Abstract

Importance

Psychedelic drugs are becoming accessible to Americans through a patchwork of state legislative reforms. This shift necessitates consensus on treatment models, education and guidance for healthcare providers, and planning for implementation and regulation.

Objective

To assess trends in psychedelics legislative reform and legalization in the United States in order to provide guidance to healthcare professionals, policy makers, and the public.

Evidence

Analysis of data compiled from legislative databases (BillTrack50, LexisNexis, Ballotpedia). Legislation was identified by searching for terms related to psychedelics (e.g. psilocybin, MDMA, Peyote, Mescaline, Ibogaine, LSD, Ayahuasca, DMT). Bills were coded by an attorney along two axes: which psychedelic drugs would be affected and in what ways (i.e. the scope of the bill, including medical/legal oversight, when specified). To explore drivers and rate of legislative reform, data were compared to other state indices including 2020 presidential voting margins and marijuana legislative reform.

Findings

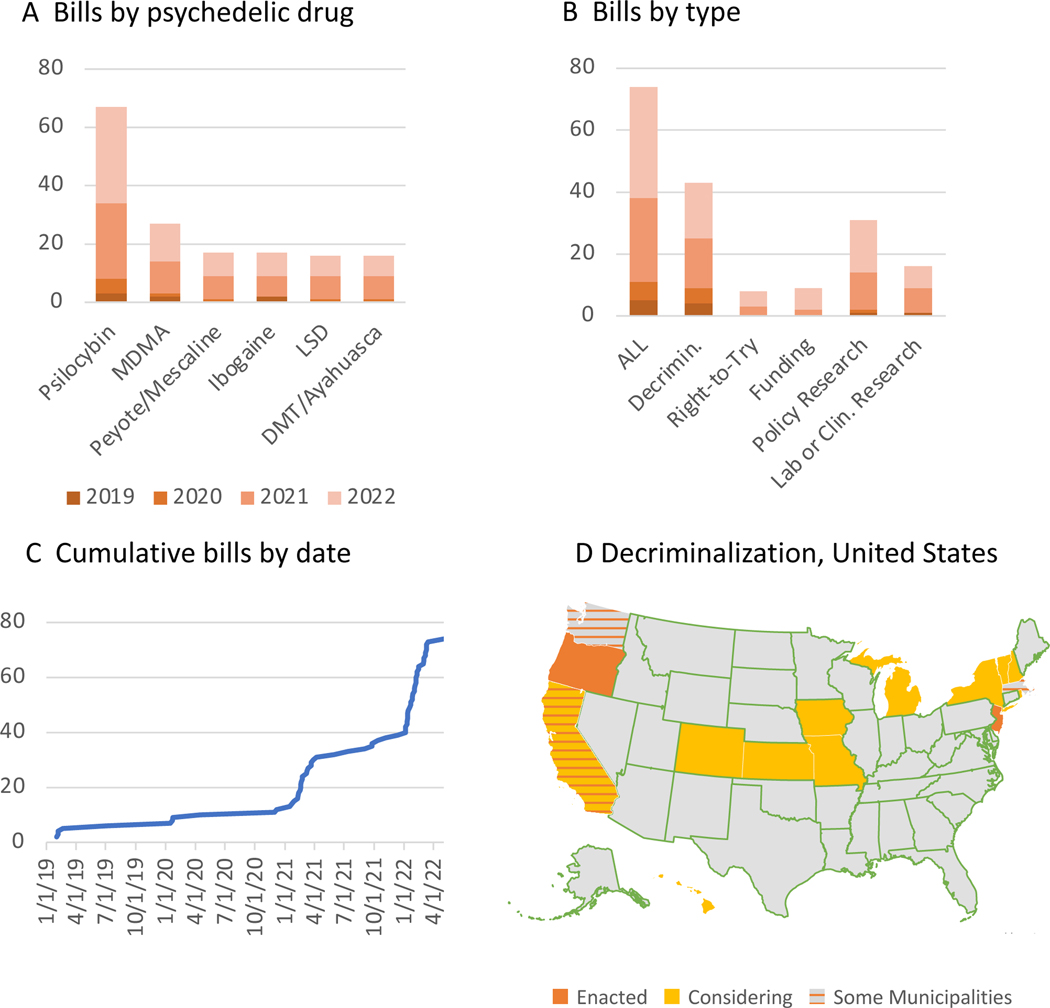

We find that 25 states have considered 74 bills (69 legislative initiatives, 5 ballot measures), with 10 bills were enacted, and 32 are still active. The number of psychedelic reform bills introduced during each calendar year has increased steadily from 5 (2019), 6 (2020), to 27 (2021), to 36 (2022). Nearly all specify psilocybin (67), and many also include MDMA (27). While bills varied in their framework, a majority (43) propose decriminalization, of which few delineate medical oversight (23%) or training/licensure requirements (35%). Generally, bills contained far less regulatory guidance than the enacted Oregon Measure 109. While early legislative efforts occurred in liberal states, this relationship may be shifting over time, indicating that psychedelic drug reform is becoming a bipartisan issue. Finally, an analytic model based on marijuana legalization projects that a majority of states will legalize psychedelics by 2033–2037.

Conclusions and Relevance

Psychedelic reform is proceeding in a rapid, patchwork fashion in the United States. Further consideration should be given to key healthcare issues such as 1) establishing standards for drugs procured outside the medical establishment, 2) licensure criteria for prescribers and therapists, 3) the clinical and billing infrastructure, 4) potential contraindications, and 5) use in special populations like minors, older adults, and pregnant women.

Introduction

The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (CSA), established federal control over possession, distribution, and production of drugs. Shortly thereafter, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) was established to enforce the CSA, which classified psychedelics, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), and cannabis as Schedule I substances with ‘no currently accepted medical use,’ a ‘lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision’, and ‘at least some potential for abuse sufficient to warrant control.’ In the intervening years, results from numerous studies in animals1 and humans,2 including a large multi-site clinical trials with psilocybin for treatment resistant depression,3 and MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder,4 have supported the safety and medical utility of psychedelics and brought about increasing acceptance and interest in the United States.

