Abstract

Photosynthesis must maintain stability and robustness throughout fluctuating natural environments. In cyanobacteria, dark-to-light transition leads to drastic metabolic changes from dark respiratory metabolism to CO2 fixation through the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle using energy and redox equivalents provided by photosynthetic electron transfer. Previous studies have shown that catabolic metabolism supports the smooth transition into CBB cycle metabolism. However, metabolic mechanisms for robust initiation of photosynthesis are poorly understood due to lack of dynamic metabolic characterizations of dark-to-light transitions. Here, we show rapid dynamic changes (on a time scale of seconds) in absolute metabolite concentrations and 13C tracer incorporation after strong or weak light irradiation in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Integration of this data enabled estimation of time-resolved nonstationary metabolic flux underlying CBB cycle activation. This dynamic metabolic analysis indicated that downstream glycolytic intermediates, including phosphoglycerate and phosphoenolpyruvate, accumulate under dark conditions as major substrates for initial CO2 fixation. Compared with wild-type Synechocystis, significant decreases in the initial oxygen evolution rate were observed in 12 h dark preincubated mutants deficient in glycogen degradation or oxidative pentose phosphate pathways. Accordingly, the degree of decrease in the initial oxygen evolution rate was proportional to the accumulated pool size of glycolytic intermediates. These observations indicate that the accumulation of glycolytic intermediates is essential for efficient metabolism switching under fluctuating light environments.

Quantitative metabolome dynamics reveal that a high accumulation of glycolytic intermediates in darkness enables smooth initiation of photosynthesis in cyanobacteria.

Introduction

Photosynthetic organisms have evolved various mechanisms to maintain robust photosynthesis processes throughout natural environmental perturbations. Ancestral oxygenic and phototrophic cyanobacteria contribute to global carbon cycles by photosynthetic CO2 fixation through the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle (Flombaum et al., 2013; Hutchins and Fu, 2017; Sánchez-Baracaldo et al., 2022). The driving forces of the CBB cycle are ATP and NADPH produced by light energy conversion in photosynthetic electron transfer (PET) reactions; and cyanobacteria have evolved metabolic control mechanisms to coordinate CBB cycle activity with environmental light–dark conditions. One mechanism is enzymatic activity regulation that responds to light-dependent cellular environmental changes. For example, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and phosphoribulokinase (PRK) are regulated by ternary complex formation with the regulatory protein CP12, depending on redox states of specific cysteine residues and cellular NAD(H)/NADP(H) ratio (Tamoi et al., 2005; McFarlane et al., 2019; Gurrieri et al., 2021).

Maintaining optimal metabolite concentrations is another important mechanism of CBB cycle regulation. In general, concentration robustness is necessary for the maintenance of cellular functionality (Eloundou-Mbebi et al., 2016). Recent analyses performed using a theoretical photosynthetic model have predicted that maintaining the appropriate concentrations of CBB cycle intermediates is crucial for the initiation of CO2 fixation (Matuszyńska et al., 2019). Experimental evidence in cyanobacteria has confirmed that the transfer of the carbon supply from a storage polymer (glycogen) to the CBB cycle affects photosynthetic efficiency (Shimakawa et al., 2014; Shinde et al., 2020). In addition, while enzymatic regulation systems control metabolism, metabolite concentration affects metabolism itself by thermodynamic constraints and effects on enzymatic kinetics as represented by the Michaelis-Menten equation (Bennett et al., 2009; Park et al., 2016). Thus proper regulation of metabolite distribution is considered to be important for activation of the CBB cycle.

However, the metabolite distribution underlying robust CBB cycle operation under light–dark perturbations is still unclear. Ascertaining which metabolite is important for the CBB cycle initiation requires understanding metabolic dynamics during CBB cycle activation immediately after a dark-to-light transition. For this, we aim to derive dynamic metabolic flux changes during photosynthetic activation. Although metabolic flux analysis (MFA) using an isotope tracer enables the mapping of intracellular carbon fluxes (Sauer, 2006; Young et al., 2011; Shimizu and Toya, 2021), the approach cannot be applied to a metabolically nonstationary state with variable metabolic fluxes and pool sizes. On the other hand, previously developed dynamic MFA, which incorporates specialized statistical approaches, has permitted the estimation of long-term flux changes over the culture interval (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2011; Niklas et al., 2011). There has been (to our knowledge) no appropriate approach for the quantitative determination of metabolic flux changes throughout short, metabolically transient states, including that of CBB cycle activation.

In this study, we successfully quantify absolute metabolite concentration changes at second-scale intervals after dark-to-light transitions in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis). Additionally, to identify metabolic pathways that are activated during CBB cycle initiation, dynamic 13C labeling is performed immediately following light irradiation. Accurate concentration and labeling dynamics allow us to conduct short-time dynamic MFA (STD-MFA) to estimate nonstationary flux changes during activation of the CBB cycle. The STD-MFA results show that highly accumulated glycolytic intermediates including 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG), 2-phosphoglycerate (2PG), and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) are main substrates for initial CO2 fixation. This metabolic phenomenon is further characterized by the decreases in oxygen evolution rate at the beginning of light irradiation in several mutant strains, in which the accumulated pool sizes of the glycolytic intermediates are found to be smaller than that of wild-type cells.

Results

Strategy for estimating metabolic flux dynamics

To estimate nonstationary metabolic flux changes, the following relationship is employed. The accumulation rate of a metabolite in a metabolic network is defined as the sum of all fluxes producing the metabolite minus the sum of all fluxes consuming the metabolite, as represented by the following equation:

| (1) |

where xj(t) is the flux through reaction j, αj is a stoichiometric coefficient, and ri(t) is the accumulation rate of metabolite i (Vallino and Stephanopoulos, 1993). An example with three metabolic fluxes is illustrated in Figure 1A. To obtain accumulation rates for estimation of the flux values, it is necessary to examine the absolute concentration changes of metabolites with high time resolution. Namely, the metabolic flux during CBB cycle activation can be calculated by quantifying the changes in metabolite concentrations over highly time-resolved intervals immediately following light irradiation.

Figure 1.

Process for estimating temporal changes in metabolic flux. A, Relationship between concentration change and metabolic flux. ri(t) is the accumulation rate of metabolite Mi. xn represents the metabolic flux of the nth reaction. B, Experimental procedure for quantifying absolute metabolite concentration. C, Schematic example of isotope-labeled state during 13CO2 incorporation. Empty and red-filled circles represent unlabeled and labeled carbon atoms, respectively. Abbreviations: CBB, Calvin–Benson–Bassham; CE-MS, capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; IS, internal standard; MFA, metabolic flux analysis; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; 2OG, 2-oxoglutarate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate.

Absolute concentration changes in central carbon metabolism

We sought to determine the absolute concentration dynamics of central energy metabolites in Synechocystis. As light irradiation rapidly causes metabolic variations driven by increases in ATP and NADPH via the PET reaction, rapid sampling and quenching of cellular metabolic activity are necessary to accurately quantify metabolic changes during CBB cycle activation. A standardized procedure for intracellular metabolome quantification requires multiple analytical steps, including quenching of microbial metabolic activity, separation of microbial cells from growth medium, extraction of intracellular metabolites, and finally mass spectrometric metabolite analysis. These multistep processes largely impede accurate estimation of the absolute “in vivo” cellular metabolic state (Annesley 2003; Rabinowitz and Kimball, 2007; Pinu et al., 2017).

