Abstract

Primary biliary melanoma arises from proliferating melanocytes in the mucosal surface of the bile duct and is extremely rare. Since the vast majority of biliary melanomas represent metastases of cutaneous origin, accurate preoperative diagnosis of melanoma and exclusion of other primary sources are vital in cases involving primary lesions. Although melanomas with pigmented cells have typical signal characteristics, obtaining a non-invasive pre-treatment diagnosis remains difficult, due to their low incidence. Here, the case of a 61-year-old male Asian patient who presented with upper quadrant abdominal pain, swelling and jaundice for 2 weeks, and who was diagnosed with primary biliary melanoma following extensive preoperative blood analyses, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is described. Post-resection immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis and the patient received six chemotherapy cycles of temozolomide and cisplatin, however, progression of multiple liver metastases was observed at the 18-month follow-up CT. The patient continued with pembrolizumab and died 17 months later. The present case of primary biliary melanoma is the first reported diagnosis based on typical MRI features and the exhaustive exclusion of a separate primary origin.

Keywords: Bile duct, malignant melanoma, magnetic resonance imaging, immunohistochemistry, jaundice, imaging features.

Introduction

Melanoma arises from proliferating melanocytes, a heterogeneous group of cells that are derived from the embryonic neural crest and specialized in synthesizing melanin.1 The overwhelming majority of melanocytes are restricted to cutaneous sites, with small numbers scattered on mucous surfaces (nasal, oropharyngeal, respiratory, alimentary and genitourinary tract), the ocular region (uvea and retina) and the leptomeninges.2 Based on the anatomic location, melanomas are clinically subdivided into several subtypes: cutaneous, acral, mucosal, uveal, and unknown.3 Mucosal melanoma is the rarest subtype, occupying only 0.8–3.7% of melanoma cases.4 Primary biliary melanoma arises from melanocytes in mucosal tissues lining the bile duct and is extremely rare.5

Primary biliary melanoma is a tumour with high-risk for recurrence and poor prognosis, thus, early diagnosis and appropriate therapies are urgently required. Previous studies have revealed that melanin synthesized by melanocytes may shorten T1 and T2 relaxation time, forming a distinctive appearance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).6,7 This appearance combined with preoperative whole-body screening renders non-invasive diagnosis of primary biliary melanoma possible, which plays a critical role in assisting the therapeutic regimen formulation. Nevertheless, to date, there are no reports of a case that has been diagnosed prior to treatment, possibly due to the rarity of the disease. Here, the case of a patient with suggested preoperative diagnosis of primary biliary melanoma, evidenced by preoperative typical MRI features and whole-body screening, together with imaging features, histological characteristics, immunohistochemical profile and curative procedure, is described.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University and written informed consent was obtained from the patient. The reporting of this study conforms to CARE guidelines.8

