Abstract

Tapeworms are trophically-transmitted and multi-host parasites with a complex indirect life cycle, strictly depending on predator-prey interactions. Their presence in a free-living population, mainly definitive hosts, is arduous to study due to the complexity of collecting fecal samples. However, epidemiological studies on their frequency are crucial from a public health perspective, providing information on food habits and prey selection of predators. The present study aims to update the frequency of tapeworms detected in stool samples by molecular analysis in Italian wolf populations of Umbria and Marche regions collected from 2014 to 2022. Tapeworm's total frequency was 43.2%. In detail, Taenia serialis was detected in 27 samples (21.6%), T. hydatigena in 22 (17.6%), and Mesocestoides corti (syn. M. vogae) in 2 (1.6%). Three samples were identified as M. litteratus and E. granulosus s.s. (G3) and T. pisiformis, with a proportion of 0.8%, respectively. The low frequency of E. granulosus in a hyperendemic area is discussed. The results show for the first time a high frequency of Taenia serialis not comparable to other Italian studies conducted on wild Carnivora; thus, a new ecological niche is conceivable. These findings suggest a plausible wolf-roe deer cycle for T. serialisin the investigated area.

Keywords: Canis lupus italicus, Cestoda, Echinococcus granulosus, Italian wolves, Taenia serialis, Trophically-transmitted parasites

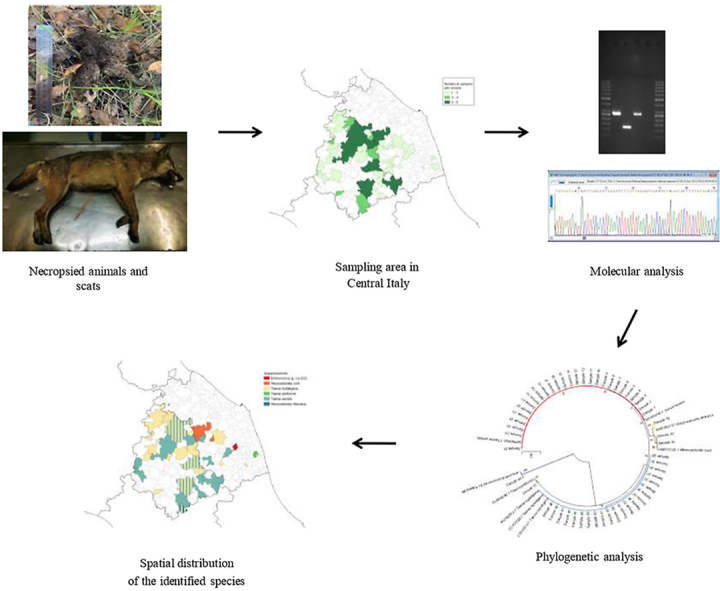

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Italian wolves in Central Italy act as definitive host for Taenia serialis.

-

•

The role of Italian wolves on echinococcosis is negligible.

-

•

The tapeworms detected provided information on the wolves' diet and zoonotic risk.

-

•

Italian wolves in Central Italy mainly prefer wild preys.

1. Introduction

Ecosystems host many species, interacting with each other within a complex network (Kondoh, 2003). There are many drivers of animal interactions in this network, and the feeding behavior, which underlines the organization of animal populations, is one of the most important (Baudrot et al., 2016). These interactions underlie the cycle of trophically-transmitted parasites (TTP) systems, which strictly depend on a predator-prey relationship (Lafferty, 1999). Typically, tapeworms benefit from this life strategy to perpetuate themselves in nature: they need predators (definitive hosts) to complete their sexual reproduction and prey (intermediate hosts) in which asexual reproduction is used. Top predators can affect prey population dynamics and indirectly multi-host TTP dynamics (Zukowski et al., 2020).

Italian wolf (Canis lupus italicus Altobello, 1921), along with Marsican brown bear (Ursus arctos marsicanus Altobello, 1921), is the top mammalian predator in Central Italy (CIT). Italian wolves were nearly extinct in the late 1940s, surviving at their historical minimum population size as two isolated populations in the Southern Apennines (Boitani, 1992). However, since the late eighties, conservation policies, and the increase in the number of wild ungulates, the main wolf prey, have ensured their natural re-expansion from the Southern Apennines toward the Northwestern Apennines and French Alps (Marucco and McIntire, 2010).

During the last 35 years, several studies have focused on describing the frequency and distribution of the Italian wolf parasites, highlighting wildlife's pivotal role in the potential transmission of zoonotic pathogens (Jones et al., 2008). Since the last century, taeniid infections have been known to be expected in Italy, particularly along Northern Apennines (Guberti et al., 1993, 2004). Recent studies based on molecular approaches improved tapeworm identification. In their studies, Gori et al. (2015), Macchioni et al. (2021), Massolo et al. (2018), and Poglayen et al. (2017) investigated wolf scats on the presence of taeniid eggs identifying several species of Taenia (especially T. hydatigena) and Echinococcus granulosus. In particular (Massolo et al., 2018), unexpectedly detected the presence of E. multilocularis eggs in wolves and dogs and E. ortleppi (G5) in wolves. This study reported E. ortleppi(G5) for the first time in wolves in Italy and, in general, in definitive hosts in this country.