To overcome the above problems of the present study, a combination of two strategies was employed: rapid sampling using a phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (PCI) extraction and absolute quantification using 13C-labeled internal standards (IS). A 13C-labeled IS mixture is prepared by extracting metabolites from Synechocystis cells cultivated with NaH13CO3 as the sole carbon source and dispensed into 12 aliquots. One aliquot is used for determination of 13C-labeled metabolite concentrations by capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS) based on the peak area ratios of unlabeled metabolites (with known concentration) and uniformly 13C-labeled metabolites (Figure 1B, left). Then, to quantify absolute concentration changes during CBB cycle activation, dark-adapted Synechocystis cells (grown in darkness for 12 h) are illuminated at a light intensity of 30 μmol m−2 s−1 (same as the growth light intensity) or 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (Figure 1B, right). Metabolites of these cells are rapidly extracted using PCI solvent containing the other aliquots of 13C-labeled extract as labeled IS. Because of high physicochemical similarities between labeled and unlabeled central metabolites, both isotopomers undergo similar processes of degradation and ion suppression, and therefore accurate concentrations can be calculated (Wu et al., 2005; Bennett et al., 2009; Dempo et al., 2014; Nishino et al., 2015).

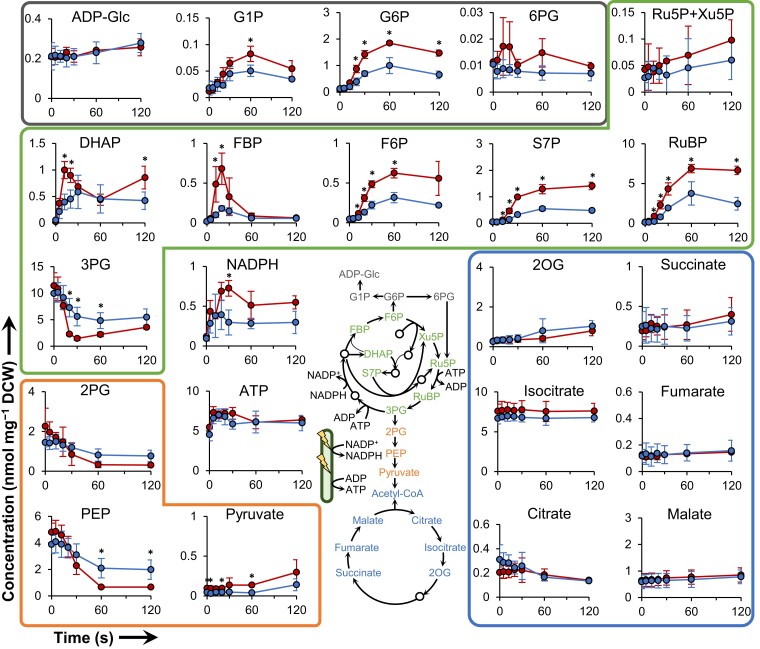

Given that absolute metabolite concentrations are determined based on the ratio between unlabeled and uniformly labeled peak areas (Figure 1B), the process is expected to prevent contamination of unlabeled metabolites in the 13C-labeled IS. The proportions of uniformly 13C-labeled metabolites (compared to the sum of unlabeled and uniformly labeled metabolites) are found to exceed 95% for all metabolites except for citrate (Supplemental Figure 1). Figure 2 shows temporal changes in absolute metabolite concentrations after the initiation of light irradiation at 30 μmol m−2 s−1 or 200 μmol m−2 s−1. It should be noted that a small amount of some metabolites are extracellular (Supplemental Figure 2). A previous study that measured in vivo NADPH fluorescence revealed that the amount of NADPH in Synechocystis increases within 0.5 s of illumination (Kauny and Sétif, 2014). The rapid increase of NADPH observed within 5 s in the present work is consistent with that of the earlier in vivo study (Kauny and Sétif, 2014), confirming that the current metabolomics strategy can successfully detect the rapid start of photosynthesis. As with NADPH, the level of the energy cofactor ATP also increases rapidly. Overall, the levels of 3PG, 2PG, and PEP decrease; the levels of other CBB cycle intermediates (except 3PG, ribulose 5-phosphate (Ru5P) and xylulose 5-phosphate (Xu5P)) increase, while the levels of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates do not change appreciably. Considering these metabolite variations together, we inferred that accumulated glycolysis intermediates including 3PG, 2PG, and PEP likely were converted to CBB cycle intermediates at the start of photosynthesis.

Figure 2.

Rapid temporal changes in absolute metabolite concentrations during the initiation of photosynthesis. Intracellular metabolites are extracted at the indicated times after transition from darkness to light-irradiated condition at light intensities of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (red line) or 30 μmol m−2 s−1 (blue line). Levels of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP), erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P), and ribose 5-phosphate (R5P) are below the detection limit (0.001 nmol/mg DCW). 1,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (BPG) and sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate (SBP) are not identified due to lack of commercial reagent for use as a standard. Metabolites are grouped by different-colored font according to the central schematic metabolic network (gray: glycogen synthesis and oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, green: Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle, orange: glycolysis, blue: tricarboxylic acid cycle). DCW, dry cell weight; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; G1P, glucose 1-phosphate; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; 2OG, 2-oxoglutarate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; 6PG, 6-phosphogluconate; 2PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; Ru5P, ribulose 5-phosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate; Xu5P, Xylulose 5-phosphate. Values are the mean ± SD (bars) of three independent experiments. Significant differences between the two light intensities were evaluated by a two-tailed non-paired Student's t test (* P < 0.05).

13C Labeling kinetics

A direct way to confirm this hypothesis is to determine the metabolic flux distribution. However, precise metabolic flux values cannot be determined when the number of unknown flux parameters (x(t) in Eq. (1)) is larger than the number of known metabolite concentration changes in the metabolic flux model. To accurately perform STD-MFA, we sought to refine our metabolic models by excluding metabolic pathways that are inactive during photosynthetic activation. The metabolite concentration data shown in Figure 2 cannot identify inactive metabolic pathways. Even if the metabolic concentration change is zero, metabolic flux is not necessarily zero, because such an observation instead may indicate that metabolic inflow and outflow are balanced. In the case where the concentration of a metabolite is stable and 13C is not incorporated into the metabolite during photosynthetic 13CO2 fixation, the metabolic fluxes around the metabolite are estimated to be very small, and therefore can be neglected. Accordingly, we next measured the dynamic 13C isotope incorporation after the transition from dark-to-light conditions, by starting photosynthesis while the cells are suspended in a solution of NaH13CO3 (Figure 1C). As a result, a transient increase in 13C fractions of CBB cycle intermediates is observed (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 3). On the other hand, labeling of 6-phosphogluconate (6PG) and TCA cycle intermediates (except for malate and fumarate) is not observed. In addition, a low 13C fraction of the glycogen precursor ADP-glucose28, is observed. When considered together with the stable concentrations of TCA and oxidative pentose phosphate (OPP) pathway intermediates (Figure 2), these results suggest extremely low metabolic fluxes of the TCA cycle, OPP pathway, Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway, and glycogen synthesis pathway, immediately after light irradiation.

Figure 3.

