Abstract

Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy may vary substantially in their clinical presentation, including natural history, outcomes to treatment, and patterns. The application of clinical guidelines for irAE management can be challenging for practitioners due to a lack of common or consistently applied terminology. Furthermore, given the growing body of clinical experience and published data on irAEs, there is a greater appreciation for the heterogeneous natural histories, responses to treatment, and patterns of these toxicities, which is not currently reflected in irAE guidelines. Furthermore, there are no prospective trial data to inform the management of the distinct presentations of irAEs. Recognizing a need for uniform terminology for the natural history, response to treatment, and patterns of irAEs, the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) convened a consensus panel composed of leading international experts from academic medicine, industry, and regulatory agencies. Using a modified Delphi consensus process, the expert panel developed clinical definitions for irAE terminology used in the literature, encompassing terms related to irAE natural history (ie, re-emergent, chronic active, chronic inactive, delayed/late onset), response to treatment (ie, steroid unresponsive, steroid dependent), and patterns (ie, multisystem irAEs). SITC developed these definitions to support the adoption of a standardized vocabulary for irAEs, which will have implications for the uniform application of irAE clinical practice guidelines and to enable future irAE clinical trials.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Self Tolerance, Guidelines as Topic

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy can dramatically improve outcomes for some patients with cancer. The same immune-mediated mechanisms by which these novel agents exert their anti-tumor effects also determine their unique toxicity profiles, specifically, immune-related adverse events (irAEs). The exact pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning irAEs are incompletely understood. ICI-mediated disruption of central and peripheral tolerance1 2 is thought to be a primary driver of irAEs. Humoral immunity,3 cross-presentation of shared tumor and self antigens,4 and epitope spreading5 may also contribute to the development of toxicity. Other factors that have been linked to irAE development include organ-specific expression of immune checkpoints (eg, CTLA-4 on pituitary tissues,6 PD-L1 in renal epithelium7), genetic risk factors,8 and the composition of the gut microbiota.9

The clinical spectrum of irAEs is vast and almost every organ system may be affected. As the immunotherapy community accumulates experience in the diagnosis and management of irAEs, an appreciation has emerged that the natural history of irAEs may be separated into distinct clinical courses: self-limited, waxing and waning, or chronic. Similarly, as more irAEs are treated with corticosteroids or additional immunosuppressives, it is becoming clear that a subset of irAEs fail to improve with corticosteroids, or worsen on weaning of corticosteroids, phenomena sometimes referred to as ‘steroid refractory,’ ‘steroid resistant,’ and/or ‘steroid dependent,’ respectively. For both clinical course and timing and dose of corticosteroids, specific terminology has not been formally defined.

There is a substantial unmet need for uniform terminology related to the diagnosis and management of irAEs. In one analysis, out of 510 terms related to irAEs identified from drug labels, roughly 70% (n=354) were not included in the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).10 To address these gaps, the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) has convened a multistakeholder group that discussed opportunities and provided recommendations on incorporation of irAE terms for the upcoming CTCAE v6.0, and other efforts are ongoing.

The immunotherapy landscape is evolving rapidly, and an appreciation of the distinct phenomenology of irAEs related to their natural history, response to steroids, and multiorgan patterns is maturing. This rapid evolution has been accompanied by inconsistent and shifting terminology related to irAEs. Varying irAE terminologies are used by different stakeholders in academia, community practice, regulatory bodies, and industry. Even within academic medicine, terminology has changed over time and varied between studies. Across a total of 44 published articles including 23,759 patients, only 4 out of the 22 studies that provided a definition of irAEs concretely addressed their own definitions.11 Additionally, assessment of irAEs can be subjective, with independent medical oncologists assigning inconsistent grades and times of onset to the same event,12 further hindering application of guideline-directed irAE care.

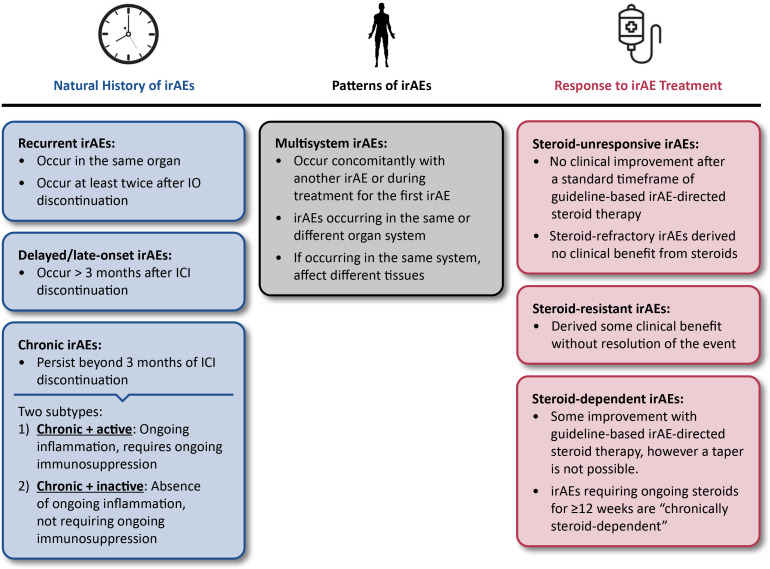

To establish uniform and broadly applicable definitions for irAE terminology, SITC convened a multistakeholder manuscript development group composed of leading experts from academic medicine, industry, and regulatory agencies. The group developed consensus definitions using a modified Delphi process based on the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Definitions were scored for appropriateness via anonymous surveys and then discussed and refined over of a series of consensus meetings to arrive at agreed on terminology. A summary of the definitions for natural history of irAEs, response to irAE treatment, and irAE patterns is provided in figure 1, with supporting rationale, caveats, and notes on application of these terms provided in the associated sections of this manuscript.

Figure 1.

Consensus definitions for irAE terminology. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IO, immuno-oncology; irAE, immune-related adverse event.

The terminology definitions assume that the standard evaluation for irAEs has been performed to rule out other etiologies and are agnostic to the specific ICI regimen being administered. These definitions are intended to support clinicians in the management of irAEs as well as inform future prospective irAE trials and manuscripts.

Methods

The SITC irAE Terminology Definitions Consensus Panel was composed of 17 participants, including three Chairs. The consensus panel Chairs developed initial survey items for the definitions based on an extensive literature review and their clinical experience. The entire consensus panel anonymously rated the survey items for appropriateness on a nine-point Likert scale and provided free text comments in an electronic form. Appropriateness based on numeric ratings was determined using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.13 Briefly, median scores for each item were categorized into ranges (1–3 not appropriate, 4–6 uncertain, 7–9 appropriate). Consensus was defined as a median rating within the 7–9 range without disagreement, with disagreement defined by one-third (or more) of ratings in both extremes outside of the three-point range containing the median. Survey results and free-response comments were compiled and discussed over the duration of three consensus meetings of the entire consensus panel. During the meetings, definitions that did not reach appropriateness were either eliminated or modified and subjected to repeat evaluation either live during the meetings or during follow-up surveys. Definitions that were deemed appropriate but were considered to require additional nuance, caveats, or modification were also discussed and refined at the meetings. All the statements appearing in the final manuscript were reviewed and agreed on as appropriate by all members of the consensus panel.

Consensus definitions on natural history of IRAEs

Clinical manifestations of irAEs vary substantially and there are no validated predictors for the identification of patients who will experience an irAE, the timing of onset, duration of toxicity, nor likelihood of re-emergence. Furthermore, while it is generally accepted that irAEs can re-emerge, be chronic, and/or delayed, the definition and application of these terms has been highly heterogeneous. In order to assist providers in the application of clinical practice guidelines, lay the foundation for future clinical trials to identify optimal interventions for the varied clinical presentation of irAEs, support consistent reporting of safety results in oncology trials, and support future meta-analyses and systematic reviews, consensus definitions related to the natural history of irAEs were developed.

