Keywords: endothelium, hypertension, microcirculation, sex, TRPV4

Abstract

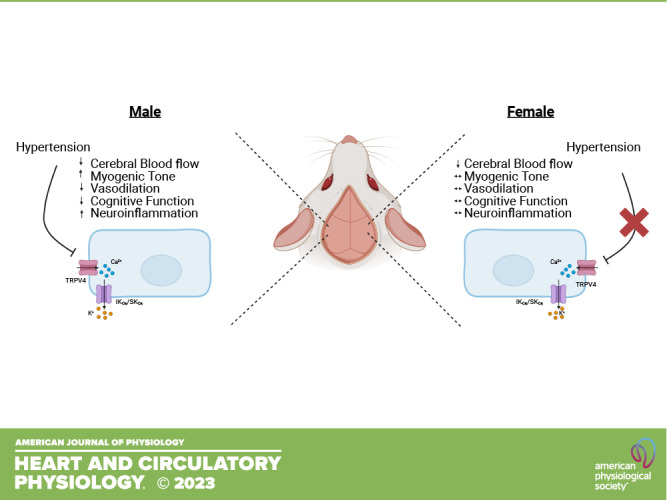

Hypertension is a leading modifiable risk factor for cerebral small vessel disease. Our laboratory has shown that endothelium-dependent dilation in cerebral parenchymal arterioles (PAs) is dependent on transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) activation, and this pathway is impaired in hypertension. This impaired dilation is associated with cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation. Epidemiological evidence suggests that women with midlife hypertension have an increased dementia risk that does not exist in age-matched men, though the mechanisms responsible for this are unclear. This study aimed to determine the sex differences in young, hypertensive mice to serve as a foundation for future determination of sex differences at midlife. We tested the hypothesis that young hypertensive female mice would be protected from the impaired TRPV4-mediated PA dilation and cognitive dysfunction observed in male mice. Angiotensin II (ANG II)-filled osmotic minipumps (800 ng/kg/min, 4 wk) were implanted in 16- to 19-wk-old male C56BL/6 mice. Age-matched female mice received either 800 ng/kg/min or 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II. Sham-operated mice served as controls. Systolic blood pressure was elevated in ANG II-treated male mice and in 1,200 ng ANG II-treated female mice versus sex-matched shams. PA dilation in response to the TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A (10−9–10−5 M) was impaired in hypertensive male mice, which was associated with cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation, reproducing our previous findings. Hypertensive female mice exhibited normal TRPV4-mediated PA dilation and were cognitively intact. Female mice also showed fewer signs of neuroinflammation than male mice. Determining the sex differences in cerebrovascular health in hypertension is critical for developing effective therapeutic strategies for women.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Vascular dementia is a significant public health concern, and the effect of biological sex on dementia development is not well understood. TRPV4 channels are essential regulators of cerebral parenchymal arteriolar function and cognition. Hypertension impairs TRPV4-mediated dilation and memory in male rodents. Data presented here suggest female sex protects against impaired TRPV4 dilation and cognitive dysfunction during hypertension. These data advance our understanding of the influence of biological sex on cerebrovascular health in hypertension.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a leading modifiable risk factor for vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID). Hypertension results in arterial remodeling and impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in peripheral and cerebral arteries and arterioles, contributing to vascular insufficiency. Inadequate cerebral blood flow can lead to cerebral hypoperfusion and, ultimately, cognitive decline. VCID encompasses a wide range of cognitive disorders that result from cerebrovascular pathology. VCID can progress to vascular dementia, the second leading cause of dementia following Alzheimer’s disease. Importantly, VCID often presents as “mixed dementia,” and nearly half the patients with Alzheimer’s disease are found to have vascular damage at autopsy (1, 2). The additional vascular insult exacerbates existing dementia and worsens clinical outcomes.

Epidemiological evidence suggests an important sex difference in the contribution of hypertension to VCID development. Although data are mixed concerning sex differences in overall VCID prevalence, multiple studies have demonstrated that hypertension increases VCID risk in women more significantly than in men (3, 4). Hypertension in midlife is particularly detrimental, with a 65% increased dementia risk in women but not men (3). The reasons behind this sex difference are not well understood because female subjects were excluded from many studies investigating cerebrovascular mechanisms, which has prevented the field from advancing. Understanding the sex differences in basic cerebrovascular physiology is essential in identifying targeted therapies for women.

The present study focuses on cerebral parenchymal arterioles (PAs), which are important contributors to cerebrovascular resistance. These small arterioles direct blood flow from the pial arteries and arterioles to the capillaries, which are the critical sites of gas and nutrient exchange. PAs lack collateral connections and are therefore considered the weak link in cerebral perfusion. Appropriate PA perfusion is so crucial that occlusion of a single PA is sufficient to cause cognitive decline (5, 6). PAs are highly dependent on endothelium-derived hyperpolarization (EDH) for dilation, which occurs through the activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channels. Endothelial TRPV4 activation triggers a robust calcium influx that activates intermediate and small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (IKCa/SKCa), causing a hyperpolarization that ultimately leads to vasodilation. We demonstrated that TRPV4-mediated dilation of PAs is impaired in male mice with angiotensin II (ANG II)-induced hypertension (7, 8). These impairments were associated with signs of neuroinflammation. Even in the absence of hypertension, impaired TRPV4 function in PAs is associated with cognitive decline (8–10). It is well established that female sex hormones offer protection against endothelial dysfunction by maintaining nitric oxide (NO) production, partially through mechanisms involving reduced inflammation (11–15). We know much less about the effects of sex on EDH-mediated dilation, particularly in the cerebral circulation, where impaired vascular function can precipitate dementia. Therefore, using a model of ANG II hypertension in young male and female mice, we tested the hypothesis that female mice will be protected from impaired TRPV4-mediated dilation, impaired cognition, and inflammation observed in male mice in hypertension.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Experimental Models and Treatment

All experimental protocols were approved by the Michigan State University’s Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male and female C57BL/6 mice (n = 142 total; n = 54 males and 88 females) were purchased from Charles River Laboratory. All animals studied were singly housed on a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Mice were fed standard rodent chow with 0.2% dietary sodium (Teklad diet 2918, Envigo). Hypertension was induced in 16- to 19-wk-old male and female C57BL/6 mice. Treatment lasted for 4 wk, and mice were euthanized at 20–23 wk of age. Mice were randomized into treatment groups.

ANG II Infusion

To induce hypertension, ANG II was infused subcutaneously in using osmotic minipumps (Alzet model 1004, Durect Corp, Cupertino, CA). Male mice received an ANG II dose of 800 ng/kg/min dissolved in sterile saline (ANG II, Cat. No. 17150, Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI); this dose has been used previously by our group and others to induce hypertension (7, 8, 16, 17). Because young female mice are resistant to ANG II hypertension (17), we determined an ANG II dose that produces a significant elevation in systolic blood pressure in female mice. Accordingly, one group of female mice received 800 ng/kg/min to match the dose in the male mice, and a separate group received a dose of 1,200 ng/kg/min to produce a significant elevation in blood pressure. To insert the minipumps, mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane in oxygen, and body temperature was maintained at 37°C. The analgesic Rimadyl (5 mg/kg sc) and the antibiotic Baytril (5 mg/kg im) were administered immediately before surgery. A subcutaneous pocket was made, and minipumps were inserted. Control mice received sham operations; these mice are referred to as sham(s). These mice were anesthetized, and a subcutaneous pocket was made, but minipumps were not inserted. Incisions were closed with silk sutures. Mice were allowed to recover for 1 wk after the surgical implantation of the osmotic minipump.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure was measured in conscious mice via tail-cuff plethysmography using a RTBP1001 tail-cuff blood pressure system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Mice were acclimatized to the procedure during the second and third week after surgery. The blood pressures reported here were recorded during the fourth week postsurgery.

Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging

Pial blood flow was measured just before euthanasia using laser speckle contrast imaging. Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane in oxygen. The scalp was removed, and the skull was cleared of connective tissue. A thin coat of clear nail polish was applied to the skull to improve image resolution. To minimize the vasodilatory effects of isoflurane (18), the concentration administered was reduced to 1% for 5 min before pial blood flow was measured (21 images/min for 1 min). Regions of interest were defined as the parietal, frontal, and temporal regions in the left and right hemispheres (19). Mean blood flow in each of these regions was compared among treatment groups. Images were analyzed using PIMSoft software (PeriMed, Las Vegas, NV).