In May 2019, Denver, Colorado became the first city to decriminalize psilocybin.5 By the end of 2019, many cities were considering initiatives to decriminalize psychedelics (for a list of municipalities, see ref 5). A review panel appointed by the Denver City Council issued a report in Nov. 2021 finding no significant negative impact of decriminalization on public safety.6 They recommended training for first responders, public health education and messaging, data collection, and ongoing safety reporting.

In late 2020, Oregon became the first state to both decriminalize psilocybin and legalize it for therapeutic use. Oregon Ballot Measure 109 specified extensive guidelines (to be overseen by Oregon Health Authority) regarding psilocybin production, manufacturing requirements and licensure, psilocybin extraction, mandatory testing of purity and potency (testing laboratories themselves must be accredited by the Oregon Environmental Laboratory Accreditation Program), record keeping, and facilitator qualifications, training, and licensure.7–9 Between February and August 2021, Oregon law enforcement observed an 87% reduction in psilocybin-related arrests over previous years.10 As the first state to both decriminalize possession and provide clinical psilocybin services, the Oregon legislation created an advisory board that recently provided recommendations for training, administration, and communication of risks and benefits of psilocybin therapy to clients.11 Under the current laws, psilocybin use is restricted to licensed facilities with trained counselors; facilities will be able to apply for licenses beginning in 2023.12

Political efforts for psychedelics reform have percolated from cities and states to the federal level as Congress considers bipartisan legislation that would further limit DEA control of Schedule I drugs.13 In response, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has recently indicated that it may pursue a policy of “harm reduction, risk mitigation, and safety monitoring” regarding emerging substances such as psilocybin and MDMA rather than strict prohibition.14

These legislative initiatives are concurrent with rising scientific and business interests in psychedelics.15 In recent years, philanthropic funding of research has led to the creation of academic centers for psychedelic science across the country – including Johns Hopkins, University of California San Francisco, Massachusetts General Hospital, University of California Berkeley, Mount Sinai, University of Texas Austin, Washington University in St. Louis and others.16 In 2022, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and The National Institute of Drug and Alcohol Abuse (NIDAA) began offering educational programming to support investigators interested in working with psychedelic drugs.17 NIH support of this research brings greater funding and scientific rigor. However, investment in academic research is still an order of magnitude lower than the value of some of the publicly traded companies in the psychedelics space.