Re-emergent irAEs

Many irAEs resolve after halting ICI therapy and treatment with immunosuppression, most commonly corticosteroids. Some irAEs persist long term, as discussed in more detail in the Chronic irAEs section. Many patients who experience an irAE of grade <4 will be rechallenged with ICIs on resolution.14 The rates of re-emergence of irAEs on rechallenge have varied widely across reports, ranging from 10% to 40%.15–23 Conflicting data have also been published on the likelihood of irAE re-emergence affecting specific organ systems. As an example, colitis has been described as both a highly uncommon18 19 and the most common15 16 irAE to re-emerge. This variability may be partially explained by heterogeneity in patient populations studied, ICIs administered (eg, anti-PD-1 monotherapy vs in combination with anti-CTLA-4), and definition of the term re-emergent by the respective authors.

Clinical presentation of re-emergent irAEs

It is important to differentiate between re-emergence of a distinct irAE and disparate irAEs occurring in sequence. Specific populations of autoreactive cells are likely responsible for toxicity within individual organ systems (eg, colon tissue-resident memory T cells in the case of ICI-induced colitis24 25 or islet-antigen specific CD8+ T cells for ICI-associated autoimmune diabetes mellitus26). For this reason, the consensus panel identified that irAEs affecting different organ systems than the original event should not be included in the definition of re-emergence. Of note, it is possible for irAEs to affect several organs simultaneously, as described in more detail in the Multisystem irAEs section, which represents a separate natural history than re-emergent irAEs.

Re-emergent irAEs are also different from an ongoing toxicity that waxes and wanes in intensity. There was agreement that achievement of complete resolution of the original irAE event (ie, absence of all clinical signs and symptoms as opposed to resolving to grade 1) is required in order to define the same irAE as re-emergent. Additionally, there was consensus that re-emergence of an irAE must generally be clinically evident as a recurrence of clinical symptoms (ie, deterioration in labs or imaging alone do not qualify as re-emergence). An exception to this rule is for irAEs that are typically asymptomatic at low grades and defined by laboratory values such as hepatitis or pancreatitis, in which case deterioration on labs alone qualifies as re-emergence. If an irAE improves with appropriate intervention (ie, holding of immunotherapy and initiation of steroids) but does not completely resolve and subsequently worsens when the irAE-directed intervention is withdrawn, the event is defined as steroid-dependent (discussed in more detail in the Response to treatment section).

A clinical situation that warrants special characterization is re-emergent irAEs in patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders. Multiple retrospective studies27–30 and meta-analyses31 32 have demonstrated that even though both de novo irAEs and flares are common in patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease, events are typically mild and manageable. Accordingly, the definition for re-emergent irAEs is no different for patients who have underlying autoimmune disease versus those who do not. Patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease do, however, warrant close monitoring and multidisciplinary consultation during ICI therapy.

Separately, patients may discontinue immunotherapy for reasons other than toxicity, including financial or social reasons, attainment of maximal clinical benefit, or completion of adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy. In cases where ICIs are stopped for any reason and subsequently restarted, there was consensus that irAEs re-emerging on rechallenge should be included in this definition for re-emergent irAEs. In cases where an irAE occurs after cessation of ICI therapy, toxicity may theoretically represent a newly arising autoimmune disorder rather than reactivation of latent autoreactive cells responsible for the first event. Attribution is further complicated because signaling through immune checkpoints is implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple rheumatologic conditions, such as CTLA-4 in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome33 and PD-1 in rheumatoid arthritis,34 raising the possibility that treatment with an ICI may cause a patient to become susceptible to the development of autoimmune disorders. Importantly, the management of autoimmunity does not necessarily differ based on whether it is occurring de novo or as a re-emergent irAE. Additionally, there was agreement that re-emergent irAEs may occur after treatment is permanently discontinued. To consider an irAE as re-emergent if it occurs after therapy has been halted, however, a link between contemporary toxicity and prior events on-treatment is necessary.

Time frame for re-emergent irAEs

Attribution of a re-emergent irAE is relatively straightforward if a patient is still receiving active therapy. The etiology of autoimmune toxicity arising months or even years after a patient has discontinued ICI treatment is more ambiguous. ICIs may persistently occupy their target receptors for longer than predicted by the serum half-lives of monoclonal antibodies—nivolumab was shown to occupy PD-1 on T cells for several hundred days after the last dose in phase I pharmacodynamics studies.35 Even on clearance of the ICI, the immune system likely remains activated for long periods of time. In addition, there may be a discrepancy between the ‘time of symptom onset’ versus the ‘time presenting for medical attention,’ especially because subclinical irAEs may persist without recognition by a treating provider or the patient. Sometimes even when the symptoms are recognized, logistical barriers can prevent the establishment of a definitive diagnosis, such as delays in scheduling an appointment with a subspecialist. As an example of this, in one analysis of patients who developed inflammatory arthritis secondary to ICI treatment, the average delay between patient-reported development of joint symptoms and diagnosis by a rheumatologist was 5.2 months.36

Extremely limited data are available on the re-emergence rates for irAEs at late time-points after discontinuation of ICI therapy. Though most clinical trials do not mandate safety data reporting beyond 90 days after discontinuation of therapy, long-term follow-up from registry studies for ICIs as well as real-world data support the possibility for irAEs to occur months or even years after treatment. In one study, the overall rate of irAEs occurring >12 months after initiation of therapy was roughly 5%.37 Notably, re-emergence of a prior irAE was rare in this analysis. Among the subset of patients with prior irAEs, 86% of the later irAEs affected a different organ than the original event.37 Adverse events occurring more than 100 days after the last dose of study therapy were reported in 4% (18 of 452 patients) receiving adjuvant nivolumab and 6% (25 of 453 patients) receiving adjuvant ipilimumab in CheckMate 238, with some patients experiencing more than one irAE.38 These data may be incomplete, however, as reporting was encouraged but not required by the study protocol.

There was an extensive discussion by the consensus panel regarding whether an upper threshold should be established for the time from discontinuation of therapy after which an irAE should be suspected to represent de novo toxicity as opposed to a re-emergent irAE event. Myocarditis or pneumonitis39 were noted as presentations that may confound attribution as re-emergent irAEs or de novo events arising from infectious etiology. Ultimately, the consensus was that time is an independent variable. Therefore, clinicians should increase the priority of identifying an alternative etiology for suspected irAE events with longer time periods since discontinuation of ICI therapy. There was agreement that while suspicion of de novo toxicity becomes more prominent after the 1-year mark, it is possible for re-emergent irAEs to occur at any time after discontinuation of therapy. Data are lacking on irAEs recurring beyond 2 years as most trials only follow patients for a finite period of time. A need for long-term follow-up and toxicity reporting in future studies was emphasized. Even though the likelihood of re-emergent irAEs decreases over time, there was unanimous agreement that physicians should follow patients who have received immunotherapy long-term and that registries are needed to capture health outcomes and events for several years after cessation of therapy. Taken together, the consensus definitions for re-emergent irAEs are summarized in box 1.

Box 1. Consensus definition for re-emergent immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Re-emergent irAEs:

Occur in the same organ and occur at least twice.

Occur after a patient has temporarily or permanently discontinued immune checkpoint inhibition.

Must completely resolve while a patient is not actively receiving immunotherapy, with re-emergence of symptoms with or without re-starting the immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Must have a well-established association with the prior immunotherapy treatment if occurring after discontinuation of immune checkpoint inhibition.