Pressure Myography

Pressure myography was used to assess the endothelial function and passive structure of PAs, as described previously (7, 8, 20, 21). The brain was collected at euthanasia and was placed in a cooled (4°C) dissection chamber in calcium-free physiological salt solution (PSS) containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2·7H2O, 10 HEPES, and 10 dextrose with pH adjusted to 7.4. To isolate PAs, a 5 × 3-mm section of the brain containing the middle cerebral artery (MCA) was dissected. The pia with the MCA was separated from the brain, and the PAs branching off the MCA were used for experiments. Isolated arterioles were cannulated with two glass micropipettes in a custom-made cannulation chamber. Arterioles were equilibrated at 37°C in artificial cerebral spinal fluid containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 4 glucose. A servo-controlled system was used to pressurize the arterioles (Living Systems, St. Albans City, VT). A leak test was performed before each experiment, and any arteriole that did not maintain its intraluminal pressure was discarded. Arterioles were pressurized to 40 mmHg until the development of stable myogenic tone: percent tone = [1 – (active lumen diameter/passive lumen diameter)] × 100. Arterioles that generated at least 20% myogenic tone were used for experiments. Arterioles that did not develop myogenic tone were discarded. The diameter of the arterioles was tracked using MyoView 2.0 software (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark).

Endothelial Function

After myogenic tone generation, endothelium-dependent dilation was assessed. To measure TRPV4-mediated dilation, increasing concentrations of the specific TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A (10−9–10−5 M) were added to the bath. To assess IKCa/SKCa-mediated dilation, PAs were incubated with increasing concentrations of the agonist NS309 (10−9–10−5 M). A subset of arterioles was incubated with NS309, as well as either triarylmethane-34 (TRAM34; 1 µM) or apamin (300 nM), to determine the role of IKCa and SKCa channels individually. TRAM34 or apamin were added after the generation of myogenic tone and circulated through the system for 10 min before assessing NS309 (1 µM)-mediated dilation. Neither antagonist altered the amount of tone generated. Each PA was used for only one dilation experiment.

Passive PA Structure

After completion of endothelial function experiments, arterioles were incubated with calcium-free PSS containing ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA; 29 mM) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10−5 M). To assess the structure of the arterioles, a pressure-diameter curve was constructed by increasing the intraluminal pressure from 3 to 120 mmHg at 20-mmHg increments. The arterioles were equilibrated at each pressure for 5 min, and the lumen and outer diameters were measured. These values were used to calculate wall thickness (outer diameter – lumen diameter), wall stress, strain, and distensibility, as described (22). Wall stiffness was quantified using the β-coefficient calculated from the individual stress-strain curves using the model y = aeβx, where y is wall stress, x is wall strain, a is the intercept, and β is the slope of the exponential fit; a higher β-coefficient represents a stiffer vessel.

Spontaneous Alternation

Spatial working memory was assessed using a Y-maze spontaneous alternation task. A custom Y-maze was constructed courtesy of Dr. Nathan Tykocki (Michigan State University). The maze consists of three arms placed at a 120° angle from one another. Each arm is 35 cm long, 5 cm wide, and 20 cm high. Mice were each placed at the end of a random arm of the maze and allowed to explore freely for 3 min. A mouse with intact memory will preferentially visit the arm it has visited the least recently, and a correct alternation is defined as consecutive entries into all three arms (23). Percent alternation was calculated as follows:

Barnes Maze

A Barnes maze was used to assess spatial memory (8, 24). Mice were trained over the course of 4 days (three 3-min trials) to locate the escape hole. Visual cues were placed on each wall to aid in spatial orientation. A 4,000-Hz sound acted as an aversive stimulus, which was removed when the mice climbed into the escape hole. Mice were left in the escape box for 1 min before being returned to their home cages. On the fifth day, the escape hole was covered but left in the same location, and the movement of the mice was tracked for 90 s using EthoVision XT (25). The amount of time mice spent exploring the holes of the quadrant of the maze containing the escape hole was measured.

Immunofluorescence

Brains were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stored in sucrose. Coronal cryosections (40 µm thickness) were obtained at the level of the hippocampus approximately 2 mm from bregma. To assess microglia quantification and morphology, free-floating sections were blocked and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 with 10% donkey serum-PBS for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated in 1:200 rabbit anti-ionized Ca2+-binding adapter molecule 1 diluted in blocking solution (Iba-1; Cat. No. PA5-27436, RRID: AB_2544912, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) overnight at 4°C. After being washed 4× in PBS (10 min each wash), sections were incubated in 1:500 secondary AlexaFluor 568 goat anti-rabbit antibody in PBS (Cat. No. A11011, RRID: AB_143157, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 1 h. Sections were washed 4× in PBS (10 min each wash) and were then mounted with coverslips using Prolong antifade reagent (Cat. No. P36931, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Images were obtained from the CA1 region of the hippocampus and of the region of the cortex immediately dorsal to this in each hemisphere (two images per mouse). Six brain sections were stained for each group. To assess microglial quantity, the final data point per mouse is the average of the data from the two hemispheres. To acquire data for soma size, regions of interest were drawn around 10 random microglia in the image using FIJI software (ImageJ, v. 1.53t), and the area was measured. The final data point per animal comprises the average of the soma sizes from these microglia.

To assess the quantity and morphology of astrocytes, 40-µm brain sections, at the same level of the hippocampus as described above, were blocked and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 with 10% horse serum-PBS for 30 min at room temperature, then incubated in 1:1,000 rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Cat. No. ab7260, RRID: AB_305808, Abcam, Waltham, MA) overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed three times in PBS (10 min for each wash) and then incubated in 1:500 secondary AlexaFluor 568 goat anti-rabbit antibody in PBS. Sections were washed in PBS as described above and mounted with coverslips using Prolong antifade reagent. Images were obtained from the corpus callosum in both hemispheres of each sample. Six brain sections were stained for each group. For astrocytic quantity, the final data point per mouse is the average of the data from the two hemispheres.

All images were acquired using a Plan-Apochromat ×20 objective (numerical aperture. 0.8) coupled to a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope with a 561 nm excitation laser. Z-stack (8-bit, unidirectional scanning, averaging of 2) images were taken through the entire thickness of each 40-µm section and then compressed into maximum intensity projections in FIJI software. Acquisition parameters were kept consistent between images. Sections without primary antibodies served as negative controls. The colors of the representative images were changed to green in FIJI so they could be easily visualized in print. All quantifications were done manually by a blinded investigator using FIJI.

Sholl Analysis

A Sholl analysis was used to assess microglia and astrocyte structure, as described by others (26). In brief, the Simple Neurite Tracer plugin in FIJI was used to manually trace five random microglia and astrocytes from each subject. With these tracings, the average branch length was measured using the plugin software. The number of branches of each cell was manually counted. The tracings were then skeletonized, and the automated Sholl analysis was used to draw concentric circles away from the soma around the cell. The number of intersections of the cell processes at increasing distances from the center was recorded using a step size of 1 µm. The data collected for every five cells were averaged to acquire the final data point for each mouse. The number of intersections of the microglial or astrocytic processes at these circles was plotted against the distance of the circle from the soma.

