+ T cell activity.

OGT Attenuates Lysosomal Degradation of PD-L1.

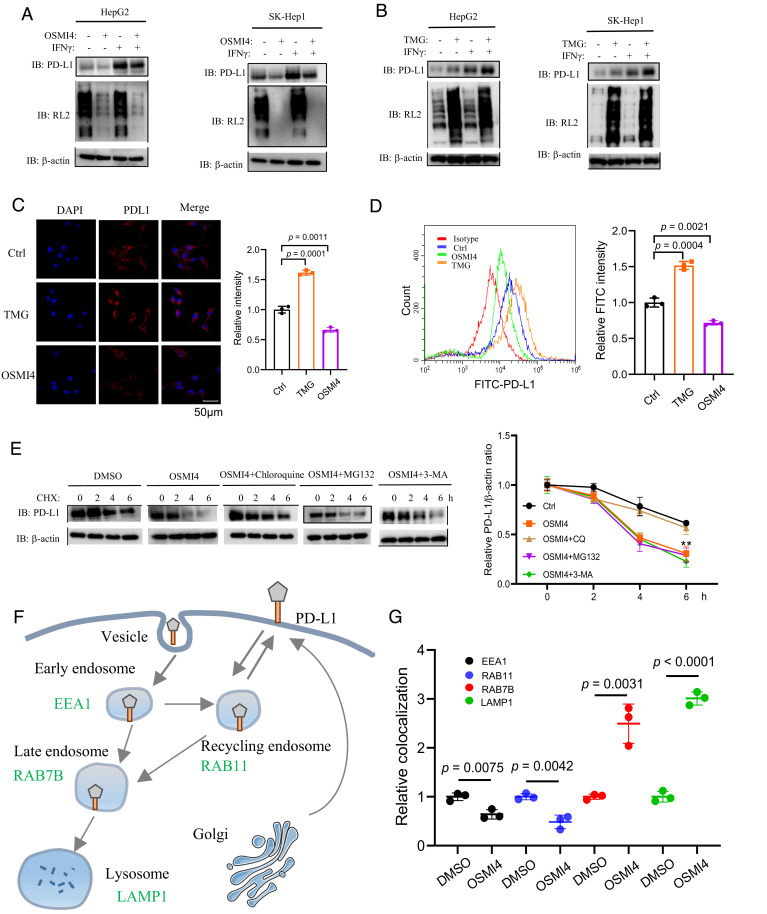

The interaction between PD-L1 expressed on tumor cells and PD-1 expressed on T cells governs the T cell–mediated antitumor activity. The expression level of PD-L1 is considered as a key determinant of the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. To explore the mechanism by which OGT regulates CD8+ T cell activity, we next try to examine the link between OGT-mediated O-GlcNAcylation and PD-L1 cellular levels. We observed that OSMI-4 treatment or OGT knockdown reduced both the basal and IFN-γ-stimulated PD-L1 levels in different cell lines (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). In addition, PD-L1 levels were reduced when treated with different concentrations of OSMI-4 in a dose-dependent manner, while Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) class I protein levels were not affected (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). In contrast, treatment with OGA inhibitor thimet G (TMG), or OGT overexpression, increased PD-L1 levels (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). The effects of OSMI-4 and TMG on PD-L1 expression were further confirmed by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry assays (Fig. 3 C and D). Notably, PD-L1 mRNA levels were not affected with either OSMI-4 or TMG treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). Together, these data suggest that OGT-mediated O-GlcNAcylation regulates PD-L1 expression at the level of protein expression or turnover.

Fig. 3.

OGT attenuates lysosomal degradation of PD-L1. (A and B) Immunoblotting analysis of global glycosylation and PD-L1 levels in HepG2 and SK-Hep-1 cells upon treatment with OSMI-4 (A) or TMG (B) in the presence or absence of IFN-γ. (C and D) Immunofluorescent (C) and flow cytometry (D) analysis of cell surface PD-L1 levels in SK-Hep1 cells upon OSMI4 or TMG treatment. The PD-L1 intensity was quantified (n = 3 independent assays). (E) Immunoblotting analysis of PD-L1 levels in SK-Hep-1 cells with cycloheximide (CHX) treatment at indicated time points, in the presence of inhibitors for lysosome (chloroquine), autophagy (3-MA), or proteasome (MG132). The relative level of PD-L1 was determined by the intensity ratio of PD-L1/actin. (F) The schematic depiction of PD-L1 trafficking from the plasma membrane to early endosomes (marked by EEA1), recycling endosomes (Rab11), late endosomes (Rab7b), and lysosomes (Lamp1). (G) Quantification of the relative colocalization of PD-L1 and EEA1/Rab11/Rab7b/Lamp1 in SK-Hep-1 cells after treatment with OSMI4 or DMSO for 48 h (n = 3 independent assays). Error bars in C–E denote the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

Next we investigate how O-GlcNAcylation regulates PD-L1 expression. PD-L1 is a transmembrane protein extensively modified by N-linked glycosylation at Asn192, Asn200, and Asn219, which stabilizes PD-L1 expression (24). O-GlcNAcylation, in contrast, has not been reported on PD-L1. Consistently, we were not able to detect the O-GlcNAcylation signal on PD-L1 via a well-established chemoenzymatic labeling method (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). To determine which degradation pathway of PD-L1 is regulated by O-GlcNAcylation, we ectopically expressed PD-L1 in SK-Hep-1 cells and examined the half-life of PD-L1 in the presence of small-molecular inhibitors of different degradation pathways. As shown in Fig. 3E, the reduction of PD-L1 by OGT inhibition was reversed by the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine, but not the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 or the autophagy inhibitor 3-Methyladenine (3-MA), suggesting that OGT influences PD-L1 expression through the lysosomal degradation pathway.

