Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to examine the trend and factors associated with smoking marijuana from a hookah device among US adults.

Methods:

Data were drawn from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, an ongoing nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of the US population. Adult respondents who self-reported ever smoking marijuana from a hookah at Wave 5 (2018-19, N=34,279 US adults) were included in the multivariable analysis. Trend analysis also was conducted using National Cancer Institute JoinPoint software from 2015 to 2019.

Results:

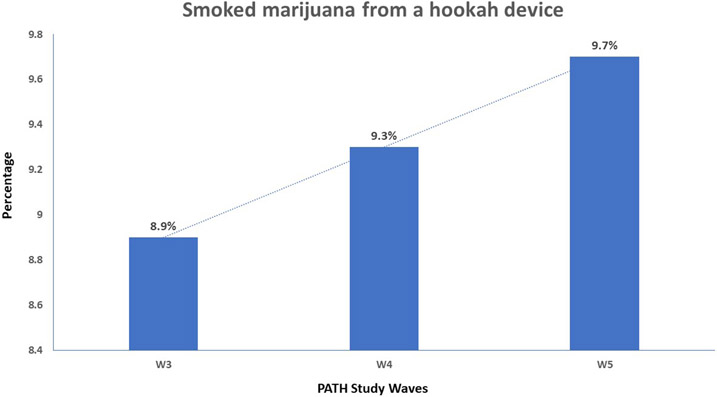

In 2018-19, an estimated 23.6 million (9.7%) US adults reported ever smoking marijuana from a hookah. Trend analysis showed the increasing prevalence of using marijuana from a hookah device from Wave 3 (8.9%) to Wave 5 (9.7%; time trend p=.007). Adults aged 25-44 years old (vs.18-24;13%, vs. 9%), whites (vs. Black;11%vs.9%), and lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB vs. straight;17% vs. 9%) were more likely to report ever smoking marijuana from a hookah (ps<.05). Former and current users (vs. never users) of e-cigarettes (19% and 25% vs. 5%), cigarettes (11% and 21% vs. 2%), cigars (17% and 27% vs. 3%), and pipes(21% and 33% vs. 7%) and past 30-day blunt users (vs.non-users;39% vs. 9%) were more likely to ever smoke marijuana from a hookah (ps<.05). Pregnant women (vs non-pregnant;12.8% vs. 8.6%; p=0.03) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah.

Conclusions:

Smoking marijuana from a hookah device is prevalent among young adults in the US, especially among vulnerable populations, and has increased significantly from 2015-2019.

Keywords: Marijuana, Hookah, Tobacco, Smoking, Adults, United States

INTRODUCTION

Cannabis—colloquially known as marijuana, weed, pot, or dope—is the most commonly used federally illegal drug in the United States (US) (SAMHSA, 2021). In 2020, an estimated 32.8 million Americans aged 12 or older reported using marijuana in the past month, with 14.2 million people having a marijuana use disorder in the past year (SAMHSA, 2021). Marijuana use is gaining higher public health significance due to its legalization for medicinal and recreational purposes in different US states. Moreover, marijuana use has adverse health consequences, including cognitive impairment (e.g., short-term memory impairment and slowness of learning) (Dellazizzo et al., 2022; Meier et al., 2012; NASEM, 2017), addiction (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011), mental health problems (NASEM, 2017; Volkow et al., 2016), impaired immune response (Maggirwar and Khalsa, 2021), impaired driving (Hollenbeck and Uetake, 2021), possible adverse effects on heart function (NASEM, 2017; Rumalla et al., 2016), adverse neonatal outcomes (Crume et al., 2018), and respiratory damages (NASEM, 2017; Tan et al., 2009).

Although marijuana use is federally prohibited, medical marijuana is legal in some form in 37 states, the District of Columbia (DC), Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. Out of the 37 states,19 states including DC and Guam legalized recreational marijuana for adults as of May 27, 2022 (NCSL, 2021; ProCon.org, 2021). The growing decriminalization of marijuana has led to a burgeoning industry that is producing an expanding variety of marijuana products, making it accessible for use in numerous ways (NASEM, 2017; Peters and Chien, 2018; Cohn et al., 2017; Peters and Chien, 2018). For example, joints (rolling it into a cigarette), blunts (rolled into a cigar wrap), spliffs (marijuana mixed with tobacco), and vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are different routes of consuming marijuana (Peters and Chien, 2018; Ben Taleb et al., 2020; Loflin and Earleywine, 2014). The relaxed regulatory environment in the US, coupled with the industry’s enormous investments in marketing (Hollenbeck and Uetake, 2021), may entice users to experiment with new routes of consuming marijuana. One of the ways that is not fully captured in the literature is using hookah to smoke marijuana. Hookah is a waterpipe device typically used to smoke sweetened and flavored tobacco (Ben Taleb et al., 2019; Maziak et al., 2015). Over the past few decades, hookah smoking gained popularity among youth and adults in the US despite its well-established harmful effects on human health (Qasim et al., 2019; El-Zaatari et al., 2015; Ali and Jawad, 2017). According to the Monitoring the Future survey, in 2018, nearly 1 in every 13 (7.8%) high school students (Johnston et al., 2019) and about 1 in every 8 (12.3%) young adults aged 19-30 in the US had used a hookah to smoke tobacco during the previous year (Schulenberg et al., 2019).