Case presentation

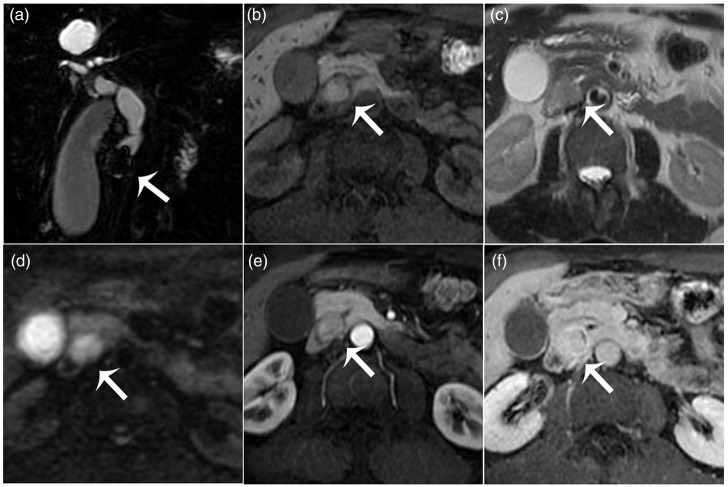

A 61-year-old Asian man (without any prior disease, special medication or drug allergy, or adverse life history) was admitted to the Gastrointestinal Department of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, Jiangsu Province, China in July 2015, with upper quadrant abdominal swelling, pain and jaundice for approximately 2 weeks. On admission, physical examination of the abdomen revealed mild tenderness in the right upper quadrant, without rebound tenderness. Results of blood analysis indicated cholestasis and hepatic cell injury, evidenced by elevated total bilirubin (319.2 μmol/L), direct bilirubin (231.2 μmol/L), total bile acid (115.6 μmol/L), alkaline phosphatase (436 U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (1509 U/L), representative of cholestasis; and raised aspartate aminotransferase (124 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase (307 U/L), reflective of hepatic cell injury. The value of tumour marker serum ferritin was elevated, at 860.7 ng/ml (normal range, 21.80–274.66), but values of other biomarkers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (1.9 ng/ml) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (2.0 U/ml), were within normal range. Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a quasi-circular nodule of possible biliary origin, with slightly hypodense appearance on plain scan compared with adjacent muscle (Figure 1a), marked and mild heterogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 1b), and uniform slightly reduced enhancement in the delayed phase (Figure 1c). The lesion was about 2.5 cm in diameter and located in the distal common bile duct, causing extrahepatic biliary dilatation (Figure 1d). On MRI (Figure 2), the MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) image (Figure 2a) clearly showed a space-occupying lesion with smooth margin in the distal common bile duct causing biliary dilatation. The lesion was hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging without signal reduction when fat was suppressed (Figure 2b), slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging (Figure 2c), and hyperintense on diffusion-weighted imaging (Figure 2d) compared with the adjacent muscular tissue. After intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast agent, the lesion demonstrated slight heterogeneous enhancement during the arterial phase (Figure 2e) and progressive and more homogeneous enhancement surrounded by discontinuous enhanced biliary wall during the equilibrium phase (Figure 2f). Based on the particular signal characteristics of the entity, a senior diagnostician (JW) expressed a high suspicion of a melanoma. To rule out an alternative primary site, detailed ophthalmological, otorhinolaryngologic and dermatological examinations with CT enhancement of the neck, chest and pelvis were performed, and no other suspicious lesion was revealed. MRI did not detect any aberrant cerebral or ocular entity, and no mucosal lesions suggestive of melanoma were revealed by gastrointestinal endoscopy. The patient reported no previous sunburns, prolonged sun exposure, atypical nevus, or excised skin cancer, and no family history of skin cancers.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) images from a 61-year-old Asian male patient diagnosed with primary biliary melanoma: (a) CT plain scan image showing a round, slightly hypodense lesion (arrow) in the common bile duct; (b and c) arterial and delayed-phase CT scan images after injection of contrast agent, demonstrating arterial marked and mild heterogeneous enhancement, and uniform slightly reduced later enhancement; and (d) coronal reconstruction image showing a distal biliary lesion (arrow) causing extrahepatic bile duct dilatation.

Figure 2.

Axial magnetic resonance images from a 61-year old male Asian patient diagnosed with primary biliary melanoma: (a) magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image clearly showing a lesion (arrow) with smooth margin in the distal common bile duct causing biliary dilatation; (b) a T1-weighted fat-suppressed sequence image showing a biliary lesion (arrow) that is hyperintense versus the adjacent muscle; (c) a T2-weighted image showing the lesion (arrow) as slightly hyperintense versus the adjacent muscle; (d) diffusion weighted image showing the lesion (arrow) as hyperintense versus the adjacent muscle; and (e and f) arterial and delayed-phase dynamic contrast-enhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted images demonstrating arterial slight heterogeneous enhancement and later progressive and more homogeneous enhancement.

At 5 days after admission, the patient provided written informed consent to surgery and pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed. The digestive tract was reconstructed using Child’s method, before which the patient had undergone percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage to reduce jaundice. The operation lasted 3 h with approximately 400 ml of blood loss. The tumour was completely resected with free surgical margins, and no evidence of regional lymph node metastasis was found in the six intraoperatively retrieved nodes. After surgery, the patient had an uneventful postoperative course. Macrography of the postoperative specimen disclosed a solitary, polypoid, 3 × 2.5-cm, firm, tan-red, pedunculated lesion located in the bile duct. Microscopically (Figure 3a), the lesion consisted of tumour cells of different sizes and dysplasia, with large, hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei, and scattered pigmented cells. Immunohistochemical examination demonstrated tumour positivity for S100 protein, premelanosome protein (HMB-45) and melan-A (Figure 3b, c, and d), and negativity for pan cytokeratin (CK10, CK14, CK15, CK16, CK19 and Keratin 2; AE1/AE3 antibody clone), keratin 18 (CK18), synapsin (Syn), chromogranin A (CgA), leukocyte common antigen (LCA), desmin and alpha-smooth muscle actin. Supported by the histopathologic results and preoperative exhaustive exclusion of an alternative primary origin, a diagnosis of primary biliary melanoma was confirmed. The patient declined genetic analysis.

Figure 3.