Those studies also point particular attention to the potential role of wolves in the transmission and diffusion of Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto, mostly genotype G1 (formerly “sheep strain”), agent of the vast majority of cystic echinococcosis (CE) cases in livestock and wild ungulates (Deplazes et al., 2017), but also in humans who act as intermediate hosts (Alvarez Rojas et al., 2014). CE is a significant parasitic disease, particularly in the Mediterranean basin (Sadjjadi, 2006), whose diffusion is strictly related to the pastoralist-vocated areas (Casulli et al., 2022; Ghatee et al., 2020). In Italy, the official data on sheep CE is summarized by Deplazes et al. (2017), while the actual prevalence in adult sheep is at least 40% (Poglayen et al., 2008). The low prevalence of fertile cysts detected in wild ruminants (Guberti et al., 2004), along with a low number of infected wolves (Poglayen et al., 2017), may consider the wolf in a similar epidemiological context, closely linked to the domestic cycle (Guberti et al., 2004), rather than a wild one.

To better understand the wolf diet, it should be considered that the larval stage of each cestode has a specific host range. Notably, Taenia hydatigena is well-known in wild and domestic ungulates, whereas T. pisiformis in wild and domestic lagomorphs. A particular mention should be given to T. serialis, whose definitive and intermediate hosts still need to be clarified. Recently, Citterio et al. (2021) detected T. serialis eggs in 0.2% of 2872 red foxes collected in Northern Italy, but the Italian wolf has never been detected positive so far. Conversely, Morandi et al. (2022a) described for the first time the roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) as a suitable intermediate host for T. serialis, reporting fertile cysts from muscle tissues.

The cyclophillidean tapeworm Mesocestoides sp. is known to parasitize wild and domestic Carnivora (Ulziijargal et al., 2020) in the role of definitive hosts. Its life cycle is complex, requiring two or three intermediate hosts to complete (Zaleśny and Hildebrand, 2012; McAllister et al., 2013). In the first intermediate host (arthropod), the oncosphere develops into a second larval stage, then within the second intermediate host, generally small mammals (Loos-Frank, 1991), develop to a tetrathyridium as a third larval stage; however, some parts of its cycle are still challenging to understand (Sapp and Bradbury, 2020). Seven species of Mesocestoides have been recorded in Europe, with M. litteratus and M. lineatus being the most widely distributed species. However, phylogenetic analyses allowed us to point out other Mesocesoides entities which are genetically divergent (Varcasia et al., 2018). Molecular tools are essential to diagnose correctly and discriminate zoonotic pathogens from non-zoonotic ones (McManus, 2006). Taeniids eggs, for example, are not distinguishable from each other, and within this family, severe zoonotic agents (i.e., E. granulosus and E. multilocularis) are present (Trachsel et al., 2007; Conraths and Deplazes, 2015). Furthermore, this approach increases the sensitivity that is otherwise hard to reach by using traditional fecal flotation methods.

The present study aims to update the frequency of tapeworms detected in stool samples by molecular analysis in Italian wolf populations of Umbria and Marche regions through 9 years. Results obtained by this long-term survey could raise speculation on the wolf's diet and consider the Italian wolf as a downstream member of the domestic cycle for the E. granulosus transmission due to the absence of a demonstrated wild animal parasite cycle.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area and sample collection

From January 2014 to June 2022, 125 wolf fecal samples were collected from Umbria and Marche regions (CIT, Fig. 1A); some came from the Monti Sibillini National Park (MSNP) area, whose surface lays all within the two regions. Sampling included feces obtained from animals found dead, mainly due to road accidents or hosted in wildlife rescue centers, and others collected during wildlife monitoring activities. The identification and collection of wolf scats were performed by ISPRA (Institute for Environmental Protection and Research, Italian Ministry for the Environment and the Protection of Land and Sea) to reduce as much as possible the misidentification between wolves and foxes or dog scats. Each sample was stored in individually labeled sterile zip-lock plastic bags or sterile plastic tubes to prevent contamination. As a safety precaution, they were stored for 10 days at −80 °C (Eckert et al., 2001), then at −20 °C until DNA extraction.

