Abstract

Background:

Reliable in vitro cellular models are needed to study the phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in health and disease. The aim of this study was to optimize gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)/alginate hydrogels for bioprinting three-dimensional (3D) SMC constructs.

Methods:

Four different hydrogel groups were prepared by mixing different concentrations (% w/v) of GelMA and alginate: G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), and G4 (7.5/3). GelMA 10% was used as control (G5). A circular structure containing human bladder SMCs was fabricated by using an extrusion-based bioprinter. The effects of the mixing ratios on printability, viability, proliferation, and differentiation of the cells were investigated.

Results:

Rheological analysis showed that the addition of alginate significantly stabilized the change in mechanical properties with temperature variations. The group with the highest GelMA and alginate concentrations (G4) exhibited the highest viscosity, resulting in better stability of the 3D construct after crosslinking. Compared to other hydrogel compositions, cells in G4 maintained high viability (> 80%), exhibited spindle-shaped morphology, and showed a significantly higher proliferation rate within an 8-day period. More importantly, G4 provided an optimal environment for the induction of a SMC contractile phenotype, as evidenced by significant changes in the expression of marker proteins and morphological parameters.

Conclusion:

Adjusting the composition of GelMA/alginate hydrogels is an effective means of controlling the SMC phenotype. These hydrogels support bioprinting of 3D models to study phenotypic smooth muscle adaptation, with the prospect of using the constructs in the study of therapies for the treatment of urethral strictures.

Keywords: Bioprinting, Hydrogel, Smooth muscle myocytes, Biomechanical phenomena, Urethral stricture

Introduction

Urethral strictures in male patients are a common complication after infection or traumatic injury to the urethra [1]. The narrowing of the urethra can significantly restrict the normal passage of urine, cause pain during urination, lead to infertility, and thus significantly affect the quality of life of patients. Urethral strictures are typically the result of damage to the urothelium, which triggers inflammation and ultimately leads to spongiofibrosis [2]. Following injury to the tissue, abnormal repair occurs with scarring extending into the corpus spongiosum, where the most notable histologic changes are seen. Dense fibrotic tissue and a decrease in the smooth muscle layer result in a loss of elasticity and compliance of the urethra. The chronic inflammatory process transforms the smooth muscle cells (SMCs) surrounding the mucosa from a contractile to a synthetic phenotype, resulting in increased synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins, mainly type I collagen [3]. These changes in the SMC phenotype and their interactions with the local microenvironment are thought to contribute significantly to the development of urethral strictures. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate SMC differentiation will be helpful in studying the etiology and treatment of urethral strictures. With respect to the latter, tissue engineering approaches have emerged in recent years as promising alternatives for the treatment of urethral strictures, but many challenges remain, primarily due to our lack of understanding of the design requirements that are critical to meeting the structural and functional properties of the urethra [4].

The cellular processes and molecular mechanisms involved in the phenotypic modulation of SMCs are still unclear [5]. Most of the current knowledge on phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has been obtained with two-dimensional (2D) cultures. 2D culture studies do not translate well to physiological conditions, because cells in tissues reside in a three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment. Indeed, recent studies have shown that a proper 3D environment favors the maturation of SMCs into a contractile phenotype [6]. The structure and stiffness of the extracellular environment appear to act synergistically to promote smooth muscle contractility and the mature phenotype [7]. Thus, well-defined 3D platforms are needed to mimic the structural, mechanical, and biochemical cues present in the native tissue and to investigate how the phenotype of SMCs is influenced by the microenvironment.

In the field of tissue engineering, 3D printing technology has recently become popular for the development of biomimetic tissue constructs that can replicate complex tissue structures. 3D bioprinting can facilitate the construction of tissues through the direct deposition of biomaterials, molecules, and cells [8]. The unique porous design of 3D printed structures not only promotes intercellular communication and cell–matrix interaction, but also contributes to the release of nutrients, oxygen, and waste, all of which are critical factors for cell maturation and differentiation [9], 10. Hydrogels are a class of biomaterials that are well suited for creating an ideal 3D environment through bioprinting technologies. Due to their high-water content, they provide a suitable environment to maintain cell viability and promote cell growth [11]. Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) is a gelatin-based hydrogel that possesses a number of important properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, low immunogenicity, and tunable mechanical properties, which make it a preferred choice in biofabrication [12]. Studies have shown that lower concentration of GelMA (< 5w/v%) are better suited to maintain high cell viability [13] However, the low concentration GelMA itself may not have sufficient viscosity for bioprinting processes. In contrast, high concentration GelMA (> 15w/v%) displays excellent printing ability, at expense of significantly reducing cell viability [14]. Therefore, how to further optimize GelMA hydrogel to achieve a balance between print resolution and cell viability is a challenge in the field of 3D bioprinting. Alginate is another hydrogel commonly used for 3D bioprinting due to its rapid gelation in calcium chloride (CaCl2) and adjustable rheological properties [15]. Although the addition of alginate can improve the printability and geometric accuracy of GelMA, excessive concentration of alginate can significantly affect cell viability [16]. Therefore, a possible strategy is to use a low concentration of GelMA to maintain high cell viability while adding an appropriate concentration of alginate to improve the printability and mechanical integrity of the hybrid hydrogel. A recent study using a hybrid GelMA/alginate hydrogel for bioprinting of skeletal muscle myoblasts showed that the mixing ratio and crosslinking parameters are critical for controlling the optimal cell phenotype [17].

In this study, the performance of GelMA/alginate hybrid hydrogels prepared at different concentrations (%w/v) was investigated in terms of printability, structural integrity, and support of smooth muscle growth and maturation. The aim was to find an optimal mixing ratio for the preparation of consistent 3D platforms to study phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle in vitro. The long-term goal is to develop biomimetic tissue engineered constructs that could contribute to the development of new therapies for urethral strictures.