In the lysosomal degradation pathway, PD-L1 is first monoubiquitinated and internalized into the cell through clathrin-mediated endocytosis to early endosomes. It is then sorted from early endosomes to recycling endosomes to recycle back to the cell surface, or to late endosomes/lysosomes through multivesicular bodies (MVB) for degradation (38) (Fig. 3F). To clarify the steps of which OGT regulates PD-L1 degradation, we inhibited OGT in SK-Hep-1 cells stably expressing PD-L1 and analyzed PD-L1 distribution in different subcellular organelles. We analyzed the localization of PD-L1 at early endosomes and recycling endosomes by coimmunostaining PD-L1 with early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1, a marker for early endosomes) and RAB11 (a marker for recycling endosomes), respectively. The results showed that OSMI-4 treatment decreased the colocalization signal of PD-L1 and EEA1, compared to the control (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Besides, OSMI-4 treatment also repressed the colocalization signal of PD-L1 and RAB11 (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Subsequently, we analyzed the colocalization of PD-L1 with late endosome marker RAB7B and observed that OSMI-4 treatment enhanced the colocalization signal of PD-L1 and RAB7B (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Consistently, OSMI-4 treatment also increased the colocalization of PD-L1 with the lysosome marker LAMP1 (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Together, these results suggest that inhibition of OGT promotes PD-L1 trafficking from early endosomes to late endosomes and lysosomes, consistent with the accelerated degradation of PD-L1.

OGT Regulates PD-L1 Expression Via ESCRT-Mediated Intracellular Trafficking.

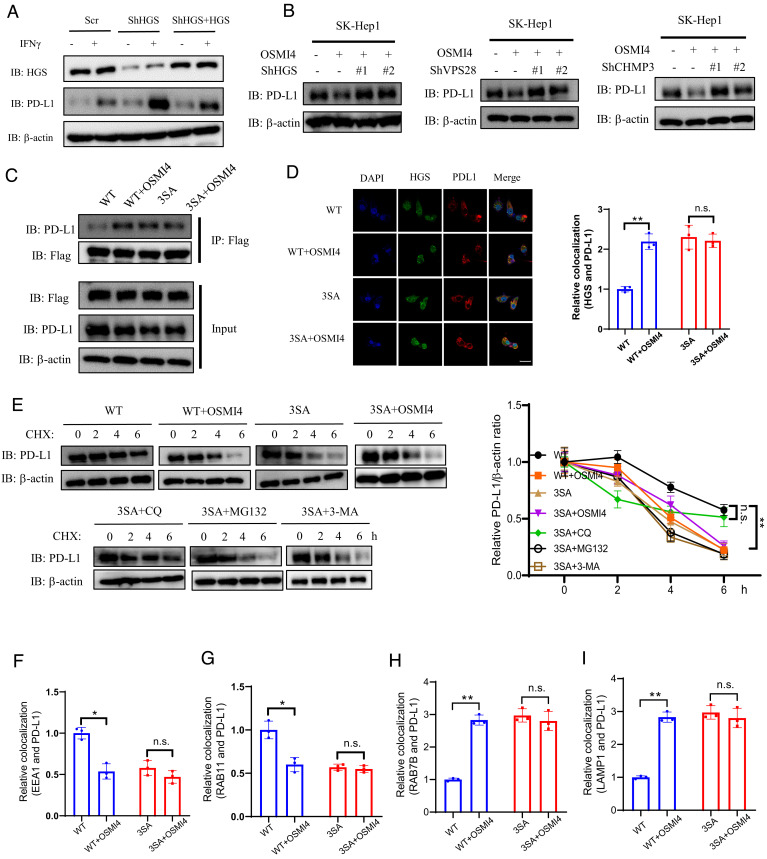

Membrane proteins are sorted from early endosomes through multivesicular bodies (MVB) to late endosomes, a process mediated by the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) (39). ESCRT consists of four complexes, namely ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, and ESCRT-III. ESCRT-0 recognizes the ubiquitinated protein cargo and initiates the sorting process from the early endosome (40). We first examined whether OGT inhibition-mediated PD-L1 degradation was dependent on ESCRT. Depletion of ESCRT-0 subunit HGS (hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate) in SK-Hep-1 cells caused upregulation of both basal and IFN-γ-stimulated PD-L1 levels, but not its mRNA levels (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). This effect was reversed by the reconstituted expression of shRNA-resistant HGS, thus verifying the target specificity of the shRNA (Fig. 4A). Notably, HGS depletion effectively rescued PD-L1 degradation induced by OSMI-4 treatment (Fig. 4B). Similarly, depletion of ESCRT-I subunit VPS28 or ESCRT-III subunit CHMP3 also rescued PD-L1 degradation induced by OSMI-4 treatment (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B), thus verifying the involvement of ESCRT complexes in PD-L1 lysosomal degradation.

Fig. 4.