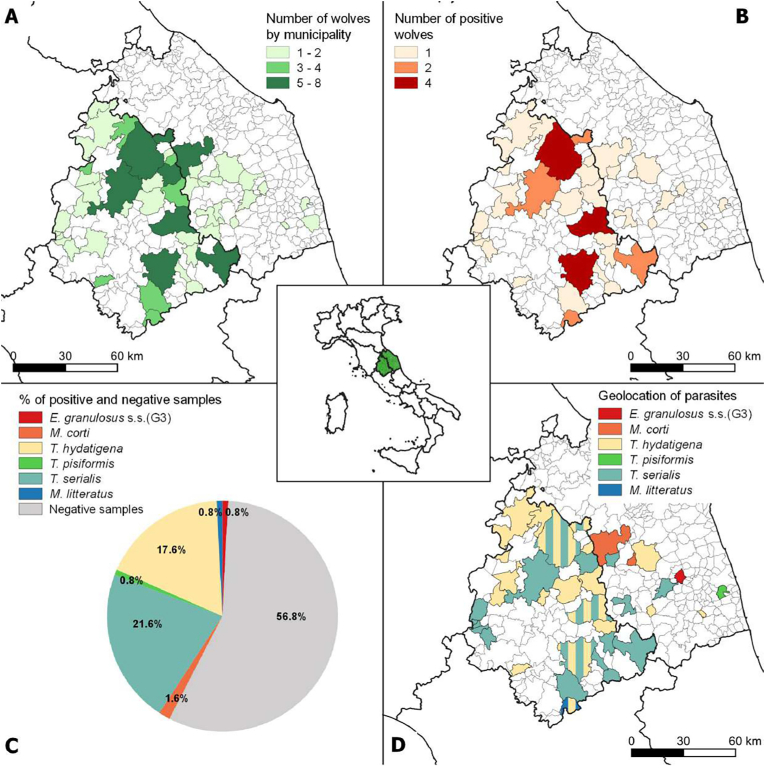

Fig. 1.

Details of sampling and results: number of wolves by region (A); number of positive wolves (B); percentages of positive and negative samples (C); geolocation of parasites (D).

2.2. Molecular analysis

Molecular investigations were carried out for the identification of the parasites. Fecal samples were investigated on the presence of cestode DNA, such as Taenia spp., Echinococcus multilocularis, and Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato (s.l.). Genomic DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN®, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions and then amplified by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (mPCR) to amplify diagnostic fragments within the mitochondrial genome (Trachsel et al., 2007). In detail, three different amplicons sizes could be obtained using distinct primer pairs: 395 bp for E. multilocularis nad1 gene using Cest1 and Cest2, 267 bp for Taenia spp. rrnS gene using Cest3 and Cest5, and 117 bp for E. granulosus s.l. rrnS gene utilizing Cest4 and Cest5. Electrophoresis was performed on 2% agarose gel stained with Midori Green Advance (NIPPON Genetics®, Düren, Germany). The amplicon, referred to as E. granulosus s.l., was successfully amplified with nad5 target (Kinkar et al., 2018) and able to identify E. granulosus sensu stricto (s.s.) (759 bp). PCR-positive reactions were purified by QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN®, Valencia, CA, USA). Sanger sequencing was performed using BrilliantDyeTM Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (NimaGen®, Nijmegen, Netherlands) and primers Cest5seq for Taenia spp. and EGnd5F1/EGnd5R1 for E. granulosus s.s. Electropherograms were analyzed by a 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems®, Foster City, CA, USA). Consensus sequences were created by BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor software v7.0.9.0 and then aligned in the GenBank database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). A Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree has been constructed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (MEGA11 Software) to confirm the results.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data on sex and age were obtained from necropsied and rescued wolves. First, the wolf age was estimated through tooth wear (Gipson et al., 2000). Then the population was divided into three categories: pups, yearlings and young adults, and mature animals with <1 year old, 1–3 years old, and> 3 years old, respectively. Next, differences in the proportion of positive samples by gender, age class, and territory (regions and municipalities) were explored by the Pearson's χ2 test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Excel, 2013) and Stata Statistical Software (Release 16, College Station, TX, StataCorp LLC).

The GIS software (QGIS version 3.10.11-A Coruña) was used to design maps about the spatial distribution of total, positive, and sequenced samples by municipality.

