Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD) disparities exist in the rapidly growing and extremely heterogeneous Asian American and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NH/PI) aging populations in the United States. Limited community-clinical resources supporting culturally competent and timely diagnosis exacerbate barriers to existing care services in these populations. Community-based participatory research or community-engaged research are proven community-academic research approaches that can support the development and implementation of community-focused programs to maximize community benefit. The NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health engaged our national and local community partners to gain a deeper understanding about AD/ADRD in this diverse and growing population, to develop a strategic community-engaged research agenda to understand, address, and reduce AD/ADRD disparities among Asian American and NH/PI communities. Findings from an initial scoping review identified significant research gaps. We conducted a series of key informant interviews (n=11) and a modified Delphi survey (n=14) with Asian American and NH/PI community leaders and older adult service providers followed by a facilitated group discussion of survey findings to gain consensus on key priority research areas identified in the literature and to determine culturally and contextually appropriate approaches to support AD/ADRD prevention, early identification, and treatment in Asian American and NH/PI communities. Future research and health education should focus on raising Asian American and NH/PI basic individual- and community-level awareness about AD/ADRD and leveraging existing community assets to integrate effective engagement strategies to access AD/ADRD services within the healthcare system.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, Delphi Technique, Community-Based Participatory Research, Older People, Underserved Populations

INTRODUCTION

The United States (U.S.) population is aging considerably and becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. The U.S. Census projects that the population aged 65 and older is expected to almost double in size from 49.2 million in 2016 to 94.7 million in 2060, or 15.2% to 23.4% of U.S. residents, respectively (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018a, 2018b). Among racial and ethnic minority groups, Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders (AAs and NH/PIs) are the fastest-growing with a population projected to increase between 2016 and 2060 from 19.1 million to 37.9 million, and its share of the nation’s total population climbing from 5.9% to 9.4%. In the same period, the older AA and NH/PI population will grow nearly two-fold from 4.5% to 8.8% (The Administration for Community Living, 2017). In light of the rising number of older American adults, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD) represent increasingly significant public health concerns. Cognitive impairment cases, including AD/ADRD, will surge, affecting 15.0 million U.S. adults aged 65 and older in 2060, up from 6.1 million in 2017, and challenging a healthcare system that is ill-equipped to meet their related health and social needs (Brookmeyer et al., 2018). Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately burdened by AD/ADRD, receiving delayed diagnosis or care and facing barriers in obtaining adequate treatment (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; Chin et al., 2011). Long term temporal trends also predict increased mortality among AAs and NH/PIs due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which was the sixth leading cause of AA and NH/PI deaths in 2017 (Heron, 2019).

AD/ADRD disparities are magnified by socioeconomic status, education, health services availability, and a lack of understanding by clinicians about specific cultural differences in knowledge, beliefs, symptom presentation, and perceptions of disease and care (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; Boustani et al., 2005; Chin et al., 2011; Lines & Wiener, 2014; van de Vorst et al., 2016). Furthermore, some groups, including AAs and NH/PIs, experience linguistic isolation, have difficulty accessing basic health and social services, and require outreach and services in their native language (Wilson et al., 2005). Cultural beliefs and influences may shape how patients and their families view and manage cognitive impairment and influence caregiving experiences (Knight & Sayegh, 2010; Livney et al., 2011). Strong evidence suggests that social and cultural norms and factors associated with dementia impedes early care-seeking, evaluation, and treatment (Chin et al., 2011; Herrmann et al., 2018). Reducing AD/ADRD disparities requires culturally appropriate communication and detection strategies that account for the language, cultural perspectives, and social needs of diverse communities across the U.S. population. The current scientific knowledge base is sparse in the context of AD/ADRD among AAs and NH/PIs (Ethoan et al., 2019; Shah & Kandula, 2020; Wong et al., 2019). AA and NH/PI subgroups are a broadly under-researched group, who have limited knowledge about AD/ADRD and who face substantial barriers in obtaining timely AD/ADRD diagnosis and services, related to a dearth of socially, culturally, and contextually appropriate resources tailored for these communities.

The NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH) is a National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities-funded Specialized Center of Excellence, and is the only center of its kind in the country solely dedicated to research and evaluation on Asian American health and health disparities. Our work is guided by an integrative population health equity framework (Trinh-Shevrin et al., 2015) and agenda and employs a participatory approach to health disparities research to address diverse AA and NH/PI community health needs. Specifically, CSAAH engages in collaborative partnerships and coalitions with multi-sectoral stakeholders and organizations embedded within AA and NH/PI community settings across the U.S. to inform and to frame our research efforts. Community-based participatory research is a proven community-academic research approach that help to strengthen the development, adaptation of, or implementation of tailored, community-engaged programs and dissemination of resources to maximize community benefit and which often build on existing community assets and practices.

In 2018, CSAAH established a Healthy Aging Scientific Research Track to build upon our deep breadth of scientific expertise in community-engaged health disparities research to address critical knowledge gaps of health interventions that support prevention, early identification and treatment of AD/ADRD among AA and NH/PI populations. Efforts to establish a strategic agenda for our Healthy Aging research track began with a systematic scoping review to map out the current state of knowledge of peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary published literature on AD/ADRD in AAs and NH/PIs. The process and findings of the scoping review are detailed elsewhere (Lim et al., 2021). In brief, the scoping review found that AA and NH/PI older adults are underserved and under-diagnosed and there is tremendous need for disaggregated data to understand nationally and regionally AD/ADRD prevalence, attitudes, and knowledge, particularly among certain Asian subgroups. There is also a need for development and testing of culturally appropriate interventions that leverage existing community resources to address the rising burden as the elderly AA and NH/PI population in the U.S. continues to grow.