Incorporation of 13C atoms during Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle activation. A, Time course of 13C fraction of metabolites following light irradiation at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (red line) or 30 μmol m−2 s−1 (blue line). Values are the mean ± SD (bars) of three biological replicates. B, Total absolute amount of 13C-labeled carbon atoms. The number of incorporated 13C atoms is derived from absolute concentration and 13C fraction data. Black, green, and orange lines indicate total amount of 13C atoms of all measured metabolites, CBB cycle and oxidative pentose phosphate (OPP) pathway metabolites (G6P, 6PG, and metabolites in green font in Figure 2), and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and lower glycolysis metabolites (metabolites in orange and blue fonts in Figure 2). Left panel: 200 μmol m−2 s−1, right panel: 30 μmol m−2 s−1. C, Effect of pre-illumination on the start of 13C incorporation. 13C fractions of 3-phosphoglycerate (left panel) and ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (right panel) after 12 s of illumination (200 μmol m−2 s−1) of the 12-h dark-adapted cells were lower than those at 10 s after addition of 1 mM NaH13CO3 to cells that had been pre-illuminated (200 μmol m−2 s−1) for 5 min. Presumably, the higher 13C incorporation rate in pre-illuminated cells reflects the fact that CO2 fixation already had been activated (by pre-illumination) prior to the addition of NaH13CO3. Thus, lower 13C incorporation by dark-adapted cells can be attributed to the low activation state of CO2 fixation during photosynthetic induction. Values are the mean ± SD (bars) of three biological replicates. Significant differences were evaluated by a two-tailed non-paired Student's t test; Pp values were as indicated.

In addition to ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO), the primary metabolic enzymes that incorporate CO2 are PEP carboxylase (PepC) and malic enzyme (ME), which are both related to malate metabolism. Since malate is not labeled until 60 s after the initiation of light irradiation (at both of the tested light intensities), 13C incorporation before 60 s is inferred to reflect RuBisCO activity. The amount of incorporated 13C is calculated by multiplying the measured 13C fraction (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 3) by the absolute carbon concentration of each metabolite (shown in Figure 2); these analyses are presented in Supplemental Figure 4. The total amount of incorporated 13C is derived by summing the number of 13C atoms of all measured metabolites (Figure 3B). Notably, 13C incorporation does not start until 12 s (200 μmol m−2 s−1) or 20 s (30 μmol m−2 s−1) after the initiation of light irradiation. On the other hand, 13C incorporation is observed at least 10 s after the addition of NaH13CO3 to cells with activated photosynthesis in response to 5 min of illumination (Figure 3C). Together, these results suggest that the observed delay in the start of 13C incorporation is only partially due to cellular uptake of NaH13CO3. Instead, these data indicate that RuBisCO-mediated CO2 fixation remains inactive during the initial stage of photosynthetic metabolism, immediately following the start of illumination. This delayed onset of CO2 fixation is consistent with the photosynthetic induction phenomena observed in other photosynthetic organisms (Pearcy et al., 1996).

It is interesting to note that labeled carbon is incorporated into malate and fumarate after 120 s, particularly in cells illuminated at 200 μmol m−2 s−1, at a time when other TCA cycle intermediates remained unlabeled (Supplemental Figure 3). This result suggests that malate and fumarate are generated through PEP carboxylase (PEPC), malate dehydrogenase (MDH), and fumarate hydratase. Since generation of malate by MDH involves NADH oxidation, the accumulation of NADH may drive the malate production (Supplemental Figure 5). In steady-state phototrophic metabolism of cyanobacteria, PEP is substantially converted to pyruvate through a three-step bypass pathway (PEPC→MDH→malic enzyme: ME) instead of pyruvate kinase (PK) reaction (Jazmin et al., 2017). The bypass pathway is considered to be important for pyruvate synthesis without ATP generation when PK activity is down-regulated due to high ATP/ADP ratio in light conditions. In addition, a previous study has suggested that the CO2 and NADPH generated by ME could be utilized by CBB cycle, and involved in a carbon concentrating mechanism that is similar to that found in C4 plants (Yang et al., 2002). These might be also functional during the initiation of photosynthesis.

Short-term dynamic MFA (STD-MFA)

Temporal changes in net metabolic fluxes are calculated based on the obtained data. As mentioned above, during the first 60 s of illumination, the observed net metabolic fluxes in pathways other than the CBB cycle and glycolysis are very small. In fact, the concentrations of newly synthesized amino acids do not change substantially within 60 s, even in cells illuminated at 200 μmol m−2 s−1, although the labeled levels of some amino acids (serine, alanine, phenylalanine, tyrosine and ornithine) increased substantially after the first minute of illumination (Supplemental Figure 6). Furthermore, photorespiratory intermediates such as glycolate and glycerate do not accumulate during the first 60 s of illumination (Supplemental Figure 7). However, there remains a possibility that glycogen degradation supplies CBB cycle intermediates during the initiation of photosynthesis. Therefore, the metabolic pathways shown in Supplemental Figure 8A are used for subsequent calculations, focusing on metabolic dynamics during the first 60 s following the initiation of illumination.

To solve Equation (1) and conduct STD-MFA, accumulation rates for metabolites in the metabolic model shown in Supplemental Figure 8A are derived from the slopes obtained between two consecutive concentration data points in Figure 2. In addition to our use of Equation (1), the CO2 fixation rate is calculated as the increase in the rate of total 13C incorporation (Figure 3B). Specifically, the latter parameter is interpreted as the metabolic flux from ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) to 3PG, given that the 13C incorporation experiment mentioned above indicates that all carbon atoms fixed during the first 60 s of illumination are attributable to RuBisCO activity. The net metabolic fluxes of each time interval are estimated by solving these equations simultaneously (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 9, A and B). For more details on the calculation process and equations, see the Materials and Methods section.

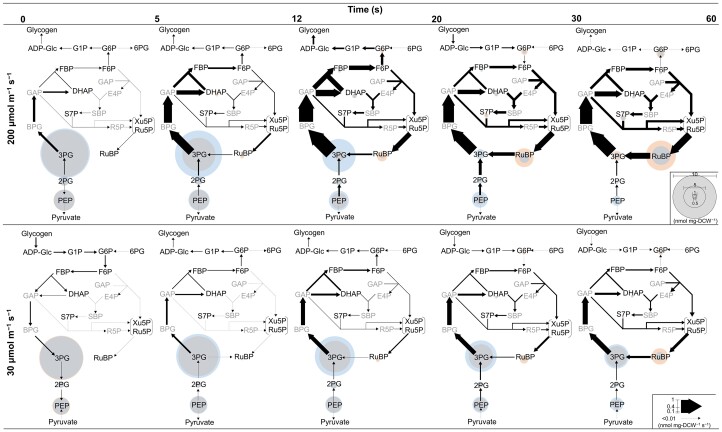

Figure 4.

Estimated change in metabolic flux after initiation of light irradiation at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (upper row) and 30 μmol m−2 s−1 (lower row). Metabolic fluxes are indicated by the thickness of arrows with values indicated by the scale bar in the lower right corner. Metabolite concentrations (except glycogen) at the beginning and end of each time interval are indicated by the diameters of blue and orange circles, respectively. Overlap between orange and blue circles (namely invariant concentration during a time interval) is shown in gray. Abbreviations are the same as in the Figure 2 legend.