3. Results

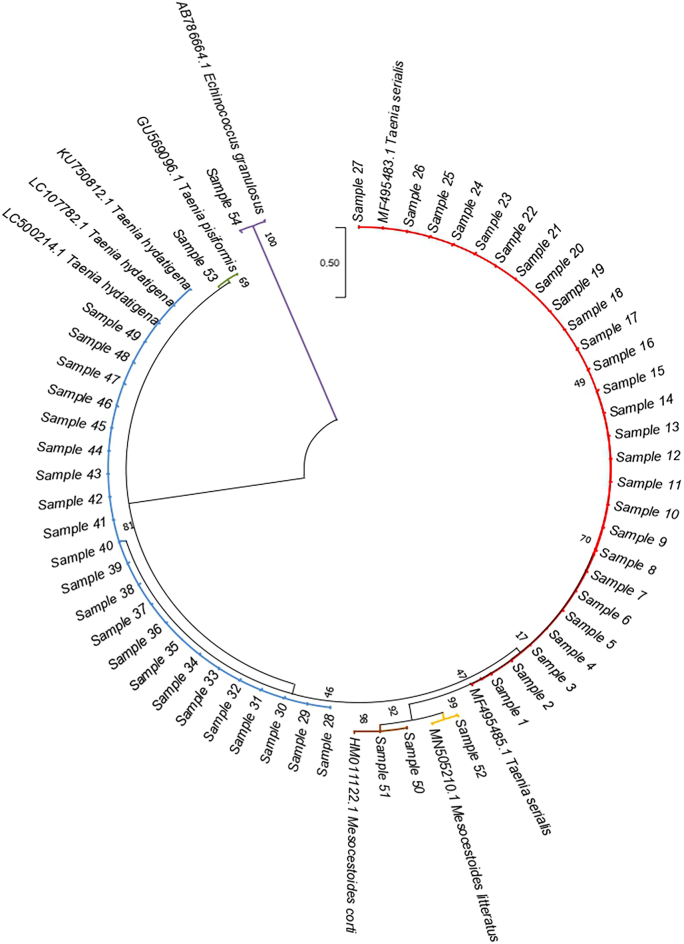

One hundred twenty-five fecal samples were investigated to detect tapeworm DNA obtained from wolves found dead and then necropsied (n = 89) or collected during the wolf monitoring activities (n = 36). At necropsy, 55 males and 34 females were identified; animals were classified by age as 21 pups (10 males and 11 females), 36 yearlings and young adults (24 males and 12 females), and 32 mature wolves (21 males and 11 females). Tapeworm DNA distribution is shown in Fig. 1B with a frequency of 43.2% (54/125), as observed in Fig. 1C. Gel electrophoresis showed that 53 were positive forTaenia spp., only one gave an amplicon referable to E. granulosus s.l., while no sample was positive for E. multilocularis. Sequencing analyses results are summarized in Table 1: T. serialis was the most common species detected (21.6%), followed by T. hydatigena (17.6%), and Mesocestoides corti (syn. M. vogae) (1.6%); three samples were identified as M. litteratus, E. granulosus s.s. genotype G3, and T. pisiformis, with a proportion of 0.8%, respectively (see also Fig. 1C and Table S1). Fig. 2 shows the phylogenetic analysis related to the sequences detected in the study. Overall, females showed a lower proportion of positivity than males (41.2% vs56.4%), though this difference was no significant (P = 0.164, Table 2). As for the age classes, adults were most commonly detected positive (59.4%) compared to the other age classes (47.6% and 44.4% of pups and yearlings and young adults, respectively). However, no significant differences were observed (P = 0.448, Table 3). Most of the samples came from the municipalities sited along the Umbria-Marche border (Fig. 1A). The Umbrian municipalities showed the majority of the positive samples (Fig. 1B), but there was no statistically significant difference between the two regions (P = 0.812). Fig. 1D shows the distribution of the sequenced species. Geolocation was unavailable for 10 samples (5 positives and 5 negatives).

Table 1.

Sequencing analyses results of the 54 positive samples.

| Taenia serialis | Taenia hydatigena | Mesocestoides corti (syn. M. vogae) | Mesocestoides litteratus | Taenia pisiformis | Echinococcus granulosus s.s. (G3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive samples | 27 (21.6%) | 22 (17.6%) | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree of the sequenced Taenia species and E. granulosus s.s. G3. Maximum Composite Likelihood method, 1000 bootstraps (MEGA11 Software).

Table 2.

Proportion of positive and negative samples by sex.

| Sex | Negative | Positive | Positive/sex (%) | Total samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 20 | 14 | 41.2% | 34 |

| Males | 24 | 31 | 56.4% | 55 |

| Total samples | 44 | 45 | - | 89 |

Table 3.

Proportion of positive and negative samples by class age.

| Class age | Negative | Positive | Positive/Class age (%) | Total samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pups | 11 | 10 | 47.6% | 21 |

| Yearlings and young adults | 20 | 16 | 44.4% | 36 |

| Mature wolves | 13 | 19 | 59.4% | 32 |

| Total samples | 44 | 45 | - | 89 |

4. Discussion

The study of cestode infections provides information on large carnivore food habits (Bowman, 2009) since tapeworms, known as trophically-transmitted parasites (TTP), profit from indirect life cycle based on a specific predator-prey interaction (Bryan et al., 2012). Here, results on the presence of cestodes in Italian wolf stool samples from Umbria and Marche regions (Central Italy), using a molecular approach, are provided. Scats have been collected during 9 years from wolves found dead or hosted in wildlife rescue centers, and others collected from wolf monitoring activities. Among the proportion of scats collected directly from the environment, we cannot exclude that some stool samples belong to the same individual. Furthermore, even though performed by trained staff, the method used to identify wolf scats cannot exclude that they belonged to free-roaming dogs.