This article aims to 1) describe our community-participatory research process to hone a strategic, community-engaged research agenda to guide our Healthy Aging research track; and 2) describe how community input gleaned from a series of key informant interviews and a consensus-building process with a nationally representative community-academic advisory group informed the development of our healthy aging research agenda and activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CSAAH implemented a multistep process to develop a strategic, community-informed healthy aging research agenda starting with the scoping review of peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary published literature on AD/ADRD in AAs and NH/PIs. Next steps included: 1) a series of key informant interviews with AA and NH/PI community stakeholders and, 2) a modified, two-round Delphi Technique to gain broad community consensus on priority AD/ADRD research topic areas. Round One of the modified Delphi Technique focused on administering a survey with community stakeholders, while Round Two included facilitating a group discussion with community and academic advisory groups (our National Advisory and Scientific Committees). Findings from the key informant interviews and the consensus-building modified Delphi Technique contribute to transferable knowledge about AD/ADRD in AA and NH/PI regional communities, under-researched populations in both broader public health and clinical studies (Doan et al., 2019). Following completion of a self-certification form, our study team deemed our research activities as not constituting research involving human subjects and therefore not required to undergo review from NYU Langone’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

1. Key Informant Interview Series

We conducted a series of key informant interviews (n=11) with AA and NH/PI older adult service providers (Table 1) to elucidate subgroup-specific beliefs and attitudes, identify existing programs and services, and needs related to AD/ADRD. Scoping review findings informed the development of interview guide questions used in this series of key informant interviews with older adult-serving AA and NH/PI community leaders from different U.S. geographic regions. Semi-structured, in-depth, one-hour interviews were conducted in-person or via phone with older adult-serving AA and NH/PI regional community experts from May - August 2019. Research staff structured interview guide questions to assess: 1) community-level barriers and facilitators to understanding and addressing healthy aging and AD/ADRD health and disparities research in AA and NH/PI populations; 2) AA and NH/PI cultural and social considerations (community knowledge, attitudes, and norms) related to healthy aging and AD/ADRD; 3) effective strategies or priorities to address and raise awareness of AD/ADRD in these communities.

Table 1:

Asian American and NH/PI community-serving organizations who participated in key informant interviews

| Key informant interviewee organization and regional community that they serve | Location |

|---|---|

| Council of Peoples Organization assists low-income immigrant families, particularly South Asians and Muslims living in New York City, through direct service efforts and community-based programs. | New York, NY |

| Indo-American Foundation Senior Group offers social, cultural and the religious activities of the Indo-American community in Phoenix, Arizona. | Phoenix, AZ |

| Asian Pacific Community in Action is a community-based organization that works to meet the health related needs of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander individuals and families residing in Arizona. | Phoenix, AZ |

| Kalusugan Coalition is a multidisciplinary collaboration dedicated to creating a unified voice to improve the health of Filipino Americans in the New York/New Jersey area. | New York, NY |

| Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York Public Health Research Center / Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York’s Adult Day Care Center* is the first community-based social service agency targeting the Korean population and works to enrich the lives of physically and mentally disabled Korean American and Korean immigrant seniors through culturally competent programs in New York City. | New York, NY |

| Lunalilo Home & Trust provides respectful, compassionate, and loving care services and programs for kūpuna (elder care) for Native Hawaiians in Hawai’i. | Honolulu, HI |

| Nā puʻuwai is a Native Hawaiian health care center serving the communities in Molokai Molokaʻi (including Kalaupapa), and Lānaʻi, that helps promote, address and improve the mauli ola of their lāhui. | Molokai, HI |

| Papa Ola Lōkahi offers social and health service programs to improve the overall health and well-being of Native Hawaiians and their families living in Hawai’i, through strategic partnerships, programs and public policy. Programs include services for older Native Hawaiians and Native Pacific Islanders in Hawai’i. | Honolulu, HI |

| Penn Asian Senior Services (PASSi) supports Philadelphia's Asian American seniors and others who are disadvantaged because of language and cultural barriers through supportive programs. | Philadelphia, PA |

| Salt Lake County Aging & Adult Services Program connects older adults and families to older adult support services and resources in the region. | Salt Lake City, UT |

Note: CSAAH interviewed two experts from separate departments within Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York.

We identified interview participants through recommendation from our National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC), a formal body of AA and NH/PI community-serving leaders that CSAAH regularly convenes and described later. NAC representatives were invited to identify two to three community-based experts who could provide insight existing services, programs, or experience in serving AA or NH/PI older adults. This sampling approach aimed to include a focused selection of expert individuals embedded within regional AA and NH/PI communities having a range of familiarity with healthy aging practices or services. Fourteen experts were contacted and invited to participate in the AD/ADRD key informant interview series; 11 individuals agreed to participate. In-person interviews were scheduled with experts located in the New York City region (3) in offices related to social service agencies. Interviews with experts residing outside this region (7) were scheduled via phone, at a time of the interviewees’ choosing. Interviews were conducted in English, the preferred language of the interviewee, by a minimum of two trained research staff or graduate-level intern, and lasted approximately 60 minutes.

Interviews were audio-recorded with permission. A preliminary codebook was developed that used the interview topic guide as an initial outline for primary codes. Audio analysis of the key informant interviews was performed by two members of the research team who followed the “constant comparison” analytic approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), and was carried out in Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2018), a software package for qualitative data analysis. Using an iterative process, secondary and tertiary codes were developed. All codes were then reviewed by project investigators. The research team then reviewed and classified codes into overarching themes. Themes describe ideas or conceptual theories that are relevant to or that characterize the research question (Castleberry & Nolen, 2018). Any discrepancies in the coding process were addressed via consensus-building discussions with the research team.

2. Modified Delphi Technique with Community and Research Stakeholders

Our study team discussed and organized the robust qualitative data gathered from the key informant interviews, noting where community input from interviews aligned or deviated with scoping review findings about pressing research priority areas. Seeking additional community insight, CSAAH engaged our National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC) and Scientific Committee (SC) in a modified, two-step consensus-building Delphi Technique to ensure community voices shaped our healthy aging health disparities research agenda. Our NAC and SC are two formal advisory bodies comprised of community leaders and scientific stakeholders (Figure 1) representing and directly serving diverse, regional AA and NH/PI populations from across the country.

Figure 1: NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH)’s U54 National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC) & Scientific Committee (SC).