The time course of metabolic flux and metabolite concentration distribution in Figure 4 clearly indicates that photosynthetic metabolism in Synechocystis starts by converting dark accumulated 3PG as an initial substrate into RuBP under both two light intensities. On the other hand, the contribution of glycogen degradation in supplying the intermediates is suggested to be small. Another STD-MFA analysis without the glycogen degradation pathway provides similar results to Figure 4, suggesting that effect of glycogen pathway is limited during initiation of photosynthesis (Supplemental Figure 9, C–E). Although the estimated flux values without the glycogen degradation pathway are not uniquely determined due to an over-determined system, they are validated and judged to be reliable, given that almost all of the estimated metabolite accumulation rate values (which were derived from the estimated fluxes) yielded values that are within the mean ± SD range of the measured accumulated rate (Supplemental Figure 10). The minor contribution of glycogen degradation is further rationalized by following two explanations. (1) Decrease and increase ratio of carbon atoms in the metabolic system inside the red frame of Supplemental Figure 11A are almost balanced, indicating either that influx from glycogen degradation into the metabolic system is equivalent to efflux from the system or that both of influx and efflux are nearly zero (Supplemental Figure 11). As the efflux to downstream pathways, such as TCA cycle is suggested to be very small (Figure 3), influx from the glycogen degradation is likely to be negligible. (2) In a mutant lacking glycogen degradation ability, it was reported that dark respiratory activity drops to almost zero, indicating that dark respiration is attributed to glycogen degradation in Synechocystis (Shimakawa et al., 2014). Conversely, the metabolic flux of dark glycogen degradation can be estimated from the respiratory rate. The respiratory rate after 12 h dark incubation (just before light illumination) in this study is 5.6 μmol mg−1 Chl h−1, consistent with the previous study (Shimakawa et al., 2014). Given all the respiratory activity originated from glycogen degradation, the metabolic flux of glycogen degradation in 12 h dark-adapted cells can be calculated as 0.018 nmol mg−1 DCW s−1. Compared with the flux values in Figure 4, the glycogen degradation is suggested to be a minor metabolic pathway during the initiation of photosynthesis.

In Figure 4, the reduction fluxes of 3PG differ greatly between cells illuminated at 30 and 200 μmol m−2 s−1, even before the initiation of CO2 fixation (i.e. during the first 5–20 s). In steady-state photosynthesis, the increased rate of electron donor (NADPH) production from the PET reaction at the higher light intensities is balanced by the rate of electron acceptor (3PG) production that is increased by the elevated CO2 fixation rate. On the other hand, before the onset of CO2 fixation that follows the initiation of light irradiation, excess reducing power can be accumulated because 3PG cannot be produced while NADPH is produced by the PET reaction. Nevertheless, the increase in the reducing fluxes of 3PG with the higher light intensity (200 μmol m−2 s−1) before CO2 fixation suggests that, even before the onset of CO2 fixation, the rate of NADPH production from the PET reaction, which varies with light intensity, is balanced by the rate of 3PG consumption. In addition, it can clearly be seen that 2PG and PEP are converted to 3PG under both light intensities (Figure 4). Therefore, we propose that the accumulation of these glycolytic intermediates provides a “stand-by” state which precedes robust initiation of photosynthesis; thus, these intermediates are expected to play an important role in balancing cofactor regeneration and consumption during activation of the CBB cycle.

Correlation between dark-accumulation of glycolytic intermediates and oxygen evolution

The effects of glycolytic intermediate accumulation on the initiation of photosynthesis are further examined using mutants lacking enzymes involved in dark metabolism. Under dark conditions, cyanobacteria obtain NADPH mainly via the OPP pathway (Wan et al., 2017; Welkie et al., 2018; Hatano et al., 2022). As an initial OPP pathway substrate, glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) is supplied by glycogen degradation through glycogen phosphorylase. In a glycogen phosphorylase-deficient mutant of Synechocystis, decreased accumulation of CBB cycle metabolites has been suggested as a cause of delayed oxygen evolution after dark incubation (Shimakawa et al., 2014). However, the key metabolites that determine CBB cycle activation efficiency have not been reported.

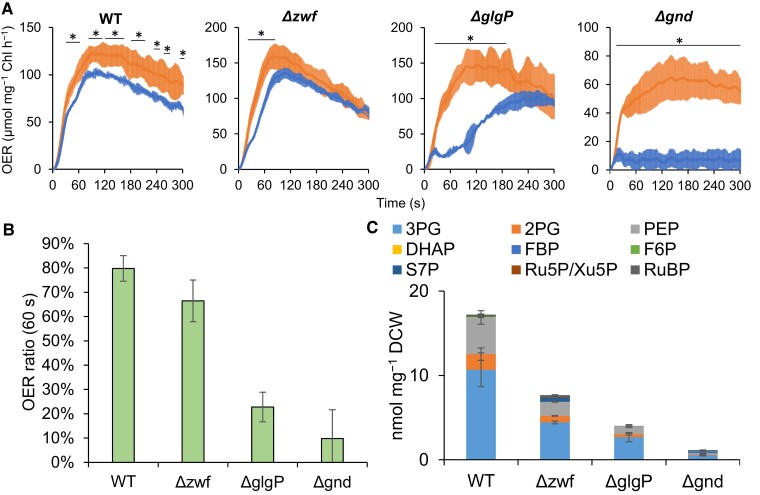

To better understand CBB cycle activation, the relationship between absolute metabolite concentration and oxygen evolution activity, following 12 h dark preincubation periods, is characterized in mutants lacking glycogen phosphorylase, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase or 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (ΔglgP, Δzwf, Δgnd). In dark-adapted cells of all strains, the oxygen evolution rate (OER) significantly decreases immediately after the oxygen evolution onset following light irradiation (Figure 5A). Especially, the OER of dark preincubated Δgnd does not increase during 5 min of light irradiation. To quantify OER activation efficiency, ratios of OER values at 60 s after light irradiation of dark preincubated cells to that of non-dark incubated cells are calculated (Figure 5B). The resulting OER ratio is highest in wild-type (WT) Synechocystis, followed by Δzwf, ΔglgP, Δgnd, in descending order.

Figure 5.

Effect of dark metabolism on initiation of photosynthesis and accumulation of substrates for initial CO2 fixation. A, Oxygen evolution rate (OER) of wild-type (WT) and mutants. Orange and blue lines indicate OER transients of light-adapted and 12 h dark-adapted cells after light irradiation (200 μmol m−2 s−1). B, Ratio of OER value of dark-adapted cells to that of light-adapted cells at 60 s are compared among mutants. C, Absolute concentrations of substrates for initial CO2 fixation in 12 h dark-adapted cells. Values are the mean ± SD (bars) of three biological replicates. Abbreviations are the same as in the Figure 2 legend. Significant differences between the dark- and light-adapted cells were evaluated by a two-tailed non-paired Student's t test (* P < 0.05).

On the other hand, 9 substrates are found to be used for initial CO2 fixation (measured metabolites converted into RuBP during the first 60 s of light irradiation in Figure 4): 3PG, 2PG, PEP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), fructose 6-phosphate (F6P), sedoheptulose 7-phosphate (S7P), Xu5P, and Ru5P. The total amounts of these initial substrates in the 12 h dark preincubated cells follow the same trend as that of the OER ratios (Figure 5C). The three glycolytic intermediates (3PG, 2PG, and PEP) account for 98% of the initial substrates in WT, 90% in Δzwf, 99% in ΔglgP, and 68% in Δgnd. Together these results confirm that photosynthesis activation efficiency is clearly correlated with the accumulated amounts of glycolytic intermediates (r = 0.91). These results demonstrate that the accumulation of glycolytic intermediates under dark conditions is essential for rapid activation of photosynthetic metabolism.

Discussion

A rapid method for estimating metabolic flux kinetics

The STD-MFA method developed in this study is able to quantify rapid changes in metabolic flux over short intervals (within a few minutes), in response to a dynamic phenomenon. This method requires the measurement of time-resolved absolute concentration changes, uptake or evolution rate of one or some metabolites (in present case, carbon uptake rate) and metabolic model refinement based on isotope incorporation data before flux calculation. Previously developed dynamic MFA methods typically are intended to estimate flux change over long periods of culture processes and require technically specialized mathematical approaches (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2011; Niklas et al., 2011). In contrast, STD-MFA permits the direct determination of metabolic flux changes in exchange, albeit while focusing on short-time intervals. We expect that this method also may be of use for understanding other nonstationary rapid metabolic changes that have been the recent focus of attention, such as the end of photosynthesis and adaptation against oxidative stress (Christodoulou et al., 2018; Maruyama et al., 2019).