Materials and methods

Preparation of the panel of GelMA/alginate hydrogels

Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA lyophilizate) and photoinitiator (lithiumphenyl-2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoylphosphinate, LAP) were purchased from Cellink (Cellink AB, Gothenburg, Sweden). Alginate (alginic acid sodium salt) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Four hydrogel groups were prepared by adjusting the concentration of the components (GelMA/alginate) as follows: G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3). The fifth group consisted of GelMA 10%, which was used as a reference. The alginate was first dissolved in PBS solution at room temperature. To prepare the GelMA gels, LAP was added to 60 °C warm PBS at a concentration of 0.25% w/v. The GelMA lyophilizate was added to achieve the desired concentration. Finally, the GelMA solution and the alginate solution were mixed in a 1:1 ratio to prepare the hybrid hydrogels. All hydrogels were stored at 37 °C until further use.

Rheological assessment of the hydrogels

Gelation kinetics were studied by measuring the evolution of storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) using an AR-G2 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). A crosshatched parallel plate (diameter 40 mm) and a gap size of 50 µm was used. The measurements were obtained at a constant strain of 5% in a frequency range of 0.1–100 rad s−1 at 28 °C. The temperature dependence of G′ and G″ was determined by temperature sweep by lowering the temperature from 37 to 2 °C with a cooling rate of 5 °C min−1. The time dependence of the G′ and G″ was determined at 10 and 28 °C by performing a constant frequency and strain amplitude of 10 rad s−1 and 5%, respectively.

Assessment of the mechanical properties of the hydrogels following crosslinking

In order to obtain test samples with flat surfaces and repeatable structures, a custom-made sample mold was created. First, 12 mm glass coverslips were coated with a siliconizing reagent (Sigmacote, Sigma-Aldrich). In a 35 mm glass-bottomed dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA, USA), 60 µl of hydrogel sample was pipetted in to the 20 mm microwell. Then, coated coverslips were applied to a single drop to create a thin flat structure. Samples were then irradiated with 405 nm UV light for 15 s. After removing the coverslip, the samples were then incubated in a 0.1 M CaCl2 solution for 2 min. Samples were washed 2–3 times with PBS and kept in PBS at 37 °C for 24 h to reach swelling equilibrium. Six identical specimens were prepared for each group. The local mechanical properties of the crosslinked hydrogel samples were investigated using a Chairo Nanoindenter (Optics life 11, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Briefly, a cantilever with a spring constant of 0.44 N/m and a tip radius of 9 µm was used to indent the sample, while interferometry tracked the bending of the cantilever. The piezo motion minus the deflection of the cantilever was used to calculate the specimen indentation. Each specimen was indent 25 times in a 5 × 5 matrix scan of the specimen, with each indentation point spaced 30 μm apart to measure the elastic modulus. The effective elastic modulus was calculated and the distribution maps of elastic moduli across the surface were generated using a Hertzian model. Measurements were performed in PBS at room temperature.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

To prepare samples for SEM imaging, square (10 × 10) mm2, 2 mm thick structures were printed with an extrusion bioprinter (BIOX, Cellink, Gothenburg, Sweden). The temperature of the print bed was set to 10 °C. After printing, the samples were irradiated with UV light at 405 nm for 15 s and then cross-linked with 100 mM CaCl2 for 120 s. For freeze-drying, the samples were placed in centrifuge tubes with 2 ml Milli-Q water, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then lyophilized for 72 h in an Alpha 1-4LD freeze dryer (Martin Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany). The lyophilized samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold using an Edwards S150B sputter coater prior imaging with a Zeiss XB1540 field-emission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The acceleration voltage of 10 kV was used for all the samples.

Cell culture

Human bladder smooth muscle cells (hSMCs) were purchased from Provitro (Berlin, Germany). Cells were cultured in Ham’s F12 nutrient mixture (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 5 µg/ml insulin, 0.5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 2 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-b), which is referred to as growth medium (GM). The hSMCs were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The hSMCs were passaged once they reached 80% confluence and used for all the experiments reported in this work between passage 3 and 5. The cell cultures were tested by a PCR test (Eurofins Genomics Europe, Ebersberg, Germany) to ensure absence of mycoplasma.

3D bioprinting

For printing cell-laden constructs, hSMCs were enzymatically dispersed from confluent cultures and resuspended in 0.1 ml of GM. The amount of culture medium was calculated based on a 1:10 mixing ratio with the hydrogel to obtain the final concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. The cell suspensions were loaded into a 2 ml syringe while the hydrogels were loaded in a 10 ml syringe. A coupling piece was used to connect the two syringes. The cell suspension and the hydrogels were mixed gently to allow homogeneous distribution of the cells before bioprinting. Cell laden constructs were printed with 27 G needles using the BIOX bioprinter. The printing tool was heated to 28 °C and a ring-like structures were printed into separate wells of a 6-well plate. The printbed temperature was set to 10 °C. Once the constructs were printed, the samples were irradiated with 405 nm UV light for 15 s and then a single well was crosslinked with 100 mM CaCl2 for 2 min. The crosslinked hydrogels were then washed with culture medium to remove excess calcium ions. Culture medium was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Assessment of printability and dimensional stability

To investigate the printability and dimensional stability of the different hydrogel mixtures, the shape of each construct was monitored by optical microscopy immediately after 3D printing and 14 days after printing. Images were captured using AxioVision Rel. 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss) after being observed under a microscope (Zeiss Lumar V12 Stereoscope). Finally, ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to threshold images and measure cross-sectional area. An ink developed for demonstration purposes, with optimal printability and dimensional stability, Cellink XPLORE was used as a control. Using six samples for each group, normalized cross-sectional area values in experimental groups were computed by dividing experimental group area by control area.

Cell viability

To quantify cell viability, a live/dead cell staining was performed immediately after printing and 1 and 7 days after bioprinting. The bioprinted constructs were first washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h in serum-free Ham’s F12 containing calcein-AM (1 μM) and propidium iodide (5 μM). The constructs were washed twice with serum-free Ham’s F12. Samples were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer Z1, Carl Zeiss) to assess morphological changes and cell viability. Images were captured using a digital camera (C11440 ORCA Hamamatsu) and ZEN 2012 software (Carl Zeiss) and then analyzed using the ImageJ software.