OGT regulates PD-L1 expression via ESCRT-mediated intracellular trafficking. (A) Immunoblotting of PD-L1 expression in SK-Hep-1 cells infected with scramble shRNA or shRNA targeting HGS, with or without IFN-γ treatment. (B) Immunoblotting of PD-L1 expression in SK-Hep-1 cells upon the depletion of HGS, VPS28, and CHMP3, in the presence or absence of OSMI-4 treatment. (C) Immunoblotting of HGS and PD-L1 interaction in wild-type (WT) or 3SA HGS reconstituted SK-Hep-1 cells with or without OSMI-4 treatment. (D, Left) Immunofluorescence staining of WT or 3SA HGS-reconstituted SK-Hep-1 cells with HGS and PD-L1 antibodies in the presence or absence of OSMI-4 treatment. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) Right Quantification of HGS and PD-L1 colocalization (n = 3 independent assays). (E) Immunoblotting of PD-L1 levels in WT or 3SA HGS-reconstituted SK-Hep-1 cells by CHX treatment in the presence of inhibitors for lysosome (chloroquine), autophagy (3-MA), or proteasome (MG132). Quantification was shown. (F–I) Quantification of EEA1-PD-L1 (F), RAB11-PD-L1 (G), RAB7-PD-L1 (H), and LAMP1-PD-L1 (I). Colocalization in WT or 3SA HGS-reconstituted SK-Hep-1 cells with or without OSMI-4 treatment (n = 3 independent assays). Error bars in D–I denote the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

Our previous study showed that HGS is highly O-GlcNAcylated (41). Glycosylation of HGS impairs ESCRT-0 formation and inhibits EGFR lysosomal trafficking and degradation (41). Thus, we next investigate whether HGS glycosylation plays a role in PD-L1 lysosomal degradation. We verified that HGS glycosylation levels were decreased in the presence of OSMI-4 treatment or OGT knockdown in SK-Hep-1 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D). We then generated stably transfected SK-Hep-1 cells, in which endogenous HGS was depleted and reconstituted with shRNA-resistant wild-type (WT) HGS or glycosylation-deficient HGS (3SA) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). We observed that PD-L1 expression was higher in WT HGS-reconstituted cells than 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells by western blotting and immunofluorescent staining [Fig. 4C (Input), and SI Appendix, Fig. S6F]. OSMI-4 treatment down-regulated PD-L1 levels in WT HGS-reconstituted cells but not in 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells [Fig. 4C (Input)]. OSMI4 treatment increased the association of PD-L1 with WT HGS but not with 3SA HGS [Fig. 4C (IP)]. Immunofluorescence assays detecting the colocalization of these two proteins in cells showed similar observations (Fig. 4D). The turnover rate of PD-L1 was much faster in 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells as compared to WT HGS-reconstituted cells (Fig. 4E). As expected, chloroquine, but not MG132 or 3-MA, rescued PD-L1 degradation in 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells (Fig. 4E).

We further probed the endosomal trafficking of PD-L1 in the above-reconstituted cell lines in the presence or absence of OSMI-4 treatment. The colocalization of PD-L1 with EEA1 and RAB11 was significantly increased, while the colocalization with RAB7B and LAMP1 was significantly decreased, in WT HGS-reconstituted cells compared to 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells (Fig. 4 F and G and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8). Treatment with OSMI-4 reduced the colocalization of PD-L1 with EEA1 and RAB11 in WT HGS-reconstituted cells, but not in 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells (Fig. 4 F and G and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8). Consistently, the colocalizations of PD-L1 with RAB7B and with LAMP1 were increased upon OSMI-4 treatment in WT HGS-reconstituted cells, but not in 3SA HGS-reconstituted cells (Fig. 4 H and I and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10). Collectively, these data show that HGS O-GlcNAcylation up-regulates PD-L1 levels via impaired lysosomal degradation of PD-L1.

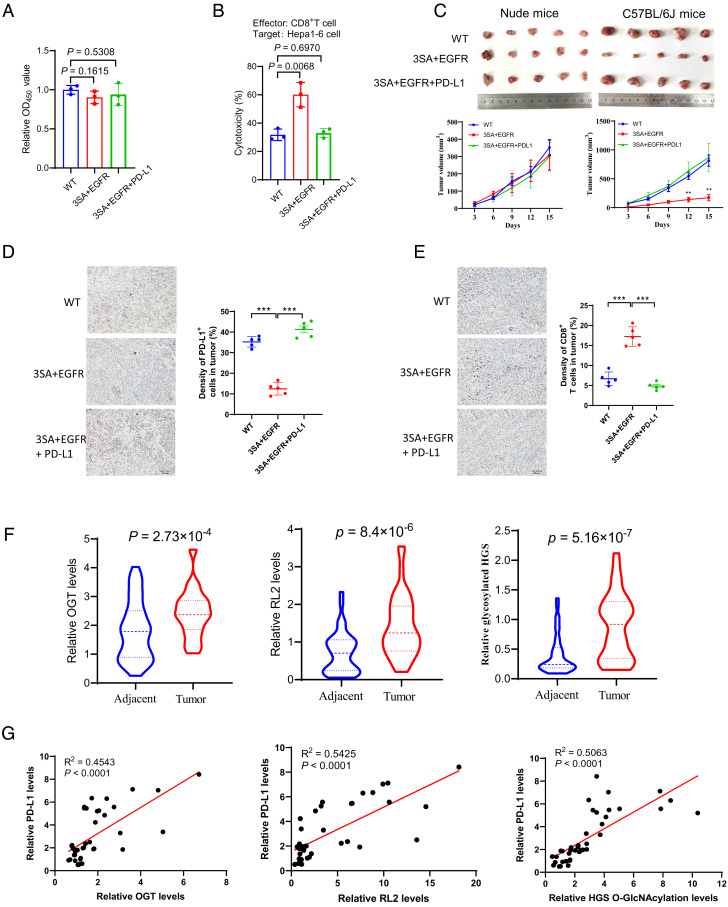

HGS Glycosylation-Mediated PD-L1 Expression Promotes Tumor Growth.