Regulation mechanisms of the CBB cycle

Metabolic regulation of the CBB cycle includes control of enzyme activity and metabolite accumulation. The present study reveals that accumulation of glycolytic intermediates streamlines activation of photosynthetic metabolism. On the other hand, the detailed regulatory mechanisms of CBB cycle enzymes are different among photosynthetic organisms (Michelet et al., 2013; Gütle et al., 2017). In addition, multiple enzymatic activations simultaneously occur during the initiation of photosynthesis in vivo (Buchanan, 1980; Portis Jr, 1995). The present in vivo metabolomic data in Figure 2 is consistent with the following enzymatic activations in Synechocystis.

Metabolic flux of conversion of 3PG remains small until 5 s (200 μmol m−1 s−1) or 12 s (30 μmol m−1 s−1), indicating the presence of regulation in phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and/or GAPDH. Cyanobacterial PGK and GAPDH are activated by reduction of disulfide bonds (Tsukamoto et al., 2013; McFarlane et al., 2019). Transient accumulation of FBP indicates the existence of an activation period for the fructose-1,6-/sedohepturose-1,7-bisphosphatase (FBP/SBPase) enzyme. FBP/SBPase in Synechocystis is activated by the reduction of a disulfide bond and binding of Mg2+, and this enzyme is inhibited allosterically by the binding of AMP (Feng et al., 2014; Mallén-Ponce et al., 2021). Indeed, a rapid decrease in AMP concentration was confirmed after light irradiation (Supplemental Figure 5). In addition, temporal accumulation of DHAP upon irradiation with 200 μmol m−2 s−1 light may be attributable to the transient rate-limitation of FBP/SBPase. Similar to the behavior of FBP, the accumulation and subsequent decrease of RuBP suggests a phase shift from inactivated to activated RuBisCO. RuBisCO activity is activated by various factors: (a) carbamylation to the activator lysine and binding of a magnesium ion to the carbamate anion as essential regulations (Lorimer et al., 1976; Miziorko, 1979), (b) effectors such as orthophosphate (Marcus and Gurevitz, 2000), several phosphorylated sugars and NADPH (Tabita and Colletti, 1979), (c) cysteine redox state (Marcus et al., 2003; Moreno et al., 2008), (d) RuBisCO activase (Portis Jr, 1995). Among these activation processes, Synechocystis lacks RuBisCO activase. In addition, cyanobacteria encapsulate RuBisCO enzymes into protein-encased microcompartments called the carboxysome (Rae et al., 2013). Initiation of CO2 fixation requires entrance of RuBisCO substrate, RuBP into the carboxysome. Although kinetics of this RuBP uptake is unknown, this process might affect activation kinetics of CBB cycle. Note that similar dynamics of the RuBP pool size have been observed after a dark-to-light transition in plant leaves, and are associated with RuBisCO activation (Perchorowicz et al., 1981; Seemann et al., 1988).

Free energy analysis provides further insight into the regulation in the CBB cycle. Thermodynamic feasibility is estimated by the reaction Gibbs energy change (ΔrG), calculated based on the following equation:

| (2) |

where ΔrG° is the standard reaction Gibbs energy change, R is the ideal gas constant, T is the temperature, and Q is the reaction quotient, which includes concentration terms. The availability of absolute concentration data enables assessment of the thermodynamically feasible flux directions. Corresponding ΔrG° values are obtained from the eQuilibrator database (Beber et al., 2022; Supplemental Table 1). The ΔrG value of conversion from PEP to pyruvate catalyzed by pyruvate kinase (PK) is found to be a very negative value compared with that of heterotrophic organisms (Park et al., 2016; Supplemental Figure 12). Along with GAPDH and PGK, PK activity regulation may contribute to the observed accumulation of 3PG, 2PG, and PEP.

Essential metabolic pathways for dark-accumulation of glycolytic intermediates

Accumulation of glycolytic intermediates decreases in Δzwf, ΔglgP, and Δgnd, suggesting that the accumulated glycolytic intermediates are derived from glycogen degradation and the OPP pathway. The first step of the OPP pathway is the irreversible conversion of G6P into 6PG by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH). Then, 6PG is decarboxylated into Ru5P by 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGDH). Accumulation of initial CO2 fixation substrates in Δgnd is much lower than in Δzwf (Figure 5C). This may be explained by the G6PDH-mediated conversion of glycogen-derived G6P into 6PG, with will then accumulate if it is not readily converted to other metabolites. Indeed, 6PG accumulation in Δgnd (45.0 nmol mg−1 DCW) is about 4,000-fold higher than in the wild-type (0.011 nmol mg−1 DCW) after dark incubation. On the other hand, G6P in Δzwf can be metabolized by other pathways such as the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway, which might prevent the depletion of glycolytic intermediates.

Importance and conservation of intermediate pool size

Although concentration robustness is generally considered to be a fundamental factor for maintaining cellular functions (Eloundou-Mbebi et al., 2016), the precise role of metabolic robustness in photosynthetic organisms has not been clarified. Balancing photosynthetic supply and metabolic demand of NADPH is important for operating stable CO2 fixation and avoiding oxidative stress by redox imbalance state (Shimakawa and Miyake, 2018; Matuszyńska et al., 2019). In this study, it is suggested that accumulation of glycolytic intermediates acts as a buffering system that compensates for the gap between supply and demand of NADPH, and ensures rapid photosynthesis start. Indeed, lower accumulation of the glycolytic intermediates resulted in inefficient photosynthetic activity (Figure 5). A previous study showed that 3PG is the most abundant in CBB cycle intermediates in three cyanobacterial species including Synechocystis (Dempo et al., 2014). This metabolite distribution is characteristic compared with that of heterotrophic organisms (Park et al., 2016; Supplemental Figure 13). Moreover, rapid consumption of phosphoglycerate upon illumination as shown in Figure 2 was also observed in algae, the chloroplast of spinach protoplasts, and leaves of wheat (Bassham et al., 1956; Stitt et al., 1980; Kobza and Edwards, 1987). These facts support the functional importance and conservation of glycolytic intermediate accumulation for robust photosynthesis.

Materials and methods

Growth conditions

This work employed a glucose-tolerant wild-type strain of Synechocystis (Williams, 1988) that was grown and stored on solid BG-11 media plates containing 1.5% w/v Bacto agar. Pre-culturing was performed in 200 ml flasks containing 50 ml each of liquid BG-11 medium buffered with 20 mM 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, pH 7.5); each flask was inoculated with cells harvested from the agar plates. These flasks then were cultured at 30°C in ambient air with shaking at 100 rpm; illumination at an intensity of 30 µmol m−2s−1 was provided by white light-emitting diode (LED) lights. The main culture was initiated by adding pre-culture grown for 4 days into 70 ml of the BG-11 medium to give an optical density of 0.05 at 730 nm (OD730). The growth condition of the main culture was the same as that of the pre-culture. The dry cell weight (DCW) was measured after harvesting cells by centrifugation and lyophilization. The obtained relationship between the OD730 value and DCW (DCW = 0.1998 × OD730 × V + 0.0974; R2 = 0.982; n = 9; V is volume of cell suspension) was used for estimating DCW from the OD730 value.

