1. Introduction

Any abnormal connection between the carotid artery system and the cavernous venous system is called a cavernous carotid fistula [1]. Cavernous carotid fistula may occur following trauma or spontaneously [2]. CCF is one of the rare complications that may occur after head trauma. Although it is rare, it is very important and significant. CCF is reported to occur in 0.2% of patients with cranial trauma [3]. CCF is divided into direct and indirect types according to the place where the fistula separates from the carotid artery. Direct CCFs are those that arise directly from the carotid artery, while indirect CCFs are those that arise from the branch vessels of the carotid artery [4]. Abnormal communication between the carotid artery and the cavernous sinus can cause various symptoms such as diplopia, headache, red eyes, protruding eyes, etc [5]. The cavernous sinus is a structure composed of a group of thin-walled veins [6]. And the carotid artery and its branches pass through this venous complex [7]. Blood pressure in the ocular veins rises due to any abnormal connection between these two venous and arterial systems [8]. Increased blood pressure in the cavernous sinus also puts pressure on the nerves around this sinus [9]. Which includes cranial nerves III, IV, V and VI. The symptoms seen in CCF are very similar to those of a skull base fracture following trauma. Due to this issue and the uncommon nature of CCF, diagnosis of this disorder may be difficult. Therefore, this case report is presented to draw the attention of neurosurgeons and ophthalmologists to this diagnosis when dealing with trauma patients.

2. Case

The patient was a 30-year-old man who had suffered trauma at work 13 days before his visit. The patient's trauma was due to falling from a height of 3 m and hitting his head on a hard object. Due to the trauma, the patient did not experience loss of consciousness or neurological symptoms, and for this reason, he did not go to the treatment center. And now he had come to our hospital because of redness and swelling in left eye and rhinorrhea. At the beginning of the visit, the patient was fully conscious and oriented. On initial examination, a clear, colorless discharge came out of both nostrils during the valsalva maneuver. On eye examination, the right eye was normal in appearance, vision, and eye movements. But the left eye had proptosis, tears, eyelid swelling, ophtalmoplegia and mild optic disk swelling on examination [Fig. 1]. The patient did not have RAPD and anisocoria. According to the mentioned symptoms, a CT scan of the brain was requested for the patient, which showed fractures in the temporal bone, petrus, sphenoidal sinus, foramen lacerum and right side of clivus [Fig. 2, Fig. 3]. But the main cause of ocular symptoms was determined after MRI. Enlargement of the superior ocular vein and enlargement of the extraocular muscle on the left were seen on MRI. Bulging of left cavernous sinus and asymmetrical enhancement of left cavernous sinus was also presented. And all these findings confirmed the diagnosis of carotid-cavernous fistula [Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6]. Transarterial or venous embolization remains the first-line method of treatment for most CCFs as more than 90% of cases can be successfully treated this way [10]. Balloon embolization surgery was performed for the patient and the patient was discharged with good general condition and normal vision examinations. After successful intervention with complete CCF closure, symptoms such as chemosis and proptosis generally resolved within hours to days. Written consent was obtained from the patient to conduct this research.

Fig. 1.

We see the appearance of both eyes in this image. The left eye has ptosis, proptosis and chemosis.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography image in axial view showing foramen lacerum and clivus fracture.

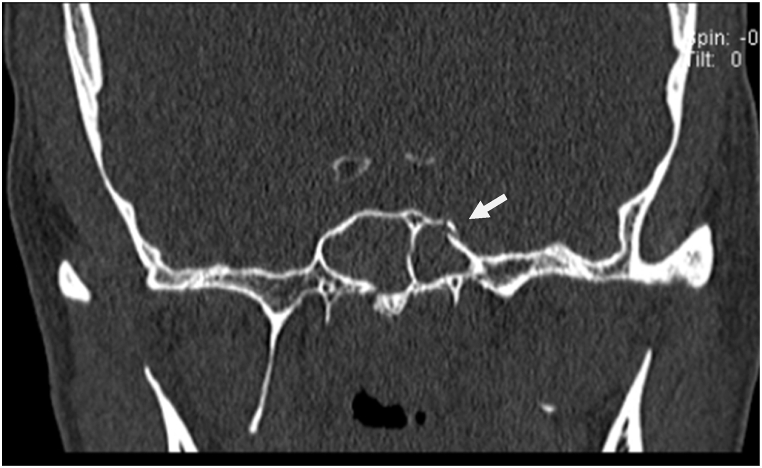

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography image in cronal view showing sphenoid bone fracture.