Since HGS O-GlcNAcylation regulated PD-L1 expression, we further asked whether HGS O-GlcNAcylation affected the sensitivity of T cell cytotoxicity in tumor cells. Our previous study showed that HGS O-GlcNAcylation affects EGFR degradation to regulate cell proliferation of HCC cells (41). Therefore, to rule out the antiproliferative effect mediated by EGFR, we restored EGFR expression in 3SA HGS-reconstituted Hepa1-6 cells (designated as EGFR-HGS 3SA cells, SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A and B). We verified that restoration of EGFR expression resulted in similar cell proliferation rates of 3SA HGS-reconstituted Hepa1-6 cells and WT HGS-reconstituted cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, restoration of PD-L1 expression in EGFR-HGS 3SA cells did not affect cell proliferation (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S11C). Coculture with T cells exhibited a marked cytotoxic activity against EGFR-HGS 3SA cells, but not WT HGS-reconstituted cells or EGFR-HGS 3SA cells with PD-L1 restoration (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

HGS glycosylation-mediated PD-L1 expression promotes tumor growth. (A) Cell proliferation analysis of stable SK-Hep-1 cells expressing WT or 3SA HGS, with ectopic expression of EGFR or PD-L1. (B) Analysis of cytotoxicity in stable SK-Hep-1 cells expressing WT or 3SA HGS, with ectopic expression of EGFR or PD-L1. (C) The images and growth curves of tumors derived from stable SK-Hep-1 cells expressing WT or 3SA HGS, with ectopic expression of EGFR or PD-L1, in nude mice and immune-competent C57BL/6 mice, respectively. Tumor volumes measured at indicated time points. (D and E) Immunohistochemical analysis of PD-L1 expression (D) and CD8+ T cell infiltration (E) in tumors from the C57BL/6 mice. (Scale bar, 40 μm.) (F) Quantification of OGT, global O-GlcNAcylation levels (RL2), and HGS O-GlcNAcylation levels from primary liver cancer tissues and the matched peritumoral tissues (n = 40 pairs). (G) Analysis of the correlation of OGT/PD-L1, RL2/PD-L1, and glycosylated HGS/PD-L1 from tumors. Error bars in A–F denote the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

To investigate whether HGS O-GlcNAcylation regulated T cell antitumor activity in vivo, we subcutaneously injected the above cell lines into nude mice and immune-competent C57BL/6 mice, respectively, and monitored the tumor growth. The results revealed that all the three cell lines developed tumors at a comparable rate and size in nude mice (Fig. 5C). Notably, in C57BL/6 mice, EGFR-HGS 3SA cells developed much smaller tumors than the other two cell lines (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S11 D and E). Moreover, PD-L1 expression levels negatively correlated with CD8+ T cell infiltration levels in these tumors (Fig. 5 D and E). The results suggest that HGS glycosylation-mediated PD-L1 expression promotes tumor growth in a manner dependent on T cell immunity.

To further probe the clinical association between OGT-mediated glycosylation and PD-L1 expression, we collected 40 pairs of human liver cancer tissue samples with matched peritumoral tissues and analyzed the levels of OGT, total glycosylation, HGS, HGS glycosylation, and PD-L1 (SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13). We observed that OGT levels, total glycosylation, and HGS glycosylation were all up-regulated in tumor tissues compared to the matched peritumoral tissues (Fig. 5F). In tumor tissues, OGT levels, total glycosylation, and HGS glycosylation showed positive correlation with PD-L1 levels (Fig. 5G). Together, these results are consistent with the cellular data and demonstrate the clinical relevance between OGT-mediated glycosylation and PD-L1 expression.