Quantification of cell metabolic activity

An Alamar Blue proliferation assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after bioprinting, following the manufacturer’s instructions. At each time point, Alamar Blue reagent was added to the well containing the cell constructs in an amount equal to 10% of the total volume and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Wells containing cell-free constructs were used as negative controls. A volume of 100 µl was then transferred in duplicate to a 96-well microplate. A multi-mode plate reader (EnSpire, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure fluorescence at excitation and emission wavelengths of 560 nm and 610 nm, respectively. After the fluorescence measurement, the constructs were washed once with PBS and fresh GM was added. Cell proliferation was expressed as doubling time, based on actual measurement of fluorescence intensity, as previously reported [18].

qRT-PCR

A quantitative real-time PCR was performed to investigate the transcriptional activity of genes involved in the differentiation of hSMCs. The cell-laden constructs were removed from the culture plates and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes containing liquid nitrogen, where they were ground to a powder. The Aurum total RNA mini kit (Bio-Rad, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to extract total RNA. A nanoliter spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to determine RNA purity and concentration. The iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) was used for the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA). Amplification reactions for each cDNA sample were performed in duplicate, in a final volume of 20 µl. Each reaction consisted of cDNA, IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), and the target-specific primer. The reaction was carried out on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad). The reaction was carried out for 40 amplification cycles: DNA denaturation was performed at 95 °C for 3 min, 95 °C for 10 s, and annealing and extension were performed at the corresponding annealing temperature for 30 s (Table 1). Two housekeeping genes were used to obtain the relative expression level of each gene in different samples: Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A (PPIA), and Tyrosine 3-Monooxygenase/Tryptophan 5-Monooxygenase Activation Protein Zeta (YWHAZ).

Table 1.

Genes, primer sequences, and annealing temperatures used in real time qRT-PCR analysis

| Gene symbol | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTA2 | 5′-AGC AGC CCA GCC AAG CAC TG-3′ | 5′-AGC CGG CCT TAC AGA GCC CA-3′ | 60 °C |

| SMTN | 5′-CGC-GTG-TCT-AAT-CCG-TCG-GT-3′ | 5′-CGT-CGG-TTC-CTT-TCT-GGT-GA-3′ | 60 °C |

| CNN1 | 5′-GTT-CGG-AGA-GGA-GAG-GCA-AA-3′ | 5′-AGG-CCG-TCC-ATG-AAG-TTG-TT-3′ | 60 °C |

| CALD1 | 5′-TCT-GAG-CCT-TCT-GGT-3′ | 5′-CCT-CGG-GAA-GAA-GTT-3′ | 60 °C |

| MYH11 | 5′-TGC-TTC-AAG-ATC-GGG-AGG-AC-3′ | 5′-GGC-CTT-GCG-TGA-TAC-TTG-TG-3′ | 60 °C |

| COL1A1 | 5′-CCT-GGA-TGC-CAA-AGT-CT-3′ | 5′-AAT-CCA-TCG-GTC-ATG-CTC-TC-3′ | 62 °C |

| ELN | 5'-AAG-CAG-CAG-CAA-AGT-TCG-GT-3′ | 5′-ACT-AAG-CCT-GCA-GCA-GCT-CCA-TA-3′ | 62 °C |

| PPIA | 5′-TCC-TGG-CAT-CTT-GTC- CAT-G-3′ | 5′-CCA-TCC-AAC-CAC-TCA-GTC-TTG-3′ | 60 °C |

| YWHAZ | 5′-ACT-TTT-GGT-ACA-TTG-TGG-CTT-CAA-3′ | 5′-CCG-CCA-GGA-CAA-ACC-AGT-AT-3′ | 60 °C |

Immunofluorescent staining

The SMC constructs were grown in GM for 7 days before transferring to differentiation medium (DM) consisting of Ham’s F12 media supplemented with 1% FBS, 30 µg/ml heparin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. After being maintained in DM for 7 days, the constructs were fixed in 100% methanol at room temperature for 5 min and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS (PBS-BSA) for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies consisted of anti-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (MHC) produced in rabbit (ab53219) and anti-smooth muscle alpha actin (α-SMA) produced in mouse (ab7817), both from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Primary antibodies were diluted 1: 200 in PBS-BSA and the constructs incubated overnight (16 h) in a humidified chamber at 4 °C. To fluorescently label the primary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit IgG (both from Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were diluted 1: 200 in PBS-BSA. The 3D constructs were incubated with the secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33,342 (Sigma-Aldrich). An Axio-Observer Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a digital camera (C11440 ORCA, Hamamatsu) and ZEN 2012 software (Carl Zeiss) was used to capture and process all images.

Quantitative image analysis

Fluorescence images of cells at day 14 were analyzed to quantify the expression levels of α-SMA and MHC, and the aspect ratio of the nuclei. First, images of the nuclei were thresholded using the HSB method (hue, saturation, and brightness), and cell nuclei were manually counted using the “Cell Count” plug-in in ImageJ. For the α-SMA and MHC images, the sum of the values of the pixels in the image (integrated density) were measured and corrected for background fluorescence. The reported values were obtained by normalizing the background-corrected density to the number of nuclei in each image. A total of six images per group were analyzed. The “Analyze Particles” plugin was used to evaluate the morphology of the cell nuclei. The aspect ratio was determined by dividing the width by the length of the nuclei. At least 200 nuclei were measured in each group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad 9 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Normal distribution of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For the normally distributed data, univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, with Tukey’s post hoc test. For the nuclei aspect ratio, where the data were not normally distributed, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and a p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Rheological properties of the hydrogels