Private investment into psychedelic pharmaceutical R&D has surged since 2018,18 supported by an FDA breakthrough therapy designation for clinical trials of psilocybin for depression and MDMA for PTSD. In 2021, companies invested more than $730M in the development of psychedelic drugs and novel drug delivery systems;19 in contrast just $4M was invested by NIH in the same year. While early phase IIb/III results look promising,3,4 FDA approval remains just one step in a complex process to transform these compounds into therapies. It is not yet clear how to handle potential FDA approval of psychedelics in the context of ongoing DEA Schedule I classification.20 Moreover, it is unclear how the healthcare system would implement psychedelic treatment, which is a dramatic departure from currently available medical and behavioral therapies and raises unique challenges.21

The future of psychedelics in the United States hinges upon several factors: the outcome and FDA decision on ongoing clinical trials, the potential decisions by the DEA or governing bodies to change the classification of psychedelics, and legislative reform at the state level, which has been the primary driver of cannabis legalization.22 Cannabis achieved legalization through legislative reform in most states, despite continued DEA Schedule I status and the absence of FDA approval. Now, state legislative reforms are shifting the prospects of psychedelics treatment and illicit drug enforcement.

In the present study, we sought to characterize the current state of legislative reform around Schedule I psychedelic drugs. Archives such as BillTrack50 and Ballotpedia make legislature and ballot initiatives publicly available. We used data from these sources to assess trends in psychedelic decriminalization and legislative reform, with the overall aim of identifying whether key considerations for implementation of psychedelics as medical treatments are being addressed.

Methods

We compiled a database of state legislative and ballot initiatives related to psychedelic drug reform introduced in the United States beginning with the 2019 legislative session year. We 1) broadly characterized psychedelic legislative reform efforts occurring in the US, 2) compared decriminalization bills based on how psychedelic and psychedelic treatment will be implemented and regulated, 3) compared the 2020 presidential voting margins of states considering decriminalization to assess political drivers of legislation, and 4) developed an analytic model based on cannabis reforms to predict when psychedelic drugs will likely be legal across the US. We hypothesized that legislation proposed at the state level would vary widely with respect to legislative scope and that right-to-try legislation signed by a conservative president in 2018 would increase conservative state adoption of psychedelic drug reform.

Selection and coding of relevant legislation

Information was obtained from publicly available databases: BillTrack50,23 Ballotpedia,24 and LexisNexis,25 and included all bills and ballot initiatives relating to psychedelic drugs introduced into state legislatures in the 2019–2022 session years (final search was September 28, 2022). BillTrack50 and LexisNexis are commercial legislation databases that include free and paid services. Ballotpedia is a professionally-edited nonprofit free online encyclopedia that covers federal, state, and local politics, elections, and public policy in the United States. BillTrack50 was used for initial collection of relevant legislation. January 1, 2019 was chosen as the start date because signature gathering for the first enacted decriminalization bill (Oregon Measure 109) began in 2019.

BillTrack50 was searched for legislation mentioning the terms psilocybin, psilocyn, psilocin, MDMA, LSD, ibogaine, peyote, ayahuasca, or DMT. The LexisNexis state legislation database was searched for bills enacted since 2010 that mention any of those terms at least three times. This was done in order to eliminate irrelevant enacted bills that mention the search terms only incidentally, typically by repeating the entire schedule of controlled substances as part of the bill text (e.g. when the bill would add or remove an unrelated drug from the schedule). Ballotpedia, a professionally-edited online encyclopedia focused on United States politics and elections, was searched for ballot initiatives mentioning any of those terms.

Legislation and ballot initiatives were coded by an attorney (JD) to determine if the scope of each bill included decriminalization, right-to-try, funding, policy research, or laboratory or clinical research.

“Decriminalization” was defined as reduction or elimination of criminal penalties associated with possessing or distributing a psychedelic drug. “Right-to-try” was defined as legislation allowing access to psychedelics for a particular patient population, such as patients with terminal illnesses for whom other therapies have not been effective. “Funding” was defined as any explicit appropriation of funds or budgeted amounts for psychedelic research, treatments, or regulation. “Policy research” was defined as the establishment of psychedelic therapy advisory boards or the preparation of reports for the legislature, state health department, or similar policy body. “Laboratory or clinical research” was defined as permitting, funding, or requiring the performance of laboratory or clinical research regarding psychedelic therapies

Irrelevant bills that did not include at least one of those policies were excluded, such as prospective bills consisting of a restatement of the state’s schedule of controlled substances laws without changes to Schedule I psychedelics (e.g. bills adding new analogs to the schedule). Inter-rater reliability26 was evaluated by comparing coding for a subset of bills by an independent rater (DP) for both drug and bill type. For brevity, throughout the rest of this article we will use the terms “bill” and “bills” to refer to both bills and ballot initiatives.