Many hookah users misperceive hookah as a less harmful product compared to cigarette smoking, which may pave the way to use this device to inhale other substances, including marijuana (Sutfin et al., 2014). Smoking marijuana from a hookah device with a group of friends with long smoking sessions - typical for traditional hookah tobacco use (Maziak et al., 2015)- can likely increase the risk of addiction to marijuana and higher exposure to both toxicants emitted from hookah smoking by other users in the social gathering and marijuana smoke itself. Evidence shows that some hookah users smoke marijuana out of the same device they use for tobacco (Sutfin et al., 2014; Smith-Simone et al., 2008). Additionally, anecdotal reports show that smoking hookah loaded with marijuana is growing in popularity (EMJAY, 2022) and has been widely circulated on social media platforms like Reddit (Reddit, 2022). Therefore, smoking marijuana from a hookah device has the potential to grow in popularity, especially in countries with legalized marijuana–such as the US and Canada–which may pose a threat to public health. Most importantly, the combined toxicant exposure of smoking marijuana and tobacco using a hookah device poses an increased risk of developing diseases. Evidence regarding the co-use of marijuana and other tobacco products reveals a higher concentration of combustion-related toxicants among co-users compared with exclusive tobacco users (Smith et al., 2020). Specifically, the use of charcoal as a source of combustion in hookah has been associated with an elevated concentration of heavy metals and carbon monoxide that are detrimental to health and linked with developing chronic diseases and malignancies (Qasim et al., 2019; Lopez et al., 2017; Rostami et al., 2021; Schubert et al., 2015; Ali and Jawad, 2017). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, the rates of smoking marijuana from a hookah and the factors associated with this route of consumption have never been investigated. This study examines the prevalence of smoking marijuana from a hookah and its correlates using a nationally representative sample of US adults. We also examined the temporal trend in using a hookah device to smoke marijuana.

METHODS

Design and sample

Using the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) cohort study, cross-sectional analyses (Wave 5, December 2018-November 2019; with a response rate of 69.4% at Wave 5, N=34,309) and longitudinal analyses (Waves 3-5, from October 2015 to November 2019) were conducted. PATH survey collected data on using marijuana through hookah starting wave 2. The response rate for associated questions (Have you ever smoked marijuana from a hookah?) in Wave 2 was 11.7% (N= 3,325). However, the response rate for the same question was 99.9% for Wave 3 (N=28,111), 97.2% for wave 4 (N= 32,869), and 99.9% (N= 34,279) for Wave 5. The PATH Study is an ongoing large-scale and nationally representative cohort study in the US. It uses a four-stage stratified area probability sample design, varying sampling rates for adults by age, race, and tobacco use status. Adults (≥18 years of age) were screened in person, and African Americans, 18–24 year olds, and tobacco users were oversampled (Hyland et al., 2017). Details about the study design and methodology can be found elsewhere (Hyland et al., 2017; USDHHS, 2021). The Westat research firm collected PATH study data and obtained written informed consent from all adult participants. The PATH study was approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. We used publicly available deidentified data; hence, this study was deemed exempt from institutional review board oversight. The current study followed the reporting guideline of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) (Von Elm et al., 2007).

Measures

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was ever smoking marijuana from a hookah. All respondents were asked “Have you ever smoked marijuana from a hookah?” with response options “yes” (coded as 1) or “no” (coded as 0). The information for the past 30 days use of marijuana from a hookah was not collected in the PATH study.

Independent variables

Demographic variables included sex (male and female), age (18-24, 25-44, 45-64, and ≥65 years), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic/Latinx White [herein: White], non-Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American [herein: Black], Hispanic/Latino/a/x [herein: Hispanic], and other race/multiracial non-Hispanic/Latinx [herein: other/multiracial], or not reported, level of education [high school or less vs. more than high school], and annual household income [less than $50,000 vs. $50,000+]). Sexual orientation was assessed by the question “Do you consider yourself to be…,” with response options of “straight,” “lesbian or gay,” “bisexual,” and “something else.” Respondents who identified as lesbian or gay, bisexual, or something else were coded as LGBs vs. straight (Wheldon et al., 2018). We also included the pregnancy status in the past 12 months. Female participants aged 18-50 were asked “In the past 12 months, have you been pregnant? Please include a current pregnancy, live births, miscarriages, abortions, ectopic or tubal pregnancies, and stillbirths” with response items as “yes” or “no.”

Self-perception of mental health was measured by asking how participants would rate their mental health, including stress, depression, and emotional problems. The response options were excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. We dichotomized response options as good (excellent, very good, or good) vs. poor (fair or poor).

Tobacco use measures are defined in Supplementary e-Table 1. We measured the use of cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), hookah (smoked tobacco in a hookah), cigars (including traditional cigars, filtered cigars, and cigarillos), pipe filled with tobacco, snus pouches, and smokeless tobacco. Three categories were defined to measure product use status (never, former, or current use). Those who never used [product], even once, were defined as “never users.” Those who were defined in PATH Study as former established or experimental users were categorized as “former users.”Those who were defined as current established, experimental, or past 30-day users were categorized as “current users.” Never use was coded as 0, former use as 1, and current use as 2, with 0 as the reference group (see definitions of tobacco use status in Supplementary e-Table 1). We measured current blunt use (yes vs. no) in the past 30 days preceding the survey.

Hookah tobacco use-specific characteristics were measured using several items collected from adult respondents (n=1,920) who were current established, current experimental, or past 30-day hookah (tobacco) smokers. Participants were asked, “Where [do/did] you usually smoke hookah?” and responded to “your home,” “someone else's home,” “a hookah bar or café,” “a dance club or lounge,” and “in somewhere else.” Each response option was categorized as “yes” vs “no”. Participants also provided information about sharing their hookah, whether it contained tobacco, and whether they ever used liquid besides water in the hookah bowl. Lastly, we included an item to explore which hookah tobacco flavors were usually/last smoked (e.g., menthol, or fruit).