Preparation of 13C isotope-labeled internal standard (13C-IS)

Synechocystis cells in pre-culture were inoculated to an OD730 of 0.05 in a serum bottle containing 60 ml modified BG-11 medium supplemented with 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 25 mM NaH13CO3 (in place of the unlabeled Na2CO3 included in the standard BG-11 medium). The culture serum bottle was sealed, followed by flushing with N2 gas to remove unlabeled ambient CO2. The growth conditions used for the labeled culture were the same as those used for the pre-culture and main culture. Cells grown for 3 days were harvested and resuspended in fresh modified BG-11 to avoid pH increase during cultivation with NaH13CO3 as the sole carbon source. The labeled culture then was grown under the same conditions for another 3 days, followed by extraction of uniformly labeled metabolites, as described below.

The entire volume of the labeled culture was harvested by centrifugation, washed with 1 mM NaH13CO3 solution, and then resuspended in 9 ml of 1 mM NaH13CO3. The resulting cell suspension was illuminated for 90 s with white LED light at an intensity of 200 µmol m−2s−1 (to maximize extraction yield of CBB cycle intermediates), and placed into a mixture of 9 ml PCI (Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol 25:24:1 Mixed, pH 7.9, Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) and 60 µl 0.5 M N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (CAPS, pH 10.6) for metabolite extraction. A PCI solution is selected as the extraction solution because PCI extraction enables rapid and efficient extraction of NADPH from Synechocystis (Tanaka et al., 2021). The extraction mixture was centrifuged at 4°C and 8,000 ×g for 3 min. Twelve to 13 fractions of the water layer were then aliquoted into microtubes and lyophilized.

One of the dried aliquots was dissolved in 20 µl of standard mixture containing prepared unlabeled compounds. The sample was analyzed by CE-MS) (CE, Agilent G7100; MS, Agilent G6224AA LC/MSD TOF; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) as described previously (Hasunuma et al., 2013). Absolute concentrations of the uniformly labeled isotopomer (Cn) were derived as follows:

| (3) |

where, Sn and S0 are the peak areas of uniformly 13C-labeled (namely, the number of 13C atoms in a n-carbon compound is equal to n) and unlabeled standard signals, respectively, and C0 is the prepared concentration of the unlabeled standard.

Metabolite extraction with rapid sampling and analysis

To perform metabolite sampling for analyses of absolute concentration and 13C incorporation after the transition from dark to light, a main culture grown for 6 days was dark-adapted for 12 h. A calculated volume (90/OD730, in mL) of the dark-adapted cell culture was harvested by centrifugation at 8,000×g for 5 min. To analyze intracellular metabolites, the cells were separated from the growth medium and were washed with 4 ml of 1 mM NaHCO3 (for absolute concentration analysis) or 1 mM NaH13CO3 (for 13C incorporation analysis), and harvested again by centrifugation. The washed cells were resuspended in 6.8 ml of 1 mM NaHCO3 (for absolute concentration analysis) or 1 mM NaH13CO3 (for 13C incorporation analysis). The medium exchange was performed at air-conditioned room temperature (around 25°C). Although the exchange of medium for NaHCO3 solution is a typical pretreatment for measuring photosynthetic activity of fresh-water cyanobacteria (Shimakawa et al., 2015), there is a possibility that the medium exchange and/or temperature change affect metabolism. However, as dark metabolic state such as accumulation of 3PG is consistent with previous reports (Bassham et al., 1956; Stitt et al., 1980; Kobza and Edwards, 1987), the experimental preparations are likely to have little effect on the metabolism.

Nine aliquots (750 µl each) of the resulting cell suspension were then loaded into clear pipet tips (Supplemental Figure 14). Up to this point, light irradiation was avoided during the procedure to keep the cells in the dark-adapted state. Irradiation of all the aliquots with white LED light at an intensity of 200 ± 10 µmol m−2s−1 or 30 ± 2 µmol m−2s−1 was initiated, followed by sampling of the cells at the indicated time points by adding into 750 µl PCI supplemented with 13C-IS dissolved in 20 µl water (for absolute concentration analysis) or with 5 µl of 0.5 M CAPS (pH 10.6) (for 13C incorporation analysis). The cell suspension before illumination was extracted as the nominal 0-s sample. To precisely determine the amount of extracted cells, the OD730 of the final cell suspension was measured. After the extraction mixtures were centrifuged at 4°C at 12,000×g for 2 min, harvested aliquots of the water layer were lyophilized.

The lyophilized samples were dissolved in 20 µl of 0.4 mM piperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) and analyzed by CE-MS as described above. Absolute concentrations of each metabolite (C’) were derived as follows:

| (4) |

where and are the peak areas of unlabeled and uniformly 13C-labeled IS signals, respectively, W represents DCW, and V is the sample volume for CE-MS analysis. The intracellular concentration (mM) was calculated by using the values: 5 × 107 cells/ml/OD730 (Kohga et al., 2021) and 4.4 × 10−15 L/cell (Cameron and Pakrasi, 2010). 13C fractions were calculated as described previously (Hasunuma et al., 2018).

Short-term dynamic MFA (STD-MFA)

To estimate the temporal changes of 20 (with glycogen degradation pathways) or 18 (without glycogen degradation pathways) fluxes in the metabolic map shown in Supplemental Figure 8A, metabolite accumulation rates ri(t) in Equation (1) were derived from the slope taken between two consecutive concentration data points shown in Figure 2. Accumulation rates of metabolites under the detection limit (E4P, R5P, GAP <0.001 nmol/mg DCW) and peak-unidentified metabolites (BPG and SBP) were set to zero. In addition, the CO2 fixation rate derived from the slope taken between two consecutive data points shown in Figure 3 was regarded as the metabolic flux of RuBisCO (i.e. the conversion of RuBP to 3PG). The set of equations was represented in matrix notation as follows:

| (5) |

where, A is matrix of stoichiometric coefficients, x(t) is the flux vector, and r(t) is the metabolite accumulation rate vector. The specific forms of Equation (5) corresponding to the case with and without glycogen degradation pathways are shown in Supplemental Figure 8, B and C, respectively. In case of the systems with glycogen degradation pathways, the number of unknown flux parameter is equal to that of the equations. Thus the solution to Supplemental Figure 8B is as follows.

| (6) |

On the other hand, in case of the systems without glycogen degradation pathways, the number of unknown flux parameter is less than that of the equations. Although the unique solution cannot be determined, the most plausible weighted least squares solution to the equation shown in Supplemental Figure 8C is as follows:

| (7) |

where the superscripts ^ and ¯ denote estimated and measured quantities (respectively), and W is a 19-dimensional weighting diagonal matrix, whose diagonal elements are the reciprocal of the variance of the measured metabolic accumulation rate values. Variance values for the accumulation rate of E4P, R5P, GAP, BPG, and SBP, and for the CO2 fixation rate, were set to 10−15 (i.e. a value that was effectively zero). To evaluate the reliability of the estimated fluxes, the metabolite accumulation rates were calculated as follows:

| (8) |

The estimated and measured metabolite accumulation rate values are compared in Supplemental Figure 10.

Oxygen evolution measurement

Synechocystis cells were collected and resuspended in the same way as the preparation process in the metabolite sampling experiment described above. Whole-cell oxygen evolution was measured with light illumination at intensities of 200 µmol m−2 s−1 in a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech Instruments) containing 1 ml of the cell suspension. The apparent oxygen evolution rate was derived from the slope of the oxygen trace data, and normalized by chlorophyll a concentration of the cell suspension determined as described in Shimakawa et al. (2014). The final net oxygen evolution rate was obtained by subtracting the dark respiratory rate from the apparent oxygen evolution rate as described in Shinde et al. (2020).

