Abstract

Glucocorticoids are generally contraindicated for use in central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) because their use is considered to be an independent risk factor for CSC. There are rare reports regarding the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) combined with CSC. This current case report describes a rare case of a 24-year-old female patient with severely active SLE combined with CSC, whose vision was significantly restored after she was administered 120 mg methylprednisolone intravenously once a day for 3 days. This case report presents the clinical characteristics for the first time in terms of distinguishing between typical CSC and lupus chorioretinopathy. It also provides a review of the relevant literature. In patients with clinically severe active lupus nephritis combined with bilateral lupus chorioretinopathy, timely systemic application of appropriate doses of glucocorticoids is the preferred method to control the primary disease and serious ocular complications.

Keywords: Central serous chorioretinopathy, case report, systemic lupus erythematosus, glucocorticoids, lupus chorioretinopathy

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a connective tissue disease with multisystem involvement.1 Active lupus can lead to the involvement of ocular structures and visual transmission pathways with a variety of clinical manifestations, including dry eye, uveitis, retinal and optic neuropathy,2 but SLE ocular lesions presenting as central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) are very rare.3,4 CSC is a disease of central visual loss caused by choroidal ischaemia and inflammation. CSC is a fundus lesion characterized by localized serous neuroepithelial detachment in and around the macula, with an incidence of approximately 0.004–0.007%, which tends to occur in young and middle-aged men; and 60–80% of patients have unilateral eye involvement, with 30–45% of patients having a poor visual prognosis.5 The use of glucocorticoids is considered to be an independent risk factor for CSC and it is a relative contraindication to CSC treatment.6 Identifying the correlation between CSC and lupus activity is crucial to the diagnosis and treatment of SLE combined with CSC, and it has rarely been reported.3,4 The results of glucocorticoid therapy for a patient with SLE combined with CSC are presented below.

Case report

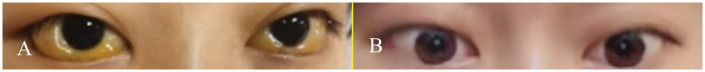

In October 2020, a 24-year-old female patient was admitted to the Department of Nephrology, Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital, First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China with ‘bilateral eyelid oedema and decreased vision for 3 days’. Clinical examination upon admission recorded the following: blood pressure, 110/73 mmHg; bilateral eyelid oedema; severe bilateral bulbar conjunctiva oedema with congestion and prominence; yellow hyperplastic tissue in the cornea; swelling in the left upper lid; bilateral protrusion of the eyeballs; difficulty in closing the eyes (Figure 1); blurred vision in both eyes; no oedema in both lower limbs; and no other abnormalities.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the appearance of the eyes of a 24-year-old female patient that presented with bilateral eyelid oedema and decreased vision for 3 days before (a) and after (b) treatment. The colour version of this figure is available at: http://imr.sagepub.com.