Categorization of decriminalization bills by regulatory frameworks

To assess the variability in decriminalization legislation, the subset of bills proposing decriminalization were further coded based on the description of their specific regulatory framework. These categories included “Physician Involvement” (whether a physician must prescribe the psychedelic or certify a qualifying diagnosis), “Medical Involvement Required” (whether some clinical provider or medical setting, such as a “treatment center”, is required for legal use), and “Training and Licensure Required” (whether the bill indicated that some psychedelic-specific training or licensure would be required to prescribe psychedelics or to facilitate their use).

Comparison of decriminalization bills to state partisanship

To evaluate potential political drivers of decriminalization, political leaning (on the liberal-conservative spectrum) was compared between states with decriminalization bills (active or enacted) and those without. Public data for each state’s 2020 presidential voting margin was used as a proxy for each state’s leaning. To assess trends over time, states with decriminalization bills were further divided into those proposing decriminalization before versus after Jan 1, 2022. Both comparisons were tested using a t-test of two samples, assuming equal variance and 𝝰<0.05 threshold for significance.

Analytic model based on cannabis reforms

Based on the assumption that psychedelics would follow a similar legislative trajectory to cannabis, medical and recreational cannabis decriminalization data27,28 were used to generate two analytic models. In each analytic model, the independent variable was years since the first state passed decriminalization (California legalized medical cannabis in 1996, Colorado legalized recreational cannabis in 2012), the dependent variable was the cumulative number of states passing decriminalization laws. In this analysis, Washington D.C. was counted as a state, thus “the majority of states” was defined as 26/51. Then, using the rate of cannabis reform adoption (states/year) and 2020 as the index case of psychedelic decriminalization (Oregon, both medical and recreational), we modeled the rate of future psychedelics reform adoption. From this, we projected the year by which a majority of states will decriminalize psychedelics.

Results

Summary of Legislation

In total, our search identified 648 unique bills or ballot measures (collectively “bills”). 573 bills not related to psychedelic reform were excluded. One federal bill, US HR7900 (a failed appropriations bill that proposed funding to study treatments, including MDMA and psilocybin, for members of the armed forces on terminal leave) was excluded from further state analysis.

After screening, 25 states have considered 74 bills proposing reform of existing laws restricting access to psychedelic drugs or proposing further research into reform legislation. Of those, 10 (14%) have been signed into law. Those ten laws are from seven states (Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, New Jersey, Oregon, Texas, and Washington) and include one passed by a ballot initiative (Oregon ballot measure 109). Three bills mention decriminalization: Colorado passed a trigger law decriminalizing prescription MDMA contingent on FDA approval; New Jersey reclassified possession of psilocybin as a disorderly offense; and Oregon decriminalized both medical and (effectively) recreational psilocybin. As of August 1, 2022, 32 bills (46%) were dead, and 32 (52%) remained active. The number of new psychedelic reform bills introduced each calendar year has increased from 5 (2019), 6 (2020), to 29 (2021), to 35 (2022, prior to September 28).

Bill Contents

Most bills specifically referred to psilocybin (67, 90%), with many also including MDMA (27, 36%), and relatively fewer included other psychedelics such as LSD, ibogaine, and peyote (Figure 1A). 43 bills (58%) proposed reducing or removing existing penalties for possessing or distributing psychedelic drugs (‘decriminalization’ in Figure 1B). Excluding dead/failed bills, 13 states have signed or were considering decriminalization laws (Fig 1D). Just under half of the bills (31 bills, 42%) specifically called for policy research to explore paths to decriminalization.

Fig 1. Trends in psychedelic drug reform bills.

Bills are categorized by what drug would be affected (A) and in what way (B). Curve in C shows the cumulative number of bills since January 1, 2019 based on the date the bill was first proposed. The map (D) only includes decriminalization bills (reducing or removing criminal penalties for possession of psychedelics). “Some Municipalities” indicates that municipal legislatures (e.g. Oakland, Santa Cruz, Arcata CA, Ann Arbor, DC, Washtenaw County MI, Somerville MA, Cambridge MA, Northampton MA) have passed legislation but not the state, and “Considering” means currently active bills (as of August 1, 2022). Colorado HB1344 (trigger law decriminalizing prescription MDMA contingent on FDA approval) was excluded.