Drugs and Chemicals

Unless otherwise specified, all drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Agonists and antagonists for endothelial function experiments were diluted in DMSO and added to the circulating artificial cerebral spinal fluid.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. For analysis of arteriole structure, vasodilation, and the Sholl analysis for microglia and astrocytes, two-way ANOVA with repeated measures in one factor (pressure, concentration, or distance from soma) was used, followed by Bonferroni-adjusted t tests for post hoc comparisons. All other statistical analyses were assessed by two-tailed Student’s t test for male comparisons, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for female comparisons, or their nonparametric counterparts if the data did not follow a normal distribution (Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis). Comparisons were made between the ANG II-treated groups and their sham-operated controls within the same sex. Any comparisons between sexes were noted in the text. Data points that were two standard deviations away from the mean were considered outliers (27, 28); if the presence of the outlier did not change the outcome of the analysis, they were kept in the data set. Any removed outlier was noted in the figure or table legend. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). In all cases, statistical significance was denoted by P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Female Mice Require a Higher Dose of ANG II to Elevate Systolic Blood Pressure

ANG II was delivered to male and female mice via subcutaneous implantation of osmotic minipumps. Male mice given 800 ng/kg/min ANG II for 4 wk had significantly elevated systolic blood pressure compared with sham mice (133.0 ± 10.0 vs. 178.8 ± 11.7 mmHg, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.0101, Fig. 1A). Female mice were given 800 ng/kg/min ANG II and did not have a detectable elevation in systolic blood pressure compared with sham mice (149.5 ± 4.0 vs. 161.3 ± 12.6, control vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II, P = 0.6484, Fig. 1B). This resistance to ANG II hypertension in cycling female mice has been demonstrated by others (17). Systolic blood pressure was significantly elevated in female mice given 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II compared with shams (149.5 ± 4.0 vs. 183.1 ± 5.5 mmHg, P = 0.0184, Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Female mice require a higher dose of angiotensin II (ANG II) than male mice to elevate blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured in conscious mice using tail-cuff plethysmography. A: systolic blood pressure was significantly elevated in male mice infused with 800 ng/kg/min ANG II compared with shams. ANG II vs. sham comparisons made by two-tailed Student’s t test. B: in female mice, 800 ng/kg/min ANG II did not significantly elevate systolic blood pressure. Female mice given 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II had a significant increase in blood pressure compared with shams. ANG II (800 ng) or ANG II (1,200 ng) vs. sham comparisons were made by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 8 per group.

ANG II Infusion Reduces Pial Blood Flow in Both Male and Female Mice

Laser speckle contrast imaging was used to assess cerebral pial blood flow in anesthetized mice. Brain regions of interest were specified in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortex, as described by others (19, 29). These regions were chosen because they are perfused by the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries, respectively. ANG II-infused male mice had reduced pial blood flow in the parietal region (346.1 ± 13.3 vs. 297.2 ± 8.4, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.0051, Fig. 2B). In contrast, blood flow in the frontal (346.4 ± 12.4 vs. 320.0 ± 9.2, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.1011, Fig. 2D) and temporal regions (290.4 ± 8.5 vs. 272.1 ± 9.4, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.1620, Fig. 2F) did not exhibit detectable changes compared with sham mice. Both doses of ANG II-infused female mice, however, had reduced pial blood flow in all measured regions compared with sham mice [parietal: 396.8 ± 8.4 vs. 330.3 ± 15.6 vs. 335.2 ± 17, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0053) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0084), Fig. 2C; frontal: 359.0 ± 9.0 vs. 306.0 ± 12.1 vs. 301.9 ± 14.3, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0086) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0039), Fig. 2E; temporal: 331.9 ± 8.3 vs. 271.7 ± 11.3 vs. 276.2 ± 13.6, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0016) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0028), Fig. 2G].

Figure 2.

Angiotensin II (ANG II)-hypertension reduces pial perfusion in both male and female mice. Pial perfusion was measured in anesthetized mice using laser speckle contrast imaging. A: representative images of regions of interest (top), pial perfusion in male (bottom, left) and female (bottom, right) mice. The perfusion scale bar ranges from 0 to 500 arbitrary perfusion units. B: ANG II infusion in male mice reduces cerebral pial perfusion compared with shams in the parietal region, but not frontal (D) or temporal regions (F). ANG II vs. sham comparisons made by two-tailed Student’s t test. C: ANG II infusion in female mice reduces cerebral pial perfusion compared with shams in the parietal region, the frontal region (E), and the temporal region (G). ANG II (800 ng/kg/min) and ANG II (1,200 ng/kg/min) vs. sham comparisons made by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 12 (males) and 12–13 (females).

Myogenic Tone Generation Is Elevated in PAs of ANG II-Infused Male Mice

Myogenic tone generation was measured in isolated PAs using pressure myography. PAs were pressurized to 40 mmHg until the generation of spontaneous myogenic tone. Myogenic tone increases in hypertension; we have shown this using various models of hypertension, including ANG II infusion (8, 21). In the present study, myogenic tone generation was elevated in PAs from ANG II-infused male mice compared with PAs from sex-matched sham controls (26.5 ± 1.0 vs. 32.1 ± 2.2%, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.0248, Fig. 3A). PAs from ANG II-infused female mice did not exhibit altered tone generation compared with the control mice [24.5 ± 0.9 vs. 28.6 ± 1.9 vs. 27.9 ± 1.6%, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.1279) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.2449), Fig. 3B]. There were no detectable sex differences in the amount of myogenic tone generated in PAs from sham mice (26.5 ± 1.0 vs. 24.5 ± 0.9, male shams vs. female shams, P = 0.1413 by two-tailed Student’s t test).

Figure 3.

Angiotensin II (ANG II) hypertension increases myogenic tone generation in parenchymal arterioles (PAs) of male mice. Myogenic tone generation in PAs was measured using pressure myography. A: PAs from ANG II hypertensive male mice generated more myogenic tone compared with shams. ANG II vs. sham comparisons made by two-tailed Student’s t test; n = 23–24 PAs from 16–17 male mice, using 1–3 PAs per mouse. B: in female mice, PA myogenic tone generation was not significantly altered after ANG II infusion compared with shams. ANG II (800 ng/kg/min) and ANG II (1,200 ng/kg/min) vs. sham comparisons made by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons; n = 24–25 PAs from 14–17 female mice, using 1–3 PAs per mouse. Myogenic tone values were collected before the start of each dilation experiment. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE.

ANG II Infusion Impairs TRPV4-Mediated Dilation in PAs of Male Mice Only

After the generation of myogenic tone, we used the specific TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A to measure TRPV4-mediated dilation in PAs. We have demonstrated that PAs from ANG II hypertensive male mice have impaired TRPV4-mediated dilation (8). These findings were reproduced in the present study. PAs from ANG II-infused male mice had significantly blunted TRPV4-mediated dilation compared with shams (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0163; maximum dilation: 82.1 ± 4.9 vs. 49.6 ± 7.4%, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.0046 by two-tailed Student’s t test; −logEC50 = 7.14 [7.46, 6.81, 95% CI] shams, 7.33 [8.34, 6.08, 95% CI] ANG II; Fig. 4A). PAs from ANG II-infused female mice did not exhibit impaired TRPV4-mediated dilation in either treatment group compared with the sham mice. Here, the two-way ANOVAtreatment P value reached significance, indicating ANG II treatment influenced dilation. However, maximum dilation produced in response to TRPV4 activation was unchanged after ANG II infusion [maximum dilation: 86.3 ± 4.5 vs. 72.5 ± 7.2 vs. 75.6 ± 5.1%, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.2184) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.3836) by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction; −logEC50 = 6.79 [7.03, 6.55, 95% CI] shams, 6.86 [7.26, 6.28, 95% CI] 800 ng/kg/min ANG II, 6.54 [7.03, 5.97, 95% CI] 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II; Fig. 4B]. Dilation comparisons at individual concentrations were not statistically significant. These data demonstrate that hypertension-induced impairment of TRPV4-mediated dilation in PAs is sex dependent.

Figure 4.

Angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion impairs TRPV4-mediated dilation in parenchymal arterioles (PAs) from male mice only. Pressure myography was used to assess transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4)- and intermediate and small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (IKCa/SKCa)-mediated dilation in PAs. A: ANG II-infused male mice had impaired PA TRPV4-mediated dilation compared with shams after incubation with increasing concentrations of the TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A in the superfusing bath. B: ANG II-infused female mice did not have impaired TRPV4-mediated dilation in PAs compared with shams. C: ANG II-infused male mice did not have impaired PA IKCa/SKCa-mediated dilation, assessed by incubation with increasing concentrations of agonist NS309 in the superfusing bath. D: ANG II-infused female mice did not have impaired IKCa/SKCa-mediated dilation. *P < 0.05, ANG II (male) or 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (female) vs. shams. All comparisons made vs. shams by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6–7 PAs (males) and 6–8 PAs (females); 1 PA per mouse.