Data analysis

Using survey procedures in SAS/STATv15.2, all reported percentages were weighted employing wave 5 single-wave sampling weights to account for the complex survey design and generate nationally representative and unbiased estimates. Unweighted and weighted frequencies with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were reported. As suggested by PATH study guideline (McCarthy, 1969; USDHHS, 2021), variances were estimated using a balanced repeated replication method with Fay adjustment (e.g., Fay = 0.3). Bivariate associations between outcome and each independent variable were estimated, and Rao-Scott p-values were reported. Weighted multivariable logistic regression models were applied to examine associations between outcome and independent variables (i.e., demographics, mental health, tobacco product use, and blunt use). Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and corresponding 95% CI were reported. Only a few variables had missing values for more than 1%of the cases (i.e., sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and annual income) due to participants not knowing the answer or refusing to respond; we considered these values as “Not reported” for each variable in our regression model to account for any unknown association (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population, Wave 5 PATH Study (n = 34,279)

| Variables | Unweighted n | Weighted % (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 11,919 | 11.74 (11.38-12.12) |

| 25–44 | 11,732 | 33.05 (32.43-33.67) |

| 45+ | 7,407 | 33.30 (32.48-34.13) |

| 65+ | 3,221 | 21.91 (21.35-22.48) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 17,491 | 51.91 (51.33-52.49) |

| Male | 16,744 | 48.09 (47.51-48.67) |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Straight | 30,337 | 91.96 (91.49-92.40) |

| LGB | 3,572 | 6.58 (6.18-7.00) |

| Not reported a | 370 | 1.46 (1.24-1.71) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 5,080 | 11.19 (10.83-11.56) |

| White | 18,692 | 63.85 (63.29-64.40) |

| Hispanic | 6,172 | 13.54 (13.15-13.94) |

| other/multiracial | 2,691 | 7.52 (7.22-7.83) |

| Not reported b | 1,644 | 3.88 (7.22-4.28) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 14,645 | 37.91 (37.35-38.47) |

| More than high school | 19,491 | 62.09 (61.52-62.64) |

| Income | ||

| Less than $50,000 | 18,926 | 46.68 (45.70-47.68) |

| $50,000 or more | 13,214 | 46.76 (45.81-47.72) |

| Not reportedc | 2,139 | 6.55 (6.07-7.05) |

| Self-reported mental health | ||

| Good | 27,133 | 84.75 (84.07-85.40) |

| Poor | 7,036 | 15.25 (14.60-15.93) |

| Pregnancy in the past 12 months d | ||

| No | 9706 | 90.5 (89.58-91.32) |

| Yes | 1214 | 9.5 (8.68-10.41) |

| ENDS use | ||

| Never | 16,713 | 70.05 (69.30-70.78) |

| Former | 14,299 | 25.17 (24.50-25.85) |

| Current | 3,172 | 4.79 (4.53-5.06) |

| Cigarettes use | ||

| Never | 10,987 | 33.15 (32.03-34.29) |

| Former | 14,664 | 50.44 (49.41-51.46) |

| Current | 8,579 | 16.42 (15.85-17.00) |

| Used tobacco in hookah | ||

| Never | 22556 | 79.54 (78.77-80.30) |

| Former | 11226 | 19.79 (19.06-20.54) |

| Current | 412 | 0.65 (0.57-0.76) |

| Cigars use | ||

| Never | 16,069 | 56.16 (55.03-56.15) |

| Former | 15,942 | 41.97 (42.35-44.60) |

| Current | 1,627 | 0.36 (0.29-0.45) |

| Pipe use (filled with tobacco) | ||

| Never | 27,581 | 81.15 (80.40-81.89) |

| Former | 6,401 | 18.48 (17.75-19.23) |

| Current | 196 | 0.37 (0.30-0.45) |

| Snus pouch use | ||

| Never | 30,212 | 92.55 (92.17-92.92) |

| Former | 3,511 | 7.01 (6.65-7.39) |

| Current | 240 | 0.44 (0.37-0.53) |

| Smokeless tobacco use | ||

| Never | 27,400 | 83.30 (82.49-84.08) |

| Former | 5,546 | 14.52 (13.78-15.29) |

| Current | 1,053 | 2.18 (1.98-2.39) |

| Blunt use (past 30 days) | ||

| No | 2,817 | 97.05 (96.82-97.27) |

| Yes | 7,325 | 2.95 (2.73-3.18) |

| Ever used marijuana from a hookah | ||

| No | 29758 | 90.3 (89.77-90.85) |

| Yes | 4521 | 9.67 (9.14-10.23) |

LGB, Lesbian, gay or bisexual, or something else. ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems.

Note. Some variables may not add up to the total number because there were <1% missing in variables gender, education, mental health, tobacco products, and blunt use.

In wave 5 PATH study codebook, n= 371 participants either answered “Don’t know” (n= 61) or “refused” to respond (n= 310) to the sexual orientation question. We included information from n=370 participants in our analysis to account for these responses instead of excluding or imputing them since they were not missing at random.

n= 1,670 participants either answered “Don’t know” (n= 1,022) or “refused” to respond (n= 648) to race and ethnicity questions. We included information from n=1,644 participants in our analysis.

n= 2,147 participants either answered “Don’t know” (n= 1087) or “refused” to respond (n= 1059) for the income question. We included information from n=2,139 participants in our analysis.

Female participants aged 18-50 responded to the pregnancy status item.