May occur at any time after discontinuation of immunotherapy, however, other potential causes should be investigated for events occurring more than 1 year after the last dose of the immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Chronic irAEs

The prevalence of chronic irAEs has been underappreciated until recent years. Because initial clinical trials evaluating ICIs only enrolled patients with metastatic disease, long-term follow-up was complicated by high frequencies of subsequent therapies, comorbidities, and deaths. A subset of patients with metastatic cancer, however, attain durable disease control even after discontinuation of ICIs,40–44 and an ever-increasing number of long-term survivors are now available for follow-up. Chronic irAEs have also become more apparent as ICIs demonstrate benefit and gain United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings.38 45–48

Substantial variability exists in the application and understood meaning of the term ‘chronic’, both in terms of duration of toxicity and whether the time frame is measured from initiation or discontinuation of ICIs. Chronic is a term with varied interpretations and applications across medicine and public health.49 For the purposes of these definitions, chronic is used in its most fundamental sense as an adjective describing long-term continuity. There was consensus that the definitions for chronic should be independent of and agnostic to the irAE-directed treatment applied. However, the definition also assumes that irAEs were managed according to current guidelines (ie, temporary or permanent discontinuation of ICIs for events of grade ≥214).

The reported median time to irAE resolution has ranged from 14 days50 to 60 days51 across studies. irAEs persisting long after cessation of treatment have been reported in the long-term follow-up from registrational trials of ICIs42 as well as pooled analyses and real-world reports.52–56 Persistent sequelae were observed in 42.9% of patients treated with pembrolizumab and 24.3% of patients treated with ipilimumab in a systematic review of irAE case reports.56 Another analysis including 437 patients with metastatic melanoma or lung cancer treated in the standard of care setting found an overall incidence of irAEs lasting longer than 6 months of 35.2%.54 In the adjuvant setting, irAEs persisting beyond 12 weeks after anti-PD-1 discontinuation were reported in 43.2% of patients with resectable stage III–IV melanoma.53 irAEs lasting for >6 months were described in 53% of a series of 2,750 patients with lung cancer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center treated with immune checkpoint blockade from 2011 to 2020, with 5 of 18 patients with colitis, 2 of 4 patients with pneumonitis, and 3 patients with neuromuscular irAEs having symptoms for more than 1 year.55

In order for an irAE to be defined as chronic, other etiologies must be ruled out (eg, infection or malignancy for immune-related neuropathy57). Prior analyses have used differing time thresholds to identify irAEs as chronic, ranging from 12 weeks53 to 6 months54 or more. There has also been inconsistency in the inclusion of metronomic events interspersed with resolution in the reports of chronic irAEs. For the purposes of these definitions, chronic irAEs are considered continuous ongoing toxicity persisting after ICI discontinuation and the waxing and waning events are accounted for in the earlier definitions in the Recurrent irAEs section.

There was debate about the appropriate time frame to define chronic irAEs. It was agreed that the time frame for chronicity should be based on the assumed persistence of ICIs in serum (ie, IgG4 monoclonal antibodies with half-lives on the order of 19–26 days35 58 59). As such, 3 months after the last dose of ICI administered was agreed on as a reasonable lower limit to define chronic irAEs. There was acknowledgment that the immunological perturbations induced by checkpoint blockade—differentiation of tissue-resident memory T cells into cytotoxic effectors,24 for example—would be expected to persist long after clearance of the ICI antibody. Terminology to describe irAEs that are non-chronic was determined to be problematic as ‘self-limiting’ may imply that no management was attempted and ‘acute’ could be interpreted as rapid onset.

Active versus inactive chronic irAEs

Most descriptions of chronic irAEs do not distinguish between toxicity that is associated with active inflammation (eg, immune-mediated colitis24) versus permanent damage to the affected organ (eg, salivary gland scarring leading to xerostomia60 or thyroid dysfunction61). The concept of distinguishing between smoldering inflammation versus permanent tissue damage has previously been proposed,62 but most event reporting does not take into account whether symptoms represent ongoing immune-mediated destruction or residual damage. There was recognition that long-term symptoms arising due to persistent inflammation are distinct from sequelae of organ or tissue damage. Because of the implications for management, the consensus panel agreed that distinct definitions for chronic irAEs driven by inflammatory processes and those driven by symptoms of tissue injury are needed.

A new terminology was suggested to differentiate chronic irAEs that may be considered reversible with immunosuppression versus those that are managed with supportive measures (eg, hormone replacement for endocrinopathies63). It was put forward that few of the irAEs generally considered chronic are genuinely ‘ongoing’ in the sense of persistent inflammation and active tissue injury, but rather, many long-lasting irAEs such as alopecia,64 vitiligo,65 neuropathies,57 xerostomia,60 and endocrinopathies61 arise due to irreversible tissue damage. The distinction between irAEs that reasonably may be expected to respond to anti-inflammatory interventions versus those for which steroids would be considered futile has important implications for toxicity management. Endocrine toxicities are often used as the paradigmatic example of irAEs that generally are not expected to improve with immunosuppression—high-dose glucocorticoids have demonstrated no effect on either the median duration of thyrotoxicosis or maintenance dose of levothyroxine in patients with ICI-related thyroid disorders,66 and high-dose glucocorticoids have conferred no obvious benefit over low-dose steroids for patients with anti-CTLA-4-associated hypophysitis.67 However, it was noted that other organs and systems may be affected by non-inflammatory long-term damage and that not all endocrinopathies are irreversible.

The group agreed that the definitions for the distinct categories of chronic irAEs should follow from the presumed underlying etiology. Although direct measurement of underlying inflammation in an affected tissue is not clinically feasible in most cases, it was agreed that events for which a clinician would reasonably attempt reversal with immunosuppression or anti-inflammatory agents should be considered as active. Conversely, events that are managed without immunosuppression (eg, hypothyroidism61 63) were agreed to represent inactive irAEs. It was noted that the reversibility with immunosuppression, and thus active/inactive phenotype, of an irAE may only be known retrospectively. Finally, chronic active and inactive irAEs likely represent opposite ends of a bimodal distribution of a continuum of possible clinical activity, and there are events that may fall between these discrete entities along the spectrum. As an example, the severity of inflammatory pathology and symptomology may vary substantially in ICI-associated myocarditis, including cases where biopsy reveals inflammatory infiltrate without myocyte loss68 or smoldering myocarditis with otherwise minimal signs and symptoms.69 On the opposite end of the spectrum, progressive vitiligo beginning on photoexposed areas and spreading throughout the body despite sparse inflammatory cells infiltrating depigmented lesions has also been described.70 Taken together, consensus definitions for chronic irAEs are summarized in box 2.

Box 2. Consensus definitions for chronic immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Chronic irAEs:

irAEs that persist beyond 3 months of immune checkpoint inhibitor discontinuation.

An irAE is defined as chronic and active if it persists in the setting of ongoing inflammation of an organ and requires ongoing immunosuppression (eg, colitis, inflammatory arthritis).

An irAE is defined as chronic and inactive if it persists in the absence of ongoing inflammation in the affected organ and does not require ongoing immunosuppression (eg, selected endocrinopathies, neuropathies).