The study of gelation dynamics is essential to understand the basic behavior of the hydrogel mixtures. Here, the influence of concentration, temperature, and time on the gelation process was systematically studied. The rheological measurement was first performed in the frequency range of 0–100 rad s−1 at the printing temperature (28 °C). It was found that the viscosity of the GelMA/alginate hydrogels systematically increased with the concentration of GelMA and alginate (Fig. 1A). The temperature sweep performed by cooling the solution from 37 °C to 2 °C at a cooling rate of 5 °C min−1 (Fig. 1B) revealed that when the temperature gradually decreased to the gel temperature (20–30 °C), the material went from a viscous dominated state to a solid-like state. The viscous modulus G″ shifted from values around a decade higher than the elastic modulus G′ to a value two decades below G′ at low temperature. The increase in G′ when passing through the gel point is in the order of 5 decades increase. Close to room temperature, the pure GelMA solution (G5) reached the gel point first. According to the results, increasing the concentration of GelMA with decreasing temperature promoted gelation. Consistent with literature it was observed that GelMA solution easily exhibits rapid sol–gel transition at room temperature [19]. A gel is formed over time and to study the time dependency of the gel structure time sweeps were performed at 28 °C and 10 °C (the temperature of the printing process and cooling) respectively (Fig. 1C, D). It is observed for all gels that the two moduli increase the first minute of the test and then flatten. This indicates that there is a structured development of the gel and most significant at the beginning of the time test. The measurements of the pure GelMA at 28 °C did not provide reasonable results as the measurements were unstable. Higher concentrations of GelMA at both 28 °C and 10 °C led to higher G′ and G″ values, and lower temperatures also lead to high G′ and G″ values for all GelMA solutions as they should be. It is important to point out that to resist the negative impact of the high-speed and high-pressure printing process on the cell viability, low viscosity (low G′–G″) is preferred to minimize fluid shear stresses on the cells. Thus, a higher printing temperature is preferred.

Fig. 1.

Rheological characterization of the hybrid hydrogels. The composition of hybrid hydrogels was based on the concentrations (% w/v) of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3) and G5 (10/0). A Frequency sweep 28 °C, B Temperature sweep, C Time sweep 28 °C, D Time sweep 10 °C

Morphology of the crosslinked hydrogels

In addition to mechanical properties, morphological parameters of polymer scaffolds, including porosity and pore size, have been shown to play important roles in cell adhesion, oxygen transport, nutrient exchange, waste removal, and tissue development [20]. The SEM images of the freeze-dried constructs showed that all groups displayed an internal porous structure (Fig. 2A). Comparison of lower magnification (× 100) images of the five groups showed significant differences in pore size and interconnectivity. Compared with G5, groups G1-G4 showed an overall larger pore size and higher degree of interconnectivity. Further examination of the images at higher magnification (× 500) revealed that G1 and G2, both containing 5% GelMA, had relatively large pores, while G5, containing 10% GelMA, had the smallest pores. Interestingly, G3 and G4, whose GelMA content was 7.5%, showed more uniform pore distribution and medium pore sizes.

Fig. 2.

Morphological and mechanical characterization of the crosslinked hydrogels prepared by mixing different concentrations (% w/v) of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3), and G5 (10/0). A Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of freeze-dried hydrogels. For each group, the main panel shows an image acquired at × 500 magnification (scale bar = 20 μm), while the insert shows an overview of the construct at low magnification (× 100 magnification, scale bar = 200 μm). The yellow rectangles indicate the position of the magnified image in the overview. B The Young’s modulus of the different hydrogels after crosslinking (* p < 0.05, n = 6 per group)

Mechanical properties of the crosslinked hydrogels

The cross-linking time and polymer concentration, which play an important role in the growth and differentiation of smooth muscle cells, are the main determinants of the mechanical properties of the hydrogel. When groups with the same alginate concentration were compared, the concentration of GelMA had a positive effect on the mechanical properties of GelMA/alginate hydrogels and significantly increased the elastic modulus (Fig. 2B). The hydrogel with the highest concentration of GelMA (G5) had the highest stiffness. For the combination with 7.5% GelMA, the higher the concentration of alginate, the greater the stiffness (G3 and G4). There was no significant difference in stiffness when alginate (1.5% and 3%) was mixed with 5% GelMA, as both G1 and G2 had a stiffness of approximately 4.5 kPa.

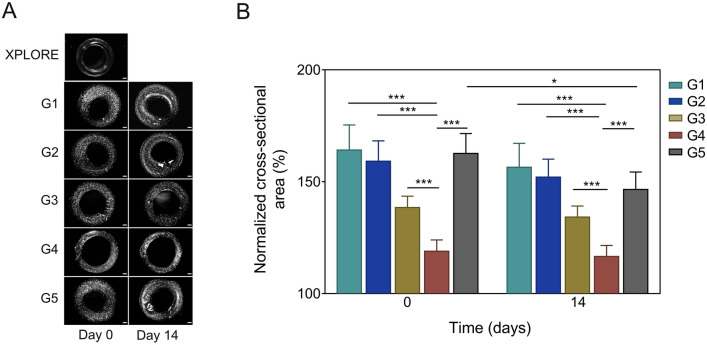

Printability of hydrogels and dimensional stability of the constructs

It was found that all hydrogels showed swelling behavior after printing (Fig. 3). Hydrogel G4 (7.5/3) showed the lowest degree of swelling, reflecting the best printability of all hydrogels tested. Among all hydrogels, pure GelMA (G5) was the only hydrogel that showed a significant reduction in cross-sectional area 14 days after culture, while all GelMA/alginate hydrogels displayed a relatively stable structure.

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of the 3D printed constructs using the hybrid hydrogels prepared by mixing different concentrations (% w/v) of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3), and G5 (10/0). A Light-microscope images at day 0 and 14. Scale bar, 500 μm. B Quantitative analysis of cross-sectional area of the constructs. An image of the construct printed with the XPLORE test ink was used as reference for normalization. (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, n = 6 per group)

Cell viability and proliferation

The results showed that the bioprinting procedure did not affect cell viability, as most cells in the bioprinted constructs were viable during the first two days (Fig. 4A). Moreover, hSMCs cultured in all five hydrogels maintained their viability over a period of 7 days. In comparison, in G3 and G4 seem to maintain a higher cell viability as compared to the other groups (Fig. 4B). Proliferation analysis showed an increasing trend in all five groups throughout the experimental period, indicating positive cell growth (Fig. 4C). To compare the proliferation efficiency in the different hydrogels, the growth rate was expressed as the doubling time (td) of the cells (Table 2). In comparison, cell proliferation was significantly faster in hydrogels G3 and G4.