Representative tumour histopathology photomicrographs from a 61-year old male Asian patient diagnosed with primary biliary melanoma: (a) haematoxylin and eosin-stained section showing pleomorphic malignant cells and some with pigmentation; (b) strong and diffuse positive staining for S-100 protein; (c) strong and diffuse positive staining for HMB-45; and (d) strong and diffuse positive staining for melan-A (all original magnification, × 200).

Postoperative chemotherapy was initiated, comprising six cycles of 200 mg/m2/day temozolomide (orally, days 1–5) plus 25 mg/m2/day cisplatin (intravenously, days 1–3), every 21 days. Follow-up CT re-examination 18 months later demonstrated progression of multiple liver metastases. From that time on, the patient was prescribed 2 mg/kg pembrolizumab, intravenously, every 3 weeks until the time of death, 17 months later.

Discussion

Primary melanoma in the common bile duct, first described by Zaide in 1963,9 is particularly rare. A review of the published literature searched in PubMed, using a series of search strings (‘biliary’ OR ‘bile duct’ AND ‘primary’ AND ‘melanoma’) with no date limit, revealed that only 15 cases, including the present case, have been reported to date (summarised in Table 1).10–21 This tumour type appears to have a predilection for adult males (male: female ratio, 13:2) and a mean patient age at presentation of 47.9 years (range, 26–67; Table 1). The predominant clinical symptom was found to be jaundice, with the next most commonly reported symptoms being abdominal pain and dark urine. Almost all of the cases displayed elevated serum total bilirubin, representing cholestasis, and for some cases, increased alanine aminotransferase was reported, sensitively reflecting hepatic cell injury.

Table 1.

Summary of previously published reports of primary biliary melanoma.

| Publication | Age/sex | Symptoms | Location | Therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaide, 19639 | 47/male | Jaundice | Proximal common hepatic duct | Cholecystectomy and resection of common bile duct | Disease-free survival 6 months |

| Carstens et al., 198610 | 30/male | Indigestion, abdominal pain, and jaundice | Distal common bile duct | Whipple resection | Progressive disease with death 6 months after presentation |

| Deugnier et al., 199111 | 34/female | Abdominal pain and jaundice | Left hepatic duct | Left hepatectomy with partial right hepatic and common bile duct resection | Progressive disease with death 1.5 years after presentation |

| Zhang et al., 199112 | 58/male | Jaundice | Common bile duct and gallbladder | Whipple resection | Disease-free 2 years after presentation |

| Washburn et al., 199513 | 45/male | Month of itching and dark urine | Distal common bile duct and ampulla | Whipple resection | Disease-free survival 6 years after presentation |

| Washburn et al., 199513 | 43/male | Lethargy, itching, and dark urine | Common hepatic duct and right hepatic duct | Right hepatic lobectomy and cholecystectomy | Alive 11 months after presentation |

| Wagner et al., 200014 | 48/male | Right upper quadrant pain and jaundice | Common bile duct | Whipple resection | Progressive disease with death 9 months after diagnosis |

| González et al., 200115 | 67/female | Jaundice and abdominal pain | Proximal common hepatic duct | Extrahepatic bile duct resection | Disease-free survival 17 years after presentation |

| Bejarano et al., 200516 | 47/male | Jaundice and dark urine | Distal common bile duct | No surgery performed due to metastatic disease | Died 2 years after presentation |

| Hoshi et al., 200617 | 55/male | Jaundice | Common hepatic duct | Bile duct resection | Died 4 months after presentation |

| Agrawal et al., 201018 | 26/male | Abdominal pain | Intrahepatic biliary tract | Hepatic segmentectomy (II–III) | Disease-free survival 72 months after presentation |

| Smith et al., 201219 | 55/male | Jaundice | Distal common bile duct | Whipple resection | Disease-free survival 12 months after presentation |

| Addepally et al., 201620 | 52/male | Jaundice and abdominal pain | Common hepatic duct | Best care support | Died 3 months after presentation |

| Cameselle-García et al., 201921 | 51/male | Jaundice | Common hepatic duct | Cholecystectomy and common hepatic duct resection | Died 31 months after presentation |

| Present case | 61/male | Upper quadrant abdominal pain and jaundice | Distal common bile duct | Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | Died 35 months after diagnosis |