Delayed/late-onset irAEs

Although irAEs may occur at any time while a patient is receiving therapy or after ICI treatment has been permanently discontinued, the majority of irAEs occur within the first 3 months of treatment initiation.52 71 The median time to initial onset of irAEs has been reported as ranging from 2.2 to 14.8 weeks after initiation of treatment depending on the affected organ system,52 although some irAEs, such as myocarditis, have more rapid-onset and frequently occur after a single dose of ICI therapy.51 With more long-term follow-up data available, the potential for new or re-emergent irAE events arising long after a patient has discontinued therapy is becoming apparent.37 51 72 73

Although the overall incidence of late-onset irAEs is not known, available analyses have reported rates of around 5%.37 Severe late-onset irAEs have been described after ICIs are discontinued due to toxicity72 as well as in the adjuvant setting. irAEs arising more than 100 days after the last dose of therapy were reported in 4% (18 of 452 patients) receiving nivolumab and 6% (25 of 453 patients) receiving ipilimumab in CheckMate 238.38 In the advanced disease setting, a pooled analysis of safety outcomes among patients receiving pembrolizumab treatment for melanoma in KEYNOTE-001, KEYNOTE-002, and KEYNOTE-006 describe new irAEs occurring more than 160 weeks after treatment initiation in 3 of 429 patients still on-study.74

For the purposes of these terminology definitions, ‘delayed’ and ‘late-onset’ are used interchangeably. This definition is intended to capture irAEs occurring after the period of maximal immune activation when ICIs are actively interrupting checkpoint-ligand signaling. Therefore, this definition requires that events occur after a patient has discontinued ICI therapy. Of note, delayed or late onset irAEs include both de novo toxicity or recurrences of prior events. Regardless if the event is the first occurrence or a re-emergence, as the time since the last dose exceeds the 1-year mark, the likelihood of an alternate etiology increases, as discussed in more detail in the Time frame for re-emergent irAEs section. Viral infection is an example of an alternate etiology that may confound attribution, as viruses may cause acute inflammatory pathology, such as in myocarditis,75 as well as trigger chronic autoimmune conditions including type 1 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren’s syndrome.76 Case reports have emerged of Epstein-Barr virus infections being associated with immune-related cerebellar ataxia77 and encephalitis,78 as well as COVID-19-triggered acute tubular interstitial nephritis,79 all while the patients were still in the acute treatment phase. Partially due to limited data available on delayed or long-term irAEs and a paucity of animal models, it is not known if there is a link between ICI treatment, intercurrent infections, and the development of autoimmune disorders. Dedicated registries are needed that incorporate long-term follow-up of patients after they complete treatment with ICIs, in order to collect these data.

Similar to chronic irAEs, the time frame that defines late-onset irAEs is based on the expected persistence of ICIs in serum. As discussed in the Clinical presentation of chronic irAEs section, for IgG4 monoclonal antibodies, five half-lives amount to roughly 3 months. As such, it was agreed that irAEs occurring 3 months or longer after the last dose of irAEs administered should be defined as delayed or late onset. As with recurrent irAEs, de novo autoimmune conditions should also be considered in the differential diagnosis and the suspicion of an alternate etiology, such as viral infection, should increase concomitantly with the time past 1 year after the last dose of immunotherapy. The consensus definition for delayed/late-onset irAEs is provided in box 3.

Box 3. Consensus definition for delayed/late-onset immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Delayed/late-onset irAEs:

Manifest more than 3 months after discontinuation of immunotherapy.

Consensus definitions on response to treatment of IrAEs

At the time of manuscript writing, corticosteroids are considered the standard of care first-line intervention for many irAEs,14 with the exception of chronic inactive irAEs such as endocrinopathies, which require hormonal replacement therapy.80 The first-line intervention for non-life-threatening irAEs is typically 1 mg/kg of prednisone (or equivalent) with a taper of at least 4 weeks on resolution of symptoms.14 For active irAEs, rapid identification of toxicity and initiation of treatment with corticosteroids is crucial. However, a proportion of irAEs fail to improve with steroid treatment, whereas others may initially resolve and then recur on steroid weaning. The utilization of steroids for irAE management has been found to be highly variable, with some patients receiving prolonged courses of glucocorticoids without substantial improvement in irAE symptoms.81 82 Real-world and retrospective data support the use of alternate immunosuppressive agents such as infliximab or vedolizumab,83 mycophenolate mofetil,84 or tocilizumab85 for management of steroid-refractory irAEs. No prospective studies, however, have evaluated the optimal approach to managing irAEs that do not respond to first-line glucocorticoids. These definitions provide clinical parameters for the identification of steroid-unresponsive and steroid-dependent irAEs, however, as alternate immunosuppressive agents are used these terms may also be applied to these agents.

Steroid-unresponsive irAEs

The terminology surrounding irAEs that do not improve with steroid treatment may be ambiguous. Generally, ‘steroid-refractory’ implies no benefit with steroids, and ‘steroid-resistant’ implies some benefit without resolution of the event or an inability to wean from steroids. As such, these consensus definitions put forth ‘steroid-unresponsive’ to encompass irAEs with any deviation from the expected natural history of response to steroids, including a lack of improvement as well as symptom worsening. The overall incidence of irAEs that do not respond to first-line steroids has varied widely across reports, depending on the tumor being treated and the organ affected. For pneumonitis, one report described an incidence rate of 18.5% for steroid-refractory toxicity.86 Colitis and diarrhea may require second-line or third-line immunosuppression in more than half of cases.87 88 In one of the larger retrospective analyses including 2,750 patients with lung cancer treated with ICIs, approximately 1 in 5 of all patients receiving steroids required additional immunosuppression.55 No validated biomarkers exist to predict a need for subsequent-line immunosuppression, although patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders may be at higher risk for developing steroid-unresponsive irAEs89 and endoscopic features as well as histological ulcerations87 have been associated with increased risk of developing steroid-refractory colitis.88

There was consensus that any degree of improvement (even minor) with steroids distinguishes steroid-dependent irAEs from steroid-refractory irAEs. Definitions for irAEs that improve as expected with steroids but do not tolerate weaning are provided in the Steroid-dependent irAEs section. This distinction has been used in other analyses, with slightly different terminology applied to the distinct categories.55 For these definitions, it is assumed that guideline-directed steroid therapy in terms of appropriate dosing and route of administration has been attempted. Consensus definitions for steroid-unresponsive irAEs are summarized in box 4.

Box 4. Consensus definitions for steroid-unresponsive immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Steroid-unresponsive irAEs include:

irAEs in which there is no clinical improvement after a standard time frame of guideline-based irAE-directed steroid therapy.

Steroid-refractory irAEs are those that derived no clinical benefit with steroids.

Steroid-resistant irAEs derived some clinical benefit without resolution of the event.

Life-threatening versus non-life-threatening irAEs:

For life-threatening irAEs (eg, pneumonitis, myocarditis, colitis), steroid-unresponsive irAEs are those in which there is no clinical improvement after 1–3 days of appropriate irAE-directed steroid therapy.

For non-life-threatening irAEs (eg, arthritis), steroid-unresponsive irAEs are those in which there is no clinical improvement after 7–14 days of appropriate irAE-directed steroid therapy.

The definition of steroid-refractory irAEs has important implications for informing the time interval to wait before offering additional lines of immunosuppression. There was general agreement that escalating an intervention early is warranted for some irAEs—patients with colitis, in particular, have demonstrated benefit with earlier administration of infliximab or vedolizumab.90