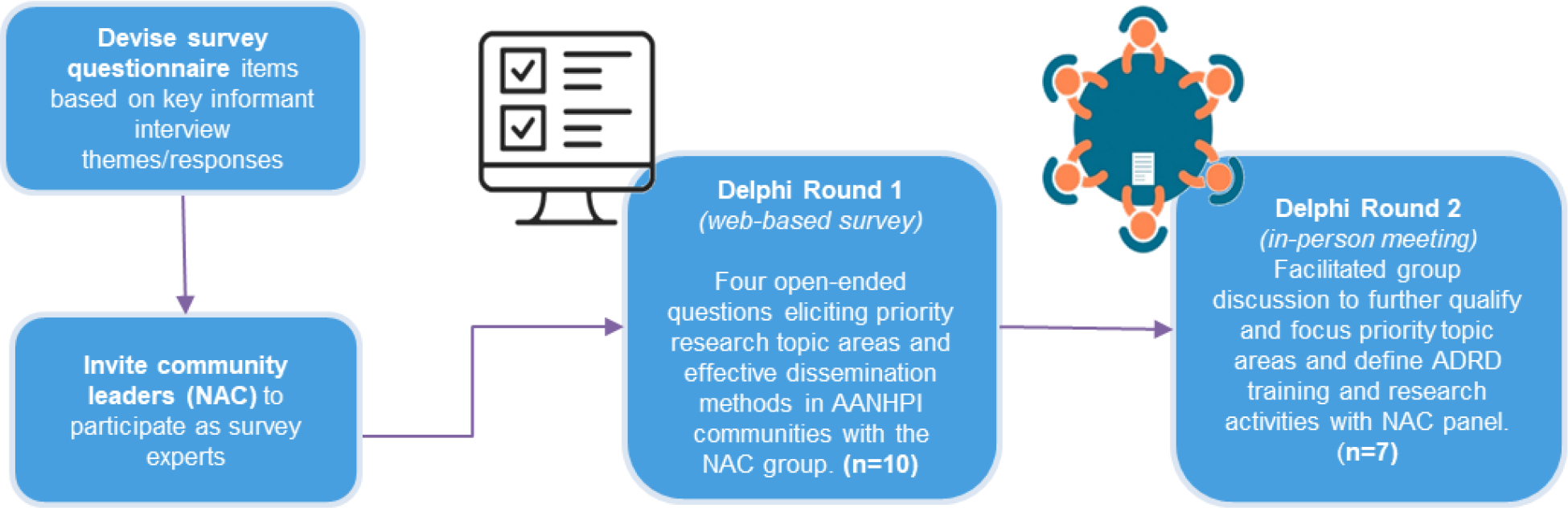

The Delphi Technique is a validated, systematic method useful for generating consensus across knowledgeable experts on a particular research question that doubles as an effective community engagement method that supports respectful and bi-directional interactions. Participants, or experts, contribute to a series of intensive questionnaires and structured group feedback sessions over several rounds; input is “pooled” to generate reliable, group-derived decisions or agreed-upon consensus positions (Benson et al., 2020; Coleman et al., 2013; Hasson et al., 2000; Rideout et al., 2013). CSAAH has successfully applied this consensus and appraisal method before with community partners and stakeholders, and have found it to be effective for exploring priorities for public health, across diverse health topic areas, and in gaining group agreement with community leaders and multi-sectoral stakeholders (Figure 2) (Grieb et al., 2017; Rideout et al., 2013).

Figure 2: Modified Delphi Technique to prioritize AD/ADRD research topics and research training needs.

We facilitated two rounds of the Delphi Technique with the NAC and SC. We began the process by first inviting NAC and SC members to rank priorities in an anonymous online survey distributed via email, as Round One of the Delphi Technique. NAC or SC participants were asked to prioritize three out of seven research focus areas for their community relevance, derived from the seven key informant interview themes. NAC and SC members were also invited to respond to open-ended questions on the online survey asking their opinions on: 1) existing AA- or NH/PI- focused resources and programs aimed at supporting healthy aging and AD/ADRD, 2) training or research tools needed to build community AD/ADRD support capacity, or 3) effective community dissemination channels or strategies that might help to support AD/ADRD health-information sharing in AA and NH/PI communities. The web-based survey was open for a four-week period, with reminder emails sent to encourage participant feedback. NAC and SC members were informed that survey feedback would be presented at an in-person meeting within two weeks following survey close, during which time, a trained study team member reviewed and refined survey results for group discussion and additional ranking, using PowerPoint slides containing minimal wording and simple images to illustrate concepts.

The Round Two, in-person convening with NAC and SC members was included as a key agenda item during a regularly scheduled in-person, open-forum group meeting with the NAC and SC. CSAAH began by presenting findings from the AD/ADRD scoping review and key themes from the key informant interviews. CSAAH and APIAHF staff then reviewed the prioritized seven research focus areas and the additional open-ended responses collected in the Round One web survey, with the group. We invited NAC and SC attendees to elaborate their reasoning for, or reactions to, the ordered research focus areas and the open-ended question responses. NAC and SC members volunteered community or organizational experiences to describe why they had prioritized certain topics, and to describe challenges to community-based AD/ADRD service provision. For example, NAC members stated a lack of, and need for, in-language or culturally tailored resources or data, describing how such materials could support tailored resource offerings to support AA or NH/PI community informational needs. Robust discussion also established ways in which healthy aging research might strengthen community-clinical strategies and supplement AA or NH/PI community organizations’ resource allocation requests from, or in partnership with local agencies, such as health departments. NAC and SC attendees were asked to re-vote, and to adjust their priority ranking of the top three of five topic areas following the group discussion on healthy aging as related to AD/ADRD, with the intent of generating group alignment on top priority and items for follow-up. CSAAH and APIAHF staff collaboratively facilitated the feedback-gathering session, asking open-ended questions to elicit full participation from all meeting attendees and to hear responses to group prioritization of research topics. Meeting notes captured details as to why development or adaptation of specific diagnostic tools or research data could be useful to bolstering AA and NH/PI communities’ existing programs or capacity to address AD/ADRD concerns.