Fig. 4.

Viability and growth of encapsulated cells in the five experimental groups according to the different compositions (% w/v) of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3), and G5 (10/0). A Live cells were stained green, while dead cells were stained red. Light microscopy images at day 0, day 1 and day 7. B Quantitative analysis of live/dead staining images. (* p < 0.05, n = 6). C Average fluorescence intensity values, reflecting the number of viable cells in the constructs, in the five experimental groups at day 2, 4, 6, and 8 after bioprinting (n = 6). Scale bars, 200 μm

Table 2.

Comparison of doubling time of cells grown in the five hydrogel groups (G1–G5)

| Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | |

| Doubling time [days] | 6.36 ± 0.81 | 6.21 ± 0.96 | 5.81 ± 0.86* | 5.56 ± 0.58* | 7.11 ± 1.18 |

*Denotes statistically significant difference vs. G5 (p < 0.05, n = 6)

Cell maturation

To evaluate the effect of different hydrogel combinations on the induction of a contractile phenotype in hSMC at the transcriptional level, five contractile SMC markers and two ECM-related markers were investigated: Smooth muscle alpha actin (ACTA2), calponin (CNN1), caldesmon (CALD1), smoothelin (SMTN), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (MYH11), collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1), and elastin (ELN). Compared with hSMCs cultured in GM for 7 days, expression of all differentiation makers was increased in all five hydrogels at the end of the 7 day induction period (Fig. 5). The relative expression levels of the markers after 7 days in DM were significantly different when comparing the different hydrogels. Notably, the cells in G4 showed the highest expression of contractile SMC markers. The same trend was also observed in for the ELN gene. Although COL1A1 expression was significantly increased in all groups after the 7 day induction period, no statistical differences in expression levels were observed between them.

Fig. 5.

qRT-PCR results for the contractile and ECM-related genes in different groups based on different combinations (% w/v) of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3), and G5 (10/0). A Smooth muscle alpha actin (ACTA2),B caldesmon (CALD1), C calponin (CNN1), D smoothelin (SMTN), E myosin heavy chain (MYH11), F) collagen type I alpha chain 1 (COL1A1), and G elastin (ELN). After printing, the SMC-loaded constructs were cultured in growth medium for 7 days (Day 7) and then in differentiation medium for 7 days (Day 14) (* p < 0.05, n = 6 per group)

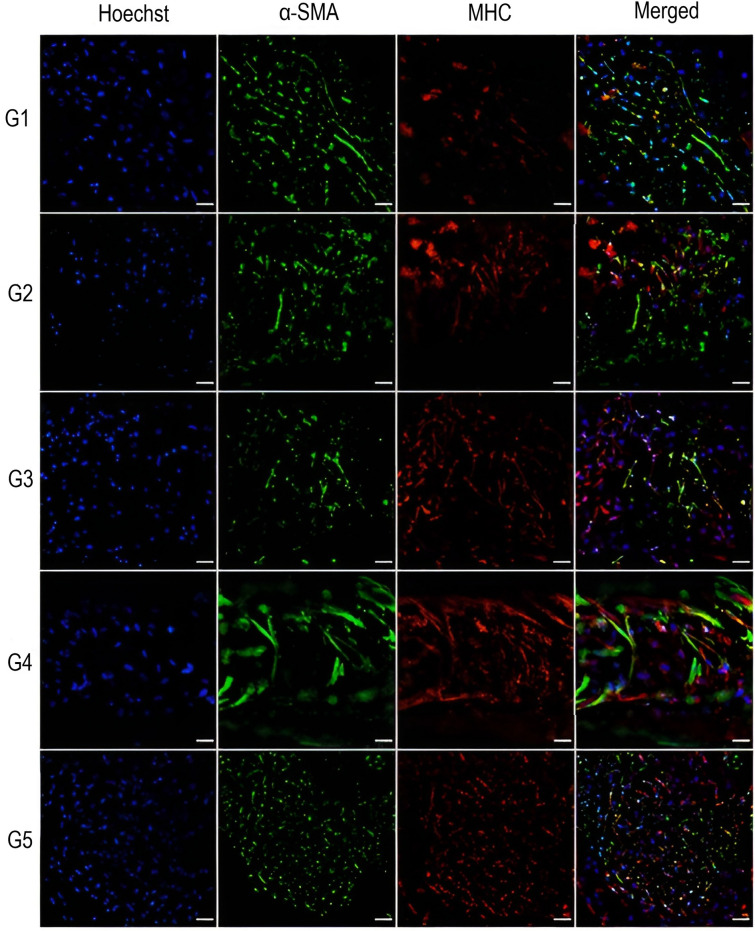

To further assess the differentiation ability of SMC in the five groups of hydrogels, the smooth muscle-specific contractile proteins α-SMA and MHC were investigated by immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Fig. 6, at the end of the differentiation period, the smooth muscle cell-specific markers showed different expression levels depending on the hydrogel type. Consistent with the results of RT-PCR, maturation markers were expressed at different levels in all experimental groups. The immunofluorescence intensity of cells in the G4 constructs appeared to be relatively stronger than that of the other groups for both α-SMA and MHC. Moreover, cells in G4 construct appeared to have a more elongated morphology as compared to the cells in the other hydrogel groups. Further quantitative analysis of the fluorescence images revealed significant differences in the levels of α-SMA and MHC between the different groups (Fig. 7, panels A and B). Notably, cells in G4 showed the highest integrated density for both markers. When evaluating the effects of hydrogel mixing ratio on cell nuclear elongation, it was found that the cells in G4 had a significantly lower aspect ratio compared to the other hydrogel groups (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence staining of hSMCs in the five experimental groups based on different ratios of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3), and G5 (10/0). Cells were stained with Hoechst 33,342 for nuclei (Hoechst, in blue), Alexa Fluor 488 for smooth muscle actin filaments (α- SMA, in green), and Alexa Fluor 555 for smooth myosin heavy chain filaments (MHC, in red). Images were acquired on day 14. Scale bar, 100 μm

Fig. 7.

Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence images of five experimental groups based on different ratios of GelMA and alginate, G1 (5/1.5), G2 (5/3), G3 (7.5/1.5), G4 (7.5/3), and G5 (10/0). A Normalized integrated density of smooth muscle alpha actin (α-SMA). B Normalized integrated density of smooth myosin heavy chain (MHC). C Aspect ratio of nuclei at day 14. (* p < 0.05)

Discussion

The ability to create high-resolution tissue-like structures in which cells can proliferate and differentiate is an essential requirement for the design of hydrogels for biomanufacturing [21]. GelMA hydrogels are particularly attractive as bioinks because they can mimic the biological environment [22]. However, the trade-off between processability and cell compatibility makes this gel less attractive for certain applications [23]. In addition, the effect of temperature on the rheological behavior of GelMA affects the fabrication of stable structures by extrusion bioprinting [24]. In this work, it was shown that by combining GelMA and alginate, it is possible to obtain a hydrogel that compensates for these disadvantages. The use of alginate to increase the strength of pure GelMA while reducing the concentration of GelMA has three advantages. First, the rheology of the GelMA/alginate hydrogel mixtures can be easily changed by adjusting the temperature of the syringe and nozzle in the print head. Figure 1B shows how alginate as a plasticizer can help GelMA reduce the interactions between gelatin chains, thus reducing the heat-sensitive behavior compared to the viscosity of 10% GelMA. This means that GelMA/alginate hydrogels are more stable to temperature fluctuations, allowing more consistent printing. Alginate has been reported to form liquid phase gels that increase the uniformity of extrusion of gelatin/alginate mixtures, which would explain the increase in loss modulus seen with higher alginate concentrations [25]. The hybrid hydrogel mixture of GelMA and alginate behaved like a viscoelastic solution at 30 °C, with both GelMA and alginate increasing the elastic modulus. The low viscosity of the nozzle ensured that the hydrogel printed well and enabled the extrusion of a smooth and continuous ring structure. After various optimization cycles (data not shown), a temperature of 28 °C was determined to be the optimal printing temperature. Furthermore, it was found that the accuracy of the printed structure was directly related to the concentration of GelMA and alginate when the printing capabilities of different groups of hydrogels were compared. The trend observed here is consistent with previous studies showing that the lower the final polymer concentration in the GelMA/alginate blend, the lower the printability [26]. Interestingly, although the GelMA content in G5 increased, the printing accuracy could be further optimized. Other variables that may be involved for further optimization include the curing time and the concentration of the photoinitiator. In this experiment, the addition of alginate improved the printability of G3 and G4 groups under the same printing conditions. The results show that an excellent and stable printing structure can be obtained under the action of a cooling platform and rapid double crosslinking. Even though the hydrogels were grouped in a limited range to discover the best hydrogel combination for smooth muscle growth and differentiation, the mechanical properties study revealed a gap between G4 and G5 (approximately 7.5 kPa to 10 kPa). Whether another combination of hydrogels falling into this gap would give better results remains to be investigated. It should be noted that the particular hydrogel combinations are likely to be cell specific, as other GelMA/alginate mixing ratios than those found here have been shown to be optimal for skeletal muscle differentiation [17].

The size of the printing nozzles, printing pressure, speed, and curing time were optimized to maximize cell viability while ensuring that the hydrogel could be printed continuously. As a result, the bioprinting process did not drastically affect cell viability. Previous studies have shown that high shear pressure in extrusion-based bioprinting can significantly affect cell survival [27]. Exposure to UV light has also been associated with a reduction in cell viability, particularly when cells are exposed to low wavelength UV light (385 nm) for several hours [28]. Here, the constructs were cross-linked for 15 s with near UV light (405 nm). The applied dose is thought to be minimal to affect cell viability, as studies have shown that the viability and DNA integrity of mesenchymal stem cells remain unchanged after photo-curing cell-loaded constructs with near UV light for one minute or longer [29, 30].

The polymer concentration in the hydrogel had a significant effect on SMCs proliferation. In this regard, the G4 hydrogels appeared to provide a more favorable environment for survival and growth of the SMCs. These results are consistent with previous studies that have shown that the mechanical properties of the scaffold significantly affect cellular functions, including attachment, spreading and migration [31]. Studies performed with vascular SMCs have shown that substrates with stiffness in the physiological range of the arterial tunica media (5–8 kPa) support optimal cell spreading [32]. In addition to hydrogel stiffness, other hydrogel properties such as pore size and porosity have also been shown to contribute to cell fate control [33]. Here, we found that the cross-sectional morphology and pore size of GelMA-alginate hybrid hydrogels were mainly affected by the variation of GelMA concentration, and the pore size appeared to show an inverse relation to GelMA concentration, which is consistent with previous studies [34, 35]. As a derivative of collagen, gelatin possesses RGD peptide sequences, which makes it very effective for cell adhesion [36], and GelMA maintains these cell adhesion domains [37]. Previous studies have shown that different concentrations of GelMA can provide different levels of cell attachment [38, 39], which might explain the differences in cell survival and proliferation rates caused by different combinations of hydrogels found in this work.