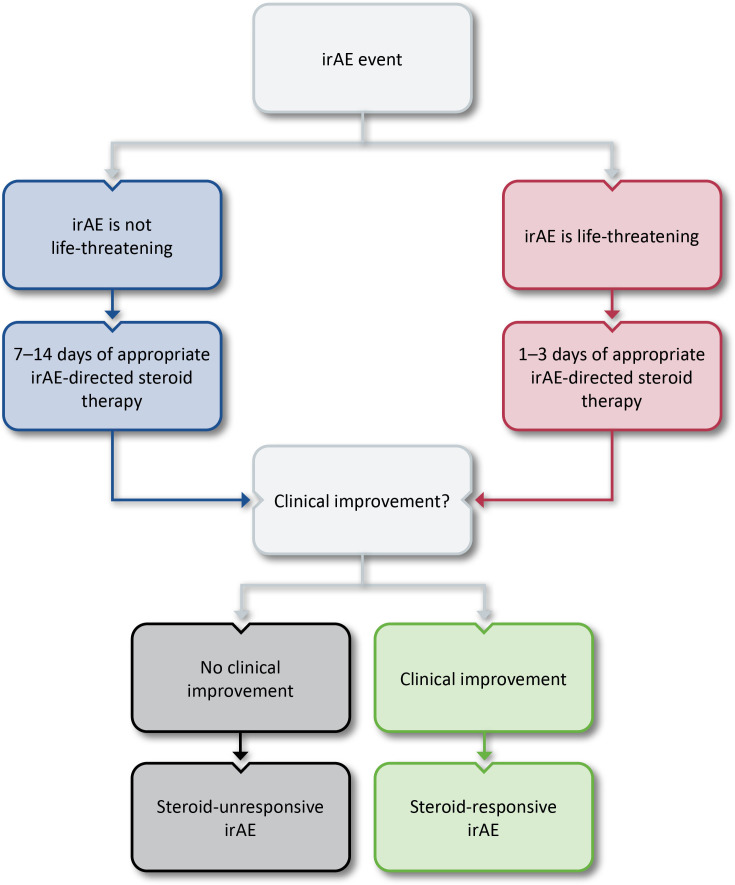

Concern was raised that specifying a standard time frame for steroid treatment for the definition may encourage prolonged futile use of steroids for life-threatening irAEs such as myocarditis. As such, the group agreed that the definitions for steroid-responsive irAEs are different for life-threatening and non-life-threatening toxicities. Ultimately, a range of 1–2 weeks of steroid treatment was agreed on as appropriate to evaluate whether irAE symptoms are responding to non-life-threatening events. For life-threatening irAEs, 1–3 days was decided as the range of steroid exposure before declaring futility. An algorithm for the identification of steroid-unresponsive irAEs is provided in figure 2. Regardless of the original event, however, escalating intervention is warranted if a patient is clinically deteriorating.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for the identification of steroid-unresponsive irAEs. irAE, immune-related adverse event.

Steroid-dependent irAEs

Although many irAEs improve with initiation of corticosteroids, deterioration on weaning is sometimes observed. It was agreed that this phenomenon is distinct from irAEs that do not display any improvement with steroids (as described in the Steroid-unresponsive irAEs section). Sparse data are available to estimate the overall incidence of irAEs that do not tolerate weaning, due, in part, to a lack of generally accepted terminology as well as inconsistent reporting.

Whether the definition for steroid-dependent irAEs should address time on treatment and need for steroids was controversial, especially given the concept of active versus inactive irAEs (see the Chronic irAEs section for detailed discussion on the definitions and implication for management). It was established that steroid dependence should not be defined by time, but by symptomology/response (or lack thereof). It was further agreed that if an initial steroid wean fails, then a slower taper might be attempted before labeling the irAE as ‘steroid dependent’. Distinct from the definitions of recurrent irAEs where clinical deterioration is required, low-grade or subclinical irAEs (eg, mild amylase elevation) that worsen when steroids are weaned but do not necessarily preclude a taper are included in the steroid-dependent category. Consensus definitions for steroid-dependent irAEs are summarized in box 5.

Box 5. Consensus definitions for steroid-dependent immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Steroid-dependent irAEs:

Steroid-dependent irAEs are irAEs in which there is some improvement with guideline-based irAE-directed steroid therapy, but a taper is not possible.

irAEs that require ongoing steroids for greater than or equal to 12 weeks are classified as ‘chronically steroid dependent’

Although steroid dependence was agreed on to be defined by symptoms and response rather than a specific time frame on treatment, the group acknowledged a need for a definition encompassing the irAEs that improve after a long course of steroids and then recur with weaning, in contrast to irAEs that require long courses of steroids and never improve. Chronically steroid-dependent irAEs include both those in which corticosteroids cannot be weaned even though a second immunosuppressive agent was started regardless of response to this second agent, and those that require the initiation of a second immunosuppressive agent for successful weaning.

The required time frame for an irAE to be considered chronically steroid dependent was debated. The median time on glucocorticoids in patients experiencing irAEs has varied across reports and system affected. One pan-irAE analysis reported a median time on glucocorticoids of 61 days,81 though response to steroids was not addressed. The median duration until initiation of second-line immunosuppression for irAEs categorized as ‘steroid-resistant’ (ie, initial response and inability to taper off systemic steroids) was 150 days.55 Ultimately, 12 weeks of steroids was accepted as an appropriate time frame to define irAEs as chronically steroid dependent. It was noted that the 12-week time frame is frequently used by pharmaceutical companies for the definition of chronic or long-term steroid use in non-irAE contexts, further supporting these definitions. There was emphatic agreement that for irAEs to be defined as chronically steroid dependent, patients must not be receiving immunotherapy during an attempted taper.

Consensus definition of multisystem IrAES

Clinical trials have typically reported irAEs on a per-organ basis. There is increasing recognition, however, that irAEs may occur simultaneously in multiple organs and systems. Optimal management for multiple simultaneous irAEs is challenging and may involve concurrent high-dose steroids, hormone replacement, and/or second-line immunosuppression depending on the organs and systems affected and the severity of the individual events. The ASCO-SITC Trial Reporting in Immuno-Oncology guidance, a set of consensus recommendations intended to provide more complete evidence on the relative risks versus benefits of immunotherapy approaches,91 is silent on multisystem irAEs, highlighting a need for consensus definitions to assist in the identification and characterization of overlapping toxicity.

Case reports and retrospective analyses have described multisystem irAEs as those affecting a variety of organs and systems. Although limited data are available to estimate the overall incidence, two independent analyses described multiorgan irAEs occurring at a rate of roughly 5%92 93 and a separate study found an incidence of 9%.94 Several studies have identified a positive correlation between multiorgan irAEs and improved survival outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma,95 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),92 and across multiple solid tumors.96

No clear pattern for the organs and systems most likely to be affected by simultaneous toxicity has emerged in published reports of multisystem irAEs. Clustered toxicity has been well characterized in rare but frequently lethal irAEs, with myasthenia gravis being accompanied by myositis and myocarditis at rates of 16% and 9%, respectively.97 The overall incidence for overlapping non-fatal toxicities is less well described. Pneumonitis accompanied by dermatologic toxicity was identified as the most common multi-system irAE in patients with NSCLC receiving a variety of anti-PD-(L)1-based ICI regimens,92 whereas skin irAEs or laboratory abnormalities were identified as the most likely to cluster with other events in a separate analysis of patients with NSCLC undergoing atezolizumab treatment.93 ICI-related interstitial lung disease has also been associated with a two-times higher incidence of irAEs affecting other organs and tissues (68.4% vs 33.7%).98

The group agreed that a multisystem irAE may affect multiple organs within the same system. Polyglandular endocrinopathies presenting as anterior hypopituitarism plus thyroiditis, hypothyroidism, Graves’ disease, or type 1 diabetes mellitus have all been described.80 Concurrent dermatologic irAEs accompanied by other toxicities have also been reported, including one case of NMDA receptor antibody encephalitis accompanied by atopic dermatitis and progressive vitiligo.99

There was agreement that irAEs do not necessarily have to occur within a specific time frame to be defined as multisystem. Delayed and sequential multisystem irAEs have been reported, such as colitis with chronic inflammatory changes followed by an onset of hepatitis 19 days later, and pneumonitis, nephritis, and pancytopenia over the subsequent 4 weeks.37 It was noted that treatment of the first irAE to present may mask a concurrent multisystem irAE. As such, irAEs arising during a taper for the first irAE to present should be considered to be concurrent multisystem irAEs. Sequential and different irAEs that resolve or require no further treatment between individual events are not considered to be multisystem. Taken together, the consensus definitions for multisystem irAEs are summarized in box 6.

Box 6. Consensus definitions for multisystem immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Multisystem irAEs:

Occur concomitantly with another irAE or during treatment for the first irAE.

Refer to irAEs occurring in the same or different organ systems, and if occurring in the same organ system, then affecting different tissues (eg, thyroiditis and adrenal insufficiency).

Limitations

These definitions were developed based on expert consensus and the available data at the time of publication. There may be some scenarios that are incompletely accounted for by these definitions, and additional studies with robust reporting of events, integrated biomarker programs to identify reliable surrogates for immunologic pathology, and long-term follow-up are needed.