RESULTS

1. Key Informant Interviews

Several core themes emerged from the key informant interviews CSAAH staff conducted with regional community experts about resources, needs, and attitudes in AA and NH/PI communities with regard to healthy aging, dementias and AD/ADRD. Themes included: aging at home, need for AD/ADRD education, structural barriers of the healthcare system, cultural and social norms, and value of social support and social networks.

Aging at home

Aging at home, or staying in one’s home, is a priority and preference for any older adults, as opposed to in a nursing home or long-term care facility. AA and NH/PI interview respondents generally reported on the desire for resources and interventions that allow older adults to achieve this outcome. Aging at home is intricately related to the family’s desire and sense of duty to take care of elders and elders’ desire to be with their family.

Our community would love to see kapuna [older adults] being able to age in their home… I think the thought of sending them to a retirement community or having them go to a long-term care facility is foreign, because it’s a part of our familial responsibility to care for the kapuna that raised us…The kapuna should be able to stay with us until the very end. (Native Hawaiian older adult service provider)

Interviewees also noted the toll that providing at-home care to aging relatives had on caregivers, and recommended the need for culturally sensitive home care.

Everything that I was doing became 24/7 caregiver and I learned later there’s a system someone like my mother who is nursing home bound stays home… but there wasn’t any nursing I mean any home care agency which trains Korean speaking home health aides, so I decided to create one. I started as a Korean American senior service…. and then I expand the service to other Asian communities, because there weren’t any services for any other Asian communities either…So people can stay in the community and live their life independently rather than go to a nursing home. (Korean senior service provider)

Need for AD/ADRD education

Lack of knowledge and need for expanded AD/ADRD education were common themes throughout interviews, and reflected the findings of the scoping review. Interviewees described a need for targeted engagement and education about AD/ADRD as a disease. This is likely tied to the dearth of AD/ADRD outreach and engagement efforts, such as in-language resources, to AA and NH/PI populations. Interview participants noted limited knowledge about AD/ADRD and in particular, difficulty distinguishing between signs of normal aging and pathological signs or symptoms of AD/ADRD. Informational and training interventions were mentioned as an important priority, not just for seniors, but to educate family members and the greater community.

It’s the confusion with the signs of aging versus the clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s [disease]. There is still a need to raise that awareness in the community and expand their knowledge base so they can differentiate [the two] and do the… assessment and prompt them to seek medical advice as needed. (Filipino social service care provider)

They do not know how to recognize this burden. There hasn’t been any formal education done to educate them regarding this issue…especially, the seniors, the first generation of immigrants that came here. I mean, the second generation, the third, is definitely much more educated and they usually inform their parents that this is going on. (South Asian community service provider)

A particular need for “more research in our community” (Indian American senior program founder) and for providers to be able to address informational needs of AA and NH/PI communities was also noted:

The data that we have on Alzheimer’s is so much more than we did ten years ago, that it really can really change the way we provide nursing care. And so what are the, the community can have one form one stream of education, and then the providers I think also need to be updated on what are the latest trends, and what do we see and even if there are differences between Asian, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian [experiences with] Alzheimer’s and the rest of the population, right? We’ve done that so much with chronic disease that we can fathom and understand it but what other layers do we have as Asian Americans Native Hawaiian Pacific Islanders would be helpful. (Native Hawaiian older adult service provider)

Structural Barriers of the Healthcare System

Interview respondents identified several key structural barriers to AA or NH/PI engagement with currently available AD/ADRD and older adult care services. Interviewees described the challenges related to individual- and community-level access to and navigation of older adult care services and the healthcare system. Many also described a desire for a network of easily accessible healthy aging and AD/ADRD resources for seniors and their families, to reduce the task burden of searching for culturally concordant healthcare providers or resources on their own. A need for a pipeline of care, meaning a structured pathway to encourage and enable AAs and NHs/PIs into older adult care service programs and access to AA or NH/PI adult care providers was noted as a priority need, linked to the importance of integrating people into the health system.

What I’ve heard from families is: you know it’s great that there is an office on aging, but you still have to call, you still have to be your own advocate for a lot of these pieces. And that’s hard when you’re working full time and the stacks of forms are pretty significant and if you yourself are not familiar with filling out those forms. [It means that] the likelihood of you following through for your parent or grandparent is reduced. (Native Hawaiian health service provider)

Limited outreach and engagement from existing healthcare systems to inform or connect AA and NH/PI communities to available services is a major barrier, along with a general lack of culturally competent programs/services (e.g. nursing homes). Availability of culturally competent care, was an important consideration for all communities, and the lack of such culturally-tailored services is a major barrier to addressing healthy aging or AD/ADRD concerns. Interviewees described the need for in-language services, culturally tailored meals, activities, and the ability to socially interact with others of the same culture as important priorities for older adults seeking care and their communities.

If you are not comfortable with your physician, who doesn’t speak your language, they don’t know, don’t understand your everyday diet and they don’t quite connect with your lifestyle, you know, as a patient you’re not going to share much of the very intimate details with your healthcare provider (Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander-serving social service organizational leader, formerly with an Alzheimer’s research institute).

When describing difficulty in finding services for her aging mother, one respondent noted “I could not send her to a nursing home because she didn’t eat American food especially when in such a weak… health condition, and also she cannot communicate in English… This general [regional] area has 40 senior centers. But none of them provide an Asian meal and none of them has a specific Asian oriented program” (Asian American senior center service leader).

Cultural and social norms

Cultural norms include all important aspects of culture or society that influence AD/ADRD perceptions, beliefs, health behaviors, and priorities. Family support was a sub-theme of cultural and social norms, and encompassed aspects of aging and care that involve family members, including relatives acting as primary caregivers and family involvement in educational and AD care interventions. Family support was directly tied to deep respect for elders and valuing older adults within the family unit and in the larger community. While family support is a resource that should be utilized in addressing healthy aging and AD/ADRD in AA and NH/PI communities, interview respondents also described familial duties and obligations to each other as potential stressors. While the ability to care for one’s aging relative is viewed positively, interview respondents also described stress associated with caregiving, such as elders not wanting to burden their adult children with regular care in their older age, particularly for those in multigenerational households.