IKCa/SKCa-Mediated Dilation in PAs Is Unaltered in ANG II-Infused Mice

TRPV4 activation produces a calcium influx that activates nearby IKCa/SKCa channels to produce EDH and vasodilation (30). To determine whether impaired PA dilation was at the level of TRPV4 or at downstream IKCa/SKCa channels, PA dilation to agonist NS309 was evaluated. Our data in this study disagree with our previous finding that ANG II-infused male mice have impaired IKCa/SKCa-mediated dilation in PAs compared with the shams. Here, ANG II-infused male mice had no detectable changes in dilation to NS309 compared with shams (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.7584; maximum dilation: 95.9 ± 1.3 vs. 93.0 ± 1.5%, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.1733 by two-tailed Student’s t test, −logEC50 = 7.06 [7.25, 6.87, 95% CI] shams, 7.23 [7.56, 6.92, 95% CI] ANG II; Fig. 4C). In female mice, there was a detectable effect of ANG II infusion on dilation to NS309 compared with shams, though there were no differences detected in maximum dilation [two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0460; maximum dilation: 92.2 ± 3.0 vs. 87.2 ± 3.1 vs. 93.9 ± 2.0%, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.4252) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P > 0.9999) by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction; −logEC50 = 6.65 [7.08, 6.20, 95% CI] shams, 6.26 [6.45, 6.08, 95% CI] 800 ng/kg/min ANG II, 6.91 [7.14, 6.67, 95% CI] 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II; Fig. 4D]. Notably, female mice treated with 800 ng/kg/min ANG II had significantly less PA dilation to 10−7 M NS309 than shams (P = 0.0344 by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons).

NS309 activates both IKCa/SKCa channels. We previously reported that ANG II-infused male mice have reduced mRNA expression of SKCa and increased mRNA expression of IKCa in cerebral arteries compared with shams. To determine whether ANG II infusion alters the dilatory contribution of these channels compared with the shams, we used IKCa antagonist TRAM34 and SKCa antagonist apamin to separate dilatory contribution through these two channels. Antagonists were added to the superfusing bath after the generation of myogenic tone. A typical PA dilation for control mice of each sex to 1 µM NS309 is noted by the dotted line across the y-axes on the graphs. In the presence of apamin in male and female mice, ANG II infusion did not alter PA dilation to 1 µM NS309 compared with shams [male: 86.8 ± 3.1 vs. 86.8 ± 3.2%, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.9899, Fig. 5A; female: 86.3 ± 3.5 vs. 80.2 ± 4.4 vs. 71.3 ± 12.4%, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P > 0.9999) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.4015), Fig. 5C]. Similarly, in both sexes, ANG II infusion did not alter NS309-mediated dilation in the presence of TRAM34 [male: −5.7 ± 8.9 vs. 8.9 ± 9.0%, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.2840, Fig. 5B; female: 6.2 ± 8.8 vs. 20.3 ± 6.3 vs. 26.3 ± 10.4%, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.5390) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.2463), Fig. 5D].

Figure 5.

Hypertension does not alter intermediate and small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (IKCa/SKCa) channel contribution in male or female parenchymal arterioles (PAs). Pressure myography was used to assess the dilatory contribution of IKCa and SKCa channels in PAs using antagonists triarylmethane-34 (TRAM34; 1 µM) and apamin (300 nM), respectively, alongside mutual channel agonist NS309 (1 µM). The dotted lines on each graph represent the average dilation of the sham group of each sex to 1 µM NS309. A: angiotensin II (ANG II)-infused male mice did not have detectable changes in dilation to 1 µM NS309 when the SKCa antagonist apamin. B: IKCa antagonist TRAM34 was in the superfusing bath compared with shams. Comparisons made vs. shams by two-tailed Student’s t test. C: ANG II treatment in female mice did not significantly alter dilation to 1 µM NS309 when apamin. D: TRAM34 was in the superfusing bath compared with shams. ANG II (800 ng/kg/min) and ANG II (1,200 ng/kg/min) vs. sham comparisons made by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 5–6 PAs of each sex; 1 PA per mouse.

ANG II Infusion Results in Inward Hypotrophic Remodeling in PAs of Both Male and Female Mice

Pressure myography was used to assess passive PA structure under zero flow and calcium-free conditions. Reproducing findings from our laboratory, PAs from ANG II-infused male mice underwent inward hypotrophic remodeling compared with PAs from sham mice (7). This was characterized by a reduction of outer (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0243, Fig. 6A) and lumen diameters (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0422, Fig. 6B) and a reduction in wall thickness (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0379, Fig. 6C). PAs from ANG II-infused female mice underwent a reduction in outer diameter (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0796; P < 0.05 at pressures 20 mmHg and above in 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II group vs. shams after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, Fig. 6D), with no significant changes in lumen diameter (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.1509). The female mice receiving 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II also had PAs with reduced wall thickness, mimicking what is observed in ANG II-infused male mice (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.0094; P < 0.05 at all individual pressures, Fig. 6F). Biomechanical properties of PAs in both male and female mice were unchanged in response to ANG II (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Angiotensin II (ANG II)-infused male and female mice had inward hypotrophic remodeling in parenchymal arterioles (PAs). The structure of PAs from male and female mice was assessed under zero-calcium conditions by pressure myography. In male mice, ANG II infusion resulted in PAs with reduced outer diameter (A), lumen diameter (B), and wall thickness (C) compared with shams. 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II infusion in female mice resulted in PAs with reduced outer diameter (D) and reduced wall thickness (F), with no statistically significant changes in lumen diameter (E). *P < 0.05, ANG II (males) or 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (females) vs. shams. All comparisons made vs. shams by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 7–8 PAs (males) and 8–9 PAs (females); 1 PA per mouse.

Table 1.

Effect of ANG II infusion on biomechanical properties of parenchymal arterioles

| Male |

Female |

Female |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | ANG II | P Value | Sham | 800 ng/kg/min ANG II | P Value | 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II | P Value | |

| Wall stress, dyn/cm2 | 229.6 ± 21.4 | 274.2 ± 24.1 | 0.20 | 260.6 ± 12.9 | 267.4 ± 30.2 | >0.99 | 273.0 ± 16.9 | >0.99 |

| Wall strain | 0.195 ± 0.02 | 0.174 ± 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.202 ± 0.01 | 0.210 ± 0.02 | >0.99 | 0.178 ± 0.02 | 0.50 |

| Distensibility | 19.5 ± 1.5 | 17.4 ± 2.2 | 0.47 | 20.21 ± 1.2 | 21.0 ± 1.7 | >0.99 | 17.8 ± 1.5 | 0.50 |

| β-Coefficient | 12.2 ± 0.9 | 13.8 ± 1.1 | 0.31 | 13.0 ± 0.75 | 11.9 ± 0.88 | 0.49 | 12.6 ± 0.50 | 0.92 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 7–9. ANG II, angiotensin II. Comparisons made vs. same-sex sham controls at 40 mmHg by two-tailed Student’s t test (males) or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction (females).

ANG II Infusion Impairs Cognitive Function in Male Mice Only

Impaired TRPV4 function is associated with cognitive impairment, even in the absence of hypertension (8, 9, 31). To determine whether the observed sex differences in TRPV4 function were associated with sex differences in cognition, we used two memory tasks. We measured spatial working memory using the spontaneous alternation task in a Y-maze. ANG II-infused male mice made fewer correct alternations than sham mice, indicating impairments in spatial working memory (66.0 ± 2.5 vs. 52.7 ± 4.7% correct alternations, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.0205, Fig. 7B). ANG II-infused female mice did not exhibit differences in spontaneous alternation behavior compared with sham mice [55.4 ± 3.0 vs. 51.7 ± 5.5 vs. 46.9 ± 3.6% correct alternations, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P > 0.9999) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.3172), Fig. 7C]. ANG II-infused male and female mice had similar total arm entries to their respective sham controls [male: 16 ± 1 vs. 15 ± 1, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.5693, Fig. 7D; female: 21 ± 2 vs. 21 ± 1 vs. 20 ± 1, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P > 0.9999) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P > 0.9999), Fig. 7E].

Figure 7.

Angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion impairs cognitive function in male but not female mice. Spatial working memory was assessed using the spontaneous alternation task. A: schematic of the Y-maze with a representation of a correct alternation. B: male ANG II-infused mice had impaired alternation behavior compared with shams. D: with no detectable differences in the total arm entries. C and E: ANG II-infused female mice did not exhibit differences in spontaneous alternation behavior (C) or in total arm entries (E). Spatial memory was assessed using Barnes maze. F: schematic of a Barnes maze, with the escape hole marked by the filled circle. G: ANG II-infused male mice spent significantly less time exploring the quadrant of the maze containing the escape hole compared with shams. H: female ANG II-infused mice did not have detectable differences in the amount of time spent investigating the quadrant of the Barnes maze containing the escape hole. Comparisons made vs. shams by two-tailed Student’s t test (males) or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons (females). Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 10–11 (males) and 12 (females).

We then used the Barnes maze test to assess spatial memory. The maze was divided into quadrants; the quadrant containing the escape hole was named the target quadrant. Reproducing our previous findings, ANG II-infused male mice spent significantly less time exploring holes in the maze’s target quadrant than the sham mice, indicating deficits in spatial memory (84.0 ± 2.4 vs. 74.4 ± 3.7% time, control vs. ANG II, P = 0.0385, Fig. 7G). ANG II-infused female mice did not exhibit differences in the amount of time exploring holes in the target quadrant, indicating intact spatial memory [64.1 ± 4.2 vs. 75.8 ± 3.4 vs. 70.7 ± 3.3% time, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0624) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.4289), Fig. 7H]. These data demonstrate an important sexual dimorphism in hypertension: impaired TRPV4 function in PAs is associated with impaired cognitive function in ANG II-infused male mice. In contrast, maintenance of TRPV4 function is associated with intact cognition in female mice.

ANG II Infusion Increases Neuroinflammation in Male Mice

The quantity and morphology of cortical and hippocampal microglia were assessed using an Iba-1 antibody. Data are summarized in detail in Table 2. ANG II-infused male mice had more microglia in the cortex and hippocampus than the sham mice. Cortical microglia from ANG II-infused male mice had more branches and a shorter average branch length than those in the sham group, with no detectable increase in cell soma size. Hippocampal microglia from ANG II-infused male mice had significantly increased soma size and more branches than sham mice. Branch complexity, however, was not significantly different in microglia of ANG II-treated male mice compared with shams, assessed by Sholl analysis (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.6720 in the cortex, Fig. 8B; P = 0.1752 in the hippocampus, Fig. 8C). In female mice, ANG II infusion did not affect microglia quantity in the cortex but resulted in an unexpected trend toward fewer microglia in the hippocampus in mice given 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II compared with shams. Female mice also had microglia with greater soma sizes in both the cortex and the hippocampus after ANG II infusion compared with shams. Contrasting with ANG II-infused male mice, female mice did not have significant alterations in the number of branches compared with shams in either brain region after ANG II treatment. They did have a significant increase in average branch length in cortical microglia in those treated with 800 ng/kg/min ANG II. There were no significant differences in the branching complexity of microglia after ANG II infusion in female mice, assessed by Sholl analysis (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.6099 in the cortex, Fig. 8D; P = 0.2383 in the hippocampus, Fig. 8E). Notably, at baseline, sham female mice had more cortical microglia than sham male mice and trended toward a greater amount of hippocampal microglia compared with males (43 ± 2 vs. 50 ± 1 cortical microglia, sham male vs. sham female, P = 0.0121 by two-tailed Student’s t test; 46 ± 1 vs. 54 ± 5 hippocampal microglia, sham male vs. sham female, P = 0.0815 by two-tailed Student’s t test). Together, these data suggest that microglia from male, but not female mice switch to their proinflammatory phenotype after ANG II infusion.

Table 2.

Microglia morphology assessment

| Male |

Female |

Female |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | ANG II | P Value | Sham | 800 ng/kg/min ANG II | P Value | 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II | P Value | |

| Microglia, n | ||||||||

| Cortex | 43 ± 2 | 51 ± 3 | 0.04* | 50 ± 1 | 50 ± 2 | >0.99 | 48 ± 3 | 0.88 |

| Hippocampus | 46 ± 1 | 54 ± 2 | 0.01* | 54 ± 5 | 47 ± 1 | 0.48b | 46 ± 2 | 0.08b |

| Soma size, µm2 | ||||||||

| Cortex | 50 ± 3 | 56 ± 1 | 0.13b | 41 ± 1 | 45 ± 3 | 0.45 | 51 ± 3 | 0.02* |

| Hippocampus | 46 ± 3 | 53 ± 1 | 0.05* | 40 ± 2 | 54 ± 4 | 0.05*,b | 58 ± 1 | 0.01*,b |

| Branches, n | ||||||||

| Cortex | 9 ± 0.2 | 10 ± 0.5 | 0.02* | 9 ± 0.5 | 8 ± 0.7 | 0.59 | 9 + 0.5 | >0.99 |

| Hippocampus | 9 ± 0.7 | 11 ± 0.9 | 0.05* | 9 ± 0.6 | 9 ± 0.5 | 0.77 | 9 ± 0.4 | 0.72 |

| Mean branch length, µm | ||||||||

| Cortex | 13 ± 0.6 | 12 ± 0.4 | 0.02* | 12 ± 0.4a | 14 ± 0.5 | 0.02* | 13 ± 0.4 | 0.99 |

| Hippocampus | 12 ± 0.5 | 11 ± 0.6 | 0.32 | 13 ± 0.8 | 11 ± 0.4 | 0.17 | 13 ± 0.8 | >0.99 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 or an = 5 because of the removal of an outlier (25.3 µm). *P < 0.05 vs. same-sex sham controls by two-tailed Student’s t test (male) or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction (female) or by bMann–Whitney (male) or Kruskal–Wallis (female).

Figure 8.

Angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion does not alter microglial process complexity. Microglial process complexity was assessed in ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba-1) stained coronal brain sections using the Sholl analysis. A: representative images of Iba-1 staining in the cortex (Cx) and hippocampus (Hp) of male and female mice. B and C: ANG II infusion in male mice did not significantly alter microglial process complexity in the cortex (B) or hippocampus compared with sham mice (C). ANG II infusion in female mice did not significantly alter microglial process complexity in the cortex (D) or hippocampus compared with shams (E). All comparisons made vs. shams by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. Scale bar = 100 µm.

ANG II Infusion Produces Reactive Astrogliosis in Male Mice, but Not Female Mice

We used a GFAP antibody to assess astrocytic quantity and structure. ANG II-hypertensive male mice had more astrocytes than shams (64.8 ± 1.7 vs. 76.8 ± 4.7, shams vs. ANG II, P = 0.0390, Fig. 9B). The morphology of astrocytes was assessed using a Sholl analysis. Hypertensive male mice had astrocytes with more arborization at points further away from the soma than the shams (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.2734, P < 0.05 at 14–15 µm from the soma after multiple comparisons with Bonferroni post hoc correction, Fig. 9D). The observed elevation in astrocyte quantity and increased process complexity are indicators of reactive astrogliosis (32, 33). ANG II-infused female mice had a reduction in astrocyte quantity compared with shams [81.4 ± 2.7 vs. 71.0 ± 2.9 vs. 68.7 ± 2.7, shams vs. 800 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0338) and 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II (P = 0.0100), Fig. 9C]. Like microglia, sham female mice had more astrocytes at baseline compared with sham male mice (64.8 ± 1.7 vs. 81.4 ± 2.7, male vs. female, P = 0.0004 by two-tailed Student’s t test). Contrasting with the observations in ANG II-infused male mice, astrocytes in the female group receiving 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II had significantly reduced process arborization compared with shams (two-way ANOVAtreatment, P = 0.3340, P < 0.05 at 12–14 µm from the soma after multiple comparisons with Bonferroni post hoc correction, Fig. 9E). These data indicate a sexual dimorphism in the inflammatory response to ANG II infusion, with only male mice exhibiting signs of reactive astrogliosis.

Figure 9.

Angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion results in reactive astrogliosis in male, but not female mice. The number of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes and their morphology were assessed in the corpus collosum. A: representative images of GFAP staining in male (top) and female mice (bottom). B: ANG II-hypertensive male mice had increased astrocytes compared with shams. ANG II vs. sham comparisons made by two-tailed Student’s t test. C: ANG II-infused female mice had fewer astrocytes compared with shams. ANG II (800 ng/kg/min) and ANG II (1,200 ng/kg/min) vs. sham comparisons made by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. D: astrocytes from ANG II-infused male mice had more arborization away from the soma compared with shams, assessed by Sholl analysis. E: astrocytes from 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II-infused female mice had reduced arborization compared with shams. Sholl analyses assessed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05 at individual distances from the soma. Males, closed data points; females, open data points. All data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. Scale bar = 100 µm.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine how biological sex influences the impact of hypertension on cerebrovascular health. This study provides novel evidence that cycling female mice are protected from impaired PA TRPV4-mediated dilation and associated cognitive decline during hypertension. Furthermore, the data suggest a sex-dependent difference in inflammation that may mediate or be the result of vascular and cognitive changes. These data expand our knowledge of sex differences in cerebrovascular physiology, a subject that has received very little study. Understanding sex differences in young mice is an essential first step in elucidating sex differences that arise later in life. Furthermore, our observations expand on our previous findings that hypertension-associated cognitive impairment is associated with dysfunctional arteriolar TRPV4 signaling.

Our data agree with studies by Xue et al. (17) demonstrating that female mice require a higher dose of ANG II to become hypertensive and follow-up studies showed the observed resistance to hypertension is estrogen dependent (34). We identified a dose of ANG II that overcomes the estrogen-mediated protection against hypertension. Female mice given 1,200 ng/kg/min ANG II developed hypertension, although the magnitude of the blood pressure increase (22%) was less than that in male mice treated with 800 ng/kg/min (34%). This difference in the magnitude of the blood pressure elevation may be explained by sham female mice having a higher baseline systolic blood pressure than sham male mice. Blood pressures were measured using tail-cuff plethysmography, and both sexes were acclimated to the procedure similarly. Because females have a greater physiological response to acute stressors (35), the higher baseline blood pressure in female mice is not surprising. Future studies can use radiotelemetry for blood pressure measurement to mitigate stress-induced pressor effects.

In our vasodilation studies, we focused on the effects of TRPV4 because we have shown that this cation channel is the primary contributor to endothelium-dependent dilation in PAs (8, 9, 31). In mesenteric arteries and cerebral PAs, TRPV4 channels are dysfunctional in hypertensive male rodents (8, 31, 36). Here, we have shown that the hypertension-induced impairment of TRPV4-mediated dilation in PAs is sex dependent and occurs in males only. It is well established that female sex conserves endothelial function in pathological conditions through increased NO production and maintained endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity (37, 38). Our novel data suggest female sex protects against endothelial dysfunction via mechanisms that extend beyond NO-mediated pathways.

TRPV4 channels are expressed in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. In endothelial cells, TRPV4 channels in the myoendothelial projections (MEPs) produce a calcium influx upon activation that ultimately produces EDH via subsequent IKCa/SKCa channel activation. TRPV4 activity is enhanced by A-kinase anchoring protein 150 (AKAP150), which anchors protein kinase A and protein kinase C to MEPs to facilitate TRPV4 phosphorylation (36, 39, 40). In response to the calcium influx through endothelial TRPV4 channels, IKCa/SKCa channel activation produces a potassium ion efflux, hyperpolarizing the cell. This hyperpolarization crosses to vascular smooth muscle cells through myoendothelial gap junctions, causing vasodilation. NS309 activates both IKCa and SKCa channels. ANG II hypertensive male mice have increased IKCa and reduced SKCa mRNA expression in cerebral arteries, suggesting renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activation influences the transcription of these ion channels (8). To determine whether hypertension alters ion channel contribution to EDH, we used the antagonists TRAM34 and apamin to block IKCa and SKCa channels, respectively. Consistent with findings by Cipolla et al. (41), we observed that IKCa channels are the primary contributor to EDH in PAs in both sexes. Our data suggest that ANG II infusion does not result in altered ion channel contribution to EDH. We previously reported that hypertensive male mice had impaired IKCa/SKCa-mediated dilation in PAs, which contradicts our present findings (8). This disagreement was unexpected. Mice from our previous study were provided to us by a collaborator, whereas mice from the present study were purchased from Charles River. It is possible that differences in the environmental background of the mice may contribute to our observations. However, further research will be necessary to determine the reasons behind these disparate findings.

Myogenic reactivity plays a critical role in cerebral blood flow regulation, especially in Pas, which generate high levels of myogenic tone relative to larger arteries. There are limited data comparing myogenic tone generation in Pas between the sexes. However, it has been reported that MCAs of female rats generate more myogenic tone than MCAs of male rats, potentially because of smaller artery size (42, 43). Our data suggest that sex does not significantly impact myogenic tone generation in the PAs of sham mice. The small size of these arterioles means it is possible that small changes in myogenic tone were below the detection limit. Notably, hypertension resulted in more myogenic tone generation in PAs of male mice only, indicating female sex protects against this elevated tone generation in response to increased blood pressure.

There is ample evidence that RAS activity is directly linked to structural changes observed in the vasculature in hypertension. Angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1R) activation leads to the remodeling of vascular smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix proteins, ultimately producing changes in arterial structure (44–46). In both peripheral and large cerebral arteries, hypertension induces inward hypertrophic remodeling, characterized by a smaller lumen diameter and thickening of the artery wall (47–49). PAs from hypertensive rodents, however, undergo inward hypotrophic remodeling, characterized instead by a reduction in wall thickness (7, 21). In the present study, male and female hypertensive mice exhibited inward hypotrophic remodeling, though changes in female mice were smaller. ANG II-infused female mice had a dose-dependent reduction in PA diameter and wall thickness that reached significance in the hypertensive group only. Increased angiotensin II receptor type 2 (AT2R)/Mas receptor expression in female mice may contribute to this apparent resistance. In addition, our group found that in ANG II hypertensive male mice, PA remodeling is mediated by endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor activation (7). Although there are sex differences in mineralocorticoid receptor activation in cardiovascular disease (50), the mechanisms involved in cerebral microvessels are thus far unknown.

Hypertension reduces cerebral blood flow (51–53) and inadequate cerebral perfusion increases the risk of dementia development (54, 55). Using scanning laser Doppler flowmetry, we showed that male ANG II hypertensive mice have reduced cerebral pial artery perfusion (7). Here, we used laser speckle contrast imaging to determine sex differences in cerebral pial perfusion in response to hypertension. There was an unexpected finding that ANG II-infused female mice exhibited global reductions in cerebral blood flow while hypertensive male mice had reductions only in the parietal region. Blood flow reduction in female mice was comparable between the 800 ng/kg/min and the 1,200 ng/kg/min groups, suggesting this effect is blood pressure independent. Differences in cerebral blood flow may be attributable to sex-dependent variances in myogenic reactivity in pial arteries. Others have demonstrated that although MCAs of 3-mo-old female rats have greater basal myogenic tone than males, they are also more susceptible to force-mediated dilation at high intraluminal pressures (56). This concept contradicts our observations, though the differences in species, subject age, and vessel type complicate direct comparisons. Another possibility is a difference in the direct constrictor effects of ANG II. Pial arteries are particularly susceptible to ANG II-induced constriction (57). AT1Rs are quickly internalized after activation (58–60), and greater blood flow reduction in female mice presents the possibility of a lessened tachyphylactic response of AT1R after activation. A recent study by Zaccor et al. (61) presented an interesting concept that TRPV4 activation prevents AT1R internalization, which could explain the globally reduced pial blood flow in female mice. Additional studies will be required to test directly test this hypothesis.

Our group has reliably found across various models that impaired TRPV4 channel activity is associated with cognitive dysfunction (8–10, 31). Here, we present novel data that the maintenance of TRPV4-mediated signaling in PAs of female mice is associated with protection against cognitive impairment in hypertension. Notably, in both behavioral tests, sham male mice outperformed sham female mice. This is expected, as studies reliably report better performance in spatial tasks in male compared with female rodents (62–65). The maintenance of cognitive function in ANG II-infused female mice is interesting considering their global reduction in pial blood flow. Together, these observations present the possibility that neurons from female mice are protected from the adverse effects of reduced cerebral blood flow. In primary neuron cultures and in vivo stroke studies, neurons from female rats have better survival than neurons from male rats, suggesting greater resilience to low oxygen environments (66–68). Furthermore, ANG II hypertensive female mice have conserved neurovascular coupling, which describes the ability of the cerebrovasculature to adjust blood flow to meet neuronal metabolic demands (69, 70). These previous reports and data presented here suggest that sex-dependent protection against PA and neuronal impairments may mediate maintained cognitive function in hypertensive female mice.