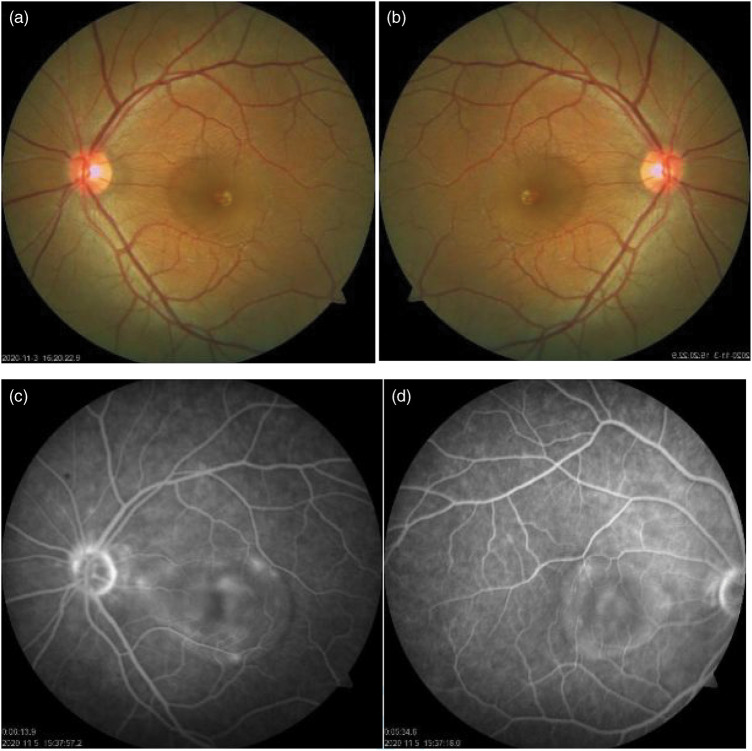

Table 1 displays the results of the laboratory tests performed upon admission. Chest computed tomography imaging revealed moderate bilateral pleural effusion. Visual acuity in both eyes was as follows: 0.05 in right, 0.05 in left; right IOP 27.5 mmHg, 28.5 mmHg in left. Fundus photography (Figure 2) and bilateral fluorescence imaging suggested CSC in both eyes. The orbital magnetic resonance imaging revealed bilateral swelling of the eyelids and periorbital soft tissues, as well as a slightly thickened wall of the orbital ring. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed that the neuroepithelial layer of the macula was detached in both eyes. The following were considered for a diagnosis of the cause of the bilateral macular lesions: CSC or secondary glaucoma in both eyes. A renal biopsy revealed the presence of mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis (class II).

Table 1.

Laboratory test results at hospital admission of a 24-year-old female patient that presented with bilateral eyelid oedema and decreased vision for 3 days.

| Parameter | Patient value | Normal reference range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cells count, ×109/l | 6.04 | 3.50–9.50 |

| Platelet count, ×109/l | 229 | 125–350 |

| Haemoglobin, g/l | 113↓ | 115–150 |

| Urine protein | 1+ | – |

| Urine red blood cell count/ high power field | 3.6 | 0–4 |

| Urine white blood cell count/high power field | 13.7↑ | 0–5 |

| 24-h urine total protein, mg | 674.69↑ | 0–150 |

| Anti-dsDNA | 1:40↑ | <1:10 |

| ANA | 1:1000↑ | <1:100 |

| Anti-Sm | + | – |

| p-ANCA | 1:40 | <1:10 |

| c-ANCA | <1:10 | <1:10 |

| MPO | <1:10 | <1:10 |

| PR3 | <1:10 | <1:10 |

| Complement C3, g/l | 0.29↓ | 0.9–1.8 |

| Complement C4, g/l | 0.008↓ | 0.1–0.4 |

| Serum creatinine, mmol/l | 59.9 | 46–92 |

| Albumin, g/l | 29.7↓ | 40–55 |

| CA125, U/ml | 39.2↑ | <35.0 |

dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ANA, antinuclear antibody; Sm, Smith; p-ANCA, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; c-ANCA, cytosolic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PR3, proteinase-3; CA, cancer antigen.

Figure 2.

Fundus examination results of a 24-year-old female patient that presented with bilateral eyelid oedema and decreased vision for 3 days: (a & b) colour photographs of the left and right eyes showing a 2 papillary diameter (PD) size neurocortical detachment and pigment disorder in the macular region of both eyes; (c & d) fluorescein angiography of the left and right eyes, respectively, showing punctate retinal pigment epithelium leakage in the macular area of both eyes and fluorescence accumulation of approximately 2PD size under the neuroepithelial layer. The colour version of this figure is available at: http://imr.sagepub.com.

The final diagnosis was as follows: SLE; lupus nephritis; lupus-related ocular lesions in both eyes: CSC; SLEDAI Score 21 (visual 8, proteinuria 4, alopecia 2, pleural effusion 2, hypocomplementation 2, anti-ds DNA antibody 2, leukocyte drop 1) indicating active lupus. Because glucocorticoids are contraindicated in the treatment of CSC, the patient was administered 20 mg intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) once a day for 3 days, 40 mg methylprednisolone intravenous (i.v.) once a day for 5 days and 500 mg mycophenolate oral twice a day for 3 days, but the oedema and vision loss in both eyes did not improve. Following that, methylprednisolone was increased to 120 mg i.v. once a day for 3 consecutive days and the patient's eyelid oedema and visual acuity improved significantly. Given the risk of aggravating CSC with glucocorticoid use, the methylprednisolone dose was reduced as soon as her vision recovered and the immunosuppression was achieved using 0.8 g cyclophosphamide i.v. to induce remission. OCT was repeated 1 week later and the retinal neuroepithelial layer detachment in the maculas of both eyes was reduced. The patient's swelling and visual acuity were both relieved. By telephone follow-up 1 year later, the patient reported complete recovery of visual acuity with no recurrence.