Taking care of our parents ...is a financial as well as an emotional task. A lot of the times I’m reminded, you know a friend or a family… will say ‘well that must be a burden,’ and immediately, I go into a defensive zone and say that wait, it’s not a burden it’s a responsibility (Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander-serving social service organizational leader, formerly with an Alzheimer’s research institute).

That level of care, most people can’t handle it. If you’re working and you have kids, how do you also provide this care? …It’s a huge commitment… even [with] social daycare, so they can send them there during the day… Because there are all these things that make it so hard to do it, I understand why [many] people don’t follow that old like, ‘Oh, my parents will live with me when they are old (Korean American senior center service leader).

Cultural education on AD/ADRD and aging was a sub-theme of cultural and social norms. Attitudes on AD/ADRD and aging varied across AA and NH/PI communities and respondents felt that expanded education might strengthen awareness about AD/ADRD within the community.

Our community is not educated in Alzheimer’s disease at all. If you mention it to them, they will not know what it is… There hasn’t been any formal education done to educate them regarding this issue…”“My father [had] early onset dementia… it was something that I was expecting because his father had also a history of it… I think it is a common side effect for the families to not believe it… I still have family members that tell me to this day that [there is] probably nothing wrong [with him] (South Asian community organization leader).

Value of social supports and social networks

Social support was considered an important component of aging for seniors, particularly ones without family networks or living relatives for support. Social support as described by interview respondents, included older adults participating in social activities or hobbies with friends, older adult friends checking up on each other, and seniors using senior groups or centers as platforms to maintain these social and cultural support systems. Support systems and community or group programs tailored for older adults provide are important channels through which older adults share ideas and exchange information about healthy aging and AD/ADRD. Moreover, social support was viewed as a way to mitigate social isolation from peers and/or from family among older adults.

One of the main services that a social day care provides is socialization... They don’t just show up and get fed [a meal]. They have friends and they play games and they interact with each other and do activities as well….and that’s really important… That feeling of belongingness [that] makes people get up early, or go to work, or go to serve someone, their belongingness is… very important to healthy aging (Korean American senior center service leader).

[Describing the value of providing culturally competent kapuna care] By the time they come here [to the senior service center] they have probably lost a lot. They’re at a place where they’re not independent anymore and that takes a toll on their mental health as well. If we can feed them with foods that they remember and kinda bring back memories… Those are the kinds of feelings and emotions we want to bring back for them (Native Hawaiian elder care service provider).

3. Modified Delphi Technique

The Delphi Technique offered the NAC and SC space to actively share their perspectives through rich qualitative group discussion following the web survey, building on proxy trust in which “partners are trusted because someone who is trusted invited them” so as to collectively gain consensus on priority research areas (Lucero et al., 2020). Members were invited to candidly share why certain research areas were important for their communities, cultivating bidirectional trust and confidence in feedback provision. In being asked to prioritize research topic areas NAC and SC partners were encouraged to consider the interrelatedness of themes, and how recommendations might strengthen AA or NH/PI community resources to prevent and address AD/ADRD, thus honing their professional and personal knowledge of regional community resource assets or needs. NAC and SC participants were invited to name topic areas not presented, or to suggest specific trainings, tools, or skill needs. Partners described effective and preferred venues and settings, such as in-person, multi-generational workshops or activity days, to engage community members on difficult topics related to aging, death, or AD/ADRD, which also serve as places where community health dissemination strategies might be applied to help raise awareness about AD/ADRD in AA or NH/PI communities.

Two rounds of our modified Delphi Technique was sufficient to triangulate three research priority areas (Table 2) for CSAAH to initiate a series of Healthy Aging research agenda activities, including: the need for AD/ADRD education, structural barriers of the healthcare system, and the value of existing social support and social networks.

Table 2:

Priority Research Areas defined by CSAAH’s NAC and SC through modified Delphi Technique

| Research topic area prioritized by NAC & SC | CSAAH’s recommendations for research and health education derived from the modified Delphi technique with NAC and SC |

|---|---|

| Value of social support and social networks | Leverage community assets and existing strengths related to social support and social networks. NAC and SC members placed critical importance of strengthening and utilizing social supports and social networks within Asian American and NH/PI communities. Social networks are important not only for the individual (patient with AD/ADRD) but also for caregivers, family members, and the greater community. The NAC spoke of the value in sharing AD/ADRD stories to address cultural stigma about the topic and to derive strategies to support aging individuals within a local or ethnic/cultural communities. |

| Structural barriers of the healthcare system | Integrate strategies for direct community-clinical linkage and better engagement with the healthcare system. NAC and SC stressed Asian American and NH/PI communities’ need for training, culturally congruent and in-language information for audiences who are low English proficient (LEP) or who have low literacy or low health literacy, and guidance on how to find, utilize, and engage with services within the US healthcare system. |

| Need for AD/ADRD education | Develop culturally and linguistically relevant education and information about AD/ADRD to raise individual- and community-level awareness. There is a general lack of knowledge and awareness about AD/ADRD across Asian American and NH/PI communities and subgroups. There are also few in-language, culturally adapted resources detailing healthy aging for these populations. NAC and SC agreed that education about AD/ADRD as a health topic, as well as AD/ADRD prevention, resources and care strategies, and social support options are needed. |

DISCUSSION

A community-engaged and community-participatory research approach strengthened the development of our Healthy Aging research agenda. Critical insight from key informant interviews and use of a modified Delphi Technique with our NAC and SC reiterated and aligned our understanding as to collective or subgroup-specific values related to aging and priority gaps in foundational knowledge on AD/ADRD concepts. Presentation of scoping review and key informant interview findings helped stimulate robust conversation with NAC and SC during the open forum, in-person gathering. For example, NAC and SC members described the need for tailored, focused trainings to equip direct-service staff and higher-level personnel at community-based organizations (CBOs) to support healthy aging across community venues or points during the life course. Preparing CBO staff to discuss end-of-life care services with community caregivers or clients might facilitate community familiarity with culturally and linguistically appropriate resources and programs; in-person, short-duration programs were preferred as the most effective and accessible training modalities for NAC and SC member organizational staff. Similarly, NAC feedback strongly underscored the desire for evidence-based, culturally adapted trainings tailored to support federally-funded/supported community health center clinicians or medical office staff when speaking to older family members or relatives about healthy aging processes and expectations, or offering basic term definitions, describing symptoms, as well as available AD/ADRD preventative care services or treatments. Suggestions reinforce the critical importance of engaging existing community assets and existing social and community networks to raise AA and NH/PI individual- and community-level awareness and knowledge about healthy aging topics. Community-based NAC members also voiced the need for tailored, culturally-engaged information-sharing approaches and resources that leverage existing community centers and information sources to enable conversations with community members and their families about healthy aging.