Moreover, comparison of differentiation markers between the five groups showed that G4 also favored SMC differentiation. Regarding morphological characterization, considering that nuclear shape is a reliable parameter for assessing the phenotype of SMCs [40], the fact that G4 induced elongated nuclear morphology is also evidence of cell differentiation toward a contractile phenotype. These findings add to a growing body of data suggesting that there is an optimal stiffness range that supports maintenance of the smooth muscle contractile phenotype [6, 14, 41]. Previous studies have shown that increasing substrate stiffness promotes a more de-differentiated, synthetic phenotype, while soft surfaces are associated with a more contractile SMC phenotype [42, 43]. Interestingly, the mechanical properties of the scaffold appear to play a dominant role over the cell adhesive cues [7]. Thus, G4 hydrogels appear to have mechanical properties that affect mechanosensitive signaling pathways, which regulate the expression of genes associated with the contractile phenotype of SMCs. In particular, the two key components of the contractile machinery, α-SMA and MHC, were significantly upregulated at the transcriptional and expression levels, consistent with previous studies [41]. Furthermore, the transcriptional activity of the remaining markers that are strongly associated with the contractile phenotype (the two thin filament proteins caldesmon and calponin, the cytoskeletal protein smoothelin, and the ECM protein elastin) were also significantly upregulated in cells within G4. With respect to collagen I, the results indicate that transcriptional activity was significantly increased in all groups after the initial 7 day induction period. This is consistent with a previous study by Kindy and colleagues showing that collagen I expression is increased in SMC cultures when exposed to low FBS and heparin [44]. The biochemical signals may have overridden the mechanical signals, which could explain the lack of response of this ECM protein to the change in hydrogel composition. Overall, the results of this work highlight the fact that matrix stiffness is a key parameter controlling maturation and lineage specification [32].

The limited number of combinations of GelMA, which allowed using GelMA at low concentrations, is one of the limitations of this study. In addition, a relatively low cell density (2 × 106 cells/ml) was used to better observe cell spreading. A higher cell density will help in the development of more realistic smooth muscle cell constructs. Since the goal of this study was to demonstrate the viability of the smooth muscle cells after bioprinting, the tests were performed over a short period of time. Further studies on the long-term growth and functional maturation of the cells would be required.

In conclusion, by combining alginate and GelMA, it was shown that it is possible to bioprint consistent SMC constructs that exhibit high viability. The addition of alginate not only maintained the advantages of low-concentration GelMA in terms of cell compatibility, but also significantly reduced the limitations of pure GelMA in terms of temperature sensitivity of the printing environment. Evaluation of the cell-loaded constructs with different composition ratios showed that G4 (7.5% GelMA/3% alginate) provided the highest structural fidelity while supporting the expression of key cellular and extracellular molecules that are hallmarks of the contractile SMC phenotype. Therefore, this method has the potential to provide promising bioprinting platforms for studying smooth muscle phenotypic adaptation in 3D. It is evident that suitable mechanical properties and pore distribution of the hydrogels, as well as interconnected and adequately sized pores are critical for activating the contractile phenotype and may significantly influence smooth muscle cell maturation, opening a perspective for the application of these constructs in the study of therapies for the treatment of urethral strictures.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grants from the China Scholarship Council, S.C. Van Fonden, Grosserer L.F. Foghts Fond, Simon Fougner Hartmanns Familiefond, and Brødrene Hartmanns Fond. Authors would like to express special thanks to Lisa Engen for her technical assistance.

Author contributions

ZX and CPP conceived the study and participated in its design; ZX performed the experiments, acquired the data, prepared the figures, and did the statistical analysis. ZX and CPP drafted the paper. QP, TL, and LG provided technical support on acquisition and analysis of qPCR, rheological and SEM data, respectively. JCC, VZ, and CPP critically revised the manuscript; all the authors approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