Independent categorization of 53 bills by a second rater yielded very high inter-rater reliability - 100% on all psychedelic drug categories, ‘right-to-try’, and ‘funding’, 98% on ‘decriminalization’ and ‘policy research’, 92.5% on ‘lab or clinical research’.

Bills calling for decriminalization varied widely in the extent to which a regulatory framework was established for the safe and effective use of psychedelics. Approximately half (22/43, 51%) called for legalization of possession of at least one psychedelic drug for therapeutic (15 bills – though the description of ‘therapeutic’ varied widely) or recreational purposes (it was not possible to precisely quantify recreational legalization because circumstances, amount, and penalties varied so widely). Approximately one-third (15/43, 35%) indicated that some training or licensure would be provided to prescribe psychedelics or to provide psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Approximately one quarter (10/43, 23%) mandated that access to psychedelics be restricted to some medical environment, such as a registered treatment center (with the implication that health departments would provide further guidance on treatment center requirements). Only 12% of legalization bills would explicitly mandate physician involvement in prescribing psychedelics or making qualifying diagnoses.

State characteristics

Next, we compared state political leaning (on the liberal-conservative spectrum) to decriminalization. As expected, states considering decriminalization (n=13 states with enacted or active bills, shown in Fig 1D) were more liberal-leaning than states not considering decriminalization (n=37) (11.9% vs −11.1% D-R margin; p<0.001, two tailed t-test). States with decriminalization legislation proposed prior to Jan 1, 2022 (n=9) had a 16.8% D-R margin, while states with first decriminalization legislation proposed in 2022 (n=4) had a 1.1% D-R margin. This trend was not significant (p=0.12, two-tailed t-test). From a geographical perspective, bills introduced before 2022 were mostly in coastal states, whereas in 2022, more midwestern states (MO, CO, KS) have introduced decriminalization bills.