CSAAH has launched several community-engaged, and community-informed research initiatives, detailed in Table 3, building from our formative research findings. In response to the described need for greater AD/ADRD education, to care providers and community members, CSAAH will culturally- and linguistically- adapt a training guide to support primary care providers’ diagnoses of cognitive impairment and early dementia among older Asian American adult populations in community settings. We are also engaged in a collaborative effort to increase lay knowledge on signs of cognitive difficulties and draft practical strategies for healthcare professionals and community members to engage in meaningful conversations about cognition. A new wave of our Community Health Resources and Needs Assessment (CHRNA) survey effort is underway, which applies a community-engaged and community venue‒based surveying approach to understand existing assets or community priorities related to access to aging care services, existing or desired community-based programs, and other factors. The Older Adult CHRNA will assess the aging needs of diverse, limited English older adult community populations to better understand social support and social networks within AA communities.

Table 3.

Future CSAAH Research Activities Related to AD/ADRD

| Project* | Description | Priority Research Area(s) | Community Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kickstart-Assess-Evaluate-Refer (KAER) Toolkit | CSAAH has initiated a project to culturally adapt and translate the comprehensive KAER toolkit for primary care providers to support detection of cognitive impairment and early diagnosis of dementia for older Asian American adult communities, to be administered in primary care and community settings. The KAER framework comes from the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) and identifies four steps to increase cognitive awareness, detection of cognitive impairment, diagnosis and post-diagnostic referrals, and medical care. | Structural barriers of the healthcare system; Need for AD/ADRD education | Chinese-American Planning Council, India Home, Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York |

| Older Adult Community Health Resources and Needs Assessment (CHRNA) | CSAAH’s large-scale health needs assessment project focused on diverse older adults will use a community-engaged and community venue-based approach to assess existing health issues, available resources, and best approaches to meet needs of aging communities. | Structural barriers of the healthcare system | Network of community partners |

| NYU BOLD Public Health Center of Excellence (PHCOE) for Early Detection of Dementia | The NYU BOLD PHCOE is a national repository and catalyst for implementation of evidence-based and evidence-informed public health strategies that increase early dementia detection. | Structural barriers of the healthcare system; Need for AD/ADRD education | National advisory council of community partners, advocacy groups, healthcare systems, and professional societies |

| Academic Leadership Award on Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Disparities Research | This initiative aims to establish a research training program to build academic capacity and leadership to advance the science of aging and AD/ADRD health disparities, advance innovative participatory, systems science, and implementation science frameworks and methods for aging and AD/ADRD research in minority and health disparity populations, and mentor junior scientists in applying multi-level, community-engaged frameworks and rigorous methods to advance the science of aging and AD/ADRD health disparities research. | Research to advance the AD/ADRD field | N/A |

| Engagement in Longevity and Medicine (ELM) Research Collaborative | ELM is evaluating and disseminating best practices in engaging, recruiting and retaining diverse older populations in research. This project aims to stimulate the development and testing of innovative, community-engaged approaches to participant recruitment in clinical and community settings, and strengthen communication and messaging strategies tailored to diverse aging research populations. | Research to advance the AD/ADRD field | Hamilton-Madison House, Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York |

| Preparing Successful Aging through Dementia Literacy Education and Navigation (PLAN) | This clinical trials test the effect of a community-based intervention, PLAN, delivered by trained CHWs for undiagnosed Korean American older adults with probable dementia and their caregivers on linkage to medical services for dementia. The aim is to test the effect of PLAN on Korean older adults with probable dementia and caregivers towards development of a plan regarding dementia care compared to usual care. | Value of social support and social networks; Structural barriers of the healthcare system; Need for AD/ADRD education | Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York, Korean Community Service Center of Greater Washington |

| Asian Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research (RCMAR) | The Asian RCMAR advances careers of investigators from underrepresented populations through translational trauma and resilience research amongst Asian American older adults that informs both practice and policy at community, city, state, regional, and national levels. | Research to advance the AD/ADRD field | N/A |

CSAAH is currently assessing a community health worker-delivered education and navigation support program to support older Korean Americans with probable dementia and their caregivers and promote linkage to care is ongoing, to address structural barriers to care within the healthcare system. We are also working to bolster development of a robust pipeline of researchers to advance the field of healthy aging to improve AA older adult health, in acknowledgment of the need to expand AD/ADRD focused research (Table 3).

Our approach to obtaining and collaboratively prioritizing community-generated research topics or need areas to set our research agenda has precedent; the Muslim Americans Reaching for Health and Building Alliances (MARHABA) Initiative was a culturally tailored breast and cervical cancer intervention led by lay health workers to promote cancer awareness and screening in diverse New York City Muslim populations. The CSAAH team utilized key-informant and in-depth interviews with community members to culturally adapt small media educational materials on breast and cervical cancer screening for Muslim American women (Wyatt et al., 2022), which strengthened acceptability and uptake of cancer screening in this population through the MARHABA program. Relatedly, CSAAH used the Delphi Technique to identify research priorities to prepare a culturally tailored H. pylori treatment, adherence, and stomach cancer prevention curriculum to support immigrant Chinese population (Kwon et al., 2019), and to gain consensus among a community advisory board and steering committee when determining best practices to improve clinical and translational research practice (Rideout et al., 2013).