The patient provided written informed consent for all treatment. The patient and her family provided written informed consent for publication of her anonymized data in this current case report. Approval for publication was provided by the Ethics Review Committee of Shenzhen Second People's Hospital (no. 20220616003). Reporting of this case report conforms to the CARE guidelines.7

Discussion

In the current case, a complete renal biopsy revealed class 2 lupus nephritis in a young female with acute onset, bilateral eyelids, ocular oedema and significant vision loss. She had severe lupus activity and an ophthalmic examination revealed that she had CSC. Glucocorticoids are not recommended for CSC treatment, so she was initially administered 20 mg IVIG once a day for 3 days and 40 mg methylprednisolone i.v. once a day for 5 days, but her vision loss did not improve. A previous report of CSC in a patient with SLE caused by glucocorticoid therapy demonstrated significantly improved visual acuity after glucocorticoid withdrawal.8 The use of glucocorticoids is particularly contraindicated at this time. Determining whether the current patient's CSC was an ocular manifestation of lupus was critical.

Previous research has demonstrated that being male, systemic steroid use and pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of CSC.5,8 Glucocorticoid use, with an odds ratio of 37:1, is the most important risk factor for CSC and it is also strongly associated with CSC recurrence.9,10 Lupus combined with CSC is extremely rare, with only approximately 40 related cases reported as of 2018.11 The pathogenesis of lupus chorioretinopathy is thought to be related to immune complex deposition in the choroid and the formation of thrombotic microangiopathy by autoantibodies against the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which causes choroidal hypoperfusion, RPE cell damage and fluid leakage into the subretinal space.12 Approximately 68% of patients with lupus combined with chorioretinopathy have active lupus with bilateral ocular involvement, 64% have combined renal impairment and 36% have central nervous system involvement; when glucocorticoid therapy can lead to complete resolution of ophthalmic symptoms in these patients.12,13 The characteristics of lupus chorioretinopathy and typical CSC are shown in Table 2.13 In addition, this current patient was positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), but negative for myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase-3 (PR3) antigens; and she did not have the renal pathological manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis, such as fibrin necrosis or crescent formation. Therefore, the p-ANCA positivity observed in the current patient was probably caused by an autoimmune disorder and should not be considered to be a complication of vasculitis. Previous reports have also found p-ANCA positivity in some patients with chronic inflammation, infection and autoimmune diseases.14 Patients may have p-ANCA positivity because of the presence of antinuclear antibodies.14 If the MPO or PR3 antigens are negative, then being p-ANCA or c-ANCA positive is of no clinical significance.14

Table 2.

The characteristics of lupus chorioretinopathy and typical central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC).

| Characteristic | Lupus chorioretinopathy | Glucocorticoid-related CSC |

|---|---|---|

| The affected population | Female | Male |

| Risk factors | Active lupus, 64% have combined renal impairment, 36% have nervous system impairment | Glucocorticoid use; pregnancy |

| Clinical manifestations | Acute onset; bilateral eye involvement; severe vision loss | Acute onset; unilateral eyes; painless blurred vision and visual distortion |

| Possible pathological mechanisms | Immune complexes deposited in the choroidal veins lead to hypoperfusion retinopathy | Serous separation of the sensory nerve retina in the macular region due to choroidal ischaemia and inflammation leading to fluid exudation |

| Examination of fluorescein fundus angiography | Focal hyperfluorescent spots caused by defects in the retinal pigment epithelium | 70–80% show a dot-enlarged type, which expands to the periphery centred on the point of dye leakage |

| Treatment | Glucocorticoid and aggressive systemic medical therapy | Hormone withdrawal; acetazolamide; laser therapy |

| Prognosis | Vision is restored in 82% of patients | 60–80% of patients recover within 3 months without any treatment |