Analytic Model using Cannabis Legalization

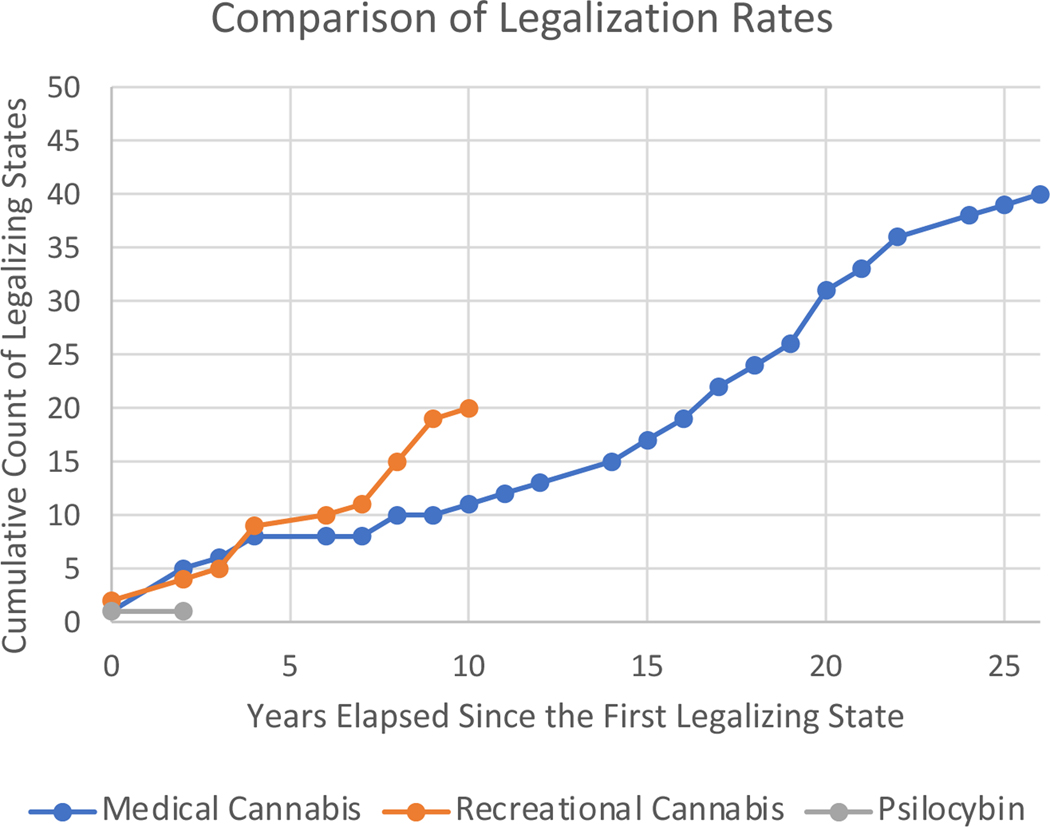

To predict the rate of psychedelic drug reform adoption in coming years, we made the assumption that psychedelics would follow a similar trajectory to cannabis and thus used cannabis legalization data to develop an analytic model. Specifically, we generated two models (medical vs. recreational cannabis) based on the rate of reform adoption (states/year) in the years after the state passed decriminalization. California was the first state to legalize medical cannabis in 1996. In the 26 years since, 40 states have adopted medical legalization at a roughly linear rate (1.53 states per year, 95% CI 1.36–1.7). By comparison, since Colorado legalized recreational cannabis in 2012,19 states and Washington DC have adopted recreational cannabis legalization (2 states per year, 95% CI 1.45–2.23).

Using 2020 as the year of the first psychedelic decriminalization (Oregon, both medical and recreational), the cannabis models predict that a majority of states (26/51) will legalize psychedelics by 2033 (based on the recreational cannabis model) - 2037 (based on the medical cannabis model).

Discussion

This analysis of publicly available data establishes several important findings relevant to developing a cohesive national plan for the safe regulation and administration of psychedelic drugs. First, the momentum behind psychedelic drug reform is increasing. Since 2019, 25 states have considered 74 bills, with 10 already signed into law. The number of bills considered has risen steadily from 5 (2019), to 6 (2020), to 27 (2021), to 36 (2022). Second, bills varied widely in their framework, with a majority proposing decriminalization, of which only a few would require medical oversight and some would not even require training or licensure. Most offer far less detailed guidelines and regulations than Oregon’s approved decriminalizing laws. While early legislative efforts occurred in liberal states, this relationship may be shifting over time, indicating that psychedelic drug reform is becoming a bipartisan issue. While proposed laws differ considerably, all effectively contradict or sidestep the Controlled Substances Act.

It is unusual for a pharmaceutical to be made accessible by legislation rather than FDA regulatory approval, which includes a careful review of drug manufacturing, shipping, efficacy, adverse events, oversight/monitoring, and appropriate post-market monitoring. The American Psychiatric Association released a position statement in July 2022 which concludes “Clinical treatments should be determined by scientific evidence in accordance with applicable regulatory standards and not by ballot initiatives or popular opinion.”10

Based on data from cannabis legalization, we project that most states will have passed legislation legalizing psychedelics by 2033–2037. It is possible that psychedelic reform will occur even more rapidly than cannabis reform due to the higher apparent likelihood of FDA approval, the early shift towards bipartisan legislative support, early interest in reform at the federal level, and the fact that marijuana reform has paved the way for increased access to Schedule I drugs. Alternatively, the path the legalization may be slowed if current FDA applications do not result in approval or the public perceives psychedelics to be more dangerous than cannabis. Another key influence is the amount of money spent on lobbying for legislative reform. New Approach PAC previously focused decriminalizing marijuana but has turned its focus to psychedelics. For example, New Approach has contributed $2.8M in support of Colorado ballot initiative Prop 122 that will be considered in the November 2022 election.29

Perhaps most important are the issues upon which the current decriminalization legislation remains silent: 1) there is no precise mechanism for verifying the chemical content and makeup of drugs procured outside the medical establishment, 2) there is little discussion regarding training, licensure, and monitoring for providers who wish to facilitate treatment (35% of bills delineated treatment requirements, 12% specified physician involvement), 3) the clinical and billing infrastructure for providing psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy has yet to be developed, 4) we do not yet have clinical consensus on pharmacological interactions with co-medications and potential contraindications to treatment (e.g. psychotic disorders or cardiovascular disease)30, 5) there is no information to guide use in special populations like older adults, children, and pregnant women. The minimal involvement of physicians in the majority of these legislations stands in contrast to FDA regulation of esketamine, which includes extensive guidelines regarding medical diagnosis prior to initiation and oversight during treatment.