Our work provides a first step to understanding attitudes about and needs related to AD/ADRD in AA and NH/PI communities. We acknowledge that the perspectives highlighted are limited to the experiences and viewpoints of our NAC and SC members and interviewees, thereby limiting the generalizability of our findings to other communities and regions (Table 4). We engaged a diverse group of stakeholders representing different geographies in our approach; however, findings do not reflect the many cultural or regional nuances across AA and NH/PI populations. Additionally, the Delphi Technique is a time consuming process with multiple rounds of consensus-building, making it challenging to ensure participants are actively engaged or available across all rounds of the process due to participants’ schedules. Familiarity with our NAC/SC may have encouraged the rich qualitative response rate during the Delphi technique. While findings from both the Delphi and the key informant interviews aligned with each other and those from the earlier scoping review, future studies are needed to recognize and amplify community-based resources and efforts to address the healthy aging needs of diverse AA and NH/PI communities. Ultimately, the goal of this formative work was to establish a strategic research agenda to be broadly responsive to NAC and SC healthy aging and AD/ADRD-related research to support their immediate needs for AA and NH/PI older adult community health.

Table 4.

National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC) and Scientific Committee (SC) Member 2019

| CSAAH’s National Advisory Committee on Research (2019) | |

| Community organization, regional Asian American and/or NH/PI community served | Location |

| Apicha Community Health Center provides community health care for underserved or 'otherized' people living in the New York City boroughs and on the lower east side of Manhattan, New York. | New York, NY |

| Asian Pacific Community in Action supports Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander individuals and families residing in Arizona. | Phoenix, AZ |

| The Center for Pan Asian Community Services delivers comprehensive health and social services to immigrants, refugees, and the underprivileged in Atlanta, Georgia. | Atlanta, GA |

| Chinese American Medical Society is a professional Chinese American medical society comprised of leading physicians in the New York metropolitan area. | New York, NY |

| The Asian American Health Coalition (AAHC) HOPE Clinic offers healthcare service in the Greater Houston Area to all, in over 30 languages. | Houston, TX |

| India Home is dedicated to addressing the needs of the Indian and larger South Asian senior citizen immigrant community in New York City. | New York, NY |

| Kalusugan Coalition is a multidisciplinary collaboration dedicated to improving Filipino American community health in the New York/New Jersey area. | New York, NY |

| Papa Ola Lōkahi offers social and health service programs and advocacy to strengthen and improve the health status of Native Hawaiians living in Hawai’i, as well as Native Pacific Islanders. | Honolulu, HI |

| Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York provides social, health, and economic services and support to Korean immigrants and to the wider Asian community in New York City. | New York, NY |

| The National Tongan American Society empowers the Tongan and Pacific Islander community of Salt Lake City, Utah through health, education, cultural, and social services. | Salt Lake City, UT |

| Orange County Asian Pacific Islander Community Alliance enhances the health, and social and economic well-being of Asian and Pacific Islanders in Orange County, California. | Garden Grove, CA |

| UNITED SIKHS offers social service, development, and advocacy support to the Sikh community in NYC. | New York, NY |

| CSAAH’s Scientific Committee (2019) | |

| Member, Organization or Institution | |

|

Nia Aitaoto, PhD, MS, MPH, Research Associate Professor Nutrition, and Integrative Physiology University of Utah, Utah Center for Pacific Islander Health (UCPIH) | |

|

Scarlett Lin‐Gomez, PhD, MPH, Professor Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics University of California, San Francisco | |

|

Daphne Kwok, Vice President of Diversity Equity & Inclusion, Asian American & Pacific Islander Audience Strategy AARP | |

|

Ho Luong Tran, MD, MPH, (former) President and CEO National Council of Asian & Pacific Islander Physicians | |

|

Tina J. Kauh, PhD, Senior Program Officer, Research-Evaluation-Learning Unit Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | |

|

Dorothy Castille, PhD, Project Officer for the U54 grant Division of Scientific Programs, Community Health, and Population Sciences, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities | |

CONCLUSION

This is the first instance of a broad assessment of community resources and priority-setting for AD/ADRD and the AA and NH/PI communities informed by a multistep process including a thorough review of literature (scoping review), a series of qualitative key informant interviews, and a modified Delphi technique for consensus building. Integrating community voices at the onset of research agenda setting processes is a critical consideration and approach to conducting community-engaged research that supports respectful and bi-directional interaction. Findings highlight the need for future research and health education to focus on raising individual- and community-level awareness about AD/ADRD and leveraging existing community assets to facilitate engagement with the healthcare system, including the development of culturally and linguistically adapted educational resources for AA and NH/PI communities.

What is known about this topic:

The growing aging population in the United States (U.S.) has made Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD) a significant public health concern.

The current landscape of research literature is sparse in the context of AD/ADRD needs or priorities among Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders (NH/PIs).

Community-engaged research efforts identified knowledge and healthcare system barriers as priority areas to support AD/ADRD research in under-reached communities.

What this paper adds

Leveraging existing community assets may help to facilitate and support the rapidly growing aging Asian American and NH/PI populations’ capacity to engage with the healthcare system.

Development of culturally and linguistically adapted educational resources tailored to raise individual- and community-level awareness about AD/ADRD across Asian American and NH/PI communities is a top priority.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors thank our U54 National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC) – Apicha Community Health Center, Asian Pacific Community in Action (APCA), Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS), Chinese American Medical Society (CAMS), Council Of Peoples Organization (COPO), HOPE Clinic, India Home, Kalusugan Coalition, Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York (KCS), National Tongan American Society (NTAS), Orange County Asian Pacific Islander Community Alliance (OCAPICA), Papa Ola Lōkahi, South Asian Council for Social Services (SACSS), and UNITED SIKHS – for their contribution to this research effort to understand healthy aging and ADRD in their communities, and for their continued partnership and support of our community engagement and health disparities research at the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH).

The authors are deeply grateful to the community stakeholders and leaders who volunteered their time to be interviewed for this effort from: COPO, Indo-American Foundation Senior Group, Iqvia, Kalusugan Coalition, KCS, Lunalilo Home & Trust, nā pu‘uwai, Papa Ola Lokahi, Penn Asian Senior Services (PASSi), and Salt Lake County Aging & Adult Services.