Fig. 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the periorbital region showing bulging of left cavernous sinus.

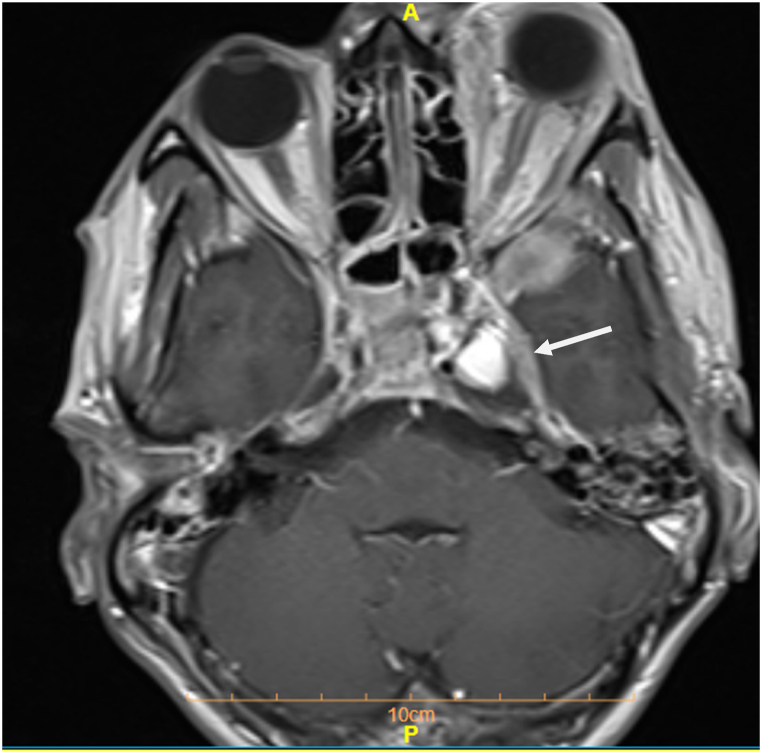

Fig. 5.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the periorbital region showing left superior ophthalmic vein enlargement.

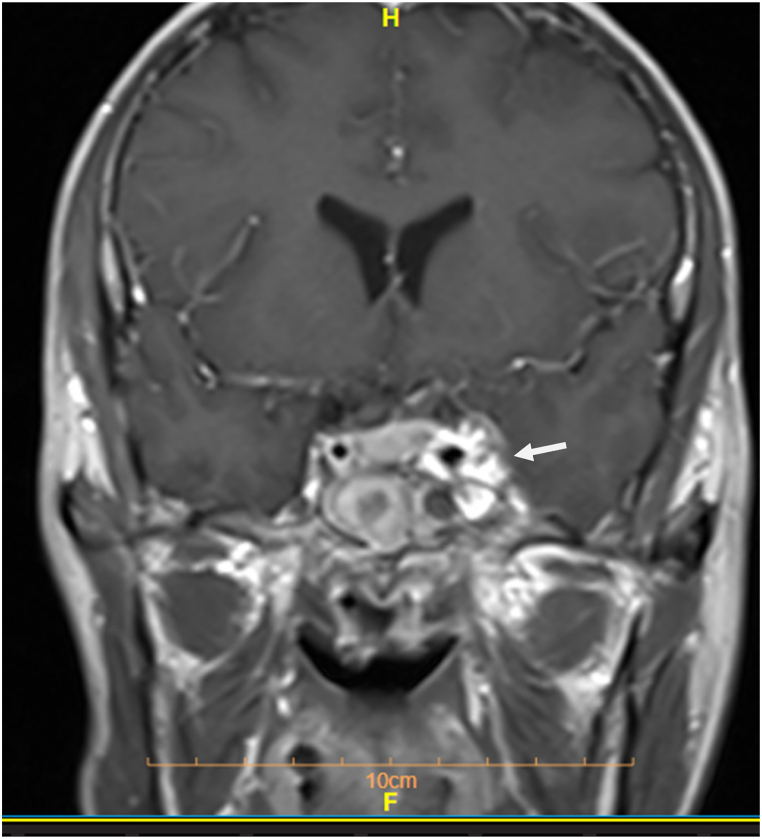

Fig. 6.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the periorbital region showing asymmetrical enhancement of left cavernous sinus.