We examined the regression models for any potential multicollinearity by tolerance <0.1, VIF >10, and eigenvalues close to zero (Kim, 2019; Vatcheva et al., 2016) and found no evidence of multicollinearity among the covariates except for variable “Used tobacco in hookah.” Hence, this variable was removed from the multivariable regression model. Further, we performed several multivariable regression models to explore the association between hookah tobacco use-specific characteristics and smoking marijuana from a hookah accounting for age, gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, education, annual income, and mental health. There was no evidence of multicollinearity in these models. To explore the association between a pregnancy in the past 12 months and smoking marijuana from a hookah device, an additional multivariable regression model (accounting for all other variables) was performed restricting the sample to only female participants (N=10,920). The statistical significance level was set at α=0.05, along with consideration of other evidence, such as the magnitude of association and variability.

Trend analysis

Based on the reviewer’s suggestion, we conducted a time series trend analysis using National Institue of Health JoinPoint software Version 4.9.1.0 (https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/) to explore temporal change in the prevalence of using marijuana from a hookah between Waves 3 and 5. Each wave’s single-wave sampling weights were used to account for the complex survey design and generate nationally representative and unbiased estimates.

RESULTS

The main characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1. In 2018-2019, 23.6 million (9.7%) US adults reported ever smoking marijuana from a hookah. Of these 23.6 million, about 11 million (5.7%) never smoked tobacco in a hookah, 12 million (24.8%) were former smokers, and about half a million (34.5%) were current smokers (Supplementary e-Table 2). The trend analysis of PATH data showed that the prevalence of using marijuana from a hookah increased significantly from 2015-16/wave 3 (8.9%,) to 2018-19/wave 5 (9.7%; time trend p=.007) (Figure 1).

Figure1.

Temporal trend in smoking marijuana from a hookah device (2015-2019), United States Adults.

Adults who were 25-44 years old (vs. 18-24; AOR=1.4: 95%CI=1.2-1.6) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah device (Table 2). Also, smoking marijuana from hookah was more likely to occur among people who were white (vs. Black; AOR=1.2: 1.1-1.5), LGBs (vs. straight; AOR=1.5: 1.3-1.8), had more than a high school education (vs. less than high school; AOR=1.3:1.2-1.5) or reported poor mental health (vs. good; AOR=1.2: 1.0-1.3). Adults with an annual income of $50,000 or more (vs. <$50,000; AOR= 0.9: 0.8-1.0) were less likely to report ever smoking marijuana from a hookah (all ps<0.05). Our additional multivariable regression model among female participants (data not shown) revealed that women who were pregnant in the past 12 months were more likely to ever smoke cannabis from a hookah device (AOR=1.3: 1.1-1.8, p=0.03).

Table 2.

Multivariable regression model of ever using a hookah to smoke marijuana (n=4521) compared to never users (n= 29,758), PATH Wave 5

| Variables | No. who used hookah to smoke marijuana/No. in category | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted n | Weighted % (95 % CI) |

Estimated Population |

Rao-Scott p-value |

aOR (95 %CI), p-value | |

| Overall | 4521 | 9.7 (9.1-10.2) | 23,559,415 | ||

| Age group (years) | <.0001 | ||||

| 18–24 | 1066 | 9.4 (8.7-10.2) | 2,685,834 | Ref | |

| 25–44 | 2235 | 13.2 (12.5-14.0) | 10,661,599 | 1.4 (1.2-1.6), <.0001 | |

| 45–64 | 911 | 8.6 (7.7- 9.6) | 6,974,416 | 1.1 (1.0-1.4), 0.1308 | |

| 65+ | 309 | 6.1 (5.1- 7.2) | 3,237,566 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2), 0.9263 | |

| Sex | <.0001 | ||||

| Female | 1964 | 7.2 (6.7-7.8) | 9,092,337 | Ref | |

| Male | 2552 | 12.3 (11.5-13.3) | 14,441,949 | 1.1 (0.9-1.2), 0.2543 | |

| Sexual Orientation | <.0001 | ||||

| Straight | 3768 | 9.2 (8.7- 9.8) | 20,637,285 | Ref | |

| LGB | 720 | 17.2 (15.3- 19.2) | 2,748,685 | 1.5 (1.3-1.8), <.0001 | |

| Not reported | 33 | 4.9 (2.8- 8.2) | 173,445 | 0.7 (0.3-1.4), 0.2641 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | ||||

| Black | 611 | 8.5 (7.7- 9.4) | 2,317,272 | Ref | |

| White | 2740 | 10.6 (9.9- 11.4) | 16,537,112 | 1.2 (1.1-1.5), 0.004 | |

| Hispanic | 664 | 7.7 (6.9- 8.6) | 2,937,279 | 1.1 (0.9-1.3), 0.4969 | |

| other/multiracial | 363 | 7.9 (6.6- 9.5) | 1,451,405 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4), 0.6707 | |

| Not reported | 143 | 6.6 (5.1-8.4) | 621,783 | 1.0 (0.7-1.3), 0.8066 | |

| Education | <.0001 | ||||

| High school or less | 1854 | 8.9 (8.4- 9.6) | 8,264,183 | Ref | |

| More than high school | 2656 | 10.1 (9.5- 10.8) | 15,240,397 | 1.3 (1.2-1.5), <.0001 | |

| Income | <.0001 | ||||

| Less than $50,000 | 1763 | 10.7 (10.2- 11.3) | 12,224,022 | Ref | |

| $50,000 or more | 984 | 9.1 (8.3- 10.0) | 10,396,613 | 0.9 (0.8-1.0), 0.0167 | |

| Not reported | 183 | 5.9 (4.7-7.3) | 938,780 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1), 0.2293 | |