Statistical analyses

Microsoft Excel was used for statistical analysis. The number of biological replicates are indicated in Figure legends. Data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences and correlation were evaluated by Student's t test and correlation coefficient, respectively.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1 . Fraction of uniformly labeled metabolite in 13C internal standards.

Supplemental Figure S2 . Fractions of extracellular metabolites at 2 min after the start of illumination with an intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1.

Supplemental Figure S3 . Time course 13C metabolite fractions following light irradiation at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 or 30 μmol m−2 s−1.

Supplemental Figure S4 . Time course of 13C level in each metabolite.

Supplemental Figure S5 . Concentration transients of cofactors during photosynthetic induction.

Supplemental Figure S6 . Concentration and 13C fraction transients of amino acids during photosynthetic induction of cells illuminated at an intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1.

Supplemental Figure S7 . Concentration transients of intermediates in photorespiration pathway during photosynthetic induction.

Supplemental Figure S8 . Short-term dynamic metabolic flux analysis (STD-MFA).

Supplemental Figure S9 . Estimated metabolic flux changes during the initiation of photosynthesis.

Supplemental Figure S10 . Measured and estimated metabolic accumulation rates.

Supplemental Figure S11 . Carbon mass balance among the metabolites.

Supplemental Figure S12 . Free energy analysis.

Supplemental Figure S13 . Comparison of absolute metabolite concentrations between Escherichia coli and Synechocystis.

Supplemental Figure S14 . Rapid sampling system used in this study.

Supplemental Table S1 . Standard reaction Gibbs energy change from eQuilibrator database.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. C. Miyake (Kobe University) and Dr. Ginga Shimakawa (Kwansei Gakuin University) for kindly providing the mutants used in this work.

Contributor Information

Kenya Tanaka, Engineering Biology Research Center, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; Graduate School of Science, Innovation and Technology, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; Research Center for Solar Energy Chemistry, Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-8531, Japan.

Tomokazu Shirai, Graduate School of Science, Innovation and Technology, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, 1-7-22 Suehiro, Tsurumi, Yokohama, Kanagawa 230-0045, Japan.

Christopher J Vavricka, Department of Biotechnology and Life Science, Graduate School of Engineering, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, 2-24-16 Naka-cho, Koganei, Tokyo, 184-8588, Japan.

Mami Matsuda, Graduate School of Science, Innovation and Technology, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan.

Akihiko Kondo, Engineering Biology Research Center, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; Graduate School of Science, Innovation and Technology, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, 1-7-22 Suehiro, Tsurumi, Yokohama, Kanagawa 230-0045, Japan; Department of Chemical Science and Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan.

Tomohisa Hasunuma, Engineering Biology Research Center, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; Graduate School of Science, Innovation and Technology, Kobe University, 1-1 Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, 1-7-22 Suehiro, Tsurumi, Yokohama, Kanagawa 230-0045, Japan.

Funding

This work was supported by the Mirai Program [grant number JPMJMI19E4] from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan, and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI Grant Number 21J00113 and 22K15142.

References

- Annesley TM (2003) Ion suppression in mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 49(7): 1041–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassham JA, Shibata K, Steenberg K, Bourdon J, Calvin M (1956) The photosynthetic cycle and respiration: light-dark transients. J Am Chem Soc 78(16): 4120–4124 [Google Scholar]

- Beber ME, Gollub MG, Mozaffari D, Shebek KM, Flamholz AI, Milo R, Noor E (2022) Equilibrator 30: a database solution for thermodynamic constant estimation. Nucleic Acids Res 50(D1): D603–D609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Kimball EH, Gao M, Osterhout R, Van Dien SJ, Rabinowitz JD (2009) Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol 5(8): 593–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan BB (1980) Role of light in the regulation of chloroplast enzymes. Ann Rev Plant Physiol 31(1): 341–374 [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JC, Pakrasi HB (2010) Essential role of glutathione in acclimation to environmental and redox perturbations in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Plant Physiol 154(4): 1672–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou D, Link H, Fuhrer T, Kochanowski K, Gerosa L, Sauer U (2018) Reserve flux capacity in the pentose phosphate pathway enables Escherichia coli’s Rapid response to oxidative stress. Cell Syst 6(5): 569–578.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempo Y, Ohta E, Nakayama Y, Bamba T, Fukusaki E (2014) Molar-based targeted metabolic profiling of cyanobacterial strains with potential for biological production. Metabolites 4(2): 499–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloundou-Mbebi JM, Küken A, Omranian N, Kleessen S, Neigenfind J, Basler G, Nikoloski Z. (2016) A network property necessary for concentration robustness. Nat Commun 7(1): 13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Sun Y, Deng H, Li D, Wan J, Wang X, Wang W, Liao X, Ren Y, Hu X (2014) Structural and biochemical characterization of fructose-1,6/sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain 6803. FEBS J 281(3): 916–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flombaum P, Gallegos JL, Gordillo RA, Rincón J, Zabala LL, Jiao N, Karl DM, Li WK, Lomas MW, Veneziano D, (2013) Present and future global distributions of the marine Cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(24): 9824–9829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gütle DD, Roret T, Hecker A, Reski R, Jacquot JP (2017) Dithiol disulphide exchange in redox regulation of chloroplast enzymes in response to evolutionary and structural constraints. Plant Sci 255: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasunuma T, Kikuyama F, Matsuda M, Aikawa S, Izumi Y, Kondo A (2013) Dynamic metabolic profiling of cyanobacterial glycogen biosynthesis under conditions of nitrate depletion. J Exp Bot 64(10): 2943–2954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasunuma T, Matsuda M, Kato Y, Vavricka CJ, Kondo A (2018) Temperature enhanced succinate production concurrent with increased central metabolism turnover in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Metab Eng 48: 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano J, Kusama S, Tanaka K, Kohara A, Miyake C, Nakanishi S, Shimakawa G (2022) NADPH Production in dark stages is critical for cyanobacterial photocurrent generation: a study using mutants deficient in oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. Photosynth Res 153(1–2): 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins DA, Fu F (2017) Microorganisms and ocean global change. Nat Microbiol 2(6): 17058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazmin LJ, Xu Y, Cheah YE, Adebiyi AO, Johnson CH, Young JD (2017) Isotopically nonstationary 13C flux analysis of cyanobacterial isobutyraldehyde production. Metab Eng 42: 9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauny J, Sétif P (2014) NADPH Fluorescence in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803: a versatile probe for in vivo measurements of rates yields and pools. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837(6): 792–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobza J, Edwards GE (1987) The photosynthetic induction response in wheat leaves: net CO2 uptake enzyme activation and leaf metabolites. Planta 171(4): 549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohga H, Saito Y, Kanamaru M, Uchiyama J, Ohta H (2021) The lack of the cell division protein FtsZ induced generation of giant cells under acidic stress in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC6803. Photosynth Res 150(1–3): 343–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty RW, Antoniewicz MR (2011) Dynamic metabolic flux analysis (DMFA): a framework for determining fluxes at metabolic non-steady state. Metab Eng 13(6): 745–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer GH, Badger MR, Andrews TJ (1976) The activation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase by carbon dioxide and magnesium ions equilibria kinetics a suggested mechanisms and physiological implications. Biochem 15(3): 529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallén-Ponce MJ, Huertas MJ, Sánchez-Riego AM, Florencio FJ (2021) Depletion of m-type thioredoxin impairs photosynthesis carbon fixation and oxidative stress in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol 187(3): 1325–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y, Altman-Gueta H, Finkler A, Gurevitz M (2003) Dual role of cysteine 172 in redox regulation of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity and degradation. J Bacteriol. 185(5): 1509–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y, Gurevitz M (2000) Activation of cyanobacterial RuBP-carboxylase/oxygenase is facilitated by inorganic phosphate via two independent mechanisms. Eur J Biochem 267(19): 5995–6003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama M, Nishiguchi H, Toyoshima M, Okahashi N, Matsuda F, Shimizu H (2019) Time-resolved analysis of short term metabolic adaptation at dark transition in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. J Biosci Bioeng 128(4): 424–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszyńska A, Saadat NP, Ebenhöh O (2019) Balancing energy supply during photosynthesis—a theoretical perspective. Physiol Plant 166(1): 392–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane CR, Shah NR, Kabasakal BV, Echeverria B, Cotton CAR, Bubeck D, Murray JW (2019) Structural basis of light-induced redox regulation in the Calvin-Benson cycle in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(42): 20984–20990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelet L, Zaffagnini M, Morisse S, Sparla F, Pérez-Pérez ME, Francia F, Danon A, Marchand CH, Fermani S, Trost P, (2013) Redox regulation of the Calvin-Benson cycle: something old something new. Front Plant Sci 4: 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miziorko HM (1979) Ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase evidence in support of the existence of distinct CO2 activator and CO2 substrate sites. J Biol Chem 254(2): 270–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J, García-Murria MJ, Marín-Navarro J (2008) Redox modulation of Rubisco conformation and activity through its cysteine residues. J Exp Bot 59(7): 1605–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklas J, Schräder E, Sandig V, Noll T, Heinzle E (2011) Quantitative characterization of metabolism and metabolic shifts during growth of the new human cell line AGE1HN using time resolved metabolic flux analysis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 34(5): 533–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Okahashi N, Matsuda F, Shimizu H (2015) Absolute quantitation of glycolytic intermediates reveals thermodynamic shifts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains lacking PFK1 or ZWF1 genes. J Biosci Bioeng 120(3): 280–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JO, Rubin SA, Xu YF, Amador-Noguez D, Fan J, Shlomi T, Rabinowitz JD (2016) Metabolite concentrations fluxes and free energies imply efficient enzyme usage. Nat Chem Biol 12(7): 482–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW, Krall JP, Sassenrath-Cole GF (1996) Photosynthesis in fluctuating light environments. InBaker NR, eds, Photosynthesis and the Environment. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 321–346 [Google Scholar]