3. Discussion

Different theories have been proposed about the mechanism of CCF formation after head trauma. According to one of the declared theories, the carotid artery is torn directly or due to bone fracture or by shear forces during trauma and carotid and cavernous fistulas are created as a result [10]. This theory is acceptable considering the skull base fractures in this case. According to another theory, a sudden increase in intraluminal pressure of the ICA with simultaneous compression of the distal artery causes rupture of the vessel wall and leads to CCF. Which may be an acceptable theory in this case. Manifestations of CCF are due to the functioning of the cavernous sinus (CS) and its venous system. So that due to the creation of a fistula between the carotid artery and this venous sinus, the pressure inside this sinus increases and causes its dysfunction. And after that, the pressure of the eye vein increases and eye symptoms appear [10]. Ocular symptoms are very common in ccf patients and most patients have symptoms such as protruding eyes, proptosis, chemosis and swelling. The interesting thing about this patient was that he had symptoms only 13 days after the trauma and had not any symptoms before. Since cavernocarotid fistulas can also present with ocular symptoms [11], neurosurgeons and should consider cavernocarotid fistulas in their first encounter with trauma patients. The patient's examination showed that this fistula can occur more rapidly than expected in people and cause irreversible complications, especially in the eye.

4. Conclusion

The clinical significance of this case was that physicians working in trauma emergencies should also consider the possibility of developing this fistula following head, face, and eye trauma. as ocular symptoms are typically attributed to direct trauma to the eye. And fistula diagnosis remains hidden.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the investigation, development and writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Keizer R. Carotid-cavernous and orbital arteriovenous fistulas: ocular features, diagnostic and hemodynamic considerations in relation to visual impairment and morbidity. Orbit. 2003;22(2):121–142. doi: 10.1076/orbi.22.2.121.14315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zanaty M., Chalouhi N., Tjoumakaris S.I., Hasan D., Rosenwasser R.H., Jabbour P. Endovascular treatment of carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurg. Clin. 2014;25(3):551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J.A., Goldstein H., Connolly E.S., Meyers P.M. Carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurg. Focus. 2012;32(5):E9. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.FOCUS1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrow D.L., Spector R.H., Braun I.F., Landman J.A., Tindall S.C., Tindall G.T. Classification and treatment of spontaneous carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. J. Neurosurg. 1985;62(2):248–256. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celik O., Buyuktas D., Islak C., Sarici A.M., Gundogdu A.S. The association of carotid cavernous fistula with Graves' ophthalmopathy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2013;61(7):349–351. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.109533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashida R., Hieshima G., Halbach V., Bentson J., Goto K. Closure of carotid cavernous sinus fistulae by external compression of the carotid artery and jugular vein. Acta Radiol., Suppl. 1986;369:580–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller N.R. Diagnosis and management of dural carotid–cavernous sinus fistulas. Neurosurg. Focus. 2007;23(5):E13. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/11/E13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhry I.A., Elkhamry S.M., Al-Rashed W., Bosley T.M. Carotid cavernous fistula: ophthalmological implications. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2009;16(2):57. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.53862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debrun G.M., Viñuela F., Fox A.J., Davis K.R., Ahn H.S. Indications for treatment and classification of 132 carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22(2):285–289. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo C.-B., Teng M., Chang F.-C., Chang C.-Y. Transarterial balloon-assisted n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate embolization of direct carotid cavernous fistulas. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2006;27(7):1535–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto I., Watabe T., Shinoda M., Hasegawa Y., Sato O. Bilateral spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistulas treated by the detachable balloon technique: case report. Neurosurgery. 1985;17(3):469–473. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198509000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.