This study detected tapeworm DNA in 43.2% of the fecal samples examined. The proportion is higher than those obtained by Gori et al. (2015) and Macchioni et al. (2021), who described frequencies of 33% in the Liguria region and 34% in a highly anthropic area of Tuscany, respectively. Conversely, Poglayen et al. (2017) showed a higher frequency of taeniid eggs, reporting a proportion of positive wolves close to 60% in Northern Italian Apennines. In Europe, cestoda frequency in the wolf population has been reported as follows: 23% in Portugal, 80% in Spain (Segovia et al., 2001), and 100% in Estonia (Moks et al., 2006).

From a public health perspective, it is crucial to highlight the absence of Echinococcus multilocularis in the Central Apennine. Alveolar echinococcosis is a severe life-threatening parasitic disease potentially affecting humans with a fatality rate of around 70% (Romig et al., 2017). Currently, in Italy, some autochthonous infected areas are spotted in the North-Eastern Alps (Casulli et al., 2005). In any case, no human cases have been reported so far.

Surprisingly, the DNA of another important zoonotic agent, E. granulosus sensu stricto (G3), was detected only in one stool sample with a frequency of 0.8%. Some Italian studies have been conducted on the possible role of the wolf in a hypothetical wild cycle of E. granulosus (Guberti et al., 2004, 2005; Gori et al., 2015; Poglayen et al., 2017). In CIT, a high sheep farming-vocated area (Cecchini et al., 2021), the main actors for the maintenance of E. granulosus in nature are still represented by shepherd- or stray-dogs as definitive hosts, and sheep as intermediate hosts (Garippa et al., 2004). A wild cycle of E. granulosus has never been demonstrated in Italy yet. According to Guberti et al. (2004, 2005), the limited prevalence in wolves along with the low fertility rates of CE cysts in wild boar in the studied area (Morandi, pers. comm.) - the primary prey of wolves – and in other wild ruminant species can exclude wildlife by the E. granulosus cycle in Italy, suggesting, instead, a spillover from the domestic life cycle (Poglayen et al., 2017; Romig et al., 2017). Moreover, E. granulosus was found in only one DNA sample characterized as E. granulosus s.s. G3 genotype. The G3 genotype (formerly “buffalo strain”) is not the most represented across the Mediterranean basin, where the genotype G1 is prevalent (Casulli et al., 2012; Bonelli et al., 2020). It has been identified in different intermediate hosts (sheep, cattle, goats, pigs, humans), and its life cycle involves prevalently domestic species even though it has been reported the infection of wild ungulates (Busi et al., 2007; Nakao et al., 2010; Kinkar et al., 2018).

Taenia serialis DNA was the most commonly detected, with a frequency of 21.6%. Although this taeniid has already been sporadically detected in wolves from Portugal (Pereira et al., 2023) and the US (Brandell et al., 2022) and in red foxes from Northern Italy (Citterio et al., 2021), its frequency resulted lower compared to our: 5.9%, 5.9%, and 0.2%, respectively. Domestic and wild lagomorphs, rodents, rarely cats, sheep (Deplazes et al., 2019), and marsupials (Dunsmore and Howkins, 1968; Hough, 2000) are historically considered T. serialis intermediate hosts. Several cases are also reported in primates (Schneider-Crease et al., 2017). In the same studied area, the roe deer has been recently reported as a novel suitable intermediate host for T. serialis, where three cases have been described (Morandi et al., 2022a; Morandi et al., 2022b; Morandi, unpublished). These findings may suggest a plausible wolf-roe deer cycle for T. serialis in the investigated area rather than wolf-lagomorphs. However, further research is needed to explore this association better. Besides this, the study highlights an extremely low frequency of T. pisiformis with only 0.8% of DNA-positive-wolves. Therefore, lagomorphs (i.e., brown hare) and rodents, the main intermediate hosts for this taeniid, probably are considered prey of minor importance in CIT.

Taenia hydatigena DNA was the second most frequently detected (17.6%). It is a worldwide distributed parasite affecting wild and domestic animals. In detail, definitive hosts are domestic dogs and cats, and other wild carnivores such as red fox (Vulpes vulpes), golden jackal (Canis aureus), European lynx (Lynx lynx), raccoon (Procyon lotor), and brown bear (Ursus arctos). Its presence in intermediate hosts is wide and includes wild species such as wild boar (Sus scrofa), fallow deer (Dama dama), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), and moose (Alces alces), even if domestic species (pigs, sheep, goats, cattle, buffalo) are prevalent (Filip et al., 2019). Additionally, T. hydatigena is considered a significant cause of economic and production losses in the livestock industry in developing and industrialized countries (Nguyen et al., 2016).

DNA of Mesocestoides corti (syn. M. vogae) and M. litteratus was found in 1.6% and 0.8% of samples, respectively. Detecting these tapeworms is not surprising because primers used by Trachsel et al. (2007) can also detect Mesocestoides species. However, the percentage observed was lower than those described in Italy by Guberti et al. (1993), who reported 8.7% of positive samples. The tetrathyridium infective stage of Mesocestoides affects small vertebrates, such as reptiles, amphibians, and small mammals. Therefore, these low frequencies allow to hypothesize that wolves do not attack small mammals in the area. Moreover, the matrix selected for the study, represented by fecal matter, limits the detection sensitivity for these species whose eggs are shed inside proglottids and are not contained in the matter.