Given that the current patient was female, had no prior history of glucocorticoid use, both eyes were involved and the bilateral fluorescence angiography demonstrated punctate RPE leakage in the macula of both eyes, in addition to the presence of severe lupus activity combined with renal damage, her diagnosis was more consistent with lupus chorioretinopathy. There was no doubt that the patient had an underlying immunoregulatory dysfunction. Once the SLE was under control, the patient's retinopathy and choroidal lesions disappeared. She received 120 mg methylprednisolone i.v. once a day for 3 days and the lupus disease was controlled. The patient's vision was significantly improved, confirming that the patient had lupus choroidopathy.

In conclusion, this current case report described the rare case of a young woman with a severely active lupus nephritis combined with CSC. It also summarized some of the clinical characteristics for the first time with regard to distinguishing lupus chorioretinopathy from the typical CSC, which is a contraindication of glucocorticoids. Despite the fact that glucocorticoids are contraindicated in CSC, for women with lupus with renal impairment and rapidly declining vision in both eyes who have not previously received glucocorticoid therapy, the systemic application of appropriate doses of glucocorticoids is the preferred method of controlling the primary disease and serious ocular complications. Bilateral lupus chorioretinopathy, a rare sign of active SLE, needs to be better understood by rheumatologists, nephrologists and ophthalmologists.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605231163716 for A case report of systemic lupus erythematosus combined with central serous chorioretinopathy treated with glucocorticoids by Qingqing Rao, Ming Ku and Qijun Wan in Journal of International Medical Research

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient for agreeing to publish this case and the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University for providing ophthalmic examination results and follow-up treatment.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the following grants: Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (Project number: SZXK009); Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (Project number: SZSM201512004); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project number: 81900639); Research Program of the Shenzhen Science and Technology Project number: R&D Fund (Project number: JCYJ20190806162807125); and Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (Project number: SZXK009).

ORCID iD: Qijun Wan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1304-1333

References

- 1.Merrill JT, Buyon JP, Utset T. A 2014 update on the management of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44: e1–e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shoughy SS, Tabbara KF. Ocular findings in systemic lupus erythematosus. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2016; 30: 117–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conigliaro P, Cesareo M, Chimenti MS, et al. Take a look at the eyes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A novel point of view. Autoimmun Rev 2019; 18: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turk MA, Hayworth JL, Nevskaya T, et al. Ocular Manifestations in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Connective Tissue Disease, and Vasculitis: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2021; 48: 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rijssen TJ, van Dijk EHC, Yzer S, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy: Towards an evidence-based treatment guideline. Prog Retin Eye Res 2019; 73: 100770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khng CG, Yap EY, Au-Eong KG, et al. Central serous retinopathy complicating systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000; 28: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Headache 2013; 53: 1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato H, Ito S, Nagai S, et al. Atypical severe central serous chorioretinopathy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus improved with a rapid reduction in glucocorticoid. Mod Rheumatol 2013; 23: 172–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haimovici R, Koh S, Gagnon DR, et al. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: a case–control study. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rim TH, Kim HS, Kwak J, et al. Association of Corticosteroid Use With Incidence of Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in South Korea. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018; 136: 1164–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasanreisoglu M, Gulpinar Ikiz GD, Kucuk H, et al. Acute lupus choroidopathy: multimodal imaging and differential diagnosis from central serous chorioretinopathy. Int Ophthalmol 2018; 38: 369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dammacco R. Systemic lupus erythematosus and ocular involvement: an overview. Clin Exp Med 2018; 18: 135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edouard S, Douat J, Sailler L, et al. Bilateral choroidopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2011; 20: 1209–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benitez del Castillo J, Castillo A, Fernandez-Cruz A, et al. Persistent choroidopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Doc Ophthalmol 1994; 88: 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605231163716 for A case report of systemic lupus erythematosus combined with central serous chorioretinopathy treated with glucocorticoids by Qingqing Rao, Ming Ku and Qijun Wan in Journal of International Medical Research