Increased inflammation is a hallmark of various hypertension-associated neurovascular alterations, including vascular remodeling (71), endothelial dysfunction (72), and cognitive impairment. The anti-inflammatory effects of estrogen are documented (73, 74), and this reduction of inflammatory factors helps maintain neurovascular health in pathological states. At baseline, male mice have more proinflammatory microglia than female mice, and male mice that have undergone cerebral ischemia have a more favorable outcome after the transplantation of microglia isolated and purified from female mice (75). Furthermore, female mice have more GFAP-positive astrocytes than male mice, and the female sex protects against reactive astrogliosis after injury (76, 77). Our data are consistent with these reports and suggest that male mice have a greater inflammatory response to ANG II infusion than female mice. ANG II infusion directly increases inflammation and oxidative stress via increased NADPH oxidase activity (78–80). Importantly, others have demonstrated that oxidative stress impairs AKAP150-TRPV4 channel signaling at MEPs in mesenteric arteries (81), which likely mediates disrupted cooperative gating between AKAP150 and TRPV4 in hypertension (36). It is, therefore, possible that reduced inflammation and oxidative stress observed in the female mice facilitate their protection against impaired TRPV4-mediated dilation and cognitive dysfunction. Future studies will be necessary to directly investigate the influence of sex hormones on neuroinflammation and TRPV4 signaling in Pas.

There are some limitations in our study that we must address. It is important to acknowledge the sex differences in RAS activation that may contribute to our observations. ANG II exerts its effects on the vasculature by activating both AT1R and AT2R. AT1R activation in vascular smooth muscle cells leads to vasoconstriction, cell proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix deposition (82–84). AT1R activation also increases inflammation and oxidative stress through NADPH oxidase activity (85, 86). AT2R activation plays a counterregulatory role in the effects of AT1R, promoting vasodilation, NO production, angiogenesis, and reducing neuroinflammation (87). Notably, female rats have a higher ratio of AT2R to AT1R than males, shifting the balance of RAS system activation toward cardiovascular protection (88–90). When compared with male rats, females also express more angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), an enzyme responsible for converting ANG II to angiotensin-(1–7) (89). Angiotensin-(1–7) activates the Mas receptor, which promotes vasodilation, and combats inflammation, vascular oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction (91–93). The sex differences in RAS activation are hormone dependent, with testosterone stimulating the ANG II-AT1R pathway (94–96) and estrogen stimulating the ANG II-AT2R/angiotensin-(1–7)-Mas receptor pathway (97–100). Given that this study was conducted in relatively young mice, it is highly likely that sex differences in RAS contribute to the observations in the present study, including differences in blood pressure elevation, vascular remodeling, and neuroinflammation. It is also important to note that estrogen exerts neuroprotective effects via pathways beyond RAS (74). In addition, although laser speckle contrast imaging allows for the assessment of blood flow alterations on the brain’s surface, it does not allow for measurements at the level of the PAs. This prevents us from determining hypertension-induced sex differences in blood flow alterations in the microcirculation. Throughout this study, ANG II-infused female mice gained more weight than ANG II-infused male mice, which would impact the dose of ANG II received (male ANG II: 0.13 ± 0.2 g, female 800 ng ANG II: 2 ± 0.7 g, female 1,200 ng ANG II: 2.3 ± 0.4 g; P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction). However, we do not believe this small degree of weight gain would significantly alter the outcome of the study. In addition, this study did not include experiments to directly assess the influence of sex hormones on the vascular and cognitive changes observed. Our goal was to determine sex differences in response to hypertension in young mice. Future studies will be focused on assessing the specific role sex hormones play in this paradigm.