The most appropriate diagnostic approach could be working on the adult parasite directly collected from the intestinal lumen, but it appears time-consuming. For this reason, a molecular approach has been preferred, considering that additional information could be obtained through an mPCR and subsequent sequencing. Taeniid eggs with similar morphological features have been detected belonging to 6 different genera of Cestoda.

In conclusion, the obtained results give insights into the role of the Italian wolf in CIT as the study covers 9 years. To the best of the authors' knowledge, there is no evidence of a wild cycle of CE in Italy with the wolf as the principal character. The lack of a national CE control program remains the only one responsible for the Italian situation, and the sheep-dog cycle is the only truly existing epidemiologic scenario. A new ecological niche for Taenia serialisis conceivable where the wolf is the primary definitive host and roe deer a suitable intermediate host. Having wildlife surveillance plans is a crucial component for industrialized countries, as also the Regulation (EU) 2016/429 contemplates, to detect and manage the diffusion of wildlife diseases which may also affect humans and domestic animals.

The data obtained could help to understand the distribution of tapeworms in CIT better, providing helpful information on the feeding behavior of Italian wolves. Studies specifically conducted to explore the wolf's diet will be conducted in the near future.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank WildUmbria Association (Umbria Region) and Smilax Association (Marche Region) and their volunteers who provided the majority of the samples examined in this work. They would also like to thank Michele Tentellini, Federico Consalvi, Francesco Grecchi, and Roberta Fraticelli for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2023.03.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Alvarez Rojas C.A., Romig T., Lightowlers M.W. Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato genotypes infecting humans – review of current knowledge. Int. J. Parasitol. 2014;44:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudrot V., Perasso A., Fritsch C., Raoul F. Competence of hosts and complex foraging behavior are two cornerstones in the dynamics of trophically transmitted parasites. J. Theor. Biol. 2016;397:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitani L. Wolf research and conservation in Italy. Biol. Conserv. 1992;61:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(92)91102-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli P., Dei Giudici S., Peruzzu A., Piseddu T., Santucciu C., Masu G., Mastrandrea S., Delogu M.L., Masala G. Genetic diversity of Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto in Sardinia (Italy) Parasitol. Int. 2020;77 doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2020.102120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman D.D. ninth ed. 2009. Georgis' Parasitology for Veterinarians. (St. Louis) [Google Scholar]

- Brandell E.E., Jackson M.K., Cross P.C., Piaggio A.J., Taylor D.R., Smith D.W., Boufana B., Stahler D.R., Hudson P.J. Evaluating noninvasive methods for estimating cestode prevalence in a wild carnivore population. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan H.M., Darimont C.T., Hill J.E., Paquet P.C., Thompson R.C.A., Wagner B., Smits J.E.G. Seasonal and biogeographical patterns of gastrointestinal parasites in large carnivores: wolves in a coastal archipelago. Parasitology. 2012;139:781–790. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busi M., Šnábel V., Varcasia A., Garippa G., Perrone V., De Liberato C., D'Amelio S. Genetic variation within and between G1 and G3 genotypes of Echinococcus granulosus in Italy revealed by multilocus DNA sequencing. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;150:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casulli A., Interisano M., Sreter T., Chitimia L., Kirkova Z., La Rosa G., Pozio E. Genetic variability of Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto in Europe inferred by mitochondrial DNA sequences. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012;12:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casulli A., Manfredi M.T., La Rosa G., Di Cerbo A.R., Dinkel A., Romig T., Deplazes P., Genchi C., Pozio E. Echinococcus multilocularis in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) of the Italian Alpine region: is there a focus of autochthonous transmission? Int. J. Parasitol. 2005;35:1079–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casulli A., Massolo A., Saarma U., Umhang G., Santolamazza F., Santoro A. Species and genotypes belonging to Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato complex causing human cystic echinococcosis in Europe (2000–2021): a systematic review. Parasites Vectors. 2022;15:109. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini L., Vieceli L., D'Urso A., Magistrali C.F., Forte C., Mignacca S.A., Trabalza-Marinucci M., Chiorri M. Farm efficiency related to animal welfare performance and management of sheep farms in marginal areas of Central Italy: a two-stage DEA model. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021;20:955–969. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2021.1913076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Citterio C.V., Obber F., Trevisiol K., Dellamaria D., Celva R., Bregoli M., Ormelli S., Sgubin S., Bonato P., Da Rold G., Danesi P., Ravagnan S., Vendrami S., Righetti D., Agreiter A., Asson D., Cadamuro A., Ianniello M., Capelli G. Echinococcus multilocularis and other cestodes in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) of northeast Italy, 2012–2018. Parasites Vectors. 2021;14:29. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conraths F.J., Deplazes P. Echinococcus multilocularis: epidemiology, surveillance and state-of-the-art diagnostics from a veterinary public health perspective. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;213:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes P., Eichenberger R.M., Grimm F. Wildlife-transmitted Taenia and Versteria cysticercosis and coenurosis in humans and other primates. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019;9:342–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes P., Rinaldi L., Alvarez Rojas C.A., Torgerson P.R., Harandi M.F., Romig T., Antolova D., Schurer J.M., Lahmar S., Cringoli G., Magambo J., Thompson R.C.A., Jenkins E.J. 2017. Global Distribution of Alveolar and Cystic Echinococcosis; pp. 315–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore J.D., Howkins A.B. Coenurus serialis in a grey kangaroo. Aust. J. Sci. 1968;30:465. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert J., Gemmell M.A., Meslin F.-X., Pawlowski Z.S. 2001. WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: a Public Health Problem of Global Concern. [Google Scholar]