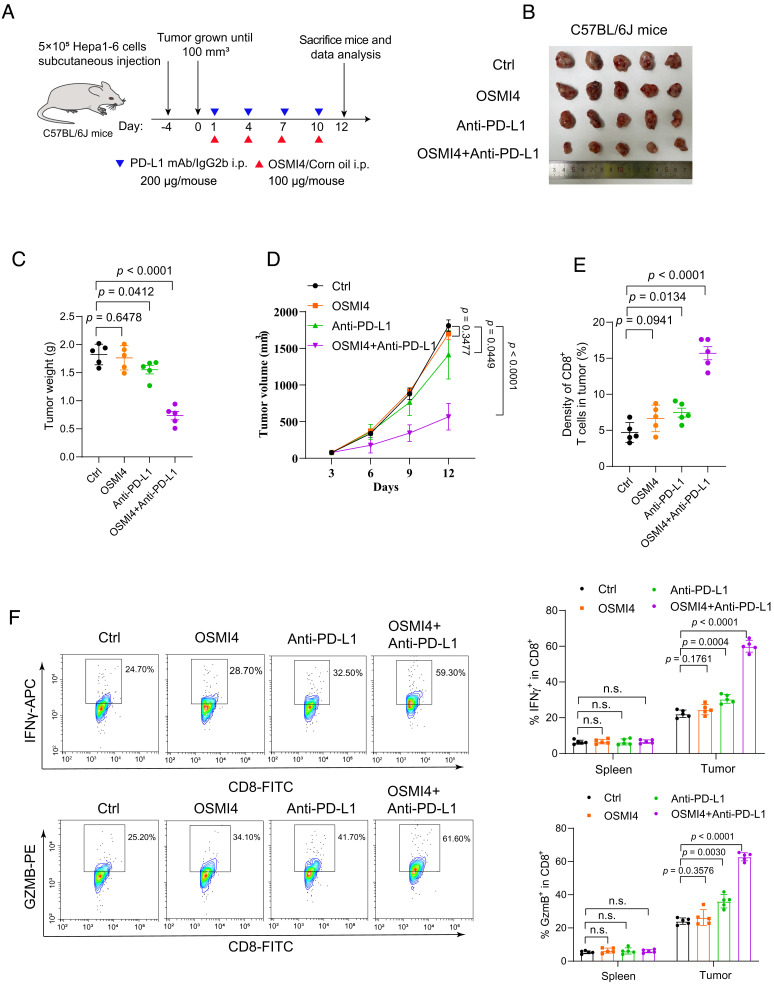

OGT Inhibition Synergizes with PD-L1 mAb Therapy.

As OGT inhibition down-regulates PD-L1 expression and enhances T cell antitumor activity, we speculate that OGT inhibition might enhance the effect of PD-L1 mAb therapy. To test this, we employed a PD-L1 mAb to treat immune-competent C57BL/6 mice inoculated with Hepa1-6 cells treated with or without OSMI-4 (Fig. 6A). PD-L1 mAb treatment modestly reduced tumor volume in cells treated with DMSO (Fig. 6 B–D). More notably, combination treatment with PD-L1 mAb and OSMI-4 further decreased the tumor volume, compared to OSMI-4, or PD-L1 mAb treatment alone (Fig. 6 B–D). The combination of OSMI-4 and PD-L1 mAb had no impact on the weight of the mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A). Immunohistochemistry staining showed that combination treatment significantly increased the number of tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S14B). Importantly, we also found that combination treatment markedly increased CTL activity by elevating IFN-γ and GZMB levels as compared to treatment alone (Fig. 6F). Similarly, combination treatment of mouse melanoma tumors with PD-L1 mAb and OSMI-4 also significantly suppressed tumor growth compared to treatments with PD-L1 mAb or OSMI-4 alone (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 C–E). Together, these results indicate that OGT inhibition synergizes with the current immune blockade therapy and leads to a more pronounced suppression of tumor growth.

Fig. 6.

OGT inhibition synergizes with PD-L1 mAb therapy. (A) Schematic depiction of the combination therapy using anti-PD-L1 antibody (200 μg/mouse) and OSMI-4 (100 μg/mouse). (B) Images of tumors harvested from mice bearing Hepa1-6 cells treated with anti-PD-L1 antibody, or OSMI-4, or their combination (n = 5). (C–E) Analysis of tumors weight (C), tumor growth curve (D), and CD8+ T cell infiltration in tumors (E). (F) Flow cytometric analysis and quantification of intracellular cytokine staining of IFN-γ and granzyme B in CD8+ T cell populations separated from spleen and tumor of BALB/c mice. Error bars in C–F denote the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

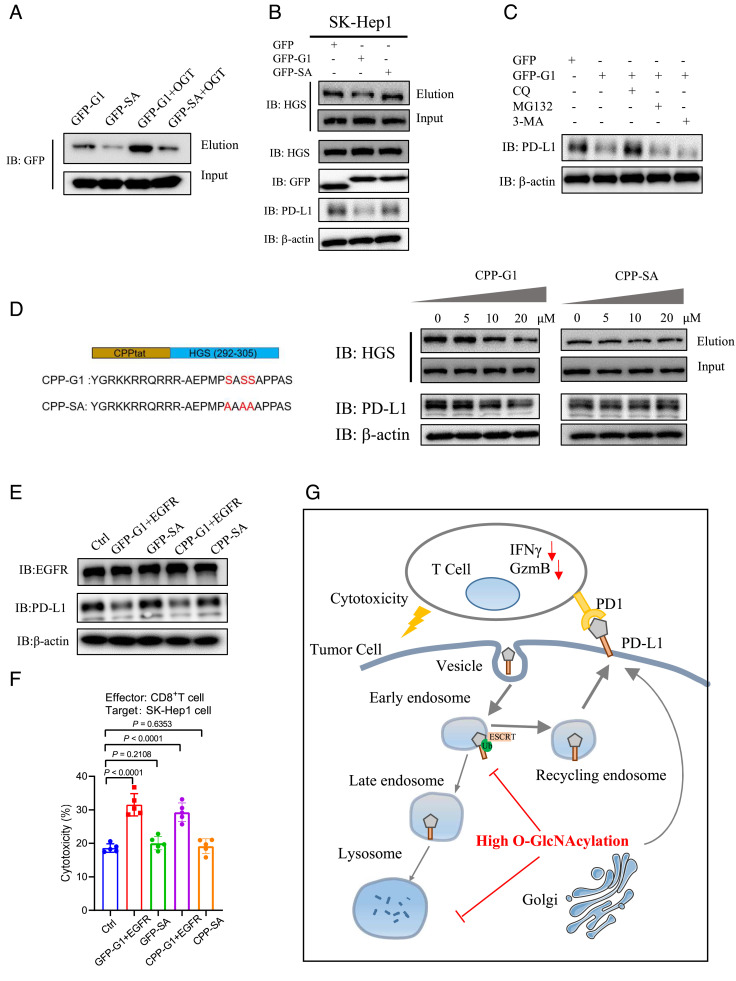

A Designed Peptide Targeting HGS Glycosylation Down-Regulates PD-L1 Expression.