No animal or human data are reported in this study. The research involves the use of an existing anonymized cell line acquired from a commercial source.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Santucci RA, Joyce GF, Wise M. Male urethral stricture disease. J Urol. 2007;177:1667–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandes SB. Epidemiology, etiology, histology, classification, and economic impact of urethral stricture disease. In: Klein EA, editor. Urethral reconstructive surgery. Humana Press; 2008. pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang GC, Huang TR, Hu YY, Wang KY, Shi H, Yin L, et al. Corpus cavernosum smooth muscle cell dysfunction and phenotype transformation are related to erectile dysfunction in prostatitis rats with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Inflamm (Lond) 2020;17:2. doi: 10.1186/s12950-019-0233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbas TO, Yalcin HC, Pennisi CP. From acellular matrices to smart polymers: degradable scaffolds that are transforming the shape of urethral tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1763. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto N, Kiyono T, Saitow F, Asada M, Yoshida M. Reversible differentiation of immortalized human bladder smooth muscle cells accompanied by actin bundle reorganization. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0186584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin H, Qiu X, Du Q, Li Q, Wang O, Akert L, et al. Engineered microenvironment for manufacturing human pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;12:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding Y, Xu X, Sharma S, Floren M, Stenmark K, Bryant SJ, et al. Biomimetic soft fibrous hydrogels for contractile and pharmacologically responsive smooth muscle. Acta Biomater. 2018;74:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JW, Choi YJ, Yong WJ, Pati F, Shim JH, Kang KS, et al. Development of a 3D cell printed construct considering angiogenesis for liver tissue engineering. Biofabrication. 2016;8:015007. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/1/015007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Yang F, Zhao H, Gao Q, Xia B, Fu J. Research on the printability of hydrogels in 3D bioprinting. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–3. doi: 10.1038/srep29977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hölzl K, Lin S, Tytgat L, Van Vlierberghe S, Gu L, Ovsianikov A. Bioink properties before, during and after 3D bioprinting. Biofabrication. 2016;8:032002. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/3/032002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi YJ, Park H, Ha DH, Yun HS, Yi HG, Lee H. 3D bioprinting of in vitro models using hydrogel-based bioinks. Polymers (Basel) 2021;13:366. doi: 10.3390/polym13030366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseini V, Ahadian S, Ostrovidov S, Camci-Unal G, Chen S, Kaji H, et al. Engineered contractile skeletal muscle tissue on a microgrooved methacrylated gelatin substrate. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:2453–2465. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Heinrich MA, Zhou Y, Akpek A, Hu N, Liu X, et al. Extrusion bioprinting of shear-thinning gelatin methacryloyl bioinks. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:1601451. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201601451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandl F, Sommer F, Goepferich A. Rational design of hydrogels for tissue engineering: impact of physical factors on cell behavior. Biomaterials. 2007;28:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarker B, Boccaccini AR. Alginate utilization in tissue engineering and cell therapy. In: Rehm B, Moradali MF, editors. Alginates and their biomedical applications. Singapore: Springer; 2018. pp. 121–155. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu K, Shin SR, van Kempen T, Li YC, Ponraj V, Nasajpour A, et al. Gold nanocomposite bioink for printing 3D cardiac constructs. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27:1605352. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201605352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seyedmahmoud R, Çelebi-Saltik B, Barros N, Nasiri R, Banton E, Shamloo A, et al. Three-dimensional bioprinting of functional skeletal muscle tissue using gelatin methacryloyl-alginate bioinks. Micromachines (Basel) 2019;10:679. doi: 10.3390/mi10100679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennisi CP, Zachar V, Fink T, Gurevich L, Fojan P. Patterned polymeric surfaces to study the influence of nanotopography on the growth and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. In: Turksen K, editor. Stem Cell Nanotechnology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013. pp. 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar H, Sakthivel K, Mohamed MG, Boras E, Shin SR, Kim K. Designing gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)-based bioinks for visible light stereolithographic 3D biofabrication. Macromol Biosci. 2021;21:2000317. doi: 10.1002/mabi.202000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holy CE, Shoichet MS, Davies JE. Engineering three-dimensional bone tissue in vitro using biodegradable scaffolds: Investigating initial cell-seeding density and culture period. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51:376–382. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<376::AID-JBM11>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malda J, Visser J, Melchels FP, Jüngst T, Hennink WE, Dhert WJ, et al. 25th anniversary article: engineering hydrogels for biofabrication. Adv Mater. 2013;25:5011–5028. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji S, Guvendiren M. Recent advances in bioink design for 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2017;5:23. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2017.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin J, Yan M, Wang Y, Fu J, Suo H. 3D bioprinting of low-concentration cell-laden gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) bioinks with a two-step cross-linking strategy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:6849–6857. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b16059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ying G, Jiang N, Yu C, Zhang YS. Three-dimensional bioprinting of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) Biodes Manuf. 2018;1:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s42242-018-0028-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao T, Gillispie GJ, Copus JS, Pr AK, Seol YJ, Atala A, et al. Optimization of gelatin-alginate composite bioink printability using rheological parameters: a systematic approach. Biofabrication. 2018;10:034106. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/aacdc7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldana AA, Valente F, Dilley R, Doyle B. Development of 3D bioprinted GelMA-alginate hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties. Bioprinting. 2021;21:e00105. doi: 10.1016/j.bprint.2020.e00105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sears NA, Seshadri DR, Dhavalikar PS, Cosgriff-Hernandez E. A review of three-dimensional printing in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2016;22:298–310. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2015.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence KP, Douki T, Sarkany RP, Acker S, Herzog B, Young AR. The UV/visible radiation boundary region (385–405 nm) damages skin cells and induces “dark” cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in human skin in vivo. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12722. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30738-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guvendiren M, Burdick JA. Stiffening hydrogels to probe short-and long-term cellular responses to dynamic mechanics. Nat Commun. 2012;3:792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong DY, Ranganath T, Kasko AM. Low-dose, long-wave UV light does not affect gene expression of human mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi J, Xing MM, Zhong W. Development of hydrogels and biomimetic regulators as tissue engineering scaffolds. Membranes (Basel) 2012;2:70–90. doi: 10.3390/membranes2010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walthers CM, Nazemi AK, Patel SL, Wu BM, Dunn JC. The effect of scaffold macroporosity on angiogenesis and cell survival in tissue-engineered smooth muscle. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5129–5137. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CH, Su JJ, Lee SY, Lin YM. Stiffness modification of photopolymerizable gelatin-methacrylate hydrogels influences endothelial differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:2099–2111. doi: 10.1002/term.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee Y, Lee JM, Bae PK, Chung IY, Chung BH, Chung BG. Photo-crosslinkable hydrogel-based 3D microfluidic culture device. Electrophoresis. 2015;36:994–1001. doi: 10.1002/elps.201400465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosellini E, Cristallini C, Barbani N, Vozzi G, Giusti P. Preparation and characterization of alginate/gelatin blend films for cardiac tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;91:447–453. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simitzi C, Ranella A, Stratakis E. Controlling the morphology and outgrowth of nerve and neuroglial cells: the effect of surface topography. Acta Biomater. 2017;51:21–52. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nichol JW, Koshy ST, Bae H, Hwang CM, Yamanlar S, Khademhosseini A. Cell-laden microengineered gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5536–5544. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu P, Guan J, Chen Y, Xiao H, Yang T, Sun H, et al. Stiffness of photocrosslinkable gelatin hydrogel influences nucleus pulposus cell propertiesin vitro. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:880–891. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thakar RG, Cheng Q, Patel S, Chu J, Nasir M, Liepmann D, et al. Cell-shape regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation. Biophys J. 2009;96:3423–3432. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen LF, Bentzon JF, Albarrán-Juárez J. The phenotypic responses of vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to mechanical cues. Cells. 2021;10:2209. doi: 10.3390/cells10092209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sazonova OV, Isenberg BC, Herrmann J, Lee KL, Purwada A, Valentine AD, et al. Extracellular matrix presentation modulates vascular smooth muscle cell mechanotransduction. Matrix Biol. 2015;41:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaes RD, van den Berk L, Boonen B, van Dijk DP, Olde Damink SW, Rensen SS. A novel human cell culture model to study visceral smooth muscle phenotypic modulation in health and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;315:C598–607. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00167.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kindy MS, Chang CJ, Sonenshein GE. Serum deprivation of vascular smooth muscle cells enhances collagen gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11426–11430. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)37974-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]