| Self-reported mental health | <.0001 | ||||

| Good | 3318 | 9.0 (8.4- 9.5) | 18,426,418 | Ref | |

| Poor | 1191 | 13.7 (12.6- 15.0) | 5,085,392 | 1.2 (1.0-1.3), 0.0127 | |

| ENDS use | <.0001 | ||||

| Never | 1066 | 5.2 (4.7- 5.8) | 8,809,280 | Ref | |

| Former | 2706 | 19.3 (18.3- 20.4) | 11,816,758 | 1.9 (1.7-2.2), <.0001 | |

| Current | 744 | 25.0 (23.0- 27.1) | 2,907,528 | 2.1 (1.8-2.5), <.0001 | |

| Cigarettes use | <.0001 | ||||

| Never | 388 | 1.8 (1.6- 2.2) | 1,480,984 | Ref | |

| Former | 2246 | 11.2 (10.4- 12.1) | 13,785,155 | 3.3 (1.6-4.1), <.0001 | |

| Current | 1883 | 20.7 (19.5-22.0) | 8,277,462 | 3.8 (1.0-4.7), <.0001 | |

| Cigars use | <.0001 | ||||

| Never | 804 | 3.3 (2.9-3.7) | 4,526,055 | Ref | |

| Former | 3673 | 17.2 (16.2-18.3) | 17,095,052 | 2.2 (1.9-2.6), <.0001 | |

| Current | 34 | 26.9 (24.2- 29.8) | 1,900,900 | 1.1 (1.5-4.6), 0.0008 | |

| Pipe use (filled with tobacco) | <.0001 | ||||

| Never | 2705 | 6.9 (6.5- 7.4) | 13,658,283 | Ref | |

| Former | 1743 | 21.4 (19.8- 23.0) | 18,786,462 | 1.7 (1.5-2.0), <.0001 | |

| Current | 69 | 33.0 (24.9-42.2) | 294,210 | 2.0 (1.3-3.0), 0.0017 | |

| Snus pouch use | <.0001 | ||||

| Never | 3468 | 8.4 (7.9- 8.9) | 18,789,340 | Ref | |

| Former | 930 | 25.0 (23.0- 27.2) | 4,244,787 | 1.1 (1.0-1.3), 0.0932 | |

| Current | 81 | 30.8 (23.9-38.6) | 327,738 | 1.8 (1.2-2.6), 0.0021 | |

| Smokeless tobacco use | <.0001 | ||||

| Never | 2962 | 7.6 (7.1- 8.1) | 15,336,780 | Ref | |

| Former | 1317 | 20.5 (18.7- 22.3) | 7,202,489 | 1.2 (1.0-1.3), 0.0648 | |

| Current | 209 | 17.1 (14.2-20.5) | 905,293 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1), 0.3173 | |

| Blunt use (past 30 days) | <.0001 | ||||

| No | 3704 | 8.7 (8.2- 9.3) | 20,613,270 | Ref | |

| Yes | 786 | 39.3 (36.5- 42.1) | 2,810,811 | 3.4 (1.8-4.0), <.0001 | |

LGB, Lesbian, gay or bisexual, or something else. ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems. Some variables may not add up to the total number because there were <1% missing in variables gender, education, mental health, all tobacco products, and blunt use. The reference group for the multivariable model was “never users” of marijuana from a hookah device.

Compared to never ENDS users, former (AOR=1.9: 1.7-2.2) and current users (AOR= 2.1: 1.8-2.5) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah. Similarly, compared to never cigarette smokers, former (AOR=3.3: 1.6-4.1) and current users (AOR=3.8: 1.0-4.7) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah. Compared to never cigar smokers, former (AOR= 2.2: 1.9-2.6) and current users (AOR=1.1: 1.5-4.6) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah (all ps<0.05). Former pipe users (vs. never users; AOR=1.7: 1.5-2.0) and current pipe users (vs. never users; AOR=2.0: 1.3-3.0) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah. Only current (vs. never; AOR=1.8: 1.2-2.6) snus pouches users were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah (all ps<0.05). Finally, past 30-day blunt users were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah (AOR=3.4: 1.8-4.0; p<0.0001) compared to non-users.

Table 3 illustrates the association between hookah tobacco use-specific characteristics and ever smoking marijuana from a hookah. Adult hookah tobacco users who smoked hookah in someone else home (AOR=1.6: 1.2-2.1), ever used another liquid besides water in the bowl of the hookah (AOR=3.2: 2.3-4.7), and used an alcoholic drink flavor in their hookah (AOR=2.6: 1.6-4.3) were more likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah compared to those who did not smoke marijuana from a hookah. On the other hand, adults who usually smoked hookah tobacco at bars or cafés (AOR=0.6: 0.4-0.9), usually used hookah that contained tobacco (AOR=0.6: 0.4-0.9) or reported menthol or mint as their favorite flavor (AOR=0.6: 0.4-0.9) were less likely to smoke marijuana from a hookah.

Table 3.

Hookah tobacco use-specific characteristics and ever smoked marijuana from a hookah, wave 5 PATH Study (n= 1,920) *

| Characteristics | Ever smoked marijuana; yes vs no | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Where [do/did] you usually smoke hookah tobacco? yes vs no | ||

| In your home | 1.3 (0.96-1.7) | 0.0968 |

| In someone else's home | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 0.0007 |

| In a hookah bar or café? | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 0.0039 |

| In a dance club or lounge | 0.8 (0.6-1.2) | 0.3327 |

| In somewhere else | 0.9 (0.3-2.8) | 0.7896 |

| Usually share hookah with others, yes vs no | 1.5 (0.9-2.3) | 0.0517 |

| When smoked hookah whether shisha usually contain tobacco, yes vs no | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 0.0394 |

| Ever used another liquid besides water in the bowl of the hookah, yes vs no | 3.2 (2.3-4.7) | <.0001 |

| Hookah tobacco flavor usually/last smoked,, yes vs no | ||

| Menthol or min | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 0.0263 |

| Clove or spice | 0.8 (0.4-1.8) | 0.7164 |

| Fruit | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 0.7192 |

| Chocolate | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 0.7238 |

| An alcoholic drink | 2.6 (1.6-4.3) | 0.0002 |

| Candy or other sweets | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.9583 |

| Some other flavor | 1.8 (0.3-10.0) | 0.4757 |

Note. Each multivariable model was adjusted for age, gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, education, annual income, and mental health.