This study is the first to directly compare sex differences in PA and cognitive function in hypertension. To make these comparisons, we took a novel approach and matched both the dose of ANG II and the blood pressure elevation between the sexes. In summary, hypertensive female mice were protected from impaired TRPV4-mediated PA dilation and associated cognitive decline typically observed in hypertensive male mice. This was accompanied by less neuroinflammation in female mice. Our findings indicate that some, but not all, of the adverse effects of ANG II are mitigated by female sex hormones. Furthermore, we demonstrate that, at least in females, it is possible to have cerebral hypoperfusion yet be cognitively intact. Understanding sex differences in cerebrovascular physiology and the influence of hypertension in young mice is an essential first step in defining underlying sex-dependent mechanisms in vascular dementia development.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-HL137694-01 and PO1-HL070687 (to W. F. Jackson and A. M. Dorrance) and R21-AG074514-02 (to A. M. Dorrance) and American Heart Association Grant 22PRE900136 (to L. C. Chambers). L. C. Chambers was also supported by NIH Grant 1T32GM142521-01.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.C.C., W.F.J., and A.M.D. conceived and designed research; L.C.C. and M.Y. performed experiments; L.C.C. and M.Y. analyzed data; L.C.C., W.F.J., and A.M.D. interpreted results of experiments; L.C.C. prepared figures; L.C.C. drafted manuscript; L.C.C., W.F.J., and A.M.D. edited and revised manuscript; L.C.C., M.Y., W.F.J., and A.M.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 18: 700–789, 2022. doi: 10.1002/alz.12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fernando MS, Ince PG; MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing Neuropathology Study Group. Vascular pathologies and cognition in a population-based cohort of elderly people. J Neurol Sci 226: 13–17, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilsanz P, Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Mungas DM, DeCarli C, Dean A, Whitmer RA. Female sex, early-onset hypertension, and risk of dementia. Neurology 89: 1886–1893, 2017. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hébert R, Lindsay J, Verreault R, Rockwood K, Hill G, Dubois MF. Vascular dementia: incidence and risk factors in the Canadian study of health and aging. Stroke 31: 1487–1493, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shih AY, Blinder P, Tsai PS, Friedman B, Stanley G, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. The smallest stroke: occlusion of one penetrating vessel leads to infarction and a cognitive deficit. Nat Neurosci 16: 55–63, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nn.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stanimirovic DB, Friedman A. Pathophysiology of the neurovascular unit: disease cause or consequence? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 1207–1221, 2012. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diaz-Otero JM, Fisher C, Downs K, Moss EM, Jaffe IZ, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor mediates parenchymal arteriole and posterior cerebral artery remodeling during angiotensin ii–induced hypertension. Hypertension 70: 1113–1121, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diaz-Otero JM, Yen T-C, Fisher C, Bota D, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism improves parenchymal arteriole dilation via a TRPV4-dependent mechanism and prevents cognitive dysfunction in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H1304–H1315, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00207.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diaz-Otero JM, Yen T-C, Ahmad A, Laimon-Thomson E, Abolibdeh B, Kelly K, Lewis MT, Wiseman RW, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channels are important regulators of parenchymal arteriole dilation and cognitive function. Microcirculation 26: e12535, 2019. doi: 10.1111/micc.12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matin N, Fisher C, Lansdell TA, Hammock BD, Yang J, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition improves cognitive function and parenchymal artery dilation in a hypertensive model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Microcirculation 28: e12653, 2021. doi: 10.1111/micc.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arias-Loza P-A, Muehlfelder M, Pelzer T. Estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular oxidative stress. Pflugers Arch 465: 739–746, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duckles SP, Krause DN. Cerebrovascular effects of oestrogen: multiplicity of action. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 801–808, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fredette NC, Meyer MR, Prossnitz ER. Role of GPER in estrogen-dependent nitric oxide formation and vasodilation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 176: 65–72, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McIntyre M, Hamilton CA, Rees DD, Reid JL, Dominiczak AF. Sex differences in the abundance of endothelial nitric oxide in a model of genetic hypertension. Hypertension 30: 1517–1524, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McNeill AM, Zhang C, Stanczyk FZ, Duckles SP, Krause DN. Estrogen increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase via estrogen receptors in rat cerebral blood vessels: effect preserved after concurrent treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate or progesterone. Stroke 33: 1685–1691, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016325.54374.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brands MW, Banes-Berceli AKL, Inscho EW, Al-Azawi H, Allen AJ, Labazi H. Interleukin 6 knockout prevents angiotensin II hypertension: role of renal vasoconstriction and janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation. Hypertension 56: 879–884, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xue B, Pamidimukkala J, Hay M. Sex differences in the development of angiotensin II-induced hypertension in conscious mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2177–H2184, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00969.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwinn DA, McIntyre RW, Reves JG. Isoflurane-induced vasodilation: role of the alpha-adrenergic nervous system. Anesth Analg 71: 451–459, 1990. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polycarpou A, Hricisák L, Iring A, Safar D, Ruisanchez É, Horváth B, Sándor P, Benyó Z. Adaptation of the cerebrocortical circulation to carotid artery occlusion involves blood flow redistribution between cortical regions and is independent of eNOS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H972–H980, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00197.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matin N, Fisher C, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Bilateral common carotid artery stenosis in normotensive rats impairs endothelium-dependent dilation of parenchymal arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H1321–H1329, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00890.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pires PW, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Regulation of myogenic tone and structure of parenchymal arterioles by hypertension and the mineralocorticoid receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H127–H136, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00168.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baumbach GL, Hajdu MA. Mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 21: 816–826, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kraeuter A-K, Guest PC, Sarnyai Z. The Y-maze for assessment of spatial working and reference memory in mice. Methods Mol Biol 1916: 105–111, 2019. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barnes CA. Memory deficits associated with senescence: a neurophysiological and behavioral study in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 93: 74–104, 1979. doi: 10.1037/h0077579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Attar A, Liu T, Chan W-TC, Hayes J, Nejad M, Lei K, Bitan G. A shortened Barnes maze protocol reveals memory deficits at 4-months of age in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8: e80355, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tavares G, Martins M, Correia JS, Sardinha VM, Guerra-Gomes S, das Neves SP, Marques F, Sousa N, Oliveira JF. Employing an open-source tool to assess astrocyte tridimensional structure. Brain Struct Funct 222: 1989–1999, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1316-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blackwell JA, Silva JF, Louis EM, Savu A, Largent-Milnes TM, Brooks HL, Pires PW. Cerebral arteriolar and neurovascular dysfunction after chemically-induced menopause in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 323: H845–H860, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00276.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kehmeier MN, Bedell BR, Cullen AE, Khurana A, D'Amico HJ, Henson GD, Walker AE. In vivo arterial stiffness, but not isolated artery endothelial function, varies with the mouse estrous cycle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 323: H1057–H1067, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00369.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salinero AE, Robison LS, Gannon OJ, Riccio D, Mansour F, Abi-Ghanem C, Zuloaga KL. Sex-specific effects of high-fat diet on cognitive impairment in a mouse model of VCID. FASEB J 34: 15108–15122, 2020. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000085R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, Liedtke W, Kotlikoff MI, Heppner TJ, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science 336: 597–601, 2012. doi: 10.1126/science.1216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chambers LC, Diaz-Otero JM, Fisher CL, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism improves transient receptor potential vanilloid 4-dependent dilation of cerebral parenchymal arterioles and cognition in a genetic model of hypertension. J Hypertens 40: 1722–1734, 2022. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000003208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pekny M, Pekna M. Astrocyte reactivity and reactive astrogliosis: costs and benefits. Physiol Rev 94: 1077–1098, 2014. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilhelmsson U, Bushong EA, Price DL, Smarr BL, Phung V, Terada M, Ellisman MH, Pekny M. Redefining the concept of reactive astrocytes as cells that remain within their unique domains upon reaction to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 17513–17518, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602841103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xue B, Pamidimukkala J, Lubahn DB, Hay M. Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates estrogen protection from angiotensin II-induced hypertension in conscious female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1770–H1776, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oyola MG, Handa RJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes: sex differences in regulation of stress responsivity. Stress 20: 476–494, 2017. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2017.1369523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sonkusare SK, Dalsgaard T, Bonev AD, Hill-Eubanks DC, Kotlikoff MI, Scott JD, Santana LF, Nelson MT. AKAP150-dependent cooperative TRPV4 channel gating is central to endothelium-dependent vasodilation and is disrupted in hypertension. Sci Signal 7: ra66, 2014. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McNeill AM, Kim N, Duckles SP, Krause DN, Kontos HA. Chronic estrogen treatment increases levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein in rat cerebral microvessels. Stroke 30: 2186–2190, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pessôa BS, Slump DE, Ibrahimi K, Grefhorst A, van Veghel R, Garrelds IM, Roks AJM, Kushner SA, Danser AHJ, van Esch JHM. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor- and acetylcholine-mediated relaxation: essential contribution of female sex hormones and chromosomes. Hypertension 66: 396–402, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cao S, Anishkin A, Zinkevich NS, Nishijima Y, Korishettar A, Wang Z, Fang J, Wilcox DA, Zhang DX. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) activation by arachidonic acid requires protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 293: 5307–5322, 2018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.811075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fan H-C, Zhang X, McNaughton PA. Activation of the TRPV4 ion channel is enhanced by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 284: 27884–27891, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cipolla MJ, Smith J, Kohlmeyer MM, Godfrey JA. SKCa and IKCa channels, myogenic tone, and vasodilator responses in middle cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles: effect of ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke 40: 1451–1457, 2009. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ibrahim J, McGee A, Graham D, McGrath JC, Dominiczak AF. Sex-specific differences in cerebral arterial myogenic tone in hypertensive and normotensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1081–H1089, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00752.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reed JT, Pareek T, Sriramula S, Pabbidi MR. Aging influences cerebrovascular myogenic reactivity and BK channel function in a sex-specific manner. Cardiovasc Res 116: 1372–1385, 2020. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen D-R, Jiang H, Chen J, Ruan C-C, Han W-Q, Gao P-J. Involvement of angiotensin ii type 1 receptor and calcium channel in vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction in rats with pressure overload. Curr Med Sci 40: 320–326, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Forrester SJ, Booz GW, Sigmund CD, Coffman TM, Kawai T, Rizzo V, Scalia R, Eguchi S. Angiotensin II signal transduction: an update on mechanisms of physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 98: 1627–1738, 2018. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pacurari M, Kafoury R, Tchounwou PB, Ndebele K. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in vascular inflammation and remodeling. Int J Inflam 2014: 689360, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/689360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Husarek KE, Katz PS, Trask AJ, Galantowicz ML, Cismowski MJ, Lucchesi PA. The angiotensin receptor blocker losartan reduces coronary arteriole remodeling in type 2 diabetic mice. Vascul Pharmacol 76: 28–36, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiménez-Altayó F, Martín A, Rojas S, Justicia C, Briones AM, Giraldo J, Planas AM, Vila E. Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion causes different structural, mechanical, and myogenic alterations in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H628–H635, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00165.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roman MJ, Saba PS, Pini R, Spitzer M, Pickering TG, Rosen S, Alderman MH, Devereux RB. Parallel cardiac and vascular adaptation in hypertension. Circulation 86: 1909–1918, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moss ME, Carvajal B, Jaffe IZ. The endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor: contributions to sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Ther 203: 107387, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Ryan C, Price JC, Greer P, Sutton-Tyrrell K, van der Veen FM, Meltzer CC. Reduced cerebral blood flow response and compensation among patients with untreated hypertension. Neurology 64: 1358–1365, 2005. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158283.28251.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Muller M, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FL, Mali WPTM, Geerlings MI; SMART Study Group. Hypertension and longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow: the SMART-MR study. Ann Neurol 71: 825–833, 2012. doi: 10.1002/ana.23554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Waldstein SR, Lefkowitz DM, Siegel EL, Rosenberger WF, Spencer RJ, Tankard CF, Manukyan Z, Gerber EJ, Katzel L. Reduced cerebral blood flow in older men with higher levels of blood pressure. J Hypertens 28: 993–998, 2010. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328335c34f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Duncombe J, Kitamura A, Hase Y, Ihara M, Kalaria RN, Horsburgh K. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion: a key mechanism leading to vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Closing the translational gap between rodent models and human vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Clin Sci (Lond) 131: 2451–2468, 2017. doi: 10.1042/CS20160727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wolters FJ, Zonneveld HI, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Koudstaal PJ, Vernooij MW, Ikram MA; Heart-Brain Connection Collaborative Research Group. Cerebral perfusion and the risk of dementia: a population-based study. Circulation 136: 719–728, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]