As OGT catalyzes O-GlcNAcylation on numerous protein substrates, inhibition of OGT with small molecules likely causes some undesired side effects. In contrast, design of specific peptides to competitively inhibit glycosylation of the protein of interest without perturbing the global cellular glycosylation might serve as an attractive alternative. To our knowledge, such a strategy has not been used to inhibit specific O-GlcNAcylated protein substrates. With the information of the HGS peptide sequence that harbors the glycosylation sites, we ask whether this short peptide can be used to competitively inhibit HGS glycosylation and subsequently reduce PD-L1 expression in cells. First, we generated fusion proteins in which green fluorescent protein (GFP) is linked to HGS peptide sequence (aa 292-305) containing the glycosylation sites (referred to as GFP-G1), or the control sequence containing 3SA mutations (GFP-SA). Expectedly, GFP-G1 showed a stronger O-GlcNAcylation signal than GFP-SA in the presence or absence of OGT overexpression in SK-Hep-1 cells (Fig. 7A). Ectopic expression of GFP-G1, but not GFP-SA, reduced HGS glycosylation levels and PD-L1 levels, with no apparent effect on cellular O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Fig. S15A). Chloroquine, but not MG132 or 3-MA, rescued PD-L1 levels (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that HGS glycosylation in cells can be targeted by competitive inhibition.

Fig. 7.

A designed peptide targeting HGS glycosylation down-regulates PD-L1 expression. (A) Immunoblotting of GFP-G1 and GFP-SA O-GlcNAcylation levels in SK-Hep-1 cells in the presence or absence of OGT overexpression. (B) Immunoblotting of PD-L1, GFP, HGS, and HGS O-GlcNAcylation levels in SK-Hep-1 cells transfected with GFP, GFP-G1, or GFP-SA plasmid. (C) Immunoblotting of PD-L1 levels in SK-Hep-1 cells expressing GFP or GFP-G1 in the presence of inhibitors for lysosome (chloroquine), autophagy (3-MA), or proteasome (MG132). (D, Left) Depiction of CPP-conjugated peptides; Right, immunoblotting of PD-L1 and HGS O-GlcNAcylation levels in SK-Hep-1 cells incubated with different concentrations of CPP-G1 or CPP-SA for 20 h. (E) Immunoblotting of EGFR and PD-L1 levels in SK-Hep-1 cells expressing GFP-G1, GFP-SA, or treated with CPP-G1 or CPP-SA. EGFR expression was reconstituted in cells expressing GFP-G1, or in cells treated with CPP-G1. (F) Analysis of cytotoxicity in SK-Hep-1 cells expressing GFP-G1, GFP-SA, or treated with CPP-G1 or CPP-SA. (G) A graphical model of HGS O-GlcNAcylation-mediated PD-L1 intracellular trafficking and lysosomal degradation, and the link to tumor immune evasion. Error bars in f denote the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

Next, we attempted to deliver this competitive peptide into the cell. Cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) has been widely used to deliver biomolecules into cells (42, 43). We chemically synthesized a peptide sequence containing CPP, HGS peptide (G1 or SA), and the fluorescent marker FITC. After incubation with the synthetic peptide for 20h, FITC signals were clearly observed in SK-Hep-1 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S15B). Treatment with different concentrations of CPP-G1 peptide, but not CPP-SA peptide, reduced HGS O-GlcNAcylation and PD-L1 expression in a dose-dependent manner, with no apparent effect of cellular O-GlcNAcylation levels (Fig. 7D and SI Appendix, Fig. S15A). It was previously shown that HGS O-GlcNAcylation inhibits EGFR lysosomal degradation. As expected, treatment with CPP-G1 or GFP-G1 reduced EGFR expression, while treatment with the mutants had no apparent effect (SI Appendix, Fig. S15C). To rule out the effect of EGFR expression in the T cell cytotoxicity assays, we restored EGFR expression in the cells treated with CPP-G1 or GFP-G1 (Fig. 7E). We verified that restoration of EGFR expression resulted in similar cell proliferation rates of these cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S15D). Under these conditions, treatment with GFP-G1 or CPP-G1, but not the mutants, significantly enhanced T cell cytotoxic activity in vitro (Fig. 7F). Together, these results indicate that the HGS peptide serves as a competitive and specific inhibitor of HGS O-GlcNAcylation to modulate PD-L1 lysosomal degradation in cells.