The authors also wish to show appreciation to our U54 Scientific Committee (SC) for their insight and support of this research effort. Thank you, Nia Aitaoto, PhD, MS, Scarlett Lin-Gomez, PhD, MPH, Daphne Kwok, Ho Luong Tran, MD, MPH, Tina J. Kauh, PhD, and Dorothy Castille, PhD, for your continued collaboration and guidance towards building Asian American and NH/PI community capacity and health equity.

Funding:

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Award Number U54MD000538, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Award Numbers R24AG063725 and K07AG068186, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention & Health Promotion Award NU58DP006911. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval: Data collection and analysis for this study involved aggregated, coded information that contained no identifiers. No identities of the involved individuals to whom the data belonged to were accessible to the study team during analyses. The study team completed and the Principal Investigator approved a Self-Certification Form confirming that key informant interview research conducted was not human subjects’ research and IRB review was not required. The study team conducted a modified Delphi technique with a trusted, community advisory board (NAC) with whom our research team regularly engages.

Data Availability:

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author (JAW).

REFERENCES

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2017). Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer Dement, 13, 325–373. [Google Scholar]

- Benson H, Lucas C, & Williams KA (2020). Establishing consensus for general practice pharmacist education: A Delphi study. Curr Pharm Teach Learn, 12(1), 8–13. 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Perkins AJ, Fultz BA, Hui SL, & Hendrie HC (2005). Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med, 20(7), 572–577. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0126.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N, Kawas CH, & Corrada MM (2018). Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement, 14(2), 121–129. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleberry A, & Nolen A (2018). Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr Pharm Teach Learn, 10(6), 807–815. 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin AL, Negash S, & Hamilton R (2011). Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 25(3), 187–195. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CA, Hudson S, & Maine LL (2013). Health literacy practices and educational competencies for health professionals: a consensus study. J Health Commun, 18 Suppl 1, 82–102. 10.1080/10810730.2013.829538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan LN, Takata Y, Sakuma KK, & Irvin VL (2019). Trends in Clinical Research Including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Participants Funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open, 2(7), e197432. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Grieb SD, Pichon L, Kwon S, Yeary KK, & Tandon D (2017). After 10 Years: A Vision Forward for Progress in Community Health Partnerships. Prog Community Health Partnersh, 11(1), 13–22. 10.1353/cpr.2017.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson F, Keeney S, & McKenna H (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs, 32(4), 1008–1015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11095242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M (2019). Deaths: Leading Causes for 2017 (National Vital Statistics Reports, Issue. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, Lerner AJ, Udelson N, Kanetsky C, & Sajatovic M (2018). A Systematic Review of Dementia-related Stigma Research: Can We Move the Stigma Dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 26(3), 316–331. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, & Sayegh P (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: the updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 65B(1), 5–13. 10.1093/geronb/gbp096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SC, Kranick JA, Bougrab N, Pan J, Williams R, Perez-Perez GI, & Trinh-Shevrin C (2019). Development and Assessment of a Helicobacter pylori Medication Adherence and Stomach Cancer Prevention Curriculum for a Chinese American Immigrant Population. J Cancer Educ, 34(3), 519–525. 10.1007/s13187-018-1333-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Chong S, Min D, Mohaimin S, Roberts T, Trinh-Shevrin C, & Kwon SC (2021). Alzheimer’s Disease Screening Tools for Asian Americans: A Scoping Review. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(10), 1389–1398. https://doi.org/Artn0733464820967594 10.1177/0733464820967594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines LM, & Wiener JM (2014). Racial and Ethnic Disaprities in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Literature Review.

- Livney MG, Clark CM, Karlawish JH, Cartmell S, Negron M, Nunez J, Xie SX, Entenza-Cabrera F, Vega IE, & Arnold SE (2011). Ethnoracial differences in the clinical characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease at initial presentation at an urban Alzheimer’s disease center. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 19(5), 430–439. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181f7d881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero JE, Boursaw B, Eder MM, Greene-Moton E, Wallerstein N, & Oetzel JG (2020). Engage for Equity: The Role of Trust and Synergy in Community-Based Participatory Research. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 372–379. 10.1177/1090198120918838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout C, Gil R, Browne R, Calhoon C, Rey M, Gourevitch M, & Trinh-Shevrin C (2013). Using the Delphi and snow card techniques to build consensus among diverse community and academic stakeholders. Prog Community Health Partnersh, 7(3), 331–339. 10.1353/cpr.2013.0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NS, & Kandula NR (2020). Addressing Asian American Misrepresentation and Underrepresentation in Research. Ethn Dis, 30(3), 513–516. 10.18865/ed.30.3.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants L (2018). Dedoose Version 8.3.35, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data In www.dedoose.com

- The Administration for Community Living. (2017). Profile of Asian Americans Age 65 and Over: 2017. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2017OAProfileAsAm508.pdf

- Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS, Nadkarni S, Park R, & Kwon SC (2015). Defining an integrative approach for health promotion and disease prevention: a population health equity framework. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 26(2 Suppl), 146–163. 10.1353/hpu.2015.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018a). 2017 National Population Projections Tables. Retrieved 5/17/2018 from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018b). An Aging Nation. Retrieved 5/17/2018 from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2018/comm/historic-first.html

- van de Vorst IE, Koek HL, Stein CE, Bots ML, & Vaartjes I (2016). Socioeconomic Disparities and Mortality After a Diagnosis of Dementia: Results From a Nationwide Registry Linkage Study. Am J Epidemiol, 184(3), 219–226. 10.1093/aje/kwv319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, & Fernandez A (2005). Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med, 20(9), 800–806. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R, Amano T, Lin SY, Zhou Y, & Morrow-Howell N (2019). Strategies for the Recruitment and Retention of Racial/Ethnic Minorities in Alzheimer Disease and Dementia Clinical Research. Curr Alzheimer Res, 16(5), 458–471. 10.2174/1567205016666190321161901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt LC, Chebli P, Patel S, Alam G, Naeem A, Maxwell AE, Raveis VH, Ravenell J, Kwon SC, & Islam NS (2022). A Culturally Adapted Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Intervention Among Muslim Women in New York City: Results from the MARHABA Trial. J Cancer Educ. 10.1007/s13187-022-02177-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author (JAW).