- Filip K.J., Pyziel A.M., Jeżewski W., Myczka A.W., Demiaszkiewicz A.W., Laskowski Z. First molecular identification of Taenia hydatigena in wild ungulates in Poland. EcoHealth. 2019;16:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s10393-019-01392-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garippa G., Varcasia A., Scala A. Cystic echinococcosis in Italy from the 1950s to present. Parassitologia. 2004;46:387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatee M.A., Nikaein K., Taylor W.R., Karamian M., Alidadi H., Kanannejad Z., Sehatpour F., Zarei F., Pouladfar G. Environmental, climatic and host population risk factors of human cystic echinococcosis in southwest of Iran. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20:1611. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09638-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson P.S., Ballard W.B., Nowak R.M., Mech L.D. Accuracy and precision of estimating age of gray wolves by tooth wear. J. Wildl. Manag. 2000;64:752. doi: 10.2307/3802745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gori F., Armua-Fernandez M.T., Milanesi P., Serafini M., Magi M., Deplazes P., Macchioni F. The occurrence of taeniids of wolves in Liguria (northern Italy) Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015;4:252–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guberti V., Fenati M., Bolognini M., Lanfranchi P., Battelli G. ISTISAN Congressi-Istituto Superiore Di Sanità. Rome. 2005. Utilizzo di un modello matematico per lo studio dell’epidemiologia dell’echinococcosi nel lupo; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Guberti V., Bolognini M., Lanfranchi P., Battelli G. Echinococcus granulosus in the wolf in Italy. Parassitologia. 2004;46:425–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guberti V., Stancampiano L., Francisci F. Intestinal helminth parasite community in wolves (Canis lupus) in Italy. Parassitologia. 1993;35:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough I. Subcutaneous larval Taenia serialis in a ring-tailed possum (Pseudocheirus peregrinus) Aust. Vet. J. 2000;78:468. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb11860.x. 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K.E., Patel N.G., Levy M.A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J.L., Daszak P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkar L., Laurimäe T., Acosta-Jamett G., Andresiuk V., Balkaya I., Casulli A., Gasser R.B., González L.M., Haag K.L., Zait H., Irshadullah M., Jabbar A., Jenkins D.J., Manfredi M.T., Mirhendi H., M’rad S., Rostami-Nejad M., Oudni-M’rad M., Pierangeli N.B., Ponce-Gordo F., Rehbein S., Sharbatkhori M., Kia E.B., Simsek S., Soriano S.V., Sprong H., Šnábel V., Umhang G., Varcasia A., Saarma U. Distinguishing Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto genotypes G1 and G3 with confidence: a practical guide. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018;64:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh M. Foraging adaptation and the relationship between food-web complexity and stability. Science. 2003;299:1388–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1079154. 80- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty K.D. The evolution of trophic transmission. Parasitol. Today. 1999;15:111–115. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(99)01397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos-Frank B. One or two intermediate hosts in the life cycle ofMesocestoides (Cyclophyllidea, Mesocestoididae)? Parasitol. Res. 1991;77:726–728. doi: 10.1007/BF00928692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchioni F., Coppola F., Furzi F., Gabrielli S., Baldanti S., Boni C.B., Felicioli A. Taeniid cestodes in a wolf pack living in a highly anthropic hilly agro-ecosystem. Parasite. 2021;28:10. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2021008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marucco F., McIntire E.J.B. Predicting spatio-temporal recolonization of large carnivore populations and livestock depredation risk: wolves in the Italian Alps. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010;47:789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Massolo A., Valli D., Wassermann M., Cavallero S., D'Amelio S., Meriggi A., Torretta E., Serafini M., Casulli A., Zambon L., Boni C.B., Ori M., Romig T., Macchioni F. Unexpected Echinococcus multilocularis infections in shepherd dogs and wolves in south-western Italian Alps: a new endemic area? Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2018;7:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister C.T., Trauth S.E., Plummer M.V. A new host record for Mesocestoides sp. (Cestoidea: cyclophyllidea: mesocestoididae) from a rough green snake Opheodrys aestivu (Ophidia: colubridae) in Arkansas. U.S.A. Comp. Parasitol. 2013;80:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- McManus D.P. Molecular discrimination of taeniid cestodes. Parasitol. Int. 2006;55:S31. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.004. –S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moks E., Jõgisalu I., Saarma U., Talvik H., Järvis T., Valdmann H. Helminthologic survey of the wolf (Canis lupus) in Estonia, with an emphasis on Echinococcus granulosus. J. Wildl. Dis. 2006;42:359–365. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-42.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandi B., Galosi L., Morandi F., Cruciani D., Crotti S., Spina S., Rossi G., Pascucci I., Gambini S., Gavaudan S. XXXII Congresso Nazionale SoIPA. Naples. 2022. Are two coincidences a proof? The European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) is a suitable intermediate host for Taenia serialis; p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Morandi B., Bazzucchi A., Gambini S., Crotti S., Cruciani D., Morandi F., Napoleoni M., Piseddu T., Di Donato A., Gavaudan S. A novel intermediate host for Taenia serialis (Gervais, 1847): the European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus L. 1758) from the Monti Sibillini National Park (MSNP), Italy. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2022;17:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2021.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M., Li T., Han X., Ma X., Xiao N., Qiu J., Wang H., Yanagida T., Mamuti W., Wen H., Moro P.L., Giraudoux P., Craig P.S., Ito A. Genetic polymorphisms of Echinococcus tapeworms in China as determined by mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010;40:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M.T.T., Gabriël S., Abatih E.N., Dorny P. A systematic review on the global occurrence of Taenia hydatigena in pigs and cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;226:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira A.L., Mateus T.L., Llaneza L., Vieira-Pinto M.M., Madeira de Carvalho L.M. Gastrointestinal parasites in iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) from the iberian peninsula. Parasitologia. 2023;3:15–32. doi: 10.3390/parasitologia3010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poglayen G., Stancampiano L., Varcasia A., Pipia A.P., Bio C., Romanelli C. Xth European Multicolloquium Parasitol. Paris. 2008. Updating on cystic echinococcosis in northern Italy; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Poglayen G., Gori F., Morandi B., Galuppi R., Fabbri E., Caniglia R., Milanesi P., Galaverni M., Randi E., Marchesi B., Deplazes P. Italian wolves (Canis lupus italicus Altobello, 1921) and molecular detection of taeniids in the foreste casentinesi national Park, northern Italian Apennines. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2017;6:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romig T., Deplazes P., Jenkins D., Giraudoux P., Massolo A., Craig P.S., Wassermann M., Takahashi K., de la Rue M. 2017. Ecology and Life Cycle Patterns of Echinococcus Species; pp. 213–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadjjadi S.M. Present situation of echinococcosis in the Middle East and Arabic north africa. Parasitol. Int. 2006;55:S197. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.030. –S202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapp S.G.H., Bradbury R.S. The forgotten exotic tapeworms: a review of uncommon zoonotic Cyclophyllidea. Parasitology. 2020;147:533–558. doi: 10.1017/S003118202000013X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Crease I., Griffin R.H., Gomery M.A., Dorny P., Noh J.C., Handali S., Chastain H.M., Wilkins P.P., Nunn C.L., Snyder-Mackler N., Beehner J.C., Bergman T.J. Identifying wildlife reservoirs of neglected taeniid tapeworms: non-invasive diagnosis of endemic Taenia serialis infection in a wild primate population. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia J.M., Torres J., Miquel J., Llaneza L., Feliu C. Helminths in the wolf, Canis lupus, from north-western Spain. J. Helminthol. 2001;75:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel D., Deplazes P., Mathis A. Identification of taeniid eggs in the faeces from carnivores based on multiplex PCR using targets in mitochondrial DNA. Parasitology. 2007;134:911–920. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulziijargal G., Yeruult C., Khulan J., Gantsetseg C., Wandra T., Yamasaki H., Narankhajid M. Molecular identification of Taenia hydatigena and Mesocestoides species based on copro-DNA analysis of wild carnivores in Mongolia. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2020;11:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varcasia A., Sanna D., Casu M., Lahmar S., Dessì G., Pipia A.P., Tamponi C., Gaglio G., Hrčková G., Otranto D., Scala A. Species delimitation based on mtDNA genes suggests the occurrence of new species of Mesocestoides in the Mediterranean region. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11:619. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3185-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaleśny G., Hildebrand J. Molecular identification of Mesocestoides spp. from intermediate hosts (rodents) in central Europe (Poland) Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:1055–1061. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukowski N., Kirk D., Wadhawan K., Shea D., Start D., Krkošek M. Predators can influence the host‐parasite dynamics of their prey via nonconsumptive effects. Ecol. Evol. 2020;10:6714–6722. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.