The sample for this analysis was adult respondents who were current established, current experimental, recent former established, or past 30-day hookah (tobacco) smokers who provided information about using tobacco in hookah.

DISCUSSION

While hookah is traditionally used to smoke shisha tobacco—tobacco leaves that are treated with a combination of molasses, glycerin, and honey—it can be adapted for other substances such as marijuana (High desert, 2022; Sutfin et al., 2014). This nationally representative study among a sample of US adults is the first to document that nearly 24 million US adults are estimated to have ever smoked marijuana from a hookah device, with a worrisome increasing trend. This is a novel finding that has not been reported in previous nationwide studies, which mainly focused on other routes of consuming marijuana, such as cigars (blunt) or ENDS (Ebrahimi Kalan et al., 2021; Knopf and Letter, 2020; Morean et al., 2015; Peters and Chien, 2018; Ben Taleb et al., 2020). In our study, smoking marijuana from a hookah device was more prevalent among middle-aged adults, whites, LGBs individuals, more educated but lower-income, and those with self-reported poor mental health. In addition, former and current users of different tobacco products had greater odds of smoking marijuana from hookah than never users.

Based on our results, the popularity of smoking marijuana from a hookah among former and current hookah tobacco users raises an important public health concern. Since marijuana is typically mixed with shisha tobacco when smoked through hookah (High desert, 2022; Hookah Forum, 2004), the combined toxicant exposure of marijuana and tobacco may represent an increased health burden and an additional risk for developing diseases. Combustion-related toxicants such as acrylonitrile and acrylamide metabolites have been detected among marijuana smokers (Lorenz et al., 2021). In fact, evidence regarding the co-use of marijuana and various tobacco products indicates a higher concentration of toxicants among co-users compared with exclusive tobacco users (Smith et al., 2020). Moreover, analyses of hookah tobacco–the tobacco used in hookah—and charcoal revealed substantial amounts of heavy metals, including nickel, cadmium, lead and chromium (Rostami et al., 2021; Schubert et al., 2015). This is in addition to the elevated concentration of carbon monoxide that is inhaled during hookah smoking (Lopez et al., 2017). Therefore, there is an urgent need to accurately characterize the combined toxicant exposure profile of smoking marijuana from hookah to better understand the collective health risks associated with this method of marijuana smoking and to protect public health, especially among vulnerable populations, including LGBs individuals, lower-income, and those with poor mental health.

Our finding that smoking marijuana from a hookah is associated with use of several tobacco products (cigarette, ENDS, hookah tobacco, cigar, pipe, and snus) has important implications for tobacco control. implications were the characterizing of the relationship between the use of tobacco products among US adults and smoking marijuana from a hookah. Specifically, our data revealed a significant association between ever and current use of tobacco products and smoking marijuana from a hookah. Our results suggest that adults with prior or existing experience using tobacco products are more likely to utilize hookah to consume marijuana. A previous study (Sutfin et al., 2014) of students from 8 colleges in North Carolina reported a high prevalence of smoking marijuana from a hookah among current cigarette smokers. This pattern was also identified in previous studies among youth who vape marijuana using ENDS and found a positive correlation with ever and current use of tobacco products (Ben Taleb et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2018). Emerging evidence also shows that marijuana use appears to be associated with poorer smoking cessation (Goodwin et al., 2022). Taken together, these findings call for the need to integrate educational elements into preventive interventions and tobacco control campaigns regarding the use of tobacco products such as hookah to consume marijuana and the potential impact on health and advancing cessation of tobacco products.

In our study, adults who usually smoked hookah tobacco in someone else’s home (apparently a friend’s place) were more likely to smoke marijuana through hookah, while those who smoked hookah tobacco in a bar or café were less likely to try marijuana from a hookah. In addition, two potentially risky characteristics of regular hookah tobacco smokers (who smoked marijuana from the device) were using another liquid besides water in the bowl of the hookah and using an alcoholic drink flavor (but not menthol) in a hookah. These findings signal the importance of further investigations among this unique population of marijuana smokers through hookah at the national level, which could have both regulatory and clinical implications.

Our previous report (Kondracki et al., 2021) from the PATH survey showed an increasing trend in using marijuana among reproductive-age women in the US. This study adds to the literature a new mode of marijuana consumption-hookah device-that is popular among this vulnerable age group of women compared to their counterparts. Although potential dire health consequences of using marijuana during pregnancy (e.g., lower birth weight) have been documented (NASEM, 2017), it is crucial to continuously monitor the current use of marijuana among this population, along with collecting data on the mode of consumption (e.g., hookah, ENDS, and cigars).

This study has some limitations. First, we only measured ever use of marijuana through a hookah. The PATH Study is the only nationally representative study (to our knowledge) providing this question; future national surveys, especially among youth, should explore current use (past 30 days) of marijuana from a hookah. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the multivariable analyses in our study precludes any causal relationship between the outcome and independent variables. Since our longitudinal trend analysis showed an increasing trend in smoking marijuana through hookah, future longitudinal studies are needed to assess the bidirectional causal association between regular smoking marijuana in hookah and the use of other tobacco products. Furthermore, this study used self-reported data, which may introduce recall bias and social desirability bias. Nonetheless, self-reporting of smoking habits is generally reliable and has been consistently used in previous studies assessing smoking behaviors (Patrick et al., 1994).