Because the vast majority of biliary melanomas represent metastases from cutaneous origin, suggestive diagnosis of melanoma and pretreatment exclusion of a different primary source is extremely significant for primary entities, particularly in patients suitable for thorough resection, as in the present case. CT is the preferred approach with the advantage of rapidly imaging multiple organs and systems, directly visualizing enlarged lymph nodes, estimating tumour bulk and better characterizing its relationship with neighbouring structures. Nevertheless, CT images do not enable further analysis of the distinct component of the melanoma. MRI may sometimes provide a suggestive non-invasive diagnosis, relying on paramagnetic metal bound to melanin, which has the characteristic of influencing T1 and T2 relaxation time and contributes to the typical hyperintensity on T1-weighted imaging and hypointensity on T2-weighted imaging.22 In the present case, since the entity appeared uniformly hyperintense in the T1 fat-suppressed sequence compared with adjacent muscle, it was first necessary to identify six elements, including gadolinium contrast agents, haemoglobin degradation products, fats, high-protein substances, melanin and minerals. Fat-suppressed images may be explicit in the case of fatty lesions. The possibility of the most common cholelithiasis, haemoglobin degradation products, or high-protein substances may be ruled out by diffusion-weighted imaging and contrast enhancement. On the basis of the exclusion method, the lesion would likely be a melanin-containing tumour, including melanoma or pigmented perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa). These two tumours rarely occur in the common bile duct, and PEComa is even rarer. In addition, differential diagnosis of the imaging manifestations of these two tumours is not well known, however, PEComa tends to display a female predominance of 7:1, and haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining usually reveals epithelioid cells arranged in a nested, alveolar, or trabecular pattern near blood vessels, without scattered pigmented cells.23 Importantly, a suggestive diagnosis of melanoma is helpful for clinical treatment. A mass-forming type of cholangiocarcinoma is another common tumour that needs to be distinguished. However, not only the signal intensity of the present tumour, but also the pattern of enhancement, was inconsistent, with mainly moderate peripheral enhancement followed by progressive centripetal enhancement. It is relatively easy to note that the hypersignal on T1-weighted imaging was not particularly pronounced in the present case, as it appeared isointense compared with the pancreas. Melanin content is shown to correlate with hyperintensity on T1-weighted imaging, meaning that the signal intensity of melanoma may be determined by the amount of melanin within the lesion.24 We hypothesized that there was not much melanin in the present case, which would explain why the T2-weighted imaging showed a slightly higher signal rather than the typical low signal. Based on the pre-treatment suggestive diagnosis, exhaustive screening with particular attention to the skin, eyes, anorectum and vagina, and general radiological examination, could be arranged to avoid the omission of another primary melanocytic cancer and contribute to formulating an optimal therapeutic regimen.

The diagnosis of melanoma was eventually verified by histopathological outcomes including H&E staining and immumohistochemical staining. Melanomas with unique melanin-pigmented cells are typically pathological manifestations, but ancillary immunohistochemical studies are still needed to obtain the final diagnosis. Three melanocytic differentiation markers, including S100 protein, a 21 kDa acidic calcium-binding protein, HMB-45, a marker of the cytoplasmic premelanosomal glycoprotein gp100, and melan-A, an antigenic target of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, are currently the most useful immunomarkers to identify melanocytes.25 The most sensitive marker, S100 protein, has demonstrated a sensitivity of >89% in diagnoses of melanoma, but a relatively low specificity of 75–87%.26 Melan-A has shown a sensitivity of 75–92% and a specificity of 95–100% for melanoma, while HMB-45 displays a sensitivity of 69–93% and a specificity of 56–100%.26 Meanwhile, negativity for pan cytokeratin, CK18, Syn, CgA, LCA, desmin and alpha-smooth muscle actin ruled out other tumours in the present case, and further confirmed the diagnosis of melanoma.

The primary and metastatic entities of melanoma share consistent pathological features. Several characteristics to separate primary from metastatic melanoma in the bile duct have been previously summarised.18,19 The most important characteristic is the absence of an identifiable primary origin, which requires a thorough exclusion of current, or history of, pigmented lesions. Secondly, the majority of primary biliary melanomas demonstrate common morphological characteristics of solitary, polypoid and intraluminal mass consistent with the present case, whereas metastatic tumours are more likely to appear as multiple, multifocal and flattened lesions. Finally, some investigators consider that the most essential histologic characteristic to distinguish a primary entity from a metastatic one is a junctional component,19 meaning the presence of microscopic clustered melanocytes at the in-situ mucosal–submucosal junction. A definitive in-situ junctional component was not identified in the present case, perhaps due to a sampling error, which may have prevented the identification of an in-situ component. However, junctional components have been reported in definitive cases of metastatic melanoma, because of neoplastic intraepithelial extendedness.27

Although there is no established standard of care for primary biliary melanoma, radical surgery is recommended in those patients with a resectable entity and good status, such as in the present case. In unresectable or advanced cases, biliary drainage and immunotherapy should be adopted. Targeted therapy against KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase-activating molecules is a recently emerging therapeutic strategy that has shown promise.28 The prognosis of primary biliary melanoma remains poor, but it is difficult to ascertain a concrete range of survival duration due to low incidence rate and lack of long-term follow-up. The present patient survived 35 months after surgical resection, so we speculate that long-term survival is possible if surgical resection is achieved.