Discussion

Cancer cells possess several key hallmarks during development and progression, including deregulated glucose metabolism, and the ability to escape immune surveillance (44, 45). The connection between these two hallmarks in cancer cells is not completely understood. Cancer cells divert a fraction of glucose metabolism into the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, leading to upregulation of protein O-GlcNAcylation. How upregulation of O-GlcNAcylation links to cancer immune evasion remains elusive. In this study, we demonstrate that OGT-mediated O-GlcNAcylation negatively correlates with cancer immunogenicity. O-GlcNAcylation does not directly modify PD-L1, but rather targets the ESCRT-mediated PD-L1 protein intracellular sorting pathway, which eventually blocks PD-L1 lysosomal degradation, causing elevated expression of PD-L1 and suppression of T cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 7G). This mechanistic link between O-GlcNAcylation and PD-L1 expression suggests modulating O-GlcNAcylation as a potential therapeutic target against cancer immune evasion. This notion is further strengthened by our results that OGT inhibition synergizes with PD-L1 mAb therapy to suppress tumor growth in mice. Thus, these findings further extend our understanding of PD-L1 protein regulation in cancer cells.

Upregulation of OGT-mediated O-GlcNAcylation has been demonstrated in different cancer types (46, 47). In silico inference of tumor-infiltrating immune cells revealed that OGT was associated with decreased CD8+ cell population in either total leukocytes or nontumor cells, based on immune deconvolution by CIBERSORT and TIMER, respectively (48). Along with our analysis, some discrepancies between the two deconvolution methods were noticed in the TIMER2.0 database, which may result from the skew of leukocyte population in tumor microenvironment. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting OGT have been developed as a means for suppressing tumor growth in vivo (49, 50). However, as OGT catalyzes glycosylation on numerous protein substrates and OGT is essential for normal physiology, inhibiting OGT likely causes undesired side effects. To overcome this limitation, we designed an alternative strategy that employs short peptides containing the sites of glycosylation to competitively inhibit glycosylation on the protein of interest. In this study, a short peptide containing HGS glycosylation sites was synthesized and delivered into cells to competitively inhibit HGS glycosylation with minimal interference with the total cellular O-GlcNAcylation level. Such treatment led to attenuated PD-L1 expression and enhanced T cell cytotoxicity. This proof-of-concept experiment suggests that specific targeting intracellular protein O-GlcNAcylation can be achieved with desired functional outcomes. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that specific proteins with unique site-specific O-GlcNAcylation govern their biological functions that contribute to cancer development and progression (51–53). This strategy can be readily extended to targeting O-GlcNAcylation on various proteins and likely provides opportunities for designing anticancer therapy.

Methods

Cell Culture and Tumor Tissues.

Cell lines 293T, A549, SW1990, Hepa1-6, B16-F10, HepG2 and SK-Hep1 were all obtained from American Type Cell Culture. All cell lines used in the present study were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and the peritumoral tissues specimens were obtained from the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Ethic Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital authorized use of the tumor specimens in the present study.

TCGA Analyses.

The correlations between OGT mRNA level and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were analyzed by using TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/). Spearman’s rho value was used to evaluate the degree of their correlation. The correlations between OGT mRNA level and T cell-exhaustion related genes in LIHC dataset were analyzed using cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/). Kaplan-Meier plots of the overall survival rates of LIHC and KIRC patients with high and low expression of OGT were analyzed by using GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn). Statistical analyses were performed by the two-tailed log-rank test. All other experimental methods are provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31971212 and 32271331 to W.Y., 32201045 to Q.Z., 82271763 to L.W., 32270746 and 82203247 to L.X.), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LZ21C050001 to W.Y., LZ23C060002 to L.X., and LQ22H160058 to B.L.), the Major Projects of Medicine and Health in Zhejiang Province (WKJ-ZJ-2306), the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (K20220228), and the Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience (210036 to W.Y.).

Author contributions

W.Y. designed research; Q.Z., H.W., S.C., and L.X. performed research; B.L. and L.W. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Q.Z., L.X., W.Y., and L.W. analyzed data; and Q.Z. and W.Y. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Wen Yi, Email: wyi@zju.edu.cn.