Despite the relative rapidity with which some have embraced psychedelics as legitimate medical treatments, critical questions about the mechanism of action, dosing and dose frequency, durability of response to repeated treatments, drug-drug interactions, and the role psychotherapy plays in therapeutic efficacy remain unanswered. This last point is critical, as a significant safety concern associated with drugs like psilocybin, MDMA, or LSD is the suggestibility and vulnerability of the patient while under the influence of the drug31. Thus, training and clinical oversight is necessary to ensure safety and also therapeutic efficacy for this divergent class of treatments32,33. Some efforts along these lines are underway in the US34 and Canada35.

Our analysis and interpretation are subject to limitations. First, we treated all proposed legislation equally without regard for likelihood of enactment. Second, our definition of “psychedelic” included MDMA, which has psychedelic effects at higher doses, but is not classified as a classic psychedelic. Third, we counted three bills introduced in prior legislative sessions (e.g. Hawaii SB738 & SB2575) that were reintroduced during the study period. Fourth, our model predicting when states might pass legalize psychedelics relies on the assumption that psychedelic decriminalization will follow a similar trajectory to cannabis decriminalization. Finally, although we have acknowledged the socio-political importance of municipal and federal legislative efforts, they were not included in the analysis.

The data presented above demonstrate that, after decades of harsh legal restriction, the United States are swiftly moving towards increased access to psychedelics. Decriminalization is just one step in a complex process to transform these compounds into safe and effective therapies. This process will have important consequences for the medical and scientific community. Integrating psychedelic treatment into clinical practice will require peeling back many layers of legal prohibition, FDA approval, clarifying prescribing guidelines, and developing treatment models that work for drug makers, physicians, and patients.

Fig 2.

Comparison to Cannabis Legalization

Acknowledgements

We thank Eapen Thampy and Rep. Anthony Lovasco for helping us to interpret legislative trends. This work was supported by the Taylor Family Institute Fund for Innovative Psychiatric Research grant GF0010787, NIMH grant R25 MH112473, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR002345 (ICTS Award #5157), NIDA grant T32DA007261, and McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience Award #202002165, and the Washington University Center for Empirical Research in the Law. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH or other supporting institutions.

Author JSS sits on the scientific advisory board of Silo Wellness (unpaid) and has received consulting fees from Forbes Manhattan. Author GEN has received research support from Usona Institute (drug only). She has served as a paid consultant for IngenioRx, Alkermes, Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. Authors JED and DAP report no relevant conflicts of interest. All authors report no financial in cannabis or psychedelics companies beyond what might be in a broad index fund

References

- 1.Cameron LP, Olson DE. The evolution of the psychedelic revolution. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(1):413–414. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01150-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galvão-Coelho NL, Marx W, Gonzalez M, et al. Classic serotonergic psychedelics for mood and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of mood disorder patients and healthy participants. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238(2):341–354. doi: 10.1007/s00213-020-05719-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COMPASS Pathways. COMPASS Pathways announces positive topline results from groundbreaking phase IIb trial of investigational COMP360 psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression | Compass Pathways. https://compasspathways.com/. Published 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://compasspathways.com/positive-topline-results/

- 4.Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025–1033. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Psilocybin decriminalization in the United States. In: Wikipedia. ; 2022. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Psilocybin_decriminalization_in_the_United_States&oldid=1095120794

- 6.Gael Girón S, Lang B, LeMaster S, Matthews K, McAllister S. Denver Psilocybin Mushroom Policy Review Panel. 2021 Comprehensive Report. City and County of Denver; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oregon Measure 109, Psilocybin Mushroom Services Program Initiative (2020). Ballotpedia. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://ballotpedia.org/Oregon_Measure_109,_Psilocybin_Mushroom_Services_Program_Initiative_(2020) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oregon Psilocybin Services Act (as enacted by the voters). Published online July 2, 2019. https://sos.oregon.gov/admin/Documents/irr/2020/034text.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oregon Secretary of State Administrative Rules. Oregon Health Authority - Division 333 - Psilocybin. https://secure.sos.state.or.us/oard/displayDivisionRules.action?selectedDivision=7102 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Officer K, Campbell C, Oregon criminal justice commission. Impact of Oregon’s Drug Decriminalization on the Oregon Sentencing Guidelines. 2022 National Association of Sentencing Commissioners Annual Conference; 2022. https://www.oregon.gov/cjc/nasc/Documents/Measure%20110%20and%20Oregon%20Sentencing%20Guidelines.pptx [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oregon Health Authority : Measure 110 Oversight and Accountability Council : Behavioral Health Services : State of Oregon. Accessed September 26, 2022. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/hsd/amh/pages/oac.aspx