- Perchorowicz JT, Raynes DA, Jensen RG (1981) Light limitation of photosynthesis and activation of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase in wheat seedlings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78(5): 2985–2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinu FR, Villas-Boas SG, Aggio R (2017) Analysis of intracellular metabolites from microorganisms: quenching and extraction protocols. Metabolites 7(4): E53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portis AR Jr (1995) The regulation of Rubisco by Rubisco Activase. J Exp Bot 46(special_issue): 1285–1291 [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JD, Kimball E (2007) Acidic acetonitrile for cellular metabolome extraction from Escherichia coli. Anal Chem 79(16): 6167–6173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae BD, Long BM, Badger MR, Price GD (2013) Functions compositions and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77(3): 357–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Baracaldo P, Bianchini G, Wilson JD, Knoll AH (2022) Cyanobacteria and biogeochemical cycles through earth history. Trends Microbiol 30(2): 143–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer U (2006) Metabolic networks in motion: 13C-based flux analysis. Mol Syst Biol 2(1): 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann JR, Kirschbaum MU, Sharkey TD, Pearcy RW (1988) Regulation of Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase activity in Alocasia macrorrhiza in response to step changes in irradiance. Plant Physiol 88(1): 148–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimakawa G, Hasunuma T, Kondo A, Matsuda M, Makino A, Miyake C (2014) Respiration accumulates Calvin cycle intermediates for the rapid start of photosynthesis in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 78(12): 1997–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimakawa G, Miyake C (2018) Oxidation of P700 ensures robust photosynthesis. Front Plant Sci 9: 1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimakawa G, Shaku K, Nishi A, Hayashi R, Yamamoto H, Sakamoto K, Makino A, Miyake C (2015) FLAVODIIRON2 And FLAVODIIRON4 proteins mediate an oxygen-dependent alternative electron flow in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 under CO2-limited conditions. Plant Physiol 167(2): 472–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H, Toya Y (2021) Recent advances in metabolic engineering-integration of in silico design and experimental analysis of metabolic pathways. J Biosci Bioeng 132(5): 429–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde S, Zhang X, Singapuri SP, Kalra I, Liu X, Morgan-Kiss RM, Wang X (2020) Glycogen metabolism supports photosynthesis start through the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway in Cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol 182(1): 507–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Wirtz W, Heldt HW (1980) Metabolite levels during induction in the chloroplast and extrachloroplast compartments of spinach protoplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 593(1): 85–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabita FR, Colletti C (1979) Carbon dioxide assimilation in cyanobacteria: regulation of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase. J Bacteriol 140(2): 452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamoi M, Miyazaki T, Fukamizo T, Shigeoka S (2005) The Calvin cycle in cyanobacteria is regulated by CP12 via the NAD(H)/NADP(H) ratio under light/dark conditions. Plant J 42(4): 504–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Shimakawa G, Tabata H, Kusama S, Miyake C, Nakanishi S (2021) Quantification of NAD(P)H in cyanobacterial cells by a phenol extraction method. Photosynth Res 148(1–2): 57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, Fukushima Y, Hara S, Hisabori T (2013) Redox control of the activity of phosphoglycerate kinase in Synechocystis sp PCC6803. Plant Cell Physiol 54(4): 484–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallino JJ, Stephanopoulos G (1993) Metabolic flux distributions in Corynebacterium glutamicum during growth and lysine overproduction. Biotechnol Bioeng 41(6): 633–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan N, DeLorenzo DM, He L, You L, Immethun CM, Wang G, Baidoo EEK, Hollinshead W, Keasling JD, Moon TS, (2017) Cyanobacterial carbon metabolism: Fluxome plasticity and oxygen dependence. Biotechnol Bioeng 114(7): 1593–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welkie DG, Rubin BE, Chang YG, Diamond S, Rifkin SA, LiWang A, Golden SS (2018) Genome-wide fitness assessment during diurnal growth reveals an expanded role of the cyanobacterial circadian clock protein KaiA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115(30): E7174–E7183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JGK (1988) Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis 6803. Methods Enzymol 167: 766–778 [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Mashego MR, van Dam JC, Proell AM, Vinke JL, Ras C, van Winden WA, van Gulik WM, Heijnen JJ (2005) Quantitative analysis of the microbial metabolome by isotope dilution mass spectrometry using uniformly 13C-labeled cell extracts as internal standards. Anal Biochem 336(2): 164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Hua Q, Shimizu K (2002) Metabolic flux analysis in Synechocystis using isotope distribution from 13C-labeled glucose. Metab Eng 4(3): 202–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Lee BH, Moon Y, Spalding MH, Jane JL (2014) Glycogen synthase isoforms in Synechocystis sp PCC6803: identification of different roles to produce glycogen by targeted mutagenesis. PLoS One 9(3): e91524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JD, Shastri AA, Stephanopoulos G, Morgan JA (2011) Mapping photoautotrophic metabolism with isotopically nonstationary 13C flux analysis. Metab Eng 13(6): 656–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.