Liming Wu, Email: wlm@zju.edu.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. The correlations between OGT mRNA level and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were analyzed by using TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/), based on the RNA-seq datasets derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). The survival analyses of LIHC and KIRC patients were analyzed by using GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn). The correlations between OGT mRNA level and T cell-exhaustion related genes in LIHC dataset were analyzed using cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/), based on the RNA-seq datasets from the TCGA database.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A., Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong W., Gao Y., Wei W., Zhang J., Extracellular and nuclear PD-L1 in modulating cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 7, 837–846 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornepati A. V. R., Vadlamudi R. K., Curiel T. J., Programmed death ligand 1 signals in cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 22, 174–189 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahmer J. R., et al. , Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 366, 2455–2465 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong H., et al. , Tumor-associated B7–H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat. Med. 8, 793–800 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonpavde G., PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as salvage therapy for urothelial carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 376, 1073–1074 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L., Han X., Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: Past, present, and future. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 3384–3391 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demaria O., et al. , Harnessing innate immunity in cancer therapy. Nature 574, 45–56 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharpe A. H., Pauken K. E., The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 153–167 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagchi S., Yuan R., Engleman E. G., Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: Clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 16, 223–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitt J. M., et al. , Resistance mechanisms to immune-checkpoint blockade in cancer: Tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors. Immunity 44, 1255–1269 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P., Hu-Lieskovan S., Wargo J. A., Ribas A., Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168, 707–723 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zerdes I., Matikas A., Bergh J., Rassidakis G. Z., Foukakis T., Genetic, transcriptional and post-translational regulation of the programmed death protein ligand 1 in cancer: Biology and clinical correlat ions. Oncogene 37, 4639–4661 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cristescu R., et al. , Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 362, eaar3593 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim T. K., Vandsemb E. N., Herbst R. S., Chen L., Adaptive immune resistance at the tumour site. Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 21, 529–540 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun C., Mezzadra R., Schumacher T. N., Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint. Immunity 48, 434–452 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cha J. H., Chan L. C., Li C. W., Hsu J. L., Hung M. C., Mechanisms controlling PD-L1 expression in cancer. Mol. Cell 76, 359–370 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellucci R., et al. , Interferon-γ-induced activation of JAK1 and JAK2 suppresses tumor cell susceptibility to NK cells through upregulation of PD-L1 expression. Oncoimmunology 4, e1008824 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wölfle S. J., et al. , PD-L1 expression on tolerogenic APCs is controlled by STAT-3. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 413–424 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H., et al. , ADORA1 inhibition promotes tumor immune evasion by regulating the ATF3 -PD-L1 axis. Cancer Cell 37, 324–339 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casey S. C., et al. , MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science 352, 227–231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bi X.-W., et al. , PD-L1 is upregulated by EBV-driven LMP1 through NF-κB pathway and correlates with poor prognosis in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 9, 109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim S.-O., et al. , Deubiquitination and stabilization of PD-L1 by CSN5. Cancer Cell 30, 925–939 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C. W., et al. , Glycosylation and stabilization of programmed death ligand-1 suppresses T-cell activity. Nat. Commun. 7, 12632 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cha J.-H., et al. , Metformin promotes antitumor immunity via endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation of PD-L1. Mol. Cell 71, 606–620 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao H., et al. , Inhibiting PD-L1 palmitoylation enhances T-cell immune responses against tumours. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 3, 306–317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres C. R., Hart G. W., Topography and polypeptide distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues on the surfaces of intact lymphocytes. Evidence for O-linked GlcNAc. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3308–3317 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart G. W., Housley M. P., Slawson C., Cycling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature 446, 1017–1022 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang X., Qian K., Protein O-GlcNAcylation: Emerging mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 452–465 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haltiwanger R. S., Holt G. D., Hart G. W., Enzymatic addition of O-GlcNAc to nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Identification of a uridine diphospho-N-Acetylglucosamine: Peptide Beta-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 2563–2568 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubas W. A., Frank D. W., Krause M., Hanover J. A., O-linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9316–9324 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrer C. M., Sodi V. L., Reginato M. J., O-GlcNAcylation in cancer biology: Linking metabolism and signaling. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 3282–3294 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma Z., Vosseller K., Cancer metabolism and elevated O-GlcNAc in oncogenic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34457–34465 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Queiroz R. M., Carvalho E., Dias W. B., O-GlcNAcylation: The sweet side of the cancer. Front. Oncol. 4, 132 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu Q., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation promotes pancreatic tumor growth by regulating malate dehydrogenase 1. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 1087–1095 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation of core components of the translation initiation machinery regulates protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7857–7866 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation of MORC2 at threonine 556 by OGT couples TGF-β signali ng to breast cancer progression. Cell Death Differ. 29, 861–873 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burr M. L., et al. , CMTM6 maintains the expression of PD-L1 and regulates anti-tumour immunity. Nature 549, 101–105 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raiborg C., Stenmark H., The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature 458, 445–452 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi H., Mayers J. R., Wang L., Edwardson J. M., Audhya A., Hrs and STAM function synergistically to bind ubiquitin-modified cargoes in vitro. Biophys. J. 108, 76–84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu L., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation regulates epidermal growth factor receptor intracellular trafficking and signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2107453119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolhassani A., Jafarzade B. S., Mardani G., In vitro and in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins using cell penetrating peptides. Peptides 87, 50–63 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soragni A., et al. , A designed inhibitor of p53 aggregation rescues p53 tumor suppression in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer cell 29, 90–103 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavlova N. N., Zhu J., Thompson C. B., The hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab. 34, 355–377 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganapathy-Kanniappan S., Linking tumor glycolysis and immune evasion in cancer: Emerging concepts and therapeutic opportunities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1868, 212–220 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma Z., Vosseller K., O-GlcNAc in cancer biology. Amino Acids 45, 719–733 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slawson C., Hart G. W., O-GlcNAc signalling: Implications for cancer cell biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 678–684 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu B., Liu J. S., Liu X. S., Revisit linear regression-based deconvolution methods for tumor gene expression data. Genome Biol. 18, 127 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma N. S., et al. , O-GlcNAc modification of Sox2 regulates self-renewal in pancreatic cancer by promoting its stability. Theranostics 9, 3410–3424 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohlff C., et al. , A novel, orally administered nucleoside analogue, OGT 719, inhibits the liver invasive growth of a human colorectal tumor, C170HM2. Cancer Res. 59, 1268–1272 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang T., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation of fumarase maintains tumour growth under glucose deficiency. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 833–843 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation destabilizes the active tetrameric PKM2 to promote the Warburg effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 13732–13737 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nie H., et al. , O-GlcNAcylation of PGK1 coordinates glycolysis and TCA cycle to promote tumor growth. Nat. Commun. 11, 36 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. The correlations between OGT mRNA level and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were analyzed by using TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/), based on the RNA-seq datasets derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). The survival analyses of LIHC and KIRC patients were analyzed by using GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn). The correlations between OGT mRNA level and T cell-exhaustion related genes in LIHC dataset were analyzed using cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/), based on the RNA-seq datasets from the TCGA database.