One such example of a clinical scenario that can be difficult to classify is the attribution of toxicity to an individual agent in patients receiving combination ICI regimens that include chemotherapy or targeted therapy. Furthermore, while some adverse events are associated with an overt inflammatory pathology that is clearly immune-related, other irAEs, such as fatigue, have no apparent connection to an immunologic etiology. Fatigue is further complicated by the contributions of the patient’s underlying disease and psychosocial aspects. Data from the rheumatology field have demonstrated that fatigue is a sequela of pain rather than disease activity100 and that the group-level effects of anti-inflammatory biological agents on fatigue are minimal.101 Resolution of symptoms with immunosuppression is one indicator that an event is immune-mediated, but the possibility for an irAE to be steroid unresponsive cannot be ignored when considering the potential attribution. Histological confirmation of an inflammatory infiltrate in the affected tissue also provides evidence that an adverse event is immune related, but biopsies are not always available or indicated. Additional studies to identify and validate clinically available correlates of immune toxicity are needed.

In some cases, signs and symptoms of irAEs may be absent but histopathological evidence of low-level inflammation persists in organs. The classification of these irAEs as chronic, steroid dependent, or resolved in such scenarios is challenging and will vary between organ systems. As discussed in the Chronic irAEs section, collagen fibrosis and lymphocytic inflammation consistent with chronic smoldering myocarditis has been described in a patient treated with ICIs who experienced symptom rebound when a steroid taper was attempted after troponin normalization.69 Ultimately, the management of most irAEs is guided by symptomology, and thus, even in organs easily available for biopsies such as the colon, the decision to continue or escalate immunosuppression will be informed by a clinical assessment in addition to the available histopathological information.

Conclusion

The definitions in this manuscript provide readily clinically applicable parameters for the classification of irAEs. These definitions were developed based on the expert consensus of the SITC irAE Terminology Definitions Consensus Panel and the interpretation of the available evidence at the time of publication. As such, limitations in the published data and the application of these definitions were identified, including a need for long-term follow-up and reporting. Priority areas for future research include biomarkers for predicting the onset and clinical outcomes of irAEs as well as alternative first-line management strategies beyond corticosteroids. The relationship between the natural history of irAEs and outcomes with ICIs also remains to be elucidated. Additionally, the definitions provided in this manuscript focus on irAEs associated with ICI therapy. Other immunotherapy approaches, such as adoptive cell therapies are also increasingly advancing through clinical development in the solid tumor space, and T cell engaging antibodies as well as chimeric antigen receptor T cells are a cornerstone of later-line therapy for hematologic malignancies in eligible patients. While some of the concepts from the definitions provided may be applicable to other immunotherapy modalities beyond ICIs, the mechanisms of action for the toxicities associated with adoptive cell therapies or T cell redirecting therapies are distinct compared with ICIs, and thus the natural histories are likely not identical.

A generally accepted and shared vocabulary for irAEs is essential to standardize the application of clinical practice guidelines and offer the best treatment to patients. The application of these definitions to future prospective trials may assist in the identification of optimal management strategies as well as biomarker discovery and will further facilitate harmonization in guidelines, review articles, and subsequent consensus statements related to irAEs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank SITC staff including Sam Million-Weaver, PhD for medical writing support and Claire Griffiths, MD, MPH, Angela Kilbert, and Nichole Larson for project management and editorial assistance. Additionally, the authors thank SITC for supporting the manuscript development.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DrJNaidoo, @jriemer3