CONCLUSIONS

This nationally representative study showed that many adults in the US have smoked marijuana from a hookah, and the trends of using this mode of consumption are rising. Additionally, the concurrent use of marijuana and tobacco products, especially from a hookah, is an emerging public health challenge requiring educational and regulatory actions to prevent cumulative dire health consequences (e.g., lung damage) instigated by smoking these substances. Although we reported ever use of marijuana in hookah among US adults and explored some important risk factors, additional research lies ahead to better understand this contemporary route of consuming marijuana. In the era of the legalization of marijuana in the US and the growing concurrent use of tobacco products and marijuana (Smith et al., 2021), consistent monitoring of use—including routes to consume this drug—is crucial to inform tailored preventive intervention programs (e.g., integrating educational elements and tobacco control campaigns regarding hookah use to consume marijuana) and related regulatory actions. Such actions are crucial to curb the exclusive and co-use of marijuana and tobacco products, especially among vulnerable populations including pregnant women, LGBTs, and people with poor mental health conditions.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Dr.Ben Taleb is supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institute of Health (1R03DA054417)

Footnotes

Declarations of competing interest: None

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. REFERENCES

- Ali M, & Jawad M (2017). Health effects of waterpipe tobacco use: getting the public health message just right. Tobacco use insights, 10, 1179173X17696055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Taleb Z, Ebrahimi Kalan M, Bahelah R, Boateng GO, Rahman M, Alshbool FZ, 2020. Vaping while high: Factors associated with vaping marijuana among youth in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 217, 108290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Taleb Z, Breland A, Bahelah R, Kalan ME, Vargas-Rivera M, Jaber R, … & Maziak W (2019). Flavored versus nonflavored waterpipe tobacco: a comparison of toxicant exposure, puff topography, subjective experiences, and harm perceptions. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 21(9), 1213–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitendag E, 2017. The big bong theory. New Media Publishing. 17(7), 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, Johnson AL, Rose SW, Rath JM, & Villanti AC (2017). Support for Marijuana Legalization and Predictors of Intentions to Use Marijuana More Often in Response to Legalization Among U.S. Young Adults. Subst Use Misuse, 52(2), 203–213. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1223688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crume TL, Juhl AL, Brooks-Russell A, Hall KE, Wymore E, Borgelt LM, 2018. Cannabis Use During the Perinatal Period in a State With Legalized Recreational and Medical Marijuana: The Association Between Maternal Characteristics, Breastfeeding Patterns, and Neonatal Outcomes. J Pediatr. 197, 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Catley D, Richter KP, Goggin K, Ellerbeck EF, 2018. Electronic Cigarettes and Future Marijuana Use: A Longitudinal Study. Pediatrics. 141(5), e20173787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellazizzo L, Potvin S, Giguère S, Dumais A, 2022. Evidence on the acute and residual neurocognitive effects of cannabis use in adolescents and adults: a systematic meta-review of meta-analyses. Addiction. 117(7), 1857–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi Kalan M, Jebai R, Bursac Z, Popova L, Gautam P, Li W, Alqahtani MM, Taskin T, Atwell LL, Richards J, Ward KD, Behaleh R, Ben Taleb Z, 2021. Trends and Factors Related to Blunt Use in Middle and High School Students, 2010–2020. Pediatrics. 148(1), e2020028159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Zaatari ZM, Chami HA, & Zaatari GS (2015). Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking. Tobacco control, 24(Suppl 1), i31–i43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMJAY, 2020. Can You Smoke Weed From A Hookah? https://blog.heyemjay.com/can-you-smoke-weed-from-a-hookah/#:~:text=Absolutely!,%2C%20or%20e%2Dcigarette%20vaporizer . (Accessed July 7 2022).

- Goodwin RD, Shevorykin A, Carl E, Budney AJ, Rivard C, Wu M, McClure EA, Hyland A, Sheffer CE, 2022. Daily Cannabis Use Is a Barrier to Tobacco Cessation Among Tobacco Quitline Callers at 7-Month Follow-up. Nicotine Tob Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High desert, 2022. Cannabis hookah mixture. https://high-desert.com/. (Accessed July 7 2022).

- Hollenbeck B, Uetake K, 2021. Taxation and market power in the legal marijuana industry. RAND J Econ. 52(3), 559–595. [Google Scholar]

- Hookah Forum, 2004. Weed in hookah. https://www.hookahforum.com/topic/596-weed-in-hookah/. (Accessed July 7 2022).

- Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Lambert E, Carusi C, Taylor K, Crosse S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, Abrams D, Pierce JP, Sargent J, Messer K, Bansal-Travers M, Niaura R, Vallone D, Hammond D, Hilmi N, Kwan J, Piesse A, Kalton G, Lohr S, Pharris-Ciurej N, Castleman V, Green VR, Tessman G, Kaufman A, Lawrence C, van Bemmel DM, Kimmel HL, Blount B, Yang L, O'Brien B, Tworek C, Alberding D, Hull LC, Cheng YC, Maklan D, Backinger CL, Compton WM, 2017. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tob Control. 26(4), 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2019). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2018: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf A, 2020. Vaping nicotine and marijuana more than doubles among college-age students. CABL. 36(11), 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki AJ, Li W, Kalan ME, Ben Taleb Z, Ibrahimou B, & Bursac Z (2022). Changes in the National Prevalence of Current E-Cigarette, Cannabis, and Dual Use among Reproductive Age Women (18–44 Years Old) in the United States, 2013–2016. Substance Use & Misuse, 57(6), 833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CCW, Sun T, Leung J, Chung JYC, Gartner C, Connor J, Hall W, Chiu V, Stjepanović D, Chan GCK, 2022. Prevalence of Adolescent Cannabis Vaping: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of US and Canadian Studies. JAMA Pediatrics. 176(1), 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loflin M, Earleywine M, 2014. A new method of cannabis ingestion: The dangers of dabs? Addict Behav. 39(10), 1430–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AA, Eissenberg T, Jaafar M, Afifi R, 2017. Now is the time to advocate for interventions designed specifically to prevent and control waterpipe tobacco smoking. Addict Behav. 66, 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Pérez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, Okuda M, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C, 2011. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 115(1-2), 120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz DR, Misra V, Chettimada S, Uno H, Wang L, Blount BC, De Jesús VR, Gelman BB, Morgello S, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D, 2021. Acrolein and other toxicant exposures in relation to cardiovascular disease among marijuana and tobacco smokers in a longitudinal cohort of HIV-positive and negative adults. EClinicalMedicine. 31, 100697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggirwar SB, Khalsa JH, 2021. The Link between Cannabis Use, Immune System, and Viral Infections. Viruses. 13(6), 1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziak W, Taleb ZB, Bahelah R, Islam F, Jaber R, Auf R, & Salloum RG (2015). The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking. Tobacco control, 24(Suppl 1), i3–i12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy PJ, 1969. Pseudoreplication: further evaluation and applications of the balanced half-sample technique. Vital Health Stat 2. 31, 1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RSE, McDonald K, Ward A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE, 2012. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(40), E2657–E2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Kong G, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2015. High School Students' Use of Electronic Cigarettes to Vaporize Cannabis. Pediatrics. 136(4), 611–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASEM, 2017. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. National Academies Press (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCSL, 2021. National Conference of state legislatures. State Medical Cannabis Laws. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. (Accessed July 7 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S, 1994. The validity of self-reported smoking: A review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 84(7), 1086–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Chien J, 2018. Contemporary Routes of Cannabis Consumption: A Primer for Clinicians. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 118(2), 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ProCon.org, 2021. Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC as of Feburary 9 2021. https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/legal-medical-marijuana-states-and-dc/. (Accessed July 7 2022).

- Qasim H, Alarabi AB, Alzoubi KH, Karim ZA, Alshbool FZ, & Khasawneh FT (2019). The effects of hookah/waterpipe smoking on general health and the cardiovascular system. Environmental health and preventive medicine, 24(1), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddit, 2022. Hookah. https://www.reddit.com/r/hookah/comments/js3bx/i_dont_mean_disrespect_but_does_anyone_mix_weed/. (Accessed July 7 2022).

- Romm KF, West CD, Berg CJ, 2021. Mode of Marijuana Use among Young Adults: Perceptions, Use Profiles, and Future Use. Subst Use & Misuse. 56(12), 1765–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostami R, Ebrahimi Kalan M, Ghaffari HR, Saranjam B, Ward KD, Ghobadi H, Poureshgh Y, Fazlzadeh M, 2021. Characteristics and health risk assessment of heavy metals in indoor air of waterpipe cafés. Build Environ. 190, 107557. [Google Scholar]

- Rumalla K, Reddy AY, Mittal MK, 2016. Recreational marijuana use and acute ischemic stroke: A population-based analysis of hospitalized patients in the United States. J Neurol Sci. 364, 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, 2021. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. (Accessed July 7 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Schubert J, Müller FD, Schmidt R, Luch A, Schulz TG, 2015. Waterpipe smoke: source of toxic and carcinogenic VOCs, phenols and heavy metals? Arch Toxicol. 89(11), 2129–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Johnston L, O'Malley P, Bachman J, Miech R, & Patrick M (2019). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–60. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Kozlowski L, O’Connor RJ, Hyland A, Collins RL, 2021. Reasons for individual and concurrent use of vaped nicotine and cannabis: their similarities, differences, and association with product use. J Cannabis Res. 3(1), 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, O'Connor RJ, Wei B, Travers M, Hyland A, Goniewicz ML, 2020. Nicotine and Toxicant Exposure Among Concurrent Users (Co-Users) of Tobacco and Cannabis. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 22(8), 1354–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008. Feb;10(2):393–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, Song EY, Reboussin BA, Wolfson M, 2014. What are young adults smoking in their hookahs? A latent class analysis of substances smoked. Addict behav. 39(7), 1191–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan WC, Lo C, Jong A, Xing L, Fitzgerald MJ, Vollmer WM, Buist SA, Sin DD, & Vancouver Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) Research Group, 2009. Marijuana and chronic obstructive lung disease: a population-based study. CMAJ. 180(8), 814–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS, 2021. United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Drug Abuse, and United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Tobacco Products. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Public-Use Files (ICPSR 36498). https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/36498/datadocumentation#. (Accessed July 7 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH, 2016. Multicollinearity in Regression Analyses Conducted in Epidemiologic Studies. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale). 6(2), 227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Swanson JM, Evins AE, DeLisi LE, Meier MH, Gonzalez R, Bloomfield MA, Curran HV, Baler R, 2016. Effects of Cannabis Use on Human Behavior, Including Cognition, Motivation, and Psychosis: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry. 73(3), 292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, medicine, S.I.J.A.o.i., 2007. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 147(8), 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheldon CW, Kaufman AR, Kasza KA, Moser RP, 2018. Tobacco Use Among Adults by Sexual Orientation: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. LGBT Health. 5(1), 33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.