Conclusion

In summary, a suggestive non-invasive diagnosis may be obtained in cases of melanin-containing biliary melanomas, depending on their typical MRI signal characteristics. Typical pigmented tumour cells and appropriate immunohistochemical stain may certify the diagnosis. Tumour morphology and exclusion of a separate origin may provide clues to exclude metastatic melanoma.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Juan Wu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7260-6373

Data availability statement

All data supporting this study are presented within the article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xinhong Wang: Image analysis, Writing-Original Draft. Xiaofei Deng: Methodology, Writing-Editing. Zheng Shu: Conceptualization, Writing-Editing. Juan Wu: Supervision, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

References

- 1.Jenkins RW, Fisher DE. Treatment of advanced melanoma in 2020 and beyond. J Invest Dermatol 2021; 141: 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tapia Rico G, Yong CH, Herrera Gómez RG. Adjuvant systemic treatment for high-risk resected non-cutaneous melanomas: what is the evidence? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021; 167: 103503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou Z, Ou Q, Ren Y, et al. Distinct genomic traits of acral and mucosal melanomas revealed by targeted mutational profiling. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2020; 33: 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yde SS, Sjoegren P, Heje M, et al. Mucosal melanoma: a literature review. Curr Oncol Rep 2018; 20: 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spencer KR, Mehnert JM. Mucosal melanoma: epidemiology, biology and treatment. Cancer Treat Res 2016; 167: 295–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawaguchi M, Kato H, Tomita H, et al. MR imaging findings for differentiating cutaneous malignant melanoma from squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Radiol 2020; 132: 109212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foti PV, Travali M, Farina R, et al. Diagnostic methods and therapeutic options of uveal melanoma with emphasis on MR imaging–Part I: MR imaging with pathologic correlation and technical considerations. Insights Imaging 2021; 12: 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. ; CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Headache 2013; 53: 1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaide EC. Malignant melanoma of the choledochus. Arq Oncol 1963; 5: 254–255 [In Portuguese]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carstens HB, Ghazi C, Carnighan RH, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the common bile duct. Hum Pathol 1986; 17: 1282–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deugnier Y, Turlin B, Léhry D, et al. Malignant melanoma of the hepatic and common bile ducts. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991; 115: 915–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang ZD, Myles J, Pai RP, et al. Malignant melanoma of the biliary tract: a case report. Surgery 1991; 109: 323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washburn WK, Noda S, Lewis WD, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the biliary tract. Liver Transpl Surg 1995; 1: 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner MS, Shoup M, Pickleman J, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the common bile duct: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124: 419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González QH, Medina-Franco H, Aldrete JS. Melanoma of the bile ducts. Report of a case and review of the literature. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2001; 66: 150–152 [In Spanish, English abstract]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bejarano González N, Garcia Moforte N, Darnell Martin A, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the common bile duct: a case report and literature review. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 28: 382–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshi K, Saito Y, Aznai R, et al. A case of bile duct malignant melanoma. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg 2006; 39: 317–322 [In Japanese, English abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal D, Tannous GC, Chak A. Primary malignant melanoma of the hepatic duct: a case report. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 845–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith NE, Taube JM, Warczynski TM, et al. Primary biliary tract melanoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2012; 3: 441–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Addepally NS, Klair JS, Lai K, et al. Primary bile duct melanoma causing obstructive jaundice. ACG Case Rep J 2016; 3: e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameselle-García S, Pérez JLF, Areses MC, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the biliary tract: a case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7: 2302–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barat M, Guegan-Bart S, Cottereau AS, et al. CT, MRI and PET/CT features of abdominal manifestations of cutaneous melanoma: a review of current concepts in the era of tumor‐specific therapies. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021; 46: 2219–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto T, Sasaki T, Takahashi Y, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the cystic duct. Clin J Gastroenterol 2023; 16: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramtohul T, Ait Rais K, Gardrat S, et al. Prognostic implications of MRI melanin quantification and cytogenetic abnormalities in liver metastases of uveal melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13: 2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35: 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charifa A, Zhang X. Morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics of anorectal melanoma. Int J Surg Pathol 2018; 26: 725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adrian S, Clemens C, Elisabeth SW, et al. Clinicohistopathological characteristics of malignant melanoma in the gall bladder: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pathol 2018; 2018: 6471923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldemberg DC, Thuler LCS, De Melo AC. An update on mucosal melanoma: future directions. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2019; 27: 11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study are presented within the article.