Contributors: JN, LCC and CM served as chairs of the SITC irAEs Terminology Definitions Consensus Panel and led the initial outline development, survey creation, and consensus meeting facilitation and thus are listed as first, final, and second author, respectively. All other authors participated equally in the consensus development process as well as provided critical review and conceptual feedback on manuscript drafts and thus are listed alphabetically.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: JN—Consulting fees: AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Roche/Genentech, Takeda, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo; Contracted research: AstraZeneca, Merck; Data Safety Monitoring Board: Daiichi Sankyo; NPI: 1710327721. LCC—Consulting fees: AbbVie; Contracted research: Bristol-Myers Squibb. CM—Nothing to Disclose. MBA—Consulting fees: Aveo, BMS, Eisai, Exelixis, Genentech, Iovance, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Pyxis, Werewolf, Asher Bio, Calithera, Idera, Agenus, Apexigen, Neoleukin, Adagene, AstraZeneca, Elpis, ScholarRock, Surface, ValoHealth, Sanofi, Fathom; Ownership Interest Less Than 5%: Werewolf, Pyxis, Elpis; NPI: 1306874201. JRB—Consulting fees: Amgen, BMS, Genentech/Roche, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Sanofi, Regeneron; Contracted research: AstraZeneca, BMS, Genentech/Roche, Merck, RAPT Therapeutics, Revolution Medicines; Data and Safety Monitoring Board/Committees: GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi. SC—Consulting fees: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Ultrahuman, Oncovita; Fees for Non-CE Services: Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Janssen, Merck, MSD, Novartis and Roche; Contracted Research: Amgen, Merck, Sanofi Aventis; As part of the Drug Development Department (DITEP) at Gustave Roussy, Principal/sub-Investigator of Clinical Trials Research Grants from, Non-financial support (drug supplied) from: Principal/sub-Investigator of Clinical Trials for: Abbvie, Adaptimmune, Adlai Nortye USA, Aduro Biotech, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Argen-X Bvba, Astex Pharmaceuticals, Astra Zeneca Ab, Aveo, Basilea Pharmaceutica International, Bayer Healthcare Ag, Bbb Technologies Bv, Beigene, BicycleTx, Blueprint Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ca, Celgene Corporation, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Clovis Oncology, Cullinan-Apollo, Curevac, Daiichi Sankyo, Debiopharm, Eisai, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Faron Pharmaceuticals, Forma Tharapeutics, Gamamabs, Genentech, Glaxosmithkline, H3 Biomedicine, Hoffmann La Roche Ag, Imcheck Therapeutics, Innate Pharma, Institut De Recherche Pierre Fabre, Iris Servier, Iteos Belgium SA, Janssen Cilag, Janssen Research Foundation, Kura Oncology, Kyowa Kirin Pharm. Dev, Lilly France, Loxo Oncology, Lytix Biopharma As, Medimmune, Menarini Ricerche, Merck Sharp & Dohme Chibret, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Merus, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Molecular Partners Ag, Nanobiotix, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis Pharma, Octimet Oncology Nv, Oncoethix, Oncopeptides, Orion Pharma, Ose Pharma, Pfizer, Pharma Mar, Pierre Fabre, Medicament, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Seattle Genetics, Sotio A.S, Syros Pharmaceuticals, Taiho Pharma, Tesaro, Turning Point Therapeutics, XencorResearch Grants from Astrazeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, INCA, Janssen Cilag, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Non-financial support (drug supplied) from Astrazeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boringher Ingelheim, GSK, Medimmune, Merck, NH TherAGuiX, Pfizer, Roche. DF—Salary: Palleon Pharmaceuticals; Ownership Interest Less Than 5 Percent: Palleon Pharmaceuticals. LMK—Salary: AstraZeneca; Ownership Interest Less Than 5 Percent: AstraZeneca. JM—Consulting fees: Novartis, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Pharmacyclics, Audentes Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Deciphera, Ipsen, Boston, Biomedical, ImmunoCore, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Myovant, Amgen, Boehringer, Cytokinetics. MCP— Employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Rahway, NJ, USA, and own stock (less than 5%) in Merck & Co, Rahway, NJ, US. JR—Nothing to Disclose. CR—Consulting fees: BMS, Roche, Pierre Fabre, Novartis, Sanofi, MSD, Pfizer, AstraZeneca. ES—NPI: 1467480160. MES-A—Consulting fees: Avenue Therapeutics ChemoCentryx, Celgene (All unrelated to the topic of interest. KS—Nothing to Disclose. MT—Nothing to Disclose. JW—Royalty: Less than 2000 dollars from a TIL growth patent by Moffitt Cancer Center; IP Rights: Named on a PD-1 biomarker patent by Biodesix, and on a CTLA4 biomarker patent by Moffitt Cancer Center, and a TIL growth patent by Moffitt Cancer Center; Consulting fees: Ad Boards for: BMS, GSK, Merck, Genentech, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Celldex, Biond, Evaxion, Regeneron, Alkermes, Novartis, Incyte, Moderna, Cytomx, Ultimovacs and Sellas; NPI: 1053348706; Ownership Interest Less Than 5 Percent: Biond, Neximmune MESA: Consultant fees: Pfizer, Eli Lilly, BMS. SITC Staff—CG, AK, NL, SMW: Nothing to Disclose.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2023. Re-use permitted under CC BY-NC. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunol Rev 2008;224:166–82. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev 2010;236:219–42. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Moel EC, Rozeman EA, Kapiteijn EH, et al. Autoantibody development under treatment with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Immunol Res 2019;7:6–11. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berner F, Bomze D, Diem S, et al. Association of checkpoint inhibitor-induced toxic effects with shared cancer and tissue antigens in non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1043–7. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwek SS, Dao V, Roy R, et al. Diversity of antigen-specific responses induced in vivo with CTLA-4 blockade in prostate cancer patients. J Immunol 2012;189:3759–66. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caturegli P, Di Dalmazi G, Lombardi M, et al. Hypophysitis secondary to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 blockade: insights into pathogenesis from an autopsy series. Am J Pathol 2016;186:3225–35. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding H, Wu X, Gao W. PD-L1 is expressed by human renal tubular epithelial cells and suppresses T cell cytokine synthesis. Clin Immunol 2005;115:184–91. 10.1016/j.clim.2005.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo J, Martucci VL, Quandt Z, et al. Immunotherapy-mediated thyroid dysfunction: genetic risk and impact on outcomes with PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:5131–40. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews MC, Duong CPM, Gopalakrishnan V, et al. Gut microbiota signatures are associated with toxicity to combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade. Nat Med 2021;27:1432–41. 10.1038/s41591-021-01406-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Y, Ruddy KJ, Tsuji S, et al. Coverage evaluation of CTCAE for capturing the immune-related adverse events leveraging text mining technologies. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2019;2019:771–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie T, Zhang Z, Qi C, et al. The inconsistent and inadequate reporting of immune-related adverse events in PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Oncologist 2021;26:e2239–46. 10.1002/onco.13940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsiehchen D, Watters MK, Lu R, et al. Variation in the assessment of immune-related adverse event occurrence, grade, and timing in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1911519. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Rand Corp Santa Monica CA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahmer JR, Abu-Sbeih H, Ascierto PA, et al. Society for immunotherapy of cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e002435. 10.1136/jitc-2021-002435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allouchery M, Lombard T, Martin M, et al. Safety of immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after discontinuation for grade ≥2 immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001622. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolladille C, Ederhy S, Sassier M, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:865–71. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujisaki T, Watanabe S, Ota T, et al. The prognostic significance of the continuous administration of anti-PD-1 antibody via continuation or rechallenge after the occurrence of immune-related adverse events. Front Oncol 2021;11:704475. 10.3389/fonc.2021.704475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollack MH, Betof A, Dearden H, et al. Safety of resuming anti-PD-1 in patients with immune-related adverse events (iraes) during combined anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD1 in metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018;29:250–5. 10.1093/annonc/mdx642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delyon J, Lourenço N, Vu L-T, et al. Recurrence of immune-mediated colitis upon immune checkpoint inhibitor resumption: does time matter? J Clin Oncol 2019;37:3563–4. 10.1200/JCO.19.01891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santini FC, Rizvi H, Plodkowski AJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of re-treating with immunotherapy after immune-related adverse events in patients with NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res 2018;6:1093–9. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abu-Sbeih H, Ali FS, Naqash AR, et al. Resumption of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy after immune-mediated colitis. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2738–45. 10.1200/JCO.19.00320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngamphaiboon N, Ithimakin S, Siripoon T, et al. Patterns and outcomes of immune-related adverse events in solid tumor patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in Thailand: a multicenter analysis. BMC Cancer 2021;21:1275. 10.1186/s12885-021-09003-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonaggio A, Michot JM, Voisin AL, et al. Evaluation of readministration of immune checkpoint inhibitors after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1310–7. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luoma AM, Suo S, Williams HL, et al. Molecular pathways of colon inflammation induced by cancer immunotherapy. Cell 2020;182:655–71. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasson SC, Slevin SM, Cheung VTF, et al. Interferon-gamma-producing CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells are a targetable hallmark of immune checkpoint inhibitor-colitis. Gastroenterology 2021;161:1229–44. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L, Tsang VHM, Sasson SC, et al. Unravelling checkpoint inhibitor associated autoimmune diabetes: from bench to bedside. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:764138. 10.3389/fendo.2021.764138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstock C, Singh H, Maher VE, et al. FDA analysis of patients with baseline autoimmune diseases treated with PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy agents. JCO 2017;35:3018. 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.3018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortellini A, Buti S, Santini D, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with advanced cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases treated with anti-programmed death-1 immunotherapy: a real-world transverse study. Oncologist 2019;24:e327–37. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tison A, Quéré G, Misery L, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer and preexisting autoimmune disease: a nationwide, multicenter cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:2100–11. 10.1002/art.41068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halle BR, Betof Warner A, Zaman FY, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with pre-existing psoriasis: safety and efficacy. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:10. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdel-Wahab N, Shah M, Lopez-Olivo MA, et al. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of patients with cancer and preexisting autoimmune disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:121–30. 10.7326/M17-2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie W, Huang H, Xiao S, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors therapies in patients with cancer and preexisting autoimmune diseases: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19:102687. 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ceeraz S, Nowak EC, Burns CM, et al. Immune checkpoint receptors in regulating immune reactivity in rheumatic disease. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:469. 10.1186/s13075-014-0469-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raptopoulou AP, Bertsias G, Makrygiannakis D, et al. The programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 inhibitory pathway is up-regulated in rheumatoid synovium and regulates peripheral T cell responses in human and murine arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1870–80. 10.1002/art.27500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3167–75. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappelli LC, Brahmer JR, Forde PM, et al. Clinical presentation of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis differs by immunotherapy regimen. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;48:553–7. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owen CN, Bai X, Quah T, et al. Delayed immune-related adverse events with anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy in melanoma. Ann Oncol 2021;32:917–25. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.03.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ascierto PA, Del Vecchio M, Mandalá M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma (checkmate 238): 4-year results from a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1465–77. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30494-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naidoo J, Reuss JE, Suresh K, et al. Immune-related (IR) -pneumonitis during the COVID-19 pandemic: multidisciplinary recommendations for diagnosis and management. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000984. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2339–49. 10.1200/JCO.21.00174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Five-year outcomes with nivolumab in patients with wild-type BRAF advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3937–46. 10.1200/JCO.20.00995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1535–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, et al. Five-year outcomes from the randomized, phase III trials checkmate 017 and 057: nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:723–33. 10.1200/JCO.20.01605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gettinger S, Horn L, Jackman D, et al. Five-year follow-up of nivolumab in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from the CA209-003 study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1675–84. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.0412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1973–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa2202170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1789–801. 10.1056/NEJMoa1802357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (impower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;398:1344–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1191–203. 10.1056/NEJMoa2032125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernell S, Howard SW. Use your words carefully: what is a chronic disease? Front Public Health 2016;4:159. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patrinely JR, McGuigan B, Chandra S, et al. A multicenter characterization of hepatitis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology 2021;10:1875639. 10.1080/2162402X.2021.1875639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhatlapenumarthi V, Patwari A, Harb AJ. Immune-related adverse events and immune checkpoint inhibitor tolerance on rechallenge in patients with iraes: a single-center experience. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021;147:2789–800. 10.1007/s00432-021-03610-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang S-Q, Tang L-L, Mao Y-P, et al. The pattern of time to onset and resolution of immune-related adverse events caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: a pooled analysis of 23 clinical trials and 8,436 patients. Cancer Res Treat 2021;53:339–54. 10.4143/crt.2020.790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patrinely JR, Johnson R, Lawless AR, et al. Chronic immune-related adverse events following adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy for high-risk resected melanoma. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:744–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghisoni E, Wicky A, Bouchaab H, et al. Late-onset and long-lasting immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint-inhibitors: an overlooked aspect in immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2021;149:153–64. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo J, Beattie JA, Fuentes P, et al. Beyond steroids: immunosuppressants in steroid-refractory or resistant immune-related adverse events. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1759–64. 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdel-Wahab N, Shah M, Suarez-Almazor ME. Adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade in patients with cancer: a systematic review of case reports. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160221. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guidon AC, Burton LB, Chwalisz BK, et al. Consensus disease definitions for neurologic immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e002890. 10.1136/jitc-2021-002890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tabrizi MA, Tseng C-M, Roskos LK. Elimination mechanisms of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Drug Discov Today 2006;11:81–8. 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03638-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hurkmans DP, Basak EA, van Dijk T, et al. A prospective cohort study on the pharmacokinetics of nivolumab in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and renal cell cancer patients. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:192. 10.1186/s40425-019-0669-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Warner BM, Baer AN, Lipson EJ, et al. Sicca syndrome associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Oncologist 2019;24:1259–69. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang LS, Barroso-Sousa R, Tolaney SM, et al. Endocrine toxicity of cancer immunotherapy targeting immune checkpoints. Endocr Rev 2019;40:17–65. 10.1210/er.2018-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson DB, Nebhan CA, Moslehi JJ, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022;19:254–67. 10.1038/s41571-022-00600-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Del Rivero J, Cordes LM, Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, et al. Endocrine-related adverse events related to immune checkpoint inhibitors: proposed algorithms for management. Oncologist 2020;25:290–300. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antoury L, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Alopecia areata as an immune‐related adverse event of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. Dermatologic Therapy 2020;33. 10.1111/dth.14171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larsabal M, Marti A, Jacquemin C, et al. Vitiligo-like lesions occurring in patients receiving anti-programmed cell death-1 therapies are clinically and biologically distinct from vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:863–70. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma C, Hodi FS, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. The impact of high-dose glucocorticoids on the outcome of immune-checkpoint inhibitor-related thyroid disorders. Cancer Immunol Res 2019;7:1214–20. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Faje AT, Lawrence D, Flaherty K, et al. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with melanoma. Cancer 2018;124:3706–14. 10.1002/cncr.31629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Palaskas NL, Segura A, Lelenwa L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis: elucidating the spectrum of disease through endomyocardial biopsy. Eur J Heart Fail 2021;23:1725–35. 10.1002/ejhf.2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norwood TG, Westbrook BC, Johnson DB, et al. Smoldering myocarditis following immune checkpoint blockade. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:91. 10.1186/s40425-017-0296-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nishino K, Ohe S, Kitamura M, et al. Nivolumab induced vitiligo-like lesions in a patient with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:E481–4. 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:563–80. 10.1038/s41571-019-0218-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (dire) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:165. 10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Domnariu PA, Noel N, Hardy-Leger I, et al. Long-term impact of immunotherapy on quality of life of surviving patients: a multi-dimensional descriptive clinical study. Eur J Cancer 2021;148:211–4. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robert C, Hwu W-J, Hamid O, et al. Long-term safety of pembrolizumab monotherapy and relationship with clinical outcome: a landmark analysis in patients with advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2021;144:182–91. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA. Viral myocarditis: 1917-2020: from the influenza A to the COVID-19 pandemics. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2021;31:163–9. 10.1016/j.tcm.2020.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smatti MK, Cyprian FS, Nasrallah GK, et al. Viruses and autoimmunity: a review on the potential interaction and molecular mechanisms. Viruses 2019;11:762. 10.3390/v11080762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saikawa H, Nagashima H, Maeda T, et al. Acute cerebellar ataxia due to epstein-barr virus under administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:12. 10.1136/bcr-2019-231520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson DB, McDonnell WJ, Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, et al. A case report of clonal EBV-like memory CD4+ T cell activation in fatal checkpoint inhibitor-induced encephalitis. Nat Med 2019;25:1243–50. 10.1038/s41591-019-0523-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buyansky D, Fallaha C, Gougeon F, et al. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in a patient on anti-programmed death-ligand 1 triggered by COVID-19: a case report. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2021;8:20543581211014744. 10.1177/20543581211014745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tan MH, Iyengar R, Mizokami-Stout K, et al. Spectrum of immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced endocrinopathies in cancer patients: a scoping review of case reports. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;5:1. 10.1186/s40842-018-0073-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Agarwal K, Yousaf N, Morganstein D. Glucocorticoid use and complications following immune checkpoint inhibitor use in melanoma. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20:163–8. 10.7861/clinmed.2018-0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams KJ, Grauer DW, Henry DW, et al. Corticosteroids for the management of immune-related adverse events in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2019;25:544–50. 10.1177/1078155217744872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kadokawa Y, Takagi M, Yoshida T, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab for steroid-resistant immune-related adverse events: a retrospective study. Mol Clin Oncol 2021;14:65. 10.3892/mco.2021.2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakano K, Nishizawa M, Fukuda N, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil as a successful treatment of corticosteroid-resistant immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced hepatitis. Oxf Med Case Reports 2020;2020:omaa027. 10.1093/omcr/omaa027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stroud CR, Hegde A, Cherry C, et al. Tocilizumab for the management of immune mediated adverse events secondary to PD-1 blockade. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2019;25:551–7. 10.1177/1078155217745144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Balaji A, Hsu M, Lin CT, et al. Steroid-refractory PD- (L) 1 pneumonitis: incidence, clinical features, treatment, and outcomes. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e001731. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burla J, Bluemel S, Biedermann L, et al. Retrospective analysis of treatment and complications of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis: histological ulcerations as potential predictor for a steroid-refractory disease course. Inflamm Intest Dis 2020;5:109–16. 10.1159/000507579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mooradian MJ, Wang DY, Coromilas A, et al. Mucosal inflammation predicts response to systemic steroids in immune checkpoint inhibitor colitis. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000451. 10.1136/jitc-2019-000451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coureau M, Meert A-P, Berghmans T, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of immune -checkpoint inhibitors in patients with preexisting autoimmune disorders. Front Med 2020;7. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abu-Sbeih H, Ali FS, Wang X, et al. Early introduction of selective immunosuppressive therapy associated with favorable clinical outcomes in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:93. 10.1186/s40425-019-0577-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tsimberidou AM, Levit LA, Schilsky RL, et al. Trial reporting in immuno-oncology (trio): an American Society of clinical oncology-society for immunotherapy of cancer statement. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:108. 10.1186/s40425-018-0426-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shankar B, Zhang J, Naqash AR, et al. Multisystem immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1952–6. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kichenadasse G, Miners JO, Mangoni AA, et al. Multiorgan immune-related adverse events during treatment with atezolizumab. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18:1191–9. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Laparra A, Kfoury M, Champiat S, et al. Multiple immune-related toxicities in cancer patients treated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 immunotherapies: a new surrogate marker for clinical trials? Ann Oncol 2021;32:936–7. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]