- 12.SB755 2021 Regular Session - Oregon Legislative Information System. Accessed September 26, 2022. https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2021R1/Measures/Overview/SB755

- 13.Booker, Paul Introduce Bipartisan Legislation to Amend the Right to Try Act to Assist Terminally Ill Patients | U.S. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey. Accessed September 26, 2022. https://www.booker.senate.gov/news/press/booker-paul-introduce-bipartisan-legislation-to-amend-the-right-to-try-act-to-assist-terminally-ill-patients

- 14.SAMHSA Response to Madeleine Dean - DocumentCloud. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/22121426-exhibit-3-response-to-rep-dean-et-al

- 15.McCall B Psychedelics move from agents of rebellion towards therapeutics. Nature Medicine. Published online February 10, 2020. doi: 10.1038/d41591-020-00001-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tullis P How ecstasy and psilocybin are shaking up psychiatry. Nature. 2021;589(7843):506–509. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00187-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Psychedelics as Therapeutics: Gaps, Challenges and Opportunities. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/events/2022/psychedelics-as-therapeutics-gaps-challenges-and-opportunities

- 18.Phelps J, Shah RN, Lieberman JA. The Rapid Rise in Investment in Psychedelics—Cart Before the Horse. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(3):189–190. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.loganlenz. Over $730M Was Invested in Psychedelics in 2021. Psychedelic Invest. Published January 18, 2022. Accessed September 26, 2022. https://psychedelicinvest.com/over-730m-were-invested-in-psychedelics-in-2021/

- 20.Marks M, Cohen IG. Psychedelic therapy: a roadmap for wider acceptance and utilization. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1669–1671. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01530-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith WR, Appelbaum PS. Novel ethical and policy issues in psychiatric uses of psychedelic substances. Neuropharmacology. 2022;216:109165. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith WR, Appelbaum PS. Two Models of Legalization of Psychedelic Substances: Reasons for Concern. JAMA. 2021;326(8):697–698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.BillTrack50 | Federal & State Legislation Tracker. BillTrack50. Accessed July 23, 2022. https://www.billtrack50.com

- 24.Ballotpedia. Ballotpedia. Published 2008. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://ballotpedia.org/Main_Page

- 25.Lexis | Online Legal Research | LexisNexis. LexisNexis. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.lexisnexis.com/en-us/products/lexis.page

- 26.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. SAGE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Where marijuana is legal in the United States. MJBizDaily. Published 2022. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://mjbizdaily.com/map-of-us-marijuana-legalization-by-state/

- 28.State Medical Cannabis Laws. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

- 29.Colorado Proposition 122, Decriminalization and Regulated Access Program for Certain Psychedelic Plants and Fungi Initiative (2022). Ballotpedia. Accessed September 26, 2022. https://ballotpedia.org/Colorado_Proposition_122,_Decriminalization_and_Regulated_Access_Program_for_Certain_Psychedelic_Plants_and_Fungi_Initiative_(2022)

- 30.Bradberry MM, Gukasyan N, Raison CL. Toward Risk-Benefit Assessments in Psychedelic- and MDMA-Assisted Therapies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(6):525–527. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson BT, Danforth AL, Grob CS. Psychedelic medicine: safety and ethical concerns. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):829–830. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30146-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phelps J Developing Guidelines and Competencies for the Training of Psychedelic Therapists. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2017;57(5):450–487. doi: 10.1177/0022167817711304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wexler A, Sisti D. Brain Wellness “Spas”—Anticipating the Off-label Promotion of Psychedelics. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(8):748–749. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NYU Langone Health Establishes Center for Psychedelic Medicine. NYU Langone News. Accessed August 7, 2022. https://nyulangone.org/news/nyu-langone-health-establishes-center-psychedelic-medicine

- 35.Rochester J, Vallely A, Grof P, Williams MT, Chang H, Caldwell K. Entheogens and psychedelics in Canada: Proposal for a new paradigm. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne. 2022;63(3):413–430. doi: 10.1037/cap0000285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]